Abstract

Background

Emergency contraception (EC) is using a drug or copper intrauterine device (Cu‐IUD) to prevent pregnancy shortly after unprotected intercourse. Several interventions are available for EC. Information on the comparative effectiveness, safety and convenience of these methods is crucial for reproductive healthcare providers and the women they serve. This is an update of a review previously published in 2009 and 2012.

Objectives

To determine which EC method following unprotected intercourse is the most effective, safe and convenient to prevent pregnancy.

Search methods

In February 2017 we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Popline and PubMed, The Chinese biomedical databases and UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme on Human Reproduction (HRP) emergency contraception database. We also searched ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov as well as contacting content experts and pharmaceutical companies, and searching reference lists of appropriate papers.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials including women attending services for EC following a single act of unprotected intercourse were eligible.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane. The primary review outcome was observed number of pregnancies. Side effects and changes of menses were secondary outcomes.

Main results

We included 115 trials with 60,479 women in this review. The quality of the evidence for the primary outcome ranged from moderate to high, and for other outcomes ranged from very low to high. The main limitations were risk of bias (associated with poor reporting of methods), imprecision and inconsistency.

Comparative effectiveness of different emergency contraceptive pills (ECP)

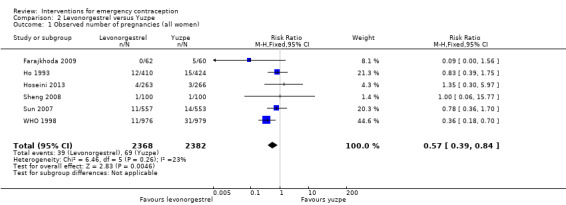

Levonorgestrel was associated with fewer pregnancies than Yuzpe (estradiol‐levonorgestrel combination) (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.84, 6 RCTs, n = 4750, I2 = 23%, high‐quality evidence). This suggests that if the chance of pregnancy using Yuzpe is assumed to be 29 women per 1000, the chance of pregnancy using levonorgestrel would be between 11 and 24 women per 1000.

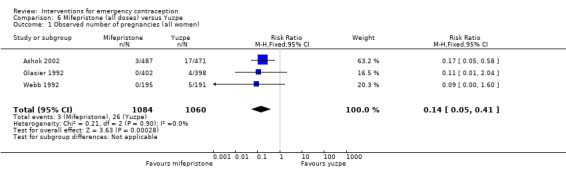

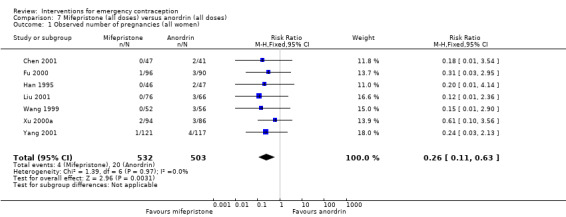

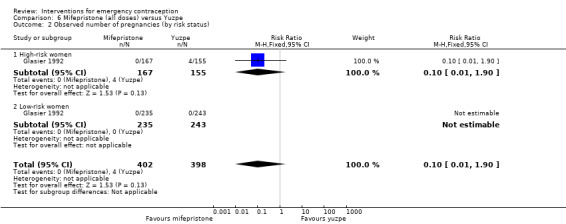

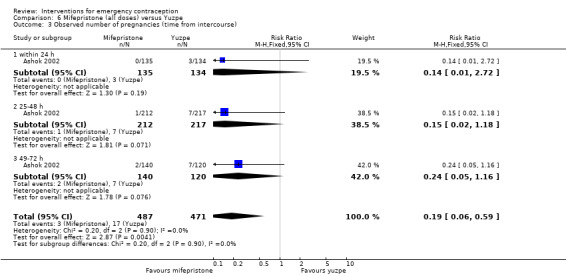

Mifepristone (all doses) was associated with fewer pregnancies than Yuzpe (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.41, 3 RCTs, n = 2144, I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence). This suggests that if the chance of pregnancy following Yuzpe is assumed to be 25 women per 1000 women, the chance following mifepristone would be between 1 and 10 women per 1000.

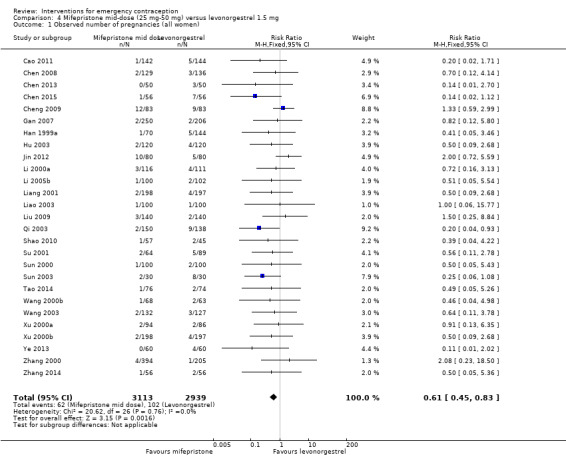

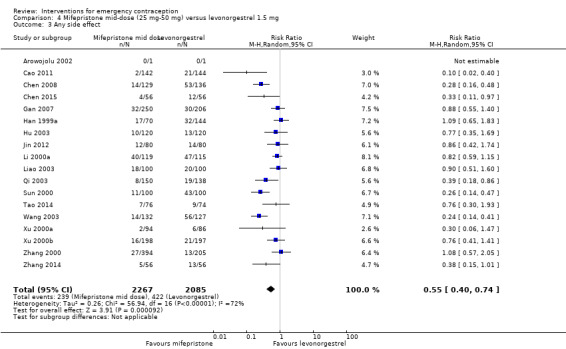

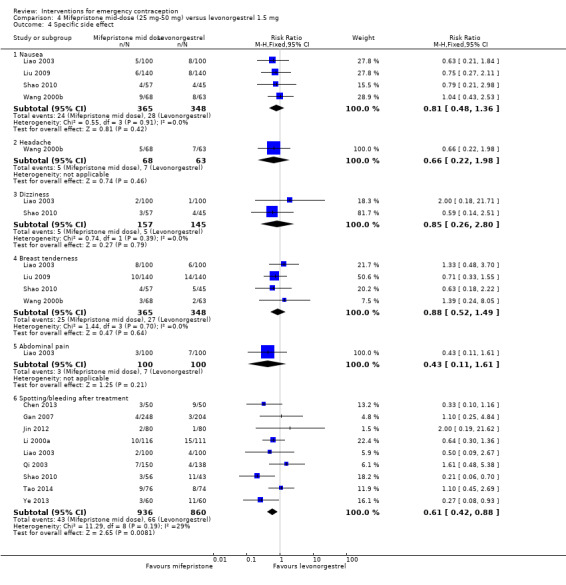

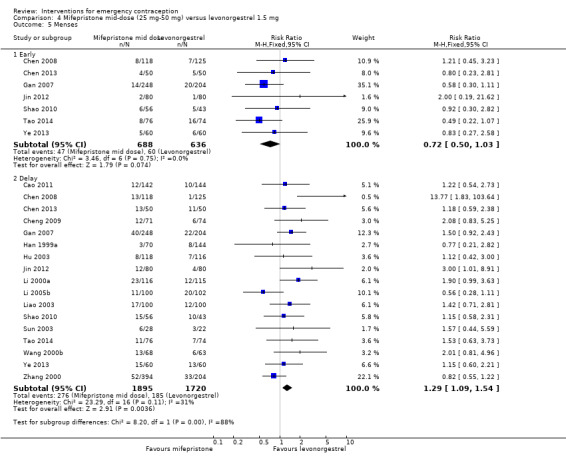

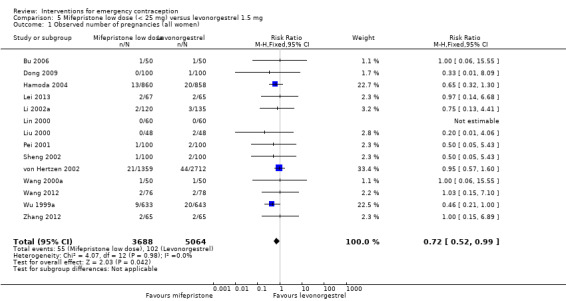

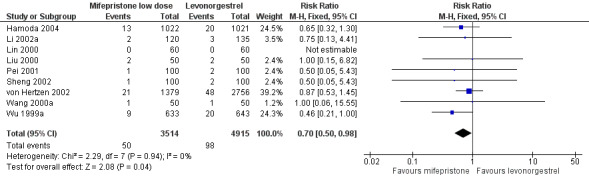

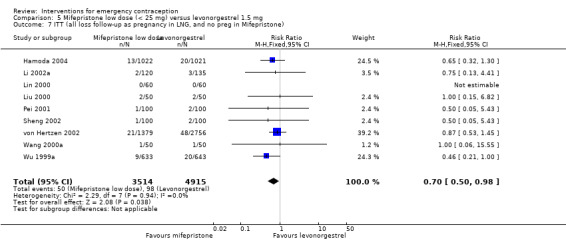

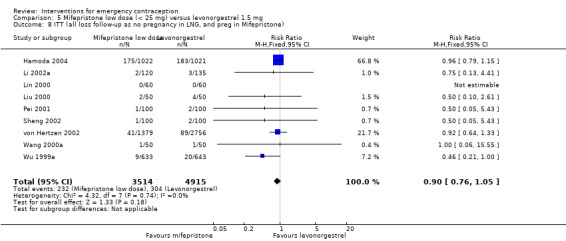

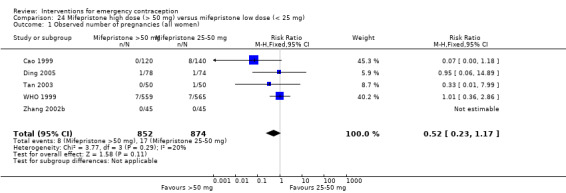

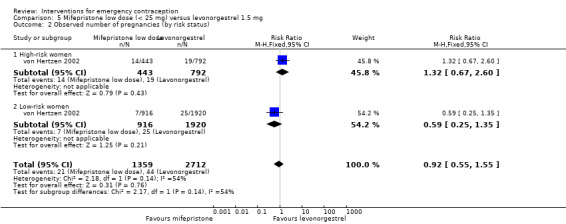

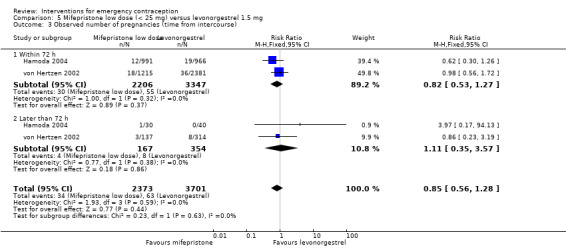

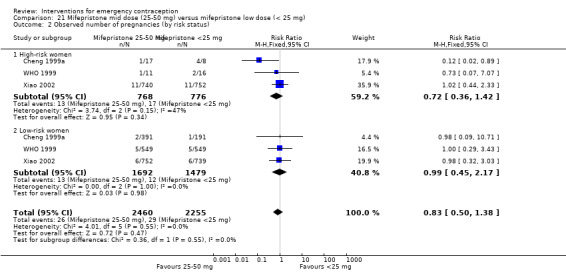

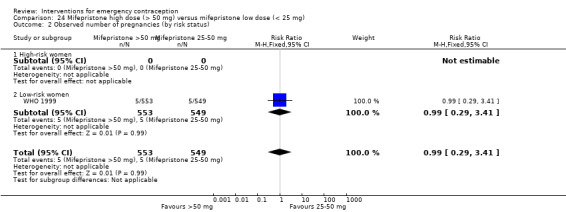

Both low‐dose mifepristone (less than 25 mg) and mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg to 50 mg) were probably associated with fewer pregnancies than levonorgestrel (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.99, 14 RCTs, n = 8752, I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence; RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.83, 27 RCTs, n = 6052, I2 = 0%, moderate‐quality evidence; respectively). This suggests that if the chance of pregnancy following levonorgestrel is assumed to be 20 women per 1000, the chance of pregnancy following low‐dose mifepristone would be between 10 and 20 women per 1000; and that if the chance of pregnancy following levonorgestrel is assumed to be 35 women per 1000, the chance of pregnancy following mid‐dose mifepristone would be between 16 and 29 women per 1000.

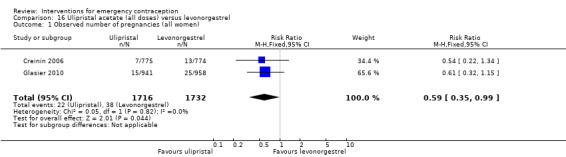

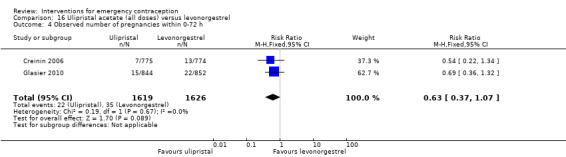

Ulipristal acetate (UPA) was associated with fewer pregnancies than levonorgestrel (RR 0.59; 95% CI 0.35 to 0.99, 2 RCTs, n = 3448, I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence).

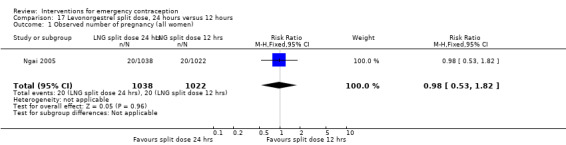

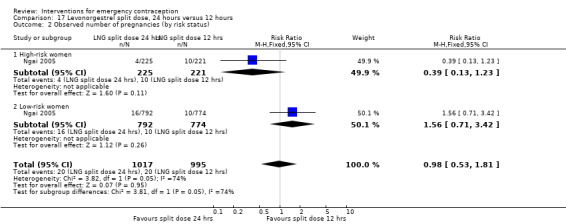

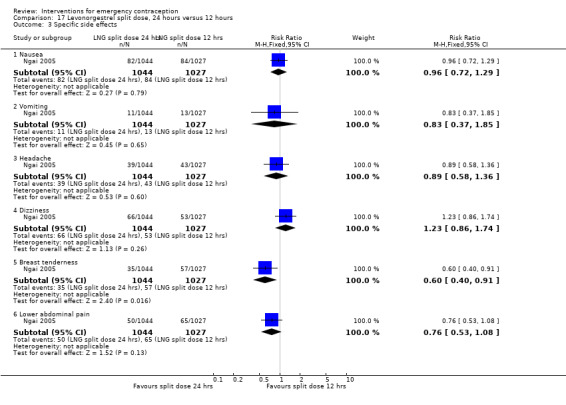

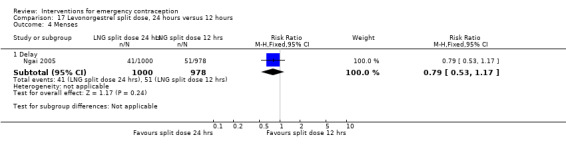

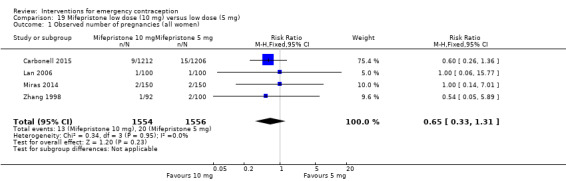

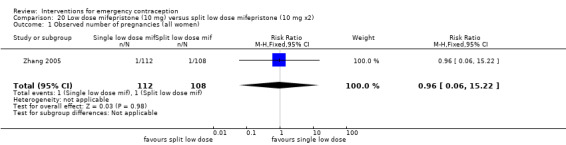

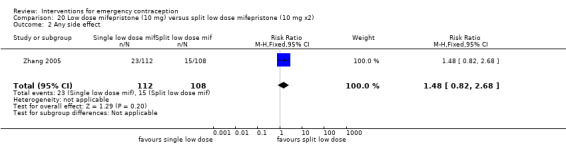

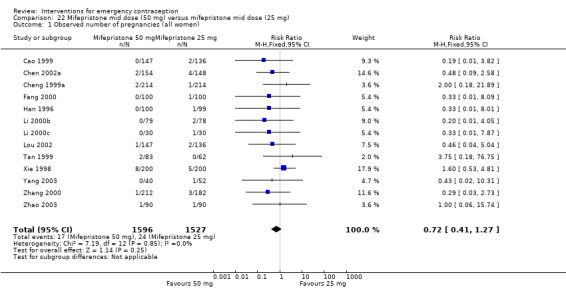

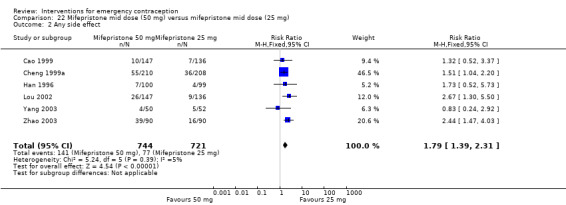

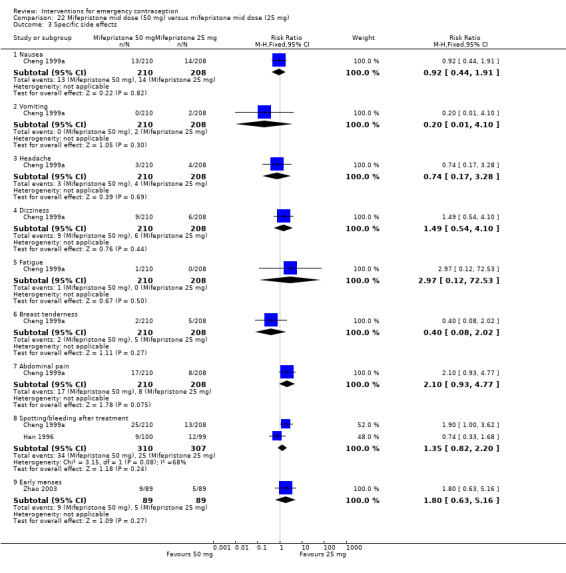

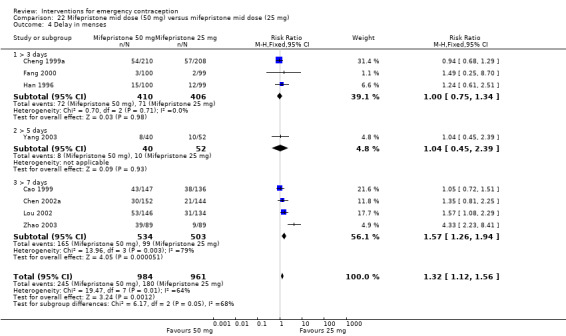

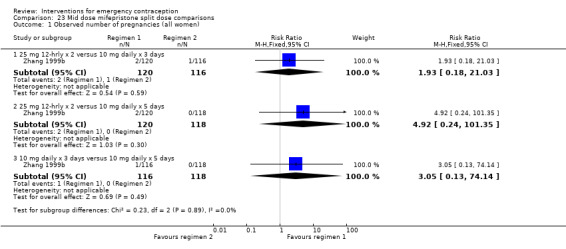

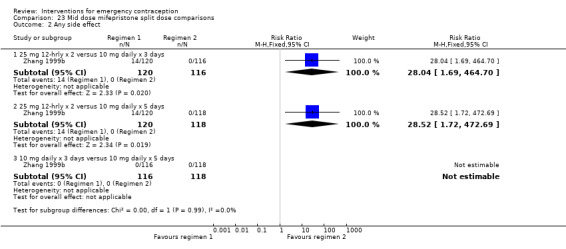

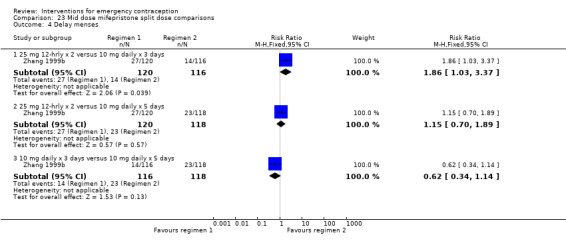

Comparative effectiveness of different ECP doses

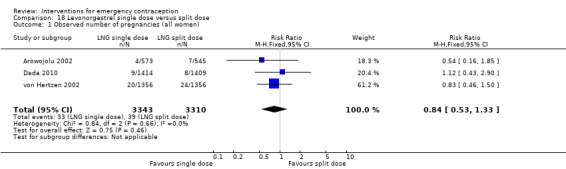

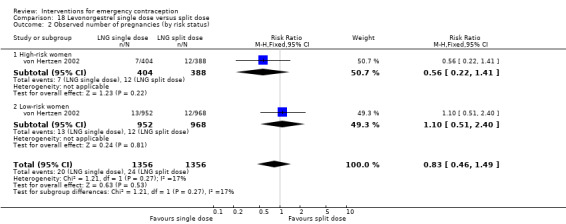

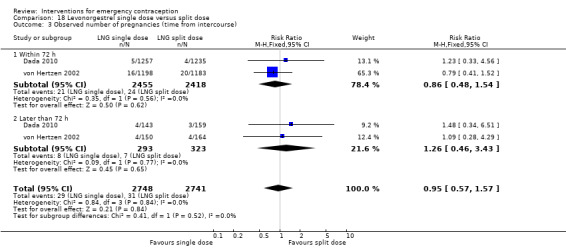

It was unclear whether there was any difference in pregnancy rate between single‐dose levonorgestrel (1.5 mg) and the standard two‐dose regimen (0.75 mg 12 hours apart) (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.33, 3 RCTs, n = 6653, I2 = 0%, moderate‐quality evidence).

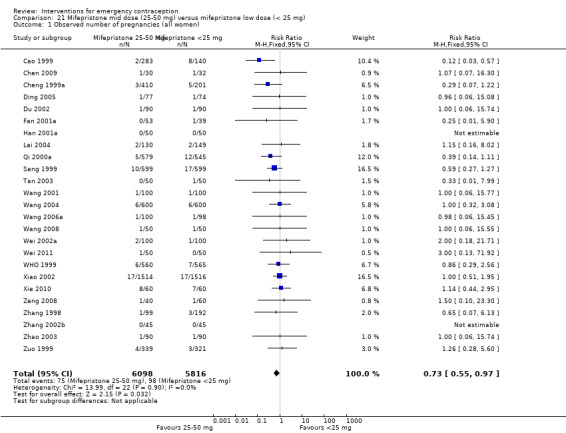

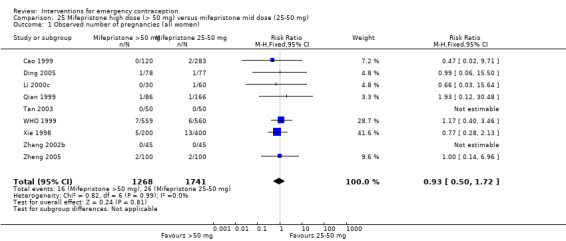

Mid‐dose mifepristone was associated with fewer pregnancies than low‐dose mifepristone (RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.97, 25 RCTs, n = 11,914, I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence).

Comparative effectiveness of Cu‐IUD versus mifepristone

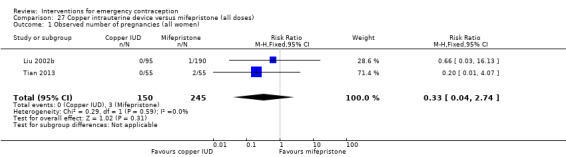

There was no conclusive evidence of a difference in the risk of pregnancy between the Cu‐IUD and mifepristone (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.04 to 2.74, 2 RCTs, n = 395, low‐quality evidence).

Adverse effects

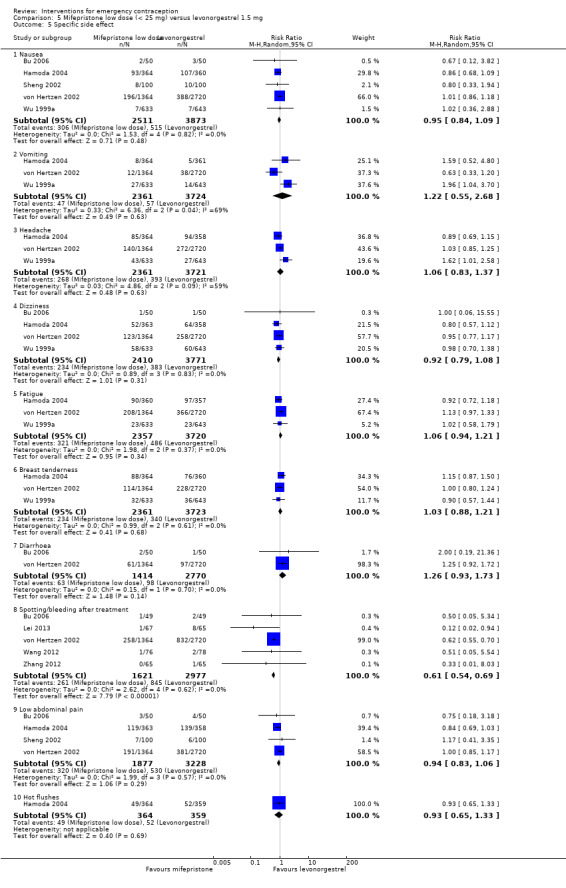

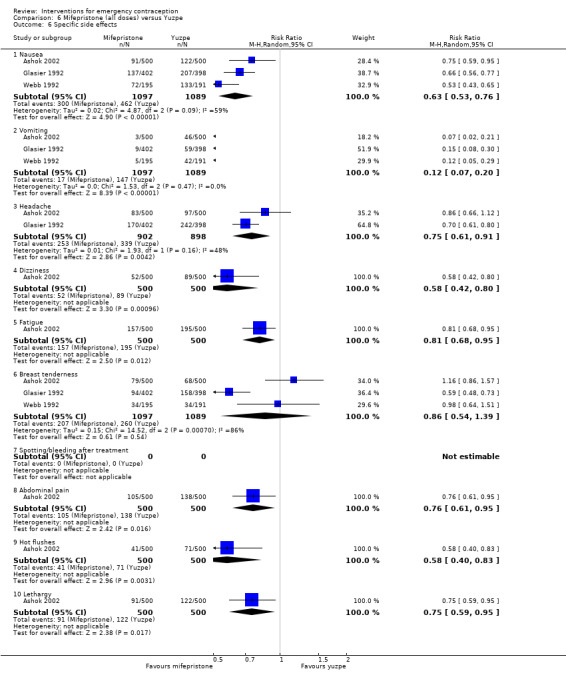

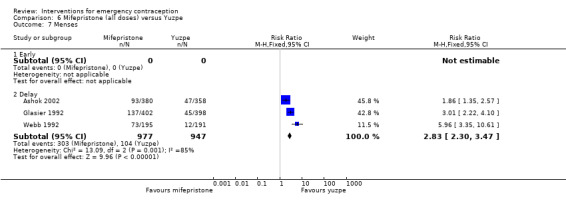

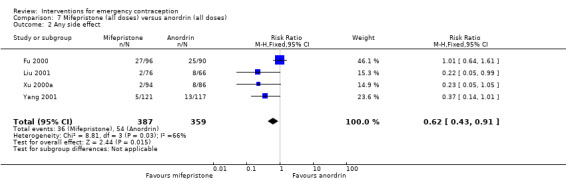

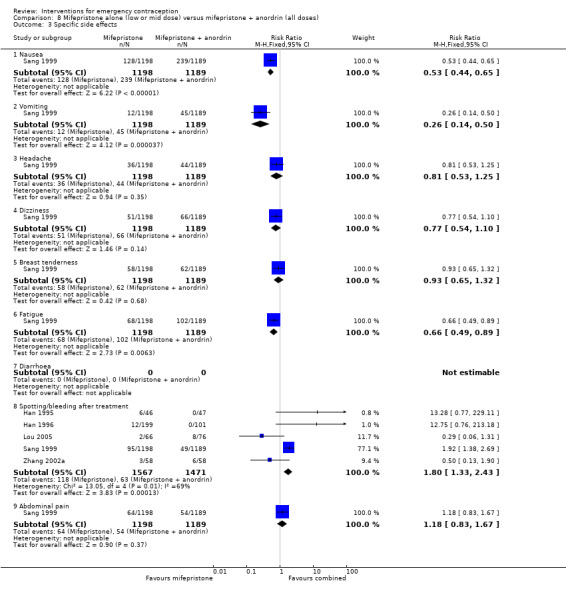

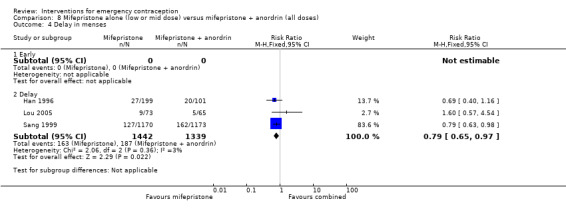

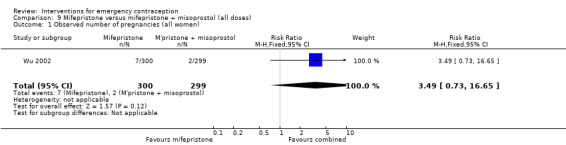

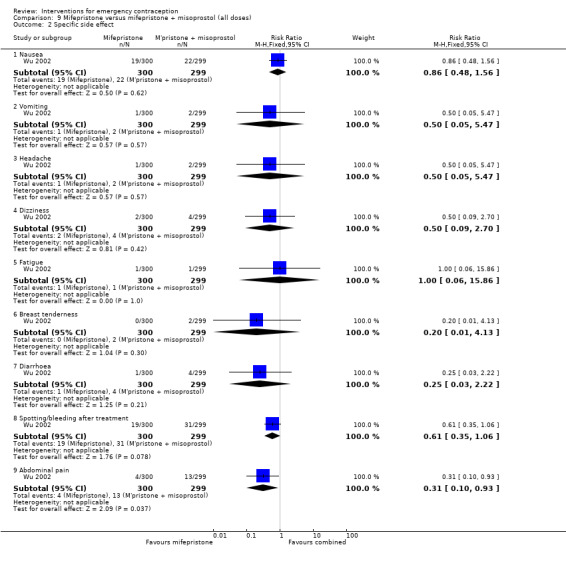

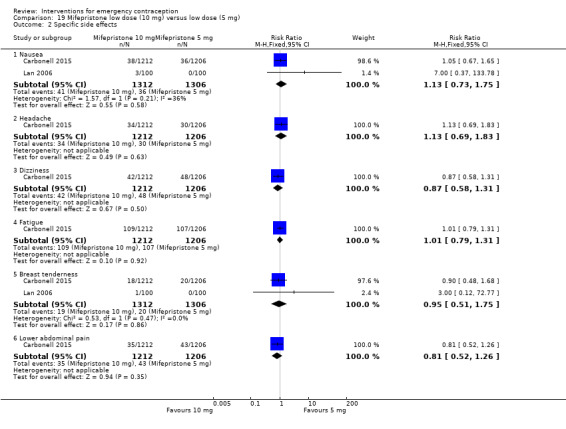

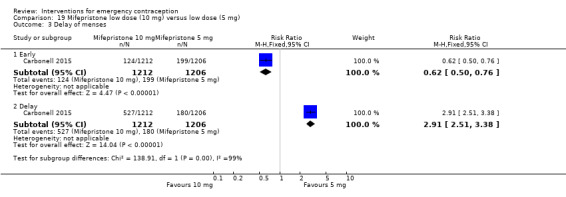

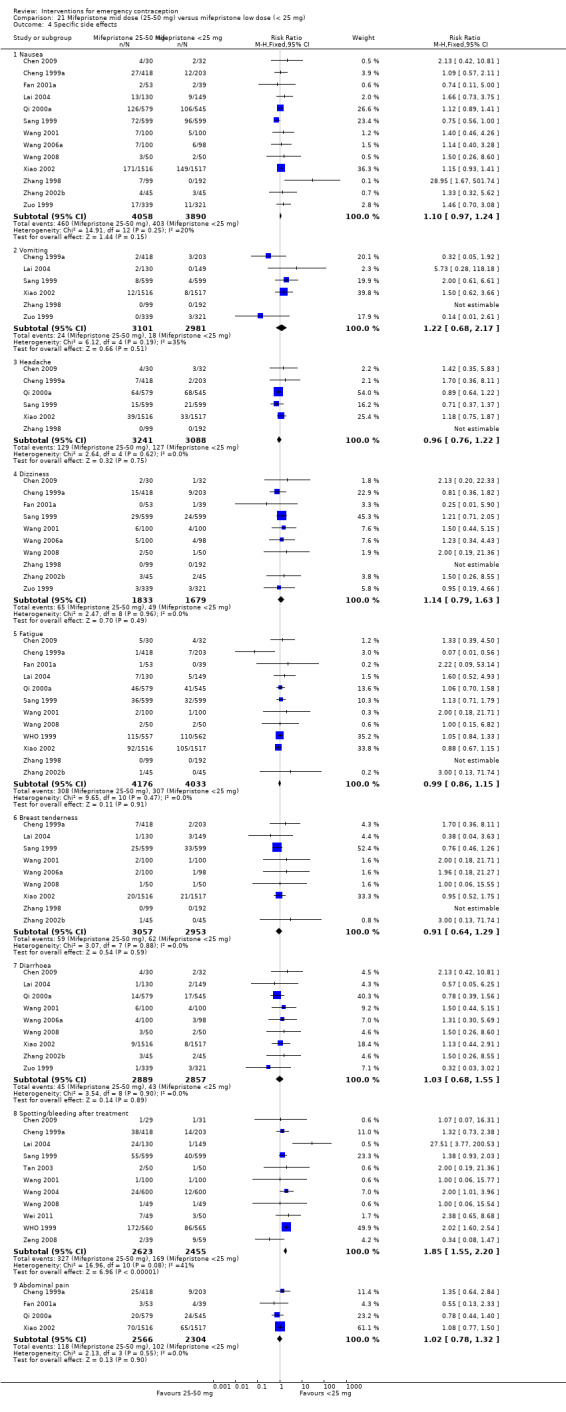

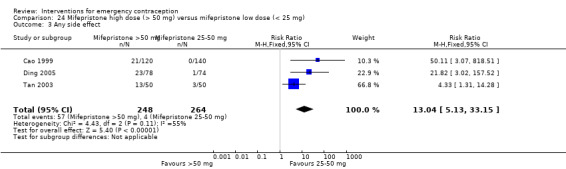

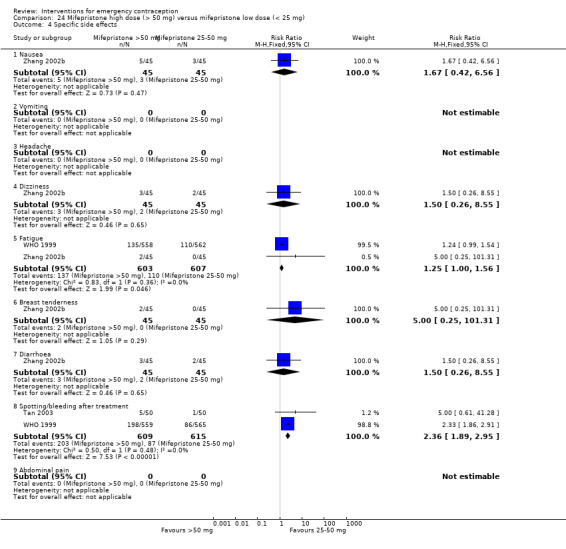

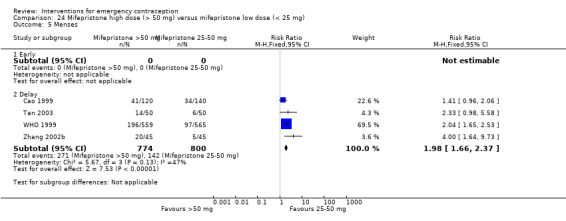

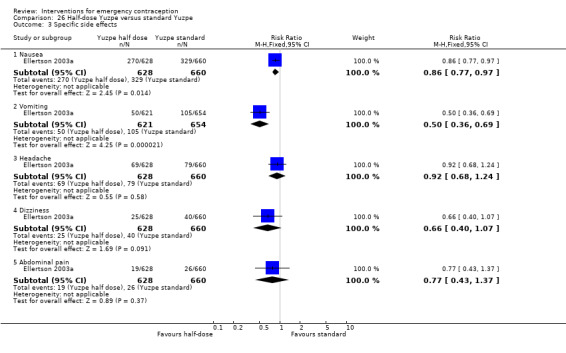

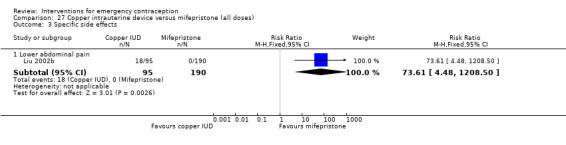

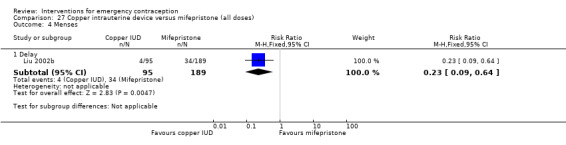

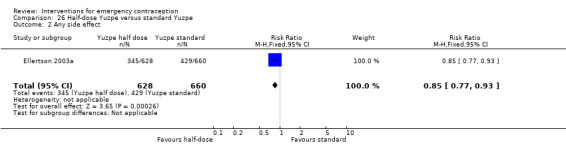

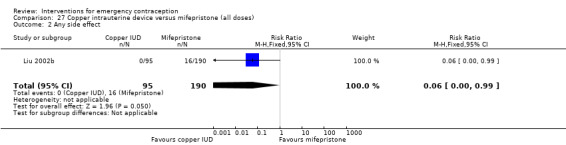

Nausea and vomiting were the main adverse effects associated with emergency contraception. There is probably a lower risk of nausea (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.76, 3 RCTs, n = 2186 , I2 = 59%, moderate‐quality evidence) or vomiting (RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.20, 3 RCTs, n = 2186, I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence) associated with mifepristone than with Yuzpe. levonorgestrel is probably associated with a lower risk of nausea (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.44, 6 RCTs, n = 4750, I2 = 82%, moderate‐quality evidence), or vomiting (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.35, 5 RCTs, n = 3640, I2 = 78%, moderate‐quality evidence) than Yuzpe. Levonorgestrel users were less likely to have any side effects than Yuzpe users (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.86; 1 RCT, n = 1955, high‐quality evidence). UPA users were more likely than levonorgestrel users to have resumption of menstruation after the expected date (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.42 to 1.92, 2 RCTs, n = 3593, I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence). Menstrual delay was more common with mifepristone than with any other intervention and appeared to be dose‐related. Cu‐IUD may be associated with higher risks of abdominal pain than mifepristone (18 events in 95 women using Cu‐IUD versus no events in 190 women using mifepristone, low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Levonorgestrel and mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg to 50 mg) were more effective than Yuzpe regimen. Both mid‐dose (25 mg to 50 mg) and low‐dose mifepristone(less than 25 mg) were probably more effective than levonorgestrel (1.5 mg). Mifepristone low dose (less than 25 mg) was less effective than mid‐dose mifepristone. UPA may be more effective than levonorgestrel.

Levonorgestrel users had fewer side effects than Yuzpe users, and appeared to be more likely to have a menstrual return before the expected date. UPA users were probably more likely to have a menstrual return after the expected date. Menstrual delay was probably the main adverse effect of mifepristone and seemed to be dose‐related. Cu‐IUD may be associated with higher risks of abdominal pain than ECPs.

Plain language summary

Methods of emergency contraception

Review question

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of different methods of emergency contraception to prevent pregnancy following unprotected intercourse.

Background

Emergency contraception (EC) is using a drug or copper intrauterine device (Cu‐IUD) to prevent pregnancy shortly after unprotected intercourse. Several interventions are available for EC. Information on the comparative effectiveness, safety and convenience of these methods is crucial for reproductive healthcare providers and the women they serve. Researchers in Cochrane collected and analyzed all relevant studies to answer this question.

Study characteristics

We searched 10 English‐language and three Chinese‐language databases for published studies in any language, in February 2017. We also searched grey literature databases and websites and contacted experts and authors for eligible studies. Studies had to report information on interventions to prevent pregnancy after a single act of unprotected intercourse. We included 115 randomized controlled trials with 60,479 women in this review. Ninety‐two trials were conducted in China. The evidence is up‐to‐date to February 2017.

Key results

The studies compared 25 different interventions of different types of emergency contraception. The studies showed the following.

Levonorgestrel and mifepristone were more effective than Yuzpe regimen (estradiol‐levonorgestrel combination). Our findings suggest that if 29 women per 1000 become pregnant with Yuzpe, between 11 and 24 women per 1000 will do so with the levonorgestrel, and that if 25 women per 1000 become pregnant with Yuzpe, between one and 10 women per 1000 will do so with mifepristone.

Mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg to 50 mg) was probably more effective than levonorgestrel. Low‐dose mifepristone (less than 25 mg) was probably less effective than mid‐dose mifepristone, but both were more effective than levonorgestrel (two doses of 0.75 mg). Ulipristal acetate (UPA) was also more effective than levonorgestrel.

Levonorgestrel users had fewer side effects than Yuzpe users, and might be more likely to resume menstruation before the expected date. UPA users were probably more likely to resume menstruation after the expected date. Menstrual delay was probably the main adverse effect of mifepristone and seemed to be dose‐related. Cu‐IUD may be associated with higher risks of abdominal pain than mifepristone.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence for the primary outcome (observed number of pregnancies) ranged from moderate to high, and for other outcomes ranged from very low to high. The main limitations were risk of bias (associated with poor reporting of methods), imprecision and inconsistency.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Levonorgestrel compared to Yuzpe for emergency contraception.

| Levonorgestrel compared to Yuzpe for emergency contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women seeking emergency contraception Setting: China (3), Italy (2), multinational (1); family planning clinics Intervention: Levonorgestrel Comparison: Yuzpe | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Yuzpe | Risk with Levonorgestrel | |||||

| Observed number of pregnancies (all women) | 29 per 1,000 | 17 per 1,000 (11 to 24) | RR 0.57 (0.39 to 0.84) | 4750 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Any side effect | 681 per 1,000 | 545 per 1,000 (511 to 586) | RR 0.80 (0.75 to 0.86) | 1955 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Specific side effects ‐ Nausea | 447 per 1,000 | 179 per 1,000 (161 to 197) | RR 0.40 (0.36 to 0.44) | 4750 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ Vomiting | 254 per 1,000 | 74 per 1,000 (61 to 89) | RR 0.29 (0.24 to 0.35) | 3640 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ Spotting/bleeding after treatment | 87 per 1,000 | 158 per 1,000 (119 to 210) | RR 1.82 (1.37 to 2.41) | 1614 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | |

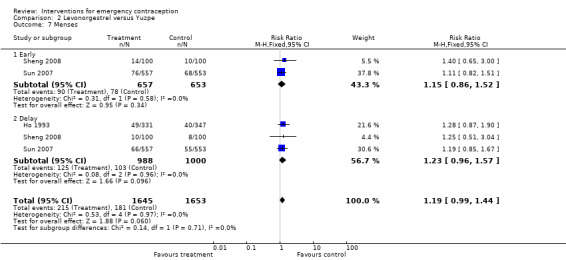

| Menses ‐ Early | 119 per 1,000 | 137 per 1,000 (103 to 182) | RR 1.15 (0.86 to 1.52) | 1310 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | |

| Menses ‐ Delay | 103 per 1,000 | 127 per 1,000 (99 to 162) | RR 1.23 (0.96 to 1.57) | 1988 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 The quality of evidence was downgraded by one level for “inconsistency” because of high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis

2 The quality of evidence was downgraded by one level for “imprecision” because the 95% CI overlaps no effect and CI fails to exclude important benefit or important harm.

3 The quality of evidence was downgraded by one level for “ serious risk of bias” associated with poor reporting of randomization methods

4 The quality of evidence was downgraded by one level for “imprecision” because the total (cumulative) sample size is lower than the calculated optimal information size (OIS)

Summary of findings 2. Mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg‐50 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg for emergency contraception.

| Mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg‐50 mg) compared to levonorgestrel 1.5 mg for emergency contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: women seeking emergency contraception Setting: China (27); family planning clinics Intervention: mifepristone, mid‐dose (25 mg‐50 mg) Comparison: levonorgestrel 1.5 mg | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with levonorgestrel 1.5 mg | Risk with mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg‐50 mg) | |||||

| Observed number of pregnancies (all women) | 35 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (16 to 29) | RR 0.61 (0.45 to 0.83) | 6052 (27 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Any side effect | 202 per 1000 | 111 per 1000 (81 to 150) | RR 0.55 (0.40 to 0.74) | 4352 (18 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| Specific side effect ‐ nausea | 80 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (39 to 109) | RR 0.81 (0.48 to 1.36) | 713 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,3 | |

| Specific side effect ‐ vomiting | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| Specific side effect ‐ spotting/bleeding after treatment | 77 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (32 to 68) | RR 0.61 (0.42 to 0.88) | 1796 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,3 | |

| Menses ‐ early | 94 per 1000 | 68 per 1000 (47 to 97) | RR 0.72 (0.50 to 1.03) | 1324 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,3 | |

| Menses ‐ delay | 108 per 1000 | 139 per 1000 (117 to 166) | RR 1.29 (1.09 to 1.54) | 3615 (17 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for serious risk of bias associated with poor reporting of randomization methods. 2We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for inconsistency because of high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis. 3We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the total (cumulative) sample size was lower than the calculated optimal information size.

Summary of findings 3. Low‐dose mifepristone (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg for emergency contraception.

| Low‐dose mifepristone (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg for emergency contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: women seeking emergency contraception Setting: China (12), UK (1), multinational (1); family planning clinics Intervention: mifepristone, low dose (< 25 mg) Comparison: levonorgestrel 1.5 mg | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with levonorgestrel 1.5 mg | Risk with low‐dose mifepristone (< 25 mg) | |||||

| Observed number of pregnancies (all women) | 20 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (10 to 20) | RR 0.72 (0.52 to 0.99) | 8752 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

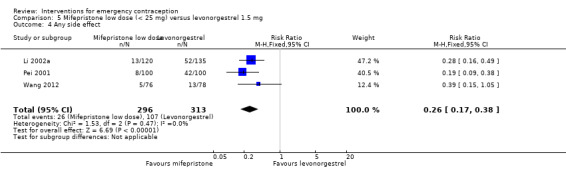

| Any side effect | 342 per 1000 | 89 per 1000 (58 to 130) | RR 0.26 (0.17 to 0.38) | 609 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| Specific side effect ‐ nausea | 133 per 1000 | 126 per 1000 (112 to 145) | RR 0.95 (0.84 to 1.09) | 6384 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | |

| Specific side effect ‐ vomiting | 15 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (8 to 41) | RR 1.22 (0.55 to 2.68) | 6085 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3,4 | |

| Specific side effect ‐ spotting/bleeding after treatment | 284 per 1000 | 173 per 1000 (153 to 196) | RR 0.61 (0.54 to 0.69) | 4598 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Menses ‐ early | 182 per 1000 | 82 per 1000 (64 to 108) | RR 0.45 (0.35 to 0.59) | 1800 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| Menses ‐ delay | 66 per 1000 | 113 per 1000 (98 to 131) | RR 1.70 (1.48 to 1.97) | 7520 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,4 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for serious risk of bias associated with poor reporting of randomization methods. 2We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the total (cumulative) sample size was lower than the calculated optimal information size. 3We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the 95% CI overlaps no effect and CI fails to exclude important benefit or important harm. 4We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for inconsistency because of high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis.

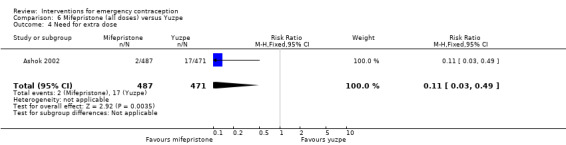

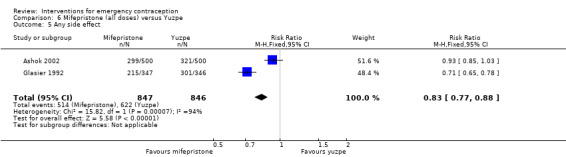

Summary of findings 4. Mifepristone (all doses) versus Yuzpe for emergency contraception.

| Mifepristone (all doses) versus Yuzpe for emergency contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: women seeking emergency contraception Setting: UK (3); family planning clinics Intervention: mifepristone (all doses) Comparison: Yuzpe | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Yuzpe | Risk with mifepristone (all doses) | |||||

| Observed number of pregnancies (all women) | 25 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (1 to 10) | RR 0.14 (0.05 to 0.41) | 2144 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Any side effect | 735 per 1000 | 610 per 1000 (566 to 647) | RR 0.83 (0.77 to 0.88) | 1693 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ nausea | 424 per 1000 | 267 per 1000 (225 to 322) | RR 0.63 (0.53 to 0.76) | 2186 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ vomiting | 135 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (9 to 27) | RR 0.12 (0.07 to 0.20) | 2186 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Specific side effects ‐ abdominal pain | 276 per 1000 | 210 per 1000 (168 to 262) | RR 0.76 (0.61 to 0.95) | 1000 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ spotting/bleeding after treatment | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| Menses ‐ delay | 110 per 1000 | 311 per 1000 (253 to 381) | RR 2.83 (2.30 to 3.47) | 1924 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for inconsistency because of high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis. 2We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the total (cumulative) sample size was lower than the calculated optimal information size.

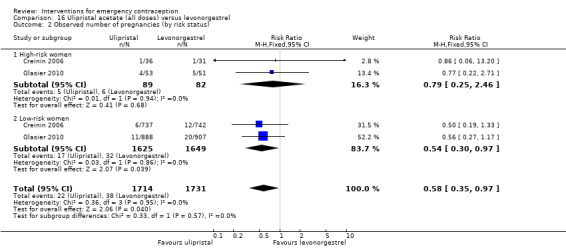

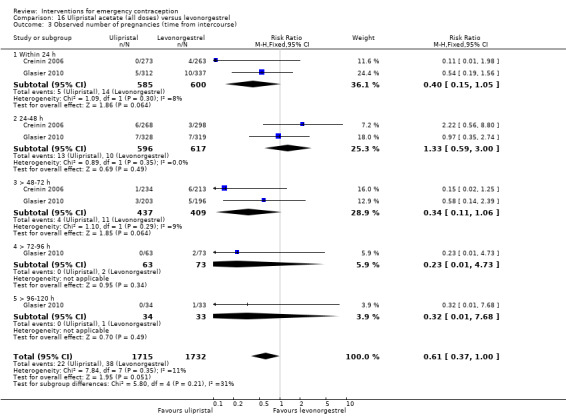

Summary of findings 5. Ulipristal acetate (all doses) versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception.

| Ulipristal acetate (all doses) versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: women seeking emergency contraception Setting: multinational (2); family planning clinics Intervention: ulipristal acetate (all doses) Comparison: levonorgestrel | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with levonorgestrel | Risk with ulipristal acetate (all doses) | |||||

| Observed number of pregnancies (all women) | 22 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (8 to 22) | RR 0.59 (0.35 to 0.99) | 3448 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Any side effect | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

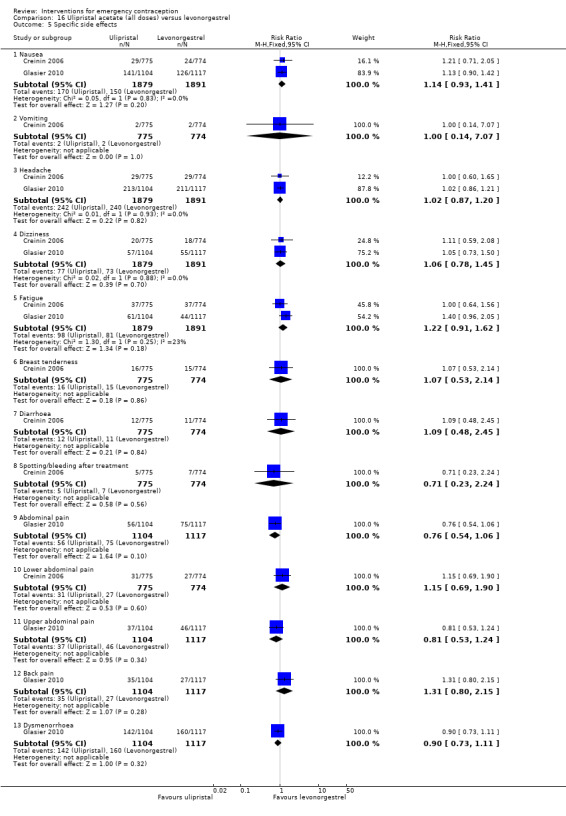

| Specific side effects ‐ nausea | 79 per 1000 | 90 per 1000 (74 to 112) | RR 1.14 (0.93 to 1.41) | 3770 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ vomiting | 3 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (0 to 18) | RR 1.00 (0.14 to 7.07) | 1549 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ spotting/bleeding after treatment | 9 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (2 to 20) | RR 0.71 (0.23 to 2.24) | 1549 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

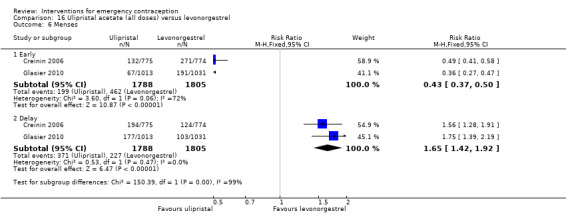

| Menses ‐ early | 256 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (95 to 128) | RR 0.43 (0.37 to 0.50) | 3593 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | |

| Menses ‐ delay | 126 per 1000 | 208 per 1000 (179 to 241) | RR 1.65 (1.42 to 1.92) | 3593 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the 95% CI overlaps no effect and CI fails to exclude important benefit or important harm. 2We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the total (cumulative) sample size is lower than the calculated optimal information size. 3We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for inconsistency because of high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis.

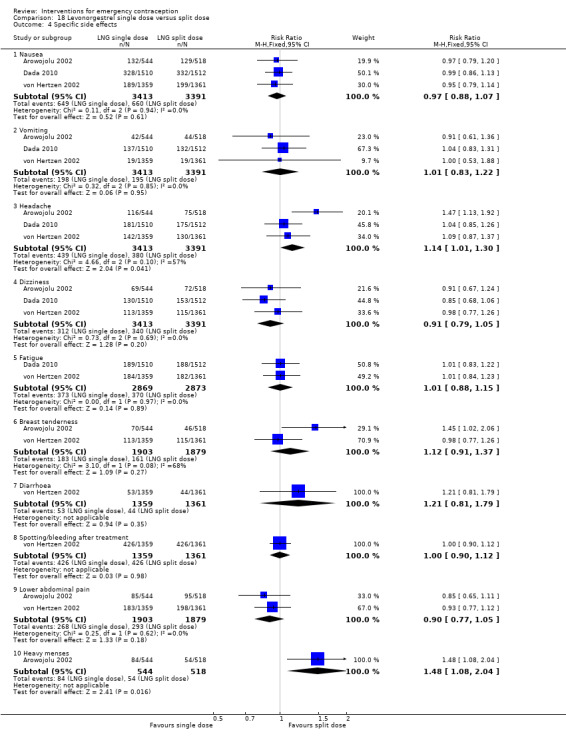

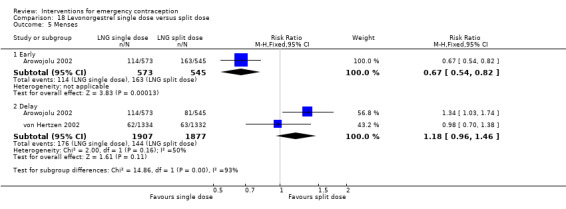

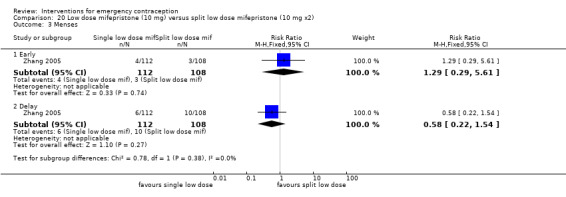

Summary of findings 6. Single‐dose levonorgestrel versus split‐dose levonorgestrel for emergency contraception.

| Single‐dose levonorgestrel versus split‐dose levonorgestrel for emergency contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: women seeking emergency contraception Setting: multinational (3); family planning clinics Intervention: levonorgestrel, single‐dose Comparison: levonorgestrel, split‐dose | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with split‐dose levonorgestrel | Risk with single‐dose levonorgestrel | |||||

| Observed number of pregnancies (all women) | 12 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (6 to 16) | RR 0.84 (0.53 to 1.33) | 6653 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Any side effect | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| Specific side effects ‐ nausea | 195 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (171 to 208) | RR 0.97 (0.88 to 1.07) | 6804 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ vomiting | 58 per 1000 | 58 per 1000 (48 to 70) | RR 1.01 (0.83 to 1.22) | 6804 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ spotting/bleeding after treatment | 313 per 1000 | 313 per 1000 (282 to 351) | RR 1.00 (0.90 to 1.12) | 2720 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Menses ‐ early | 299 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 (162 to 245) | RR 0.67 (0.54 to 0.82) | 1118 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Menses ‐ delay | 77 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (74 to 112) | RR 1.18 (0.96 to 1.46) | 3784 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the 95% CI overlaps no effect and CI fails to exclude important benefit or important harm. 2We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for inconsistency because of high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis.

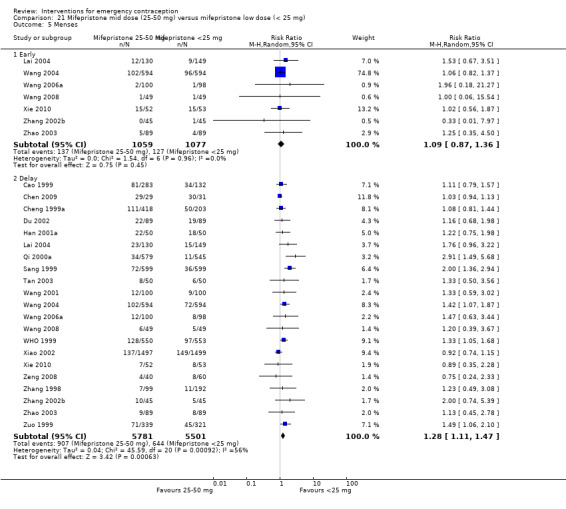

Summary of findings 7. Mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg‐50 mg) versus low‐dose mifepristone (< 25 mg) for emergency contraception.

| Mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg‐50 mg) versus low‐dose mifepristone (< 25 mg) for emergency contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: women seeking emergency contraception Setting: China (25); family planning clinics Intervention: mifepristone, mid‐dose (25 mg‐50 mg) Comparison: mifepristone, low‐doses (< 25 mg) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with low‐dose mifepristone (< 25 mg) | Risk with mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg‐50 mg) | |||||

| Observed number of pregnancies (all women) | 17 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (9 to 16) | RR 0.73 (0.55 to 0.97) | 11914 (25 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Any side effect | 88 per 1000 | 115 per 1000 (89 to 149) | RR 1.31 (1.01 to 1.70) | 2464 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ nausea | 104 per 1000 | 114 per 1000 (100 to 128) | RR 1.10 (0.97 to 1.24) | 7948 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ vomiting | 6 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (4 to 13) | RR 1.22 (0.68 to 2.17) | 6082 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ spotting/bleeding after treatment | 69 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (107 to 151) | RR 1.85 (1.55 to 2.20) | 5078 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Menses ‐ early | 118 per 1000 | 129 per 1000 (103 to 160) | RR 1.09 (0.87 to 1.36) | 2136 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| Menses ‐ delay | 117 per 1000 | 150 per 1000 (130 to 172) | RR 1.28 (1.11 to 1.47) | 11282 (21 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for risk of bias because we judged allocation concealment to be inadequate in the meta‐analysis. 2We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the 95% CI overlaps no effect and CI fails to exclude important benefit or important harm. 3We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for inconsistency because of high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis.

Summary of findings 8. Copper intrauterine device versus mifepristone (all doses) for emergency contraception.

| Copper intrauterine device versus mifepristone (all doses) for emergency contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: women seeking emergency contraception Setting: China (2); family planning clinics Intervention: copper intrauterine device Comparison: mifepristone (all doses) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with mifepristone (all doses) | Risk with copper intrauterine device | |||||

| Observed number of pregnancies (all women) | 12 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (0 to 34) | RR 0.33 (0.04 to 2.74) | 395 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| Any side effect | 84 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (0 to 83) | RR 0.06 (0.00 to 0.99) | 285 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ nausea | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| Specific side effects ‐ vomiting | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| Specific side effects ‐ lower abdominal pain | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 73.61 (4.48 to 1208.50) | 285 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| Specific side effects ‐ spotting/bleeding after treatment | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| Menses ‐ delay | 180 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 (16 to 115) | RR 0.23 (0.09 to 0.64) | 284 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for serious risk of bias associated with poor reporting of randomization method. 2We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for imprecision because the total (cumulative) sample size was lower than the calculated optimal information size.

Background

Description of the condition

Unwanted pregnancy is a common problem. Worldwide, over 40 million pregnancies end in abortion each year (Sedgh 2012; Sedgh 2014). The standard approach to this problem has been primary prevention (contraception), backed up by induced abortion. However, for a long time, 'contraception' has generally been understood to mean only anticipatory contraception. The definition of the primary prevention of unintended pregnancy could and should be expanded to include post hoc contraception (Grimes 1997).

Description of the intervention

Emergency contraception (EC) is defined as the use of a drug or device as an emergency measure to prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. From this definition it follows that methods of EC are used after coitus but before pregnancy occurs, and that they are intended as a back‐up for occasional use rather than a regular form of contraception (Van Look 1993). Although the terms 'morning after pill' and 'after‐sex pill' are also used to describe the same approach, these can cause confusion regarding the timing and purpose, and are best avoided. EC implies something not to be used routinely (there are far more effective methods for regular contraception) but which can still prevent pregnancy if other options have failed or regular contraception was not used (Webb 1995).

To date, no contraceptive method is 100% reliable and few people use their method perfectly each time they have sexual intercourse, in particularly the short‐acting contraceptives like oral pills and condoms. Furthermore, EC is useful in cases of sexual assault. EC is especially important for outreach to the 4.6 million women at risk of pregnancy but not using a regular method by providing a bridge to use of an ongoing contraceptive method (Trussell 2012).

EC is widely available in Western Europe and in China. However, use of this method is rising rapidly in low‐ and middle‐income countries. For example, the 2008 to 2009 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data showed that 22% of unmarried sexually active women in Albania had used EC. In Colombia, Kenya and Nigeria, according to data from DHS, 10% to 16% of unmarried, sexually active women used EC (ICEC 2012a, ICEC 2012b, ICEC 2012c). This proportion in Peru was 35% in 2010 (INEI 2011). However, EC is largely under‐utilised in many other countries. Examining data from 45 countries surveyed between 2000 and 2012, in 16 countries, fewer than 10% of women aged 15 to 49 years had heard of EC; in 36 countries, the rate of use of EC was less than 3% among women who had ever had sex (Palermo 2014). The low awareness of emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs) and the lack of access to EC may subject women to unsafe abortions, which contribute significantly to maternal mortality and morbidity.

Although attempted throughout history, EC methods only started to become effective in the 1960s when hormonal regimens were first introduced. Following the introduction of high‐dose oestrogens, the so‐called Yuzpe regimen, involving the combined use of oestrogen (ethinyl oestradiol 100 μg) and progestogen (levonorgestrel 0.5 mg or dl‐norgestrel 1 mg), repeated once 12 hours apart, with the first dose given within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse, became popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Yuzpe 1977).

Since the 1990s, there have been several different interventions available for EC (Glasier 1997). Interest in the development of alternative regimens has led to trials of the progestogen levonorgestrel, the anti‐gonadotropin danazol, and the anti‐progestins mifepristone and ulipristal acetate (UPA) (Trussell 2012). Like the Yuzpe regimen, these methods are recommended for use within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse although levonorgestrel and mifepristone had been tested up to 120 hours (five days) after unprotected intercourse, for research purposes Glasier 2010. The postcoital insertion of a copper intrauterine device (Cu‐IUD) is an option that can be used up to five days after the estimated time of ovulation and can be left in the uterus as a long‐term regular contraceptive method.

The main side effects caused by hormonal emergency contraceptives are nausea and vomiting, which seem to be more frequent with oestrogen‐containing regimens such as Yuzpe regimen and high‐dose oestrogen alone compared to progestogen or anti‐progestogen treatment. Mifepristone can cause menstrual delay, while levonorgestrel may cause earlier menses. IUD insertion can cause discomfort and requires trained staff and facilities. It is generally recommended that the Cu‐IUD be avoided in women at high risk of sexually transmitted diseases.

How the intervention might work

EC can prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse but it does not always work effectively. Many factors may affect the effectiveness of EC, and different methods of EC may have different effectiveness. The risk of failure of a less effective method of EC is the major factor to be taken into account when estimating the risk of pregnancy.

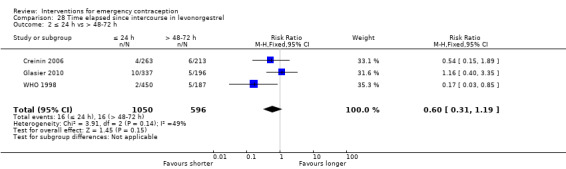

For all ECs, the risk of pregnancy is related to the cycle day of intercourse. Women who have intercourse the day before estimated day of ovulation have a fourfold increased risk of pregnancy (odds ratio (OR) 4.42, 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.33 to 8.20; P < 0.0001) compared with women having sex outside the fertile window (Glasier 2011). Time elapsed since intercourse (coitus‐treatment interval) and further acts of intercourse during the same cycle in which EC was used are two other factors affecting the success of EC. It is suggested that emergency contraception may be less effective among obese women, though clinical data are sparse (Jatlaoui 2016a). This is biologically plausible, as there is evidence that among women taking the same dose of levonorgestrel, the serum concentration of levonorgestrel is 50% lower in those who are obese (BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more) than in those with a normal or low BMI (less than 25 kg/m2) (Edelman 2016).

Levonorgestrel is used in ECPs, both in a combined Yuzpe regimen which includes estrogen, and as a levonorgestrel‐only method. The primary mechanism of action of levonorgestrel as a progestogen‐only emergency contraceptive pill is to prevent fertilisation by inhibition of ovulation (Brache 2013; Gemzell‐Danielsson 2004) and thickening of cervical mucus (Lalitkumar 2013). levonorgestrel can disrupt or inhibit ovulation in 96% of cycles if it is given in the presence of an ovarian follicle measuring 12 mm to 17 mm in diameter. Once the luteinising hormone (LH) surge has started levonorgestrel has no effect on ovulation. Review of the evidence suggests that levonorgestrel ECPs cannot prevent implantation of a fertilised egg. This explains the need to take levonorgestrel as soon as possible after intercourse, especially within 72 hours.

Ulipristal acetate (UPA) is a selective progesterone receptor modulator and also works by delaying or inhibiting ovulation. UPA remains reasonably effective even if given after the LH surge has started, delaying ovulation in 79% of cycles at this time, while levonorgestrel delays ovulation in only 14% (and placebo in 10%). Once LH has reached its peak, UPA no longer has any effect on ovulation. When UPA is given before the start of the LH surge, follicle rupture is delayed or inhibited in 100% of cycles (Baird 2015). UPA can be used up to 120 hours after intercourse (Fine 2010a), but should be taken as soon as possible after intercourse (since if the woman has not yet ovulated, the longer she delays using EC the more likely she will be close to ovulation).

Mifepristone, another selective progesterone receptor modulator, has an effect on the endometrium and can both inhibit implantation and induce abortion (Gemzell‐Danielsson 2004).

The Cu‐IUD used for EC may prevent an oocyte from being fertilised if inserted before fertilisation has occurred but will also prevent implantation if it is inserted later (Cleland 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Information on the comparative effectiveness, safety and convenience of an EC method is crucial for reproductive healthcare providers and the women they serve. The present review aims to search systematically for, and combine, all evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials relating to the effectiveness of different EC methods in order to supply the best evidence currently available on which to base recommendations for clinical practice and further research.

In the previous version of this Cochrane Review, 100 RCTs and 25 comparisons were included. The findings included evidence that intermediate‐dose mifepristone was superior to LNG and Yuzpe regimens and that low‐dose mifepristone and UPA might possibly be more effective than LNG. As this version of the review was published 5 years ago (2012), and failed to evaluate the quality of the evidence using GRADE methods, we considered that with more recent evidence and updated methods our conclusions might be changed.

Objectives

To determine which EC method following unprotected intercourse is the most effective, safe and convenient to prevent pregnancy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered RCTs comparing different EC methods, or comparing one method with expectant management or placebo for inclusion. The unit of randomization in all these studies was the individual. Only trials measuring clinical outcomes were considered for inclusion.

Types of participants

Women with regular menses requesting EC following unprotected intercourse. Women attending clinics for 'once‐a‐month' contraception in the form of luteal phase contraceptives and menstrual regulation using mifepristone and prostaglandin analogues were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

Types of interventions

To be included, the intervention had to be applied to women seeking EC following unprotected intercourse. Those studies in which similar interventions were used by women as regular postcoital contraception were not eligible. Comparisons of different delivery systems such as advance provision or over‐the‐counter delivery, and any kind of educational interventions, were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

Trials evaluating the following interventions were included in this review:

Any regimen versus no intervention/placebo. Please note that this comparison is now considered unethical and is included only for completeness.

Hormonal ECPs: comparison of different regimens

IUD compared with ECP

Combination treatments and comparison of these with other treatments alone or in combination were considered for inclusion when such data were available, including different doses.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Observed number of pregnancies (all women), including number of ectopic pregnancies (if reported)

Secondary outcomes

-

Side effects:

any side effect,

nausea,

vomiting,

headache,

dizziness,

fatigue,

breast tenderness,

diarrhoea,

spotting or bleeding,

abdominal pain,

others

Menses: early (return before the expected date), delayed (return after the expected date)

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all published and unpublished RCTs using the following search strategy, without language or date restriction and in consultation with the Information Specialists of both Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility, and Cochrane Fertility Regulation. We identified relevant trials from electronic databases and other resources.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases, trials registers and websites from their inception to 22 February 2017.

The Cochrane Central Register of Studies (CENTRAL; 2017, issue 2) via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO) (Appendix 1)

-

English language electronic databases:

Ovid MEDLINE (from 1946 to 22 February 2017) (Appendix 2);

Ovid Embase (from 1980 to 22 February 2017) (Appendix 3);

Ovid PsycINFO (from 1806 to 22 February 2017) (Appendix 4); and

EBSCO CINAHL (from inception to 22 February 2017) (Appendix 5).

-

We ran searches of other databases including:

the Database of Chinese Scientific Journals (from inception to February 2017) (左炔诺孕酮 or 米非司酮 or RU486 or UPA or ulipristal acetate or 乌利司他 or 醋酸优力司特 or 醋酸乌利司他 or Yuzpe or 紧急避孕药 or 毓婷 or 宫内节育器 or IUD or 环) and 紧急避孕 and (临床试验 or 随机对照 or 比较 or 对比) (Appendix 6);

Popline (inception to February 2017);

LILACS (inception to February 2017);

PubMed (inception to February 2017);

-

and the clinical trials registers (to 22 February 2017):

ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 7)

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal (ICTRP) (Appendix 7).

We combined the MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying RCTs, in Chapter 6, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the Embase search with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).

Searching other resources

World Health Organization (WHO) RESOURCES (February 2017). We contacted HRP (Human Reproduction Program)/WHO to seek any published or unpublished trials we had missed.

Emergency Contraception Website (February 2017). We checked the Emergency Contraception World Wide Web server operated by the Office of Population Research at Princeton University, USA, to identify any relevant publications.

Pharmaceutical companies (February 2017). We contacted the pharmaceutical companies (Bayer, Beijing Zizhu Pharmaceutical Co., Biopharm Chemical Company, Gador SA, Gedeon Richter, Laboratoire HRA Pharma, Shanghai New Hualian Pharmaceutical Co., Shenyang No. 1 Pharmaceutical Co., Teva, Xianju Pharmaceutical Co.) that are marketing dedicated products for EC to check if they knew of any unpublished trials that were eligible for inclusion in the review. All Chinese companies, and Bayer, Laboratoire HRA Pharma, and Teva responded but they did not have information on, or knowledge of, other trials.

Others (February 2017). We performed the usual steps in the searches of a systematic review, such as searching the reference lists of published articles and contacting investigators active in this area.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We initially checked the trials identified by our search strategy for duplicates and relevance for the review by looking at the titles and abstracts. If it was not possible to exclude a publication by looking at the title or the abstract, we retrieved the full paper. Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion and resolved any differences by discussion and consultation of other review authors if needed. Trials were excluded if the loss to follow‐up was greater than 20%. There were no language preferences in the search or the selection of articles.

Data extraction and management

We systematically extracted data from each trial for the following variables.

Intervention and control treatment. Because of the large variation in mifepristone doses, we categorised the doses arbitrarily (before data extraction) as high (more than 50 mg), mid (25 mg to 50 mg) and low (less than 25 mg). We also conducted separate meta‐analyses to validate our groupings of the different doses.

Clinical outcomes: observed number of pregnancies, ectopic pregnancies, side effects (any, nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, fatigue, breast tenderness, spotting/bleeding, diarrhoea, others), timing of menses, coitus‐treatment interval, high‐/low‐risk behaviour.

Methodology: random allocation techniques, blinding, post‐randomisation exclusions, loss to follow‐up.

Demographics: type of healthcare setting, city, country, total number of women included, and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

For articles written in English, two review authors independently carried out data extraction and another review author checked the data entry.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011) to assess: selection (random sequence generation and allocation concealment); performance (blinding of participants and personnel); detection (blinding of outcome assessors); attrition (incomplete outcome data); reporting (selective reporting); and other bias. We assigned judgements as recommended in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion. We described all judgements fully and presented the conclusions in the 'Risk of bias' table, which we incorporated into the interpretation of review findings as part of the GRADE assessment of the evidence (Summary of findings tables) (Characteristics of included studies).

Measures of treatment effect

We used Review Manager 5 (RevMan5) (RevMan 2014) to calculate treatment effects using risk ratio (RR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used risk difference (RD) to analyze effects when there were very few or no events and the number of participants was large. We presented 95% CIs for all outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

Analysis was per woman.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to extract data from all studies that would allow intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. For outcomes with loss to follow‐up, the number of women with outcome data was taken as the denominator (available case analysis). In the levonorgestrel versus Yuzpe comparison and levonorgestrel versus mid‐dose mifepristone, we imputed outcomes for missing participants under two extreme scenarios (i.e. all missing in one arm had an event and all missing in the other arm did not have an event and vice versa).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We reviewed heterogeneity in the setting, interventions, and outcomes of included studies in order to make a qualitative assessment of the extent to which the included studies were similar to each other. We examined the forest plots visually to assess the levels of heterogeneity. We considered meta‐analyses with a P value for the Chi2 test of less than 0.1 to have considerable statistical heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). We used an I2 statistic of 50% or more to quantify the level of statistical heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

The comprehensive search strategy for this review helped to reduce the risk of reporting bias. If there were 10 or more studies in an analysis, we used a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

We performed meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect model, where two or more trials with suitable data and homogeneity existed (I2 greater than 50%). In case of heterogeneity (P < 0.10), we used the random‐effects model to produce summary estimates (except when heterogeneity occurred in subgroup analyses where it was not possible to conduct separate analyses).

We planned to make the following comparisons.

Any regimen versus no intervention/placebo

-

Hormonal ECPs: comparison of different regimens

levonorgestrel versus Yuzpe

levonorgestrel versus anordrin

mifepristone versus levonorgestrel

mifepristone versus Yuzpe

mifepristone versus anordrin

mifepristone versus mifepristone + anordrin

mifepristone versus mifepristone + misoprostol

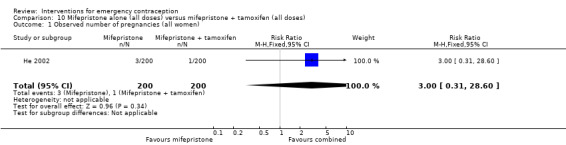

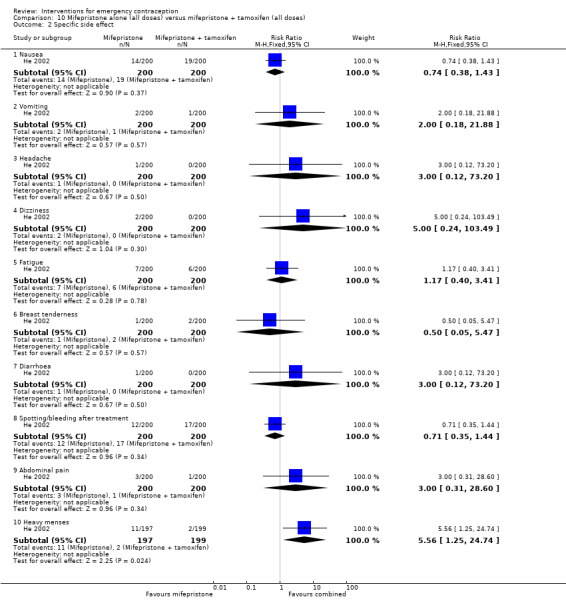

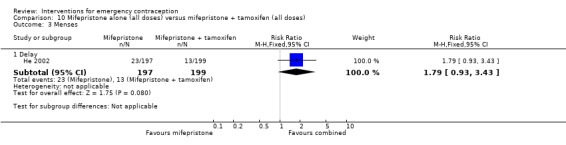

mifepristone versus mifepristone + tamoxifen

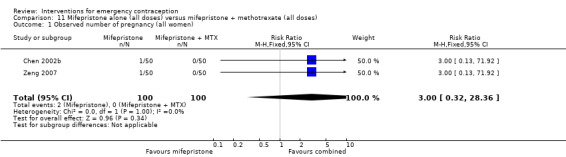

mifepristone versus mifepristone + methotrexate

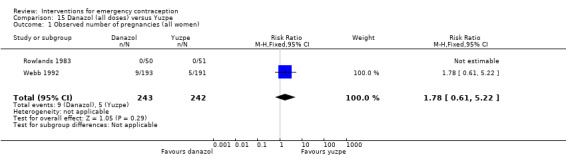

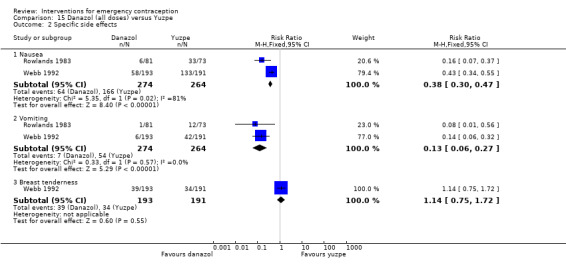

mifepristone versus danazol

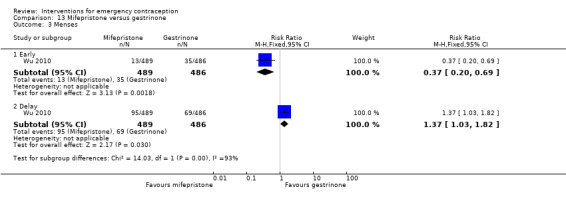

mifepristone versus gestrinone

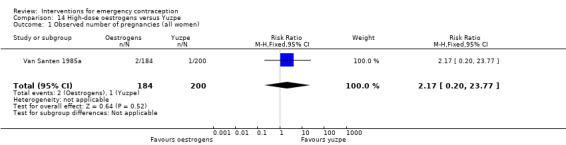

High‐dose oestrogen versus Yuzpe

danazol versus Yuzpe

UPA versus levonorgestrel

drug/dose comparisons

others

IUD comparisons to ECPs

We have produced 'Summary of findings' tables to present each outcome for the main comparisons.

Assessment of quality of evidence

Two review authors independently rated the overall quality of evidence (high, moderate, low or very low) for each of our seven main outcomes using the GRADE system, with any disagreements resolved via consensus or, if required, by consulting a third review author (GRADEpro GDT 2014).

The GRADE system defines the quality of the body of evidence for each review outcome regarding the extent to which one can be confident in the review findings. GRADE criteria include:

risk of bias;

consistency of effect;

imprecision;

indirectness; and

publication bias.

With respect to assessment of imprecision, we made the judgement based on published guidance for the use of GRADE (Guyatt 2011).

"If the optimal information size (OIS) criterion is not met, rate down for imprecision, unless the sample size is very large (at least 2,000 and perhaps 4,000 patients)"

"If the OIS criterion is met and the 95% CI excludes no effect (i.e. CI around RR excludes 1.0) precision adequate"

"If OIS is met, and CI overlaps no effect (i.e. CI includes RR of 1.0) rate down if CI fails to exclude important benefit or important harm."

If there were very few or no events and the number of participants was large, we made judgements about imprecision based on the absolute (rather than the relative) effect measures. Wide CIs around a relative risk effect estimate may translate to clinically small differences in absolute effects. We consulted Figure five in Guyatt 2011 to estimate the OIS, as an alternative to calculating the OIS. For comparisons in which most of the studies failed to provide adequate details of their randomization methods, we did not downgrade the evidence for risk of bias if the analysis also included a large study at low risk of bias which had findings consistent with the smaller studies.

We used the four GRADEpro GDT 2014 quality ratings to describe the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome and we included these in the 'Summary of findings' table:

High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect

Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different

Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect

Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

There are eight main comparisons in our review (levonorgestrel versus Yuzpe, levonorgestrel single versus split dose, mifepristone mid‐dose versus levonorgestrel, mifepristone low‐dose versus levonorgestrel, UPA versus levonorgestrel, mifepristone mid‐dose versus mifepristone low‐dose, mifepristone versus Yuzpe, Cu‐IUD versus mifepristone). For each comparison, the primary outcome measure was the pregnancy rate in women receiving different regimens (or control). Each of the 'Summary of findings' tables lists the following seven outcomes.

Observed number of pregnancies (all women)

Any side effect

Specific side effects ‐ nausea

Specific side effects ‐ vomiting

Specific side effects ‐ spotting/bleeding after treatment

Specific side effects ‐ abdominal pain

Menses ‐ early/delayed

We justified, documented, and incorporated judgements into reporting of results for each outcome, describing our reasons for downgrading in particular.

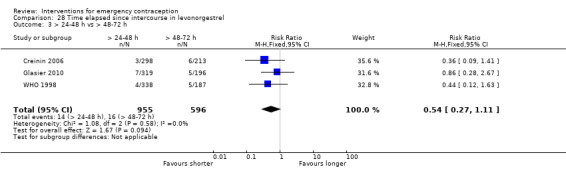

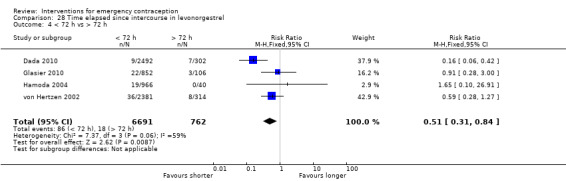

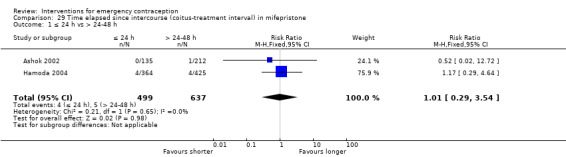

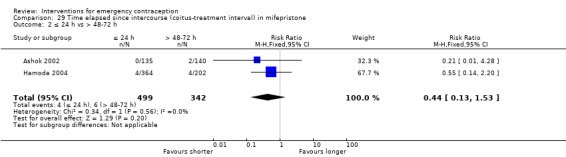

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Several factors may affect the success of EC and we considered subgroup analyses when there were sufficient data in an appropriate format to allow such analyses. We considered the following categories for subgroup analyses.

-

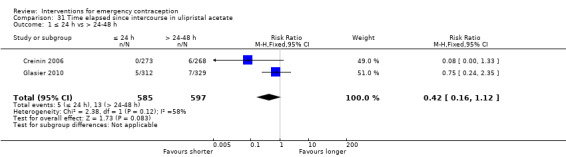

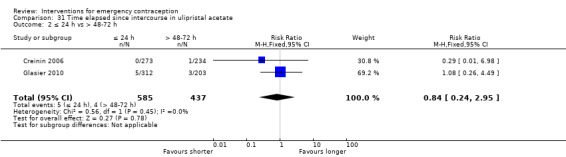

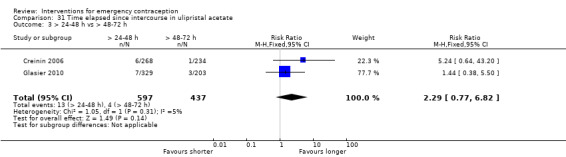

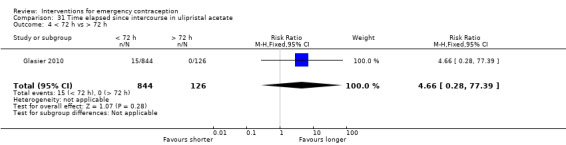

Time elapsed since intercourse (coitus‐treatment interval)

24 hours or less

more than 24 hours to 48 hours

more than 48 hours to 72 hours

more than 72 hours to 120 hours

more than 120 hours

-

Risk status

high‐risk: women who had further acts of intercourse during the same cycle in which EC was used

low‐risk: women without further acts of coitus during that cycle

-

BMI

obese: BMI 30 kg/m2 or above

overweight: BMI 25 kg/m2 to 30 kg/m2

lower BMI: less than 25 kg/m2

We considered meta‐analyses with a P value for the Chi2 test of less than 0.1 to have considerable statistical heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). We used an I2 statistic of 50% or more to quantity the level of statistical heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). Where the I2 statistic was over 50%, we considered whether there were any methodological or clinical differences between the studies that might explain the inconsistency in findings.

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analyses were planned.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

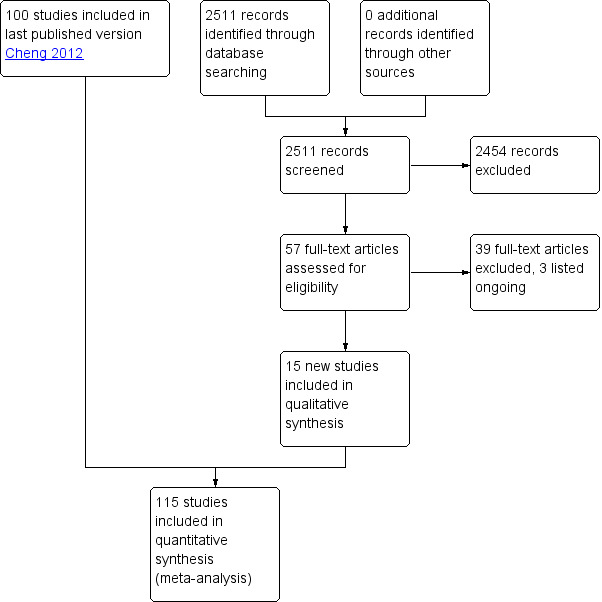

We included 115 studies with 60,479 women in this review (Figure 1). Ninety‐two trials were conducted in China. All Chinese trials were relatively recent (earliest trial published in 1993) indicating the interest in EC research in China. Except for the Ellertson 2003a, Glasier 2010; von Hertzen 2002; WHO 1998; WHO 1999 trials, all had been conducted in a single country, although some were multicenter trials. WHO trials were multinational involving large numbers of diverse populations (see Characteristics of included studies).

1.

Study flow diagram

Three trials are ongoing, all of which are registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01539720; NCT02175030; NCT02577601). They compared ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel IUS; Cu‐IUD versus levonorgestrel IUD; ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol birth control pill (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Included studies

Design

All the included studies were RCTs.

We included Askalani 1987 in the review because random allocation was explicitly mentioned. Unfortunately, no other methodological details were available for this trial. One trial (Webb 1992) was stopped early for effectiveness reasons. Sixteen trials reported appropriate power calculations for the sample size (Arowojolu 2002; Ashok 2002; Creinin 2006; Dada 2010; Ellertson 2003a; Glasier 2010; Hamoda 2004; Hoseini 2013; Ngai 2005; Sang 1999; von Hertzen 2002; Webb 1992; WHO 1998; WHO 1999; Wu 2010; Xiao 2002).

Participants

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were similar with some minor differences between trials. In general, women attending after 72 hours (after 120 hours in Cu‐IUD, some mifepristone and levonorgestrel trials), with multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse, with irregular menstrual periods and those using hormonal contraception were excluded. All trials except Sang 1999 started the intervention as soon as the women came to the clinic. Sang 1999 included only women who had had unprotected intercourse 24 to 96 hours before attending the clinic.

Interventions

Eighteen out of 115 trials had two or more treatment arms. Fifty‐six trials involved dose‐comparison studies of mifepristone in doses from 5 mg to 600 mg. Forty‐one trials compared levonorgestrel with mifepristone. Six trials compared levonorgestrel with the Yuzpe regimen. Three trials (Arowojolu 2002; Dada 2010; von Hertzen 2002) compared a split dose with a single dose of levonorgestrel and one trial compared a 24‐hour with a 12‐hour double‐dose regimen of levonorgestrel. Two trials (Creinin 2006; Glasier 2010) compared UPA, a second‐generation progesterone receptor modulator, with levonorgestrel. One trial (Wu 2010) compared mifepristone with gestrinone. Other interventions were high‐dose oestrogen, danazol and Cu‐IUD. Anordrin is a steroid hormone with weak oestrogenic effects and is only used in China as a visiting‐contraceptive pill (a type of oral pill that is used for couples who do not cohabit but visit home for a short period. It can start at any day during a menstrual cycle, one pill a day continuing no less than 14 days). In Chinese EC trials, investigators used locally manufactured mifepristone and levonorgestrel.

Two studies (Su 2001; Wang 2000a) had three treatment arms (levonorgestrel versus mifepristone versus Cu‐IUD) but the Cu‐IUD comparison was not randomized. Hence, we excluded this comparison and included only the mifepristone vs levonorgestrel comparison.

Outcomes

Most of the trials reported observed number of pregnancies in comparison to expected number of pregnancies according to estimated probability of pregnancy on the day of the menstrual cycle when unprotected intercourse took place. This information is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table without a formal summary analysis.

In general, side effects were assessed by women themselves on diary charts.

Excluded studies

For this update of the review we excluded 2454 records after initial screening (Figure 1). We excluded 39 studies after examining 57 full‐text articles. Most of these were case‐series, reports without a comparison group, EC education or meta‐analysis. Six studies (Dong 2007; Li 2005a; Liu 2002a; Tian 2000; Turok 2010; Zhang 1999a) compared Cu‐IUDs versus mifepristone with or without levonorgestrel by informed choice (i.e. not randomly allocated). Two studies (Polakow 2013, Shaaban 2013) compared EC with lactational amenorrhoea method (LAM) (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

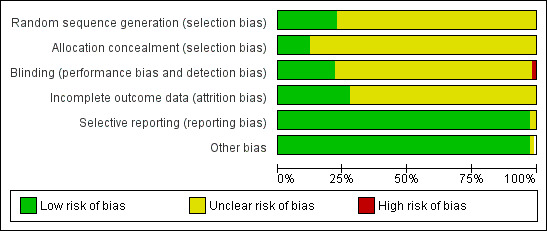

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Twenty‐five trials (Arowojolu 2002; Ashok 2002; Carbonell 2015; Cheng 1999a; Creinin 2006; Dada 2010; Ellertson 2003a; Glasier 2010; Hamoda 2004; He 2002; Hoseini 2013; Liu 2000; Ngai 2005; Qi 2000a; Van Santen 1985a; von Hertzen 2002; Wang 2001; Webb 1992; WHO 1998; WHO 1999; Wu 1999a; Wu 2002; Wu 2010; Zhang 2012; Zuo 1999) had detailed explanation of randomization and we rated them as low risk of bias (see 'Risk of bias' tables in Characteristics of included studies). Most of the remaining trials had insufficient information on randomization and concealment of allocation, and only used terms such as 'randomly allocated', which we rated as unclear risk of bias (Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

We included Askalani 1987 in the review because they explicitly mentioned random allocation. Unfortunately, no other methodological details were available for this trial. One trial (Webb 1992) was stopped early for effectiveness reasons. Sixteen trials reported appropriate power calculations for the sample size (Arowojolu 2002; Ashok 2002; Creinin 2006; Dada 2010; Ellertson 2003a; Glasier 2010; Hamoda 2004; Hoseini 2013; Ngai 2005; Sang 1999; von Hertzen 2002; Webb 1992; WHO 1998; WHO 1999; Wu 2010; Xiao 2002).

Blinding

Twenty‐three trials were reported as double‐blinded (Arowojolu 2002; Carbonell 2015; Creinin 2006; Dada 2010; Ellertson 2003a; He 2002; Hoseini 2013; Lin 2000; Liu 2000; Ngai 2005; Qi 2000a; Van Santen 1985a; von Hertzen 2002; Wang 2001; Wei 2002a; WHO 1998; WHO 1999; Wu 1999a; Wu 2002; Wu 2010; Xiao 2002; Zhang 2005; Zuo 1999) and two as single‐blinded (Glasier 2010; Sang 1999) (Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

Incomplete outcome data

ITT analysis was available (or possible) for the Creinin 2006; Glasier 2010; Ho 1993; Ngai 2005; WHO 1998; WHO 1999; Xiao 2002 trials and not mentioned in the other studies. Thirty trials (Arowojolu 2002; Ashok 2002; Carbonell 2015; Chen 2002a; Cheng 1999a; Creinin 2006; Ding 2005; Ellertson 2003a; Fan 2001a; Farajkhoda 2009; Glasier 1992; Glasier 2010; Hamoda 2004; He 2002; Ho 1993; Lai 2004; Liu 2000; Ngai 2005; Rowlands 1983; Sang 1999; von Hertzen 2002; Wang 2003; WHO 1998; WHO 1999; Wu 1999a; Wu 2002; Wu 2010; Xiao 2002; Zhang 1998; Zuo 1999) reported the number of lost follow‐up or post‐randomisation exclusions. The average proportion of loss to follow‐up or post‐randomisation exclusion was 3.3% (range 0.2% to 16.9%). Although several trials did not mention post‐randomisation exclusions, these studies did not explicitly mention ITT analyses either. As there were only a few reported pregnancies, it was possible that some pregnancies could well have been excluded after randomization (Webb 1992) (Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

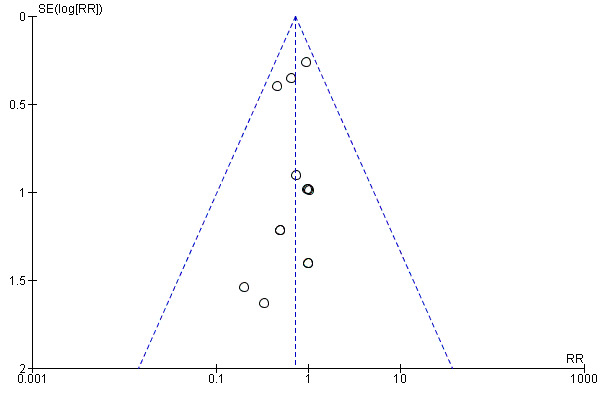

Selective reporting

We used a funnel plot to explore the possibility of reporting bias when the intervention included more than eight studies. Funnel plots for the primary outcomes (observed number of pregnancies) of the comparison between low‐dose mifepristone and levonorgestrel showed asymmetric features, indicating possible reporting bias. We rated all the other studies as at low risk of selective reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential source of bias was identified and all studies were rated as at low risk in this domain.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8

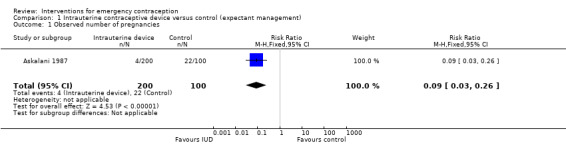

1. Any regimen versus no intervention/placebo

1.1 IUD versus expectant management

Askalani 1987 compared Cu‐IUD (Cu‐T 200) insertion with expectant management in women requesting EC within four days of unprotected intercourse.

1.1.1 Observed number of pregnancies

Notwithstanding the ethical aspects of this trial, the report was brief and only reported data on number of pregnancies. The evidence suggested a lower number of pregnancies in the IUD group (RR 0.09, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.26,1 RCT, n = 300) (Analysis 1.1). This indicated that IUD use would significantly decrease the number of pregnancies compared to expectant management, which suggests that if the observed number of pregnancies following expectant management is assumed to be 220 per 1000 women, the number following IUD would be between 7 to 57 per 1000 women.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intrauterine contraceptive device versus control (expectant management), Outcome 1 Observed number of pregnancies.

1.1.2 Side effects

No data were available.

1.1.3. Effects on menses

No data were available.

2. Hormonal ECPs: comparison of different regimens

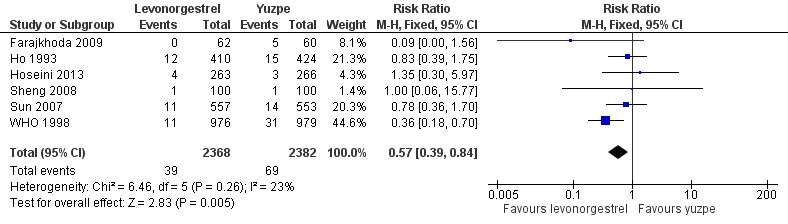

2.1 Levonorgestrel versus Yuzpe regimen

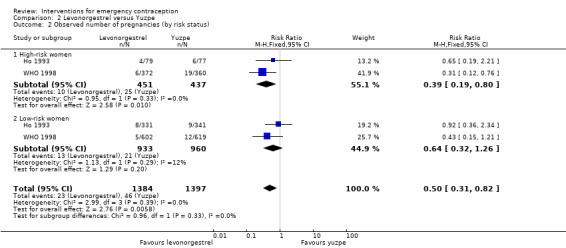

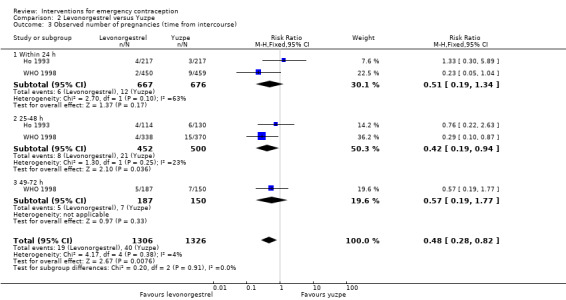

Six trials (three Chinese (Ho 1993; Sheng 2008; Sun 2007), two Iranian (Farajkhoda 2009; Hoseini 2013) and one multinational (WHO 1998)) compared the Yuzpe regimen with levonorgestrel 0.75 mg given twice, 12 hours apart. The six studies recruited a total of 4750 women.

2.1.1 Observed number of pregnancies

The levonorgestrel regimen was associated with fewer pregnancies than the Yuzpe regimen (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.84, 6 RCTs, n = 4750, I2 = 23%, high‐quality evidence) (Figure 4; Analysis 2.1; Table 1). The evidence suggests that if the chance of pregnancy using Yuzpe is assumed to be 29 per 1000 women, the chance of pregnancy using levonorgestrel would be between 11 to 24 per 1000 women.

4.

Forest plot of comparison 2.1: levonorgestrel versus Yuzpe, outcome 2.1.1 Observed number of pregnancies (all women)

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Levonorgestrel versus Yuzpe, Outcome 1 Observed number of pregnancies (all women).

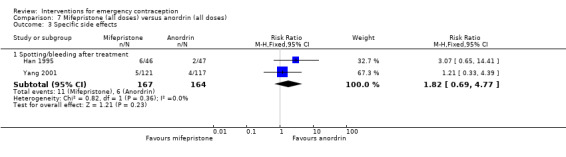

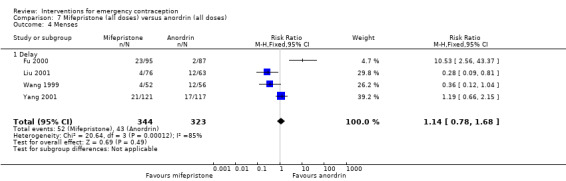

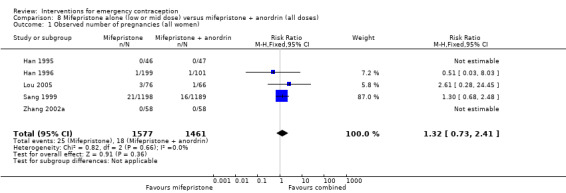

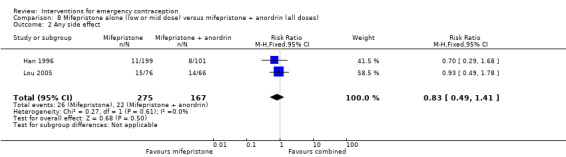

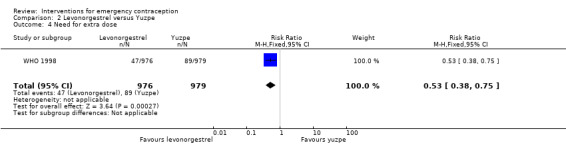

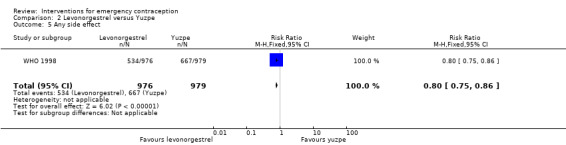

2.1.2. Side effects

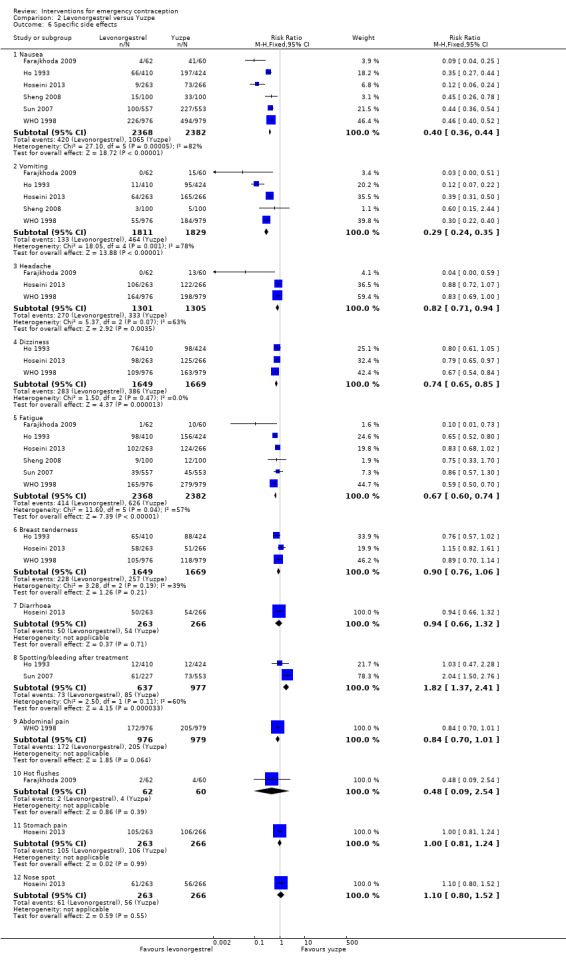

Levonorgestrel was associated with fewer overall side effects than Yuzpe (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.86, 1 RCT, n = 1955, high‐quality evidence) (Table 1) and probably with fewer complaints of nausea (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.44, 6 RCTs, n = 4750, I2 = 82%, moderate‐quality evidence), vomiting (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.35, 5 RCTs, n = 3640, I2 = 78%, moderate‐quality evidence), spotting/bleeding (RR 1.82, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.41, 2 RCTs, n = 1614 , I2 = 60%, moderate‐quality evidence), headache (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.94, 3 RCTs, n = 2606, I2 = 63%), dizziness (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.85, 3 RCTs, n = 3318, I2 = 0%) and fatigue (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.74, 6 RCTs, n = 4750, I2 = 57%). There was no conclusive evidence of a difference between the groups for breast tenderness (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.06, 3 RCTs, n = 3318, I2 = 39%) or abdominal pain (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.01), although findings suggested a benefit for levonorgestrel. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the groups for other reported side effects, which included diarrhoea, hot flushes, stomach pain and "nose spot" (Analysis 2.6; Table 1).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Levonorgestrel versus Yuzpe, Outcome 6 Specific side effects.

2.1.3. Effects on menses

There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the groups in the rates of early menses (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.52; 2 RCTs, n = 1310; low‐quality evidence) or menstrual delay (RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.57; 3 RCTs, n = 1988; I2 = 0%, low‐quality evidence) (Table 1).

2.2 Levonorgestrel versus anordrin

One trial from China (Xu 2000a) compared levonorgestrel split‐dose regimen with anordrin (7.5 mg, two doses, 12 hours apart, then 7.5 mg per day for eight days) in 172 women.

2.2.1 Observed number of pregnancies

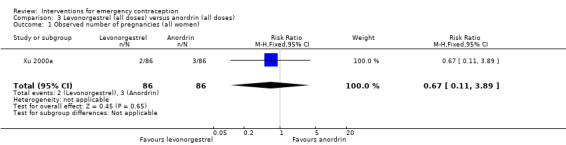

The data were too imprecise to determine whether there was a difference between the two regimens in pregnancy rates (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.89, 1 RCT, n = 172) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Levonorgestrel (all doses) versus anordrin (all doses), Outcome 1 Observed number of pregnancies (all women).

2.2.2 Side effects

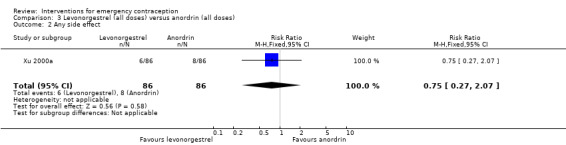

The data were too imprecise to determine whether there was a difference between the two regimens in overall side effects (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.27 to 2.07, 1 RCT, n = 172) (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Levonorgestrel (all doses) versus anordrin (all doses), Outcome 2 Any side effect.

No data were available on any of our other secondary outcomes

2.3 Mid‐dose mifepristone (25 mg to 50 mg) versus levonorgestrel

Twenty‐seven trials (Cao 2011; Chen 2008; Chen 2013; Chen 2015; Cheng 2009; Gan 2007; Han 1999a; Hu 2003; Jin 2012; Li 2000a; Li 2005b; Liang 2001; Liao 2003; Liu 2009; Qi 2003; Shao 2010; Su 2001; Sun 2000; Sun 2003; Tao 2014; Wang 2000b; Wang 2003; Xu 2000a; Xu 2000b; Ye 2013; Zhang 2000; Zhang 2014), all conducted in China, compared levonorgestrel (2939 women), all used a 12‐hour split‐dose regimen with mid‐dose mifepristone (3113 women).

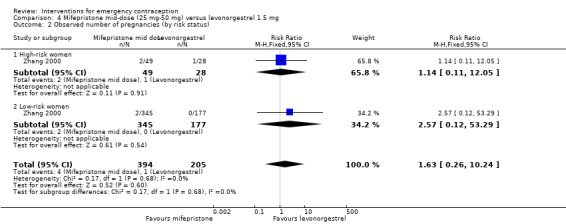

2.3.1 Observed number of pregnancies

Overall, the effectiveness of mid‐dose mifepristone was probably better than that of levonorgestrel, with lower pregnancy rates (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.83, 27 RCTs, n = 6052, I2 = 0%, moderate‐quality evidence) (Analysis 4.1; Table 2). The evidence suggested that if the chance of pregnancy following levonorgestrel is assumed to be 35 per 1000 women, the chance of pregnancy following mid‐dose mifepristone would be between 16 to 29 per 1000 women.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mifepristone mid‐dose (25 mg‐50 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 1 Observed number of pregnancies (all women).

Su 2001 reported a case of ectopic pregnancy in the levonorgestrel group.

This result was confirmed with simulated ITT analyses. When we assumed that all missing participants had the event in the levonorgestrel group, but none in the mifepristone group, the estimated RR was 0.50 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.77) and when we assumed that no missing women had an event in the levonorgestrel group, but that all the women in the mifepristone group did, the estimated RR was 0.57 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.88).

Funnel plots for the observed number of pregnancies between mid‐dose mifepristone and levonorgestrel did not suggest reporting bias.

2.3.2. Side effects

Eighteen trials reported the overall side‐effect rate and suggested that mifepristone may be more tolerable than levonorgestrel (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.74, 18 RCTs, n = 4352, I2 = 72%, low‐quality evidence) (Analysis 4.3; Table 2).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mifepristone mid‐dose (25 mg‐50 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 3 Any side effect.

The data were too imprecise to determine whether there was a difference between the groups for specific types of side effects, including nausea, headache, dizziness, breast tenderness or abdominal pain (Analysis 4.4, low‐quality evidence) except that spotting/bleeding after treatment appeared to be less common in the mifepristone group (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.88, 9 RCTs, n = 1796, I2 = 29%, low‐quality evidence) (Analysis 4.4; Table 2).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mifepristone mid‐dose (25 mg‐50 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 4 Specific side effect.

2.3.3. Effects on menses

Women who took mifepristone were probably more likely to have a delay in menses than those who took levonorgestrel (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.54, 17 RCTs, n = 3615, I2 = 31%, moderate‐quality evidence) (Analysis 4.5). There was no clear evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of early menses (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.03, 7 RCTs, n = 1324, low‐quality evidence) (Table 2).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Mifepristone mid‐dose (25 mg‐50 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 5 Menses.

2.4 Low‐dose mifepristone (less than 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel

Twelve Chinese studies (Bu 2006; Dong 2009; Li 2002a; Lei 2013; Lin 2000; Liu 2000; Pei 2001; Sheng 2002; Wang 2012; Wang 2000a; Wu 1999a; Zhang 2012), one UK study (Hamoda 2004) and one multinational WHO study (von Hertzen 2002) compared low‐dose mifepristone (3688 women) versus levonorgestrel (5064 women).

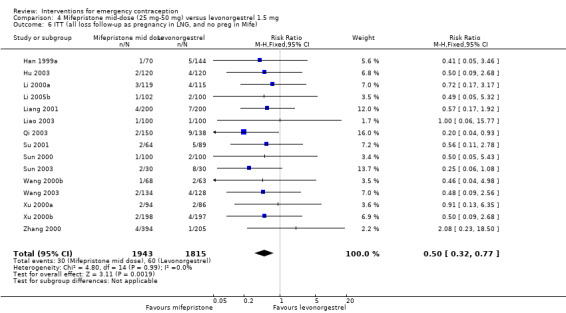

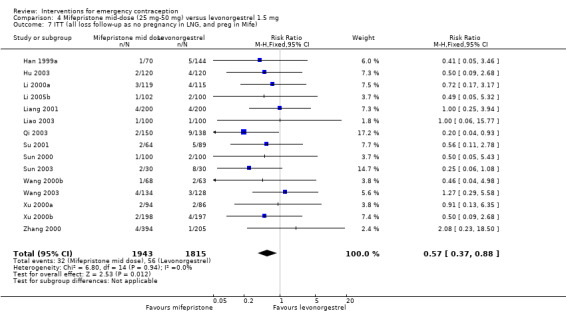

2.4.1 Observed number of pregnancies

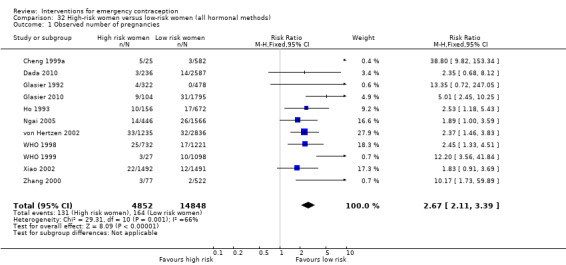

When we pooled all the studies, there was evidence that there was a difference in effectiveness between low‐dose mifepristone regimens and levonorgestrel, with fewer pregnancies in the low‐dose mifepristone group (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.99, 14 RCTs, n = 8752, I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence) (Analysis 5.1; Table 3). Funnel plots for the primary outcomes (observed number of pregnancies) showed asymmetry, suggesting possible reporting bias (Figure 5). The evidence suggested that if the chance of pregnancy following levonorgestrel is assumed to be 20 per 1000 women, the chance of pregnancy following low‐dose mifepristone would be between 10 to 20 per 1000 women.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mifepristone low dose (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 1 Observed number of pregnancies (all women).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison 2.4: Low‐dose mifepristone (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, outcome 2.4.1 Observed number of pregnancies (all women)

Additional analysis of data from one trial (von Hertzen 2002) indicated that the above conclusions were not modified by whether women abstained from further acts of intercourse or not (P = 0.14 for the interaction test), or by the time elapsed (within or after 72 hours) from intercourse to treatment administration (P = 0.99 for the interaction test) (Hamoda 2004; von Hertzen 2002). When we assumed that all women lost to follow‐up in the levonorgestrel group became pregnant, whereas none of those lost to follow‐up in the mifepristone group did, results indicated that mifepristone was associated with significantly lower risk of pregnancy than levonorgestrel (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.50 to 0.98) (Figure 6; Analysis 5.7). However, there was no evidence of a difference between the groups when we assumed that none of the women lost to follow‐up in the levonorgestrel group became pregnant but all those in the mifepristone group did (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.05) (Analysis 5.8).

6.

Forest plot of comparison 2.4: Low‐dose mifepristone (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, outcome 2.4.1 ITT (all loss follow‐up as pregnancy in levonorgestrel, and no pregnancy in mifepristone)

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mifepristone low dose (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 7 ITT (all loss follow‐up as pregnancy in LNG, and no preg in Mifepristone).

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mifepristone low dose (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 8 ITT (all loss follow‐up as no pregnancy in LNG, and preg in Mifepristone).

2.4.2 Side effects

The low‐dose mifepristone group appeared to have fewer overall side effects than the levonorgestrel group (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.38, 3 RCTs, n = 609, I2 = 0%, low‐quality evidence) (Analysis 5.4; Table 3). There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of nausea or abdominal pain (Analysis 5.5; Table 3). There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the groups for other specific side effects such as vomiting, headache, dizziness, fatigue, breast tenderness, diarrhoea, or hot flushes, but low‐dose mifepristone was associated with a lower risk of spotting or bleeding after treatment (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.69, 5 RCTs, n = 4598, I2 = 0%, high‐quality evidence) (Analysis 5.5, Table 3).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mifepristone low dose (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 4 Any side effect.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mifepristone low dose (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 5 Specific side effect.

2.4.3 Effects on menses

Early return of menstruation was probably less frequent in the mifepristone group than in the levonorgestrel group (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.59, 5 RCTs, n = 1800, I2 = 0%, low‐quality evidence). Delay in menstruation was probably more frequent in the mifepristone group (RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.48 to 1.97, 9 RCTs, n = 7520, I2 = 51%, low‐quality evidence) (Analysis 5.6, Table 3).

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mifepristone low dose (< 25 mg) versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, Outcome 6 Menses.

There were no trials that compared high‐dose (more than 50 mg) mifepristone with levonorgestrel.

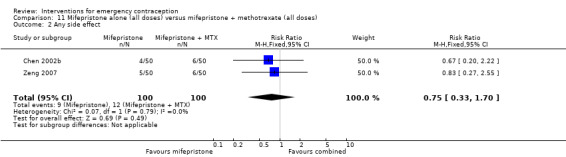

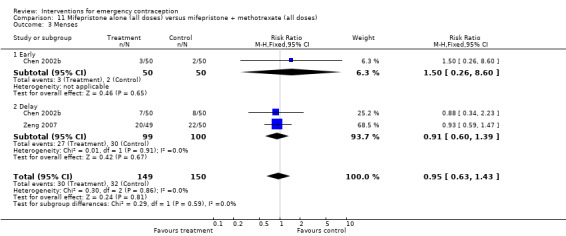

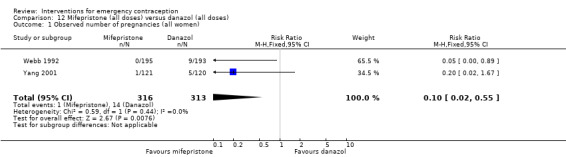

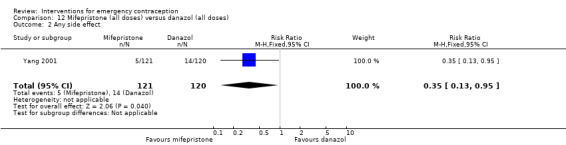

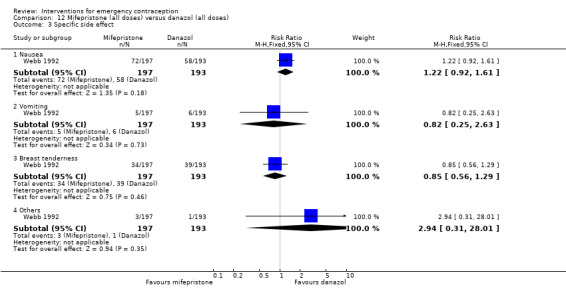

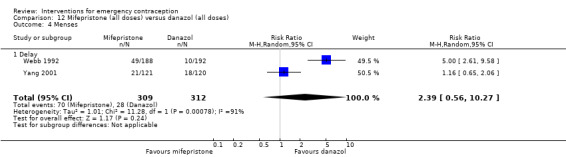

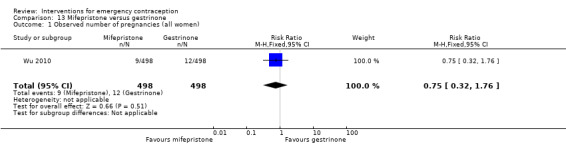

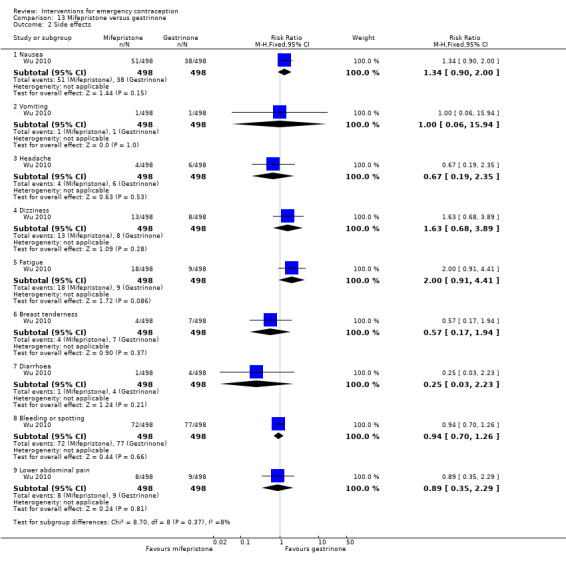

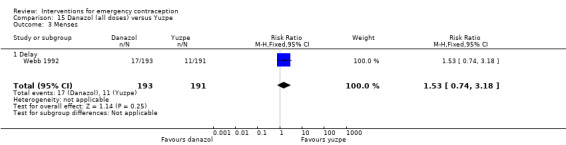

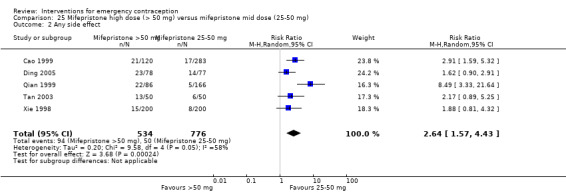

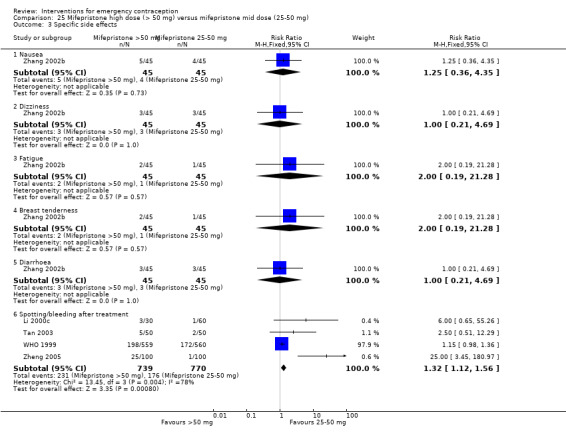

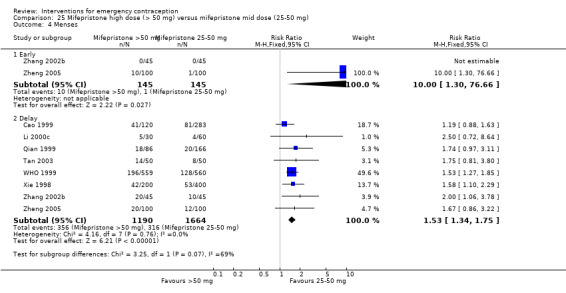

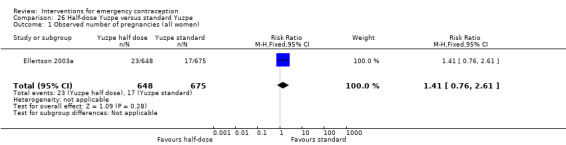

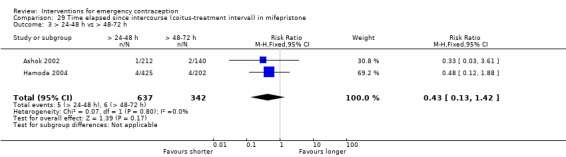

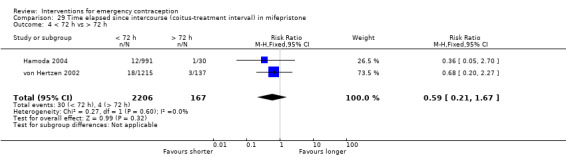

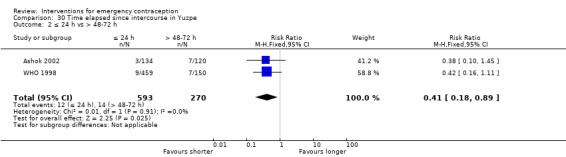

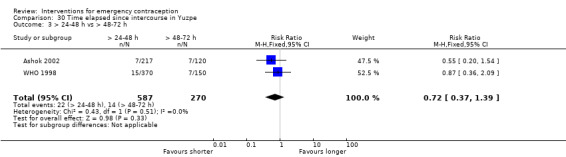

2.5 Mifepristone versus Yuzpe regimen