Abstract

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) generally appears in the skin or oral cavity, but rarely occurs in the small intestine, where it can cause bleeding. To date, only 35 cases of small intestinal PG have been reported in the English literature. We retrospectively collected information from the clinical records of seven cases of small intestinal PG that were managed in our hospital and summarized the characteristics. Further information on the clinical characteristics was obtained from the literature. Capsule endoscopy, useful for identifying the source of hemorrhage in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, can detect PGs. Treatment can often be accomplished with endoscopic mucosal resection.

Keywords: pyogenic granuloma, obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, capsule endoscopy

Introduction

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a capillary hemangioma first reported in 1897 by Poncet et al. (1) who called it Botryomycosis humaine; however, in 1904, Hartzell (2) named it as pyogenic granuloma. PGs generally occur on the skin or in the oral cavity. In contrast, they are rarely reported in the digestive tract (3).

Small intestinal bleeding is uncommon, accounting for only approximately 4% of all cases of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Angiodysplasias and tumors are the most common causes of small intestinal bleeding (4). There are few reports of bleeding caused by PG in the small intestine (35 case reports). We herein describe a series of cases of small intestinal PG, and review the clinical and endoscopic features of our patients and those reported in the literature.

Case Report

Material and Methods

This was a single-center, retrospective, observational case series of seven patients with small intestinal PG who were admitted to Keio University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) between April 2010 and January 2018. We retrospectively collected information from their medical records, including age, sex, comorbidities, symptoms, blood test results, endoscopic data, and treatment.

Results

Among the seven cases, there were eight PGs, as one patient had two metachronous lesions (Table 1). The average age was 69.1 years, and there were four men and three women. Anemia, hematochezia, and melena were the main presenting signs. Laboratory examination revealed iron deficiency anemia in many cases, with an average hemoglobin level of 9.14 g/dL. Comorbidities included liver disease in three patients and renal disease in three patients, two of whom were on dialysis. Three patients were taking anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 7 Patients with Pyogenic Granulomas.

| Case no |

Age | Sex | Presentation | Hb (g/dL) |

Fe (µg/dL) |

MCV (fl) |

Ferritin (ng/mL) |

Comorbidity | Use of anticoagulant / antiplatelet drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 82 | F | Hematochezia | 8.6 | 18 | 93 | 18 | None | None |

| 2 | 68 | M | Anemia | 11.7 | - | 92 | - | Alcoholic liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma | None |

| 3 | 53 | M | Melena, Anemia | 7.7 | 48 | 84 | 41 | Chronic hepatitis B/C, chronic glomerulonephritis (under hemodialysis), angina | None |

| 4 | 66 | M | Anemia | 13.9 | 80 | 91 | 27 | Brain infarction | Cilostazol |

| 5 | 79 | M | Anemia | 6.6 | 24 | 97 | 40 | Atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure, diabetes | Warfarin |

| 6 | 66 | F | Hematochezia | 8 | - | 96 | 94 | Chronic renal failure (under hemodialysis), diabetes | Low dose aspirin |

| 7 | 70 | F | Anemia | 7.5 | 36 | 87 | 73 | Non-alcoholic fatty liver | None |

Hb: hemoglobin, MCV: mean corpuscular volume

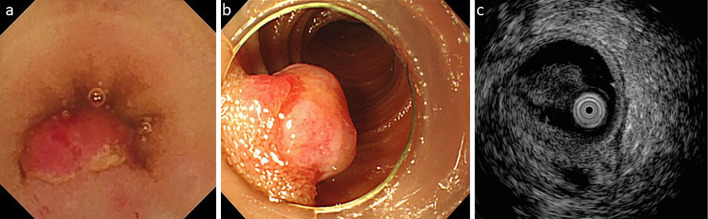

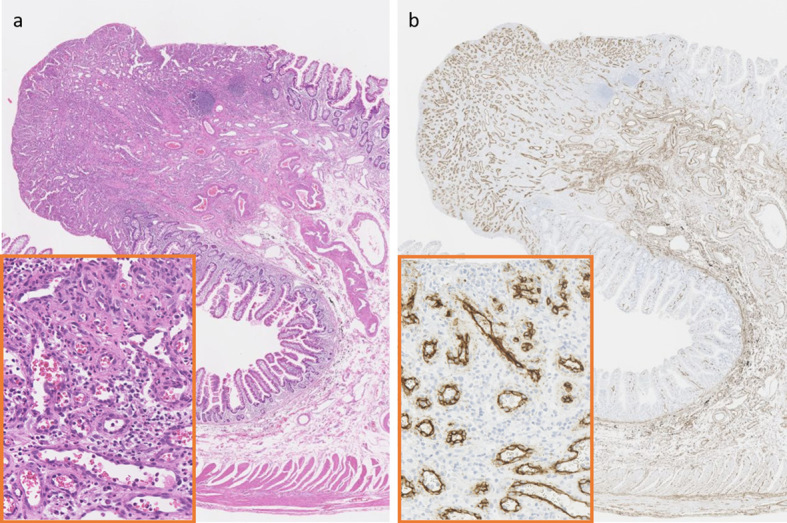

The endoscopic characteristics of the eight lesions are summarized in Table 2. Three-quarters (6/8) of the PGs were located in the ileum. Patient 3 had two metachronous lesions at different sites, so the second was not thought to be a recurrence of the first polyp, which had been treated with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). The average tumor size was 5.9 mm, all PGs were <10 mm in size and semi-pedunculated. Although single capsule endoscopy (CE) localized the lesions in some cases, in other cases, repeat CE and/or single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) was needed before the PG was found. CE found the lesions in half of the cases. Six PGs were treated with EMR, and two were surgically resected. In Patient 2, CE detected bleeding from a 5-mm semi-pedunculated polyp in the ileum (Fig. 1a), which was also seen on SBE (Fig. 1b). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) showed that the muscle layer and tumor could not be clearly distinguished (Fig. 1c). Thus, the lesion was tattooed with black ink and was subsequently removed surgically. Surgery was performed in the other case because, when EMR was attempted, the tumor did not lift after submucosal injection. The pathology findings from Patient 2 are shown in Fig. 2. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining showed increased, lobulated, and enlarged capillaries and desquamated epithelium, indicating epithelial erosion (Fig. 2a). Immunostaining with CD34, a marker of vascular endothelial cells, showed capillary proliferation (Fig. 2b).

Table 2.

Endoscopic Characteristics of the 8 Pyogenic Granulomas.

| Case no | Location | Size (mm) | Form | Treatment | Endoscopic procedures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ileum | 6 | Semipedunculated | EMR | CE, SBE |

| 2 | ileum | 5 | Semipedunculated | Surgery | CE, SBE |

| 3-1 | ileum | 4 | Semipedunculated | EMR | CE, SBE |

| 3-2 | jejunum | 6 | Semipedunculated | Surgery | CE, SBE |

| 4 | duodenum | 8 | Semipedunculated | EMR | EGD |

| 5 | ileum | 7 | Semipedunculated | EMR | CE, SBE |

| 6 | ileum | 6 | Semipedunculated | EMR | CE, SBE |

| 7 | ileum | 5 | Semipedunculated | EMR | CE, SBE |

SBE: single-balloon enteroscopy, CE: capsule endoscopy, EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Figure 1.

Endoscopic and ultrasonic images of a pyogenic granuloma (Patient 2). The endoscopic findings from Patient 2. (a) Capsule endoscopy detected bleeding from a 5-mm semi-pedunculated polyp in the ileum. (b) The lesion was also seen on single-balloon enteroscopy. (c) On endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), the muscle layer and tumor could not be clearly distinguished.

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) (a) and anti-CD34 staining (b) of a pyogenic granuloma (Patient 2). The pathology findings from Patient 2 (Low magnification: ×12, High magnification: ×240). (a) H&E staining showed increased, lobulated, and enlarged capillaries and desquamated epithelium, indicating epithelial erosion. (b) Immunostaining with CD34, a marker of vascular endothelial cells, showed capillary proliferation.

Discussion

PG is a painless, capillary-proliferative lesion that can cause gastrointestinal hemorrhage if located in the digestive tract. It is commonly dark black or bright red, often in the form of stalked or semi-pedunculated polyps. The surface frequently becomes ulcerated. The etiology is thought to be infection or irritation-induced granulation, with 38-70.5% of patients reported to have a history of trauma or infection. In the oral cavity, many patients have a history of chronic irritation from ill-fitting dentures, bites, or sharp teeth. Chronic irritation, such as mucosal damage from fish bones or exposure to gastric acid is reportedly a cause of PG in the gastrointestinal tract. On the other hand, there are also reports of some cases sin which PG developed without trauma or a specifically identified trigger (5). Histopathologically, PG is a hemangioma characterized by lobule-like growth of capillaries with enlarged vascular endothelial cells and inflammatory cell infiltration in the stroma.

PG in the small intestine is rare. Our search of the PubMed database yielded only 35 reported cases of small intestinal PG (3, 5-37); ours is the first case series of small bowel PG. The characteristics of the patients in previously reported cases [male, n=15 (42.8%); female, n=20 (57.1%); average age, 55.6 years (2-86 years)] are summarized in Table 3. Melena was the most frequent presenting sign, followed by anemia. Three patients presented with hematochezia. Data on hemoglobin and comorbidities were available for nearly half of the cases. The average hemoglobin level was 7.96 g/dL. A range of comorbidities were observed, including renal disease (n=3) liver disease (n=3), inflammatory bowel disease (n=2), heart disease (n=2), hypertension (n=1), and brain disease (n=1). As in those reported cases, our series did not indicate that PG was associated with any particular disease.

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics of 35 Reported Cases of Pyogenic Granuloma.

| Item | Result |

|---|---|

| Gender (35/35 cases) | |

| Male | 15(42.8%) |

| Female | 20(57.1%) |

| Age (35/35 cases) | Average 55.6±20.8 |

| <40 | 7(20.0%) |

| 40-60 | 11(31.4%) |

| 60-80 | 14(40.0%) |

| >80 | 3(8.6%) |

| Presentation (34/35 cases) | |

| Melena | 17(50.0%) |

| Anemia | 8(23.5%) |

| Hematochezia | 3(8.8%) |

| Abdominal pain | 2(5.9%) |

| Palpitation | 1(2.9%) |

| Fecal occult blood positive | 1(2.9%) |

| None | 2(5.9%) |

| Hemoglobin(g/dL) (18/35 cases) | Average 7.96±3.17 |

| <6 | 5(27.8%) |

| 6-8 | 5(27.8%) |

| 8-10 | 4(22.2%) |

| >10 | 4(22.2%) |

| Comorbidities (18/35 cases) | |

| Renal disease | 3 |

| Liver disease | 3 |

| IBD(Inflammatory bowel disease) | 2 |

| Heart disease | 2 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Brain disease | 1 |

| None | 6 |

Table 4 summarizes the tumor characteristics in the reported cases. The most common location was in the ileum [n=21 (60.0%)], followed by the jejunum [n=11 (31.4%)] and the duodenum [n=3 (8.6%)]. The median tumor size was 10.0 mm (3-60 mm), with no particular form predominating [sessile polyps, n=10 (34.5%), semi-pedunculated polyps, n=10 (37.9%), and pedunculated polyps, n=8 (27.6%)]. Surgery was performed in 23 cases (65.7%), while EMR was performed in 9 (25.7%). The endoscopic and morphologic characteristics of our case series were similar to those reported in the literature; however, we were able to remove the lesion endoscopically in the majority of our patients. Although there is no guideline on the endoscopic resection of small intestinal polyps, semi-pedunculated- or pedunculated-type PG without a non-lifting sing is considered to be an indication for endoscopic treatment, because the risk of perforation is relatively low. In symptomatic patients, such as those with occult and overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB), PG should be removed as a diagnostic treatment. Motohashi et al. (5) reported a PG that invaded the lower serosal layer via connective tissue in the muscle layers. Thus, preoperative EUS is also recommended so that incomplete endoscopic resection can be avoided. In addition, one of our cases experienced oozing bleeding, which was difficult to stop after a biopsy before endoscopic resection. Since PG is a polyp with abundant capillaries on its surface, in cases in which PG is suspected, EMR should be applied as a diagnostic therapy without biopsy.

Table 4.

Tumor Characteristics of 35 Reported Cases of Pyogenic Granuloma.

| Characteristics | Result |

|---|---|

| Location (35/35 cases) | |

| Duodenum | 3(8.6%) |

| Jejunum | 11(31.4%) |

| Ileum | 21(60.0%) |

| Size(mm) (28/35 cases) | Median 10.0 (3-60) |

| <10 | 11(39.3%) |

| 10-20 | 8(28.6%) |

| 20-30 | 5(17.9%) |

| >30 | 4(14.3%) |

| Form (29/35 cases) | |

| Sessile | 10(34.5%) |

| Semipedunculated | 11(37.9%) |

| Pedunculated | 8(27.6%) |

| Therapy (35/35 cases) | |

| Surgery | 23(65.7%) |

| EMR | 9(25.7%) |

| APC | 1(2.9%) |

| Laser therapy | 1(2.9%) |

| Follow up | 1(2.9%) |

EMR: endoscopic mucosal resection, APC: argon plasma coagulation

The Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guidelines for OGIB (38) recommend dynamic computed tomography (CT) as the initial approach. However, when the source of the hemorrhage is a small lesion such as a PG, it is often not detectable on CT. CT did not demonstrate PG in any of our cases, whereas CE did. Moreover, CE provides a good estimation of the location of the bleeding point in the small intestine, indicating where the treating enteroscope should be inserted. Although CT is effective for detecting small intestinal stenosis, which allows the avoidance of CE retention, small lesions like PG can be difficult to detect without direct visualization with a modality like CE. In our cases, there were more lesions of <10 mm in size in comparison to previous reports. Thus, we couldn’t detect the bleeding sources with CT. Moreover, when CE was performed, half of the first CE examinations did not detect PGs. If the bleeding source cannot be identified by a single CE examination, repeated CE should be considered to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Several studies have reported that if overt bleeding, such as melena or hematochezia, is observed, then urgent CE within 24 hours increased the rate at which the bleeding source was detected from 44.2-56% to 87-92.3% (39-41). Consequently, urgent CE is one option to identify OGIB sources.

In conclusion, PG is a possible, albeit rare, cause of OGIB. CE is the modality that is most likely to successfully detect PG. EMR should be the first-line approach in therapy; however, an EUS examination is recommended to minimize the chance of incomplete resection.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Poncet A, Dor L. Botruomycose humaine. Rev Chir 18: 996, 1897. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hartzell MB. Granuloma pyogenicum. J Cutan Dis 22: 520-523, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moffatt DC, Warwryko P, Singh H. Pyogenic granuloma: an unusual cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding from the small bowel. Can J Gastroenterol 23: 261-264, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewis BS. Small intestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 29: 67-95, vi, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Motohashi Y, Hisamatsu T, Ikezawa T, et al. [A case of pyogenic granuloma in the small intestine]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 96: 1396-1400, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Payson BA, Karpas CM, Exelby P. Intussusception due to pyogenic granuloma of ileum. N Y State J Med 67: 2135-2138, 1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meuwissen SG, Willig AP, Hausman R, Starink TM, Mathus-Vliegen EM. Multiple angiomatous proliferations of ileal stoma following Campylobacter enteritis. Effect of laser photocoagulation. Dig Dis Sci 31: 327-332, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iwakubo A, Tsuda T, Kubota M, Wakabayashi J, Kobayashi K, Morita K. [Diagnostic 99mTc-labeled red blood cells scintigraphy in gastrointestinal tract bleeding from an intestinal pyogenic granuloma]. Kaku Igaku 26: 1439-1443, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hizawa K, Iida M, Matsumoto T, Kohrogi N, Yao T, Fujishima M. Neoplastic transformation arising in Peutz-Jeghers polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum 36: 953-957, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yao T, Nagai E, Utsunomiya T, Tsuneyoshi M. An intestinal counterpart of pyogenic granuloma of the skin. A newly proposed entity. Am J Surg Pathol 19: 1054-1060, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirakawa K, Aoyagi K, Yao T, Hizawa K, Kido H, Fujishima M. A case of pyogenic granuloma in the duodenum: successful treatment by endoscopic snare polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc 47: 538-540, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Eeden S, Offerhaus GJ, Morsink FH, van Rees BP, Busch OR, van Noesel CJ. Pyogenic granuloma: an unrecognized cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Virchows Arch 444: 590-593, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shirakawa K, Nakamura T, Endo M, Suzuki K, Fujimori T, Terano A. Pyogenic granuloma of the small intestine. Gastrointest Endosc 66: 827-828, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chou JW, Lai HC, Lin YC. Image of the month. Pyogenic granuloma of the small bowel diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 7: A26, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stojsic Z, Brasanac D, Kokai G, et al. Intestinal intussusception due to a pyogenic granuloma. Turk J Pediatr 50: 600-603, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuga R, Furuya CK Jr., Fylyk SN, Sakai P. Solitary pyogenic granuloma of the small bowel as the cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 41 (Suppl 2): E76-E77, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nagoya H, Tanaka S, Tatsuguchi A, et al. Rare cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding due to pyogenic granuloma in the ileum detected by capsule endoscopy and treated with double balloon endoscopy. Dig Endosc 22: 71-73, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamashita K, Arimura Y, Saito M, et al. Pyogenic granuloma of the small bowel. Endoscopy 45 (Suppl 2 UCTN): E9-E10, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kikuchi A, Sujino T, Yamaoka M, et al. Pyogenic granuloma of the ileum diagnosed by double-balloon enteroscopy. Intern Med 53: 2057-2059, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirata K, Hosoe N, Imaeda H, et al. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: resection of a pyogenic granuloma of the ileum via double-balloon enteroscopy. Clin J Gastroenterol 7: 397-401, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Misawa S, Sakamoto H, Kurogochi A, et al. Rare cause of severe anemia due to pyogenic granuloma in the jejunum. BMC Gastroenterol 15: 126, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iravani A, Law A, Millward M, Warner M, Sparrow S. Bleeding small intestine pyogenic granuloma on 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med 40: 869-870, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katsurahara M, Kitade T, Tano S, et al. Pyogenic granuloma in the small intestine: a rare cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 47 (Suppl 1 UCTN): E133-E134, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kawasaki K, Kurahara K, Matsumoto T. Pyogenic granuloma of the ileum depicted by small-bowel radiography, capsule endoscopy and double balloon endoscopy. Dig Liver Dis 47: 436, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mizutani Y, Hirooka Y, Watanabe O, et al. Pyogenic granuloma of the small bowel treated by double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 81: 1023-1024, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Korc P, McHenry L. An uncommon cause of chronic upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 84: 524, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Romero Mascarell C, García Pagán JC, Araujo IK, Llach J, González-Suárez B. Pyogenic granuloma in the jejunum successfully removed by single-balloon enteroscopy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 109: 152-154, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castela J, Mao de Ferro S, Ferreira S, Cabrera R, Dias Pereira A. Pyogenic granuloma of the jejunum: an unusual cause of anemia. J Gastrointest Surg 22: 1795-1796, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moreira Silva H, Silva G, Costa E, Lima R, Pereira F. Pyogenic granuloma of the ampulla of Vater: unexpected cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin J Gastroenterol 12: 34-37, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang D, Glover SC, Liu W, Liu X, Lai J. Small bowel pyogenic granuloma with cytomegalovirus infection in a patient with Crohn's disease (report of a case and review of the literature). In Vivo 33: 251-254, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim YS, Chun HJ, Jeen YT, Um SH, Kim CD, Hyun JH. Small bowel capillary hemangioma. Gastrointest Endosc 60: 599, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sasaki M, Nakamura F, Koyama S, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T, Okabe H. Case report: haemangioma of the small intestine complicated by protein-losing gastroenteropathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 13: 387-390, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kavin H, Berman J, Martin TL, Feldman A, Forsey-Koukol K. Successful wireless capsule endoscopy for a 2.5-year-old child: obscure gastrointestinal bleeding from mixed, juvenile, capillary hemangioma-angiomatosis of the jejunum. Pediatrics 117: 539-543, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wardi J, Shahmurov M, Czerniak A, Avni Y. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Capillary hemangioma of small intestine. Gastroenterology 132: 1656, 2084, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang B, Lou Z, Zheng W, Zhang J, Liu J. Capillary hemangioma in the ileum: obscure small-bowel bleeding in an elderly person. Turk J Gastroenterol 29: 520-521, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santos J, Ruiz-Tovar J, Lopez A, Arroyo A, Calpena R. Simultaneous massive low gastrointestinal bleeding and hemoperitoneum caused by a capillary hemangioma in ileocecal valve. Int J Colorectal Dis 26: 1363-1364, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee MH, Yen HH, Chen YY, Chen CJ, Soon MS. Combined capillary hemangioma and angiodysplasia of the ileum: an unusual cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding with preoperative localization by double-balloon endoscopy. Am J Surg 200: e30-e32, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamamoto H, Ogata H, Matsumoto T, et al. Clinical practice guideline for enteroscopy. Dig Endosc 29: 519-546, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, et al. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology 126: 643-653, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, et al. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 102: 89-95, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Handa O, Naito Y, Okayama T, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis of small intestinal diseases. Clin J Gastroenterol 6: 94-98, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]