Abstract

The decision to urinate is a social behavior that is calculated multiple times a day. Many animals perform urine scent-marking which broadcasts their pheromones to regulate the behavior of others and humans are trained at an early age to urinate only at a socially acceptable time and place. The inability to control when and where to void, incontinence, causes extreme social discomfort yet targeted therapeutics are lacking because little is known about the underlying circuits and mechanisms. The use of animal models, neurocircuit analysis, and functional manipulation is beginning to reveal basic logic of the circuit that modulates the decision of when and where to void.

Introduction

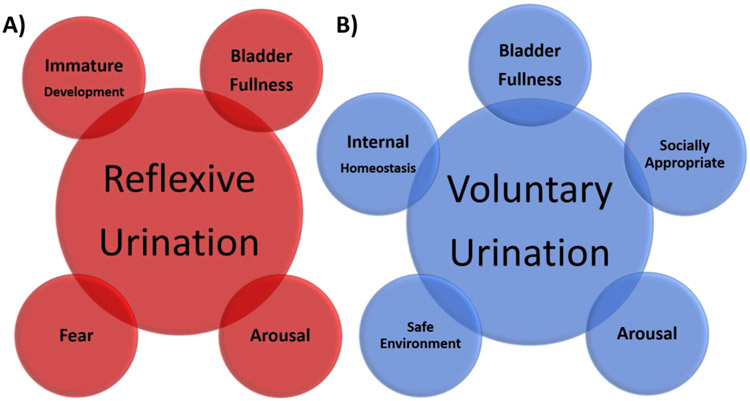

Urination is one of the most commonly and routinely performed social behaviors. During infancy, urination is reflexive, automatic, and subconsciously executed to meet physiological demands (Figure 1a). Urination becomes an active choice following developmental learning with many terrestrial vertebrates, including humans and mice [1], tightly regulating where to excrete to minimize the fouling of the environment and health risks. In humans, choosing when and where to conduct the behavior (herein referred to as ‘voluntary urination’) depends on the presence of others. Will it be physically safe and socially appropriate (Figure 1b)? Several times a day the human brain consciously measures the fullness of the bladder and calculates the urgency to urinate. If a fullness is perceived, one must plan to stop other ongoing behavior, identify an appropriate location, prepare to remain sedentary, and then actively initiate elimination. The social component of human urination is further appreciated when the ability to voluntarily urinate is eliminated by disease, dysfunction, or injury. Strikingly, the majority of those living with spinal cord injury indicate that among the motor capabilities lost (including walking, sexual function, eating, and dressing) the greatest impact on their quality of life is loss of bladder control [2].

Figure 1. Brain decisions that modulate voluntary urination.

A) Reflexive urination is triggered in the spinal cord, independently of the brain. Urination reflex can be triggered by intense fear states and when the infant/juvenile bladder reaches capacity. B) Many factors influence the perception of bladder fullness and the action to urinate. These include the state of bladder stretch, internal homeostasis (stress, thirst), arousal levels, safety, and external social signals. Brain nodes that account for these computations remain largely unknown.

Many interventions have been proposed to restore voluntary urinary control [3-5]. Unfortunately, none are currently routinely effective. Historically, it has been difficult to study how the brain promotes voluntary urination in model animals because it has been impossible to discern if a non-verbal species is indeed urinating voluntarily or reflexively (Figure1). This problem has recently been solved by leveraging urine scent marking, a common social behavior performed by many terrestrial vertebrate species whose urine contains pheromones. Pheromones are specialized odor cues emitted to convey personal information and influence behavior of others. Urine scent-marking is an innate form of voluntary urination that is promoted by the smell of conspecifics as a means to time the release of pheromones when it is socially advantageous [6-8]. However, the release of odor cues leaves one vulnerable to predation and interspecies competition, therefore, requires deliberate assessment of the environment and social state. Exposing mice to conspecific scents rapidly triggers voluntary scent marking and provides a robust experimental platform to gain basic understanding of the identity and function of neurons in the brain that facilitate voluntary voiding. Such knowledge is expected to enable a targeted approach for therapeutic intervention of incontinence.

Sensing: is there a need to urinate?

Being able to accurately sense bladder fullness and anticipate urgency critically underlies human voluntary urination. Repeatedly overfilled bladders lose compliance and become flaccid resulting in incomplete voids. Chronically over- and under-filled bladders create environments for infection. Clinically, fullness is subjectively evaluated by progressive awareness to urinate; first desire, strong desire, and urgency to void. The last category is often associated with perceived pain [9]. Electrophysiological studies in animal models have identified at least two different types of bladder sensory afferents; low threshold myelinated A-δ fibers (associated with stretch) and high threshold unmyelinated C fibers (associated with pain) [10,11].

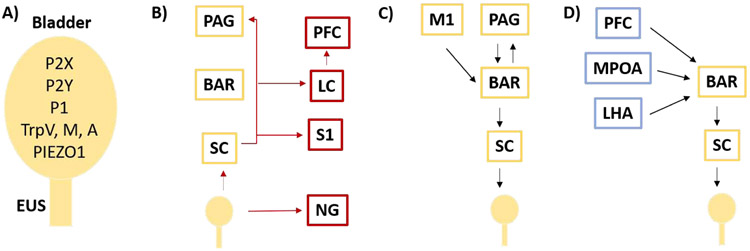

Molecular studies to determine the identity of the sensory channels have largely relied on animal models where perceptual reporting is impossible. In humans, lack of sensation increases bladder size and occurrences of incomplete voids, while decreasing bladder compliance and voiding frequency. These quantifiable measures are often used as proxies for sensation in animal models. The bladder and its innervating neurons express a variety of receptors that have all been implicated in sensation including P2X(1-7), P2Y(1,2,4,&6), P1, TRPV(1,2&4), TRPM7&8, TRPA1, and PIEZO1 [12-20] (Figure 2a). Relying on animal model phenotypes as reporters, no single receptor has been shown to be sufficient for the range of bladder sensations.

Figure 2. Neural circuits driving urination.

A) Bladder expresses many channels that have been implicated in signaling stretch and pain. B) Anatomical ascending circuit (red) that may underly bladder fill state sensation. C) Minimal descending circuit between the PAG (yellow) and the bladder/EUS directs urination motor output (black arrows). D) Nodes in blue may modulate urination. BAR – Barringtons Nucleus, LC – Locus Ceruleus, LHA – Lateral Hypothalamic Area, LUT – Lower Urinary Tract, M1 –Motor Cortex, MPOA – Medial Preoptic Area, NG – Nodose Ganglia, PAG – Periaqueductal Gray, S1 –Somatosensory Cortex, PFC- Pre Frontal Cortex, SC – Spinal Cord, EUS – External Urethral Sphincter

Both TRPV4 and PIEZO1 have each been proposed to serve as bladder stretch sensing channels in urothelial cells and bladder neurons [14,16,19,20]. The potential role of PIEZO1 is intriguing because it is the only receptor known to be expressed in the bladder that has been shown to be a bonafide mechanosensor [21,22]. Upon stretch, mouse bladder urothelial cells flux Ca2+ and release ATP in both a TRPV4 and PIEZO1 dependent manner, but PIEZO1 displays a higher range of sensitivity and response; and specific knock-down of PIEZO1 is sufficient to attenuate the stretch-evoked Ca+ influx and ATP release [16]. ATP activates P2X and P2Y receptors on either afferent nerve terminals or the interstitial cells of Cajal, likely serving as the high threshold receptors that generate an additional signal of urgency and pain [12,13,18]. Further study is necessary to identify the repertoire of the sensors that measure bladder fill state.

Transmitting bladder state to the brain

The identity of the key sensory channels will enable elucidation of their precise neural projections and the circuit that calculates urgency to urinate. Currently, non-specific information flow from the lower urinary tract has been studied. Neurons ascending from the bladder synapse in the spinal cord to transfer sensory information to the brain [23] (Figure 2b). Spinal cord injury patients that lack further ascending transmission reflexively urinate when the bladder reaches capacity, suggesting some ability of the spinal cord to independently detect need and trigger action. The scope of local computations that the spinal cord performs during voluntary urination remains largely unknown. From the spinal cord, bladder fullness state information is transferred to the brain along at least three potential routes. The majority of ascending neurons project to the periaqueductal gray (PAG) [24,25] (Figure 2b). PET imaging in humans has found that PAG activity correlates with bladder volume [26]. Histology in the rat has identified a subset of excitatory ventrolateral (vl)PAG neurons that are active in response to bladder stimulation [27,28]. These findings have been supported by single unit recordings in the PAG of anesthetized cats revealing two populations of neurons with tonic activity throughout the cycle, one predominating during urine storage and another with greater activity during discharge [29]. However, the human experiments that associate PAG activity with bladder stretch do not correlate with the subject’s self-reporting their perception of bladder fullness [26]. Together, the activity profiles in the PAG are consistent with the motor behavior required to ensure storage or elimination, but not with perception of bladder fullness or need. One may expect the critical neurons that report the amount of bladder stretch and degree of urgency to be silent following elimination, active only in the later phases of the storage cycle, and scale in either individual neural activity or number of excited cells. With this assumption, subset(s) of neurons in the PAG that report bladder sensation still await identification.

Electrical stimulation of the bladder muscle also evokes neural activity in the locus coeruleus (LC) [28] (Figure 2b), and LC neurons have been shown to be activated during bladder distention [30]. LC activity is relevant because it houses neurons that release norepinephrine to promote alertness and arousal [31] which is often the perceptual brain state that occurs during the human experience of bladder fullness and urgency to void. LC single neuron activity in anesthetized rats show a dramatic increase in firing rate as bladder pressure rises prior to voiding and cease activity as the bladder empties [32], consistent with sensation or arousal. Alternatively, anatomic tracing from the bladder in rats has identified a third path of information flow bypassing the spinal cord and utilizing the nodose ganglia [33] (Figure2b). This could provide a mechanism to account for the small subset of spinal cord injury patients that maintain a perception of bladder state [34]. The perception of need is not always fixed to absolute bladder pressure; it is modulated by arousal, stress, attention, and environment. One may feel a moderate need to urinate when nearing a restroom that rapidly advances to critical urgency when encountered with a long line and few toilets. Identification of the brain regions that compute bladder fullness will enable study of mechanisms that generate and modulate perception.

Voluntary urination requires control of action

Incontinence from spinal cord injury indicates that voluntary control of urination originates in the brain. The pontine micturition center (PMC) is a functional name for Barrington’s nucleus (Bar) in the pons which lesion studies revealed to be critical for urination control almost a century ago [35]. The PAG not only receives dense innervation from bladder afferents, it also sends projections to Bar [36-40] (Figure 2c). Single unit recordings in anesthetized cats find four sub-types of PAG neurons that correlate with motor activity; including neurons that are (a) active only during bladder contractions, (b) inactive only during bladder contractions, with tonic activity during bladder filling, (c) partially inhibited during bladder contractions, and (d) tonically active at all times but increase firing during bladder contractions [29]. Analyses of neural activity following bladder stimulation suggest that the medial regions of the PAG contain anti-micturition neurons, which include both local GABAergic interneurons as well as inhibitory projections to the Bar, while the vlPAG contains pro-micturition neurons [41]. In support of this, a recent study by Verstegen and Zeidel has identified excitatory glutamatergic neurons with a monosynaptic connection from vlPAG to the core of Bar (PAGvGlut) [36]. Significantly, the PAG has been implicated in the rapid release of other evolutionarily conserved motor behaviors such as aggression, predatory behaviors and predator evasion, ultrasonic vocalizations, and locomotion [42-48]. Optogenetic stimulation of the Bar terminals of PAGvGlut projections is sufficient to activate Bar neurons, and stimulate immediate urination in awake behaving animals [36]. An alternate route of initiation may occur via the motor cortex (M1). Yao and Chen have described anatomic connections between M1 neurons and Bar [49] (Figure 2c). Calcium imaging of these neurons during awake behavior shows that M1 neuronal activity precedes urination and ceases before voiding ends, and optogenetic stimulation of the M1 is indeed sufficient to initiate urination [49]. These characteristics are consistent with function as an initiation signal.

Though bladder stretch is thought to be the source of ascending sensory information of bladder fullness, bladder smooth muscle is under autonomic control and cannot be the primary target of voluntary voiding. Continence is achieved by tonic contraction of the external urethral sphincter (EUS) which allows the urethra to remain predominantly closed over a lifetime. Damage to this muscle results in urine leakage. Almost forty percent of pregnant women experience urinary incontinence from weakness or damage to the EUS and other pelvic floor muscles [50]. The EUS is a striated muscle, under voluntary control, that must be intentionally relaxed to urinate. Recent studies have indicated that there are at least two distinct, genetically defined cell populations within Bar. The majority of these cells are identified by their expression of corticotropin releasing hormone (BarCrh) [40,51]. while the smaller subset (less than 25%) express estrogen receptor alpha (BarEsr1) [51]. Both populations are excitatory and glutamatergic, yet there are differences in their anatomic projection patterns to the spinal cord as well as behavioral outputs elicited by stimulation of these neurons. Anterograde tracing experiments from the mouse Bar suggest that both BarCrh and BarEsr1 neurons project to lumbosacral mediolateral column preganglionic autonomic neurons in the spinal cord that direct bladder contractions, but only the BarEsr1 neurons project to lumbosacral dorsal gray commissure interneurons in the spinal cord that inhibit (relax) the EUS [40,51]. Consistent with this anatomy, optogenetic activation of BarCrh cells causes a sharp increase in bladder pressure [36,40,51,52] that does not result in voiding, because the EUS remains contracted [51]; while BarEsr1 opto-activation increases bladder pressure and promotes efficient EUS relaxation enabling rapid, productive urination [51]. Moreover, voluntary scent marking ceases following BarEsr1 chemogenetic inhibition, but is not altered when BarCrh activity is impaired [51]. The identity of BarEsr1 neurons now provides a target to further study mechanisms that promote voluntary urination.

BarCrh neurons may play a role in active sensation. The increase in bladder pressure evoked by stimulating BarCrh without EUS inhibition creates a non-voiding bladder contraction [36,51,52]. However, BarCrh photostimulation was recently shown to generate productive voids when the excitation was timed with a full bladder [52]. Non-voiding contractions of the bladder have been proposed as a mechanism of motor-driven sensation [53]. The ability of BarCrh neurons to evoke bladder contraction without EUS relaxation may provide a mechanism to “squeeze the bladder” and refine sensation of bladder fullness without leakage [52], engaging voluntary or reflexive voiding circuits when the increase in bladder pressure reaches a sensation of urgency.

The choice to void integrates internal and external state

Other factors, beyond bladder fullness, promote urination. The sensory environment can promote voiding action when the bladder is not full. This routinely occurs during animal scent marking where the social environment triggers behavior [7]. House pets and humans are trained to void only in appropriate locations which must be learned and recognized based on sensory cues. This latrine behavior naturally emerges in mice to prevent urination in sleeping areas [1]. Internal sensations, interoception, also modulate the decision to urinate. Deviations from baseline stress, activity levels, and thirst suppress or potentiate the sensation of need [54,55]. Mechanisms that enable sensation, learning, and memory to modulate urination are largely unknown.

Bar itself has been a proposed target of modulation. Social stress elicits a strong upregulation of Crh expression in the Bar, and these animals display urine retention and increased bladder size [56], and virus-mediated overexpression of CRH in Bar decreases voiding pressure [57]. However more recently, a targeted knockdown of Crh from Bar neurons did not affect voiding behavior in awake animals or urodynamic parameters like intervoid intervals, bladder pressure, or non-voiding contractions in anesthetized animals [36]. Severe stress, such as mortal fear, can trigger immediate complete voids while minor stress may lead to retention. Whether these modulations occur through Bar expressed CRH or act elsewhere in the brain awaits further study.

While little is known about modulating circuits that direct BarEsr1 activity, Hou and Sabatini performed retrograde viral tracing specifically from BarCrh neurons and found them to be widely connected, receiving information from 27 different brain regions [36,40]. How these nodes modulate the action of the core voiding circuit remains largely unknown. Human imaging data has revealed a relationship between the activity in the cingulate cortex, frontal lobes, and the sensation of bladder filling [26]. In mice, the frontal lobe (including Prefrontal Cortex, PFC) is also implicated in bladder control by lesion studies [58,59] and the PFC is known to send direct glutamatergic projections to BarCrh [60] (Figure 2d). Given the overarching role that the PFC plays in the control of motor and social behavior, it may integrate social, environment, and physiology related information. In support of this idea Manohar and Valentino found an increase in the theta-coherence between the LC and the mPFC prior to voiding in freely moving unanesthetized rats [32]. Voiding was preceded by an elevation in LC activity levels and a desynchronization of mPFC activity. Perhaps the LC increases activity in response to bladder stretch which releases norepinephrine in the mPFC to prioritize behavior that will result in a socially appropriate action.

Many hypothalamic nuclei project to Bar and are known to influence social behavior [36,40,61,62]. Of these, the MPOA (Figure 2d) has been further studied because it is known to play an important role in thirst and sexual behavior in rodents [63,64]. The MPOA neurons that project to Bar are inhibitory (vGat) and chemogenetically inhibiting their activity results in larger voids, which was interpreted to be consistent with the phenotype of subordinate urine-marking behavior [40]. However, the functional meaning of these modulatory nodes may not be simple to interpret as larger marks are also an indication of a loss of voluntary control or bladder fill perception.

The Lateral Hypothalamic Area (LHA) also modulates Bar, through both excitatory and inhibitory monosynaptic connections (Figure2d) [36,60]. Non-selective chemogenetic inhibition of both excitatory and inhibitory cells in the LHA promote urine marking, while chemogenetic activation prevents scent marking [60]. When optogenetics was used to selectively activate the excitatory LHA terminals in the Bar in freely moving mice, urination was stimulated, although inconsistently, more often with a full bladder, and with an approximately half-minute temporal delay. Interestingly, during the delay, individuals were observed to move to the corner of the cage and then urinate [36]. Perhaps, the inhibitory LHA neurons act as a brake to urination, unless bladder fullness is sensed, and then the excitatory neurons may act as a permissive signal that enables voiding, but require engagement of another signal to trigger the void when appropriate. Such a behavior is consistent with a role in latrine behavior during voluntary urination. While the role of the LHA in the regulation of urination remains to be deconvoluted, such a circuit arrangement of modulatory nodes interacting with motor nodes may enable multiple factors to independently influence and modulate the decision of when and where to urinate.

Conclusions

How the brain calculates the decision to urinate is largely unknown. Bladder fullness and internal state have long been understood to influence voiding. Less focus has been placed on the role of the sensory and social environment to have key influence on the probability of both humans and animals to urinate. The ability to trigger voluntary urination using social scent marking in mice, as well as leveraging optogenetics, chemogenetics, and viral tracing methods to precisely identify key neural ensembles has aided recent study of potential circuits and novel mechanisms that underlie voluntary urination. Ultimate understanding of this common daily behavior will illuminate general principles of neural information flow and computation that can be studied during continence and incontinence.

Highlights.

Social cues influence voluntary urination in humans and animal models.

Bladder fullness, sensory cues, and internal state drive voluntary urination.

Voluntary urination utilizes Bar brainstem neurons to relax the urethral sphincter.

Brain regions that regulate Bar may serve to modulate when and where to void.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Kara Marshall, Jason Keller, and the Stowers Lab for discussions and critical comments on the manuscript. LS and SM were supported by NIH R01NS108439.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Makowska IJ, Franks B, El-Hinn C, Jorgensen T, Weary DM: Standard laboratory housing for mice restricts their ability to segregate space into clean and dirty areas. Sci Rep 2019, 9:6179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Hsieh JT, Wolfe DL, Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Scire Research T: The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma 2012, 29:1548–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niu T, Bennett CJ, Keller TL, Leiter JC, Lu DC: A Proof-of-Concept Study of Transcutaneous Magnetic Spinal Cord Stimulation for Neurogenic Bladder. Sci Rep 2018, 8:12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell CR: Conditional Electrical Stimulation in Animal and Human Models for Neurogenic Bladder: Working Toward a Neuroprosthesis. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep 2016, 11:379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mickle AD, Won SM, Noh KN, Yoon J, Meacham KW, Xue Y, McIlvried LA, Copits BA, Samineni VK, Crawford KE, et al. : A wireless closed-loop system for optogenetic peripheral neuromodulation. Nature 2019, 565:361–365.** This technical tour-de-force implants a wireless micro light-emitting diode to deliver optogentic control directly to a rat’s bladder that is monitored in real time by a stretchable strain gauge. This approach shows promise for chronic stability and can be genetically directed to specific cell types.

- 6.Liberles SD: Mammalian pheromones. Annu Rev Physiol 2014, 76:151–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurst JL, Beynon RJ: Scent wars: the chemobiology of competitive signalling in mice. Bioessays 2004, 26:1288–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur AW, Ackels T, Kuo TH, Cichy A, Dey S, Hays C, Kateri M, Logan DW, Marton TF, Spehr M, et al. : Murine pheromone proteins constitute a context-dependent combinatorial code governing multiple social behaviors. Cell 2014, 157:676–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyndaele JJ, De Wachter S: Cystometrical sensory data from a normal population: comparison of two groups of young healthy volunteers examined with 5 years interval. Eur Urol 2002, 42:34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison J: The activation of bladder wall afferent nerves. Exp Physiol 1999, 84:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshimura N, White G, Weight FF, de Groat WC: Patch-clamp recordings from subpopulations of autonomic and afferent neurons identified by axonal tracing techniques. J Auton Nerv Syst 1994, 49:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cockayne DA, Dunn PM, Zhong Y, Rong W, Hamilton SG, Knight GE, Ruan HZ, Ma B, Yip P, Nunn P, et al. : P2X2 knockout mice and p2X2/p2X3 double knockout mice reveal a role for the P2X2 receptor subunit in mediating multiple sensory effects of ATP. J Physiol 2005, 567:621–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cockayne DA, Hamilton SG, Zhu QM, Dunn PM, Zhong Y, Novakovic S, Malmberg AB, Cain G, Berson A, Kassotakis L, et al. : Urinary bladder hyporeflexia and reduced pain-related behaviour in P2X3-deficient mice. Nature 2000, 407:1011–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen DA, Hoenderop JG, Heesakkers JP, Schalken JA: TRPV4 mediates afferent pathways in the urinary bladder. A spinal c-fos study showing TRPV1 related adaptations in the TRPV4 knockout mouse. Pflugers Arch 2016, 468:1741–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merrill L, Gonzalez EJ, Girard BM, Vizzard MA: Receptors, channels, and signalling in the urothelial sensory system in the bladder. Nat Rev Urol 2016, 13:193–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyamoto T, Mochizuki T, Nakagomi H, Kira S, Watanabe M, Takayama Y, Suzuki Y, Koizumi S, Takeda M, Tominaga: Functional role for Piezo1 in stretch-evoked Ca(2)(+) influx and ATP release in urothelial cell cultures. J Biol Chem 2014, 289:16565–16575.* This study performs a systematic analysis of PIEZ01 channels in native urothelial cells and finds them necessary to transduce the signal that leads to ATP release. These characteristics are expected of the stretch receptor that senses bladder fullness.

- 17.Negoro H, Urban-Maldonado M, Liou LS, Spray DC, Thi MM, Suadicani SO: Pannexin 1 channels play essential roles in urothelial mechanotransduction and intercellular signaling. PLoS One 2014, 9:e106269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rong W, Spyer KM, Burnstock G: Activation and sensitisation of low and high threshold afferent fibres mediated by P2X receptors in the mouse urinary bladder. J Physiol 2002, 541:591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mochizuki T, Sokabe T, Araki I, Fujishita K, Shibasaki K, Uchida K, Naruse K, Koizumi S, Takeda M, Tominaga M: The TRPV4 cation channel mediates stretch-evoked Ca2+ influx and ATP release in primary urothelial cell cultures. J Biol Chem 2009, 284:21257–21264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshiyama M, Mochizuki T, Nakagomi H, Miyamoto T, Kira S, Mizumachi R, Sokabe T, Takayama Y, Tominaga M, Takeda M: Functional roles of TRPV1 and TRPV4 in control of lower urinary tract activity: dual analysis of behavior and reflex during the micturition cycle. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2015, 308:F1128–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, Earley TJ, Ranade S, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A: Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science 2010, 330:55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syeda R, Florendo MN, Cox CD, Kefauver JM, Santos JS, Martinac B, Patapoutian A: Piezo1 Channels Are Inherently Mechanosensitive. Cell Rep 2016,17:1739–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC: The neural control of micturition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008, 9:453–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blok BF, De Weerd H, Holstege G: Ultrastructural evidence for a paucity of projections from the lumbosacral cord to the pontine micturition center or M-region in the cat: a new concept for the organization of the micturition reflex with the periaqueductal gray as central relay. J Comp Neurol 1995, 359:300–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanderhorst VG, Mouton LJ, Blok BF, Holstege G: Distinct cell groups in the lumbosacral cord of the cat project to different areas in the periaqueductal gray. J Comp Neurol 1996, 376:361–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Athwal BS, Berkley KJ, Hussain I, Brennan A, Craggs M, Sakakibara R, Frackowiak RS, Fowler CJ: Brain responses to changes in bladder volume and urge to void in healthy men. Brain 2001,124:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zare A, Jahanshahi A, Meriaux C, Steinbusch HW, van Koeveringe GA: Glutamatergic cells in the periaqueductal gray matter mediate sensory inputs after bladder stimulation in freely moving rats. Int J Urol 2018, 25:621–626.* This study identified a population of excitatory glutamatergic cells in the Periaqueductal Gray (PAG) that are activated in response to electrical stimulation of the bladder of freely moving rats. Their findings provide a starting point to understand the ascending inputs from the bladder to the PAG at a more cellularly defined level.

- 28.Meriaux C, Hohnen R, Schipper S, Zare A, Jahanshahi A, Birder LA, Temel Y, van Koeveringe GA: Neuronal Activation in the Periaqueductal Gray Matter Upon Electrical Stimulation of the Bladder. Front Cell Neurosci 2018, 12:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z, Sakakibara R, Nakazawa K, Uchiyama T, Yamamoto T, Ito T, Hattori T: Micturition-related neuronal firing in the periaqueductal gray area in cats. Neuroscience 2004,126:1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page ME, Akaoka H, Aston-Jones G, Valentino RJ: Bladder distention activates noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by an excitatory amino acid mechanism. Neuroscience 1992, 51:555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovett-Barron M, Andalman AS, Allen WE, Vesuna S, Kauvar I, Burns VM, Deisseroth K: Ancestral Circuits for the Coordinated Modulation of Brain State. Cell 2017,171:1411–1423 e1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manohar A, Curtis AL, Zderic SA, Valentino RJ: Brainstem network dynamics underlying the encoding of bladder information. Elife 2017, 6.* This study carries out single unit recording at the Barrington’s Nucleus concurrently with cystometry in freely moving animals for the first time. The authors demonstrate a synchrony between the Locus Ceruleus and the Prefrontal Cortex that arises about 20 seconds prior to micturition, opening up the possibility that this is important for the mPFC to coordinate behavior such that the organism voids appropriately.

- 33.Herrity AN, Rau KK, Petruska JC, Stirling DP, Hubscher CH: Identification of bladder and colon afferents in the nodose ganglia of male rats. J Comp Neurol 2014, 522:3667–3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krhut J, Tintera J, Bilkova K, Holy P, Zachoval R, Zvara P, Blok B: Brain activity on fMRI associated with urinary bladder filling in patients with a complete spinal cord injury. Neurourol Urodyn 2017, 36:155–159.** fMRI brain imaging was performed on spinal cord injury patients during bladder filling. They find evidence for an extraspinal sensory pathway to convey bladder fill state that utilizes the vagas nerve.

- 35.Barrington FJF: The effect of lesions of the hind- and mid-brain on micturition in the cat. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology and Cognate Medical Sciences 1925, 15:81–102. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verstegen AMJ, Klymko N, Zhu L, Mathai JC, Kobayashi R, Venner A, Ross RA, VanderHorst VG, Arrigoni E, Geerling JC, et al. : Non-Crh Glutamatergic Neurons in Barrington’s Nucleus Control Micturition via Glutamatergic Afferents from the Midbrain and Hypothalamus. Curr Biol 2019, 29:1–15.** This elegant study shows how two separate inputs into the Barringtons Nucleus (Bar) influence voiding behaviors at different time scales. Opto-stimulation of glutamatergic vIPAG afferents to the Bar causes immediate release of urination while opto-stimulation of glutamatergic LH afferents to the Bar causes a more delayed, purposeful voiding behavior by the freely moving animal. This data is the first to interrogate the role of vIPAG - Bar projections using modern circuit elucidation tools like optogenetics and fiber photometry.

- 37.Kuipers R, Mouton LJ, Holstege G: Afferent projections to the pontine micturition center in the cat. J Comp Neurol 2006, 494:36–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mouton LJ, Holstege G: Segmental and laminar organization of the spinal neurons projecting to the periaqueductal gray (PAG) in the cat suggests the existence of at least five separate clusters of spino-PAG neurons. J Comp Neurol 2000, 428:389–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding YQ, Zheng HX, Gong LW, Lu Y, Zhao H, Qin BZ: Direct projections from the lumbosacral spinal cord to Barrington's nucleus in the rat: a special reference to micturition reflex. J Comp Neurol 1997, 389:149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou XH, Hyun M, Taranda J, Huang KW, Todd E, Feng D, Atwater E, Croney D, Zeidel ML, Osten P, et al. : Central Control Circuit for Context-Dependent Micturition. Cell 2016,167:73–86 e12.** This study was the first to apply new neuroscience tools including fiber photometry, chemogenetics and optogenetics to investigate the role of Crh expressing neurons in the Barringtons Nucleus (Bar) in urination behavior. They demonstrated the role of Bar-Crh neurons to influence bladder pressure. They additionally used a modified Rabies Virus tracing strategy to identify brain regions that are presynaptic to Bar-Crh neurons and found MPOA neurons to regulate micturition patterns.

- 41.Numata A, Iwata T, luchi H, Taniguchi N, Kita M, Wada N, Kato Y, Kakizaki H: Micturition-suppressing region in the periaqueductal gray of the mesencephalon of the cat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008, 294:R1996–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans DA, Stempel AV, Vale R, Ruehle S, Lefler Y, Branco T: A synaptic threshold mechanism for computing escape decisions. Nature 2018, 558:590–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Falkner AL, Wei D, Song A, Watsek LW, Chen I, Feng JE, Lin D: PAG neurons encode a simplified action-selective signal during aggression. bioRxiv 2019, 10.1101/745067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han W, Tellez LA, Rangel MJ Jr., Motta SC, Zhang X, Perez IO, Canteras NS, Shammah-Lagnado SJ, van den Pol AN, de Araujo IE: Integrated Control of Predatory Hunting by the Central Nucleus of the Amygdala. Cell 2017, 168:311–324 e318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Zeng J, Zhang J, Yue C, Zhong W, Liu Z, Feng Q, Luo M: Hypothalamic Circuits for Predation and Evasion. Neuron 2018, 97:911–924 e915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park SG, Jeong YC, Kim DG, Lee MH, Shin A, Park G, Ryoo J, Hong J, Bae S, Kim CH, et al. : Medial preoptic circuit induces hunting-like actions to target objects and prey. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21:364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tschida K, Michael V, Takatoh J, Han BX, Zhao S, Sakurai K, Mooney R, Wang F: A Specialized Neural Circuit Gates Social Vocalizations in the Mouse. Neuron 2019,103:459–472 e454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao ZD, Chen Z, Xiang X, Hu M, Xie H, Jia X, Cai F, Cui Y, Chen Z, Qian L, et al. : Zona incerta GABAergic neurons integrate prey-related sensory signals and induce an appetitive drive to promote hunting. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22:921–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao J, Zhang Q, Liao X, Li Q, Liang S, Li X, Zhang Y, Li X, Wang H, Qin H, et al. : A corticopontine circuit for initiation of urination. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21:1541–1550.* Interrogates the contribution of a projection from the primary motor cortex (M1) to Barringtons Nucleus on urination in freely moving mice. Using a combination of transsynaptic viral tracing, fiber photometry, optogenetics and cystometry in freely moving animals, the authors demonstrate a role for these M1 layer 5 neurons in the initiation of voiding by inducing an increase in bladder pressure. First paper to use genetic and viral manipulation tools to probe cortical contribution to voiding.

- 50.Daly D, Clarke M, Begley C: Urinary incontinence in nulliparous women before and during pregnancy: prevalence, incidence, type, and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J 2018, 29:353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keller JA, Chen J, Simpson S, Wang EH, Lilascharoen V, George O, Lim BK, Stowers L: Voluntary urination control by brainstem neurons that relax the urethral sphincter. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21:1229–1238.** Identifies and demonstrates the role of a population of Esr1 expressing neurons in the Barringtons Nucleus (Bar) in urination. This study finds that Bar-Esr1 neurons control both the bladder pressure and the activity of the external urethral sphincter (EUS), thereby gating immediate release of urine. Demonstrates the necessity of Bar-Esr1 cells in a natural social behavior (urine countermarking by male mice to female olfactory cues) model of voluntary voiding.

- 52.Ito H, Sales AC, Fry CH, Kanai AJ, Drake MJ, Pickering AE: Corticotrophin-Releasing Hormone neurons of Barrington’s nucleus: Probabilistic, spinally-gated control of bladder pressure and micturition. BioRxiv 2019, 10.1101/683334.* This paper uses a combination of optogenetics, chemogenetics, infusion cystometry, and electromyography to demonstrate that CRH expressing cells in the Barringtons Nucleus (Bar) can induce voiding or non-voiding contractions of the bladder depending on the fill state of the bladder. The data indicate that Bar-Crh cells are potentially involved in sampling the bladder status, and allowing voiding when the bladder is full.

- 53.Eastham JE, Gillespie JI: The concept of peripheral modulation of bladder sensation. Organogenesis 2013, 9:224–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butler S, Luz S, McFadden K, Fesi J, Long C, Spruce L, Seeholzer S, Canning D, Valentino R, Zderic S: Murine social stress results in long lasting voiding dysfunction. Physiol Behav 2018,183:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanhewicz AE, Kenney WL: Determinants of water and sodium intake and output. Nutr Rev 2015, 73 Suppl 2:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood SK, Baez MA, Bhatnagar S, Valentino RJ: Social stress-induced bladder dysfunction: potential role of corticotropin-releasing factor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009, 296:R1671–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McFadden K, Griffin TA, Levy V, Wolfe JH, Valentino RJ: Overexpression of corticotropin-releasing factor in Barrington's nucleus neurons by adeno-associated viral transduction: effects on bladder function and behavior. Eur J Neurosci 2012, 36:3356–3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andrew J, Nathan PW: Lesions on the Anterior Frontal Lobes and Disturbances of Micturition and Defaecation. Brain 1964, 87:233–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsumoto S, Hanai T, Yoshioka N, Shimizu N, Sugiyama T, Uemura H: Medial prefrontal cortex lesions inhibit reflex micturition in anethetized rats. Neurosci Res 2006, 54:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hyun M, Taranda J, Radeljic G, Miner L, Wang W, Ochandarena N, Huang KW, Osten P, Sabatini B: Social isolation uncovers a brain-wide circuit underlying context-depenent territory-covering micturition behavior. BioRxiv 2019, 10.1101/798132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goto M, Canteras NS, Burns G, Swanson LW: Projections from the subfornical region of the lateral hypothalamic area. J Comp Neurol 2005, 493:412–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valentino RJ, Page ME, Luppi PH, Zhu Y, Van Bockstaele E, Aston-Jones G: Evidence for widespread afferents to Barrington's nucleus, a brainstem region rich in corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Neuroscience 1994, 62:125–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Augustine V, Gokce SK, Lee S, Wang B, Davidson TJ, Reimann F, Gribble F, Deisseroth K, Lois C, Oka Y: Hierarchical neural architecture underlying thirst regulation. Nature 2018, 555:204–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kohl J, Babayan BM, Rubinstein ND, Autry AE, Marin-Rodriguez B, Kapoor V, Miyamishi K, Zweifel LS, Luo L, Uchida N, et al. : Functional circuit architecture underlying parental behaviour. Nature 2018, 556:326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]