Abstract

Background

Screening for Barrett’s Oesophagus (BE) relies on endoscopy which is invasive and has a low yield. This study aimed to develop and externally validate a simple symptom and risk-factor questionnaire to screen for patients with BE.

Methods

Questionnaires from 1299 patients in the BEST2 case-controlled study were analysed: 880 had BE including 40 with invasive oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) and 419 were controls. This was randomly split into a training cohort of 776 patients and an internal validation cohort of 523 patients. External validation included 398 patients from the BOOST case-controlled study: 198 with BE (23 with OAC) and 200 controls. Identification of independently important diagnostic features was undertaken using machine learning techniques information gain (IG) and correlation based feature selection (CFS). Multiple classification tools were assessed to create a multi-variable risk prediction model. Internal validation was followed by external validation in the independent dataset.

Findings

The BEST2 study included 40 features. Of these, 24 added IG but following CFS, only 8 demonstrated independent diagnostic value including age, gender, smoking, waist circumference, frequency of stomach pain, duration of heartburn and acid taste and taking of acid suppression medicines. Logistic regression offered the highest prediction quality with AUC (area under the receiver operator curve) of 0.87. In the internal validation set, AUC was 0.86. In the BOOST external validation set, AUC was 0.81.

Interpretation

The diagnostic model offers valid predictions of diagnosis of BE in patients with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, assisting in identifying who should go forward to invasive testing. Overweight men who have been taking stomach medicines for a long time may merit particular consideration for further testing. The risk prediction tool is quick and simple to administer but will need further calibration and validation in a prospective study in primary care.

Funding

Charles Wolfson Trust and Guts UK

Introduction

Oesophageal cancer has a long term survival rate of only 12% but 59% of cases are preventable 1 Early diagnosis is crucial to change disease outcome but symptoms in early oesopahgeal adenocarcinoma (OAC) are often either absent or indistinguishable from uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux. Barrett’s oesophagus (BE) is the only known precursor lesion to OAC, increasing the risk by 30-60 fold 2. The annual incidence of OAC in patients with BE is, nevertheless, low at around 0.1-0.2% 3 and the merits of endoscopic screening are therefore controversial. The minimally invasive Cytosponge may add an important triaging step as it can be administered in general practice and is acceptable to patients 4. It is, however invasive and an important question is which patients to screen with this test.

Obvious target groups would have symptoms and known risk factors. These include age, sex, reflux symptoms, obesity, cigarette smoking, family history and use of anticholinergic drugs 5,6. We previously tried to identify patients at risk by analysing these factors using statistical approaches, with relatively poor success 7. It is therefore not clear whether targeting these groups would work in clinical practice.

Machine learning (ML) applies mathematical models to generate computerised algorithms. These can create novel prediction models. ML involves a computer ‘learning’ important features of a dataset to enable predictions about other, unseen, data. This can be particularly useful to create predictive models about which subjects have a disease 8.

We hypothesised that ML may yield better and more reproducible discrimination between patients with and without BE than statistical models. Previous works often did not validate their results 9,10 or found large reductions in model accuracy in validation cohorts13. Additionally, most studies focused on only a few symptoms, making comparisons difficult. These include, for example, older age 12, male gender 13,14 Caucasian race 15, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) 12,16, smoking 17,18 and central obesity 18. Only two studies considered all of these factors together. One included only 235 BE patients 19 and the other focused on familial disease 20. In the current study we use a large dataset to train and then test a model for detection of BE. We add an additional independent validation set to confirm the robustness of a tool to pre-screen patients for this condition.

Patients & Methods

Patients

BEST2 (ISRCTN 12730505) was a case–control study in 14 UK hospitals running between 2011-2014 to compare the accuracy of the Cytosponge-TFF3 test for the detection of BE with endoscopy and biopsy as the reference standard 4,21. BE was defined as endoscopically visible columnar-lined oesophagus (Prague classification C1 or M3), with histopathological evidence of intestinal metaplasia (IM) on at least one biopsy. Controls comprised symptomatic patients without BE referred for routine endoscopy. Two thirds of the patients had BE and 3% had invasive OAC.

In parallel to assessing the accuracy of cytosponge, this trial included asking patients to complete a questionnaire giving details of 40 symptoms and risk factors, to analyse whether these could be used to risk-stratify patients in line with our previous work 7. Data were collected from 1299 participants. For the current study, this large dataset was randomly split using a computer algorithm into a training dataset of 776 patients (60% of the patients) and a testing dataset of 523 patients (Table 1). This 60/40 split aims to allow sufficient training data to quantify the model’s complexity whilst maintaining adequate data to independently validate the model.

Table 1. Demographic and symptom characteristics in the three datasets according to the presence or absence of Barrett’s Oesophagus.

Discrete variables are presented as numbers and percentages; continuous variables are presented as mean +/- SD

| BEST2 Training Set | BEST2 Testing Set | BOOST Validation Dataset | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE present Number (%) | BE absent Number (%) | P-Value (Chi2 or t- test) | AUC (95% CI) | BE present Number (%) | BE absent Number (%) | P-Value (Chi2 or t- test) | AUC (95% CI) | BE present Number (%) | BE absent Number (%) | P-Value (Chi2 or t- test) | AUC (95% CI) | |

| N | 528 (68%) | 248 (32%) | 352 (67%) | 171 (33%) | 198 (50%) | 200 (50%) | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 436 (81%) | 105 (19%) | <0.0001 | 0.70 (0.67-0.74) | 279 (79%) | 74 (21%) | <0.0001 | 0.68 (0.64 - 0.72) | 155 (62%) | 94 (38%) | <0.0001 | 0.66 (0.61-0.70) |

| Female | 91 (39%) | 143 (61%) | 73 (43%) | 97 (57%) | 42 (29%) | 105 (71%) | ||||||

| Taking Antireflux Medication | ||||||||||||

| No | 32 (24%) | 102 (76%) | <0.0001 | 0.68 (0.65-0.71) | 23 (25%) | 69 (75%) | <0.0001 | 0.67 (0.63 – 0.71) | 17 (20%) | 67 (80%) | <0.0001 | 0.65 (0.61-0.69) |

| Yes | 494 (78%) | 141 (22%) | 326 (76%) | 102 (24%) | 173 (62%) | 108 (38%) | ||||||

| Stomach Pain Frequency | ||||||||||||

| Never | 371 (84%) | 73 (16%) | <0.0001 | 0.73 (0.69-0.76) | 238 (78%) | 66 (22%) | <0.0001 | 0.67 (0.62 - 0.72) | 130 (66%) | 66 (34%) | <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.64-0.74) |

| Occasionally* | 108 (57%) | 82 (43%) | 70 (60%) | 46 (40%) | 24 (62%) | 15 (38%) | ||||||

| Weekly | 28 (42%) | 39 (58%) | 17 (44%) | 22 (56%) | 19 (31%) | 42 (69%) | ||||||

| Daily | 18 (27%) | 49 (73%) | 23 (38%) | 37 (62%) | 15 (22%) | 54 (78%) | ||||||

| Years since acid taste started | ||||||||||||

| Never | 88 (51%) | 84 (49%) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0.72-0.79) | 48 (49%) | 49 (51%) | <0.0001 | 0.77 (0.73 - 0.82) | 102 (57%) | 77 (43%) | 0.0146 | 0.51 (0.46-0.57) |

| Last 6 months | 8 (16%) | 43 (84%) | 4 (12%) | 30 (88%) | 3 (20%) | 12 (80%) | ||||||

| 7 months to a year | 8 (33%) | 16 (67%) | 3 (16%) | 16 (84%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | ||||||

| 1 to 2 years | 26 (51%) | 25 (49%) | 13 (41%) | 19 (59%) | 2 (33%) | 4 (67%) | ||||||

| 2 to 5 years | 52 (68%) | 25 (32%) | 34 (63%) | 20 (37%) | 11 (73%) | 4 (27%) | ||||||

| 5 to 10 years | 79 (77%) | 23 (23%) | 59 (8%) | 15 (2%) | 5 (63%) | 3 (38%) | ||||||

| 10 to 20 years | 123 (91%) | 13 (9%) | 87 (84%) | 16 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) | ||||||

| More than 20 years | 141 (91%) | 14 (9%) | 101 (94%) | 6 (6%) | 6 (86%) | 1 (14%) | ||||||

| Years since heartburn started | ||||||||||||

| Never | 40 (75%) | 13 (25%) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0.72-0.79) | 28 (72%) | 11 (28%) | <0.0001 | 0.77 (0.73 - 0.81) | 121 (61%) | 77 (39%) | 0.0292 | 0.57 (0.52-0.62) |

| Last 6 months | 4 (07%) | 52 (93%) | 2 (5%) | 37 (95%) | 3 (2%) | 12 (8%) | ||||||

| 7 months to a year | 7 (23%) | 23 (77%) | 4 (21%) | 15 (79%) | 1 (33%) | 2 (67%) | ||||||

| 1 to 2 years | 15 (31%) | 34 (69%) | 12 (32%) | 25 (68%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | ||||||

| 2 to 5 years | 45 (56%) | 35 (44%) | 33 (54%) | 28 (46%) | 5 (56%) | 4 (44%) | ||||||

| 5 to 10 years | 90 (71%) | 37 (29%) | 56 (75%) | 19 (25%) | 1 (33%) | 2 (67%) | ||||||

| 10 to 20 years | 141 (85%) | 25 (15%) | 87 (78%) | 25 (22%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | ||||||

| More than 20 years | 183 (88%) | 24 (12%) | 127 (93%) | 10 (7%) | 5 (63%) | 3 (38%) | ||||||

| Age (years) | 67.09 (11.99) | 61.53 (14.37) | <0.0001 | 0.61 (0.57-0.66) | 66.96 (11.93) | 58.94 (15.06) | <0.0001 | 0.66 (0.61 - 0.71) | 67.49 (11.66) | 59.94 (15.38) | <0.0001 | 0.66 (0.60-0.71) |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 101.83 (12.49) | 91.87 (13.40) | <0.0001 | 0.70 (0.66-0.74) | 100.04 (12.33) | 93.66 (13.51) | <0.0001 | 0.64 (0.58 - 0.69) | 90.83 (9.91) | 86.18 (10.86) | 0.0001 | 0.62 (0.56-0.68) |

| Cigarettes / Day | 16.41 (13.33) | 10.61 (8.30) | <0.0001 | 0.63 (0.57-0.68) | 16.27 (13.77) | 11.26 (9.52) | 0.0026 | 0.63 (0.57-0.68) | 32.17 (32.93) | 19.74 (17.28) | 0.0093 | 0.66 (0.56-0.75) |

Patients were recruited to the BOOST study (ISRCTN 58235785) from 2013-2015. The study used enhanced endoscopic techniques to target high-risk lesions arising within BE 22. Clinical and demographic data were collected. Controls included patients referred by their GP with suspected oesophageal cancer, who had neither BE or OAC. This group was analogous to the controls in BEST2 and comprised 50% of study participants. OAC was present in 6% of patients. The questions included those posed in BEST2 but added extras relating to food intake, anxiety and depression. Although BOOST was multi-centre, questionnaires were collected at a single site, UCLH, from 398 patients (Table 1) and were designed from the outset to include the same questions so that they could be used as a validation cohort for a symptom-based algorithm generated from the BEST2 dataset in line with TRIPOD guidelines 23. This dataset was deemed too small to split for analysis.

The primary outcome of a diagnosis of BE was ascertained in both studies by histopathologists who were blinded to predictor variables.

Questionnaires

For BEST2, GORD symptoms were collected by a questionnaire adapted from the GERD Impact Scale 7 together with the GERD questionnaire 9. BOOST also included the HADS hospital anxiety and depression scale. The total number of variables in BEST2 was 40 but was 204 in BOOST. In both studies, data were collected on paper case report forms and transferred to electronic databases.

Sample Size

There are no generally accepted approaches to estimate sample size requirements for derivation and validation studies of risk prediction models. All available data were used to maximise the power and generalisability of results. Model reliability was enhanced by employing an external validation cohort.

Data Handling

Missing data for nominal and numeric features were imputed with the modes and means of the training data. The sections below describe how predictors were handled. We used feature analysis for processing data to identify important predictors. While we considered several options for building a supervised prediction model, unless otherwise specified, we present the results from a logistic regression prediction model.

Machine Learning Methods

Feature Selection

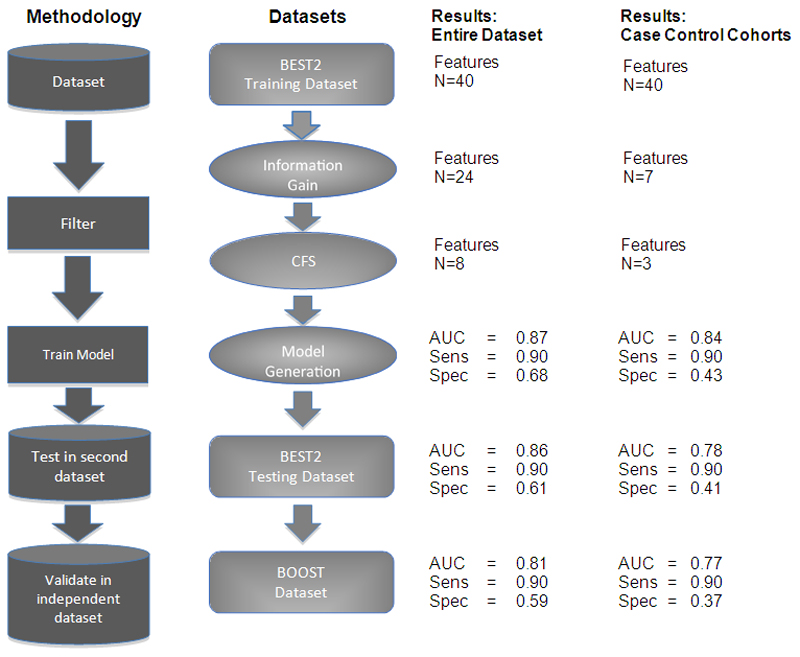

For the training set, data were analysed using two accepted feature selection filters: Information Gain (IG) and Correlation based Feature Selection (CFS). IG is a machine learning univariate filter that compares each feature separately and its correlation with the class. Features are chosen based on how much each discriminates between the groups being investigated, BE versus no BE in our case. Correlated feature selection (CFS) filtering is a multivariable filter that specifically considers features’ correlation to each other and removes redundant features that are highly correlated. The final set of features is then used to generate the analysis model (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Workflow Schema.

The workflow is shown for filtering the data and model creation for both the entire dataset and the smaller case-control cohort analyses. The number of features remaining in the analysis at each stage is shown together with the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity and specificity following logistic regression.

Both Information Gain and CFS are considered filter feature selection methods and thus have the advantage of being fast, scalable and independent of the classifier 24. Independence from the classifier is critical to our study as it allows us to understand which features are being selected by this algorithm and their medical importance. As made clear by Nie et al. 25, filters that are independent of the classifier allow for better interpretability. They should also lead to more stable algorithms than conventional statistical approaches such as backward logistic regression as they minimise data overfitting. Similar to previous work 7, we initially identified features that had at least a minimal correlation to BE.

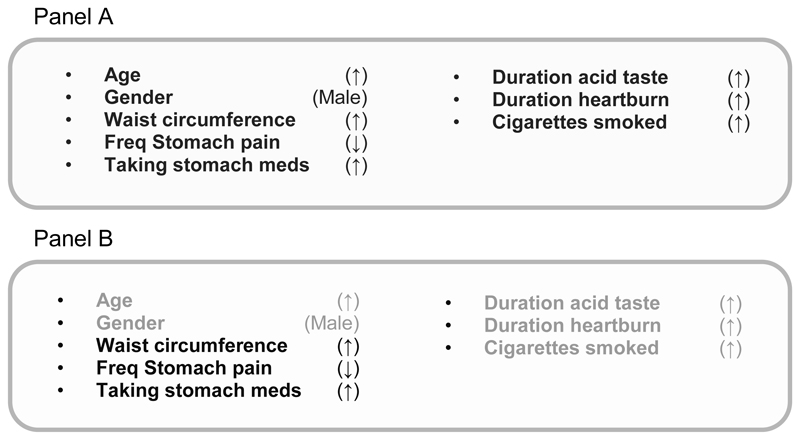

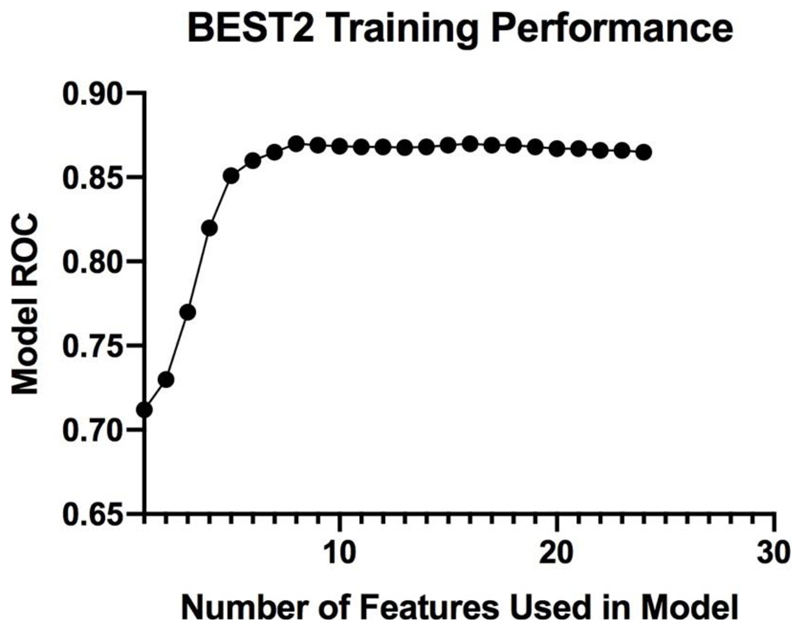

We identified the smallest number of independent features in the BEST2 training dataset to create the model (Figure 2A). The smaller the panel, the more “stability” or robustness to the model creates to minimise the risks of overfitting the data.

Figure 2. The discriminatory panels and analyses performed.

Panel A shows the 8 features selected by CFS for the BEST2 training set together with the direction associated with presence of BE.

Panel B shows which features are found in the CFS model after the datasets are recreated to exclude any potential age, sex, race and symptom duration biases.

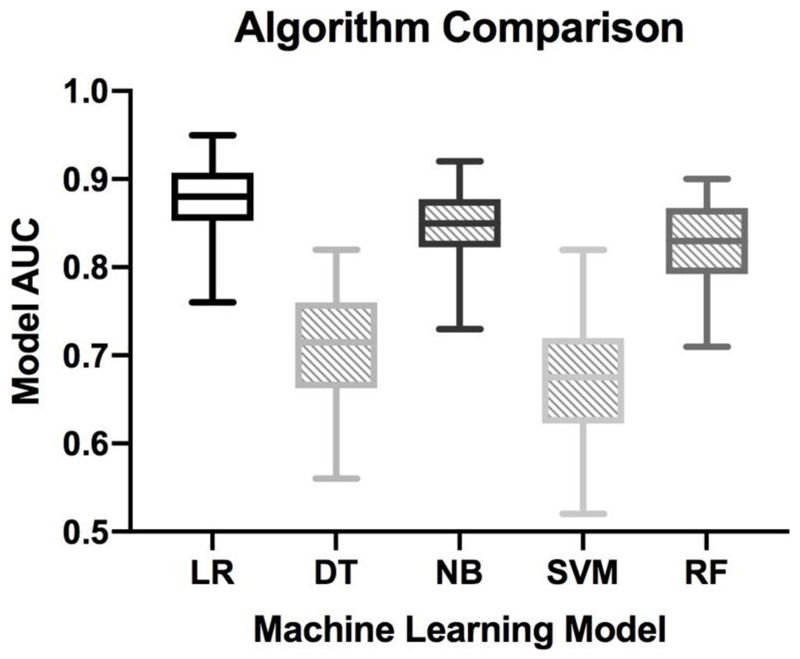

Classification Algorithms

Once features were defined, we considered five different machine learning methods. These are shown in Figure 4 and include a logistic regression model together with four other popular choices: a decision tree based on the Gini measure of quality, a Naïve Bayes classifier assuming a Gaussian distribution, a support vector machine using the Radial Bias Function (RBF) kernel, and a random forest classifier using 10 trees. These five algorithms were chosen for comparison as they represent well-accepted machine learning methods which are typically used in medical applications 26–31. The relative strengths and weaknesses of learning algorithms remains a major research topic but in principle, when training data is limited, simpler models tend to perform better as they will generalise more reliably. Linear and logistic regression models are good examples here. Random forest and decision trees tends to work better when training data are abundant and there is complex interaction between features. Support vector machines can be extremely robust where the number of predictive features is very large compared to the number of training examples, a situation where over-fitting often occurs. Naive Bayes should be preferred over logistic regression if data is sparse but one is confident of the modeling assumptions 32. We also considered using deep neural networks, but given the lack of dimensionality of our data, these models are significantly less accurate and interpretable 33–35.

Figure 4. Comparing the model’s AUC with different machine learning classification algorithms.

Five classification algorithms were used. Shown here are the machine learning models for the BEST2 training dataset with 13 features using Logistic Regression (LR), Decision Tree (DT), Naïve Bayes (NB), Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF). Logistic Regression performed best and was therefore used for the rest of the analyses

The prediction model was developed using 90% of the BEST2 training dataset to train and 10% to internally test the model. This was repeated ten times. The mean area under the Receiver Operator Curve (AUC) was used to determine the final model for testing. This was tested on the remaining 40% of patients in the BEST2 dataset. Finally, an independent validation was performed in the BOOST dataset. The entire workflow is shown in Figure 1. All analyses were performed using the RWeka, cvAUC and pROC packages in R (version 3.6.1).

Risk Group Development

All patients with a diagnosis of dysplastic BE or oesophageal adenocarcinoma were included within the BE group. Patients with ultra-short segment BE (Prague less than C1Mx or less than C0M3) were removed from the analysis completely to create a clear distinction between the groups.

Reporting

This paper was written in line with TRIPOD guidelines 23.

Case Control Design

The input datasets included obvious biases, such as different gender prevalences in the case (BE) and control groups and duration of symptoms. Patients with BE are known to have more longstanding reflux 12,16. In addition, non-BE patients presented with new symptoms whereas those with BE were mostly in surveillance programmes. We reconstructed the datasets so race, gender ratios and age profiles were similar across all datasets. We also removed all features relating to symptom duration. The reconstructed datasets are shown in Table 2. Analyses were then repeated.

Table 2. Demographic and symptom characteristics once potentially confounding variables have been removed.

Discrete variables are presented as numbers and percentages; continuous variables are presented as mean +/- SD

| BEST2 Training Set | BEST2 Testing Set | BOOST Validation Dataset | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE present Mean (SD)/N (%) | BE absent Mean (SD)/N (%) | P-Value (Chi2) | AUC (95% CI) | BE present Mean (SD)/N (%) | BE absent Mean (SD)/N (%) | P-Value (Chi2) | AUC (95% CI) | BE present Mean (SD)/N (%) | BE absent Mean (SD)/N (%) | P-Value (Chi2) | AUC (95% CI) | |

| N | 296 (75%) | 98 (25%) | 227 (76%) | 70 (24%) | 87 (54%) | 75 (46%) | ||||||

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 100.66 (13.17) | 93.03 (12.51) | <0.0001 | 0.66 (0.59-0.72) | 100.19 (12.97) | 95.55 (13.02) | 0.00926 | 0.60 (0.52-0.68) | 91.03 (8.31) | 87.09 (9.38) | 0.00588 | 0.62 (0.53-0.71) |

| Taking Antireflux Medication | ||||||||||||

| No | 14 (25%) | 43 (75%) | <0.0001 | 0.70 (0.65-0.75) | 17 (37%) | 29 (63%) | <0.0001 | 0.67 (0.61-0.73) | 7 (23%) | 24 (77%) | <0.0001 | 0.62 (0.56-0.68) |

| Yes | 282 (84%) | 52 (16%) | 209 (84%) | 41 (16%) | 79 (61%) | 50 (39%) | ||||||

| Stomach Pain Frequency | ||||||||||||

| Never | 217 (86%) | 35 (14%) | <0.0001 | 0.71 (0.64-0.76) | 158 (81%) | 38 (19%) | 0.00867 | 0.60 (0.54-0.66) | 59 (65%) | 32 (35%) | 0.00018 | 0.68 (0.60-0.75) |

| Occasionally* | 48 (63%) | 28 (37%) | 47 (76%) | 15 (24%) | 11 (79%) | 3 (21%) | ||||||

| Weekly | 20 (69%) | 9 (31%) | 10 (63%) | 6 (38%) | 8 (38%) | 13 (62%) | ||||||

| Daily | 11 (32%) | 23 (68%) | 10 (48%) | 11 (52%) | 7 (25%) | 21 (75%) | ||||||

once or twice/month

Funders and Data

BEST2 and BOOST studies were grant funded by MRC and CRUK respectively. The current study was undertaken without specific grant funding. The original funding bodies had no input to the current study. PS had access to all the BEST2 data, LBL and AR had access to all data although diagnostic information for BEST2 testing set was withheld until the model had been created and tested to prevent bias. AR and LBL made the decision to submit but all authors were consulted with the final draft.

Results

Machine Learning Feature Selection to Create Prediction Panel

BEST2 Training Dataset

All patients had a confirmed diagnosis. We selected features with a non-negligible information gain. In line with previous work, we used a threshold of 0.01 (i.e. above a negligible zero value) to select features which would positively impact the model. Features with a weaker correlation to disease were removed. A total of 24 features were selected. We sorted these from highest to lowest information gain correlation to BE and considered subsets with the top k features ranging between 1 and 24. As Figure 3 demonstrates, once the 8 features with the highest information gain were selected, there was no significant increase in the AUC (p-score of the moving average of the next 10 points compared to the original values being 0.7). This is consistent with the concept that adding features, even those with strong correlation to BE, does not necessarily improve model performance.

Figure 3. The Curse of Dimensionality.

The model’s AUC (Y-axis) is compared to the number of features used in the model (X-axis) within the BEST2 training dataset. Increasing the number of features strengthens the model to a plateau point which is reached around 8 features. The model AUC remains unaffected as up to a total of 25 features are added.

Correlation Based Feature Selection

We developed multivariable models using CFS based on the entire 24 common features. CFS selected 8 features as independent predictors of BE (age, gender, waist circumference, stomach pain, taking stomach medicines, duration of heartburn and acid taste in the mouth and smoking). These were not the same as the first 8 features identified by IG analysis (Table 3).

Table 3. Ranked Features in the BEST2 Training Set.

These features offered more than minimal information gain to predict a diagnosis of BE. The number was reduced by assessing for correlated feature selection. The final eight features were fed into the analytical model. The regression coefficients and odds ratios are also shown. The intercept for the regression equation is -5.031.

| Feature | Information Gain Ratio | Remain in Model after CFS | Regression Coefficients in Final Model to predict BE (to 3 significant figures) | Odds Ratio for BE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking Acid Medicines | 0.192 | Yes | 2.033 | 7.639 (yes) |

| Gender | 0.133 | Yes | 1.592 | 4.901 (male) |

| Waist Circumference | 0.107 | Yes | 0.035 | 1.035 |

| Duration of Heartburn | 0.095 | Yes | 0.132 | 1.142 |

| Frequency of Stomach Pain | 0.085 | Yes | -0.836 | 0.433 |

| Duration of Acid Taste | 0.074 | Yes | 0.297 | 1.345 |

| Age | 0.065 | Yes | 0.034 | 1.035 |

| Frequency of Heartburn | 0.062 | |||

| Ethnicitiy | 0.060 | |||

| Weight | 0.060 | |||

| Height | 0.051 | |||

| Frequency of Sleep Disruption | 0.049 | |||

| Body Mass Index | 0.040 | |||

| Amount of alcohol drunk at age 30 | 0.036 | |||

| Frequency of Acid Taste | 0.031 | |||

| Education Level | 0.018 | |||

| Number of cigarettes smoked | 0.016 | Yes | 0.045 | 1.046 |

| Ever smoked | 0.014 | |||

| Amount of alcohol drunk currently | 0.011 |

Creating the Prediction Model

The prediction model was based on the CFS selected features. This is shown in Figure 2A. Logistic regression yielded the best median AUC we elected to use this model. Furthermore, this model is most readily understandable to a medical audience making it easy to convert into a usable tool in clinical practice.

Validating Models

We internally validated the dataset to provide an upper estimate of the model’s predictive ability. The results are incorporated into Figure 1 and show the AUC and the specificity of this model with sensitivity set at 90%, which we considered to be clinically important. The full logistic regression equation is in Table 3. The AUC was 0.87 (CI = 0.84-0.90) and for a sensitivity arbitrarily set at 90% the specificity was 68%.

We validated this model by using the other 40% of the BEST2 data. The model reproduced well with an AUC of 0.86 (CI = 0.83-0.89); sensitivity 90% and specificity 65%. The model was finally tested on the independent validation BOOST dataset. Here the model achieved an AUC of 0.81 (CI = 0.74-0.84); sensitivity 90% and specificity 58%. This three stage development process therefore led to a stable, reproducible model.

For purposes of completeness, we also include the accuracy, recall, precision and F-measure results in Table 4. In the first line, we present the results from the BEST2 internal validation data. In the second line, we validate the BEST2 model on the BOOST data. In all cases, the results are in a relatively narrow range (e.g. accuracy 76.88%-84.51% and F-measure 0.77-0.84) with the lowest values being recorded when validating the BEST2 model on the BOOST data. This is consistent with the AUC results.

Table 4. Extended Metrics for Evaluating the Machine Learning Application.

Given that area under the curve measurements may have limited accuracy for imbalanced datasets, precision-recall and log-loss are included here to demonstrate the stability of the derived model. The first line presents these measures when evaluating the BEST2 model on the randomly selected internal validation set. The second line presents the results of these measures for the BEST2 model externally validated on the BOOST dataset.

Accuracy measures the ratio of the correctly labeled subjects to the whole pool of subjects. Recall is equivalent to sensitivity (of all the people with BE, how many could we correctly predict?) and precision is equivalent to positive predictive value (how many of those labeled with BE actually have it) measured at the highest point on the ROC curve. The F-measure is the harmonic mean (average) of the precision and recall.

| Dataset | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F-measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEST2 internal validation | 84.51 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| BEST2 validated on BOOST | 76.88 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

Removing Potential Bias

Reconstructing the cohorts reduced the BEST2 training dataset from 776 to 394 patients; BEST2 test dataset from 523 to 297 patients and BOOST external validation dataset from 398 to 162 patients. Revised demographics are shown in Table 2. The same methodology was used to create a new model. The new CFS variables are shown in Figure 2B. The same features remain apart from age, sex, race and symptom duration. No new features entered the CFS analysis. Results generated are shown in the last columns in Figure 1. The overall accuracies are lower than the original 8 features but a clear difference remains between patients with and without BE. The initial model has an AUC of 0.84 (CI= 0.79-0.81) which falls to 0.78 (CI = 0.72 – 0.84) in the internal and 0.77 (CI = 0.64 - 0.81) in the external validation dataset.

The list of variables included in the final models and the direction of association with BE are shown in Figure 2. Most features area readily understandable such as age, male sex, longer duration of symptoms, taking acid suppression medicines and central obesity (waist circumference). Others appear counter-intutive such as lower frequency of stomach pain. This is discussed below.

Discussion

The currently used system for identifying patients with BE or those at risk of OAC is flawed as it is based on symptoms which trigger expensive, unpleasant, invasive tests. Simple triaging may be possible based on predictive panels which include variables that are widely available or easy to obtain. Work on the QResearch database has demonstrated the utility of this approach to predict oesophageal cancer 36. This is slowly being incorporated into general practice. This approach has not yet been robustly confirmed to detect the pre-malignant phenotype of Barrett’s oesophagus. This may be because BE is frequently asymptomatic and takes many years to develop into cancer. Nevertheless, this condition needs to be recognised because of the success of early intervention in preventing OAC with its dire prognosis 37.

We have demonstrated that a panel with 8 factors including detailed stomach and chest symptoms, can identify the presence of BE with high sensitivity and specificity. We specifically did not include patients with ‘ultrashort BE’ (Prague <C1 or <M3). Differences exist between UK and US guidelines on follow up for this low-risk group and our aim was to create a prediction tool that avoided this ambiguity. While the methodology used is generally applicable and should be considered for prediction other diseases, this work has focused on BE as an example of how a tool could be used by GPs to better target people for formal screening. Most questions are already asked routinely. It would be simple for a GP to ask the others. Alternatively, a patient could self-assess using a web-based app and generate a personalised risk for having BE. Precise cutoffs between patients and controls will need to be defined once this panel is tested prospectively in a primary care population where the frequency of BE is lower than in our cohorts. For a particular AUC, the sensitivity chosen for use in clinical practice can be altered depending on the clinical question. Whereas triaging for cancer in symptomatic individuals would require a sensitivity of 95% or greater, it may not be so critical to miss BE, and a sensitivity of even lower than 90% may be adequate. Further, if Cytosponge is confirmed as a cheap, acceptable screening test for BE, the current triaging tool could be tuned to a very high sensitivity. It would then be aimed specifically at Cytosponge negative individuals, to recommend endoscopy nevertheless, and thereby improve the overall sensitivity of a combined screening approach.

We have created a panel which validates both internally and on an external validation cohort. Reflux duration is strongly correlated with cancer risk and is longer in patients with BE. In our panel, use of antireflux medicines was a strong predictor of BE. Metabolic obesity characteristically presents with truncal obesity. It is also a risk factor for BE which explains why our model predicted BE patients to have greater waist circumferences 38. Waist circumference is not routinely collected, but it is easy to do, particularly for patients who wish to self-triage. There is a clear correlation between this and body mass index (BMI) which is routinely collected. Our method identified the most important independent predictors of BE. In routine practice, it may be better to replace this with BMI. Another finding which initially appears counter-intuitive is the negative correlation between BE and severity of heartburn. On closer inspection this makes sense. Most OAC patients are not identified before cancer develops despite many of them having BE. Indeed 40% of OAC patients have not previously suffered from symptomatic reflux and many probably had BE 39. It has been hypothesised that BE is therefore not associated with severity of reflux symptoms 40. This fits with the model determined from our data.

Our panel differs from the QResearch database work. That panel includes dysphagia, appetite loss, weight loss and anaemia as predictors for cancer. It does not include duration of symptoms or central obesity data which appear here. This reflects the different realities of BE and OAC.

Previous works have identified risk factor panels. Some included multiple biomarkers such as leptin and interleukin levels or GWAS data which are not easily available and others included only very limited numbers of symptoms 9,41. For those where the risk factor panels were larger, several key differences exist between our analysis and previous work. We confirmed the importance of older age 12,41–43, male gender 10,13,14,43 Caucasian race 15, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) 9–12,16,42,44, smoking 17,18,41,42 and central obesity 41,42,45. However, we found that many of these risk factors were cross-correlated. We overcame the challenge of panels failing external validation through a combination of univariate and multivariable feature selection techniques that yielded a stable panel. The results are better than previous panels with sensitivities of 70-80% and specificities of 50-60% or AUC of 0.7 9,10,41,42. In contrast, our panel validates between completely different datasets at a level of at least 0.81 with only eight risk factors considered. This may be adequate to be used as a triaging tool in clinical practice. Three recent studies support our findings. Xie et al followed 63,000 patients for 20 years in Norway. They constructed a model based on a very similar risk panel to ours. Their data was taken from a patient cohort without the level of symptom granularity we achieved by interviewing individual patients. The AUC of their model to identify 15 year risk of OAC was 0.84 but it did not attempt to identify BE patients 46. Similarly, Kunzmann et al examined 355,034 individuals in the UK Biobank. Their panel including age, sex, smoking, body mass index, and history of esophageal conditions or treatments identified individuals who would later develop OAC with an AUC of 0.80 47. Once again, this does not specifically aim to identify BE although the features are remarkably similar to ours suggesting that many patients they identified may indeed have undiagnosed BE. The single study to target sporadic BE alone was undertaken in a small Australian cohort and the choice of risk factors was determined by complex deduction although it did lead to a tool with an AUC of 0.82 which later validated in an independent dataset 19,48. One element of that model was hypertension. This was not found in our cohorts and raises the question of stability of their model. Our study used a generally applicable machine learning framework to avoid these potential biases.

As our goal is to create a tool for pre-screening, we intentionally used the BEST2 and BOOST datasets which had a larger number of Barrett's patients than in the general population. In general, an open challenge to machine learning exists for how to properly identify important “minority” categories—here BE. As BE is relatively uncommon, with a prevalence rate as low as 2% 49, one could create extremely accurate models by assuming nobody has BE. In the BEST2 and BOOST datasets, this issue was mitigated by targeted collection of suspected at-risk individuals which thus led to a distribution of BE that is much higher than that of the general population. Several methods exist to computationally rebalance the data beyond or addition to this approach. The most common approach is undersampling whereby existing records belonging to a prevalent category are intentionally removed to create a different ratio between the classes. Here, the relatively high numbers of BE patients could be adjusted by randomly removing some of the cases. Alternatively, oversampling could be used whereby cases of normal patients are added after the case to generate a new balance between the target cases. One popular example of this approach, SMOTE, 50, synthetically adds artificial cases to the minority class. Another approach would be to apply a ratio of controls to known cases in order to train the model with a prevalence that more closely aligns with the real-world setting.

The advantage of using datasets that inherently have higher distributions of Barrett’s cases is that our data is non-synthetic and thus more likely to be effective as a screening tool. However, further studies are needed to confirm this claim and to study any potential impact of false positives / negatives generated in a real-world setting. To this end, we propose to apply our algorithm to the data generated from the BEST3 study. This is pragmatic multi-site cluster-randomised controlled trial set in primary care in England which has a prevalence of BE representative of the general population and in which the same questions have been asked 51. We are also conducting another prospective study to test this hypothesis independently in a second population that more closely aligns with population prevalence of disease 52.

The methods used to apply the machine learning analysis also present a challenge. Many researchers perform both univariate and multivariable analysis of each dataset independently. This often leads to selecting similar features in both datasets. We have previously done this ourselves. We made very tiny changes in our definitions of BE (with or without IM). Each was associated with different risk factors being important in the ensuing algorithms. These differences stem from a lack of “stability” in the features that each model independently selected 7. Too many features, even those with relatively high prediction value, often reduces the model’s power.

One current solution to both of these challenges is through effective feature selection. We approached this by identifying which features add information. This is called information gain, a univariate approach. In our previous work 7, we used a threshold of 0.1 within X2 with 1 degree of freedom to select 8 features in the dataset. An advantage to using feature selection to determine important features is that they are based on a filter approach to selection which is conducted without any connection to a specific learning algorithm. Similarly, no human bias is involved. We incorporated this approach as one step in our current analysis.

Our results show stability across the BEST2 and BOOST datasets. While each of these datasets was collected independently, their collection methodologies and definitions were similar enough for effective comparison. This study shows that such analyses are possible if one focuses finding such stable features such as through the methodology we detail which are not influenced by random artifacts in the data collection process 53.

We considered using other multivariate feature selection algorithms including LASSO 54. LASSO is one type of feature selection that is embedded within logistic regression as its feature analysis is inherently linked to this machine learning method. It suffers from a similar limitation of the RFE-SVM (SVM recursive feature selection)55 approach. Both are limited to only one algorithm, in the case of RFE-SVM, the SVM algorithm that we also considered. As we wished to consider a variety of machine learning methods, we preferred using Information Gain and CFS which are filter methods and can be used without any connection to a specific machine learning prediction model 24 thus facilitating better medical understanding 35.

We also considered correlations between features, which often exist in medical datasets. We used the multivariable CFS algorithm to do this. We reasoned that features selected by CFS should be more stable than other approaches. This is borne out by the high AUC of the predictive model and its stability against the independent validation cohort.

Having created our dataset, we have considered possible biases and sought to minimise these by reconstructing the cohorts to avoid any age, sex or race bias. Despite this the model remains robust.

The panels within this paper are easy to use in practice. Theoretically, people could enter their symptoms into a smartphone and receive an immediate risk-factor analysis. This data could then be uploaded to a central database (e.g. in the cloud) which would be updated after that person sees their medical professional.

There are limitations to this study. As both datasets were collected from at-risk individuals, the dataset was enriched for the patients with BE. A dataset more representative of the general population, with fewer disease instances, could potentially yield different results. A further limitation is that patients attending for symptom assessment are more symptomatic than those undergoing surveillance endoscopy. Nevertheless, all the BE patients undergoing surveillance would have presented initially with symptoms. It is certainly true that many individuals with BE have no symptoms and this panel is unlikely to work for these people. Nonetheless, given the robustness of the models generated, there is a reasonable expectation that the panel produced here could be of benefit to rapidly triage symptomatic patients for minimally invasive screening tools such as the Cytosponge as many symptomatic individuals currently undergo no testing at all 56. Further prospective data collection is needed using a cohort study design within a primary care setting where prevalence of BE will be much lower to confirm the validity of our findings and to establish the final best risk prediction model parameters.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for models to identify the presence of Barrett’s oesophagus (BE) with the terms “Barrett’s esophagus”, “Prediction Model”, “Risk Factors” and “Risk Prediction Models” for previous studies published in English up to 30th June 2019. Previous studies have identified multiple risk factors but, with two recent exceptions, one involving a small cohort of patients and the other looking at familial risk, they have either not synthesised them to create a comprehensive risk factor panel or have not validated them in a completely independent dataset.

Added value of this study

The current study takes two large datasets (BEST2 and BOOST) which include between them more than 1600 patients and controls. Robust machine learning methods were used to create a stable algorithm to predict the presence of BE from the BEST2 cohort. These were tested internally and then validated externally in the BOOST cohort. A reliable, stable, prediction panel was created that can now be prospectively tested in a primary care cohort.

Implications of all the available evidence

A successful risk prediction panel would, for the first time, allow routine non-invasive identification of patients who are at high risk of having Barrett’s oesophagus.

Acknowledgements

This research/study/project was funded by the Charles Wolfson Trust and Guts UK and supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. This work was also supported by the CRUK Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre at UCL and the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Interventional and Surgical Sciences (WEISS) at UCL; [203145Z/16/Z]. BEST2 was funded by Cancer Research UK (12088 and 16893).

Footnotes

Involvement with the manuscript:

AR study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; statistical analysis;

DG study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content;

SJ, JA, DH, AW, SJL BEST2 team acquisition of data;

SSS, OA drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content;

MN, MRJ, AW analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content;

EMH, MBZ, UN analysis and interpretation of data; statistical analysis; technical, or material support;

RCF, PS study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; technical, or material support;

LBL study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; obtained funding; study supervision)

Declarations of Interest

The Cytosponge device was designed by RCF and her research team in between 2009 and 2010. Patents and a trademark were filed in 2010 by the Medical Research Council (MRC). The BEST2 study was designed in 2010 and the device was manufactured for the specific purpose of this study following a letter of no objection from the Medical Health Regulatory Agency. In 2013 the MRC licensed the technology to Covidien GI Solutions, now part of Medtronic Inc. They have had no influence in any way on the design, conduct or analysis of this study. RCF, is a named inventor on patents pertaining to the Cytosponge and related assays. She has not received any financial benefits to date. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

Data Sharing Statement

- Data will be collected with an appropriately high level of quality assurance.

- Data will be held securely with appropriate documentation.

- The data will not be put into the public domain or otherwise shared without explicit ethical review or legal obligation.

- We aim to exploit any data generated to the maximum public good.

- These datasets are governed by data usage policies specified by the data controller (UCL, Cambridge, CRUK). Those wishing to access the data will need to ensure that their use fulfils the requirements of the data controllers. Where there is a conflict that severely limits the analyses that can be undertaken, we would endeavour to support outside researchers by hosting them as visiting workers in our team so that they can access the data.

- We are committed to complying with CRUK's Data Sharing and Preservation Policy.

References

- 1.Brown KF, Rumgay H, Dunlop C, et al. The fraction of cancer attributable to modifiable risk factors in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom in 2015. Br J Cancer. 2018;118(8):1130–1141. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0029-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagergren J. Adenocarcinoma of oesophagus: What exactly is the size of the problem and who is at risk? Gut. 2005;54(SUPPL. 1):1–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Mohr Drewes A, et al. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1375–1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross-Innes CSCSCS, Debiram-Beecham I, Walker E, et al. Evaluation of a Minimally Invasive Cell Sampling Device Coupled with Assessment of Trefoil Factor 3 Expression for Diagnosing Barrett’s Esophagus: A Multi-Center Case–Control Study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(1):1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63(1):7–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexandre L, Broughton T, Loke Y, Beales ILP. Meta-analysis: risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma with medications which relax the lower esophageal sphincter. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25(6):535–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Wong A, Kadri SRSR, et al. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease symptoms and demographic factors as a pre-screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang P, Li Y, Reddy CK. Machine learning for survival analysis: A survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2019;51(6):110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Can symptoms predict endoscopic findings in GERD? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(5):661–670. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(03)02011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerson LB, Edson R, Lavori PW, Triadafilopoulos G. Use of a simple symptom questionnaire to predict Barrett’s esophagus in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):2005–2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thrift AP, Kendall BJ, Pandeya N, et al. A Clinical Risk Prediction Model for Barrett Esophagus. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5(9):1115–1123. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eloubeidi MA, Provenzale D. Clinical and demographic predictors of Barrett’s esophagus among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a multivariable analysis in veterans. [Accessed March 31, 2016];J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001 33(4):306–309. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford AC, Forman D, Reynolds PD, Cooper BT, Moayyedi P. Ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status as risk factors for esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(5):454–460. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Achem SR, et al. Barrett’s esophagus is common in older men and women undergoing screening colonoscopy regardless of reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thukkani N, Sonnenberg A. The influence of environmental risk factors in hospitalization for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-related diagnoses in the United States. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson LA, Watson RGP, Murphy SJ, et al. Risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: results from the FINBAR study. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(10):1585–1594. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i10.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson J, Håkansson HO, Mellblom L, et al. Risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus: A population-based approach. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007 doi: 10.1080/00365520600881037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steevens J, Schouten LJ, Driessen ALC, et al. A prospective cohort study on overweight, smoking, alcohol consumption, and risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ireland CJ, Fielder AL, Thompson SK, Laws TA, Watson DI, Esterman A. Development of a risk prediction model for Barrett’s esophagus in an Australian population. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(11):1–8. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X, Elston RC, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, et al. Predicting Barrett’s Esophagus in Families: An Esophagus Translational Research Network (BETRNet) Model Fitting Clinical Data to a Familial Paradigm. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(5):727–735. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross-Innes CS, Chettouh H, Achilleos A, et al. Risk stratification of Barrett’s oesophagus using a non-endoscopic sampling method coupled with a biomarker panel: a cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipman G, Bisschops R, Sehgal V, et al. Systematic assessment with I-SCAN magnification endoscopy and acetic acid improves dysplasia detection in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2017;49(12):1219–1228. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-113441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD Statement. Eur Urol. 2015;67(6):1142–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saeys Y, Inza I, Larrañaga P. A review of feature selection techniques in bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(19):2507–2517. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nie F, Xiang S, Jia Y, Zhang C, Yan S. Trace ratio criterion for feature selection. Proc Natl Conf Artif Intell. 2008;2:671–676. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalilia M, Chakraborty S, Popescu M. Predicting disease risks from highly imbalanced data using random forest. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-11-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moturu ST, Johnson WG, Liu H. Predicting future high-cost patients: A real-world risk modeling application. Proc - 2007 IEEE Int Conf Bioinforma Biomed BIBM 2007; 2007. Dec, pp. 202–208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maroco J, Silva D, et al. Data mining methods in the prediction of Dementia: A real-data comparison of the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of linear discriminant analysis, logistic. BmcresnotesBiomedcentralCom. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-299. AR-B, 2011 U. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langley NR, Dudzik B, Cloutier A. A Decision Tree for Nonmetric Sex Assessment from the Skull. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63(1):31–37. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krittanawong C, Zhang HJ, Wang Z, Aydar M, Kitai T. Artificial Intelligence in Precision Cardiovascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(21):2657–2664. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W, Zeng F, Wu X, Zhang X, Jiang R. A comparative study of ensemble learning approaches in the classification of breast cancer metastasis. Proc - 2009 Int Jt Conf Bioinformatics, Syst Biol Intell Comput IJCBS 2009; 2009. May, pp. 242–245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.C DR. Machine Learning in Medicine. Circulation. 2015;132(20):1920–1930. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eftekhar B, Mohammad K, Ardebili HE, Ghodsi M, Ketabchi E. Comparison of artificial neural network and logistic regression models for prediction of mortality in head trauma based on initial clinical data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005 Feb;5 doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahid N, Rappon T, Berta W. Applications of artificial neural networks in health care organizational decision-making: A scoping review. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenfeld A, Richardson A. Explainability in Human–Agent Systems. Vol. 33. Springer; US: 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Symptoms and risk factors to identify men with suspected cancer in primary care: Derivation and validation of an algorithm. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):1–10. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X660724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haidry RJ, Lipman G, Banks MR, et al. Comparing outcome of radiofrequency ablation in Barrett ’ s with high grade dysplasia and intramucosal carcinoma : a prospective multicenter UK registry. Endoscopy. 2015 Jun;3(11):980–987. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Caro S, Cheung WH, Fini L, et al. Role of body composition and metabolic profile in Barrett’s oesophagus and progression to cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(3):251–260. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, Nyrén O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(11):825–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nason KS, Wichienkuer PP, Awais O, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptom severity, proton pump inhibitor use, and esophageal carcinogenesis. Arch Surg. 2011;146(7):851–858. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thrift AP, Garcia JM, El–Serag HB. A Multibiomarker Risk Score Helps Predict Risk for Barrett’s Esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(8):1267–1271. doi: 10.1016/J.CGH.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubenstein JH, Morgenstern H, Appelman H, et al. Prediction of Barrett ’s Esophagus Among Men. 2013 Sep;2012(2012):353–362. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edelstein ZR, Bronner MP, Rosen SN, Vaughan TL. Risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a community clinic-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(4):834–842. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abrams JA, Fields S, Lightdale CJ, Neugut AI. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus among patients who undergo upper endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kubo A, Cook MB, Shaheen NJ, et al. Sex-specific associations between body mass index, waist circumference and the risk of Barrett’s oesophagus: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON consortium. Gut. 2013;62(12):1684–1691. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie S-H, Ness-Jensen E, Medefelt N, Lagergren J. Open: Assessing the Feasibility of Targeted Screening for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Based on Individual Risk Assessment in a Population-Based Cohort Study in Norway (The HUNT Study) Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(6):829–835. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kunzmann AT, Thrift AP, Cardwell CR, et al. Model for Identifying Individuals at Risk for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1229–1236.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ireland CJ, Gordon AL, Thompson SK, et al. Validation of a risk prediction model for Barrett’s esophagus in an Australian population. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:135–142. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S158627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elizondo JLH, Robles RM, Compean DG, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus: An observational study from a gastroenterology clinic. Rev Gastroenterol México (English Ed. 2017;82(4):296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmx.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lemaitre G, Nogueira F, Aridas CK. Imbalanced-learn: A python toolbox to tackle the curse of imbalanced datasets in machine learning. J Mach Learn Res. 2017;18(1):559–563. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Offman J, Muldrew B, O’Donovan M, et al. Barrett’s oESophagus trial 3 (BEST3): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial comparing the Cytosponge-TFF3 test with usual care to facilitate the diagnosis of oesophageal pre-cancer in primary care patients with chronic acid reflux. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4664-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ISRCTN - ISRCTN11921553. Saliva to predict risk of disease using transcriptomics and epigenetics. [Accessed October 24, 2019]; http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN11921553.

- 53.Kalousis A, Prados J, Hilario M. Stability of feature selection algorithms: a study on high-dimensional spaces. Knowl Inf Syst. 2007;12(1):95–116. doi: 10.1007/s10115-006-0040-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park T, Casella G. The Bayesian Lasso. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103(482):681–686. doi: 10.1198/016214508000000337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang X, Lu X, Shi Q, et al. Recursive SVM feature selection and sample classification for mass-spectrometry and microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Offman J, Fitzgerald RC. Alternatives to Traditional per oral Endoscopy for Screening. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.