3D-bioprinted microenvironment directs MSC differentiation and promotes SG regeneration.

Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) encapsulation by three-dimensionally (3D) printed matrices were believed to provide a biomimetic microenvironment to drive differentiation into tissue-specific progeny, which made them a great therapeutic potential for regenerative medicine. Despite this potential, the underlying mechanisms of controlling cell fate in 3D microenvironments remained relatively unexplored. Here, we bioprinted a sweat gland (SG)–like matrix to direct the conversion of MSC into functional SGs and facilitated SGs recovery in mice. By extracellular matrix differential protein expression analysis, we identified that CTHRC1 was a critical biochemical regulator for SG specification. Our findings showed that Hmox1 could respond to the 3D structure activation and also be involved in MSC differentiation. Using inhibition and activation assay, CTHRC1 and Hmox1 synergistically boosted SG gene expression profile. Together, these findings indicated that biochemical and structural cues served as two critical impacts of 3D-printed matrix on MSC fate decision into the glandular lineage and functional SG recovery.

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) hold great promise for therapeutic tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, largely because of their capacity for self-renewal and multipotent properties (1). However, their uncertain fate has a major impact on their envisioned therapeutic use. Cell fate regulation requires specific transcription programs in response to environmental cues (2, 3). Once stem cells are removed from their microenvironment, their response to environmental cues, phenotype, and functionality could often be altered (4, 5). In contrast to growing information concerning transcriptional regulation, guidance from the extracellular matrix (ECM) governing MSC identity and fate determination is not well understood. It remains an active area of investigation and may provide previously unidentified avenues for MSC-based therapy.

Over the past decade, engineering three-dimensional (3D) ECM to direct MSC differentiation has demonstrated great potential of MSCs in regenerative medicine (6). 3D ECM has been found to be useful in providing both biochemical and biophysical cues and to stabilize newly formed tissues (7). Culturing cells in 3D ECM radically alters the interfacial interactions with the ECM as compared with 2D ECM, where cells are flattened and may lose their differentiated phenotype (8). However, one limitation of 3D materials as compared to 2D approaches was the lack of spatial control over chemistry with 3D materials. One possible solution to this limitation is 3D bioprinting, which could be used to design the custom scaffolds and tissues (9).

In contrast to traditional engineering techniques, 3D cell printing technology is especially advantageous because it can integrate multiple biophysical and biochemical cues spatially for cellular regulation and ensure complex structures with precise control and high reproducibility. In particular, for our final goal of clinical practice, extrusion-based bioprinting may be more appropriate for translational application. In addition, as a widely used bioink for extrusion bioprinting, alginate-based hydrogel could maintain stemness of MSC due to the bioinert property and improve biological activity and printability by combining gelatin (10).

Sweat glands (SGs) play a vital role in thermal regulation, and absent or malfunctioning SGs in a hot environment can lead to hyperthermia, stroke, and even death in mammals (11, 12). Each SG is a single tube consisting of a functionally distinctive duct and secretory portions. It has low regenerative potential in response to deep dermal injury, which poses a challenge for restitution of lost cells after wound (13). A major obstacle in SG regeneration, similar to the regeneration of most other glandular tissues, is the paucity of viable cells capable of regenerating multiple tissue phenotypes (12). Several reports have described SG regeneration in vitro; however, dynamic morphogenesis was not identified nor was the overall function of the formed tissues explored (14–16). Recent advances in bioprinting and tissue engineering led to the complexities in the matrix design and fabrication with appropriate biochemical cues and biophysical guidance for SG regeneration (17–19).

Here, we adopted 3D bioprinting technique to mimic the regenerative microenvironment that directed the specific SG differentiation of MSCs and ultimately guided the formation and function of glandular tissue. We used alginate/gelatin hydrogel as bioinks in this present study due to its good cytocompatibility, printability, and structural maintenance in long-time culture. Although the profound effects of ECM on cell differentiation was well recognized, the importance of biochemical and structural cues of 3D-printed matrix that determined the cell fate of MSCs remained unknown; thus, the present study demonstrated the role of 3D-printed matrix cues on cellular behavior and tissue morphogenesis and might help in developing strategies for MSC-based tissue regeneration or directing stem cell lineage specification by 3D bioprinting.

RESULTS

3D-printed microenvironment promotes cell aggregation and proliferation

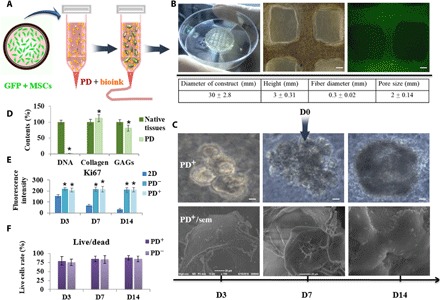

The procedure for printing the 3D MSC-loaded construct incorporating a specific SG ECM (mouse plantar region dermis, PD) was shown schematically in Fig. 1A. A 3D cellular construct with cross section 30 mm × 30 mm and height of 3 mm was fabricated by using the optimized process parameter (20). The 3D construct demonstrated a macroporous grid structure with hydrogel fibers evenly distributed according to the computer design. Both the width of the fibers and the gap between the fibers were homogeneous, and MSCs were embedded uniformly in the hydrogel matrix fibers to result in a specific 3D microenvironment. (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of 3D-bioprinted MSC-loaded constructs and cellular survival, proliferation, and morphology of printed construct.

(A) Schematic description of the approach. (B) Full view of the cellular construct and representative microscopic and fluorescent images and the quantitative parameters of 3D-printed construct (scale bars, 200 μm). Photo credit: Bin Yao, Wound Healing and Cell Biology Laboratory, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, General Hospital of PLA. (C) Representative microscopy images of cell aggregates and tissue morphology at 3, 7, and 14 days of culture (scale bars, 50 μm) and scanning electron microscopy (sem) images of 3D structure (scale bars, 20 μm). PD+/PD−, 3D construct with and without PD. (D) DNA contents, collagen, and GAGs of native tissue and PD. (E) Proliferating cells were detected through Ki67 stain at 3, 7, and 14 days of culture. (F) Live/dead assay show cell viability at days 3, 7, and 14. *P < 0.05.

During the maintenance of constructs for stem cell expansion, MSCs proliferated to form aggregates of cells but self-assembled to an SG-like structure only with PD administration (Fig. 1C and fig. S1, A to C). We carried out DNA quantification assay to evaluate the cellular content in PD and found the cellular matrix with up to 90% reduction, only 3.4 ± 0.7 ng of DNA per milligram tissue remaining in the ECM. We also estimated the proportions of collagen and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in ECM through hydroxyproline assay and dimethylmethylene blue assay, the collagen contents could increase to 112.6 ± 11.3%, and GAGs were well retained to 81 ± 9.6% (Fig. 1D). Encapsulated cells were viable, with negligible cell death apparent during extrusion and ink gelation by ionic cross-linking, persisting through extended culture in excess of 14 days. The fluorescence intensity of Ki67 of MSCs cultured in 2D condition decreased from days 3 (152.7 ± 13.4) to 14 (29.4 ± 12.9), while maintaining higher intensity of MSCs in 3D construct (such as 211.8 ± 19.4 of PD+3D group and 209.1 ± 22.1 of PD−3D group at day 14). And the cell viability in 3D construct was found to be sufficiently high (>80%) when examined on days 3, 7, and 14. The phenomenon of cell aggregate formation and increased cell proliferation implied the excellent cell compatibility of the hydrogel-based construct and promotion of tissue development of 3D architectural guides, which did not depend on the presence or absence of PD (Fig. 1, E and F).

3D-printed microenvironments with PD direct SG differentiation of MSCs in vitro

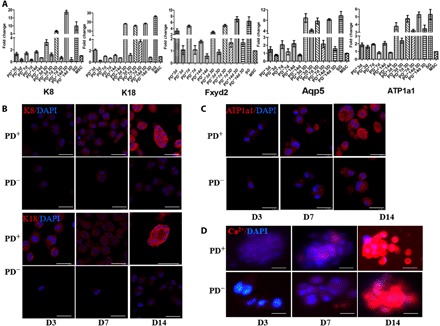

The capability of 3D-printed construct with PD directing MSC to SGs in vitro was investigated. The 3D construct was dissolved, and cells were isolated at days 3, 7, and 14 for transcriptional analysis. Expression of the SG markers K8 and K18 was higher from the 3D construct with (3D/PD+) than without PD (3D/PD−); K8 and K18 expression in the 3D/PD− construct was similar to with control that MSCs cultured in 2D condition, which implied the key role of PD in SG specification. As compared with the 2D culture condition, 3D administration (PD+) up-regulated SG markers, which indicated that the 3D structure synergistically boosted the MSC differentiation (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Transcriptional and translational level of SG-specific and secretion-related markers in 3D-bioprinted cells with or without PD.

(A) Transcriptional expression of K8, K18, Fxyd2, Aqp5, and ATP1a1 in 3D-bioprinted cells with and without PD in days 3, 7, and 14 culture by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Data are means ± SEM. (B) Comparison of SG-specific markers K8 and K18 in 3D-bioprinted cells with and without PD (K8 and K18, red; DAPI, blue; scale bars, 50 μm). (C and D) Comparison of SG secretion-related markers ATP1a1 (C) and Ca2+ (D) in 3D-bioprinted cells with and without PD [ATP1a1 and Ca2+, red; 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), blue; scale bars, 50 μm].

In addition, we tested secretion-related genes to evaluate the function of induced SG cells (iSGCs). Although levels of the ion channel factors of Fxyd2 and ATP1a1 were increased notably in 2D culture with PD and ATP1a1 up-regulated in the 3D/PD− construct, all the secretory genes of Fxyd2, ATP1a1, and water transporter Aqp5 showed the highest expression level in the 3D/PD+ construct (Fig. 2A). Considering the remarkable impact, further analysis focused on 3D constructs.

Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the progression of MSC differentiation. At day 7, cells in the 3D/PD+ construct began to express K8 and K18, which was increased at day 14, whereas cells in the 3D/PD− construct did not express K8 and K18 all the time (Fig. 2B and fig. S2A). However, the expression of ATP1a1 (ATPase Na+/K+ transporting subunit alpha 1) and free Ca2+ concentration did not differ between cells in the 3D/PD+ and 3D/PD− constructs (Fig. 2, C and D). By placing MSCs in such a 3D environment, secretion might be stimulated by rapid cell aggregation without the need for SG lineage differentiation. Cell aggregation–improved secretion might be due to the benefit of cell-cell contact (fig. S2B) (21, 22).

3D-printed microenvironment facilitates a sequential MET-EMT transition during differentiation

To map the cell fate changes during the differentiation between MSCs and SG cells, we monitored the mRNA levels of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin, occludin, Id2, and Mgat3 and mesenchymal markers N-cadherin, vimentin, Twist1, and Zeb2. The cells transitioned from a mesenchymal status to a typical epithelial-like status accompanied by mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), then epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) occurred during the further differentiation of epithelial lineages to SG cells (fig. S3A). In addition, MET-related genes were dynamically regulated during the SG differentiation of MSCs. For example, the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin were down-regulated from days 1 to 7, which suggested cells losing their mesenchymal phenotype, then were gradually up-regulated from days 7 to 10 in their response to the SG phenotype and decreased at day 14. The epithelial markers E-cadherin and occludin showed an opposite expression pattern: up-regulated from days 1 to 5, then down-regulated from days 7 to 10 and up-regulated again at day 14. The mesenchymal transcriptional factors ZEB2 and Twist1 and epithelial transcriptional factors Id2 and Mgat3 were also dynamically regulated.

We further analyzed the expression of these genes at the protein level by immunofluorescence staining (figs. S3B and S4). N-cadherin was down-regulated from days 3 to 7 and reestablished at day 14, whereas E-cadherin level was increased from days 3 to 7 and down-regulated at day 14. Together, these results indicated that a sequential and dynamic MET-EMT process underlie the differentiation of MSCs to an SG phenotype, perhaps driving differentiation more efficiently (23). However, the occurrence of the MET-EMT process did not depend on the presence of PD. Thus, a 3D structural factor might also participate in the MSC-specific differentiation (fig. S3C).

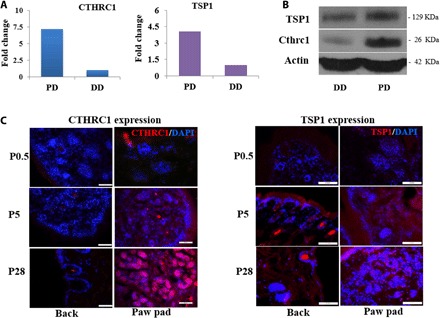

CTHRC1 is differentially expressed in SG-specific ECM

To investigate the underlying mechanism of biochemical cues in lineage-specific cell fate, we used quantitative proteomics analysis to screen the ECM factors differentially expressed between PD and dorsal region dermis (DD) because mice had eccrine SGs exclusively present in the pads of their paws, and the trunk skin lacks SGs. In total, quantitative proteomics analyses showed higher expression levels of 291 proteins in PD than DD. Overall, 66 were ECM factors: 23 were significantly up-regulated (>2-fold change in expression). We initially determined the level of proteins with the most significant difference after removing keratins and fibrin: collagen triple helix repeat containing 1 (CTHRC1) and thrombospondin 1 (TSP1) (fig. S5). Western blotting was performed to further confirm the expression level of CTHRC1 and TSP1, and we then confirmed that immunofluorescence staining at different developmental stages in mice revealed increased expression of CTHRC1 in PD with SG development but only slight expression in DD at postnatal day 28, while TSP1 was continuously expressed in DD and PD during development (Fig. 3, A to C). Therefore, TSP1 was required for the lineage-specific function during the differentiation in mice but was not dispensable for SG development.

Fig. 3. Expression of CTHRC1 in different ECM.

(A and B) Differential expression of CTHRC1 and TSP1in PD and back dermis (DD) ECM of mice by proteomics analysis (A) and Western blotting (B). (C) CTHRC1 and TSP1 expression in back and plantar skin of mice at different developmental times. (Cthrc1/TSP1, red; DAPI, blue; scale bars, 50 μm).

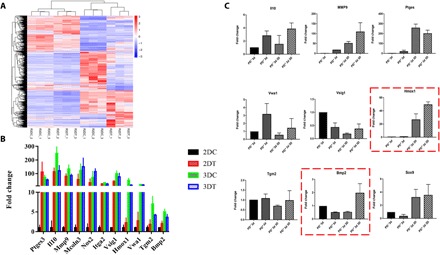

Hmox1 response to 3D structure cues involved in cell differentiation

According to previous results of the changes of SG markers, 3D structure and PD were both critical to SG fate. Then, we focused on elucidating the mechanisms that underlie the significant differences observed in 2D and 3D conditions with or without PD treatment. To this end, we performed transcriptomics analysis of MSCs, MSCs treated with PD, MSCs cultured in 3D construct, and MSC cultured in 3D construct with PD after 3-day treatment. We noted that the expression profiles of MSCs treated with 3D, PD, or 3D/PD were distinct from the profiles of MSCs (Fig. 4A). Through Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes, it was shown that PD treatment in 2D condition induced up-regulation of ECM and inflammatory response term, and the top GO term for MSCs in 3D construct was ECM organization and extracellular structure organization. However, for the MSCs with 3D/PD treatment, we found very significant overrepresentation of GO term related to branching morphogenesis of an epithelial tube and morphogenesis of a branching structure, which suggested that 3D structure cues and biochemical cues synergistically initiate the branching of gland lineage (fig S6). Heat maps of differentially expressed ECM organization, cell division, gland morphogenesis, and branch morphogenesis-associated genes were shown in fig. S7. To find the specific genes response to 3D structure cues facilitating MSC reprogramming, we analyzed the differentially expressed genes of four groups of cells (Fig. 4B). The expression of Vwa1, Vsig1, and Hmox1 were only up-regulated with 3D structure stimulation, especially the expression of Hmox1 showed a most significant increase and even showed a higher expression addition with PD, which implied that Hmox1 might be the transcriptional driver of MSC differentiation response to 3D structure cues. Differential expression of several genes was confirmed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR): Mmp9, Ptges, and Il10 were up-regulated in all the treated groups. Likewise, genes involving gland morphogenesis and branch morphogenesis such as Bmp2, Tgm2, and Sox9 showed higher expression in 3D/PD-treated group. Bmp2 was up-regulated only in 3D/PD-treated group, combined with the results of GO analysis, we assumed that Bmp2 initiated SG fate through inducing branch morphogenesis and gland differentiation (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. The transcriptional analysis of four groups of cells revealed the specific gene response to 3D structure.

(A) Gene expression file of four groups of cells (R2DC, MSCs; R2DT, MSC with PD treatment; R3DC, MSC cultured in 3D construct; and R3DT, MSC treated with 3D/PD). (B) Up-regulated genes after treatment (2DC, MSCs; 2DT, MSC with PD treatment; 3DC, MSC cultured in 3D construct; and 3DT, MSC treated with 3D/PD). (C) Differentially expressed genes were further validated by RT-PCR analysis. [For all RT-PCR analyses, gene expression was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) with 40 cycles, data are represented as the means ± SEM, and n = 3].

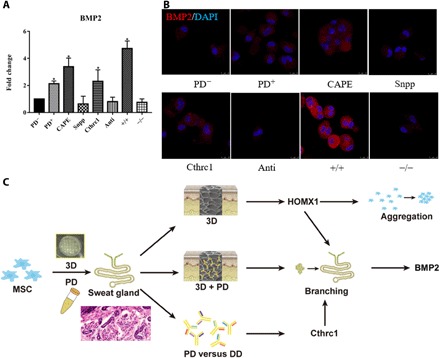

Essential role of HMOX1 and CTHRC1 in SG commitment

To validate the role of HMOX1 and CTHRC1 in the differentiation of MSCs to SG lineages, we analyzed the gene expression of Bmp2 by regulating the expression of Hmox1 and CTHRC1 based on the 3D/PD-treated MSCs. The effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) and tin protoporphyrin IX dichloride (Snpp) on the expression of Hmox1 were evaluated by quantitative real-time (qRT)–PCR. Hmox1 expression was significantly activated by CAPE and reduced by Snpp. Concentration of CTHRC1 was increased with recombinant CTHRC1 and decreased with CTHRC1 antibody. That is, it was negligible of the effects of activator and inhibitor of Hmox1 and CTHRC1 on cell proliferation (fig. S8, A and B). Hmox1 inhibition or CTHRC1 neutralization could significantly reduce the expression of Bmp2, while Hmox1 activation or increased CTHRC1 both activated Bmp2 expression. Furthermore, Bmp2 showed highest expression by up-regulation of Hmox1 and CTHRC1 simultaneously and sharply decreased with down-regulation of Hmox1 and CTHRC1 at the same time (Fig. 5A). Immunofluorescent staining revealed that the expression of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) at the translational level with CTHRC1 and Hmox1 regulation showed a similar trend with transcriptional changes (Fig. 5B). Likewise, the expression of K8 and K18 at transcriptional and translational level changed similarly with CTHRC1 and Hmox1 regulation (fig. S9, A and B). These results suggested that CTHRC1 and Hmox1 played an essential role in SG fate separately, and they synergistically induced SG direction from MSCs (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. CTHRC1 and HMOX1 synergistically boost SG fate of MSC.

(A and B) Transcriptional analysis (A) and translational analysis (PD−, MSCs; PD+, MSCs with 3D/PD treatment; CAPE, MSCs treated with 3D/PD and Hmox1 activator; Snpp, MSCs treated with 3D/PD and Hmox1 inhibitor; Cthrc1, MSCs treated with 3D/PD and recombinant CTHRC1; anti, MSCs treated with 3D/PD and CTHRC1 antibody: +/+, MSCs treated with 3D/PD and Hmox1 activator and recombinant CTHRC1; and −/−, MSCs treated with 3D/PD and Hmox1 inhibitor and CTHRC1 antibody. Data are represented as the means ± SEM and n = 3) (B) of bmp2 with regulation of CTHRC1 and Hmox1. (C) The graphic illustration of 3D-bioprinted matrix directed MSC differentiation. CTHRC1 is the main biochemical cues during SG development, and structural cues up-regulated the expression of Hmox1 synergistically initiated branching morphogenesis of SG. *P < 0.05.

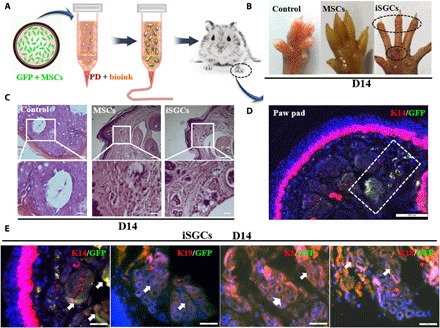

ISGCs led to directed functional regeneration of SG

Next, we sought to assess the repair capacity of iSGCs for in vivo implications, the 3D-printed construct with green fluorescent protein (GFP)–labeled MSCs was transplanted in burned paws of mice (Fig. 6A). We measured the SG repair effects by iodine/starch-based sweat test at day 14. Only mice with 3D/PD treatment showed black dots on foot pads (representing sweating), and the number increased within 10 min; however, no black dots were observed on untreated and single MSC-transplanted mouse foot pads even after 15 min (Fig. 6B). Likewise, hematoxylin and eosin staining analysis revealed SG regeneration in 3D/PD-treated mice (Fig. 6C). GFP-positive cells were characterized as secretory lumen expressing K8, K18, and K19. Of note, the GFP-positive cells were highly distributed in K14-positive myoepithelial cells of SGs but were absent in K14-positive repaired epidermal wounds (Fig. 6, D and E). Thus, differentiated MSCs enabled directed restitution of damaged SG tissues both at the morphological and functional level.

Fig. 6. Directed regeneration of SG in thermal-injured mouse model after transplantation of iSGCs.

(A) Schematic illustration of approaches for engineering iSGCs and transplantation. (B) Sweat test of mice treated with different cells. Photo credit: Bin Yao, Wound Healing and Cell Biology Laboratory, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, General Hospital of PLA. (C) Histology of plantar region without treatment and transplantation of MSCs and iSGCs (scale bars, 200 μm). (D) Involvement of GFP-labeled iSGCs in directed regeneration of SG tissue in thermal-injured mouse model (K14, red; GFP, green; DAPI, blue; scale bar, 200 μm). (E) SG-specific markers K14, K19, K8, and K18 detected in regenerated SG tissue (arrows). (K14, K19, K8, and K18, red; GFP, green; scale bars, 50 μm).

DISCUSSION

A potential gap in MSC-based therapy still exists between current understandings of MSC performance in vivo in their microenvironment and their intractability outside of that microenvironment (24). To regulate MSCs differentiation into the right phenotype, an appropriate microenvironment should be created in a precisely controlled spatial and temporal manner (25). Recent advances in innovative technologies such as bioprinting have enabled the complexities in the matrix design and fabrication of regenerative microenvironments (26). Our findings demonstrated that directed differentiation of MSCs into SGs in a 3D-printed matrix both in vitro and in vivo was feasible. In contrast to conventional tissue-engineering strategies of SG regeneration, the present 3D-printing approach for SG regeneration with overall morphology and function offered a rapid and accurate approach that may represent a ready-to-use therapeutic tool.

Furthermore, bioprinting MSCs successfully repaired the damaged SG in vivo, suggesting that it can improve the regenerative potential of exogenous differentiated MSCs, thereby leading to translational applications. Notably, the GFP-labeled MSC-derived glandular cells were highly distributed in K14-positive myoepithelial cells of newly formed SGs but were absent in K14-positive repaired epidermal wounds. Compared with no black dots were observed on single MSC-transplanted mouse foot pads, the black dots (representing sweating function) can be observed throughout the entire examination period, and the number increased within 10 min on MSC-bioprinted mouse foot pads. Thus, differentiated MSCs by 3D bioprinting enabled exclusive restitution of damaged SG tissues morphologically and functionally.

Although several studies indicated that engineering 3D microenvironments enabled better control of stem cell fates and effective regeneration of functional tissues (27–30), there were no studies concerning the establishment of 3D-bioprinted microenvironments that can preferentially induce MSCs differentiating into glandular cells with multiple tissue phenotypes and overall functional tissue. To find an optimal microenvironment for promoting MSC differentiation into specialized progeny, biochemical properties are considered as the first parameter to ensure SG specification. In this study, we used mouse PD as the main composition of a tissue-specific ECM. As expected, this 3D-printed PD+ microenvironment drove the MSC fate decision to enhance the SG phenotypic profile of the differentiated cells. By ECM differential protein expression analysis, we identified that CTHRC1 was a critical biochemical regulator of 3D-printed matrix for SG specification. TSP1 was required for the lineage-specific function during the differentiation in mice but was not dispensable for SG development. Thus, we identified CTHRC1 as a specific factor during SG development. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of CTHRC1 involvement in dictating MSC differentiation to SG, highlighting a potential therapeutic tool for SG injury.

The 3D-printed matrix also provided architectural guides for further SG morphogenesis. Our results clearly show that the 3D spatial dimensionality allows for better cell proliferation and aggregation and affect the characteristics of phenotypic marker expression. Notably, the importance of 3D structural cues on MSC differentiation was further proved by MET-EMT process during differentiation, where the influences did not depend on the presence of biochemical cues. To fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms, we first examined how 3D structure regulating stem cell fate choices. According to our data, Hmox1 is highly up-regulated in 3D construct, which were supposed to response to hypoxia, with a previously documented role in MSC differentiation (31, 32). It is suggested that 3D microenvironment induced rapid cell aggregation leading to hypoxia and then activated the expression of Hmox1.

Through regulation of the expression of Hmox1 and addition or of CTHRC1 in the matrix, we confirmed that each of them is critical for SG reprogramming, respectively. Thus, biochemical and structural cues of 3D-printed matrix synergistically creating a microenvironment could enhance the accuracy and efficiency of MSC differentiation, thereby leading to resulting SG formation. Although we further need a more extensive study examining the role of other multiple cues and their possible overlap function in regulating MSC differentiation, our findings suggest that CTHRC1 and Hmox1 provide important signals that cooperatively modulate MSC lineage specification toward sweat glandular lineage. The 3D structure combined with PD stimulated the GO functional item of branch morphogenesis and gland formation, which might be induce by up-regulation of Bmp2 based on the verification of qPCR results. Although our results could not rule out the involvement of other factors and their possible overlapping role in regulating MSC lineage specification toward SGs, our findings together with several literatures suggested that BMP2 plays a critical role in inducing branch morphogenesis and gland formation (33–35).

In summary, our findings represented a novel strategy of directing MSC differentiation for functional SG regeneration by using 3D bioprinting and pave the way for a potential therapeutic tool for other complex glandular tissues as well as further investigation into directed differentiation in 3D conditions. Specifically, we showed that biochemical and structural cues of 3D-printed matrix synergistically direct MSC differentiation, and our results highlighted the importance of 3D-printed matrix cues as regulators of MSC fate decisions. This avenue opens up the intriguing possibility of shifting from genetic to microenvironmental manipulations of cell fate, which would be of particular interest for clinical applications of MSC-based therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The main aim and design of the study was first to determine whether by using 3D-printed microenvironments, MSCs can be directed to differentiate and regenerate SGs both morphologically and functionally. Then, to investigate the underlying molecular mechanism of biochemical and structural cues of 3D-printed matrix involved in MSCs reprogramming. The primary aims of the study design were as follows: (i) cell aggregation and proliferation in a 3D-bioprinted construct; (ii) differentiation of MSCs at the cellular phenotype and functional levels in the 3D-bioprinted construct; (iii) the MET-EMT process during differentiation; (iv) differential protein expression of the SG niche in mice; (v) differential genes expression of MSCs in 3D-bioprinted construct; (vi) the key role of CTHRC1 and HMOX1 in MSCs reprogramming to SGCs; and (vii) functional properties of regenerated SG in vivo.

Material preparation

Gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and sodium alginate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 15 and 1% (w/v), respectively. Both solutions were sterilized under 70°C for 30 min three times at an interval of 30 min. The sterilized solutions were packed into 50-ml centrifuge tubes, stored at 4°C, and incubated at 37°C before use.

Dermal homogenates extraction

From wild-type C57/B16 mice (Huafukang Co., Beijing) aged 5 days old, dermal homogenates were prepared by homogenizing freshly collected hairless mouse PD with isotonic phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 20 min in an ice bath to obtain 25% (w/v) tissue suspension. The supernatant was obtained after centrifugation at 4°C for 20 min at 10,000g. The DNA content was determined using Hoechst 33258 assay (Beyotime, Beijing). The fluorescence intensity was measured to assess the amount of remaining DNA within the decellularized ECMs and the native tissue using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Evolution 260 Bio, USA). The GAGs content was estimated via 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue solution staining. The absorbance was measured with microplate reader at wavelength of 492 nm. The standard curve was made using chondroitin sulfate A. The total COL (Collagen) content was determined via hydroxyproline assay. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 550 nm and quantified by referring to a standard curve made with hydroxyproline.

Bioprinting and culture of 3D MSC-loaded hydrogel construct

MSCs were bioprinted with matrix materials by using an extrusion-based 3D bioprinter (Regenovo Co., Bio-Architect PRO, Hangzhou). Briefly, 10 ml of gelatin solution (10% w/v) and 5 ml of alginate solution (2% w/v) were warmed under 37°C for 20 min, gently mixed as bioink and used within 30 min. MSCs were collected from 100-mm dishes, dispersed into single cells, and 200 μl of cell suspension was gently mixed with matrix material under room temperature with cell density 1 million ml−1. PD (58 μg/ml) was then gently mixed with bioink. Petri dishes at 60 mm were used as collecting plates in the 3D bioprinting process. Within a temperature-controlled chamber of the bioprinter, with temperature set within the gelation region of gelatin, the mixture of MSCs and matrix materials was bioprinted into a cylindrical construct layer by layer. The nozzle-insulation temperature and printing chamber temperature were set at 18° and 10°C, respectively; nozzles with an inner diameter of 260 μm were chosen for printing. The diameter of the cylindrical construct was 30 mm, with six layers in height. After the temperature-controlled bioprinting process, the printed 3D constructs were immersed in 100-mM calcium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 3 min for cross-linking, then washed with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA) medium for three times. The whole printing process was finished in 10 min. The 3D cross-linked construct was cultured in DMEM in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. The culture medium was changed to SG medium [contains 50% DMEM (Gibco, New York, NY) and 50% F12 (Gibco) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (Gibco), 1 ml/100 ml penicillin-streptomycin solution, 2 ng/ml liothyronine sodium (Gibco), 0.4 μg/ml hydrocortisone succinate (Gibco), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 1 ml/100 ml insulin-transferrin-selenium (Gibco)] 2 days later. The cell morphology was examined and recorded under an optical microscope (Olympus, CX40, Japan).

Live/dead assay

Fluorescent live/dead staining was used to determine cell viability in the 3D cell-loaded constructs according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Briefly, samples were gently washed in PBS three times. An amount of 1 μM calcein acetoxymethyl (calcein AM) ester (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 2 μM propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was used to stain live cells (green) and dead cells (red) for 15 min while avoiding light. A laser scanning confocal microscopy system (Leica, TCSSP8, Germany) was used for image acquisition.

Immunohistology

The cell-printed structure was harvested and fixed with a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde. The structure was embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and sectioned 10-mm thick by using a cryotome (Leica, CM1950, Germany). The sliced samples were washed repeatedly with PBS solution to remove OCT compound and then permeabilized with a solution of 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in PBS for 5 min. To reduce nonspecific background, sections were treated with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution in PBS for 20 min. To visualize iSGCs, sections were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C for anti-K8 (1:300), anti-K14 (1:300), anti-K18 (1:300), anti-K19 (1:300), anti-ATP1a1 (1:300), anti-Ki67 (1:300), anti–N-cadherin (1:300), anti–E-cadherin (1:300), anti-CTHRC1 (1:300), or anti-TSP1 (1:300; all Abcam, UK) and then incubated with secondary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature: Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit (1:300), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) goat anti-rabbit (1:300), FITC goat anti-mouse (1:300), or Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse (1:300; all Invitrogen, CA). Sections were also stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Beyotime, Beijing) for 15 min. Stained samples were visualized, and images were captured under a confocal microscope.

Cell harvesting

To harvest the cells in the construct, the 3D constructs were dissolved by adding 55 mM sodium citrate and 20 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in 150 mM sodium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 5 min while gently shaking the petri dish for better dissolving. After transfer to 15-ml centrifuge tubes, the cell suspensions were centrifuged at 200 rpm for 3 min, and the supernatant liquid was removed to harvest cells for further analysis.

Gene expression analysis by reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration was measured by using a NanoPhotometer (Implen GmbH, P-330-31, Germany). Reverse transcription involved use of a complementary DNA synthesis kit (Takara, China). Gene expression was analyzed quantitatively by using SYBR green with the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Takara, China). The primers and probes for genes were designed on the basis of published gene sequences (table S1) (National Center for Biotechnology Information and PubMed). The expression of each gene was normalized to that for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and analyzed by the 2-△△CT method. Each sample was assessed in triplicate.

Detection of free intracellular Ca2+ concentration

The culture medium was changed to SG medium with 2 mM CaCl2 for at least 24 hours, and cells were loaded with fluo-3/AM (Invitrogen, CA) at a final concentration of 5 μM for 30 min at room temperature. After three washes with calcium-free PBS, 10 μM acetylcholine (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to cells. The change in the Fluo 3 fluorescent signal was recorded under a laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated through CCK-8 (Cell counting kit-8) assay. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at the appropriate concentration and cultured at 37°C in an incubator for 4 hours. When cells were adhered, 10 μl of CCK-8 working buffer was added into the 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Tecan, SPARK 10M, Austria).

Proteomics analysis

Proteomics of mouse PD and DD involved use of isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) in BGI Company, with differentially expressed proteins detected in PD versus DD. Twofold greater difference in expression was considered significant for further study.

Western blot analysis

Tissues were grinded and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Beyotime, Nanjing). Proteins were separated by 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a methanol-activated polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (GE Healthcare, USA). The membrane was blocked for 1 hour in PBS with Tween 20 containing 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and probed with the antibodies anti-CTHRC1 (1:1000) and anti-TSP1 (1:1000; both Abcam, UK) overnight at 4°C. After 2 hours of incubation with goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), the protein bands were detected by using luminal reagent (GE Healthcare, ImageQuant LAS 4000, USA).

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was prepared with TRIzol (Invitrogen), and RNA sequencing was performed using HiSeq 2500 (Illumina). Genes with false discovery rate < 0.05, fold difference > 2.0, and mean log intensity > 2.0 were considered to be significant.

Inhibition and activation assay

CAPE or Snpp was gently mixed with bioink at a concentration of 10 μM. Physiological concentration of CTHRC1 was measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (80 ng/ml), and then recombinant CTHRC1 or CTHRC1 antibody was added into the bioink at a concentration of 0.4 μg/ml. The effect of inhibitor and activator was estimated by qRT-PCR or ELISA.

Burn model establishment

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and received subcutaneous buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) preoperatively. Full-thickness scald injuries were created on paw pads with soldering station (Weller, WSD81, Germany). Mice recovered in clean cages with paper bedding to prevent irritation or infection. Mice were monitored daily and euthanized at 30 days after wounding. Mice were maintained in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care–accredited animal facility, and procedures were performed with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee–approved protocols.

Transplantation of mouse iSGCs

MSCs in 3D-printed constructs with PD were cultured with DMEM for 2 days and then replaced with SG medium. The SG medium was changed every 2 days, and cells were harvested on day 12. The K18+ iSGCs were sorting through flow cytometry and injected into the paw pads (1 × 106 cells/50 μl) of the mouse burn model by using Microliter syringes (Hamilton, 7655-01, USA). Then, mice were euthanized after 14 days; feet were excised and fixed with 10% formalin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) overnight for paraffin sections and immunohistological analysis.

Sweat test

The foot pads of anesthetized treated mice were first painted with 2% (w/v) iodine/ethanol solution then with starch/castor oil solution (1 g/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). After drying, 50 μl of 100 μM acetylcholine (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was injected subcutaneously into paws of mice. Pictures of the mouse foot pads were taken after 5, 10, and 15 min.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism7 statistical software (GraphPad, USA). Significant differences were calculated by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Bonferroni test when performing multiple comparisons between groups. P < 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant difference.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported in part by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81571909, 81701906, 81830064, and 81721092), the National Key Research Development Plan (2017YFC1103300), Military Logistics Research Key Project (AWS17J005), and Fostering Funds of Chinese PLA General Hospital for National Distinguished Young Scholar Science Fund (2017-JQPY-002). Author contributions: B.Y. and S.H. were responsible for the design and primary technical process, conducted the experiments, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. Y.W. and R.W. helped perform the main experiments. Y.Z. and T.H. participated in the 3D printing. W.S. and Z.L. participated in cell experiments and postexamination. S.H. and X.F. collectively oversaw the collection of data and data interpretation and revised the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/10/eaaz1094/DC1

Fig. S1. Biocompatibility of 3D-bioprinted construct and cellular morphology in 2D monolayer culture.

Fig. S2. Expression of SG-specific and secretion-related markers in MSCs and SG cells in vitro.

Fig. S3. Transcriptional and translational expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in 3D-bioprinted cells with and without PD.

Fig. S4. Expression of N- and E-cadherin in MSCs and SG cells in 2D monolayer culture.

Fig. S5. Proteomic microarray assay of differential gene expression between PD and DD ECM in postnatal mice.

Fig. S6. GO term analysis of differentially expressed pathways.

Fig. S7. Heat maps illustrating differential expression of genes implicated in ECM organization, cell division, and gland and branch morphogenesis.

Fig. S8. The expression of Hmox1 and the concentration of CTHRC1 on treatment and the related effects on cell proliferation.

Fig. S9. The expression of K8 and K18 with Hmox1 and CTHRC1 regulation.

Table S1. Primers for qRT-PCR of all the genes.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Keating A., Mesenchymal stromal cells: New directions. Cell Stem Cell 10, 709–716 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu Z., Jiang K., Xu Z., Huang H., Qian N., Lu Z., Chen D., Di R., Yuan T., Du Z., Xie W., Lu X., Li H., Chai R., Yang Y., Zhu B., Kunieda T., Wang F., Chen T., Hoxc-dependent mesenchymal niche heterogeneity drives regional hair follicle regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 23, 487–500.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu Z., Wang W., Jiang K., Yu Z., Huang H., Wang F., Zhou B., Chen T., Embryonic attenuated Wnt/β-catenin signaling defines niche location and long-term stem cell fate in hair follicle. eLife 4, e10567 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu C. P., Polak L., Rocha A. S., Pasolli H. A., Chen S. C., Sharma N., Blanpain C., Fuchs E., Identification of stem cell populations in sweat glands and ducts reveals roles in homeostasis and wound repair. Cell 150, 136–150 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferraris C., Chevalier G., Favier B., Jahoda C. A., Dhouailly D., Adult corneal epithelium basal cells possess the capacity to activate epidermal, pilosebaceous and sweat gland genetic programs in response to embryonic dermal stimuli. Development 127, 5487–5495 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pati F., Jang J., Ha D. H., Won Kim S., Rhie J. W., Shim J. H., Kim D. H., Cho D. W., Printing three-dimensional tissue analogues with decellularized extracellular matrix bioink. Nat. Commun. 5, 3935 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnelly H., Salmeron-Sanchez M., Dalby M. J., Designing stem cell niches for differentiation and self-renewal. J. R. Soc. Interface 15, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y., Kilian K. A., Bridging the gap: From 2D cell culture to 3D microengineered extracellular Matrices. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 4, 2780–2796 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferlin K. M., Prendergast M. E., Miller M. L., Kaplan D. S., Fisher J. P., Influence of 3D printed porous architecture on mesenchymal stem cell enrichment and differentiation. Acta Biomater. 32, 161–169 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang J., Park J. Y., Gao G., Cho D. W., Biomaterials-based 3D cell printing for next-generation therapeutics and diagnostics. Biomaterials 156, 88–106 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheshire W. P., Freeman R., Disorders of sweating. Semin.Neurol. 23, 399–406 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu C., Fuchs E., Sweat gland progenitors in development, homeostasis, and wound repair. Cold Spring Harb.Perspect. Med. 4, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao B., Xie J., Liu N., Yan T., Li Z., Liu Y., Huang S., Fu X., Identification of a new sweat gland progenitor population in mice and the role of their niche in tissue development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 479, 670–675 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shikiji T., Minami M., Inoue T., Hirose K., Oura H., Arase S., Keratinocytes can differentiate into eccrine sweat ducts in vitro: Involvement of epidermal growth factor and fetal bovine serum. J. Dermatol. Sci. 33, 141–150 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H., Li X., Zhang M., Chen L., Zhang B., Tang S., Fu X., Three-dimensional co-culture of BM-MSCs and eccrine sweat gland cells in Matrigel promotes transdifferentiation of BM-MSCs. J. Mol. Histol. 46, 431–438 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang S., Yao B., Xie J., Fu X., 3D bioprinted extracellular matrix mimicsfacilitate directed differentiation of epithelial progenitors for sweat glandregeneration. Acta Biomater. 33, 170–177 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarker M. D., Naghieh S., McInnes A. D., Schreyer D. J., Chen X., Regeneration of peripheral nerves by nerve guidance conduits: Influence of design, biopolymers, cells, growth factors, and physical stimuli. Prog. Neurobiol. 171, 125–150 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chouhan D., Dey N., Bhardwaj N., Mandal B. B., Emerging and innovative approaches for wound healing and skin regeneration: Current status and advances. Biomaterials 216, 119267 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koffler J., Zhu W., Qu X., Platoshyn O., Dulin J. N., Brock J., Graham L., Lu P., Sakamoto J., Marsala M., Chen S., Tuszynski M. H., Biomimetic 3D-printed scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair. Nat. Med. 25, 263–269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu N., Huang S., Yao B., Xie J., Wu X., Fu X., 3D bioprinting matrices with controlled pore structure and release function guide in vitro self-organization of sweat gland. Sci. Rep. 6, 34410 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lecomte M. J., Pechberty S., Machado C., Da Barroca S., Ravassard P., Scharfmann R., Czernichow P., Duvillié B., Aggregation of engineered human β-cells into pseudoislets: Insulin secretion and gene expression profile in normoxic and hypoxic milieu. Cell Med. 8, 99–112 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins C. A., Chen J. C., Cerise J. E., Jahoda C. A. B., Christiano A. M., Microenvironmental reprogramming by three-dimensional culture enables dermal papilla cells to induce de novo human hair-follicle growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 19679–19688 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q., Hutchins A. P., Chen Y., Li S., Shan Y., Liao B., Zheng D., Shi X., Li Y., Chan W. Y., Pan G., Wei S., Shu X., Pei D., A sequential EMT-MET mechanism drives the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells towards hepatocytes. Nat. Commun. 8, 15166 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukhamedshina Y. O., Gracheva O. A., Mukhutdinova D. M., Chelyshev Y. A., Rizvanov A. A., Mesenchymal stem cells and the neuronal microenvironment in the area of spinal cord injury. Neural Regen. Res. 14, 227–237 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leijten J., Seo J., Yue K., Santiago G. T., Tamayol A., Ruiz-Esparza G. U., Shin S. R., Sharifi R., Noshadi I., Álvarez M. M., Zhang Y. S., Khademhosseini A., Spatially and Temporally Controlled Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Mater Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 119, 1–35 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bishop E. S., Mostafa S., Pakvasa M., Luu H. H., Lee M. J., Wolf J. M., Ameer G. A., He T. C., Reid R. R., 3-D bioprinting technologies in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: Current and future trends. Genes Dis. 4, 185–195 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uz M., Das S. R., Ding S., Sakaguchi D. S., Claussen J. C., Mallapragada S. K., Advances in Controlling Differentiation of Adult Stem Cells for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7, e1701046 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thrivikraman G., Boda S. K., Basu B., Unraveling the mechanistic effects of electric field stimulation towards directing stem cell fate and function: A tissue engineering perspective. Biomaterials 150, 60–86 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moroni L., Burdick J. A., Highley C., Lee S. J., Morimoto Y., Takeuchi S., Yoo J. J., Biofabrication strategies for 3D in vitro models and regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Mater. 3, 21–37 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandrycky C., Wang Z., Kim K., Kim D. H., 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnol. Adv. 34, 422–434 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanella L., Sodhi K., Kim D. H., Puri N., Maheshwari M., Hinds T. D., Bellner L., Goldstein D., Peterson S. J., Shapiro J. I., Abraham N. G., Increased heme-oxygenase 1 expression in mesenchymal stem cell-derived adipocytes decreases differentiation and lipid accumulation via upregulation of the canonical Wnt signaling cascade. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 4, 28 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vanella L., Sanford Jr C., Kim D. H., Abraham N. G., Ebraheim N., Oxidative stress and heme oxygenase-1 regulated human mesenchymal stem cells differentiation. Int. J. Hypertens. 2012, 890671 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pispa J., Thesleff I., Mechanisms of ectodermal organogenesis. Dev. Biol. 262, 195–205 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu C. P., Polak L., Keyes B. E., Fuchs E., Spatiotemporal antagonism in mesenchymal-epithelial signaling in sweat versus hair fate decision. Science 354, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song L. L., Cui Y., Yu S. J., Liu P. G., Liu J., Yang X., He J. F., Zhang Q., Expression characteristics of BMP2, BMPR-IA and Noggin in different stages of hair follicle in yak skin. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 260, 18–24 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/10/eaaz1094/DC1

Fig. S1. Biocompatibility of 3D-bioprinted construct and cellular morphology in 2D monolayer culture.

Fig. S2. Expression of SG-specific and secretion-related markers in MSCs and SG cells in vitro.

Fig. S3. Transcriptional and translational expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in 3D-bioprinted cells with and without PD.

Fig. S4. Expression of N- and E-cadherin in MSCs and SG cells in 2D monolayer culture.

Fig. S5. Proteomic microarray assay of differential gene expression between PD and DD ECM in postnatal mice.

Fig. S6. GO term analysis of differentially expressed pathways.

Fig. S7. Heat maps illustrating differential expression of genes implicated in ECM organization, cell division, and gland and branch morphogenesis.

Fig. S8. The expression of Hmox1 and the concentration of CTHRC1 on treatment and the related effects on cell proliferation.

Fig. S9. The expression of K8 and K18 with Hmox1 and CTHRC1 regulation.

Table S1. Primers for qRT-PCR of all the genes.