The authors show the dual regulation of phagosomal degradation and migration of Drosophila macrophages by Trpml, a lysosomal calcium channel. Trpml promotes cell migration by activating actomyosin contractility but supports phagosomal degradation through a myosin-independent mechanism.

Abstract

Phagocytes use their actomyosin cytoskeleton to migrate as well as to probe their environment by phagocytosis or macropinocytosis. Although migration and extracellular material uptake have been shown to be coupled in some immune cells, the mechanisms involved in such coupling are largely unknown. By combining time-lapse imaging with genetics, we here identify the lysosomal Ca2+ channel Trpml as an essential player in the coupling of cell locomotion and phagocytosis in hemocytes, the Drosophila macrophage-like immune cells. Trpml is needed for both hemocyte migration and phagocytic processing at distinct subcellular localizations: Trpml regulates hemocyte migration by controlling actomyosin contractility at the cell rear, whereas its role in phagocytic processing lies near the phagocytic cup in a myosin-independent fashion. We further highlight that Vamp7 also regulates phagocytic processing and locomotion but uses pathways distinct from those of Trpml. Our results suggest that multiple mechanisms may have emerged during evolution to couple phagocytic processing to cell migration and facilitate space exploration by immune cells.

Introduction

Cell migration is essential for the development of multicellular organisms as well as for proper immune function. To move forward, single cells adopt a polarized organization with a leading edge, whereby actin-based protrusions repetitively extend and retract, and a contractile rear that pulls the cell body forward (Le Clainche and Carlier, 2008). Depending on the physical and biochemical properties of the environment and of the cell type, cell migration involves either specific adhesion, for example to the ECM via integrins (Hamidi and Ivaska, 2018), or unspecific friction, most likely via alternative transmembrane proteins (Bergert et al., 2015). In both cases, forward movement is tightly coupled to a retrograde flow of actin and requires the activity of the actin-based motor protein Myosin-II (Myo-II; Tomasello et al., 2004; Conti and Adelstein, 2008). Myo-II facilitates actin retrograde flow and is further advected by this flow to accumulate at the cell rear, where it reinforces polarity and facilitates cell rear retraction (Maiuri et al., 2015). Importantly, Myo-II can also act at the cell front during locomotion, for the retraction of actin protrusions (Conti and Adelstein, 2008; Chabaud et al., 2015). These actin protrusions eventually contribute to cell forward movement, and importantly, they play a key role in environment exploration (Leithner et al., 2016).

In general, cells use protrusions to sense the presence of chemical cues such as morphogens, chemokines, or cytokines in their environment. This occurs in many biological contexts including development and immunity (Christian, 2012; Sokol and Luster, 2015). Environmental chemical cues can further enhance cell exploration capacity by stimulating protrusion formation and/or retraction (Caballero et al., 2014). Immune cells also use actin protrusions to sense danger-associated signals, such as microbial components or signals resulting from changes in tissue integrity. In the case of macrophages or dendritic cells, these protrusions can lead to the formation of phagosomes or macropinosomes, allowing the internalization of extracellular material (Condon et al., 2018). The formation and intracellular trafficking of phagosomes (and macropinosomes) rely on Myo-II–dependent actin contraction (Swanson, 2008; Chabaud et al., 2015), reminiscent of the role that this motor protein plays in actin protrusion retraction. Once in the intracellular space, phagosomes (and macropinosomes) fuse with endolysosomal compartments for maturation and processing of internalized molecules (Fairn and Grinstein, 2012). This processing step is essential for both innate and/or adaptive immune responses in all metazoans.

Interestingly, macropinocytosis and cell migration were found to compete for Myo-II activity in mouse dendritic cells, as both cellular functions rely on Myo-II but at distinct subcellular locations (Chabaud et al., 2015). Furthermore, several reports have highlighted the existence of a link between endolysosomal processing and cell migration. Perturbation of endocytic trafficking reduces migration of mammalian cancer cells by compromising the recycling of the small GTPase Rac1 at the membrane, which is needed for the formation of actin protrusions (Palamidessi et al., 2008). The accumulation of extracellular material as a result of cathepsin deficiency disrupts endosome recycling and impairs macrophage migration in zebrafish (Berg et al., 2016). Similarly, it was shown in Drosophila that the accumulation of undigested apoptotic cells impairs efficient macrophage migration in vivo (Evans et al., 2013). Although these reports strongly suggest that the migratory and endocytic function of immune cells are coupled, whether such coupling relies on a single or multiple pathways remains unclear.

A critical molecule for the interplay between cell migration and trafficking of late endosomes and lysosomes may be the Ca2+ channel TRPML1(Transient Receptor Potential Mucolipin 1, also known as MCOLN1), which has been involved in both processes in distinct cell types. This ubiquitously expressed channel is localized in late endosomes and lysosomes from where it allows the flux of calcium ions into the cytosol. It regulates membrane trafficking during phagocytosis and autophagy as well as lysosome secretion in different cell types and organisms (Wang et al., 2014; Zeevi et al., 2007; LaPlante et al., 2006; Venkatachalam et al., 2013; Medina et al., 2015, 2011; Samie et al., 2013). In mouse dendritic cells, Trpml deficiency leads to decreased migration, chemotaxis, and actomyosin retrograde flow (Bretou et al., 2017). In humans, mutations in TRPML1 result in mucolipidosis type IV (Bassi et al., 2000), a recessive lysosomal storage disorder (Zeevi et al., 2007; Samanta et al., 2018). Cells from patients with mucolipidosis type IV present with enlargement of lysosomes and late endosomes, impaired autophagy, and lipid accumulation (Venkatachalam et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2012; Di Paola et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2014a). Similar phenotypes are observed in Drosophila melanogaster trpml-deficient macrophages, which also exhibit impaired phagosome processing and bacterial phagocytosis (Wong et al., 2017), suggesting a functional conservation of the channel among species.

Here, we used Drosophila hemocytes, which present an important degree of structural and functional conservation with mammalian phagocytes (Browne et al., 2013; Evans and Wood, 2011), to explore the link between phagocytic processing and cell migration. We show that Trpml couples phagocytic processing to hemocyte locomotion and further identify this Ca2+ channel as a central regulator of Myo-II contractility. Accordingly, hemocyte expression of trpml is needed for antibacterial immune responses. Noticeably, we observed that although the lysosomal SNARE protein Vamp7 (Braun et al., 2004) regulates both phagocytosis and hemocyte migration, it has no impact on the actomyosin cytoskeleton. Our results show the existence of distinct pathways that couple phagocytic processing to cell migration, which might facilitate space exploration by immune cells.

Results

Perturbing phagocytic processing by knocking down Trpml or Vamp7 is associated with compromised hemocyte migration

To evaluate the link between phagocytic processing and cell migration, we decreased the phagocytic processing capacity of fly hemocytes and analyzed the impact of such perturbation on their migratory capacity. Two strategies were used: decreased Trpml or Vamp7 expression, both proteins being involved in phagolysosomal fusion (Dayam et al., 2015; Braun et al., 2004; Wong et al., 2017).

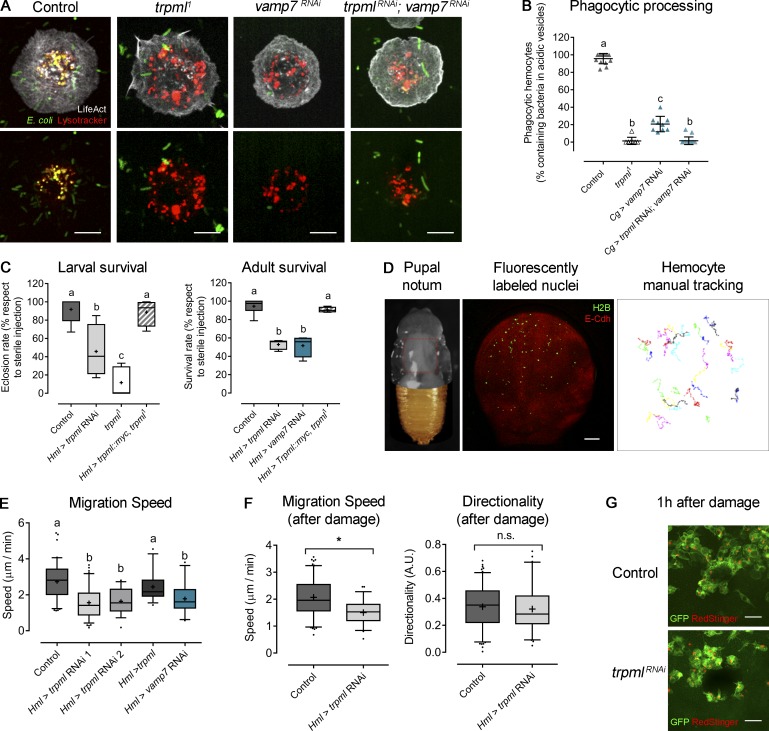

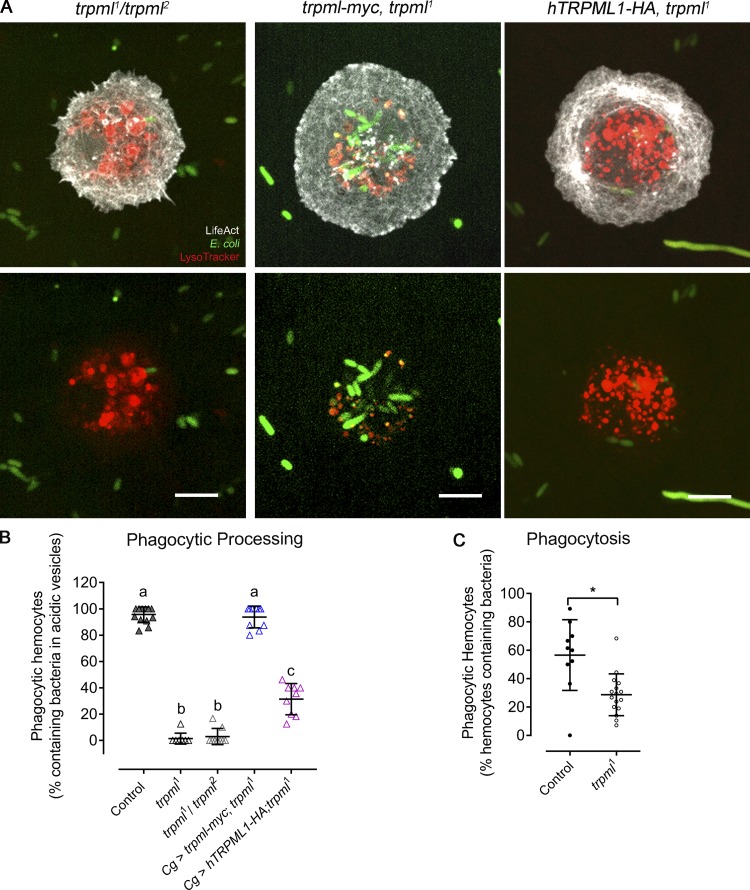

We cultured larval hemocytes expressing LifeAct-GFP with fluorescently labeled bacteria in the presence of LysoTracker Red and assessed the codistribution of acidic vesicles with bacteria (phagolysosomes) after 1 h of culture. We found that hemocytes null for trpml (trpml1) or knockdown for vamp7 (vamp7 RNAi) showed impaired bacteria arrival to acidic compartments (Fig. 1, A and B). Consistently, trpml1/trpml2 trans-heterozygous hemocytes were unable to degrade bacteria. In addition, trpml1 hemocytes exhibited decreased phagocytic rates (Fig. S1), coinciding with a recent report showing that phagocytosis is dependent on efficient degradation of formerly engulfed bacteria (Wong et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Trpml is required for hemocyte migration, phagocytic processing, and immune response. (A) Representative images of hemocytes cultured with fluorescently labeled bacteria and LysoTracker probe. Scale bar: 5 µm. (B) Phagocytic processing quantified as the percentage of hemocytes containing bacteria within at least two acidic vesicles after 1 h of culture (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 20 hemocytes/condition). (C) Larvae/adult females were injected with bacteria and eclosion/survival rate was quantified. Values are normalized against sterile media injection (n = 3 independent experiments, n ≥ 20 animals/experiment). (D) Left: Representative image of a 16 h ± 30 min–APF pupa with removed cuticle to expose the notum. Red square indicates the region of analysis. Middle: Notum with fluorescently labeled epithelium and hemocyte nuclei. Scale bar: 150 µm. Right: Representative tracks of randomly migrating hemocytes. (E) Hemocyte migration speed quantification in physiological conditions (n = 3 independent experiments, n ≥ 2 animals/experiment). (F) Hemocyte migration speed (left) and directionality (right) measured during 1 h after damage (n = 3 independent experiments, n ≥ 2 animals/experiment); t test (*, P < 0.05). A.U., arbitrary units. (G) Representative images of wound area 1 h after ablation showing the recruitment of hemocytes in both control and trpml-deficient conditions. Scale bar: 10 µm. The values in B are shown as scatter dot plot, indicating mean ± SD, and the values in C, E, and F are shown as box and whiskers (5%–95%), whereby mean values are indicated as “+.” In B, C, and E, one-way ANOVA statistical analysis was performed with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P < 0.05). n.s., not significant. Hml and Cg stand for hemolectin and collagen Gal4 drivers, respectively.

Figure S1.

Genetic complementation and rescue of trpml1 phenotypes in phagocytic processing and phagocytosis. (A) Representative images of hemocytes cultured with fluorescently labeled bacteria and LysoTracker probe. Scale bar: 5 µm. (B) Phagocytic processing quantified as the percentage of hemocytes containing bacteria within at least two acidic vesicles after 1 h of culture (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 20 hemocytes/condition). One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test; statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P ≤ 0.05). (C) Percentage of hemocytes capable of internalizing bacteria after 15 min of culture (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 40 hemocytes/condition). t test (*, P < 0.05). Cg, collagen Gal4 driver; myc and HA, c-myc and hemagglutinin epitopes. (B and C) Data are presented as scatter dot plot, indicating mean ± SD.

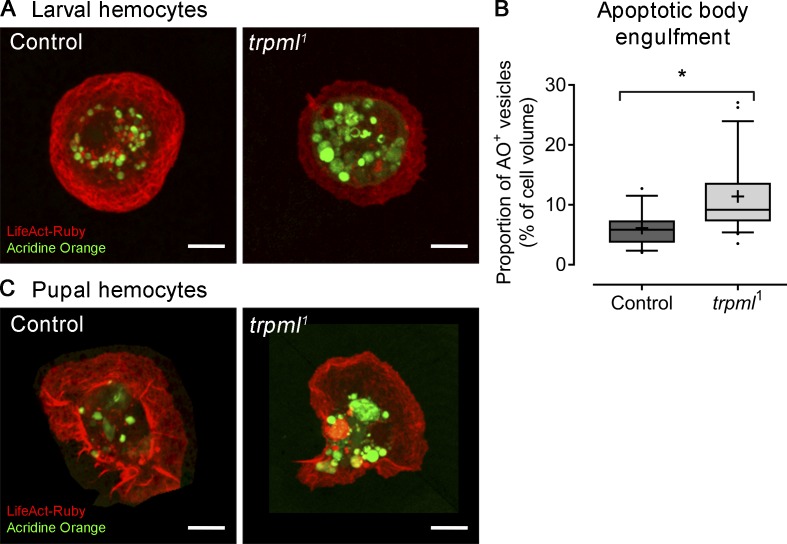

Of note, the lysosomes in trpml1 hemocytes are noticeably larger (Fig. 1 A), suggesting that they might be accumulating unprocessed apoptotic cell corpses, largely engulfed during earlier phases of development (Wood and Jacinto, 2007). We thus evaluated their presence by staining with the vital dye acridine orange, which selectively stains engulfed apoptotic bodies (Evans et al., 2013; Weavers et al., 2016). We evaluated larval hemocytes cultured ex vivo and observed a noticeable accumulation of acridine orange–positive vesicles (Fig. S2 A), occupying 11.4% of hemocyte volume in trpml1 hemocytes, significantly higher than the 6.1% observed in controls (Fig. S2 B). These results indicate that lysosomes in trpml1 hemocytes might accumulate unprocessed apoptotic cell corpses engulfed during earlier phases of development.

Figure S2.

Apoptotic body degradation is Trpml dependent. LifeAct-Ruby–labeled hemocytes were stained with acridine orange to reveal engulfed apoptotic bodies. (A) Larval hemocytes cultured ex vivo reveal the accumulation of large-sized vesicles stained positively with acridine orange. (B) Quantification of volume occupancy of acridine orange–positive vesicles with respect to cell body volume (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 5 cells/condition). Values are presented as box and whiskers (5%–95%); mean values are indicated as “+. t test (*, P < 0.05).” AO+, acridine orange positive vesicles. (C) Pupal hemocytes attached to the basal lamina were imaged after pupae dissection (17-h APF, 29°C) and staining with acridine orange, revealing a similar accumulation of apoptotic bodies in trpml1 mutant hemocytes. Scale bar: 5 µm.

Additionally, we found that lethality due to bacterial inoculation was increased when knocking down trpml or vamp7 in hemocytes (Fig. 1 C). The trpml1 phagocytic processing phenotypes were either fully rescued by expressing a Drosophila trpml-myc construct or partially rescued by expressing human TRPML1 (Fig. S1). Furthermore, the lower survival rates observed in trpml1 mutant flies were rescued when the trpml-myc construct was expressed only in the hemocytes, indicating a cell autonomous requirement of this Ca2+ channel in antibacterial immune responses (Fig. 1 C).

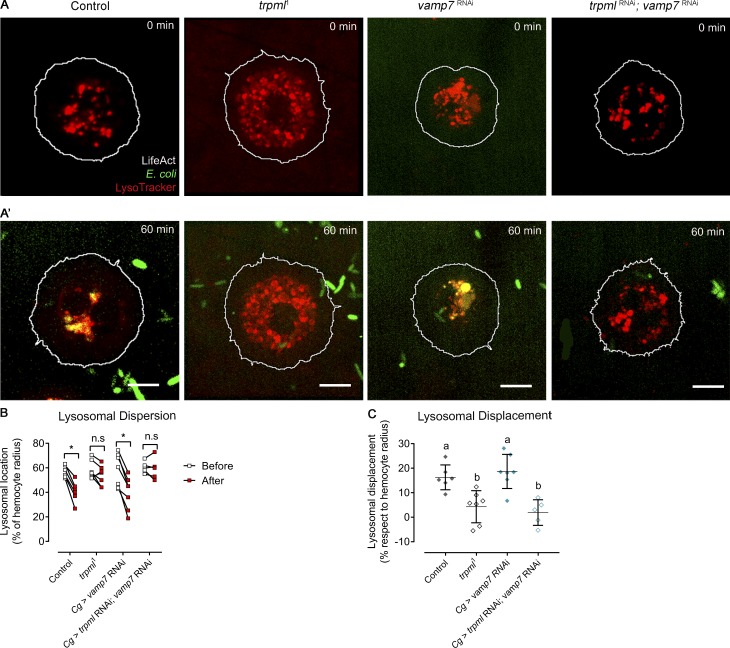

Interestingly, we observed that in wild-type hemocytes, acidic vesicles were initially dispersed throughout the cytoplasm but underwent centripetal movements during phagocytic processing. Centripetal lysosome repositioning was lost in both trpml deficiencies (trpml1 mutant and RNAi-mediated knockdown; Fig. S3). This observation is consistent with previous reports showing that (1) lysosomal centripetal movement is Ca2+-dependent (Pu et al., 2016), and (2) retrograde movement during autophagosome maturation is dependent on Ca2+ released by TRPML1 (Li et al., 2016). Consistently, no defects in lysosome repositioning were observed in vamp7-deficient hemocytes. These findings therefore suggest that lysosomal centripetal movement during phagosome maturation is a Ca2+-dependent process, but it is independent of SNARE-dependent fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes.

Figure S3.

Lysosomal displacement during phagosome maturation. (A) Representative images of hemocytes before (A) and after (A’) 1 h of culture with fluorescently labeled bacteria. In both A and A', the outlier of the hemocytes is depicted by a white line, and acidic vesicles are labeled with LysoTracker (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 2 hemocytes/condition). Scale bar: 5 µm. (B) Relative dispersion of lysosomes with respect to cell radius before and after 1 h of bacterial exposure. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test (*, P < 0.05). (C) Lysosomal displacement with respect to cell radius. Data are presented as scatter dot plot, indicating mean ± SD; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P < 0.05). n.s., not significant. Cg, collagen Gal4 driver.

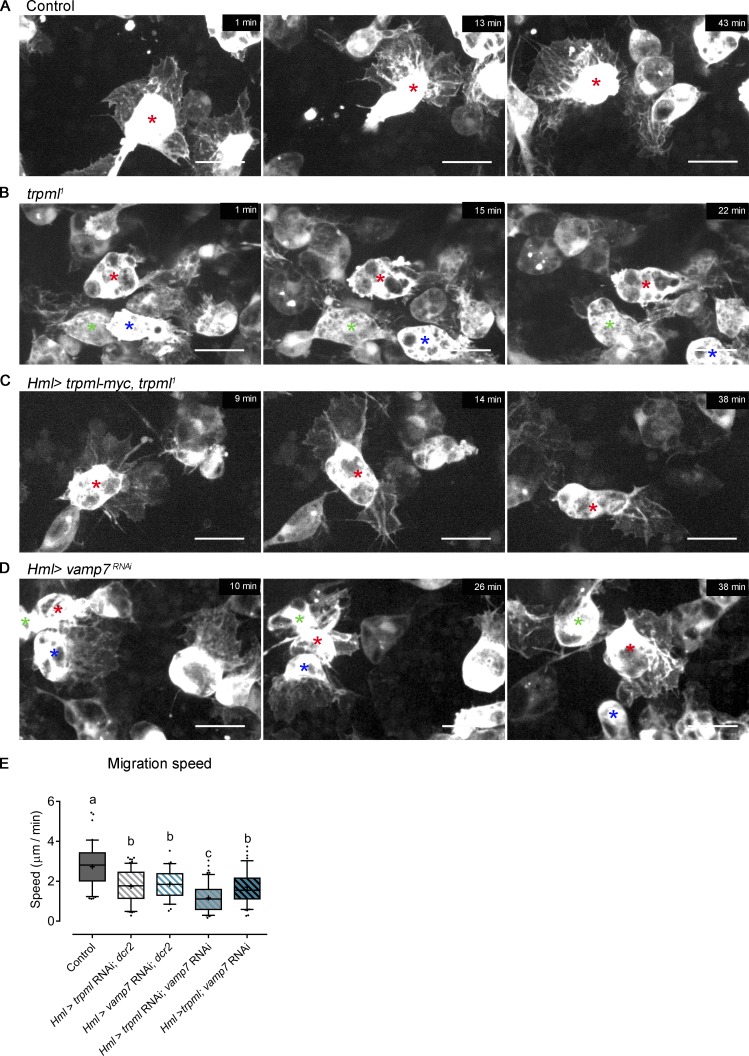

Next, we evaluated the effect of decreasing phagocytic processing on the migration of hemocytes in vivo. For this, we used pupal hemocytes, as during the pupal stage hemocytes are exposed to large amounts of cellular debris that result from metamorphosis-associated tissue remodeling. The phagocytic burden of pupal hemocytes is thus continuous (Banerjee et al., 2019). We observed that, as larval hemocytes, trpml-deficient pupal hemocytes accumulate more apoptotic corpses in their lysosomes than wild-type cells (Fig. S2 C). Tracking hemocyte migration on the basal membrane of the epithelium in the pupal thorax showed that control cells displayed an average speed of 2.7 ± 0.1 µm/min, consistent with results published by others for embryonic (Evans et al., 2013; Weavers et al., 2016) and pupal (Moreira et al., 2013) hemocytes. Remarkably, reducing phagocytic processing in these cells by knocking down trpml or vamp7 in the hemocytes significantly decreased their migration speed (1.6 ± 0.1 and 1.8 ± 0.1 µm/min, respectively) without altering their persistence, suggesting that neither Trpml nor Vamp7 modify hemocyte chemotaxis (Fig. 1, D and E). In all cases, cell trajectories were random, in agreement with previous findings made in wild-type hemocytes (Moreira et al., 2013). Accordingly, trpml-deficient hemocytes migrated significantly more slowly than controls upon pupal epithelium damage but presented no differences in directionality and were properly recruited to wound sites (Fig. 1, F and G).

Altogether, our results show that inhibiting phagocytic processing by altering lysosomal function impairs hemocyte migration speed, suggesting that these two processes may be coupled.

Trpml and Vamp7 regulate hemocyte migration through distinct mechanisms

We next investigated the mechanisms by which Trpml and Vamp7 control hemocyte migration using in vivo time-lapse imaging (Video 1). Tracking of EGFP-expressing pupal hemocytes showed that control cells displayed widespread protrusions at their front, which dynamically extended and retracted during motion (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, the leading edge of trpml1 hemocytes exhibited small and unstable protrusions, and their trailing edge showed frequent appearances of bleb-like structures (Fig. 2 B). Importantly, a normal protrusive capacity was observed when a trpml-myc construct was expressed in hemocytes of trpml1 mutant flies (Fig. 2 C), confirming that this Ca2+ channel regulates their protrusive activity in a cell-autonomous manner. No aberrant protrusions were observed in migrating vamp7-deficient hemocytes (Fig. 2 D), suggesting that Trpml and Vamp7 control hemocyte migration through distinct mechanisms. Consistent with this, hemocyte migration was significantly lower in trpml and vamp7 double knockdown compared with trpml or vamp7 individual knockdown conditions (Fig. 2 E). In addition, we found that overexpressing trpml in vamp7-deficient hemocytes did not rescue their migratory capacity. Therefore, stimulating Ca2+ release from lysosomes does not bypass vamp7 deficiency. As we evaluated hypomorphic conditions for Trpml and Vamp7, we cannot formally rule out that both proteins participate in the same pathway to regulate hemocyte migration. However, Trpml modulates hemocyte morphology during in vivo migration unlike Vamp7, which indicates distinctive roles for these proteins in hemocyte migration.

Video 1.

Pupal hemocyte migration in vivo. Time lapse showing migrating pupal hemocytes expressing cytoplasmic GFP, driven by the hemolectin (Hml) driver. Pupae collected at 16–17 h after pupae formation (APF) at 29°C. Time lapse: one image per minute. Display: 4 fps. Time is shown in minutes.

Figure 2.

Trpml and Vamp7 regulate hemocyte migration through different mechanisms. Representative frames of EGFP-labeled pupal hemocytes migrating in vivo (16 h ± 30 min APF). (A) Control hemocytes display a large lamella that changes its direction and morphology over time. (B) trpml1 hemocytes present fewer protrusions accompanied by the formation of bleb-like structures, as seen at the rear of the hemocyte labeled with a red asterisk. (C) Hemocyte-specific expression of trpml-myc rescues completely the mutant phenotype. (D) vamp7-deficient hemocytes present large protrusions and do not generate bleb-like structures. Asterisks of the same color indicate the same cell between frames. Scale bar in A–D: 10 µm (n = 3 independent experiments, n ≥ 2 animals/experiment). Full videos are shown in Video 1. (E) Pupal hemocyte migration speed (n ≥ 3 animals/condition, n ≥ 20 hemocytes/animal). Box and whiskers (5%–95%), where mean values are indicated as “+.” One-way ANOVA, with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P < 0.05). Hml, hemolectin Gal4 driver.

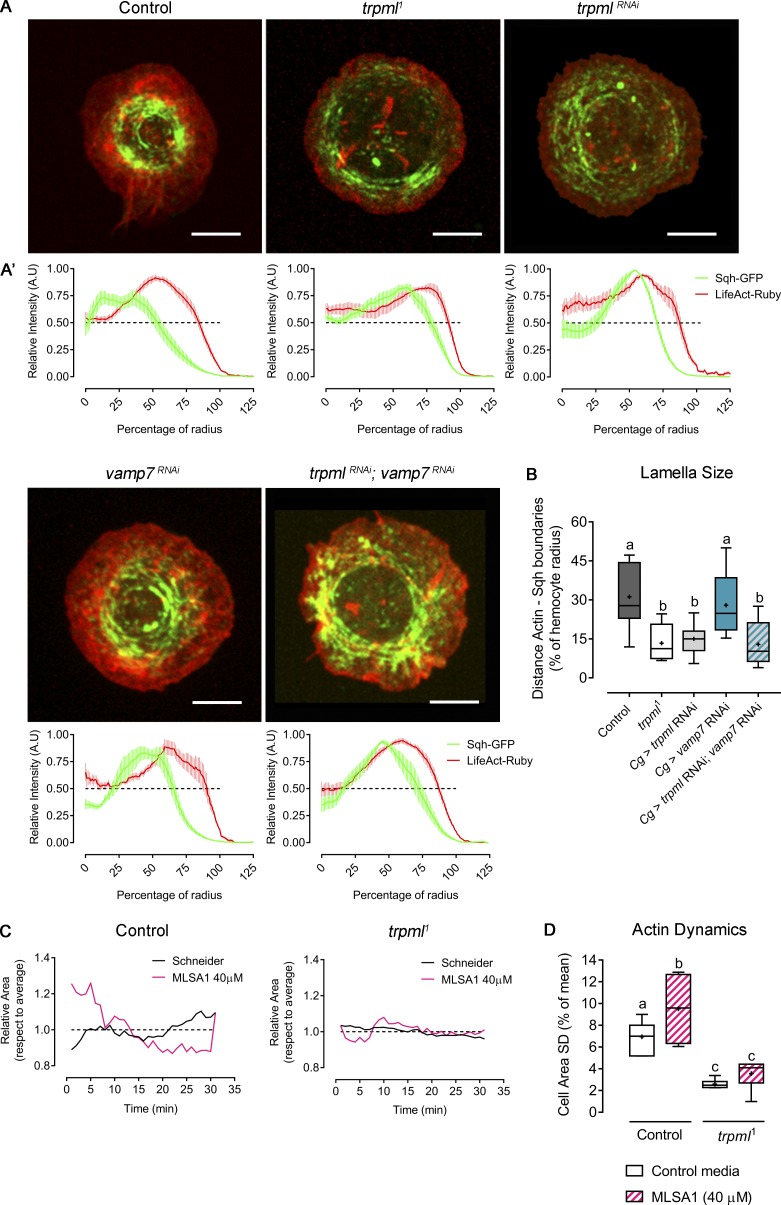

The aberrant protrusive phenotype of trpml-deficient hemocytes prompted us to investigate the role played by this Ca2+ channel in actin cytoskeleton organization. Therefore, we analyzed larval hemocytes in vitro, allowing better imaging resolution and less variation in hemocyte morphology. We generated primary cultures of hemocytes expressing LifeAct-Ruby, in which we observed that trpml-deficient cells exhibited a drastically reduced lamella size (13.3% of the radius in trpml1 hemocytes compared with 31.2% in control cells; Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, vamp7-deficient cells showed actin distribution and lamella size similar to that of controls (32.4% of the radius), and the double knockdown of trpml and vamp7 led to a similar actin phenotype as the trpml single knockdown (lamellae size: 12.9% versus 15% of the radius). This confirms that Trpml, but not Vamp7, plays an important role in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton.

Figure 3.

Trpml modulates actomyosin cytoskeleton structure and dynamics. (A) Representative images of larval hemocytes expressing LifeAct-Ruby and sqh-GFP. Shown conditions are control, trpml1 mutants and RNAi-mediated knockdown, vamp7 RNAi, and double trpml and vamp7 knockdown. Scale bar: 5 µm. (A’) Graphical distribution of LifeAct-Ruby and Sqh-GFP with respect to cell radius. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. A.U., arbitrary units. The dashed line marks the 50% of the maximal signal intensity. (B) Quantification of lamella size with respect to radius (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 3 cells/condition, 30 time points, 360°/cell). Cg, collagen Gal4 driver. (C) Actin dynamics in response to MLSA1 treatment in control and trpml1 hemocytes. Data are shown as changes in area over time with respect to average (dashed line). Full videos are included in Video 2. (D) Cell dynamics quantified as SD of the area over time (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 4 cells/condition, 30-min movies, 1-min intervals). The values in B and D are presented as box and whiskers, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Mean values are indicated as “+”; statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P < 0.05).

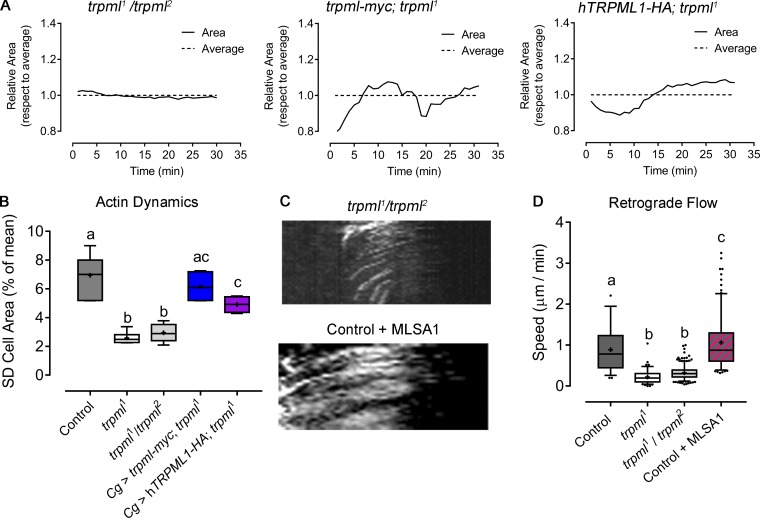

Live imaging of LifeAct-GFP–expressing larval hemocytes further showed that actin dynamics were also diminished in trpml1 hemocytes (Fig. 3 and Video 2). Dynamics were quantified as the SD of the hemocyte area over time (Fig. 3 D), which was more pronounced in controls (6.9% of the average) than in trpml1 cells (2.5% of the average), where lamellae were rather static. A similar phenotype was observed in trpml1/trpml2 hemocytes, which was fully rescued upon expression of Drosophila trpml and partially by its human orthologue (Fig. S4, A and B).

Video 2.

Trpml-dependent actin dynamics. Actin dynamics in hemocytes expressing LifeAct-GFP cultured ex vivo either in Schneider’s medium alone or supplemented with 40 µM of MLSA1. Time lapse: one image per minute. Display: 4 fps. Time is shown in minutes.

Figure S4.

Complementation and genetic rescue of trpml1 phenotypes in actomyosin cytoskeleton. Fluorescently labeled hemocytes were cultured ex vivo, and cytoskeleton dynamics were assessed. (A) Cell dynamics in LifeAct-GFP–expressing hemocytes: trpml1/trpml2 trans-heterozygotes and trpml1 mutants expressing Drosophila trpml-myc transgene or human orthologue TRPML1-HA. Data are shown as changes in area over time with respect to average (dashed line). (B) Cell dynamics quantified as SD of the area over time (n = 3 independent experiments, n ≥ 4 cells/condition, 30-min movies, 1-min intervals). Cg, collagen Gal4 driver myc and HA, c-myc and hemagglutinin epitopes. (C) Sqh-GFP kymographs showing retrograde flow of hemocytes (30-min movies, 1-min intervals, 360°/cell): trpml1/trpml2and control supplemented with 40 µM MLSA1. (D) Retrograde flow speed quantification (n = 3 independent experiments, n ≥ 3 cells/condition). (B and D) Values are presented as box and whiskers (5%–95% in D), one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Mean values are indicated as “+”; statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P < 0.05).

So far, our results show that Trpml is required for phagocytic processing and may control hemocyte migration by regulating the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton. To investigate whether the function of Trpml in cytoskeleton dynamics is the result of its ability to release Ca2+ from lysosomes, we treated hemocytes with the Trpml agonist MucoLipin Synthetic Agonist 1 (MLSA1). The efficiency of this drug in stimulating Ca2+ release from lysosomes was assessed by expressing the GCaMP5.T Ca2+-sensor fused to the channel itself (Wong et al., 2017) in hemocytes (Video 3). We found that MLSA1 enhanced actin dynamics of control hemocytes, indicating that gating of the channel controls actin dynamics, most likely by the efflux of Ca2+ from the lysosomes. As expected, the agonist had no effect on trpml1 hemocytes, thus showing its specificity (Fig. 3 D).

Video 3.

MLSA1-induced lysosomal Ca2+ release. Hemocyte cultured ex vivo expressing LifeAct-Ruby and trpml-GCaMP5 to demonstrate effectivity of MLSA1 on Trpml. Agonist was added after 5 min of culture. Time lapse: two images per minute. Display: 4 fps. Time format is mm:ss.

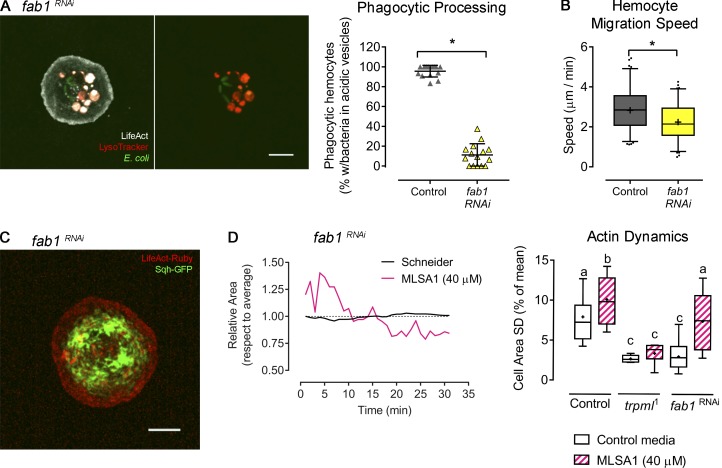

The activation of Trpml relies on acidic lysosomal pH as well as the presence of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2), a low-abundance phosphoinositide present in late endosomal/lysosomal compartments (Dong et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2014a). The synthesis of PI(3,5)P2 is catalyzed by the evolutionarily conserved PI 5-kinase PIKfyve/Fab1 (Dove et al., 2009), which regulates endolysosomal and phagosomal maturation in murine macrophages (Kim et al., 2014) and human neutrophil migration (Dayam et al., 2017). We found that Fab1 was required for proper phagocytic processing as well as efficient hemocyte migration in vivo (Fig. S5 A). Consistent with this result, actomyosin distribution and dynamics in fab1-deficient hemocytes phenocopied the ones observed in trpml1 mutant hemocytes (Fig. S5, C and D; and Video 4). Noticeably, we were able to bypass fab1 deficiency in actin dynamics by inducing the activation of Trpml upon the addition of its agonist MLSA1 (Fig. S5 D).

Figure S5.

PIK-fyve (fab1) knockdown phenocopies Trpml deficiencies. Hemocytes expressing fab1 RNAi were cultured ex vivo to evaluate phagocytic processing and cytoskeleton dynamics. (A) Left: Representative image of a fab1-deficient hemocyte cultured with fluorescently labeled bacteria and LysoTracker probe. Scale bar: 5 µm. Right: Phagocytic processing was quantified as the percentage of hemocytes containing bacteria within at least two acidic vesicles after 1 h of culture (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 20 hemocytes/condition). t test (*, P value < 0.05). (B) Hemocyte migration speed quantification (n = 3 independent experiments, n ≥ 2 animals/experiment). t test (*, P < 0.05). (C) Representative image of a larval hemocyte expressing LifeAct-Ruby and sqh-GFP, as well as fab1 RNAi. Scale bar: 5 µm (D) Left: Actin dynamics in response to MLSA1 treatment in fab1-deficient hemocytes. Data are shown as changes in area over time with respect to average (dashed line). Right: Actin dynamics quantified as SD of the area over time (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 4 cells/condition, 30-min movies, 1-min intervals). One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test; statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P value < 0.05). Full videos are included in Video 4. The values in A are shown as scatter dot plot, indicating mean ± SD, and values in B and D as box and whiskers, where “+” indicates mean values.

Video 4.

Actin dynamics in fab1-deficient hemocytes. Larval hemocytes cultured ex vivo expressing LifeAct-GFP and fab1 RNAi to demonstrate actin dynamics in both control media and supplemented with MLSA1. Time lapse: one image per minute. Display: 4 fps. Time is shown in minutes.

In sum, our results strongly suggest that Trpml controls hemocyte migration by regulating the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton, whereas Vamp7 uses a distinct mechanism.

Trpml specifically controls actomyosin contractility and force generation

A link between actin organization and Ca2+ dynamics is Myo-II, whose activity is controlled by the calmodulin-responsive Myosin Light Chain Kinase (MLCK; Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2009; Somlyo and Somlyo, 2003). We therefore analyzed the effect of Trpml on the localization and dynamics of the motor protein using the sqh-GFP (spaghetti squash, myosin light chain homologue in Drosophila) transgene (Pinheiro et al., 2017). These experiments showed that the subcellular distribution of Myo-II was altered in trpml-deficient hemocytes: While Myo-II accumulated at the center in control cells, it showed peripheral distribution in trpml1 hemocytes (Fig. 3 A). No defect in Myo-II distribution was observed in vamp7-deficient hemocytes. In addition, the centripetal retrograde flow of Myo-II was considerably reduced in trpml RNAi and mutant cells (Fig. 4, A and B; and Video 5). These findings are consistent with our previous report highlighting a correlation between TRPML1 activity and Myo-II retrograde flow in mouse dendritic cells (Bretou et al., 2017). Accordingly, MLSA1 treatment of control cells led to a considerable increase in the retrograde flow of Myo-II (Fig. S4, C and D). Altogether, these results show that Trpml controls Myo-II localization and dynamics in hemocytes.

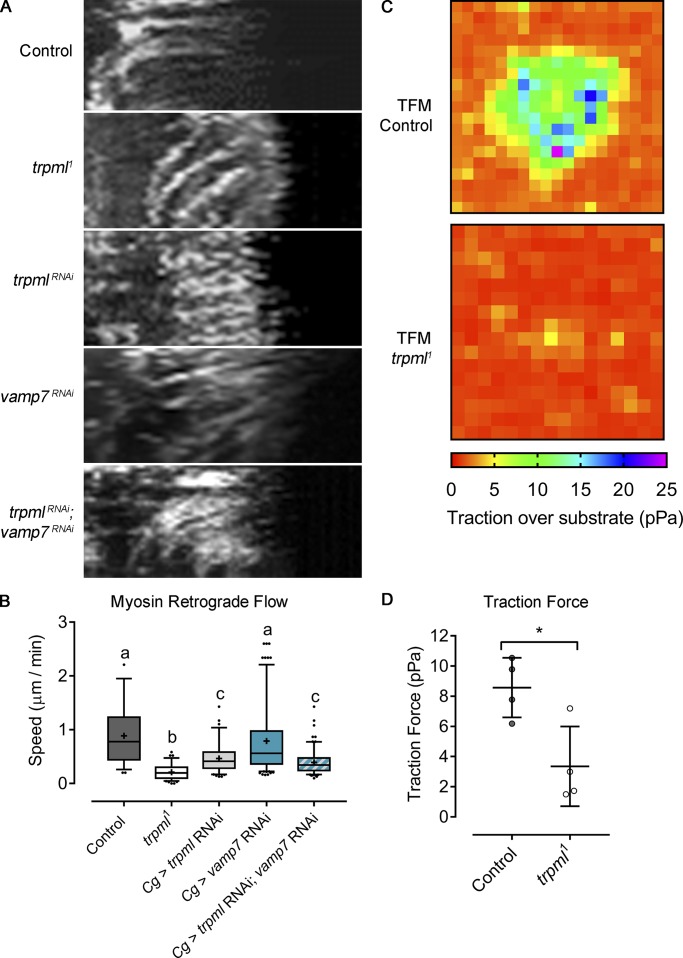

Figure 4.

Trpml controls actomyosin contractility and force generation. (A) Sqh-GFP kymographs showing retrograde flow of evaluated conditions (30-min movies, 1-min intervals, 360°/cell). Full videos are included in Video 5. (B) Sqh-GFP retrograde flow speed quantification (n ≥ 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 3 cells/condition). Values are presented as box and whiskers (5%–95%), one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisonspost hoc test. Mean values are indicated as “+”; statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P < 0.05). Cg, collagen Gal4 driver. (C) Traction force microscopy (TFM) heat maps of control and trpml1 cells plated on a substrate with 500-Pa stiffness. Videos showing bead displacement are included in Video 6. (D) Quantification of the forces exerted by the hemocytes on average over 15-min movies (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 1 cell/condition). Values are presented as scatter dot plot, indicating mean ± SD t test (*, P < 0.05).

Video 5.

Trpml-dependent Myo-II dynamics. Myo-II retrograde flow dynamics in hemocytes expressing sqh-GFP cultured ex vivo. Time lapse: one image per minute. Display: 4 fps. Time is shown in minutes.

The involvement of Trpml in Myo-II localization and dynamics suggests that this channel is needed to generate traction forces, which are required for forward movement (Chi et al., 2014). To measure these forces, we used a traction force microscopy approach. LifeAct-GFP–expressing hemocytes were cultured on a substrate exhibiting a stiffness of 500 Pa, in which fluorescently labeled beads were embedded. Traction forces were calculated from the analysis of bead displacement within the gel (Martiel et al., 2015). Our results indicate that trpml1 hemocytes exerted significantly smaller forces on the gel than control cells: 3.4 pPa and 8.6 pPa, respectively (Fig. 4, C and D; and Video 6). Trpml therefore emerges as a key regulator of actomyosin contractility and force generation in Drosophila macrophages.

Video 6.

Traction force microscopy. Hemocytes expressing LifeAct-GFP (right panel) were cultured ex vivo and plated on a deformable substrate coated in fluorescently labeled beads (left panel). Substrate deformability is revealed by bead displacement. Time lapse: two images per minute. Display: 4 fps. Time format is mm:ss.

Trpml regulates lysosome and Myo-II polarization

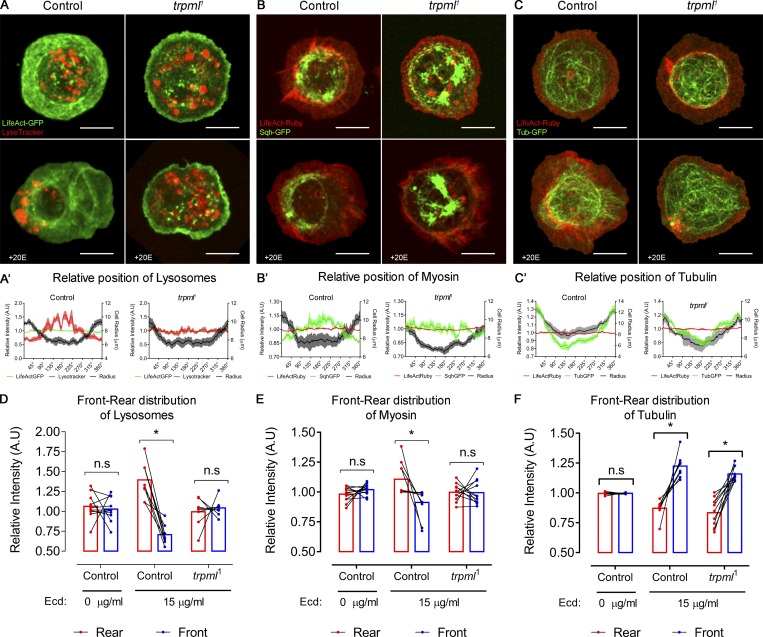

Our results show that Trpml-dependent Ca2+ release from lysosomes leads to Myo-II activation and traction force generation in cultured Drosophila larval hemocytes. To gain insights into the mechanisms by which Trpml and lysosomal Ca2+ regulate Myo-II in polarized cells, we relied on a recent method we developed that allows studying symmetry breaking in hemocytes in vitro (Edwards et al., 2018). We observed that in nonpolarized hemocytes, Myo-II as well as lysosomes were dispersed throughout the cell in wild-type and trpml1 mutant conditions (Fig. 5, A and B). Upon hemocyte polarization (i.e., with a roundness index < 0.9), both Myo-II and lysosomes relocalized at the cell rear (opposite pole than the one that undergoes lamella extension). Strikingly, such relocalization events were not observed in trpml1 hemocytes, in which lysosomes remained dispersed and Myo-II remained at the periphery of the cells. Similar results were obtained when monitoring lysosome repositioning during phagosome maturation (Fig. S3). Importantly, the distribution of microtubules was unaffected in trpml1 hemocytes (Fig. 5 C), as they extended toward the lamella in both control and mutant cells. This result dismisses a scenario where Trpml controls lysosome subcellular localization by regulating the structure of the microtubule network, where lysosomes traffic (Cabukusta and Neefjes, 2018). We conclude that Ca2+ released by Trpml is needed for hemocytes to break symmetry and acquire a polarized phenotype with both lysosomes and Myo-II localized at the cell rear.

Figure 5.

Trpml is important for lysosome polarization and myosin nucleation in polarized hemocytes. Representative images of hemocytes expressing (A) LifeAct-GFP stained with LysoTracker probe, (B) LifeAct-Ruby and sqh-GFP, and (C) LifeAct-Ruby and tubulin-GFP. (A–C) Both control and trpml1 conditions are shown. The upper panels are untreated, whereas the lower panels correspond to polarized hemocytes treated with 15 µg/ml of 20-hydroxyecdysone (+20E). Scale bar: 8 µm. (A’–C’) Graphical distribution in 360° of (A’) lysosomes, (B’) myosin, and (C’) tubulin, where 0° = 360°, corresponds to the intersection with the longest axis at the leading edge in a polarized hemocyte. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (D–F) Front 90° signal compared with the rear 90°, revealing asymmetric distribution of (D) lysosomes, (E) myosin, and (F) tubulin (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 2 cells/condition). Two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test (*, P value < 0.05). n.s., not significant. All data points are shown with a line connecting the rear and front signal intensities of each hemocyte. Bars represent mean relative intensity of signal distributes at the cell rear (red) and front (blue). A.U., arbitrary units; Ecd., ecdysone.

Trpml regulates cell migration by activating Myo-II

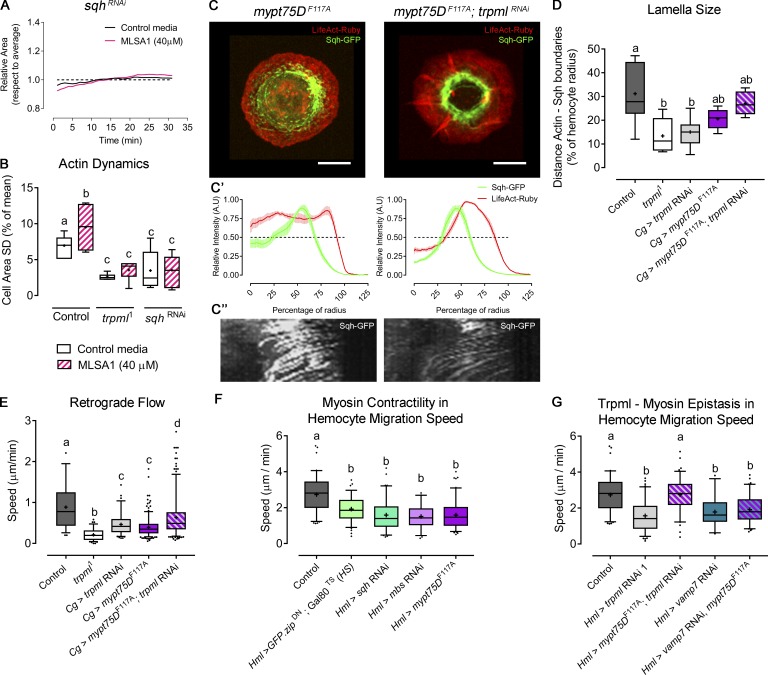

Altogether, our results suggest that Trpml transports Ca2+ from lysosomes to the cytosol where this second messenger activates Myo-II, which in turns enhances actin dynamics and eventually promotes cell migration. To test this hypothesis, we first evaluated the effect of Trpml activation in a Myo-II–deficient background. sqh-deficient hemocytes showed reduced actin dynamics, to levels comparable to the ones measured in trpml1 hemocytes (Fig. 6 A). Notably, treatment of these cells with MLSA1 did not restore the wild-type phenotype (Fig. 6 B), showing that Myo-II deficiency cannot be rescued by Trpml activation. We then generated hemocytes with enhanced Myo-II activity. For this, we modulated the activity of the trimeric enzyme myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP), which is responsible for Myo-II dephosphorylation and inactivation. Particularly, we expressed the dominant-negative version of one of its components, Mypt75D (myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 75D): mypt75DF117A, which leads to increased phosphorylated Sqh levels in vitro and in vivo (Vereshchagina et al., 2004). Overactivation of Myo-II significantly increased lamella size of trpml knockdown hemocytes (Fig. 6, C and D), reaching levels observed in controls. Similarly, Sqh-GFP retrograde flow increased when expressing the mypt75DF117A mutant in a trpml-deficient background (Fig. 6 E). These data therefore confirm that Trpml acts upstream of Myo-II in the regulation of actomyosin localization and dynamics in cultured hemocytes.

Figure 6.

Myo-II activation rescues trpml phenotype in cytoskeleton and hemocyte migration. (A) Cell dynamics in response to MLSA1 treatment in sqh-deficient hemocytes. Data are shown as changes in area over time with respect to average (dashed line). (B) Actin dynamics quantified as SD of the area over time (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 4 cells/condition, 30-min movies, 1-min intervals). Full videos are included in Video 2. (C) Representative images of hemocytes expressing LifeAct-Ruby and sqh-GFP in the conditions mypt75DF117A and trpml RNAi with mypt75DF117A. Scale bar: 5 µm. (C’) Graphical distribution of LifeAct-Ruby and Sqh-GFP with respect to cell radius. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. A.U., arbitrary units. The dashed line marks the 50% of the maximal signal intensity. (C'') Kymographs showing Sqh-GFP retrograde flow over time (30 time points, one frame per minute): mypt75DF117A (left) and trpml RNAi with mypt75DF117A (right). (D) Quantification of lamella size with respect to the radius (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 3 cells/condition, 30 time points, 360°/cell). (E) Quantification of Sqh-GFP retrograde flow speed (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 3 cells/condition). Full videos are included in Video 5. (F) Pupal hemocyte migration speed showing that both increased and deficient Myo-II activity significantly decreases migration speed (n ≥ 3 animals/condition, n > 20 cells/animal). (G) Pupal hemocyte migration speed showing that mypt75DF114A rescues the speed in trpml- but not in vamp7-deficient hemocytes (n ≥ 3 animals/condition, n > 20 cells/animal). The values in B, D, and E–G are presented as box and whiskers (5%–95% in E–G), one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Mean values are indicated as “+”; statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P < 0.05). Hml and Cg stand for hemolectin and collagen Gal4 drivers, respectively. DN, dominant-negative; TS, thermo-sensitive; HS, heat shock.

We next investigated whether impaired Myo-II activation is responsible for the defective migration of Trpml-deficient fly macrophages in vivo. Remarkably, we found that hemocytes coexpressing trpml RNAi and mypt75DF114A exhibited migration speeds equivalent to the ones of control cells (Fig. 6 G). As expected, Myo-II deficiency generated by expressing sqh RNAi or a dominant-negative version of myosin heavy chain zipper (GFP-zipDN; Franke et al., 2005) led to a significant decrease in hemocyte migration speed (Fig. 6 F). The overactivation of Myo-II, achieved by decreasing the activity or levels of MLCP components (expression of mypt75DF114A or myosin binding subunit [mbs] RNAi) also led to decreased migration speeds, thereby revealing the importance of the fine regulation of Myo-II activity for efficient migration. Of note, coexpressing vamp7 RNAi and mypt75DF114A did not rescue the migration defect of vamp7-deficient hemocytes (Fig. 6 G), further supporting our conclusions showing that, unlike Trpml, Vamp7 regulates hemocyte migration through a Myo-II–independent mechanism. Hence, we propose that, unlike Vamp7, Trpml controls hemocyte migration by promoting Sqh phosphorylation and Myo-II activation, thereby triggering actomyosin contractility.

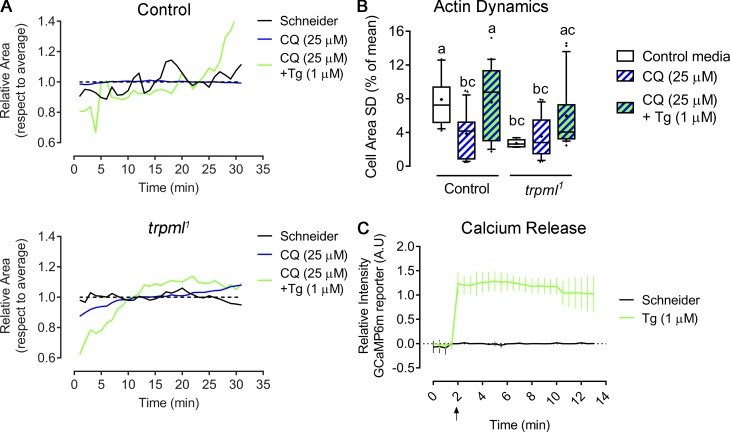

We next investigated whether local release of Ca2+ from lysosomes was critical for Myo-II activation, as opposed to global increase of Ca2+ cytosolic levels. For this, we cultured larval hemocytes ex vivo with chloroquine, a drug that alkalinizes lysosomes, thus reducing lysosomal Ca2+ release by Trpml, but does not alter the release of other Ca2+ stores such as the ER. We observed a significant decrease in actin dynamics in control cells treated with chloroquine, whereas no major changes were observed in trpml1hemocytes (Fig. S6; and Video 7 and Video 8), suggesting that lysosomes are the Ca2+ stores required for actomyosin dynamics. Accordingly, inducing a generalized Ca2+ release from the ER with thapsigargin (a specific irreversible inhibitor of ER Ca2+-ATPase) partially rescued actomyosin dynamics at early time points. Indeed, thapsigargin-treated hemocytes rapidly became static, exhibiting numerous filopodia-like extensions that might result from an unbalanced accumulation of phosphorylated myosin light chain forms as previously shown (Watanabe et al., 1998), supporting our results indicating that the dysregulation of both inactive and active forms of Myo-II impair efficient hemocyte migration in vivo (Fig. 6 F).

Figure S6.

Localized calcium release from lysosomes is required for cytoskeleton normal dynamics. (A and B) Hemocytes expressing LifeAct-GFP were cultured ex vivo for 1 h in control media or supplemented with chloroquine (CQ; 25 µM), after which media were changed to the same as the initial or containing thapsigargin (Tg; 1 µM), and recording began immediately. (A) Representative changes of cell area over time with respect to average (dashed line) in both control and trpml1 hemocytes. Full videos are included in Video 7. (B) Actin dynamics quantified as SD of the area over time (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 4 cells/condition, 30-min movies, 1-min intervals). Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons post hoc test; statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P < 0.05). (C) GCaMP6(m) calcium reporter was expressed in hemocytes and registered ex vivo to reveal intracellular calcium release upon the addition of thapsigargin (at minute 2). Values are normalized against the first time point (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 6 cells/condition, 12-min movies, 30-s intervals). A.U., arbitrary units. Full video is included in Video 8.

Video 7.

Chloroquine (CQ) and thapsigargin (Tg) treatment. Larval hemocytes cultured ex vivo expressing LifeAct-GFP pretreated with CQ for 1 h. Culture medium during recording of videos was either CQ or Tg. Time lapse: one image per minute. Display: 4 fps. Time is shown in minutes.

Video 8.

Thapsigargin (Tg)-induced cytosolic Ca2+ release. Hemocyte cultured ex vivo expressing LifeAct-Ruby and GCaMP6m to demonstrate calcium release into the cytosol after Tg addition. Time lapse: two images per minute. Display: 3 fps. Time format is mm:ss.

Altogether, our results suggest that regulated and localized Ca2+ release from the lysosomes, through Trpml, promotes Sqh phosphorylation, triggering localized actomyosin contractility and thus allowing efficient hemocyte migration.

Trpml regulates phagocytic processing and hemocyte migration through distinct mechanisms

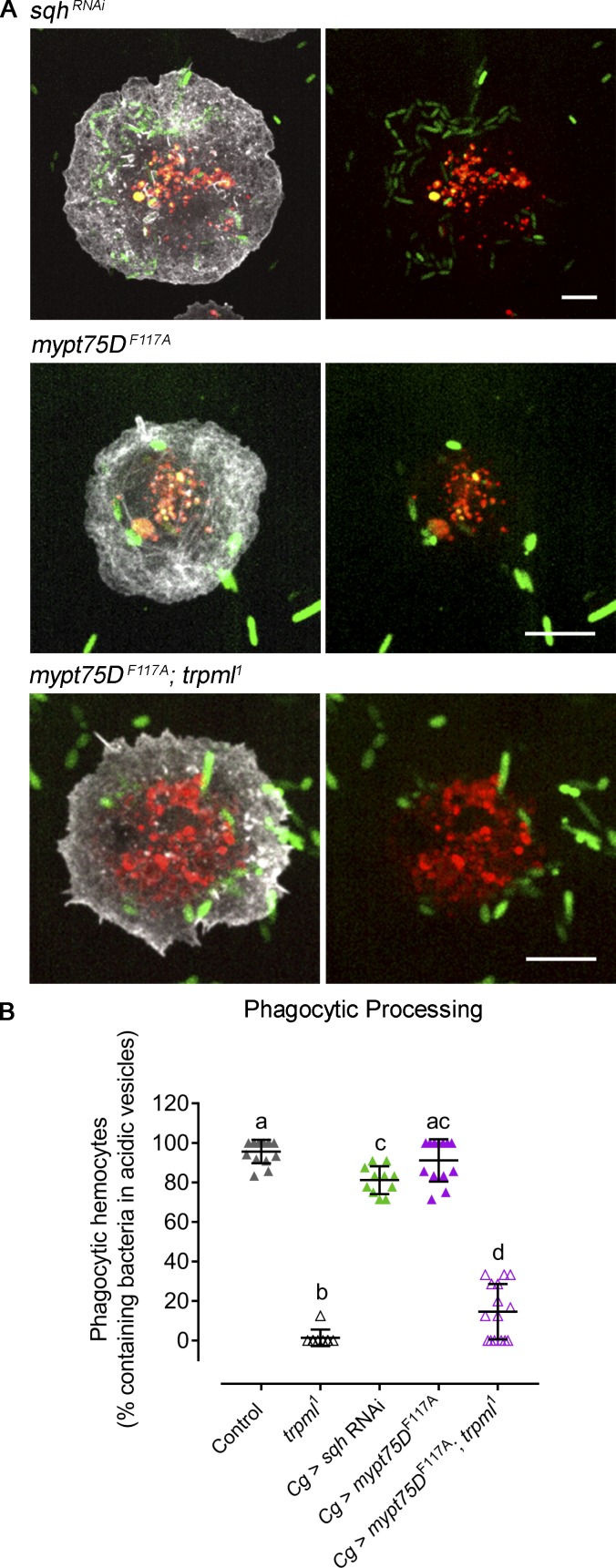

Having found that the release of lysosomal Ca2+ by Trpml is essential for Myo-II activation and hemocyte migration, we finally assessed whether this motor protein is also involved in the Trpml-dependent regulation of phagocytic processing. Modulation of Myo-II activity, either by decreasing its levels or increasing its activity, did not alter the capacity of hemocytes to process the content of phagosomes (Fig. 7), suggesting that Myo-II is not involved in phagosome maturation in this system. Accordingly, mypt75DF114A expression did not rescue the defect in phagocytic processing of trpml1 mutant cells. Thus, Myo-II acts downstream of Trpml to control hemocyte migration, but not the ability of these cells to process their phagosomal content.

Figure 7.

The role of Trpml in phagocytic processing is independent of Myo-II activity. (A) Representative images of LifeAct-GFP–expressing hemocytes cultured during 1 h with fluorescently labeled bacteria and LysoTracker probe. Evaluated conditions are Myo-II deficiency by expressing sqh RNAi, Myo-II overactivation by expressing mypt75DF117A in a control, and trpml1 genetic background. Scale bar: 5 µm. Note that the bar is smaller in sqh-deficient hemocytes, as the cells present defects in cytokinesis and are larger. (B) Phagocytic processing quantified as the percentage of hemocytes containing bacteria within at least two acidic vesicles after 1 h of culture (n = 3 independent cultures, n ≥ 20 hemocytes/condition). Data are presented as scatter dot plot, indicating mean ± SD, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Mean values are indicated as “+”; statistically equivalent values are represented with the same letter (P value < 0.05). Cg, collagen Gal4 driver.

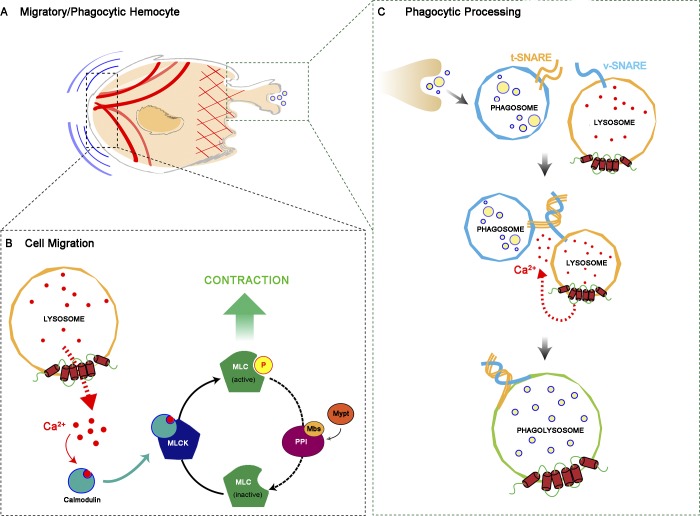

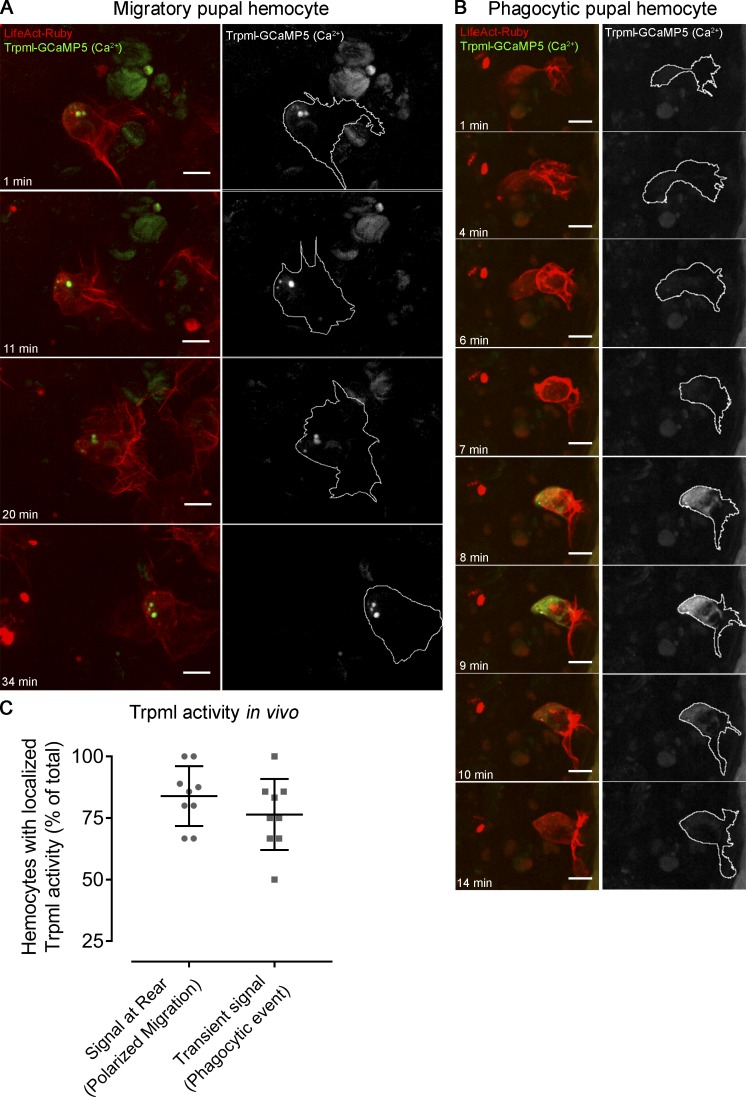

Altogether, these results are consistent with a model (Fig. 8) in which, in the context of phagocytosis, Ca2+ release through Trpml facilitates the fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes in a Myo-II–independent manner, most likely by positioning these acidic organelles to the cell front where phagocytosis occurs in vivo, as well as allowing the SNARE-dependent fusion itself (prior formation of the trans-SNARE complex, wherein Vamp7 is the main player in the lysosomal membrane). In contrast, in the context of cell migration, Trpml would be responsible for the polarization of lysosomes to the cell rear, allowing local delivery of Ca2+, thus activating MLCK, which in turn phosphorylates Sqh, enhancing actomyosin contractility for hemocytes to undergo symmetry breaking and generate the traction forces needed for their migration. To test the validity of this model in vivo, we expressed the Trpml activity reporter trpml-GCaMP5.T (Wong et al., 2017) in pupal hemocytes, together with the cytoskeleton marker LifeAct-Ruby, and monitored their dynamics by time-lapse imaging. Because we did not obtain a good signal-to-noise ratio when expressing the reporter using our hemocyte-specific drivers, we randomly generated clones (Struhl and Basler, 1993) with a strong expression of both the reporter and the cytoskeleton marker LifeAct-Ruby (Video 9). In these clones, lysosomal Ca2+ release was mainly detected at the rear of migrating cells. Remarkably, while Ca2+ release was sustained and continuous at the cell rear (Fig. 9 A), it rather showed transient signals at nascent actin-rich structures resembling phagocytic cups/phagosomes (Fig. 9 B). The proportion of cells with localized Trpml activity at the rear in migrating hemocytes reached 83.9%, and hemocytes presenting transient spikes of Trpml activity following a phagocytic event corresponded to 76.5% of the total cell population (Fig. 9 C). Altogether, these results are consistent with a dual role of TRPML in both phagocytic processing and cell migration, which allows coupling these two processes in space and time.

Figure 8.

Dual mechanism model for the activity of Trpml. (A) Diagram of a cell that either migrates or engulfs cell debris. (B) When the hemocyte is migrating, the lysosomes displace toward the rear, releasing calcium ions locally, which bind calmodulin and activate Myosin Light Chain Kinase (MLCK), which in turn phosphorylates Sqh (MLC). The counterbalance is regulated by the Myosin Light Chain Phosphatase (MLCP) trimeric complex, composed of Protein Phosphatase 1β (PPIβ), Myosin binding subunit (Mbs) and Myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 75D (Mypt). (C) After closure of the phagocytic cup, the phagosome is formed and fuses with the lysosome via v-SNARE (Vamp7) and t-SNARE complex formation in a calcium-dependent manner, generating the phagolysosome. Here, the engulfed material is degraded by the action of lysosomal proteases.

Video 9.

Trpml activity in vivo. Pupal hemocytes migrating in vivo expressing LifeAct-Ruby and Trpml-GCaMP5 to reveal Trpml activity in vivo during cell migration (upper panel) and upon a phagocytic event (lower panel). Time lapse: one image per minute. Display: 3 fps. Time is shown in minutes.

Figure 9.

Trpml activity in vivo. Representative images of mitotic clones labeling pupal hemocytes expressing LifeAct-Ruby and calcium sensor trpml-GCaMP5, revealing the activity of the channel in vivo. (A) Migrating hemocyte containing signal at the rear, which perdures over time, suggesting activity of Trpml from the lysosomes. (B) Hemocyte generating a protrusion where transient spikes of activity arise, which probably corresponds to a phagocytic event. Scale bar in A and B: 10 µm. Full videos are included in Video 9. (C) Proportion of migrating cells with signal at the rear and transient spikes of activity upon engulfment. Values are presented as scatter dot plot indicating mean ± SD (n ≥ 4 independent experiments, n ≥ 2 pupae/experiment).

Discussion

Here, we show that the migration and phagocytic processing of D. melanogaster hemocytes are regulated by a common player: the lysosomal Ca2+ channel Trpml. However, two different mechanisms are at work: While Trpml promotes cell migration and force generation by enhancing actomyosin contractility, it controls phagocytic processing through a Myo-II–independent mechanism. This latter process likely involves the transport of lysosomes needed for their fusion with phagosomes, as this event was shown to rely on intracellular Ca2+ (Pu et al., 2016). Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed transient events of lysosomal Ca2+ release at the cell front in close apposition to phagocytic cups/phagosomes in migrating hemocytes in vivo, as well as impaired lysosome positioning in trpml-deficient cells in vitro.

Impaired lysosomal positioning and thus phagolysosomal fusion in trpml1 mutant hemocytes might be independent of Myo-II activity and of the structure of the microtubule network, rather resulting from the reduced lysosomal Ca2+ release itself, decreasing the association of ALG2 with the minus-end–directed dynactin–dynein motor, as described for autophagosome maturation (Li et al., 2016). Alternatively, it may result from a lysosome-intrinsic defect, for example, a less acidic lysosomal pH that may affect the recruitment of cytosolic molecules involved in the intracellular transport of these organelles (Johnson et al., 2016).

Noticeably, we could rescue the migratory phenotype of trpml-deficient hemocytes by promoting the accumulation of active phosphorylated Sqh molecules. Inversely, the Trpml agonist MLSA1 activates Myo-II–dependent contractility in control, but not in sqh-deficient, hemocytes. These data indicate that Trpml acts upstream of Myo-II, activating the motor protein by releasing lysosomal Ca2+ at the rear of migrating hemocytes. This is consistent with our previous findings in mouse dendritic cells, in which Myo-II retrograde flow and migration speed were decreased in the absence of this Ca2+ channel (Bretou et al., 2017). It is also in agreement with results from others showing that the kinase in charge of Myo-II phosphorylation, MLCK, is activated in a calmodulin-dependent manner (Swulius and Waxham, 2008). It therefore appears that lysosomes constitute an essential source of intracellular Ca2+ used for the activation of cell contractility. It might allow the regulated and local stimulation of the motor protein compared with bigger Ca2+ stores such as the ER. In addition, it allows delivering a signal specifically in response to ingestion of extracellular material, which might be particularly relevant for phagocytes in charge of tissue patrolling. Lysosome signaling therefore emerges as a key regulatory pathway in immune cells that use endocytosis, phagocytosis, or macropinocytosis to probe their environment.

We show that decreasing the levels of PIKfyve kinase, which produces PI(3,5)P2 at late endosomal/lysosomal membranes, mimics the phenotypes of trpml-deficient hemocytes: They were unable to degrade engulfed bacteria, they migrate more slowly, and they display reduced actomyosin dynamics. Interestingly, we could bypass PIKfyve deficiency in actin dynamics by the addition of the Trpml activator MLSA1, which is inconsistent with a previous report stating that Drosophila Trpml activation by MLSA1 requires PI(3,5)P2 (Feng et al., 2014b). However, considering that we used RNAi-mediated knockdown, we cannot rule out that some remnant PIKfyve generates sufficient amounts of PI(3,5)P2 for MLSA1 to exert its activating effect.

Our study suggests that lysosomal Ca2+ released by Trpml may allow hemocytes to couple the processing of internalized extracellular material with their locomotion, thereby facilitating tissue exploration for the presence of danger signals such as apoptotic debris or microbial agents. Different defects in lysosomal function have been shown to compromise immune cell migration in Drosophila hemocytes (Evans et al., 2013), zebrafish macrophages (Berg et al., 2016), mouse dendritic cells (Chabaud et al., 2015), neutrophils, and lymphocytes (Colvin et al., 2010), as well as in human cancer cells (Palamidessi et al., 2008). Remarkably, we found that Trpml impacts hemocyte migration through a pathway distinct from the one that involves Vamp7, as no defect in the actomyosin cytoskeleton was observed in hemocytes deficient for this SNARE protein. At this stage, it is still unclear exactly how vamp7 deficiency leads to impaired hemocyte migration. Nonetheless, our data highlight that Vamp7 acts through a pathway distinct from the one involving Trpml, indicating that multiple mechanisms might have emerged to couple extracellular material uptake to phagocyte migration, suggesting the existence of a strong evolutionary pressure to couple these two processes. Consistent with this hypothesis, we previously showed that macropinocytosis and cell locomotion are also coupled in migrating dendritic cells, which facilitates the coupling of these two processes in time and space to ensure optimal environment patrolling (Chabaud et al., 2015). Future work aiming to identify additional molecular players involved in the coupling of phagocytic processing should improve understanding of the role that this coupling plays in tissue development and immunity in different organisms.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks

All experiments were performed with D. melanogaster strains acquired from Bloomington or Vienna Drosophila Stock Centers unless otherwise indicated: HmlΔ-Gal4 (BDSC:30141), Cg-Gal4 (BDSC:7011), UAS-LifeAct.GFP (BDSC:35544), UAS-LifeAct.Ruby (BDSC:35545), HmlΔ>2xEGFP (BDSC:30140), Ubi::Cad.GFP, Srp>Gal4, UAS-GFP/CyO; Crq>Gal4, UAS-RedStinger (Weavers et al., 2016), sqh::sqh-3xGFP (Pinheiro et al., 2017), α-Tub-GFP (Grieder et al., 2000), DE-Cad.GFP, UAS-H2B.RFP/CyO (Huang et al., 2009), UAS-trpml-GCaMP.5T/TM6b (Wong et al., 2017), Hs::FLP; UAS-LifeActRuby/CyO, act::GFP; Act <FRT> Gal4, trpml1/TM6b (BDSC:28992), trpml2/TM6b (BDSC:42230), UAS-trpml (BDSC:27594), UAS-trpml-myc, trpml1/TM6b (BDSC:57372), UAS-TRPML1-HA; trpml1/TM6b (BDSC:57373), TRiP.JF01466 (BDSC:31673), TRiP.GL01524 (BDSC:43543), TRiP.HMS00521 (BDSC:32516), TRiP.HMS00437 (BL32439), UAS-GFP.zipDN (Franke et al., 2005), UAS-mypt75DF117A (BDSC:24099), Tub::Gal80TS (BDSC:7017), UAS-dcr2 (BDSC:24650), fab1 RNAi (VDRC:27591), and UAS-GCaMP6m (BDSC:42748).

Time-lapse imaging of pupal hemocytes

In all cases, pupae were collected at 0–1 h after puparium formation (APF) and kept in a humidified chamber at 25°C or 29°C depending on the case. 1 h before reaching desired developmental stage, pupae were mounted as described (Moreira et al., 2011). Briefly, pupae were placed ventral side down on double-sided sticky tape placed on a microscope slide, after which the pupal cuticle was removed from the thorax. On both sides around the pupae, 18 × 18–mm coverslips (#1; Menzel-Gläser) were piled together with nail polish (four on the posterior, and three in the anterior end of the pupae). Finally, a 24 × 40–mm coverslip (#1.5; Knittel Glass) was covered evenly with Voltalef 10S (24627.188; VWR Chemicals) and glued on the square coverslips with nail polish. When the desired developmental stage was reached, a time-lapse recording was performed in an inverted spinning disk confocal microscope (Zeiss), using 20× (NA 0.75) or 40× objective (oil immersion, NA 1.4), with a scientific Complementary Metal–Oxide–Semiconductor (sCMOS) camera (Hamamatsu), controlled by Metamorph software, at the same incubation temperature as before. In all cases, 25 slices separated by 0.5 µm were registered.

To evaluate migration speed, we used the stock DE-Cad.GFP, UAS-H2B-RFP/CyO; HmlΔ>Gal4. We collected and dissected 16 h ± 30 min APF pupae (29°C) and recorded in a 20× objective at 90-s intervals for 50 min at 29°C. Manual tracking was performed with ImageJ software, and Chemotaxis tool plugin was used to obtain migration speed.

To evaluate directed cell migration, we used the stock Ubi::Cad.GFP, Srp>Gal4, UAS-GFP/CyO; Crq>Gal4, UAS-RedStinger, crossed with either trpml RNAi or w1118 as control. We collected and dissected 16 h ± 30 min APF pupae (29°C). Using the epithelium as reference, we performed a circular wound at the lateral side of the animals, taking care to select an area without any hemocytes (wound size: 48.3 µm in diameter, depth: 4 µm, and repetitions: 10). We recorded in a 20× objective at 1-min intervals for 1 h at 29°C. Manual tracking was performed with ImageJ software, and Chemotaxis tool plugin was used to obtain migration speed and directionality. A final image was acquired 1 h after damage with a 40× objective.

To assess pupal hemocyte morphology during migration, we used the stock HmlΔ>2xEGFP, grown at 29°C and collected 17 h ± 30 min APF. We dissected the pupae and imaged using a 40× objective at 1-min intervals for 1 h. Z-stack projections and videos were performed with ImageJ.

To observe activity of Trpml in vivo, we generated FLP (Flippase)-out clones (Struhl and Basler, 1993) expressing the trpml-GCaMP5.T fusion construct and LifeAct-Ruby. Clones were generated with a 5-min heat shock (37°C) at 3 h APF, and recording was performed at 20 h APF (25°C) registering one image per minute.

In all cases, at least three independent experiments were performed, whereby at least two animals were registered simultaneously.

Infection with bacteria

Animals were punctured with tungsten filaments previously immersed in Schneider’s medium alone or containing bacteria (Escherichia coli DH5α, 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml). Third instar larvae were punctured in the dorsoposterior region, and adult females (1–3 d after eclosion) were punctured in the ventral side of the abdomen. Punctured animals were isolated in independent tubes, after which the eclosion rate and survival after 10 d was quantified for larvae and adults, respectively. Survival rate was determined as the percentage of animals that survived upon infection with respect to sterile puncture. Three independent experiments were performed, whereby at least 20 animals per condition were punctured.

Larval hemocyte isolation and primary culture

Third instar larvae were selected and thoroughly rinsed with successive PBS washes, after which they were transferred to glass-bottomed dishes (P35GC-1.5-10-C; MatTek) containing Schneider’s medium. All larvae were punctured in the dorsoposterior region with a fine tungsten filament, allowing the hemolymph to drain for 1 min, taking care to avoid rupturing any of the internal tissues. Larvae were then removed, and hemocytes were left to attach to the glass for 1 h at 25°C in a humidified dark chamber.

In most cases, initial culture medium was changed according to the case. Afterward, cells were registered at 25°C in an inverted spinning disk confocal microscope (Zeiss) using a 100× objective (oil immersion, NA 1.4) with an sCMOS camera controlled by Metamorph software. Optical slices of 0.2 µm were registered at intervals between 30 s and 10 min, depending on the case.

Pharmacological treatments

MLSA1 (4746; Tocris): In all cases, the agonist was added immediately before registration at a final concentration of 40 µM.

Chloroquine (C6628; Sigma): In all cases, culture medium supplemented with 25 µM chloroquine was used during hemocyte attachment and was kept during recording. Thus, recording began 1 h after drug exposure.

Thapsigargin (T9033; Sigma): The initial culture medium supplemented with 25 µM chloroquine during attachment was changed to 1 µM thapsigargin-containing medium immediately before recording.

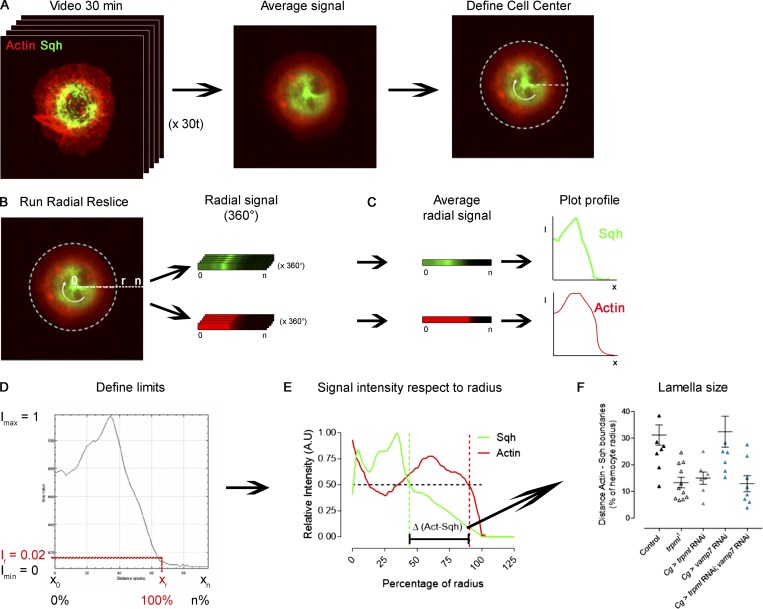

Cytoskeleton distribution and dynamics

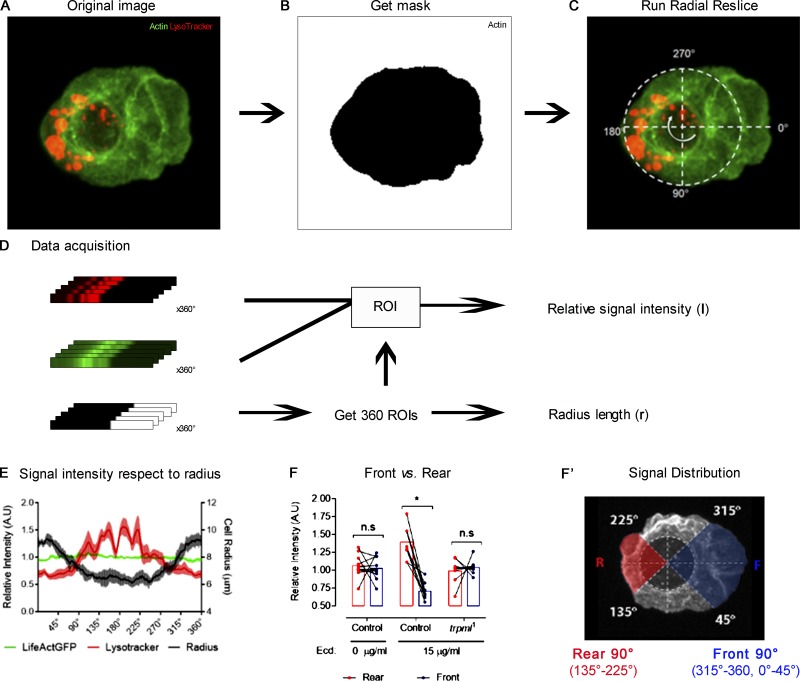

To determine actin and myosin cytoskeleton distribution in live hemocytes, we expressed LifeAct-Ruby together with sqh-GFP, registered for 30 min at 1-min intervals, and averaged the distribution of both channels in time (Fig. S7 A). We relied on the Radial Reslice plugin (ImageJ) to obtain the distribution in 360°. All 360° were averaged, and plot profiles of both signals with respect to the radius were obtained (Fig. S7, B and C). We normalized fluorescence intensity with respect to the maximal signal for each channel independently and defined as 100% of radius, where a signal corresponding to actin cytoskeleton became equivalent to the noise (below 0.02; Fig. S7 D). To determine the difference between myosin and actin territories, we plotted the signal intensity profile with respect to the radius (Fig. S7 E) and, in both cases, selected the point where signal intensity was equal to 0.5 and calculated the differences between both relative positions (percentage with respect to radius; Fig. S7 F).

Figure S7.

Image analysis pipeline for the determination of lamella size. Fluorescently labeled hemocytes were cultured ex vivo and registered for 30 min at 1-min intervals. (A) Representative image of a hemocyte expressing LifeAct-Ruby and sqh-GFP from a 30-min video (left), in which the signals of all frames were averaged (middle). On the average signal image, the center of the cell was defined (right). The white dashed line represents the adjusted circumference around the center of the cell. (B) The Radial Reslice plugin was run, obtaining the radial signal of both channels (360° of each), represented by the white round arrow. (C) All 360 linear signals were averaged, and a plot profile was obtained for each channel. (D) Obtained data for each plot profile were normalized: maximum signal intensity (Imax) was set to 1, and minimum (Imin) to 0. Each positional coordinate (x) has a defined intensity, where x0 corresponds to the center of the cell. The positional coordinate in the radial axis (xr) was set to 100% of the radius, whereby the signal intensity of the channel corresponding to actin cytoskeleton equaled 0.02 (Intensity radius, Ir), which is slightly above the noise. (E) Normalized values were plotted to demonstrate graphical distribution of signals, and positional identity was converted into percentage of the radius, where xr=100%. A.U., arbitrary units. The dashed line marks the 50% of the maximal signal intensity. These values were used to define the position of the boundaries of each signal. The difference between both boundaries was used to define lamella size (black bracket). (F) To quantitatively compare signal distributions among conditions, the difference (percentage with respect to the radius) of both signals at I = 0.5 (in E) was used as lamella extension beyond Sqh territory. Cg, collagen driver; Act, actin.

To determine retrograde flow speed, we used sqh-GFP–expressing hemocytes and recorded them during 30 min at 1-min intervals. Radial Reslice and Kymograph plugins were combined to obtain radial signal changes over time, allowing calculation of retrograde flow speed at all 360°.

To calculate actin polymerization in the lamellae, we recorded LifeAct-GFP–expressing hemocytes during 30 min at 1-min intervals. The images were converted to binary, and we calculated cell area over time. In all cases, values were normalized with respect to the average, and we defined the SD (percentage with respect to average) as a parameter to describe dynamics of actin polymerization in the lamella.

In all cases, at least three independent cultures were performed, whereby at least three hemocytes were analyzed per culture.

Phagocytic processing and phagocytosis

For phagocytic processing evaluation, culture medium was changed to a solution of Schneider’s medium containing LysoTracker Red DND99 (L7528; Invitrogen) and fluorescently labeled bacteria (E. coli transformed with pE2-Crimson, 632553; Clontech; 4 × 106 CFU/ml). Images were registered at 5- to 10-min intervals. Hemocytes containing at least two acidic vesicles (LysoTracker positive) containing bacteria after 1 h of culture were considered capable of undergoing phagolysosomal degradation.

Lysosomal positioning was determined as the relative position of acidic vesicles (percentage with respect to radius) at time 0 and after 1 h of culture with bacteria. This analysis was performed in a manner similar to the determination of myosin distribution (Fig. S7), with slight variations: Lysosome distribution “before” was calculated with the average image of the first three time points (10 min), before bacteria addition, and “after” was calculated with the average image of the last three time points (last 10 min of exposure to bacteria). The relative coverage of lysosomes within the hemocyte was compared between both time points.

To determine overall phagocytic rate, hemocytes were cultured on 12-mm round coverslips, after which the medium was changed for a solution of Schneider’s medium containing bacteria (E. coli DH5α, 2 × 107 CFU/ml). Hemocytes were cultured at room temperature for 15 min, after which three washes (1 min each) with cold PBS were performed and cells were fixed with PFA 4%. Fixed cells were incubated with Phalloidin-Rhodamine (1:200; R415; Invitrogen) and DAPI (1:10,000; D9542; Sigma). Hemocytes containing bacteria inside were considered phagocytic.

In all cases, at least three independent cultures were performed.

Acridine orange staining

For larval hemocytes, we performed ex vivo cultures of LifeAct-Ruby–expressing hemocytes, as described above. After allowing hemocytes to attach to the glass, we changed culture media to 1 µg/ml acridine orange (A3568; Invitrogen) in PBS, incubating during 5 min at 25°C in a dark chamber. After incubation, we washed the hemocytes several times with PBS and changed culture media to Schneider’s for imaging.

For pupal hemocytes, we dissected the cuticle of 17-h APF pupae (29°C) expressing LifeAct-Ruby in hemocytes. We attached the dorsal side of the pupae to glass-bottomed dishes (P35GC-1.5-10-C; MatTek) previously covered with a heptane-glue solution. We added PBS and cut open the pupae with dissection scissors, after which we removed the intestine, trachea, and most of the remaining fat tissue, taking care not to damage the epithelium. We next changed to PBS containing 1 µg/ml acridine orange and incubated for 5 min at 25°C in a dark chamber. After incubation, we washed several times with PBS and changed culture media to Schneider’s for imaging.

In both cases, at least three independent experiments were performed, and cells were registered at 25°C with optical slices of 0.1 µm in an inverted spinning disk confocal microscope (Zeiss) using a 100× objective (oil immersion, NA 1.4) with an sCMOS camera controlled by Metamorph software. Volume calculation of larval hemocytes and acridine orange vesicles was performed with the ImageJ plugin 3D Objects counter.

Traction force microscopy

This assay relies on the culture of cells over a visible and reversibly deformable substrate. We determined that for hemocytes, the ideal rigidity of the substrate for its visible deformability is 500 Pa. Thus, we prepared 12% polyacrylamide/0.1% bis-acrylamide containing 10% beads (0.2 µm) that fluoresce when excited with 660–680 nm of light (F8807; Thermo Fisher).

Glass-bottomed 35-mm dishes (World Precision Instruments, Inc.) were UV-radiated (2 min) and further treated with APTMS (3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propylamine, 5 min), after which they were thoroughly rinsed and dried before use. Coverslips were treated with SigmaCoat (3 min) followed by several washes with distilled water and were allowed to dry.

The bead-containing polyacrylamide was supplemented with 10% PSA and Temed. This mixture was immediately added on the treated glass-bottomed dishes, and coverslips were placed on top. Dishes were inverted and left in a humidified dark chamber for 1 h. Finally, coverslips were removed, and plates were filled with PBS and left at 4°C until further use.

Hemocyte isolation was performed in Schneider’s medium containing 10% inactivated FBS (S1810-500; Biowest) and 1% antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin; 15140–122; Gibco). Hemocyte-containing solution was transferred to the above-mentioned treated plates. After 15 min, registration began at 30-s intervals. We analyzed bead displacement in the regions where hemocytes localized during the time lapse, as previously described (Martiel et al., 2015). For this, we relied on the ImageJ plugins PIV (Particle Image Velocimetry) and FTTC (Fourier Transform Traction Cytometry) for displacement and force determination, respectively. Finally, we considered only the quadrants occupied by the cell surface to calculate average traction forces.

Hemocyte polarization and subcellular rearrangements

We developed a method that allows pharmacological induction of hemocyte polarization for the study of organellar and cytoskeletal redistribution at high spatiotemporal resolution (Edwards et al., 2018). Briefly, glass-bottomed dishes were treated with collagen type IV (C6745; Sigma) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Hemocytes were cultured on these plates with Schneider’s medium supplemented with 10% inactivated FBS and 1% antibiotics and allowed to settle for 1 h, after which medium was changed to one additionally containing 15 µg/ml of 20-hydroxyecdysone (ab142425; Abcam) to induce polarization. Registration began immediately at 5-min intervals.

Analysis was performed as described (Edwards et al., 2018). First, we used the channel corresponding to the actin cytoskeleton to define a mask for all following analyses (Fig. S8, A and B). We defined cells as polarized when the adjusted ellipse roundness index (from the mask) was <0.9. The center of extended lamella was used as a starting point for the Radial Reslice function, corresponding to 0° = 360° (Fig. S8 C). From this process, we obtained the mean signal intensity with respect to the angle, as well as the local length of the radius (Fig. S8 D). Finally, to compare front and rear, we considered 90° in each orientation, corresponding to 315°–360°, 0°–45° for the front and 135°–225° for the rear (Fig. S8, F and F′).

Figure S8.

Image analysis pipeline for the determination of subcellular distribution in polarized cells. (A) Representative image of a hemocyte expressing LifeAct-GFP stained with LysoTracker probe and treated with 15 µg/ml of 20-hydroxyecdysone to promote polarization. (B) The channel corresponding to actin cytoskeleton was used to obtain a mask for signal intensity measurement. (C) A three-channel image (two original channels + mask) was used to run the Radial Reslice plugin. The white dashed line represents the adjusted circumference around the center of the cell. The first radial signal to be obtained is at the center of the extended lamella (0°) as the program runs, it completes the 360° of the cell clockwise (white round arrow). (D) After the plugin was run, the radial signals of all channels were obtained (360° each). The radial signals from the masks were used to define regions of interest (ROIs) to measure signal intensity of the two original channels. The ROIs were converted to metric units, corresponding to the local length of the cell radius (r). (E) Obtained values were normalized so that in all cases, average signal intensity = 1. Normalized values were plotted to demonstrate graphical distribution of signal in all 360° of the cells. (F) All intensity values from E corresponding to the rear 90° (135°–225°) were compared with the front 90° (315°–360°, 0°–45°). A.U., arbitrary units; Ecd, ecdysone. In this type of analysis, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test were performed (*, P < 0.05). n.s., not significant. (F’) Polarized cell in which the front (F) and rear (R) signals plotted in F are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. The white dashed line represents the adjusted circumference around the center of the cell.

Image processing and statistical analysis

All images were processed and analyzed with the free access ImageJ/Fiji software. Figures were elaborated with Adobe Photoshop CS6, except the final model, which was built in Adobe Illustrator CC 2019. All plots and statistical analysis were performed with GraphPad Prism 7 software.

In all cases, at least three independent experiments were performed. The exact number of replica and statistical analyses is detailed in all figure legends. In all cases, we performed a D’Agostino-Pearson normality test. These results were used to define if normality could be assumed or not in unpaired Student’s t test for single-parameter experiments and one-way or two-way ANOVA (with Tukey’s or Sidak’s post hoc test) for multiparameter experiments. Statistically significant differences were drawn at P value < 0.05.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows trpml1 genetic complementation and rescue in phagocytic processing as well as overall phagocytic rates. Fig. S2 reveals the accumulation of engulfed apoptotic bodies in larval and pupal hemocytes. Fig. S3 shows lysosomal displacement during phagosome maturation. Fig. S4 shows trpml1 genetic complementation and rescue in actomyosin dynamics. Fig. S5 demonstrates that fab1 knockdown phenocopies trpml deficiencies. Fig. S6 shows the effect of chloroquine and thapsigargin treatment on hemocytes. Fig. S7 is the pipeline for the analysis of actomyosin (or lysosomal) distribution. Fig. S8 is the pipeline for the analysis of subcellular distribution in polarized cells. Video 1 shows pupal hemocytes migrating in vivo (control, trpml1, vamp7 RNAi, and trpml rescue). Video 2 shows actin dynamics of larval hemocytes cultured ex vivo (control, trpml1, and sqh RNAi) in control media or supplemented with MLSA1. Video 3 reveals Trpml-GCaMP5 reporter’s activity in response to the addition of MLSA1. Video 4 shows actin dynamics of fab1-deficient larval hemocytes cultured ex vivo in control media or supplemented with MLSA1. Video 5 shows Sqh dynamics of cultured larval hemocytes (control, control + MLSA1, vamp7 RNAi, vamp7 RNAi + trpml RNAi, trpml1, trpml RNAi, Mypt75DF117A, and Mypt75DF117A + trpml RNAi). Video 6 shows traction force microscopy videos of control and trpml1 hemocytes cultured on a deformable substrate covered with fluorescently labeled beads. Video 7 shows actin dynamics of control and trpml1 larval hemocytes cultured ex vivo in media supplemented with chloroquine or thapsigargin. Video 8 reveals cytosolic Ca2+ release in response to thapsigargin (GCaMP6 reporter). Video 9 shows the activity of Trpml in pupal hemocytes migrating in vivo (Trpml-GCaMP5.T + LifeActRuby‒expressing clones).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kartik Venkatachalam (The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX) for kindly sending us Trpml activity reporter UAS-Trpml.GCaMP5.T, used in Wong et al. (2017), as well as Dr. Will Wood (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK) for sending us the stock Ubi::Cad.GFP, Srp>Gal4, UAS-GFP/CyO; Crq>Gal4, UAS-RedStinger (Weavers et al., 2016), allowing us to perform directed migration experiments in response to epithelial damage. We also thank Andrea Gonzalez for helping with the final model, and we thank the Developmental Biology Curie imaging facility PICT-IBiSA@BDD.

This article was supported by Chilean grants Fondap 15090007, Conicyt Act 1401, Conicyt PCI REDES 14004, Conicyt fellowship 140289, and French funding Labex DCBIOL.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions:S.S. Edwards-Jorquera, first author: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, project administration, and writing (original draft); F. Bosveld: investigation;Y. Bellaïche: resources, writing (review and editing);A.M. Lennon-Duménil: supervision, conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, and writing (review and editing);andÁ. Glavic: supervision, conceptualization, project administration, resources, funding acquisition, and writing (review and editing).

References

- Banerjee U., Girard J.R., Goins L.M., and Spratford C.M.. 2019. Drosophila as a Genetic Model for Hematopoiesis. Genetics. 211:367–417. 10.1534/genetics.118.300223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi M.T., Manzoni M., Monti E., Pizzo M.T., Ballabio A., and Borsani G.. 2000. Cloning of the gene encoding a novel integral membrane protein, mucolipidin-and identification of the two major founder mutations causing mucolipidosis type IV. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67:1110–1120. 10.1016/S0002-9297(07)62941-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg R.D., Levitte S., O’Sullivan M.P., O’Leary S.M., Cambier C.J., Cameron J., Takaki K.K., Moens C.B., Tobin D.M., Keane J., et al. . 2016. Lysosomal Disorders Drive Susceptibility to Tuberculosis by Compromising Macrophage Migration. Cell. 165:139–152. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergert M., Erzberger A., Desai R.A., Aspalter I.M., Oates A.C., Charras G., Salbreux G., and Paluch E.K.. 2015. Force transmission during adhesion-independent migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 17:524–529. 10.1038/ncb3134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Fraisier V., Raposo G., Hurbain I., Sibarita J.-B., Chavrier P., Galli T., and Niedergang F.. 2004. TI-VAMP/VAMP7 is required for optimal phagocytosis of opsonised particles in macrophages. EMBO J. 23:4166–4176. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretou M., Sáez P.J., Sanséau D., Maurin M., Lankar D., Chabaud M., Spampanato C., Malbec O., Barbier L., Muallem S., et al. . 2017. Lysosome signaling controls the migration of dendritic cells. Sci. Immunol. 2:eaak9573. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Browne N., Heelan M., and Kavanagh K.. 2013. An analysis of the structural and functional similarities of insect hemocytes and mammalian phagocytes. Virulence. 4:597–603. 10.4161/viru.25906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero D., Voituriez R., and Riveline D.. 2014. Protrusion fluctuations direct cell motion. Biophys. J. 107:34–42. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]