Abstract

Many toxicity investigations have evaluated the potential health risks of ingested engineered nanomaterials (iENMs); however, few have addressed the potential combined effects of iENMs and other toxic compounds (e.g. pesticides) in food. To address this knowledge gap, we investigated the effects of two widely used, partly nanoscale, engineered particulate food additives, TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551), on the cytotoxicity and cellular uptake and translocation of the pesticide boscalid. Fasting food model (phosphate buffer) containing iENM (1% w/w), boscalid (10 or 150 ppm), or both, was processed using a simulated in vitro oral-gastric-small intestinal digestion system. The resulting small intestinal digesta was applied to an in vitro tri-culture small intestinal epithelium model, and effects on cell layer integrity, viability, cytotoxicity and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were assessed. Boscalid uptake and translocation was also quantified by LC/MS. Cytotoxicity and ROS production in cells exposed to combined iENM and boscalid were greater than in cells exposed to either iENM or boscalid alone. More importantly, translocation of boscalid across the tri-culture cellular layer was increased by 20% and 30% in the presence of TiO2 and SiO2, respectively. One possible mechanism for this increase is diminished epithelial cell health, as indicated by the elevated oxidative stress and cytotoxicity observed in co-exposed cells. In addition, analysis of boscalid in digesta supernatants revealed 16% and 30% more boscalid in supernatants from samples containing TiO2 and SiO2, respectively, suggesting that displacement of boscalid from flocculated digestive proteins by iENMs may also contribute to the increased translocation.

Keywords: Ingested Engineered Nanomaterials, Titanium Dioxide, E171, Silica, E551, Boscalid, Toxicity

Introduction

Engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) have been investigated by researchers and widely used in the food industry to improve the taste, nutritional value, and appearance of food products, to enhance food quality, and to extend shelf-life 1–6. It has been reported that dietary intake of ENMs may be as high as 112 mg/person/day 7. However, regulations pertaining to ENMs in food products are still in the early stages of development due to insufficient health data 8,9. Before regulations can be successfully implemented, a more comprehensive understanding of the oral toxicity of ENMs is necessary.

Emerging evidence links ingested ENMs (iENMs) to a variety of toxicological outcomes 10–12. For example, food grade titanium dioxide (TiO2), known as E171, is a widely used food additive for whitening in food products such as chewing gums, icings and dairy products 13,14. Oral exposure to TiO2 in the US has been estimated to be 1–2 mg/kg bw/day for children under the age of 10 years, and 0.2–0.7 mg TiO2/kg bw/day for adults 14. It has also been shown that roughly 36% of particles in E171 have dimensions in the nanoscale (<100 nm), which has led to health concerns from consumers, scientists, and policy makers 14. Furthermore, it has been reported that oral exposure of TiO2 NPs in mice induced adverse health effects, such as genotoxicity15, inflammation, oxidative stress 16,17, and damage to the liver 12,18 and kidneys 19.

Food grade silica (SiO2), designated as E551, which also has a substantial nanosized component, is commonly used as an anticaking agent in comminuted and powdered foods 20. Oral exposure to nano-SiO2 has been estimated at 1.8 mg/kg bw/day 21. In general, nanosized SiO2 is believed to be less toxic than other inorganic nanomaterials in food 22. Nevertheless, adverse effects of ingested nanosized SiO2 have been reported. For example, a 10-week period of dietary exposure with nano-SiO2 in mice led to liver toxicity, as evidenced by an increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level in blood, and a fatty liver pattern 23.

Although such findings provide important information about the potential toxicity of iENMs acting alone, they do not address the potential impact of iENMs on the absorption and toxicity of other hazardous substances (such as pesticides and heavy metals) that may also be present in food, and the consequent toxicity. In the food matrix, and along the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), iENMs can interact with these other hazardous substances, with food and digestive molecules 24, and with cells lining the GIT, to alter or exacerbate the responses to these substances in target organisms 9.

There are a limited number of studies in the literature that examined the combined effects of ENMs and toxicants in the environment. Several reports have noted enhanced toxic effects of heavy metals in the presence of ENMs 25–29. Others have reported significant accumulations of toxicants on nanoparticle surfaces 25,26,28,29. These accumulated toxic substances can play important roles in dose-response relationships, because organisms are stimulated not only by the ENMs, but also by the accumulated toxic species. For example, it has recently been reported that co-exposure to TiO2 NPs and bisphenol A (BPA) caused a shift in the intestinal microbial community in a synergistic manner that was positively correlated with adverse health effects in zebrafish 27. It has also been reported that adsorption of environmental toxins onto the surface of nanomaterials can produce synergistic toxicity and increase toxin levels in animal organs. For example, Al2O3 NPs adsorbed As and produced synergistic toxicity in Ceriodaphnia dubia 25,28. SiO2 NPs absorbed CdCl2, producing synergistic toxicity, and increased Cd levels in mouse livers 30.

Studies on the combined toxic effects of co-ingested iENMs and pesticides are limited. For example, TiO2 NPs adsorbed dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (p,p’-DDT), and produced synergistic genotoxicity in human hepatocytes 29. Such studies of the health effects of co-exposures to iENMs and pesticides are complicated by uncertainties resulting from the complex interactions of iENMs and pesticides with the food matrix and GIT fluids 31–34. Thus, in order to investigate these effects under relevant conditions, it is necessary to incorporate iENMs and pesticides into realistic food models, subject the resulting mixtures to the physiological and biochemical conditions of digestion, and apply the resulting digested product to a physiologically relevant cellular model (i.e., small intestinal epithelium) 35.

This study examines the combined cytotoxic effects of the pesticide boscalid and two widely used engineered food additives, TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551), which contain considerable amounts of nanosized particles, and the impact of these materials on the uptake and translocation of boscalid in an in vitro tri-culture small intestinal epithelium monolayer. Boscalid is a systemic fungicide that is effective against a wide range of fungal pathogens, and has been broadly used on a variety of crops, including root and bulb vegetables, leafy and fruiting vegetables, vine fruits, and tree nuts 36,37. The residue level of boscalid in grapes, for example, was found to be 4.23 mg/kg. It was further shown that a significant portion of this residue was transferred from grapes to wine products 38.

Although E171 and E551 are often referred to as ENMs, and we will henceforth refer to them as iENMs here, it should be noted that they are in fact engineered fine particulate materials with size distributions that only partially fall within the contemporary definition of nanoscale (i.e., having one or more dimension of 100 nm or less). E551 has been found to contain particles ranging from 30–200 nm 21, and the nanoscale fraction of E171 has been estimated to be roughly 36% 14. However, the definition of “nanomaterial” is an evolving one, and the 100 nm cutoff is somewhat arbitrary and fluid. Indeed, it has recently been suggested that nanomaterials might be defined in terms of their behavior, as those having “chemical, physical and/or electrical properties that change as a function of their size and shape”, rather than by specific dimensional constraints 39. Finally, it should be noted that all materials designated E551 or E171 are not necessarily identical, and samples with the same designation from two different manufacturers may have significantly different size distributions.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The pesticide Boscalid, TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551) and were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA), Pronto Foods Co. (Chicago, IL, USA) and Spectrum Chemical MFG. Corp. (New Brunswick, NJ, USA), respectively.

Allowable tolerances have been established in Title 40 of the Code of the Federal Regulations (40 CFR §180.589) for residual boscalid in/on numerous plant commodities, ranging from 0.05 ppm in/on peanuts and tuberous and corm vegetables (subgroup 1C) to 70 ppm in/on leafy greens (subgroup 4–16A) and up to 150 ppm in/on herbs (subgroup 19A). Based on the regulations for tolerances in fruit and vegetables, the starting (in the fasting food model) concentrations of boscalid chosen for this study were 10 ppm and 150 ppm. Referring to Title 21 of Code of the Federal Regulations (21 CFR §73.575 and §172.480), the allowable maximum concentrations of the color additive TiO2 (E171), and the anticaking agent SiO2 (E551), are 1% and 2%, respectively, by weight, of the food. Therefore, the starting (in the fasting food model) concentrations of iENMs (food grade TiO2 and SiO2) chosen for this study were both 1% w/w.

Pristine ENM characterization

Pristine ENM physico-chemical and morphological characterization was performed as previously described 35. In summary, particle size and morphology were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL 2100, Japanese Electron Optics Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan). Specific surface area (SSA) and dBET was measured by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method (NOVA TOUCH LX4, Quantachrome instruments, Boynton Beach, FL). The BET equivalent primary particle diameter dBET was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

The crystal structure of particles was characterized by X-ray powder diffraction spectroscopy (D8 VENTURE, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). The surface functional groups of particles were determined using Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Spectrum One ATR, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Dispersion and colloidal characterization of ENMs with and without boscalid in water and small intestinal phase digesta:

Dispersions were prepared as previously described 40,58,59. Briefly, the critical delivered sonication energy (DSEcr), which is the minimum required energy per dispersion volume (joules/mL) to achieve the smallest possible agglomerates, was determined for each particle type by incremental sonication and size characterization. Suspensions of the particles in deionized (DI) water were dispersed using a sonicator that was first calibrated to determine its energy delivery rate (i.e., J/s). The mean hydrodynamic diameter of the suspension over time was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and plotted to determine the minimum sonication time, and thus energy, required to achieve the smallest possible diameter agglomerates.

TiO2 and SiO2 particle dispersions with and without boscalid in water were then analyzed by DLS to determine mean hydrodynamic diameter (dH), polydispersity index (PdI), zeta-potential (ζ), and conductivity (σ), using a Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, Ltd., Worcestershire, UK). All measurements were performed in triplicate, at 25 °C, using disposable optical polystyrene micro-cuvettes. In addition, a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, Malvern Instruments, Ltd) was used to obtain the surface-weighted mean diameters (D[3,2]), volume-weighted mean diameters (D[4,3]), and volume-weighted size distributions of particles in small intestinal phase digesta from the simulated GIT digestion (described below).

In vitro simulated digestions:

Phosphate buffer (5 mM) at pH 7.0 was used as a fasting food model (FFM) in the simulated digestions. FFM alone (control) or FFM containing either iENMs suspension, boscalid, or a combination of iENM and boscalid, were used as initial food inputs for simulated digestion. Nine samples were included in total, as follows: (1) FFM control (5 mM phosphate buffer alone); (2) FFM with TiO2 (1% w/w); (3) FFM with SiO2 (1% w/w); (4) FFM with boscalid at concentration of 10 ppm; (5) FFM with TiO2 (1% w/w) and boscalid at concentration of 10 ppm; (6) FFM with SiO2 (1% w/w) and boscalid at concentration of 10 ppm boscalid; (7) FFM with boscalid at concentration of 150 ppm; (8) FFM with TiO2 (1% w/w) and boscalid at concentration of 150 ppm; (9) FFM with SiO2 (1% w/w) and boscalid at concentration of 150 ppm boscalid.

In vitro simulated digestion of the above samples was performed using a 3-phase (oral, gastric, small intestinal) simulator (Figure 1) as previously described 35. Briefly, in the oral phase, input food samples were brought to 37 °C in a water bath, mixed with pre-warmed (37 °C) simulated saliva fluid, and incubated at 37 °C for 10 seconds. The resulting oral phase digestas were then combined with simulated gastric fluid and incubated for two hours, at 37 °C, on an orbital shaker at 100 rpm, to complete the stomach phase. In the small intestinal phase, stomach digestas were combined with additional salts, bile extract and lipase to simulate intestinal fluid, and incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours, while maintaining a constant pH of 7.0, using a pH stat titration device (TitroLine® 7000, SI Analytics, GmbH, Germany).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the study design.

The initial concentrations of iENMs and boscalid were diluted by a factor of 1/48 in total with digestive fluids in the oral (1/2), gastric (1/2) and small intestinal (1/3) phases, and with cell culture medium (1/4) before being applied to cells.

Tri-culture small intestinal epithelium cell model and treatments

The complete hybrid tri-culture epithelium, illustrated in Figure 1 and the integrated methodology which includes the dynamic GIT simulated digestions, have previously been described and characterized in detail by the authors in a previous publication 35. In summary, Caco-2 cells and HT29-MTX cells were first co-cultured for 2 weeks, during which time the Caco-2 cells differentiate to resemble small intestinal enterocytes, and HT29-MTX, similar to intestinal goblet cells, produced and secreted copious mucus. Raji B cells were then introduced to the basolateral compartment of transwell system to stimulate a portion of the matured Caco-2 cells to differentiate acquire an M-cell-like phenotype. Fluorescence immunostaining of mucin (MUC2) and the M-cell marker glycoprotein-2 (GP2) and confocal imaging revealed a continuous epithelial layer with scattered mucin-rich cells (HT29-MTX cells) in nests of enterocytes (Figure S3), resembling an in vivo small intestinal epithelium 35. This tri-culture model thus represents a reasonably realistic hybrid model of the complete small intestinal epithelium suitable for prediction of small intestinal toxicity and biokinetics in humans.

Caco-2, HT29-MTX, and Raji B cells were obtained from Sigma, Inc. Briefly, Caco-2 and HT29-MTX cells were grown in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mM HEPES buffer, 100 IU/mL Penicillin, 100 μg/mL Streptomycin and non-essential amino acids (1/100 dilution of 100 X solution, ThermoFisher). Raji B cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 100 IU/mL Penicillin and 100 μg/mL Streptomycin. For transwell inserts, Caco-2 and HT29-MTX cells were trypsinized and resuspended in DMEM media at 3 × 105 cells/mL, and combined in a ratio of 3:1 (Caco-2:HT29-MTX). A 1.5-mL portion of the cell mixture was seeded in the apical chamber, and 2.5 mL of complete DMEM media was added to the basolateral compartment of a 6 well transwell plate (Corning). Media was changed after four days, and subsequently every other day, until day 15. On day 15 and 16, the media in the basolateral compartment was replaced with 2.5 mL of a suspension of Raji B cells at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL in 1:1 DMEM: RPMI complete media. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured using an EVOM2 Epithelial Volt/Ohm Meter with a Chopstick Electrode Set (World Precision Instruments). Cytotoxicity (LDH release), and uptake and translocation studies using tri-cultures on transwells were initiated on day 17.

Cell viability (tetrazolium salt reduction) and oxidative stress (ROS production) studies require closed-bottom adherent cell cultures in 96-well plates suitable for plate reader fluorescence measurements. For these studies, Caco-2/HT29-MTX co-cultures were prepared in 96-well plates. Raji B cells were not used in this format, since they are suspension feeder cells (added to the transwell basolateral compartments to promote M-cell differentiation of some apical Caco-2 cells), and not part of the epithelium, but could adhere to mucus, or become incorporated in the epithelial layer, if applied apically in closed 96-well plates. To prepare these co-cultures, Caco-2 and HT29-MTX cells at a 3:1 ratio were seeded at a total 3 × 104 cells/well (100 μL of cell mixture) in black-walled, clear optical bottom plates (BD Biosciences). Media was changed after four days, and subsequently every other day, until day 17. Cell viability and oxidative stress experiments performed with the 96-well plate co-cultures were initiated on day 17.

The final small intestinal phase digesta from simulated digestions described above (Figure 1) were combined with DMEM media at a ratio of 1:3, and the mixtures were applied to the cells (1.5 mL to the apical compartment for transwell inserts, 200 μL per well for 96-well plates). At the end of treatments, apical fluid from transwells was collected for LDH analysis (see below for details). For boscalid translocation studies (see below for details), basolateral and apical fluids were collected, along with two 1.5 mL PBS washes for each compartment. To collect cells for analysis, 100 μL of RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Boston BioProducts, Boston, MA, USA) was added to the apical compartment, a cell scraper was used to remove cells, and cells were transferred into a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. This process was repeated two additional times to ensure collection of all remaining cells. Protein content in collected cells was quantified using Pierce™ BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All biological samples were stored at −80 ℃ until analysis.

Cytotoxicity, cell viability, and ROS production analysis:

Supernatants from transwells were collected after 24h exposures for LDH analysis, which was performed using the Pierce LDH assay kit (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Untreated control wells were used to measure spontaneous LDH release. For maximum LDH release control wells, 150 μL of apical fluid was removed and replaced with 150 μL 10X lysis buffer 45 minutes prior to the end of incubation. The provided substrate was dissolved in 11.4 mL of ultrapure water and added to 0.6 mL assay buffer to prepare the reaction mixture. Apical fluid in each well was pipetted to the mix and 150 μL was transferred to a 1.5 mL tube. Tubes were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min., and 50 μL of the supernatant from each tube was dispensed in triplicate wells in a fresh 96-well plate. Fifty μL of reaction mixture was added and mixed by tapping the plate. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes or less (to provide maximum difference in color between samples by visual inspection), and 50 mL stop solution was added and mixed by tapping. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm (A490) and 680 nm (A680). To calculate LDH activity, A680 values were subtracted from measured A490 values to correct for instrument background. To correct for digesta background, LDH activities from no-cell controls were subtracted from test well LDH activities. Percent cytotoxicity was calculated by subtracting spontaneous LDH release values from treatment values, dividing by total LDH activity (Maximum LDH activity – Spontaneous LDH activity), and multiplying by 100.

ROS analysis was performed after 6 h exposures in 96-well co-cultures. Production of ROS (oxidative stress) was assessed using the CellROX® green reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells treated with 100 μM menadione for 1 h at 37°C were used as a positive control. Briefly, a 5 mM working solution of reagent was prepared from 20 mM stock by diluting in DMEM media without FBS. Media was removed from test wells and replaced with 100 μL of working solution, and plates were incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Wells were then washed 3 times with 200 μL PBS, and fluorescence was measured at 480 nm (excitation)/520 nm (emission).

PrestoBlue metabolic activity (cell viability) assay was performed after 24 h exposure using cells in 96-well plate co-cultures. PrestoBlue™ cell viability reagent (ThermoFisher) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, wells were washed 3 times with 200 μL of PBS, and 100 μL of 10% PrestoBlue reagent was added to each well. Plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes, and fluorescence was measured at 560 nm (excitation)/590 nm (emission).

Quantification of boscalid bioavailability using the tri-culture epithelial model:

Small intestinal digestas with boscalid, with and without TiO2 or SiO2, fluid collected from apical and basolateral transwell compartments of triculture cellular model, and cell pellets from translocation experiments, were analyzed to quantify boscalid and select metabolites by LC/MS. Samples were extracted by a QuEChERS method based on De La Torre et al. with some modifications 41. Briefly, 1 g (wet weight) of each sample was transferred into a 15 mL centrifuge tube, and triphenyl phosphate was spiked as internal standard. Samples weighting less than 1 g were adjusted to the desired weight with Milli-Q water. One gram of acetonitrile was added as the extraction solvent followed by the addition of 0.4 g of magnesium sulfate and 0.1 g of sodium acetate. Each replicate was vortexed and then placed on a wrist-action shaker for 15 min. The tubes were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Finally, 1 mL of each replicate extractant was filtered and transferred to chromatography vials for storage at −4 °C until analysis.

Samples were analyzed using a Thermo Exactive High Resolution Mass Spectrometer (ThermoFisher) coupled to an Agilent 1200 series Liquid Chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The LC was operated in the gradient mode using a Thermo Hypersil GOLD aQ 100 mm x 2.1 mm column (ThermoFisher). Mobile phase A was water with 1% formic acid and mobile phase B was acetonitrile with 1% formic acid. The gradient was held at 99% A for 1 minute, increased to 5 % A over the next 8 minutes, held at 5% A for another 5 minutes, and then returned to 99% A for re-equilibration before the next sample. The injection volume was 1.5 μL. The standards ranged from 25 ppb to 1000 ppb and the lower limit of detection was 5 ppb. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive electrospray mode using 3 scans: a full scan at resolution of 50,000 and two all ion fragmentation scans at resolution 25,000 (one with HCD energy at 15, and one at 45).

Characterization of binding affinities of boscalid to TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551) in water

Nano- ITC (isothermal titration calorimetry) (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) was used to measure the binding thermodynamics between boscalid and TiO2/SiO2. All chemicals and particles were dissolved or suspended in 50% ethanol to minimize the heat of dilution. All mixtures were degassed prior to titrations. Titrations were performed by injecting boscalid solution (500 μM) into TiO2 or SiO2 suspensions in 25 successive 2 μL aliquots. TiO2 and SiO2 concentrations were varied to obtain the correct stoichiometry. The time interval between successive injections was fixed at 300 seconds to allow sufficient equilibration time. Stirring was set at 300 rpm to ensure thorough mixing. Data analysis was performed using NanoAnalyze software (TA Instruments), after subtracting the heat of dilution of boscalid. The thermogram was integrated peak by peak and normalized against moles of injectant to obtain a plot of enthalpy change per mole of boscalid against the mole ratio of boscalid-TiO2/SiO2.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis of data was performed using Prism 7.03 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Results of TEER, cell viability, cytotoxicity and ROS generation studies were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Results of boscalid translocation and cellular uptake studies were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

Results

Physicochemical properties of pristine ENM powders

Detailed physicochemical characterization of the TiO2 (E171) used in this study was reported previously 42. In brief, XRD patterns revealed an anatase phase, and the mean size of TiO2 particles as measured by TEM was 113.4 ± 37.2 nm. Of the measured particles, ~40% presented a maximum lateral size <100 nm, in good agreement with what has been reported elsewhere for this food additive 14.

For SiO2 (E551) powders, the morphology characterized by TEM is shown in Figure 2A. Based on XRD data, SiO2 particles had an amorphous morphology (Figure 2B). FTIR revealed typical Si – O – Si stretching and Si – O bending features (Figure 2C). The specific surface area (SSA) was 190.4 m2/g and mean diameter, as measured by BET, was 12.18 nm, which is in good agreement with what has been reported elsewhere for this food additive 43.

Figure 2. Characterization of pristine SiO2 (E551) powder.

(A) SEM image of SiO2 (E551) particles. (B) X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of E551. (C) Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis of E551.

Colloidal characterization of TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551) with and without boscalid in water and in small intestinal phase digesta

TiO2 particles spontaneously dispersed in water without the need for sonication (DSEcr = 0, Figure 3A), and had a mean hydrodynamic diameter (dH) of 0.37 μm ± 0.00 with a polydispersity index (PdI) of 0.18 ± 0.00 (Figure 3B). The DSEcr of SiO2 in water was 113 J mL−1 (Figure 3C). Upon delivery of this amount of energy per dispersion volume, the dH of SiO2 particles was 0.20 ± 0.00 μm with a PdI of 0.15 ± 0.01 (Figure 3D), indicating a very narrow size distribution, typical for pyrogenic amorphous silica. When dispersed in water, the number-weighted hydrodynamic size distribution of TiO2 and SiO2 suggested that ~22% and ~30% of particles or agglomerates measured <100 nm diameter, respectively (Figure 3B and 3D). Finally, the large negative ζ-potential of both types of particles in water in combination with their small size suggest very stable colloidal suspensions.

Figure 3. Dispersion preparation and hydrodynamic size distributions of TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551) in deionized water.

(A) Mean hydrodynamic diameter (dH) and polydispersity index (PdI) of TiO2 (E171) particles in deionized water as a function of delivered sonication energy. It can be seen that for this material, sonication does not decrease agglomerate size, and thus DSEcr for E171 is 0. (B) Scattered light intensity (solid line) and number-weighted (dashed line) hydrodynamic diameter distributions TiO2 (E171) in water. (C) Mean hydrodynamic diameter (dH) and polydispersity index (PdI) of SiO2 (E551) particles in deionized water as a function of delivered sonication energy. Mean dH decreased with additional sonication energy sonication up to 113 J mL−1 (DSEcr) beyond which it did not decrease further. (D) Scattered light intensity (solid line) and number-weighted (dashed line) hydrodynamic diameter distributions for SiO2 (E551).

The colloidal properties of TiO2 and SiO2, with and without boscalid, in water are summarized in Table 1. The addition of boscalid did not alter the colloidal properties (dH or PdI) of TiO2 in water. Conversely, addition of boscalid to SiO2 suspensions increased dH from 0.20 ± 0.00 μm to 0.46 ± 0.01 μm, increased PdI from 0.15 ± 0.01 to 0.37 ± 0.01, and slightly reduced the ζ-potential from −18.1 ± 2.1 mV to −24.6 ± 0.1 mV.

Table 1.

Colloidal characterization of ENMs with/without boscalid in deionized water

| Sample | dH (μm) | PdI | ζ (mV) | σ (mS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 0.37 ± 0.00 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | −30.6 ± 0.2 | 0.009 ± 0.001 |

| Boscalid +TiO2 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | −33.1 ± 1.1 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| SiO2 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | −18.1 ± 2.1 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

| Boscalid + SiO2 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | −24.6 ± 0.1 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

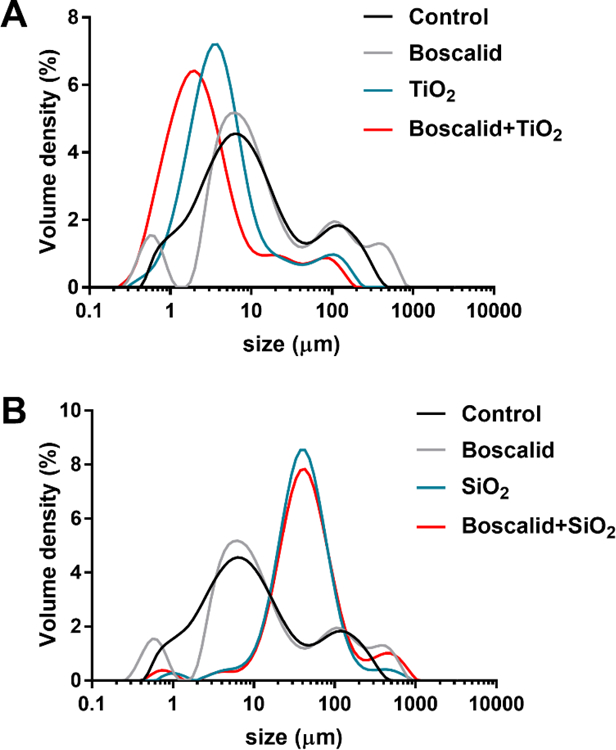

The average diameters and diameter distribution of particles in digesta from the small intestinal phase are shown in Table 2 and Figure 4, respectively. The surface area moment mean D[3,2], also known as the Sauter mean, is a surface area-weighted average. The volume area moment mean D[4,3], also known as the DeBroukere mean, is the mean diameter over volume. D[3,2] and D[4,3] can be used to describe the entire particle population of small intestinal digestas. Dv10, Dv50, and Dv90 values represent the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile of the cumulative particle volume of a sample.

Table 2.

Colloidal characterization of ENMs with/without boscalid in small intestinal phase digesta.

| Sample | D[3,2] (μm) | D[4,3] (μm) | Dv10 (μm) | Dv50 (μm) | Dv90 (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (PB) | 3.94 ± 0.13 | 32.6 ± 2.5 | 1.53 ± 0.02 | 8.08 ± 0.22 | 112 ± 8 |

| Boscalid | 3.75 ± 0.17 | 29.3 ± 2.3 | 2.20 ± 0.02 | 6.97 ± 0.0.13 | 84 ± 7 |

| TiO2 | 2.77 ± 0.08 | 11.1 ± 1.8 | 1.32 ± 0.02 | 3.76 ± 0.12 | 21 ± 5 |

| Boscalid +TiO2 | 1.64 ± 0.03 | 8.3 ± 0.7 | 0.74 ± 0.01 | 2.21 ± 0.59 | 17 ± 3 |

| SiO2 | 15.90 ± 0.36 | 58.9 ± 1.2 | 14.77 ± 0.05 | 39.83 ± 0.17 | 104 ± 2 |

| Boscalid + SiO2 | 17.10 ± 0.43 | 65.4 ± 10.8 | 14.80 ± 0.16 | 41.23 ± 1.18 | 122 ± 21 |

D[3,2]: surface area moment mean; D[4,3]: volume moment mean; Dv10, Dv50, Dv90: volume-weighted percentiles (10, 50 and 90%, respectively)

Figure 4. Size distributions of particles in small intestinal phase digesta.

(A) Volume density % of particle diameter distributions for small intestinal phase digesta of the fasting food model control (PB), boscalid, TiO2, and boscalid+TiO2. (B) Volume density (%) of particle diameter distributions for small intestinal phase digesta of fasting food model control (PB), boscalid, SiO2, and boscalid+SiO2.

In small intestinal digesta from FFM control (phosphate buffer alone, without iENM or boscalid), D[3,2] was 3.94 μm, which was similar to sizes observed for digestas from FFM containing boscalid (at concentration of 150 ppm) (D[3,2] = 3.75 μm). Likewise, their size distribution curves were overlapping and nearly identical (Figure 4). In digesta from the FFM containing TiO2 (1% w/w), D[3,2] was slightly smaller (2.77 μm without and 1.64 μm with boscalid) than those in digestas from the FFM control (Table 2). Likewise, the size distribution curves of particles in digesta containing TiO2 (without and with boscalid) were shifted to the left, toward smaller sizes, compared with the FFM control (Figure 4A). In contrast, digesta from FFM containing SiO2 (1% w/w), D[3,2] was considerably larger (15.9 μm without, and 17.1 μm with boscalid) than those in digesta from the FFM control (Table 2). Likewise, the size distribution curves of particles in digesta containing SiO2 (without and with boscalid) were shifted to the right, toward larger sizes, compared with the FFM control (Figure 4B). Consistent results were observed for D[4,3], Dv10, Dv50, and Dv90 values.

The presence of large particles in small intestinal digesta without iENMs is most likely due to flocculated digestive proteins. Mucin, amylase and pepsin added in the oral and gastric phases are subjected to extremely low pH (~1.5) denaturing conditions in the gastric phase, which may facilitate flocculation and precipitation of these proteins before arrival in the small intestine. Pancreatic enzymes added to the small intestinal phase may complex with the denatured proteins from the gastric phase to further increase flocculation and particle size. Although the total protein concentration in the small intestinal phase (~5.5 mg mL−1) is well below the solubility range for globular proteins such as these, the gastric and intestinal phase digesta are markedly turbid and opaque, and centrifugation of such digesta produce distinct solid pellets and a clear supernatant, consistent with protein denaturation, precipitation and flocculation.

Singh et al. reported that whereas TiO2 did not dissolve during simulated digestion, up to 65% of SiO2 dissolved in the gastric phase, and subsequently precipitated into much larger agglomerates when transferred to the small intestinal phase 10. The particularly large aggregates observed in SiO2 digesta in this study may in part result from such dissolution and precipitation of SiO2, most likely associated with flocculated digestive proteins.

In vitro toxicity of boscalid with and without TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551) iENMs

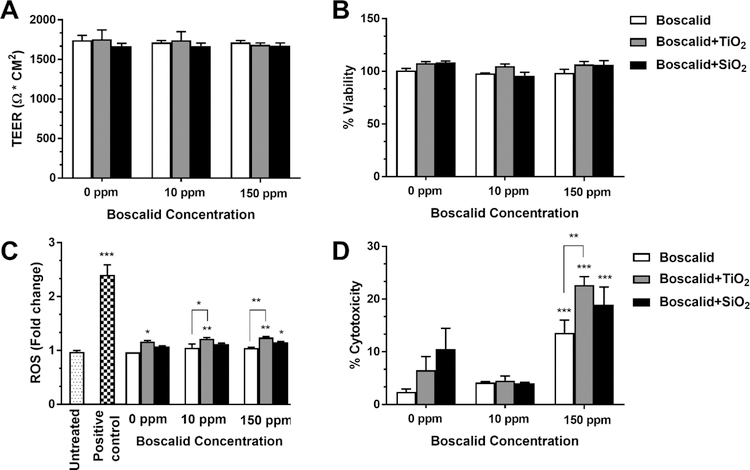

In vitro cellular toxicity was evaluated for small intestinal digesta from the FFM control (phosphate buffer), iENMs only (TiO2 and SiO2 at 1% w/w in FFM), boscalid alone (at 10 and 150 ppm in FFM), and digesta from combinations of boscalid at each concentrations with each iENMs in FFM as described in the methods section. Results of toxicity studies are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5. In vitro toxicity of boscalid with and without ENMs.

(A) TEER measurements after 24 h exposures to digesta from simulated digestion. (B) Cell viability following 24 h exposure to digesta from simulated digestion. (C) ROS generation (fold change from control) following 6 h exposure to digesta from simulated digestion. (D) Cytotoxicity (LDH assay) following 24 h exposure to digesta from simulated digestion. Error bars represent ±SD, *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001.

As shown in Figure 5A and 5B, compared with digesta from the FFM control, none of the digesta containing boscalid, iENMs, or a combination of boscalid and iENMs, caused significant changes in either transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) or cell viability at the doses used in this study, indicating that cell layer integrity and tight junctions were not impaired, and that cells remained metabolically active.

Figure 5C shows the fold change of ROS production after 6 hours of exposure relative to 0 ppm boscalid (small intestinal digesta of FFM). The difference in ROS production between 0 ppm boscalid and untreated cells (cells cultured in fresh medium) was negligible. The positive control (100 μM menadione) induced a 2.4 fold change in ROS production. Compared with digesta from the FFM control (phosphate buffer alone), digesta from the FFM containing iENMs alone and boscalid alone caused slight increases in ROS production. Specifically, a 1.20 (p<0.05) and a 1.11 (p>0.05) fold increase was found for TiO2 and SiO2, respectively, and a 1.08 (p>0.05) fold increase was found for boscalid at both concentrations (10 ppm and 150 ppm). Compared with digesta from FFM control, digestas from combinations of boscalid and iENM in FFM caused a significant increase in ROS production. The combinations of TiO2 and boscalid at 10 and 150 ppm resulted in a 1.26 (p<0.01) and 1.28 (p<0.01) fold increase, respectively. Combinations of SiO2 and boscalid at 10 and 150 ppm caused a 1.16 (p>0.01) and 1.19 (p<0.05) fold increase, respectively. More importantly, the increases in ROS production from combinations of boscalid and TiO2 were significantly different from the increases caused by boscalid alone (p<0.05 for boscalid at concentration of 10 ppm and p<0.01 for 150 ppm). From these data, it can be seen that ROS increases for FFM containing combination of boscalid and iENM were greater than the ROS increases for the corresponding model containing separate boscalid and iENM.

Figure 5D shows cytotoxicity measured by LDH assay after 24 hours of exposure to digestas. Digestas from FFM with iENMs alone (1% w/w TiO2 or SiO2), and from FFM with boscalid at 10 ppm, with or without iENMs, caused only slight (<10%) cytotoxicity, which was not statistically greater than cytotoxicity from FFM control digestas (2.4%). Digestas from FFM containing 150 ppm boscalid alone caused only slightly higher, 13.6% cytotoxicity, though significantly more than that from FFM control digestas (p<0.001). By contrast, digestas from FFM containing 150 ppm boscalid plus iENMs caused substantial cytotoxicity. Digestas from FFM with 150 ppm boscalid plus 1% w/w TiO2 caused 22.6% cytotoxicity, and those from 150 ppm boscalid plus 1% w/w SiO2 caused 18.9% cytotoxicity, both values significantly different from cytotoxicity of the FFM control (p<0.001). Cytotoxicity caused by digesta from FFM with 150 ppm boscalid plus TiO2 was also significantly greater (p<0.01) than that caused by digesta from FFM with 150 ppm boscalid alone. These results suggest that, as with ROS production, cytotoxicity for combined iENMs and boscalid were greater than the corresponding separate boscalid and iENM treatments.

Cellular uptake and translocation of boscalid with and without iENMs

A transwell tri-culture model of small intestinal epithelium, including Caco-2, HT29-MTX and Raji B cells was employed to assess cellular uptake and translocation of boscalid through an intestinal epithelial cell monolayer. The results of these studies are shown in Figure 6. At the lower initial boscalid concentration of 10 ppm in FFM, small but statistically insignificant increases of 6% and 9% in cellular uptake of boscalid from digestas were seen in the presence of TiO2 and SiO2, respectively (Figure 6A). Small, statistically insignificant increases of 2% and 10% in boscalid translocation were also observed in the presence of TiO2 and SiO2, respectively (Figure 6B). More substantial increases in uptake and translocation of boscalid were seen in the presence of iENMs at 150 ppm initial boscalid concentration (Figure 6C and 6D). Moderate, 9% and 20%, but statistically insignificant increases in cellular uptake of boscalid were observed in the presence of TiO2 and SiO2, respectively (Figure 6C). More notably, 20% and 30%, statistically significant (p<0.01) increases in translocation of boscalid were observed in the presence of TiO2 and SiO2, respectively (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Cellular uptake and translocation of boscalid with and without ENMs.

(A) Cellular boscalid following 24 h exposure to digesta from simulated digestion with starting (in the fasting food model) boscalid concentration of 10 ppm. (B) Boscalid concentration in the basolateral compartment following 24 h exposure to digesta from simulated digestion with starting boscalid concentration of 10 ppm. (C) Cellular boscalid following 24 h exposures to digesta from simulated digestion with starting boscalid concentration of 150 ppm. (D) Boscalid concentration in the basolateral compartment following 24 h exposures to digesta from simulated digestion with starting boscalid concentration of 150 ppm. Error bars represent ±SD, *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001.

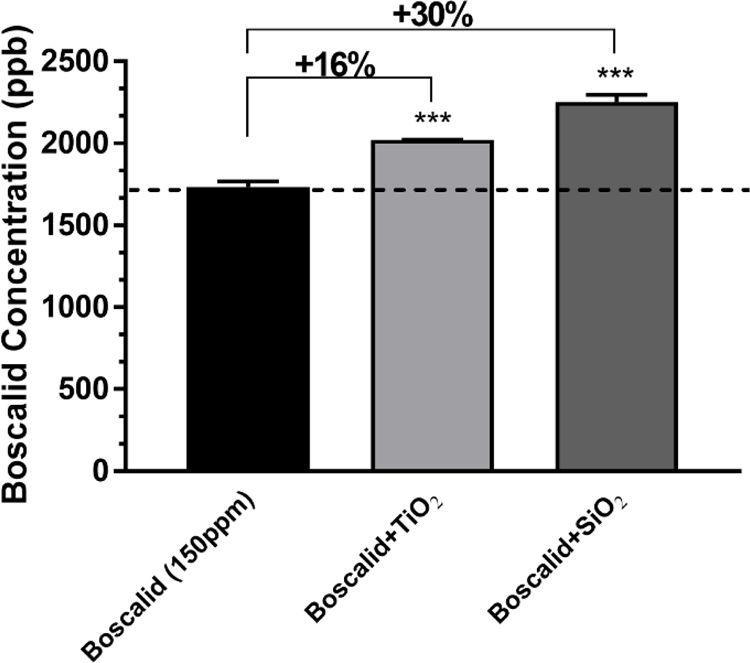

Boscalid concentrations in small intestinal phase digesta supernatant with and without iENMs:

Digesta samples were centrifuged and filtered to quantify the boscalid in liquid phase as described in the methods section. The results for boscalid at 150 ppm initial concentration in FFM, with and without iENMs, are shown in Figure 7. Concentrations of free boscalid were 16% and 30% greater (p<0.001) in the presence of TiO2 and SiO2, respectively, than in digestas without iENMs. These data suggest that the presence of iENMs increased the amount of boscalid not bound to solids, possibly by displacing boscalid from digestive enzymes and other proteins that become part of the particulate or flocculated solids in the final digesta.

Figure 7. Boscalid concentrations in the liquid phase of digesta.

Error bars represent ±SD, *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001.

Binding affinities of boscalid to iENMs TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551) in water

Additional information on the nature of the molecular interactions between boscalid and iENMs in water was obtained by measuring enthalpy changes using Nano-ITC (isothermal titration calorimetry). Nano-ITC did not produce meaningful results for boscalid interaction with TiO2 (E171). This could be due to low affinity of boscalid to TiO2 (Figure S1). Conversely, nano-ITC revealed high binding affinity for boscalid to SiO2 (E551). Two inflection points were observed in the titration of boscalid into SiO2 suspension, suggesting a two-stage interaction (Figure S2). The integrated peaks of the thermogram were fitted using the multiple sites model. The resulting thermodynamic parameters are shown in Table S1. The two inflection points were correlated to stoichiometric values n1 and n2, which had mole ratios of approximately 0.5 and 3, respectively. These results suggest that in the first stage of interaction, one boscalid molecule was bound to two binding sites on SiO2, and in the second stage of interaction, three boscalid molecules were bound to one binding site on SiO2. Based on the recorded values presented in Table S1, Kd1 (Kd of stage one interaction) was slightly lower than Kd2 (Kd of stage two interaction), implying that the first stage of interaction had a higher affinity.

Discussion

The increasing use of engineered nanomaterials in food and the unavoidable co-ingestion of other potential xenobiotics (such as pesticide residuals) raises concerns about increased health risks. This important knowledge gap in nanotoxicology research makes it difficult for risk assessors to accurately assess health implications of iENMs. In this study, we hypothesized that nanomaterials at low, non-cytotoxic doses may modulate the bioavailability and toxicity of a co-ingested pesticide. In order to bring physiological relevance to this in vitro cellular study, a GIT simulator was used to mimic oral, gastric and small intestinal digestion and the interactions of iENMs and pesticides with food and digestive enzymes. The small intestinal phase digesta was applied to a tri-culture small intestinal epithelial cell model to assess the toxicity and bioavailability of the pesticide (boscalid) with and without iENMs (food grade TiO2 and SiO2).

As expected, at the low starting food concentrations of boscalid (10 and 150 ppm) and iENMs (1% w/w) used in these studies, which were chosen based on regulations that dictate presumably safe levels for foods, none of these substances by themselves caused appreciable adverse effects in a small intestinal epithelial model. No differences in monolayer integrity (TEER) or cell viability (metabolic activity) were observed between cells treated with digesta from FFM controls and those treated with digesta from FFM containing either boscalid, iENM, or both boscalid and iENMs (Figure 5A and 5B). Likewise, neither boscalid alone, at a starting concentration of 10 ppm, nor SiO2 alone caused a significant increase in ROS production (Figure 5C), and neither boscalid, TiO2 or SiO2 alone caused meaningful and significant cytotoxicity (Figure 5D). TiO2 alone, and boscalid alone at 150 ppm did cause significant increases in ROS production (Figure 5C). This is not particularly surprising, since toxic effects of TiO2 have been reported with increasing frequency 19,27,44–50, leading to a recent reevaluation of its safety and suitability as a food additive by some countries, and since the 150 ppm level of boscalid applies to food products that are consumed in small quantities (e.g., herbs), whereas for foods consumed in larger amounts, the allowable limits are considerably lower. Those exceptions notwithstanding, the most notable finding of these toxicity studies was that meaningful and significant adverse effects were produced primarily by combinations of iENMs and boscalid, and that those combined effects were significantly greater than the effects, if any, of the iENM or boscalid alone. ROS production induced by TiO2 was substantially increased in the presence of boscalid, SiO2 induced significant ROS production only in combination with 150 ppm boscalid (Figure 5C), and only combinations of 150 ppm boscalid and either TiO2 or SiO2 caused meaningful, statistically significant increases in cytotoxicity (p<0.005) (Figure 5D). Cytotoxicity and ROS production in cells exposed to combined iENM and boscalid were greater than in cells exposed to iENMs or boscalid alone, and roughly equal to the sum of effects of individual treatments (i.e., effects were additive, not synergistic).

These data demonstrating exaggerated adverse effects of digestas containing both boscalid and iENM on epithelial cell health, relative to those caused by either boscalid or iENM alone, suggest that although ingestion of boscalid or iENM alone at allowed food levels may be relatively safe, co-ingestion of boscalid and either E171 or E551 iENM food additives may pose an unforeseen health risk. Moreover, Nano-TiO2 and nano-SiO2 have been recently found to induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), by which cells attain migratory and invasive properties, eventually leading to cancer metastasis 51. EMT has been also shown to account, at least in part, for the carcinogenic and/or fibrogenic activities of some pesticides, such as organochlorines 52. Therefore, co-exposure to iENMs (TiO2 and SiO2) and pesticide residues may lead to accelerated EMT, resulting in higher carcinogenic activities.

Furthermore, although iENMs alone were not significantly cytotoxic at the doses used, their presence considerably increased the translocation of boscalid through the small intestinal epithelial cell monolayer (by 20% for TiO2, and 30% for SiO2) (Figure 6D). This finding raises additional concerns for increased health implications due to the presence of iENMs in food.

A number of possible mechanisms may have contributed to the observed increased translocation of boscalid in the presence of iENMs. Diminished epithelial cell health, as indicated by elevated oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in co-exposed cells, could increase membrane permeability or impair the function of efflux transporters, thereby facilitating contaminant translocation across the epithelium. ENMs may also induce changes in metabolic enzyme activity, membrane trafficking, or other cellular functions or structural properties that could contribute to increased cellular uptake and translocation of boscalid. Nano-TiO2 and nano-SiO2 are known to induce leakiness in the endothelium, known as NanoEL (nanomaterial-induced endothelial leakiness) 53, 54. It has also been reported that exposure to some ENMs alters intestinal barrier function, depending on the properties of the ENMs and the co-exposed compounds. For example, exposure to polystyrene NPs caused remodeling of intestinal villi, which increased the surface area available for iron absorption 55, and exposure to TiO2 NPs decreased the transport of iron, zinc and fatty acids by altering nutrient transporter gene expression 56. Co-exposures of iENMs with pesticides may exacerbate such effects. To understand the impact of ENMs on cellular functions that could affect boscalid uptake, cellular expression of genes related to cell stress, toxicity and junctions will be investigated in future studies.

Another possible driver of increased translocation of boscalid in the presence of TiO2 or SiO2 is an increase in the concentration gradient of boscalid across the epithelial layer. TiO2 and SiO2 increased boscalid concentrations in digesta liquid phase by 16% and 30%, respectively (Figure 6), suggesting that the presence of iENMs altered partitioning of boscalid, possibly by displacing boscalid bound to soluble or flocculated proteins in the digesta, resulting in an increased concentration of free boscalid available for translocation. Molecules that passively diffuse from the GIT lumen to the blood stream do so in direct proportion to their concentration gradients across the epithelial layer. Although the oral bioavailability and mechanism for intestinal absorption of boscalid have not been reported to our knowledge, its known properties (low molecular weight, hydrophobic, few hydrogen bond donors and acceptors) suggest that it would likely be readily absorbed by passive diffusion57.

The affinity of boscalid for SiO2 in particular, and to a lesser extent TiO2, demonstrated by the Nano-ITC results (Figure S1 and S2) suggest that these ENMs may also have contributed to cellular uptake and translocation of boscalid by acting as carrier molecules. Translocation of these ENMs from digesta across the triculture layer will be investigated in future studies. If translocation occurred, boscalid adsorbed to ENM surfaces would be co-translocated with them. The greater affinity of boscalid for SiO2 than for TiO2 would also be consistent with a role for such a mechanism. However, the binding kinetic studies using Nano-ITC analysis were performed in non-physiological conditions (50% ethanol in water), and binding affinity between ENMs and co-ingested molecules could be substantially different in a complex physiologically realistic digesta. Additional studies are needed to assess the affinity of boscalid for iENMs, as well as that of boscalid and iENMs for digestive proteins, in physiological digesta conditions.

Further studies are needed to assess the contribution, if any, of each of the possible mechanisms suggested here, or of other unknown mechanisms, to the increased epithelial translocation of boscalid in the presence of TiO2 and SiO2. Considering limitations of in vitro models, further in vivo studies are needed to validate the findings in this study. Moreover, the fasting food model used in this study is the most simplistic, and perhaps not very realistic or probable food matrix in which iENMs and/or pesticides might be consumed. It has been shown in previous studies that the food matrix can alter the cytotoxicity of iENMs. For example, we have shown in a previous study that cytotoxic effects on tri-culture intestinal epithelium observed with digesta from TiO2 in FFM were significantly dampened in digesta of TiO2 when a standardized food model (SFM) based on the average American diet was used 32. Therefore, potential food matrix (or diet) effects on observed co-exposure effects would need to be investigated in future studies. Furthermore, the effects observed in this study are almost certain to be pesticide-specific. Therefore, additional studies are also needed to include other pesticides of interest, such as glyphosate, a hydrophilic pesticide sold under the trade name Roundup, and paraquat, a toxic chemical widely used as an herbicide.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the co-exposure of the food additives TiO2 (E171) and SiO2 (E551), which contain a considerable fraction of nanosized particles, and the pesticide boscalid, including the potential effects on oral bioavailability (uptake by and translocation across the intestinal epithelium) of the pesticide. The results revealed low to moderate levels of toxicity for boscalid and for food-grade TiO2 and SiO2 individually at the low but relevant doses used in the study, but significantly greater, roughly additive, cytotoxic effects for boscalid and iENM co-exposure. More importantly, both TiO2 and SiO2 substantially and significantly increased uptake and translocation of boscalid in an in vitro model of small intestinal epithelium. This raises serious concerns for potential health implications from such possible co-exposure scenarios for humans.

Multiple mechanisms may contribute to this effect, including impaired epithelial cell health or integrity (as suggested by observed, though modest, increases in oxidative stress and cytotoxicity), resulting in increased plasma membrane permeability, impaired efflux transporter function, or alterations in other cellular processes, and displacement of bound boscalid from the soluble or flocculated solid proteins by iENMs, thereby increasing the concentration of boscalid in liquid phase and the boscalid concentration gradient at the cell surface.

Significantly increasing the oral bioavailability of environmental xenobiotics such as boscalid could represent an additional potential risk, beyond direct toxic effects, for these widely used iENMs. Further studies are needed to better understand the mechanisms for this effect, and to explore the impacts of these and other iENMs on bioavailability of other environmental contaminants in the food supply.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support for the research was provided by (NIEHs grant # U24ES026946) as part of the Nanotechnology Health Implications Research Consortium, the Nanyang Technological University-Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Initiative for Sustainable Nanotechnology and the HSPH-NIEHS Environmental Health Center Grant (grant # ES-000002). The engineered nanomaterials used in the research presented in this publication were characterized and provided by the Engineered Nanomaterials Resource and Coordination Core established at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (NIH grant # U24ES026946) as part of the Nanotechnology Health Implications Research Consortium. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.DeLoid GM, Sohal IS, Lorente LR, Molina RM, Pyrgiotakis G, Stevanovic A, Zhang R, McClements DJ, Geitner NK, Bousfield DW, Ng KW, Loo SCJ, Bell DC, Brain J and Demokritou P, Reducing Intestinal Digestion and Absorption of Fat Using a Nature-Derived Biopolymer: Interference of Triglyceride Hydrolysis by Nanocellulose, ACS Nano, 2018, 12, 6469–6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaze N, Jiang Y, Mena L, Zhang Y, Bello D, Leonard SS, Morris AM, Eleftheriadou M, Pyrgiotakis G and Demokritou P, An integrated electrolysis – electrospray – ionization antimicrobial platform using Engineered Water Nanostructures (EWNS) for food safety applications, Food Control, 2018, 85, 151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eleftheriadou M, Pyrgiotakis G and Demokritou P, Nanotechnology to the rescue: using nano-enabled approaches in microbiological food safety and quality, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol, 2017, 44, 87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoepf JJ, Bi Y, Kidd J, Herckes P, Hristovski K and Westerhoff P, Detection and dissolution of needle-like hydroxyapatite nanomaterials in infant formula, NanoImpact, 2017, 5, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes CJ, Current Commentary Eating small : applications and implications for nano- technology in agriculture and the food industry, Sci. Prog, 2014, 97, 173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Seiber JN and Hotze M, ACS select on nanotechnology in food and agriculture: A perspective on implications and applications, J. Agric. Food Chem, 2014, 62, 1209–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomer MCE, Hutchinson C, Volkert S, Greenfield SM, Catterall A, Thompson RPH and Powell JJ, Dietary sources of inorganic microparticles and their intake in healthy subjects and patients with Crohn’s disease, Br. J. Nutr, 2004, 92, 947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain A, Ranjan S, Dasgupta N and Ramalingam C, Nanomaterials in food and agriculture: An overview on their safety concerns and regulatory issues, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr, 2018, 58, 297–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClements DJ and Xiao H, Is nano safe in foods? Establishing the factors impacting the gastrointestinal fate and toxicity of organic and inorganic food-grade nanoparticles, npj Sci. Food, 2017, 1, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sohal IS, Cho YK, O’Fallon KS, Gaines P, Demokritou P and Bello D, Dissolution Behavior and Biodurability of Ingested Engineered Nanomaterials in the Gastrointestinal Environment, ACS Nano, 2018, 12, 8115–8128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohal IS, O’Fallon KS, Gaines P, Demokritou P and Bello D, Ingested engineered nanomaterials: state of science in nanotoxicity testing and future research needs, Part. Fibre Toxicol, 2018, 15, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Chen Z, Ba T, Pu J, Chen T, Song Y, Gu Y, Qian Q, Xu Y, Xiang K, Wang H and Jia G, Susceptibility of Young and Adult Rats to the Oral Toxicity of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles, Small, 2013, 9, 1742–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X-X, Cheng B, Yang Y-X, Cao A, Liu J-H, Du L-J, Liu Y, Zhao Y and Wang H, Characterization and Preliminary Toxicity Assay of Nano-Titanium Dioxide Additive in Sugar-Coated Chewing Gum, Small, 2013, 9, 1765–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weir A, Westerhoff P, Fabricius L, Hristovski K and von Goetz N, Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products, Environ. Sci. Technol, 2012, 46, 2242–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sycheva LP, Zhurkov VS, Iurchenko VV, Daugel-Dauge NO, Kovalenko MA, Krivtsova EK and Durnev AD, Investigation of genotoxic and cytotoxic effects of micro- and nanosized titanium dioxide in six organs of mice in vivo, Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen, 2011, 726, 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui Y, Gong X, Duan Y, Li N, Hu R, Liu H, Hong M, Zhou M, Wang L, Wang H and Hong F, Hepatocyte apoptosis and its molecular mechanisms in mice caused by titanium dioxide nanoparticles, J. Hazard. Mater, 2010, 183, 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bu Q, Yan G, Deng P, Peng F, Lin H, Xu Y, Cao Z, Zhou T, Xue A, Wang Y, Cen X and Zhao Y-L, NMR-based metabonomic study of the sub-acute toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in rats after oral administration, Nanotechnology, 2010, 21, 125105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui Y, Liu H, Zhou M, Duan Y, Li N, Gong X, Hu R, Hong M and Hong F, Signaling pathway of inflammatory responses in the mouse liver caused by TiO2 nanoparticles, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A, 2011, 96A, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gui S, Zhang Z, Zheng L, Cui Y, Liu X, Li N, Sang X, Sun Q, Gao G, Cheng Z, Cheng J, Wang L, Tang M and Hong F, Molecular mechanism of kidney injury of mice caused by exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles, J. Hazard. Mater, 2011, 195, 365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters R, Kramer E, Oomen AG, Herrera Rivera ZE, Oegema G, Tromp PC, Fokkink R, Rietveld A, Marvin HJP, Weigel S, Peijnenburg AACM and Bouwmeester H, Presence of Nano-Sized Silica during In Vitro Digestion of Foods Containing Silica as a Food Additive, ACS Nano, 2012, 6, 2441–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dekkers S, Krystek P, Peters RJB, Lankveld DPK, Bokkers BGH, van Hoeven-Arentzen PH, Bouwmeester H and Oomen AG, Presence and risks of nanosilica in food products, Nanotoxicology, 2011, 5, 393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Du L, Song Z and Chen X, Progress in the characterization and safety evaluation of engineered inorganic nanomaterials in food, Nanomedicine, 2013, 8, 2007–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.So SJ, Jang IS and Han CS, Effect of Micro/Nano Silica Particle Feeding for Mice, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol, 2008, 8, 5367–5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusoff R, Nguyen LTH, Chiew P, Wang ZM and Ng KW, Comparative differences in the behavior of TiO2 and SiO2 food additives in food ingredient solutions, J. Nanoparticle Res, 2018, 20, 76. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D, Hu J, Forthaus BE and Wang J, Synergistic toxic effect of nano-Al 2O 3 and As(V) on Ceriodaphnia dubia, Environ. Pollut, 2011, 159, 3003–3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang Y, Li S, Qiao J, Wang H and Li L, Synergistic effects of nano-sized titanium dioxide and zinc on the photosynthetic capacity and survival of Anabaena sp, Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2013, 14, 14395–14407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Guo Y, Hu C, Lam PKS, Lam JCW and Zhou B, Dysbiosis of gut microbiota by chronic coexposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles and bisphenol A: Implications for host health in zebrafish, Environ. Pollut, 2018, 234, 307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D, Hu J, Irons DR and Wang J, Synergistic toxic effect of nano-TiO2 and As(V) on Ceriodaphnia dubia, Sci. Total Environ, 2011, 409, 1351–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi Y, Zhang J-H, Jiang M, Zhu L-H, Tan H-Q and Lu B, Synergistic genotoxicity caused by low concentration of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and p,p ′-DDT in human hepatocytes, Environ. Mol. Mutagen, 2009, 51, NA-NA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo M, Xu X, Yan X, Wang S, Gao S and Zhu S, In vivo biodistribution and synergistic toxicity of silica nanoparticles and cadmium chloride in mice, J. Hazard. Mater, 2013, 260, 780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClements DJ, DeLoid G, Pyrgiotakis G, Shatkin JA, Xiao H and Demokritou P, The role of the food matrix and gastrointestinal tract in the assessment of biological properties of ingested engineered nanomaterials (iENMs): State of the science and knowledge gaps, NanoImpact, 2016, 3–4, 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Zhang Z, Zhang R, Xiao H, Bhattacharya K, Bitounis D, Demokritou P and McClements DJ, Development of a standardized food model for studying the impact of food matrix effects on the gastrointestinal fate and toxicity of ingested nanomaterials, NanoImpact, 2019, 13, 13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao X, Ma C, Gao Z, Zheng J, He L, McClements DJ and Xiao H, Characterization of the Interactions between Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles and Polymethoxyflavones Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy, J. Agric. Food Chem, 2016, 64, 9436–9441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao X, Han Y, Li F, Li Z, McClements DJ, He L, Decker EA, Xing B and Xiao H, Impact of protein-nanoparticle interactions on gastrointestinal fate of ingested nanoparticles: Not just simple protein corona effects, NanoImpact, 2019, 13, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeLoid GM, Wang Y, Kapronezai K, Lorente LR, Zhang R, Pyrgiotakis G, Konduru NV, Ericsson M, White JC, De La Torre-Roche R, Xiao H, McClements DJ and Demokritou P, An integrated methodology for assessing the impact of food matrix and gastrointestinal effects on the biokinetics and cellular toxicity of ingested engineered nanomaterials, Part. Fibre Toxicol, 2017, 14, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurin M-C and Bostanian NJ, Short-term contact toxicity of seven fungicides onAnystis baccarum, Phytoparasitica, 2007, 35, 380–385. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bostanian NJ, Thistlewood HMA, Hardman JM and Racette G, Toxicity of six novel fungicides and sulphur to Galendromus occidentalis (Acari: Phytoseiidae), Exp. Appl. Acarol, 2009, 47, 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angioni A, Dedola F, Garau VL, Schirra M and Caboni P, Fate of Iprovalicarb, Indoxacarb, and Boscalid Residues in Grapes and Wine by GC–ITMS Analysis, J. Agric. Food Chem, 2011, 59, 6806–6812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hochella MF, Mogk DW, Ranville J, Allen IC, Luther GW, Marr LC, McGrail BP, Murayama M, Qafoku NP, Rosso KM, Sahai N, Schroeder PA, Vikesland P, Westerhoff P and Yang Y, Natural, incidental, and engineered nanomaterials and their impacts on the Earth system., Science, 2019, 363, eaau8299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen JM, Beltran-Huarac J, Pyrgiotakis G and Demokritou P, Effective delivery of sonication energy to fast settling and agglomerating nanomaterial suspensions for cellular studies: Implications for stability, particle kinetics, dosimetry and toxicity, NanoImpact, 2018, 10, 81–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De La Torre-Roche R, Hawthorne J, Deng Y, Xing B, Cai W, Newman LA, Wang Q, Ma X, Hamdi H and White JC, Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes and C 60 Fullerenes Differentially Impact the Accumulation of Weathered Pesticides in Four Agricultural Plants, Environ. Sci. Technol, 2013, 47, 12539–12547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JY, Wang H, Pyrgiotakis G, DeLoid GM, Zhang Z, Beltran-Huarac J, Demokritou P and Zhong W, Analysis of lipid adsorption on nanoparticles by nanoflow liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, Anal. Bioanal. Chem, 2018, 410, 6155–6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Younes M, Aggett P, Aguilar F, Crebelli R, Dusemund B, Filipič M, Frutos MJ, Galtier P, Gott D, Gundert‐Remy U, Kuhnle GG, Leblanc J, Lillegaard IT, Moldeus P, Mortensen A, Oskarsson A, Stankovic I, Waalkens‐Berendsen I, Woutersen RA, Wright M, Boon P, Chrysafidis D, Gürtler R, Mosesso P, Parent‐Massin D, Tobback P, Kovalkovicova N, Rincon AM, Tard A, Lambré C and Lambré C, Re‐evaluation of silicon dioxide (E 551) as a food additive, EFSA J, , DOI: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Faust JJ, Doudrick K, Yang Y, Westerhoff P and Capco DG, Food grade titanium dioxide disrupts intestinal brush border microvilli in vitro independent of sedimentation., Cell Biol. Toxicol, 2014, 30, 169–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gheshlaghi ZN, Riazi GH, Ahmadian S, Ghafari M and Mahinpour R, Toxicity and interaction of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with microtubule protein., Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai), 2008, 40, 777–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lomer MCE, Hutchinson C, Volkert S, Greenfield SM, Catterall A, Thompson RPH and Powell JJ, Dietary sources of inorganic microparticles and their intake in healthy subjects and patients with Crohn’s disease., Br. J. Nutr, 2004, 92, 947–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorier M, Béal D, Marie-Desvergne C, Dubosson M, Barreau F, Houdeau E, Herlin-Boime N and Carriere M, Continuous in vitro exposure of intestinal epithelial cells to E171 food additive causes oxidative stress, inducing oxidation of DNA bases but no endoplasmic reticulum stress, Nanotoxicology, 2017, 11, 751–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jovanović B, Jovanović N, Cvetković VJ, Matić S, Stanić S, Whitley EM and Mitrović TL, The effects of a human food additive, titanium dioxide nanoparticles E171, on Drosophila melanogaster - a 20 generation dietary exposure experiment., Sci. Rep, 2018, 8, 17922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proquin H, Rodríguez-Ibarra C, Moonen CGJ, Urrutia Ortega IM, Briedé JJ, de Kok TM, van Loveren H and Chirino YI, Titanium dioxide food additive (E171) induces ROS formation and genotoxicity: contribution of micro and nano-sized fractions, Mutagenesis, 2017, 32, 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Natarajan V, Wilson CL, Hayward SL and Kidambi S, Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Trigger Loss of Function and Perturbation of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Primary Hepatocytes., PLoS One, 2015, 10, e0134541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Setyawati MI, Sevencan C, Bay BH, Xie J, Zhang Y, Demokritou P and Leong DT, Nano-TiO 2 Drives Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Intestinal Epithelial Cancer Cells, Small, 2018, 14, 1800922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zucchini-Pascal N, Peyre L, de Sousa G and Rahmani R, Organochlorine pesticides induce epithelial to mesenchymal transition of human primary cultured hepatocytes, Food Chem. Toxicol, 2012, 50, 3963–3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Setyawati MI, Tay CY, Chia SL, Goh SL, Fang W, Neo MJ, Chong HC, Tan SM, Loo SCJ, Ng KW, Xie JP, Ong CN, Tan NS and Leong DT, Titanium dioxide nanomaterials cause endothelial cell leakiness by disrupting the homophilic interaction of VE–cadherin, Nat. Commun, 2013, 4, 1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng F, Setyawati MI, Tee JK, Ding X, Wang J, Nga ME, Ho HK and Leong DT, Nanoparticles promote in vivo breast cancer cell intravasation and extravasation by inducing endothelial leakiness, Nat. Nanotechnol, 2019, 14, 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahler GJ, Esch MB, Tako E, Southard TL, Archer SD, Glahn RP and Shuler ML, Oral exposure to polystyrene nanoparticles affects iron absorption, Nat. Nanotechnol, 2012, 7, 264–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo Z, Martucci NJ, Moreno-Olivas F, Tako E and Mahler GJ, Titanium dioxide nanoparticle ingestion alters nutrient absorption in an in vitro model of the small intestine, NanoImpact, 2017, 5, 70–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW and Feeney PJ, Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings., Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev, 2001, 46, 3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen JM, DeLoid GM, Pyrgiotakis G and Demokritou P, Interactions of engineered nanomaterials in physiological media and implications for in vitro dosimetry, Nanotoxicology, 2013, 7, 417–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DeLoid GM, Cohen JM, Pyrgiotakis G and Demokritou P, Preparation, characterization, and in vitro dosimetry of dispersed, engineered nanomaterials, Nat. Protoc, 2017, 12, 355–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.