Cerebellar-based learning is thought to rely on synaptic plasticity, particularly at synaptic inputs to Purkinje cells. Recently, however, other complementary mechanisms have been identified. Intrinsic plasticity is one such mechanism, and depends in part on the downregulation of calcium-dependent SK-type K+ channels, which contribute to a medium-slow afterhyperpolarization (AHP) after spike bursts, regulating membrane excitability.

Keywords: cerebellum, engram, learning, memory, neuron, plasticity

Abstract

Cerebellar-based learning is thought to rely on synaptic plasticity, particularly at synaptic inputs to Purkinje cells. Recently, however, other complementary mechanisms have been identified. Intrinsic plasticity is one such mechanism, and depends in part on the downregulation of calcium-dependent SK-type K+ channels, which contribute to a medium-slow afterhyperpolarization (AHP) after spike bursts, regulating membrane excitability. In the hippocampus, intrinsic plasticity plays a role in trace eye-blink conditioning; however, corresponding excitability changes in the cerebellum in associative learning, such as in trace or delay eye-blink conditioning, are less well studied. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained from Purkinje cells in cerebellar slices prepared from male mice ∼48 h after they learned a delay eye-blink conditioning task. Over a period of repeated training sessions, mice received either paired trials of a tone coterminating with a periorbital shock (conditioning) or trials in which these stimuli were randomly presented in an unpaired manner (pseudoconditioning). Purkinje cells from conditioned mice show a significantly reduced AHP after trains of parallel fiber stimuli and after climbing fiber evoked complex spikes. The number of spikelets in the complex spike waveform is increased after conditioning. Moreover, we find that SK-dependent intrinsic plasticity is occluded in conditioned, but not pseudoconditioned mice. These findings show that excitability is enhanced in Purkinje cells after delay eye-blink conditioning, and point toward a downregulation of SK channels as a potential underlying mechanism. The observation that this learning effect lasts at least up to 2 d after training shows that intrinsic plasticity regulates excitability in the long term.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Plasticity of membrane excitability (“intrinsic plasticity”) has been observed in invertebrate and vertebrate neurons, coinduced with synaptic plasticity or in isolation. Although the cellular phenomenon per se is well established, it remains unclear what role intrinsic plasticity plays in learning and if it even persists long enough to serve functions in engram physiology beyond aiding synaptic plasticity. Here, we demonstrate that cerebellar Purkinje cells upregulate excitability in delay eye-blink conditioning, a form of motor learning. This plasticity is observed 48 h after training and alters synaptically evoked spike firing and integrative properties of these neurons. These findings show that intrinsic plasticity enhances the spike firing output of Purkinje cells and persists over the course of days.

Introduction

Classically, cerebellar motor learning has been thought to rely on changes in synaptic strength, specifically at synapses between parallel fibers (PFs) and Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex (for review, see Jörntell and Hansel, 2006). It has been suggested that cerebellar learning may also involve other nonsynaptic ('intrinsic') plasticity mechanisms (Titley et al., 2017). This hypothesis is supported by the finding that the membrane excitability of Purkinje cells is enhanced after delay eye-blink conditioning in lobule HVI of conditioned rabbits (Schreurs et al., 1997, 1998). However, it has not been determined whether such an effect alters Purkinje cell responses to synaptic input patterns, and whether the training-induced excitability change occludes tetanization-evoked intrinsic plasticity. Both aspects are critical to be able to link these ex-vivo findings to the growing literature on cellular mechanisms of Purkinje cell intrinsic plasticity, and to be able to assess its consequences for Purkinje cell and cerebellar function.

In Purkinje cells, a form of intrinsic plasticity that is mediated by SK2 channel downregulation (Purkinje cells only express the SK2 isoform; Cingolani et al., 2002) results in enhanced excitability, enhanced spine calcium signaling, and a lower probability for subsequent LTP induction (Belmeguenai et al., 2010; Hosy et al., 2011; note that in Purkinje cells the calcium threshold for LTD is higher than that for LTP: Coesmans et al., 2004; Piochon et al., 2016). SK channels contribute to an afterhyperpolarization (AHP) after bursts of action potentials and are involved in the regulation of spike firing frequency in some neurons (Stocker et al., 1999; Pedarzani et al., 2001). In the cerebellum, SK2 channels are known to be involved in the medium-slow AHP mediating the complex spike pause in Purkinje cells (Kakizawa et al., 2007). Indeed, intrinsic plasticity reduces the duration of complex spike pauses in Purkinje cells and this type of plasticity depends on SK channel modulation (Grasselli et al., 2016).

In the hippocampus, SK2 is known to be important for synaptic plasticity and learning. SK2 overexpression reduced long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices, and severely impaired hippocampal-dependent learning in mice (Hammond et al., 2006). During trace eye-blink conditioning in rats, an SK channel activator injected into dorsal hippocampus reduced the excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons by increasing the medium AHP, and impaired learning (McKay et al., 2012, 2013). Here, we ask whether intrinsic excitability is changed in a cerebellar motor learning task (delay eye-blink conditioning), and whether the altered excitability parameters point toward an involvement of SK channel modulation. We find that 48 h after delay eye-blink conditioning, the Purkinje cell AHP after PF bursts or complex spikes is reduced, accompanied by an increase in the number of spikelets within the complex spike waveform. Intrinsic plasticity triggered by repeated injection of depolarizing current pulses (Belmeguenai et al., 2010) is occluded after eye-blink conditioning.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committees of both Northwestern University and the University of Chicago. Experiments were performed using 5- to 8-week-old male mice (C57BL/6J) obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. During this study, 20 mice were exposed to a conditioning protocol and 28 mice were exposed to a pseudoconditioning protocol (see below). In addition, we included data obtained from 13 naive mice.

Surgery.

Briefly, animals were anesthetized with 3–4% vaporized isoflurane mixed with oxygen at a flow rate of 1–2 L/min, with buprenorphine (0.05–2 mg/kg) given subcutaneously as an analgesic. Mice were placed in a stereotaxic device and a midline incision was made along the scalp. The skin was retracted laterally and the periosteum was scraped away. Two small screws (one in front of Bregma and one in front of Lambda) were implanted into the skull left of the midline. A ground wire of a headpiece containing five wires (one ground, two shock-delivering, and two EMG recording wires) was wrapped around the screws in a figure eight pattern. A thin layer of adhesive cement was placed on the skull, the screws, and the wire. The skin around the right eye was retracted to reveal the muscle lateral to the eye. Two shock-delivering wires were placed under the skin caudal to the right eye and two EMG recording wires were placed on the musculus orbicularis behind the eyelid. The base of the wires was stabilized with another layer of cement. The headpiece was stabilized with dental cement. The animal was allowed to recover on a warmed heating pad before the animal was placed back in its home cage. Mice were allowed to recover 1 week after the surgery before starting eye-blink conditioning.

Delay eye-blink conditioning.

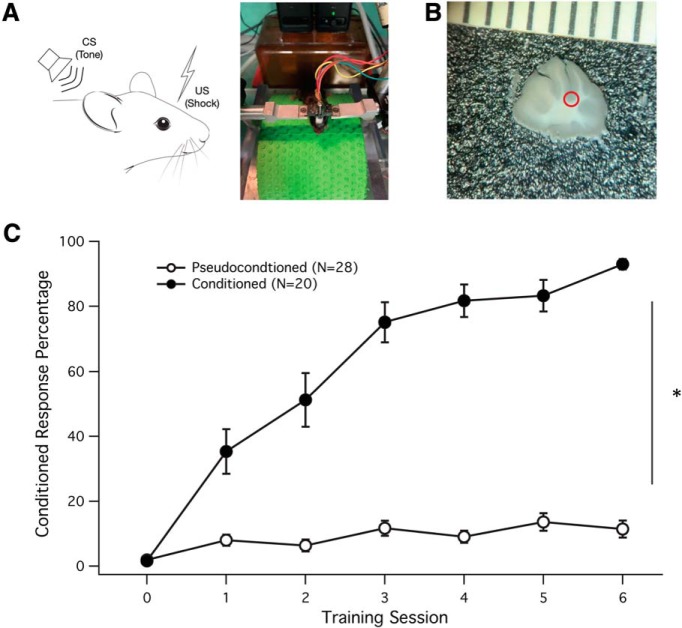

Animals were randomly assigned to either a conditioned group or a pseudoconditioned group. The training apparatus included a cylindrical treadmill inside a sound attenuating training chamber (IAC Acoustics). Mice were head fixed and allowed to run freely on the cylindrical treadmill (Lin et al., 2016; Fig. 1A). Mice were allowed to habituate to the chamber and cylindrical treadmill during two separate sessions the day before training. During each habituation session, the mice were placed on the cylindrical treadmill for the same duration as one training session, although no stimuli were presented. Training began the day after habituation. The mice were trained for two sessions a day for 3 d, with a 2 h interval between training sessions. Conditioned mice were given the delay eye-blink conditioning paradigm, which consisted of a 75 dB tone (350 ms, 2 kHz) conditioned stimulus (CS) paired with a 100 ms unconditioned stimulus (US) consisting of 6 sets of biphasic shocks (120 Hz; 1 ms/pulse) to the periorbital region using a biphasic stimulus isolator (WPI model A385). The US intensity was adjusted for each mouse to elicit a reliable blink (0.3–2 mA). The CS overlapped with and coterminated with the US. Each conditioning session consisted of 30 paired CS-US trials with a random 30–60 s intertrial interval. The pseudoconditioned mice were presented with 30 unpaired CS trials and 30 unpaired US trials in pseudorandomized order with a 15–30 s intertrial interval.

Figure 1.

Delay eye-blink conditioning generates learned behavior. A, Experimental setup. Left, Diagram of the CS (tone) and US (shock) stimuli applied to the test animal. Right, Original setup showing the mouse walking on a treadmill. B, Slice preparation illustrating the typical area at the base of the primary fissure from which patch-clamp recordings were obtained (red circle). The scale shows 1 mm units. C, Learning curve for conditioned (black dots; n = 20) and pseudoconditioned mice (white dots; n = 28). Conditioned animals were successfully able to learn and generate a CR (eye closure) at a high percentage by the end of the sixth learning session. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significance of p < 0.05.

EMG signals were amplified and filtered through 100 to 5 kHz low-/high-pass filter. The signals were rectified and integrated with a time constant of 10 ms. Baseline EMG activity was defined as the average activity 250 ms before CS onset. Conditioned responses were identified as having EMG activity 4 SDs above the baseline, present at least 20 ms before US onset. The electrophysiological experiments described below were performed with the experimenter blind to the training condition of each mouse.

Slice preparation.

Within ∼48 h of the final delay eye-blink conditioning training session, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and immediately decapitated. The cerebellum was removed and the right paravermis/hemisphere isolated in artificial CSF (ACSF) cooled to 1−4°C, and containing the following (in mm): 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.25 Na2HPO4, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 D-glucose, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Parasagittal slices of the right hemisphere and paravermis (200 μm) containing lobule HVI were prepared with a Leica VT-1000S vibratome, then incubated for at least 1 h at room temperature in oxygenated ACSF (Fig. 1B).

Somatic whole-cell patch-clamp recordings.

Slices were continuously perfused with ACSF containing picrotoxin (100 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) to block GABAA receptors (to selectively activate glutamatergic transmission in the experiments on synaptically driven AHPs), and held at near physiological temperature (32−34°C) over the course of the experiments. Slices were visualized using an ×40 objective mounted on either a Zeiss Examiner A1 microscope or a Zeiss Axioskop 2 FS plus microscope. Patch-clamp recordings were made from Purkinje cells located at the base of the primary fissure using an EPC-10 amplifier (HEKA Electronics). Currents were filtered at 3 kHz, sampled at 20 kHz, and acquired using Patchmaster software (HEKA Electronics). The access resistance was compensated (70–80%) in current-clamp mode. In most experiments hyperpolarizing bias currents were applied to hold the membrane potential around −70 mV. Patch pipettes (2–6 MΩ) were filled with internal solution containing the following (in mm): 120 K-gluconate, 9 KCl, 10 KOH, 3.48 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 4 NaCl, 4 Na2ATP, 0.4 Na3GTP, and 17.5 sucrose, with the pH adjusted to 7.25–7.35.

Spontaneous activity was determined by measuring cell firing in current-clamp mode over 1 s sweeps; Purkinje cells that did not generate action potentials with 0 pA injected current (no bias current) were excluded from the experiments. Evoked activity was measured by holding Purkinje cells at −70 mV in current-clamp mode and applying a 500 ms depolarization step that gradually increased in 50 pA steps. Parallel fibers were stimulated by placing a glass pipette filled with ACSF in the molecular layer around the distal dendrite of the Purkinje cell while held at −70 mV. Parallel fiber inputs were stimulated 10 times at 100 Hz. The climbing fiber input was stimulated using a glass pipette that was placed in the granule cell layer below the targeted Purkinje cell.

Intrinsic plasticity was monitored during the test periods by injecting a 500 ms depolarizing current (300–800 pA) to evoke 10–15 action potentials. The input resistance was monitored throughout the experiments by applying hyperpolarizing current steps (−100 pA) at the end of each sweep. During tetanization, depolarizing currents (100 ms) were injected at 5 Hz for 8 s. Intrinsic plasticity recordings were excluded if the input resistance (Ri) or holding potential (Vh) changed by ≥15% over the course of the baseline.

Data analysis.

CS and US were delivered and EMG signals were collected using custom software written for LabVIEW (National Instruments). Cellular data were analyzed using Excel (Microsoft), Igor (Wave-metrics), and Statistica (Tibco). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test (between groups), paired Student's t test (within subjects), and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA tests as appropriate. Statistical comparisons were based on the number of cells recorded from. The number of mice used is indicated for each parameter tested.

Results

Mice successfully learned the associative conditioning task

Eye-blink conditioning consisted of six consecutive sessions in which mice learned to associate an auditory tone (CS) with a periorbital shock to the eyelid (US). Over the six training sessions, conditioned mice successfully learned to associate the two stimuli (threshold criterion >80% conditioned response [CR]) when the CS preceded and coterminated with the US. Pseudoconditioned mice received unpaired CS and US trials, serving as controls for the presentation of the stimuli (<20% CR during CS only trials). Figure 1C shows the gradual acquisition of the CR in the conditioned mice (black dots, 92.97 ± 1.61% CR, n = 20), compared with pseudoconditioned mice, who maintain chance levels of CR activity (open dots, 11.44 ± 2.61% CR, n = 28). This difference in CR activity was statistically significant (two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA, F(6,168) = 21.56; p = 0.004).

Spontaneous and evoked spiking activity were not affected by associative learning

To evaluate potential cellular differences in cerebellar Purkinje cells caused by conditioning, conditioned and pseudoconditioned mice were killed ∼48 h after the last training trial. We examined Purkinje cells by whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology deep in the primary fissure near cerebellar lobules V/HVI. The location is approximate, but was selected based on accounts suggesting that essential conditioned eyeblink control regions are found here in mice (Heiney et al., 2014), consistent with microzonal mapping in rabbits (Mostofi et al., 2010; Steinmetz and Freeman, 2014). The experimenters were blind to the condition of the mouse during the time of the experiment and analysis. To ensure that the Purkinje cells examined were healthy and displayed normal physiological properties, only cells that produced spontaneous action potentials without bias current injection were analyzed.

To determine whether delay eye-blink conditioning increased spike firing of Purkinje cells, we measured both spontaneous and evoked firing under current-clamp conditions. The eye-blink conditioning task had no effect on the spontaneous firing frequency of cells. Figure 2A illustrates example traces from two Purkinje cells firing spontaneously. The spontaneous firing frequency recorded from Purkinje cells in pseudoconditioned mice was 80.8 ± 5.7 spikes/s (n = 37; n = 24 mice). This was not significantly different from Purkinje cells from conditioned mice with a spontaneous firing rate of 80.9 ± 6.0 spikes/s (n = 27; n = 20 mice; Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.764; Fig. 2B).

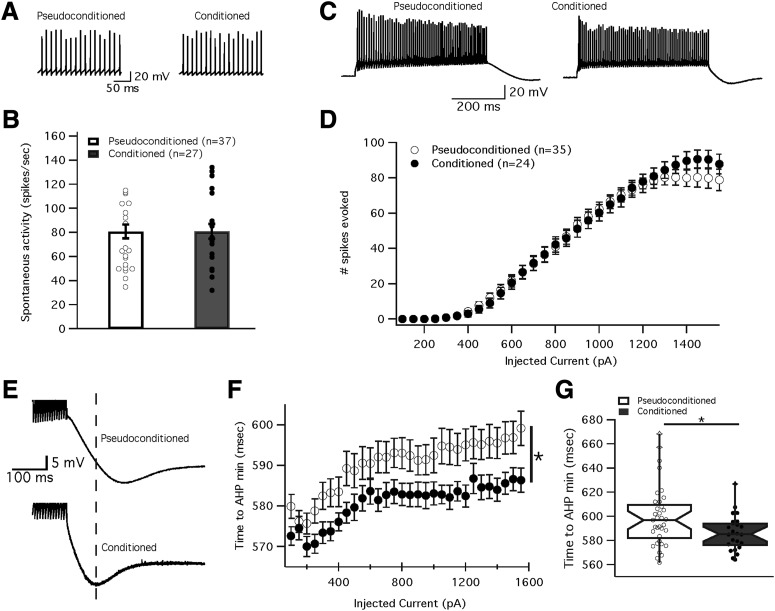

Figure 2.

Delay eye-blink conditioning has no effect on spontaneous or evoked spike firing of cerebellar Purkinje cells. A, Example traces depicting spontaneous firing from Purkinje cells in a pseudoconditioned (left) and a conditioned mouse (right). B, Spike count of action potentials per second measured from spontaneously firing cells (with no injected currents) from conditioned and pseudoconditioned mice. Dots represent individual cells, whereas bars represent the mean ± SEM C. Example traces depicting evoked firing from cells in D with 1550 pA current injected. D, Mean evoked firing (number of spikes) from conditioned (black) and pseudoconditioned cells (white) over a broad range of injected currents. E, Example traces showing differences in the AHP between pseudoconditioned (top) and conditioned mice (bottom). Dashed line represents the time of the minimum for the example trace obtained from a conditioned mouse. F, Timing of the AHP peak amplitude as a function of injected current for conditioned (black) and pseudoconditioned (white) mice. G, The mean time to the AHP minimum when the injected current is 1550 pA in conditioned and pseudoconditioned mice (taken from F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significance of p < 0.05.

To further analyze the excitability of Purkinje cells we looked at firing evoked by injection of increasing depolarization steps. Under current-clamp conditions Purkinje cells were held at a potential of around −70 mV, while depolarizing currents (500 ms, 100–1550 pA) were injected into the cell in 50 pA steps to induce firing. We analyzed the curves of spikes evoked plotted against injected current. Figure 2D shows that the curves of the conditioned and pseudoconditioned cells appeared very similar and were not significantly different (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, F(26,832) = 0.81, p = 0.74). When 1550 pA of current was injected into the cells, no differences were found between the number of spikes evoked from cells of conditioned (87.8 ± 5.6 spikes; n = 24; n = 20 mice) or pseudoconditioned mice (78.8 ± 6.1 spikes; n = 35; n = 24 mice; Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.38; Fig. 2D). Together, these results suggest that delay eye-blink conditioning did not affect spontaneous or depolarization-evoked spike firing.

Decreased amplitudes of AHPs in conditioned mice

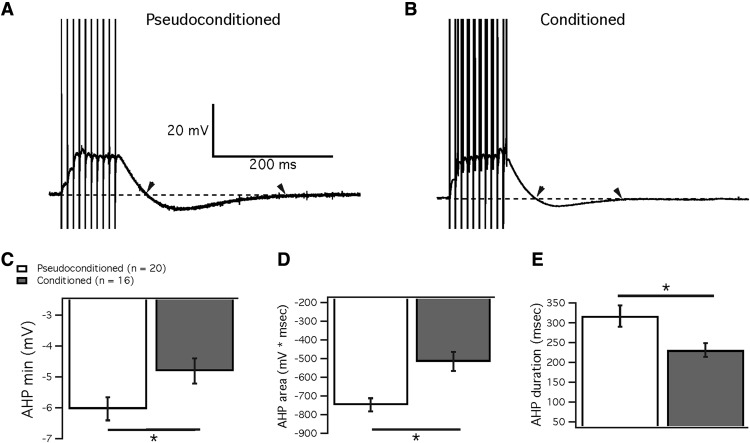

As SK2 channels have been shown to underlie the medium AHP in Purkinje cells (Kakizawa et al., 2007; Grasselli et al., 2016), we looked at the AHP after evoked activity. Although there was no difference in evoked firing rate, the time to the minimum AHP value was significantly shorter at 1550 pA injected current in cells from conditioned animals (586.4 ± 3.0 ms; n = 24; n = 14 mice) relative to pseudoconditioned mice (599.2 ± 4.2 ms; n = 35; n = 18 mice; Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.02; Fig. 2E–G). Additionally, the AHP was reduced in conditioned mice after a burst of 10 parallel fiber stimuli at 100 Hz. Figure 3 shows example traces for Purkinje cells from a pseudoconditioned (Fig. 3A) and a conditioned animal (Fig. 3B) after a burst of parallel fiber stimulation. Cells from the conditioned mice were found to have a significantly reduced AHP compared with cells from pseudoconditioned animals. The average minimum (peak) amplitude of the AHP was significantly lower in cells from conditioned mice (−4.8 ± 0.4 mV; n = 16; n = 14 mice) than in cells from pseudoconditioned mice (−6.0 ± 0.4 mV; n = 20; n = 18 mice; Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.03; Fig. 3C). Furthermore, in the same recordings we found a significant reduction in the total AHP area (conditioned: −416.0 ± 51.1 ms*mV; pseudoconditioned: −747.6 ± 35.7 ms*mV; Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.0006; Fig. 3D) as well as a reduction in AHP duration (conditioned: 231.5 ± 17.5 ms; pseudoconditioned: 317.2 ± 26.6 ms; Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.005; Fig. 3E). Therefore, Purkinje cells in mice that received delay eye-blink conditioning showed a significantly reduced AHP compared with Purkinje cells from pseudoconditioned control mice, which is compatible with a downregulation of SK2 channels during eye-blink conditioning. Mice that received no training (naive mice) did not acquire CRs. Their spontaneous blink rate during a habituation session analyzed as if conditioning was done was 2.70 ± 0.76% (n = 13). Neurons from those mice did not show changes in the AHP peak amplitude (−6.8 ± 0.4 mV; n = 16; n = 13 mice), the total AHP area (−731.59 ± 55.11 ms*mV; n = 16; n = 13 mice) or the AHP duration (303.5 ± 30.3 ms; n = 16; n = 13 mice). None of these parameters differed between the naive and the pseudoconditioned control groups (Mann–Whitney U test, AHP peak amplitude: p = 0.816; AHP area: p = 0.594; AHP duration: p = 0.594). Having established that pseudoconditioned mice show no alteration in excitability-related AHP parameters compared with naive controls, all further experiments were restricted to the comparison between conditioned and pseudoconditioned mice.

Figure 3.

Eye-blink conditioning reduced the AHP after parallel fiber burst stimulation. A, B, Example traces of the response to 10 parallel fiber stimuli at 100 Hz from cells from a pseudoconditioned mouse (A) and a conditioned mouse (B). Dashed line indicates the baseline potential at −70 mV. Arrowheads indicate the start and finish of the AHP. C–E, Measures of the AHP after the parallel fiber burst in cells from conditioned (gray) and pseudoconditioned mice (white). C, Minimum amplitude of AHP. D, Area of AHP (measured as area between curve and baseline). E, Duration of AHP. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significance of p < 0.05.

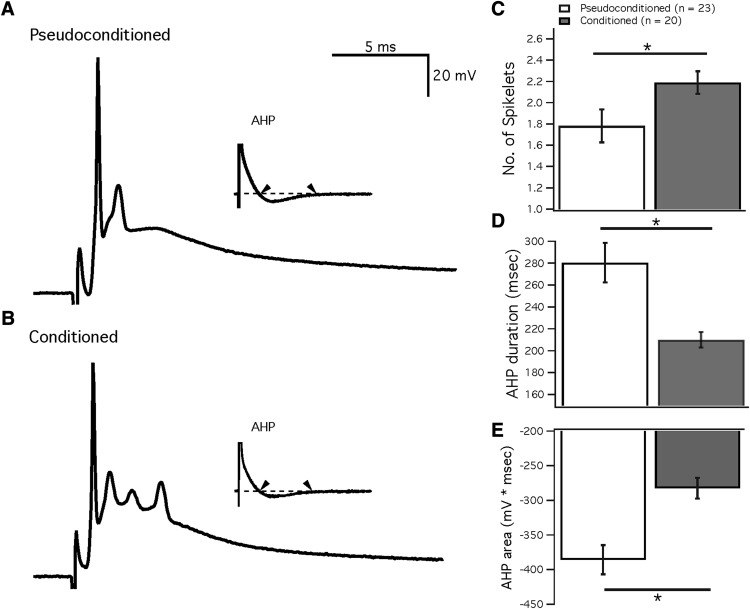

Similar to the change in AHPs after parallel fiber bursts, we observed a reduction in the duration of AHPs after complex spikes in Purkinje cells from conditioned mice (210.0 ± 9.2 ms; n = 20; n = 17 mice) compared with those from pseudoconditioned mice (280.5 ± 18.1 ms; n = 23; n = 17 mice; Mann–Whitney U test; p = 0.0019; Fig. 4D) as well as a reduction in the AHP area (conditioned: −282.4 ± 15.0 ms*mV; pseudoconditioned: −385.6 ± 21.1 ms*mV; Mann–Whitney U test; p = 0.0004; Fig. 4E). However, the peak amplitude of these AHPs was not significantly reduced after conditioning (conditioned: −2.88 ± 0.18 mV; pseudoconditioned: −3.19 ± 0.18 mV; Mann–Whitney U test; p = 0.203). In addition, we observed an increased number of spikelets in the complex spike waveform after conditioning (2.19 ± 0.11; n = 20; n = 17 mice; pseudoconditioned: 1.78 ± 0.15; n = 23; n = 17 mice; Mann–Whitney U test; p = 0.042; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Eye-blink conditioning alters the complex spike waveform. A, B, Example traces of complex spikes recorded from Purkinje cells in pseudoconditioned (A) and conditioned mice (B). The insets show the entire complex spike waveform expanded to include the AHP. C, Bar graph showing the number of spikelets after the initial spike. D, E, Measures of the AHP from pseudoconditioned (white) and conditioned mice (gray). D, Duration of AHP. E, Area of the AHP. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significance of p < 0.05.

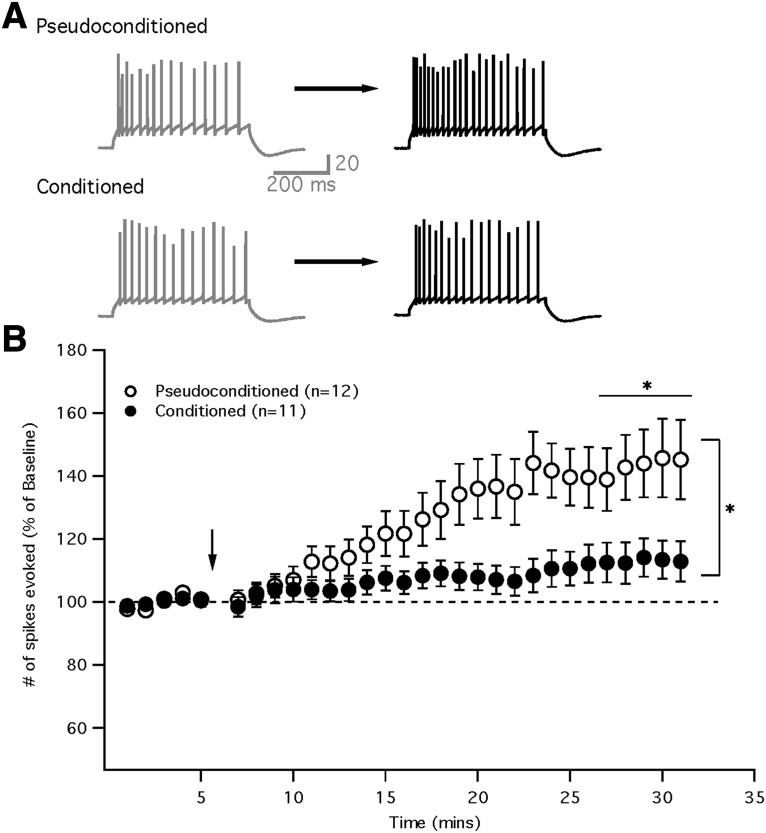

Intrinsic plasticity is occluded in cells from conditioned mice

To further test the involvement of SK2 in eye-blink conditioning, we repeatedly depolarized (5 Hz, 8 s) the Purkinje cells to induce intrinsic plasticity (Belmeguenai et al., 2010). Purkinje cells from pseudoconditioned mice showed a significant increase in the number of spikes evoked after the intrinsic potentiation protocol compared with baseline (paired Student's t test, p = 0.002; Fig. 5). In contrast, Purkinje cells from conditioned mice failed to show increases in excitability that were significantly different from baseline (paired Student's t test, p = 0.063). When comparing the difference between these groups at 21–25 min after tetanization, Purkinje cells from the pseudoconditioned group showed significantly larger excitability changes compared with cells from conditioned mice (pseudoconditioned: 143.3 ± 11.2%; n = 12; n = 10 mice; conditioned: 113.1 ± 6.3%; n = 11; n = 10 mice; Mann–Whitney U test, p = 9.99 × 10−7). Therefore, Purkinje cells from conditioned mice failed to show significant intrinsic potentiation after tetanization, whereas those from pseudoconditioned mice were able to upregulate excitability, suggesting that SK2-dependent intrinsic plasticity was occluded after delay eye-blink conditioning.

Figure 5.

Intrinsic plasticity is occluded in Purkinje cells from conditioned animals. A, Example traces of evoked activity during the baseline (left) and after tetanization (right) in cells from pseudoconditoned (top) and conditioned (bottom) mice. B, Time graph showing intrinsic potentiation (increase in evoked spiking as percentage of baseline) in pseudoconditioned cells (white) after tetanization (arrow), but not in conditioned cells (black). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significance of p < 0.05.

Absence of correlations between CR percentage and plasticity effect size

In conditioned mice, none of the excitability parameters tested showed a significant correlation between CR percentage and effect size (pooled when multiple recordings were obtained from the same mouse; spontaneous spike frequency: ρ = 0.068; p = 0.78; PF burst AHP area: ρ = 0.025; p = 0.93; CF AHP area: ρ = 0.02; p = 0.94; number of spikelets within the complex spike waveform: ρ=-0.19; p = 0.46; intrinsic plasticity amplitude: ρ = 0.71; p = 0.06; Spearman's rank-correlation test). Thus, the amplitude of excitability changes in individual Purkinje cells is not a good predictor of the behavioral performance. This effect is likely due to a large range and variability of effect sizes across groups of Purkinje cells within each mouse. Another factor might be that the CR percentage is additionally controlled by neurons other than Purkinje cells in the eye-blink microzone.

Discussion

AHP is reduced in Purkinje cells after delay eye-blink conditioning

It has previously been reported that the AHP amplitude is reduced in rabbits after trace eye-blink conditioning tasks in both CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons (Moyer et al., 1996; Thompson et al., 1996). Similarly, Schreurs and colleagues found a reduction in the AHP in Purkinje cells from conditioned rabbits compared with cells from pseudoconditioned animals in a delay eye-blink conditioning task. In their study, they found that Purkinje cells in area HVI from conditioned animals showed a decrease in dendritic spike threshold as well as a reduction in the AHP after depolarization steps that persisted even 1 month after the final training session (Schreurs et al., 1997, 1998). Here, we similarly found that after a burst of parallel fiber stimulation, Purkinje cells in mice that were conditioned showed a significantly reduced AHP minimum amplitude, AHP duration, as well as a reduced AHP area (Fig. 3). We also found alterations in the AHP after depolarizing current pulses (Fig. 2) as well as the AHP after complex spikes (Fig. 4) in conditioned mice, indicating that regardless of the physiological event driving calcium influx and, ultimately the AHP, training affects the kinetics and/or amplitude of AHPs. The AHP is known to be involved in spike excitability, and in Purkinje cells it is known to be partially mediated by SK2 conductances, suggesting that SK channels might be downregulated during a delay eye-blink conditioning task. In a previous study, learning-related changes in the membrane excitability of Purkinje cells were attributed to changes in A-type K channels as the effect on dendritic spike threshold and the AHP could be mimicked by bath application of the IA antagonist 4-AP (Schreurs et al., 1998). In a previous study, 4-AP did not occlude intrinsic plasticity (spike count measure) triggered by repeated injection of depolarizing current pulses (Belmeguenai et al., 2010). It is possible that this difference can be explained by the use of dendritic (Schreurs et al., 1998) versus somatic recordings (Belmeguenai et al., 2010). Our own dendritic recordings demonstrated an involvement of SK2 channels in intrinsic plasticity measured in Purkinje cell dendrites as this phenomenon was absent in SK2 knock-out mice (Ohtsuki et al., 2012). However, we did not test for a role of A-type K channels, and thus it is entirely possible that these, and possibly other, K channels play a role in dendritic Purkinje cell intrinsic plasticity as well.

Our recordings were performed from Purkinje cells located at the base of the primary fissure, at the depths of lobule HVI. This area has been identified as an eye-blink-related microzone in mice (Heiney et al., 2014), and largely corresponds to the eyeblink microzone determined in rabbits, which also is located to the depths of lobule HVI (Mostofi et al., 2010). The observation of similar excitability changes in Purkinje cells located in more dorsal parts of lobule HVI (Schreurs et al., 1998) suggests that enhanced excitability is not restricted to Purkinje cells from conditioned animals in the core of the eye-blink microzone itself, but also occurs in Purkinje cells from close-by zones of lobule HVI that might process CS- and US-related information in the context of associative learning. The existence of a wider zone within lobule HVI that shows learning-related cellular alterations is also suggested by the observation of increases in activity levels of protein kinase C (PKC) throughout lobule HVI, and particularly in the dorsal parts of this lobule (Freeman et al., 1998; for review, see Schreurs, 2019). A related caveat certainly is that we have no independent confirmation that the Purkinje cells that we recorded from are essential contributors to the learned eyelid closure. The confidence that this relation is true arises from the fact that the eyelid microzone that the targeted Purkinje cells are located in is rather small and the findings that we made were consistent across this population of neurons.

Alterations in the complex spike waveform after delay eye-blink conditioning

The complex spike waveform was altered after conditioning in two ways: (1) the AHP duration and area were reduced and (2) the number of spikelets was enhanced. The latter finding supports the notion that membrane excitability is indeed enhanced in conditioned Purkinje cells. This is critical, as the phenomenon of AHP reduction itself may also result from a reduction in depolarization-evoked calcium influx, i.e., a reduction in excitability. The interpretation that instead excitability is enhanced is further supported by the additional observation of intrinsic plasticity occlusion. The finding that the spikelet number is increased is also relevant in the context of the supposed all-or-none character of climbing fiber responses (Eccles et al., 1966; Llinás and Sugimori, 1980). Previous studies have reported that the complex spike waveform can change as a result of climbing fiber plasticity (Hansel and Linden, 2000) or neuromodulation in vitro (Carey and Regehr, 2009), and also depending on features of complex spike-driving input in vivo (Najafi and Medina, 2013; Najafi et al., 2014; see also Zang et al., 2018; Gaffield et al., 2019). Here, we show for the first time that such a deviation from the classic all-or-none model can be observed after behavioral learning.

Intrinsic potentiation is occluded after delay eye-blink conditioning

To further test for the involvement of SK channels, we tetanized cells using an intrinsic plasticity protocol. In Purkinje cells, this form of intrinsic plasticity is known to depend on SK2 channels, as SK2 is the only isoform expressed in Purkinje cells. Intrinsic potentiation is blocked by the SK inhibitor apamin (Ohtsuki et al., 2012) and is shown to be absent in SK2 knock-out mice (Grasselli et al., 2016). Here, we demonstrate that conditioned mice failed to increase their spike firing after an intrinsic potentiation protocol, whereas pseudoconditioned cells were able to upregulate evoked spike firing (Fig. 5). This suggests that intrinsic plasticity was occluded in the conditioned mice, suggesting that this nonsynaptic form of plasticity is involved in learning (Titley et al., 2017).

Purkinje cell intrinsic plasticity is not merely a short-term phenomenon

Here, we demonstrate the cellular consequences of conditioning ex vivo 48 h after learning has ended, although the maximal duration of the described excitability changes was not tested. In the first report on enhanced Purkinje cell excitability in eye-blink conditioning, the authors stated that these cell physiological changes were found as late as 1 month after conditioning (Schreurs et al., 1998). This observation differs from more transient changes in excitability found in other brain areas, such as in CA1 and CA3 hippocampus in trace eye-blink conditioning (return to baseline levels within 7 d; Moyer et al., 1996; Thompson et al., 1996) and dentate gyrus in fear conditioning (return to baseline within 2 h; Pignatelli et al., 2019). The latter finding is in line with the observation that chemogenetic or optogenetic silencing of dentate gyrus neurons 5 min, but not 24 h, after training prevents allocation of these neurons to a memory engram (Park et al., 2016). Our study used ex vivo recordings ∼48 h after conditioning. The observation of enhanced excitability within this time frame supports the claim that intrinsic plasticity—at least in cerebellar Purkinje cells—is more than a transient phenomenon that affects engram formation merely within hours. To what degree intrinsic plasticity constitutes a component of persistent engrams remains to be investigated, in Purkinje cells and other types of neurons.

Potential functions of enhanced excitability in eye-blink conditioning

A hallmark of conditioned Purkinje cells is the suppression of simple spike firing after presentation of the CS (Halverson et al., 2015; Ohmae and Medina, 2015; ten Brinke et al., 2015, 2017; Jirenhed and Hesslow, 2016). If this is true, what then is the function of enhanced membrane excitability? A first hint is provided by our recent observation, using somato-dendritic double-patch recordings from Purkinje cells in rat cerebellar slices, that the spike output pattern generated by the neurons does not depend on the amplitude of dendritic EPSPs, but instead on SK2 channel activity and the AHP amplitude (Ohtsuki and Hansel, 2018). This finding suggests that an enhanced membrane excitability ensures responsiveness of Purkinje cells to salient input patterns despite the overall reduction in spike firing that is driven by enhanced inhibition (ten Brinke et al., 2015). Along the same line of argumentation, enhanced excitability may also be crucial to enable Purkinje cells to terminate memory traces and initiate new ones (Khilkevich et al., 2018). A related scenario involves CF-evoked complex spikes. It has been reported that during conditioning complex spikes emerge in response to CS application (Ohmae and Medina, 2015; ten Brinke et al., 2015). The relationship of these CS-complex spikes to the learned eyelid closure is currently not known, but the enhanced number of spikelets in the complex spike waveform that we report here will certainly strengthen the impact of these additional complex spikes. Finally, it is possible that enhanced excitability is a signature of all Purkinje cells activated during the conditioning task—whether they are directly involved in driving eyelid closure or not—with the consequence that they reach a high excitability state (see Ohtsuki and Hansel, 2018) that facilitates their participation in their respective functional neural ensembles (Titley et al., 2017). In the subgroup of eyelid closure-driving Purkinje cells, this excitability enhancement may increase the net effect of transient simple spike suppression, providing contrast enhancement for the ensuing pause. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive and have in common that intrinsic plasticity marks Purkinje cells that play a role in learning-related circuit adaptations.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-062271 to C.H. and J.F.D. and National Institute on Aging Grant R37 AG008796 to J.F.D.). We like to thank members of the Hansel and Disterhoft laboratories for many helpful discussions.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Belmeguenai A, Hosy E, Bengtsson F, Pedroarena CM, Piochon C, Teuling E, He Q, Ohtsuki G, De Jeu MT, Elgersma Y, De Zeeuw CI, Jörntell H, Hansel C (2010) Intrinsic plasticity complements long-term potentiation in parallel fiber input gain control in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci 30:13630–13643. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3226-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MR, Regehr WG (2009) Noradrenergic control of associative synaptic plasticity by selective modulation of instructive signals. Neuron 62:112–122. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani LA, Gymnopoulos M, Boccaccio A, Stocker M, Pedarzani P (2002) Developmental regulation of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel expression and function in rat Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 22:4456–4467. 10.1523/jneurosci.22-11-04456.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coesmans M, Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C (2004) Bidirectional parallel fiber plasticity in the cerebellum under climbing fiber control. Neuron 44:691–700. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Llinás R, Sasaki K (1966) The excitatory synaptic actions of climbing fibres on the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. J Physiol 182:268–296. 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JH Jr, Scharenberg AM, Olds JL, Schreurs BG (1998) Classical conditioning increases membrane-bound protein kinase C in rabbit cerebellum. Neuroreport 9:2669–2673. 10.1097/00001756-199808030-00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffield MA, Bonnan A, Christie JM (2019) Conversion of graded presynaptic climbing fiber activity into graded postsynaptic Ca2+ signals by Purkinje cell dendrites. Neuron 102:762–769.e4. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasselli G, He Q, Wan V, Adelman JP, Ohtsuki G, Hansel C (2016) Activity-dependent plasticity of spike pauses in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Cell Rep 14:2546–2553. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halverson HE, Khilkevich A, Mauk MD (2015) Relating cerebellar Purkinje cell activity to the timing and amplitude of conditioned eyelid responses. J Neurosci 35:7813–7832. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3663-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond RS, Bond CT, Strassmaier T, Ngo-Anh TJ, Adelman JP, Maylie J, Stackman RW (2006) Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel type 2 (SK2) modulates hippocampal learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci 26:1844–1853. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4106-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel C, Linden DJ (2000) Long-term depression of the cerebellar climbing fiber-Purkinje neuron synapse. Neuron 26:473–482. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81179-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiney SA, Kim J, Augustine GJ, Medina JF (2014) Precise control of movement kinematics by optogenetic inhibition of Purkinje cell activity. J Neurosci 34:2321–2330. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4547-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosy E, Piochon C, Teuling E, Rinaldo L, Hansel C (2011) SK2 channel expression and function in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol 589:3433–3440. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.205823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirenhed DA, Hesslow G (2016) Are Purkinje cell pauses drivers of classically conditioned blink responses? Cerebellum 15:526–534. 10.1007/s12311-015-0722-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörntell H, Hansel C (2006) Synaptic memories upside down: bidirectional plasticity at cerebellar parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Neuron 52:227–238. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakizawa S, Kishimoto Y, Hashimoto K, Miyazaki T, Furutani K, Shimizu H, Fukaya M, Nishi M, Sakagami H, Ikeda A, Kondo H, Kano M, Watanabe M, Iino M, Takeshima H (2007) Junctophilin-mediated channel crosstalk essential for cerebellar synaptic plasticity. EMBO J 26:1924–1933. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khilkevich A, Zambrano J, Richards MM, Mauk MD (2018) Cerebellar implementation of movement sequences through feedback. eLife 7:e37443. 10.7554/eLife.37443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Disterhoft J, Weiss C (2016) Whisker-signaled eyeblink classical conditioning in head-fixed mice. J Vis Exp 109:e53310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Sugimori M (1980) Electrophysiological properties of in vitro Purkinje cell somata in mammalian cerebellar slices. J Physiol 305:171–195. 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay BM, Oh MM, Galvez R, Burgdorf J, Kroes RA, Weiss C, Adelman JP, Moskal JR, Disterhoft JF (2012) Increasing SK2 channel activity impairs associative learning. J Neurophysiol 108:863–870. 10.1152/jn.00025.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay BM, Oh MM, Disterhoft JF (2013) Learning increases intrinsic excitability of hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 33:5499–5506. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4068-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofi A, Holtzman T, Grout AS, Yeo CH, Edgley SA (2010) Electrophysiological localization of eyeblink-related microzones in rabbit cerebellar cortex. J Neurosci 30:8920–8934. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6117-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer JR Jr, Thompson LT, Disterhoft JF (1996) Trace eye-blink conditioning increases CA1 excitability in a transient and learning-specific manner. J Neurosci 16:5536–5546. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05536.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi F, Medina JF (2013) Beyond “all-or-nothing” climbing fibers: graded representation of teaching signals in Purkinje cells. Front Neural Circuits 7:115. 10.3389/fncir.2013.00115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi F, Giovannucci A, Wang SS, Medina JF (2014) Sensory-driven enhancement of calcium signals in individual Purkinje cell dendrites of awake mice. Cell Rep 6:792–798. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmae S, Medina JF (2015) Climbing fibers encode a temporal-difference prediction error during cerebellar learning in mice. Nat Neurosci 18:1798–1803. 10.1038/nn.4167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki G, Hansel C (2018) Synaptic potential and plasticity of an SK2 channel gate regulate spike burst activity in cerebellar Purkinje cells. iScience 1:49–54. 10.1016/j.isci.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki G, Piochon C, Adelman JP, Hansel C (2012) SK2 channel modulation contributes to compartment-specific dendritic plasticity in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron 75:108–120. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Kramer EE, Mercaldo V, Rashid AJ, Insel N, Frankland PW, Josselyn SA (2016) Neuronal allocation to a hippocampal engram. Neuropsychopharmacology 41:2987–2993. 10.1038/npp.2016.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedarzani P, Mosbacher J, Rivard A, Cingolani LA, Oliver D, Stocker M, Adelman JP, Fakler B (2001) Control of electrical activity in central neurons by modulating the gating of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. J Biol Chem 276:9762–9769. 10.1074/jbc.M010001200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignatelli M, Ryan TJ, Roy DS, Lovett C, Smith LM, Muralidhar S, Tonegawa S (2019) Engram cell excitability state determines the efficacy of memory retrieval. Neuron 101:274–284.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piochon C, Titley HK, Simmons DH, Grasselli G, Elgersma Y, Hansel C (2016) Calcium threshold shift enables frequency-independent control of plasticity by an instructive signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:13221–13226. 10.1073/pnas.1613897113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs BG. (2019) Changes in cerebellar intrinsic neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity result from eye-blink conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem 166:107094. 10.1016/j.nlm.2019.107094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs BG, Tomsic D, Gusev PA, Alkon DL (1997) Dendritic excitability microzones and occluded long-term depression after classical conditioning of the rabbit's nictitating membrane response. J Neurophysiol 77:86–92. 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs BG, Gusev PA, Tomsic D, Alkon DL, Shi T (1998) Intracellular correlates of acquisition and long-term memory of classical conditioning in Purkinje cell dendrites in slices of rabbit cerebellar lobule HVI. J Neurosci 18:5498–5507. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05498.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz AB, Freeman JH (2014) Localization of the cerebellar cortical zone mediating acquisition of eye-blink conditioning in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem 114:148–154. 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker M, Krause M, Pedarzani P (1999) An apamin-sensitive Ca2+-activated K+ current in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Brinke MM, Boele HJ, Spanke JK, Potters JW, Kornysheva K, Wulff P, IJpelaar AC, Koekkoek SK, De Zeeuw CI (2015) Evolving models of Pavlovian conditioning: cerebellar cortical dynamics in awake behaving mice. Cell Rep 13:1977–1988. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Brinke MM, Heiney SA, Wang X, Proietti-Onori M, Boele HJ, Bakermans J, Medina JF, Gao Z, De Zeeuw CI (2017) Dynamic modulation of activity in cerebellar nuclei neurons during Pavlovian eye-blink conditioning in mice. eLife 6:e28132. 10.7554/eLife.28132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LT, Moyer JR Jr, Disterhoft JF (1996) Transient changes in excitability of rabbit CA3 neurons with a time course appropriate to support memory consolidation. J Neurophysiol 76:1836–1849. 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titley HK, Brunel N, Hansel C (2017) Toward a neurocentric view of learning. Neuron 95:19–32. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang Y, Dieudonné S, De Schutter E (2018) Voltage- and branch-specific climbing fiber responses in Purkinje cells. Cell Rep 24:1536–1549. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]