Abstract

Purpose

To determine the prevalence of allergy in couples undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) and the relationship between having allergy and IVF treatment outcomes.

Design

A retrospective cohort study of female infertility patients aged 20–49 years and their male partners undergoing IVF cycles from August 2010 to December 2016 in an academic fertility program.

Results

Prevalence data was collected for 493 couples (935 cycles). Over half of the female patients (54%) had at least one reported allergy versus the cited US prevalence of 10–30%. Antibiotic (54.7%) and non-antibiotic medication (39.2%) were the most common female allergy subtypes. Fewer male patients reported allergy (21.7%). Data on β-hCG outcomes were calculated for 841 cycles from 458 couples with no significant relationship found except for number of cycles including ICSI and number of embryos transferred per cycle (1.81 for those without allergy vs 2.07 for those with allergy, p = 0.07). Female patients with allergy were marginally statistically more likely to have a negative β-hCG (p = 0.07) and less likely to have a successful cycle (p = 0.06). When allergy subgroups were evaluated, there were no significant differences between groups except for a higher number of embryos transferred in women with environmental/other allergies (p = 0.02).

Conclusion

The prevalence of allergy among patients seeking infertility treatment is high compared with the general population. However, allergy was not found to be associated with IVF cycle outcomes. These findings are likely primarily limited by difficulty in defining specific allergy types within a retrospective study.

Keywords: Allergy, Infertility, IVF, Pregnancy outcome

Introduction

The success of an early pregnancy involves a complex interaction of multiple lines of immune cells; abnormalities in this system are implicated in poor reproductive outcomes [1, 2]. Regulatory T cells are thought to be important in protecting the embryo from immune rejection and women with unexplained infertility have been found to have lower levels of endometrial regulatory T cell transcription factors than fertile controls [3, 4]. Women with recurrent pregnancy loss have also been found to have higher levels of Th1 cytokines and lower levels of Th2 cytokines than fertile women and decreased levels of regulatory T cells are seen in products of conception from spontaneous abortions compared to those from elective terminations [5, 6]. Both of these findings suggest that altered T cell responses may be involved in the pathogenesis of miscarriage. Macrophages and dendritic cells also appear to play an important role in reproductive function, and mouse models depleted of these cells have shown evidence of impaired implantation [7–9]. Lower levels of dendritic cells have also been found in samples from spontaneous abortions compared with normally developing pregnancies in mice, implying they may also be important in preventing spontaneous pregnancy loss [10]. Lastly, both mast cells and natural killer cells have been shown to be important in the success of early pregnancy and release of abnormal cytokine profiles by helper T cells, natural killer cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells have been seen in women with reproductive failure [6, 11–15].

While well established that inflammatory disorders can lead to male genital tract obstruction, gamete destruction, and production of abnormal gametes, little is known regarding the role of immune cells and inflammatory mediators in specific disease processes related to male infertility. In the studies that do exist, high levels of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α are found in the seminal fluid of infertile men with varicoceles and upregulation of reactive oxygen species is seen in cryptorchid males suggesting that immune responses may play a role in the subfertility associated with these conditions [16].

Dysfunction of many of the same cells and inflammatory mediators are involved in the pathogenesis of allergy [17–22]. However, there have been limited studies investigating how allergy may be related to infertility and those that have been performed have yielded inconsistent results. In 1989, a small exploratory study demonstrated that males in couples with unexplained infertility had higher serum IgE levels than fertile controls, but did not find the same result for female subjects [23]. In 2006, a separate study demonstrated an increased prevalence of infertility in women with a history of allergies [24]. Some studies have investigated the association of allergy with specific infertility diagnoses and have found high prevalence of allergy in women with endometriosis and ovulatory dysfunction [25–27]. Other studies, however, have not found such an association [28, 29]. To date, the only study that has explored how allergy may be related to fertility treatment outcomes was a small retrospective analysis of women undergoing in vitro fertilization with fresh embryo transfer (IVF-ET) at a single center between 1996 and 2002 in which no significant difference in clinical pregnancy rate was found between women with and without reported allergies [30]. Thus, the objective of this study was to, firstly, determine the prevalence of allergy in both the male and female patients undergoing IVF treatment at our academic fertility clinic and, secondly, to investigate the relationship between the presence of any patient allergy or allergy subtype with IVF pregnancy outcomes.

Materials and methods

Cohort selection

All infertility patients aged 20–49 years and their male partners who underwent IVF-ET or frozen embryo transfer (FET) from August 2010 to December 2016 at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center (USA) were included in this retrospective cohort study. Institutional review board approval was obtained to access patient charts and embryology data and it was determined that no consent was needed. Baseline demographic characteristics, infertility diagnoses, semen parameters, pregnancy and cycle outcomes, and the presence and types of allergy in male and female participants were collected primarily from the electronic medical record with some data also obtained from a questionnaire filled out by female patients at the time of their infertility evaluation.

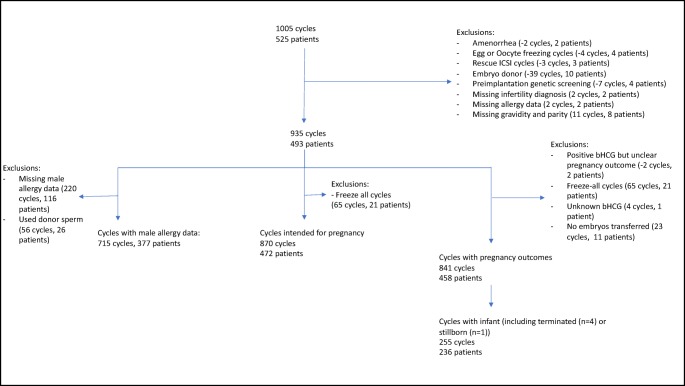

Figure 1 provides details for cohort selection. The original dataset contained 1005 cycles from 525 patients. Two cycles (two patients) were removed for amenorrhea, four cycles (four patients) were removed due to the intention of oocyte freezing, and three cycles (three patients) for needing rescue intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Cycles using donor egg or donor embryo were excluded (10 patients, 39 cycles), as were cycles that utilized preimplantation genetic screening (four patients, 7 cycles). Two patients were missing infertility diagnosis (two cycles), and two were missing allergy data (two cycles) and were excluded. Finally, eight patients were excluded due to missing gravidity and parity data (11 cycles), as these data were needed for inclusion in the statistical models. After these exclusions, a cohort consisting of 935 cycles and 493 patients was used to determine the prevalence of allergy within our population and generate demographic characteristics, as well as analysis of cycle outcomes prior to the embryo transfer (number of oocytes retrieved, number of mature oocytes (MIIs), fertilization rate, abnormal fertilization rate (1PN and 3PN), and average number of embryos frozen) after exclusion of those with missing values for the variable of interest.

Fig. 1.

Cohort selection

To explore association of allergy and IVF pregnancy outcomes, a cohort of cycles intended for immediate pregnancy was selected. Two patients and cycles were excluded due to a positive β-hCG test but unclear pregnancy outcomes; 65 freeze-all cycles (21 patients) were excluded as the cycle was not intended for immediate pregnancy; 4 cycles (1 patient) were excluded due to unknown β-hCG outcomes; and 23 cycles from 11 patients were excluded due to cycle resulting in no embryos for transfer, leaving a cohort of 841 cycles from 458 patients. Analyses for other cycle outcomes were performed on the entire cohort excluding freeze-all cycles (65 cycles, 21 patients) for a cohort of 870 cycles (472 patients).

Relationship between allergy and IVF cycle outcomes

All data analyses were completed using R 3.4.2. An alpha of 0.05 was used for all analyses. Demographics and descriptive data were generated using the tableone package (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tableone). Mixed effects models, a form of regression analysis, using the lme4 package were used to identify the relationship between patient allergy and IVF outcomes (including negative β-HCG, biochemical pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, and successful cycles, i.e., cycles resulting in either live birth, pregnancy termination (n = 4), or stillbirth (n = 1), as well as embryology data to include number of oocytes retrieved, number of MII embryos, fertilization rate, abnormal fertilization rate, average number of embryos transferred, and average number of embryos frozen, and endometrial thickness). Data for allergy prevalence as well as demographic and clinical characteristics was analyzed by patient. Data for IVF outcomes was analyzed by cycle as 26% of cycles were missing the complete cycle history for that patient as one or more of the patient’s cycles either occurred outside of the study period or at another fertility center. The mixed effect model allowed us to account for the repeated measures in the dataset (i.e., multiple and differing number of cycles for some patients resulting in a lack of independence between cycles) while also adjusting for confounders.

Outcomes evaluated included β-hCG result (negative, biochemical pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, and positive/successful cycle), cycle outcomes (mean endometrial thickness, mean number of oocytes retrieved per cycle, mean number of mature oocytes per cycle, mean fertilization rate per cycle, mean number of abnormal fertilized oocytes per cycle, mean number of embryos transferred per cycle, and mean number of embryos frozen per cycle). All models were performed with the patient ID as the random effect and maternal age, categorical BMI at the time of cycle initiation, maternal race (white or non-white given low numbers of non-white subjects), maternal parity and gravidity, maternal smoking history, and the type of procedure (IVF, ICSI, IVF+ICSI, or FET) as fixed effects, allowing for adjustment for these confounders. Year in which the cycle took place was included as a fixed effect in the model for β-HCG outcomes and number of embryos transferred was included as a fixed effect in the model for β-HCG outcomes, including the sub-analyses of these variables. For those outcomes with marginal statistical significance (p ≤ 0.08), additional analyses were performed by allergy subtype (antibiotic, non-antibiotic prescription medication, and environmental, which included pollen/dust, food, latex, and other allergies, which included food, pollen/dust, latex, animal dander, insect venom, adhesive, contrast, and iodine) using mixed effects models with the same fixed effects. Semen analysis outcomes included semen volume, count, motility, and number of total motile sperm. Evaluation of the relationship between male allergy and semen characteristics (mean semen volume, mean sperm count, mean sperm motility, and mean total motile sperm) was performed with male race and presence of female allergy as a fixed effects and patient ID as the random effect. Differences in ratio of female and male infants based on female and male allergy and differences in allergy status based on infertility diagnosis were evaluated using Fisher’s exact tests. Difference in birthweight between infants born to those with and without female allergy was compared using Student’s t test.

Results

Cohort demographics and cycle characteristics

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire cohort by patient. For demographics for which multiple measurements were available for an individual participant, data from the participant’s first cycle was used. The majority of male and female patients were Caucasian and non-smokers. Mean female patient age was 34.8 years (SD 4.6) and average female patient BMI was 26.82 (SD 5.8). Over three-quarters of female patients had primary infertility with most common female infertility diagnoses being unexplained, structural (including all tubal and uterine causes), and diminished ovarian reserve. Approximately one-tenth of couples (9.5%) had both male and female infertility diagnoses. The most common causes of male infertility were unexplained, and abnormal semen parameters (oligospermia and asthenospermia). Table 2 demonstrates the general characteristics of all cycles during the collection period. Cycles were largely evenly distributed between data collection years except for 2010 as data collection did not begin until August. Cycles were also largely evenly distributed between IVF with ET, ICSI with ET, and FET. However, a small number of cycles were split, with some eggs undergoing standard insemination and others undergoing ICSI. As this group compromised only 3% of all cycles, they were not included in further discussion of results. Just under half of all cycles resulted in a negative β-hCG and approximately one-third of cycles were successful, i.e., resulting in live birth, stillbirth, or pregnancy termination.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics for entire cohort (by patient) n = 493 and by presence of female allergy, except for male infertility diagnosis, which is by male allergy (excluding 116 couples with missing male allergy data)

| Patient characteristic | All patients (n (%)) | No allergy (n = 228) | Allergy (n = 265) | p values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female race | White | 447 (90.7) | 198 (86.8) | 249 (94.0) | 0.04 |

| Asian | 26 (5.3) | 18 (7.9) | 8 (3.0) | ||

| African American | 7 (1.4) | 2 (0.9) | 5 (1.9) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Multi-racial | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Unknown/declined to list | 8 (1.6) | 7 (3.1) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Male race | White | 423 (89.1) | 195 (88.2) | 228 (89.8) | 0.25 |

| Asian | 18 (3.8) | 12 (5.4) | 6 (2.4) | ||

| African American | 7 (1.5) | 2 (0.9) | 5 (2.0) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Multi-racial | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Unknown/declined to list | 26 (5.5) | 11 (5.0) | 15 (5.9) | ||

| Female BMI | Normal | 227 (46.0) | 108 (47.4) | 119 (44.9) | 0.15 |

| Overweight | 125 (25.4) | 25 (11.0) | 42 (15.8) | ||

| Obese I | 67 (13.6) | 20 (8.8) | 27 (10.2) | ||

| Obese II | 47 (9.5) | 3 (1.3) | 7 (2.6) | ||

| Obese III | 10 (2.0) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (1.1) | ||

| Underweight | 6 (1.2) | 9 (3.9) | 2 (0.8) | ||

| Female smoking history | Current | 23 (4.7) | 12 (5.3) | 11 (4.2) | 0.22 |

| Former | 68 (13.8) | 26 (11.4) | 42 (15.8) | ||

| Never | 397 (80.5) | 186 (81.6) | 211 (79.6) | ||

| Missing/not assessed | 5 (1.0) | 4 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Male smoking history | Current | 43 (8.7) | 20 (8.8) | 23 (8.7) | 1.00 |

| Former | 67 (13.6) | 31 (13.6) | 36 (13.6) | ||

| Never | 256 (51.9) | 118 (51.8) | 138 (52.1) | ||

| Missing/not assessed | 127 (25.8) | 59 (25.9) | 68 (25.7) | ||

| Parity | 0 | 377 (76.5) | 185 (81.1) | 192 (72.5) | 0.03 |

| 1 | 85 (17.2) | 28 (12.3) | 57 (21.5) | ||

| 2 | 24 (4.9) | 11 (4.8) | 13 (4.9) | ||

| 3 | 5 (1.0 | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) | ||

| 4 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| ≥ 5 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Female infertility diagnosis (non-exclusive)a | Unexplained | 158 (32.0) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 0.71 |

| Structural | 74 (15.0) | 35 (47.3) | 39 (52.7) | 0.90 | |

| Advanced reproductive age | 9 (1.8) | 2 (18.2) | 9 (81.8) | 0.19 | |

| Ovulatory disorder | 22 (4.5) | 13 (59.1) | 9 (40.9) | 0.28 | |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 17 (3.4) | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | 0.08 | |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 45 (9.1) | 22 (48.9) | 23 (51.1) | 0.76 | |

| Endometriosis | 19 (3.9) | 9 (47.4) | 10 (52.6) | 1.00 | |

| Multiple | 7 (1.4) | 78 (49.4) | 80 (50.6) | 0.38 | |

| Other | 20 (4.1) | 9 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) | 1.00 | |

| Male infertility diagnosis (non-exclusive)a | Unexplained | 158 (32.0) | 80 (29.7) | 30 (28.0) | 0.80 |

| Structuralb | 18 (3.7) | 14 (5.3) | 2 (1.9) | 0.25 | |

| Abnormal semen parametersc | 134 (27.2) | 60 (22.3) | 46 (43.0) | < 0.001 | |

| ED/paraplegic | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | -- | |

ap values for differences between allergic and non-allergic groups by infertility diagnosis were calculated using fisher exact tests. Percentages are of total participants with that diagnosis; diagnoses are non-exclusive; comparisons between male allergy and non-allergic groups excluded those missing male allergy status (n = 117)

bStructural causes included varicocele, vasectomy, and unsuccessful vasectomy reversal

cp values not calculated due to small size of those with diagnosis

Table 2.

Cycle characteristics for entire cohort (by cycle, n = 935) and for those with and without female allergy (excluding freeze-all cycles)

| All cycles (n = 935) | No allergy (n = 450) | Allergy (n = 485) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year (N (%)) | 2010 | 58 (6.2) | 30 (6.7) | 28 (5.8) | 0.02 |

| 2011 | 142 (15.2) | 72 (16.0) | 70 (14.4) | ||

| 2012 | 123 (13.2) | 62 (13.8) | 61 (12.6) | ||

| 2013 | 156 (16.7) | 69 (15.3) | 87 (17.9) | ||

| 2014 | 119 (12.7) | 52 (11.6) | 67 (13.8) | ||

| 2015 | 156 (16.7) | 60 (13.3) | 96 (19.8) | ||

| 2016 | 181 (19.4) | 105 (23.3) | 76 (15.7) | ||

| Cycle type (N (%)) | IVF | 357 (38.2) | 152 (33.8) | 122 (25.2) | 0.03 |

| ICSI | 279 (29.8) | 130 (28.9) | 149 (30.7) | ||

| FET | 274 (29.3) | 158 (35.1) | 199 (41.0) | ||

| IVF/ICSI | 25 (2.7) | 10 (2.2) | 15 (3.1) | ||

| Mean endometrial thickness at time of transfer (mm (SD)) |

IVF ICSI |

9.8 (3.1) | 9.65 (3.02) | 10.02 (3.16) | 0.08 |

| Mean # of oocytes retrieved (N (SD)) | IVF | 12.6 (7.5) | 12.35 (8.19) | 12.71 (6.91) | 0.64 |

| ICSI | 12.2 (7.0) | 13.09 (7.36) | 11.45 (6.51) | ||

| Mean # of mature oocytes (N (SD)) | IVF | 10.2 (6.3) | 9.79 (6.38) | 10.47 (6.28) | 0.30 |

| ICSI | 9.3 (5.6) | 9.94 (5.90) | 8.71 (5.16) | 0.05 | |

| Mean fertilization rate (% (SD)) | IVF | 73.6 (24.2) | 0.74 (0.25) | 0.73 (0.23) | 0.59 |

| ICSI | 63.7 (22.9) | 0.63 (0.23) | 0.64 (0.23) | 0.68 | |

| Mean #of cleavage stage embryos (N (SD)) | IVF | 6.5 (4.9) | 6.36 (4.84) | 6.66 (5.02) | 0.56 |

| ICSI | 5.3 (4.1) | 5.57 (4.34) | 5.14 (3.84) | 0.36 | |

| Mean #of blast stage embryos (N (SD)) | IVF | 1.6 (3.1) | 1.89 (3.35) | 1.43 (2.94) | 0.15 |

| ICSI | 1.0 (2.1) | 1.04 (2.15) | 0.99 (2.13) | 0.87 | |

| Mean # of embryos transferred (N (SD)) | -- | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.81 (0.88) | 2.07 (0.99) | 0.07 |

| Mean # of embryos cryopreserved (N (SD)) | -- | 1.9 (3.4) | 1.87 (3.43) | 1.86 (3.39) | 0.96 |

| Mean semen analysis parameters (N (SD)) | Semen volume (mL) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.26 (1.54) | 2.52 (1.34) | 0.27 |

| Sperm count (million/mL) | 74.6 (70.4) | 67.56 (69.61) | 72.15 (64.46) | 0.33 | |

| Sperm motilitya (%) | 51.4 (17.7) | 48.96 (18.15) | 52.92 (18.28) | 0.19 | |

| Total motile sperm (million/ejaculate) | 108.1 (125.3) | 87.97 (99.81) | 111.51 (129.43) | 0.16 | |

| Cycle outcome (N (%)) | Negative β-HCG | 413 (44.2) | 188 (46.2) | 225 (51.1) | 0.56 |

| Biochemical pregnancy | 102 (10.9) | 48 (11.8) | 54 (12.3) | ||

| Ectopic pregnancy | 7 (0.1) | 3 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) | ||

| Spontaneous abortion | 59 (6.3) | 27 (6.6) | 32 (7.3) | ||

| Successful cycle | 262 (28.0) | 139 (34.2) | 123 (28.0) | ||

| Unknown | 4 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| NA (no embryos transferred or freeze-all) | 88 (9.4) | - | - |

aSperm motility includes both progressive and non-progressive motility and was calculated as the percent of motile sperm

Prevalence of allergy in infertile couples

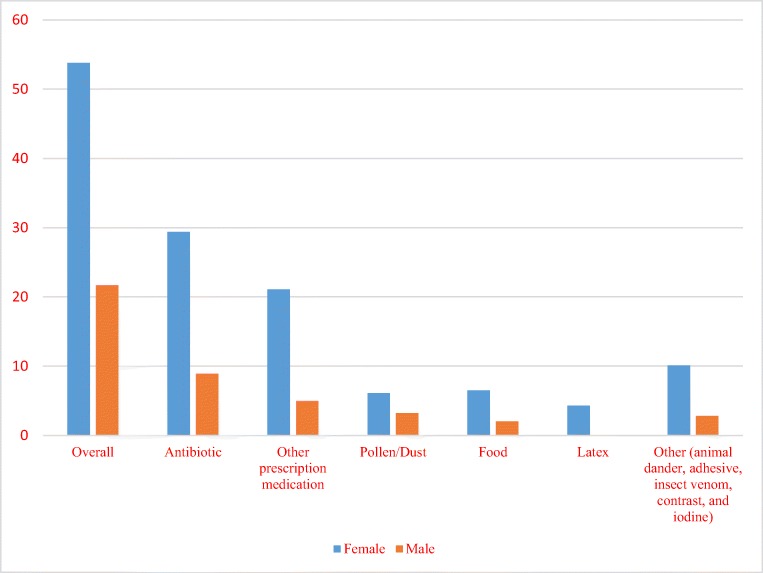

Figure 2 demonstrates prevalence of allergy and allergy subgroups in male and female patients. Over half of female patients had at least one reported allergy and 18.3% had more than one reported allergy. Among all female patients with allergy, allergy to antibiotics was most common followed by allergy to other prescription medications. Allergies to environmental and other allergens were less common. Approximately one-quarter of male subjects had missing data but from the remaining male patients, about one-quarter had at least one reported allergy. In 14% of couples with allergy data available for both partners, both partners had at least one reported allergy. The most common antibiotic allergies in both female and male patients were to penicillin and sulfa drugs (22.3% and 6.5% respectively). The most common non-antibiotic medication allergies in both male and female patients were the opiates (17.4% and 12.1% respectively).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of allergy and allergy subgroups in male and female patients. Environmental allergy included the pollen/dust, food, and latex

Comparison of patients with and without allergy subgroups

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic and clinical features of couples with and without reported female allergy. There were no statistically significant differences in female infertility diagnosis and presence of allergy. However, the proportion of patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) who had at least one allergy was marginally statistically significantly higher than women with PCOS without reported allergy (76.5% vs 23.5%, p = 0.08). There were no statistically significant differences in other demographic and clinical features of couples with and without reported female allergy with the exception of female race and nulliparity, both of which were included in the models discussed above.

Presence of allergy and IVF cycle outcomes

Table 3 outlines pregnancy and cycle outcomes in male and female patients with and without allergy. Female patients with allergy were slightly more likely to have a negative β-hCG, though this difference was only marginally statistically significant (p = 0.07). Female patients with allergy were also less likely to have a successful cycle but this was also only marginally statistically significant (p = 0.06). Female patients with allergy were not more likely to experience biochemical pregnancy or spontaneous abortion than women without allergy. In the entire cohort, only 7 ectopic pregnancies occurred, which was too small a number to calculate a comparative p value between groups. Infant outcomes, including birthweight and likelihood of a twin pregnancy, were evaluated only in those cycles that were successful as defined above. There were no statistically significant differences between patients with and without allergy in terms of infant sex, infant birthweight, and incidence of multiple birth.

Table 3.

Pregnancy and cycle outcomes by cycle for female and male patients with and without allergy (n represents number of cycles)

| No allergy | Allergy | p values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female patients | ||||

| Pregnancy outcomes | Negative β-HCG (n = 413) | 188 (46.4%) | 225 (51.6%) | 0.07 |

| Biochemical pregnancy (n = 102) | 48 (11.9%) | 54 (12.4%) | 0.84 | |

| Spontaneous abortion (n = 59) | 27 (6.7%) | 32 (7.3%) | 0.81 | |

| Ectopic pregnancy (n = 7) | 3 (0.7%) | 4 (0.9%) | -- | |

| Successful cycle (n = 260) | 139 (34.3%) | 121 (27.8%) | 0.06 | |

| Cycle outcomes | Mean endometrial thickness (mm) (n = 799) | 9.67 | 10.01 | 0.61 |

| Mean oocyte retrieved per cycle (n = 661) | 12.35 | 12.71 | 0.60 | |

| Mean number of mature oocytes per cycle (n = 173) | 9.79 | 10.46 | 0.36 | |

| Mean fertilization rate per cycle (n = 166) | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.65 | |

| Mean number abnormal fertilized oocytes per cycle (n = 173) | 0.845 | 1.07 | 0.27 | |

| Mean number of embryos transferred per cycle (n = 805) | 1.81 | 2.07 | 0.07 | |

| Mean number of embryos frozen per cycle (n = 387) | 2.78 | 2.46 | 0.36 | |

| Male patients | ||||

| Cycle outcomes | Mean semen volume (mL) (n = 450) | 2.57 | 2.48 | 0.71 |

| Mean sperm count (million/mL) (n = 410) | 77.45 | 74.40 | 0.33 | |

| Mean sperm motilitya (%) (n = 408) | 51.64 | 51.07 | 0.52 | |

| Mean total motile sperm (million/ejaculate) (n = 408) | 108.30 | 110.08 | 0.12 | |

aSperm motility includes both progressive and non-progressive motility

There were no statistically significant differences between these groups in regard to endometrial thickness at time of embryo transfer, number of oocytes retrieved, number of MII oocytes, fertilization rate, abnormal fertilization rate, or number of embryos frozen. However, the number of embryos transferred per cycle was marginally statistically significant (p = 0.07) with patients with allergy having a slightly higher number of embryos transferred (2.07 vs 1.81) while controlling for year of transfer. Given the variation in cycle success and embryo transfer practices based on patient age, stratified analyses for maternal age category (ages < 30, 30–34, 35–37, 38–40, and > 40) were performed for outcome variables of β-hCG test result (successful cycles as defined above, negative β-hCG, biochemical pregnancy, and spontaneous abortion) and number of embryos transferred. No significant relationships were identified between these variables and presence of maternal allergy except for decreased likelihood of successful cycle for those with allergy compared with those without for the 35–37-year-old group (29.1% versus 42.8%, p = 0.02). There were no differences in semen volume, sperm count, sperm motility, and total motile sperm between male patients with and without reported allergy (Table 3). Based on these results, a further sub-analysis of couples with both male and female patients having allergy was not performed.

Subcategories of allergy and IVF cycle outcomes

Table 4 demonstrates results from a sub-analysis of variables with statistically significance and marginal statistical significance (p ≤ 0.08), including negative β-hCG result, successful cycles, and mean number of embryos transferred per cycle by allergy subtype. This sub-analysis was performed to evaluate whether the lack of specificity in the overall allergy present category was obscuring a relationship between a specific allergy subgroup and the variable of interest. When stratified by allergy subtype, there were no statistically significant differences seen in cycle or pregnancy outcomes except for the number of embryos transferred in those with and without an environmental/other allergies (p = 0.02). Those with non-antibiotic prescription medication allergies were also marginally statistically significantly more likely to have more embryos transferred than those without non-antibiotic prescription allergies (p = 0.08).

Table 4.

p values for marginally statistically significant variables by allergy subtype

| Allergy subtype | Negative β-HCG | Successful pregnancy | Number of embryos transferred |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.88 |

| Non-antibiotic prescription medication | 0.13 | 0.46 | 0.08 |

| Environmental/other allergy | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.02 |

Discussion

Allergy is an increasingly prevalent health concern, with the World Allergy Organization (WAO) estimating that 10–30% of the US population is affected [31]. The prevalence of allergy in reproductive-age women is estimated to be higher at approximately 20–30% [32, 33]. In our male patients, the prevalence of allergy is comparable with the general population; however, the prevalence of female allergy was significantly greater, with 54% of female patients having at least one reported allergy. Overall, our cohort was comparable with the general population in regard to pollen/dust allergies (6.1% vs 7.6% respectively) and latex allergies (4.5% vs 4.3% respectively) but demonstrated a slightly lower prevalence of food allergies (6.5% vs 11% respectively) [31, 34–36]. Our patients had a much greater prevalence of medication allergies than the WAO’s estimates for the general population (10%, with allergy to antibiotics being the most common) [31]. One possible explanation is that women with infertility have more recognized medication allergies than the general population due to increased exposure to medical care. However, our findings of high prevalence of any allergy among women with infertility support the hypothesis that there may be a biologic relationship between allergy and infertility.

The high prevalence of allergy in our infertility population is consistent with a 2006 study by Zac et al., which demonstrated increased prevalence of infertility in Brazilian women with allergies [24]. Several other studies, though, have yielded null results or results supporting the opposite relationship. A study by Harrison et al., comparing markers of atopy in couples with and without unexplained infertility, there were no differences in markers of atopy between female infertility patients and the general population and, in a separate study by Lewis et al., women with eczema and hay fever actually had a higher live birth rate than women without these conditions [23, 28]. The results from Lewis et al., however, did not account for diagnosis of infertility, time to conceive, or need for fertility treatments; therefore, these results may not be generalizable to the infertility population [28]. Lastly, in a twin study by Gade et al., a self-reported history of allergy was not associated with an increased time-to-pregnancy, but again, association with infertility or need for fertility treatments was not evaluated, and this cohort was small, consisting of just 80 pairs of twins [29].

In terms of pregnancy and cycle outcomes, the only marginally statistically significant findings were a higher number of embryos transferred per cycle, and a lower successful in women with reported allergy. This is largely consistent with the only other previous study investigating allergy and IVF pregnancy outcomes by Matalliotakis et al. [30] The sample size in their study was small though, limited to 471 cycles in 297 individuals, and they were not able to evaluate for association of allergy with other cycle outcomes nor stratify to investigate outcomes by allergy subtype. Because of the larger sample size of our study, we were able to evaluate specific allergy subtypes and their relationship to IVF pregnancy and cycle outcomes. This is important as some allergy subtypes are thought to manifest via different immunologic mechanisms, all of which are associated with implantation and immune tolerance of pregnancy. These varying mechanisms could associate independently with different infertility outcomes [17].

We found no statistically significant differences based on presence of any allergy subgroup with the exception of number of embryos transferred in patients with and without environmental/other allergies. One possible confounder in outcomes of number of embryos transferred for cycle for both any allergy and the environmental/other allergy subgroup is embryo quality which was not included in our analysis. As this was a fully retrospective study, we do not feel that embryo morphology grading could have been affected by embryologist bias toward those with allergy, but those patients with allergy may have had lower quality embryos than patients without allergies that resulted in transferring more embryos per cycle to ensure achieving acceptable pregnancy rate. In addition, it should be noted that our patients with any allergy had a higher number of embryos transferred per cycle with a lower number of successful cycles. Although both these outcomes were only of marginal statistical significance individually, in conjunction, they are suggestive of a meaningful association that future larger studies might be able to replicate and support.

Our inability to demonstrate statistically significant associations with allergy and infertility are surprising given unexpectedly high prevalence of allergy in our population and the well-demonstrated association between other forms of immune dysfunction (i.e., autoimmune disease) and poor fertility outcomes [37, 38]. One possible explanation is that the immune responses in autoimmune disease are directed toward human tissue antigens, whereas those in allergic disease are directed toward foreign antigens, which may protect fetal tissues during early development. Additionally, unlike autoimmune disease, once an allergic stimulus is identified, the patient often makes an effort to avoid the stimulus which may lead to significantly decreased or lack of inflammation compared to that of autoimmune disease, which would possibly reduce the effect of allergy on IVF outcomes. This may explain why, for our sub-analyses by allergy type, only environmental/other allergies were significantly associated with number of embryos transferred, as these allergy types are more difficult to avoid than medication allergies. Another possible explanation is that the uterine microenvironment is not affected in the same way as the systemic environment in those with allergies, which is supported by multiple previous studies that have shown that uterine leukocytes are unique from those found in systemic circulation [39–41]. Lastly, despite this being the largest study of this kind to date, we did not have large numbers of patients with specific allergies, and we therefore grouped many allergy types together which may have obscured a true relationship between outcomes and more specific allergies.

One advantage of our study was the ability to evaluate the association of allergy and infertility diagnosis, although our sample sizes for many of the subgroups remained smaller than desired. Female patients with PCOS were found to have a high prevalence of allergy, with three-quarters of PCOS patients having an allergy. This is consistent with a study by Svanes et al. in which women with all causes of oligo-ovulation had a higher prevalence of allergy than the general population, suggesting a possible immune contribution to pathogenesis of PCOS [27]. Of note, we did not find an increased prevalence of allergy in patients with endometriosis, as had been seen in previous studies [25, 26], but this population was small in our cohort (19 women).

Future studies would ideally contain data regarding description of allergic reaction in order to help determine if reported adverse reactions are truly an allergy or an intolerance. Reaction type is of particular interest in the “other prescription medication” subgroup, as the WAO estimates that only 10% of reported adverse drug reactions are a true drug allergy [31]. If a large number of our patients had drug intolerances, as opposed to drug allergies, this may have diluted the effect of true drug allergy on pregnancy and cycle outcomes. However, the fact that our data came from the medical record with clinician discretion in regard to entry suggests that it is more likely to be representative of true allergic reactions as opposed to data generated solely by patient report. Finally, a weakness of our study is that our cohort is homogenous in terms of race which may limit generalizability. However, the US IVF population is more racially homogenous than the general population and therefore, our population is likely an accurate representation of the population undergoing IVF nationally [42].

In conclusion, there was a high prevalence of allergy in female patients undergoing IVF at our fertility clinic. We found marginally statistically significant differences in pregnancy outcomes, with allergic patients having a higher incidence of negative β-hCG and lower incidence of successful IVF cycles as well as a greater number of embryos transferred per cycle. These findings raise interesting possibilities for a relationship between the pathogenesis of allergy and certain causes of reproductive failure. A better understanding of this possible relationship may help to improve IVF outcomes and provide novel targets for IVF treatment in these patients, such as desensitization and immune modulating agents. Although this study is the largest of its kind to date, further studies are needed to confirm statistical significance and investigate possible treatment options.

Compliance with ethical standards

Institutional review board approval was obtained to access patient charts and embryology data and it was determined that no consent was needed.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Carleigh Nesbit and Julia Litzky contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Zenclussen AC, Hämmerling GJ. Cellular regulation of the uterine microenvironment that enables embryo implantation. Front Immunol. 2015;6:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanguansermsri D, Pongcharoen S. Pregnancy immunology: decidual immune cells. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2008;26:171–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito S, Sasaki Y, Sakai M. CD4(+)CD25high regulatory T cells in human pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;65:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jasper MJ, Tremellen KP, Robertson SA. Primary unexplained infertility is associated with reduced expression of the T-regulatory cell transcription factor Foxp3 in endometrial tissue. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:301–308. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasaki Y, Sakai M, Miyazaki S, Higuma S, Shiozaki A, Saito S. Decidual and peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in early pregnancy subjects and spontaneous abortion cases. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:347–353. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim KJ, Odukoya OA, Ajjan RA, Li TC, Weetman AP, Cooke ID. The role of T-helper cytokines in human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:136–142. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen PE, Nishimura K, Zhu L, Pollard JW. Macrophages: important accessory cells for reproductive function. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:765–772. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Care AS, Diener KR, Jasper MJ, Brown HM, Ingman WV, Robertson SA. Macrophages regulate corpus luteum development during embryo implantation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3472–3487. doi: 10.1172/JCI60561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plaks V, Birnberg T, Berkutzki T, Sela S, BenYashar A, Kalchenko V, Mor G, Keshet E, Dekel N, Neeman M, Jung S. Uterine DCs are crucial for decidua formation during embryo implantation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3954–3965. doi: 10.1172/JCI36682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tirado-González I, Muñoz-Fernández R, Blanco O, Leno-Durán E, Abadía-Molina AC, Olivares EG. Reduced proportion of decidual DC-SIGN+ cells in human spontaneous abortion. Placenta. 2010;31:1019–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woidacki K, Popovic M, Metz M, Schumacher A, Linzke N, Teles A, et al. Mast cells rescue implantation defects caused by c-kit deficiency. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:1–11. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vacca P, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Natural killer cells in human pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2013;97:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaouat G. Inflammation, NK cells, and implantation: friend and foe (the good, the bad and the ugly?): replacing placental viviparity in an evolutionary perspective. J Reprod Immunol. 2013;97:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang AW, Alfirevic Z, Quenby S. Natural killer cells and pregnancy outcomes in women with recurrent miscarriage and infertility: a systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1971–1980. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahdi BM. Role of some cytokines on reproduction. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2011;16:220–223. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraczek M, Kurpisz M. Cytokines in the male reproductive tract and their role in infertility disorders. J Reprod Immunol. 2015;108:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oettgen Hans, Broide David H. Allergy. 2012. Introduction to mechanisms of allergic disease; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay AB. Allergy and allergic diseases. First of two parts N Engl J Med. 2000;344:30–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kay AB. Allergy and allergic diseases. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:109–113. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101113440206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamid QA, Minshall EM. Molecular pathology of allergic disease: I: lower airway disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:20–36. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pichler WJ, Adam J, Watkins S, Wuillemin N, Yun J, Yerly D. Drug hypersensitivity: how drugs stimulate T cells via pharmacological interaction with immune receptors. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2015;168:13–24. doi: 10.1159/000441280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemp SF, Lockey RF. Anaphylaxis: a review of causes and mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:341–348. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison R, Unwin A. Atopy in couples with unexplained infertility. Br J of Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:192–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zac RI, Machado VM, Alberti LR, Petroianu A. Association of allergy, infertility, and abortion. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2005;51:177–180. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302005000300020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK, Stratton P. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2715–2724. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matalliotakis I, Cakmak H, Matalliotakis M, Kappou D, Arici A. High rate of allergies among women with endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32:291–293. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.644358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svanes C, Real FG, Gislason T, Jansson C, Jögi R, Norman E, et al. Association of asthma and hay fever with irregular menstruation. Thorax. 2005;60:445–450. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.032615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis S, West J, Hubbard R, et al. Fertility rates in women with asthma, eczema, and hay fever: a general population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1023–1030. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gade EJ, Thomsen SF, Lindenberg S, Kyvik KO, Lieberoth S, Backer V. Asthma affects time to pregnancy and fertility: a register-based twin study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1077–1085. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00148713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matalliotakis I, Cakmak H, Arici A, Goumenou A, Fragouli Y, Sakkas D. Epidemiological factors influencing IVF outcome: evidence from the Yale IVF program. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:204–208. doi: 10.1080/01443610801912436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawankar R, Holgate ST, Canonica GW, Lockey RF, Blaiss MS, editors. WAO White Book on Allergy 2013 Update. Milwaukee: World Allergy Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schatz M, Zeiger RS. Diagnosis and management of rhinitis during pregnancy. Allergy Proc. 1988;9:545–554. doi: 10.2500/108854188778965627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Incaudo GA. Diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinitis and sinusitis during pregnancy and lactation. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2004;27:159–177. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:27:2:159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, Peregory JA. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat. 2012;10:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu M, McIntosh J, Liu J. Current prevalence rate of latex allergy: why it remains a problem? J Occup Health. 2016;58:138–144. doi: 10.1539/joh.15-0275-RA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, Jiang J, Blumenstock JA, Davis MM, et al. Prevalence and severity of food allergies among US adults Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2720064. Accessed October 12, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Barad DH. Cutting edge assessment of the impact of autoimmunity on female reproductive success. J Autoimmun. 2012;38:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carp HJ, Selmi C, Shoenfeld Y. The autoimmune bases of infertility and pregnancy loss. J Autoimmun. 2012;38:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kämmerer U, Eggert AO, Kapp M, McLellan AD, Geijtenbeek TB, Dietl J, van Kooyk Y, Kämpgen E. Unique appearance of proliferating antigen-presenting cells expressing DC-SIGN (CD209) in the decidua of early human pregnancy. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:887–896. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63884-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blois SM, Alba Soto CD, Tometten M, Klapp BF, Margni RA, Arck PC. Lineage, maturity, and phenotype of uterine murine dendritic cells throughout gestation indicate a protective role in maintaining pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1018–1023. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.022640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmerse F, Woidacki K, Riek-Burchardt M, Reichardt P, Roers A, Tadokoro C, Zenclussen AC. In vivo visualization of uterine mast cells by two-photon microscopy. Reproduction. 2014;147:781–788. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Humphries LA, Chang O, Humm K, Sakkas D, Hacker MR. Influence of race and ethnicity on in vitro fertilization outcomes: systemic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(212):e1–212.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]