Abstract

Objective. To identify skills and attributes that pharmacy students need upon graduation if planning to pursue a career path as a community pharmacy practice care provider.

Methods. In-depth interviews with community pharmacy stakeholders were conducted, audio-recorded, and transcribed. Interview transcripts were thematically analyzed to identify the skills and attributes pharmacy students need upon graduation to be prepared to practice as a community pharmacy-based care provider.

Results. Forty-two participants were interviewed. Identified attributes that were deemed transformative for community pharmacy practice included three behaviors, five skills, and two knowledge areas. Behavioral attributes needed by future community pharmacists were an approach to practice that is forward thinking and patient-centric, and having a provider mentality. The most commonly mentioned skill was the ability to provide direct patient care, with other skills being organizational competence, communication, building relationships, and management and leadership. Critical knowledge areas were treatment guidelines and drug knowledge, and regulatory and payer requirements. Additional skills needed by community pharmacy-based providers included identification and treatment of acute self-limiting illnesses and monitoring activities for chronic health conditions.

Conclusion. Essential attributes of community pharmacists that will allow practice transformation to take place include behaving in a forward-thinking, patient-centric manner; displaying a provider mentality through use of effective communication to build relationships with patients and other providers, and learning how to meet regulatory and payer requirements for prescribers. These attributes should be fostered during the student’s experiential curriculum.

Keywords: community pharmacy, pharmacist provider, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Community pharmacists are the largest and most accessible group of health care providers in the US health care system. There are more than 60,000 community-based pharmacies in the United States employing more than 170,000 pharmacists.1 Further, 93% of Americans live within five miles of a community pharmacy.2 No longer responsible solely for the provision of drug products, community pharmacists play an integral part in community health and wellness through expanded services such as medication management and reconciliation, educational and behavioral counseling, and preventative health services.3 Patient care services in specialty areas such as heart failure medication management and point-of-care testing in pharmacies have been described in the literature.4-8 These expanded services are within the pharmacist’s scope of practice and facilitated via collaborative practice agreements (CPAs) with prescribers.9 Most states allow pharmacists to prescribe and modify therapy through CPAs.10

Despite the pivotal role of pharmacists on the health care team, pharmacists have not historically been recognized as health care providers by national health policy makers and payers.11 Lack of reimbursement for pharmacist services performed has been a major impediment to expanded care provision.12,13 More recently, significant legislative breakthroughs have been made, with states such as California mandating recognition of pharmacists as care providers.14 In May 2015, legislators in Washington State passed a bill (SB5557) requiring that pharmacists be included in health insurance medical provider networks and thus must be compensated for the patient care they provide within their scope of practice.15

As federal and state legislation moves forward to ensure payment to pharmacists for patient care services, schools and colleges of pharmacy must adequately prepare students to practice in this changing environment. A 2012 National Association of Chain Drug Stores (NACDS) Foundation, National Community Pharmacy Association (NCPA), and American Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) identified 80 entry-level performance competencies needed for community pharmacy practice.16 Over 80% of these competencies addressed non-dispensing functions, indicating that dispensing medications should be a small part of the skill set needed by pharmacy graduates. In a subsequent report, only one of 23 different identified competency areas expected by community pharmacy employers of new pharmacy graduates described dispensing skills.17 Additionally, the 2013 Center for Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) outcomes did not list “dispenser” as a key role for pharmacists.18 The paradigm change of pharmacist as care provider rather than product dispenser in the community pharmacy setting appears mandated on several levels and will be an important coming disrupter of current pharmacy practice.19

Another disrupter is the expanding role of the pharmacy technician, with pilot programs in place for technicians to check filled prescriptions for accuracy.20,21 The Idaho State Board of Pharmacy in 2017 passed new rules stating that certified technicians, if authorized by a pharmacist, could receive a new verbal prescription drug order from a prescriber, consult with a prescriber on needed clarifications for prescriptions being filled, transfer a prescription drug order to another pharmacy, verify accuracy of filled prescription products, and administer immunizations.22 Involvement in these functions foretell a future where technicians will largely be responsible for many functions currently performed by pharmacists.

An additional disrupter of current pharmacy practice is the trend toward the “retail clinic” within chain store pharmacies. These clinics, typically staffed by nurse practitioners and placed in a location close to the pharmacy, have a lower cost of care yet a higher frequency of visits compared to traditional medical clinics.23,24 The higher frequency of visits illustrates and reinforces the public’s perception of the pharmacy as the first place to go for subacute health conditions. Clinics within pharmacies typically operate within a local health care system, but patients who select their pharmacy based on convenience and location may not be a member of that health care system.25 The ability to assess subacute conditions and make accurate clinical decisions to treat, watch, or refer the patient to a physician are important skills needed by the community pharmacy care provider. The role of the community pharmacy practice provider has been recognized legislatively in Idaho, where House Bill 191 increased the pharmacist’s prescriptive scope of practice to medical conditions that do not require a new diagnosis, are minor and self-limiting, have a test that can be performed and the results used to guide diagnosis or clinical decision-making, or threaten the immediate health or safety of the patient if not dispensed.26 Pharmacists who practice in community settings may need to acquire new diagnostic and triage skills to successfully navigate the change from being a product dispenser to a care provider.27

Pharmacists in community practice currently spend over half of their time on activities related to dispensing.28 From conversations with preceptors, we learned that at many community pharmacy sites a pharmacist’s performance was judged and staffing decisions were made based primarily on how many or how quickly prescriptions were filled. Given this reality, we wondered how community pharmacy stakeholders such as staff pharmacists, pharmacy managers, and educators of future community pharmacists perceived the practice environment of the future and what new attributes would be needed by pharmacists to practice in that future environment. We thus designed a study to determine stakeholders’ vision of the future of pharmacy practice and to use our findings to design a curriculum to prepare students for that vision. The primary objective of the current report was to distinguish and better understand key attributes needed by community pharmacy providers in a future where they will be reimbursed primarily for services provided, rather than for products dispensed.

METHODS

This study was a thematic analysis of community pharmacy stakeholders’ opinions obtained through key informant interviews. A database of current preceptors at our institution was used to identify individuals practicing in the area of community pharmacy. Stratified purposeful sampling was used to select a roughly equal number of potential participants who were practicing community pharmacists and pharmacists who were not practicing community pharmacy on a daily basis but oversaw or otherwise influenced practice of those who did.29 Potential participants were contacted by email and invited to participate. The study protocol was reviewed by a University of Washington Human Subjects Division subcommittee and determined to qualify for exemption.

A semi-structured interview guide using a neo-positivist approach—where the interviewer asks few open-ended questions and contributes minimally to the conversation—was developed and slightly refined based on feedback from a pilot interview conducted with a small group of faculty members with community pharmacy practice backgrounds.30 The interview guide contained four initial questions, for which the first question was, “What skills will a community pharmacy practitioner of the future need?” The interviewer then showed participants a list of subacute and chronic health conditions, asking which of the conditions participants would feel comfortable treating, and whether the community practitioner of the future would, in the participant’s opinion, be treating those conditions. A fourth initial question was about the degree of dispensing done by pharmacists in the future or whether robotics or technicians would largely fill that role. In addition to asking these scripted questions, the interviewer was allowed to ask probing questions to further clarify participant responses. During the interviews, the four initial questions were followed by three questions about an experiential education curriculum for a future community pharmacy practitioner. Results and conclusions arising from analysis of these subsequent questions were the subject of a separate report.31

The first author conducted all of the interviews, and the second author recorded the session and took notes. All interviews were conducted in private locations at community pharmacies, regional management offices, or other locations convenient to the participants. Interviews ranged from 15 to 50 minutes in duration and were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent. Interviews continued until no new information was detected in two sequential interviews.

All audio-recorded interviews were transcribed and de-identified by a research team member. After an initial reading of the data, the first and second authors independently read and inductively coded32-35 words and phrases in the transcripts using ATLAS.ti, version 7.5.10 (ATLAS.ti GmbH, Berlin, Germany), a qualitative research software program. The primary coders met repeatedly to compare codes, reconcile differences, and improve code definitions until themes and subthemes emerged.35,36 The third author independently reviewed the transcripts, codes, and themes for gaps, inconsistencies, and new interpretations to improve analysis validity.37 The entire research team developed and achieved consensus on the final themes. Verification coding was performed by an individual outside of the research team. Percent agreement, Cohen’s kappa, and Gwet’s first agreement coefficient, used to check intercoder agreement between investigator and verifier coders, were calculated using R, version 3.5.0 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria), a Linux-based compilation of statistical software.38,39 A kappa of greater than 0.6 was considered satisfactory agreement.40 Gwet’s first agreement coefficient was used because Cohen’s kappa is can be overly conservative when coding tasks are difficult because of long and complex participant responses, as was the case in our study.41 Thematic analysis was not performed on the participant responses to the lists of acute and chronic conditions nor to the responses to the question about relegating dispensing tasks in the future to robotics or technicians.

RESULTS

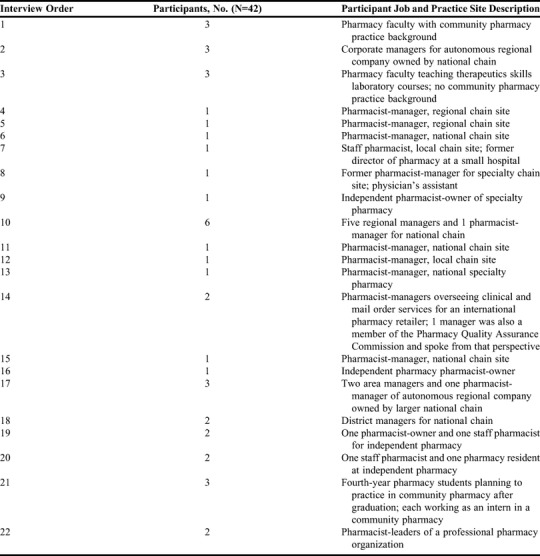

Semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted between August and November 2015. Forty-two subjects were interviewed either singly (n=11), in pairs (n=10), in groups of three (n=15), and in one group of six. Twenty of the 42 participants were pharmacists who practiced in community pharmacies on a daily basis. These 20 included 16 staff pharmacists or pharmacy managers, one resident, and three pharmacy students. The remaining 22 participants did not practice in a community pharmacy on a daily basis but influenced the practice of pharmacists who did. These 22 included 14 area managers, six faculty members (three with community pharmacy background and three teaching therapeutics skills laboratory courses), and two leaders of the state pharmacy organization. Three of the interviews were with pharmacists practicing in sites offering innovative patient care services, eg, in-home visits with patients who would otherwise require placement in a skilled nursing facility, and management of patients with complex HIV/AIDS treatment regimens. Three interviews were with pharmacists who actively educated legislators and whose work resulted in the passing of SB5557 in Washington State. More details about the participants can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Job and Practice Descriptions of Participants in a Study to Identify Attributes Needed by Future Community Pharmacy Providers

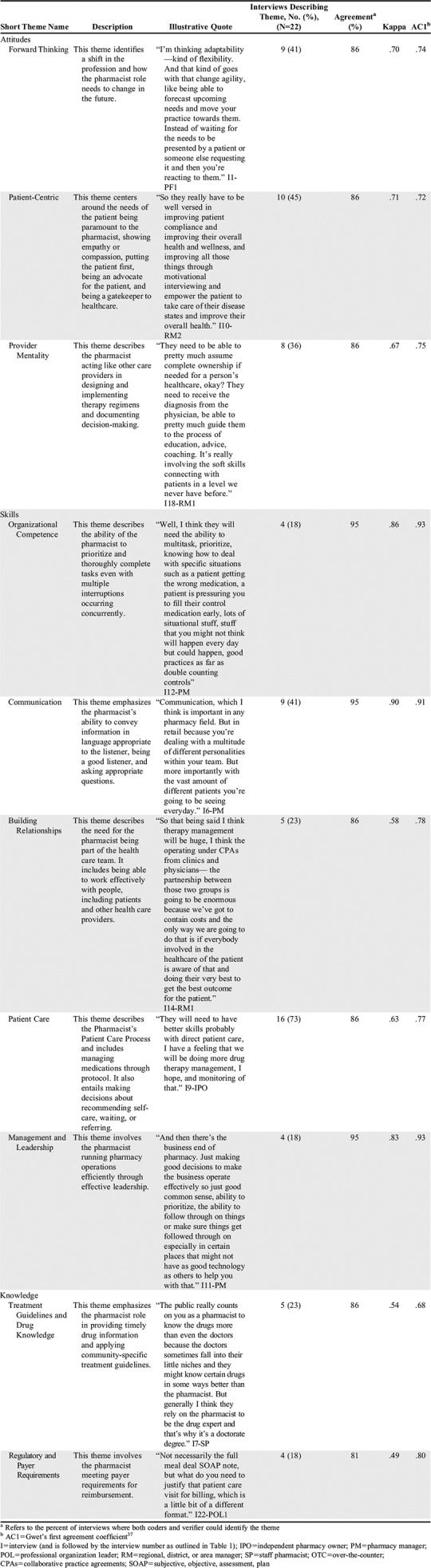

Analysis of responses to the question, “What skills will be needed by a community pharmacy practitioner of the future?” yielded three key attitudinal-behavioral attributes, which included forward thinking, patient-centric, and provider mentality; five skill attributes which included organizational competence, communication, building relationships, patient care, and management and leadership; and two knowledge attributes which included treatment guidelines and drug knowledge, and regulatory and payer requirements. These 10 attributes are further explained in Table 2, which also includes illustrative quotes.

Table 2.

Attributes Needed by Future Community Pharmacy Providers as Identified in Interviews With Community Pharmacy Stakeholders

Stakeholders in this study, particularly pharmacists in daily practice, most frequently named the skill of providing direct patient care as a key attribute. Key attitudes and behaviors that reflected forward thinking and being patient centric were the next most common themes, followed by the characteristic of having a provider mentality, ie, thinking and acting like other prescribers. The need for a forward-thinking attitude and the characteristic of a provider mentality was voiced during each of the regional manager interviews, during two of the three interviews of pharmacists practicing in innovative care settings, and by the individuals who were instrumental in passing SB5557 in Washington State.

When shown a list of minor acute conditions that might be seen in a typical walk-in medical clinic, most of the participants stated they would be comfortable evaluating the items on the list, adding that they evaluated several of the conditions on a daily basis in their current practice. Some participants stated discomfort with some conditions (eye and joint), feeling that their role was primarily referral. Almost every participant brought up skin conditions, suggesting that community pharmacy-bound students need extra training in this area. As one participant remarked, “All pharmacists should have a minor in dermatology.” A few participants noted that the actual services offered would primarily depend on the pharmacy’s usual clientele.

There were three specific points made by participants about pharmacists providing acute care on the same level as a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant. First, clear written guidelines about when to treat and when to refer are needed for every common acute condition. Second, companies are less likely to pay a pharmacist to provide this level of care if they can hire a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant to do so at lower wages. Finally, pharmacists providing this level of care will need personal malpractice insurance at a coverage level similar to that of other providers. One individual who played a key role in passage of the Washington State bill emphasized the importance of taking steps to avoid conflicts of interest by pharmacists who both prescribe and dispense.

Participants also stressed the importance of collaboration with the patient’s primary care provider to obtain the referral for care of chronic health conditions, delineate the limits of care that would be provided, and access laboratory and other data needed to monitor drug therapy. Some participants felt that specialty care would be the focus of care provision by the community pharmacist, while others indicated that specialty care would be best handled in the clinic setting. Pharmacists who were actively practicing were more likely than regional managers to identify barriers to chronic disease state management, particularly lack of access to laboratory data and lack of time to spend with the patient in the current practice model.

In response to the question, “Should the community pharmacist of the future be responsible for dispensing, or should that function be relegated to robotics or technicians?” participants in general felt that robotics and technicians could fulfill almost all the technical functions of the dispensing process. Three sites we visited had robotic systems filling new prescriptions, and several participants noted that the market was driving the dispensing role toward robotics. A participant who was a pharmacy manager and member of the state Pharmacy Quality Commission stated, “I think that technology is coming and coming quickly, so as it moves into that setting I think that most of the standard dispensing functions are going to go away from the pharmacist’s standpoint. We’ve talked about this for years, about doing that, and it never happened because we never really had the technology to make it work, but now we have the technology to make it work.”

The role that participants felt could not be delegated to robotics or technicians was the prospective drug utilization review, which is required by law in Washington State. Also mentioned was the usefulness of knowing the physical characteristics of a drug (for example, knowing tablet size when working with post-stroke patients who have difficulty swallowing) and which drugs are covered by a specific insurance plan.

DISCUSSION

This study clarified what community pharmacy stakeholders feel are the future skills and abilities needed by students planning to practice in this setting. It was important to gain this perspective because up to 50% of graduates from the University of Washington School of Pharmacy enter community pharmacy practice upon graduation. We need to prepare pharmacy students for their changing role in community pharmacy practice even though the nature of that role has not been fully elucidated.

The participants responses revealed that a driver of change in pharmacy practice is the expanding use of robotics in the dispensing process, which was already in place at some of the sites we visited. Another driver of change that was not seen in our study but is evident elsewhere is the enhanced role of the pharmacy technician in completing tasks currently associated with pharmacists, such as assisting with transition of care between the hospital and the community care setting, administering immunizations, and performing some aspects of medication therapy management.42-45 Because immunizations and medication therapy management are what many of the community pharmacists in our study considered to be the “clinical” aspects of their job, clearly the emerging roles for technicians in these areas will make the role of the clinical community pharmacist of the future radically different than it is now. This changing role, which we termed “forward-thinking,” was the top attitudinal-behavioral theme attribute in our study.

The future of community pharmacy practice lies in the provision of direct patient care through patient-centered care, which was the top skill attribute and second most common attitudinal-behavioral attribute seen in our study. Although the skill (ie, direct patient care) and the attribute (ie, patient-centered care) may sound like the same thing, the Pharmacist’s Patient Care Process, which is the skill set that pharmacists must possess to effectively provide care to patients, is different from how pharmacists choose to employ that skill, which is a behavior.46 Desired patient-centered behaviors for all health care providers include interacting with patients and family members, respecting the perspectives and choices of those individuals, sharing information to help them make informed decisions, and encouraging their participation in decision-making; these behaviors will be critical for future community pharmacy practitioners to demonstrate.47,48

Demonstrating a provider mentality, another behavioral theme attribute, will likely be the most difficult change for community pharmacy practitioners. In order to achieve provider status and be paid for providing care, what pharmacists do needs to look more like what other providers do, yet fill a unique and distinct role within the health care team. This evolution in practice will require fundamental changes in expectations by three important groups: the public, other health care practitioners, and all members of the pharmacy profession. Community pharmacy practice must undergo a seismic shift similar to the transformation of nurses to nurse practitioners, such that when a patient enters a community pharmacy, the expectation is that pharmacists will collect a thorough history, assess a patient’s clinical condition, decide on management of the presenting condition and whether to prescribe or refer, identify appropriate medications, seek patient input into the treatment plan, and monitor response to therapy.49 Notably, dispensing, which is currently a large component of community pharmacy practice, is not a part of this description.28,50-52

An important challenge will be shifting the public’s expectations of pharmacists, because many people believe that a pharmacist’s abilities are limited to drug dispensing, providing information, and managing the side effects of drugs.53-56 During study visits to collect information from our stakeholders, we observed common wording on the signage inside stores, with “Pharmacy” in large letters above the pharmacy area of the store and smaller signs on either side reading, “Drop Off” and, “Pick Up,” reinforcing the public’s perception that the purpose of a pharmacy is to provide a product rather than a service. In the near future, community pharmacists will need to have and use a consultation room to provide services for patients with acute care needs and those with chronic health conditions. This room will need to be adjacent to but separate from the prescription filling area and will be where the community pharmacist will primarily work. During scheduled patient visits, pharmacists will assess chronic medical conditions for patients receiving drug therapy (a role that most participants in our study agreed that pharmacists can do) and take medication and health histories for new patients presenting with acute health conditions.57

Another important challenge will be assimilating community pharmacists into the network of other health care providers.58 A forum for regular communication about care of their mutual patients will allow pharmacists to more fully integrate into the patient’s health care team. In pharmacies with an embedded acute care clinic staffed by a nurse practitioner, the two provider’s consultation rooms should be in close proximity to facilitate interprofessional dialogue.

The final challenge will lie in shifting current community pharmacy practice in the direction of the pharmacist as provider. There are structural, logistical, and legal hurdles that may seem insurmountable to current practicing community pharmacists. In our study, the themes of forward thinking and provider mentality were more commonly voiced by practitioners who were not practicing community pharmacy on a daily basis. It is difficult for pharmacists who are responding to the daily needs and responsibilities of the practice environment to imagine how that environment could be different. Today’s community pharmacists will need thoughtful support from their corporate management, regulatory agencies, and professional organizations in making the transition to a primarily patient care practice.59 Many community pharmacists will need to retool their skills in patient examination, assessment, and prescribing for conditions commonly seen in their patients. Clinical community pharmacists will need to document all care decisions in a format that will meet payer audit requirements and also communicate clinical reasoning to the patient’s other care providers. This vision may seem radical, yet many of the drivers for pharmacists to become primary care providers are aligning.60

Changes in community pharmacy practice will affect and be affected by how pharmacists are trained. Students planning to enter community pharmacy practice will need excellent physical and verbal examination skills and enhanced training in diagnosis of self-limited medical conditions similar to those on the list we showed to participants in our study. Many of the conditions on the list were identified areas of training in the American College of Clinical Pharmacy’s didactic curriculum toolkit,61 so pharmacy education programs likely have the didactic coursework in place, although additional skills training and experiential practice will be needed. Pharmacy educators should examine the curricular transformation from nurse to nurse practitioner as similar curricular changes could help pharmacy students build confidence in their ability to practice as a provider. Initially, a paucity of role models will make it difficult for students and current practitioners to envision how such a practice would look. It may be desirable for students planning to become community pharmacists to complete an advanced pharmacy practice experience with a nurse practitioner, to enable building of diagnostic and triage skills. Coursework will need to introduce students to the complexities of medical billing.

Data analysis in any qualitative study is inevitably influenced by the lens through which the investigators view the data, so it is important to explain what that lens was. The first author in this project is an experiential education director who uses qualitative research methods to better understand the experiences of preceptors and students in the practice setting, interacts regularly with pharmacy preceptors at community practice sites, and has family members who have practiced in community pharmacy. The second author was trained in social science data collection and analysis techniques during a human-centered design and engineering degree program and has no background or training in pharmacy. The third author has experience as a community pharmacist and is an implementation scientist evaluating community pharmacy patient care services. None of the authors had a role in the passage of SB5557 in Washington State.

This study had several limitations. We asked pharmacists about acute and chronic health conditions but did not inquire about preventive health care, yet community pharmacists participate in preventative care initiatives, such as administering immunizations. Participant answers to questions may have been influenced by passage of SB5557; thus, pharmacists from states without similar legislation might have different perspectives about the future of pharmacy practice. Most participants practiced in an urban environment and so would likely have a different vision of practice compared to community pharmacists from rural areas. Finally, we only interviewed pharmacy stakeholders who were familiar with the pharmacist’s scope of practice. Interviewing other stakeholders, particularly other health care providers and patients who would be the recipients of pharmacists’ care, will be an important next step in the process of envisioning the future role of pharmacists as care providers.

This study helped us characterize the skills and attributes needed by future pharmacy graduates from our program planning to enter community pharmacy practice. Conducting this study also provided an invaluable opportunity to engage our community pharmacy practice partners and incorporate their insights into our curriculum.

CONCLUSION

Community pharmacists are the outward face of the pharmacy profession, and that seen by most members of the public. In order for community pharmacists to become the care providers of the future, they will need to spend the majority of their time providing direct patient care rather than dispensing, which will be largely done in the future by robotics and pharmacy technicians. Essential attributes for community pharmacists of the future include the attitudinal qualities of being forward thinking, patient-centric, and having a provider mentality. These attributes will allow community pharmacists to effectively address and be reimbursed for the acute and chronic medical conditions experienced by their patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the time given and thoughtful answers expressed by all the participants in this study and the assistance of Donal O’Sullivan, PhD, with statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Select features of state pharmacist collaborative practice laws. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Published December 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/pharmacist_state_law.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pharmacies: improving health, reducing costs. Arlington (VA): National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Revised Mar 2011. http://www.nacds.org/pdfs/pr/2011/PrinciplesOfHealthcare.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 3.Avalere Health LLC. Exploring pharmacists’ role in a changing healthcare environment. Released May 21, 2014. https://avalere.com/insights/exploring-pharmacists-role-in-a-changing-healthcare-environment. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 4.Bleske BE, Dillman NO, Cornelius D, et al. . Heart failure assessment at the community pharmacy level: a feasibility pilot study. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2014;54(6):634-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klepser DG, Klepser ME. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-provided treatment of adult pharyngitis. Am J Managed Care . 2012;18(4):e145-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weidle PJ, Lecher S, Botts LW, et al. . HIV testing in community pharmacies and retail clinics: a model to expand access to screening for HIV infection. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(5):486-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darin KM, Klepser ME, Klepser DE, et al. . Pharmacist-provided rapid HIV testing in two community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2015;55(1):81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gubbins PO, Klepser ME, Dering-Anderson AM, et al. . Point-of-care testing for infectious diseases: opportunities, barriers, and considerations in community pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2014;54(2):163-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albanese NP, Rouse MJ. Scope of contemporary pharmacy practice: roles, responsibilities, and functions of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2010;50(2):e35-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBane SE, Dopp AL, Abe A, et al. . Collaborative drug therapy management and comprehensive medication management—2015. Pharmacotherapy . 2015;35(4):e39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report to the US Surgeon General 2011. Rockville (MD): US Public Health Service; Published Dec 2011. http://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hale J, Murawski MM, Ives TJ. Perceived successes and challenges of clinical pharmacy practitioners in North Carolina. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2013:53(6):640-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isasi F, Krofah E. The expanding role of pharmacists in a transformed health care system. Washington (DC): National Governors Association Center for Best Practices. Published January 13, 2015. http://classic.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/2015/1501TheExpandingRoleOfPharmacists.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 14.California provider status law effective January 1. Washington (DC): American Pharmacists Association. Published February 1, 2014. https://www.pharmacist.com/article/california-provider-status-law-effective-january-1. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 15.Related to services provided by pharmacists. Washington State Legislature S.B. 5557, 64th Legislature, Regular Session (2015). http://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2015-16/Pdf/Bills/Senate%20Passed%20Legislature/5557-S.PL.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 16.NACDS Foundation-NCPA-ACPE Task Force. Entry-Level Competencies Needed for Community Pharmacy Practice 2012. https://apps.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/NACDSFoundation-NCPA-ACPETaskForce2012.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 17.Vlasses PH, Patel N, Rouse MJ, Ray MD, Smith GH, Beardsley RS. Employer expectations of new pharmacy graduates: implications for the pharmacy degree accreditation standards. Am J Pharm Educ . 2013;77(3):Article 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. . Center for the advancement of pharmacy education 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ . 2013;77(8):Article 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romanelli F, Tracy TS. A coming disruption in pharmacy? Am J Pharm Educ . 2015;79(1):Article 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreski M, Myers M, Gainer K, Pudlo A. The Iowa new practice model: advancing technician roles to increase pharmacusts’ time to provide patient care services. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2018;58(3):268-274.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Napier P, Norris P, Braund R. Introducing a checking technician allows pharmacists to spend more time on patient-focused activities. Res Soc Admin Pharm . 2018;14(4):382-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Expanded certified pharmacy technician roles. [Internet] Boise (ID): Idaho State Board of Pharmacy newsletter. Published Mar 2017. https://nabp.pharmacy/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ID032017.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 23.Inglehart JK. The expansion of retail clinics—corporate titans versus organized medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(4):301-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashwood JS, Gaynor M, Setodji CM, Reid RO, Weber E, Mehrotra A. Retail clinic visits for low-acuity conditions increase utilization and spending. Health Affairs . 2016;35(3):449-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang JE, Brundage SC, Chokshi DA. Convenient ambulatory care—promise, pitfalls, and policy. N Engl J Med . 2015;373(4):382-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Relating to pharmacy. Idaho State Legislature H.B. 191, 64th Legislature, Regular Session (2017). https://legislature.idaho.gov/sessioninfo/2017/legislation/h0191/. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 27.Clay PA. Pharmacists entering “a brave new world.” J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56(1):104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schommer JC, Pederson CA, Gaither CA, Doucette WR, Kreling DH, Mott DA. Pharmacists’ desired and actual times in work activities: evidence of gaps from the 2004 national pharmacist workforce study. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2006;46(3)340-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guest GS, Namey EE, Mitchell ML. Collecting qualitative data: a field manual for applied research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roulston K. Considering quality in qualitative interviewing. Qual Res . 2010;10(2):199-228. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Sullivan TA, Sy E, Bacci J. A qualitative study designed to build an experiential education curriculum for practice-ready community pharmacy-bound students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(10):Article 6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs . 2008;62(1):107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merriam SB. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res . 1999;34(5 part 2):1189-1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gwet KL. R functions for calculating agreement coefficients. Gaithersburg (MD): Advanced Analytics, LLC; 2010. http://www.agreestat.com/r_functions.html. Accessed May 26, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martire RL. Reliability coefficients, version 1.3.1. Vienna (Austria): The R Project. Published May 12, 2017. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rel/index.html. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 40.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med . 2005;37(5):360-363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Wedding D, Gwet KL. A comparison of Cohen’s kappa and Gwet’s AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: a study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Med Res Methodol . 2013;13(Apr 29):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey JE, Surbhi S, Bell PC, Jones AM, Rashed S, Ugwueke MO. SafeMed: using pharmacy technicians in a novel role as community health workers to improve transitions of care. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2016;56(1):73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKeirnan KC, Frazier KR, Nguyen M, MacLean LG. Training pharmacy technicians to administer immunizations. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2018;58(2):174-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lengel M, Kuhn CH, Worley M, Wehr AM, McAuley JW. Pharmacy technician involvement in community pharmacy medication therapy management. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2018;58(2):179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gernant SA, Nguyen MO, Siddiqui S, Schneller M. Use of pharmacy technicians in elements of medication therapy management delivery: a systematic review. Res Soc Admin Pharm . 2018;14(10):883-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The pharmacist’s patient care process. Alexandria (VA): The Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Released May 29, 2014. https://jcpp.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/PatientCareProcess-with-supporting-organizations.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- 47.Patient and family-centered care. [Internet] Bethesda (MD): Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Accessed May 26, 2019. http://www.ipfcc.org/about/pfcc.html.

- 48.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ross JD, Kettles AM. Mental health nurse independent prescribing: what are nurse prescribers’ views of the barriers to implementation? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs . 2012;19(10):916-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davies JE, Barber N, Taylor D. What do community pharmacists do? results from a work sampling study in London. Int J Pharm Pract . 2014;22(5):309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gregory P, Austin Z. Postgraduation employment experiences of new pharmacists in Ontario in 2012-2013. Can Pharm J . 2014;147(5):290-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van de Pol JM, Geljon JG, Belitzer SV, Frederix GWJ, Hovels AM, Bouvy ML. Pharmacy in transition: a work sampling study of community pharmacists using smartphone technology. Res Soc Admin Pharmacy. 2019;15(1):70-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gillaumie L, Ndayizigiye A, Beaucage C, et al. . Patient perspectives on the role of community pharmacists for antidepressant treatment: a qualitative study. Can Pharm J . 2018;151(2):142-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kember J, Hodson K, James DH. The public’s perception of the role of community pharmacists in Wales. Int J Pharm Pract . 2018;26(2):120-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yanicak A, Mohorn PL, Monterroyo P, Furgiuele G, Waddington L, Bookstaver PB. Public perceptions of pharmacists: television portrayals from 1970 to 2013. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2015;55(6):578-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peterson GM, Jackson SL, Hughes JD, Fitzmaurice KD, Murphy LE. Public perceptions of the role of Australian pharmacists in cardiovascular disease. J Clin Pharm Ther . 2010;35(6):671-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnes B, Hincapie AL, Luder H, Kirby J, Frede S, Heaton PC. Appointment-based models: a comparison of three model designs in a large chain community pharmacy setting. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2018;58(2):156-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacNaughton K, Chreim S, Bourgeault IL. Role construction and boundaries in interprofessional primary health care teams: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res . 2013;13:486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Franco-Trigo L, Tudball J, Benrimoj SI, Sabater-Hernandez D. A stakeholder visioning exercise to enhance chronic care and the integration of community pharmacy services. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2019;15(1):31-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trygstad T. Payment reform meets pharmacy practice and education transformation. N C Med J . 2017;78(3):173-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwinghammer TL, Crannage AJ, Boyce EG, et al. . The 2016 ACCP pharmacotherapy didactic curriculum toolkit. Pharmacotherapy . 2016;36(11):e189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]