Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hucMSC-derived exosomes) can repair injured endometrial epithelial cells (EECs).

Methods

HucMSC-derived exosomes and mouse primary EECs were isolated and purified. EECs were exposed to oxygen and glucose deprivation for 2 h followed by reoxygenation to mimic injury. After oxygen and glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R), hucMSC-derived exosomes were added to the EEC culture medium. After 24 h of co-treatment, cell viability and cell death were tested by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium assay and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay, respectively. The expression of proinflammatory cytokines was tested by real-time PCR, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and Western blot to investigate the potential mechanism.

Results

Compared with the control group, 5, 10, and 15 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes significantly attenuated cell viability decrease and inhibited LDH release of injured EECs, but 1 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes had no effect on either cell viability or LDH release. Real-time PCR and ELISA analysis revealed that 10 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes significantly inhibited the release of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and increased tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA) in injured EECs. In addition, 10 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes significantly inhibited toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A (RelA) expression in injured EECs.

Conclusions

In OGD/R-induced injured EECs, hucMSC-derived exosomes efficiently improved the cell viability, reduced cell death, and exhibited anti-inflammatory properties against OGD/R.

Keywords: Exosome, Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells, Endometrial epithelial cells, Injury

Introduction

Embryo implantation is a key step in the success of IVF-ET. Successful implantation mainly depends on two factors: embryo quality and endometrial status. It has been reported that endometrial characteristics are a prognostic factor for IVF outcomes [1, 2]. For example, thin endometrium, which always means poor endometrial receptivity, has been thought to be associated with poor IVF success rates [3], and endometrium damage is a common cause of female infertility. Asherman’s syndrome (AS) is characterized by severe damage of the endometrium, which accounts for 25–30% of uterine infertility [4]. Some interventions have been reported to increase implantation rates by improving the endometrial receptivity, including hormonal treatment, immunotherapy, and endometrial scratching [5, 6]. However, some studies have demonstrated that endometrial infusion of human chorionic gonadotropin or granulocyte colony–stimulating factor does not improve implantation rates [7–9]. A recent study demonstrated that endometrial scratching prior to embryo transfer did not result in a higher live birth rate compared with no intervention among women undergoing ART [10].

Stem cell therapy has been shown to contribute to repair and regeneration of the endometrium. It has been reported that injection of autologous stem cells derived from bone marrow and menstrual blood into the uterine or uterine blood vessels could regenerate the endometrium and facilitate conception [11, 12]. A recent study demonstrated that human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hucMSCs) loaded onto collagen scaffolds could significantly increase the endometrial thickness of AS patients without engraftment of the transplanted cells. The study indicated that this benefit of hucMSCs may be attributable to their secreted factors instead of engraftment and differentiation into functional cells [13]. Some studies have demonstrated that the mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) mediate tissue repair through paracrine actions [14–16]. Recently, exosomes have attracted attention as new regulators of cell-to-cell communication. Several studies have demonstrated the therapeutic effects of stem cell–derived exosomes for different disorders, revealing their potential for cell-free therapy [17–19].

In the present study, we investigate whether hucMSC-derived exosomes can repair injured endometrial epithelial cells (EECs). Oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD)/reoxygenation (OGD/R) was applied to cultured EECs to mimic injury. The effect of hucMSC-derived exosomes was analyzed by evaluating the cell viability and cell death of EECs that suffered OGD/R exposure. Furthermore, the possible underlying molecular signaling mechanisms were also investigated.

Materials and methods

Animals

Female CD1 mice were purchased from the Beijing Vital River Experimental Animals Centre. The mice were fed under light-controlled conditions (12:12-h light-dark cycle). The mice had access to food and water ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Experiments of Zhengzhou University, China.

Preparation of hucMSC-derived exosomes

hucMSC-derived exosomes were purified by differential ultracentrifugation, as described previously [20]. In brief, primary or passage-2 hucMSCs preserved by Henan Key Laboratory of Stem Cell Differentiation and Modulation (Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, Zhengzhou, Henan, China) were seeded and expanded in 10-cm culture dish in 10 mL Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplanted with 10% exosome-deleted fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). When passages 3 or 4 reached 80–90% density, the completed culture medium was replaced with 10 mL DMEM supplanted with 10% exosome-deleted FBS. Exosome-deleted FBS was obtained by centrifugation at 100,000×g at 4 °C for 8 h. After 48 h, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 300×g for 10 min to remove the detached cells. Every 100 mL supernatant was pooled and filtered through 0.22-μm filters (Merck Millipore) and then centrifuged at 100,000×g at 4 °C for 90 min to pellet the exosomes. The crude pellets were resuspended in PBS and centrifuged at 100,000g at 4 °C for 90 min. Purified exosomes were quantified using a micro BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and confirmed by transmission electron microscopy.

Cell isolation and culture

Endometrial epithelial cells were enzymatically isolated from the mouse uterus as previously described [21], with some modifications. In brief, uterine horns were obtained from immature mice (3.5–4 weeks old) and cut into small pieces. The minced tissues were incubated in PBS supplemented with 1% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4 °C for 1 h and then at room temperature for another hour. Trypsin digestion was terminated by the addition of DMEM containing 10% FBS. The mixture was passed in and out through a pipette 30 times and passed through a 70-μm fluorocarbon mesh filter (Millipore). The filtrate was centrifuged at 1000×g for 5 min and then washed with PBS three times. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in complete culture medium (DMEM/Ham’s F-12 culture medium containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin). The isolated endometrial cells were plated and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 48 h of culture, the EECs were stained for immunofluorescence cytochemistry to determine their purity.

Oxygen and glucose deprivation/reoxygenation procedure

OGD/R procedure was performed as previously described [22], with some modifications. In brief, when the adherent EECs grew to 70–80% confluence, the complete medium (DMEM containing 10% FBS) was removed and cells were washed twice and incubated in pre-warmed glucose-free DMEM containing 10% FBS. Then, the cultures were bubbled with an anaerobic gas mix (95% N2, 5% CO2, oxygen deprivation) and maintained under OGD for 2 h, and then returned back to the complete medium and reoxygenated.

Treatment with exosomes

After OGD, the glucose-free solution was replaced with the complete culture medium. The adherent cells were then cultured with 1, 5, 10, and 15 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes or PBS as a vehicle control.

Cell viability assay

The EECs were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL in 100 μL complete culture medium for 16 h before OGD. After OGD, the cells were cultured with exosomes for 24 h. At the end of the 24-h culture period, cell viability was measured using a MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) assay kit (Promega) following the manufacturer’s protocols. In brief, 20 μL MTS was added to the cultured cells in each well and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The absorbance at 490 nm of each well was then detected by a multi well plate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad). Absorbance of cellular MTS metabolism at 490 nm reflected cellular viability.

Lactate dehydrogenase assay

The EECs were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL in 100 μL complete culture medium for 16 h before OGD. After OGD, the cells were cultured with exosomes. Cell necrosis was detected by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. After treatment, the content of LDH in the culture medium was analyzed using a CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Promega). The absorbance at 490 nm was then detected by multi well plate spectrophotometry (Bio-Rad). The percentage of released LDH was calculated by the following formula: LDH released in conditional medium / (LDH released in conditional medium + LDH in cell lysates) × 100%.

Transmission electron microscopy

The exosomes were diluted to the appropriate concentration in PBS and placed on a 200-mesh copper electron microscopy grid. Excess exosome solution on the grid was removed by contacting the grid edge with filter paper. Phosphotungstic acid solution (3%) was then loaded on the sample, and the sample was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. After removing the excess staining solution with filter paper, the sample was dried for 2 min under incandescent light. The grid was placed under a JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (JEOL) and observed and photographed at 80 kV.

Immunofluorescence assay

The EECs were cultured in 24-well slide chambers for 48 h. The EECs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. After blocking with 5% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, the cells were incubated with rabbit anti-vimentin antibody (1:500, ab92547, Abcam) and rabbit anti-cytokeratin antibody (1:500, ab9377, Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, the cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or cyanine dye 3–conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:200, ab6717 and ab6939, Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. The nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min. The fluorescent signals were examined under a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Nikon).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The levels of IL-6 and IL-1β released from cultured EECs into the surrounding medium were measured by ELISA. Cultured media were centrifuged at 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min. IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations in the supernatant were then determined using a commercially available ELISA kit (Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The assay range of the ELISA kit was from 3.75 to 120 pg/mL. The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV, %) was set at < 10%, and the inter-assay CV (%) was set at < 15%. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Western blot analysis

To detect the exosomal marker proteins, exosomes isolated from culture medium were lysed in RIPA buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co. Ltd.). Protein determination was performed using BCA (Nanjing Keygen Biotech Co. Ltd.). Protein sample (20 μg) was denatured in 5× SDS–PAGE sample buffer and subjected to SDS–PAGE gels. The separated proteins were electro-transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore; Bedford, MA) followed by blocking with 10% non-fat milk (w/v) in TBST (Tris-buffered saline pH = 7.4 and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated in antiCD63 antibody (1:1000, ab134045, Abcam) and antiCD9 antibody (1:1000, ab92726, Abcam) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibody (1:1000, ab7090, Abcam). The HRP-tagged bands were visualized using a BeyoECL Plus kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and the chemiluminescence intensity of each band was quantified by Quantity One software.

To detect the protein levels in EECs, the whole-cell extracts from EECs in 24-well culture plates were prepared using RIPA buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co. Ltd.). anti-TLR4 (1:1000, 14358, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-RelA (p65) (1:1000, 8242, Cell Signaling Technology) primary antibodies were used. Western blot was performed as described above.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

EECs cultured in 24-well culture plates were used for total RNA isolation using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), and EEC cDNA synthesis was performed using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was performed using the LightCycler®96 System (Roche Life Science). Three pairs of primer for each detected gene were designed and synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co. Ltd. The specificity of the primers was validated by real-time PCR followed by melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. The validated primer sequences used to detect Il6, Il1b, Tnfa, Tlr4, and Rela are shown in Table 1. Experiments were conducted in triplicate for each data point. The mRNA expression levels were quantified using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Amplification of GAPDH mRNA was used to normalize the data.

Table 1.

The primers for qPCR

| Target gene | GenBank accession no. | Primer sequence | Product size (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gapdh | XM_005680968.1 |

F: 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′ R: 5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3′ |

123 | 60 |

| Il6 | NM_001314054.1 |

F: 5′-CTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCAG-3′ R: 5′-AGTGGTATAGACAGGTCTGTTGG-3′ |

131 | 60 |

| Il1b | NM_008361.4 |

F: 5′-TGAATGCCATTTTGACA-3′ R: 5′-TAGCTGCCACAGCTTCTCC-3′ |

185 | 60 |

| Tnfa | NM_001278601.1 |

F: 5′-GGCAGGTCTACTTTGGAGTCAT-3′ R: 5′-CAGAGTAAAGGGGTCAGAGTGG-3′ |

89 | 60 |

| Rela | NM_009045 |

F: 5′-AGGCTTCTGGGCCTTATGTG-3′ R: 5′-TGCTTCTCTCGCCAGGAATAC-3′ |

111 | 60 |

| Tlr4 | XM_021161091.1 |

F: 5′-TAGCCATTGCTGCCAACATCAT-3′ R: 5′-AAGATACACCAACGGCTCTGAA-3′ |

100 | 60 |

Statistical analysis

All experiments were replicated at least three times for each group, and the data were expressed as mean ± SD. The data were analyzed using ANOVA, which was followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (Fisher LSD) test with SPSS software (version 22; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Exosomes from hucMSCs

After ultracentrifugation, the pellets from the culture medium of hucMSC were identified by transmission electron microscopy. It showed the spheroid morphology of pellets derived from hucMSCs and confirmed their sizes to be between 40 and 100 nm (Fig. 1a). Western blot assay indicated that the exosomal marker proteins CD63 and CD9 were highly expressed in the ultracentrifugation pellet but barely expressed in the cell culture medium (Fig. 1b). These results indicate that exosomes were successfully isolated with this ultracentrifugation protocol.

Fig. 1.

The validation of hucMSC-secreted exosomes and purified mouse endometrial epithelial cells. a Transmission electron microscopic image of ultracentrifugation pellet from the culture medium of hucMSCs. Arrows indicate the representative exosomes; scale bar represents 200 nm. b Immunoblotting of the ultracentrifugation pellet and culture medium for exosomal surface proteins CD63 and CD9

hucMSC-derived exosomes improve the cell viability and inhibit cell death of injured EECs undergoing OGD/R

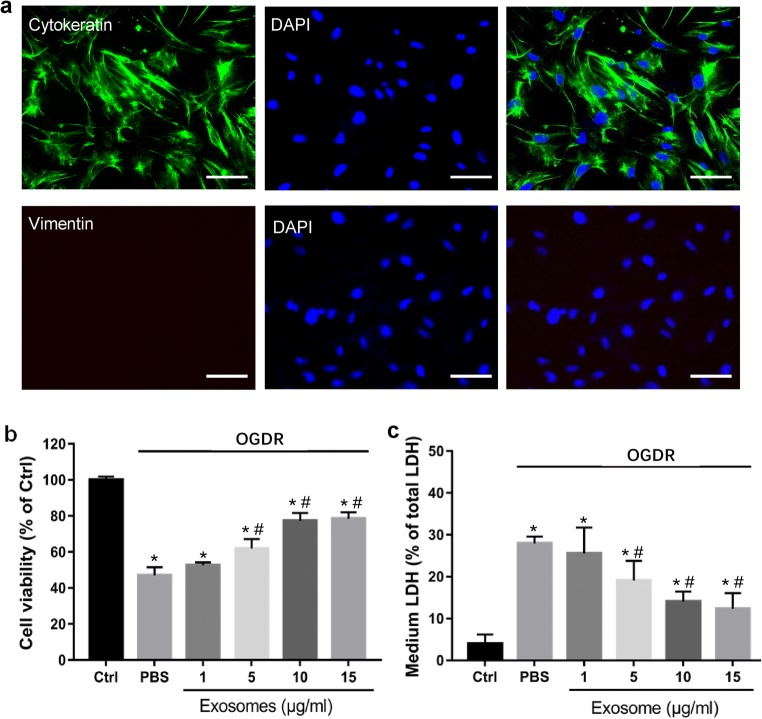

To investigate the potential effect of stem cell–derived exosomes on injured endometrial cells, primary endometrial epithelial cells were separated and purified. Immunofluorescence staining analysis revealed that the purity of the EECs was greater than 90% (Fig. 2a). Compared with the control group, exposure of EECs with OGD/R induced potent cell viability reduction (47.01% as shown in the PBS group, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2b). LDH assay showed that OGD/R significantly increased LDH release of EECs (27.99% as shown in the PBS group, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2c), which means notable cell death. Remarkably, such effects induced by OGD/R were largely attenuated with co-treatment of hucMSC-derived exosomes. At dose of 5–15 μg/mL, hucMSC-derived exosomes significantly improved cell viability (61.98, 77.30, and 78.57%, respectively, P < 0.01 vs PBS group) and significantly inhibited LDH release (19.09, 14.05, and 12.35%, respectively, P < 0.01 vs PBS group) (Fig. 2b and c). At a low concentration (1 μg/mL), hucMSC-derived exosomes were ineffective (Fig. 2a and b). Together, these results suggest that hucMSC-derived exosomes repair injured EECs.

Fig. 2.

Effects of hucMSC-derived exosomes on primary culture of endometrial cells undergoing OGD/R. a Immunocytochemical staining analysis of vimentin in purified ESCs. Cytokeratin is stained green; vimentin is stained red; nuclei are stained blue with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI); and scale bar represents 200 μm. Cell viability was examined by MTS assay (b), and cell death was examined by LDH release (c). “OGD/R” stands for oxygen and glucose deprivation/reoxygenation. “Ctrl” stands for EECs without treatment of OGDR or exosomes. “PBS” stands for cells treated with PBS. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05 vs. Ctrl. #p < 0.05 vs PBS

hucMSC-derived exosomes reduce the OGD/R-induced production of proinflammatory cytokines in EECs

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the protective effect of hucMSC-derived exosomes, we examined the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. In view of the cell viability and LDH release, a dose of 10 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes is comparable with that observed in the 15 μg/mL group (P > 0.05, Fig. 2b and c); therefore, we chose 10 μg/mL as the treatment dose of hucMSC-derived exosomes. As presented in Fig. 3a–c, real-time PCR analysis revealed that the mRNA levels in EECs of Il1b, Il6, and Tnfa in EECs were significantly upregulated after OGD/R for 24 h (PBS vs control, P < 0.05). Remarkably, their mRNA expression was largely decreased when co-treated with hucMSC-derived exosomes at 10 μg/mL (P < 0.05 vs PBS group). To further confirm the anti-inflammatory effect, the protein levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFA were measured in the culture supernatants. As shown in Fig. 3d–f, OGD/R increased the release of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFA into the extracellular space (P < 0.05 vs control), whereas hucMSC-derived exosomes efficiently inhibited their release (P < 0.05 vs PBS group). Furthermore, we examined whether exosome treatment could modulate the TLR4/RelA pathway in OGD/R-induced injured EECs. The results of the Western blot results revealed that 10 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes significantly reduced the OGD/R-induced increase in protein expression of TLR4 and RelA(p65) in EECs (Fig. 4c, d). Real-time PCR analysis revealed that the mRNA expression of Tlr4 and Rela was significantly reduced in EECs with hucMSC-derived exosomes treatment (Fig. 4a, b). These results suggest that modulation of TLR4, RelA(p65), and proinflammatory cytokines may be involved in the protection effect of hucMSC-derived exosomes on OGD/R-induced injured EECs.

Fig. 3.

hucMSC-derived exosomes have the anti-inflammatory effect against OGD/R in EECs. a–c The mRNA expression of Il1b, Il6, and Tnfa was examined by real-time PCR. d, e The protein expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFA was examined by ELISA. “OGD/R” stands for oxygen and glucose deprivation/reoxygenation. “Ctrl” stands for EECs without treatment of OGDR or exosomes. “PBS” stands for cells treated with PBS. “Exosomes” stands for cells treated with 10 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 4). *p < 0.05 vs. Ctrl. #p < 0.05 vs PBS

Fig. 4.

hucMSC-derived exosomes modulate TLR4 and RelA(p65) expression in OGD/R-induced injured ESCs. a, b The mRNA expression of Tlr4 and Rela was examined by real-time PCR. c, d The protein expression of TLR4 and RelA(p65) was examined by Western blot. “Ctrl” stands for EECs without treatment of OGDR or exosomes. “PBS” stands for cells treated with PBS. “Exosomes” stands for cells treated with 10 μg/mL of hucMSC-derived exosomes. Data were shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05 vs. Ctrl. #p < 0.05 vs PBS

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that exosomes released by hucMSCs could promote the function of injured mouse EECs. Normal uterine bleeding is the base of a normal uterine environment. It is widely accepted that reduced blood flow is one of the causes of thin endometrium. Some endometrial diseases, such as endometrial adhesions and uterine congenital abnormalities, can result in abnormal uterine bleeding, leading to ischemic damages of the endometrial cells. Thus, we used the OGD/R model to mimic the endometrial cell injury. We found that hucMSC-derived exosomes could prevent the OGD/R-induced cell viability decrease and LDH release. Furthermore, hucMSC-derived exosomes inhibited the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the anti-inflammatory signaling pathway.

It is well known that MSCs are an attractive cell source as novel therapeutic agents to treat various diseases. Initially, MSCs were thought to exert their effects by their multipotent differentiation capacity and direct intercellular interactions. However, emerging studies have indicated that MSCs mediate their therapeutic functions in a paracrine manner, rather than in a cellular manner. Recent studies have reported that extracellular vesicles (EVs), especially exosomes, are the therapeutically active components, which promote comparable therapeutic activities as MSCs themselves. Since the first description of the therapeutic potential of exosomes secreted by MSC in a mouse myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury model [23], many studies have been published addressing the therapeutic functions of MSC-EVs in several animal models and cell types. Ma et al. have reported that hucMSC-derived EVs can successfully improve nerve regeneration in a rat model of sciatic nerve transection [24]. Zhang et al. have reported that hucMSC-derived EVs promote cell proliferation and re-epithelialization in a rat burn injury model [25]. Sun et al. showed that hucMSC-derived exosomes protect against cisplatin-induced apoptosis of rat ovarian granulosa cells [26]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to test their potential activity in injured endometrial epithelial cells.

Exosomes are lipid bilayer–enclosed membrane vesicles that are released from cells into the extracellular space. The sizes of exosomes are from 50 to 100 nm in diameter. These nanoscale vesicles can serve as mediators for cell-to-cell communication through delivery of cargo, including mRNAs, microRNAs, and different kinds of proteins and transmembrane proteins, including enzymes, growth factors, cytokines, annexin, and intracellular cell adhesion molecules [27]. Proteomic analysis revealed that MSC-derived exosomes contain more than 1900 proteins [28]. Deep-sequencing analysis revealed that the small RNA profile of MSC-derived exosomes selectively incorporates specific miRNAs which regulate cell cycle progression, proliferation, and angiogenesis [29]. Arslan et al. demonstrated that MSC-derived exosomes enhance myocardial viability by increasing ATP levels and decreasing oxidative stress [30]. Zhou et al. showed that hucMSC-derived exosomes protect renal tubular epithelial cells from cisplatin-induced injury by decreasing oxidative stress and apoptosis [31]. MSC-derived exosomes promote myogenesis and angiogenesis of C2C12 myoblast cells, probably partly via miRNAs [32]. hucMSC-derived exosomes attenuate burn-induced inflammation in rats by decreasing TNF-α and IL-1β levels via the TLR4 signaling pathway [33]. In the present study, hucMSC-derived exosomes decreased the expression of TLR4, RelA, IL-1β, and IL-6 in OGD/R-induced injured EECs, suggesting that one of the mechanisms of the protective effect of hucMSC-derived exosomes against OGD/R-induced injury could be related to anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of the TLR4/RelA signaling pathway. We suggest that these benefits of hucMSC-derived exosomes may be exerted through the horizontal transfer of proteins, mRNAs, and regulatory microRNAs.

Our study, however, has some limitations. The OGD/R-induced injured EECs could not accurately represent the endometrial damages in vivo. In addition, the underlying mechanism of the repair effect of the hucMSC-derived exosomes should be further investigated.

In conclusion, hucMSC-derived exosomes efficiently enhance the viability of injured EECs and reduce their death, and exhibit an anti-inflammatory effect against OGD/R. Despite stem cell therapy becoming a promising method for repairing damaged endometria, there are some limitations of this novel therapy, such as ethical constraints, collection procedures, immunogenicity, and oncogenicity. Exosomes can be easily isolated from MSCs and carry biologically active molecules. Our results imply that hucMSC-derived exosomes may be a novel cell-free therapeutic strategy to promote endometrial function.

Funding information

This research was financially supported by the Key Science and Technology Program of Henan Province (182102310129) and Clinical Medicine Special Funds for Scientific Research Projects of Chinese Medical Association (18010320761).

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Experiments of Zhengzhou University, China.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Linlin Liang and Lu Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Chenchen Cui, Email: ccc_sry@163.com.

Cuilian Zhang, Email: luckyzcl@qq.com.

References

- 1.Kasius A, Smit JG, Torrance HL, Eijkemans MJ, Mol BW, Opmeer BC, Broekmans FJ. Endometrial thickness and pregnancy rates after IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(4):530–541. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao J, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Li Y. Endometrial pattern, thickness and growth in predicting pregnancy outcome following 3319 IVF cycle. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;29(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan X, Saravelos SH, Wang Q, Xu Y, Li TC, Zhou C. Endometrial thickness as a predictor of pregnancy outcomes in 10787 fresh IVF-ICSI cycles. Reprod BioMed Online. 2016;33(2):197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rein DT, Schmidt T, Hess AP, Volkmer A, Schondorf T, Breidenbach M. Hysteroscopic management of residual trophoblastic tissue is superior to ultrasound-guided curettage. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(6):774–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nastri CO, Lensen SF, Gibreel A, Raine-Fenning N, Ferriani RA, Bhattacharya S, et al. Endometrial injury in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD009517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009517.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Achilli C, Duran-Retamal M, Saab W, Serhal P, Seshadri S. The role of immunotherapy in in vitro fertilization and recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(6):1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong KH, Forman EJ, Werner MD, Upham KM, Gumeny CL, Winslow AD, Kim TJ, Scott RT Jr Endometrial infusion of human chorionic gonadotropin at the time of blastocyst embryo transfer does not impact clinical outcomes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(6):1591–5.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wirleitner B, Schuff M, Vanderzwalmen P, Stecher A, Okhowat J, Hradecký L, Kohoutek T, Králícková M, Spitzer D, Zech NH. Intrauterine administration of human chorionic gonadotropin does not improve pregnancy and life birth rates independently of blastocyst quality: a randomised prospective study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0069-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barad DH, Yu Y, Kushnir VA, Shohat-Tal A, Lazzaroni E, Lee HJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of endometrial perfusion with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in in vitro fertilization cycles: impact on endometrial thickness and clinical pregnancy rates. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lensen S, Osavlyuk D, Armstrong S, Stadelmann C, Hennes A, Napier E, et al. A randomized trial of endometrial scratching before in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):325–334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cervelló I, Santamaria X, Pellicer A, Remohí J, Simón C, Ferro J, et al. Autologous cell therapy with CD133+ bone marrow-derived stem cells for refractory Asherman’s syndrome and endometrial atrophy: a pilot cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):1087–1096. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao D, Kong L, Li P, Li X, Xu X, Li Y, et al. Autologous menstrual blood-derived stromal cells transplantation for severe Asherman’s syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2723–2729. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao Y, Sun H, Zhu H, Zhu X, Tang X, Yan G, Wang J, Bai D, Wang J, Wang L, Zhou Q, Wang H, Dai C, Ding L, Xu B, Zhou Y, Hao J, Dai J, Hu Y. Allogeneic cell therapy using umbilical cord MSCs on collagen scaffolds for patients with recurrent uterine adhesion: a phase I clinical trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):192. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0904-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JH, Hwang I, Hwang SH, Han H, Ha H. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent diabetic renal injury through paracrine action. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98(3):465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, Melo LG, Morello F, Mu H, Noiseux N, Zhang L, Pratt RE, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2005;11(4):367–368. doi: 10.1038/nm0405-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goolaerts A, Pellan-Randrianarison N, Larghero J, Vanneaux V, Uzunhan Y, Gille T, Dard N, Planès C, Matthay MA, Clerici C. Conditioned media from mesenchymal stromal cells restore sodium transport and preserve epithelial permeability in an in vitro model of acute alveolar injury. Am J Phys Lung Cell Mol Phys. 2014;306(11):L975–L985. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00242.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phinney DG, Pittenger MF. Concise review: MSC-derived exosomes for cell-free therapy. Stem cells Dayt Ohio. 2017;35(4):851–858. doi: 10.1002/stem.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang S, Chuah SJ, Lai RC, Hui JHP, Lim SK, Toh WS. MSC exosomes mediate cartilage repair by enhancing proliferation, attenuating apoptosis and modulating immune reactivity. Biomaterials. 2018;156:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomi G, Surbek D, Haesler V, Joerger-Messerli M, Schoeberlein A. Exosomes derived from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells reduce microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in perinatal brain injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1207-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lobb RJ, Becker M, Wen Wen S, Wong CSF, Wiegmans AP, Leimgruber A, et al. Optimized exosome isolation protocol for cell culture supernatant and human plasma. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4(1):27031. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormack SA, Glasser SR. Differential response of individual uterine cell types from immature rats treated with estradiol. Endocrinology. 1980;106(5):1634–1649. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-5-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi X, Liu HY, Li SP, Xu HB. Keratinocyte growth factor protects endometrial cells from oxygen glucose deprivation/re-oxygenation via activating Nrf2 signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;501(1):178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai Ruenn Chai, Arslan Fatih, Lee May May, Sze Newman Siu Kwan, Choo Andre, Chen Tian Sheng, Salto-Tellez Manuel, Timmers Leo, Lee Chuen Neng, El Oakley Reida Menshawe, Pasterkamp Gerard, de Kleijn Dominique P.V., Lim Sai Kiang. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Research. 2010;4(3):214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Y, Dong L, Zhou D, Li L, Zhang W, Zhen Y, Wang T, Su J, Chen D, Mao C, Wang X. Extracellular vesicles from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells improve nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve transection in rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(4):2822–2835. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang B, Wang M, Gong A, Zhang X, Wu X, Zhu Y, Shi H, Wu L, Zhu W, Qian H, Xu W. HucMSC-exosome mediated-Wnt4 signaling is required for cutaneous wound healing. Stem Cells. 2015;33(7):2158–2168. doi: 10.1002/stem.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun L, Li D, Song K, Wei J, Yao S, Li Z, Su X, Ju X, Chao L, Deng X, Kong B, Li L. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect against cisplatin-induced ovarian granulosa cell stress and apoptosis in vitro. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):2552. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02786-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hessvik NP, Llorente A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(2):193–208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson JD, Johansson HJ, Graham CS, Vesterlund M, Pham MT, Bramlett CS, Montgomery EN, Mellema MS, Bardini RL, Contreras Z, Hoon M, Bauer G, Fink KD, Fury B, Hendrix KJ, Chedin F, el-Andaloussi S, Hwang B, Mulligan MS, Lehtiö J, Nolta JA. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of mesenchymal stem cell exosomes reveals modulation of angiogenesis via nuclear factor-kappa B signaling. Stem Cells. 2016;34(3):601–613. doi: 10.1002/stem.2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baglio SR, Rooijers K, Koppers-Lalic D, Verweij FJ, Pérez Lanzón M, Zini N, Naaijkens B, Perut F, Niessen HW, Baldini N, Pegtel DM. Human bone marrow- and adipose-mesenchymal stem cells secrete exosomes enriched in distinctive miRNA and tRNA species. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0116-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arslan F, Lai RC, Smeets MB, Akeroyd L, Choo A, Aguor ENE, Timmers L, van Rijen H, Doevendans PA, Pasterkamp G, Lim SK, de Kleijn DP. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes increase ATP levels, decrease oxidative stress and activate PI3K/Akt pathway to enhance myocardial viability and prevent adverse remodeling after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2013;10(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Y, Xu H, Xu W, Wang B, Wu H, Tao Y, Zhang B, Wang M, Mao F, Yan Y, Gao S, Gu H, Zhu W, Qian H. Exosomes released by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect against cisplatin-induced renal oxidative stress and apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4(2):34. doi: 10.1186/scrt194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura Y, Miyaki S, Ishitobi H, Matsuyama S, Nakasa T, Kamei N, Akimoto T, Higashi Y, Ochi M. Mesenchymal-stem-cell-derived exosomes accelerate skeletal muscle regeneration. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(11):1257–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Liu L, Yang J, Yu Y, Chai J, Wang L, Ma L, Yin H. Exosome derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell mediates MiR-181c attenuating burn-induced excessive inflammation. EBioMedicine. 2016;8:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]