Abstract

Implementation research is dominated by studies of investigator-driven implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in community settings. However, systems of care have increasingly driven the scale-up of EBPs through policy and fiscal interventions. Research community partnerships (RCPs) are essential to generating knowledge from these efforts. Interviews were conducted with community stakeholders (system leaders, program managers, therapists) involved in a study of a system-driven implementation of multiple EBPs in children’s mental health services. Findings suggest novel considerations in initial engagement phases of an RCP, given the unique set of potentially competing and complementary interests of different stakeholder groups in implementation as usual.

Keywords: Evidence-based practice, Implementation as usual, Research community partnerships, Children’s mental health services

Introduction

System-driven implementation efforts are an increasingly common context of evidence-based practice (EBP) implementation. By 2008, 90% of state MH authorities reported strategies to install EBPs, 12 states had mandated the use of EBPs in public MH systems, with eight states promoting, supporting or requiring specific EBPs statewide (Cooper et al. 2008). Multiple system-wide roll-outs of EBPs have been launched in publicly funded systems, at the municipal (e.g., the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services; Beidas et al. 2016), state-wide (e.g., New York State Office of Mental Health Evidence-Based Treatment Dissemination Center; Gleacher et al. 2011), and national levels (e.g., the Veteran’s Health Administration; Karlin and Cross 2014). These costly efforts provide natural laboratories to identify determinants of the sustainment of EBPs, an understudied topic in implementation science (Scheirer and Dearing 2011).

However, to date, much of implementation science has been informed by studies of investigator-driven implementation, not system-driven implementation. Yet, observational studies of system-driven change may be less likely to include highly select organizations with the greatest motivation and readiness to adopt EBPs. Observational studies of system-driven implementation provide opportunities for studying more generalizable implementation processes that occur with greater independence from EBP developers and purveyors and their associated implementation “superstructures” (Hogue 2010). Rather, system-driven implementation in community mental health services has been driven by stakeholder efforts that have resulted in policy and fiscal reforms that have paved the way for scaling up EBPs. These implementation contexts often include simultaneous implementation of multiple EBPs and have involved stakeholders at multiple levels (e.g., system-leaders, third-party payers, agency-leaders, front-line providers, and EBP developers and purveyors).

Role of Research Community Partnerships (RCPs) in Implementation Research

Implementation research is thought to necessitate strong research-community partnerships (Proctor et al. 2009). In the context of investigator-driven implementation efforts, RCPs have typically incorporated aspects of community-based participatory research (CBPR). Principles of CBPR emphasize active involvement of community members, organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process, the mutual exchange of expertise among these parties, and processes to ensure shared decision-making (Israel et al. 2005, 1998). An outgrowth of CBPR specifically developed to guide collaborative efforts to implement EBPs in community-based mental health services is community-partnered participatory research (CPPR; Jones and Wells 2007). The main objective of CPPR is to ensure that EBPs are deployed in ways that align with community priorities, needs, and values (Wells et al. 2004), particularly in selecting, adapting, and testing the implementation of EBPs in community practice settings.

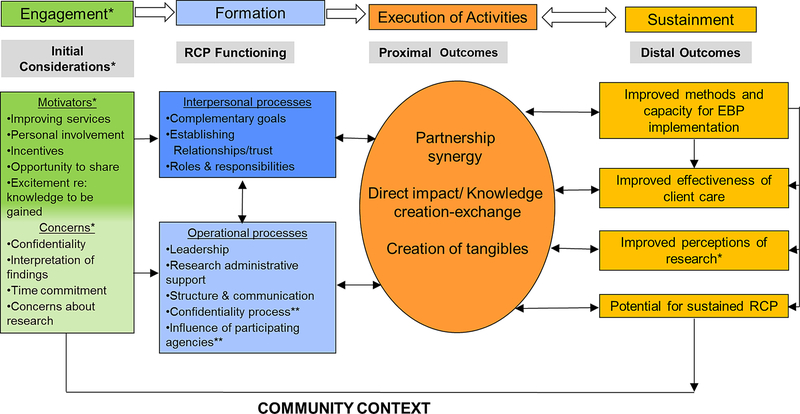

Drawing from experiences conducting community partnered research and the literature from multiple disciplines, including business management, organizational learning and knowledge management, community health partnerships, and community-based participatory research (Butterfoss and Kegler 2002; Weiss et al. 2002), Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) and Garland and Brookman-Frazee (2015) outline a conceptual model of research community partnerships as applied to mental health services and implementation research. This model highlights the iterative and dynamic process of RCP development and posits that positive RCP functioning can lead to partnership synergy which, in turn, can result in a variety of distal outcomes, including benefits to individual partners and organizations involved in the RCP as well as the broader community. (1) In the partnership formation stage, the goal is to establish strong RCP functioning including interpersonal processes centered on building relationships and trust and clarifying roles and responsibilities, and operational processes that guide expectations for shared leadership, structure, communication and administrative support. (2) During the execution of partnership activities, a number of proximal outcomes are anticipated including partnership synergy that results in knowledge creation and exchange, and the production of tangible collaborative products. (3) Finally, in the sustainability stage, distal outcomes can be assessed and monitored for individuals, organizations and communities, including a lasting infrastructure for ongoing and future collaborations.

This model was informed by specific case examples of community partnered research. For example, the Southern California BRIDGE Collaborative (Stahmer et al. 2011) represents one example of an RCP developed based on CBPR and CPPR principles that brought together a transdisciplinary team of front-line service providers, funding agency representatives, researchers, and families of children presenting with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to develop a community-wide, sustainable plan for serving at-risk infants/toddlers. Furthermore, Garland and Brookman-Frazee (2015) applied the model to the “Practice and Research: Advancing Collaboration (PRAC)” Study to illustrate the components of model within a multi-year research-practice partnership developed to support observational research on publicly-funded outpatient psychotherapy for children and families.

Building upon this model, and the BRIDGE and PRAC case studies, Brookman-Frazee et al. (2016b) carried out a survey of researchers and community partners involved in 18 RCPs developed to select and adapt EBPs and implementation strategies for child service systems. Surveys were completed by principal investigators and community partners enumerated from published research articles and funded grant proposals describing RCPs in children’s services. Results indicated that RCPs were typically initiated and formed by researchers, with interpersonal and operational processes perceived as the primary challenges to the collaborative process. Community partners were usually involved in implementation and participant recruitment rather than in front-end decision making and agenda setting. Yet, the RCP process was perceived by both stakeholder groups to increase both the relevance of research and the fit of EBPs for community practice settings.

In their systematic review, Drahota et al. (2016) applied the RCP model constructs in their examination of 50 studies describing community-academic partnerships across disciplines and noted that the most common facilitating factors were positive interpersonal processes of trust, respect, and strong relationships among partners. However, the most frequently cited challenges were excessive time commitment and a lack of clarity concerning leadership, roles and responsibilities among the partners. The focus of the partnerships was typically on the proximal outcome of the development of products (e.g., proposals, pilot studies), but few studies reported on distal outcomes associated with sustained collaboration or improved infrastructure.

Gaps in RCP Research and the Unique Context of Implementation-as-Usual

This paper addresses the unique context of developing RCPs in the context of observational implementation studies that seek to examine the process and outcomes of system-driven efforts to scale up EBPs. With few exceptions, the prior research and theory on RCPs emphasizes partnership processes and outcomes observed primarily in investigator-initiated implementation efforts. However, system-driven implementation efforts are characterized by community stakeholders at the helm of decision-making about EBP selection, adaptation and implementation strategies. In this context, researchers wishing to study implementation must develop RCPs to carry out observational studies of EBP implementation-as-usual. There is a lot at stake for community partners when researchers enter systems to study implementation process and outcomes in large-scale, system-driven reform efforts as they involve major investments of resources. Accordingly, there may be a range of motivations and concerns and interests regarding engagement in observational implementation research among community stakeholders.

Study Context

This study draws upon the first three years of experience in conducting the NIMH R01-funded study, “Measuring the Sustainment of Multiple EBPs Fiscally-Mandated in Children’s Mental Health Services”, known locally as the Knowledge Exchange on Evidence-based Practice Sustainment (4KEEPS) study. 4KEEPS is designed to identify predictors of the sustainment of multiple EBPs being implemented within a large system-driven reform of public children’s mental health services (Brookman-Frazee et al. 2016a; Lau and Brookman-Frazee 2016). The Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health (LACDMH) Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) reform effort involved a fiscal mandate that required agencies to deliver one of 52 approved practices (EBPs and interventions supported by community-defined evidence) for reimbursement through a new state revenue funding source. The 4KEEPS study is examining inner context factors (therapist and agency-level factors) that predict sustained used of six child mental health practices that received system-level implementation support at the outset of the transformation.

This study involves community partners from the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health (LACDMH) and large-scale quantitative and qualitative data collection from close to 1000 participants (program manager and therapist surveys and interviews, session-level implementation data). We have engaged stakeholders of multiple types and levels (System Leaders, Program Manager Agency Leaders, Therapists) to conduct the study, interpret study findings, and plan for next steps in this research. However, the process and nature of engagement has differed by stakeholder type. LACDMH system leaders were partners in the project proposal development and research design, playing an instrumental role in: (a) shaping the research aims and activities, (b) reviewing and approving study protocols, (c) furnishing system-level data, (d) facilitating access to provider agencies, (e) advising on recruitment and data collection procedures, (f) providing information about the system context to aid in interpreting data, and (g) facilitating ongoing dissemination of findings. Agency leaders/program managers may be best described as participant-partners in the research: (a) acting as participants in surveys and interviews, (b) approving and co-planning operational aspects of data collection at each site, and (c) facilitating access to therapists and supporting recruitment. Therapist stakeholders are primarily involved: (a) as participants in surveys, interviews and in provision of data on EBP delivery at the session level; and (b) in obtaining permission from families to audio record sessions. A subset of agency leaders and therapists were members of a community advisory board who provided feedback on multiple topics related to engagement. The intensive and ongoing engagement processes used in this observational implementation study provide an opportunity to examine the motivations of these stakeholders to partner with the investigators (and each other) to achieve study goals.

Study Purpose

The purpose of this study is to describe the process of research-community collaboration within a system-driven implementation of multiple EBPs for children and families and to characterize the competing and complementary interests among community partners from a variety of stakeholder types. This was a time-limited supplemental study activity to contribute to the aims of an implementation science training institute from parent projects initially conceived within the institute. The scope included a modest original data collection effort to be carried out using rapid qualitative assessment methods. We drew from constructs in the Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) and Brookman-Frazee et al. (2016b) research community partnership framework and aimed to elaborate on new and distinctive features of RCPs formed within observational research involving system-driven implementation-as-usual that highlight potential tensions and risks to different stakeholder groups and methods to negotiate these tensions.

Method

Participants and Procedures

A total of 27 semi-structured interviews were conducted with individuals from three stakeholder group (system leaders, program manager/agency leaders [PMs], and therapists) that were associated with the LACDMH PEI transformation and the 4KEEPS Study. Stakeholder participants had previously participated in the study in varied capacities, described next. Participant demographics for PMs and therapists are reported in Table 1. Note that there were no statistically significant differences on demographic variables between both those that participated in the interview and the full sample invited to participate. System leader demographic information has been purposefully limited to preserve anonymity of respondents.

Table 1.

Participant demographics for therapists, program managers, and system leaders

| Therapist (n = 10) | PM (n = 12) | System leaders (n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: M (SD); range | 35.60 (8.81); 26–55 | 45.42 (11.24); 30–68 | – |

| Female (%) | 9 (90%) | 10 (83.3%) | 4 (80%) |

| Race/ethnicity n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3 (30%) | 5 (41.7%) | – |

| Latino/hispanic | 5 (50%) | 3 (25%) | – |

| African American | 1 (10%) | 1 (8.3%) | – |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (10%) | 3 (25%) | – |

| Licensed n (%) | 3 (30%) | 8 (100%) | – |

| Degree n (%) | – | ||

| Master’s degree | 9 (90%) | 10 (83.3%) | 1 (20%) |

| Doctoral degree | 1 (10%) | 2 (16.7%) | 4 (80%) |

Sampling and Recruitment Procedures

Within the constraints of a time- and resource-limited inquiry, we targeted a small sample of PMs and therapists and all the system leaders who had a partnering role in the study. A total of 50 participants (25 PM and 25 therapists) were randomly selected from a larger pool of participants in the 4KEEPS In-Depth study (43 PMs, 95 therapists) and invited to participate via email. The email invitation to PMs and therapists included information on study participation and provided a link to an online consent form and an online scheduling tool to arrange a phone interview within two weeks of the invitation. The scheduling tool remained open until all interview slots were filled, and resulted in a sample of 12 PMs and ten therapists. Eligible PM participants were involved in a previous 4KEEPS study interview, while therapist participants completed a similar interview and participated in audio-recording of client/family therapy sessions and questionnaires pertaining to each session. All five system leader participants were selected to participate based on their leadership role in LACDMH and involvement in the 4KEEPS study. System leaders were emailed individually and scheduled for in-person interviews.

System Leaders

All five system leaders who were invited to participate completed the interview (response rate = 100%). Participants were predominately female (80%) and 40% were Non-Hispanic White.

Program Manager Agency Leaders

A total of 12 PMs signed-up and completed the interview (response rate = 48%). They all held a managerial role at their respective clinical sites or agencies (e.g., practice-specific agency supervisor). Participants were 83% female and 42% Non-Hispanic White, per self-report.

Therapists

A total of ten active therapists signed-up and completed the interview (response rate = 44%; one therapist responded to the email but was late to sign-up for an interview time). Participants were on average 35.5 years of age (SD = 8.81), 30% Non-Hispanic White, and 90% female.

Qualitative Interview

Semi-structured interviews were conducted over the phone (therapists and PMs) and in-person (system leaders) over a two-week period by the second author, who was not involved in previous 4KEEPS study activities. Interview duration was approximately 30 min. An interview guide was developed to collect information about participants’ experiences with the research-community partnership and process, with a focus on identifying competing and complementary interests among the three stakeholder types. However, not every informant provided information on every topic since the intention was to allow informants to elaborate or focus on issue s/he considered most important. The interview focused on understanding the following constructs:

Initial motivations and interests to partner in the 4KEEPS study (e.g., What influenced your initial interest in the study?)

Potential risks and costs of the knowledge to be gained or engagement in the process (e.g., What were your initial concerns about engaging with the researchers in this study?)

Maximizing benefits and minimizing risks (e.g., What about the collaborative process helped to manage potential risks or unintended consequences?)

Impact of involvement on stakeholders. (e.g., How has your involvement impacted you or your agency?)

Generating directions for next steps in 4KEEPS research (e.g., What do you think is an important next step based on process and findings from 4KEEPS?)

Data Management and Analysis

All interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed. Transcribed documents were randomly selected for review of accuracy by the original interviewer cross-referencing the transcriptions to the audio recordings. A stepwise development of the coding system was employed for coding and analysis of documents based on a “coding, consensus, and comparison” methodology consistent with conventional qualitative methods in implementation and mental health services research (Hamilton et al. 2015; Palinkas 2014; Willms et al. 1990). Consensus processes allow for an iterative refinement of code definitions and the logic of the coding tree, as well as collaborative development of themes (Hamilton et al. 2015; Palinkas 2014).

We started with a codebook developed by investigators based on a priori concepts informed by the RCP model outlined in Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012), an initial review of the interview transcripts, and the logic of the interview guide. The initial codebook contained 23 initial codes, definitions, guidelines for use, and examples of representative quotes appropriate to each code. The codebook was developed by the authors to map constructs related to the Research-Community Partnership (RCP) framework described by Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) and Brookman-Frazee et al. (2016b) to characterize engagement processes and outcomes. Three interview transcripts were coded by the second author with consultation from the first and last authors to further refine definitions of codes.

Training for coders (three post-baccalaureate research assistants and one doctoral student) involved two didactic training sessions focused on reviewing core concepts of RCP, reviewing the coding manual, and practice coding of previously coded transcripts. The senior coder provided feedback on practice coding. Coders then independently coded four to eight randomly selected transcripts. The second author reviewed all 27 coded transcripts for coding accuracy and consistency and met regularly with the coders to resolve questions and disagreements. Following completion of independent coding and consensus meetings between authors and coders, the final codebook included 23 final codes (two emergent codes were added, and four existing were collapsed into two).

The NVivo (QSR International 2012) qualitative analysis software program was used to analyze data through coding, development of categorical “nodes” consisting of related units of text, and aggregation of codes through the process of review and comparison in order to identify emergent themes and to ensure systematic analysis of coded data (Version 10; 2012). Through this process, 24 themes emerged related to the RCP framework. Analyses focused on identifying themes that were salient within RCP phases and processes and on identifying complementary and competing themes across stakeholder group perspectives.

Results

Refer to Table 2 for a summary of themes and representative quotes for each stakeholder group, organized according to the Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) framework specifying the formation (i.e., research-community partnership functioning), execution of activities (i.e., proximal outcomes), and sustainability (i.e., distal outcomes) phases. All three phases emerged as relevant concepts for the three stakeholder types in describing their experiences with the collaborative partnership/engagement process and outcomes. Exploratory analyses comparing responses by stakeholder type generally suggest that interests and concerns about engaging in the RCP varied somewhat across the three stakeholder groups (see Table 2). Below we organize themes by RCP phase and we follow with a summary of patterns of convergence and divergence of perspectives across stakeholder groups. There were three prevailing patterns of shared vs. unique themes: (1) organizational (shared among PMs and therapists), (2) leadership (shared among PMs and system-leaders), (3) and system (salient only among system-leaders).

Table 2.

Key themes in 4KEEPS study engagement by RCP phase and stakeholder type

| RCP phases | Stakeholder group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TH | PM | SYS | ||

| Engagement phase: initial motivations and concerns | ||||

| Initial Motivations* | Quality Improvement* | ✓ | ✓ | |

| “How do we sustain these practices?…it would give us a much fuller picture of the different layers: The training, the actual clinical service, the supervision, the support, the sustainability. And give us, as the department, an opportunity to address and make changes or to learn and be able to do a better job.” [system leader] | ||||

| “Just in improving services, making sure that staff—fidelity to the model is a strong one for me, sticking to the model.” [therapist] | ||||

| Personal involvement/role in PEI history* | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “We were in the heart of it because we were doing the PEI outcomes piece…and it would be really interesting to hear the input from the people who are definitely doing the work out there.” [SYSTEM LEADER] | ||||

| Concrete Incentives* | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “Well, and I got an iPod touch out of it… That’s a really good motivating factor…” [therapist] | ||||

| Opportunity to share* | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “I sort of, in my heart, kind of resisted them [EBPs] a little bit just because from where I sit, a lot of times, research can be really biased… we’re working with different populations…so the chance to speak on the other end of it for this study was interesting to me…” [therapist] | ||||

| “..a really unique opportunity to have your voice heard in a confidential way that wasn’t coming from the program leadership or [DMH], but was an opportunity to do real talk around what this experience has been like.” [PM] | ||||

| Excitement with knowledge to be gained* | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “I was interested to see just how effective people have found all these EBP’s that we’ve used since 2009…it’s been seven years in the making and I just wanted to see, across the board in LA County, all the different agencies, what the results looked like.” [PM] | ||||

| “…to see what their [clinicians] buy-in is to the evidence-based practices was what they like, what they didn’t like…” [SYSTEM LEADER] | ||||

| Initial Concerns* | Confidentiality* | ✓ | ✓ | |

| “The biggest one for me, of course, was client confidentiality. I didn’t want to make my clients feel uncomfortable about taping their sessions. I didn’t want it to impact treatment in any way.” [therapist] | ||||

| Interpretation of findings* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| “To get a view from, you know, 30,000 feet versus one view…you have to understand the whole system… I think there’s a context that has to be understood about LA County’s implementation…and I think understanding that context and communication about what was happening and why things were happening and attitudes…” [system leader] | ||||

| “I think there’s been other research projects where there have been generalizations or assumptions made about the data that weren’t exactly true…when you’re giving data to someone, there’s always a risk of misinterpretation of the data…” [system leader] | ||||

| “… is there going to be a negative feedback coming to my boss or something maybe like that…” [therapist] | ||||

| Time commitment* | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “it [study participation] creating extra work for clinicians, time away, additional time on top of their already heavy caseloads…” [PM] | ||||

| Skepticism of Research* | ✓ | |||

| “many of us who grew up in minority communities, we’ve seen… universities and other folks come out and then they have all this activity going on and then there’s nothing—once they get what they want, then they just leave the community…Who really benefits from this?” [System leader] | ||||

| Formation phase: RCP functioning | ||||

| Interpersonal Process | Complementary/aligned goals | ✓ | ✓ | |

| “my job…whatever decisions we make here, it’s really with the intent of having the best possible services for the clients that we serve and I think this study is part of that; looking to be able to have the best possible services…” [system leader] | ||||

| “There was some times where I think they may have been concerned that we were trying to sway their study.” [system leader] | ||||

| “… [the study] gave us a really good opportunity to have a partnership that’s really aligned and accurately reflecting what we’re actually doing. I think it helps reinforce to our agency the importance of being involved in our university partnerships.” [PM] | ||||

| Establishing relationships and trust | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “I feel like they were very transparent and clear in their initial presentation that made the process very seamless…I feel like the structure of the study, the friendliness of the staff, the transparency of the staff…” [PM] | ||||

| “They get public mental health and so it doesn’t feel like there is such a divide between the university and our department and they’ve been very respectful of process and, you know, IRBs and all those sorts of things…” [system leader] | ||||

| Roles and responsibilities | ✓ | |||

| “We went through a dialogue where we talked about, ‘What is it that you need? What are the questions that you’re trying to answer? Is it what you want?’ And then, we kind of would go through our data elements and say, ‘I think this might meet your needs.’ And they would go back and study and say, they looked at our codes and all of our data dictionaries, things like that, and they said, ‘These are the things that we need.’ …so, it was kind of a back and forth…” [system leader] | ||||

| Operational processes | Leadership/power structure | ✓ | ||

| “…having conversations—a dialogue—and for them to be able to ask us questions and then for us to support—like a process back and forth.” [System Leader] | ||||

| “[Initially] I think that was we didn’t know how it was set up, what the structure was for it, and suddenly, it’s ready to go. It’s like, ‘Oh, great, this was supposed to be a collaboration, and we knew nothing about it’…” [system leader] | ||||

| Research administrative support | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “I felt they were extremely organized and efficient…made the process very seamless.” [PM] | ||||

| Structure and communication | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “–it’s definitely when [PIs] …presented some of the data and started showing us…what they’re finding has been really helpful…” [system leader] | ||||

| Confidentiality process* | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “I think really explaining to them [families and clients] that it was going to be kept confidential and…how the information was going to be used—let them know that none of their personal information was going to be released…and how things are sort of averaged out, and not used individually, and how things are kept for research in general.” [therapist] | ||||

| Organizational buy-in and support* | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “…we got our executive leadership team to have buy-in, and then they supported it, which always helps with staff supporting it…” [PM] | ||||

| Execution of activities phase: proximal outcomes | ||||

| Proximal Process Outcomes | Partnership synergy/collaborative relationships | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| “A lot of our previous or current [research] involvements have had a missing link, in that it’s not necessarily always applicable to the community that we serve or to the complexities of LA County. 4KEEPS is really unique in that way; it gave us a really good opportunity to have a partnership that’s really aligned and accurately reflecting what we’re actually doing. I think it helps reinforce to our agency the importance to keep being involved in our university partnership.” [PM] | ||||

| “…having conversations—A dialogue…, back and forth. I think when you start working on a project with people, you get to know them a little bit and you get to feel a little bit more comfortable—public mental health partnership—that they were bringing something to our work that was ultimately going to make it better.” [System Leader] | ||||

| Direct impact/knowledge creation-exchange | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| “… [more] mindful of how and why I’m choosing interventions for my clients…” [therapist] | ||||

| “It’s just a good reminder that sometimes, we skew away from how the EBP is supposed to be practices, and…I think it’s just reminding us that ‘Oh, this is the way it’s supposed to be done.’” [PM] | ||||

| “I think it raised my consciousness and awareness of an approach and… implementation science…” [system leader] | ||||

| Creation of tangibles | ✓ | |||

| “…quarterly PEI provider meetings—it provided updates. And they were very engaging updates and I had thought that that is really good modeling; you know, in terms of: this is what we’re learning and this is how you can apply it…” [system leader] | ||||

| Sustainment phase: distal outcomes | ||||

| Anticipated outcomes | Improved or new methods for EBP implementation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| “I think it’d be interesting to look at the culture of each clinic. How do the clinicians interact with the supervisors? How do the supervisors see the clinicians?” [therapist] | ||||

| “…teasing out how to support the clinician in truly implementing effective treatment without putting more burdens on them, because it seems like the bottom line is always the therapists, and everything gets dumped on them…” [therapist] | ||||

| “Then I would be better informed about what kind of changes maybe our agency needs to make… how can we train our clinicians, serve our families, in different ways that maybe other agencies have found to work…” [PM] | ||||

| “…information to be shared with the trainers, with the original founders of the EBPs. Also obviously the Department of Mental Health…that would be…the next step so that it’s not just this one-sided participation…actually institute some changes…” [PM] | ||||

| “…we’d like to…measure the change…in how clinicians view outcomes…what we keep saying is that, ‘It’s not another piece of paperwork [it] informs your clinical practice.’… I would be curious to see as we’re making more efforts and training for people to understand the importance of it…” [system leader] | ||||

| Improved effectiveness of care for clients | ✓ | |||

| “…strategize about making sure our clients get better services, making the system better, more responsive” [system leader] | ||||

| Potential for sustained research-community collaboration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| “We enjoy working with you guys, and whatever we can do to try to help you out, we’re more than welcoming doing that…”[PM] | ||||

| Improved perceptions of research* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| “…it’s impacted it very positively… I’ve had many experiences where researchers are difficult to get a hold of, or have unrealistic expectations, or aren’t as heavily incentivized…and my experience with 4KEEPS was very positive and low-impact…” [PM] | ||||

| “… other ones [studies], we just got a request that was just like, ‘Give us everything all the time on everybody,’ and it was like, ‘No more. You can’t do that…’” [system leader] | ||||

Therapist n = 10; Program Manager (PM) n = 12; System leader n = 5

= themes that expand upon the RCP model in Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) and Brookman-Frazee et al. (2016)

✓ = Salient Subtheme

Engagement Phase

This phase was not in the original RCP framework but was added for this context based on consistent themes that emerged in response to interview questions about participants’ initial motivations and concerns associated with initial engagement in the study activities. The highest proportion of all coded comments were related to initial considerations for engaging in the research activities for each group: therapists (30%), PMs (33%) and system leaders (24%), however the salience of the five initial motivators and four initial concerns differed by stakeholder group.

Initial Motivators

In terms of initial motivators, two themes emerged as salient among leadership (PM and system leaders): quality improvement, personal involvement in the PEI transformation, and excitement about discoveries that could be made through the RCP.

Motivators: Quality Improvement

Although all stakeholders made comments about improving services as a major motivator for participating in the 4KEEPS study, this motivation was most salient for PMs and system leaders. PMs reported that having their program participate had the potential to indirectly improve mental health services through findings regarding therapist training/fidelity and barriers associated with client-intervention fit. System leaders also highlighted improving services as impetus for collaborating with the researchers on the study. Specifically, they commented on their desire to understand the sustainment of practices and reported appreciating the benefits of gathering multi-dimensional perspectives to best improve those services.

Motivators: Personal Involvement or Role in PEI History

PMs and system leaders more frequently and extensively discussed this motivation than therapists. System leaders noted their perspectives were critical to the study given their role in the PEI transformation process and ongoing leadership in PEI implementation and outcome monitoring. Multiple PMs also highlighted their motivation to share their unique perspectives afforded by their own evolution from a therapist role through their later transition to supervisorial/managerial roles during the period of the PEI transformation. Thus leadership at the system and organizational-levels expressed that their participation in RCP related to their felt personal investment in the community-lead implementation effort.

Motivators: Excitement with Knowledge to be Gained

PMs and system leaders described the appeal of the knowledge to be gained through the study as an important influence to participate. Perceptions about the relevance of the study resonated with many PMs and they expressed curiosity about implementation efforts used in other agencies. System leaders expressed particular interest in understanding community therapists’ attitudes and perceptions about the EBPs across agencies.

Two distinctive motivations were shared by organizational-level participants (therapists and PMs): participation in the RCP provided an opportunity share about implementation experiences, and involved tangible participant incentives.

Motivators: Opportunity to Share

Therapists and PMs frequently and extensively described the opportunity to share their experiences as a motivator to participate in the study. Therapists talked at length about valuing the platform offered by the study to anonymously provide feedback and input based on their personal experiences and challenges faced within the mandated EBP implementation. Similar to therapists, PMs consistently discussed their desire to share their unique managerial perspectives about the PEI transformation and highlighted the opportunity provided by the neutrality of the study. Comments reflected the importance of being given a voice to discuss experiences about a system-driven reform and changes to practice that were mandated rather than chosen.

Motivators: Concrete Incentives

Although not discussed in great depth, organizational participants (therapists and PMs) cited tangible incentives (i.e., gift cards and iPod devices) as important to facilitating therapists’ decisions to participate in the study.

Initial Concerns

In terms of initial concerns about engaging in the RCP, two concerns were shared by organizational participants (related to time burden and patient confidentiality), while only system leaders shared particular concerns about past negative experiences with researchers that created some mistrust. All stakeholder groups expressed having initial concerns about potentially unfavorable or unfair interpretations of research data and findings.

Concerns: Confidentiality

PMs and therapists described having initial concerns that client/families would be apprehensive to audio recording their therapy sessions. They also expressed concerns about the impact of the recording on therapy sessions (e.g., client behavior).

Concerns: Time Commitment

Both PMs and therapists discussed having initial concerns about the time commitment required for therapists to record and report on sessions. PMs expressed concern that study participation would provide extra work for clinicians and reported this to be an initial barrier in therapist recruitment. Therapists noted that time was an initial concern and described needing to manage and organize their time and data collection efforts.

Concerns: Skepticism of Research

Most system leaders commented on concerns about collaboration with 4KEEPS researchers based on negative past experiences with researchers and universities. This initial concern was not raised by therapists and PMs.

Concerns: Interpretation of Findings

Although respondents from each stakeholder group mentioned concerns about the interpretation of study findings, this was most salient for system leaders. System leaders emphasized concerns about the potential lack of context or overgeneralizations made when project findings would be interpreted and disseminated. The comments from organizational participants (PMs and therapists) reflected concerns that data on therapist EBP delivery might be evaluated negatively by researchers or shared with agency supervisors or system higher-ups for evaluation of therapist competency (e.g., fidelity checks).

Formation Phase: RCP Functioning

Interpersonal Processes

The Interpersonal processes pertain to characterizations about interpersonal factors involved in engagement with researchers. Most comments regarding interpersonal processes were provided in response to interview questions about maximizing the benefits and minimizing risks of engaging in the 4KEEPS study. Although members of all groups commented on interpersonal processes, a greater proportion of comments about this topic emerged in interviews with leadership (system leaders [19%] and PMs [12%]) than among therapists (7%).

Complementary or Aligned Goals

Leadership commented on complementary or aligned goals, although they differed in the extent to which they viewed their goals as aligned with the researchers over time. System leaders commented that they were initially uncertain whether their goals were aligned with researchers (e.g., they were aware that the researchers presented the study to prospective participants as being independent from an LACDMH agenda). They described that differences were resolved over time by focusing on shared goals to improve child mental health services. PMs, on the other hand, described congruency with the study goals throughout their involvement in the study, highlighting that there was a shared goal to characterize barriers to EBP implementation and they viewed the study as the “missing link” in elucidating these challenges.

Establishing Relationships and Trust

PMs commented extensively about the role of the researchers’ interaction style facilitating trust and collaboration. Specifically, they mentioned that researcher transparency and clarity with study goals fostered trust and mitigated initial trepidations about participating in the study for PMs and therapists alike. Some PMs discussed that consistent visibility of study personnel in their clinical setting and reassurance from study staff about the neutrality of the project were pivotal to cultivating trust throughout the course of their participation. System leaders commented that the researchers creating a respectful environment for the collaboration was essential to the relationship, and appreciated the researcher’s understanding of the public mental health system.

Roles and Responsibilities

Processes related to roles and responsibilities were only found among interviews with system leaders who commented on the importance of having ongoing meetings with the research team that allowed for a dialogue to provide input and exchange ideas on data collection, data requests, and interpretation of findings.

Operational Processes

The Operational processes pertain to characterizations about operative factors (e.g., leadership, research administrative support) important to engaging with the study. A similar proportion of comments about this topic was found across system leaders (18%), PMs (17%) and therapists (16%), although the most salient aspects of operational processes differed by group. System leaders were the only stakeholder group to discuss themes of power sharing in the RCP. Leadership across the agency and system-levels discussed the importance of close communication and regularly structured meetings to recursively share findings with the research team. At the organizational-level, therapists and PMs specified multiple operational processes as integral including safeguards for confidentiality, agency-level buy-in and facilitative actions, and research team logistical support.

Leadership and Power Structure

This area was most frequently and extensively discussed by system leaders. Perceptions focused on the constructive method for decision-making and power structure following early tensions during initial study planning. Respondents commented specifically about the research team unintentionally omitting key DMH leaders from initial decisions in study planning. However, once the appropriate people were involved in ongoing dialogue and conversations, the decision-making process was perceived as appropriate.

Structure and Communication

System leaders and PMs frequently described the structures used to facilitate communication and execute project activities. Positive evaluation of the initial communication efforts by researchers were described as supporting engagement in the study. System leaders emphasized that consistent in-person meetings with lead researchers resulted in the greatest impact on collaboration. Additionally, ongoing communication in the context of sharing preliminary findings with all stakeholders motivated system leaders to sustain the partnership.

Confidentiality Process

This is a new operational process that was added to the RCP model for this research context. Organizational participants (therapists and PMs) frequently discussed the importance of the process of maintaining confidentiality. They described logistical steps to ensure client confidentiality (e.g., de-identified recordings) and the importance of clearly communicating to clients about confidentiality of recordings.

Organizational Buy-in and Support

The extent to which participating agencies demonstrated buy-in and involvement in study activities was a new operational process that was added to the RCP model for this research context. Comments about safeguards or study endorsements from agencies were most salient for PMs. They discussed several efforts put in place by agencies to support the participation of therapists and PMs. For example, when agencies scheduled the study recruitment activities during regular standing staff meetings this reduced time burden for therapists and fostered participation. The balance between agency leaders encouraging participation while also affirming the voluntary-non-evaluative nature of the study was regarded as helpful by therapists.

Research Administrative Support

PMs most frequently described the benefits of research administrative support for therapist participants. They expressed appreciation for the support that the research team provided to therapist participants (e.g., being onsite to collect materials and trouble shoot) and flexibility to schedule study activities. Multiple therapists also noted that logistical support (e.g., reminder emails) was helpful for them to complete study activities.

Execution of Activities Phase

Proximal (Process) Outcomes

Proximal study outcomes include partnership synergy (evaluations of the collaborative process), immediate and direct impacts of the research activity, and the creation of tangible products. The proportion of coded comments for each group was as follows: therapists (21%), system leaders (16%) and program managers (15%). All three stakeholder groups discussed themes of partnership synergy and direct impacts related to knowledge, but only system leaders discussed tangible products of the research.

Partnership Synergy and Collaborative Relationships

Overall, PMs and therapists described the whole process of engaging in the research as a positive experience. PMs often expressed a desire to continue to collaborate and encouraged others to participate. System leaders acknowledged initial partnership challenges that were later managed through ongoing communication that eventually resulted in a positive relationship.

Direct Impact and Knowledge Creation-Exchange

Both PM and therapist respondents described their participation in the research as having direct positive impacts on their work. Specifically, PMs and therapists commented on increased awareness related to therapist fidelity due to the session recording activities involved in the study, and increased reflection on decisions on EBP selection for client groups. Therapists also talked about feeling “heard” and empowered to share their experiences. System leaders expressed increased awareness of implementation science and motivation to apply what is learned through the study. A strong theme from system leaders was the positive impact of collaboration on the research; there were a number of comments that preliminary findings validated stakeholders’ anecdotal observations.

Creation of Tangibles

System leaders most frequently discussed the creation of tangible products such as publications and community presentations. System leaders highlighted the importance of having the research team consistently produce and disseminate updates and presentations for leaders of contracted agencies.

Sustainment Phase

Distal Outcomes

Distal outcomes include themes about expected effects of the study including improved methods for EBP implementation, improved effectiveness of client care, sustained RCP, and improved perceptions of research/ers. Comments about distal outcomes represent a similar proportion of all coded comments across stakeholder groups: Therapist (26%); PM (23%); system leaders (23%).

Improved or New Methods for EBP Implementation

Expected improvements or strategies to support EBP implementation were described frequently, but distinctly, by all stakeholder groups. Content of stakeholder responses appeared to vary based stakeholder’s role within the decision/power hierarchy of the county mental health system. Respondents from all groups described expecting to learn about the challenges faced in implementing EBPs. PMs wanted to learn about challenges faced by agencies in LA County that might inform their respective agencies. Therapists also reported wanting to learn from other agencies about agency culture and supervisory differences. System leaders also described their desire to gain knowledge about clinician experiences with the PEI transformation with the goal of informing future mandates for EBP implementation.

All stakeholder groups anticipated that concrete recommendations for EBP implementation would result from the study. PMs expected recommendations on clinician training, supervisory tools, and clinician burnout; while therapists reported hoping for strategies to address therapist burden and attrition. PMs indicated that study participation has already, or is anticipated to, result in improved implementation outcomes, predominantly within the context of EBP fidelity. PM respondents commented on the potential for sustained implementation of EBPs through improving fidelity to EBPs.

Both types of organizational respondents (PMs and therapists) frequently mentioned the expectation that study findings would be disseminated to EBP developers and county policy makers. PMs and therapists expressed the hope that study findings would be used to improve strategies for implementation among individuals who hold decision-making power. Consistent with this, system leaders did frequent discuss wanting feedback about various clinician training and outcome monitoring practices.

Improved Effectiveness of Care for Clients

System leaders reported anticipating that improved care effectiveness would result from the study and communicated the desire to ensure that clients get better service.

Potential for Sustained Research-Community Collaboration

PM respondents indicated that they hoped to continue to engage with the RCP at the completion of the study/grant. They also reported encouraging others to participate in future research. Therapists and system leaders commented that a benefit of collaboration was a relationship built for future studies. System leaders shared interest in future collaborations focused on expanding to other client populations and EBPs.

Improved Perceptions of Research

Respondents from all stakeholder groups reported improved perceptions of research as a result of their participation. However, this theme was emphasized most frequently by PMs and system leaders who often compared participation in the current research study to less positive experiences with previous studies.

Revised RCP Model

Figure 1 displays a revised version of the RCP framework presented by Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) and Garland and Brookman-Frazee (2015) that accounts for some of the unique processes arising in the observational study of system-driven implementation of EBPs. This revised version of the model includes highlights unique considerations for observational implementation research, particularly in the initial decision to engage in the RCP (denoted by asterisks).

Fig. 1.

Research community partnership for implementation research Adapted from Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012)

Discussion

Overall, this study adds to our understanding of the process of engaging multiple stakeholder groups in observational studies of EBP implementation as usual and begins to elucidate the multiple (and competing) interests in the engagement in, and the outcomes of, observational research. Furthermore, it provides specific direction to implementation and effectiveness researchers on the process of engaging multiple stakeholder groups in the context of system-driven implementation research.

Previously identified processes and outcomes of RCPs in earlier models generally applied to the current research context. One exception is that all stakeholders focused more on study benefits to therapist- and system-level implementation outcomes rather than client-level clinical outcomes (although the latter was noted by system leaders) compared to previous studies. Moreover, there were a number of novel contributions of this study to elucidating extensions of the RCP model. First, a salient, overarching theme in this study were the considerations that took place before stakeholders engaged in the research. Respondents commented on their motivations (e.g., opportunity to share their experiences, excitement about knowledge to be gained, potential to improve services) as well as concerns about potential risks (e.g., negative interpretation or use of findings, time and skepticism of research based on prior experiences) involved in the study. With regard to operational processes during the execution phase of the research, new areas highlighted in this context included managing client confidentiality and the important role of participating agencies in facilitating therapist engagement. In addition to the new elements extending the RCP model, our findings highlighted that the experience of collaboration between researchers and community stakeholders differed by the role of stakeholders within the service system and the corresponding role within the study.

In the initial engagement phase, stakeholder motivations and concerns were understandably shaped by the most direct perceived impacts on their work. PMs/therapists more frequently discussed being motivated by the potential to improving services by through therapist fidelity and training. In a context in which they were not the decision makers in the system-driven EBP implementation, PMs and therapists were particularly motivated by desire to share their experiences and be heard by system leaders and EBP developers. Given their roles in direct service to clients, therapists and PMs raised concerns related to client confidentiality and the burden and clinical implications of session-level data collection. In contrast, system leaders were more focused on motivations concerning the sustainability of EBPs, a reflection of their priority to ensure a return on the investments made in EBP implementation over many years. System leaders were also motivated to learn about the experiences of therapists in this major county-wide effort. Finally, system leaders were frank about their initial concerns related to the potential for research results to be disseminated without adequate consideration of the broader contextual forces that shaped the roll-out and ongoing functioning of the PEI reform.

During the phases of the RCP formation and execution of research activities, additional stakeholder role differences emerged in the perceptions of interpersonal and operational processes. In the RCP model, interpersonal/operational processes reflect ongoing interactions with researchers and previous studies have highlighted the potential challenges in clarifying roles and responsibilities and balancing power through shared decision-making processes in CPBR (Brookman-Frazee et al. 2016b; Drahota et al. 2016). In the current study system leaders were the key partners in influencing the study direction and roll out, and have continued to be engaged in joint interpretation of data and communication of findings. Not surprisingly, a greater proportion of comments about interpersonal processes was found among leaders at the system and organizational-levels. Systems leaders reflected on their early concerns about interpersonal processes in launching the RCP but indicated that ongoing communication and collaboration served to defuse earlier tensions and confusions. In contrast, therapists and PMs tended to focus on strengths in the RCP concerning operational processes, citing the importance of strong support by research personnel in easing the burden of therapist participation. Overall, the ongoing presence and visibility of the research team at provider sites and LACDMH meeting venues appeared to contribute to trust in the RCP.

Within the RCP model, a distinction is made between proximal and distal outcomes of research-community collaborations. In terms of proximal outcomes of the RCP, organizational-level PM and therapists comments focused on partnership synergy generated by consistently positive direct working relationships with researchers at their sites. Although their roles in the study were largely constrained to participant and facilitator roles, rather than partnering on the directions of the RCP, therapists and PM’s felt that that their perspectives, contributions and time were valued by the research team. In contrast, system leaders’ perceptions of partnership synergy were more variable with more negative appraisals about role clarity, responsibility and communication, particularly early in the launch of the study. This aligns with previous research noting that challenges in partnership are to some extent a normative and may be expected when researchers and community leaders may have shared and unshared priorities and missions which require direct attention to processes of shared decision-making and power structures.

However, comments concerning knowledge exchange and direct impacts of the RCP process were more uniformly positive across stakeholder groups, but again the content of the perceptions varied according to system roles. System leaders emphasized the value of learning about and contributing to implementation science as a field through the activities of the RCP. In contrast, organizational-level therapists and PMs focused on knowledge to be gained and shared concerning how to support the integrity of EBP implementation efforts at the clinical level.

In terms of distal outcomes, stakeholders across groups cited the important potential implications of the study findings for identifying improved and new methods of supporting EBP implementation in the local context. Therapists and PMs were particularly eager for the findings to inform decisions by LACDMH system leaders and EBP developers and trainers. The focus of these desired products differed by stakeholder type. Whereas, PMs cited the need to develop tools to support therapist supervision and training, therapists were hoping that findings would translate to strategies to reduce therapist burden and burnout, and system leaders were invested in workforce training strategies to increase capacity for monitoring the delivery of and outcomes associated with EBP implementation. The data also provided evidence of stakeholder considerations of the distal outcome of increased capacity for sustained and future research-community collaboration. Despite some earlier concerns about RCP functioning, system leaders voiced interest in future studies in multiple areas of inquiry. PMs and therapists described an eagerness to participate in future research activities. Relatedly, a new aspect of distal outcomes was added to the RCP model to capture comments from all stakeholder groups that noted improved perceptions of research and researchers.

Thus, the current study extended a previous model of RCP originally developed in the context of investigator-driven community-partnered EBP implementation studies (Brookman-Frazee et al. 2012). Modifications to the model highlighted the competing and complementary interests that shape stakeholder views on engaging in an RCP focused on studying system-driven implementation. Synthesizing across results, themes emerged in three patterns: (1) themes noted by organizational-level PMs and therapists reflected views as RCP study Participants; (2) themes raised by leaders across agency- and system-levels who were RCP Participant-Partners and Partners, respectively; (3) themes raised only by system-leaders who occupied the role of RCP Partners; and (4) themes common to all stakeholder groups. There were no themes that uniquely pertained to therapist participant views on the RCP process or outcomes.

Distinctive patterns of themes, particularly around the initial decision to engage in the RCP emerged differently depending on the role of partner, participant-partners, and participant. Because system leaders spearheaded the PEI transformation and the parameters of the implementation effort, they had the most to lose in a ‘neutral observational study’. They understandably also had greater expectations for balancing power and interests as co-equal partners in the RCP. In contrast, many PM and therapists as saw engagement in the study as an indirect way to communicate their needs and perspectives about the challenges of EBP implementation back to the system leaders; as they saw the RCP as a way they could ‘have a voice’ within a mandated reform. Conversely, system leaders were invested in generating data that could help identify strategies that work to support therapists and programs achieve robust EBP implementation. This set of findings is consistent with the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework (Aarons et al. 2011) which characterizes RCPs as occupying the position of a bridging factor between the outer (system-level) and inner (organizational-level) contexts of EBP implementation (Moullin et al. 2019). Finally, in terms of complementary concerns, all stakeholders shared the key risk of study data being misused or unfairly interpreted. For organizational participant-partners this involved concerns about the study functioning like an audit or fidelity check that could result in negative evaluations of program or provider performance, whereas for the system-leader partners, there were perceived risks about study data being taken out of context of the unique fiscal and historical backdrop that shaped the system-driven reform. Through the operational and interpersonal processes invoked in the RCP, open communication and trust building was achieved between the researchers and partners and partner-participants which ultimately promoted the proximal and distal outcomes of the RCP.

There are several limitations that may affect the generalizability of the results. First, this research was conducted with a subset of therapists and program managers involved in the 4KEEPs study. It is possible that participating stakeholders were more likely those with a positive experience with the RCP. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria resulted in the omission of perspectives of individuals who elected not to participate in study activities. In particular, it is plausible that ineligible community stakeholders would have provided important and different insights into the calculus of decisions to engage in the RCP. It may be worthwhile to further investigate multiple stakeholder perspectives on RCPs that characterize community-driven implementation of EBPs, using quantitative and mixed methods. Such future research would ideally be inclusive of stakeholder groups not examined in the current study, namely consumer and EBP developer perspectives. Although EBP developers did contribute to some study activities in the parent project (i.e., reviewing measures of treatment delivery), we situated the RCP as independent of EBP developers to provide an objective examination of community EBP implementation. Yet, surely EBP developers would have a distinctive set of interests in the study of implementation-as-usual. Indeed, collaboration between researchers, providers, system leaders, community members, and innovation developers is extremely valuable in the study of increasingly system-driven scale-up efforts. This work requires the simultaneous consideration of multiple level perspectives to improving the process and outcomes of EBP implementation at the system-, provider agency-, and front-line therapist levels. This study provides novel results which indicate that use of RCP approaches are promising in elucidating distinctive concerns about engaging in observational research on community driven EBP implementation.

Role of Implementation Research Institute

The Implementation Research Institute (IRI) played a critical role in this study. First, the idea for the 4KEEPS study was conceived during the 2011 IRI institute when the PIs took notice that LA County had recently undergone a system-driven transformation involving a fiscal mandate for multiple EBP implementation. Second, 4KEEPS investigation team was cultivated through participation in the IRI. Specifically, the PIs and all co-investigators and consultants were IRI fellows or core faculty that met during the 2010 and 2011 IRI summer institutes and continued their close collaboration thereafter. The network came together based on a shared interest in system-driven implementation efforts and complementary areas of expertise in a large-scale mixed methods study (e.g., implementation theory, design, measures). Senior IRI faculty provided instrumental support in terms of introductions that permitted the initial formation of the RCP that was subsequently maintained and extended through the activities described. Lastly, the implementation theoretical framework, design and measures were also significantly shaped by the formal training experiences provided at IRI. The knowledge shared in the IRI helped the investigators to situate this naturalistic implementation effort within existing theory and identified gaps in research on sustainment of multiple EBPs.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Adams DR, Kratz HE, Jackson K, Berkowitz S, Zinny A, et al. (2016). Lessons learned while building a trauma-informed public behavioral health system in the City of Philadelphia. Evaluation and Program Planning, 59, 21–32. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Stadnick N, Roesch S, Regan J, Barnett M, Bando L,… Lau A (2016). Measuring sustainment of multiple practices fiscally mandated in children’s mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 1009–1022. 10.1007/s10488-016-0731-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Stahmer AC, Lewis K, Feder JD, & Reed S (2012). Building a research-community collaborative to improve community care for infants and toddlers at-risk for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(6), 715–734. 10.1002/jcop.21501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Stahmer A, Stadnick N, Chlebowski C, Herschell A, & Garland AF (2016b). Characterizing the use of research-community partnerships in studies of evidence-based interventions in children’s community services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(1), 93–104. 10.1007/s10488-014-0622-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss F, & Kegler MC (2002). Toward a comprehensive understanding of community coalitions: Moving from practice to theory In DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, & Kegler MC (Eds.), Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research (pp. 157–193). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JL, Aratani Y, Knitzer J, Douglas-Hall A, Masi R, Banghart PL, & Dababnah S (2008). Unclaimed children revisited: The status of children’s mental health policy in the United States. 10.7916/d8br91xn [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drahota A, Meza RD, Brikho B, Naaf M, Estabillo JA, Gomez ED, et al. (2016). Community-academic partnerships: A systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. The Milbank Quarterly, 94(1), 163–214. 10.1111/1468-0009.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, & Brookman-Frazee L (2015). Therapists and researchers: Advancing collaboration. Psychotherapy Research, 25(1), 95–107. 10.1080/10503307.2013.838655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleacher AA, Nadeem E, Moy AJ, Whited AL, Albano AM, Radigan M, et al. (2011). Statewide CBT training for clinicians and supervisors treating youth: The New York State Evidence Based Treatment Dissemination Center. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 19(3), 182–192. 10.1177/1063426610367793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AB, Chinman M, Cohen AN, Oberman RS, & Young AS (2015). Implementation of consumer providers into mental health intensive case management teams. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 42(1), 100–108. 10.1007/s11414-013-9365-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A (2010). When technology fails: Getting back to nature. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(1), 77–81. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.). (2005). Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, & Wells K (2007). Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(4), 407–410. 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, & Cross G (2014). From the laboratory to the therapy room: National dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. American Psychologist, 69(1), 19–33. 10.1037/a0033888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, & Brookman-Frazee L (2016). The 4KEEPS study: Identifying predictors of sustainment of multiple practices fiscally mandated in children’s mental health services. Implementation Science, 11(1), 1–31. 10.1186/s13012-016-0388-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, & Aarons GA (2019). Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science, 14(1), 1 10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software (Version 10) [Computer software]. (2012). Retrieved from http://www.qsrinternational.com/.

- Palinkas LA (2014). Qualitative and mixed methods in mental health services and implementation research. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(6), 851–861. 10.1080/15374416.2014.910791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, & Mittman B (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(1), 24–34. 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer MA, & Dearing JW (2011). An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 101(11), 2059–2067. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer AC, Brookman-Frazee L, Lee E, Searcy K, & Reed S (2011). Parent and multidisciplinary provider perspectives on earliest intervention for children at risk for autism spectrum disorders. Infants and Young Children, 24(4), 344–363. 10.1097/IYC.0b013e31822cf700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss ES, Anderson RM, & Lasker RD (2002). Making the most of collaboration: Exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Education & Behavior, 29(6), 683–698. 10.1177/109019802237938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Miranda J, Bruce ML, Alegria M, & Wallerstein N (2004). Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(6), 955–963. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willms DG, Best AJ, Taylor DW, Gilbert JR, Wilson DMC, Lindsay EA, et al. (1990). A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 4(4), 391–409. 10.1525/maq.1990.4.4.02a00020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]