Abstract

Background

Interindividual variability in 24-hour energy expenditure (24EE) during energy-balance conditions is mainly determined by differences in body composition and demographic factors. Previous studies suggested that 24EE might also be influenced by sympathetic nervous system activity via catecholamine (norepinephrine, epinephrine) secretion. Therefore, we analyzed the association between catecholamines and energy expenditure in 202 individuals from a heterogeneous population of mixed ethnicities.

Methods

Participants (n = 202, 33% female, 14% black, 32% white, 41% Native American, 11% Hispanic, age: 36.9 ± 10.3 y [mean ± SD], percentage body fat: 30.3 ± 9.4) resided in a whole-room calorimeter over 24 hours during carefully controlled energy-balance conditions to measure 24EE and its components: sleeping metabolic rate (SMR), awake-fed thermogenesis (AFT), and spontaneous physical activity (SPA). Urine samples were collected, and 24-h urinary epinephrine and norepinephrine excretion rates were assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography.

Results

Both catecholamines were associated with 24EE and SMR (norepinephrine: +27 and +19 kcal/d per 10 μg/24h; epinephrine: +18 and +10 kcal/d per 1 μg/24h) in separate analyses after adjustment for age, sex, ethnicity, fat mass, fat-free mass, calorimeter room, temperature, and physical activity. In a multivariate model including both norepinephrine and epinephrine, only norepinephrine was independently associated with both 24EE and SMR (both P < .008), whereas epinephrine became insignificant. Neither epinephrine nor norepinephrine were associated with adjusted AFT (both P = .37) but epinephrine was associated with adjusted SPA (+0.5% per 1 μg/24h).

Conclusions

Our data provide compelling evidence that sympathetic nervous system activity, mediated via norepinephrine, is a determinant of human energy expenditure during nonstressed, eucaloric conditions.

Keywords: obesity, energy expenditure, catecholamines, sympathetic nervous system, epinephrine, norepinephrine

Interindividual differences in 24-hour energy expenditure (24EE) are mainly explained by differences in body composition, age, sex, and ethnicity (1–4). Although these measures account for up to approximately 85% of the variance in 24EE among individuals, the remaining approximately 15% are still unexplained. Previous studies suggested that the extent of activity of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) might also affect energy expenditure (EE) (5–7).

The SNS plays an important role in modulating heart rate, blood pressure, lipolysis, brown adipose tissue activity, and digestion (8, 9). These effects are mediated by the tyrosine-derived catecholamines (dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine), which can act as sympathetic neurotransmitters and/or hormones that bind to α-adrenergic and β-adrenergic receptors in target tissues (10). The SNS can be divided into 2 branches (11): i) The “central sympathetic” branch releases norepinephrine (the metabolite derived from dopamine and the main sympathetic neurotransmitter) from postganglionic sympathetic nerve endings directly into target tissues. Owing to synaptic spillover and, to lesser extent, adrenal secretion, norepinephrine also accumulates in the bloodstream (12); ii) the “sympathoadrenal” branch is represented by the adrenal medulla, whose chromaffin cells almost exclusively secrete epinephrine (the metabolite derived from norepinephrine) into circulation (10, 12). Both branches can be specifically, and somewhat independently, activated by different stressors, for example, cold exposure or overeating generally lead to a greater central sympathetic activation whereas emotional stressors largely activate the sympathoadrenal branch (11, 13).

Seminal studies by Young, Landsberg, and others have shown that diet- and cold-induced increases in catecholamines are associated with concomitant increases in thermogenesis in rodents and humans (13-18). Further, treatment with catecholamines and catecholamine reuptake inhibitors increases thermogenesis in humans (14, 19-21). In line with these findings, 2 studies reported a positive association between norepinephrine—but not epinephrine—and the unexplained variance of 24EE measures during nonstressed, eucaloric conditions (2, 22). However, in the first study, catecholamines were analyzed in plasma and not in urine (2)—which could constitute a limitation because catecholamines may vary according to exposure and time of day (23)—whereas in the second study, only male individuals of white and Native American descent were analyzed (22).

Thus, in this cross-sectional study, we measured 24EE, the components of 24EE, and urinary catecholamine concentrations in a larger and more heterogeneous population (n = 202 participants) of mixed ethnicities during 24 hours of carefully controlled energy-balance conditions to assess the associations between urinary catecholamines and accurate measure of energy metabolism in healthy adults.

Material and Methods

Participants

For this cross-sectional analysis, we used data from 4 different studies that were conducted from 2009 to 2017 on our research unit in Phoenix, Arizona, and that had similar baseline procedures and logistics. In total, 202 individuals were included in the analysis (Table 1) (24). Individuals who participated in multiple studies were included only once (at their first study participation). Inclusion criteria for the current analysis were valid measurements of 1) 24EE during energy-balance conditions (percentage deviation from exact energy balance [defined as 24-hour energy intake minus 24EE] between –20% and 20%), 2) urinary catecholamines from 24-hour urine collection, and 3) body composition. All individuals were 18 years or older and living in or nearby Phoenix, Arizona. All participants were weight stable (variation < 2.3 kg within past 6 months) before admission by self-report and were confirmed to be healthy by history, physical examination, and fasting blood tests. Drug tests were performed before admission to exclude recent use of alcohol, cigarettes, and other drugs that might alter SNS activity. All participants provided written informed consent before any study procedures began. The institutional review board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases approved all 4 studies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort (n = 202)

| Demographic Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Male (%) | 136 (67.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Native American | 83 (41.1) |

| White | 65 (32.2) |

| Black | 28 (13.9) |

| Hispanic | 23 (11.4) |

| Otherb | 3 (1.5) |

| Age, y | 36.9 ± 10.3 (18, 66) |

| Body composition measurements | |

| Height (cm) | 170.3 ± 8.8 (150.5, 195.0) |

| Body weight (kg) | 89.2 ± 21.9 (47.5, 171.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.8 ± 7.7 (17.7, 60.6) |

| Body fat (%) | 30.3 ± 9.4 (7.6, 51.8) |

| FM (kg) | 28.1 ± 13.7 (5.3, 83.3) |

| FFM (kg) | 61.1 ± 12.1 (35.5, 100.6) |

| Energy expenditure measurements during 24-h energy balance | |

| 24EE (kcal/day) | 2150 ± 373 (1350, 3378) |

| Food intake (kcal/day) | 2218 ± 353 (1461, 3353) |

| Energy balance (kcal/day) | 69 ± 147 (–348, 422) |

| Energy balance (%) | 3.7 ± 6.8 (–14.1, 20.0) |

| SMR (kcal/day) | 1662 ± 282 (1060, 2559) |

| 24RQ (ratio) | 0.86 ± 0.04 (0.70, 1.02) |

| EE0 (kcal/15h) | 1422 ± 245 (916, 2192) |

| AFT (kcal/15h) | 384 ± 112 (145, 710) |

| Lipid oxidation (kcal/day) | 707 ± 352 (–385, 1925) |

| Carbohydrate oxidation (kcal/day) | 1031 ± 336 (–194, 2095) |

| Protein oxidation (kcal/day) | 385 ± 104 (149, 1094) |

| SPA (%) | 7.1 ± 4.5 (0.4, 27.5) |

| Urinary catecholamines during energy balance | |

| Norepinephrine (μg/24h) | 34.3 ± 16.9 (6.4, 114.6); 30.5, 23.2-42.7a |

| Epinephrine (μg/24h) | 4.1 ± 2.0 (1.0, 13.2); 3.6, 2.6-5.0a |

| Epinephrine-to-norepinephrine ratio | 0.14 ± 0.08 (0.02, 0.53); 0.12, 0.08-0.17a |

| Urinary metanephrines during energy balance | |

| Normetanephrine (μg/24h) | 276.5 ± 126.7 (65.5, 792.0); 251.1, 191.4-324.2a |

| Metanephrine (μg/24h) | 118.2 ± 47.7 (23.8, 305.1); 113.9, 87.8-141.8a |

| Measurements of glucose metabolism | |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 94.1 ± 7.7 (77, 118) |

| 2-h glucose during OGTT (mg/dL) | 121.1 ± 29.0 (53, 194) |

| Total glucose AUC during OGTT (μIU/mL × 180 min) | 22 752 ± 3,908 (13 853, 34 800) |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/mL) | 13.9 ± 15.7 (1.2, 147.5); 9.0, 6.0-16.5a |

| 2-h insulin during OGTT (μIU/mL) | 121 ± 29.0 (4.0, 1100.0); 60.0, 32.0-121.5a |

| Total insulin AUC during OGTT (μIU/mL × 180 min) | 16 881 ± 15 221 (2895, 129 885); 12 255, 7673-20 085a |

Values are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables or number (frequency) for categorical variables with minimum and maximum in parentheses.

Abbreviations: 24EE, 24-hour energy expenditure; 24RQ, 24-hour respiratory quotient, AFT, awake-fed thermogenesis; AUC, area under the curve; BMI, body mass index; EE0, energy expenditure in the inactive, awake state; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; SMR, sleeping metabolic rate; SPA, spontaneous physical activity.

aSkewed values are also expressed as medians with interquartile ranges.

bOther ethnicities comprise 1 individual of Asian and 2 individuals of unknown ethnicity.

On admission to the clinical research unit, participants were placed on a standard weight-maintaining diet (WMD; 50% carbohydrate, 30% fat, and 20% protein), using unit-specific equations based on weight and sex (25). Daily fasting body weight measured by calibrated scale was maintained within 1% of the admission weight during the inpatient period by adjusting, if necessary, daily energy intake of the WMD (26). Participants were instructed to refrain from vigorous exercise and to restrict their activities to those available in the research unit during their stay. Diabetes was excluded in all 202 participants based on oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) performed after 3 days on the WMD as part of the standard procedures of the study protocols (27). Plasma glucose concentrations were measured using the Analox GM9 glucose oxidase method (Analox Instruments USA Inc). Insulin concentrations were measured by an automated immunoenzymometric assay (Tosoh Bioscience Inc). Body fat mass (FM), fat-free mass (FFM), and percentage fat (PFAT) were estimated by total-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (DPX-1 and DPX-L; Lunar Radiation). To account for the usage of different DXA machines over time, previously validated regression equations were used to make DXA data comparable across different DXA machines (28).

Energy expenditure measurements

Twenty-four–hour EE and substrate oxidation were assessed in a large, open-circuit indirect whole-room calorimeter (respiratory chamber), as previously described (29). Before entering the calorimeter, participants received breakfast at 7 am. During the 24 hours inside the respiratory chamber, total energy intake was equal to approximately 80% of the WMD to account for the limited physical activity inside the calorimeter. Three meals were provided to volunteers via an airlock at 11 am, 4 pm, and 7 pm. All unconsumed food was returned to the metabolic kitchen for weighing for accurate calculation of intake. The 24-hour energy balance was calculated as the difference between actual energy intake minus 24EE. Carbohydrate and fat oxidation rates were calculated from the 24-hour respiratory quotient (24RQ), accounting for protein oxidation calculated from the measurement of 24-hour urinary nitrogen excretion (30).

We also calculated the components of 24EE, namely, sleeping metabolic rate (SMR), the awake-fed thermogenesis (AFT, a surrogate for diet-induced thermogenesis [DIT] including cost of arousal (31)), the EE in the inactive, awake state (EE0, representing daytime EE at zero physical activity (32)), and the energy cost of spontaneous physical activity (SPA). The EE0 was calculated as the intercept of the regression line between EE and SPA 1-minute data points between 10 am and 1 am and then extrapolated to 15 hours, as previously described (31). Participants’ SPA was measured by radar sensors and expressed as the percentage of time when activity was detected (33). SMR was calculated as the average EE between 11:30 pm and 5 am overnight when participant movement was less than 1.5% (< 0.9 sec/min) and extrapolated to a 24-hour period, as previously described (29). AFT was calculated as the difference between EE0 minus SMR and extrapolated to 15 hours, when the participant was awake and fed (31). Chamber ambient temperature averaged 23.8 ± 2.1°C. Participants were asked to remain sedentary and not to exercise while residing in the respiratory chamber.

Catecholamine measurements

A constant fraction of the circulating concentrations of plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine is excreted into the urine (34, 35) which permits assessment of urinary catecholamine excretion over a 24-hour period instead of a single time point of the blood draw. Studies comparing urinary levels of catecholamines with corresponding determinations of both hormones in plasma indicate a significant positive association between the concentrations obtained from these measurements (34, 36, 37). This was confirmed in the present study by comparative analysis of plasma concentration and 24-hour urinary catecholamine excretion in n = 14 participants with both these measurements (24). Additionally, we assessed urinary normetanephrine and metanephrine, which are the respective O-methylated metabolites of norepinephrine and epinephrine (38).

Urine was collected in a refrigerator inside the calorimeter during each 24EE assessment, then stored at –70°C until measured for the 24-hour excretion rate of norepinephrine, epinephrine, normetanephrine, and metanephrine to evaluate SNS activity. The diet given inside the respiratory chamber did not contain any caffeinated or alcoholic beverages, or catecholamine-rich foods that could alter physiologic urinary catecholamine levels.

Urinary catecholamines and metanephrines were measured by Mayo Clinic Laboratories using high-performance liquid chromatography (39). The catecholamine and metanephrine excretion rate over 24 hours was obtained by multiplying catecholamine/metanephrine concentration (μg/L) by urinary volume (L) and extrapolating urine collection time to 24 hours in cases for which it was different from 24 hours. The mean ± SD urinary collection time was 23.4 ± 2.0 hours. Throughout the manuscript, the terms norepinephrine, epinephrine, and catecholamines refer to urinary excretion rates. Epinephrine and norepinephrine separated by study group are shown in Supplemental Fig. 3 (24). We detected a storage time effect on norepinephrine (r = 0.15, P = .03) but not on epinephrine (P = .63) and on both metanephrines (both P > .16) (24).

According to the Mayo Clinic laboratory reference ranges for catecholamines (https://neurology.testcatalog.org/show/CATU), all epinephrine levels were within normal range (<21 μg/24 h), whereas norepinephrine levels of 17 participants (8%) were outside the normal range (15-80 μg/24 h). Therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding these participants with above-normal norepinephrine levels, which led to similar results (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS 9.3, Enterprise guide version 5.1; SAS Institute). Data are expressed as mean ± SD, except for skewed data, which are expressed as median with interquartile range. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Epinephrine and norepinephrine were log10-transformed to meet the assumptions of parametric tests (ie, homoscedasticity and Gaussian distribution of data). The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to quantify the associations between catecholamines and EE, body composition, or demographic parameters. Differences in catecholamine levels among ethnicities were assessed with ANOVA with post hoc adjustments (Tukey method). The total area under the curve (AUC) during the OGTT was calculated using the trapezoidal rule.

Multivariate regression analysis was used to adjust values of 24EE and its components by including age, sex, ethnicity, FM, FFM, calorimeter ambient temperature, SPA levels (only 24EE analyses), and calorimeter suite (Room 1 or Room 2) in the regression models as covariates as previously done ((24), 31, 40). Both calorimeter rooms are identical, and participants were randomly assigned to the rooms based on calorimeter availability. Sex, ethnicity, and “study group” showed no interaction effect in all models (data not shown); therefore, we did not perform separate analyses for subgroups of these covariates. We evaluated the independent determinants of norepinephrine and epinephrine by including age, sex, ethnicity, percentage body fat, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and storage time in the regression models as covariates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable regression models for the determinants of 24-hour urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine excretion rates during isocaloric conditions

| Urinary Norepinephrine (μg/24h) Log10-transformed | Urinary Epinephrine (μg/24h) Log10-transformed | |

|---|---|---|

| Explained variance (global P value) | R 2 =0.20 P < .001 | R 2 =0.16 P = .004 |

| Age, y | 0.002 ± 0.002 | –0.001 ± 0.002 |

| (–0.001, 0.005) | (–0.004, 0.002) | |

| Partial r: 0.105 | Partial r: –0.032 | |

| P = .16 | P = .67 | |

| Sex (male) | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.1 ± 0.05 |

| (–0.03, 0.15) | (0.01, 0.19) | |

| Partial r: 0.09 | Partial r: 0.16 | |

| P = .21 | P = .03 | |

| Ethnicity (White) | –0.1 ± 0.12 | –0.11 ± 0.12 |

| (–0.34, 0.13) | (–0.35, 0.12) | |

| Partial r: –0.07 | Partial r: –0.07 | |

| P = 0.38 | P = 0.33 | |

| Ethnicity (Native American) | –0.05 ± 0.12 | –0.15 ± 0.12 |

| (–0.28, 0.18) | (–0.39, 0.08) | |

| Partial r: –0.03 | Partial r: –0.1 | |

| P = .65 | P = .20 | |

| Ethnicity (black) | –0.08 ± 0.12 | –0.03 ± 0.12 |

| (–0.32, 0.16) | (–0.27, 0.21) | |

| Partial r: –0.05 | Partial r: –0.02 | |

| P = .50 | P = .81 | |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | –0.05 ± 0.12 | –0.03 ± 0.12 |

| (–0.29, 0.19) | (–0.27, 0.22) | |

| Partial r: –0.03 | Partial r: –0.02 | |

| P = .70 | P = .83 | |

| Percentage body fat (%) | 0.001 ± 0.003 | –0.003 ± 0.003 |

| (–0.005, 0.006) | (–0.008, 0.003) | |

| Partial r: 0.021 | Partial r: –0.073 | |

| P = .78 | P = .33 | |

| Fasting glucose | 0.002 ± 0.002 | –0.0014 ± 0.0022 |

| (–0.003, 0.006) | (–0.0058, 0.003) | |

| Partial r: 0.052 | Partial r: –0.0465 | |

| P = .49 | P = .53 | |

| Fasting insulin(log10- transformed) | 0.22 ± 0.06 | 0.03 ± 0.06 |

| (0.11, 0.34) | (–0.08, 0.14) | |

| Partial r: 0.28 | Partial r: 0.04 | |

| P = 0.001 | P = .59 | |

| Storage time, mo | 0.00003 ± 0.00002 | 0.000004 ± 0.000019 |

| (–0.00001, 0.00006) | (–0.000034, 0.000041) | |

| Partial r: 0.11 | Partial r: 0.01 | |

| P = .16 | P = .85 | |

| Intercept | 0.52 ± 0.46 | 0.73 ± 0.47 |

| (–0.4, 1.44) | (–0.19, 1.66) | |

| P = .26 | P = .12 |

The β coefficient estimate in each cell is reported with ± SE and the 95% CI in parentheses, along with partial correlations and P value. Significant results are highlighted in bold.

Similar results were obtained when introducing the 3-hour total area under the curve (AUC) of the insulin/glucose response during the oral glucose tolerance test (model with norepinephrine: AUC insulin: partial r = 0.21, P = .005) into the linear model in place of fasting insulin/glucose, when introducing body mass index in the linear model in place of percentage body fat, and after excluding individuals with impaired glucose tolerance (n = 65).

The residual values (observed minus predicted values) of 24EE and its components obtained from these regression models were considered as the unexplained variability in EE measures after adjustment for known EE determinants (40). For each EE variable, adjusted values were then derived by adding the average value calculated in the whole cohort to the residual values obtained by regression analysis. Norepinephrine and epinephrine were then tested as potential determinants of adjusted EE values in univariate (each catecholamine included as the only predictor in the regression model) and multivariate (both catecholamines included as predictors in the same regression model) analyses, where β coefficients were expressed both as absolute values (μg/24h) and as fold-change values with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Sensitivity analyses were also performed by including both norepinephrine and epinephrine in the multivariable regression models of unadjusted EE measures including the aforementioned covariates and similar results were obtained (data not shown). A sample size of 202 individuals had more than 0.80 power (α = 0.05) to detect an increase of 0.01 in R2 attributed to 2 independent variables (norepinephrine and epinephrine) in a linear regression model for 24EE including covariates with a combined total R2 equal to 0.80.

Results

Characteristics of the 202 participants (136 male, 66 female) are shown in Table 1. The average unadjusted 24EE during energy balance was 2150 ± 373 kcal/day and the average 24RQ (0.87) was equal to the expected food quotient of the diet (30). The average deviation from 24-hour energy balance inside the calorimeter was 3.7%, and there were no differences between both calorimeter rooms (P = .10). Epinephrine and norepinephrine correlated with each other (r = 0.31, P < .001), also in a partial correlation after adjustment for body mass index (BMI) (partial r = 0.39, P < .001) (24). Neither catecholamine was associated with age (both P > .30) (24).

Determinants of urinary catecholamine excretion rates

Norepinephrine.

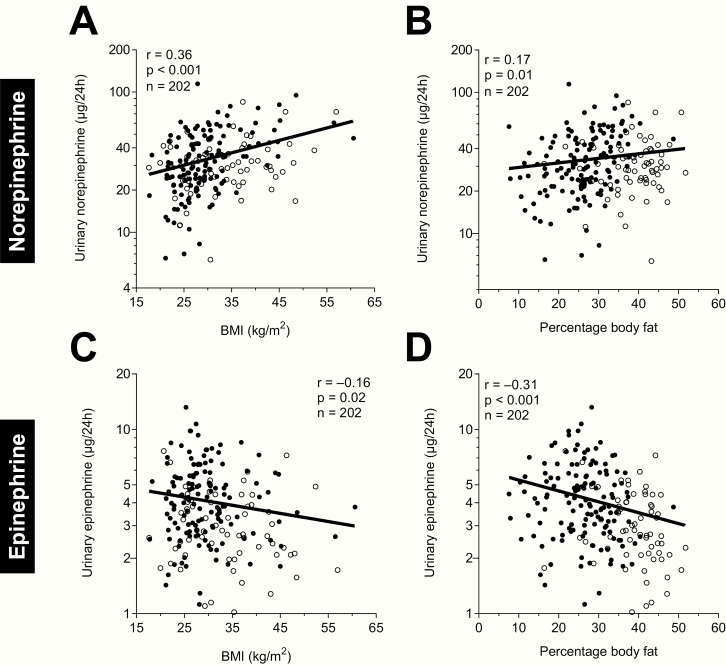

Norepinephrine positively correlated with BMI (r = 0.36, P < .001, Fig. 1A), PFAT (r = 0.17, P = .01, Fig. 1B), fasting insulin (r = 0.38, P < .001), and the total AUC of insulin during the OGTT (r = 0.32, P < .001) (24). After adjustment of norepinephrine by BMI, the association with fasting insulin was still present (r = 0.17, P = .02) but there was no longer an association with the total AUC of insulin during the OGTT (P = .13). To assess the impact of all determinants of norepinephrine concentration in a single model, a multivariate regression analysis was performed. Here, only fasting insulin was an independent determinant of norepinephrine (partial r = 0.28, P = .001, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Associations between adiposity measures and 24-hour urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine excretion rates during isocaloric conditions. Association between urinary norepinephrine excretion and (A), body mass index (BMI) and (B), percentage body fat by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Association between urinary epinephrine excretion and (C), BMI and (D), percentage body fat by DXA. Black circles denote male, white circles denote female participants. Y-axes are formatted on a logarithmic scale (log10) to account for the skewed data distribution of raw catecholamine values.

Epinephrine.

Epinephrine was negatively correlated with BMI (r = –0.16, P = .02, Fig. 1C) and PFAT (r = –0.31, P < .001, Fig. 1D), whereas there were no correlations with fasting insulin and the total AUC of insulin during the OGTT (both P ≥ .13) (24). Results were similar after adjustment of epinephrine by BMI. To assess the impact of all determinants of epinephrine concentration in a single model, a multivariate regression analysis was performed. Here, only sex was an independent predictor of epinephrine (partial r = 0.16, P = .03, Table 2).

Association between urinary catecholamines and energy expenditure measurements

Twenty-four–hour energy expenditure measures.

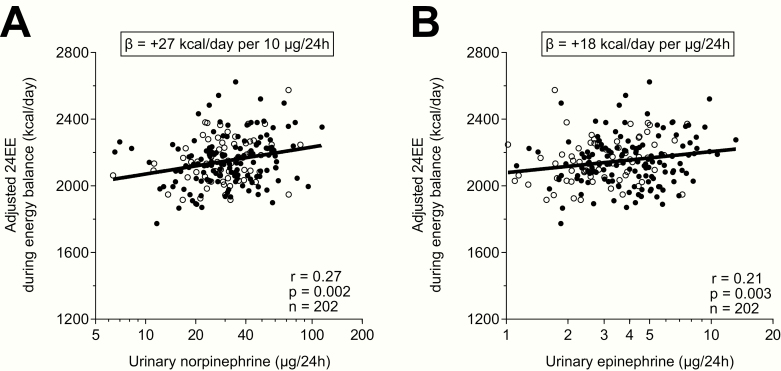

Both norepinephrine (partial r = 0.27, P = .002, Fig. 2A) and epinephrine (partial r = 0.21, P = .003, Fig. 2B) were positively associated with 24EE after adjustment for age, sex, ethnicity, FM, FFM, calorimeter ambient temperature, SPA levels, and calorimeter suite in separate, univariate analyses. Similar results were obtained when adjusting for BMI instead of FM and FFM (norepinephrine: partial r = 0.23, P = .001; epinephrine: partial r = 0.22, P = .003). On average, a 2-fold greater norepinephrine excretion was associated with a greater adjusted 24EE by 201 kcal/day (CI: 98-305 kcal/day), whereas a 2-fold greater epinephrine excretion was associated with a greater adjusted 24EE by 165 kcal/day (CI: 52-269 kcal/day).

Figure 2.

Greater 24-hour urinary (A), norepinephrine and (B), epinephrine excretion rates were associated with relatively higher adjusted 24-hour energy expenditure (24EE) during energy balance and weight stability. On average (A), a greater urinary norepinephrine excretion rate by 10 μg/24h and (B), a greater urinary epinephrine excretion rate by 1 μg/24h were associated with a greater adjusted 24EE by 27 kcal/d (CI: 13 -40 kcal/d) and 18 kcal/day (CI: 7-30 kcal/d), respectively. The adjusted 24EE values were calculated via linear regression analysis including fat-free mass, fat mass, age, sex, ethnicity, calorimeter temperature, spontaneous physical activity, and calorimeter room as covariates after adding the average 24EE to the residual values obtained from the regression model. X-axes are formatted on a logarithmic scale (log10) to account for the skewed data distribution of raw catecholamine values. Black circles denote male, white circles denote female participants.

To determine whether the associations between both catecholamines and 24EE were due to a common upstream signal or due to an independent effect of one specific catecholamine, we included both hormones in the multivariate regression analysis of adjusted 24EE along with covariates. We found that only norepinephrine (partial r = 0.21, P = .004), not epinephrine (P = .08), was an independent determinant of adjusted 24EE. This result for norepinephrine was further confirmed when considering the epinephrine-to-norepinephrine ratio (reflecting the conversion of norepinephrine to epinephrine), which was not a significant determinant of adjusted 24EE (P = .44). We also assessed the direct metabolites of norepinephrine and epinephrine, that is, the 24-hour urinary excretion rate of normetanephrine and metanephrine and found similar associations with regard to adjusted 24EE (24).

Norepinephrine and epinephrine were not associated with 24RQ or lipid oxidation rate during energy balance, either in unadjusted analyses or after adjustment for their known determinants (all P > .31). Norepinephrine was positively associated with unadjusted (r = 0.27, P = .001) but not with adjusted carbohydrate oxidation rate (P = .14), whereas no associations were found for epinephrine (all P > .13). Norepinephrine and epinephrine both were positively associated with unadjusted protein oxidation rate (r = 0.39, P < .001; and r = 0.19, P = .006, respectively); however, after adjustment for covariates, only norepinephrine (partial r = 0.33, P < .001), not epinephrine (P = .06), was associated with adjusted protein oxidation rate (24). The association between norepinephrine and protein oxidation rate remained significant when adjusting for BMI instead of FM and FFM (partial r = 0.35, P < .001).

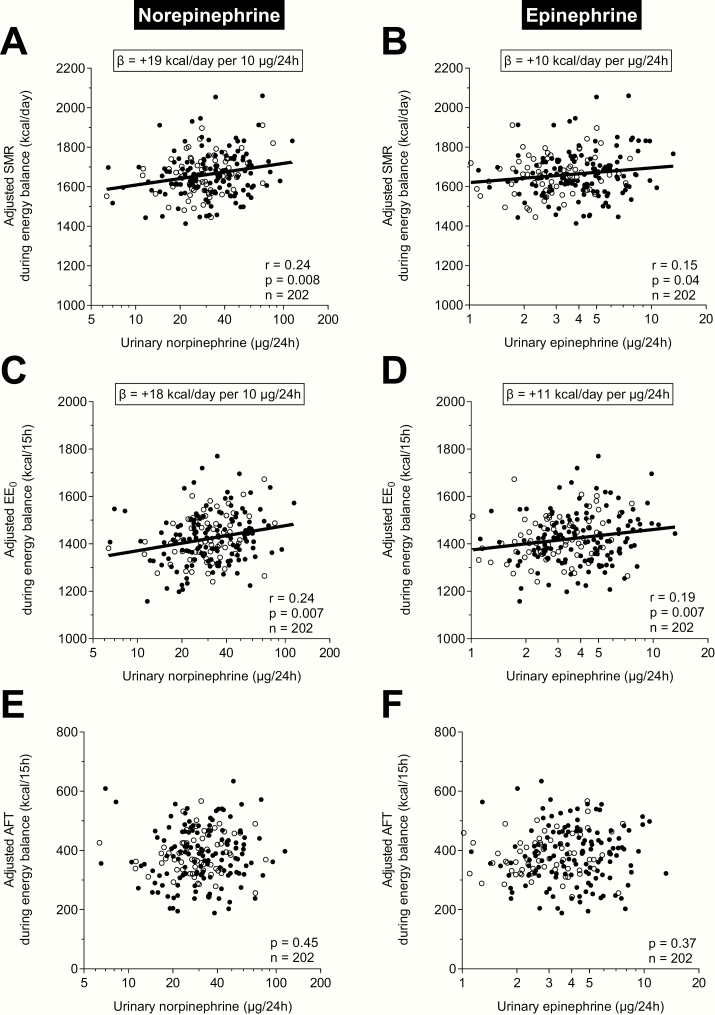

Sleeping metabolic rate.

We further analyzed the components of 24EE to elucidate which components may explain the positive associations between catecholamines and 24EE. We first analyzed the association between catecholamines and SMR. We found that norepinephrine (partial r = 0.24, P = .008, Fig. 3A) and epinephrine (partial r = 0.15, P = .04, Fig. 3B) were associated with adjusted SMR in separate, univariate analyses. Similar results were obtained when adjusting for BMI instead of FM and FFM (norepinephrine: partial r = 0.19, P = .01; epinephrine: partial r = 0.17, P = .02). On average, a 2-fold greater norepinephrine excretion was associated with a greater adjusted SMR by 137 kcal/day (CI: 57-216 kcal/day), whereas a 2-fold greater epinephrine excretion was associated with a greater adjusted SMR by 90 kcal/day (CI: 6-174 kcal/day). In the multivariate analysis testing both catecholamines as independent determinants of adjusted SMR, only norepinephrine (β: +16 kcal/day per 10 μg/24h, partial r = 0.19, P = .007), not epinephrine (P = 0.25), was an independent determinant of adjusted SMR. This was further confirmed when considering the epinephrine-to-norepinephrine ratio, which was not associated with adjusted SMR (P = .32).

Figure 3.

Associations between 24-hour urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine excretion rates and components of 24-hour energy expenditure (24EE) during energy balance. Associations between urinary (A), norepinephrine and (B), epinephrine excretion rates and adjusted sleeping metabolic rate (SMR). On average, a greater urinary norepinephrine excretion rate by 10 μg/24h and a greater urinary epinephrine excretion rate by 1 μg/24h were associated with a greater adjusted SMR by 19 kcal/d (CI: 9-29 kcal/d) and 10 kcal/day (CI: 2-19 kcal/d), respectively. Associations between urinary (C), norepinephrine and (D), epinephrine excretion rates and adjusted energy expenditure in the inactive, awake state (EE0). On average, a greater urinary norepinephrine excretion rate by 10 μg/24h and a greater urinary epinephrine excretion rate by 1 μg/24h were associated with a greater adjusted EE0 by 18 kcal/d (CI: 8-27 kcal/d) and 11 kcal/d (CI: 3-20 kcal/day), respectively. Lack of associations between urinary (E), norepinephrine and (F), epinephrine excretion rates and adjusted awake-fed thermogenesis (AFT). All adjusted EE measures (SMR, EE0, and AFT) were calculated via linear regression analysis including fat-free mass (FFM), fat mass (FM), age, sex, ethnicity, calorimeter temperature, and calorimeter room as covariates after adding the respective average value calculated in the whole cohort to the residual values obtained from the respective regression model. X-axes are formatted on a logarithmic scale (log10) to account for the skewed data distribution of raw catecholamine values. Black circles denote male, white circles denote female participants.

Energy expenditure in the inactive state.

The EE0 represents the energy expended in the awake, inactive state and includes components of SMR and AFT. We found that norepinephrine (partial r = 0.24, P = .007, Fig. 3C) and epinephrine (partial r = 0.19, P = .007, Fig. 3D) were associated with adjusted EE0 in separate, univariate analyses. On average, a 2-fold greater norepinephrine excretion was associated with a greater adjusted EE0 by 132 kcal/day (CI: 56-207 kcal/day), whereas a 2-fold greater epinephrine excretion was associated with a greater adjusted EE0 by 109 kcal/day (CI: 31-188 kcal/day). In the multivariate analysis testing both catecholamines as independent determinants of adjusted EE0, only norepinephrine (β: +15 kcal/day per 10 μg/24h, partial r = 0.20, P = .01), not epinephrine (P = 0.09), was an independent determinant of adjusted EE0. This was further confirmed when considering the epinephrine-to-norepinephrine ratio, which was not associated with adjusted EE0 (P = .56).

“Awake and fed” thermogenesis.

We also analyzed the association between catecholamines and AFT (a surrogate for DIT that includes the energy cost of arousal). However, neither catecholamine measure was associated with AFT (both P = .37, Figs. 3E and 3F, respectively). The ratio of epinephrine to norepinephrine was also not correlated with adjusted AFT (P = .58).

Spontaneous physical activity.

We also analyzed the associations between catecholamines and adjusted SPA inside the respiratory chamber and found that only epinephrine was associated with adjusted SPA (r = 0.19, P = .008), whereas norepinephrine showed no association (P = .96) (24). On average, a greater epinephrine excretion by 2-fold or 1 μg/24h was associated with a greater adjusted SPA by 4.0% (CI: 1.1%-7.0%) or 0.5% (CI: 0.2%-0.8%), respectively. In line with these results, we found that only epinephrine (P = .004), not norepinephrine (P = .30), was an independent predictor of adjusted SPA. This was further confirmed when considering the ratio of epinephrine to norepinephrine, which was now a significant determinant of adjusted SPA (r = 0.17, P = .03).

Discussion

In a cohort including 202 healthy participants, we demonstrated that epinephrine and norepinephrine were determinants of 24EE, nonactivity energy expenditure (EE0), and SMR, whereas only epinephrine was associated with SPA during carefully controlled conditions of energy balance and after adjustment for the known determinants of energy expenditure. In statistical models in which both catecholamines were included, only norepinephrine was an independent determinant of 24EE, EE0, and SMR. Neither catecholamine was associated with AFT, a surrogate for diet-induced thermogenesis.

Norepinephrine was higher in participants with greater adiposity, whereas epinephrine was lower. This “dissociation” of central sympathetic and sympathoadrenal activity in obesity was previously reported (41–43). However, after further adjustment for age, sex, ethnicity, fasting glucose, and insulin, only insulin was still associated with greater norepinephrine. This is in line with the hypothesis from Landsberg, who proposed that insulin increases in adiposity as a compensatory mechanism to limit weight gain by increasing sympathetic activity and consequently metabolic rate (44).

Urinary norepinephrine is a metabolic determinant of 24-hour, resting, and sleeping metabolic rate

Our results show that, after accounting for body composition, age, sex, ethnicity, and calorimeter parameters, epinephrine and norepinephrine both were determinants of 24EE, SMR, and EE0 when analyzed separately. However, only norepinephrine was an independent determinant of these EE measures because it remained a significant determinant of EE when both catecholamines were introduced into the multivariable regression models. In addition, the epinephrine-to-norepinephrine ratio showed no significant association with all 3 EE measures, suggesting that the results for epinephrine are driven by its association with norepinephrine (24).

The effect of norepinephrine on 24EE arises from its association with SMR, a surrogate for resting metabolic rate (RMR), which is defined as the resting, postabsorptive state. On average, RMR accounts for 70% to 80% of the daily calories spent, and thus is a major contributor to 24EE (45). Previous studies already found in various settings that norepinephrine (but not epinephrine) is a metabolic determinant of RMR (2, 22, 46). Our study extends these findings to a larger and more heterogeneous, ethnically diverse population.

A 10 μg/24h greater urinary norepinephrine excretion rate was associated with a greater 24EE by 27 kcal/day and a greater SMR by 19 kcal/day. Norepinephrine explained 1.1% of the additional variance, which is admittedly a small effect but similar to what Toubro et al previously reported (2). These authors argued that the weak association could be due to the measurement of plasma catecholamines at only one time point (after exiting the calorimeter) and advocated the measurement of catecholamines over 24 hours to obtain a better estimate of SNS activity during 24 hours of energy balance. This was performed by Saad and colleagues, who found a positive association between urinary norepinephrine (but not epinephrine) excretion rate and 24EE measures in a cohort of white men, whereas this association was not found in Native American men (22). In the present study, we confirm and extend the associations between catecholamine excretion rate and EE measures to women and across different ethnicities including Native Americans. Yet, the effect of catecholamines, although significant, contributes to only a small part of the interindividual variance in 24EE, at least in healthy, unstressed participants during energy-balance conditions.

The physiological mechanisms by which norepinephrine modulates EE is likely by its effects on α 1-receptors and β 1-receptors throughout the body by increasing blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output (47). Likewise, norepinephrine may modulate EE via its binding to β 3-adrenergic receptors in the membrane of brown adipocytes, where it increases fatty acid β-oxidation and heat production (48). We also found that norepinephrine was an independent determinant of protein oxidation rate, which indicates that it might increase EE via protein catabolism resulting in enhanced gluconeogenesis (49). However, norepinephrine is also associated with anabolic actions on skeletal muscle protein metabolism (50).

Urinary catecholamines are not associated with diet-induced thermogenesis

Neither urinary norepinephrine nor epinephrine were associated with adjusted AFT (a surrogate measure of DIT). However, studies in rodents suggest that greater sympathetic activity does increase DIT (13, 14, 51). In humans the results are mixed, with some studies (including ours) failing to show a correlation between catecholamines and DIT (5, 52–54) whereas others did demonstrate an association (54–56). These divergent findings might be due to different measurement techniques (catecholamine appearance rate vs 24-hour urinary catecholamine excretion), assessment of DIT (eg, AFT is the sum of DIT plus the cost of being awake), or provided energy intake (most studies measured DIT after 1 single meal, whereas we measured DIT over 24 hours that comprised 4 separate meals). Furthermore, it might be that only “nutrient stress” like overfeeding leads to sufficient SNS activation to significantly increase metabolic rate and DIT (14, 56).

Urinary epinephrine is associated with greater spontaneous physical activity

A greater 24-hour urinary epinephrine excretion was associated with greater adjusted SPA. This is supported by other studies that show that higher SNS activity was associated with increased physical activity in Native American and white men (37). Interestingly, higher SPA measured while residing in the respiratory chamber also predicted less future weight gain (57). We speculate that the higher epinephrine levels during energy balance are a consequence rather than a cause of higher SPA in our present cohort as increased physical activity was shown to be causal for the increase in epinephrine secretion (58, 59).

Limitations

Our study has limitations. This is a cross-sectional analysis, thus causality of the associations between catecholamines and EE measures could not be determined, although treatment with catecholamines was previously shown to increase metabolic rate (14). Also, individuals of Native American descent are overrepresented in our cohort (41%), which may have biased our findings because SNS activity appears to be a stronger determinant of energy expenditure in whites than in Native Americans (22). However, we adjusted all EE measures by ethnicity to account for this overrepresentation. Further, the measurement of urinary catecholamines is not a complete indicator of SNS activity because significant amounts of monoamines filtered at the glomerulus do not reach the final urine (60), and the kidneys contain the enzymes necessary to synthesize most neurotransmitters, which may distort the results (61). Lastly, urinary catecholamines are spillover measures and may not represent the “real” end-organ effects of the SNS.

Conclusion

Both catecholamines were determinants of 24-hour energy expenditure, resting energy expenditure, and SMR. However, these associations were driven by norepinephrine rather than epinephrine. Although the effects of catecholamines on energy expenditure were admittedly small, they were measured in nonstressed participants during energy-balance conditions. Stressful situations like cold exposure or overeating might increase catecholamine levels to a greater extent and ultimately have a greater impact on energy expenditure during these conditions, thus representing an important metabolic factor for the susceptibility to weight gain.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the dietary, nursing, and technical staff of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Unit in Phoenix, Arizona, for their assistance. Most of all, the authors thank the volunteers for their participation in this study.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (Grants DK069029-11, DK069091-12, DK075034-09). P.P. was supported by the program “Rita Levi Montalcini for Young Researchers” from the Italian Minister of Education and Research.

Clinical Trial Information: Clinical trial registration numbers NCT00856609, NCT00523627, NCT00687115, and NCT00342732.

Author Contributions: T.H. carried out the initial analyses, interpreted the results, wrote the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. T.A. carried out the initial analyses, interpreted the results, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. A.B. carried out the initial analyses, interpreted the results, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. S.B.V. interpreted the results and approved the final manuscript as submitted. J.K. interpreted the results and approved the final manuscript as submitted. P.P. designed the study, interpreted the results, edited the text and approved the final manuscript as submitted. T.H. and P.P. are the guarantors of this work, and as such had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 24EE

24-h energy expenditure

- 24RQ

24-h respiratory quotient

- AFT

awake-fed thermogenesis

- AUC

area under the curve

- BMI

body mass index

- DIT

diet-induced thermogenesis

- EE

energy expenditure

- EE0

energy expenditure in the inactive, awake state

- FFM

fat-free mass

- FM

fat mass

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- PFAT

percentage fat

- SMR

sleeping metabolic rate

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- SPA

spontaneous physical activity

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Weyer C, Snitker S, Rising R, Bogardus C, Ravussin E. Determinants of energy expenditure and fuel utilization in man: effects of body composition, age, sex, ethnicity and glucose tolerance in 916 subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(7):715–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toubro S, Sørensen TI, Rønn B, Christensen NJ, Astrup A. Twenty-four-hour energy expenditure: the role of body composition, thyroid status, sympathetic activity, and family membership. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(7):2670–2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Astrup A, Buemann B, Christensen NJ, et al. The contribution of body composition, substrates, and hormones to the variability in energy expenditure and substrate utilization in premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74(2):279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lam YY, Redman LM, Smith SR, et al. Determinants of sedentary 24-h energy expenditure: equations for energy prescription and adjustment in a respiratory chamber. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(4):834–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schwartz RS, Jaeger LF, Veith RC. The thermic effect of feeding in older men: the importance of the sympathetic nervous system. Metabolism. 1990;39(7):733–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spraul M, Ravussin E, Fontvieille AM, Rising R, Larson DE, Anderson EA. Reduced sympathetic nervous activity. A potential mechanism predisposing to body weight gain. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(4):1730–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tataranni PA, Larson DE, Snitker S, Young JB, Flatt JP, Ravussin E. Effects of glucocorticoids on energy metabolism and food intake in humans. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(2 Pt 1):E317–E325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Q, Zhang M, Ning G, et al. Brown adipose tissue in humans is activated by elevated plasma catecholamines levels and is inversely related to central obesity. PloS One. 2011;6(6):e21006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tank AW, Lee Wong D. Peripheral and central effects of circulating catecholamines. Compr Physiol. 2015;5(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Molinoff PB, Axelrod J. Biochemistry of catecholamines. Annu Rev Biochem. 1971;40:465–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palkovits M. Sympathoadrenal system: neural arm of the stress response. In: Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Ltd; 2010: 679–684. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mathar I, Vennekens R, Meissner M, et al. Increased catecholamine secretion contributes to hypertension in TRPM4-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(9):3267–3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Landsberg L. Feast or famine: the sympathetic nervous system response to nutrient intake. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26(4-6):497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Landsberg L, Young JB. The role of the sympathoadrenal system in modulating energy expenditure. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;13(3):475–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young JB, Saville E, Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ, Landsberg L. Effect of diet and cold exposure on norepinephrine turnover in brown adipose tissue of the rat. J Clin Invest. 1982;69(5):1061–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Macdonald IA, Stock MJ. Influence of norepinephrine and fasting on the oxygen consumption of genetically-obese mice. Nutr Metab. 1979;23(4):250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Macdonald IA, Bennett T, Fellows IW. Catecholamines and the control of metabolism in man. Clin Sci (Lond). 1985;68(6):613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Webber J, Macdonald IA. Metabolic actions of catecholamines in man. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;7(2):393–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Billes SK, Cowley MA. Catecholamine reuptake inhibition causes weight loss by increasing locomotor activity and thermogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(6):1287–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakagawa M, Shinozawa Y, Ando N, Aikawa N, Kitajima M. The effects of dopamine infusion on the postoperative energy expenditure, metabolism, and catecholamine levels of patients after esophagectomy. Surg Today. 1994;24(8):688–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kurpad AV, Khan K, Calder AG, Elia M. Muscle and whole body metabolism after norepinephrine. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(6 Pt 1):E877–E884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saad MF, Alger SA, Zurlo F, Young JB, Bogardus C, Ravussin E. Ethnic differences in sympathetic nervous system-mediated energy expenditure. Am J Physiol. 1991;261(6 Pt 1):E789–E794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kennedy BP, Rao F, Botiglieri T, et al. Contributions of the sympathetic nervous system, glutathione, body mass and gender to blood pressure increase with normal aging: influence of heredity. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19(12):951–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hollstein T, Basolo A, Ando T, Votruba SB, Krakoff J, Piaggi P. Supplemental Material - Urinary norepinephrine is a metabolic determinant of 24-hour energy expenditure and sleeping metabolic rate in adult humans. Harvard Dataverse, V2. 2020. 10.7910/DVN/JAVHZY [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pannacciulli N, Salbe AD, Ortega E, Venti CA, Bogardus C, Krakoff J. The 24-h carbohydrate oxidation rate in a human respiratory chamber predicts ad libitum food intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):625–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miller DS, Mumford P. Gluttony. 1. An experimental study of overeating low- or high-protein diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 1967;20(11):1212–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American Diabetes Association. (2) Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl:S8–S16. https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/38/Supplement_1/S8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reinhardt M, Piaggi P, DeMers B, Trinidad C, Krakoff J. Cross calibration of two dual‐energy X‐ray densitometers and comparison of visceral adipose tissue measurements by iDXA and MRI. Obesity. 2017;25(2):332–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thearle MS, Pannacciulli N, Bonfiglio S, Pacak K, Krakoff J. Extent and determinants of thermogenic responses to 24 hours of fasting, energy balance, and five different overfeeding diets in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(7):2791–2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jéquier E, Acheson K, Schutz Y. Assessment of energy expenditure and fuel utilization in man. Annu Rev Nutr. 1987;7:187–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Piaggi P, Krakoff J, Bogardus C, Thearle MS. Lower “awake and fed thermogenesis” predicts future weight gain in subjects with abdominal adiposity. Diabetes. 2013;62(12):4043–4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schutz Y, Bessard T, Jéquier E. Diet-induced thermogenesis measured over a whole day in obese and nonobese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40(3):542–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schutz Y, Ravussin E, Diethelm R, Jequier E. Spontaneous physical activity measured by radar in obese and control subject studied in a respiration chamber. Int J Obes. 1982;6(1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moleman P, Tulen JH, Blankestijn PJ, Man in ‘t Veld AJ, Boomsma F. Urinary excretion of catecholamines and their metabolites in relation to circulating catecholamines. Six-hour infusion of epinephrine and norepinephrine in healthy volunteers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(7):568–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hernandez FC, Sánchez M, Alvarez A, et al. A five-year report on experience in the detection of pheochromocytoma. Clin Biochem. 2000;33(8):649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grouzmann E, Lamine F. Determination of catecholamines in plasma and urine. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(5):713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Christin L, O’Connell M, Bogardus C, Danforth E Jr, Ravussin E. Norepinephrine turnover and energy expenditure in Pima Indian and white men. Metabolism. 1993;42(6):723–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lenders JW, Keiser HR, Goldstein DS, et al. Plasma metanephrines in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(2):101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Singh RJ, Grebe SK, Yue B, et al. Precisely wrong? Urinary fractionated metanephrines and peer-based laboratory proficiency testing. Clin Chem. 2005;51(2):472–3; discussion 473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Piaggi P, Thearle MS, Bogardus C, Krakoff J. Lower energy expenditure predicts long-term increases in weight and fat mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(4):E703–E707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee ZS, Critchley JA, Tomlinson B, et al. Urinary epinephrine and norepinephrine interrelations with obesity, insulin, and the metabolic syndrome in Hong Kong Chinese. Metabolism. 2001;50(2):135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Troisi RJ, Weiss ST, Parker DR, Sparrow D, Young JB, Landsberg L. Relation of obesity and diet to sympathetic nervous system activity. Hypertension. 1991;17(5):669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ward KD, Sparrow D, Landsberg L, Young JB, Vokonas PS, Weiss ST. The relationship of epinephrine excretion to serum lipid levels: the Normative Aging Study. Metabolism. 1994;43(4):509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Landsberg L. Diet, obesity and hypertension: an hypothesis involving insulin, the sympathetic nervous system, and adaptive thermogenesis. Q J Med. 1986;61(236):1081–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ekelund U, Brage S, Franks PW, Hennings S, Emms S, Wareham NJ. Physical activity energy expenditure predicts progression toward the metabolic syndrome independently of aerobic fitness in middle-aged healthy Caucasians: the Medical Research Council Ely Study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1195–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zauner C, Schneeweiss B, Kranz A, et al. Resting energy expenditure in short-term starvation is increased as a result of an increase in serum norepinephrine. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(6):1511–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Molinoff PB. Alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes properties, distribution and regulation. Drugs. 1984;28(Suppl 2:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(1):277–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barth E, Albuszies G, Baumgart K, et al. Glucose metabolism and catecholamines. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9 Suppl):S508–S518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Navegantes LC, Migliorini RH, do Carmo Kettelhut I. Adrenergic control of protein metabolism in skeletal muscle. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2002;5(3):281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Welle S. Sympathetic nervous system response to intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62(5 Suppl):1118S–1122S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marques-Lopes I, Forga L, Martínez JA. Thermogenesis induced by a high-carbohydrate meal in fasted lean and overweight young men: insulin, body fat, and sympathetic nervous system involvement. Nutrition. 2003;19(1):25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tappy L. Thermic effect of food and sympathetic nervous system activity in humans. Reprod Nutr Dev. 1996;36(4):391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schwartz RS, Jaeger LF, Silberstein S, Veith RC. Sympathetic nervous system activity and the thermic effect of feeding in man. Int J Obes. 1987;11(2):141–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schwartz RS, Jaeger LF, Veith RC. Effect of clonidine on the thermic effect of feeding in humans. Am J Physiol. 1988;254(1 Pt 2):R90–R94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wijers SL, Saris WH, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. Individual thermogenic responses to mild cold and overfeeding are closely related. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4299–4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zurlo F, Ferraro RT, Fontvielle AM, Rising R, Bogardus C, Ravussin E. Spontaneous physical activity and obesity: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in Pima Indians. Am J Physiol. 1992;263(2 Pt 1):E296–E300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kjaer M, Galbo H. Effect of physical training on the capacity to secrete epinephrine. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1988;64(1):11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zouhal H, Jacob C, Delamarche P, Gratas-Delamarche A. Catecholamines and the effects of exercise, training and gender. Sports Med. 2008;38(5):401–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hinz M, Stein A, Trachte G, Uncini T. Neurotransmitter testing of the urine: a comprehensive analysis. Open Access J Urol. 2010;2:177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 61. Alts J, Alts D, Bull M.. Urinary Neurotransmitter Testing: Myths and Misconceptions. Osceola, WI: NeuroScience Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]