Abstract

α-Synuclein is a soluble monomer abundant in the central nervous system. Aggregates of α-synuclein, consisting of higher-level oligomers and insoluble fibrils, have been observed in many chronic neurological diseases and are implicated in neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration. α-Synuclein has recently been shown to aggregate following acute ischemic stroke, exacerbating neuronal damage. Propofol is an intravenous anesthetic that is commonly used during intravascular embolectomy following acute ischemic stroke. While propofol has demonstrated neuroprotective properties following brain injury, the mechanism of protection in the setting of ischemic stroke is unclear. In this study, propofol administration significantly reduced the neurotoxic aggregation of α-synuclein, decreased the infarct area, and attenuated the neurological deficits after ischemic stroke in a mouse model. We then demonstrated that the propofol-induced reduction of α-synuclein aggregation was associated with increased mammalian target of rapamycin/ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 signaling pathway activity and reduction of the excessive autophagy occurring after acute ischemic stroke.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12264-019-00426-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Propofol, α-Synuclein, Autophagy, Stroke, Neuroprotection

Introduction

α-Synuclein is a 14-kDa protein encoded by the Snca gene, which is highly conserved among vertebrates. Making up as much as 1% of all proteins in the cytosol of neurons, α-synuclein is found mainly in the presynaptic terminals [1–3]. α-Synuclein can transit between several different conformations, including soluble monomers (14 kDa), oligomers and higher-level oligomers (26–180 kDa), and insoluble fibrils (> 180 kDa) [4, 5]. In vivo, α-synuclein likely exists in monomeric form and as a helically-folded tetramer which may confer resistance to pathologic aggregation [6].

The association between chronic diseases of the central nervous system, including Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, and the presence of α-synuclein aggregates is well known [5, 9]. However, the role of α-synuclein in acute injury of the brain has been little studied. α-Synuclein aggregates, consisting of higher-level oligomers and insoluble fibrils, are thought to have neurotoxic properties and are implicated in severe neuronal loss and the eventual development of neurological deficits [7, 8]. α-Synuclein interacts specifically with proteins involved in the regulation of oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial function, and its oligomers increase the level of oxidative stress in neurons [10, 11]. The overexpression of Snca and increased production of α-synuclein have been shown to exacerbate autophagy following ischemic stroke [12, 13]. While both oxidative phosphorylation and autophagy are vital physiological processes, they prove detrimental at high levels following acute ischemic brain injury [14, 15].

Propofol (2,6-disopropylphenol) is the most commonly used intravenous general anesthetic in emergency procedures. Studies have suggested that propofol administration reduces the infarct size and improves the outcome of acute ischemic stroke [16, 17]. However, the neuroprotective mechanism of propofol in this setting remains obscure. In this study, we hypothesized that propofol decreases α-synuclein aggregation and decreases ischemic stroke-induced excessive autophagy via the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 (S6K1) signaling pathway. We tested this hypothesis in a mouse model of acute ischemic stroke and evaluated α-synuclein aggregation, infarct area, neurological deficits, gene expression profiles, and autophagy following treatment with propofol.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatment

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Capital Medical University (AEEI-2018-120). Specific pathogen-free C57BL/6 J mice (25 g–30 g) were raised with free access to water and standard food. Ischemic stroke in the right focal somatosensory cortex was created using a previously published protocol [18–20].

In brief, the procedure was performed under 1.5% isoflurane (#R510-22, RWD Life Science, San Diego, CA) for maintenance of anesthesia. The selected branch of the right middle cerebral artery was permanently ligated with 10-0 suture (#w2790, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), with temporary clamping of the bilateral common carotid arteries for 7 min. Mice were given propofol (16 mg/kg, #260929, Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) by intraperitoneal injection (IP) or the same volume of 0.9% normal saline (1.6 mL/kg, IP) at the time of reperfusion. They received additional maintenance IP propofol (10–12 mg/kg every half-hour) or the same volume of 0.9% normal saline for two hours, in consideration of the rapid induction of anesthesia for emergency surgery for acute ischemic stroke. Only skin dissection was performed in the sham procedure group. The sham group was also given 0.9% normal saline IP during and after the procedure. The skin incision was closed using Vetbond tissue adhesive (#1469SB, 3 M Company, MN). Mice were returned to their cages after recovery from anesthesia. Body temperature was monitored and maintained with a heating pad during anesthesia and surgery. All procedures were conducted between 09:30 and 11:30.

Western Blot Analysis

Infarcted cortex was harvested 24 h after stroke. Thermo M-PER mammal Protein Extract Reagent (#78501, Waltham, MA) with complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (#11697498001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and PhosSTOP™ phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablets (#04906845001, Roche) were used for sample homogenization. The homogenate was then separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (0.2 μm). The blots were blocked in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.5% Tween-20 (#P9416, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and Difco skim milk (10% m/v, #232100, BD, San Jose, Canada) for 1 h after transfer. The blocked membrane was incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. HRP immunoblots were developed using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (#WBKLS0500, Millipore, MA, USA). Blots were exposed to Molecular Imager (ChemiDo XRS + , Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and analyzed with ImageJ software (Version 1.52).

The antibodies used for western blot were anti-LC3B (1:2000 dilution, #L7543, Sigma), anti-α-synuclein (1:1500 dilution, #2642, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), anti-S6K1 phospho T389 (1:500 dilution, #ab2571, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-S6K1 (1:10000 dilution, #ab32529, Abcam), anti-β-actin (1:5000 dilution, #A5316, Sigma), goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:150000 dilution, #A0545, Sigma), and goat anti-mouse IgG (1:150000 dilution, #A9044, Sigma). A pre-stained protein ladder (#26616, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used as the molecular weight marker.

Immunofluorescence

Frozen brain tissue was cut into 10 μm-thick coronal sections on a cryostat vibratome (Leica CM 1860, Wetzlar, Germany) 24 h after stroke. The sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-X 100 (Sigma) for 15 min. The sections were then blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum for 60 min at room temperature and incubated with primary antibody (anti-LC3B, 1:500 dilution, #L7543, Sigma; Anti-NeuN, 1:1000 dilution, #ab104224, Abcam) and secondary antibody (#A-21206 and #A10036, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 4 °C. DAPI Fluoromount-G (#36308ES11, Yeasen, Shanghai, China) was used as the mounting medium. Imaging was performed using the Olympus microscope system and analyzed via the ImageJ (Version 1.52) automatic puncta analysis procedure.

Transcriptome Sequencing

RNA from the infarcted cortex was sequenced at 24 h after ischemic stroke. The RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (#E7530L, NEB, MA, USA) and index codes were used to attribute sequences in each sample. RNA Library concentrations were measured using the RNA Assay Kit in Qubit 3.0 (#Q10211, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for preliminary quantification. The Bio analyzer 2100 System (Agilent Technologies, CA) was used to assess the insert size. Qualified inserts were further quantified using the Step One Plus Real-Time PCR System (#4376600, Thermo Scientific). The index-coded sample library was clustered using the cBot cluster generation system (HiSeq PE Cluster Kit v4-Cbot-HS, Illumina, CA) and sequenced on the Illumina platform.

2,3,5-Triphenyl Tetrazolium Chloride (TTC) Staining

Mice were sacrificed 72 h after stroke. The brain was cut coronally into 1-mm slices. After staining with 2% TTC (#T8877, Sigma) for 15 min at 37°C in darkness, the slices were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 12 h. The whole area and infarct area of each section were measured with ImageJ (Version 1.52). The results are expressed as the ratio of infarct volume to whole brain volume × 100%.

Behavioral Testing

Experimenters were blinded to study group during all behavioral tests. In the sticky-label test, a square (2 × 2 mm2) of medical adhesive tape (3 M Company) was placed on the mouse forepaw. The mice were then allowed to move freely. The latency and time to remove the tape were recorded. The latency was defined as the time between tape placement and the animal’s first attempt to remove it; i.e. shaking its paw or biting the tape. The right and left forepaws were tested separately in an alternating manner, with an interval of at least 10 min. Testing with the right forepaw was considered to be the ipsilateral sticky-label test, and testing with the left forepaw the contralateral sticky-label test, relative to the induced lesion. Mice were trained 3 times a day on each forepaw for 3 days prior to stroke. The same procedure was performed 24 h after stroke.

The whisker tests were performed as previously described to assess fine neurological deficits [21]. In mice, sensation in the whiskers projects to the contralateral barrel cortex of S1 (Fig. 1E), which is specifically covered in the stroke model used in this study [22]. In the whisker-evoked forelimb placing test, a mouse was gently held by the torso and the whiskers on one side were brushed against the corner of a platform to elicit ipsilateral forelimb placement on the platform. For the whisker-evoked cross-midline forelimb placing test, a mouse was held by the torso and rotated 45° onto its side. Then, the whiskers on the lower side were brushed perpendicularly against the edge of the corner platform to elicit contralateral (upper side) forelimb placement on the platform. The eyes were covered to avoid visual input during the tests. In both tests, if the mouse could place the forelimb on the platform after brushing the whisker, it was recorded as a success. If the mouse remained motionless or moved and failed to place its forelimb on the platform, it was recorded as a failure. Trials in which the animal struggled were not counted. Testing with brushing of the right whiskers was considered ipsilateral, and testing with the left whiskers contralateral, relative to the induced lesion (Fig. 1F). Mice underwent 10 training trials a day on the whiskers on both sides in the whisker-evoked forelimb placing and cross-midline tests for 3 days prior to stroke. The same procedures were used during testing at 24 h after stroke.

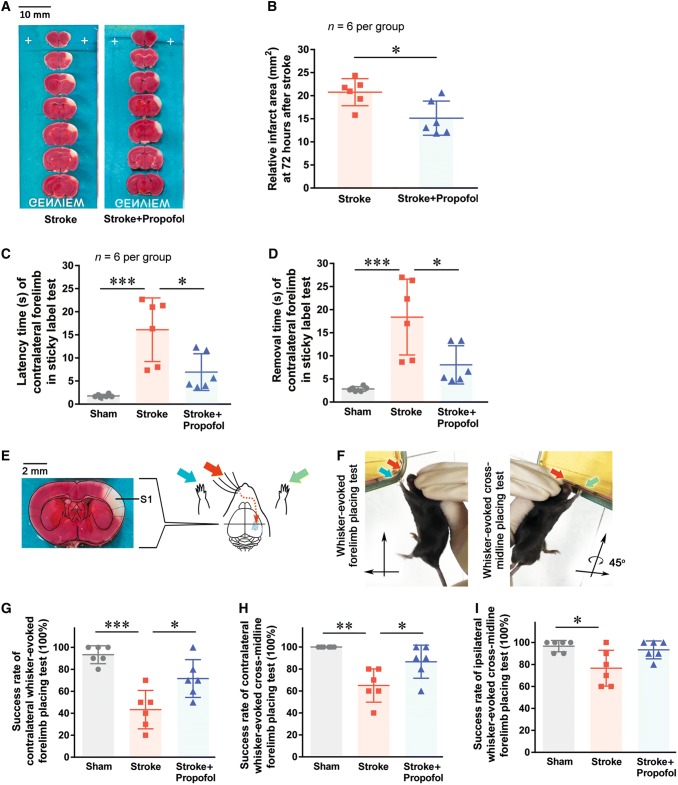

Fig. 1.

Propofol reduces the neurological deficit after ischemic stroke. A Typical TTC staining results. The viable area of each slice is stained red, while the infarcted area is white. B Relative infarct area measured 72 h after stroke. C and D Latency and removal time in the sticky-label test 24 h after stroke. E Schematic of the stroke region and whisker tests. F Images of the whisker-evoked placing tests. G Contralateral whisker-evoked forelimb placing test. H Contralateral cross-midline placing test. I Ipsilateral cross-midline test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

R (Version 5.2.0, New Zealand) was used for bioinformatics and statistical analysis. Following transcriptome sequencing, differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) between the propofol and stroke groups were identified using DEseq2 (https://github.com/mikelove/DESeq2). Term enrichment analysis with Bonferroni correction was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), the KEGG Orthology-Based Annotation System, and the Gene Ontology (GO) Consortium databases. STRING (Version 10.5, Cambridgeshire, UK) was used for protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis. The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID Bioinformatics Resources, Version 6.8) was used for statistical analysis. Benjamini-Hochberg correction-adjusted P values were used in all bioinformatics analyses. Two-tailed t-tests were used to compare TTC-staining data in the stroke and propofol groups. Bonferroni-adjusted one-way ANOVA was used to analyze western blot, immunofluorescence and behavioral tests. The expression levels of p-S6 K were adjusted by the corresponding total S6 K protein levels, and other protein levels were adjusted by the corresponding β-actin. The expression levels in the stroke and propofol groups were normalized to the sham group. Data are presented as the average with standard deviation.

Results

Propofol Reduces the Infarct Size After Ischemic Stroke

TTC staining showed a relative reduction of 27.10% of the infarct area in the propofol group compared to the stroke group (P = 0.016) (Fig. 1A, B).

Propofol Improves the Neurological Outcome After Ischemic Stroke

In the contralateral sticky-label test, both the latency and removal time were significantly longer after ischemic stroke than in the sham group (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1C, D). These delays were significantly reduced with propofol administration. Mice receiving propofol after ischemic stroke did not have significant differences in performance on the contralateral sticky-label test compared to the sham group (P = 0.329). There were no differences between groups for the ipsilateral sticky-label test. These results suggested that propofol treatment alleviates the stroke-induced neurological deficit.

In the contralateral whisker-evoked forelimb placing test and cross-midline test, the mice receiving propofol after stroke achieved higher success rates than the stroke group (P = 0.015 and P = 0.025) (Fig. 1G, H). There was no significant difference in success rate between groups for the ipsilateral whisker-evoked forelimb placing test. In the ipsilateral whisker-evoked cross-midline forelimb placing test, mice in the propofol group achieved a higher success rate than those in the stroke group (Fig. 1I, P = 0.019 sham vs stroke; P = 1.00 sham vs propofol; P = 0.056 stroke vs propofol). The mice receiving propofol after ischemic stroke did not have significant differences in success rate compared to the sham group in any of the whisker tests.

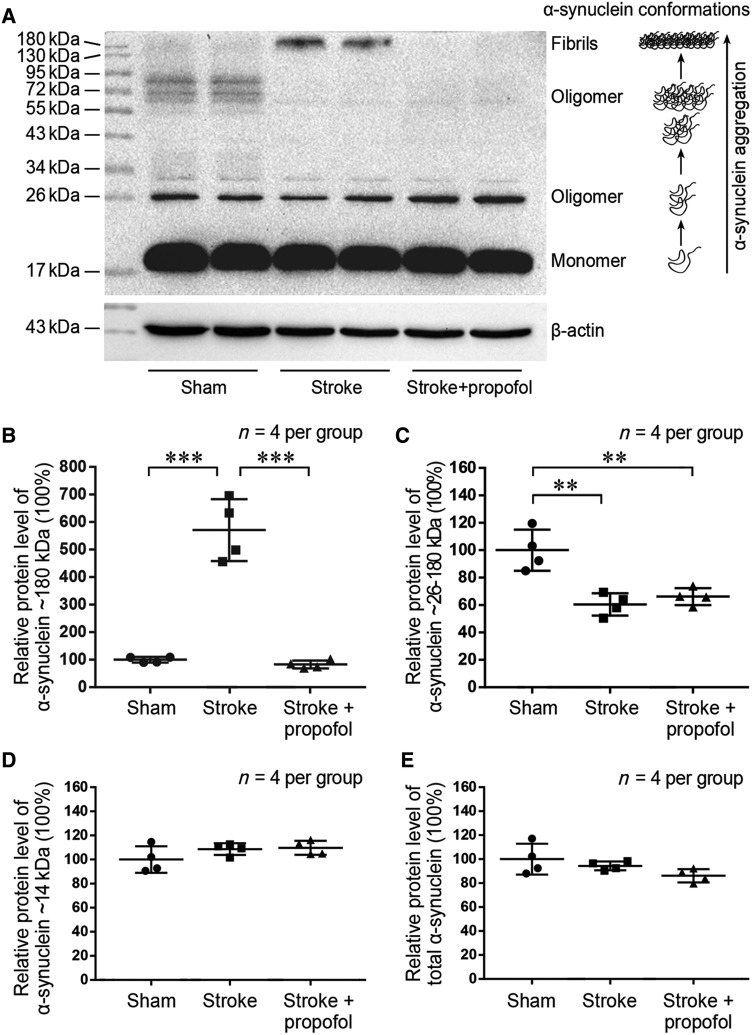

Propofol Attenuates the Ischemia-Induced α-Synuclein Aggregation Early After Ischemic Stroke

Fibrils of α-synuclein, which have high molecular weight of 180 kDa, were minimally expressed in the sham group, while significant aggregation of α-synuclein into fibrils was observed following ischemic stroke (Fig. 2A). In mice receiving propofol, stroke-induced α-synuclein aggregation into fibrils was remarkably reduced at 24 h compared to the stroke group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A, B). The relative protein levels of α-synuclein oligomers, with molecular weights of 26–180 kDa, also decreased after ischemic stroke (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2A, C). Propofol administration had minimal effect on the total α-synuclein (P = 0.587) (Fig. 2E). The levels of monomeric α-synuclein and total α-synuclein did not change significantly after ischemic stroke or propofol administration (Fig. 2A, D and E). These results suggest that the treatment with propofol specifically attenuates the levels of α-synuclein fibrils after ischemic stroke.

Fig. 2.

Propofol reduces stroke-induced α-synuclein aggregation at 24 h post-stroke. A Western blots of α-synuclein in the sham, stroke, and stroke + propofol groups. B–D Relative protein expression levels of α-synuclein at 180, 26–180, and 14 kDa molecular weights. E Relative protein expression levels of total α-synuclein. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Propofol Alters the Gene Expression Profile in Infarcted Cortex After Ischemic Stroke

To investigate the mechanism by which propofol alleviates α-synuclein and improves the prognosis of stroke, we sequenced RNA from the infarcted cortex 24 h after ischemic stroke. From a total of 20,606 expressed genes identified, 141 DEGs were down-regulated and 28 DEGs were up-regulated in the propofol group compared to the stroke group (P < 0.05, absolute value of logarithmic fold change > 1.00) (Fig. 3A).

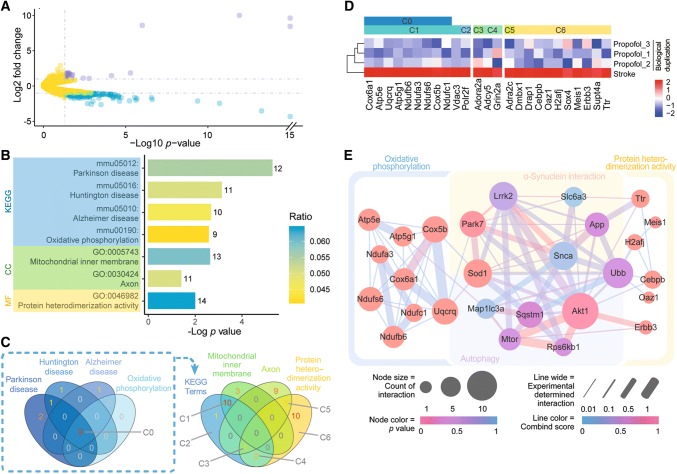

Fig. 3.

Differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) in the stroke and propofol groups identified using RNA-sequencing. A Volcano plot showing upregulated (violet) and downregulated (blue) DEGs in the infarcted areas of mice treated with propofol (yellow, genes without significant changes in expression). B KEGG and GO term-enrichment analysis of downregulated DEGs. C Venn plot of terms identified in enrichment analysis. D Heatmaps of down-regulated DEGs enriched in KEGG terms and protein heterodimerization activity. E Protein-protein interaction network analysis of proteins encoded by DEGs enriched in terms of oxidative phosphorylation and protein heterodimerization activity, proteins related with α-synuclein, and proteins that regulate the mTOR-autophagy pathway. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology; CC, Cellular Component; MF, Molecular Function. All P values based on RNA sequencing analysis.

For the down-regulated DEGs in the propofol group, term-enrichment analysis identified 4 terms from the KEGG and 3 terms from the GO database after Bonferroni correction (Fig. 3B). Gene set C0 denotes 9 down-regulated DEGs which notably represent the overlap between the 4 identified KEGG terms Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, Alzheimer disease, and oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 3C). Gene set C0 also had prominent overlap with down-regulated DEGs enriched in the GO term mitochondrial inner membrane (Fig. 3C, D). Figure 3D is a heatmap of relative expression levels of down-regulated DEGs in the propofol group which were enriched in KEGG terms and the GO term protein heterodimerization activity. No down-regulated DEGs were significantly enriched in the biological process type of GO terms after Bonferroni correction. No up-regulated DEGs were significantly enriched in any GO or KEGG pathway after Bonferroni correction.

There was no significant difference in the gene expression levels of α-synuclein in the propofol and stroke groups on RNA sequencing. This result corresponded with the unchanged protein expression level of total α-synuclein in immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2E), suggesting that propofol regulates α-synuclein after transcription.

Propofol is Involved in the Crosstalk Between α-Synuclein, Proteins Encoded by Enriched Down-Regulated DEGs, and Proteins Involved in Autophagy

To investigate the relationship between transcriptional changes in DEGs and α-synuclein protein aggregation, PPI network analysis was performed using STRING. Proteins encoded by the down-regulated DEGs enriched in the KEGG term oxidative phosphorylation and the GO term protein heterodimerization activity were correlated with α-synuclein and genes of mTOR-modulated autophagy (Fig. 3E). These PPI results suggest that propofol treatment is involved in interactions between α-synuclein and autophagy-associated proteins after ischemic stroke. Since both Snca and autophagy-related genes from the PPI network analysis were not significantly changed in our RNA sequencing analysis (Fig. 3E, all P values > 0.05), it is possible that propofol plays roles in the regulation of autophagy and α-synuclein aggregation after transcription.

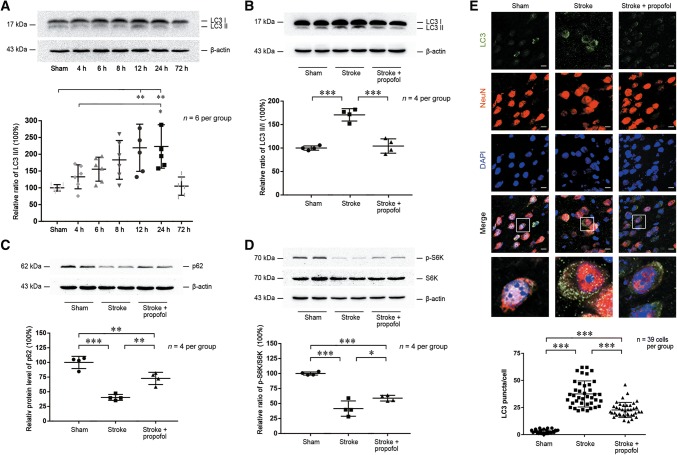

Propofol Attenuates the Increased Autophagy After Ischemic Stroke

To test the hypothesis that propofol decreases the post-stroke α-synuclein aggregation via the regulation of autophagy, we focused on typical proteins in the autophagy pathways. The gene Map1lc3a, which was identified as a node in the PPI analysis (Fig. 3E), encodes both microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 I (LC3 I) and II (LC3 II) [23], which are involved in autophagy. Western blot analysis showed that the LC3 II:I ratio increased early after stroke, with a prominent increase at 24 h, followed by a decrease at 72 h (Fig. 4A). Corrected P-values between groups are shown in Table S1. The increase in LC3 II:I ratio was rescued after propofol administration when compared to the stroke group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Propofol increases the mTOR/S6K1 pathway activity to alleviate stroke-induced abnormal autophagy. A Western blots of LC3 in the stroke group from 4 h to 72 h post-stroke. B–D Western blots (upper panels) and statistics (lower panels) of differential protein expression levels of LC3, p62, and pS6K/S6K among sham, stroke, and propofol groups 24 h post-stroke. E Upper panels, photomicrographs of immunofluorescence of LC3 puncta merged with NeuN and DAPI in the sham, stroke, and propofol groups 24 h post-stroke. Scale bars, 10 μm. Lower panel, statistics for LC3 puncta merged with NeuN in randomly-selected sections from each group (n = 39 random cells/group from four mice/group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001).

As the Sqstm1 gene was identified as a node in the PPI analysis (Fig. 3E), we measured the degradation of sequestosome 1 (ubiquitin-binding protein p62) encoded by this gene, to further investigate if autophagic flux was affected by propofol [24]. Immunoblot analysis showed that the p62 levels were reduced after ischemic stroke and preserved in the propofol group (P = 0.002) (Fig. 4C).

Immunofluorescence was further used to detect the autophagy of LC3 [24]. In the propofol group, the total area of punctate LC3 was higher than that in the sham group but to a lesser extent than that in the stroke group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4E). In both stroke and propofol groups, LC3 puncta displayed a qualitative overlap with NeuN, a neuronal nuclear antigen used as a biomarker for neurons.

These results suggested that autophagy is increased 24 hours after stroke and this stroke-induced autophagy is attenuated by propofol.

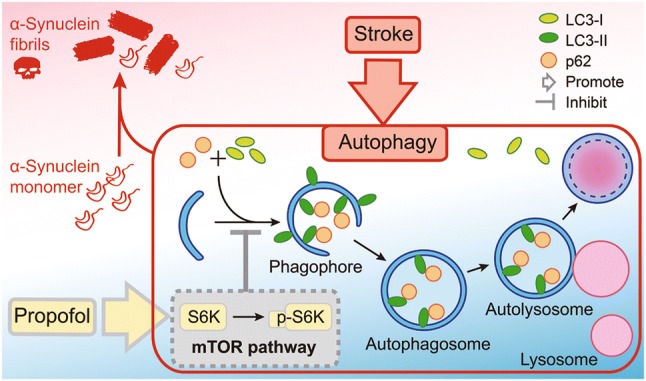

Propofol Increases the Activity of the mTOR/S6K1 Signaling Pathway to Inhibit Autophagy

To study the regulatory mechanism of propofol in stroke-induced autophagy, we focused on its upstream mediator, ribosomal protein S6K1. Encoded by Rps6kb1, S6K1 is one of the main downstream targets of mTOR and its involvement was predicted in the PPI network analysis. We measured the activation of the mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway via the phosphorylation of S6K1 by mTOR [25]. The ratio of phosphorylated S6K1 to S6K1 decreased significantly after ischemic stroke, indicating decreased mTOR/S6K1 pathway activity. This effect was partially reversed by propofol (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4D). Based on these results, we suggest that propofol decreases autophagy after ischemic stroke via increased activation of the mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Proposed mechanism for the neuroprotective action of propofol in ischemic stroke. Propofol decreases α-synuclein aggregation to reduce the increased level of autophagy after stroke via activation of the mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that treatment with propofol inhibits α-synuclein aggregation and reduces the neurological deficits following acute ischemic stroke. Previous studies have shown that abnormal aggregation of α-synuclein has serious neurotoxic effects in the long-term chronic progression of neurodegeneration [5]. We argue and emphasize that, even in the short time-frame of acute ischemic stroke, the neurotoxic effects of α-synuclein aggregation cannot be underestimated and may be prevented.

After ischemic stroke, α-synuclein in neurons aggregates into higher-level oligomers and insoluble fibrils, which are difficult to degrade once formed [36]. These aggregates induce mitochondrial damage and disrupt oxidative phosphorylation [32], leading to greater oxidative stress [11]. Oxidative stress in turn leads to additional accumulation of additional α-synuclein aggregates [33]. Furthermore, both α-synuclein and oxidative stress augment autophagy, including negative regulation of the mTOR/S6K1 pathway by α-synuclein overexpression [26, 27, 34, 35]. We suggest that propofol can break this vicious cycle by preventing the initial aggregation of α-synuclein and reducing the initial peak of autophagy in the early stage of ischemic stroke.

In our mouse model, ischemic stroke resulted in measurable sensory and motor neurological deficits at 24 h. Our results concur with previous studies showing significant aggregation of α-synuclein into insoluble fibrils and higher-level oligomers following stroke. With propofol treatment after stroke, the levels of α-synuclein fibrils were significantly reduced. Total infarct size on post-stroke pathology and neurological deficits were similarly attenuated with propofol administration. Furthermore, transcriptome sequencing identified down-regulated DEGs associated with the major neurodegenerative diseases Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, and Alzheimer disease, and oxidative phosphorylation on term-enrichment analysis. The finding that total α-synuclein levels on immunoblot analysis and RNA sequencing were both unchanged after propofol treatment supports the hypothesis that propofol regulates α-synuclein aggregation after transcription.

We further investigated the neuroprotective mechanism of propofol in the setting of acute ischemic stroke, focusing on the increased level of autophagy after stroke as previously reported. PPI network analysis showed that the proteins encoded by DEGs that were down-regulated after propofol treatment were related to both α-synuclein and proteins of mTOR-modulated autophagy. Markers of autophagy and autophagic flux were reduced by propofol treatment, and this was accompanied by an increase in mTOR/S6K1 pathway activity.

This study has several limitations. First, although we showed that propofol decreases both α-synuclein aggregation and stroke-induced autophagy, and identified interactions between α-synuclein and the mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway using sequencing analysis, further experiments are needed to verify the relationship between α-synuclein and the mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway in our stroke model. Besides, additional investigation is needed on the relationship between α-synuclein aggregation and neurological damage after acute ischemic stroke, since α-synuclein interacts with numerous proteins involved in the regulation of mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, autophagy, vesicular trafficking, signal transduction, and synaptic transmission [11, 27].

Besides, in addition to reducing α-synuclein aggregation, propofol may improve stroke outcomes through other mechanisms. Recent studies have shown that propofol has an important capacity of trapping liposome-bound proteins at the presynaptic terminal [28]. Moreover, α-synuclein is not only primarily expressed at the presynaptic terminal, but also promotes liposome-bound protein complex assembly [3]. α-Synuclein also binds to membrane lipids to induce membrane curvature, a key process in the initialization of autophagy [3, 29–31]. Nevertheless, in addition to the mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway, other pathways involved in autophagic flux might be affected by α-synuclein [27]. Further investigations are needed for these possibilities.

Previous studies have reported increased α-synuclein fibrils and oligomers after stroke [12], while we found increased α-synuclein fibrils and decreased α-synuclein oligomers after ischemic stroke. This phenomenon might be attributed to the rapid pathological changes caused by acute ischemic stroke, which resulted in the aggregation of α-synuclein oligomers into fibrils at the time point we examined (24 h after ischemic stroke), and might be due to the different ischemic model used in our study. Nevertheless, α-synuclein fibrils are already known to be detrimental [7, 8]. However, it is yet in dispute whether α-synuclein oligomers (26–180 kDa) are neurotoxic, which might differ between soluble and insoluble oligomers, and between oligomers and higher-level oligomers of α-synuclein [7, 8]. These issues need further studies.

In conclusion, propofol treatment after ischemic stroke decreases α-synuclein aggregation and reduces stroke-induced autophagy associated with activation of the mTOR/S6K1 pathway. By exerting this neuroprotective effect, propofol treatment may improve the prognosis following acute ischemic stroke.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mengyao Qu and Yushang Zao for surgical assistance with the mouse stroke model. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771139) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7194270).

Conflict of interest

All authors claim that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Yuzhu Wang and Dan Tian have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Anshi Wu, Email: wuanshi88@163.com.

Yun Yue, Email: yueyun@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Iwai A, Masliah E, Yoshimoto M, Ge N, Flanagan L, de Silva HA, et al. The precursor protein of non-A beta component of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron. 1995;14:467–475. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90302-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra S, Chen X, Rizo J, Jahn R, Südhof TC. A broken alpha-helix in folded alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15313–15318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burré J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Südhof TC. Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science. 2010;329:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1195227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diógenes MJ, Dias RB, Rombo DM, Vicente Miranda H, Maiolino F, Guerreiro P, et al. Extracellular alpha-synuclein oligomers modulate synaptic transmission and impair LTP via NMDA-receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2012;34:11750–11762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0234-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong YC, Krainc D. α-Synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2017;23:1–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartels T, Choi JG, Selkoe DJ. α-Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature. 2011;477:107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature10324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pieri L, Madiona K, Bousset L, Melki R. α-Synuclein and Huntingtin exon 1 assemblies are toxic to the cells. Biophys J. 2012;102:2894–2905. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winner B, Jappelli R, Maji SK, Desplats PA, Boyer L, Aigner S, et al. In vivo demonstration that α-synuclein oligomers are toxic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4194–4199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100976108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharon R, Bar-Joseph I, Frosch MP, Walsh DM, Hamilton JA, Selkoe DJ. The formation of highly soluble oligomers of alpha-synuclein is regulated by fatty acids and enhanced in Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2003;37:583–595. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonini NM, Giasson BI. Snaring the function of alpha-synuclein. Cell. 2005;123:359–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cremades N, Cohen SI, Deas E, Abramov AY, Chen AY, Orte A, et al. Direct observation of the interconversion of normal and toxic forms of alpha-synuclein. Cell. 2012;149:1048–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unal-Cevik I, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Yemisci M, Lule S, Gurer G, Can A, et al. Alpha-synuclein aggregation induced by brief ischemia negatively impacts neuronal survival in vivo: a study in [A30P]alpha-synuclein transgenic mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:913–923. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim T, Mehta SL, Kaimal B, Lyons K, Dempsey RJ, Vemuganti R. Poststroke induction of α-synuclein mediates ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci. 2016;36:7055–7065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1241-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ham PB, Raju R. Mitochondrial function in hypoxic ischemic injury and influence of aging. Prog Neurobiol. 2017;157:92–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang P, Shao BZ, Deng Z, Chen S, Yue Z, Miao CY. Autophagy in ischemic stroke. Prog Neurobiol. 2018;163–164:98–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelb AW, Bayona NA, Wilson JX, Cechetto DF. Propofol anesthesia compared to awake reduces infarct size in rats. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1183–1190. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200205000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Jianhai, Xia Yunfei, Xu Zifeng, Deng Xiaoming. Propofol Suppressed Hypoxia/Reoxygenation-Induced Apoptosis in HBVSMC by Regulation of the Expression of Bcl-2, Bax, Caspase3, Kir6.1, and p-JNK. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2016;2016:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2016/1518738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song M, Yu SP, Mohamad O, Cao W, Wei ZZ, Gu X, et al. Optogenetic stimulation of glutamatergic neuronal activity in the striatum enhances neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of normal and stroke mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;98:9–24. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei ZZ, Zhang JY, Taylor TM, Gu X, Zhao Y, Wei L. Neuroprotective and regenerative roles of intranasal Wnt-3a administration after focal ischemic stroke in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;38:404–421. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17702669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong B, Li A, Lou Y, Chen S, Long B, Peng J, et al. Precise cerebral vascular atlas in stereotaxic coordinates of whole mouse brain. Front Neuroanat. 2017;11:128. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2017.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodlee MT, Asseo-García AM, Zhao X, Liu SJ, Jones TA, Schallert T. Testing forelimb placing across the midline reveals distinct, lesion-dependent patterns of recovery in rats. Exp Neurol. 2005;191:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldmeyer D, Brecht M, Helmchen F, Petersen CC, Poulet JF, Staiger JF, et al. Barrel cortex function. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;103:3–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, Abedin MJ, Abeliovich H, Acevedo Arozena A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy 2016, 12: 1–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3:542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magalhaes J, Gegg ME, Migdalska-Richards A, Doherty MK, Whitfield PD, Schapira AH. Autophagic lysosome reformation dysfunction in glucocerebrosidase deficient cells: relevance to Parkinson disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:3432–3445. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao S, Duan C, Gao G, Wang X, Yang H. Alpha-synuclein overexpression negatively regulates insulin receptor substrate 1 by activating mTORC1/S6K1 signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;64:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Button RW, Roberts SL, Willis TL, Hanemann CO, Luo S. Accumulation of autophagosomes confers cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:13599–13614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.782276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bademosi AT, Steeves J, Karunanithi S, Zalucki OH, Gormal RS, Liu S, et al. Trapping of Syntaxin1a in presynaptic nanoclusters by a clinically relevant general anesthetic. Cell Rep. 2018;22:427–440. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendor JT, Logan TP, Edwards RH. The function of alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2013;79:1044–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menzies FM, Fleming A, Caricasole A, Bento CF, Andrews SP, Ashkenazi A, et al. Propagation of pathological α-synuclein in marmoset brain. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5:5–12. doi: 10.1186/s40478-016-0407-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menzies FM, Fleming A, Caricasole A, Bento CF, Andrews SP, Ashkenazi A, et al. Autophagy and neurodegeneration: pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Neuron. 2017;93:1015–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grassi D, Howard S, Zhou M, Diaz-Perez N, Urban NT, Guerrero-Given D, et al. Identification of a highly neurotoxic alpha-synuclein species inducing mitochondrial damage and mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E2634–E2643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713849115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binolfi A, Limatola A, Verzini S, Kosten J, Theillet F, Rose HM, et al. Intracellular repair of oxidation-damaged α-synuclein fails to target C-terminal modification sites. Nature Commun. 2016;7:10251. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J, Wang X, Lu Y, Duan C, Gao G, Lu L, et al. Pink1 interacts with α-synuclein and abrogates α-synuclein-induced neurotoxicity by activating autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e3056. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao QD, Viswanadhapalli S, Williams P, Shi Q, Tan C, Yi X, et al. NADPH oxidase 4 induces cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy through activating Akt/mTOR and NFκB signaling pathways. Circulation. 2015;131:643–655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fink AL. The aggregation and fibrillation of α-synuclein. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:628–634. doi: 10.1021/ar050073t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.