Abstract

-

»

The glenohumeral (GH) joint ranks third on the list of the large joints that are most commonly affected by osteoarthritis, after the knee and the hip.

-

»

General nonsurgical modalities, including changes in daily activities, physical therapy, pharmacotherapy, and corticosteroid injections, constitute the mainstay of treatment. Most of these options, however, have shown moderate and short-term effectiveness.

-

»

Arthroplasty techniques have proven to be successful for elderly patients. Nevertheless, replacement options are not optimal for younger patients because their functional demands are higher and prostheses have a finite life span.

-

»

This has led to the search for new nonoperative treatment options to target this subgroup of patients. It has been suggested that orthobiologic therapies, including platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and cell therapies, present great promise and opportunity for the treatment of GH osteoarthritis.

-

»

Despite the promising results that have been shown by cell therapies and PRP for treating degenerative joint conditions, additional studies are needed to provide more definitive conclusions.

With an estimated prevalence of 10% in men and 18% in women who are over 60 years of age, osteoarthritis constitutes the most widespread musculoskeletal disease in the world1. The glenohumeral (GH) joint ranks third on the list of the most commonly affected large joints after the knee and the hip2. Nonetheless, the number of studies addressing the progression of arthritic changes in the shoulder are scarce. Leyland et al. conducted a cohort study that followed the progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis for 15 years; they found the annual rate of disease progression to be 2.8%3. Whether the shoulder follows a similar path or not remains unclear. Unfortunately, to date, no reported interventions that are capable of reversing or slowing the natural progression of early osteoarthritis have been found.

In order to reduce pain, enhance functionality, and potentially minimize disease progression, a nonoperative management approach should be adopted before considering other, invasive alternatives4,5. Evidence supporting the use of nonarthroplasty treatments for GH osteoarthritis is scarce compared with the guidelines provided by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in relation to the use of nonarthroplasty treatments for knee osteoarthritis, which strongly recommend the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as well as low-impact rehabilitation, wellness activity, weight loss, and education6. On the other hand, for the initial treatment of GH osteoarthritis, the AAOS has failed to either recommend or discourage pharmacotherapy or injectable corticosteroids, and has instead offered a “limited” recommendation in relation to the use of injectable viscosupplementation7. Nonetheless, general nonsurgical modalities, including changes in daily activities and sports participation, pharmacotherapy, intra-articular injections, and physical therapy, remain the mainstay of nonoperative management4,5. Apart from their potential to improve patient symptoms, these approaches have the advantages of being inexpensive and posing a minimal risk. When disease and symptoms progress, current shoulder arthroplasty techniques have been shown to be reproducibly successful in elderly patients with GH osteoarthritis who have not had success with nonoperative treatment. Replacement options fail to be so auspicious in younger patients who present with osteoarthritis4,5. In this sense, prosthetic replacement may be precluded by the superior demands for activity and the higher functional expectations from young patients8. Moreover, the possible occurrence of adverse outcomes as well as the limited life span of a prosthesis have led to the search for new nonoperative treatment options to target, especially for this subgroup of patients8.

Given some early success in the use of autologous orthobiologic therapies for joints such as the knee, we review the role for similar treatments in the GH joint3,5. In this context, orthobiologic therapies present great promise and opportunity9. For example, different formulations obtained through density separation (centrifugation) of blood (platelet-rich plasma [PRP]) and bone marrow (bone marrow aspirate concentrate [BMAC]) appear as promising alternatives because of their ability to modulate inflammation10. Additionally, cells obtained from adipose tissue have been proposed11. The multiple cytokines, anti-inflammatory factors, and bioactive molecules present in these preparations constitute vital regulators in a microenvironment with a complex healing process; thus, they may help to treat degenerative joint conditions12,13. However, there are multiple challenges and remaining questions regarding the use, safety, and efficacy of orthobiologics.

This narrative review provides a comprehensive analysis of the pathophysiology of GH osteoarthritis and the basic science underlying the potential use of injectable autologous PRP and clinically available cell therapies that are targeted for its treatment. Furthermore, a complete description of the recommended techniques for the application and a summary of the existing clinical evidence supporting the use of orthobiologics in shoulder osteoarthritis are provided.

Etiology of GH Osteoarthritis

GH osteoarthritis can be broadly classified into primary and secondary osteoarthritis. The former represents about 90% of the cases; it usually affects patients who are ≥60 years old and is characterized by damage to the articular cartilage and dense subchondral bone, osteophytes, posterior glenoid erosion, and posterior displacement of the humeral head, without prior injury or surgery14. Various risk factors have been associated with the development of shoulder osteoarthritis, including obesity, injuries resulting from shoulder overuse, occupations requiring excessive use of the upper limbs, the practice of overhead sports, and a history of previous trauma or dislocation14,15.

Patients who are <60 years old usually present with secondary causes of GH osteoarthritis4,15. Secondary osteoarthritis may result from GH dislocations and subluxations through osteochondral fractures and subchondral bone injury involving the glenoid and the humeral head4. Hovelius and Saeboe conducted a study that followed 223 shoulders for 25 years after primary anterior dislocation16. Of the total number of shoulders that did not experience recurrence, 18% had moderate-to-severe arthropathy. In the patients who experienced recurrent dislocations, osteoarthritis developed in 39% of those who had been treated nonoperatively and in 26% of those who had surgically stabilized shoulders16.

Atraumatic osteonecrosis also can lead to secondary osteoarthritis. It is worth noting that, after the hip, the proximal aspect of the humerus ranks second as the most commonly affected site in the body in terms of osteonecrosis17. Multiple risk factors have been associated with proximal humeral osteonecrosis, including the use of systemic corticosteroids, chemotherapy/radiation, alcohol abuse, hematopoietic diseases, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and treatment with cytotoxic drugs18.

Proximal humeral or glenoid malunion also can trigger secondary osteoarthritis due to aberrant joint biomechanics or posttraumatic osteonecrosis19,20.

During surgical intervention about the shoulder, iatrogenic causes can result in osteoarthritic sequelae, including capsulorrhaphy arthropathy, which consists of the rapid posterior chondral wear that is caused by anterior capsule overtightening and the resultant compressive joint forces and loss of external rotation21. Iatrogenic postarthroscopic chondrolysis also has been described and can lead to early GH osteoarthritis in young patients22. This condition has been related to the use of intra-articular pain pumps that deliver local anesthetics22, nonabsorbable prominent suture anchors, and thermal devices22-24.

Finally, other possible but less common causes of secondary shoulder osteoarthritis include inflammatory arthropathy25, radiofrequency/thermal capsulorrhaphy26, and sequelae from a previously infected joint27.

Physiopathology of Shoulder Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a complex multifactorial condition. Its pathogenesis is associated with the critical roles played by cartilage, subchondral bone, and synovium1. Subchondral bone changes are correlated with articular cartilage degeneration. In this sense, bone volume and trabecular thickness increase as cartilage degeneration progresses28,29. With osteoarthritis, the bone becomes stiffer. This may reduce its ability to absorb impact loads, thus causing more cartilage stress28,29.

Type-II collagen, the main structural protein of cartilage, constitutes a meshwork that is stabilized by other collagen types and noncollagenous proteins, including the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein. In addition, it provides cartilage with tensile strength30. Within this framework, proteoglycans bring water to the cartilage, thus providing compressive resistance30. Cartilage destruction in osteoarthritis is not only caused by mechanical wear. In fact, it may also be influenced by various proteases, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) such as ADAMTS (A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin motifs)-4, ADAMTS-5, and MMP-1331,32. ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5, also referred to as aggrecanases, are capable of destroying the aggrecan, which is the most common proteoglycan found in articular cartilage. It is involved in load distribution in the joints during movement and provides hydration and elasticity to cartilage tissue31,32. In turn, collagenases, particularly MMP-13, have the ability to degrade the most abundant collagen in cartilage, type-II collagen, which, as mentioned above, is responsible for its tensile strength33,34. A crucial factor involved in the development of osteoarthritis is the overexpression of MMPs31,32.

Chondrocytes synthesize and break down the matrix that is regulated by cytokines and growth factors. In arthritis, their balance may be compromised30. When they are activated, chondrocytes produce various inflammatory response proteins, including cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, as well as matrix-degrading enzymes, such as the MMPs and a disintegrin30,35. Both at early and late stages of osteoarthritis, IL-l plays a key role35. This multifunctional proinflammatory cytokine produces various effects, which include cartilage breakdown, lymphokine production, interference with growth factor activity, or reduction of the synthesis of the key matrix components such as aggrecan35. IL-1β also induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as lipid peroxidation, which have been associated with cartilage matrix degradation35. Chondrocytes produce ROS, including hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anions, and hydroxyl radicals in response to IL-1, and are capable of inducing collagen and aggrecan degradation in chondrocytes36. In addition, activated macrophages and neutrophils participating in inflammatory responses may generate ROS36. IL-1 and TNF-α stimulate nitric oxide production, a potent mediator that is produced by articular chondrocytes during inflammatory reactions by inhibiting proteoglycan synthesis, enhancing MMP production, or increasing oxidant stress to arthritis disease in joints37. NF-κB cells (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells), one of the key regulatory mechanisms involved in regulating and controlling expression of cytokines, are critical in immune function, namely inflammation38. The stimulus of NF-κB is known to lead to the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β8.

Since it stimulates proteolytic enzyme secretion from chondrocytes and synovial fibroblasts, TNF-α, an effective proinflammatory cytokine, plays a major role in inflammation and matrix degradation37. IL-1 and TNF-α both induce production of IL-6, and higher levels of these cytokines might lead to the development of osteoarthritis37. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) is produced as a result of inflammation and worsens the inflammatory process like arthritis37,39. Finally, patients with osteoarthritis have been found to exhibit elevated levels of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) activity in their synovial fluid. In turn, cells are triggered to form osteophytes when TGF-β is released by tissue damage and inflammation40.

PRP for Osteoarthritis: Basic Science Background

PRP consists of a sample of autologous blood with platelet concentrations above baseline values, which has been produced through the separation of whole blood by centrifugation13. PRP is considered to be minimally manipulated and falls under the scope of section 361 (Public Health Service Act, 21 Code of Federal Regulation 1271) of minimally manipulated therapies. In addition to platelets, and depending on the preparation protocol, PRP contains varying levels of blood components such as leukocytes (namely monocytes and neutrophils) and red blood cells. Hence, platelet, leukocyte, and red blood cell concentrations in each individual PRP preparation may vary depending on the system and the protocol that are utilized. In addition, substantial variations in blood component concentrations have been reported, even in the same patient over a 2-week period41,42. The majority of the characteristics shown by platelets are determined by the megakaryocytes from which they arise. The membrane bodies of the alpha granules are made in megakaryocytes43. However, some of the granule contents of the platelets actually are taken up from the plasma43. Specifically, the alpha granules of platelets contain numerous platelet proteins and growth factors43. During megakaryocyte development, the granule body itself is made early, before the demarcation membrane system44. Part of the granule contents, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), TGF-β, and platelet factor 4, are synthesized in the megakaryocyte and then transported to the alpha granules43. However, there are other proteins, including fibrinogen, albumin, and immunoglobulin G (IgG), that enter the alpha granules by endocytosis44.

The term “platelet-rich plasma” includes a wide spectrum of PRP preparation protocols and formulations45. Several authors have attempted to characterize and classify the various techniques available in the market in terms of preparation (centrifugation speed and use of anticoagulant), content (platelets, leukocytes, and growth factors), and applications45-48. However, no consensus has been reached thus far among experts in the field. As an example, in the last 6 years, 5 different classifications have been described45-48. Comparing the results of different studies poses a challenge since there are multiple PRP classification systems available. Therefore, it is essential to achieve a consensus among experts in the field to define a unique and standardized classification for the reporting of PRP use in future studies.

The rationale underlying the use of PRP is that growth factors are released as soon as platelets are activated, with approximately 70% of them being released within the first 10 minutes following activation49. Specifically, platelets possess biologically active growth factors inside alpha granules, which have the potential to reduce joint inflammation, decrease cartilage breakdown, and promote tissue repair50. It is believed that such elevated concentrations of growth factors, as well as bioactive proteins, may induce healing. These factors include TGF-β, insulin-like growth factor, PDGF, basic fibroblast growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor51. Chondrogenesis and stem cell proliferation have been shown to be positively affected by PRP by means of the effects of the various growth factors51. Moreover, it has been shown that PRP may increase anti-inflammatory mediators and decrease proinflammatory ones13. In turn, the transactivation of NF-κB, the critical regulator of the inflammatory process, has been found to be reduced52-54. In addition, the expression of the inflammatory enzymes cyclooxygenase 2 and 4 (COX-2 and COX-4), the disintegrins, and the MMPs are reduced by PRP52-54. Of note, most of the claimed mechanisms of action of PRP have been shown in vitro and are still to be determined in vivo.

The efficacy of PRP to treat osteoarthritis may lie in its observed ability to inhibit catabolic processes55. The MMP enzymes have the potential to cause multiple extracellular matrix protein degradation and may prevent the development of matrix formation during the healing process55. In addition, since PRP has the ability to substantially reduce MMP-3 and MMP-13 activity, matrix formation may be improved and the healing process may be facilitated56,57. As a result of these combined effects, PRP constitutes a potential injectable alternative for treating shoulder osteoarthritis. Finally, the combination of PRP and hyaluronic acid has been suggested to have a synergistic action. A study conducted by Chen et al. reported that cartilage regeneration might be promoted and osteoarthritis inflammation might be inhibited by means of a synergistic effect of hyaluronic acid combined with PRP. This, however, has yet to be proven clinically58.

Finally, there are some limitations related to PRP therapy that have not yet been resolved. Most clinical studies evaluating PRP fail to adequately report scientific details that are critical to the outcome59,60. Although expert consensus has been suggested in relation to the minimum requirements to be met when reporting clinical studies evaluating PRP, its use has not yet been universally adopted60. Furthermore, since it is challenging to compare the results among studies because of the variety of PRP classification systems, the reporting of blood-derived products in orthopaedics encounters limitations59,60. A universally accepted system for describing autologous blood preparations is likely to improve communication among researchers. Lastly, the role of some of the components present in PRP that have been shown to influence clinical outcomes in other joints have not yet been studied in the shoulder. For example, the growth factor and cytokines delivered in the target tissue are strongly influenced by leukocyte concentrations61. It has been shown that, in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis, leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP) is more effective than leukocyte-rich PRP (LR-PRP) for intra-articular injection62. However, the relation between leukocyte concentrations and functional outcomes has not been specifically studied in shoulder osteoarthritis.

PRP for Shoulder Osteoarthritis: Clinical Outcomes

Clinical studies evaluating the use of PRP injections to treat GH osteoarthritis are scarce. In 2013, Freitag and Barnard described a case report in which 3 intra-articular PRP injections (each 1 week apart) were administered to a 62-year-old woman under ultrasound guidance63. The patient experienced a reduction in the VAS (visual analogue scale) from 6 to 1, which lasted for the full follow-up period of 42 weeks. Moreover, an improvement in the DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) score also was observed, decreasing from 65 at preinjection to a score of 5 at week 4263. Lo et al. evaluated the results of using human dermal matrix allograft and PRP to perform hemiarthroplasty and biologic resurfacing of the glenoid in 55 patients64. In their study, hemiarthroplasty with biologic resurfacing led to positive midterm outcomes with satisfactory revision rates. Specifically, an average postoperative American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score of 76 was obtained, while the Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder index score was 76% and the VAS score was 2.4. Five cases (9.1%) were revised to anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty with implantation of a glenoid component. However, the lack of a control group constituted an important limitation of this study. Therefore, isolating PRP’s individual effects from those of the acellular human dermal allograft is challenging64.

To our knowledge, no other peer-reviewed studies on PRP for shoulder osteoarthritis are available. However, there are studies documenting excellent results in the knee. In 2019, Han et al. evaluated 14 randomized controlled trials comparing PRP with hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis. A total of 1,314 patients were included65. According to that meta-analysis, PRP injections were more effective in reducing pain than hyaluronic acid injections in patients with knee osteoarthritis at 6 and 12 months of follow-up with use of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score and the VAS pain score. In addition, the PRP group exhibited better functional improvement, as shown by the WOMAC function score at 3, 6, and 12 months65.

Interestingly, the combination of PRP and hyaluronic acid has been reported to have a potential synergistic effect in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis66. Since PRP and hyaluronic acid have different biologic mechanisms, their combination may help to control the delivery and presentation of signaling molecules66. In a recent study, hyaluronic acid combined with PRP significantly reduced pain and functional limitation at 1 year post-treatment (p < 0.05) compared with hyaluronic acid alone67. This is an interesting finding that could be useful for the management of shoulder osteoarthritis. Finally, the number of injections that should be applied has sparked controversy. A randomized prospective study recently conducted by Kavadar et al. aimed at investigating how many PRP injections (1, 2, or 3) administered at 2-week intervals constituted the most effective approach to treat moderate knee osteoarthritis. The authors concluded that 2 injections were the minimum required for successfully treating the symptoms (p < 0.001)68.

In conclusion, despite the fact that the basic science rationale supports the use of PRP for degenerative joint conditions and that favorable clinical outcomes have been achieved in patients with knee osteoarthritis, the clinical effect of using PRP in patients with shoulder osteoarthritis has yet to be proved. Therefore, the need to determine the effectiveness of PRP injections and whether they should be recommended as a standard of care in treating patients with GH osteoarthritis requires additional research through reliable and sizeable randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials.

Cell Therapies for Osteoarthritis: Basic Science Background

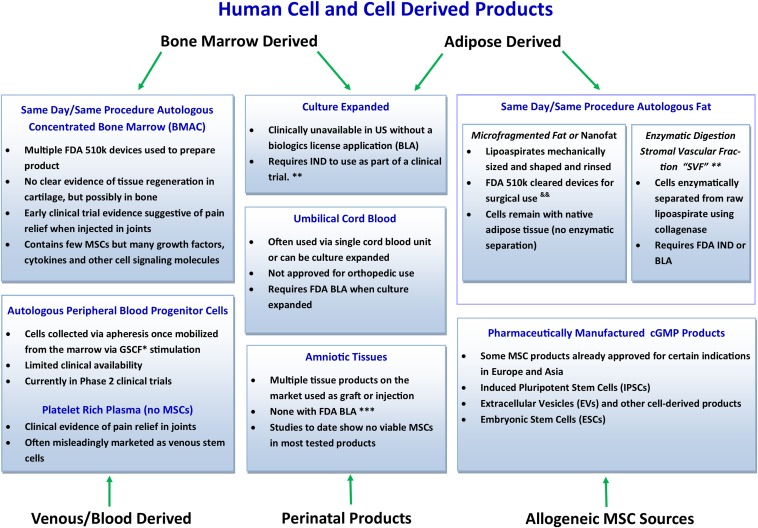

Current human cell and cell-derived products for orthopaedic use are described in Figure 1. BMAC is becoming increasingly popular as a treatment for osteoarthritis since it is included among the limited number of approaches capable of delivering progenitor cells that are currently in line with the recommendations of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and it can be used in a single-stage procedure69. Similar to PRP, BMAC requires minimal manipulation and falls under the scope of section 361 (Public Health Service Act, 21 Code of Federal Regulation 1271), which addresses minimally manipulated therapies70. Similar to PRP manufacturing from whole blood, bone marrow is first harvested and then undergoes centrifugation in order to separate cellular components into different layers. Mononucleated cells, which include white blood cells, connective tissue stem and progenitor cells, hematopoietic stem cells, and platelets, are concentrated in 1 layer, while red blood cells are concentrated in another71. Even though stem and progenitor cells account for only 0.001% to 0.01% of the total number of cells in BMAC, they are of particular interest because they can contribute to tissue regeneration directly (by differentiating damaged cell types) and indirectly (by limiting inflammation, stimulating angiogenesis, and recruiting local tissue-specific progenitors)72. Unfortunately, the reports of BMAC preparation protocols used in clinical trials related to the treatment of musculoskeletal disease are substantially inconsistent71. Piuzzi et al. performed a systematic literature review in order to assess the level of reporting in relation to BMAC preparation protocols and the BMAC composition that was used in the treatment of musculoskeletal diseases in published clinical studies71. The authors reported that most of the studies failed to provide enough information to allow the protocol to be reproduced and that quantitative metrics of the BMAC final product composition were only provided in 30% of the studies71.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual representation of current human cell and cell-derived products for orthopaedic use. *GCFS = granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. **Limited access worldwide, although some options are available in countries with little/no regulation. &&Practice in the United States requires adherence to minimal manipulation, not more than rinsing, sizing, and shaping, as outlined in the U.S. FDA Same Surgical Procedure Exception (SSPE). ***Multiple devices are available that utilize enzymatic digestion of SVF cells from adipocytes. Considered by the FDA to be more than minimal manipulation and thus outside the scope of SSPE; would require FDA IND or BLA to comply with current U.S. regulatory framework. BMAC = bone marrow aspirate concentrate, FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration, MSCs = mesenchymal stem cells, IND = Investigational New Drug, and cGMP = current good manufacturing process.

The mechanisms by which BMAC might regulate inflammatory processes are not yet fully understood. On one hand, BMAC contains higher levels of IL-1 receptor antagonist and IL-1β. These growth factors play key roles in regeneration through immune response modulation (inflammation reduction)12,13. On the other hand, the high concentration of leukocytes in BMAC may result in more inflammatory symptoms after the injection73. Furthermore, other BMAC cell types may play a therapeutic role. When analyzing the use of stem cells for degenerative conditions, it is critical to understand how age-related changes may affect stem cell function. Cassano et al. evaluated the effects of aging on the therapeutic potential of stem cells and showed that despite their promising short-term effects in degenerative orthopaedic pathologies, stem cell therapies do not seem to be capable of reversing age-related tissue degeneration73. Since PRP has been previously demonstrated to have therapeutic effects, BMAC’s beneficial effects also may be substantially influenced by PRP-released factors74,75.

Finally, adipose tissue is another major source of cells, considering that it can be easily accessed and harvested and that few complications have been reported with the procedure13,76. Adipose-derived therapies can be divided into 2 types: minimally manipulated (micronized fat) and more than minimally manipulated (adipose-derived stem cells [ADSCs]). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) that are derived from adipose tissue are known as adipose-ADSCs. ADSCs have gained popularity during the last decade because they are abundant and easy to access and because they have a comparable regenerative capability compared with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs)11. The major source of ADSCs is the abdominal fat pad, which can be harvested via liposuction in lipoaspirate form11,77. In order to digest the extracellular matrix, collagenase is added once the fat particles have been isolated. Following chemical disruption, the adipose sample is centrifuged for purification11,77. After centrifugation, cells are resuspended in culture media, plated in flasks, and incubated for 24 to 48 hours77. The multiple molecules that are secreted by ADSCs have proved to be key factors in tissue regeneration and anti-inflammatory effects13,78,79. ADSCs require a 2-step procedure before administration, including adipose harvest. In addition, they are generally considered pharmaceutical products that currently require strict clinical trials and regulatory approval72. Burrow et al. demonstrated that adipose cells possess an enhanced proliferative capacity and are capable of retaining multipotency longer than donor-matched marrow MSCs during expansion76. Along with the anti-inflammatory effects, ADSCs secrete various critical molecules involved in tissue regeneration, including collagens and collagen maturation enzymes, matricellular proteins, MMPs, and macrophage-colony stimulating factor, which may affect the metabolism of the extracellular matrix in osteoarthritic cartilage. This may constitute an advantage for osteoarthritic cartilage since homeostasis is restored between MMPs and the tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs)78,79.

Cell Therapies for Shoulder Osteoarthritis: Clinical Outcomes

Clinical evidence regarding the use of the BMAC injection to treat GH osteoarthritis is scarce. Centeno et al. published the longest series of patients who underwent treatment with autologous bone marrow concentrate in order to treat shoulder rotator cuff tears and osteoarthritis. From a total of 115 patients, 34 (29.6%) were diagnosed with osteoarthritis alone80. In order to guide the placement of the intra-articular needle for the BMAC injection, ultrasound or fluoroscopy was used. The assessment of the clinical outcomes was performed serially over time, using the numeric pain scale (NPS)81, the DASH score, and a subjective improvement rating scale. Specifically in the patients belonging to the osteoarthritis subgroup, a significant improvement was observed in the 3 outcome scores (p < 0.05)81.

Striano et al. conducted a study to evaluate 18 patients with osteoarthritis and refractory shoulder pain who were treated with microfragmented adipose tissue82. Significant improvement was observed at the 1-year follow-up in the NPS and the ASES scores: the average improvement that was registered in the NPS went from 7.5 to 3.6 (p < 0.001), and the average improvement in the ASES score went from 33.7 to 69.2 at 1 year (p < 0.001). There were no reports indicating any postprocedural complications or serious adverse events. A limitation of this study was that 75% of the patients had a concomitant partial or full-thickness rotator cuff tear. Therefore, it is impossible to know if the original cause of the pain was the osteoarthritis or the tendon tear.

It is important to highlight that although acromioclavicular (AC) joint osteoarthritis is a common cause of shoulder pain that is associated with GH osteoarthritis, it is still an underdiagnosed condition. Freitag et al. conducted the first case report evaluating the use of MSC therapy to treat AC joint arthritis83. An autologous ADSC preparation was used as part of MSC therapy to treat a 43-year-old patient with painful AC joint osteoarthritis. Both pain and functional improvements were reported by the patient as assessed by the DASH score and the NPS. As shown in the images taken at 12 months, structural improvement was observed, with a reduction in subchondral edema, subchondral cysts, and synovitis83.

The number of studies on the use of cell-based therapies, especially autologous BMAC therapy, to treat symptomatic knee osteoarthritis recently has grown69,84-86. The currently available studies comparing BMAC injections with hyaluronic acid injections or placebo controls for knee osteoarthritis have shown promising results69,83,85,86. Rather than direct modification of the cartilage, immunomodulation and production of anti-inflammatory mediators constitute the claimed mechanism of action. Thus, much like a corticosteroid injection, symptomatic relief after BMAC injection may be consistent, but only temporary and without evidence of cartilage regeneration85. It should be noted that, although a potential benefit has been observed for knee osteoarthritis, this finding may not be reproducible in other joints.

Despite the promising results shown by BMAC in the treatment of degenerative joint conditions and obtaining early benefits in the treatment of GH joint osteoarthritis, it will not be possible to draw definitive conclusions until additional studies are conducted.

Finally, intra-articular injection of ADSCs also has shown favorable outcomes in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Spasovski et al. treated 9 patients with knee osteoarthritis with only 1 ADSC intra-articular injection at a concentration of 0.5 to 1.0 × 107 cells87. At 18 months of follow-up, the results revealed a substantial improvement as assessed by the Tegner and Lysholm score, the Knee Society score, and the VAS. In turn, Freitag et al. randomized 30 patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in order to divide them into 3 groups. Intra-articular ADSC therapy was given to 2 treatment groups that received either 1 injection (100 × 106 ADSCs) or 2 injections (100 × 106 ADSCs at baseline and 6 months), while the third group served as a control. At the end of the 12-month follow-up period, clinically substantial pain and functional improvements were observed in the 2 treatment groups that received ADSCs88.

Meticulous Level-I studies with properly conducted power analyses that directly compare BMAC and ADSC techniques with placebo or other therapies are necessary to further evaluate their effectiveness and safety in the care of osteoarthritis.

Overview

Evidence supporting the use of nonsurgical therapies to treat GH osteoarthritis is scarce. In addition, most of the available options have shown only partial and short-term relief of symptoms. The capacity of PRP and cell therapies to regulate the healing environment that has been demonstrated in basic science studies and the favorable clinical outcomes that have been achieved in patients with knee osteoarthritis make orthobiologic therapies a promising alternative. Although the few clinical studies that have been developed thus far showed favorable outcomes and minimal complications, there is a need for more robust prospective randomized trials to compare PRP and cell therapies with placebo or other treatments to further evaluate their effectiveness and safety in the care of GH osteoarthritis.

Acknowledgments

Note: Portions of this work were funded through a grant from The Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Fund at Vanguard Charitable. The authors thank Charlie A. Shelton for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida

Disclosure: Portions of this work were funded through a grant from The Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Fund at Vanguard Charitable. The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSREV/A540).

References

- 1.Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJR, Agricola R, Price AJ, Vincent TL, Weinans H, Carr AJ. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2015. July 25;386(9991):376-87. Epub 2015 Mar 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010. August;26(3):355-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leyland KM, Hart DJ, Javaid MK, Judge A, Kiran A, Soni A, Goulston LM, Cooper C, Spector TD, Arden NK. The natural history of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a fourteen-year population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012. July;64(7):2243-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saltzman BM, Leroux TS, Verma NN, Romeo AA. Glenohumeral osteoarthritis in the young patient. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018. September 1;26(17):e361-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansok CB, Muh SJ. Optimal management of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. Orthop Res Rev. 2018. February 23;10:9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GA. AAOS Clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(9):577-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, Freehill MQ, Stanwood W, Wiater JM, Watters WC, 3rd, Goldberg MJ, Keith M, Turkelson CM, Wies JL, Anderson S, Boyer K, Raymond L, Sluka P; American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010. June;18(6):375-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberson TA, Bentley JC, Griscom JT, Kissenberth MJ, Tolan SJ, Hawkins RJ, Tokish JM. Outcomes of total shoulder arthroplasty in patients younger than 65 years: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017. July;26(7):1298-306. Epub 2017 Feb 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piuzzi NS, Dominici M, Long M, Pascual-Garrido C, Rodeo S, Huard J, Guicheux J, McFarland R, Goodrich LR, Maddens S, Robey PG, Bauer TW, Barrett J, Barry F, Karli D, Chu CR, Weiss DJ, Martin I, Jorgensen C, Muschler GF. Proceedings of the signature series symposium “cellular therapies for orthopaedics and musculoskeletal disease proven and unproven therapies-promise, facts and fantasy,” international society for cellular therapies, montreal, canada, may 2, 2018. Cytotherapy. 2018. November;20(11):1381-400. Epub 2018 Oct 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu CR, Rodeo S, Bhutani N, Goodrich LR, Huard J, Irrgang J, LaPrade RF, Lattermann C, Lu Y, Mandelbaum B, Mao J, McIntyre L, Mishra A, Muschler GF, Piuzzi NS, Potter H, Spindler K, Tokish JM, Tuan R, Zaslav K, Maloney W. Optimizing clinical use of biologics in orthopaedic surgery: consensus recommendations from the 2018 AAOS/NIH U-13 conference. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019. January 15;27(2):e50-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis SL, Duchi S, Onofrillo C, Di Bella C, Choong PFM. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the use of cartilage tissue engineering: the need for a rapid isolation procedure. Stem Cells Int. 2018. April 3;2018:8947548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlotnicki JP, Geeslin AG, Murray IR, Petrigliano FA, LaPrade RF, Mann BJ, Musahl V. Biologic treatments for sports injuries ii think tank-current concepts, future research, and barriers to advancement, part 3: articular cartilage. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016. April 15;4(4):2325967116642433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaPrade RF, Geeslin AG, Murray IR, Musahl V, Zlotnicki JP, Petrigliano F, Mann BJ. Biologic treatments for sports injuries ii think tank-current concepts, future research, and barriers to advancement, part 1: biologics overview, ligament injury, tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2016. December;44(12):3270-83. Epub 2016 Mar 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macías-Hernández SI, Morones-Alba JD, Miranda-Duarte A, Coronado-Zarco R, Soria-Bastida MLA, Nava-Bringas T, Cruz-Medina E, Olascoaga-Gómez A, Tallabs-Almazan LV, Palencia C. Glenohumeral osteoarthritis: overview, therapy, and rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2017. August;39(16):1674-82. Epub 2016 Jul 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laidlaw MS, Mahon HS, Werner BC. Etiology of shoulder arthritis in young patients. Clin Sports Med. 2018. October;37(4):505-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hovelius L, Saeboe M. Neer Award 2008: Arthropathy after primary anterior shoulder dislocation—223 shoulders prospectively followed up for twenty-five years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009. May-Jun;18(3):339-47. Epub 2009 Feb 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasan SS, Romeo AA. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002. May-Jun;11(3):281-98, 10.1067/mse.2002.124347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarris I, Weiser R, Sotereanos DG. Pathogenesis and treatment of osteonecrosis of the shoulder. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004. July;35(3):397-404: xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matis N, Ortmaier R, Moroder P, Resch H, Auffarth A. [Posttraumatic arthrosis of the glenohumeral joint. From partial resurfacing to reverse shoulder arthroplasty]. Unfallchirurg. 2015. July;118(7):592-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Oostveen DPH, Temmerman OPP, Burger BJ, van Noort A, Robinson M. Glenoid fractures: a review of pathology, classification, treatment and results. Acta Orthop Belg. 2014. March;80(1):88-98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons IM, 4th, Buoncristiani AM, Donion S, Campbell B, Smith KL, Matsen FA., 3rd The effect of total shoulder arthroplasty on self-assessed deficits in shoulder function in patients with capsulorrhaphy arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007. May-Jun;16(3)(Suppl):S19-26. Epub 2006 Oct 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiater BP, Neradilek MB, Polissar NL, Matsen FA., 3rd Risk factors for chondrolysis of the glenohumeral joint: a study of three hundred and seventy-five shoulder arthroscopic procedures in the practice of an individual community surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011. April 6;93(7):615-25. Epub 2011 Feb 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serrato JA, Jr, Fleckenstein CM, Hasan SS. Glenohumeral chondrolysis associated with use of an intra-articular pain pump delivering local anesthetics following manipulation under anesthesia: a report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011. September 7;93(17):e99: 1-8). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y, Edwards RB, 3rd, Kalscheur VL, Nho S, Cole BJ, Markel MD. Effect of bipolar radiofrequency energy on human articular cartilage. Comparison of confocal laser microscopy and light microscopy. Arthroscopy. 2001. February;17(2):117-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aydin N, Aslan L, Lehtinen J, Hamuryudan V. Current surgical treatment options of rheumatoid shoulder. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2018;14(3):200-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailie DS, Ellenbecker TS. Severe chondrolysis after shoulder arthroscopy: a case series. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009. Sep-Oct;18(5):742-7. Epub 2009 Jan 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang JJ, Piponov HI, Mass DP, Angeles JG, Shi LL. Septic arthritis of the shoulder: a comparison of treatment methods. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017. August;25(8):e175-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li B, Aspden RM. Composition and mechanical properties of cancellous bone from the femoral head of patients with osteoporosis or osteoarthritis. J Bone Miner Res. 1997. April;12(4):641-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bobinac D, Spanjol J, Zoricic S, Maric I. Changes in articular cartilage and subchondral bone histomorphometry in osteoarthritic knee joints in humans. Bone. 2003. March;32(3):284-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carballo CB, Nakagawa Y, Sekiya I, Rodeo SA. Basic science of articular cartilage. Clin Sports Med. 2017. July;36(3):413-25. Epub 2017 Apr 26, 10.1016/j.csm.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang CY, Chanalaris A, Troeberg L. ADAMTS and ADAM metalloproteinases in osteoarthritis - looking beyond the ‘usual suspects’. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017. July;25(7):1000-9. Epub 2017 Feb 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malemud CJ. Inhibition of MMPs and ADAM/ADAMTS. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019. July;165:33-40. Epub 2019 Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitale ND, Vandenbulcke F, Chisari E, Iacono F, Lovato L, Di Matteo B, Kon E. Innovative regenerative medicine in the management of knee OA: the role of autologous protein solution. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019. Jan-Feb;10(1):49-52. Epub 2018 Aug 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Troeberg L, Nagase H. Proteases involved in cartilage matrix degradation in osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012. January;1824(1):133-45. Epub 2011 Jul 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenei-Lanzl Z, Meurer A, Zaucke F. Interleukin-1β signaling in osteoarthritis - chondrocytes in focus. Cell Signal. 2019. January;53:212-23. Epub 2018 Oct 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lepetsos P, Papavassiliou AG. ROS/oxidative stress signaling in osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016. April;1862(4):576-91. Epub 2016 Jan 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kunisch E, Kinne RW, Alsalameh RJ, Alsalameh S. Pro-inflammatory IL-1beta and/or TNF-alpha up-regulate matrix metalloproteases-1 and -3 mRNA in chondrocyte subpopulations potentially pathogenic in osteoarthritis: in situ hybridization studies on a single cell level. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016. June;19(6):557-66. Epub 2014 Oct 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lepetsos P, Papavassiliou KA, Papavassiliou AG. Redox and NF-κB signaling in osteoarthritis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019. February 20;132:90-100. Epub 2018 Sep 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang T, He C. Pro-inflammatory cytokines: The link between obesity and osteoarthritis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2018. December;44:38-50. Epub 2018 Oct 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Kraan PM. The changing role of TGFβ in healthy, ageing and osteoarthritic joints. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017. March;13(3):155-63. Epub 2017 Feb 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of growth factor and platelet concentration from commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011. February;39(2):266-71. Epub 2010 Nov 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MBR, Chowaniec DM, Cote MP, Romeo AA, Bradley JP, Arciero RA, Beitzel K. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012. February 15;94(4):308-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenberg SM, Kuter DJ, Rosenberg RD. In vitro stimulation of megakaryocyte maturation by megakaryocyte stimulatory factor. J Biol Chem. 1987. March 5;262(7):3269-77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Handagama PJ, Shuman MA, Bainton DF. Incorporation of intravenously injected albumin, immunoglobulin G, and fibrinogen in guinea pig megakaryocyte granules. J Clin Invest. 1989. July;84(1):73-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeLong JM, Russell RP, Mazzocca AD. Platelet-rich plasma: the PAW classification system. Arthroscopy. 2012. July;28(7):998-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mishra A, Harmon K, Woodall J, Vieira A. Sports medicine applications of platelet rich plasma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012. June;13(7):1185-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mautner K, Malanga GA, Smith J, Shiple B, Ibrahim V, Sampson S, Bowen JE. A call for a standard classification system for future biologic research: the rationale for new PRP nomenclature. PM R. 2015. April;7(4)(Suppl):S53-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lana JFSD, Purita J, Paulus C, Huber SC, Rodrigues BL, Rodrigues AA, Santana MH, Madureira JL, Jr, Malheiros Luzo ÂC, Belangero WD, Annichino-Bizzacchi JM. Contributions for classification of platelet rich plasma - proposal of a new classification: MARSPILL. Regen Med. 2017. July;12(5):565-74. Epub 2017 Jul 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arnoczky SP, Sheibani-Rad S, Shebani-Rad S. The basic science of platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what clinicians need to know. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2013. December;21(4):180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osterman C, McCarthy MBR, Cote MP, Beitzel K, Bradley J, Polkowski G, Mazzocca AD. Platelet-rich plasma increases anti-inflammatory markers in a human coculture model for osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2015. June;43(6):1474-84. Epub 2015 Feb 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kabiri A, Esfandiari E, Esmaeili A, Hashemibeni B, Pourazar A, Mardani M. Platelet-rich plasma application in chondrogenesis. Adv Biomed Res. 2014. June 25;3(1):138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim HJ, Yeom JS, Koh YG, Yeo JE, Kang KT, Kang YM, Chang BS, Lee CK. Anti-inflammatory effect of platelet-rich plasma on nucleus pulposus cells with response of TNF-α and IL-1. J Orthop Res. 2014. April;32(4):551-6. Epub 2013 Dec 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Buul GM, Koevoet WLM, Kops N, Bos PK, Verhaar JA, Weinans H, Bernsen MR, van Osch GJ. Platelet-rich plasma releasate inhibits inflammatory processes in osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Am J Sports Med. 2011. November;39(11):2362-70. Epub 2011 Aug 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bendinelli P, Matteucci E, Dogliotti G, Corsi MM, Banfi G, Maroni P, Desiderio MA. Molecular basis of anti-inflammatory action of platelet-rich plasma on human chondrocytes: mechanisms of NF-κB inhibition via HGF. J Cell Physiol. 2010. November;225(3):757-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fice MP, Miller JC, Christian R, Hannon CP, Smyth N, Murawski CD, Cole BJ, Kennedy JG. The role of platelet-rich plasma in cartilage pathology: an updated systematic review of the basic science evidence. Arthroscopy. 2019. March;35(3):961-976.e3. Epub 2019 Feb 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xie X, Ulici V, Alexander PG, Jiang Y, Zhang C, Tuan RS. Platelet-rich plasma inhibits mechanically induced injury in chondrocytes. Arthroscopy. 2015. June;31(6):1142-50. Epub 2015 Mar 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Karas V, Della Valle C, Tetreault MW, Mohammed HO, Fortier LA. The anti-inflammatory and matrix restorative mechanisms of platelet-rich plasma in osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2014. January;42(1):35-41. Epub 2013 Nov 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen WH, Lo WC, Hsu WC, Wei HJ, Liu HY, Lee CH, Tina Chen SY, Shieh YH, Williams DF, Deng WP. Synergistic anabolic actions of hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma on cartilage regeneration in osteoarthritis therapy. Biomaterials. 2014. December;35(36):9599-607. Epub 2014 Aug 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chahla J, Cinque ME, Piuzzi NS, Mannava S, Geeslin AG, Murray IR, Dornan GJ, Muschler GF, LaPrade RF. A call for standardization in platelet-rich plasma preparation protocols and composition reporting: a systematic review of the clinical orthopaedic literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017. October 18;99(20):1769-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murray IR, Geeslin AG, Goudie EB, Petrigliano FA, LaPrade RF. minimum information for studies evaluating biologics in orthopaedics (MIBO): platelet-rich plasma and mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017. May 17;99(10):809-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kobayashi Y, Saita Y, Nishio H, Ikeda H, Takazawa Y, Nagao M, Takaku T, Komatsu N, Kaneko K. Leukocyte concentration and composition in platelet-rich plasma (PRP) influences the growth factor and protease concentrations. J Orthop Sci. 2016. September;21(5):683-9. Epub 2016 Aug 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riboh JC, Saltzman BM, Yanke AB, Fortier L, Cole BJ. Effect of leukocyte concentration on the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016. March;44(3):792-800. Epub 2015 Apr 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freitag JB, Barnard A. To evaluate the effect of combining photo-activation therapy with platelet-rich plasma injections for the novel treatment of osteoarthritis. Case Reports. 2013;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lo EY, Flanagin BA, Burkhead WZ. Biologic resurfacing arthroplasty with acellular human dermal allograft and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in young patients with glenohumeral arthritis-average of 60 months of at mid-term follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016. July;25(7):e199-207. Epub 2016 Feb 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han Y, Huang H, Pan J, Lin J, Zeng L, Liang G, Yang W, Liu J. Meta-analysis comparing platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid injection in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Med. 2019. March 7:pnz011. Epub 2019 Mar 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andia I, Abate M. Knee osteoarthritis: hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma or both in association? Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014. May;14(5):635-49. Epub 2014 Feb 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saturveithan C, Premganesh G, Fakhrizzaki S, Mahathir M, Karuna K, Rauf K, William H, Akmal H, Sivapathasundaram N, Jaspreet K. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid (HA) and platelet rich plasma (PRP) injection versus hyaluronic acid (HA) injection alone in patients with grade III and IV knee osteoarthritis (OA): a retrospective study on functional outcome. Malays Orthop J. 2016. July;10(2):35-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kavadar G, Demircioglu DT, Celik MY, Emre TY. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of moderate knee osteoarthritis: a randomized prospective study. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015. December;27(12):3863-7. Epub 2015 Dec 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shapiro SA, Kazmerchak SE, Heckman MG, Zubair AC, O’Connor MIA. A prospective, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial of bone marrow aspirate concentrate for knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2017. January;45(1):82-90. Epub 2016 Sep 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chahla J, Mandelbaum BR. Biological treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee: moving from bench to bedside-current practical concepts. Arthroscopy. 2018. May;34(5):1719-29. Epub 2018 Apr 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piuzzi NS, Hussain ZB, Chahla J, Cinque ME, Moatshe G, Mantripragada VP, Muschler GF, LaPrade RF. Variability in the preparation, reporting, and use of bone marrow aspirate concentrate in musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of the clinical orthopaedic literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018. March 21;100(6):517-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anz AW, Hackel JG, Nilssen EC, Andrews JR. Application of biologics in the treatment of the rotator cuff, meniscus, cartilage, and osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014. February;22(2):68-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cassano JM, Kennedy JG, Ross KA, Fraser EJ, Goodale MB, Fortier LA. Bone marrow concentrate and platelet-rich plasma differ in cell distribution and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist protein concentration. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018. January;26(1):333-42. Epub 2016 Feb 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dai WL, Zhou AG, Zhang H, Zhang J. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2017. March;33(3):659-670.e1. Epub 2016 Dec 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang HF, Wang CG, Li H, Huang YT, Li ZJ. Intra-articular platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018. March 5;12:445-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burrow KL, Hoyland JA, Richardson SM. Human adipose-derived stem cells exhibit enhanced proliferative capacity and retain multipotency longer than donor-matched bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells during expansion in vitro. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:2541275 Epub 2017 May 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schneider S, Unger M, van Griensven M, Balmayor ER. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells from liposuction and resected fat are feasible sources for regenerative medicine. Eur J Med Res. 2017. May 19;22(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Denkovskij J, Bagdonas E, Kusleviciute I, Mackiewicz Z, Unguryte A, Porvaneckas N, Fleury S, Venalis A, Jorgensen C, Bernotiene E. Paracrine potential of the human adipose tissue-derived stem cells to modulate balance between matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in the osteoarthritic cartilage in vitro. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:9542702 Epub 2017 Jul 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kalinina N, Kharlampieva D, Loguinova M, Butenko I, Pobeguts O, Efimenko A, Ageeva L, Sharonov G, Ischenko D, Alekseev D, Grigorieva O, Sysoeva V, Rubina K, Lazarev V, Govorun V. Characterization of secretomes provides evidence for adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells subtypes. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015. November 11;6(1):221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Centeno CJ, Al-Sayegh H, Bashir J, Goodyear S, Freeman MD. A prospective multi-site registry study of a specific protocol of autologous bone marrow concentrate for the treatment of shoulder rotator cuff tears and osteoarthritis. J Pain Res. 2015. June 5;8:269-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005. June 1;30(11):1331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Striano RD, Malanga AG, Bilbool N, Khatira A. Refractory shoulder pain with osteoarthritis, and rotator cuff tear, treated with micro-fragmented adipose tissue. Journal of Orthopaedics Spine and Sports Medicine. J Orthop Spine Sports Med. 2018;2(1):014. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Freitag J, Wickham J, Shah K, Tenen A. Effect of autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the treatment of acromioclavicular joint osteoarthritis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019. February 27;12(2):e227865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vega A, Martín-Ferrero MA, Del Canto F, Alberca M, García V, Munar A, Orozco L, Soler R, Fuertes JJ, Huguet M, Sánchez A, García-Sancho J. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: a randomized controlled trial. Transplantation. 2015. August;99(8):1681-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shapiro SA, Arthurs JR, Heckman MG, Bestic JM, Kazmerchak SE, Diehl NN, Zubair AC, O’Connor MI. Quantitative T2 MRI mapping and 12-month follow-up in a randomized, blinded, placebo controlled trial of bone marrow aspiration and concentration for osteoarthritis of the knees. Cartilage. 2019. October;10(4):432-43. Epub 2018 Aug 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Soler R, Orozco L, Munar A, Huguet M, López R, Vives J, Coll R, Codinach M, Garcia-Lopez J. Final results of a phase I-II trial using ex vivo expanded autologous Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee confirming safety and suggesting cartilage regeneration. Knee. 2016. August;23(4):647-54. Epub 2016 Jan 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spasovski D, Spasovski V, Baščarević Z, Stojiljković M, Vreća M, Anđelković M, Pavlović S. Intra-articular injection of autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. J Gene Med. 2018. January;20(1):e3002 Epub 2018 Jan 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Freitag J, Bates D, Wickham J, Shah K, Huguenin L, Tenen A, Paterson K, Boyd R. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Regen Med. 2019. March;14(3):213-30. Epub 2019 Feb 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]