Abstract

Mutations in genes encoding synaptic proteins cause many neurodevelopmental disorders, with the majority affecting postsynaptic apparatuses and much fewer in presynaptic proteins. Syntaxin-binding protein 1 (STXBP1, also known as MUNC18-1) is an essential component of the presynaptic neurotransmitter release machinery. De novo heterozygous pathogenic variants in STXBP1 are among the most frequent causes of neurodevelopmental disorders including intellectual disabilities and epilepsies. These disorders, collectively referred to as STXBP1 encephalopathy, encompass a broad spectrum of neurologic and psychiatric features, but the pathogenesis remains elusive. Here we modeled STXBP1 encephalopathy in mice and found that Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency caused cognitive, psychiatric, and motor dysfunctions, as well as cortical hyperexcitability and seizures. Furthermore, Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency reduced cortical inhibitory neurotransmission via distinct mechanisms from parvalbumin-expressing and somatostatin-expressing interneurons. These results demonstrate that Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice recapitulate cardinal features of STXBP1 encephalopathy and indicate that GABAergic synaptic dysfunction is likely a crucial contributor to disease pathogenesis.

Research organism: Mouse

Introduction

Human genetic studies of neurodevelopmental disorders continue to uncover pathogenic variants in genes encoding synaptic proteins (Hoischen et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2014; Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study, 2015; Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study, 2017; Stessman et al., 2017; Lindy et al., 2018), demonstrating the importance of these proteins for neurologic and psychiatric features. The molecular and cellular functions of many of these synaptic proteins have been extensively studied. However, to understand the pathological mechanisms underlying these synaptic disorders, in-depth neurological and behavioral studies in animal models are necessary. While it is difficult to perform such studies for all disorders, this knowledge gap can be significantly narrowed by studying a few prioritized genes that are highly penetrant and affect a broad spectrum of neurologic and psychiatric features common among neurodevelopmental disorders (Hoischen et al., 2014; Ogden et al., 2016). Syntaxin-binding protein 1 (STXBP1, also known as MUNC18-1) is one such example because its molecular and cellular functions are well understood (Rizo and Xu, 2015), its pathogenic variants are emerging as prevalent causes of multiple neurodevelopmental disorders (Stamberger et al., 2016), and yet it remains unclear how its dysfunction causes disease.

Stxbp1/Munc18-1 is involved in synaptic vesicle docking, priming, and fusion through multiple interactions with the neuronal soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor-attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) (Rizo and Xu, 2015). Genetic deletion of Stxbp1 in worms, flies, mice, and fish abolishes neurotransmitter release and leads to lethality and cell-intrinsic degeneration of neurons (Harrison et al., 1994; Verhage, 2000; Weimer et al., 2003; Heeroma et al., 2004; Grone et al., 2016). In humans, STXBP1 de novo heterozygous mutations cause several of the most severe forms of epileptic encephalopathies including Ohtahara syndrome (Saitsu et al., 2008; Saitsu et al., 2010), West syndrome (Deprez et al., 2010; Otsuka et al., 2010), Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (Carvill et al., 2013; Allen et al., 2013), Dravet syndrome (Carvill et al., 2014), and other types of early-onset epileptic encephalopathies (Deprez et al., 2010; Mignot et al., 2011; Stamberger et al., 2016). Furthermore, STXBP1 is one of the most frequently mutated genes in sporadic intellectual disabilities and developmental disorders (Hamdan et al., 2009; Hamdan et al., 2011; Rauch et al., 2012; Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study, 2015; Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study, 2017; Suri et al., 2017). All STXBP1 encephalopathy patients show intellectual disability, mostly severe to profound, and 95% of patients have epilepsy (Stamberger et al., 2016). More than 90% of patients have motor deficits, such as dystonia, spasticity, ataxia, hypotonia, and tremor. Other clinical features in subsets of patients include developmental delay, hyperactivity, anxiety, stereotypies, aggressive behaviors, and autistic features (Hamdan et al., 2009; Deprez et al., 2010; Mignot et al., 2011; Milh et al., 2011; Campbell et al., 2012; Rauch et al., 2012; Weckhuysen et al., 2013; Boutry-Kryza et al., 2015; Stamberger et al., 2016; Suri et al., 2017).

STXBP1 encephalopathy is mostly caused by haploinsufficiency because more than 60% of the reported mutations are either deletions, nonsense, frameshift, or splice site variants (Stamberger et al., 2016). A subset of missense variants were shown to destabilize the protein (Saitsu et al., 2008; Saitsu et al., 2010; Guiberson et al., 2018; Kovacevic et al., 2018) and cause aggregation to further reduce the wild type (WT) protein levels (Guiberson et al., 2018). Thus, partial loss-of-function of Stxbp1 in vivo would offer opportunities to model STXBP1 encephalopathy and study its pathogenesis. Indeed, removing stxbp1b, one of the two STXBP1 homologs in zebrafish, caused spontaneous electrographic seizures (Grone et al., 2016). Three different Stxbp1 null alleles have been generated in mice (Verhage, 2000; Miyamoto et al., 2017; Kovacevic et al., 2018). However, previous characterization of the corresponding heterozygous knockout mice was limited in scope, used relatively small cohorts, and yielded inconsistent results. For example, the reported cognitive phenotypes in mutant mice are mild or inconsistent between studies (Miyamoto et al., 2017; Kovacevic et al., 2018; Orock et al., 2018). Motor dysfunctions and several psychiatric deficits were not reported in previous studies (Hager et al., 2014; Miyamoto et al., 2017; Kovacevic et al., 2018; Orock et al., 2018). Thus, a comprehensive neurological and behavioral study of Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency models is still lacking. Interestingly, Stxbp1 protein levels were reduced by only 25% in the brain of one line of previous Stxbp1 heterozygous knockout mice (Orock et al., 2018) and 25% in the cortex and 50% in the hippocampus of another line (Miyamoto et al., 2017). Although STXBP1 levels in human patients are unknown, mouse models with a stronger reduction in Stxbp1 levels are desirable to determine to what extent Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice can recapitulate the neurological phenotypes of STXBP1 encephalopathy. Furthermore, it remains elusive how STXBP1 haploinsufficiency in vivo leads to hyperexcitable neural circuits and neurological deficits.

To address these questions and enhance the robustness and reproducibility of preclinical models of STXBP1 haploinsufficiency, we developed two new genetically distinct Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency mouse models and performed parallel studies on both of them. These mutant mice showed a 40–50% reduction of Stxbp1 protein levels in most brain regions and recapitulated all key phenotypes observed in the human condition including seizures and impairments in cognitive, psychiatric, and motor functions. Electrophysiological and optogenetic experiments revealed that Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency reduced cortical inhibition through two distinct mechanisms from two main classes of GABAergic neurons: reducing the synaptic strength of parvalbumin-expressing (Pv) interneurons and decreasing the connectivity of somatostatin-expressing (Sst) interneurons. Thus, these results demonstrate a crucial role of Stxbp1 in neurologic and psychiatric functions and indicate that Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice are construct- and face-valid models of STXBP1 encephalopathy. Furthermore, the reduced inhibition is likely a major contributor to the cortical hyperexcitability and neurobehavioral phenotypes. The differential effects on Pv and Sst interneuron-mediated inhibition suggest synapse-specific functions of Stxbp1 and also highlight the necessity of studying synaptic specificity and diversity in neural circuits of synaptopathies.

Results

Generation of two new genetically distinct Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency mouse models

To model STXBP1 haploinsufficiency in mice, we first generated a knockout-first (KO-first) allele (tm1a), in which the Stxbp1 genomic locus was targeted with a multipurpose cassette (Testa et al., 2004; Skarnes et al., 2011). The targeted allele contains a splice acceptor site from Engrailed 2 (En2SA), an encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosomal entry site (IRES), lacZ, and SV40 polyadenylation element (pA) that trap the transcripts after exon 6, thereby truncating the Stxbp1 mRNA. The trapping cassette (En2SA-IRES-lacZ-pA) and exon 7 are flanked by two FRT sites and two loxP sites, respectively (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). By sequentially crossing with Flp and Cre germline deleter mice, we removed both the trapping cassette and exon 7 from the heterozygous KO-first mice, which leads to a premature stop codon in exon 8 and generates a conventional knockout (KO) allele (tm1d) (Figure 1A). Heterozygous KO (Stxbp1tm1d/+) and KO-first (Stxbp1tm1a/+) mice are maintained on the C57BL/6J isogenic background for all experiments.

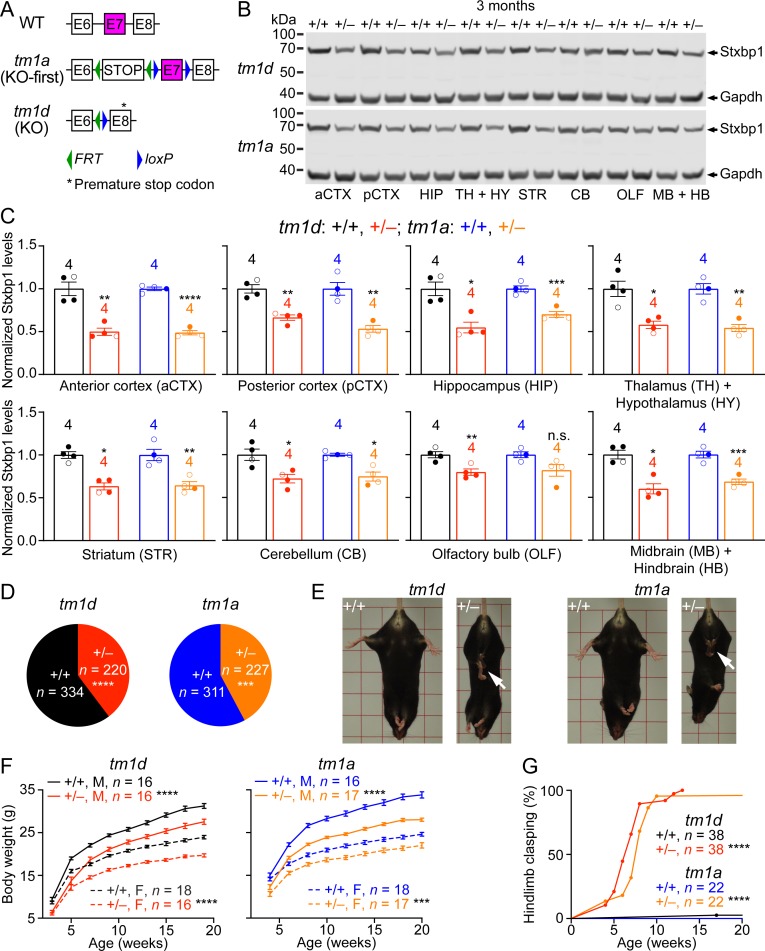

Figure 1. Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice exhibit reduced Stxbp1 levels, survival, and body weights and develop hindlimb clasping.

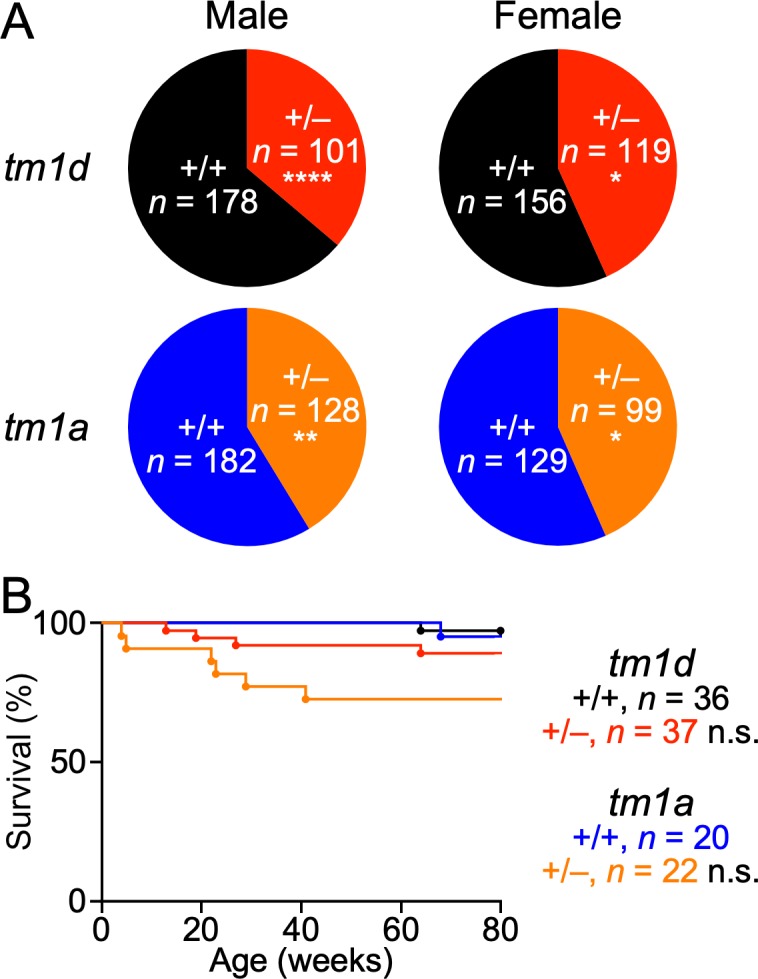

(A) Genomic structures of Stxbp1 WT, tm1a (KO-first), and tm1d (KO) alleles. In the tm1a allele, the STOP including the En2SA-IRES-lacZ-pA trapping cassette (see Figure 1—figure supplement 1A) truncates the Stxbp1 mRNA after exon 6. In the tm1d allele, exon 7 is deleted, resulting in a premature stop codon in exon 8. E, exon; FRT, Flp recombination site; loxP, Cre recombination site. (B) Representative Western blots of proteins from different brain regions of 3-month-old WT, Stxbp1tm1d/+, and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice. Gapdh, a housekeeping protein as loading control. The brain regions are labeled by the same abbreviations as in (C). (C) Summary data of normalized Stxbp1 expression levels from different brain regions. Stxbp1 levels were first normalized by the Gapdh levels and then by the average Stxbp1 levels of all WT mice from the same blot. Each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents one mouse. (D) Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ male mice were crossed with WT female mice. Pie charts show the observed genotypes of the offspring at weaning (i.e., around the age of 3 weeks). Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice were significantly less than Mendelian expectations. (E) Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice were smaller and showed hindlimb clasping (arrows). (F) Body weights as a function of age. M, male; F, female. (G) The fraction of mice with hindlimb clasping as a function of age. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

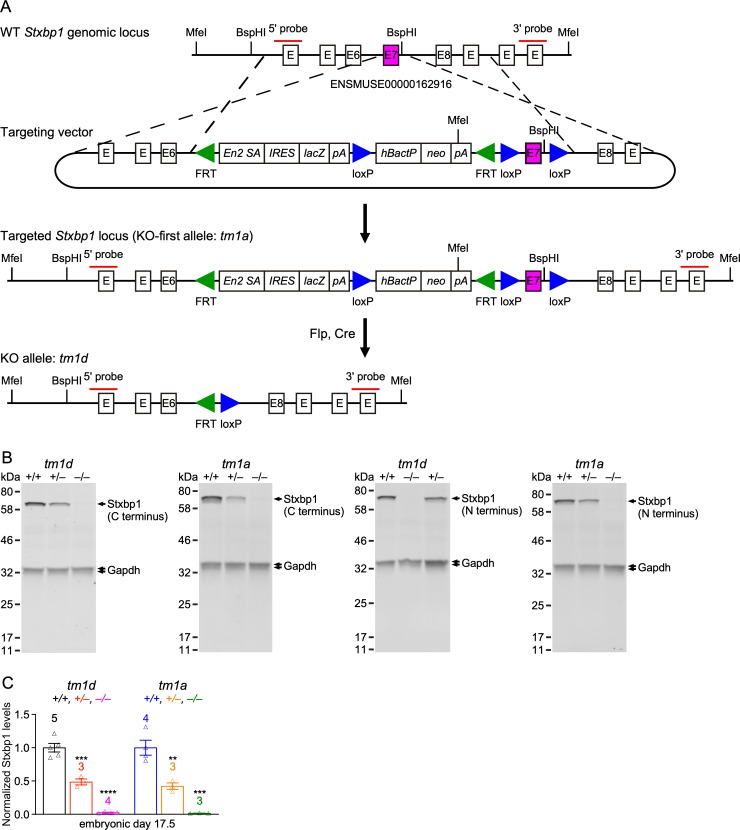

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Generation of two new Stxbp1 null alleles.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Reduced survival of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice.

Homozygous mutants (Stxbp1tm1d/tm1d and Stxbp1tm1a/tm1a) died immediately after birth because they were completely paralyzed and could not breathe, consistent with the previous Stxbp1 null alleles (Verhage, 2000; Miyamoto et al., 2017). Western blots with antibodies recognizing either the N- or C-terminus of Stxbp1 showed that at embryonic day 17.5, Stxbp1 protein was absent in Stxbp1tm1d/tm1d and Stxbp1tm1a/tm1a mice, and reduced by 50% in Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B,C), indicating that both tm1d and tm1a are null alleles. We surveyed the Stxbp1 protein levels in different brain regions of Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice at 3 months of age. Stxbp1 was reduced by 40–50% in most brain areas except the cerebellum and olfactory bulb where the reduction was 20–30% (Figure 1B,C). These results demonstrate that Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ are indeed Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice. In theory, the tm1d and tm1a alleles could produce a truncated Stxbp1 protein of 18 kD and 16 kD, respectively. However, no such truncated proteins were observed in either heterozygous or homozygous mutants (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B), most likely because the truncated Stxbp1 transcripts were degraded due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (Chang et al., 2007).

Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice show a reduction in survival and body weights, and developed hindlimb clasping

We bred Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice with WT mice and found that at the time of genotyping (i.e., around postnatal week 3) Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice are 40% and 43% of the total offspring, respectively (Figure 1D and Figure 1—figure supplement 2A), indicating a postnatal lethality phenotype. However, the lifespans of many mutant mice that survived through weaning were similar to those of WT littermates (Figure 1—figure supplement 2B). Thus, Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice show reduced survival, but this phenotype is not fully penetrant. Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice appeared smaller and their body weights were consistently about 20% less than their sex- and age-matched WT littermates (Figure 1E,F). At 4 weeks of age, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice began to exhibit abnormal hindlimb clasping, indicative of dystonia or spasticity (Figure 1E). By the age of 3 months, almost all mutant mice developed hindlimb clasping (Figure 1G). Thus, these observations indicate neurological deficits in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice.

Guided by the symptoms of STXBP1 encephalopathy human patients, we sought to perform behavioral and physiological assays to further examine the neurologic and psychiatric functions in male and female Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice and their sex- and age-matched WT littermates.

Impaired motor and normal sensory functions in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice

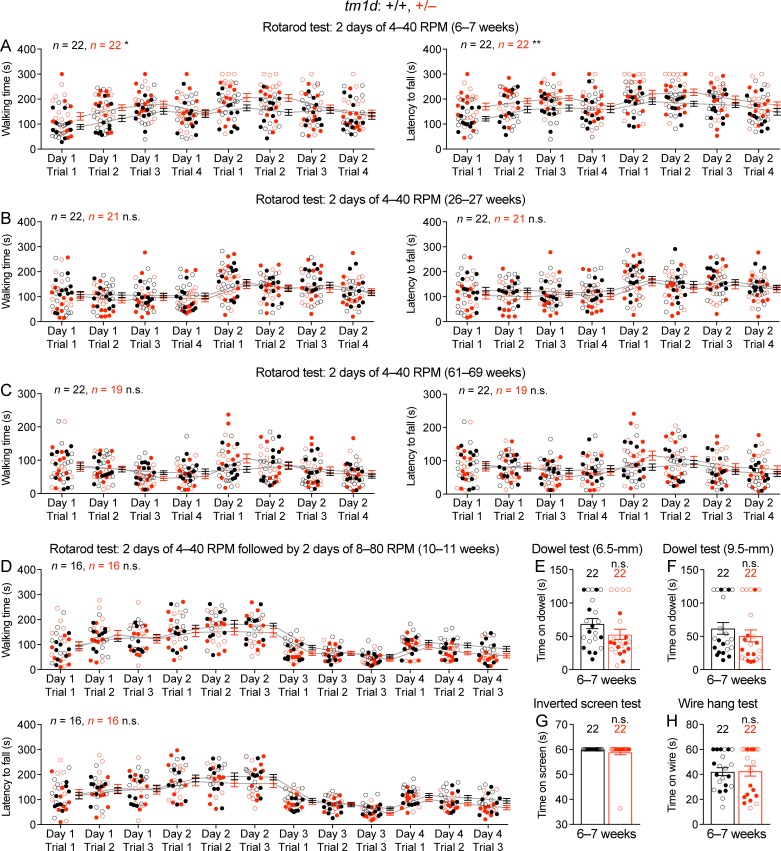

Motor impairments including dystonia, spasticity, ataxia, hypotonia, and tremor are frequently observed in STXBP1 encephalopathy patients. Thus, we first assessed general locomotion by the open-field test where a mouse is allowed to freely explore an arena (Figure 2A). The locomotion of Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice was largely normal, but they traveled longer distances and faster than WT mice, indicating that Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice are hyperactive (Figure 2B,C). Both Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice explored the center region of the arena less than WT mice (Figure 2D) and made less vertical movements (Figure 2E), indicating that the mutant mice are more anxious. This anxiety phenotype was later confirmed by two other assays that specifically assess anxiety (see below). We used a variety of assays to further evaluate motor functions. Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice performed similarly to WT mice in the rotarod test, dowel test, inverted screen test, and wire hang test (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). However, the forelimb grip strength of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice was weaker (Figure 2F). Furthermore, in the foot slip test where a mouse is allowed to walk on a wire grid, both Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice were not able to place their paws precisely on the wire to hold themselves and made many more foot slips than WT mice (Figure 2G). To assess the agility of mice, we performed the vertical pole test, which is often used to measure the bradykinesia of parkinsonism. When mice were placed head-up on the top of a vertical pole, it took mutant mice longer to orient themselves downward and descend the pole than WT mice (Figure 2H). Together, these results indicate that Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice do not develop ataxia, but their fine motor coordination and muscle strength are reduced.

Figure 2. Motor dysfunctions of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice.

(A) Representative tracking plots of the mouse positions in the open-field test. Note that Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice traveled less in the center (dashed box) than WT mice. (B–E) Summary data showing hyperactivity and anxiety-like behaviors of Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice in the open-field test. Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice showed an increase in the total moving distance (B) and speed (C), and a decrease in the ratio of center moving distances over total moving distance (D) and vertical activity (E). (F–H) Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice had weaker forelimb grip strength (F), made more foot slips per travel distance on a wire grid (G), and took more time to get down from a vertical pole (H). The numbers and ages of tested mice are indicated in the figures. Each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents one mouse. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Normal performance of Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice in rotarod, dowel, inverted screen, and wire hang tests.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice have normal sensory functions.

We next examined the acoustic sensory function and found that Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice showed normal startle responses to different levels of sound (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A). To test sensorimotor gating, we measured the pre-pulse inhibition where the startle response to a strong sound is reduced by a preceding weaker sound. Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice displayed similar pre-pulse inhibition as WT mice (Figure 2—figure supplement 2B). They also had normal nociception as measured by the hot plate test (Figure 2—figure supplement 2C). Thus, the sensory functions and sensorimotor gating of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice are normal.

Cognitive functions of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice are severely impaired

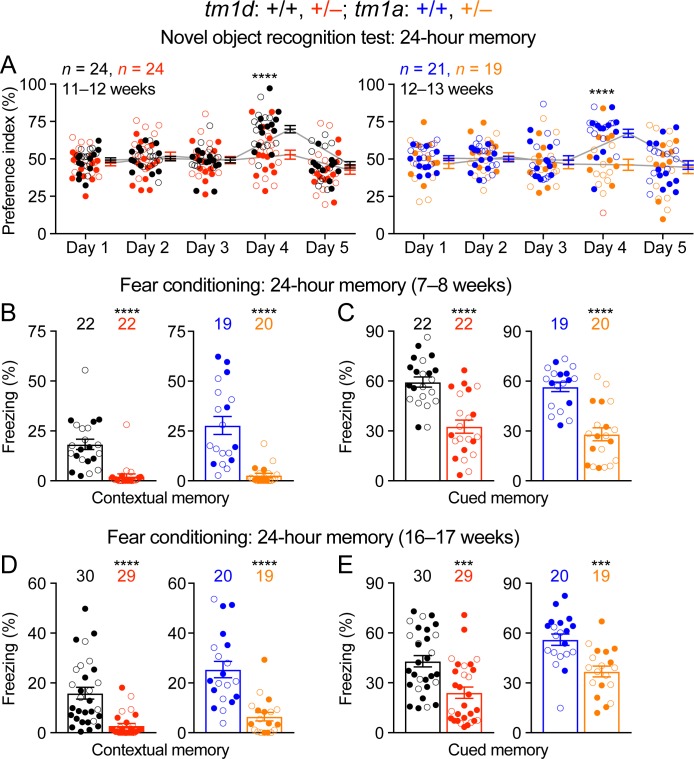

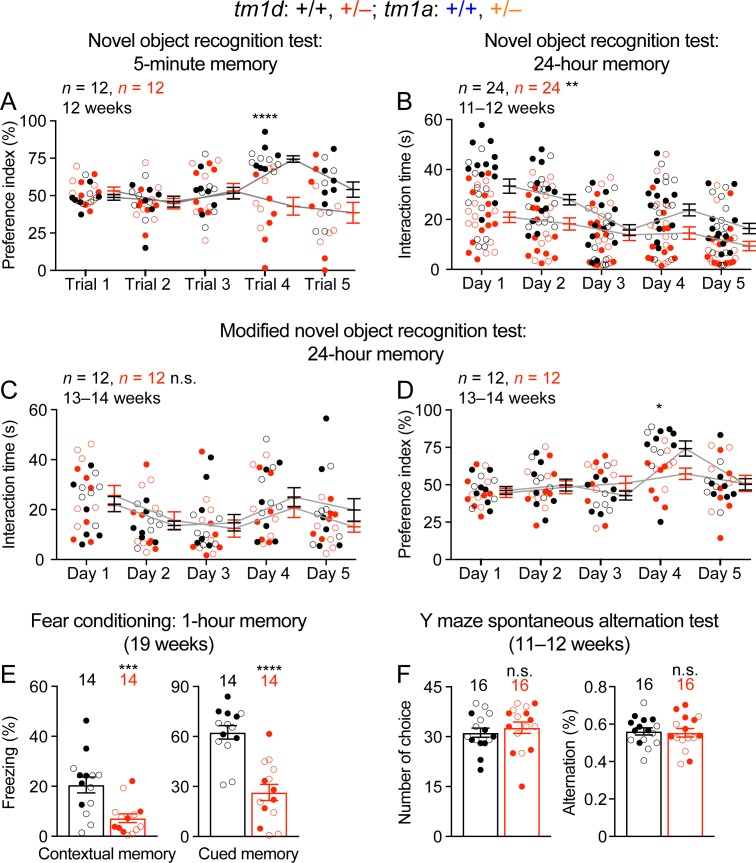

Intellectual disability is a core feature of STXBP1 encephalopathy, as the vast majority of patients have severe to profound intellectual disability (Stamberger et al., 2016). However, the learning and memory deficits described in the previous Stxbp1 heterozygous knockout mice are mild and inconsistent (Miyamoto et al., 2017; Kovacevic et al., 2018; Orock et al., 2018). To assess cognitive functions, we tested Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice in three different paradigms, object recognition, associative learning and memory, and working memory. First, we performed the novel object recognition test that exploits the natural tendency of mice to explore novel objects to evaluate their memories. This task is thought to depend on the hippocampus and cortex (Antunes and Biala, 2012; Cohen and Stackman, 2015). When tested with an inter-trial interval of 24 hr, WT mice interacted more with the novel object than the familiar object, whereas Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice interacted equally between the familiar and novel objects (Figure 3A). We also evaluated Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice with an inter-trial interval of 5 min and observed a similar deficit (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A). We noticed that mutant mice overall spent less time interacting with the objects than WT mice during the trials (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B), which might reduce their ‘memory load’ of the objects. We hence allowed Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice to spend twice as much time as WT mice in each trial to increase their interaction time with the objects (Figure 3—figure supplement 1C), but they still showed a similar deficit in recognition memory (Figure 3—figure supplement 1D). Thus, both long-term and short-term recognition memories are impaired in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice.

Figure 3. Impaired cognition of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice.

(A) In the novel object recognition test with 24 hr testing intervals, the ability of a mouse to recognize the novel object was assessed by the preference index (see Materials and methods). On days 1, 2, 3, and 5, mice were presented with the same two identical objects. In contrast to WT mice, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice did not show a preference for the novel object on day 4 when they were presented with the familiar object and a novel object. (B–E) In the fear conditioning test, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice at two different ages showed a reduction in both context-induced (B,D) and cue-induced (C,E) freezing behaviors 24 hr after training. The numbers and ages of tested mice are indicated in the figures. Each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents one mouse. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice show an impairment in object recognition and fear memory, but not working memory.

Second, we used the Pavlovian fear conditioning paradigm to evaluate associative learning and memory, in which a mouse learns to associate a specific environment (i.e., the context) and a sound (i.e., the cue) with electric foot shocks. The fear memory is manifested by the mouse freezing when it is subsequently exposed to this specific context or cue without electric shocks. At two tested ages, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice displayed a profound reduction in both context- and cue-induced freezing behaviors when tested 24 hr after the conditioning paradigm (Figure 3B–E). We also tested Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice 1 hr after the conditioning paradigm and observed similar deficits (Figure 3—figure supplement 1E). Since the acoustic startle response and nociception are intact in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A,C), these results indicate that Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency impairs both hippocampus-dependent contextual and hippocampus-independent cued fear memories.

Finally, we used the Y maze spontaneous alternation test to examine working memory, but did not observe significant difference between Stxbp1tm1d/+ and WT mice (Figure 3—figure supplement 1F). Taken together, our results indicate that both long-term and short-term forms of recognition and associative memories are severely impaired in Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency mice, but their working memory is intact.

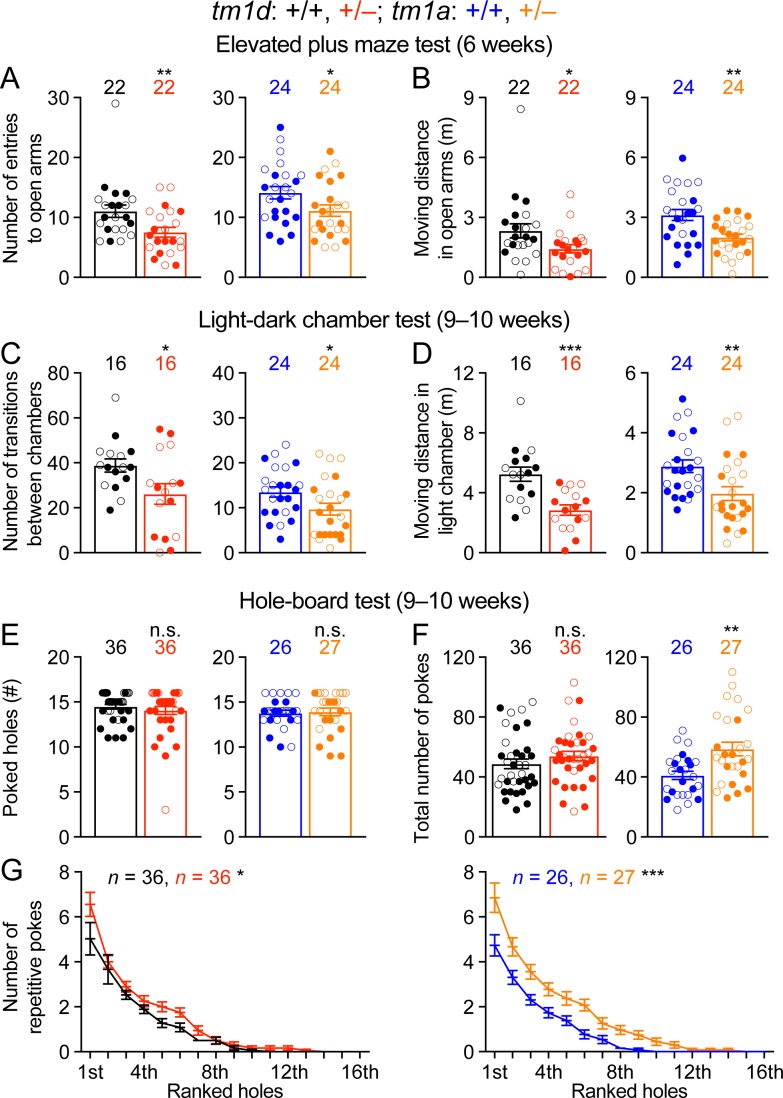

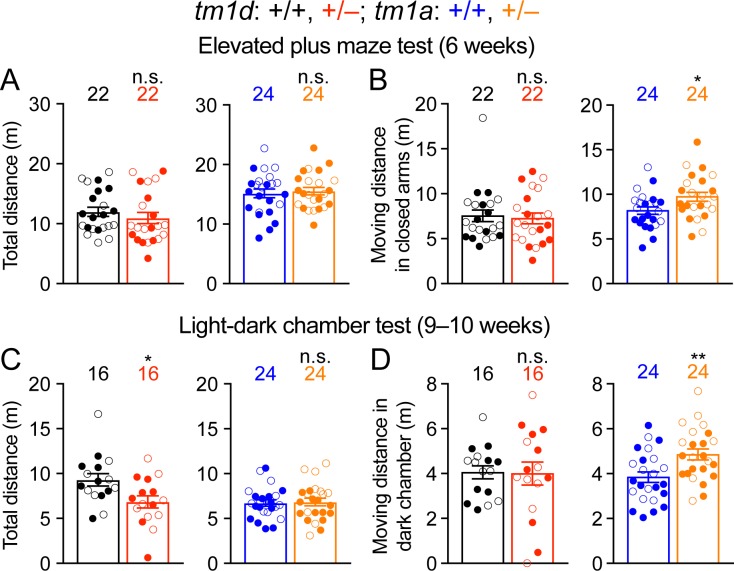

Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice exhibit an increase in anxiety-like and repetitive behaviors

A number of psychiatric phenotypes including hyperactivity, anxiety, stereotypies, aggression, and autistic features were reported in subsets of STXBP1 encephalopathy patients. We used a battery of behavioral assays to characterize each of these features in Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency mice. The open-field test indicates that Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency mice are hyperactive and more anxious than WT mice (Figure 2A–E). To specifically assess anxiety-like behaviors, we tested Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice in the elevated plus maze and light-dark chamber tests where a mouse is allowed to explore the open or closed arms of the maze and the clear or black chamber of the box, respectively. Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice entered the open arms and clear chamber less frequently and traveled shorter distance in the open arms and clear chamber than WT mice (Figure 4A–D; Figure 4—figure supplement 1A–D). Hence, these results confirm the heightened anxiety in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice and are consistent with the previous studies (Hager et al., 2014; Miyamoto et al., 2017; Kovacevic et al., 2018).

Figure 4. Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice show increased anxiety-like and repetitive behaviors.

(A,B) In the elevated plus maze test, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice entered the open arms less frequently (A) and traveled shorter distance in the open arms (B). (C,D) In the light-dark chamber test, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice made less transitions between the light and dark chambers (C) and traveled shorter distance in the light chamber (D). (E–G) In the hole-board test, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice poked similar numbers of holes as WT mice (E) and made similar or more total nose pokes (F). They made more repetitive nose pokes (i.e.,≥2 consecutive pokes) than WT mice across different holes (G). The numbers and ages of tested mice are indicated in the figures. Each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents one mouse. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. n.s., p>0.05; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. The movements of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice in elevated plus maze and light-dark chamber tests.

To assess the stereotyped and repetitive behaviors, we used the hole-board test to measure the pattern of mouse exploratory nose poke (also called head dipping) behavior. As compared to WT mice, Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice explored similar numbers of holes (Figure 4E) and made similar or larger numbers of nose pokes (Figure 4F). We analyzed the repetitive nose pokes (i.e.,≥2 consecutive pokes) into the same hole as a measure of repetitive behaviors. The mutant mice made more repetitive nose pokes than WT mice across many holes (Figure 4G), indicating that Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency in mice causes abnormal stereotypy and repetitive behaviors, a psychiatric feature observed in about 20% of the STXBP1 encephalopathy patients (Stamberger et al., 2016).

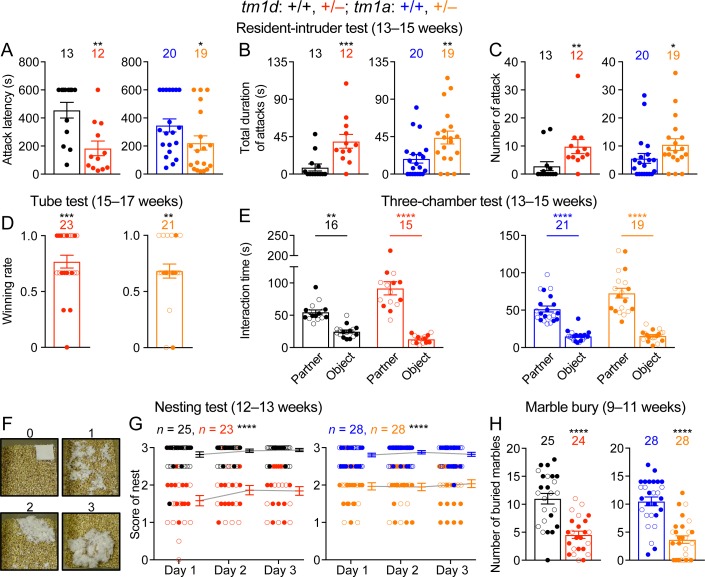

Social aggression of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice are elevated

During daily mouse husbandry, we noticed incidences of fighting and injuries of WT and Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice in their home cages, but no injuries were observed when Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice were singly housed, suggesting that the injuries likely resulted from fighting instead of self-injury. To formally examine aggressive behaviors, we first performed the resident-intruder test, in which a male intruder mouse is introduced into the home cage of a male resident mouse, and the aggressive behaviors of the resident towards the intruder were scored. As compared to WT mice, male resident Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice were more likely to attack and spent more time attacking the intruders (Figure 5A–C). Another paradigm to assess aggression and social dominance is the tube test, in which two mice are released into the opposite ends of a tube, and the more dominant and aggressive mouse will win the competition by pushing its opponent out of the tube. When Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice were placed against their sex- and age-matched WT littermates, Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice won more competitions despite their smaller body sizes (Figure 5D). Thus, Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency elevates innate aggression in mice.

Figure 5. Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice show increased aggressive behaviors and reduced nest building and digging behaviors.

(A–C) In the resident-intruder test, male Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice showed a reduction in the latency to attack the male intruder mice (A). The total duration (B) and number (C) of their attacks were increased as compared to WT mice. (D) In the tube test, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice won more competitions against their WT littermates. (E) In the three-chamber test, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice showed a preference in interacting with the partner mouse over the object. (F,G) Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice built poor quality nests. The quality of the nests was scored according to the criteria in (F) for three consecutive days (G). (H) Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice buried fewer marbles than WT mice. The numbers and ages of tested mice are indicated in the figures. Each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents one mouse. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice show normal social interactions.

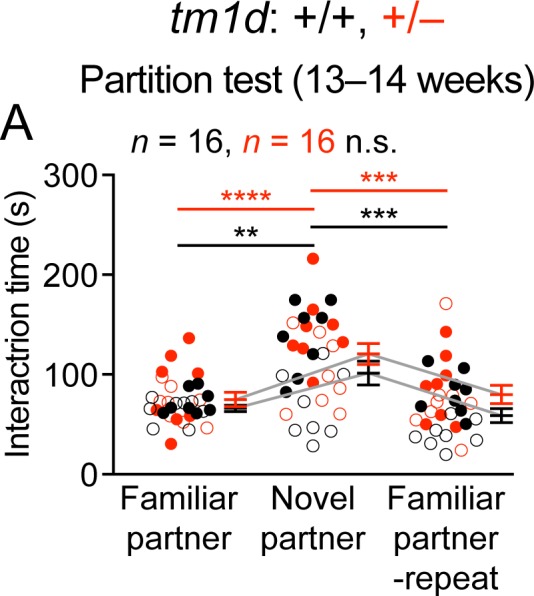

To further evaluate social interaction, we performed the three-chamber test where a mouse is allowed to interact with an object or a sex- and age-matched partner mouse. Like WT mice, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice preferred to interact with the partner mice rather than the objects (Figure 5E), indicating that Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency does not compromise general sociability. Interestingly, the mutant mice in fact spent significantly more time than WT mice interacting with the partner mice (p<0.0001 for Stxbp1tm1d/+ vs. WT and p=0.0015 for Stxbp1tm1a/+ vs. WT), which might be due to the increased aggression of the mutant mice. Furthermore, we used the partition test to examine the preference for social novelty, in which a mouse is allowed to interact with a familiar or novel partner mouse. Both WT and Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice preferentially interacted more with the novel partner mice (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A). These results indicate that the general sociability and interest in social novelty are normal in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice.

Reduced nest building and digging behaviors in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice

To further assess the well-being and psychiatric phenotypes of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice, we performed the Nestlet shredding test and marble burying test to examine two innate behaviors, nest building and digging, respectively. We provided a Nestlet (pressed cotton square) to each mouse in the home cage and scored the degree of shredding and nest quality after 24, 48, and 72 hr (Figure 5F). Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice consistently scored lower than WT mice at all time points (Figure 5G). In the marble burying test, the Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice buried fewer marbles than WT mice (Figure 5H). The interpretation of marble burying remains controversial, as it may measure anxiety, compulsive-like behavior, or simply digging behavior (Deacon, 2006; Thomas et al., 2009; Wolmarans et al., 2016). Since Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice show elevated anxiety and repetitive behaviors, the reduced marble burying likely reflects an impairment of digging behavior, possibly due to the motor deficits. Likewise, the motor deficits may also contribute to the reduced nest building behavior.

Cortical hyperexcitability and epileptic seizures in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice

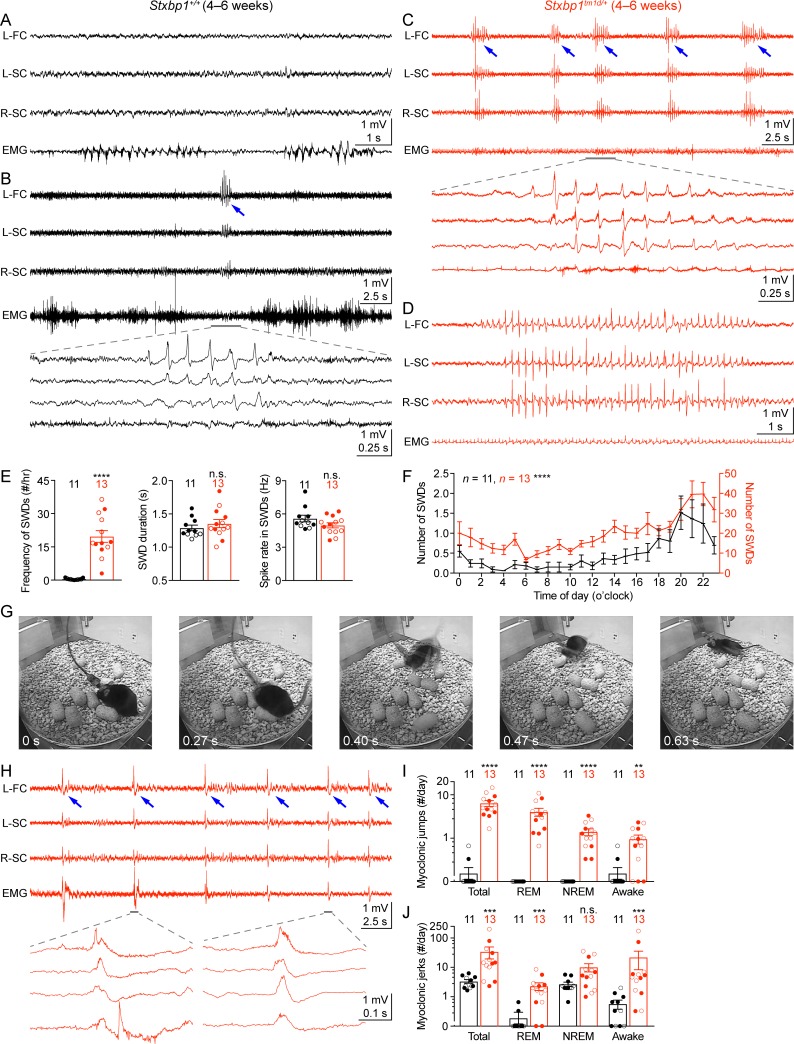

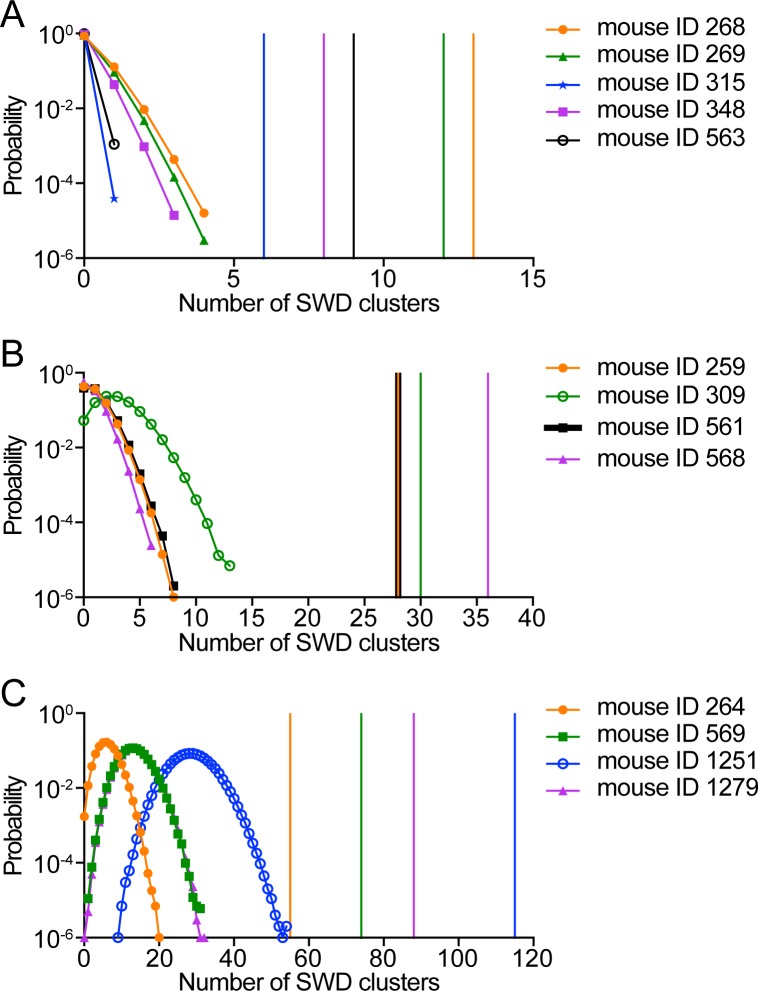

Another core feature of STXBP1 encephalopathy is epilepsy with a broad spectrum of seizure types, such as epileptic spasm, focal, tonic, clonic, myoclonic, and absence seizures (Stamberger et al., 2016; Suri et al., 2017). To investigate if Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice have abnormal cortical activity and epileptic seizures, we performed chronic video-electroencephalography (EEG) and electromyography (EMG) recordings in freely moving Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice and their sex- and age-matched WT littermates. We implanted three EEG electrodes in the frontal and somatosensory cortices and an EMG electrode in the neck muscles to record intracranial EEG and EMG, respectively, for at least 72 hr (Figure 6A). The phenotypes of each mouse are summarized in Supplementary file 1. Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice exhibited cortical hyperexcitability and several epileptiform activities. First, they had numerous spike-wave discharges (SWDs) that typically were 3–6 Hz and lasted 1–2 s (Figure 6C,E,F). These oscillations showed similar characteristics to those generalized spike-wave discharges observed in animal models of absence seizures (Maheshwari and Noebels, 2014; Depaulis and Charpier, 2018). A much smaller number of SWDs with similar characteristics were also observed in WT mice (Figure 6B,E), consistent with previous studies (Arain et al., 2012; Letts et al., 2014). On average, the frequency of SWD episodes in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice was more than 40-fold higher than that in WT mice (Figure 6E,F). Importantly, SWDs frequently occurred in a cluster manner (i.e.,≥5 episodes with an inter-episode-interval of ≤60 s) in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice, which never occurred in WT mice (Figure 6—figure supplement 1; Video 1). Furthermore, 56 episodes of SWDs from 10 out of 13 Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice lasted more than 4 s, among which 54 episodes occurred during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Figure 6D; Video 2) and the other two episodes occurred when mice were awake. In contrast, only 1 out of 11 WT mice had 3 episodes of such long SWDs, all of which occurred when mice were awake (Supplementary file 1). In Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice, SWDs were most frequent during the night, but occurred throughout the day and night (Figure 6F), indicating a general cortical hyperexcitability and abnormal synchrony in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice.

Figure 6. Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice exhibit cortical hyperexcitability and epileptic seizures.

(A–D) Representative EEG traces of the left frontal cortex (L-FC), left somatosensory cortex (L-SC), and right somatosensory cortex (R-SC), and EMG traces of the neck muscle from WT (A,B) and Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice (C,D). Spike-wave discharges (SWDs, indicated by the blue arrows) occurred frequently and often in a cluster manner in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice (see Video 1). The gray line-highlighted SWDs from WT and Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice were expanded to show the details of the oscillations (B,C). A long SWD (i.e.,>4 s) during REM sleep from a Stxbp1tm1d/+ mouse is shown in (D) (see Video 2). (E) Summary data showing the overall SWD frequency (left panel), duration (middle panel), and average spike rate (right panel). (F) The numbers of SWDs per hour in WT (left Y axis) and Stxbp1tm1d/+ (right Y axis) mice are plotted as a function of time of day and averaged over 3 days. (G) Video frames showing a myoclonic jump from a Stxbp1tm1d/+ mouse (see Video 3). The mouse was in REM sleep before the jump. (H) Representative EEG and EMG traces showing myoclonic jerks (indicated by the blue arrows) from a Stxbp1tm1d/+ mouse (see Video 4). Two episodes of myoclonic jerks highlighted by the gray lines were expanded to show that the EEG discharges occurred prior to (the first episode) or simultaneously with (the second episode) the EMG discharges. (I,J) Summary data showing the frequencies of two types of myoclonic seizures in different behavioral states. The numbers and ages of recorded mice are indicated in the figures. Each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents one mouse. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. n.s., p>0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. The clustering of SWDs in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice does not result from a random distribution of frequent SWD episodes.

Video 1. Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice show clusters of SWDs.

A representative video showing a SWD cluster in a Stxbp1tm1d/+ mouse. The top three traces are EEG signals from the left frontal cortex, right somatosensory cortex, and left somatosensory cortex. The bottom trace is the EMG signal from the neck muscle. The vertical line indicates the time of the current video frame. Note that the EEG signal from the left somatosensory cortex (the third channel) is inverted.

Video 2. Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice show long SWDs.

A representative video showing a long SWD during REM sleep in a Stxbp1tm1d/+ mouse. The top three traces are EEG signals from the left frontal cortex, right somatosensory cortex, and left somatosensory cortex. The bottom trace is the EMG signal from the neck muscle. The vertical line indicates the time of the current video frame. Note that the EEG signal from the left somatosensory cortex (the third channel) is inverted.

Second, Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice experienced frequent myoclonic seizures that manifested as sudden jumps or more subtle, involuntary muscle jerks associated with EEG discharges (Figure 6G,H). The large movement artifacts associated with the myoclonic jumps precluded proper interpretation of EEG signals, but this type of myoclonic seizures was observed in all 13 recorded Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice and the majority of episodes occurred during REM or non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (Figure 6I; Video 3). There were three similar jumps in 2 out of 11 WT mice that were indistinguishable from those in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice, but all of them occurred when mice were awake (Figure 6I). Moreover, the more subtle myoclonic jerks occurred frequently and often in clusters in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice, whereas only isolated events were observed in WT mice at a much lower frequency (Figure 6H,J; Video 4). EEG and EMG recordings showed that the cortical EEG spikes associated with the myoclonic jerks occurred before or simultaneously with the neck muscle EMG discharges (Figure 6H), consistent with the cortical or subcortical origins of myoclonuses, respectively (Avanzini et al., 2016).

Video 3. Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice show myoclonic jumps.

A representative video showing a myoclonic jump of a Stxbp1tm1d/+ mouse. The top three traces are EEG signals from the left frontal cortex, right somatosensory cortex, and left somatosensory cortex. The bottom trace is the EMG signal from the neck muscle. The vertical line indicates the time of the current video frame. Note that the EEG signal from the left somatosensory cortex (the third channel) is inverted.

Video 4. Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice show myoclonic jerks.

A representative video showing a myoclonic jerk of a Stxbp1tm1d/+ mouse. The top three traces are EEG signals from the left frontal cortex, right somatosensory cortex, and left somatosensory cortex. The bottom trace is the EMG signal from the neck muscle. The vertical line indicates the time of the current video frame. Note that the EEG signal from the left somatosensory cortex (the third channel) is inverted.

Normal cortical neuron densities in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice

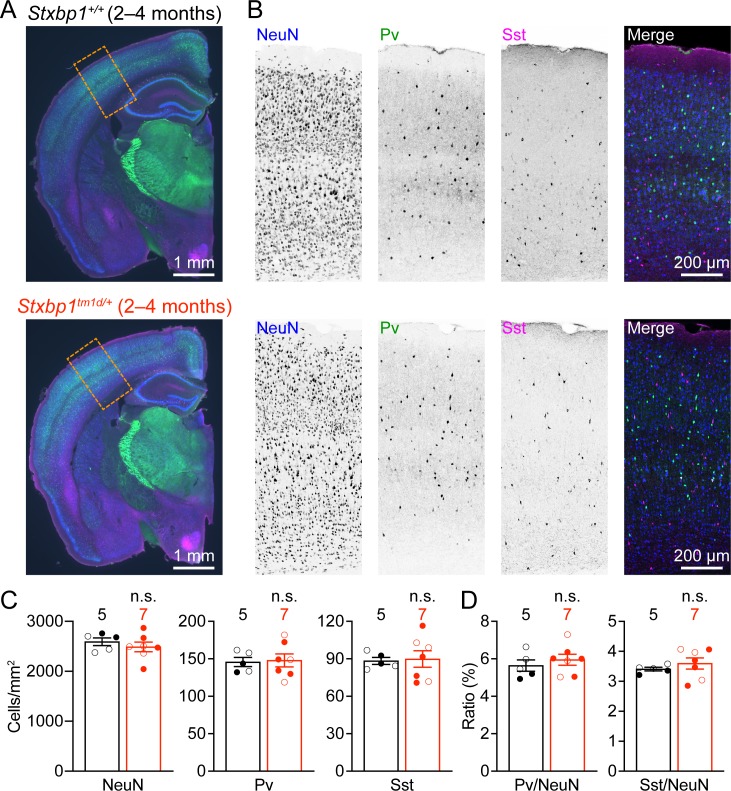

To identify cellular mechanisms that may underlie the cortical hyperexcitability and neurological deficits in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice, we first examined the general cytoarchitecture and neuronal densities in the somatosensory cortex, as Stxbp1 affects neuronal survival and migration (Verhage, 2000; Hamada et al., 2017). Immunostaining of a pan-neuronal marker NeuN revealed a grossly normal cytoarchitecture and cortical lamination in adult Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice (Figure 7A,B). The densities of cortical neurons and two major classes of inhibitory neurons, Pv and Sst interneurons, were similar between Stxbp1tm1d/+ and WT mice (Figure 7B–D). Thus, Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency does not appear to affect cortical neuron survival and migration.

Figure 7. Cortical neuron densities are unaltered in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice.

(A) Representative fluorescent images of coronal sections stained by antibodies against NeuN (blue), Pv (green), and Sst (magenta). Note the similar cytoarchitecture between WT (upper panel) and Stxbp1tm1d/+ (lower panel) mice. (B) Representative fluorescent images of the somatosensory cortices within the boxed regions in (A) for WT (upper panels) and Stxbp1tm1d/+ (lower panels) mice. (C) Summary data showing similar densities of neurons (i.e., NeuN positive cells), Pv, and Sst interneurons in the somatosensory cortices of WT and Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice. (D) Summary data showing that the ratios of Pv and Sst interneurons to all somatosensory cortical neurons are similar between WT and Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice. The numbers and ages of mice are indicated in the figures. Each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents one mouse. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. n.s., p>0.05.

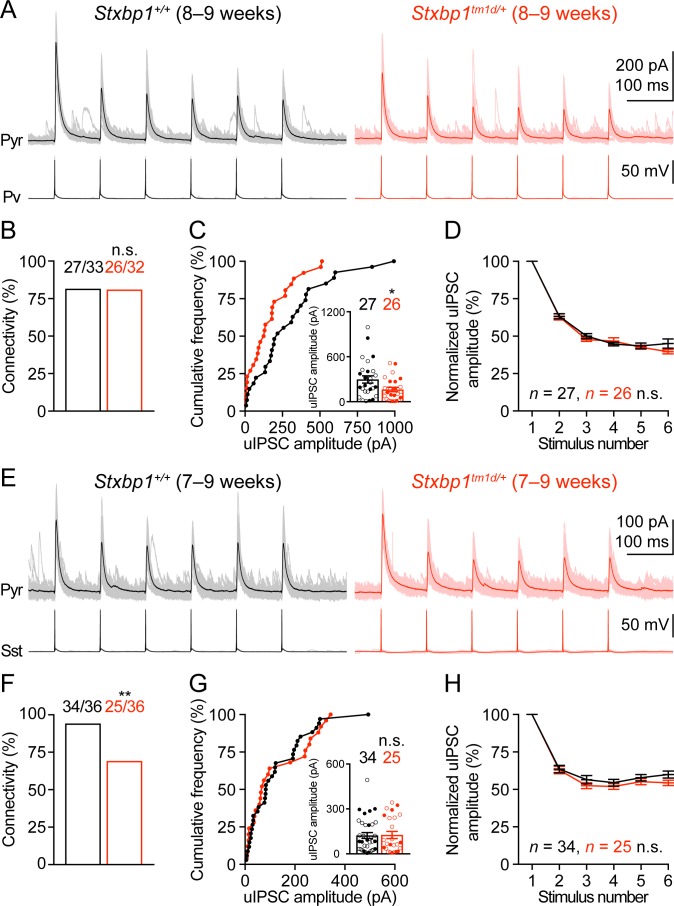

Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency reduces cortical inhibition in a synapse-specific manner

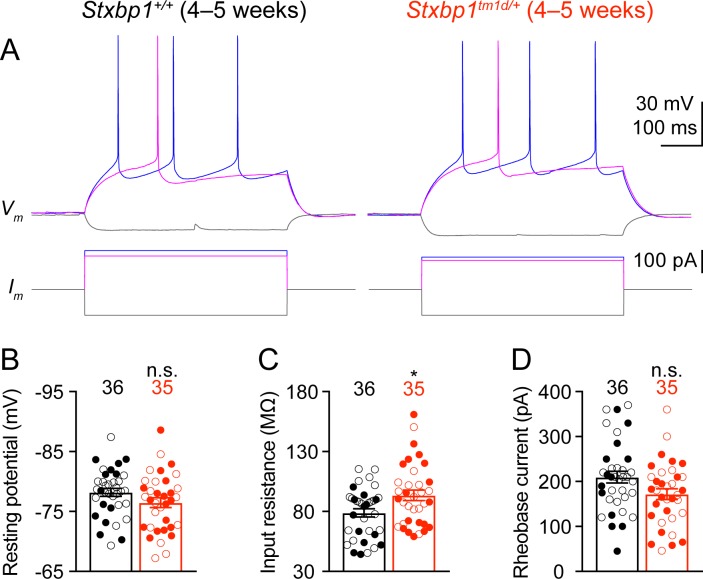

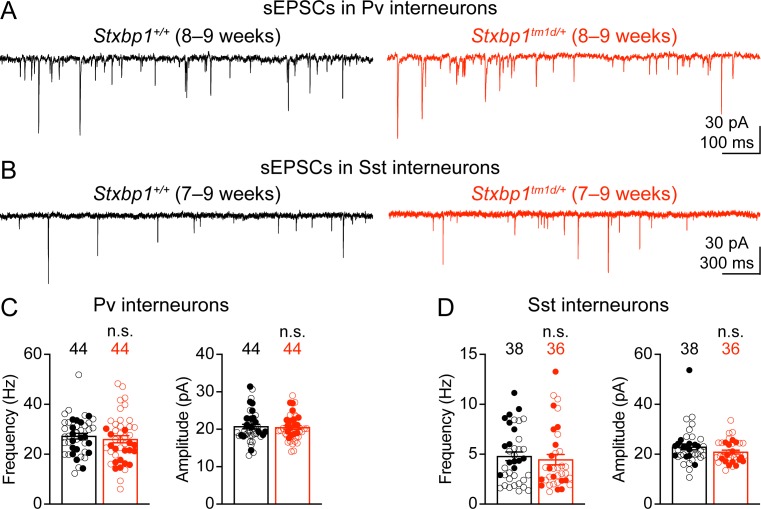

We next examined neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the somatosensory cortex. Whole-cell current clamp recordings of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in acute brain slices revealed only a small increase in the input resistances of Stxbp1tm1d/+ neurons as compared to WT neurons (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). Previous studies showed that synaptic transmission was reduced in the cultured hippocampal neurons from heterozygous Stxbp1 knockout mice and human neurons derived from heterozygous STXBP1 knockout embryonic stem cells (Toonen et al., 2006; Patzke et al., 2015; Orock et al., 2018). However, such a decrease in excitatory transmission onto excitatory neurons is probably inadequate to explain how Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency in vivo leads to cortical hyperexcitability. Genetic deletion of one copy of Stxbp1 from GABAergic neurons led to early lethality in a subset of mice, suggesting a crucial role of Stxbp1 in GABAergic neurons Kovacevic et al. (2018), but see Miyamoto et al. (2017) and Miyamoto et al. (2019). Thus, we focused on the inhibitory synaptic transmission originating from Pv and Sst interneurons. A Cre-dependent tdTomato reporter line, Rosa26-CAG-LSL-tdTomato (Madisen et al., 2010), and Pv-ires-Cre (Hippenmeyer et al., 2005) or Sst-ires-Cre (Taniguchi et al., 2011) were used to identify Pv or Sst interneurons, respectively. We used whole-cell current clamp to stimulate a single Pv or Sst interneuron in layer 2/3 with a brief train of action potentials and whole-cell voltage clamp to record the resulting unitary inhibitory postsynaptic currents (uIPSCs) in a nearby pyramidal neuron (Figure 8A,E). The connectivity rate of Pv interneurons to pyramidal neurons was unaltered in Stxbp1tm1d/+;Rosa26tdTomato/+;PvCre/+ mice (Figure 8B), but the unitary connection strength was reduced by 45% as compared to Stxbp1+/+;Rosa26tdTomato/+;PvCre/+ mice (Figure 8C). In contrast, Stxbp1tm1d/+;Rosa26tdTomato/+;SstCre/+ mice showed a 26% reduction in the connectivity rate of Sst interneurons to pyramidal neurons (Figure 8F), but the unitary connection strength was normal (Figure 8G). The short-term synaptic depression of both inhibitory connections during the train of stimulations was normal (Figure 8D,H). The inter-soma distances of interneurons and pyramidal neurons were similar between WT and mutant mice (Pv: WT 35.2 ± 2.4 μm, n = 33, mutant 33.2 ± 2.5 μm, n = 31, p=0.69; Sst: WT 31.4 ± 2.4 μm, n = 36, mutant 32.0 ± 2.1 μm, n = 36, p=0.65). Furthermore, we recorded the spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) in Pv and Sst interneurons and did not observe any significant changes of either amplitude or frequency in the mutant mice (Figure 8—figure supplement 2), suggesting that the excitatory drive onto interneurons is normal in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice.

Figure 8. Inhibitory synapses from Pv and Sst interneurons are differentially impaired in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice.

(A) uIPSCs of a layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron (Vm = + 10 mV) in the somatosensory cortex (upper panels) evoked by a train of 10 Hz action potentials in a nearby Pv interneuron (lower panels) from WT and Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice. 50 individual traces (lighter color) and the average trace (darker color) are superimposed. Note smaller uIPSCs in the Stxbp1tm1d/+ neuron. (B) Unitary connectivity rates from Pv interneurons to pyramidal neurons were similar between WT (27 connections out of 33 pairs) and Stxbp1tm1d/+ (26 connections out of 32 pairs) mice. (C) Cumulative frequencies of uIPSC amplitudes evoked by the first action potentials in the trains (median: WT, 217.3 pA; Stxbp1tm1d/+, 127.1 pA). Inset, each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents the uIPSC amplitude of one synaptic connection. (D) uIPSC amplitudes during the trains of action potentials were normalized by the amplitudes of the first uIPSCs. Note the similar synaptic depression between WT and Stxbp1tm1d/+ neurons. (E–H) Similar to (A–D), but for Sst interneurons. Unitary connectivity rates from Sst interneurons to pyramidal neurons (F) in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice (25 connections out of 36 pairs) were less than WT mice (34 connections out of 36 pairs). The uIPSC amplitudes evoked by the first action potentials in the trains (G, median: 83.5 pA and 68.0 pA, respectively) and synaptic depression (H) were similar between WT and Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice. The ages of mice are indicated in the figures. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. n.s., p>0.05; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

Figure 8—figure supplement 1. Intrinsic neuronal excitability of Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice is slightly increased.

Figure 8—figure supplement 2. Spontaneous excitatory inputs onto Pv and Sst interneurons are unaltered in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice.

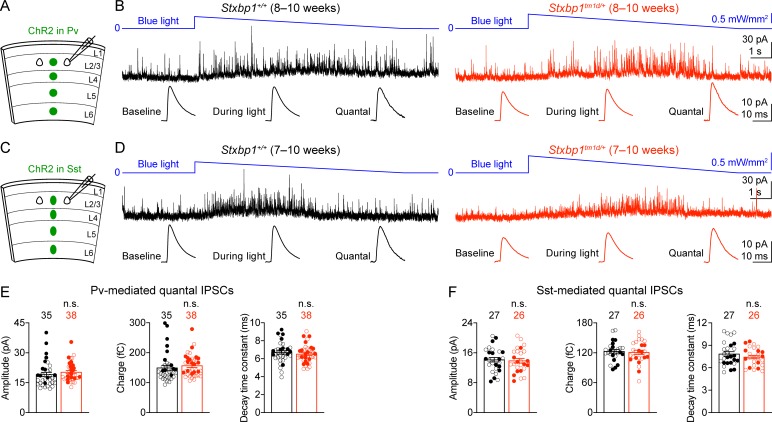

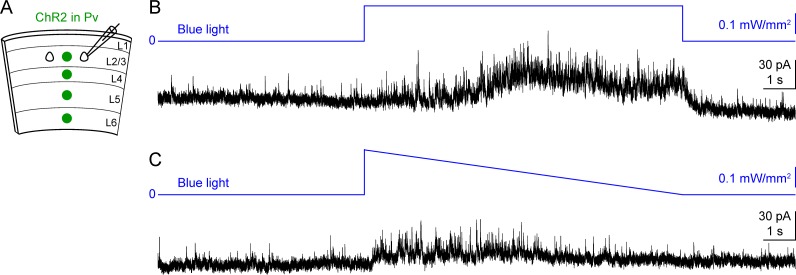

To determine the properties of quantal inhibitory transmission, we developed a new optogenetic method to isolate quantal IPSCs mediated by the GABA release specifically from Pv or Sst interneurons. We expressed a blue light-gated cation channel, channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) (Nagel et al., 2003; Boyden et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005), in Pv interneurons by injecting a Cre recombinase-dependent adeno-associated virus (AAV) into the somatosensory cortices of Stxbp1tm1d/+;PvCre/+ and Stxbp1+/+;PvCre/+ mice (Figure 9A). We recorded miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) from layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in the presence of voltage-gated sodium channel blocker, tetrodotoxin (TTX), but without any voltage-gated potassium channel blockers. Under such conditions light activation of ChR2 did not evoke synchronous neurotransmitter release, but could enhance asynchronous exocytosis of synaptic vesicles from Pv interneurons, resulting in an increase in the frequency of mIPSCs (Figure 9B). We also replaced the extracellular Ca2+ with Sr2+ to further reduce the likelihood of synchronous release. Instead of using a constant light intensity, we gradually decreased the photostimulation strength to minimize the tonic currents (Figure 9—figure supplement 1). We mathematically subtracted the mIPSCs recorded during the baseline period (i.e., before blue light stimulation) from those recorded during blue light stimulation to obtain the average amplitude, charge, and decay time constant of Pv interneurons-mediated quantal IPSCs (Figure 9B), which were all similar between Stxbp1tm1d/+;PvCre/+ and Stxbp1+/+;PvCre/+ mice (Figure 9E). Using this optogenetic method, we also found that the average amplitude, charge, and decay time constant of quantal IPSCs mediated by Sst interneurons were normal in Stxbp1tm1d/+;SstCre/+ mice (Figure 9C,D,F). Thus, Stxbp1 haploinsufficiency does not affect the postsynaptic properties of inhibitory transmission.

Figure 9. Pv and Sst interneurons-mediated quantal IPSCs are isolated by a novel optogenetic method and are unaltered in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice.

(A) Schematic of slice experiments in (B). ChR2 in Pv interneurons. (B) mIPSCs in a layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron (Vm = + 10 mV) from the somatosensory cortex of WT or Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice. The intensity of blue light is indicated above the mIPSC traces. Note the increase of mIPSC frequency during blue light stimulation. The quantal IPSC trace was computed by subtracting the average mIPSC trace of the baseline period from that of the light stimulation period (bottom row). (C,D) As in (A,B), but for ChR2 in Sst interneurons. (E,F) Summary data showing that the average amplitude, charge, and decay time constant of Pv (E) or Sst (F) interneuron-mediated quantal IPSCs are similar between WT and Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice. The numbers and ages of recorded neurons are indicated in the figures. Each filled (male) or open (female) circle represents one neuron. Bar graphs are mean ± s.e.m. n.s., p>0.05.

Figure 9—figure supplement 1. Ramping down blue light intensity minimizes the tonic currents during optogenetic activation of interneurons.

Altogether, our results indicate that the reduction in the strength of Pv interneuron synapses is most likely due to a decrease in the number of readily releasable vesicles or release probability because the quantal amplitude and connectivity are unaltered in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice. Since Sst interneuron density and overall neuron density are normal in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice (Figure 7), a reduction in the connectivity rate of Sst interneurons to pyramidal neurons suggests a decrease in the number of inhibitory inputs onto pyramidal neurons. Thus, cortical inhibition mediated by both Pv and Sst interneurons is impaired in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice, representing a likely cellular mechanism for the cortical hyperexcitability, seizures, and neurobehavioral deficits.

Discussion

Extensive biochemical and structural studies of Stxbp1/Munc18-1 have elucidated its crucial role in synaptic vesicle exocytosis (Rizo and Xu, 2015), but provided little insight into its functional role at the organism level. Hence, apart from being an essential gene, the significance of STXBP1 dysfunction in vivo was not appreciated until its de novo heterozygous mutations were discovered first in epileptic encephalopathies (Saitsu et al., 2008) and later in other neurodevelopmental disorders (Hamdan et al., 2009; Hamdan et al., 2011; Rauch et al., 2012; Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study, 2015). In this study, we generated two new lines of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice (Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+) and systematically characterized them in all of the neurologic and psychiatric domains affected by STXBP1 encephalopathy. These mice exhibit reduced survival, hindlimb clasping, impaired motor coordination, learning and memory deficits, hyperactivity, increased anxiety-like and repetitive behaviors, aggression, and epileptic seizures. Sensory abnormality has not been documented in STXBP1 encephalopathy patients (Stamberger et al., 2016) and we also did not observe any sensory dysfunctions in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice. Thus, despite the large phenotypic spectrum of STXBP1 encephalopathy in humans, our Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice recapitulate all key features of this neurodevelopmental disorder and are construct and face valid models of STXBP1 encephalopathy. Importantly, the identical phenotypes of Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice demonstrate the robustness and reproducibility of these preclinical models, providing a foundation to further study the disease pathogenesis and explore therapeutic strategies. About 17% of the STXBP1 encephalopathy patients showed autistic traits (Stamberger et al., 2016), but we and others (Miyamoto et al., 2017; Kovacevic et al., 2018) did not observe an impairment of social interaction in mutant mice using the three-chamber and partition tests. Perhaps the elevated aggression in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice confounds these tests, or new mouse models that more precisely mimic the genetic alterations in the subset of STXBP1 encephalopathy patients with autistic features are required to recapitulate this social behavioral phenotype.

Prior studies using the other three lines of Stxbp1 heterozygous knockout mouse models reported only a subset of the neurologic and psychiatric deficits that we observed here (Supplementary file 2). For example, the reduced survival, hindlimb clasping, motor dysfunction, and increased repetitive behavior were not documented in the previous models. The previously reported cognitive phenotypes were much milder than what we observed. Both Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice showed severe impairments in the novel objection recognition and fear conditioning tests. In contrast, another line of Stxbp1 heterozygous knockout mice showed normal spatial learning in the Morris water maze and Barnes maze (a dry version of the spatial maze) in one study (Kovacevic et al., 2018), but reduced spatial learning and memory in the radial arm water maze in another study (Orock et al., 2018). Different behavioral tests could have contributed to such differences among studies. However, a subtle but perhaps key difference is the Stxbp1 protein levels in different lines of heterozygous mutant mice. Stxbp1 is reduced by 40–50% in most brain regions of our Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice, but only by 25–50% in previous heterozygous knockout mice (Miyamoto et al., 2017; Orock et al., 2018), which may lead to fewer or less severe phenotypes. Furthermore, our study utilized much larger cohorts of mice for phenotypic characterization than previous studies, which allowed us to more comprehensively detect neurologic and psychiatric deficits in Stxbp1tm1d/+ and Stxbp1tm1a/+ mice.

Dysfunction of cortical GABAergic inhibition has been widely considered as a primary defect in animal models of autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, Down syndrome, and epilepsy among other neurological disorders (Ramamoorthi and Lin, 2011; Marín, 2012; Nelson and Valakh, 2015; Paz and Huguenard, 2015; Contestabile et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017). In many cases, the origins of GABAergic dysfunction were either unidentified or attributed to Pv interneurons. Sst interneurons have only been directly implicated in a few disease models (Ito-Ishida et al., 2015; Rubinstein et al., 2015) despite their important physiological functions. Here we identified distinct deficits at Pv and Sst interneuron synapses in Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice, suggesting that Stxbp1 may have diverse functions at distinct synapses. The reduction in the strength of Pv interneuron synapses is consistent with the previous results that basal synaptic transmission is reduced at the neuromuscular junctions of Stxbp1 heterozygous null flies and mice (Wu et al., 1998; Toonen et al., 2006) and the glutamatergic synapses of human STXBP1 heterozygous knockout neurons (Patzke et al., 2015). The reduced synaptic strength is likely due to a decrease in the number of readily releasable vesicles or release probability given the crucial role of Stxbp1 in synaptic vesicle priming and fusion (Rizo and Xu, 2015) and the fact that the quantal amplitude and connectivity are normal in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice. Although the short-term synaptic depression is unaltered in Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice, a change in release probability is still possible because at the Pv interneuron synapses the short-term synaptic plasticity during a short train of action potentials is not sensitive to the release probability (Kraushaar and Jonas, 2000; Luthi et al., 2001). On the other hand, the reduction in the connectivity of Sst interneuron synapses is unexpected, as Stxbp1 has not yet been implicated in the formation or maintenance of synapses. Complete loss of Stxbp1 in mice does not appear to affect the initial formation of neural circuits, but causes cell-autonomous neurodegeneration and protein trafficking defects (Verhage, 2000; Heeroma et al., 2004; Law et al., 2016). Since Munc13-1/2 double knockout mice also lack synaptic exocytosis, but do not show neurodegeneration (Varoqueaux et al., 2002), the degeneration phenotype in Stxbp1 null mice is unlikely the result of total arrest of synaptic exocytosis. Thus, Stxbp1 may regulate other intracellular processes in addition to presynaptic transmitter release, and we speculate that it may be involved in a protein trafficking process important for the formation or maintenance of Sst interneuron synapses. Future morphological and structural analyses of Sst interneuron synapses will be necessary to further confirm the involvement of Stxbp1 in synapse formation or maintenance. Nevertheless, the impairment of Pv and Sst interneuron-mediated inhibition likely constitutes a key mechanism underlying the cortical hyperexcitability and neurobehavioral phenotypes of Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice. Future studies using cell-type specific Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mouse models will help determine the role of specific GABAergic interneurons in the disease pathogenesis.

There are over one hundred developmental brain disorders that arise from mutations in postsynaptic proteins (Bayés et al., 2011; Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study, 2017), whereas few neurodevelopmental disorders have been diagnosed with mutations in presynaptic proteins until recently. In addition to STXBP1, pathogenic variants in genes encoding other key components of the presynaptic neurotransmitter release machinery have been increasingly discovered in neurodevelopmental disorders. These include Ca2+-sensor synaptotagmin 1 (SYT1), vesicle priming factor unc-13 homolog A (UNC13A), and all three components of the neuronal SNAREs, syntaxin 1B (STX1B), synaptosome associated protein 25 (SNAP25), and vesicle associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2) (Rohena et al., 2013; Schubert et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2014; Baker et al., 2015; Engel et al., 2016; Hamdan et al., 2017; Lipstein et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2018; Fukuda et al., 2018; Salpietro et al., 2019; Wolking et al., 2019). Haploinsufficiency of these synaptic proteins is likely the leading disease mechanism because the majority of the cases were caused by heterozygous loss-of-function mutations. The clinical features of these disorders are diverse, but significantly overlap with those of STXBP1 encephalopathy. The most common phenotypes are intellectual disability and epilepsy (or cortical hyperexcitability), which can be considered as the core features of these genetic synaptopathies. Thus, Stxbp1 haploinsufficient mice are a valuable model to understand the cellular and circuit origins of these complex disorders and provide mechanistic insights into the growing list of neurodevelopmental disorders caused by synaptic dysfunction.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource |

Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line (M. musculus) |

Stxbp1tm1a(EUCOMM)Hmgu embryonic stem cell clones (C57BL/6N strain) | European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM) | HEPD0510_5_A09, HEPD0510_5_B10 | |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | Stxbp1tm1a (C57BL/6J strain) | This paper | ||

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) |

Stxbp1tm1d (C57BL/6J strain) | This paper | ||

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID:IMSR_JAX:000058 | |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) |

Rosa26-Flpo (C57BL/6J strain) | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID:IMSR_JAX:012930 | |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | Sox2-Cre (C57BL/6J strain) | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID:IMSR_JAX:008454 | |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 | |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | Pv-ires-Cre (C57BL/6J strain) | The Jackson Laboratory |

RRID:IMSR_JAX:017320 | |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | Sst-ires-Cre (C57BL/6;129S4 strain) | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID:IMSR_JAX:013044 | |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | Rosa26-CAG-LSL-tdTomato (C57BL/6J strain) | The Jackson Laboratory |

RRID:IMSR_JAX:007914 | |

| Antibody | Rabbit anti-Munc18-1, polyclonal | Abcam, catalog # ab3451 | RRID:AB_303813 | (1:2000 or 1:5,000) |

| Antibody | Rabbit anti-Munc18-1, polyclonal | Synaptic Systems, catalog # 116002 | RRID:AB_887736 | (1:2000 or 1:5,000) |

| Antibody | Rabbit anti-Gapdh, polyclonal | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog #sc-25778 | RRID:AB_10167668 | (1:300 or 1:1,000) |

| Antibody | Goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with IRDye 680LT, polyclonal |

LI-COR Biosciences, catalog # 925–68021 | RRID:AB_2713919 | (1:20,000) |

| Antibody | Rabbit anti-Somatostatin, polyclonal | Peninsula Laboratories International, catalog # T4103.0050 |

RRID:AB_518614 | (1:3,000) |

| Antibody | Mouse anti-Parvalbumin, monoclonal | EMD Millipore, catalog # MAB1572 | RRID:AB_2174013 | (1:1,000) |

| Antibody | Guinea pig anti-NeuN, polyclonal | Sigma Millipore, catalog # ABN90 | RRID:AB_11205592 | (1:1,000) |

| Antibody | Goat anti-guinea pig IgG (H+L) conjugated with Alexa Flour 488, polyclonal |

Invitrogen, catalog # A-11073 | RRID:AB_2534117 | (1:1,000) |

| Antibody | Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) conjugated with Alexa Flour 555, polyclonal |

Invitrogen, catalog # A-21424 | RRID:AB_141780 | (1:1,000) |

| Antibody | Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) conjugated with Alexa Flour 647, polyclonal | Invitrogen, catalog # A-21245 | RRID:AB_141775 | (1:1,000) |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pAAV-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-P2A-EYFP | This paper | Addgene: 139283 | This plasmid was used to produce the AAV vector used in Figure 9. |

| Transfected construct | AAV9-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-P2A-EYFP | This paper, Baylor College of Medicine Gene Vector Core | Addgene: 139283 | This AAV vector was used in Figure 9. |

| Software, algorithm | Axograph X 1.5.4 | AxoGraph | RRID:SCR_014284 | https://axograph.com |

| Software, algorithm | pClamp 10.7 | Molecular Devices | RRID:SCR_011323 | https://www.moleculardevices.com |

| Software, algorithm | Image Studio Lite 5.0 | LI-COR Biosciences | RRID:SCR_013715 | https://www.licor.com |

| Software, algorithm | MATLAB R2015 to R2017 | MathWorks | RRID:SCR_001622 | https://www.mathworks.com |

| Software, algorithm | Prism 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0 | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 | https://www.graphpad.com |

| Software, algorithm | Spyder 3.3.6 with Anaconda | Spyder | RRID:SCR_017585 | https://www.spyder-ide.org |

| Software, algorithm | Sirenia 1.7.2 to 1.8.3 | Pinnacle Technology | RRID:SCR_016183 | https://www.pinnaclet.com |

| Software, algorithm | Imaris 9.2 | Oxford Instruments | RRID:SCR_007370 | https://imaris.oxinst.com |

Mice

Stxbp1tm1a(EUCOMM)Hmgu embryonic stem (ES) cell clones (C57Bl/6N strain) were obtained from the European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM) and the targeting was confirmed by Southern blots. Two ES cell clones (HEPD0510_5_A09 and HEPD0510_5_B10) were injected into blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. Germline transmission of clone HEPD0510_5_A09 was obtained by crossing chimeric mice to B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J mice (JAX #000058) to establish the KO-first (tm1a) line. Heterozygous KO-first mice were crossed to Rosa26-Flpo mice (Raymond and Soriano, 2007) to remove the trapping cassette in the germline. The resulting offspring were then crossed to Sox2-Cre mice (Hayashi et al., 2002) to delete exon seven in the germline to generate the KO (tm1d) line. Both Rosa26-Flpo and Sox2-Cre mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (#012930 and 008454, respectively). Stxbp1 mice were genotyped by PCR using primer sets 5’-TTCCACAGCCCTTTACAGAAAGG-3’ and 5’-ATGTGTATGCCTGGACTCACAGGG-3’ for WT allele, 5’-TTCCACAGCCCTTTACAGAAAGG-3’ and 5’-CAACGGGTTCTTCTGTTAGTCC-3’ for KO-first allele, and 5’-TTCCACAGCCCTTTACAGAAAGG-3’ and 5’-TGAACTGATGGCGAGCTCAGACC-3’ for KO allele.

Heterozygous Stxbp1 KO-first and KO mice were crossed to wild type (WT) C57BL/6J mice (JAX #000664) for maintaining both lines on the C57BL/6J background and for generating experimental cohorts. Male BALB/cAnNTac mice were obtained from Taconic (#BALB-M). Pv-ires-Cre (Hippenmeyer et al., 2005), Sst-ires-Cre (Taniguchi et al., 2011), and Rosa26-CAG-LSL-tdTomato (Madisen et al., 2010) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (#017320, 013044, and 007914, respectively). Pv-ires-Cre and Rosa26-CAG-LSL-tdTomato mice were maintained on the C57BL/6J background. Sst-ires-Cre mice were on a C57BL/6;129S4 background. Heterozygous KO mice were crossed to Rosa26-CAG-LSL-tdTomato mice to generate Stxbp1tm1d/+;Rosa26tdTomato/ tdTomato mice. Pv-ires-Cre and Sst-ires-Cre mice were then crossed to Stxbp1tm1d/+;Rosa26tdTomato/ tdTomato mice to generate Stxbp1tm1d/+;Rosa26tdTomato/+;PvCre/+ or Stxbp1+/+;Rosa26tdTomato/+;PvCre/+ and Stxbp1tm1d/+;Rosa26tdTomato/+;SstCre/+ or Stxbp1+/+;Rosa26tdTomato/+;SstCre/+ mice, respectively. Pv-ires-Cre and Sst-ires-Cre mice were also crossed to Stxbp1tm1d/+ mice to generate Stxbp1tm1d/+;PvCre/+ or Stxbp1+/+;PvCre/+ and Stxbp1tm1d/+;SstCre/+ or Stxbp1+/+;SstCre/+ mice, respectively.

Mice were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-certified animal facility on a 14 hr/10 hr light/dark cycle. All procedures to maintain and use mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine.

Southern and Western blots

Southern and Western blot analyses were performed according standard protocols. For Southern blots, genomic DNA was extracted from ES cells and digested with BspHI for the 5’ probe or MfeI for the 3’ probe (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). 32P-labeled probes were used to detect DNA fragments. For Western blots, proteins were extracted from the brains at embryonic day 17.5 or 3 months of age using lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 1 tablet of cOmplete, Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) in 10 ml buffer. Stxbp1 was detected by a rabbit antibody against the N terminal residues 58–70 (Abcam, catalog # ab3451, lot # GR79394-18, 1:2000 or 1:5000 dilution) or a rabbit antibody against the C terminal residues 580–594 (Synaptic Systems, catalog # 116002, lot # 116002/15, 1:2000 or 1:5000 dilution). Gapdh was detected by a rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog # sc-25778, lot # A0515, 1:300 or 1:1000 dilution). Primary antibodies were detected by a goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with IRDye 680LT (LI-COR Biosciences, catalog # 925–68021, lot # C40917-01, 1:20,000 dilution). Proteins were visualized and quantified using an Odyssey CLx Imager and Image Studio Lite 5.0 (LI-COR Biosciences).

Immunohistochemistry and fluorescent microscopy

Mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine and xylazine mix (80 mg/kg and 16 mg/kg, respectively) and transcardially perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4). Brains were then post-fixed for 2 hr in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose, and sectioned into 50 µm coronal slices using a HM 450 Sliding Microtome (Thermo Scientific). Brain sections were stored in an ethylene glycol:glycerol:PBS solution (1:1:1.3) until use. Sections containing the somatosensory cortex were incubated in blocking solution (0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS with 10% normal goat serum) for 2 hr and then with primary antibodies for 48 hr at 4°C. Primary antibodies were diluted in the blocking solution: rabbit anti-Somatostatin (Peninsula Laboratories International, catalog # T4103.0050, lot # A17908, 1:3000), mouse anti-Parvalbumin (EMD Millipore, catalog # MAB1572, lot # 2982272, 1:1000), and guinea pig anti-NeuN (Sigma Millipore, catalog # ABN90, lot # 3253333, 1:1000). Sections were washed in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS and then incubated with the following secondary antibodies diluted 1:1000 in blocking solution for 24 hr at 4°C: goat anti-guinea pig IgG (H+L) conjugated with Alexa Flour 488 (Invitrogen, catalog # A-11073, lot # 1841755), goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) conjugated with Alexa Flour 555 (Invitrogen, catalog # A-21424, lot # 1588453), goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) conjugated with Alexa Flour 647 (Invitrogen, catalog # A-21245, lot # 1623067). Sections were washed in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS and mounted in ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen, catalog # P36962).

Low magnification images of brain sections were acquired on an Axio Zoom.V16 Fluorescence Stereo Zoom Microscope (Zeiss). High magnification, tile scanned z-stack images of the primary somatosensory cortex were acquired on an Sp8X Confocal Microscope (Leica) using a 20 × oil objective. Three brain sections were imaged and quantified per mouse. Approximately 50 images were acquired per tile scan with a 5% overlap between images for tiling. The z-stack was centered in the middle of the brain section and 10 optical sections were taken at 0.39 μm step. For analysis, the three optical sections in the middle of the z-stack were processed using the ‘Sum Slices’ function in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) and then the images were cropped to a region of approximately 2 mm2 spanning all cortical layers. Within this region, each Pv or Sst interneuron was confirmed to be co-labeled with DAPI and NeuN and counted manually. The numbers of NeuN positive cells were estimated using the Surfaces function in Imaris 9.2 (Oxford Instruments) with the following parameters: surface grain size = 0.568 μm, eliminating background of largest sphere = 9 μm diameter, threshold = 30, seed point diameter = 7 μm, seed point quality = 10, and number of voxels < 200. Accuracy of surface detection was verified by manually counting NeuN positive cells in images containing about 200 cells and the error rate was less than 10%.

DNA construct, AAV production, and injection

Plasmid pAAV-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-P2A-EYFP was generated by replacing the hChR2(C128A H134R) in pAAV-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(C128A H134R)-P2A-EYFP (Prakash et al., 2012) with the hChR2(H134R) from pAAV-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP (Addgene #20298) and was deposited at Addgene (#139283). The recombinant AAV vectors were produced by the Gene Vector Core at Baylor College of Medicine. To express ChR2 in Pv or Sst interneurons, 200 nl of AAV9-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-P2A-EYFP vectors (3 × 1013 genome copies/ml) were injected into the somatosensory cortex of Stxbp1tm1d/+;PvCre/+ and Stxbp1+/+;PvCre/+ or Stxbp1tm1d/+;SstCre/+ and Stxbp1+/+;SstCre/+ mice, respectively, at postnatal day 1–5 as previously described (Xue et al., 2014; Messier et al., 2018) with an UltraMicroPump III and a Micro4 controller (World Precision Instruments).

Behavioral tests

All behavioral experiments except the tube test were performed and analyzed blind to the genotypes. The numbers of mice needed were estimated based on previous studies using similar behavioral tests. Approximately equal numbers of Stxbp1 mutant mice and their sex- and age-matched WT littermates of both sexes were tested in parallel in each experiment except the resident-intruder test where only male mice were used. In each cage, two mutant and two WT mice were housed together. Before all behavioral tests, mice were habituated in the behavioral test facility for at least 30 min. The sexes and ages of the tested mice were indicated in the figures.

Open-field test

A mouse was placed in the center of a clear, open chamber (40 × 40 × 30 cm) and allowed to freely explore for 30 min in the presence of 700–750 lux illumination and 65 dB background white noise. In each chamber, two layers of light beams (16 for each layer) in the horizontal X and Y directions capture the locomotor activity of the mouse. The horizontal plane was evenly divided into 256 squares (16 × 16), and the center zone is defined as the central 100 squares (10 × 10). The horizontal travel and vertical activity were quantified by either an Open Field Locomotor system or a VersaMax system (OmniTech).

Rotarod test

A mouse was placed on an accelerating rotarod apparatus (Ugo Basile). Each trial lasted for a maximum of 5 min, during which the rod accelerated linearly from 4 to 40 revolutions per minute (RPM) or 8 to 80 RPM. The time when the mouse walks on the rod and the latency for the mouse to fall from the rod were recorded for each trial. Mice were tested in four trials per day for two consecutive days or in three trials per day for four consecutive days. There was a 30–60 min resting interval between trials.

Dowel test

A mouse was placed in the center of a horizontal dowel (6.5 mm or 9.5 mm diameter) and the latency to fall was measured with a maximal cutoff time of 120 s.

Inverted screen test

A mouse was placed onto a wire grid, and the grid was carefully picked up and shaken a couple of times to ensure that the mouse was holding on. The grid was then inverted such that the mouse was hanging upside down from the grid. The latency to fall was measured with a maximal cutoff time of 60 s.

Wire hang test

A mouse was suspended by its forepaws on a 1.5 mm wire and the latency to fall was recorded with a maximal cutoff time of 60 s.

Foot slip test

A mouse was placed onto an elevated 40 × 25 cm wire grid (1 × 1 cm spacing) and allowed to freely move for 5 min. The number of foot slips was manually counted, and the moving distance was measured through a video camera (ANY-maze, Stoelting). The number of foot slips were normalized by the moving distance for each mouse.

Vertical pole test

A mouse was placed head-upward at the top of a vertical threaded metal pole (1.3 cm diameter, 55 cm length). The amount of time for the mouse to turn around and descend to the floor was measured with a maximal cutoff time of 120 s.

Grip strength

Forelimb grip strength was measured using a Grip Strength Meter (Columbus Instruments). A mouse was held by the tail and allowed to grasp a trapeze bar with its forepaws. Once the mouse grasped the bar with both paws, the mouse was pulled away from the bar until the bar was released. The digital meter displayed the level of tension exerted on the bar in gram-force (gf).

Acoustic startle response test

A mouse was placed in a well-ventilated, clear plastic cylinder and acclimated to the 70 dB background white noise for 5 min. The mouse was then tested with four blocks. Each block consisted of 13 trials, during which each of 13 different levels of sound (70, 74, 78, 82, 86, 90, 94, 98, 102, 106, 110, 114, or 118 dB, 40 ms, inter-trial interval of 15 s on average) was presented in a pseudorandom order. The startle response was recorded for 40 ms after the onset of the sound. The rapid force changes due to the startles were measured by an accelerometer (SR-LAB, San Diego Instruments).

Pre-pulse inhibition test

A mouse was placed in a well-ventilated, clear plastic cylinder and acclimated to the 70 dB background noise for 5 min. The mouse was then tested with six blocks. Each block consisted of 8 trials in a pseudorandom order: a ‘no stimulus’ trial (40 ms, only 70 dB background noise present), a test pulse trial (40 ms, 120 dB), three different pre-pulse trials (20 ms, 74, 78, or 82 dB), and three different pre-pulse inhibition trials (a 20-ms, 74, 78, or 82-dB pre-pulse preceding a 40-ms, 120-dB test pulse by 100 milliseconds). The startle response was recorded for 40 ms after the onset of the 120 dB test pulse. The inter-trial interval is 15 s on average. The rapid force changes due to the startles were measured by an accelerometer (SR-LAB, San Diego Instruments). Pre-pulse inhibition of the startle responses was calculated as ‘1 – (pre-pulse inhibition trial/test pulse trial)'.

Hot plate test

A mouse was placed on a hot plate (Columbus Instruments) with a constant temperature of 55°C. The latency for the mouse to first respond with either a hind paw lick, hind paw flick, or jump was measured. If the mouse did not respond within 45 s, then the test was terminated, and the latency was considered to be 45 s.

Novel object recognition test

A mouse was first habituated in an empty arena (24 × 45 × 20 cm) for 5 min before every trial. The habituated mouse was then placed into the testing arena with two identical objects (i.e., familiar object 1 and familiar object 2) for the first three trials. In the fourth trial, familiar object 1 was replaced with a novel object.. In the fifth trial, the mouse was presented with the two original, identical objects again. Each trial lasted 5 min. The inter-trial interval was 24 hr or 5 min. In the modified version, Stxbp1tm1d/+ and WT mice were exposed to the objects for 10 and 5 min during each trial, respectively. The movement of mice was recorded by a video camera placed above the test arena. The amount of time that the mouse interacted with the objects (T) was recorded using a wireless keyboard (ANY-maze, Stoelting). The preference index of interaction was calculated as Tfamiliar object 1 /(Tfamiliar object 1 + Tfamiliar object 2) for the first three trials and fifth trial and as Tnovel object/(Tnovel object + Tfamiliar object 2) for the fourth trial.

Fear conditioning test

Pavlovian fear conditioning was conducted in a chamber (30 × 25 × 29 cm) that has a grid floor for delivering electrical shocks (Coulbourn Instruments). A camera above the chamber was used to monitor the mouse. During the 5 min training phase, a mouse was placed in the chamber for 2 min, and then a sound (85 dB, white noise) was turned on for 30 s immediately followed by a mild foot shock (2 s, 0.72 mA). The same sound and foot shock were repeated one more time 2 min after the first foot shock. After the second foot shock, the mouse stayed in the training chamber for 18 s before returning to its home cage. After 1 or 24 hr, the mouse was tested for the contextual and cued fear memories. In the contextual fear test, the mouse was placed in the same training chamber and its freezing behavior was monitored for 5 min without the sound stimulus. The mouse was then returned to its home cage. One to two hours later, the mouse was transferred to the chamber after it has been altered using plexiglass inserts and a different odor to create a new context for the cued fear test. After 3 min in the chamber, the same sound cue that was used in the training phase was turned on for 3 min without foot shocks while the freezing behavior was monitored. The freezing behavior was scored using an automated video-based system (FreezeFrame, Actimetrics). The freezing time (%) during the first 2 min of the training phase (i.e., before the first sound) was subtracted from the freezing time (%) during the contextual fear test. The freezing time (%) during the first 3 min of the cued fear test (i.e., without sound) was subtracted from the freezing time (%) during the last 3 min of the cued fear test (i.e., with sound).

Y maze spontaneous alternation test

A mouse was placed in the center of a Y-shaped maze consisting of three walled arms (35 × 5 × 10 cm) and allowed to freely explore the different arms for 10 min. The sequence of the arms that the mouse entered was recorded using a video camera (ANY-maze, Stoelting). The correct choice refers to when the mouse entered an alternate arm after it came out of one arm.

Elevated plus maze test

A mouse was placed in the center of an elevated maze consisting of two open arms (25 × 8 cm) and two closed arms with high walls (25 × 8 × 15 cm). The mouse was initially placed facing the open arms and then allowed to freely explore for 10 min in the presence of 700–750 lux illumination and 65 dB background white noise. The mouse activity was recorded using a video camera (ANY-maze, Stoelting).

Light-dark chamber test

A mouse was placed in a rectangular light-dark chamber (44 × 21 × 21 cm) and allowed to freely explore for 10 min in the presence of 700–750 lux illumination and 65 dB background white noise. One third of the chamber is made of black plexiglass (dark) and two thirds is made of clear plexiglass (light) with a small opening between the two areas. The movement of the mouse was tracked by the Open Field Locomotor system (OmniTech).

Hole-board test

A mouse was placed at the center of a clear chamber (40 × 40 × 30 cm) that contains a black floor with 16 evenly spaced holes (5/8-inch diameter) arranged in a 4 × 4 array. The mouse was allowed to freely explore for 10 min. Its open-field activity above the floorboard and nose pokes into the holes were detected by infrared beams above and below the hole board, respectively, using the VersaMax system (OmniTech).

Resident-intruder test

Male test mice (resident mice) were individually caged for 2 weeks before testing. Age-matched male white BALB/cAnNTac mice (Taconic) were group-housed to serve as the intruders. During the test, an intruder was placed into the home cage of a test mouse for 10 min and their behaviors were video recorded. Videos were scored for the number and duration of each attack by the resident mouse regardless the attack was initiated by either the resident or intruder.

Tube test

A pair of a mutant mouse and an age- and sex-matched WT mouse that were housed in different home cages were placed into the opposite ends of a clear acrylic, cylindrical tube (3.5 cm diameter). The mouse that retreats backwards first was considered as the loser. The winner was scored as 1 and the loser as 0. Each mutant mouse was tested against three different WT mice and the scores were averaged.

Three-chamber test