Abstract

We examined familial and cultural factors predicting parent–child (dis)agreement on child behavior and parenting problems. Immigrant Chinese parents (89.7% mothers; M age=44.24 years) and their children (62 boys; 57.9%) between the ages of 9 and 17 years (M=11.9 years, SD=2.9) completed measures of parent punitive behavior and child problems. Concordance in item profiles and discrepancies in overall problem levels were assessed. Overall, immigrant parents reported fewer child and parenting problems than did their children. Relationship closeness predicted less disagreement in ratings of child internalizing symptoms and punitive parenting. Parental acculturative stress and parent–child acculturation dissonance predicted more disagreement regarding internalizing problems. The findings highlight potential under-identification of internalizing problems among immigrant Chinese families that may be driven by acculturation processes.

Previous studies have generally revealed low to moderate parent–child agreement on reports of child problems (e.g., Achenbach, 2006; Briggs-Gowan, Carter, & Schwab-Stone, 1996). In a meta-analysis of 119 studies, Achenbach, McConaughy, and Howell (1987) found that ratings of children’s problems among different informants were often discrepant, with a mean correlation of .25 between parents’ and children’s ratings. In a study of clinic-referred families, almost two thirds of parents and children failed to agree on the primary target problem for which the child needed help, and more than one third could not agree on a single problem to target in treatment (Yeh & Weisz, 2001). Modest agreement also has characterized parent–child ratings of parental behavior, with children reporting lower levels of family cohesion and adjustment than their parents (e.g., Gaylord, Kitzmann, & Coleman, 2003; Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & von Eye, 2000). For example, Tein, Roosa, and Michaels (1994) found correlations ranging from .13 to .36 between mother and child reports of mother’s behavior on scales of the Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (Schaefer, 1965).

Parent–child discrepancies in problem identification may be heightened among ethnic minority families, where expectations about appropriate youth and parent behavior may diverge as a function of differential orientations toward ethnic and dominant cultural values. Although one study has suggested elevated parent–child disagreement in ratings of child in ethnic minority families compared to non-Hispanic White (NHW) families (Youngstrom, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2000), much of this research has focused on child and parent characteristics that predict discrepancies in problem ratings, with little attention to ethnic or cultural variation. Other studies have examined the effect of race on the pattern of informant reports (e.g., Wachtel, Rodrigue, Geffken, Graham-Pole, & Turner, 1994; Walton, Johnson, & Algina, 1999), but specific cultural processes that may be more proximal than race to explaining parent–child agreement have not been studied. Moving beyond racial/ethnic group contrasts to the study of specific cultural processes within groups of interest is a priority for advancing our understanding the mechanisms explaining observed diversity in mental health indicators (Betancourt&Lopez, 1993). Understanding familial processes related to immigrant family adaptation is a major priority as children of immigrants are projected to represent at least one fourth of all U.S. children by 2010 (Capps, Fix, Ost, Reardon-Anderson, & Passel, 2005).

Candidate cultural explanations for racial/ethnic differences in informant agreement may include differential interpretation and tolerance for child and adolescent behaviors (Lau et al. 2004). Weisz et al. (1997) contended that cultural differences in adult appraisals of child behavior problems may be governed by socialized attitudes and beliefs about what constitutes normative versus atypical child development. NHW parents may have more exposure to Western conceptions of child mental health and may be more vigilant about child behavior problems than immigrant minority parents (Li, Su, Towners, & Varley, 1989).

In addition, immigrant parents often encounter stress associated with adjusting to a new environment and culture that involves overcoming language barriers, experiencing discrimination, and social isolation (Berry & Kim, 1988). This acculturative stress experienced by immigrant parents may contribute to asynchrony with their children, because general levels of family stress tend to predict parent–child disagreement on ratings of child behavior problems. Parents who report higher levels of family and parenting stress (Jensen, Xenakis, Davis, & Degroot, 1988; Youngstrom et al., 2000) and symptoms of depression (Chi&Hinshaw,2002;Richters,1992;Youngstrom,Izard, & Ackerman, 1999) tend to report greater child problems, perhaps due to reduced tolerance for child misbehavior.

Furthermore, youth in immigrant families may acculturate more rapidly than their parents given greater their exposure to host culture socialization influences and relative openness to adopting new values and behaviors (Okagaki & Bojczyk, 2002). This dissonant acculturation in immigrant families may result in increased conflict, breakdowns in communication, and emotional distancing between parents and children (e.g., Hwang, 2006). Decreased family communication and increased family conflict are, in turn, associated with poorer agreement on ratings of child and family problems (Grills & Ollendick, 2002). As such, these intergenerational differences in cultural orientation or acculturation may be associated with greater parent–child discrepancies in the assessment of behavior.

Research has yet to examine parent–child (dis)agreement and its familial and cultural correlates in Chinese immigrant families, the second largest foreign-born immigrant group in the United States. However, it is plausible that certain traditions and values associated with Chinese culture may exacerbate discrepancies between parent and child perspectives. Chinese culture is often described as shame based with its members being concerned with face-saving to protect the integrity of the family (Zane & Yeh, 2002). Chinese parents reared in a face-oriented culture may be less willing than their Chinese American children to endorse child and family problems for fear of negative evaluation. For example, children’s bids for greater autonomy through defiance may be a normative in American culture but may arouse shame owing to a violation of the Confucian ethic on filial piety (Phinney & Ong, 2002). Thus, Chinese American parents may be less likely than their children to freely report youth behavior problems, resulting in discrepant ratings where parents underreport problems relative to youth.

Cultural perspectives on childrearing may also be associated with discordant in ratings of parent behavior. Compared to NHW parents, Chinese American parents appear to place a stronger emphasis on parental control and have at times been described as authoritarian and restrictive in their discipline practices (e.g., Lin & Fu, 1990). Some data suggest that physical punishment may be more normative among Chinese American families compared to NHWs (Kelley & Tseng, 1992). With exposure to American models of family relations and childrearing, Chinese American children may come to have different views of parenting. Juang, Syed, and Takagi (2007) found that intergenerational discrepancies in attitudes toward parenting were common in Chinese American families. In 81% of the parent–youth dyads, parents held stronger values favoring strict control compared to their children. Given differing generational points of view on parenting, Chinese American youth may adopt a lower threshold for reporting instances of punitive parent behavior than their parents who may view those same actions as appropriate discipline practices.

Thus, an array of cultural considerations appear relevant to the study of parent and child (dis)agreement in ratings of child and parenting problems in Chinese American families. In addition to the sociodemographic and clinical factors that are typically associated with parent–child (dis)agreement, variables related to the distinctive cultural and interpersonal contexts of immigrant families are worthy of examination. The central aim of this study was to examine general and cultural correlates of parent–child (dis)agreement concerning both child behavior problems and parental punitive behavior in a sample of immigrant Chinese families. We sampled strategically through various points of engagement in the community in order to survey families at varying levels of risk for child behavior and parenting problems. We included Chinese American families referred from community agencies providing social and mental health services for children and families, child protective services (CPS), and community schools. This purposive sampling was pursued to yield increase variability on the dependent variables, and accordingly a greater range of dispersion between parent and child informants than might be observed in a general community sample.

We had two objectives. First, we examined the extent of parent–child discrepancies and agreement on ratings ofchild of child internalizing and externalizing problems and parental punitive disciplinary practices. We hypothesized that children in immigrant Chinese families would report more child problems and parental punitive behavior than their parents, irrespective of problem type. This prediction is based on the literature on loss of face among adults of Chinese descent (Zane & Yeh, 2002), generational differences of perspectives on parental control (Juang et al., 2007), and emergent findings of minority family disagreement on symptom report (Lau et al., 2004). Second, we examined whether general family contextual and cultural variables were related to parent–child (dis)agreement. In terms of general factors, we hypothesized that relationship closeness would be associated with greater parent–child agreement and fewer discrepancies. In terms of cultural factors, we hypothesized that acculturative stress, acculturation-related conflict, and parent–child acculturation dissonance would be related to increased discrepancies and lower agreement.

In our analyses of the relationships between family factors, cultural factors, and parent–child (dis)agreement, we controlled for parental distress. Studies have generally found that parental distress is strongly associated with informant discrepancies (e.g., Youngstrom et al., 1999). In our study, we tested whether cultural factors related to (dis)agreement over and above the effect of parental distress. In addition, we also controlled for child age as older children have higher agreement with their parents on ratings of child psychopathology (e.g., Grills & Ollendick, 2002). We also examined (dis)agreement by child behavior problem type, because there is greater discordance for internalizing problems compared to externalizing problems (Cantwell, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1997; Herjanic & Reich, 1997). Likewise, we analyzed (dis)agreement regarding parental verbal punitive behavior separately from parent physical punitive behavior.

METHOD

Participants

Participants for this cross-sectional study were 107 Chinese immigrant parents (96 mothers (89.7%; M age=44.24 years) and their children (62 boys; 57.9%) between the ages of 9 and 17 years (M=11.9 years, SD=2.9). The sample included 37 families referred from CPS who had previous allegations of suspected child maltreatment, 33 families referred from community mental health and social service agencies, and 37 families referred from community schools. Families from CPS were considered high risk for parenting difficulties, whereas service-seeking families were thought to be at higher risk for child behavior problems, and families from community schools were considered lower risk for these concerns. The parent participants have resided in the United States for an average of 17.3 years (SD=6.81). The majority of the parents maintained either full-time (41.1%) or part-time (19.6%) employment. Recruitment was facilitated by staff at referring agencies and school sites. Flyers were distributed to clients receiving services at agencies and parents in community schools serving the same neighborhoods. The flyers remarked that immigrant families commonly face challenges in adjusting to life in the United States and indicated that the purpose of the study was to learn about the difficulties that Chinese American families encounter in parenting and communication. The flyers instructed the parents to provide identified agency or school staff with their contact information if they were interested in being contacted by research staff to learn more about the project. In this manner, 203 parents provided either verbal or written consent to be contacted by research staff for this study. Of the parents who provided consent to be contacted: 71.4% (n=145) completed the interview, 15.3% (n=31) refused to participate, 6.9% (n=14) were ineligible, and 6.4% (n=13) couldn’t be reached. Those children aged 9 years and older (n=107) were also interviewed for 30min about their perceptions of their parents’ behaviors, their perceived closeness with the parents, and their own adjustment. The current study thus included the 107 parent–child dyads for whom we had both child and parent reports (74% of the parents who completed the interview).

Procedure

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ academic institution; the County Departments of Mental Health, Children and Family Services; Public Social Services; and the dependency court. After informed consent was obtained from parents and verbal assent was obtained from children, parents and children were interviewed separately in respondent homes. Parents were interviewed via audio-computer assisted structured interview (ACASI) and children were interviewed face-to-face by trained bilingual research assistants. The use of ACASI was indicated for two reasons. First, many of the parents had limited literacy skills in both Chinese and English. Second, it was thought that the coverage of sensitive topics in face-to-face interviews was not advisable when the interviewers were not well known to the family. All measures underwent translation, backtranslation, and consensus reconciliation for conceptual equivalence. All parents completed the questionnaires in either Mandarin or Cantonese Chinese with the exception of one parent who completed them in English. One child chose to complete the measures in Mandarin Chinese; all other children were surveyed in English.

Measures

Parental punitive behavior

The Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998) is a widely used 22-item scale that measures parents’ use of specific acts of physical and verbal punitive behavior in response to a child transgression in the past year. The 9 items from the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale Minor and Severe Assault scales were used as an indicator of parent-reported physical punitive behavior (e.g., “Spanked him/her on the bottom with your bare hand”). Parents and children indicated the frequency of parents’ use of each tactic in the last year from 0 (never) to 6 (greater than 20 times) when the child did something wrong or made the parent upset. Five items from the Psychological Aggression Scale were used to assess verbal punitive behavior (e.g., “Swore or cursed at him/her” or “Said I would send him/her away or kick him/her out of the house”). The Chinese translation of the Conflict Tactics Scale has shown satisfactory reliability, with alphas ranging from .76 to .86 (Tang, 1994, 1996). Internal consistency of the punitive behavior scales in the current study were adequate for parent report (physical, α=.71; verbal, α=.68) and child report (physical, α=.72; verbal, α=.72).

Child behavior problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1987) contain 118 and 102 descriptions of behavioral and emotional problems, respectively, where the informant rates the extent to which each item was true in the previous 6 months, using a 3-point scale, from 0 (not at all true) to 1 (somewhat or sometimes true) to 2 (true or often). Items were summed to create two broad band factor scores for Internalizing (Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn, and Somatic Complaints) and Externalizing (Aggressive and Destructive) problems. Published internal consistency estimates of the Chinese version of the CBCL are satisfactory with alphas of .80 and .83 for the Internalizing and Externalizing subscales, respectively (Yang, Soong, Chiang, & Chen, 2000). Test–retest reliability estimates also fell in the .80 range across the CBCL and YSR subscales when used in a Chinese sample (Leung et al., 2006).

Relationship closeness

The 30-item People in My Life (Cook, Greenberg, & Kusche, 1995) measures the quality of children’s relationships with parents and peers using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Fifteen items were used to measure the emotional bond between parent and child with 5 items tapping the three dimensions of Trust (e.g., “I can count on my parents to help me when I have a problem”; α=.77), Communication (e.g., “My parents listen to what I have to say”; α=.80), and Alienation which is reverse coded (e.g., “My parents don’t understand what I am going through these days”; α=.75). A total mean score was used as a child-report measure of perceived relationship closeness. The internal consistency of the scale was adequate in the present sample (α=.85).

Parental distress

The Parenting Stress Index–Short Form (Abidin, 1995) is a 36-item scale for measuring parental distress. We used the short form item of the Chinese version of the Parenting Stress Index–Short Form, which was validated in research on maltreating samples of parents in Hong Kong (Chan, 1994; Tam, Chan, & Wong, 2006). The 12-item Parental Distress score was used in the current study to examine levels of parental distress (e.g., “I don’t enjoy things as I used to.”). The scale showed good internal consistency in present sample (α=.89).

Parent–child acculturation conflict

The Asian American Family Conflict Scale (FCS; Lee, Choe, Kim, & Ngo, 2000) assesses youth and parent perceptions of parent–child conflicts related to acculturation. This 10-item scale assesses the likelihood of typical conflict situations that reflect intergenerational differences in Asian American families. Reports on the FCS show strong internal consistency (α=.89, 84) and adequate 3-week test–retest stability (r=.80, .84) for youth and parent informants, respectively (Lee et al., 2000; Park, 2001). In terms of convergent validity, Asian American youth scores on the FCS correlate with the familial stress subscale from a commonly used acculturative stress measure (r=.52), and with their perceptions of parent–child acculturation gaps (Lee et al., 2000). In the current sample, internal consistency of the FCS was good (α=.87, .87) for parents and youth.

Parental acculturative stress

The 24-item Societal Attitudinal Familial Environmental Acculturative Stress Scale (Mena, Padilla, & Maldonado, 1987) was administered to parents to measure perceptions of common challenges relevant to acculturation using a 5-point scale from 1 (not stressful) to 5 (extremely stressful). The construct validity of the Societal Attitudinal Familial Environmental Acculturative Stress Scale has been demonstrated with total scores differentiating recent immigrants from second- and third-generation Hispanic adults (Mena et al., 1987), and significant correlations with symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation (Hovey & King, 1996). Items assessed a range of problems such as communication barriers (e.g., “I have trouble understanding others when they speak.”), discrimination (e.g., “In looking for a job, I sometimes feel my ethnicity is a limitation.”), and feelings of marginalization (e.g., “Because of my ethnic background, people often exclude me from their activities.”). A total mean score was used as a parent-report measure of acculturative stress. The scale showed good internal consistency in the current sample (α=.91).

Acculturation

Parent and child acculturation toward the heritage (Chinese) culture was assessed in public and private domains. Public domains include functional and behavioral aspects of acculturation including language, media use, and other lifestyle preferences, whereas private domains include social-emotional and value-related aspects of acculturation (Costigan & Dokis, 2006). Parent and child acculturation toward the host (American) cultures were only assessed in public domains.

The General Ethnicity Questionnaire (GEQ; Tsai, Ying, & Lee, 2000) measures one’s affiliation with the dominant American culture and one’s heritage culture. Parents responded to 38 items measuring their orientation to Chinese culture and toward American culture on a number of cultural domains including language use, social affiliation, engagement in cultural practices, and cultural identification. The GEQ has adequate internal consistency (α=.92, .92), and one-month test–retreat reliability (r=.62, .57, for the GEQ–Chinese and GEQ–American scales, respectively; Tsai et al., 2000). The 14-item subscale of Language Use (e.g., “I speak Chinese/English fluently.”), the 3-item subscale of Activities (e.g., “I engage in Chinese/American forms of recreation”), and the two-item subscale of Food (e.g., “At home, I eat Chinese/American food.”) from the GEQ was used to tap public domains in Chinese and American cultures. These computed Public Acculturation scales had good internal consistency in the current sample (Public Chinese, α=.86; Public American, α=.90).

The private domain of acculturation was measured using the Asian Value Scale (Kim, Atkinson, & Yang, 1999). The Asian Value Scale is a 36-item scale assessing cultural values pertaining to themes such as collectivism, emotional control, and humility. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strong disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Because the Asian Value Scale was validated with Asian American college students but not immigrant parents in the community, we subjected the 36 items to an exploratory factor analysis to inform item/scale selection. In an exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation, five factors emerged. We examined the scree plot and noted a strong descending linear trend in the eigenvalues following the third factor (Reise, Waller, & Comrey, 2000). The first three factors accounted for 43.83% of the variance and included items pertaining to collectivism (e.g., “one should consider the needs of others before considering one’s own needs”), humility (e.g., “one should not be boastful”), and filial piety (e.g., “children should not place their parents in retirement homes”). The item content of these scales reflected values governing interpersonal and family relations, whereas items from the remaining two scales reflected individual self-control (e.g., one should have sufficient inner resources to resolve emotional problems) and achievement values (e.g., occupational failure does not bring shame to the family). In the current study, we elected to use a composite score from these first three factors as measure of private acculturation to Chinese culture as they mapped onto values most relevant family relations. This Private Chinese Acculturation scale showed more favorable internal reliability (α=.76) than the full scale (α=.50) in the current sample. Acculturation toward American culture in private domains was not measured.

Child acculturation was assessed using the Acculturation Scale for Vietnamese (Nguyen & von Eye, 2002) which is a 56-item instrument that assesses involvement in Vietnamese culture and American culture. The Acculturation Scale for Vietnamese demonstrates good internal consistency (α=.88–.89) and concurrent validity demonstrated with expected correlations with measures of English proficiency, years of U.S. residence and education among Vietnamese youth 10 years and older (Nguyen & von Eye, 2002). The measure was modified for use with the current sample by replacing the ethnic label “Vietnamese” with “Chinese.” Acculturation measures, such as the Acculturation Scale for Vietnamese, commonly contain generic items that are worded for a particular ethnic cultural group that reflect indicators of acculturation such as language use and ethnic practices. For example, to assess the Chinese acculturation in the public domain the eight-item subscale of Everyday Lifestyles, a language item was reworded to read “I want to speak Chinese at home” (instead of “I want to speak Vietnamese at home”). And the three-item subscale of Group Interactions was changed similarly (e.g., “I enjoy going to Chinese gatherings/parties.” [instead of “I enjoy going to Vietnamese gatherings/parties”]). The seven-item subscale of Family Orientation (e.g., “Children should follow their parents’ wishes about choosing a career.”) was used to tap the private domain of child acculturation to Chinese. These family orientation values are shared among both Confucian based Vietnamese and Chinese cultures (Nguyen & Williams, 1989). Respondents rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale indicating their agreement with the statement. The measure demonstrated good convergent validity in the current sample; years of U.S. residence was positively correlated with acculturation to American culture (r=.21, p<.05) and negatively correlated with acculturation to Chinese culture (r =.22, p<.05). The subscales yielded good internal consistency in the current sample (Chinese Public, α=. 85; American Public, α=.81; Chinese Private, α=.74).

Data Analyses

We examined the main effects of parent and child acculturation toward the host and heritage cultures on (dis)agreement in ratings of child and parenting problems. To investigate the possibility that acculturation dissonance predicted (dis)agreement, we explored interactions between parent and youth acculturation. Interaction terms were the products of like pairs of centered acculturation scores (e.g., parent and child acculturation to Chinese culture in private domains). Regressing the (dis)agreement scores on the interactions between parent and child acculturation indices, permitted us to examine whether the effects of parental acculturation on (dis)agreement was moderated by child acculturation (or vice versa). For example, greater child acculturation to U.S. culture might predict more disagreement and less agreement only when parents are low on U.S. acculturation. Thus, testing these interactions permitted us to explore whether dissonant patterns of parent–child acculturation predict cross-informant (dis)agreement in ratings of child or parenting problems.

In comparing profiles among informants, Cronbach and Gleser (1953) highlighted three types of information that need to be taken into account: elevation/level, scatter, and shape. Elevation or level information is represented by a person’s mean performance across items; scatter looks at how widely scores in a profile diverge from their means; and shape reflects where the overall profile for each person (Youngstrom et al., 2000). Different ways of measuring agreement are sensitive to different aspects of multivariate distributions. The present study evaluated agreement and discrepancies in parent and child ratings using two metrics.

First, standardized difference scores were used as an index of parent–child disagreement. Parent and child ratings on each scale were first standardized, and the standardized score of parent measure was subtracted from corresponding standardized child reported scale. Standardized difference scores were calculated separately for parental verbal punitive behavior, parental physical punitive behavior, and child internalizing and externalizing problems. The standardized difference score places both informant ratings on the same metric, adjusts for systematic differences in level or variability of informant responses, enhances the interpretability of the difference score, and correlates equally with each of the informant ratings from which it is derived (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005).

Second, to capture parent–child agreement the q correlations were computed by applying the formula for Pearson r correlations between informant pairs at the item level, indexing item by item agreement across the common item set. In terms of child problems, q correlations were computed across 31 items for child internalizing problems and 32 items for child externalizing problems. Similarly, q correlations were calculated across 5 items for parental verbal punitive behaviors and across 13 items for physical punitive behavior. Q correlations are sensitive to the shape and dispersion of the profile of item scores. Greater correlations indicate more convergence in parent and child ratings across the set of items. A zero correlation, or one near zero, indicates that parent and child ratings do not covary in any predictable, linear fashion.

Standardized difference scores and q correlations between parent–child dyads were used as indices of (dis)agreement that were then regressed on the predictor variables. Although of the metrics has strengths and limitations, using both permits an examination of different aspects of agreement (overall level or item profile).

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 displays means and standard deviations for study measures for parent and child informant reports. In paired t tests, significant differences emerged for child versus parent reports of parental punitive behavior and child behavior problems. Child-reported ratings of verbal (p<.01) and physical (p<.01) punitive behavior were higher than parent reports. In addition, child participants reported higher levels of child internalizing behavior problems than did the parents (p<.001). There was no significant difference in externalizing problems between parent and child reports. In the current sample, the level of parent–child agreement for externalizing problems (q correlation=.25) was comparable to the overall agreement of r=.25 for total behavior problems reported by Achenbach, McConaughy, and Howell (1987). However, agreement on internalizing problems in the current sample was lower (q correlation=.11). Bivariate correlations between the study variables are reported in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Main Study Variables by Informant Reports

| Variable | Child Report M (SD) | Parent Report M (SD) | t(106) | Standardized Difference Scorea | Agreement Scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Punitive Behavior | |||||

| Verbal Punitive Behavior | 14.38 (21.94) | 6.02 (11.91) | 3.57** | .00 (1.36) | .46*** |

| Physical Punitive Behavior | 8.25 (18.88) | 3.20 (6.70) | 3.15** | .00 (.95) | .79*** |

| Child Behavior Problems | |||||

| Internalizing Problems | 52.11 (10.88) | 48.48 (12.54) | 2.76** | .01 (1.14) | .11 |

| Externalizing Problems | 46.9 (10.21) | 45.57 (10.36) | ns | .00 (1.09) | .25** |

| General Variables | |||||

| Relationship Closeness | 3.70 (.65) | — | |||

| Parental Distress | — | 9.17 (.72) | |||

| Cultural Variables | |||||

| Acculturative Stress | — | 2.03 (.64) | |||

| Acculturation Conflict | 2.56 (.93) | 2.34 (.76) | |||

| Chinese Acculturation | |||||

| Public (Language/Lifestyle) | 3.42 (.72) | 3.79 (.48) | |||

| Private (Values/Orientation) | 3.08 (.64) | 3.60 (.76) | |||

| American Acculturation | |||||

| Public (Language/ Lifestyle) | 3.43 (.71) | 2.74 (.58) |

Standardized difference scores are in standardized units; agreement scores are Q correlations.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

TABLE 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Main Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 141 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Verbal Punitive Behavior – P | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Physical Punitive Behavior – P | .66** | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Internalizing Problem – P | .19* | .16 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Externalizing Problem – P | .25** | .40** | .67** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Acculturation Conflict – P | .16 | .11 | .24* | .25* | — | ||||||||||||||

| 6. Parental Distress – P | −.04 | .00 | −.12 | .14 | −.36** | — | |||||||||||||

| 7. Acculturative Stress – P | .04 | .07 | .27** | .17 | .28** | −.27** | — | ||||||||||||

| 8. Acculturation (Chinese/Public) – P | .02 | −.06 | −.15 | −.09 | .09 | −.08 | .02 | — | |||||||||||

| 9. Acculturation (Chinese/Private) – P | −.04 | −.20* | −.24* | −.28** | .01 | −.11 | −.14 | .27** | — | ||||||||||

| 10. Acculturation (American) – P | .06 | .02 | −.04 | .08 | −.05 | .15 | −.19 | −.17 | −.04 | — | |||||||||

| 11. Verbal Punitive Behavior – C | .07 | .18 | .12 | .23* | .12 | −.19 | −.04 | −.03 | −.08 | .07 | — | ||||||||

| 12. Physical Punitive Behavior – C | .30** | .55** | .06 | .16 | −.04 | −.11 | −.10 | −.08 | −.10 | .16 | .40** | — | |||||||

| 13. Internalizing Problem – C | .11 | .20* | .35** | .29** | .15 | .05 | .02 | −.20* | −.05 | .19 | .36** | .25* | — | ||||||

| 14. Externalizing Problem – C | .09 | .27** | .32** | .40** | .10 | .01 | .04 | −.04 | −.09 | .10 | .51** | .30** | .62** | — | |||||

| 15. Acculturation Conflict – C | .07 | .05 | .02 | .11 | .14 | −.06 | −.10 | .09 | .10 | −.04 | .31** | .12 | .18 | .21* | — | ||||

| 16. Relationship Closeness – C | −.12 | −.10 | −.19* | −.26** | −.36** | .13 | .01 | .02 | .19 | −.13 | −.56** | −.19* | −.39** | −.46** | −.40** | — | |||

| 17. Acculturation (Chinese/Public) – C | −.02 | .03 | −.08 | −.10 | −.10 | .12 | −.08 | .12 | −.04 | −.10 | −.13 | −.07 | −.05 | −.07 | −.24* | .22* | — | ||

| 18. Acculturation (Chinese/Private) – C | −.00 | .04 | .04 | −.04 | −.21* | .03 | −.06 | −.01 | .06 | −.16 | −.34** | −.01 | .01 | −.15 | .00 | .36** | .34** | — | |

| 19. Acculturation (American) – C | .06 | .06 | .08 | .15 | −.06 | −.02 | −.08 | −.06 | .10 | .15 | .12 | .12 | .23* | .23* | .35** | −.15 | −.05 | .35** | — |

Note. C = child; P = parent.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Multivariate Analyses

Prior to testing the major hypotheses of the study, we conducted a search for multivariate outliers using Cook’s distance and Mahalonobi’s distance (see Stevens, 1984). These results indicate that all the data appear to fit the model and should not bias parameter estimates. A series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to determine whether family relationship and cultural variables were related to parent–child (dis)agreement for each dependent variable: verbal punitive behavior, physical punitive behavior, child internalizing and externalizing problems. These analyses were run first using standardized difference scores (used as an index of parent–child disagreement) and then using q correlations (used as an index of parent–child agreement). Child age and gender, and parental distress were entered in the first step as control variables. In the second step of each analysis, the independent variable of interest was entered. The independent variables included general family context factors (relationship closeness, parental distress) and cultural variables that may be distinctive to immigrant families (acculturative stress, acculturation-related conflict, and acculturation dissonance). In the models examining of acculturation dissonance, the interaction term between child and parent acculturation was entered as the product of the two centered acculturation variables to guard against multicollinearity and spurious interactions (Aiken & West, 1991). For the regression analyses that were significant, Cohen’s f2 effect sizes were also reported: f2 of .02, .15, and .35 correspond to small, medium, and large sized effects respectively (Cohen, 1988).

Verbal and Physical Punitive Behavior

Table 3 displays the results of each of the hierarchical analysis predicting parent–child agreement and discrepancies in ratings of verbal punitive behavior. Results indicated that child perceived relationship closeness was associated with lower discrepancies (β=.21, p<.05) and higher agreement scores (β=−.32, p<.01). In terms of cultural factors, we observed a main effect for child acculturation to the Chinese culture. Child reported levels of acculturation conflict (β=.20, p<.05) was significantly related to higher standardized difference scores on verbal punitive behavior. No main effects were observed for parents’ engagement in Chinese or American culture. No significant interactions were observed for child and parent acculturation. Also, none of the family or cultural variables of relationship closeness, parent and child acculturation, acculturation stress and conflict were significantly associated with agreement or discrepancies in ratings of physically punitive parent behavior.

TABLE 3.

Associations Between General/Cultural Variables and Parent–Child (Dis)agreement on Verbal Punitive Behavior

|

Standardized Difference Score (Disagreement) |

Q-Correlation (Agreement) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | f2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | f2 | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||||

| Child Gender | .02 | .26 | −.13 | .14 | .10 | .13 | ||||

| Child Age | .13 | .04 | .29** | −.02 | .02 | −.13 | ||||

| Parental Distress | .02 | .22 | .01 | .09* | .10 | −.17 | .09 | −.20 | .07* | .08 |

| Step 2 | ||||||||||

| General Variables | ||||||||||

| Relationship Closeness | −.43 | .21 | −.21* | .04* | .05 | .25 | .08 | .32** | .09** | .10 |

| Cultural Variables | ||||||||||

| Acculturative Stress | −.20 | .24 | −.10 | ns | −.13 | .09 | −.16 | ns | — | |

| Acculturation Conflict – C | .29 | .14 | .20* | −.08 | .06 | −.14 | ||||

| Acculturation Conflict – P | −.25 | .19 | −.14 | .05† | .06 | .07 | .07 | .98 | ns | — |

| Chinese Culture | ||||||||||

| Public Domain – C | −.22 | .18 | −.12 | .28 | .45 | .41 | ||||

| Public Domain – P | −.14 | .24 | −.06 | .12 | .10 | .12 | ||||

| Interaction (Child × Parent) | .16 | .36 | .04 | ns | — | −.07 | .11 | −.38 | ns | — |

| Chinese Culture | ||||||||||

| Private Domain – C | −.25 | .22 | −.12 | .02 | .09 | .02 | ||||

| Private Domain – P | .03 | .18 | .02 | −.02 | .07 | −.08 | ||||

| Interaction (Child × Parent) | −.37 | .32 | −.12 | ns | — | .19 | .13 | .15 | ns | — |

| American Culture | ||||||||||

| Public Domain – C | .25 | .18 | .14 | −.12 | .08 | −.16 | ||||

| Public Domain – P | .04 | .23 | .02 | .06 | .09 | .05 | ||||

| Interaction (Child × Parent) | .27 | .45 | .06 | ns | — | .12 | .18 | .05 | ns | — |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Internalizing Problems

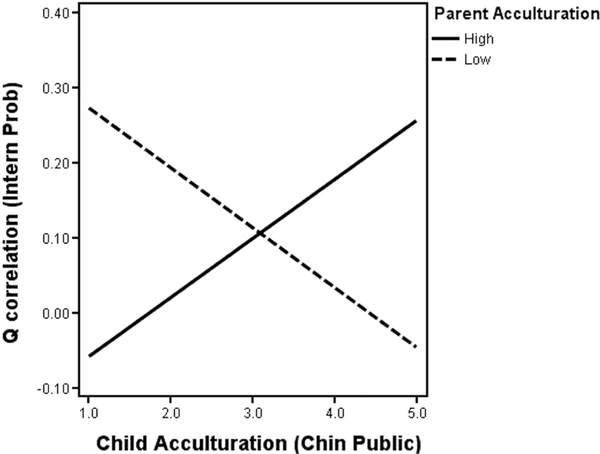

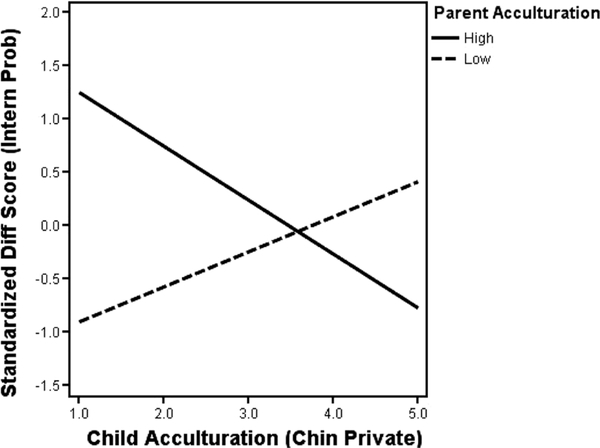

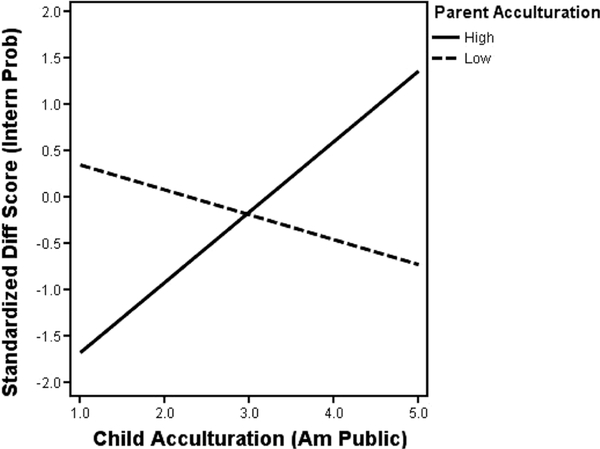

Table 4 indicates that relationship closeness was associated with disagreement in ratings of child internalizing problems (β=−.27, p<.05). Child-reported levels of acculturation conflict (β=.21, p<.05) were associated with higher discrepancy scores but were not associated with agreement scores. In terms of the cultural variables, the interaction between parent and child acculturation was significant in three regressions. First, the interaction between parent and child Chinese acculturation in public domain was significantly associated with parent–child agreement (β=.30, p<.01). As seen in Figure 1, when parents score high on Chinese acculturation in public domains, children’s Chinese acculturation was positively associated with agreement (β=.07, p<.05). At low levels of parents’ Chinese public acculturation, children’s Chinese public acculturation was negatively associated with agreement (β=−.08, p<.01). In terms of Chinese acculturation in private domain, parent acculturation was significantly associated with standardized difference score (β=.20, p<.05). Furthermore, parent–child interaction in acculturation to Chinese private domains was significantly associated with parent–child discrepancies (β=−.19, p<.05). As seen in Figure 2, children’s endorsement of Chinese values was negatively associated with discrepancy score when parents were also high on Chinese values (β=−4.52, p<.01), but this relationship was not significant when parents were low on Chinese values (β=2.47, ns). Finally, there was a significant main effect of parent American acculturation in public domain on standardized difference scores (β=.20, p<.05). Furthermore, the interaction between parent and child acculturation to American public domain was significantly associated with discrepancy scores (β=.23, p<.05). Specifically, as seen in Figure 3, under conditions of high parental American acculturation, increased child American acculturation was positively associated with standardized difference scores (β=6.49, p<.001). At low levels of parent American acculturation, child American acculturation was not significantly associated with standardized difference scores (β=−2.04, ns).

TABLE 4.

Associations Between General/Cultural Variables and Parent–Child (Dis)agreement on Internalizing Problems

|

Standardized Difference Score (Disagreement) |

Q-Correlation (Agreement) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | f2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | f2 | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||||

| Child Gender | −.07 | .22 | −.03 | .04 | .04 | .09 | ||||

| Child Age | −.01 | .04 | −.02 | .01 | .01 | .18† | ||||

| Parental Distress | .41 | .19 | .22* | .05 | — | .02 | .03 | .06 | ns | — |

| Step 2 | ||||||||||

| General Variables | ||||||||||

| Relationship Closeness | −.46 | .18 | −.27* | .06* | .07 | .01 | .03 | .04 | ns | — |

| Cultural Variables | ||||||||||

| Acculturative Stress | .36 | .20 | .20† | .03† | .03 | −.03 | .04 | −.11 | ns | — |

| Acculturation Conflict – C | .24 | .12 | .21* | −.02 | .02 | −.11 | ||||

| Acculturation Conflict – P | .02 | .16 | .01 | ns | — | −.00 | .03 | −.01 | ns | — |

| Chinese Culture | ||||||||||

| Public Domain – C | −.33 | .99 | −.05 | −.02 | .03 | −.07 | ||||

| Public Domain – P | −.12 | .22 | −.05 | .09 | .03 | .20 | ||||

| Interaction (Child × Parent) | .09 | .25 | .24 | ns | — | .22 | .08 | .30** | .12* | .15 |

| Chinese Culture | ||||||||||

| Private Domain – C | −.18 | .18 | −.11 | −.03 | .03 | −.12 | ||||

| Private Domain – P | .30 | .15 | .20* | .04 | .03 | .15 | ||||

| Interaction (Child × Parent) | −.51 | .27 | −.19* | .07* | .08 | .03 | .05 | .07 | ns | — |

| American Culture | ||||||||||

| Public Domain – C | .26 | .16 | .17† | −.04 | .03 | −.15 | ||||

| Public Domain – P | .39 | .20 | .20* | −.01 | .03 | −.02 | ||||

| Interaction (Child × Parent) | .85 | .38 | .23* | .12** | .14 | .02 | .07 | .03 | ns | — |

Note. C = child; P = parent.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

FIGURE 1.

The association between child Chinese acculturation in the public domain and parent–child q correlation on internalizing problems as a function of parent Chinese acculturation in the public domain.

FIGURE 2.

The association between child Chinese acculturation in the private domain and parent–child standardized difference scores on internalizing problems as a function of parent Chinese acculturation in the private domain.

FIGURE 3.

The association between child American acculturation in the public domain and parent–child standardized difference scores on internalizing problems as a function of parent American acculturation in the public domain.

Externalizing Problems

Child age, gender, and relationship closeness were not related to parent–child (dis)agreement. Parent report of acculturation-related conflict was associated with greater parent–child disagreement over externalizing problems (β=.23, p<.05). Parental acculturation toward the Chinese culture in the domain of private values was also associated with greater disagreement about externalizing problems (β=.23, p<.05). No main effects were observed for child acculturation or for acculturative stress or conflict.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with previous studies, we found greater concordance in ratings of overt externalizing behaviors than in ratings of internalizing problems (Achenbach et al., 1987). A significant difference in parent–child ratings of externalizing problems did not emerge. Youth in immigrant Chinese families tended to report more internalizing problems and parental verbal and physical punitive behavior than their parents. Our results indicated that general relationship and cultural factors were related to discrepancies and agreement between parent–child ratings in anticipated ways. Parent–child closeness was robustly related to smaller discrepancies in ratings of child internalizing symptoms and punitive parenting. In terms of cultural factors, acculturation related conflict was related to more disagreement in ratings of parental verbally punitive behavior, and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Furthermore, parental acculturative stress and parent–child acculturation dissonance in Chinese acculturation were related to (dis)agreement in child internalizing problems. Of importance, the observed main and interaction effects between familial and cultural factors and parent–child (dis)agreement held even after we controlled for parental distress, a parent characteristic that is robustly related to informant agreement (e.g., Youngstrom et al., 1999).

Although the direction of effect was consistent with previous literature (i.e., increased parental distress was associated with increased disagreement), the nature of response discrepancies differed from those reported in studies of mainstream samples. Scholars have contended that parents under stress tend to have lower thresholds of tolerance for child misbehavior, and thus tend to overreport pathology relative to youth (Jensen et al., 1988; Youngstrom et al., 2000). However, in our Chinese American sample, parental stress was linked not to overreporting but underreporting of internalizing symptoms relative to youth. Some have argued that ethnic minority parents may be less sensitive in identifying child mental health problems in general (Li et al., 1989). Perhaps this sensitivity is most compromised when immigrant parents are stressed and when youth problems manifest as internalizing symptoms. Parent and child acculturation to Chinese culture were largely related to (dis)agreement in predicted ways. In terms of main effects, when children were more engaged in Chinese culture there were smaller discrepancies on ratings of punitive parenting behavior, whereas discrepancies were more pronounced when parents were more acculturated to Chinese culture. Furthermore, parent–child acculturation dissonance in Chinese acculturation predicted disagreement in problem ratings, particularly regarding internalizing problems. To the extent that children and parents were matched in their levels of Chinese acculturation, their ratings of internalizing problems tended to be more similar. For example, agreement was highest when parents and children highly endorsed Chinese lifestyle or language preferences or when neither were particularly aligned with Chinese lifestyle and language preferences. In contrast, disagreement on internalizing symptoms was highest when parents were high on privately held Chinese values but youth were low on Chinese values.

Yet findings regarding differences in parent and child acculturation to American culture did not conform to expectations. There were no significant main effects of either parent or youth acculturation to American culture in predicting (dis)agreement in ratings of child and parenting problems. There was one significant interaction effect in predicting discrepancies in internalizing problems. When children and parents report higher levels of acculturation to American culture, we observed the modal response pattern where children reported more internalizing problems than their parents. However, in cases where parents reported high levels of American acculturation but youth did not, parents tended to report more child internalizing symptoms than their children. It is possible that parents being relatively more acculturated toward American norms than their children denoted greater parent mental health awareness and vigilance for child maladjustment. However, given that this is the sole finding pointing to a role of American acculturation in predicting (dis)agreement, it must be interpreted with caution.

Parent and child orientation toward the ethnic culture had stronger associations with the concordance/discordance outcomes of interest; this pattern highlights the value of differentiating between ethnic and host culture dimensions of acculturation. Costigan and Dokis (2006) noted that dissonance in the heritage culture was associated with risk of youth emotional and problems among Chinese Canadian youth but dissonance in the host culture was not. For Chinese immigrants, dissonance in acculturation to the dominant culture’s language and lifestyle may be normative and not distressing. However, retaining a shared Chinese proficiency and lifestyle may bolster communication between parents and children in profound ways, resulting in less discrepant views of child and parenting behavior. Furthermore, shared endorsement of cultural values such as filial piety and collectivism may lead to increased overlapping perceptions for what constitutes a child or parenting problem. Perspectives may diverge more sharply when there is attrition of common heritage language, activities, and values in the second generation.

The most notable pattern of disagreement in our sample suggested that immigrant Chinese parents may be less sensitive reporters of child internalizing problems, a pattern consistent with previous findings from other ethnic minority groups (Lau et al., 2004). Parents across cultures may have different “distress thresholds” (Weisz, 1989), which determine the extent to which they view certain child behavior problems as deviant, distressing, or warranting intervention. Interdependent cultures, such as Chinese societies, focus on promoting interpersonal harmony, hierarchical relationships, and family cohesion. As such, symptoms of depression, inhibition, and anxiety may be less distressing to parents as reserved behavior, cautiousness, and inhibition of impulses may be viewed as signs of maturity (Chen, Rubin, & Li, 1995). These cultural observations are consistent with the idea that immigrant Chinese parents may not be as likely to perceive, or note as problematic, such internalizing symptoms.

The pattern in which children reported more parental aggression than did their parents is also not unique to the present sample. Our results are consistent with previous findings that parents tend to underreport their own use of aggression relative to their children (e.g., Kolko, Kazdin, & Day, 1996). Parents’ general reluctance to present themselves in unfavorable terms may account for these lower self-ratings of parent aggression. However, additional cultural factors may be at play in the Chinese American context. First, such response bias and concern for social desirability may be particularly pronounced among Chinese parents where there is a strong motivation to avoid shame and prevent loss of face. Second, differential reports of parenting behavior may also be due to the fact that minority parents may hold different perceptions or thresholds for what is punitive. Chinese and Chinese American parents report greater use and approval of physical punitive behavior, yelling, and verbal admonishment (Kelley & Tseng, 1992), and these behaviors may be viewed as relatively normative. Thus Chinese American parents may have higher thresholds for defining physical and verbal aggression and in responding to questionnaires as they may access information from memory consistent with the view that their discipline behaviors are appropriate (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005).

The results of this study should be considered in light of study limitations. First, because our study was cross-sectional we cannot draw inferences about causal effects. For example, whether strained parent–child relations cause discrepancies or result from discrepancies in perspective is unclear. Longitudinal studies would help examine the bidirectional influences between relationship and cultural variables and parent–child (dis)agreement in problem perception. Second, our sample was not representative of the immigrant Chinese American population. Our sample included a majority of families who were at risk for punitive parenting and/or child behavior problems having been referred from child protective services or community mental health clinics. It is possible that parents in high-risk families were more reluctant to describe themselves or their children in an unfavorable light. Parents who were referred from child protective services may have also feared that they would be further penalized or even lose their child(ren) if they endorsed either child behavior problems or punitive parenting. We cannot conclude that our results would generalize to a general community sample. Similarly, further work should examine the extent to which our results may generalize to other cultural groups that share immigrant family processes such as acculturation dissonance and values favoring parental control over youth autonomy. Third, even though the sample included at-risk families, it is important to note that mean levels of behavior problems were within the normal range by both parent and youth report. As such, our study provides information about immigrant family parent–child (dis)agreement with regards to subclinical levels of behavior problems. It is possible that among immigrant families presenting for mental health treatment, mean levels and covariates of dispersion and item-profile agreement would differ. Fourth, the study relied on translations of measures that have previously been used with Chinese and Asian American samples, but for which extensive data on validity and reliability are lacking. Last, parent and child reports of internalizing problems differed on average by less than four raw score points on the CBCL and YSR measures. Although the difference was statistically significant, it remains unclear the extent to which these discrepancies are clinically significant. Nonetheless, the study provides new data on how cultural factors may be associated with parent–child (dis)agreement in an understudied population of immigrant families.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Findings from the current study corroborate those of previous investigations noting that youth-reported problems tend to outnumber parent-reported problems in ethnic minority families (Lau et al., 2004). Clinicians should perhaps be most vigilant about differing child and parent perspectives on child adjustment and parent behavior when working with immigrant families with first-generation parents, as acculturation dissonance and opposing cultural values may be greatest between parents and children in these families. Further, clinicians should be alert to the possibility that youth from immigrant families may be at particular risk of having internalizing problems unrecognized and untreated. Recent data suggest that racial disparities in youth mental health service utilization appear to be driven largely by higher rates of unmet internalizing mental health need among ethnic minority youth compared to White youth (Gudiño, Lau, Yeh, McCabe, & Hough, 2009) and the risk of internalizing problems going untreated is pronounced for Asian and Latino immigrant youth compared their U.S.-born counterparts (Gudiño, Lau, & Hough, 2008). As such, the triangulation of information from multiple methods and sources is particularly crucial for the identification and service allocation for anxiety, depression, and somatic problems among high-risk immigrant youth. Systematic screening efforts may be indicated in care settings where these youth present (e.g., child welfare, Limited English Proficient students in special education).

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Thus, our findings underscore the importance of reconciling reports from multiple informants when making diagnostic or treatment decisions concerning children in immigrant families. Effective strategies for bridging communication to improve the congruence between parents’ and children’s perceptions of family and youth problems may represent a crucial step in establishing a working alliance within an initial therapy orientation for immigrant families.

Acknowledgments

The conduct of this research was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01 MH66864, P.I. Lau). The preparation of this article was supported by a fellowship from the Foundation for Psychocultural Research, Center for Culture, Brain and Development to the first author. We are very grateful to the families who participated in this study for their trust and openness. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for providing helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.

REFERENCES

- Abidin RR (1995). Parenting Stress Index–Manual (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (2006). Clinical and research implications of cross-informant correlations for psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Edelbrock C (1987). Manual for the Youth Self-Report and Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, & Howell CT (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, & Kim U (1988). Acculturation and mental health In Dasen PR, Berry JW, & Sartorius N (Eds.), Health and cross-cultural psychology (pp. 207–236). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H, & Lopez SR (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist, 48, 629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, & Schwab-Stone M (1996). Discrepancies among mother, child, and teacher reports: Examining the contributions of maternal depression and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 749–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell DP, Lewinson PM, Rohde P, & Seeley JR (1997). Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 610–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Fix ME, Ost K, Reardon-Anderson J, & Passel JS (2005). The health and well-being of young children of immigrants. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Chan YC (1994). Parenting stress and social support of mothers who physically abuse their children in Hong Kong. Child Abuse & Neglect, 18, 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rubin KH, & Li B (1995). Social and school adjustment of shy and aggressive children in China. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 337–349. [Google Scholar]

- Chi TC, & Hinshaw SP (2002). Mother-child relationships of children with ADHD: The role of maternal depressive symptoms and depression-related disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 20, 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cook E, Greenberg M, & Kusche C (1995, April). People in My Life: Attachment relationships in middle childhood. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Indianapolis, IN. [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, & Dokis DP (2006). Similarities and differences in acculturation among mothers, fathers, and children in immigrant Chinese families. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 723–741. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, & Gleser GC (1953). Assessing similarity between profiles. Psychological Bulletin, 50, 456–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, & Kazdin AE (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations further study. Psychological Bulletin, 13(4), 483–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord NK, Kitzmann KM, & Coleman JK (2003). Parents’ and children’s perceptions of parental behavior: Associations with children’s psychosocial adjustment in the classroom. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3, 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE, & Ollendick TH (2002). Issues in parent–child agreement: The case of structured diagnostic interviews. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5, 37–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudiño OG, Lau AS, & Hough RL (2008). Immigrant status, mental health need and mental health service utilization among high-risk Hispanic and Asian Pacific Islander youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 37, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gudiño OG, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, & Hough RL (2009). Understanding racial/ethnic disparities in youth mental health services: Do disparities vary by problem type? Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 17, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Herjanic B, & Reich W (1997). Development of a structured psychiatric interview for children: Agreement between child and parent on individual symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD, & King CA (1996). Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among immigrant and second-generation Latino adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1183–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC (2006). Acculturative family distancing: Theory, research, and clinical practice. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43, 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Xenakis SN, Davis H, & Degroot J (1988). Child psychopathology rating scales and interrater agreement: II. Child and family characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 451–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang LP, Syed M, & Takagi M (2007). Intergenerational discrepancies of parental control among Chinese American families: Links to family conflict and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 965–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, & Tseng HM (1992). Cultural differences in child rearing: A comparison of immigrant Chinese and Caucasian American mothers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 23, 444–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Atkinson DR, & Yang PH (1999). The Asian Values Scale: Development, factor analysis, validation, and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Kazdin AE, & Day BT (1996). Children’s perspectives in the assessment of family violence: Psychometric characteristics and comparison to parent reports. Child Maltreatment, 1, 156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lau A, Garland AF, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Wood PA, & Hough RL (2004). Race/ethnicity and inter-formant agreement in assessing adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 12, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Choe J, Kim G, & Ngo V (2000). Construction of the Asian American Family Conflicts Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Leung WLP, Kwong SK, Tang CP, Ho TP, Hung SF, Lee CC, et al. (2006). Test–retest reliability and criterion validity of the Chinese version of CBCL, TRF, and YSR. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 970–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Su L, Townes BD, & Varley CK (1989). Diagnosis of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity in Chinese boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CYC, & Fu VR (1990). A comparison of child-rearing practices among Chinese, Immigrant Chinese, and Caucasian-American Parents. Child Development, 61, 429–433. [Google Scholar]

- Mena FJ, Padilla AM, & Maldonado M (1987). Acculturative stress and specific coping strategies among immigrant and later generation college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9, 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, & von Eye A (2002). The acculturation scale for Vietnamese adolescents (ASVA): A bidimensional perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, & Williams H (1989). Transition from East to West: Vietnamese adolescents and their parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Lerner JV, Lerner RM, & von Eye A (2000). Adolescent-parent discrepancies in perceptions of family functioning and early adolescent self-competence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Okagaki L, & Bojczyk KE (2002). Perspectives on Asian American development In Nagayama Hall GC & Okazaki S (Eds.), Asian American psychology: The science of lives in context (pp. 67–104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Park MS (2001). The factors of child physical abuse in Korean immigrant families. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 945–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2002). Adolescent-parent disagreement and life satisfaction in families in Vietnamese- and European-American backgrounds. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 556–561. [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Waller NG, & Comrey AL (2000). Factor analysis and scale revision. Psychological Assessment, 12, 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richters JE (1992). Depressed mothers as informants about their children: A critical review of the evidence for distortion. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 485–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES (1965). Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development, 36, 413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JP (1984). Outliers and influential data points in regression analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 355–388.6399752 [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Moore D, & Runyan D (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the parent–child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psycho-metric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22, 249–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam K, Chan Y, & Wong CKM (2006). Validation of the Parenting Stress Index among Chinese mothers in Hong Kong. Journal of Community Psychology, 22(3), 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Tang C (1994). Prevalence of spouse aggression in Hong Kong. Journal of Family Violence, 9, 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Tang C (1996). Adolescent abuse in Hong Kong Chinese families. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20, 887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tein JY, Roosa MW, & Michaels M (1994). Agreement between parent and child reports on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Ying YW, & Lee PA (2000). The meaning of “being Chinese” and “being American: Variation among Chinese American young adults.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 302–332. [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel J, Rodrigue JR, Geffken GR, Graham-Pole J, & Turner C (1994). Children awaiting invasive medical procedures: Do children and their mothers agree on child’s level of anxiety? Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 19, 723–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton JW, Johnson SB, & Algina J (1999). Mother and child perceptions of child anxiety: Effects of race, health status, and stress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR (1989). Culture and the development of child psychopathology: Lessons from Thailand In Cicchetti D (Ed.). The emergence of a discipline: Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology (Vol. 1, pp. 89–117). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Eastman KL, Chaiyasit W, & Suwanlert S (1997). Developmental psychopathology and culture: Ten lessons from Thailand In Luthar S, Burack J, Cicchetti D, & Weisz J (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder (pp. 568–592). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang HJ, Soong WT, Chiang CN, & Chen WJ (2000). Competence and behavioural/emotional problems among Taiwanese adolescents as reported by parents and teachers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, & Weisz JR (2001). Why are we here at the clinic? Parent–child (dis)agreement on referral problems at outpatient treatment entry. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 69, 1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom E, Izard C, & Ackerman B (1999). Dysphoria-related bias in maternal ratings of children. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 67, 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom E, Loeber R, & Stouthamer-Loeber M (2000). Patterns and correlates of agreement between parent, teacher, and male adolescent ratings of externalizing and internalizing problems. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 68, 1038–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, & Yeh M (2002). The use of culturally-based variables in assessment: Studies on loss of face In Kurasaki KS & Sue S (Eds.), Asian American mental health: Assessment, methods and theories (pp. 123–138). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer. [Google Scholar]