Summary

The ability of XIST to dosage compensate a trisomic autosome presents unique experimental opportunities and potentially transformative therapeutic prospects. However, it is currently thought that XIST requires the natural context surrounding pluripotency to initiate chromosome silencing. Here, we demonstrate that XIST RNA induced in differentiated neural cells can trigger chromosome-wide silencing of chromosome 21 in Down syndrome patient-derived cells. Use of this tightly controlled system revealed a deficiency in differentiation of trisomic neural stem cells to neurons, correctible by inducing XIST at different stages of neurogenesis. Single-cell transcriptomics and other analyses strongly implicate elevated Notch signaling due to trisomy 21, thereby promoting neural stem cell cycling which delays terminal differentiation. These findings have significance for illuminating the epigenetic plasticity of cells during development, the understanding of how human trisomy 21 effects Down syndrome neurobiology, and the translational potential of XIST, a unique non-coding RNA.

eTOC Blurb:

XIST normally initiates chromosome silencing in pluripotent cells. Here, Czerminski and Lawrence demonstrate the ability of XIST to initiate silencing in differentiated neural cells and show that silencing one chr21 increases neuron formation by trisomic neural stem cells. This identifies the potential role of Notch signaling in Down syndrome neuropathology.

Introduction

Chromosomal abnormalities are surprisingly common – detected in about 0.6% of newborns (Shaffer and Lupski, 2000) – yet because they involve a dosage imbalance for many genes, this major component of the human genetic disease burden has remained largely outside the hopeful advances in genetics research. For Down syndrome (DS), the most common chromosomal disorder, most research has focused on attempting to identify the specific cell pathologies that impact various bodily systems. However, it has been difficult to establish which cell-types and gene pathways are more directly impacted, hence better experimental strategies are needed to determine how trisomy 21 impacts cell function and development. It is particularly challenging to determine when a developmental deficit arises, and when it may remain correctible. Here, we further develop and apply an approach using epigenetics to advance translational research for chromosomal imbalances.

Previously, our lab demonstrated that a natural epigenetic mechanism could be harnessed to repress genes across one chromosome 21 (chr21) in trisomic DS patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) by insertion of a single gene, XIST (Jiang et al., 2013). XIST is a long non-coding RNA that functions in cis to silence one X chromosome to dosage compensate X-linked genes between females (XX) and males (XY). The expression and accumulation of XIST transcripts across the nuclear chromosome territory is essential to initiate chromosome silencing (Brown et al., 1992; Clemson et al., 1996; Lee and Jaenisch, 1997; Penny et al., 1996). In human and mouse, XIST/Xist RNA initiates random X-inactivation in pluripotent inner cell mass cells (van den Berg et al., 2009; Payer and Lee, 2008; Petropoulos et al., 2016; Sahakyan et al., 2018), when epigenomic programming is especially rapid, widespread, and generally exquisitely sensitive to a narrow window of developmental timing. It is of fundamental interest to determine whether the epigenetic plasticity of cells in this unique developmental window is required for XIST RNA to enact heterochromatin chromatin modifications that spread and stably repress chromosome-wide transcription.

Consistent with expectation that the pluripotent context would be required, prior studies reported that Xist RNA could no longer initiate silencing in mES cells just 48-hours after a switch to neural differentiation conditions (Wutz and Jaenisch, 2000). Even most neoplastic cells cannot induce chromosome silencing, although a subset of human cancer cells can partially repress a region near the XIST locus (Chow et al., 2007; Hall et al., 2002; Minks et al., 2013). A later study reported that SATB1 is a key pluripotency factor required for chromosome silencing and expressed in some cancers (Agrelo et al., 2009), but it was later found that X-inactivation still occurs in mice deleted for both SATB1 and SATB2 (Nechanitzky et al., 2012). Savarese et al. (2006) studied Xist transgenic mice in which chromosome silencing would create cell-lethality and reported that a subset of hematopoietic progenitor cells were exceptional in that they “transiently reestablish permissiveness for X inactivation”, further reinforcing the now long-held view that Xist RNA cannot function in differentiated cells. However, since transgene silencing is common in differentiating cells (Gödecke et al., 2017; Huebsch et al., 2016; Laker et al., 1998; Oyer et al., 2009; Xia et al., 2007), but less so in hematopoietic cells, this complicates conclusions based on cell lethality in mice fed doxycycline (Savarese et al., 2006). In any case, the capacity of normal human differentiated cells to respond to XIST has not been directly determined.

In addition to interest for fundamental epigenetics, whether XIST can repress a chromosomal imbalance in somatic cells is also critical to the translational potential of this remarkable RNA. We address this using an inducible XIST transgene inserted on one chr21 in DS iPSCs undergoing neural differentiation in vitro. Using this system, we recently demonstrated that inducing XIST from pluripotency prevents development of well-known DS hematopoietic cell pathologies in vitro, even though cells still carry the extra chromosome (Chiang et al., 2018). This supports the validity of chromosome silencing to investigate effects of trisomy on other cell-types, although this study did not attempt to induce post-differentiation chromosome silencing.

While DS hematopoietic cell pathologies are known, cell pathologies that underlie other clinical phenotypes, including cognitive disabilities, are much less clear (Haydar and Reeves, 2012; Mégarbané et al., 2009; Rafii et al., 2019). Some studies indicate trisomy 21 impacts post-natal neurodevelopment, such as myelination (Olmos-Serrano et al., 2016) and cerebellar growth (Das et al., 2013), and early-onset Alzheimer’s disease is nearly ubiquitous in DS adults. Variable results have been reported regarding trisomy 21 effects on early in vitro neural differentiation (Bhattacharyya et al., 2009; Briggs et al., 2013; Gonzales et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2012; Weick et al., 2013), with most studies reporting no difference in the ability of DS stem cells to form neurons. However, comparisons between cell lines can be limited since iPSC lines from the same individual can demonstrate transcriptional heterogeneity (Liang and Zhang, 2013; Soldner and Jaenisch, 2012) and differences in neural competence (Koyanagi-Aoi et al., 2013).

In addition to evaluating effectiveness of XIST to produce dosage corrected human neural cells, our priority was to test whether XIST can initiate the chromosome silencing process in differentiated neural cells. Our second major goal was to capitalize on this tightly controlled inducible system to investigate effects of trisomy 21 on in vitro DS neurodevelopment. Combining bulk and single-cell RNAseq with molecular cytology, we provide the most quantitative demonstration to date of remarkably complete chr21 dosage compensation, identify a precise cellular phenotype, and provide evidence for a specific developmental step and cell pathway involved.

Results

The panel of isogenic DS iPSCs studied includes multiple transgenic clones carrying a dox-inducible XIST cDNA on one chr21 (Figure 1A), which were shown by microarrays to broadly repress chromosome 21 gene expression in pluripotent cells (Jiang et al., 2013; and Methods). To assess chromosome 21 silencing in differentiated neural cells, DS patient-derived iPSCs were differentiated using established protocols which mirror cortical neurogenesis (Cao et al., 2017; Chambers et al., 2009), with dox added to induce XIST RNA expression from pluripotency, as well as at later times during differentiation.

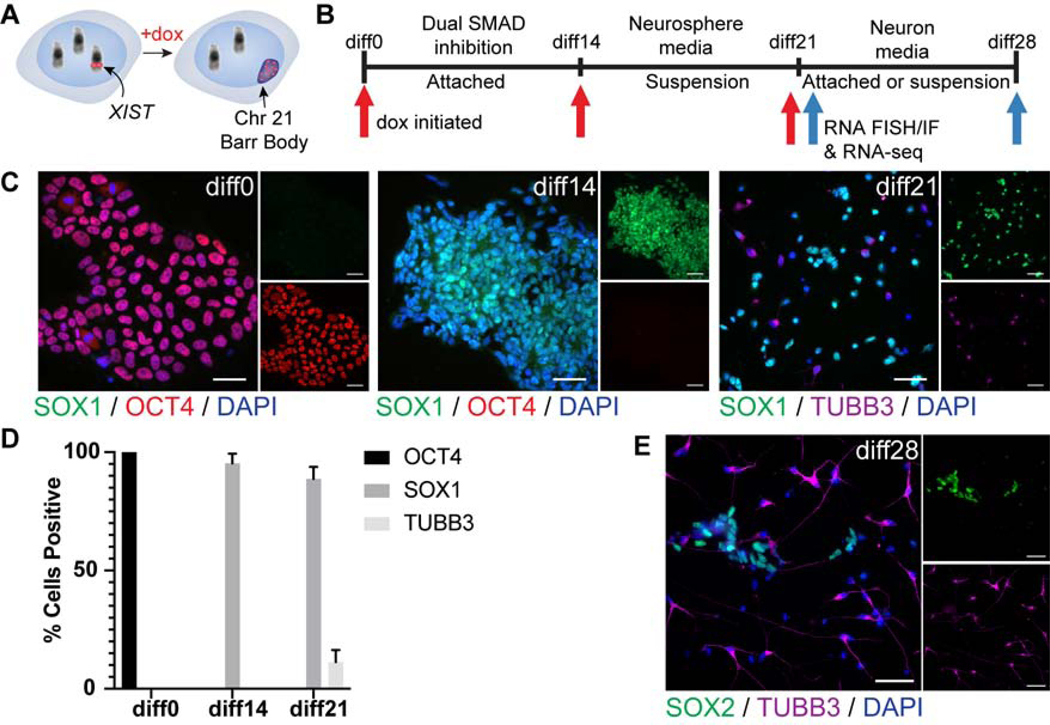

Figure 1:

Experimental design and neural differentiation of DS iPSCs. a) Schematic of XIST-mediated chromosome 21 silencing system. b) Outline of neural differentiation protocol. Dox initiation days marked by red arrows. Analysis timepoints marked by blue arrows. c) IF at dox addition timepoints diff0, diff14, and diff21 for SOX1, OCT4, and TUBB3. d) Quantification of (c) for three transgenic XIST clones. At least 100 cells were scored for each condition. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. e) IF at diff28 for SOX2 and TUBB3. Insets are single channel images. Scale bars are 50μm.

XIST induces heterochromatin hallmarks on chromosome 21 in differentiated neural cells

As an indication of silencing, we first examined two canonical heterochromatin hallmarks. These experiments used a 28-day neural differentiation time-course, with dox introduced at either day 0, 14, or 21. Immunofluorescence (IF) confirmed that by day 14 of differentiation (diff14) no pluripotent (OCT4+) cells are detected, while nearly all cells stained for SOX1, indicating they had differentiated to neural stem cells (NSCs) (Figure 1C&D, Figure S1A). By diff21, ~10% of the NSCs had differentiated to TUBB3+ post-mitotic neurons (Figure 1C&D, Figure S1B). As illustrated in Figure 1E, by diff28, many more neurons have formed, indicating that most terminal differentiation to neurons occurs between diff21 and diff28 (as will be thoroughly quantified below).

When expressed from pluripotency, XIST RNA rapidly (in a few days) triggers multiple repressive chromatin modifications that contribute to the transcriptionally silent state, such as H2AK119ub1 and H3K27me3 modifications by PRC1 and PRC2, respectively (Cao et al., 2002; Fang et al., 2004; de Napoles et al., 2004; Plath et al., 2003). Neural cells in which XIST was expressed from diff0 (d0 dox) showed well-localized XIST RNA paints associated consistently with these two major repressive modifications (Figure 2A–B, and 2D). In parallel samples we investigated whether XIST would properly localize and trigger these hallmarks if dox addition was delayed until diff14 (d14 dox), well beyond pluripotency. While there was some reduction in the proportion of cells transcribing the XIST transgene (Figure 2C), reflecting common transgene silencing effects (Gödecke et al., 2017), over 90% of d14 dox cells had H2AK119ub1 concentrated over a well-localized XIST RNA territory (Figures 2A and 2D). Similarly, close to 90% of XIST+ cells had an associated H3K27me3 focus. Hence, XIST can still recruit PRC1 and PRC2 for heterochromatin modifications in differentiated human neural cells, encouraging us to further examine transcriptional silencing by RNA sequencing.

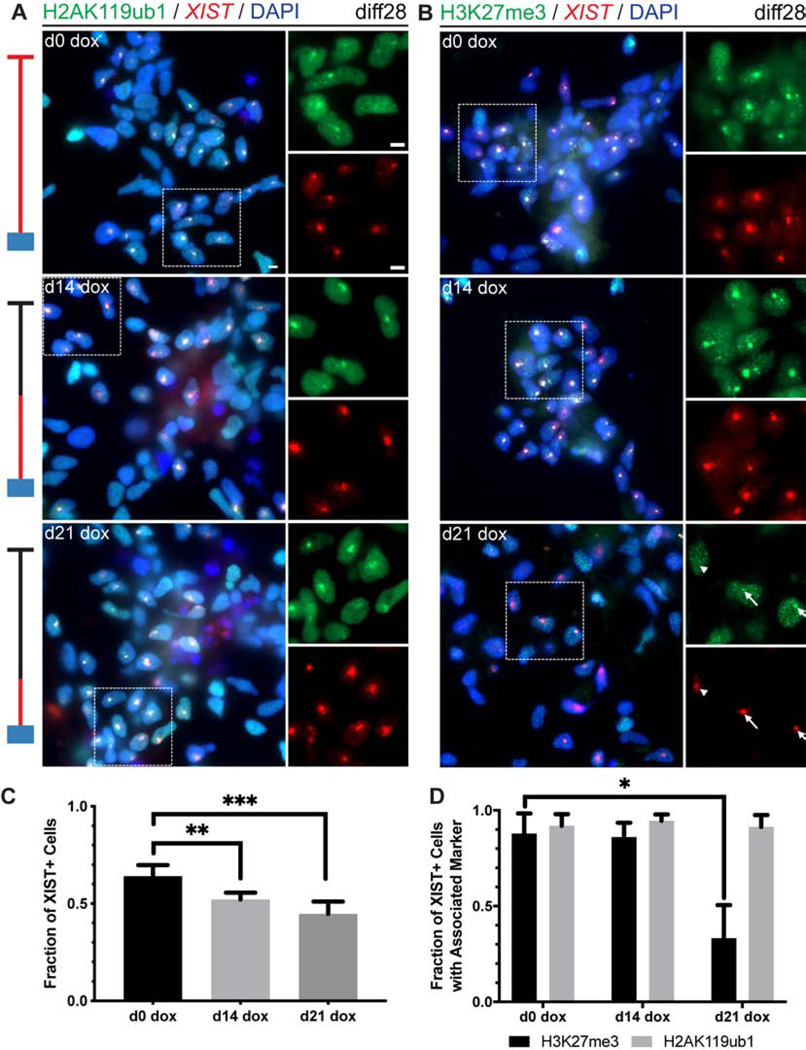

Figure 2:

Recruitment of heterochromatin hallmarks by XIST initiated in NSCs. a-b) Combined RNA FISH for XIST RNA and IF staining for H2AK119ub1 (a) and H3K27me3 (b) in transgenic cells at diff28. Arrows indicate associated signals, and arrowheads indicate XIST paint without associated H3K27me3 signal. Insets are magnified single channel images of outlined area. Schematics of experimental timelines illustrate presence of dox (red line) and analysis timepoints (blue box). c) Quantification of XIST+ cells at diff28 for all dox addition timepoints. d) Quantification of association of heterochromatin markers with XIST+ cells. Note only clearly enriched H3K27me3 signals were scored, which may have been weakly present in a higher fraction of cells in the d21 dox condition. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=3 independent differentiations of one transgenic cell line). 309–926 cells were examined for each sample (median=556). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

We also examined cells induced with dox even later, at diff21 (d21 dox), just seven days before analysis, which showed H2AK119ub1 again consistently enriched with XIST RNA. H3K27me3 was also clearly enriched in many cells, but substantially fewer (34%) than in d14 or d0 dox cells (Figures 2B and 2D). Other observations indicate that this difference is because differentiated cells require more than one week of XIST expression to recruit the H3K27me3 modification, which is still ongoing at one week but complete by two weeks (Figure 2B and 2D and Figure S2A). This contrasts with human and mouse pluripotent cells in which chromosome silencing is essentially complete in 4–5 days (Chaumeil et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2013; Wutz and Jaenisch, 2000). We note, however, that our earlier observations using the inducible mouse ES cell system (Wutz and Jaenisch, 2000) suggested that differentiated mES cells could also trigger a hallmark of chromosome silencing (loss of Cot-1 hnRNA) but only after 10–14 days (unpublished data). Results here indicate that differentiated neural cells retain some competence to induce heterochromatin changes but suggest this should be examined over a longer-time frame.

While not our focus here, the longer timeframe likely provides greater temporal resolution of distinct steps, and, importantly, clearly shows H2AK119ub1 enrichment precedes H3K27me3. This supports a recent report in mouse that PRC1 acts before PRC2, contrary to earlier paradigms (Almeida et al., 2017; Brockdorff, 2017).

XIST induces chromosome 21 transcriptional silencing in neural cells

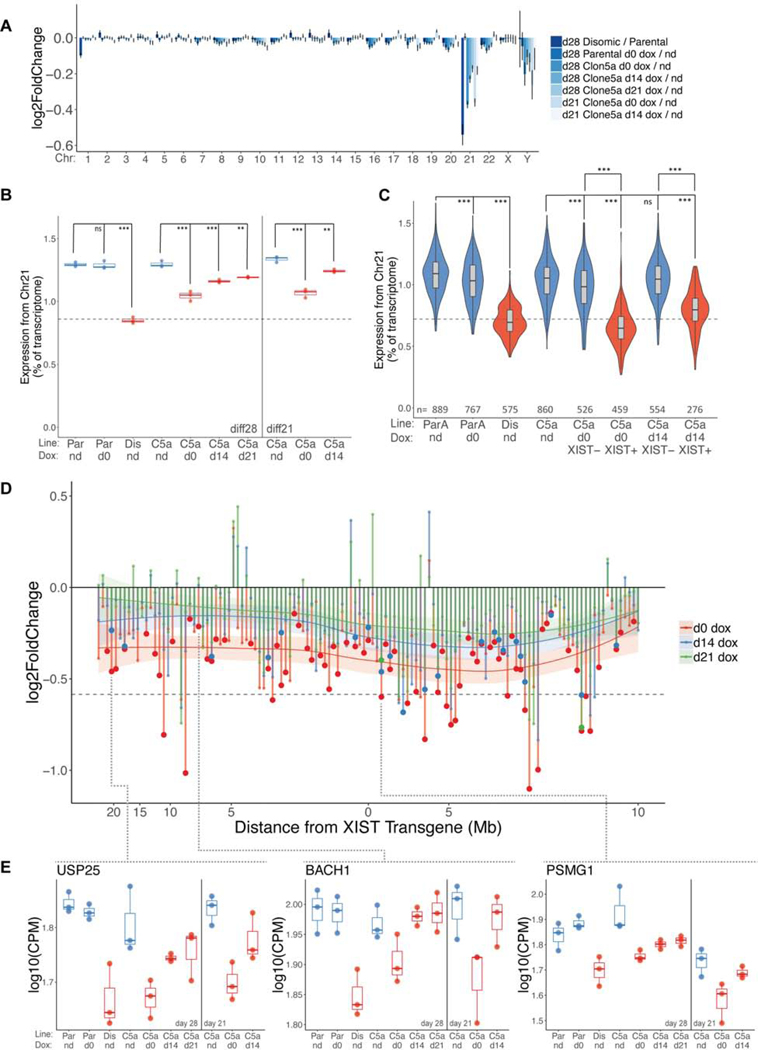

Next, we used RNAseq to quantify chr21 silencing in cultures examined at diff21 and diff28, with XIST induced at several stages of differentiation. As a benchmark for full chr21 dosage compensation, we included comparison of a parental (trisomic) line to an isogenic disomic subclone. First, we examined the effectiveness of silencing for chr21 genes in d0 dox neural cells. Results show a clearly significant decrease in chr21 RNAs in samples treated with dox (Figure 3B), but not in dox-treated parental cells lacking XIST (Figure 3B), or on other chromosomes (Figure 3A). While a 1.5-fold decrease would be the theoretical expectation for full silencing if all cells expressed XIST, only ~60% of cells are XIST+ (Figure 2C), hence the decrease in chr21 transcript levels is less than for the comparison to trisomic and isogenic disomic cells.

Figure 3:

Transcriptional chromosome 21 repression at all time points of XIST initiation. a) Bar graph of bulk RNAseq data of mean log2 fold change at diff28 for all detected genes on each chromosome for each 3 vs. 3 comparison. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Note: Y chromosome data represents only 9 detected genes. b) diff21 and diff28 bulk RNAseq data. Fraction of normalized chr21 reads over all reads for each sample. n=3 independent differentiations for each condition. Dashed line represents a 33% drop in chr21 transcription from mean parental level. Samples colored in blue are trisomic; samples colored in red are disomic or functionally disomic (XIST+). c) Violin plots of scRNAseq data at diff28 showing median (horizontal line), interquartile range (rectangular box), 95% confidence interval, and the kernel probability density at each value. For each cell, the fraction of UMIs from chr21 is divided by total UMIs to determine expression from chr21. Number of cells in each sample is provided. d) Bulk RNAseq fold change between indicated comparisons for all chr21 genes with FPKM>1 and normalized average read count >10 plotted against ranked chromosomal position. Approximate chromosomal distance in megabases (Mb) relative to the XIST transgene locus is indicated on X-axis. Local average (LOESS) for each comparison is indicated by solid horizontal curves with 95% confidence intervals. Dotted horizontal line indicates 1.5-fold change. Significant differential expression (FDR ≤ 0.1) is indicated by larger dots. e) Dot plots of all samples for 3 selected chr21 genes demonstrating various silencing kinetics. Dotted lines indicate each gene’s position in (d). **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Par, parental trisomic line; ParA, parental subclone A; Dis, disomic; C5A, Transgenic Clone 5a; nd, no dox; d0, day 0 dox initiation; d14, day 14 dox initiation; d21, day 21 dox initiation.

Importantly, addition of dox at later differentiation stages also leads to significant repression of chr21 genes (Figure 3B). This is not driven by a few highly expressed genes, as genes across chr21 are repressed in d14 dox cells examined at diff28, and substantial repression still clearly occurs in d21 dox cells induced for just one week (Figure 3D). These results demonstrate that XIST can achieve substantial dosage compensation of trisomy 21 in differentiated neural cells.

To more precisely quantify the degree of silencing and untangle it from the proportion of cells expressing XIST, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) at diff28 to identify cells confirmed to express XIST RNA. This approach may miss some XIST expressing cells due to the low number of unique RNA molecules (nUMI) identified per cell (median = 9,677) but nonetheless will identify a population clearly expressing XIST. This approach demonstrated that by diff28, XIST+ d0 dox cells have decreased chr21 expression by nearly one-third (31%) compared to the same cells not treated with dox (Figure 3C). This is essentially the decrease expected for complete silencing of one chr21 and remarkably close to to the 32% decrease between the disomic and trisomic cell lines. In contrast, cells in which XIST RNA was not detected (XIST-) showed a much smaller (7%) reduction for chr21, reflecting a small subset of false negative XIST expressing cells.

Next, we used scRNAseq to examine the extent of silencing in the XIST+ population induced at d14. In this case, XIST+ cells at diff28 clearly showed substantial repression of chr21 mRNAs (Figure 3C), although this silencing was incomplete (55% of reduction seen in d0 dox cells). The less complete silencing may reflect reduced developmental competence to respond to XIST, or the shorter period of XIST expression (4 vs 2 weeks). Somewhat more silencing at diff28 compared to diff21 in d14 dox cells (Figure 3B) suggested that increased duration of XIST RNA allows more chromosomal silencing, which we test more directly below.

These results demonstrate that XIST induced in iPS cells can produce fully corrected neural cells, which is important for analysis of phenotypic effects, as studied below. Results further show that inducing XIST both 14 and 21 days into neural differentiation still leads to extensive transcriptional repression of chr21 genes. This provides the first demonstration that normal differentiated human cells retain substantial, unexpected epigenetic plasticity to respond to XIST and repress a chromosome.

Gene-specific analysis provides insights into silencing dynamics and fundamental dosage balance

We examined specific genes to better understand the dynamics of XIST-mediated gene silencing, first to determine whether there are distinctly early versus late silencing genes. Visual inspection of data identifies genes with distinct patterns of silencing kinetics. For example, with later dox addition, USP25 and BACH1 show modest to absent repression, whereas PSMG1 is significantly repressed at all dox addition timepoints (Figure 3E). To evaluate this systematically for more genes we quantified the ratio of the fold changes (in XIST+ versus XIST- cells) in d0 dox and d14 dox cells using the diff28 scRNAseq data. A ratio of one, as for the CSTB gene, indicates the same degree of silencing in d0 dox and d14 dox cells (Figure 4A–B). Many genes are at or near a ratio of one, however several are substantially less repressed with XIST induced later. Hence, there are kinetic differences between genes, which did not correlate with linear distance from the XIST transgene (Figure 4A).

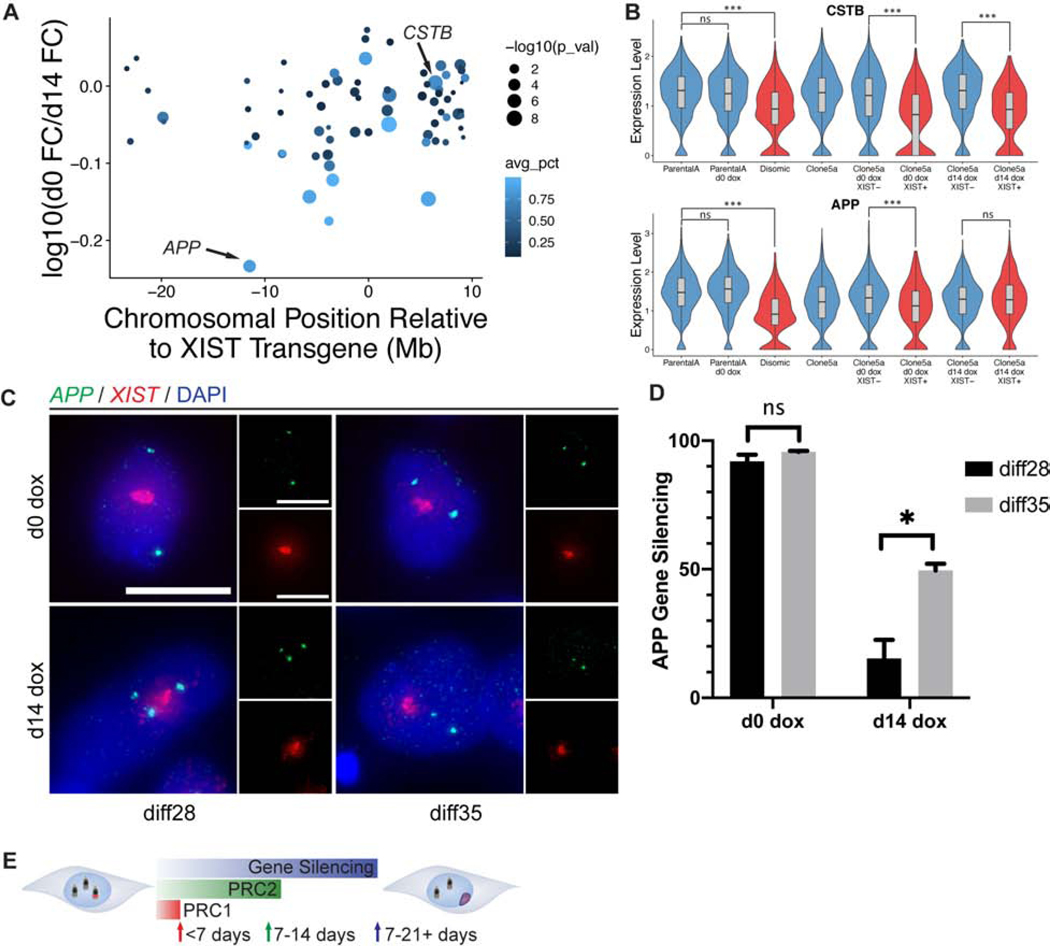

Figure 4:

Gene-specific analysis provides insights into silencing dynamics and fundamental dosage balance. a) Difference in fold-change between d0 and d14 dox conditions plotted against chromosomal location relative to the XIST transgene locus. Each dot represents a gene; the size of each dot is -log10(p-value) for d0 dox comparison (larger dots are more significant). Color (avg_pct) denotes the fraction of cells in which each gene is detected in the d0 dox sample. Only genes demonstrating some degree of repression (>0.1 log10 FC) are plotted. b) Violin plots of expression level for CSTB and APP in each sample sequenced by sc-RNAseq. **FDR ≤ 0.01, ***FDR ≤ 0.001, ns = not significant c) Representative images of RNA FISH for APP and XIST in diff28 and diff35 cells in d0 dox and d14 dox conditions. Micrographs are maximal intensity projections of 3D z-stacks. Scale bars are 10μm. Insets are single channel images. d) Quantification of silencing of transcription foci in (c) for the APP gene as described in methods. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n=2 independent differentiations, with 293–473 cells scored per sample (median = 400) *p ≤ 0.05; unpaired Student’s t-test. e) Schematic indicating temporal order of steps in chr21 silencing process as seen in differentiated cells.

Interestingly, APP stands out for its particularly large difference in silencing between the two conditions (Figure 4A–B). APP and CSTB were detected in similar cell numbers, illustrating that silencing dynamics do not necessarily correlate with expression levels. Given that APP was especially late to silence, we tested whether increased APP silencing occurs if the length of XIST expression in d14 dox cells was extended by using RNA FISH to examine gene silencing at diff28 and diff35. Direct visualization of nuclear RNA transcription foci associated with each active allele allows assessment of transcriptional silencing in each cell (Jiang et al., 2013; Xing et al., 1993), and avoids effects of mRNA half-life. Silencing of APP transcription foci is essentially complete in d0 dox cells at diff28 or diff35 (Figure 4C–D). In contrast, in d14 dox cells, APP silencing is low at diff28 but increases markedly by diff35. This affirms that when XIST is induced in differentiated neural cells the silencing process (for some genes) is still ongoing two weeks later at diff28.

Surveying gene-specific changes on chr21 also makes a fundamental point about XIST biology: there is a striking absence of persuasive examples of genes that “escape” repression by XIST RNA, in contrast to numerous X-chromosome genes that escape silencing (reviewed in Carrel and Brown, 2017). The full capacity of autosome silencing is best revealed by analysis in trisomic cells (which avoids selection against silencing) and compares favorably to the difference between trisomic and disomic cell lines, as shown in Figure S3A, indicating that essentially all expressed genes are repressed by XIST. The 31% reduction in chr21 transcripts compared to 32% for the trisomy/disomy comparison (Figure 3C), further supports that there is negligible if any escape from silencing of chr21 genes. Interestingly, this quantitative RNAseq also indicates there is little if any natural “feedback” regulation of the chromosomal imbalance.

This data also shows a few chr21 genes are clearly repressed by XIST yet unexpectedly expressed higher in the disomic versus trisomic cells (e.g. TSpear-AS1, Fig S3C). Similarly, surprisingly large differences for some genes between trisomic and disomic subclones indicates greater variability unrelated to trisomy 21 between two isogenic cell lines. Induced chr21 silencing in otherwise identical cells can avoid variability between cell lines and cultures, providing a tightly controlled system to investigate trisomy 21 effects on cell function and development, an advantage important to experiments described below.

In sum, differentiated neural cells retain substantial epigenetic plasticity to respond to XIST and repress chromosome-wide transcription. The multifaceted silencing process was found to take longer (~2–3 weeks) in differentiated cells (Figure 4E), but, most critically, still occurs.

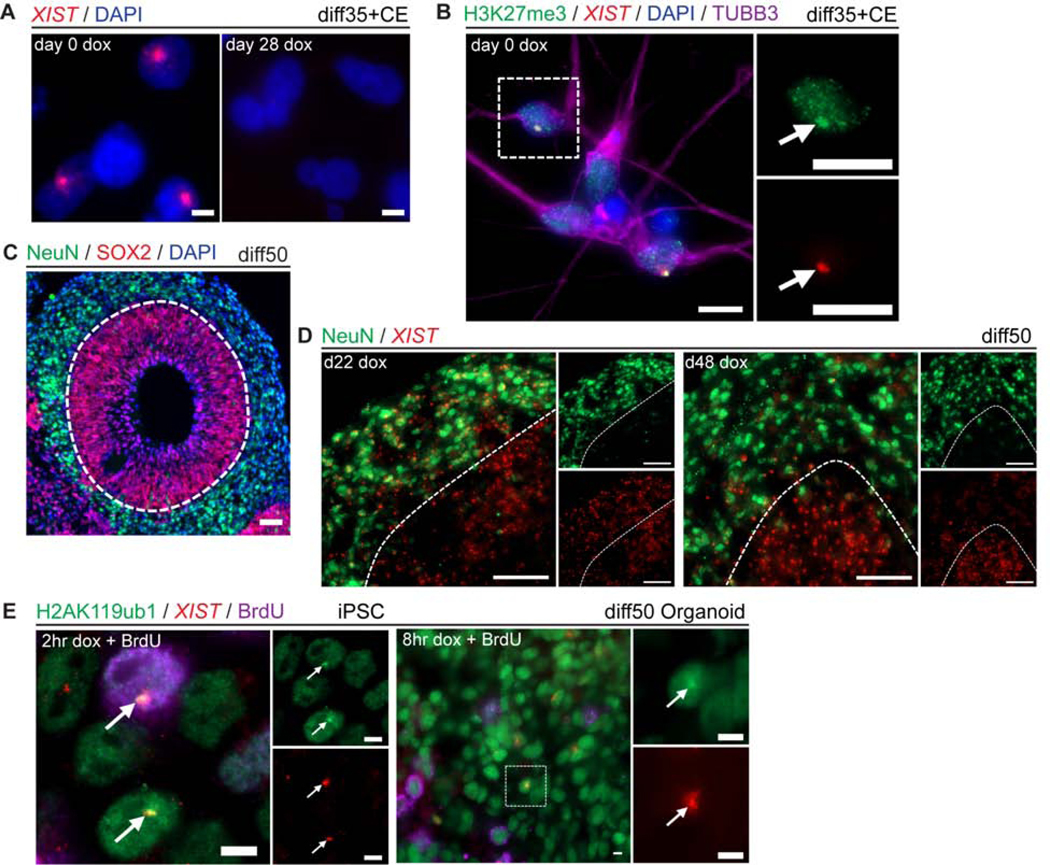

XIST produces dosage corrected trisomic neurons

The scRNAseq analysis demonstrates that this system can readily produce XIST+ trisomic neurons and NSCs with one silenced chr21 (Figure S4A–B), with dosage correction essentially equivalent to removing one chr21 from the cell. Interestingly, even when dox is added later at d14 and silencing is less complete at diff28 when scRNAseq was done, chr21 repression is as extensive in post-mitotic neurons as in cycling NSCs. Given that the prolonged process requiring ~2–3 weeks, this indicates that cells that became post-mitotic neurons continued to support the silencing process, similar to cycling NSCs. However, we also wanted to address whether XIST RNA could still properly coat the chromosome and trigger initial heterochromatin modifications in neurons that would no longer go through S-phase. Hence, we attempted to initiate XIST transcription after inducing a more pure population of neurons using compound E (Figure S4C–D) (Ogura et al., 2013). As expected, d0 dox neurons had robust XIST RNA (Figure 5A) associated with heterochromatin marks (Figure 5B). However, if dox was added after neuron differentiation, cells surprisingly did not even show a transcription focus for XIST RNA (Figure 5A), indicating that transgene activation by dox becomes blocked in our postmitotic neurons.

Figure 5:

Neurons support continued XIST expression to maintain silent chromatin provided the transgene is activated in the NSC stage. a) RNA FISH for XIST in diff35 cells treated with compound E (CE) at diff21 and induced with dox at diff0 or diff28. DAPI counterstain in blue. Scale bars are 5μm. b) Combined RNA FISH for XIST and IF for H3K27me3 and TUBB3 in diff35 cells treated with CE at diff21. Insets are magnified single channel images of outlined area. Scale bars are 10μm. Arrows point to XIST RNA paints. c) IF of day 50 sectioned forebrain organoid for NeuN and SOX2. Dashed white line delineates NSC-containing SOX2+ VZ-like area and neuron containing NeuN+ area. Scale bars are 50μm. d) Combined RNA FISH for XIST and IF for NeuN in transgenic forebrain organoids. Micrographs are maximal intensity projections of 3D z-stacks. Scale bars are 50μm. e) Combined RNA FISH for XIST and IF for H2AK119ub1 and BrdU with concurrent addition of dox and BrdU in both iPSCs and diff50 organoids. Insets for the iPSCs are single channel images; insets for organoid are magnified single channel images of the outlined area. Scale bars are 5μm. Arrows point to XIST RNA paints.

To further investigate this phenomenon, we examined forebrain organoids differentiated for 50 days, which have a clearly demarcated “ventricular-like” zones (VZ) containing NSCs which give rise to the distinct surrounding region of differentiated neurons (Figure 5C). We induced organoids with dox at diff48 for just two days prior to examination, thereby minimizing time for NSCs to form neurons after XIST induction. In this case, nearly all XIST+ cells were in the VZs rather than surrounding neurons (Figure 5D). In contrast, if dox was begun at diff22, the diff50 organoids contained many XIST+ cells in both the VZ and in the surrounding neurons (Figure 5C–D). Together, these results demonstrate that post-mitotic neurons can continually express and localize XIST RNA and maintain comprehensive chr21 silencing, even though the dox-inducible transgene needs to be activated prior to terminal differentiation, likely due to DNA methylation of the tetracycline response element with differentiation (Gödecke et al., 2017).

As an alternative approach to address whether XIST RNA requires S-phase to coat the chromosome and initiate recruitment of heterochromatin marks, we induced XIST concurrently with BudU labelling of replicating DNA in both iPSCs and diff50 forebrain organoids. In both, there were cells that had not undergone DNA replication (BrdU-) but had a well-localized XIST RNA paint with clear recruitment of the H2AK119ub1 heterochromatin mark (Figure 5E). Hence, XIST RNA does not strictly require S-phase to initiate the chromosome remodeling process, suggesting that the lack of cell cycling in neurons does not preclude XIST function.

Together, these results demonstrate that XIST can produce fully dosage compensated neurons with no reduction in silencing levels in neurons compared to NSCs, despite a technical inability to dox-induce our XIST transgene in these neurons. Results also suggest a path for potential future studies of XIST-mediated chromosome silencing in trisomic organoids.

XIST RNA enhances neuron formation indicating correction of a neurodevelopmental deficit

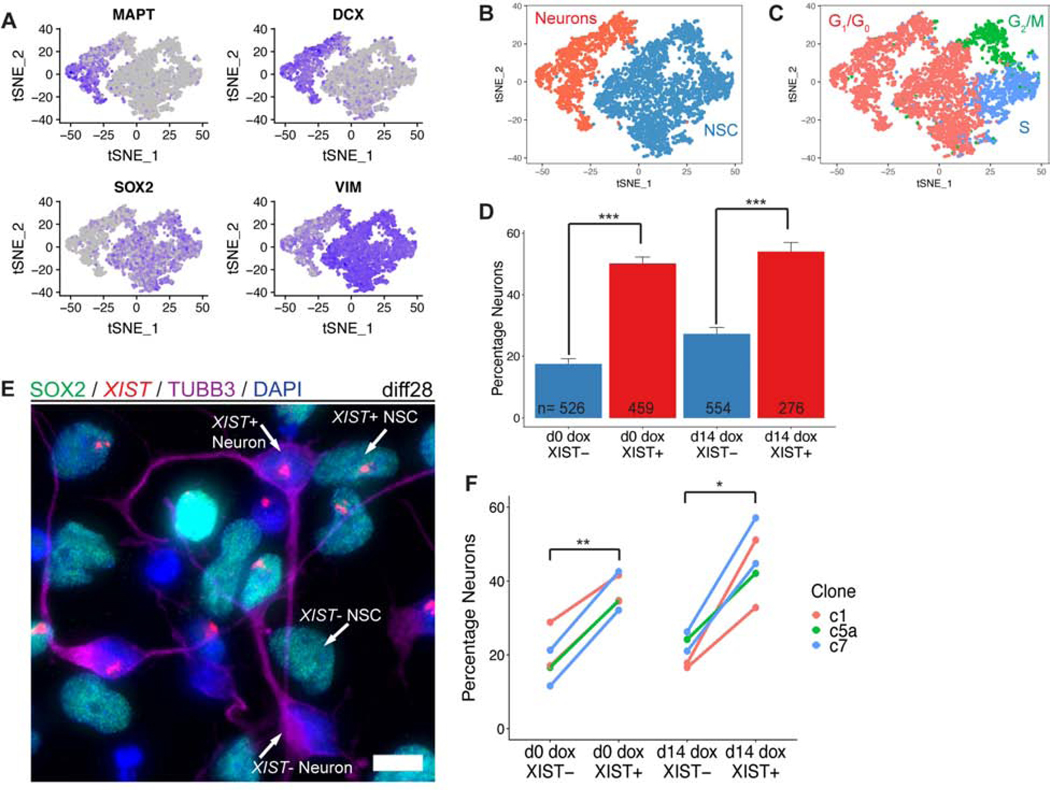

scRNAseq was instrumental to quantify chr21 gene silencing in diff28 neurons and NSCs, however this approach could also be advantageous to determine if trisomy 21 expression impacts neural differentiation at this stage, because it compares cells within the same sample sorted for XIST expression. This strategy minimizes variability between lines that has been noted in other studies using patient-derived iPSCs (Liang and Zhang, 2013; Soldner and Jaenisch, 2012). Therefore, we examined the single-cell data to address whether XIST+ cells were distinct from XIST- cells beyond the difference in chr21 expression.

As described above, diff28 cultures were histologically determined to be a mixture of NSCs and neurons, and scRNAseq confirmed these two major cell-type clusters based on markers such as SRY-box 2 (SOX2), Vimentin (VIM), Doublecortin (DCX), and Tau (MAPT) (Figure 6A–B). Further affirming this, the NSC cluster contained ~40% of cells predicted to be in G2/M and S-phase, whereas the neuron cluster contained only ~2% cycling cells (Figure 6C).

Figure 6:

XIST expressing cells are more likely to be neurons than cells that do not express XIST. a) t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot of diff28 scRNAseq data for neuron- (MAPT and DCX) and NSC- (SOX2 and VIM) specific genes. Gray is lowly expressed and purple is highly expressed. Each dot represents a single cell. b) t-SNE plot colored for cell type classification. c) t-SNE plot colored for predicted phase of cell cycle. d) Fraction of cells in Clone5a d0 and d14 dox scRNAseq samples identified as neurons separated based on XIST expression. Error bars are SE. e) Combined RNA FISH for XIST with IF for SOX2 and TUBB3 in day 28 cells. Example XIST+/−;NSC/Neuron cells are labeled. Micrograph is a maximal intensity projection of a 3D z-stack. Scale bars are 10μm. f) Quantification of (e) for 1–2 differentiations of three transgenic clones. For statistical comparisons, differentiations of the same clone were averaged together and treated as one sample (n=3). Lines connect data points derived from the same sample. Between 419–1311 cells were analyzed for each sample (median = 868). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01; Student’s paired T-test.

Next, we analyzed the proportion of XIST+ cells in the neuron cluster compared to XIST- cells in the same sample. Surprisingly, this revealed that XIST+ d0 dox cells were significantly more likely to be neurons compared to XIST- cells (Figure 6D). This is despite the finding described above that neurons cannot initiate XIST expression in this dox-inducible system, and evidence that the tetracycline transactivator transgene (TET3G; required for XIST expression) is more highly expressed in NSCs (based on a dox-treated trisomic control line that contains just the TET3G transgene) (Figure S5A). These results show that DS cells in which one chr21 was silenced produced a higher proportion of neurons relative to NSCs. Given the potential importance for understanding DS neuropathology, this merited further investigation

The reduced fraction of trisomic cells that form neurons could have its root at any point during the 28-day differentiation time course, and the inducible XIST system makes it possible to investigate this. Thus, we examined whether this phenotypic difference could be reproduced by initiating XIST expression at diff14. Remarkably, even when XIST expression was not initiated until midway through the time-course, XIST+ cells were still significantly more likely to form neurons, and to the same degree as d0 dox cells (Figure 6D). This indicates that the developmental step which underlies the reduced proportion of neurons occurs after diff14,and likely after diff21, given the time required for chromosome silencing. This was further evidenced by evaluating differentiation markers in cultures differentiated for 14 or 21 days (+/− dox at d0 or d14) which showed no differences in the proportions of neurons and NSCs at any of the earlier timepoints (Figure S1C). Hence, this suggests that the specific step impacted is at or very near the wave of terminal differentiation after diff21.

In this study, we included one trisomic and one disomic cell line primarily as a benchmark for full chr21 gene silencing, however we noted that no difference was seen in the proportion of neurons produced between these two isogenic lines. To rule out any possibility of this finding resulting from technical limitations of scRNAseq or in analysis of one transgenic line, we tested the production of neurons in cultures of multiple transgenic lines using a different single-cell approach which combines RNA FISH for XIST RNA with IF for SOX2 and TUBB3 (Figure 6E). This was done in three independent transgenic clones each differentiated independently 1–2 times including both d0 dox and d14 dox conditions. In accordance with sequencing results, XIST+ cells were again more likely to become neurons compared to XIST- cells (Figure 6F). This was consistent for all three clones and, importantly, occurred to similar degrees at both dox addition timepoints.

As shown in Figure S6A, XIST+ neurons did not cluster separately from XIST- neurons, suggesting that at this stage XIST did not specifically impact formation of different neural subtypes. Markers of excitatory and inhibitory neurons also do not form strong clusters (Figure S6B-C), consistent with immaturity of newborn neurons.

Using this tightly controlled inducible system in multiple transgenic lines analyzed by two different approaches, results strongly suggest that trisomy 21 is associated with a dysregulation in neurogenesis that delays neuron formation. This occurs after NSCs are formed but prior to terminal differentiation of neurons. Together, the facts that we are comparing functionally disomic and trisomic cells within the same sample, that we are analyzing a difference in the proportion of neurons to NSCs rather than total neuron number, and that this proportion is altered even when XIST is initiated half-way into the differentiation protocol, all suggest that neuron formation is enhanced in XIST+ cells independent of an effect on cell density or proliferation.

Importantly, implicit in this analysis is that this specific neural phenotype can be rescued by expression of XIST RNA from one copy of chr21.

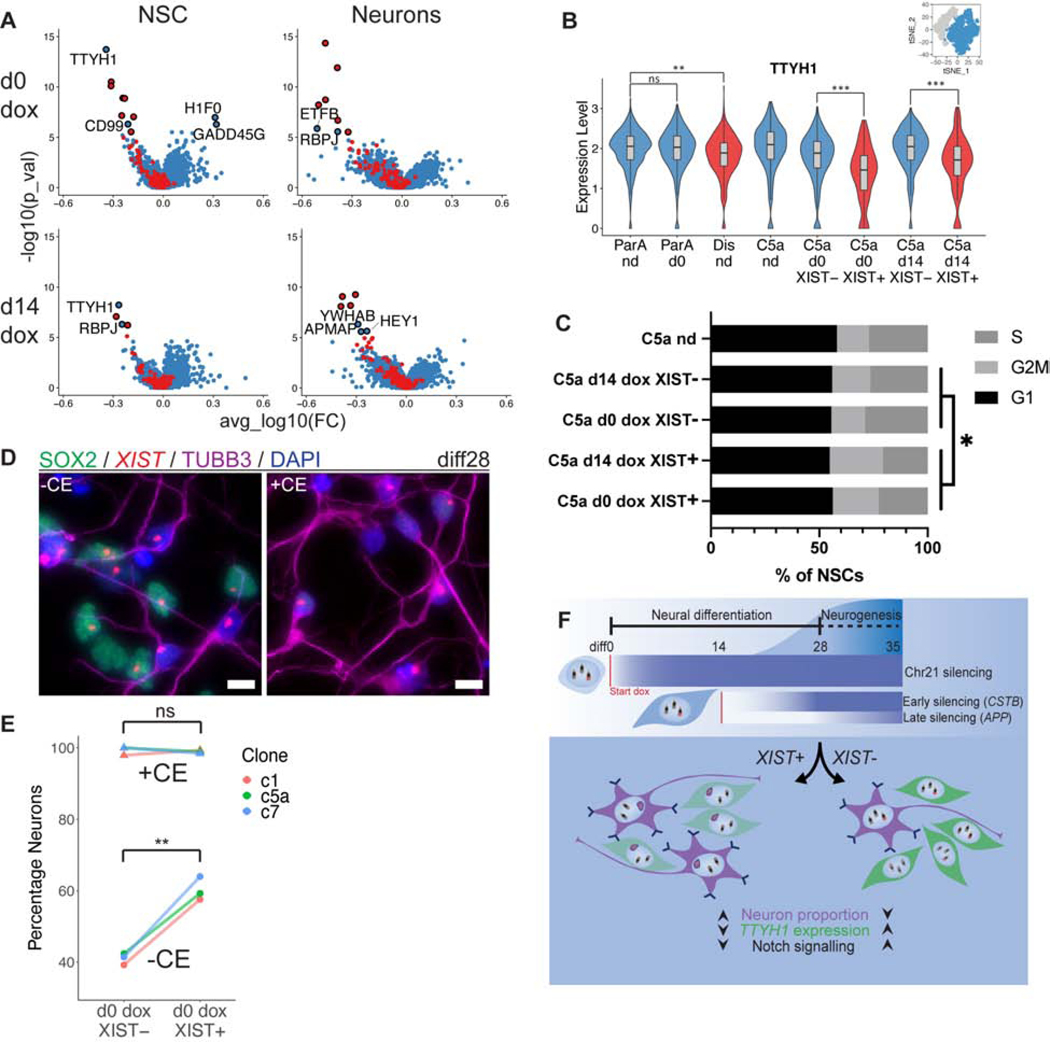

Differential expression of non-chromosome 21 genes implicates elevated Notch signaling

Several studies have examined transcriptomes of trisomic versus euploid tissue from fetal or adult human brain samples (Lockstone et al., 2007; Olmos-Serrano et al., 2016), although those transcriptome differences will reflect down-stream changes in cell-representations or pathologies, as well as variation between non-isogenic samples, rather than more direct effects within specific cells. Our scRNAseq analysis could reveal whether non-chr21 genes are significantly impacted, directly or indirectly, by chr21 dosage in a specific cell population (neuron or NSC). Due to limitations in sensitivity, the scRNAseq data would not necessarily identify all changes in weakly or variably expressed genes, but changes would be identified with higher confidence, with each cell serving as a biological replicate of the trisomic versus functionally disomic (XIST+) state, all within the same culture. Indeed, this analysis identifies a small number of genes which change expression in NSCs and/or neurons as a function of chr21 silencing (Figure 7A). Notably, PANTHER Pathway analysis (Mi and Thomas, 2009; Mi et al., 2017) on the total of 9 unique non-chr21 genes that are differentially expressed identifies “Notch signaling pathway” (accession: P00045) as the only significantly dysregulated pathway (FDR=0.0274). Additionally, the gene Tweety Family Member 1 (TTYH1), recently implicated in Notch signaling (Kim et al., 2018) but not included in Notch pathway annotation, is also differentially expressed in NSCs expressing XIST. A similar more modest difference is seen between the trisomic and disomic lines (Figure 7B), and there was no difference between TET3G+ and TET3G- NSCs in the trisomic parental subclone treated with dox (Figure S5B).

Figure 7:

Non-chromosome 21 differential expression identifies altered Notch pathway genes. a) Volcano plot of results from Wilcoxon rank-sum test between XIST+ and XIST- cells in NSC and neuron clusters for d0 and d14 dox samples examined at diff28 in scRNAseq dataset. Chr21 genes are in red, and all other genes are in blue. Circled dots are significantly differentially expressed (FDR<0.05). Non-chr21 DE genes are labeled. “Dox effect” genes found to be DE between ParA nd and parA d0 dox samples and transgenes were removed from the plots. b) Expression levels of TTYH1 in NSCs of all samples sequenced. ParA, parental subclone A; Dis, disomic; C5A, Transgenic Clone 5a; nd, no dox; d0, diff0 dox initiation; d14, diff14 dox initiation. c) Percentage of NSCs in each estimated phase of the cell cycle for XIST transgenic samples from scRNAseq data. *p ≤ 0.05, Chi-squared test. An effect of Notch on G2/M has been reported in some contexts (Kim et al., 2016; Nègre et al., 2003) and may be suggestive that NSCs in G2/M will become post-mitotic G0 neurons (TUJ1+) after this final cell-cycle phase. d) Combined IF and RNA FISH of diff28 XIST transgenic cells plated on diff25 and treated with CE for 3 days. e) Quantification of (d) for three transgenic clones (n=3). Lines connect data points derived from the same sample. Between 133–291 cells were analyzed for each sample (median = 183). **p ≤ 0.01, Student’s paired T-test. f) Schematic of experimental design and major results. Chromosome silencing is prolonged in differentiated cells and has variable kinetics between genes. XIST+ cells in both d0 and d14 dox conditions have increased neuron proportions, decreased TTYH1 expression in NSCs, and increased Notch pathway gene expression compared to XIST- cells.

It is known that the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) interacts with its effector, RBPJ (reduced by silencing trisomy 21) to promote cell proliferation, and reduction in Notch signaling prolongs the cell-cycle and decreases NSCs in S-phase (Borghese et al., 2010; Li et al., 2012). Hence, we examined the NSC cluster and indeed found a smaller fraction of XIST+ NSCs in S-phase, both with d0 and d14 dox, consistent with an impact at the terminal differentiation step (Figure 7C).

These findings further suggest that elevated Notch signaling prolongs the proliferative phase of trisomic NSCs, thereby delaying terminal differentiation. However, since only about half of XIST+ cells form neurons by diff28, we could not rule out that trisomy 21 has other effects that reduce the competence of NSCs to form neurons. If neuron formation is not blocked but delayed due prolonged cycling of NSCs due to Notch, then inhibition of Notch signaling should overcome differences in neuron formation between trisomic and functionally disomic cells. Therefore, we inhibited Notch signaling in diff25 neural cells using compound E (a γ-secretase inhibitor), which showed that inhibition of Notch erases the difference in XIST+ and XIST- cells (Figure 7D–E). This demonstrates that essentially all trisomic cells can form post-mitotic neurons within just a few days if Notch is inhibited. Collectively, these results provide substantial support for the hypothesis that trisomic cells have elevated expression of Notch signaling genes which maintains them in a proliferative state and thereby reduces the differentiation of NSCs to neurons during a critical window in neurodevelopment.

As summarized in Figure 7F, the effects on neuron formation and non-chr21 gene expression occur similarly whether one chr21 is silenced from the beginning or far into the differentiation process, providing insight into the developmental timing of these effects. To our knowledge, this is the first data able to identify genes that likely reflect ongoing functional effects of trisomy 21 on expression of non-chr21 genes in a given neural cell type.

Discussion

The results presented here have broad implications for basic developmental biology, DS neurobiology, and for potential translational applications of a unique non-coding RNA, XIST. This study addresses a critical question regarding the epigenetic plasticity of cells to respond to XIST, with encouraging results which heighten both the experimental power and the therapeutic prospects of XIST. Our findings demonstrate that the chromosome silencing process still occurs in differentiated cells, contrary to the expectation that pluripotency factors are required. We show that the process is more prolonged, which could explain earlier findings suggesting a very strict developmental window for initiation of chromosome silencing. We then use this system for single cell analyses of otherwise identical cells, with and without XIST-mediated dosage compensation induced from pluripotency or later in differentiation. Results provide strong evidence that over-expression of chr21 genes confers a developmental delay in terminal differentiation of NSC to neurons. These findings demonstrate the value of this approach to investigate the human developmental biology of DS. Moreover, these results overcome a perceived barrier to developing XIST as a potential therapeutic for DS and other trisomies, and further support the effectiveness of chromosome silencing to mitigate cell phenotypic effects of trisomy.

It has been thought that XIST cannot induce chromosome silencing in somatic cells, with the exception of some limited effect in some cancer cells or an unusual regaining of competence specific to a subset of mouse hematopoietic cells. By thoroughly re-visiting this key point, our results demonstrate that normal differentiated human neural cells retain unexpected “chromatin plasticity” to induce large-scale heterochromatin formation in a process that normally begins in the inner cell mass. While not directly tested here, these results bode well for use of XIST in other cell-types. Given that XIST triggers multiple repressive chromatin modifications, the redundancy of the process may still provide transcriptional repression even if not all chromatin modifying enzymes are present at substantial levels in differentiated cells. The longer time required for chromosome silencing in differentiated cells was not anticipated from the rapid ~4 day process when initiated in pluripotent cells, which could explain why gene silencing was not observed after XIST was expressed for a shorter period when mouse ESC induced to differentiate for just two days (Wutz and Jaenisch, 2000).

A complication we encountered using ectopic promoters to drive XIST expression is the common phenomenon of transgene silencing, especially upon differentiation (Gödecke et al., 2017; Huebsch et al., 2016; Laker et al., 1998; Oyer et al., 2009; Xia et al., 2007). In our system we have determined that, depending on cellular context, this can be due to silencing of the tetracycline transactivator transgene (on chr19) or the tet-response element/XIST locus on chr21. This issue could have also influenced results of a previous study in which mice were fed dox to induce an Xist transgene, with cell lethality the read-out for Xist function (Savarese et al., 2006).

Neurons maintain XIST expression and remarkably complete chr21 silencing, yet the dox-inducible system was blocked in neurons unless it was already activated in NSCs prior to terminal differentiation. Despite this technical difficulty, we were able to show even with later XIST induction, neurons expressing XIST RNA show no reduction in chr21 dosage-correction relative to NSCs. We note other precedents for epigenetic regulation in neurons, such as or activity-mediated neuronal plasticity (Ma et al., 2009), or the conversion of neurons from one distinct subtype to another (Rouaux and Arlotta, 2013; Ye et al., 2015).

We believe the ability to discern a modest but reproducible developmental delay in neurogenesis in vitro, as demonstrated here, may rest on the inducible manipulation of chr21 dosage in otherwise essentially identical cells in the same culture, all of which are exposed to dox. This circumvents epigenetic and genetic variation that is increasingly recognized even between isogenic iPSC clones (Koyanagi-Aoi et al., 2013; Liang and Zhang, 2013; Soldner and Jaenisch, 2012), and allows us to conclude that differences seen are not related to culture conditions or density, suggesting a cell autonomous effect. Importantly, the ability to induce chr21 repression at later stages also makes it possible to examine the timing and reversibility of a developmental defect. Since enhanced neuron differentiation occurred similarly whether XIST-mediated silencing was initiated at diff0 or diff14, the time required for chromosome silencing suggests the chr21 gene(s) involved are either expressed or have their effect closer to terminal differentiation at diff28.

While studies using DS iPS cells have described variable results with neural differentiation (see introduction), some reported hypocellularity in small samples of DS fetal cortex (Guidi et al., 2008; Larsen et al., 2008; Ross et al., 1984), attributed to decreased neuron number. However, the prevalence, developmental timing, and underlying basis for any reduction of neurons in human brains would be difficult to investigate and establish. Using a very different approach to manipulate chr21 expression, results here provide direct evidence that trisomy 21 over-expression causes a neurodevelopmental delay in NSC transition to neurons. Recently, we showed that trisomy 21 silencing (induced from pluripotency) prevents development of DS hematopoietic pathologies involving over-production of megakaryocytes and erythrocytes (Chiang et al., 2018). The contrasting effects of XIST on neuron and hematopoietic cell differentiation are consistent with the distinct clinical effects of trisomy 21 on these systems.

This experimental strategy can also provide insights into target pathways dysregulated by trisomy 21, potentially identifying targets amenable to drug therapies. Of particular interest are the Notch pathway genes that stand out as impacted, since Notch is well-established to regulate the decision of NSCs to terminally differentiate, a role that fits particularly well with the specific cell phenotype identified here. This also fits with our findings that this step can still be “rescued” even in conditions when most gene silencing will not occur until close to terminal differentiation.

The specific neural defects or any involvement of Notch in DS neurodevelopment have remained very unclear, but some transcriptome studies of DS adult brain samples have reported upregulation of Notch signaling genes, and the potential role of specific chr21 genes in Notch signaling has been of interest (Fernandez-Martinez et al., 2009; Fischer et al., 2005; Lockstone et al., 2007). Here we show that TTYH1, as well as known Notch pathway genes HEY1 and RBPJ, are increased in the trisomic state and strongly downregulated after chr21 silencing. This was of particular interest because it was recently reported that Ttyh1 (in normal cells) regulates the Notch pathway to promote maintenance of the NSC state (Kim et al., 2018), and our findings implicate elevated Notch in delaying trisomic NSC differentiation to neurons. The regulation of Notch signaling by Ttyh1 via increased γ-secretase activity (Kim et al., 2018) leads us to raise a potentially very important hypothesis that DS neurodevelopmental deficits could have a common link with neurodegenerative effects, since γ-secretase also promotes the cleavage of APP which forms amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, Notch signaling is also involved in astrogliogenesis (Louvi and Artavanis-Tsakonas, 2006), and aberrations in astrocyte number have been reported in some studies of DS (Chen et al., 2014; Colombo et al., 2005; Mito and Becker, 1993).

Finally, the fundamental finding here that differentiated cells retain substantial epigenetic plasticity is encouraging for the forward-looking prospect that XIST or derived sequences could be developed as a therapeutic strategy, for aspects of DS and potentially the diversity of increasingly recognized smaller duplication disorders (Theisen and Shaffer, 2010). While this study points to a specific step in neural development and implicates a particular pathway, with over 200 genes on chr21 our results do not rule out that other aspects of brain development and function may be impacted. In addition, aneuploidy in general may cause proteomic cell stress due to low-level over-expression of many genes (Bonney et al., 2015; Sheltzer et al., 2012). Therefore, given enormous advances in genome editing and delivery technologies, we continue to advance the prospect that a single gene could target the root cause for a complex chromosomal disorder to potentially mitigate some physiological effects of trisomy 21. We recently showed that XIST can prevent development of a known DS cell pathology and now show that initiation of chromosome silencing does not require pluripotency but is possible in neural cells. Clearly, many challenges remain, including the need for a smaller XIST transgene amenable to delivery methods and the fact that neurogenesis is largely complete prenatally. However, several major aspects of neural development, such as myelination and synaptic pruning, continue long after birth (Silbereis et al., 2016), as does the development Alzheimer’s dementia in most DS individuals (Wiseman et al., 2015).

STAR Methods

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jeanne Lawrence (Jeanne.lawrence@umassmed.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Human cells

The isogenic XIST-transgenic and disomic iPSC subclones were derived and characterized as described in Jiang et al. (2013). The initial DS iPSC parental line (DS1-iPS4) was provided by G.Q. Daley (Park et al., 2008) and is derived from a male with Down syndrome. Clone5a is a subclone of the previously characterized clone5 (Jiang et al., 2013) which was altered for this study to include a second copy of the tetracycline transactivator driven by the CAG promoter in the AAVS1 locus (Addgene plasmid #60431; Sim et al., 2016) in an attempt to minimize transgene silencing with differentiation. All clones except the original parental line contain the TET3G transgene in the AAVS1 locus.

iPSCs were maintained on vitronectin-coated plates with Essential 8 medium (ThermoFisher) at 37°C with 20% O2 and 5% CO2. Cell s were tested periodically for mycoplasma and passaged every 3–4 days with 0.5mM EDTA.

METHOD DETAILS

Neural differentiation

Neural differentiations were performed as previously described (Cao et al., 2017; Chambers et al., 2009) with some modifications. Briefly, iPSCs were dissociated into single cells and plated at a density of 50,000 cells/well in a vitronectin-coated 24-well plate with 10μM of the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (Tocris Bioscience). The next day, media was changed to Neural differentiation media (NDM) consisting of 50% DMEM/F12, 50% Neurobasal, 0.5X Glutamax, 1X N-2 supplement, 1X penicillin/streptomycin (all from ThermoFisher), and supplemented with 2uM DMH1 and SB431542 (both from Tocris Bioscience). After 14 days, cells were broken into clumps after EDTA treatment and cultured in suspension for 7 days in NDM. On diff21 or diff28, neurospheres were dissociated into single cells with StemPro Accutase (ThermoFisher) and plated onto coverslips (Electron Microscopy Sciences) coated with Matrigel (Corning) at a density of 25,000–50,000 cells/coverslip and fed every 2–3 days with Neuron media consisting of Neurobasal, 1X N-2, 0.5X B-27 without vitamin A, 1X penicillin/streptomycin, 1X Glutamax (ThermoFisher), 0.3% Glucose, 10ng/ml GDNF (Peprotech), 10ng/ml BDNF (Peprotech), 10ng/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1μM cyclic AMP (Sigma-Aldrich). Doxycycline diluted in distilled water was added to the culture media starting at various time points at a concentration of 500ng/ml. In cultures where NSCs were synchronously differentiated to neurons, compound E (EMD Millipore) was added for 3 days at diff21 or diff25 at a concentration of 200nM.

Forebrain organoids were generated as previously described (Qian et al., 2016, 2018) with the following modifications: embryoid bodies were formed by dissociated of iPSCs into single cells and re-aggregating in U-bottom 96-well plates (Lancaster and Knoblich, 2014). On diff7, aggregates were transferred to ultra-low attachment 6-well plates (Corning) for Matrigel embedding, and on diff14 the plates were moved to an orbital shaker set at ~100rpm.

Cell fixation, RNA FISH, and immunofluorescence

For iPSC and monolayer neural culture, cell fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) was performed as previously described (Byron et al., 2013). Forebrain organoids were fixed for 30min in PFA at room temperature, washed three times with PBS, and cryopreserved in 30% sucrose/PBS at 4°C overnight. Fixed organoids were embedded in O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek), frozen in an ispropanol/dry ice slurry, and sectioned at 14μm on a cryotome. Sections were attached to Superfrost Plus slides (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and stored at −20°C until staining. Prior to staining, sections were rehydrated in PBS for 5min, and detergent extracted in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Roche) for 3min.

RNA FISH and IF were performed as previously described (Byron et al., 2013; Clemson et al., 1996). For RNA FISH and combined RNA FISH/IF in iPSCs and monolayer neural culture, detergent extraction was performed prior to fixation. For IF alone, fixation was performed prior to detergent extraction. The XIST probes used were G1A (Addgene plasmid #24690; Clemson et al., 1996) and a Stellaris FISH probe (Biosearch Technologies, SMF-2038–1), which was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The APP probe is a BAC from BACPAC resources (RP11–910G8). DNA probes were labelled by nick translation with either biotin-16-dUTP or digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche). For simultaneous IF and RNA FISH, cells were immunostained normally with the addition of RNasin Plus (Promega) to the incubation buffer and fixed in 4% PFA prior to RNA FISH. The primary antibodies used in this study are provided in Supplementary table 1. The conjugated secondary antibodies used in this study were Alexa Fluor 488, 594, and 647. BrdU staining was performed after RNA FISH and subsequent fixation by incubating coverslips or slides at 80°C in 70% formamide in 2X SSC for 5min (coverslips) or 30min (cryosections on slides) followed by dehydration in 70% and 100% cold ethanol for 5min each and standard IF.

RNA isolation, cDNA library preparation, and high-throughput sequencing

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (ThermoFisher) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were cleared of contaminating genomic DNA by DNAse I (Roche) treatment for 1hr at 37°C. RNA cleanup and DNAse I removal was performed using RNeasy MinElute columns (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Clean RNA was assessed for quality on an Advanced Analytical Fragment Analyzer, and all samples had an RQN > 7.5. 100ng of RNA per sample was used to prepare mRNA strand-specific sequencing libraries using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® in conjunction with the NEBNext® Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module and NEBNext® Multiplex Oligos for Illumina® (New England Biolabs). Sequencing was performed by the UMass Medical School Deep Sequencing Core Facility on the Illumina HiSeq4000 platform to a depth of ~8 million reads/sample.

Reads were aligned to the hg19 human genome build (GRCh37) using hisat2 v2.0.5 (Kim et al., 2019). Reads were counted to genes using the featureCounts function of the subread package (v1.6.2). Within R, the DEseq2 package (Love et al., 2014) was used to normalize reads between samples and determine significantly differentially expressed genes. Significance in Figure 3D was determined by performing multiple comparison correction on all expressed chr21 genes (n=125) and using an FDR of <0.1. The ggplot2 package was used to generate most graphs.

Single-cell RNA sequencing

On diff28, neurospheres were dissociated with StemPro Accutase (ThermoFisher) and passed through a 40μm strainer to remove remaining clumps. Cells were washed twice in PBS + 0.4% BSA, counted and assessed for viability (>80%). Cells were then processed using the 10x Genomics Chromium™ Single Cell 3’ Library and Gel Bead Kit v2 per manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed by the UMass Medical School Deep Sequencing Core Facility on the Illumina HiSeq4000 platform. Alignment, filtering, barcode counting, and UMI counting was performed using the Cell Ranger pipeline (10x Genomics - v2.1.1) using the hg19 reference genome which was altered to include the TET3G transgene sequence. Further normalization, filtering, and analysis was performed using the Seurat R package v2.3.4 (Butler et al., 2018). Cell cycle scoring was performed as previously described (Tirosh et al., 2016).

Microscopy

Cells were visualized using a Zeiss AxioObserver 7, equipped with Chroma multi-bandpass dichroic and emission filter sets (Brattleboro, VT), with a Flash 4.0 LT CMOS camera (Hamamatsu). Images were minimally corrected for brightness and contrast to best represent signals observed by eye using ZEN software (v2.3 Blue, Zeiss). Where indicated, 3D z-stacks of several focal planes were computationally deconvolved and a maximal image projection was created using ZEN software in order to visualize all signals in one image.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Microscopy quantification

For scoring of heterochromatin marker association with XIST signal, we examined at least 8 random fields in three independent differentiations of one transgenic cell line per condition. For APP gene silencing, we examined at least 6 random fields in two independent differentiations per condition, and silencing was assessed using the following formula, which corrects for variable hybridization efficiency between samples: Degree of silencing = 100 * (1 - (fraction of XIST+ cells with 3 APP foci / fraction of XIST- cells with 3 APP foci)). For scoring of neuron/NSC cell type, TUBB3+ cells were counted as neurons, SOX2+/TUBB3- cells were counted as NSC, and SOX2-/TUBB3- cells were not counted. After a cell was determined to be a neuron or NSC, its XIST status was assessed. For these experiments, 5 random low-power fields from 3 different cell lines differentiated 1–2 times were examined for each condition.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed and graphs generated using GraphPad Prism 8 and R. Data are shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Specific statistical tests used, values of n, and precise definitions of n are included in each figure legend. In general, beyond RNAseq analysis which was performed as described above, all comparisons for groups of three or more were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Pairwise sample comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

The RNAseq data generated during this study, both bulk and single cell, are available at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) GSE125839.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

XIST expression fully corrects trisomy 21 dosage in neurons and NSCs

Neural cells retain epigenetic plasticity to initiate chromosome-wide repression

Dosage correction by XIST promotes differentiation of trisomic NSCs to neurons

Manipulation of chr21 dosage implicates elevated Notch signaling in Down syndrome

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Lawrence lab for thoughtful discussion, critical analysis, and helpful comments on the manuscript. Jun Jiang and Jen-Chieh Chiang were instrumental for learning of iPS culturing techniques and experimental guidance. We appreciate Dr. Oliver King’s expert advice and helpful discussions regarding statistical analysis of our sequencing data. Drs. Su-Chun Zhang, Anita Bhattacharyya, and members of their labs for lending their expertise on neural differentiation protocols and experimental advice. René Maehr’s lab provided technical advice on scRNAseq and access to 10X Chromium equipment. We appreciate the support of NIH – R35GM122597, R01HD091357, and R01HD094788 to J.B.L.; F30HD086975 and T32GM107000 to J.T.C. J.B.L. also appreciates prior supplemental support from The John Merck Fund.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

J.B.L. is an inventor on issued patents describing the concept of epigenetic chromosome therapy by targeted addition of non-coding RNA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agrelo R, Souabni A, Novatchkova M, Haslinger C, Leeb M, Komnenovic V, Kishimoto H, Gresh L, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Kenner L, et al. (2009). SATB1 defines the developmental context for gene silencing by Xist in lymphoma and embryonic cells. Dev. Cell 16, 507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida M, Pintacuda G, Masui O, Koseki Y, Gdula M, Cerase A, Brown D, Mould A, Innocent C, Nakayama M, et al. (2017). PCGF3/5-PRC1 initiates Polycomb recruitment in X chromosome inactivation. Science 356, 1081–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg IM, Laven JSE, Stevens M, Jonkers I, Galjaard R-J, Gribnau J, and Hikke van Doorninck J (2009). X Chromosome Inactivation Is Initiated in Human Preimplantation Embryos. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84, 771–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A, McMillan E, Chen SI, Wallace K, and Svendsen CN (2009). A critical period in cortical interneuron neurogenesis in down syndrome revealed by human neural progenitor cells. Dev. Neurosci. 31, 497–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonney ME, Moriya H, and Amon A (2015). Aneuploid proliferation defects in yeast are not driven by copy number changes of a few dosage-sensitive genes. Genes Dev. 29, 898–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghese L, Dolezalova D, Opitz T, Haupt S, Leinhaas A, Steinfarz B, Koch P, Edenhofer F, Hampl A, and Brüstle O (2010). Inhibition of notch signaling in human embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells delays G1/S phase transition and accelerates neuronal differentiation in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 28, 955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs JA, Sun J, Shepherd J, Ovchinnikov DA, Chung T-L, Nayler SP, Kao L-P, Morrow CA, Thakar NY, Soo S-Y, et al. (2013). Integration-free induced pluripotent stem cells model genetic and neural developmental features of down syndrome etiology. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 31, 467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockdorff N (2017). Polycomb complexes in X chromosome inactivation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Hendrich BD, Rupert JL, Lafrenière RG, Xing Y, Lawrence J, and Willard HF (1992). The human XIST gene: analysis of a 17 kb inactive X-specific RNA that contains conserved repeats and is highly localized within the nucleus. Cell 71, 527–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, and Satija R (2018). Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byron M, Hall LL, and Lawrence JB (2013). A multifaceted FISH approach to study endogenous RNAs and DNAs in native nuclear and cell structures. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. Chapter 4, Unit 4.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, and Zhang Y (2002). Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298, 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S-Y, Hu Y, Chen C, Yuan F, Xu M, Li Q, Fang K-H, Chen Y, and Liu Y (2017). Enhanced derivation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cortical glutamatergic neurons by a small molecule. Sci. Rep. 7, 3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrel L, and Brown CJ (2017). When the Lyon(ized chromosome) roars: ongoing expression from an inactive X chromosome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers SM, Fasano CA, Papapetrou EP, Tomishima M, Sadelain M, and Studer L (2009). Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumeil J, Le Baccon P, Wutz A, and Heard E (2006). A novel role for Xist RNA in the formation of a repressive nuclear compartment into which genes are recruited when silenced. Genes Dev. 20, 2223–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Jiang P, Xue H, Peterson SE, Tran HT, McCann AE, Parast MM, Li S, Pleasure DE, Laurent LC, et al. (2014). Role of astroglia in Down’s syndrome revealed by patient-derived humaninduced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Commun. 5, 4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang J-C, Jiang J, Newburger PE, and Lawrence JB (2018). Trisomy silencing by XIST normalizes Down syndrome cell pathogenesis demonstrated for hematopoietic defects in vitro. Nat. Commun. 9, 5180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow JC, Hall LL, Baldry SEL, Thorogood NP, Lawrence JB, and Brown CJ (2007). Inducible XIST-dependent X-chromosome inactivation in human somatic cells is reversible. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 10104–10109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemson CM, McNeil JA, Willard HF, and Lawrence JB (1996). XIST RNA paints the inactive X chromosome at interphase: evidence for a novel RNA involved in nuclear/chromosome structure. J. Cell Biol. 132, 259–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo JA, Reisin HD, Jones M, and Bentham C (2005). Development of interlaminar astroglial processes in the cerebral cortex of control and Down’s syndrome human cases. Exp. Neurol. 193, 207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das I, Park J-M, Shin JH, Jeon SK, Lorenzi H, Linden DJ, Worley PF, and Reeves RH (2013). Hedgehog agonist therapy corrects structural and cognitive deficits in a Down syndrome mouse model. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 201ra120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Chen T, Chadwick B, Li E, and Zhang Y (2004). Ring1b-mediated H2A ubiquitination associates with inactive X chromosomes and is involved in initiation of X inactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52812–52815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Martinez J, Vela EM, Tora-Ponsioen M, Ocaña OH, Nieto MA, and Galceran J (2009). Attenuation of Notch signalling by the Down-syndrome-associated kinase DYRK1A. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1574–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DF, van Dijk R, Sluijs JA, Nair SM, Racchi M, Levelt CN, van Leeuwen FW, and Hol EM (2005). Activation of the Notch pathway in Down syndrome: cross-talk of Notch and APP. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 19, 1451–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gödecke N, Zha L, Spencer S, Behme S, Riemer P, Rehli M, Hauser H, and Wirth D (2017). Controlled re-activation of epigenetically silenced Tet promoter-driven transgene expression by targeted demethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, e147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales PK, Roberts CM, Fonte V, Jacobsen C, Stein GH, and Link CD (2018). Transcriptome analysis of genetically matched human induced pluripotent stem cells disomic or trisomic for chromosome 21. PloS One 13, e0194581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi S, Bonasoni P, Ceccarelli C, Santini D, Gualtieri F, Ciani E, and Bartesaghi R (2008). Neurogenesis impairment and increased cell death reduce total neuron number in the hippocampal region of fetuses with Down syndrome. Brain Pathol. Zurich Switz. 18, 180–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LL, Byron M, Sakai K, Carrel L, Willard HF, and Lawrence JB (2002). An ectopic human XIST gene can induce chromosome inactivation in postdifferentiation human HT-1080 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 8677–8682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydar TF, and Reeves RH (2012). Trisomy 21 and early brain development. Trends Neurosci. 35, 81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebsch N, Loskill P, Deveshwar N, Spencer CI, Judge LM, Mandegar MA, Fox CB, Mohamed TMA, Ma Z, Mathur A, et al. (2016). Miniaturized iPS-Cell-Derived Cardiac Muscles for Physiologically Relevant Drug Response Analyses. Sci. Rep. 6, 24726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Jing Y, Cost GJ, Chiang J-C, Kolpa HJ, Cotton AM, Carone DM, Carone BR, Shivak DA, Guschin DY, et al. (2013). Translating dosage compensation to trisomy 21. Nature 500, 296–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, and Salzberg SL (2019). Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Han D, Byun S-H, Kwon M, Cho JY, Pleasure SJ, and Yoon K (2018). Ttyh1 regulates embryonic neural stem cell properties by enhancing the Notch signaling pathway. EMBO Rep. 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-J, Lee H-W, Baek J-H, Cho Y-H, Kang HG, Jeong JS, Song J, Park H-S, and Chun K-H (2016). Activation of nuclear PTEN by inhibition of Notch signaling induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in gastric cancer. Oncogene 35, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi-Aoi M, Ohnuki M, Takahashi K, Okita K, Noma H, Sawamura Y, Teramoto I, Narita M, Sato Y, Ichisaka T, et al. (2013). Differentiation-defective phenotypes revealed by large-scale analyses of human pluripotent stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 20569–20574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laker C, Meyer J, Schopen A, Friel J, Heberlein C, Ostertag W, and Stocking C (1998). Host cis-mediated extinction of a retrovirus permissive for expression in embryonal stem cells during differentiation. J. Virol. 72, 339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster MA, and Knoblich JA (2014). Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2329–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen KB, Laursen H, Graem N, Samuelsen GB, Bogdanovic N, and Pakkenberg B (2008). Reduced cell number in the neocortical part of the human fetal brain in Down syndrome. Ann. Anat. Anat. Anz. Off. Organ Anat. Ges. 190, 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, and Jaenisch R (1997). Long-range cis effects of ectopic X-inactivation centres on a mouse autosome. Nature 386, 275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hibbs MA, Gard AL, Shylo NA, and Yun K (2012). Genome-wide analysis of N1ICD/RBPJ targets in vivo reveals direct transcriptional regulation of Wnt, SHH, and hippo pathway effectors by Notch1. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 30, 741–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G, and Zhang Y (2013). Genetic and epigenetic variations in iPSCs: potential causes and implications for application. Cell Stem Cell 13, 149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockstone HE, Harris LW, Swatton JE, Wayland MT, Holland AJ, and Bahn S (2007). Gene expression profiling in the adult Down syndrome brain. Genomics 90, 647–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi A, and Artavanis-Tsakonas S (2006). Notch signalling in vertebrate neural development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, and Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H-E, Yang Y-C, Chen S-M, Su H-L, Huang P-C, Tsai M-S, Wang T-H, Tseng C-P, and Hwang S-M (2013). Modeling neurogenesis impairment in Down syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells from Trisomy 21 amniotic fluid cells. Exp. Cell Res. 319, 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DK, Jang M-H, Guo JU, Kitabatake Y, Chang M-L, Pow-Anpongkul N, Flavell RA, Lu B, Ming G-L, and Song H (2009). Neuronal activity-induced Gadd45b promotes epigenetic DNA demethylation and adult neurogenesis. Science 323, 1074–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mégarbané A, Ravel A, Mircher C, Sturtz F, Grattau Y, Rethoré M-O, Delabar J-M, and Mobley WC (2009). The 50th anniversary of the discovery of trisomy 21: the past, present, and future of research and treatment of Down syndrome. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 11, 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, and Thomas P (2009). PANTHER pathway: an ontology-based pathway database coupled with data analysis tools. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 563, 123–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, Huang X, Muruganujan A, Tang H, Mills C, Kang D, and Thomas PD (2017). PANTHER version 11: expanded annotation data from Gene Ontology and Reactome pathways, and data analysis tool enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D183–D189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minks J, Baldry SE, Yang C, Cotton AM, and Brown CJ (2013). XIST-induced silencing of flanking genes is achieved by additive action of repeat a monomers in human somatic cells. Epigenetics Chromatin 6, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mito T, and Becker LE (1993). Developmental changes of S-100 protein and glial fibrillary acidic protein in the brain in Down syndrome. Exp. Neurol. 120, 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Napoles M, Mermoud JE, Wakao R, Tang YA, Endoh M, Appanah R, Nesterova TB, Silva J, Otte AP, Vidal M, et al. (2004). Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B link ubiquitylation of histone H2A to heritable gene silencing and X inactivation. Dev. Cell 7, 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechanitzky R, Dávila A, Savarese F, Fietze S, and Grosschedl R (2012). Satb1 and Satb2 are dispensable for X chromosome inactivation in mice. Dev. Cell 23, 866–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nègre N, Ghysen A, and Martinez AM (2003). Mitotic G2-arrest is required for neural cell fate determination in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 120, 253–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura A, Morizane A, Nakajima Y, Miyamoto S, and Takahashi J (2013). γ-secretase inhibitors prevent overgrowth of transplanted neural progenitors derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos-Serrano JL, Kang HJ, Tyler WA, Silbereis JC, Cheng F, Zhu Y, Pletikos M, Jankovic-Rapan L, Cramer NP, Galdzicki Z, et al. (2016). Down Syndrome Developmental Brain Transcriptome Reveals Defective Oligodendrocyte Differentiation and Myelination. Neuron 89, 1208–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyer JA, Chu A, Brar S, and Turker MS (2009). Aberrant epigenetic silencing is triggered by a transient reduction in gene expression. PloS One 4, e4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park I-H, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A, Lensch MW, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K, and Daley GQ (2008). Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell 134, 877–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payer B, and Lee JT (2008). X chromosome dosage compensation: how mammals keep the balance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42, 733–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny GD, Kay GF, Sheardown SA, Rastan S, and Brockdorff N (1996). Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature 379, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petropoulos S, Edsgärd D, Reinius B, Deng Q, Panula SP, Codeluppi S, Plaza Reyes A, Linnarsson S, Sandberg R, and Lanner F (2016). Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Lineage and X Chromosome Dynamics in Human Preimplantation Embryos. Cell 165, 1012–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plath K, Fang J, Mlynarczyk-Evans SK, Cao R, Worringer KA, Wang H, de la Cruz CC, Otte AP, Panning B, and Zhang Y (2003). Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in X inactivation. Science 300, 131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Nguyen HN, Song MM, Hadiono C, Ogden SC, Hammack C, Yao B, Hamersky GR, Jacob F, Zhong C, et al. (2016). Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell 165, 1238–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Jacob F, Song MM, Nguyen HN, Song H, and Ming G-L (2018). Generation of human brain region-specific organoids using a miniaturized spinning bioreactor. Nat. Protoc. 13, 565–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafii MS, Kleschevnikov AM, Sawa M, and Mobley WC (2019). Down syndrome. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 167, 321–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MH, Galaburda AM, and Kemper TL (1984). Down’s syndrome: is there a decreased population of neurons? Neurology 34, 909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]