Abstract

Purpose

Inherited pathogenic variants in PALB2 are associated with increased risk of breast and pancreatic cancer. However, the functional and clinical relevance of many missense variants of uncertain significance (VUS) identified through clinical genetic testing is unclear. The ability of patient-derived germline missense VUS to disrupt PALB2 function was assessed to identify variants with potential clinical relevance.

Methods

The influence of 84 VUS on PALB2 function was evaluated using a cellular homology directed DNA repair (HDR) assay and VUS impacting activity were further characterized using secondary functional assays.

Results

Four (~5%) variants (p.L24S,c.71T>C; p.L35P,c.104T>C; pI944N,c.2831T>A; and p.L1070P,c.3209T>C) disrupted PALB2-mediated HDR activity. These variants conferred sensitivity to cisplatin and a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor and reduced RAD51 foci formation in response to DNA damage. The p.L24S and p.L35P variants disrupted BRCA1–PALB2 protein complexes, p.I944N was associated with protein instability, and both p.I944N and p.L1070P mislocalized PALB2 to the cytoplasm.

Conclusion

These findings show that the HDR assay is an effective method for screening the influence of inherited variants on PALB2 function, that four missense variants impact PALB2 function and may influence cancer risk and response to therapy, and suggest that few inherited PALB2 missense variants disrupt PALB2 function in DNA repair.

Keywords: breast cancer, variant of uncertain significance (VUS), PALB2, homologous recombination repair, PARP inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

The repair of double-strand breaks (DSBs) by homologous recombination (HR) has been established as an important barrier to the development of cancer. The two most prominent members of this family of tumor suppressor genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, encode proteins that have been linked to breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer through inherited loss-of-function variants. Inherited pathogenic variants in the PALB2 gene that inactivate the PALB2 protein have also been associated with high risk of breast cancer and pancreatic cancer, whereas further studies are needed to establish the relevance to ovarian cancer.1–4 PALB2 loss-of-function variants are associated with lifetime risks of breast cancer of 24% to 54%, depending on the extent of family history of breast cancer.5 In addition, biallelic loss-of-function variants in PALB2 result in Fanconi anemia.6 A number of studies have also analyzed the occurrence of germline PALB2 loss-of-function variants in breast cancer and estimated frequencies ranging from 0.6% to 3.9% in population-based breast cancer cases and high-risk breast cancer families, respectively.1,7

PALB2 encodes an 1186–amino acid residue protein with an amino terminal coiled-coil domain, central chromatin-associated motif, and C-terminal WD40 repeats.8 PALB2 is an important interaction partner of both BRCA1 and BRCA2 that is also required for HR repair of DSBs. BRCA1 interacts with the coiled-coil motif at the N-terminus of PALB2,9 whereas binding of BRCA2 has been mapped to WD40 repeats at the C-terminus of PALB2.10 Through interactions with RAD5111–13 PALB2 stimulates RAD51-mediated HR. Disruption of the PALB2-RAD51 interaction through deleterious variants leads to functional defects in HR repair.11,14,15

While protein-truncating variants clearly abrogate PALB2 function and lead to increased cancer risk, much less is known about the contribution of missense variants of uncertain significance (VUS) to cancer development. Many unique PALB2 VUS have been identified by germline and somatic clinical and research testing of cancer patients and tumors. Many of these are reported in the PALB2 Leiden Open Variation Database (LOVD) (https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/variants/PALB2/unique) and in ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). Currently, only missense variants in the PALB2 start codon have been classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic by clinical testing laboratories (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). In addition, the p.L35P variant has been shown to disrupt the HR activity of PALB2, confer sensitivity to platinum agents and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, and to segregate with breast cancer in a family with a history of the disease.15 The rest of the identified PALB2 missense variants remain unclassified. In this study, we evaluated the influence of 84 patient-derived missense variants on PALB2 function using a cellular reporter assay for HR repair of DSBs. We identified three new missense variants that disrupted HR repair, conferred sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, inhibited formation of RAD51 foci in response to DNA damage, and displayed altered cellular localization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture

The U2OS osteosarcoma (HTB-96) from ATCC was maintained in McCoy's 5A supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). HEK293T and HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. The mouse mammary tumor cell line B400 (Palb2-/-;Trp53-/-) was previously described.16 Cells were grown in DMEM/F-12 media supplemented with 5 µg/ml insulin, 5 ng/ml EGF, 5 ng/ml cholera toxin, 10% FBS, and antibiotics. Cell lines were grown at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and routinely tested for mycoplasma.

Homology directed repair (HDR) assay

Each variant was introduced into a HA-FLAG-tagged full-length PALB2 complementary DNA (cDNA) expression in the pOZC plasmid by site-directed mutagenesis using pfu turbo. Variants were verified by Sanger sequencing. Cotransfection of PALB2 expression constructs and the I-SceI expression plasmid into B400/DR-GFP reporter cells was performed at a 5:1 molar ratio using Xtremegene 9 transfection reagent (Roche). At least two independent clones containing each variant were analyzed in duplicate. PALB2 expression and transfection efficiency was verified by western blotting. Green fluorescence protein (GFP) expressing cells were quantified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Fold increases in GFP-positive cells, which are equivalent to HDR fold change, were normalized and rescaled relative to a 1:5 ratio derived from the p.Y551X pathogenic variant control and the wild-type PALB2 control.

Cas9/mClover-LMNA HDR assay

The CRISPR Clover-LMNA HDR assay was adapted from refs. 17 and 18. U2OS cells were seeded and transfected with siCtrl or PALB2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Supplementary Information) for a final concentration of 50 nM, using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours post-transfection, 1 × 106 cells were retransfected with 1 μg of pCR2.1-CloverLMNAdonor, 1 μg pX330-LMNAgRNA1, 1 μg pcDNA3 empty vector or the indicated siRNA-resistant flag-tagged PALB2 construct (Supplementary Information), 0.1 g of piRFP670-N1 (used as transfection control), and 200 pmol of siRNA using the 4D-Nucleofector X (Lonza).19 After 48 hours, cells were replated on glass coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and expression of mClover-LMNA (indicative of successful HDR) was assayed by fluorescence microscopy. Data represent the mean percentages (± SEM) of mClover-LMNA–positive cells over the iRFP670-positive population from five independent experiments (total n > 500 iRFP-positive cells/condition).

Mammalian two-hybrid assay

A Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) and BRCA1 wild-type (aa residues 1315–1863) fusion construct (GAL4DBD-BRCA1),20 and a GAL4DBD-BRCA2 wild-type (aa residues 1–60) construct10 were previously generated. VP16 AD-PALB2 N-terminal wild-type (aa residues 1–319) and VP16 AD-PALB2 C-terminal wild-type (aa 859–1186) constructs were generated20 and PALB2 variants were introduced into the wild-type constructs using the QuickChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All generated constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Mammalian two-hybrid assays were conducted using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). PALB2 N- or C-terminal constructs (wild-type or variants) were cotransfected into HEK293FT cells with GAL4DBD-BRCA1 or BRCA2 wild-type constructs, the pG5Luc reporter vector, and a pGR-TK internal control and luciferase activity was measured. These cells were not silenced for endogenous PALB2. PALB2-L21A and A1025R variants were used as negative controls.14,21 The statistical significance of effects on binding relative to WT-PALB2 was determined using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test.

Protein coimmunoprecipitation

Each variant was expressed in nonsilenced HEK293T cells using the HA-FLAG-tagged full-length PALB2 pOZC plasmid. After 48 hours the cells were exposed to 5 Gy ionizing radiation. Cells were lysed in NETN buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, and 300 mM NaCl after 5 hours. Lysates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma). Beads were washed with NETN buffer and boiled in Laemli sample and supernatants were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Western blotting was performed with antibodies against human BRCA1 (EMD-Millipore), BRCA2 (Couch Lab), HA (Covance), PALB2 (Bethyl), and RAD51 (Cell Signaling).

Protein half-life

HEK293T cells transfected with PALB2 constructs were treated with 40 µg/mL cyclohexamide for 0 to 180 minutes. Cells were snap frozen and lysed with NETN buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, and 300 mM NaCl. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and western blotted using anti-HA (Covance) and tubulin (Sigma) (loading control) antibodies. Images were visualized on an Odyssey Fc system (LiCOR) and quantitated using Image Studio software to determine rates of protein degradation relative to control.

Immunofluorescence

Live cell imaging and microirradiation studies of HeLa cells transfected with peYFP-C1-PALB2 WT or variant constructs were carried out with a Leica TCS SP5 II confocal microscope. To monitor the recruitment of YFP-PALB2 to laser-induced DNA damage sites, cells were microirradiated in the nucleus for 200 ms using a 405-nm ultraviolet (UV) laser and imaged every 30 seconds for 15 minutes. Fluorescence intensity of YFP-PALB2 at DNA damage sites relative to an unirradiated nuclear area was quantified (Supplemental Materials). Cyclin A–positive HeLa cells treated with siCtrl and siRNA against PALB2 were complemented with wild-type and mutant FLAG-tagged PALB2 expression constructs, exposed to 2 Gy of γ-IR, incubated for 6 hours, and subjected to immunofluorescence for RAD51 foci. HeLa cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed with tris-buffered saline (TBS), and fixed again with ice-cold methanol for 5 minutes at −20 °C. Cells were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the anti-RAD51 (1:7000, B-bridge International, 70-001) and anticyclin A (1:400, BD Biosciences, 611268), and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the Alexa Fluor 568 goat antirabbit (Invitrogen, A-11011) and Alexa Fluor 647 goat antimouse (Invitrogen, A-21235) secondary antibodies. Z-stack images were acquired on a Leica CTR 6000 microscope and the number of RAD51 foci per cyclin A–positive cells expressing the indicated YFP-PALB2 constructs was scored with Volocity software v6.0.1 (Perkin–Elmer Improvision). Results represent the mean (± SD) of three independent trials (n = 50 cells per condition). HEK293T cells transfected with PALB2 expression constructs were also subjected to immunofluorescence for PALB2 using the monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma) and the Alexa Fluor 568 goat antimouse (Life Technologies) secondary antibody.

Viability assay

PALB2 variants were introduced into B400 cells using mCherry-pOZC expression vector and flow cytometry for Cherry-red was performed to select for cells expressing PALB2. Sorted cells were plated in 96-well plates and exposed to increasing amounts of Olaparib or cisplatin and incubated for a period of 5 days. Presto Blue (Invitrogen) was added and incubated for 1–2 hours before measuring fluorescence intensity on a Cytation 3 microplate reader (BioTek).

RESULTS

Selection of PALB2 variants for functional studies

Missense variants throughout PALB2 have been identified in individuals with breast and other cancers. Here we took a systematic approach to understand the influence of patient-derived PALB2 missense variants on its function. A total of 84 PALB2 patient-derived missense variants reported in ClinVar, COSMIC, and the PALB2 LOVD database were selected based on the probability of pathogenicity score predicted using the VEST3.0 in silico prediction model (http://jhu.technologypublisher.com/technology/24805) (Table 1) (40 of 84 with rankscore probabilities of being deleterious >0.70 and 44 of 84 with rankscore <0.70)22 (Table 1). In contrast, the M-CAP23 in silico prediction model, which has recently been recommended for variant prioritization,24 identified 14 variants with probabilities >0.70, whereas the REVEL25 predictor identified 21 variants with probabilities >0.70 (Table 1). Only ten variants had probabilities >0.70 for all three models. In addition, seven pathogenic variants that truncate the PALB2 protein at various positions were selected as a series of loss-of-function (negative) controls.

Table 1.

Homology directed repair activity and predicted deleterious effects of 84 PALB2 VUS

| HGVS cDNA | HGVS protein | 1 letter code | HDR fold change | SE | VEST3a | M-CAPa | REVELa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.3306C>G | p.Ser1102Arg | S1102R | 7.7 | 0.15 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.45 |

| c.3307G>A | p.Val1103Met | V1103M | 7.7 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| c.3449T>G | p.Leu1150Arg | L1150R | 7.5 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.62 |

| c.1145G>T | p.Ser382Ile | S382I | 7.3 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.07 |

| c.1250C>A | p.Ser417Tyr | S417Y | 7.2 | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.57 | 0.65 |

| c.23C>T | p.Pro8Leu | P8L | 7.1 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.16 |

| c.2200A>T | p.Thr734Ser | T734S | 6.9 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.46 |

| c.232G>A | p.Val78Ile | V78I | 6.6 | 0.80 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| c.3428T>C | p.Leu1143Pro | L1143P | 6.6 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.39 | 0.56 |

| c.629C>T | p.Pro210Leu | P210L | 6.5 | 1.55 | 0.21 | – | 0.28 |

| c.2590C>T | p.Pro864Ser | P864S | 6.4 | 0.96 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.18 |

| c.3056T>C | p.Val1019Ala | V1019A | 6.4 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.57 |

| c.2873A>C | p.Gln958Pro | Q958P | 6.2 | 1.39 | 0.84 | 0.69 | 0.56 |

| c.2993G>A | p.Gly998Glu | G998E | 6.0 | 0.13 | 0.44 | – | 0.61 |

| c.26T>A | p.Leu9His | L9H | 5.8 | 0.10 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.45 |

| c.925A>G | p.Ile309Val | I309V | 5.8 | 1.15 | 0.01 | – | 0.08 |

| c.2597G>T | p.Gly866Val | G866V | 5.6 | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.65 | 0.37 |

| c.1846G>C | p.Asp616His | D616H | 5.4 | 0.13 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.68 |

| c.1010T>C | p.Leu337Ser | L337S | 5.3 | 0.46 | 0.50 | – | 0.11 |

| c.2148T>A | p.Asn716Lys | N716K | 5.3 | 0.84 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.06 |

| c.3433G>C | p.Gly1145Arg | G1145R | 5.2 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.58 |

| c.1732A>G | p.Ser578Gly | S578G | 5.2 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.10 |

| c.3179G>C | p.Cys1060Ser | C1060S | 5.2 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.51 | 0.77 |

| c.1189A>T | p.Thr397Ser | T397S | 5.2 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.63 |

| c.3296C>G | p.Thr1099Arg | T1099R | 5.1 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.36 | 0.51 |

| c.1421G>A | p.Ser474Asn | S474N | 5.1 | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| c.3249G>C | p.Glu1083Asp | E1083D | 5.1 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| c.1676A>G | p.Gln559Arg | Q559R | 5.0 | 1.21 | 0.00 | – | 0.05 |

| c.3492G>T | p.Trp1164Cys | W1164C | 5.0 | 0.32 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.74 |

| c.101G>A | p.Arg34His | R34H | 5.0 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.38 |

| c.2792T>C | p.Leu931Pro | L931P | 5.0 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.77 |

| c.3307G>C | p.Val1103Leu | V1103L | 5.0 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.08 |

| c.1238C>A | p.Thr413Lys | T413K | 5.0 | 0.08 | 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.74 |

| c.2807T>C | p.Leu936Ser | L936S | 5.0 | 0.60 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.76 |

| c.3500C>T | p.Thr1167Ile | T1167I | 4.9 | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.37 |

| c.1190C>T | p.Thr397Ile | T397I | 4.9 | 0.32 | 0.86 | 0.61 | 0.73 |

| c.1222T>C | p.Tyr408His | Y408H | 4.9 | 0.27 | 0.81 | 0.63 | 0.68 |

| c.2234A>G | p.Lys745Glu | K745E | 4.9 | 0.57 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.02 |

| c.3128G>C | p.Gly1043Ala | G1043A | 4.9 | 0.49 | 0.73 | 0.37 | 0.59 |

| c.100C>T | p.Arg34Cys | R34C | 4.9 | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| c.3404G>A | p.Gly1135Glu | G1135E | 4.9 | 0.08 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.76 |

| c.3356T>C | p.Leu1119Pro | L1119P | 4.9 | 0.01 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.76 |

| c.3342G>C | p.Glu1114His | Q1114H | 4.9 | 0.71 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.20 |

| c.2794G>A | p.Val932Met | V932M | 4.9 | 0.44 | 0.57 | – | 0.36 |

| c.3494C>T | p.Ser1165Leu | S1165L | 4.9 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.69 |

| c.3418T>G | p.Trp1140Gly | W1140G | 4.9 | 0.29 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| c.3520G>A | p.Gly1174Arg | G1147R | 4.8 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| c.83A>G | p.Tyr28Cys | Y28C | 4.8 | 0.24 | |||

| c.2816T>G | p.Leu939Trp | L939W | 4.8 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.68 | 0.68 |

| c.2755G>A | p.Val919Ile | V919I | 4.8 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.19 |

| c.1600T>G | p.Ser534Ala | S534A | 4.7 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.04 |

| c.956C>A | p.Ser319Tyr | S319Y | 4.7 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.11 |

| c.3262C>T | p.Pro1088Ser | P1088S | 4.7 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.25 | 0.55 |

| c.3508C>T | p.His1170Tyr | H1170Y | 4.7 | 0.10 | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.36 |

| c.3132A>C | p.Gln1044His | Q1044H | 4.7 | 0.10 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.53 |

| c.109C>T | p.Arg37Cys | R37C | 4.7 | 0.32 | 0.72 | – | 0.60 |

| c.505C>A | p.Leu169Ile | L169I | 4.7 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.19 |

| c.90G>T | p.Lys30Asn | K30N | 4.6 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.26 |

| c.3320T>C | p.Leu1107Pro | L1107P | 4.6 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.22 | 0.24 |

| c.2852C>T | p.Ser951Phe | S951F | 4.6 | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.25 |

| c.2289G>C | p.Leu763Phe | L763F | 4.6 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.22 |

| c.2612A>G | p.Asp871Gly | D871G | 4.5 | 0.16 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.80 |

| c.109C>A | p.Arg37Ser | R37S | 4.5 | 0.23 | 0.84 | – | 0.48 |

| c.2014G>C | p.Glu672Gln | E672Q | 4.4 | 0.39 | 0.04 | – | 0.07 |

| c.1847A>G | p.Asp616Gly | D616G | 4.4 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.61 |

| c.3191A>G | p.Tyr1064Cys | Y1064C | 4.4 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.75 |

| c.398C>G | p.Ser133Thr | S133T | 4.4 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.24 |

| c.2810G>A | p.Gly937Glu | G937E | 4.4 | 0.02 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.73 |

| c.110G>A | p.Arg37His | R37H | 4.1 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.42 |

| c.3278T>C | p.Ile1093Thr | I1093T | 4.0 | 0.16 | 0.78 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| c.3061G>A | p.Gly1021Arg | G1021R | 4.0 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.76 |

| c.1226A>G | p.Tyr409Cys | Y409C | 4.0 | 0.32 | 0.89 | 0.61 | 0.75 |

| c.2840T>C | p.Leu947Ser | L947S | 4.0 | 0.10 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.70 |

| c.3073G>A | p.Ala1025Thr | A1025T | 3.9 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.36 |

| c.2798G>A | p.Cys933Tyr | C933Y | 3.8 | 0.18 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 0.77 |

| c.2841G>T | p.Leu947Phe | L947F | 3.7 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.66 |

| c.2792T>G | p.Leu931Arg | L931R | 3.6 | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.69 | 0.83 |

| c.3539T>C | p.Ile1180Thr | I1180T | 3.6 | 0.01 | 0.84 | 0.60 | 0.66 |

| c.899C>T | p.Thr300Ile | T300I | 3.6 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.15 |

| c.3089C>T | p.Thr1030Ile | T1030I | 3.0 | 0.32 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.74 |

| c.3549C>A | p.Tyr1183Ter | Y1183X | 2.4 | 0.22 | |||

| c.3209T>C | p.Leu1070Pro | L1070P | 1.7 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.76 |

| c.71T>C | p.Leu24Ser | L24S | 1.7 | 0.34 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.43 |

| c.2831T>A | p.Ile944Asn | I944N | 1.5 | 0.16 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| c.1653T>A | p.Tyr551ter | Y551X | 1.0 | 0.00 | |||

| c.751C>T | p.Gln251Ter | Q251X | 0.8 | 0.13 | |||

| c.104T>C | p.Leu35Pro | L35P | 0.8 | 0.14 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.68 |

| c.2145_2146delT | p.Asp715Glufs*2 | D715E fs | 0.6 | 0.07 | |||

| c.3497delG | p.Gly1166Valfs*25 | G1166V f | 0.6 | 0.15 | |||

| c.3362delG | p.Gly1121Valfs*3 | G1121V f | 0.5 | 0.05 | |||

| c.3323delA | p.Tyr1108Serfs*16 | Y1108S fs | 0.5 | 0.03 |

cDNA complementary DNA, HDR homology directed repair, HGVS Human Genome Variation Society.

aRankscore predicted probability of deleterious effects on protein activity between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates a confident prediction of a damaging effect on protein function; HDR fold change scaled 1 to 5 relative to Y551X and wild-type PALB2.

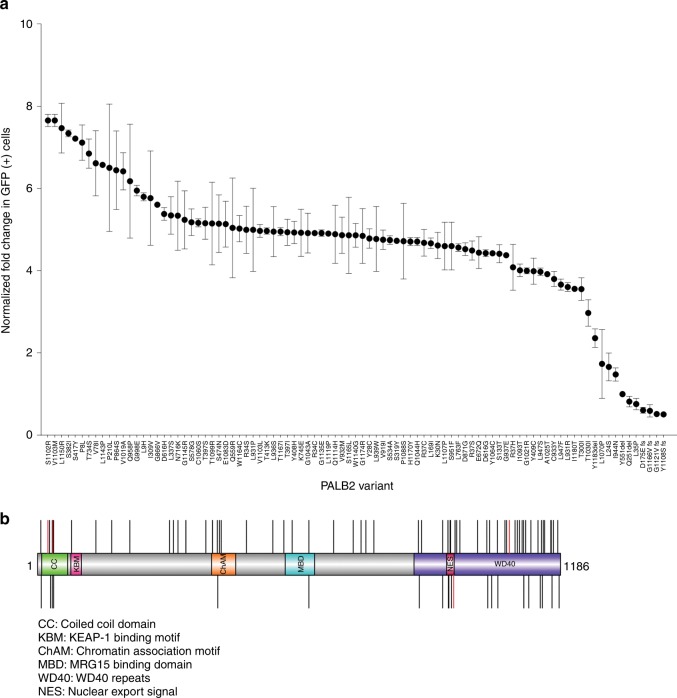

Homology directed repair (HDR) assay

The DR-GFP HDR DNA repair reporter assay was used to assess the influence of 84 missense and seven protein-truncating variants on reconstitution of homology directed repair in PALB2-deficient B400 mouse mammary tumor cells.16 Full-length wild-type (WT) or variant PALB2 constructs were cotransfected with plasmid expressing I-SceI into B400 cells containing a stably integrated DR-GFP reporter construct that contains a GFP gene interrupted by the I-SceI endonuclease site, along with an adjacent inactive GFP gene. Expression of all variants was verified by western blotting (data not shown). Repair of I-SceI induced DSBs by PALB2-dependent HDR yielded GFP-positive cells that were quantified by flow cytometry. Results for individual PALB2 variants were normalized relative to WT-PALB2 and the p.Tyr551ter (p.Y551X) truncating variant on a 1:5 scale with the fold change in GFP-positive cells for WT set at 5.0 and fold change GFP-positive cells for p.Y551X set at 1.0. The p.L24S (c.71T>C), p.L35P (c.104T>C), p.I944N (c.2831T>A), and p.L1070P (c.3209T>C) variants and all protein-truncating frame-shift and deletion variants tested were deficient in HDR activity, with normalized fold change <2.0 (approximately 40% activity) (Fig. 1a). In addition, the p.Y1183X variant that truncates the last three residues of the C-terminal β-propeller domain of PALB2 displayed a normalized fold change in the HR assay of 2.36. All other variants displayed normalized fold change >2.9. To confirm the influence of the PALB2 variants on HDR activity, all four variants defective in HDR in B400 cells were also evaluated using a CRISPR-LMNA HDR assay.19 Endogenous PALB2 in U2OS cells was silenced with siRNA and complemented with siRNA-resistant mutant constructs. WT-PALB2 restored 50% of HDR activity, measured as mean relative percentage of mClover-LMNA expressing cells, while none of the four variants missense variants restored more than 5% activity (Figure S1). The p.L24S, p.L35P, p.I944N, and p.L1070P variants consistently disrupted PALB2 HDR activity and, therefore, further analysis was focused on these variants.

Fig. 1.

Homology directed repair assay of PALB2 variants. (a) Plot of all variants assayed in homologous recombination (HR) repair assay. Results for each independent assay are scaled 1–5 relative to the p.Y551X negative control and wild-type PALB2 positive control. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SE) of independent replicates. (b) Illustration of the PALB2 protein (amino acids 11–1183) showing position of functional domains. Deleterious variants (red) and no functional impact variants (black) are shown as vertical lines above and below the protein. GFP green fluorescence protein.

Mammalian two-hybrid assay of BRCA1 and BRCA2 interactions

Variants p.L21A and p.L35P are known to disrupt the interaction between the N-terminus of PALB2 and BRCA1,14,15 whereas p.A1025R is known to disrupt the interaction between the C-terminus of PALB2 and BRCA2.21 These findings provide a possible mechanistic explanation for the HR deficiency associated with PALB2 missense variants located in protein–protein interaction surfaces. On this basis the influence of p.L24S, p.I944N, and p.L1070P on interactions between PALB2 and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins were evaluated using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter mammalian two-hybrid assay in HEK293FT cells. PALB2 p.L21A and p.L35P were used as loss-of-function (negative) controls for BRCA1 and p.A1025R was used as a negative control for the interaction with BRCA2.14,21 p.L24S significantly reduced interaction with BRCA1 relative to WT-PALB2 (p < 0.01) similarly to the p.L21A and p.L35P controls (Figure S2). In addition p.I944N and p.L1070P significantly disrupted the mammalian two-hybrid interactions (p < 0.0001) between the C-terminus of PALB2 and BRCA2 similarly to p.A1025R (Figure S2).

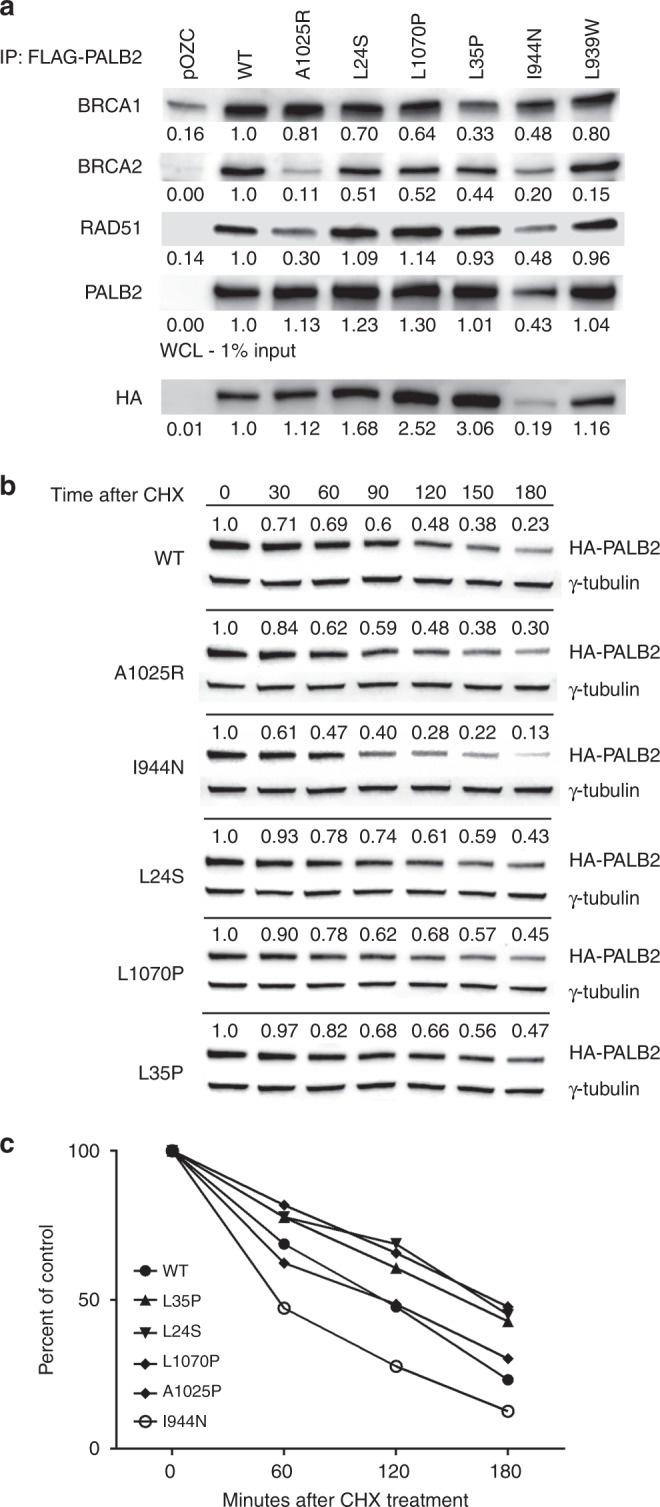

DNA damage-dependent PALB2 protein complexes

Because the p.L24S, p.I944N, and p.L1070P missense variants influenced HR activity and mammalian two-hybrid assays, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed to determine whether these variants also disrupted interactions between full-length PALB2 and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins. HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-HA-PALB2 constructs were exposed to 5 Gy ionizing radiation (IR) and PALB2 proteins were immunoprecipitated from cellular lysates with anti-FLAG beads. Quantitation of western blots for the various proteins suggested that the p.A1025R negative control had reduced ability to form DNA damage-induced complexes with BRCA2 and RAD51, the p.L35P negative control significantly diminished complex formation with BRCA1 and BRCA2, and p.L939W representing variants with no HDR functional impact had no effect on BRCA1, BRCA2, and RAD51 complex formation (Fig. 2a and Table S1). The p.L24S and p.L1070P variants both partially reduced PALB2 complex formation with BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Fig. 2a). Similarly, normalization of western blot signals for p.I944N to account for low expression levels (Fig. 2 and Table S1) showed reduced PALB2 complex formation with BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Fig. 2.

Influence of PALB2 variants on protein complex formation and protein half-life. (a) Western blot analysis of PALB2-interacting proteins after coimmunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged PALB2 from HEK293T cells transiently transfected with PALB2 wild-type (WT) and variants. Whole cell lysate (WCL) shows levels of PALB2 expression. (b) Western blot analysis of PALB2 protein after indicated periods of incubation in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX) to define protein half-life. (c) Quantitation of PALB2 protein half-life using ImageJ at indicated time points.

PALB2 protein stability

Because the p.I944N mutant exhibited low levels of expression in HEK293T cells, the influence of each variant on protein stability was assessed. HEK293T cells expressing wild-type or variant PALB2 constructs were treated with 40 µg/ml cycloheximide to halt protein synthesis and PALB2 levels were measured over time by western blotting. The protein half-life of WT-PALB2 and the p.A1025R negative control was estimated at 114 minutes and 116 minutes, respectively (Fig. 2b). In contrast, p.I944N exhibited a half-life of 54 minutes (Fig. 2b, c). Interestingly, the effect appeared to be cell type–specific because p.I944N was expressed at similar levels as WT-PALB2 in the B400 cells used for the HDR assay (Figure S1). In contrast to the p.I944N, the p.L24S (t1/2 = 167 minutes), p.L35P (t1/2 = 172 minutes), and p.L1070P (t1/2 = 167 minutes) mutants displayed increased stability relative to WT-PALB2 (Fig. 2c).

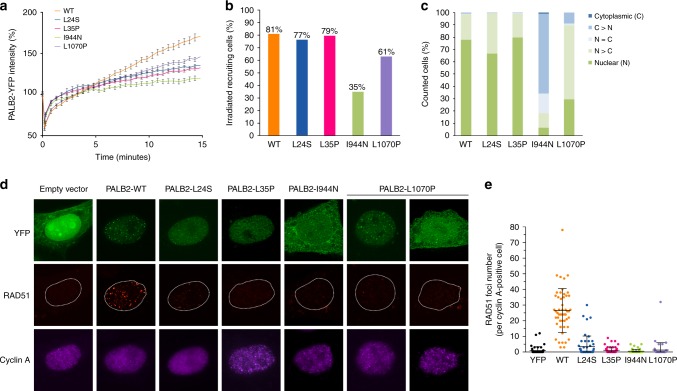

Cellular localization of PALB2 and assessment of RAD51 foci formation

Next, the influence of the variants on cellular localization of PALB2 was assessed. Yellow fluorescence protein (YFP) intensities at sites of laser-induced DNA damage were measured at multiple time points in cells expressing WT and variant forms of YFP-tagged PALB2 to assess rates of PALB2 recruitment to sites of DNA damage. These time course measurements demonstrated considerable recruitment defects with fluorescence intensities that did not exceed 30% of WT level for p.I944N, 50% for p.L24S and p.L35P, and 65% for p.L1070P at 15 minutes postirradiation (Fig. 3a). In addition, the proportion of cells showing recruitment of p.I944N (35%) and p.L1070P (61%) to DSBs was considerably lower than the approximately 80% of cells expressing WT, p.L24S and p.L35P (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, WT-PALB2, p.L24S, and p.L35P primarily localized in the nuclei of cells, whereas p.I944N localized primarily in the cytoplasm, and p.L1070P was most often found equally distributed in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 3c). Because an inability to form RAD51 foci at the sites of DSBs is a hallmark of HR deficiency, we also evaluated the influence of the PALB2 variants on localization of RAD51 to DNA damage repair foci. Cells expressing YFP-tagged PALB2 constructs were exposed to 2 Gy γ-IR and subjected to immunofluorescence staining for RAD51 and cyclin A to identify G2-phase cells with RAD51 foci. WT-PALB2 was associated with robust formation of damage-induced RAD51 foci, whereas the four variants were associated with defective foci formation (Fig. 3d, e). The reduced number of RAD51 foci for each variant was consistent with the results from the HR DR-GFP reporter assays.

Fig. 3.

Influence of PALB2 variants on response to DNA damage. (a) Recruitment of full-length yellow fluorescence protein (YFP)-tagged PALB2 (PALB2-YFP) wild-type (WT) and variants to sites of laser-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) at indicated time points. (b) Proportion of cells expressing PALB2 WT and variants with localization of PALB2-YFP to DSBs. (c) Nucleocytoplasmic distribution of wild-type PALB2-YFP and variants as indicated. (d) Immunofluorescence analysis of PALB2-YFP and RAD51 foci formation in cyclin A–positive HeLa cells after exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) (2 Gy). Cells were treated with PALB2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) cells to deplete endogenous PALB2. (e) Quantification of RAD51 foci in cyclin A–positive cells expressing PALB2-YFP WT and variants. Results are from three independent experiments.

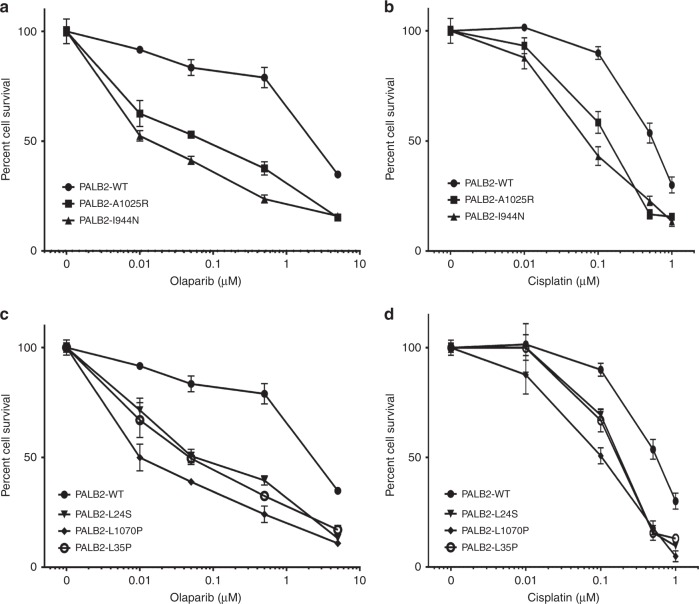

Sensitivity to DNA damaging agents

HR defects have been associated with sensitivity to platinum agents and PARP inhibitors. Thus, the influence of the PALB2 mutants on response to cisplatin and the PARP inhibitor olaparib was evaluated. PALB2-deficient B400 cells expressing WT-PALB2 and the four variants were treated with a range of concentrations of cisplatin or olaparib and cell viability was measured after 5 days using a fluorescence resazurin-based assay. Cells reconstituted with WT-PALB2 showed substantially less sensitivity to olaparib than cells expressing p.A1025R and p.I944N (Fig. 4a). Similar results were observed for cisplatin treatment, although the difference in sensitivity was less pronounced (Fig. 4b). p.L24S, p.L1070P, and p.L35P were also associated with greater sensitivity to olaparib (Fig. 4c) and cisplatin (Fig. 4d) than WT-PALB2. Taken together, all of the selected mutants with HR defects exhibited greater sensitivity to DNA damaging agents than WT-PALB2.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity to DNA damaging agents. Survival of mouse mammary tumor B400 cells reconstituted with PALB2 wild-type (WT) and variants following exposure to varying doses of olaparib (a, c), and cisplatin (b, d).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we described the effects of PALB2 missense variants on DNA repair activity using a cell-based assay that measures HR activity. We showed that Palb2 (and Trp53) deficient mouse mammary tumor B400 cells can be complemented with wild-type human PALB2 to rescue HDR repair and then utilized this approach to conduct a systematic screen of 84 missense variants in all regions of PALB2. We identified three missense variants (p.L24S, p.L1070P, and p.I944N), along with the previously reported p.L35P variant, that disrupted PALB2 HDR activity in B400 cells and verified these findings with a CRISPR-LMNA HDR assay in human U2OS cells and a RAD51 foci formation assay. In addition we used a series of cell-based and biochemical assays to show that each of the three variants disrupted HDR via a distinct mechanism. Specifically, p.L24S had reduced BRCA1 binding and protein complex formation, p.I944N had reduced protein stability and mislocalized to the cytoplasm, and L1070P had altered cellular localization. Finally, we showed that these three variants conferred increased sensitivity to cisplatin and olaparib.

The HDR assay yielded HDR scores of ≤1.7, which equates to 34% activity, for four missense variants and all truncating variants, other than Y1183X. As all four missense in this range had deleterious effects in several other assays, we chose 34% as a threshold for deleterious variants and HDR scores of 2.4 or 48% activity as a threshold for hypomorphic variants. However, clinically classified variants based on family and other data sources are needed as controls to validate these thresholds. Importantly, p.L337S, p.G998E, p.E672Q, and p.Q559R have minor allele frequencies in the gnomAD European non-Finnish population of 1.95%, 2.19%, 2.92%, and 8.88% respectively, suggesting that these variants are not associated with substantially increased risk of cancer. Of these, p.E672Q had the lowest HDR score of 4.4. Thus, hypomorphic variants with partial effects on HDR function in this assay, ranging from 1.7 to possibly as high as 4.4, may be associated with some increased risk of breast cancer. Further studies with the other functional assays reported here may also provide some further insight into the effects of these variants on PALB2 function and on thresholds for pathogenicity.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays showed that the p.I944N, p.L1070P, and p.L24S variants diminished the PALB2 interaction with BRCA1 and BRCA2 similarly to p.L35P, which has been reported to disrupt the interaction with BRCA1 and p.A1025R that disrupts the interaction with BRCA2.15 Direct mammalian two-hybrid assays also suggested that all of these variants disrupted interactions between PALB2 N- and C-terminal domains and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

The influence of the p.I944N variant on protein half-life may account in part for the impact of this variant on HDR activity. However, the impact of the increased stability of the p.L24S and p.L1070P variants on protein function is less clear. It is possible that increased stability of PALB2 due to these variants results in prolonged retention of PALB2 at sites of DNA damage and stalled replication forks, delayed clearance of DNA repair intermediates, and subsequent defects in HR repair. While interesting from a mechanistic perspective, studies focused on understanding the possible impact of increased stability on PALB2 activity and HR repair are beyond the scope of this study. Mislocalization of PALB2 is likely to have a direct effect on HR repair. Both the p.I944N and p.L1070P variants cause retention of PALB2 in the cytoplasm, reduced recruitment of PALB2 to laser-induced sites of DNA damage in the nucleus, and reduced formation of DNA damage-induced RAD51 foci. Interestingly, each of the PALB2 variants failed to rescue sensitivity to olaparib and cisplatin in Palb2- and Trp53-deficient mouse tumor cells. Thus, at least for this small set of PALB2 variants, defective HR repair is consistent with cisplatin and PARP inhibitor sensitivity. This finding suggests that human tumors containing these variants may also exhibit hypersensitivity to these agents.

Clinical genetic testing has identified a large number of PALB2 missense variants of uncertain clinical significance, many of which are listed in the ClinVar database. These VUS create significant uncertainty for patients in terms of risks of developing breast and other cancers. No methods currently exist for classifying the clinical relevance of VUS in PALB2. While the functional assays reported here provide strong evidence that these variants disrupt PALB2 function and cellular HR responses to DNA damage, these assays have not been validated relative to known pathogenic and nonpathogenic missense variants, and the sensitivity and specificity of each assay are not known. Thus, it is not certain that the p.L24S, p.I944N, and p.L1070P missense variants confer increased risks of breast and other cancers. Furthermore, the functional assays are based on expression of PALB2 cDNAs and do not account for the possibility that variants may alter PALB2 splicing leading to altered proteins and/or modified expression levels. As such, the results of the functional assays should be used with caution when attempting to interpret the pathogenicity of these variants. However, functional assays have been used for characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 missense variants. Because of the availability of substantial numbers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants that have been defined as nonpathogenic or pathogenic using family studies, it has been possible to calibrate these assays to cancer risk, define the sensitivity and specificity of the assays, and to classify large numbers of variants.20,26,27 Perhaps as more family-based data are collected and variant classification guidelines proposed by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)28 are applied, it will be possible to establish nonpathogenic and pathogenic standards and to use functional assays in combination with other data sources to establish the clinical significance of PALB2 VUS. While in silico prediction models such as VEST3, M-CAP, and REVEL represent one such source of data, the poor concordance between the HDR activity scores and the VEST3, M-CAP, and REVEL predictions resulting in low specificity for deleterious variants suggest that sequence-based in silico prediction may not be a useful method for variant assessment.

In summary, we report on the identification of three new PALB2 missense variants that are deficient in HR activity. It remains to be determined whether HDR deficiency as measured by in vitro assays and hypersensitivity to DNA damaging therapeutic agents is predictive of the clinical significance and cancer risks associated with germline versions of these variants. Models linking functional activity to clinical disease will be developed in the future as more functionally defective variants in PALB2 and additional family-based data showing segregation of variants with cancer are identified.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant CA116167, a National Cancer Institute (NCI) specialized program of research excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer to the Mayo Clinic (CA116201), and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (FJC), the Ministère de l’Économie de la Science et de l'Innovation du Québec through Genome Québec and the Quebec Breast Cancer Foundation (J.-Y.M./J.S.). The project was also supported by a grant from the Ministère de l'Économie, de la Science et de l'Innovation du Québec through the PSR-SIIRI-949 program (J.-Y.M./J.S) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (foundation grant to J.-Y.M). J.S. is a Canada Research Chair in Oncogenetics and J.-Y.M. is a Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé (FRQS) Chair in genome stability.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41436-019-0682-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Couch FJ, Shimelis H, Hu C, et al. Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1190–1196. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lilyquist J, LaDuca H, Polley E, et al. Frequency of mutations in a large series of clinically ascertained ovarian cancer cases tested on multi-gene panels compared to reference controls. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147:375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu C, Hart SN, Polley EC, et al. Association between inherited germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes and risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2018;319:2401–2409. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu C, LaDuca H, Shimelis H, et al. Multigene hereditary cancer panels reveal high-risk pancreatic cancer susceptibility genes. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2:1–28. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoniou AC, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz M, Group PI. Breast cancer risk in women with PALB2 mutations in different populations. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e375–376. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid S, Schindler D, Hanenberg H, et al. Biallelic mutations in PALB2 cause Fanconi anemia subtype FA-N and predispose to childhood cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:162–164. doi: 10.1038/ng1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadei S, Norquist BM, Walsh T, et al. Contribution of inherited mutations in the BRCA2-interacting protein PALB2 to familial breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2222–2229. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducy M, Sesma-Sanz L, Guitton-Sert L, et al. The Tumor suppressor PALB2: inside out. Trends Biochem Sci. 2019;44:226–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang F, Fan Q, Ren K, Andreassen PR. PALB2 functionally connects the breast cancer susceptibility proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1110–1118. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia B, Sheng Q, Nakanishi K, et al. Control of BRCA2 cellular and clinical functions by a nuclear partner, PALB2. Mol Cell. 2006;22:719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JY, Singh TR, Nassar N, et al. Breast cancer-associated missense mutants of the PALB2 WD40 domain, which directly binds RAD51C, RAD51 and BRCA2, disrupt DNA repair. Oncogene. 2014;33:4803–4812. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buisson R, Dion-Cote AM, Coulombe Y, et al. Cooperation of breast cancer proteins PALB2 and piccolo BRCA2 in stimulating homologous recombination. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1247–1254. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dray E, Etchin J, Wiese C, et al. Enhancement of RAD51 recombinase activity by the tumor suppressor PALB2. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1255–1259. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sy SM, Huen MS, Chen J. PALB2 is an integral component of the BRCA complex required for homologous recombination repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7155–7160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811159106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foo TK, Tischkowitz M, Simhadri S, et al. Compromised BRCA1-PALB2 interaction is associated with breast cancer risk. Oncogene. 2017;36:4161–4170. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huo Y, Cai H, Teplova I, et al. Autophagy opposes p53-mediated tumor barrier to facilitate tumorigenesis in a model of PALB2-associated hereditary breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:894–907. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pauty J, Couturier AM, Rodrigue A, et al. Cancer-causing mutations in the tumor suppressor PALB2 reveal a novel cancer mechanism using a hidden nuclear export signal in the WD40 repeat motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:2644–2657. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castroviejo-Bermejo M, Cruz C, Llop-Guevara A, et al. A RAD51 assay feasible in routine tumor samples calls PARP inhibitor response beyond BRCA mutation. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10:e9172.. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauty J, Usuba R, Cheng IG, et al. A vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent sprouting angiogenesis assay based on an in vitro human blood vessel model for the study of anti-angiogenic drugs. EBioMedicine. 2018;27:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods NT, Golubeva V, et al. Functional assays provide a robust tool for the clinical annotation of genetic variants of uncertain significance. NPJ Genom Med. 2016;1:16001.. doi: 10.1038/npjgenmed.2016.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliver AW, Swift S, Lord CJ, Ashworth A, Pearl LH. Structural basis for recruitment of BRCA2 by PALB2. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:990–996. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter H, Douville C, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Karchin R. Identifying Mendelian disease genes with the variant effect scoring tool. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(Suppl 3):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-S3-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jagadeesh KA, Wenger AM, Berger MJ, et al. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1581–1586. doi: 10.1038/ng.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson D, Lassmann T. A phenotype centric benchmark of variant prioritisation tools. NPJ Genom Med. 2018;3:5. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ioannidis NM, Rothstein JH, Pejaver V, et al. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:877–885. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guidugli L, Shimelis H, Masica DL, et al. Assessment of the clinical relevance of BRCA2 missense variants by functional and computational approaches. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hart SN, Hoskin T, Shimelis H, et al. Comprehensive annotation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 missense variants by functionally validated sequence-based computational prediction models. Genet Med. 2019;21:71–80. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0018-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.