Abstract

A novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has been identified as the causative pathogen of an ongoing outbreak of respiratory disease, now named COVID-19. Most cases and sustained transmission occurred in China, but travel-associated cases have been reported in other countries, including Europe and Italy. Since the symptoms are similar to other respiratory infections, differential diagnosis in travellers arriving from countries with wide-spread COVID-19 must include other more common infections such as influenza and other respiratory tract diseases.

Key words: differential diagnosis, SARS-CoV-2, respiratory pathogens, rapid molecular assay

Following the first reports of cases of acute respiratory syndrome of unknown aetiology in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, on 31 December 2019 [1], Chinese authorities have identified a novel coronavirus, now named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), as the causative agent [2,3]. The outbreak has spread rapidly, affecting other parts of China, and cases have been recorded on several continents (Asia, Australia, Europe and North America); further global spread is likely to occur [4].

The spectrum of this disease in humans, now named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [5], is yet to be fully determined. For confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections, reported illnesses have ranged from people with little to no symptoms to people being severely ill, having pneumonia and dying [6]. Multiple body tracts may be involved, including the respiratory, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal and neurologic tracts. However, more common symptoms are fever (83–98%), cough (76–82%) and shortness of breath (31–55%) [6,7]. These nonspecific symptoms are shared by many other frequent infectious diseases of the respiratory tract caused by bacteria and viruses, most of which are self-limiting but may also progress to severe conditions [8,9]. Among these, the most relevant is influenza, usually characterised by fever, myalgia, headache and non-productive cough, that may also cause complications with high morbidity and mortality rate, such as pneumonia, myocarditis, central nervous system disease and death [10,11]. In addition, other previously known human coronaviruses cause similar, although milder clinical signs, including the alphacoronaviruses 229E and NL63, and the betacoronaviruses OC43 and HKU1, while two other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, cause severe respiratory syndrome in humans [12].

The Laboratory of Virology at the National Institute for Infectious Diseases ‘Lazzaro Spallanzani’ (INMI) in Rome is the Regional Reference Centre for emerging infections and performs also diagnostics for other Italian regions without the diagnostic capability for emerging pathogens. Early in January 2020, following the announcement of the emerging outbreak, the Laboratory established the diagnostic capability for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and provided support to other Italian regions.

Here we focus on the results of the differential diagnosis performed on the first 126 suspected cases, analysed in the reference laboratory from 21 January to 7 February 2020.

Diagnostic algorithm

The diagnostic algorithm adopted by the Laboratory for SARS-CoV-2 testing included, immediately upon sample receipt, a rapid molecular test for the most common respiratory pathogens in order to obtain a fast differential diagnosis. SARS-CoV-2 testing was based on the protocol released by the World Health Organization (WHO) [13], and three positive patients have been identified at the time of writing this paper.

The 126 patients were considered suspected cases on the basis of information collected on clinical and epidemiological grounds, i.e. suspicion of a viral aetiology, recent travel history to Asia, or contact with a probable or confirmed case, according to WHO guidelines [14]. They included 64 male and 62 female cases, 52 were Italian citizens, 64 Chinese and six had other nationalities. The mean age was 35 years (range: 1–85 years).

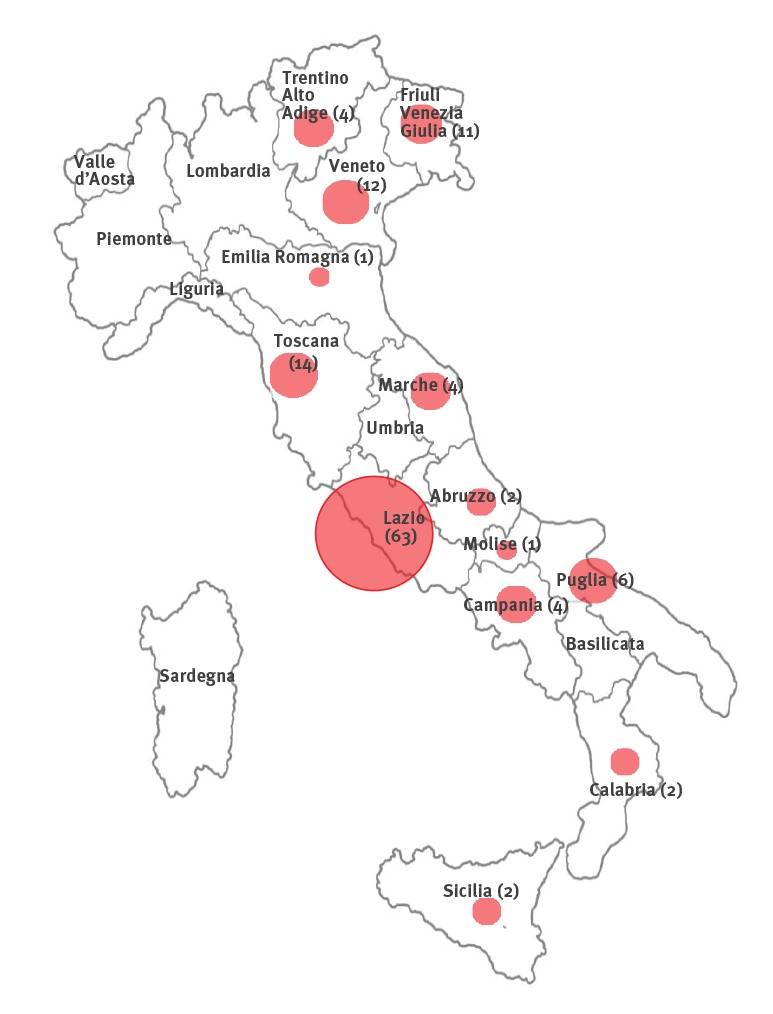

Nasopharyngeal swab specimens were collected from 54 patients hospitalised in the high isolation facility at the INMI in Rome, nine patients from other hospitals in the Lazio Region and a further 63 cases referred to the INMI Laboratory of Virology from different regions of Italy (Figure).

Figure.

Origin (region) and number of patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection, Rome, Italy, 21 January–7 February 2020, (n = 126)

SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Samples from suspected cases tested at the Laboratory of Virology of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases ‘Lazzaro Spallanzani’. The dimension of round symbols correlates with the number of patients analysed.

Molecular assays for respiratory pathogens

Rapid differential diagnosis was based on the QIAstat-Dx respiratory panel (QIAGEN, Milan, Italy); this system uses a single-use cartridge that includes all reagents needed for nucleic acid extraction, amplification and detection of the most common bacteria and viruses causing respiratory syndromes: adenovirus, bocavirus, coronavirus 229E (HCoV 229E), coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV HKU1), coronavirus NL63 (HCoV NL63), coronavirus OC43 (HCoV OC43), human metapneumovirus (HMPV), influenza A, influenza A subtype H1N1/pdm09 influenza A subtypes H1 and H3, influenza B, parainfluenza virus 1–2-3–4 (PIV 1–4), respiratory syncytial virus A/B (RSV A/B), rhinovirus/enterovirus, (HRV/EV), Bordetella pertussis, Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Results were available 70–90 min after sample receipt. The results considered in the analysis include those from 109 suspected cases undergoing rapid molecular testing at the Reference Laboratory, and those from 17 patients tested at the laboratory of origin (either with the rapid respiratory panel or with other methods).

Among the first 126 patients evaluated at the reference Laboratory at INMI, only three were confirmed to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and none of those three was co-infected with other pathogens (Table).

Table. Viral and bacterial agents detected in patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection, Rome, Italy, 21 January–7 February 2020, (n = 126).

| Pathogens | Patients with pathogen detected | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Infections with a single pathogen | ||

| None | 56 | 44.4 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 3 | 2.4 |

| Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 | 12 | 9.5 |

| Influenza A(H3N2) | 11 | 8.7 |

| Influenza Aa | 3 | 2.4 |

| Influenza B | 10 | 7.9 |

| HRV/EV | 9 | 7.1 |

| HMPV | 3 | 2.4 |

| H-CoV 229 E | 2 | 1.6 |

| H-CoV NL63 | 2 | 1.6 |

| H-CoV HKU1 | 2 | 1.6 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 5 | 4.0 |

| Legionella pneumophila | 1 | 0.8 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1b | 0.8 |

| Mixed infections | ||

| Influenza A(H3N2) + RSV A/B | 2 | 1.6 |

| HRV/EV + RSV A/B | 1 | 0.8 |

| HRV/EV + influenza B | 1 | 0.8 |

| HMPV + adenovirus | 1 | 0.8 |

| H-CoV 229E + influenza B | 1 | 0.8 |

EV: enterovirus; HMPV: human metapneumovirus; HRV: rhinovirus; SARS-CoV: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

a Untyped influenza A because of low viral load.

b S. pneumoniae was referred by the laboratory of origin.

Overall, 67 (53.2%) of the patients resulted positive for respiratory pathogen(s) other than SARS-CoV-2. Influenza viruses represented the majority of positive findings, influenza A accounting for 26 (20.6%) and influenza B accounting for 10 (7.9%) of all single infections. Other viruses were represented as well (Table). As far as bacterial infections are concerned, M. pneumoniae was detected in five patients (4.0%), while L. pneumophila and Streptococcus pneumoniae (the positive result for S. pneumoniae was referred by the laboratory origin), were found only in one patient (0.8%). Mixed infections were also observed in a small number of cases (Table).

Discussion

Our results highlight the importance of differential diagnosis in travellers arriving from countries with widespread occurrence of COVID-19, considering the similarity of symptoms shared with more common respiratory infections, such as influenza and other respiratory tract diseases.

Broad screening for respiratory pathogens revealed a high rate of influenza virus infections, accounting for 28.5% of all suspected cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection; this is consistent with the fact that we are the middle of the seasonal influenza epidemic period. Notably, rapid influenza diagnosis facilitates timely administration of antiviral therapy, thus reducing severity and length of the disease and use of unnecessary antibiotics.

Our results highlight the importance of using a broad-spectrum molecular diagnostic panel for rapid detection of the most common respiratory pathogens, in order to improve evaluation and clinical management of patients with respiratory syndrome consistent with COVID-19. This is important in an epidemiological situation with low circulation of SARS-CoV-2, where alternative diagnoses may clarify an individual patient’s risk and may allow adjusting public health containment measures. Nevertheless, it is mandatory to maintain high level of attention with respect to this new emergent pathogen and health authorities should remain vigilant, increasing their capacity for surveillance and constantly reviewing their pandemic preparedness plans.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge:

Collaborators Members of INMI COVID-19 study group: Maria Alessandra Abbonizio, Chiara Agrati, Fabrizio Albarello, Gioia Amadei, Alessandra Amendola, Mario Antonini, Raffaella Barbaro, Barbara Bartolini, Martina Benigni, Nazario Bevilacqua, Licia Bordi, Veronica Bordoni, Marta Branca, Paolo Campioni, Maria Rosaria Capobianchi, Cinzia Caporale, Ilaria Caravella, Fabrizio Carletti, Concetta Castilletti, Roberta Chiappini, Carmine Ciaralli, Francesca Colavita, Angela Corpolongo, Massimo Cristofaro, Salvatore Curiale, Alessandra D’Abramo, Cristina Dantimi, Alessia De Angelis, Giada De Angelis, Rachele Di Lorenzo, Federica Di Stefano, Federica Ferraro, Lorena Fiorentini, Andrea Frustaci, Paola Gallì, Gabriele Garotto, Maria Letizia Giancola, Filippo Giansante, Emanuela Giombini, Maria Cristina Greci, Giuseppe Ippolito, Eleonora Lalle, Simone Lanini, Daniele Lapa, Luciana Lepore, Andrea Lucia, Franco Lufrani, Manuela Macchione, Alessandra Marani, Luisa Marchioni, Andrea Mariano, Maria Cristina Marini, Micaela Maritti, Giulia Matusali, Silvia Meschi, Francesco Messina, Chiara Montaldo, Silvia Murachelli, Emanuele Nicastri, Roberto Noto, Claudia Palazzolo, Emanuele Pallini, Virgilio Passeri, Federico Pelliccioni, Antonella Petrecchia, Ada Petrone, Nicola Petrosillo, Elisa Pianura, Maria Pisciotta, Silvia Pittalis, Costanza Proietti, Vincenzo Puro, Gabriele Rinonapoli, Martina Rueca, Alessandra Sacchi, Francesco Sanasi, Carmen Santagata, Silvana Scarcia, Vincenzo Schininà, Paola Scognamiglio, Laura Scorzolini, Giulia Stazi, Francesco Vaia, Francesco Vairo, Maria Beatrice Valli.

Collaborating Centers: Alessandro Chiodera, Infectious Diseases - ASUR Marche, AV3 Hospital Macerata; Cesira Nencioni: Infectious Diseases –USL Toscana Sud-Est, Grosseto; Claudio Fabbri: Infectious Diseases 2, San Jacopo Hospital, USL Toscana-Centro, Pistoia-Prato; Nicola Maturo: Infectious Disease Emergency AO dei Colli- Napoli; Michele Brogna: Infectious Dieseases, Vibo Valentia Hospital; Donatella Giacomazzi: Infectious Diseases, Trieste Hospital; Bottone Gabriella: Pediatrics San SalvatoreHospital, L'Aquila; Mauro Pistello: Regional Reference Center of Virologic and Innovative Diagnostic, Cisanello hospital, Pisa; Antonella Vincenti: Infectious Disease, Apuane hospital, ASL1Massa; Annalisa Saracino: Department of Biomedical Sciences and Human Oncology, University of Bari; Massimo Crapis: Infectious Diseases and Intensive Care, Pordenone and San Vito al Tagliamento Hospitals, Friuli Occidentale, Pordenone; Elke Maria Erne: Infectious Diseases, Bolzano Hospital, Alto Adige; Carlo Tascini: Clinical Infectious Diseases, Friuli Centrale, Udine; Lucia Collini: Virology and Molecular Biology, Autonomous Province of Trento; Ciofi Degli Atti Marta Luisa: Clinical Route and Epidemiology Unit, Pediatric Hospital Bambin Gesu, Roma; Fabio Tramuto: Clinical Epidemiology, Policlinico ‘Paolo Giaccone’ Palermo; Letizia Attala: infectious Diseases 1, Usl Toscana Centro, Santa Bagno a Ripoli Hospital, Firenze; Lucia Moro: IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar, Verona; Piergiorgio Scotton: Infectious Diseases of Treviso Hospital; Ferraro Maria Cristina: Intensive Care Department, Careggi FIrenze; Alessandra Prozzo: Infectious Diseases, Carderelli Hospital Campobasso; Camilla Aiassa, Infectious Diseases, Policlinico Umberto I, Roma.

Funding: This research was supported by funds to National Institute for Infectious Diseases ‘Lazzaro Spallanzani’ IRCCS from: Ministero della Salute, Ricerca Corrente, linea1.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Authors’ contributions: LB: designed the study, performed laboratory testing, analysed data, wrote manuscript. EN, LS. ADC: discussed results. CC, EL: performed laboratory testing, assisted in designing the study, read and revised manuscript. MRC: designed the study and read and revised manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Pneumonia of unknown cause-China. Geneva: WHO; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). Novel Coronavirus - China. Geneva: WHO; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/

- 3.Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS, de Groot RJ, Drosten C, Gulyaeva AA, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: The species and its viruses – a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. bioRxiv 2020.02.07.937862; https://doi.org/ 10.1101/2020.02.07.937862 [DOI]

- 4.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). COVID-19. Situation update worldwide. Stockholm: ECDC. [Accessed: 5 Feb 2020]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General's remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. Geneva: WHO; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Atlanta: CDC; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/symptoms.html

- 7. Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan YJ. Overview of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): The pathogen of severe specific contagious pneumonia (SSCP). J Chin Med Assoc. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000270 32049687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Follin P, Lindqvist A, Nyström K, Lindh M. A variety of respiratory viruses found in symptomatic travellers returning from countries with ongoing spread of the new influenza A(H1N1)v virus strain. Euro Surveill. 2009;14(24):19242. 10.2807/ese.14.24.19242-en [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Puro V, Minosse C, Cappiello G, Lauria FN, Capobianchi MR. Rhinovirus and lower respiratory tract infection in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(7):1068-9. 10.1086/428359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, Szilagyi P, Staat MA, Iwane MK, et al. The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):31-40. 10.1056/NEJMoa054869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza --- United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(33):1057-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181-92. 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, Molenkamp R, Meijer A, Chu DKW, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3):2000045. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO). Global Surveillance for human infection with coronavirus disease (COVID-2019). Geneva: WHO; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/global-surveillance-for-human-infection-with-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)