Abstract

The Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS) is a prospective adoption study of birth parents, adoptive parents, and adopted children (n = 561 adoptees). The original sample has been expanded to include siblings of the EGDS adoptees who were reared by the birth mother and assessed beginning at age 7 (n = 217 biological children), and additional siblings in both the birth and adoptive family homes, recruited when the adoptees were 8 to 15 years old (n = 823). The overall study aims are to examine how family, peer, and contextual processes affect child and adolescent adjustment, and to examine their interplay (mediation, moderation) with genetic influences. Adoptive and birth parents were originally recruited through adoption agencies located throughout the United States following the birth of a child. Assessments are ongoing and occurred in 9-month intervals until the adoptees turned 3 years of age, and in one- to two-year intervals thereafter through age 15. Data collection includes the following primary constructs: child temperament, behavior problems, mental health, peer relations, executive functioning, school performance, and health; birth and adoptive parent personality characteristics, mental health, health, context, substance use, parenting, and marital relations; and the prenatal environment. Findings highlight the power of the adoption design to detect environmental influences on child development and provide evidence of complex interactions and correlations between genetic, prenatal, and environmental influences on a range of child outcomes. The study sample, procedures, and an overview of findings are summarized and ongoing assessment activities are described.

Keywords: adoption, child, longitudinal, sibling, genetic, parenting

Many mental health, neurodevelopmental, and health disorders of adulthood have their roots in childhood (Betts et al., 2016; Copeland et al., 2009; Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2017). According to recent national surveys, the number of children affected by neurodevelopmental disorders is high, and these disorders are associated with real economic and emotional costs (Finkelstein et al., 2010; Lynch & Clarke, 2006; Robb et al., 2011). Recent meta-analyses and studies of nationally representative children show that 13% of children worldwide have at least one current psychiatric disorder (Merikangas et al., 2010; Polanczyk et al., 2015). The lifetime rates of each of these disorders at any time from childhood through adolescence substantially exceed this rate (Perou et al., 2013). Similarly, prevalence rates of childhood obesity present a major public health concern, affecting more than 13.7 million children in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). Based on the public health consequences of mental and physical health problems in childhood and adolescence, the focus of the Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS) has been to better understand their etiology through the use of a prospective “dual-family” adoption study that includes linked adoptive and birth parents and children in both homes.

There is no question that environmental and genetic influences on development operate jointly to impact child development, and that there are complex interactions and correlations between these two important influences (e.g., Reiss, Leve, & Neiderhiser, 2013). For example, family context and parenting processes may be moderated by genetic influences, or, conversely, may moderate genetic influences. Twin, adoption, and molecular genetic studies have found evidence of genotype x environment (GxE) interaction for a range of child and adolescent behavioral, mental health, cognitive, and health outcomes (e.g., Brody et al., 2013; Dick, 2011; Leve et al., 2009; Reiss et al., 1995; Tucker-Drob et al., 2011). In addition, there is evidence that heritable qualities in children influence their social environmental exposures through evocative and self-selection effects (Forget-Dubois et al., 2007; Klahr et al., 2013; McGue et al., 2005; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). Adoption studies have found that heritable child characteristics (e.g., behavioral impulsivity, negative emotionality) influence the parenting that children receive from toddlerhood through late adolescence (Ge et al., 1996; Hajal et al., 2015; Harold et al., 2013a; O’Connor et al., 1998). However, adoption studies prospectively examining social environmental processes from early childhood to adolescence are rare, with this study and the Colorado Adoption Project (Plomin & DeFries, 1985) being the only such studies to date. In the adoption design, similarities between birth parents and the adopted child suggest genetic influences (attributed to shared genes and a lack of shared rearing environments) or prenatal influences (occurring in utero). Associations between adoptive parents’ and adopted children’s characteristics suggest post-natal environmental processes (based on shared rearing environments and the lack of shared genes), although evocative gene-environment correlation (rGE) effects may also cause adoptive parent-child associations.

Each type of genetically informed design has unique strengths. The adoption design’s primary strengths pertain to its ability to identify genetic influences at the whole genome, aggregate level (not specific to particular alleles), its elimination of passive rGE, and its ability to detect evocative rGE. Specifically, because the adoptive parents are genetically unrelated to their adopted children, passive rGE is eliminated and associations between the birth parent(s) and adoptive parent(s) must reflect a heritable effect transmitted from birth parent to the child, which then can evoke a predicted response from the rearing parent. In twin studies and other designs where the rearing parents and child are genetically related, it can be difficult to disentangle the effects of the child’s genes from those of their parents’ when examining associations between parent and child phenotypes, and evocative rGE associations may be confounded by passive rGE effects.

Overview of the Early Growth and Development Study

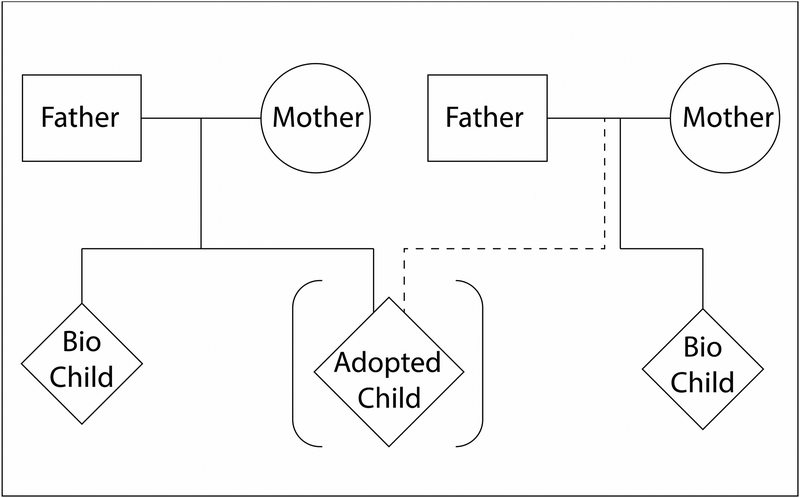

This article provides an update on the goals, results, and plans of the Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS; see Leve et al., 2007; 2013b, for our initial reports). The EGDS started as a prospective adoption study designed to examine the influence of specific features of families, peers, and social contexts on child adjustment, and factors that may mediate the expression of genetic influences or that may be moderated by (or moderate) genetic influences. EGDS has since expanded to include additional children in both the birth parent and adoptive home (see Figure 1) and additional behavioral and health outcomes, as well as developmentally-salient environmental exposures. By focusing on family processes beginning in infancy, the EGDS provides a unique opportunity to detect gene-environment (GE) interplay when first expressed and examine its unfolding over time.

Figure 1.

EGDS “dual-family” adoption study design.

Our theoretical model was derived from research indicating family process predictors of, and continuities within, five life course developmental pathways: internalizing behavior, externalizing behavior, social competence, cognitive skills, and healthy weight. The phenotypic patterns of life course development in each of these pathways are well supported by existing genetic and phenotypic data (e.g., Birch & Davison, 2001; Caspi et al., 1995; Eisenberg et al., 2003; Gilliom & Shaw, 2004). To select phenotypes and associated measures to test our hypotheses, we relied on three types of studies: adoption studies to identify phenotypes that are known to be linked between birth parent and adopted child, and to also be influenced by the environment (e.g., Ge et al., 1996); twin and sibling studies to identify phenotypes that have known genetic and environmental influences (e.g., Petrill et al., 2006); and life course studies to identify how a phenotype might change or evolve across development (e.g., Caspi & Roberts, 2001).

Although these approaches have led to substantial scientific advances in understanding the etiology of child behavioral and health outcomes, this body of research also has limitations that our study can address. For example, most sibling studies include family members that are genetically related, and most twin studies include twins reared together. Both methods can confound putative genetic and environmental effects on development. Adoption studies can address some of these concerns. In addition, most twin and sibling studies do not often permit a comparison of phenotypes across generations, and life course studies without a genetically sensitive component cannot detect whether phenotypic stability or change is based on environmental versus genetic or prenatal influences.

Considered together, however, existing adoption, twin, sibling, and life course research have facilitated the formulation of data-based hypotheses about probable birth parent–adopted child phenotypic similarities and likely environmental influences on these genetically-influenced phenotypes. In addition, selection of constructs and measures for some of our ongoing assessments was guided by a National Institutes of Health cooperative grant, Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO; Gillman & Blaisdell, 2018). ECHO was designed to capitalize on existing studies of children and parents and study five child outcomes: pre, peri-, and postnatal outcomes; obesity; airways health; neurodevelopment; and positive health.

Overall Study Hypotheses

The conceptual model for the EGDS is based on the following general hypotheses: (1) parenting behaviors, marital dynamics, and peer behaviors have main effects on child adjustment (clarifying that data from prior studies of genetically-related family members can be interpreted as environmental effects); (2) heritable characteristics of children evoke specific reactions and interactions from their social environment (e.g., parenting, marital relations, peer behaviors; evocative rGE); (3) environmental main effects are moderated by and moderate genetic influences (GxE), at times offsetting genetically-influenced susceptibility and at times enhancing genetically-influenced strengths; (4) child and parental behaviors show both change and continuity across development, with child behavioral continuity associated with both environmental and genetic influences and the continuity of parenting behavior partially influenced by children’s heritable characteristics; and (5) the environmental context enhances the effects that genetically-influenced child behaviors have on parenting practices (e.g., genetically-influenced effects of child characteristics on parenting may only appear in certain contexts; moderation of evocative rGE). In this model, we hypothesize specific mediating and moderating mechanisms on adjustment along five developmental pathways: externalizing behavior, internalizing behavior, social competence, academic and school performance, and weight trajectories.

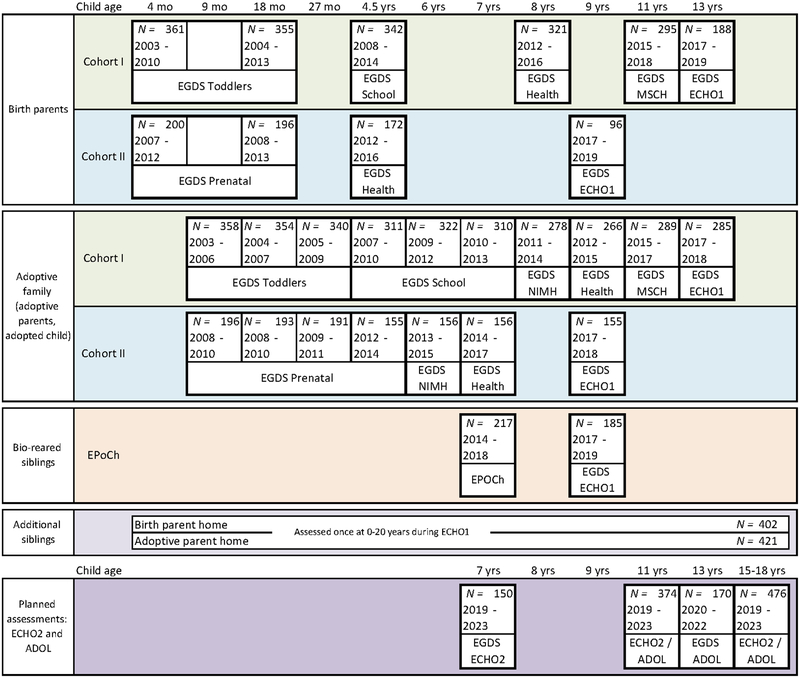

Figure 2 illustrates the interrelation of the studies and the developmental periods covered. EGDS-Toddlers (n = 361) focused on infancy and toddlerhood and is considered Cohort I of EGDS; EGDS-Prenatal is considered Cohort II of EGDS; it expanded EGDS-Toddlers by adding 200 new cases, adding buccal cell collection for candidate gene analyses, and focusing specifically on the role of prenatal influences. EGDS-School was designed to continue assessments of the EGDS-Toddlers participants through the school entry period, with additional data collection on school readiness, academic achievement, and stress reactivity (measured by salivary cortisol collection). EGDS-NIMH focused specifically on child and adoptive parent mental health symptoms and diagnoses and included Cohort I and II children. EGDS-Health examined pathways to healthy weight and obesity through the assessment of children’s and parents’ health promotive behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity, sleep) within Cohort I and II families. EGDS-Middle School (MSCH) continued assessment of the original Cohort I children as they entered middle school. Early Parenting of Children (EPoCh) began as a separate study designed to assess the original birth families who were parenting a 7-year old sibling of the original Cohort I or II adoptee. Finally, EGDS-ECHO1 was designed to collect data on all original EGDS and EPoCh children, and on all additional siblings age 0–20 who were living in either the adoptive or birth home. It served as the precursor to ECHO2, which is now underway and is further described in the Future Plans section of this article. The Future Plans section also describes a second ongoing study with the Cohort I and II adoptees that is focused on pubertal development and hormonal influences on child outcomes (EGDS-ADOL). With the exception of ECHO2 and EGDS-ADOL, assessment activities for the studies shown in Figure 2 are complete.

Figure 2.

Timeline for the EGDS studies and assessments.

Sample Description

The EGDS sample includes 561 linked sets of participants: 561 adopted children, their birth mothers (n = 554), their birth fathers (n = 210), and their adoptive parents (562 adoptive fathers and 569 adoptive mothers; numbers do not sum to 561 mothers/fathers because the sample includes 41 same-sex parent families, and 11 additional adoptive fathers and 3 additional adoptive mothers who entered the family after the original couple adopted the child, recruited in two cohorts. More than half of the children are male (57.2%), and 55.3% of the children are Caucasian, 19.6% are multiracial, 13.2% are Black or African American, 10.9% are Hispanic or Latinx, <1% are Asian, <1% are Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, <1% are American Indian, and <1% are of unknown ethnicity/not reported. The median child age at adoption placement was 2 days (M = 5.58, SD = 11.32; range = 0–91 days). When the study expanded as part of EPoCh and ECHO, siblings living in the original birth and adoptive homes were recruited. Of the siblings recruited into the study, 13% (n = 135) were a full sibling to the adoptee, 43% (n = 435) were a half sibling to the adoptee, and 43% (n = 430) were unrelated to the adoptee. Cohort I and II adopted children’s birthdates ranged from January 2003 to May 2009, EPoCh children’s birthdates ranged from December 2005 to May 2012, and the ECHO additional siblings’ birthdates ranged from August 1996 to December 2018.

Demographic information regarding parent age, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, and income is provided in Table 1. Cohort differences were examined for all demographic variables, and negligible differences were identified. As is indicated by these demographic statistics and was noted in our prior publication (Leve et al., 2013b), EGDS shows the typical pattern of differences in sociodemographic characteristics often found between birth and adoptive parents, with adoptive parents having substantially more advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds than birth parents (DeFries et al., 1994). In addition, it is notable that birth parents’ highest education level completed and household income levels have continued to rise since the start of the study, as would be expected based on their younger age at the time of recruitment into the original study.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Variables | Adoptive Parent 1 | Adoptive Parent 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort I | Cohort II | Combined | Cohort I | Cohort II | Combined | ||

| Mean age at the adopted child’s birth ± SD (yrs) | 37.8 ± 5.5d | 36.8 ± 5.7d | 37.4 ± 5.6 | 38.4 ± 5.8 | 38.1 ± 5.9 | 38.3 ± 5.8 | |

| Race (%) | |||||||

| Caucasian | 91.4 | 92.5 | 91.8 | 90.2 | 90.7 | 90.4 | |

| African American | 3.6 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.9 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | |

| Multiethnic | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | |

| Othera | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | |

| Mean educational levelb last reported by parent ± SD | 5.9 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 1.2 | 5.9 ± 1.2 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 5.7 ± 1.4 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | |

| Less than a high school degree | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | |

| GED degree | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | |

| High school degree | 7.5 | 10.6 | 8.6 | 13.0 | 11.2 | 12.4 | |

| Trade school | 3.9 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 5.4 | |

| 2-yr college or university degree | 9.2 | 5.8 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 6.2 | 6.9 | |

| 4-yr college or university degree | 41.1 | 38.6 | 40.2 | 37.4 | 47.2 | 40.7 | |

| Graduate program | 36.9 | 42.3 | 38.8 | 36.5 | 28.1 | 33.7 | |

| Married at study start (%)c | 98.6 | 97.0 | 98.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Married at last report (%)c | 84.6 | 88.0 | 85.8 | 87.1 | 91.7 | 88.7 | |

| Median annual household income at study start | $70–100Kd | $100K+d | $100K+d | $70–100Kd | $100K+d | $100K+d | |

| Median annual household income at last report | $100–125K | $125–150K | $125–150K | $125–150K | $125–150K | $125–150K | |

| Variables | Birth mother | Birth father | |||||

| Cohort I | Cohort II | Combined | Cohort I | Cohort II | Combined | ||

| Mean age at the adopted child’s birth ± SD (yrs) | 24.1 ± 5.9 | 24.8 ± 6.3 | 24.4 ± 6.0 | 25.4 ± 7.2 | 27.0 ± 8.5 | 26.1 ± 7.8 | |

| Race (%) | |||||||

| Caucasian | 71.1 | 68.4 | 70.1 | 74.6 | 62.7 | 69.9 | |

| African American | 11.4 | 16.8 | 13.3 | 8.7 | 15.7 | 11.5 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 8.7 | 10.8 | 9.6 | |

| Multi-ethnic | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 | |

| Othera | 5.8 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 3.2 | 6.0 | 4.2 | |

| Mean educational levelb last reported by parent ± SD | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | |

| Less than a high school degree | 10.1 | 22.74 | 14.5 | 6.7 | 21.6 | 12.4 | |

| GED degree | 13.0 | 12.4 | 12.8 | 22.5 | 10.8 | 18.0 | |

| High school degree | 31.4 | 36.2 | 33.1 | 38.3 | 44.6 | 40.7 | |

| Trade school | 15.6 | 11.9 | 14.3 | 11.7 | 13.5 | 12.4 | |

| 2-yr college or university degree | 16.1 | 9.2 | 13.7 | 10.8 | 1.4 | 7.2 | |

| 4-yr college or university degree | 10.1 | 7.6 | 9.2 | 8.3 | 6.8 | 7.7 | |

| Graduate program | 3.7 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.5 | |

| Married at study start (%)c | 7.0 | 4.6 | 6.1 | 19.1 | 7.2 | 14.0 | |

| Married at last report (%)c | 53.3 | 51.6 | 52.7 | 56.9 | 50.6 | 54.4 | |

| Median annual household income at study start | < $15K | $15–25K | < $15K | $15–$25K | $15–25K | $15–25K | |

| Median annual household income at last report | $25–40K | $25–40K | $25–40K | $25–40K | $25–40K | $25–40K | |

Note.

Includes Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and unknown.

Mean education level calculated with a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (< high school degree), 2 (GED), 3 (high school degree), 4 (trade school), 5 (2-yr college), 6 (4-yr college), to 7 (graduate program).

Includes marriage, remarriage, and living together in a committed marriage-like relationship.

Statistically significant difference between cohorts at p < .01.

Sample Recruitment and Design Assumptions

Staff at four recruitment sites recruited families in the Mid-Atlantic, the West/Southwest, the Mid-West, and the Pacific Northwest regions of this United States into the study. Recruitment of Cohort I and II birth and adoptive families occurred between March 2003–January 2010, beginning with the recruitment of adoption agencies into the study (N = 45 agencies in 15 states). EGDS participants currently reside in 46 states, the District of Columbia in the US, and in 12 other countries. The project employs separate birth parent and adoptive family recruiters to ensure that project staff do not transfer information between members of the adoption triad. We maintain this separation through all stages of the study, including assessment. In collaboration with the study, each adoption agency appointed a liaison from their organization to perform the initial stages of recruitment into the study.

Agency liaisons identified participants who completed an adoption plan through their agency and met the study’s eligibility criteria: (a) the adoption placement was domestic, (b) placement occurred within 3 months postpartum, (c) the infant was placed with an adoptive family that was not biologically related to the child, (d) there were no known major medical conditions such as extreme prematurity or extensive medical surgeries, and (e) the birth and adoptive parents were able to understand English at the 8th-grade level. All types of adoptive families were eligible for study enrollment (e.g., same-sex parents, single parents, and hearing-impaired parents). Once eligibility criteria were met, 2–4 weeks post placement, the agency liaison mailed a letter describing the study to each eligible adoptive family. Adoptive families were given the opportunity to opt out of future study contact by returning a self-addressed, stamped postcard. Two weeks after the mailing, liaisons called the birth mothers linked to the adoptive families that had not opted out of the study to describe the study and ask for permission to have a recruiter from the study contact her directly. If birth mothers provided permission for EGDS to contact them, the EGDS birth parent recruiter contacted the birth mother. Next, the EGDS adoptive family recruiter attempted to recruit the adoptive family using the contact information provided by the agency. Finally, after the birth mother and adoptive parents were recruited, project staff attempted to recruit the birth father. See Leve et al. (2013b) for recruitment details and a flow chart of the recruitment procedures for Cohort I and II families.

For EPoCh, the eligibility criteria included: (a) birth mother enrolled in EGDS between 2003 and 2009 following the birth of the EGDS adoptee, (b) birth mother was parenting a biological sibling of an EGDS Cohort I or II adoptee, (c) this biological sibling was born between 2005 and 2012. The EPoCh participants were recruited at biological sibling age 7 from an eligible pool of n = 287 children. Of the eligible participants who were not enrolled into EPoCh, 8% were unable to be located; 5% declined participation; 3% were not recruited because the parent was incarcerated, deceased, or the child was removed from the home; 5% verbally agreed to participate but never completed the assessment; and 4% were not recruited because the study ended. Birth parents participating in EPoCh had similar demographic characteristics (race, ethnicity, income, education) as the full sample of EGDS birth parents, with the exception that they were significantly younger t(398) = 4.385, p < .001 than the full sample, likely due to the study inclusion criteria (parenting a 7-year old child at the time of recruitment).

For ECHO1, eligibility criteria included: (a) birth and adoptive parents enrolled in EGDS between 2003 and 2009 following the birth of the EGDS adoptee, (b) family had not previously withdrawn from the study (n = 32 adoptive families and 13 birth families), (c) parents were not deceased (n = 16 birth families), and (c) the original Cohort I adoptee, Cohort II adoptee, EPoCh sibling, or additional children age 0–20 were living in the home. Recruitment resulted in a sample of n = 283 Cohort I adoptees, n = 154 Cohort II adoptees, n = 190 EPoCh siblings, n = 421 additional children in the adoptive family home, and n = 402 additional children in the birth family home.

To assess sampling bias in the recruitment of the original sample of birth and adoptive families, we compared the demographic information between triads who participated in the EGDS (N = 561 triads) with those of the eligible nonparticipants (N = 2,391 triads available for analysis) using data available from the participating agencies. We found minimal systematic sampling biases, suggesting that the EGDS sample is generally representative of the population from which it was drawn (see Leve et al., 2013b for details).

The adoption design rests on several assumptions about the separate influences of genetic and environmental influences on child development. For example, once intrauterine factors such as prenatal alcohol and drug consumption, maternal depression and stress, and exposure to environmental toxins have been considered, similarities between the birth parent and the adopted child are inferred to result from genetic factors. Trends in adoption practices such as openness (contact and knowledge between birth and adoptive families) and selective placement (agency matching of birth and adoptive parent characteristics) can pose a threat to these assumptions and can bias model estimates. For example, adopted children may be more likely to resemble their birth parents (inflating genetic estimates) when birth parents are in direct contact with the child. Thus, we examined the variation in two aspects of the adoption process—openness and selective placement—with our sample of 561 linked EGDS families.

The level of openness was measured by asking birth parents and adoptive parents to report on the amount of contact and knowledge between them. Responses were categorized into seven discrete categories: very closed (no information about the adoptive parents or birth parents), closed (only general information that the agency provided), mediated (written communication only, conducted through an agency), semi-open (exchange of letters and emails, cards, and pictures, but no face-to-face contact), open (visits one to three times per year and communication semi-regularly by telephone, mail, or email), quite open (visits about every other month and frequent communication by telephone, mail, or email), and very open (visits at least once monthly and communication several times a month by telephone, mail, or email). The prevalence of birth and adoptive parents’ ratings for each level of openness during infancy and at their most recent assessment is shown in Table 2. Results show that there are a range of openness levels, and indicate that the level of openness has generally declined as the children age. In addition, birth mothers, adoptive mothers, and adoptive fathers are generally in strong agreement about the level of openness (r = .71–.84; Ge et al., 2008). We include a composite measure of openness in EGDS papers in order to account for this potential confound, although in the majority of papers to date, it has not been significantly associated with most study predictors or outcome variables.

Table 2.

Self-reported Level of Openness in the Adoption at Start of Study (before slash) and Last Report (after slash)

| Level of openness (%) | AP 1 | AP 2 | BM | BF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very closed (1) | 0.2 / 2.5 | 0.0 / 3.6 | 0.4 / 5.9 | 5.1 / 15.9 |

| Closed (2) | 4.5 / 11.8 | 6.1 / 13.3 | 3.4 / 9.5 | 5.1 / 9.0 |

| Mediated (3) | 18.8 / 16.4 | 18.8/16.0 | 12.1 / 13.5 | 11.2 / 8.5 |

| Semi-open (4) | 15.7 / 24.3 | 15.7 / 23.0 | 16.2 / 20.3 | 22.3 / 25.4 |

| Open (5) | 38.5 / 35.5 | 40.0 / 36.3 | 35.1 / 32.7 | 32.5 / 26.5 |

| Quite open (6) | 14.5 / 7.1 | 12.5 / 5.9 | 17.6 / 8.9 | 13.2 / 9.0 |

| Very open (7) | 7.9 / 2.5 | 7.0 / 1.8 | 15.3 / 9.1 | 10.7 / 5.8 |

| Mean openness value | 4.6 / 4.1 | 4.6 / 4.0 | 5.0 / 4.3 | 4.5 / 3.9 |

Note. AP = adoptive parent, BM = birth mother, BF = birth father

To test for selective placement, we correlated birth parent characteristics with adoptive family characteristics that were unlikely to be influenced by evocative effects (e.g., scales of personality, self-worth, executive function, temperament, intelligence, and financial needs). Of 132 comparisons, only 3 were statistically significant at p < .05. Thus, systematic selective placement biases typically have not been detected in the EGDS sample.

Data Collection

Measurement for the EGDS has been guided by five principles: adherence to a theoretical model guiding the domains of assessment between parents and children, utilization of a multimethod multiagent assessment strategy, use of identical or developmentally-comparable measures across assessments to facilitate the examination of change over time, the meticulous separation of research staff collecting data from birth families from those collecting data from adoptive families, and repeated assessment of birth parents to attempt to fully capture genetic influences on development through the reduction of measurement error in the birth parent assessments.

Overview of assessment.

The completed EGDS assessments included questionnaires, in-person interviews, and standardized testing for birth parents, adoptive parents, and children; diagnostic interviews with adoptive parents (about themselves and about the adopted child), with birth parents about themselves, and with EPoCh birth parents about their child; observational interactions (mother-father, mother-child, father-child, and mother-father-child) for all adoptive families and for EPoCh birth families; food and activity diaries for adoptive families; medical records for birth parents and the adopted and birth children; DNA collection via buccal cells for adoptees, adoptive parents, and birth parents and from saliva for EPoCh children; diurnal cortisol measures for adopted children, EPoCh children, and birth parents; teacher questionnaires for EGDS and EPoCh children; and official arrest records for birth parents. The interviews included interviewer-administered questions, which created a context whereby the interviewer could establish rapport with the participant, and computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) that were completed privately by participants to facilitate confidentiality and honest responses. In-person assessments (adoptive family: age 9 months, 18 months, 27 months, and age 4.5, 6, 7, and 8 years; birth parents: 5- and 18-months postpartum and 4.5 years postpartum; and age 7 for EPoCh families) lasted approximately 3–4 hours each and were conducted in a location convenient for the participant, most often at home.

Brief telephone interviews (15 minutes) were conducted for birth and adoptive parents in between the primary in-person assessments. These served as a means of maintaining contact and rapport with participants. Overall, 208 different assessment measures have been administered focusing on the primary theoretical model and aims. A full listing of study measures by age is available at https://egdstudy.org/measures/. De-identified data that are part of ECHO’s common measures will also ultimately be shared on a secure portal for access by the broader research community. Currently, we share existing de-identified data with external colleagues throughout the U.S. and Europe. Procedures for accessing de-identified data are available from the corresponding author and include receipt of a signed data security policy and submission of a detailed project abstract. Our study’s publication policy provides guidelines for approval of new projects, review timelines, and authorship.

Summary of Results

Table 3 provides a summary of some of the main areas that have been examined and a sampling of some of the publications in each area. We continue to place an emphasis on examining environmental influences on child temperament, behavior problems, and psychopathology (General Hypothesis 1), with expansion to areas such as peer relations (Elam et al., 2014; Leve et al., in press) and child obesity and health (Blackwell et al., 2019; Marceau et al., 2019a). Our findings regarding General Hypothesis 1 indicate main effects of parenting (overreactive parenting, responsivity, parenting efficacy, and observed structured guidance), marital hostility, and adoptive parent depressive symptoms (including adoptive fathers) and anxiety on child temperament, behavior, and psychopathology outcomes across infancy, toddlerhood, and childhood. We also published a review paper on the environmental association between maternal depression and child development (Natsuaki et al., 2014). Many of our empirical papers have used longitudinal data and utilized coded observational data on parents or parents and children, where available, to reduce self-report and within-rater bias issues (e.g., Hyde et al., 2016; Roben et al., 2015). In addition, many of our analyses have included both adoptive mothers and fathers, with results typically showing unique effects of fathers (e.g., Bridgett et al., 2018; Harold et al., 2013b; Hails et al., 2018). Although main effects of parenting, marital function, and parent psychopathology are not new to the field of psychology, EGDS is able to show that associations between these family characteristics and child psychosocial adjustment are not attributable to passive gene-environment correlation, and that they can be detected across childhood.

Table 3.

Manuscript Content Areas and Sampling of Representative Manuscripts in Each Area

General Hypothesis 2 examines evocative rGE. As the children in EGDS move out of early childhood and into middle childhood, we are seeing evidence of evocative rGE (e.g., Harold et al., 2013a, Klahr et al., 2017). We also have numerous examples of child effects on a parent characteristic (e.g., Ahmadzadeh et al., 2019), although in the absence of a significant path from a birth parent variable to the child variable, we cannot determine whether these child effects are genetically mediated. We have sought to identify evocative rGE associations in some of our analyses and failed to detect a genetic signal. These null findings could be for several reasons, including, (a) we may not have identified or measured the relevant birth parent variable, including possible incongruence between an adult phenotype and a child phenotype, (b) evocative effects may not appear until later in child development, (c) evocative effects may be masked by interaction effects, as moderated mediation (see Fearon et al., 2015, as an example), (d) we only have birth father data for approximately one-third of our sample, and thus are missing a portion of the potential genetic influences, (e) the child variables we have examined may not show intergenerational genetic transmission, or (f) the genetic influences involved are non-additive. Regardless of the source of the lack of consistent evocative effects, we will continue to test hypothesis-driven questions about evocative rGE as the sample enters adolescence in the coming years.

General Hypothesis 3 examines environmental moderation of genetic influences and genetic moderation of environmental influences (GxE). We have found significant GxE effects during infancy, toddlerhood, and middle childhood for several types of child behavior, including externalizing problems, total behavior problems, and callous-unemotional behavior (e.g., Hyde et al., 2016; Leve et al., 2009; Lipscomb et al., 2012; Roos et al., 2016), attention behavior (Brooker et al., 2011; Leve et al., 2010b), fussiness and anger (Natsuaki et al., 2010; Rhoades et al., 2011), inhibition (Natsuaki et al., 2013b), and positive peer relations (Van Ryzin et al., 2015). We have also found GxE interaction effects on children’s cortisol regulation (Laurent et al., 2013b). Our GxE findings may reflect the fact that in adoption designs, we assess how environmental factors moderate the genetic transmission of parental phenotypes to their children at the age of child measurement. In contrast, twin designs examine the degree to which environmental factors moderate the heritability of a child trait as the time of measurement. These methodological differences may explain the different patterns of GxE findings between the two approaches.

General Hypothesis 4 requires measurement of longitudinal pathways of continuity and change across development in relation to genetic and environmental influences. Our analyses suggest fairly high stability of child behavior, temperament, parenting behavior, and marital behavior across early and middle childhood (e.g., Ahmadzadeh et al., 2019; Lipscomb et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2018; Mannering et al., 2011; Trentacosta et al., 2019), and indicate that changes in parenting are associated with changes in child behavior (Lipscomb et al., 2012; Trentacosta et al., 2019). As the study children enter adolescence, which is a period of significant change in the youth’s social world that requires new parenting strategies, we will continue to examine stability and change in children’s developmental trajectories to examine developmental windows that may be more or less susceptible to environmental influences, and thus garner insights for prevention or intervention development. General Hypothesis 5—to examine moderation of evocative rGE effects—has only been examined in one paper to date (Fearon et al., 2015), with findings suggesting that genetic factors associated with birth mother externalizing psychopathology may evoke negative reactions in adoptive mothers in the first year of life, but only when the adoptive family environment is characterized by marital problems; favorable marriages facilitate positive parental reactions to the same heritable traits. As this study focused on very early childhood, future work will continue to test moderated mediation and mediated moderation as the children enter adolescence.

Overall, the findings to date contribute in novel ways by showing that family environmental variables (e.g., parenting, parental psychopathology, and marital relations) are associated with child adjustment outcomes even when passive rGE effects are removed, and that specific GxE effects can be detected across early and middle childhood. We have some evidence for evocative rGE effects, although such effects have been less prominent than originally hypothesized. The DNA collected as part of EGDS Prenatal was genotyped for a select set of specific genes, consistent with the standards of the time. More recently, in 2018–2019 in EPoCh, we sequenced salivary DNA samples from a subset of children using Illumina microarray technology. We currently have several manuscripts in process using the genotyped data from both studies. Results from our dual-family adoption study are just one source of knowledge about the interplay between genetic and environmental influences on development; there is a need to synthesize findings across multiple design types. As described next, our participation in NIH’s ECHO project is one of our newest efforts to increase the rigor and reproducibility of findings on child behavioral and health outcomes.

Future Plans

Our data collection activities during childhood (EPoCh), late childhood (Cohort II), and early adolescence (Cohort I) were very recently completed. Accordingly, we will continue to examine our original study aims and hypotheses across development, using longitudinal approaches and data from children in Cohort I and II and their siblings, where available. We are particularly interested in testing whether evocative rGE effects become more prominent during adolescence when youth spend more time outside of the family context. We are also interested in identifying environmental influences that help children have positive health outcomes, despite having genetic or prenatal liabilities. We are developing methods to test sibling models that examine rearing and genetic influences based on the complex and nested nature of siblings of different ages residing in two different homes that vary on socio-demographic features (e.g., Natsuaki et al., 2019), and who vary in genetic relatedness to additional children in the home (ranging from sharing no genes for unrelated siblings, to sharing 50% for full siblings and dizygotic twin pairs, to sharing 100% for monozygotic twin pairs).

To pursue these objectives, in addition to continuing to analyze our existing data, we are engaged in two new studies that will include new data for the original EGDS children and their siblings during adolescence. First, in a new study that will assess the Cohort II children at ages 11, 13, and 15 and Cohort I children at age 15, we will explore the interplay among genetic influences, prenatal experiences, pubertal development, and postnatal environment on children’s risk for substance use. This study (EGDS-ADOL) includes the collection of hair samples to measure pubertal hormones and cortisol, and questionnaires for the youth and their parent(s) that measure adolescent behavioral and health outcomes, including substance use and related behaviors, and the family and contextual environment.

Second, as noted earlier, we are part of NIH’s ECHO program and will be collecting data in collaboration with other pediatric cohorts across the United States to learn about early environmental influences on children’s neurodevelopment; positive health; airways health; pre, peri-, and postnatal outcomes; and obesity. Approximately 500 of our adoptees and EPoCh children and 500 of their siblings will complete in-home and web-based assessments at age 7, 11, or 15, depending on the current age of the child, as part of EGDS-ECHO2. In addition to measures of child behavior and health, and of the family and contextual environment, this study will collect a number of biospecimens, including saliva (for genotyping), blood spots, hair, shed teeth, toenail clippings, stool, and urine that together can be used to provide genetic data and index chemical exposures. Our sample of approximately 1,000 children will be part of the larger ECHO aggregate sample of approximately 50,000 children and families. Data will be harmonized across cohorts, and ultimately shared in a de-identified manner with the broader scientific community for access by independent researchers. We are eager to embark on this collaborative effort and to make de-identified data from this study available to a broader range of researchers.

Acknowledgments

We thank the birth and adoptive parents who participated in this study and the adoption agencies who helped recruit study participants. Special gratitude is given to Rand Conger, John Reid, Xiaojia Ge, and Laura Scaramella who contributed to the original study aims; to Sally Guyer for data management; to study coordinators, recruiters, data teams, and assessors; and to our collaborators and co-authors who developed and tested hypotheses using study data.

Financial Support

This project was supported by R01 HD042608, NICHD, NIDA, and OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI Years 1–5: David Reiss; PI Years 6–10: Leslie Leve), R01 DA020585 NIDA, NIMH, and OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI: Jenae Neiderhiser), R01 MH092118, NIMH, NIH, U.S. PHS (PIs: Jenae Neiderhiser and Leslie Leve), R01 DK090264, NIDDK, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI: Jody Ganiban), R01 DA035062, NIDA, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI: Leslie Leve), R56 HD042608, NICHD, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI: Leslie Leve), and UG3/UH3 OD023389, Office of the Director, NIH, U.S. PHS (PIs: Leslie Leve, Jenae Neiderhiser, and Jody Ganiban). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, the Office of the Director, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

References

- Ahmadzadeh YI, Eley TC, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D, … McAdams TA (2019). Anxiety in the family: A genetically informed analysis of transactional associations between mother, father and child anxiety symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 10.1111/jcpp.13068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman C, Neiderhiser JM, Buss KA, Loken E, Moore GA, Leve LD, …Reiss D (2015). The development of early profiles of temperament: Characterization, continuity, and etiology. Child Development, 86(6), 1794–1811. 10.1111/cdev.12417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts KS, Williams GM, Najman JM, & Alati R (2016). Predicting spectrums of adult mania, psychosis and depression by prospectively ascertained childhood neurodevelopment. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 72, 22–29. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, & Davison KK (2001). Family environmental factors influencing the developing behavior controls of food intake and childhood overweight. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 48(4),893–907. 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70347-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell CK, Elliott AJ, Ganiban J, Herbstman J, Hunt K, Forrest CB, & Camargo CA(2019) General health and life satisfaction in children with chronic illness. Pediatrics. 143(6), e20182988 10.1542/peds.2018-2988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blozis SA, Ge X, Xu S, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, … Reiss D (2013). Sensitivity analysis of multiple informant models when data are not missing at random. Structural Equation Modeling, 20(2), 283–298. https://doi.org/101080/10705511.2013.769393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Ganiban JM, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2018). Contributions of mother’s and father’s parenting to children’s self-regulation: Evidence from an adoption study. Developmental Science, 21(6), e12692 https://doi.org/:0.1111/desc.12692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Evans GW, Windle M, … Philibert RA (2013). Supportive family environments, genes that confer sensitivity, and allostatic load among rural African American emerging adults: A prospective analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1), 22–29. 10.1037/a0027829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Alto KM, Marceau K, Najjar R, Leve LD, Ganiban JM, … Neiderhiser JM (2016). Early inherited risk for anxiety moderates the association between father’s child-centered parenting and early social inhibition. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 7(6), 602–615. 10.1017/s204017441600043x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban JM, Leve LD, Shaw DS, & Reiss D (2014). Birth and adoptive parent anxiety symptoms moderate the link between infant attention control and internalizing problems in toddlerhood. Development and Psychopathology, 26(2), 347–359. 10.1017/s095457941300103x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Neiderhiser JM, Kiel EJ, Leve LD, Shaw DS & Reiss D (2011). The association between infants’ attention control and social inhibition is moderated by genetic and environmental risk for anxiety. Infancy, 16(5), 490–507. 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00068.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Neiderhiser JM, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Scaramella LV, & Reiss D (2015). Associations between infant negative affect and parent anxiety symptoms are bidirectional: Evidence from mothers and fathers. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1875 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotnow L, Reiss D, Stover CS, Ganiban J, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, … Stevens HE (2015). Expectant mothers maximizing opportunities: Maternal characteristics moderate multifactorial prenatal stress in the prediction of birth weight in a sample of children adopted at birth. PLOS ONE, 10(11), e0141881 10.1371/journal.pone.0141881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Henry B, McGee RO, Moffitt TE, & Silva PA (1995). Temperamental origins of child and adolescent behavior problems: From age 3 to age 15. Child Development, 66(1), 55–68. 10.2307/1131190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, & Roberts BW (2001). Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry, 12(2), 49–66. 10.1207/s15327965pli1202_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Childhood Obesity Facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/obesity/facts.htm on May 27, 2019.

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, & Angold A (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi CC, Leve LD, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Reiss D, & Neiderhiser JN (in press). Does parental warmth moderate longitudinal associations between infant attention control and children’s inhibitory control? Infant and Child Development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFries JC, Plomin R, & Fulker DW (1994). Nature and nurture during middle childhood. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM (2011). Gene-environment interaction in psychological traits and disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Morris AS, Fabes RA, Cumberland A, Reiser M, … Losoya S (2003). Longitudinal relations among parental emotional expressivity, children’s regulation, and quality of socioemotional functioning. Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 3–19. 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elam KK, Harold GT, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, … Leve LD (2014). Adoptive parent hostility and children’s peer behavior problems: Examining the role of genetically informed child attributes on adoptive parent behavior. Developmental Psychology, 50(5), 1543–1542. 10.1037/a0035470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon RMP, Reiss D, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Scaramella LV, Ganiban JM, & Neiderhiser JM (2015). Child-evoked maternal negativity from 9 to 27 months: Evidence of gene-environment correlation and its moderation by marital distress. Development and Psychopathology, 27(4), 1251–1265. 10.1017/s0954579414000868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein EA, daCosta DiBonaventura M, Burgess SM, & Hale BC (2010). The costs of obesity in the workplace. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 52(10), 971–976. 10.1097/JPM.0b013e3181f274d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget-Dubois N, Boivin M, Dionne G, Pierce T, Tremblay RE, & Pérusse D (2007). A longitudinal twin study of the genetic and environmental etiology of maternal hostile-reactive behavior during infancy and toddlerhood. Infant Behavior and Development, 30(3), 453–465. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaysina D, Fergusson DM Leve LD, Horwood J, Reiss D, Shaw DS, … Harold GT (2013). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring conduct problems: Evidence from 3 independent genetically sensitive research designs. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(9), 956–963. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Cadoret RJ, Neiderhiser JM, Yates W, Troughton E, & Stewart MA (1996). The developmental interface between nature and nurture: A mutual influence model of child antisocial behavior and parent behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 32(4), 574–589. 10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Natsuaki MN, Martin D, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, … Reiss D (2008). Bridging the divide: Openness in adoption and post-adoption psychosocial adjustment among birth and adoptive parents. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(4), 529–540. 10.1037/a0012817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, & Shaw DS (2004). Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 16(2), 313–334. 10.1017/s0954579404044530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman MW, & Blaisdell CJ (2018). Environmental influences on child health outcomes, a research program of the National Institutes of Health. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 30(2), 260–262. 10.1097/mop.0000000000000600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hails KA, Shaw DS, Leve LD, Ganiban JM, Reiss D, Natsuaki MN, & Neiderhiser MN (2018). Interaction between adoptive mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms in risk for children’s emerging problem behavior. Social Development. Online First. 10.1111/sode.12352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajal NJ, Neiderhiser JM, Moore GA, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Harold GT, … Reiss D (2015). Angry responses to infant challenges: Parent, marital, and child genetic factors associated with harsh parenting. Child Development, 86(1), 80–93. 10.1111/cdev.12345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Leve LD, Barrett D, Elam K, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, … Thapar A (2013a). Biological and rearing mother influences on child ADHD symptoms: Revisiting the developmental interface between nature and nurture. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(10), 1038–1046. https://doi.org.10.1111/jcpp.12100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Leve LD, Elam KK, Thapar A, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, … Reiss D (2013b). The nature of nurture: Disentangling passive genotype-environment correlation from family relationship influences on children’s externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1), 12–21. 10.1037/a0031190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Leve LD, & Sellers R (2017). How can genetically informed research help inform the next generation of interparental and parenting interventions? Child Development, 88(2), 446–458. 10.1111/cdev.12742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde L, Waller R, Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban J, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2016). Heritable and non-heritable pathways to early callous unemotional behaviors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(9), 903–901. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Leve LD, Harold GT, Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, & Reiss D (2013). Influences of biological and adoptive mothers’ depression and antisocial behavior on adoptees’ early behavior trajectories. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(5), 723–764. 10.1007/s10802-013-9711-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahr AM, Burt SA, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Ganiban JM, Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM (2017). Birth and adoptive parent antisocial behavior and parenting: A study of evocative gene-environment correlation. Child Development, 88(2), 503–513. 10.111/cdev.12619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahr AM, Thomas KM, Hopwood CJ, Klump KL, & Burt SA (2013). Evocative gene–environment correlation in the mother–child relationship: A twin study of interpersonal processes. Development and Psychopathology, 25(1), 105–118. 10.1017/s0954579412000934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Fisher PA, Marceau K, Harold GT, & Reiss D (2013a). Effects of parental depressive symptoms on child adjustment moderated by hypothalamic pituitary adrenal activity: Within- and between-family risk. Child Development, 84(2), 528–542. 10.1111/j.1497-8624.2012.0159.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Harold GT, & Reiss D (2013b). Effects of prenatal and postnatal parent depressive symptoms on adopted child HPA regulation: Independent and moderated influences. Developmental Psychology, 49(5), 876–886. 10.1037/a0028800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Fisher PA, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2014). Stress system development from age 4.5 to 6: Family environment predictors and adjustment implications of HPA stability versus change. Developmental Psychobiology, 56(3), 340–354. 10.1002/dev.21103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD (2017). Applying behavioral genetic research to inform the prevention of developmental psychopathology: Drawing from the principles of prevention science In Tolan PH, & Leventhal BL (Eds.), Advances in development and psychopathology: Vol 2. Gene–environment transactions in developmental psychopathology: Brain research foundation symposium series (pp. 251–282). New York, NY: Springer; https://doi.org.10.1007/978-3-319-49227-8_13 [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, DeGarmo DS, Bridgett DJ, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Harold GT, … Reiss D (2013a). Using an adoption design to separate genetic, prenatal, and temperament influences on toddler executive function. Developmental Psychology, 49(6), 1045–1057. 10.1037/a0029390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Griffin AM, Natsuaki MN, Harold GT, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban JM, … Reiss D (in press). Longitudinal examination of pathways to peer problems in middle childhood: A siblings-reared-apart design. Development and Psychopathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Harold GT, Ge X, Neiderhiser JM, & Patterson G (2010a). Refining intervention targets in family-based research: Lessons from quantitative behavioral genetics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(5), 516–526. 10.1177/1745691610383506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Harold GT, Ge X, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw D, Scaramella LV, & Reiss D (2009). Structured parenting of toddlers at high versus low genetic risk: Two pathways to child problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(11), 1102–1109. 10.1097/chi.0b013e3181b8bfc0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kerr DCR, Shaw D, Ge X, Neiderhiser JM, Scaramella LV, … Reiss D (2010b). Infant pathways to externalizing behavior: Evidence of Genotype x Environment interaction. Child Development, 81(1), 340–356. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01398.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Ge X, Scaramella LV, Conger RD, Reid JB, Shaw DS, & Reiss D (2007). The Early Growth and Development Study: A prospective adoption design. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 10(1), 84–95. https://10.1375/twin10.1.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Harold GT, Natsuaki MN, Bohannan BJM, & Cresko WA (2018). Naturalistic experimental designs as tools for understanding the role of genes and the environment in prevention research. Prevention Science, 19(1), 68–78. 10.1007/s11121-017-0746-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ganiban J, Natsuaki MN, & Reiss D (2013b). The Early Growth and Development Study: A prospective adoption study from birth through middle childhood. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16(1), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1017.thg.2012.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb S, Becker DR, Laurent H, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, … Leve LD (2018). Examining morning HPA axis activity as a moderator of hostile, over-reactive parenting on children’s skills for success in school. Infant Child Development, 27(4), e2083 10.1002/icd.2083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Laurent H, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2013). Genetic vulnerability interacts with parenting and early care education to predict increasing externalizing behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(1), 70–80. 10.1177/0165025413508708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Leve LD, Harold GT, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ge X, & Reiss D (2011). Trajectories of parenting and child negative emotionality during infancy and toddlerhood: A longitudinal analysis. Child Development, 82(5), 1661–1675. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Scaramella LV, Ge X, … Reiss D (2012). Negative emotionality and externalizing problems in toddlerhood: Overreactive parenting as a moderator of genetic influences. Development and Psychopathology, 24(1), 167–179. 10.1017/s0954579411000757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Moore GA, Beekman C, Perez-Edgar KE, Leve LD, Shaw DS, … Neiderhiser JM (2018). Developmental patterns of anger from infancy to middle childhood predict problem behaviors at age 8. Developmental Psychology, 54(11), 2090–2100. 10.1037/dev0000589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch FL, & Clarke GN (2006). Estimating the economic burden of depression in children and adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31(6), 143–151. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammen MA, Moore GA, Scaramella LV, Reiss D Ganiban JM, Shaw DS, … Neiderhiser JM (2015). Infant avoidance during a tactile task predicts autism spectrum behaviors in toddlerhood. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(6), 575–587. 10.1002/imhj.21539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammen MA, Moore GA, Scaramella LV, Reiss D, Shaw DS, Leve LD, & Neiderhiser JM (2016). Infant patterns of reactivity to tactile stimulation during parent-child interaction. Infant Behavior Development, 44, 121–132. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannering AM, Harold GT, Leve LD, Shelton KH, Shaw DS, Conger RD, … Reiss D (2011). Longitudinal associations between marital instability and child sleep problems across infancy and toddlerhood in adoptive families. Child Development, 82(4), 1252–1256. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01594.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Abel EA, Duncan RJ, Moore PJ, Leve LD, Reiss D, … Ganiban JM (2019a). Longitudinal associations of sleep duration, morning and evening cortisol, and BMI during childhood. Obesity, 27(4), 645–652. 10.1002/oby.22420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, De Araujo-Greecher M, Miller ES, Massey SH, Mayes LC, Ganiban J … Neiderhiser JM (2016). The perinatal risk index: Early risks experienced by domestic adoptees in the United States. PLOS One, 11(3): e0150486 10.1371/journal.pone.0150486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Hajal N, Leve LD, Reiss D, Shaw DS, Ganiban JM, … Neiderhiser JM (2013a). Measurement and associations of pregnancy risk factors with genetic influences, postnatal environmental influences, and toddler behavior. International Journal of Behavior Development, 37(4), 366–375. https://doi.org.10.1177/0165025413489378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Laurent HK, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, Leve LD (2015). Combined influences of genes, prenatal environment, cortisol, and parenting on the development of children’s internalizing versus externalizing problems. Behavior Genetics, 45(3), 268–282. 10.1007/s10519-014-9689-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Ram N, Neiderhiser JM, Laurent HK, Shaw DS, Fisher PA, … Leve LD (2013b). Disentangling the effects of genetic, prenatal, and parenting influences on children’s cortisol. Stress, 16(6), 607–615. 10.3109/10253890.2013.825766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Rolan E, Leve LD, Ganiban JM, Reiss D, Shaw DS, … Neiderhiser JM (2019b). Parenting and prenatal risk as moderators of genetic influences on conduct problems during middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 55(6), 1164–1181. 10.1037/dev0000701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DM, Leve LD, Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, & Ge X (2011). Toward a greater understanding of openness: A report from the Early Growth and Development Study. National Council of Adoption’s Factbook V, 471–477. [Google Scholar]

- Massey SH, Lieberman DZ, Reiss D, Leve LD, Shaw DS, & Neiderhiser JM (2011). Association of clinical characteristics and cessation of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy. The American Journal on Addictions, 20(2), 143–150. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00110.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SH, Mroczek DK, Reiss D, Miller ES, Jakubowski JA, Graham EK, … Neiderhiser JM (2018). Additive drug-specific and sex-specific risks associated with co-use of marijuana and tobacco during pregnancy: Evidence from 3 recent developmental cohorts (2003–2015). Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 68, 97–106. 10.1016/j.ntt.2018.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SH, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Leve LD, Ganiban JM, & Reiss D (2012). Maternal self concept as a provider and cessation of substance use during pregnancy. Addictive Behaviors, 37(8), 956–961. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SH, Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM, Leve LD, Shaw DS, & Ganiban JM (2016). Maternal personality traits associated with patterns of prenatal smoking and exposure: Implications for etiologic and prevention research. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 53, 48–54. 10.1016/j.ntt.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams TA, Rijsdijk FV, Neiderhiser JM, Narusyte J, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, … Eley TC (2015). The relationship between parental depressive symptoms and offspring psychopathology: Evidence from a children-of-twins study and an adoption study. Psychological Medicine, 45(12), 2583–2594. 10.1017/s0033291715000501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Leve LD, & Pears KC (2016). Preschool executive functions in the context of family risk In Griffin JA, Freund LS, & McCardle P (Eds.), Executive function in preschool age children: Integrating measurement, neurodevelopment and translational research (pp. 241–257). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 10.1037/14797-011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Elkins I, Walden B, & Iacono WG (2005). Perceptions of the parent-adolescent relationship: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology, 41(6), 971–984. 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, & Koretz DS (2010). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics, 125(1), 75–81. 10.1542/peds.2008-2598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Ge X, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Conger RD, … Reiss D (2010). Genetic liability, environment, and the development of fussiness in toddlers: The roles of maternal depression and parental responsiveness. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1147–1158. 10.1037/a0019659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Leve LD, Harold GT, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ganiban J, … Reiss D (2013a). Transactions between child social wariness and observed structured parenting: Evidence from a prospective adoption study. Child Development, 84(5), 1750–1765. 10.1111/cdev.12370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Scaramella LV, Ge X, & Reiss D (2013b). Intergenerational transmission of risk for social inhibition: The interplay between parental responsiveness and genetic influences. Development and Psychopathology, 25(1), 261–274. 10.1017/s0954579412001010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, Harold GT, Shaw DS, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2019). Siblings reared apart: A sibling comparison study of rearing environment differences. Developmental Psychology, 55(6), 1182–1190. 10.1037/dev0000710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban JM, Harold GT, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2014). Raised by depressed parents: Is it an environmental risk? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(4), 357–367. 10.1007/s10567-014-0169-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Marceau K, de Araujo-Greecher M, Ganiban JM, Mayes LC, Shaw DS, … Leve LD (2016). Estimating the roles of genetic risk, perinatal risk, and marital hostility on early childhood adjustment: Medical records and self-report. Behavior Genetics, 46(3), 334–352. 10.1007/s10519-016-9788-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Deater-Deckard K, Fulker D, Rutter M, & Plomin R (1998). Genotype–environment correlations in late childhood and early adolescence: Antisocial behavioral problems and coercive parenting. Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 970–981. 10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton CK, Neiderhiser JM, Leve LD, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Reiss D, & Ge X (2010). Influence of parental depressive symptoms on adopted toddler behaviors: An emerging developmental cascade of genetic and environmental effects. Development and Psychopathology, 22(4), 803–818. 10.1017/s0954579410000477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Grabow A, Khurana A, Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, … Leve LD (2017). Using adoption-biological family design to examine associations between maternal trauma, maternal depressive symptoms, and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Development and Psychopathology, 29(5), 1707–1720. 10.1017/s0954579417001341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, et al. (2013). Mental health surveillance among children — United States, 2005–2011. MMWR Supplements, 62(2), 1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrill SA, Deater-Deckard K, Thompson LA, DeThorne LS, & Schatschneider C (2006). Reading skills in early readers: Genetic and shared environmental influences. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(1), 48–55. 10.1077/00222194060390010501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, & DeFries JC (1985). Origins of individual differences in infancy: The Colorado Adoption Project. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, & Rohde LA (2015). Annual Research Review: A meta‐analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 345–365. 10.1111/jcpp.12381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D & Leve LD (2007). Genetic expression outside the skin: Clues to mechanisms of Genotype × Environment interaction. Development and Psychopathology, 19(4), 1005–1027. 10.1017/s0954579407000508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D Leve LD, & Neiderhiser JM (2013). How genes and the social environment moderate each other. American Journal of Public Health, 103(s1), S111–S121. 10.2105/ajph.2013.301408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Leve LD, & Whitesel A (2009). Understanding links between birth parents and the child they have placed for adoption: Clues for assisting adopting families and for reducing genetic risk? In Wrobel GM & Neil E (Eds.), International advances in adoption research for practice (pp. 119–146). New York: John Wiley; 10.1002/9780470741276.ch6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Plomin R, Hetherington EM, Neiderhiser JM (1995). The relationship code: Genetic and social analyses of adolescent development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben JD, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2016). Warm parenting and effortful control in toddlerhood: independent and interactive predictors of school-age externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(6), 1083–1096. 10.1007/s10802-015-0096-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades KA, Leve LD, Harold GT, Mannering AM, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, … Reiss D (2012). Marital hostility and child sleep problems: Direct and indirect associations via hostile parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(4), 488–498. 10.1037/a0029164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades K,A, Leve LD, Harold GT, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, & Reiss D (2011). Longitudinal pathways from marital hostility to child anger during toddlerhood: Genetic susceptibility and indirect effects via harsh parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(2), 282–291. 10.1037/a0022886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb JA, Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Foster EM, Molina BS, Gnagy EM, & Kuriyan AB (2011). The estimated annual cost of ADHD to the US education system. School Mental Health, 3(3), 169–177. 10.1007/s12310-011-9057-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roben CKP, Moore GA, Cole PM, Molenaar P, Leve LD, Shaw DS, … Neiderhiser JM (2015). Transactional patterns of maternal depressive symptoms and mother–child mutual negativity in an adoption sample. Infant and Child Development, 24(3), 322–342. 10.1002/icd.1906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos LE, Fisher PA, Shaw DS, Kim HK, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, … Leve LD (2016). Inherited and environmental influences on a childhood co-occurring symptom phenotype: Evidence from an adoption study. Development and Psychopathology, 2891), 111–125. 10.1017/s0954579415000322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, & McCartney K (1983). How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype→ environment effects. Child Development, 54(2), 424–435. 10.2307/1129703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, & McEwen BS (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA, 301, 2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJ, Kennedy M, Kumsta R, Knights N, Golm D, Rutter M, … & Kreppner J (2017). Child-to-adult neurodevelopmental and mental health trajectories after early life deprivation: The young adult follow-up of the longitudinal English and Romanian Adoptees study. The Lancet, 389, 1539–1548. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30045-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CS, Connell C, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Scaramella LV, Conger R, & Reiss D (2012). Relationship among marital hostility, father’s hostile parenting and toddler aggression in adoptive families. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 401–409. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02510.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CS, Zhou Y, Kiselica A, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, … Reiss D (2016). Marital hostility, hostile parenting, and child aggression: Associations from toddlerhood to school-age. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 55(3), 235–242. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CS, Zhou Y, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, & Reiss D (2015). The relationship between genetic attributions, appraisals of birth mothers’ health, and the parenting of adoptive mothers and fathers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 41, 19–27. 10.1016/j.appdev.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraban L, Shaw DS, Leve LD, Natsuaki MN, Ganiban J,M, Reiss D, & Neiderhiser JM (2018). Parental depression, overreactive parenting, and early childhood externalizing problems: Moderation by social support. Child Development. Online First. 10.1111/cdev.13027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraban L, Shaw DS, Leve LD, Wilson MN, Dishion TJ, Natsuaki M, … Reiss D (2017). Maternal depression and parenting in early childhood: Contextual influence of marital quality and social support in two samples. Developmental Psychology, 53(3), 436–449. 10.1037/dev0000261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Waller R, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, Ganiban JM, … Hyde LW (2019). Callous-unemotional behaviors and harsh parenting: Reciprocal association across early childhood and moderation by inherited risk. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(5), 811–823. 10.1007/s10802-018-0482-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker-Drob EM, Rhemtulla M, Harden KP, Turkheimer E, & Fask D (2011). Emergence of a gene× socioeconomic status interaction on infant mental ability between 10 months and 2 years. Psychological Science, 22(1), 125–133. 10.1177/0956797610392926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Natsuaki MN, & Reiss D (2015). Genetic influences can protect against unresponsive parenting in the prediction of child social competence. Child Development, 86(3), 667–680. 10.1111/cdev.12335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban JM, Reiss D, Leve LD, Hyde LW (2016). Heritable temperament pathways to early callous-unemotional behaviors. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(6), 475–482 https://doi.10.1192/bjp.bp.116.181503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]