Abstract

Fusarium head blight (FHB) is a devastating wheat disease worldwide. To decipher the genetic architecture of FHB resistance in Chinese germplasm, a Wheat Association Panel for Scab Research (WAPS) consisting of 240 leading Chinese wheat cultivars and elite lines was genotyped using the 90K single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays. The FHB response was evaluated in the field nurseries in Wuhan in Hubei Province over four consecutive years from 2014 to 2017. Five quantitative trait loci (QTL) were consistently identified on chromosome arms 1AS, 2DL, 5AS, 5AL, and 7DS using a mixed linear model (MLM), explaining 5.6, 10.3, 5.7, 5.4, and 5.6% of phenotypic variation, respectively. The QTL on 5AS, 5AL, and 7DS QTL are probably novel. The allelic frequency analysis indicated that cultivars from the Middle and Lower Yangtze River Valleys harbored more favorable alleles and were therefore more resistant than those from other regions. To facilitate in-house germplasm screening and marker-assisted selection (MAS), SNP-derived PCR markers were developed for the QTL regions on 1AS, 5AS, and 5AL QTL. In addition to the above five QTL, the WAPS population had a very low frequency of Fhb1, confirming that the gene is not widely used in Chinese wheat breeding programs. The resistant lines and molecular markers developed in this study are resources and information for enhancing FHB resistance in breeding populations by marker-assisted recurrent selection and gene stacking.

Keywords: Fusarium graminearum, genome-wide association study, marker-assisted selection, single nucleotide polymorphism, Triticum aestivum

Introduction

Fusarium head blight, caused mainly by the fungus Fusarium graminearum Schwabe, is a devastating disease of wheat worldwide, particularly in warm and humid regions (Bai et al., 2018). FHB greatly reduces grain yield and end-use quality (Bai and Shaner, 1994; Dexter et al., 1996, 1997). Infected grains contain Fusarium toxins, mainly B type trichothecenes, such as DON, 3-O-acetyl-DON (3-AcDON), 15-O-acetyl-DON (15-AcDON), DON-3-G, and NIV, making grain unsuitable for food and feed (McMullen et al., 1997; Foroud et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019). The incidence and severity of FHB in China, particularly in the Yellow and Huai River Valley, have increased over the last two decades (Ma et al., 2016), mainly due to the long-time maize-wheat rotation practice, straw retention, reduced tillage, and climate change. Although FHB can be partially managed with agronomic and agrochemical measures, genetic improvement of host resistance remains the best approach for controlling this disease.

Resistance to FHB is a typical quantitative trait and the infection process is complicated. Plant morphological and phenological traits and their growing environments all affect FHB infection (Bai et al., 2018). Buerstmayr et al. (2019) summarized the influence of plant height, AE and heading date/flowering time on FHB response. Taller plant height and higher AE contribute to FHB resistance. Different heading date/flowering time results in differences in weather conditions during disease infection and development, but the differences vary depending on specific environments and could lead to either positive, negative or no correlation to FHB responses. Due to the close correlation between morphological traits and FHB resistance, it is critical to include these traits in FHB resistance studies.

Using linkage analysis, QTL for FHB resistance have been mapped on all 21 wheat chromosomes partitioned into 44 chromosomal regions (Buerstmayr et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2020). To date, seven FHB genes (Fhb1–Fhb7) have been formally cataloged. Fhb2 on the short arm of 6B, Fhb4 on the long arm of 4B, and Fhb5 near the centromere of 5A were finely mapped (Jia et al., 2018). Qfhs.ifa-5A from a Sumai 3 derivative CM-82036 was finely mapped as two closely linked QTL Qfhs.ifa-5Ac and Qfhs.ifa-5AS (Steiner et al., 2019). Qfhs.ifa-5Ac overlapped with Fhb5 according to their mapping intervals.

Fhb1 on chromosome arm 3BS is the most important and widely studied (Buerstmayr et al., 2009). It was first identified as a PFT gene (Rawat et al., 2016) and later as a TaHRC or His gene located adjacent to PFT (Su et al., 2019; Li G. et al., 2019). However, the molecular nature of this gene needs further study (Lagudah and Krattinger, 2019). Functional markers developed from TaHRC in the Fhb1 region were validated as diagnostic and, therefore, useful for MAS of Fhb1 (Su et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018). QFhb.mgb-2A originally mapped in a Sumai 3 derived wheat line 02-5B-318 (Giancaspro et al., 2016) was isolated as a WAK2 gene. The function of WAK2 for FHB resistance was validated through gene expression comparison between resistant and susceptible wheat lines, and resistance evaluation in three TILLING mutants for WAK protein function (Gadaleta et al., 2019). Another important locus, located on 2DL, was repeatedly identified from different sources of Chinese germplasm, including Wuhan 1 (Somers et al., 2003), CJ9306 (Jiang et al., 2007a, b), Wangshuibai, and CIMMYT line SYN1 (Zhu et al., 2016). This QTL is thought to be transcription factor TaWRKY70 that mediates expression of downstream metabolite biosynthetic genes TaACT, TaDGK, and TaGLI to condition resistance to Fusarium graminearum (Kage et al., 2017a, b). Hu et al. (2019) identified an expression QTL for gene Traes_2DL_179570792 overlapped with the 2DL QTL interval.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been used to dissect the genetic basis of complex economic traits in wheat, such as pre-harvest sprouting resistance (Lin et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2017) and grain yield (Sun et al., 2017; Liu J. et al., 2017; Sukumaran et al., 2015). However, very few GWAS on wheat have addressed FHB resistance. Kollers et al. (2013) conducted a GWAS on FHB response in European winter wheat using 732 microsatellite markers and found significant associations involving all wheat chromosomes except 6B. Arruda et al. (2016) found 10 SNP-trait associations on chromosomes 4A, 6A, 7A, 1D, 4D, and 7D and multiple SNPs associated with Fhb1 in US winter wheat, including severity, incidence, FHB index, and DON content. Wang et al. (2017) identified QTL on chromosomes 1B, 2B, 4B, 5A, 5B, and 6A in spring wheat lines developed in the Pacific Northwest and at CIMMYT. However, the genetic basis underlying FHB resistance in elite Chinese wheat has not been examined.

In the current study, we analyzed a panel of Chinese wheat cultivars and elite breeding lines including more than 50 widely grown cultivars using the wheat 90K arrays to: (1) study the phenotypic variance of FHB response in Chinese wheat germplasm, and (2) determine the genetic architecture of FHB resistance in the panel. The results should provide a better understanding of the genetic basis and diversity in FHB response of the Chinese cultivars, and facilitate the improvement of FHB resistance levels by stacking FHB resistance QTL using MAS.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

The WAPS comprised 240 geographically diverse bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivars and elite lines from China (Supplementary Table S1). Out of these, 229 entries were obtained from 12 provinces located in five agro-ecological zones (Zhuang, 2003; Li H. et al., 2019), including the Northern Winter Wheat Zone (Zone I), Yellow and Huai River Valleys Facultative Wheat Zone (Zone II), Middle and Lower Yangtze River Valleys Autumn-Sown Spring Wheat Zone (Zone III), Southwestern Autumn-Sown Spring Wheat Zone (Zone IV), and Northeastern Spring Wheat Zone (Zone VIII). The remaining 11 genotypes were introduced from CIMMYT, including seven lines from the 14th FHB Screening Nursery and an Australian cultivar Gamenya. More than 50 cultivars of this panel achieved peak annual planting areas of 1 × 105 hectares from 2000 to 2016, including the founder parents Jimai 22, Ningmai 9, Xiaoyan 6, and Zhoumai 18. Sumai 3 was used as an FHB resistant check, CJ9306 and Wuhan 1 as moderately resistant checks, and Gamenya as a susceptible check.

Inoculum Preparation

The inoculum comprised two highly aggressive isolates of F. graminearum, Huanggang 1 and Fg 5035, collected in Hubei Province. The isolate Huanggang 1 was kindly provided by the Institute of Plant Protection and Soil Science, Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and Fg 5035 was provided by Huazhong Agricultural University.

The F. graminearum was preserved on PDA (potato dextrose agar) medium at −20°C until use. The mycelium was inoculated into a 5% mung bean broth medium to grow F. graminearum conidia with shaking at 180 rpm under 28°C for 5–7 days. The flasks content was filtered and the concentration of conidia was examined with blood counting chamber under a microscope.

Phenotypic Assessment

A combination of type I and type II resistance was assessed in the field nurseries at Nanhu Experimental Station (altitude 27 m, latitude 30.48°N), Food Crops Institute, Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences, during the 2013–2014, 2014–2015, 2015–2016, and 2016–2017 cropping seasons, hereafter referred to as 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017, respectively. The average annual rainfall is about 1,270 mm at this location and the growing season extends from early November to May. The trials were carried out in randomized complete blocks with two replications. Each plot comprised 2 × 1 m rows with 25 cm space between rows.

In 2014, 2015, and 2016, an overhead misting system was applied to increase the humidity to favor pathogen infection and FHB development. The system included 1.5 m high micro-sprinklers spaced at distances of 1.5 × 1.5 m and operated automatically by a programmable timer from 9 am to 7 pm with 2 min of spraying per hour. Ten randomly selected flowering spikes per plot were labeled with blue tapes. About 30 mL of water suspension of F. graminearum conidia at a concentration of 50,000 spores/mL were sprayed on the labeled spikes, which were then assessed 21 days post-inoculation for FHB response by counting the number of diseased spikelets and total spikelets per spike. The FHB index (%) was calculated as (Severity × Incidence)/100 (Stack and McMullen, 1994), where incidence is the percentage of FHB infected spikes, and severity is the averaged percentage of symptomatic spikelets, e.g. a line with nine out of ten spikes infected (90% incidence), and 20% of symptomatic spikelets on average (20% severity), had an FHB index of 18% (90% × 20%) (He et al., 2013).

In 2017, the population was planted in a rice field with the same experimental design. Grain-spawn inoculation was conducted by scattering 600 g scabby wheat grains per 100 m2 on the soil surface about 1 month before anthesis, and FHB was visually scored 28 days post-anthesis.

The plant heights for all the accessions used in this study were recorded about 2 weeks after anthesis. For each plot, the plant heights were measured two times to calculate the average.

Genotyping and Quality Control

Genomic DNA for SNP assays was extracted from young leaf tissue for each accession using a modified CTAB procedure. The WAPS population was genotyped using the Illumina wheat 90K SNP arrays (Wang et al., 2014) at the USDA-ARS Small Grains Genotyping Laboratory in Fargo, ND, United States. SNPs were called using Illumina GenomeStudio Software. The accuracy of SNP clustering was validated manually. SNPs with less than 20% missing data and a MAF exceeding 5% were selected for subsequent analysis. Physical positions of the SNP markers were obtained from the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC1) database. The marker density was drawn using the CMplot package in R2. The flanking markers of 11 known FHB QTL (He et al., 2013) were used to genotype the WAPS population. Markers for 10 of them, Fhb1 (UMN 10), Fhb2 (Xwmc179), Qfhs.ifa-5A (Xbarc186 and Xbarc180), QTL on 3A from Frontana (Xdupw227), QTL on 5A from Frontana (Xbarc197 and Xgwm129), QTL on 2DL from Wuhan 1 (Xwmc245), QTL on 4BS from Wuhan 1 (Xwmc238 and Xgwm149), QFhs.nau-2DL (Xgwm157 and Xgwm539), Qfhs.ndsu-3AS (Xgwm2), and Qfhs.fcu-7AL (Xbarc121 and Xwmc488) were successfully applied. Diagnostic markers PFT-CAPS for Fhb1 candidate gene PFT and His-InDel for Fhb1 casual gene His (Zhu et al., 2018) were used to detect Fhb1 in this panel.

Statistical Analysis, Population Structure, and GWAS

Comparisons of the means of different groups were done using t-tests. For analysis of the FHB index, flowering time, and plant height, best linear unbiased estimates (BLUE) were calculated across the environments using the ANOVA function in IciMapping V4.0 software (Li et al., 2007).

Population structure analysis was performed using ADMIXTURE3. The Genomic Association and Prediction Integrated Tool (GAPIT) was used to generate distance-based clustering distribution and scree plots4.

Associations between genotypic and phenotypic data were analyzed using Tassel v5.05. The kinship (K)+PCA model was chosen to perform MLM analysis to control background variation and eliminate spurious MTAs. Markers with adjusted –log10 (P-value) ≥ 3.0 were considered significant markers for FHB resistance (Liu Y. et al., 2017). The P-value distributions of markers (observed P-values plotted against expected P-values) were shown in Q-Q plots. Manhattan and Q-Q plots were drawn using CMplot. To compare the physical positions of the QTL identified in the current study and the known genes/QTL, relevant markers and gene sequences were used to blast Chinese Spring reference genome sequences (IWGSC RefSeq v1.06).

Development of PCR-Based Markers for Significant SNPs

The SNPs significantly associated with FHB resistance were converted to KASP, CAPS or conventional PCR-based markers to facilitate their application in MAS. Primers for KASP markers were designed by PolyMarker7 and fluorescence signals were detected using the multifunctional microplate reader PHERAstarPlus (BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany) and analyzed using KlusterCaller software (LGC Genomics, Teddington, United Kingdom). The primers for other types of markers were designed based on chromosome-specific polymorphisms among homologous sequences in the target regions obtained from the EnsemblPlants database8. The PCR products were visually detected by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Results

Phenotypic Variation

Analysis of variance of FHB indices showed significant variation for years, genotypes, and genotype-by-year interaction (Table 1). Heritability of FHB indices across the 4 years was 0.63, indicating that the FHB response of the WAPS population was mainly controlled by genetic factors.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of variance of Fusarium head blight indices in the WAPS (Wheat Association Panel for Scab Research) population.

| Source of variation | Df | Mean square | F-value | P-value |

| Genotype | 239 | 2295.1 | 11.3 | <0.0001 |

| Year | 3 | 186007.8 | 914.1 | <0.0001 |

| Genotype × Year | 717 | 598.0 | 2.9 | <0.0001 |

| Replication/Year | 4 | 5610.1 | 27.6 | <0.0001 |

hb2 = 0.63.

Disease symptoms were moderate to high in the first 3 years under spray inoculation. The mean FHB indices of the WAPS population were 58.3, 49.2, and 69.3% in 2014, 2015, and 2016, respectively. The highest FHB index was recorded in 2016, probably due to warmer weather during inoculation and disease development. FHB symptom in 2017 was lighter than those in the earlier years, with a mean FHB index of 29.1%. This might be attributed to the grain-spawn inoculation method providing less pathogen pressure than spray inoculation. The variation in symptom levels might cause differences in the frequency distribution of the FHB index. The frequency distribution in the years 2016 and 2017 did not fit a normal curve (Supplementary Figure S1).

The correlation coefficients of FHB indices among the first 3 years ranged from 0.41 to 0.66, while those between 2017 and the earlier years were relatively lower with a range of 0.31–0.52 (Supplementary Table S2).

The BLUE values across 4 years for FHB indices exhibited wide variation ranging from 5.3 to 88.6% (Supplementary Figure S1). Sumai 3 had the best resistance with a BLUE value of FHB indices of 5.3%. The two moderately resistant checks, CJ9306 and Wuhan 1, were rated 21.3 and 27.4%, respectively, whereas the susceptible check Gamenya was 73.8% for the BLUE values of FHB indices across years. Genotypes from Jiangsu and Hubei had an average FHB index of 28.6%; followed by cultivars from Anhui and Gansu, with an index of 39.5 and 39.7%, respectively. Genotypes from Beijing (45.6%), Shaanxi (47.7%), and Sichuan (49.4%) had relatively high values, and those from Shanxi (50.4%), Shangdong (52.7%), Henan (57.3%), Ningxia (61.5%), and Hebei (62.5%) tended to be highly susceptible (Supplementary Figure S2). CIMMYT lines showed moderate resistance with an average FHB index of 39.5%.

Marker Distribution and Population Structure

Of 81,587 SNPs called in the assay, 22,922 were polymorphic in the population and selected for subsequent analysis. After removing SNPs with MAF <5 and >20% missing data, 19,803 were employed for GWAS. These SNP loci spanned a physical distance of 14,036.0 Mb, with an average density of 0.963 Mb per locus. SNP density for the D genome (1.781 Mb per SNP) was lower than those for the A (0.852 Mb per SNP) and B (0.785 Mb per SNP) genomes (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Figure S3).

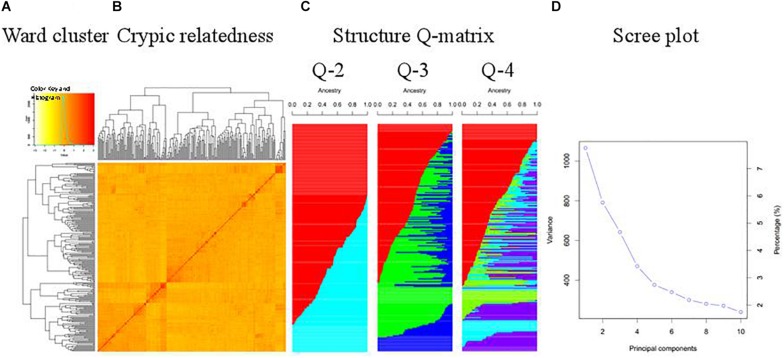

The WAPS population was divided into three subgroups, essentially consistent with geographic origin and pedigree (Figure 1). For example, Ningmai 16 and Zhenmai 6, both derived from Ningmai 9, clustered with Ningmai 9 in the same subgroup. Most of the wheat cultivars from Zone I, Zone II, Zone VIII, and CIMMYT were placed in subgroup I (marked in red in Q-3 in Figure 1C), most of the Zone IV cultivars in subgroup II (marked in green), and the majority of Zone III cultivars in subgroup III (marked in blue). There were exceptions – a significant portion of the genotypes from Zone II were allocated to subgroups II and III rather than subgroup I, indicative of germplasm exchange or the artificial nature of zoning. Weak kinship existed among cultivars in the WAPS population – the scree plot demonstrated that the first four PCs explained about 23% of the genetic variation in the panel (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Structure analysis of the WAPS population. (A) Ward clustering of the population; (B) Cryptic relatedness matrix based on genetic distance; (C) Matrices of membership coefficients corresponding to 2 to 4 hypothetical subpopulations; (D) Scree plot generated by GAPIT demonstrating genetic variance explained by each principal component.

Maker-Trait Association Analysis and Geographical Distribution of Favorable Alleles

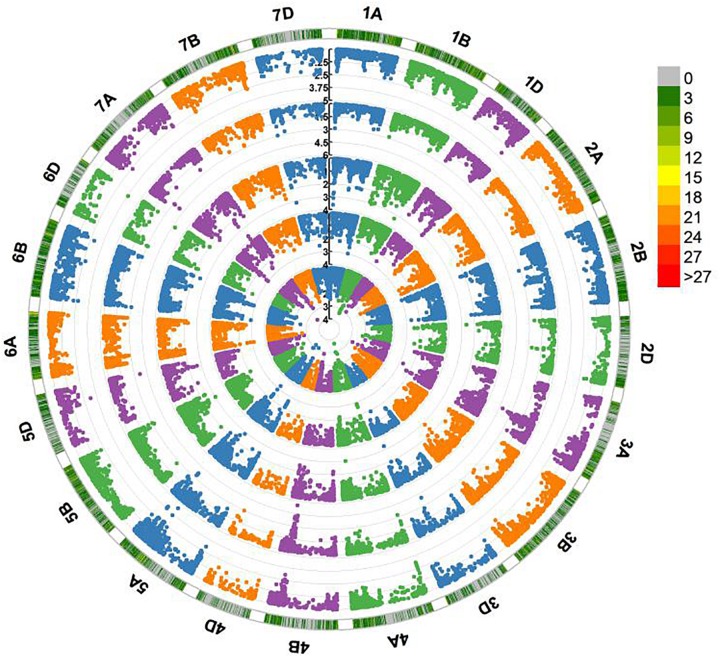

Five QTL on chromosome arms 1AS, 2DL, 5AS, 5AL, and 7DS, designated QFhb.hbaas-1AS, QFhb.hbaas-2DL, QFhb.hbaas-5AS, QFhb.hbaas-5AL, and QFhb.hbaas-7DS, respectively, were significant in at least two environments, explaining phenotypic variation ranging from 4.9 to 10.3% (Table 2, Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S4). Representative significant markers were IWB75039, Xgwm539, IWB21456, IWB42293, and IWB15569, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Loci significantly associated with FHB resistance in at least two environments identified in 240 wheat accessions using the MLM model in Tassel v5.0.

| Markera | Variantb | Chrc | Physical positiond (Mb) | Environment | P-value | R2e (%) | P-value for plant heightf | P-value for days to floweringf |

| IWB75039 | A/G | 1AS | 10.0 | 2016, 2017 | 3.12 E-04 | 5.6, 5.6 | 0.650 | 0.113 |

| Xgwm539 | Wuhan 1 allele/ others | 2DL | 513.1 | 2016, BLUE | 2.80 E-05 | 10.3, 7.5 | 0.258 | 0.062 |

| IWB21456 | A/G | 5AS | 9.6 | 2014, 2015, BLUE | 2.58 E-04 | 5.0, 5.0, 5.7 | 0.003 | 0.608 |

| IWB42293 | A/G | 5AL | 540.6 | 2015, BLUE | 4.68 E-04 | 4.9, 5.4 | 0.031 | 0.110 |

| IWB15569 | C/T | 7DS | 23.5 | 2016, 2017 | 4.34 E-04 | 4.9, 5.6 | 0.367 | 0.054 |

aRepresentative markers showing the strongest association with the resistance locus; bFavorable allele is underlined; cChr: Chromosome; dPhysical positions based on the Chinese Spring reference genome sequences from the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC, http://www.wheatgenome.org); ePercentage of phenotypic variance explained; fP-values for association between the representative markers of FHB QTL and plant height and flowering time in WAPS population calculated by Tassel v5.0 using the MLM model.

FIGURE 2.

Circle Manhattan plots revealing significant QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance in 240 wheat accessions performed by Tassel v5.0 using the MLM model. Traits plotted from inside to outside are FHB indices in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and the BLUE value across 4 years. The –log10 (P) values from a genome-wide scan are plotted against positions on each of the 21 chromosomes. Marker density along each chromosome is shown with different colors in the outermost circle. Numbers in the legend represent the number of SNPs within a 1 Mb window size.

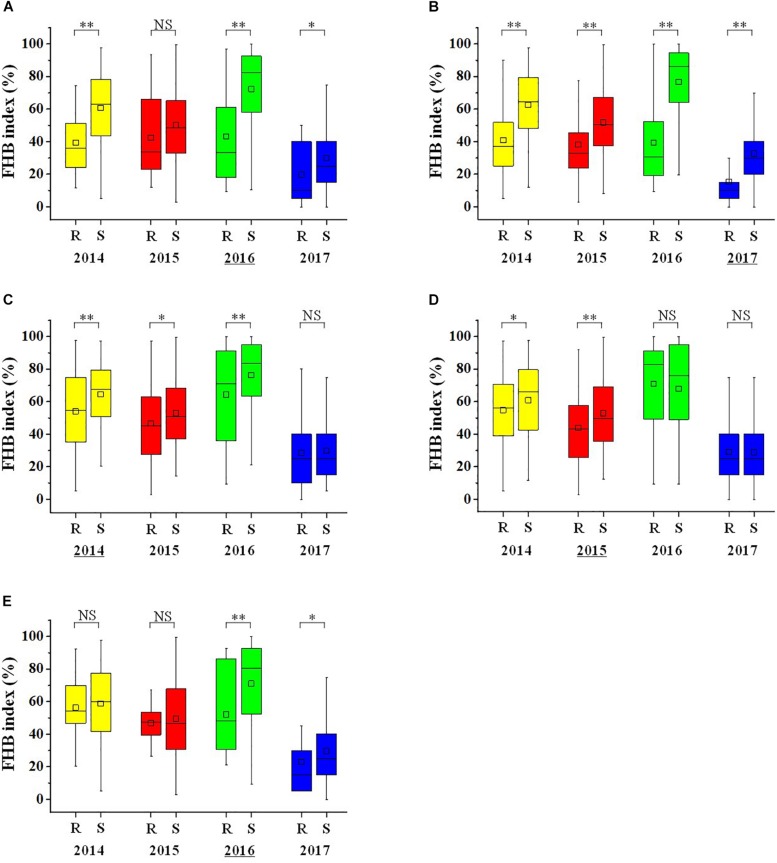

The mean FHB index of the lines with the favorable allele of QFhb.hbaas-1AS was 15.2–40.2% lower than those with the unfavorable allele over the 4 years. Differences were even higher for QFhb.hbaas-2DL (26.1–53.1%) (Figure 3). The other three QTL showed smaller effects. QFhb.hbaas-5AS and QFhb.hbaas-7DS reduced the FHB index by 4.3–16.2% and 4.1–26.6%, respectively, and QFhb.hbaas-5AL reduced the FHB index by 10.1% in 2014 and 17.1% in 2015 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Box plots visualizing differences in Fusarium head blight index between two groups of wheat accessions with contrasting resistance or susceptibility alleles for QTL on chromosomes 1AS (A), 2DL (B), 5AS (C), 5AL (D), and 7DS (E). The yellow, red, green and blue box plots represent 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017, respectively. The horizontal line within boxes represent the median, and black squares indicate means. ‘∗∗’, ‘∗’ and “NS,” P < 0.01, P < 0.05 and non-significant. “R” and “S” represent lines with the resistance and susceptibility alleles, respectively. The year with the highest FHB index difference between R and S for each QTL was underlined in the X-axis.

Of the 240 genotypes, 23, 48, 141, 98, and 18 possessed resistance alleles QFhb.hbaas-1AS, QFhb.hbaas-2DL, QFhb.hbaas-5AS, QFhb.hbaas-5AL, and QFhb.hbaas-7DS, respectively, based on marker analysis (Supplementary Figure S5). More than half of the lines carrying the QFhb.hbaas-1AS resistance allele were from Jiangsu and Hubei (Supplementary Figure S5a). The frequency was even higher for QFhb.hbaas-2DL: 36 carriers originated from Jiangsu or Hubei (Supplementary Figure S5b). Resistance alleles of the remaining three QTL QFhb.hbaas-5AS, QFhb.hbaas-5AL, and QFhb.hbaas-7DS presented at relatively high frequencies in the cultivars from Henan, Shandong, and Shaanxi in the Yellow and Huai River Valley region (Supplementary Figures S5c–e).

Six cultivars – Sumai 3, Ning 7840, Ningmai 9, Ningmai 13, Ningmai 16, and Zhenmai 5 – carried Fhb1 based on functional marker analysis of His-Indel (Supplementary Figure S6a). These cultivars were developed in Jiangsu (Middle and Lower Yangtze River Valleys, Zone III) where FHB has traditionally been more severe than other regions in China.

The P-value for association of a representative marker for QFhb.hbaas-5AS with plant height was 0.003 when calculated using the MLM model by Tassel software. This indicated that the FHB QTL was pleiotropic or closely linked with a gene for plant height (Table 2). The other four QTL showed no significant relationship with plant height. All five FHB QTL had no significant effect on flowering time.

PCR-Based Markers for QFhb.hbaas-1AS, QFhb.hbaas-5AS, and QFhb.hbaas-5AL

The SNPs (IWB75039, IWB21456, and IWB42293) associated with QFhb.hbaas-1AS, QFhb.hbaas-5AS, and QFhb.hbaas-5AL were converted to PCR-based markers and designated FHB-1AS-PCR, FHB-5AS-KASP, and FHB-5AL-CAPS, respectively. FHB-1AS-PCR produced no PCR products for the resistance allele, and a 389 bp fragment for the susceptibility allele (Supplementary Figure S6b). For FHB-5AS-KASP, red and blue dots represented the resistance and susceptibility alleles of QFhb.hbaas-5AS, respectively (Supplementary Figure S6c). The CAPS marker FHB-5AL-CAPS produced a 334 bp fragment for both resistance and susceptibility alleles. After digestion with restriction endonuclease AgeI (recognition sequence: 5′-A/CCGGT-3′), the products of cleaved fragments of 213 and 121 bp were obtained for the susceptibility allele, whereas the resistance allele was represented by the intact 334 bp fragment (Supplementary Figure S6d).

Primers for the three converted markers are listed in Table 3, and protocols for their use are described in Supplementary Table S4. For validation, the three markers were used to genotype 240 WAPS accessions with very low frequencies of inconsistency (3.3, 3.3 and 4.2% for each marker).

TABLE 3.

Primers for markers FHB-1AS-PCR, FHB-5AS-KASP, and FHB-5AL-CAPS.

| Marker | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

| FHB-1AS-PCR | P75039F | GTTTTCAGGGCCTTATCAACTGAAG |

| P75039R | GGTTCGGTTGGTGCTTAATCACT | |

| FHB-5AS-KASPa | P21456A | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTATCGACAATTACATCAAATGACTGA |

| P21456B | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTATCGACAATTACATCAAATGACTGG | |

| P21456C | AATAACGTGGCTATCAGTGGT | |

| FHB-5AL-CAPS | P42293F | GCCAGAGCACTGGTAATTACAGT |

| P42293R | CGATTCCGACCACCACGAG |

aTails for competitive primers are underlined.

Prediction of Candidate Genes

The annotations of the high confidential genes (IWGSC RefSeq annotation v1.0 see text footnote 1) less than 2 Mb away from the representative SNPs of QFhb.hbaas-1AS, QFhb.hbaas-5AS, QFhb.hbaas-5AL, and QFhb.hbaas-7DS were examined to determine their candidacy for FHB resistance. Bioinformatics analysis identified four genes encoding 12-oxophytodienoate reductase-like protein, six genes encoding RLK, and two genes corresponding to UGT near QFhb.hbaas-1AS (Supplementary Table S5). Two genes encoding pathogenesis-related (PR) protein 1 were considered as candidates for QFhb.hbaas-5AS. For QFhb.hbaas-5AL, two genes encoding glucan endo-1, 3-beta-glucosidase, one for defensin and one for RLK were identified. A gene encoding enhanced disease resistance 2-like protein might contribute to FHB resistance for QFhb.hbaas-7DS.

Discussion

FHB Resistance Variation

The WAPS population with the wheat accessions collected from different agro-ecological regions represents a large proportion of the genetic diversity in modern Chinese wheat cultivars. Thus, we can use mean FHB indices in the different regions to assess relative levels of FHB resistance across the regions. Cultivars from Jiangsu and Hubei, in the Middle and Lower Yangtze River Valleys, had the highest levels of FHB resistance, whereas cultivars from other provinces tended to be more susceptible, particularly those from Shandong, Henan, and Hebei in the Yellow and Huai River Valleys (Zone II) where almost one-half of the total Chinese wheat crop is produced.

This geographical differentiation for FHB resistance agrees with the prevalence of FHB. The Middle and Lower Yangtze River Valleys are the regularly hard-hit areas of FHB in China (Ma et al., 2020). The high disease pressure provides an appropriate environment for natural and artificial selection. Many FHB resistant or moderately resistant (MR) landraces were selected by local farmers, including Wangshuibai (in Jiangsu) and Chongyanghongmai (in Hubei) (Lu et al., 2001). The threat of FHB in this region also makes FHB resistance to be a priority of breeding objectives. Long-term breeding effort leads to the favorable alleles pyramiding and FHB resistance improvement. The rich resistant resources in this region, in turn, facilitate FHB resistance breeding. Indeed, Hubei and Jiangsu are the provinces where wheat clutivars showed the best FHB resistance according to the phenotypic results in the present study. FHB resistant germplasm from this region, such as Sumai 3 and Ning 7840 from Jiangsu, and Wuhan 1 from Hubei, was wildly used in global wheat breeding programs. For example, Sumai 3 is a major FHB resistant source for more than 20 modern wheat cultivars in the United States and Canada (Zhu et al., 2019; Hao et al., 2020). On the other hand, the high level of host resistance might be a driving force for the evolution of the pathogen. FHB resistant modern cultivars or elite lines identified from this region are valuable genetic resources in breeding for FHB resistance. Interestingly, many of these resistant cultivars could trace their resistance to Italian sources such as Mentana and Funo (Zhu et al., 2019), which might be due to different choices of breeders. To make good use of the resistance, molecular dissection of underlying QTL is urgent to be carried out.

Fusarium head blight was previously not a serious problem in the Yellow and Huai River Valleys but has increasingly become an important disease in recent years (Zhu et al., 2018). To improve FHB resistance levels, breeders here have started to use resistance sources from Jiangsu and Hubei, and local sources from Shaanxi, such as Xinong 2000, Xiaoyan 6, and Zhengmai 9023 (Zhu et al., 2019). Cultivars from Shaanxi generally have better FHB resistance than those from other provinces in the same agro-ecological zone, probably due to use of Sumai 3 and Th. ponticum as sources of FHB resistance in breeding (Xu et al., 1994; Zhu et al., 2019). However, the lack of consistent FHB development in breeding nurseries makes phenotypic selection difficult. More intensive selection approaches, such as dedicated FHB nurseries or molecular markers are essential for progress.

Possible Mechanisms of Detected QTL for FHB Resistance

The interaction between host and pathogen of FHB is complex. To date, only Fhb1 has been isolated, but its mechanism in FHB resistance remains unknown. Omics-based studies, along with targeted transgenic studies have shed insights into mechanisms involved in FHB resistance (Walter et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2020). Based on this knowledge, putative candidate genes were identified in the target QTL region. Genes encoding 12-oxophytodienoate reductase-like protein identified in the region of QFhb.hbaas-1AS may be involved in the biosynthesis or metabolism of signaling molecules oxylipin. Plant oxylipins such as JA could reduce F. graminearum growth and FHB symptoms (Qi et al., 2016). Genes encoding RLK, identified in the QFhb.hbaas-1AS and QFhb.hbaas-5AL regions, have been reported as DON and Fusarium-responsive and conferred type II resistance (Thapa et al., 2018). UGT could detoxify both DON and NIV produced by F. graminearum and enhance resistance to FHB in wheat and barley (Poppenberger et al., 2003; Li et al., 2017). The pathogenesis-related protein 1 (PR1) gene, identified in the QFhb.hbaas-5AS region, could increase type II resistance to FHB in wheat (Makandar et al., 2006). Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase is another PR protein PR2. Overexpression of PR2 gene in wheat led to an enhanced resistance to FHB (Mackintosh et al., 2007). Defensin and other cysteine-rich proteins in cereal target the fungal membrane through interactions with phospholipids and sphingolipids (Walter et al., 2010), responding to pathogen invasion. To further study the functions of these candidate genes in FHB resistance, resistant lines in the WAPS population could be selected to examine the expression of those identified genes.

Potential Use of QFhb.hbaas-2DL

The 2DL QTL was first mapped in the FHB moderately resistant line Wuhan 1 (Somers et al., 2003). Wangshuibai (Lin et al., 2006; Mardi et al., 2005) and CJ9306 (Jiang et al., 2007a, b) from Jiangsu, Sumai 3 derivatives DH 181 (Yang et al., 2005), SYN1, SHA3/CBRD (Lu et al., 2013) and Soru#1 (He et al., 2016) from CIMMYT, Swiss winter cultivar Arina (Paillard et al., 2004), and United States winter wheat line VA00W-38 (Liu et al., 2012) probably carry this QTL. Apparently, it has a relatively high frequency in the WAPS population. This QTL could be used as an important resistance source in combination with Fhb1 and other detected loci. SSR marker Xgwm539 can be used in MAS, but diagnostic PCR markers based on candidate genes TaWRKY70, TaACT, TaDGK and TaGLI (Kage et al., 2017a, b) would be more convenient for breeders.

QFhb.hbaas-1AS Is Independent of Flowering Time and Plant Height

QFhs.nau-1AS linked to SSR markers Xwmc24 and Xbarc148 was identified in Chinese wheat line CJ9306 (Jiang et al., 2007a, b). The physical positions of these markers (27.3 and 52.2 Mb) are similar to the significant marker IWB75039 (10.0 Mb) for QFhb.hbaas-1AS identified in this study. Both QTL probably represent the same resistance locus. Minor QTL on 1AS were also reported in susceptible cultivars Wheaton (Yu et al., 2008), Pirat (Holzapfel et al., 2008), and Pelikan (Häberle et al., 2010) but their relationships with QFhb.hbaas-1AS are unknown. QFhb.hbaas-1AS significantly reduced the FHB index in all years except 2015. This QTL was independent of flowering time and plant height, making it more flexible for use in breeding.

QFhb.hbaas-5AS, QFhb.hbaas-5AL, and QFhb.hbaas-7DS Might Be New Loci for FHB Resistance

A QTL on 5A designated Fhb5 was found in Wangshuibai, W14, and DH181 (Buerstmayr et al., 2009; Xue et al., 2011). The gene was flanked by markers Xgwm304 and Xgwm415 that span a physical interval between the physical positions of 105.4 Mb and 214.2 Mb, which is very close to the centromere of chromosome 5A (Ma et al., 2020). The physical position of the significant marker for QFhb.hbaas-5AS is at 9.6 Mb, indicating the difference of QFhb.hbaas-5AS from Fhb5. Recently, Steiner et al. (2019) finely mapped Qfhs.ifa-5A and separated it into two closely linked QTL Qfhs.ifa-5Ac (245.9–290.0 Mb) and Qfhs.ifa-5AS (70.7–119.9 Mb). Both distinguish from QFhb.hbaas-5AS mapped in the present study based on their physical positions.

Genes Vrn-A1 and Q on chromosome 5AL were associated with FHB response (He et al., 2016). These genes are located at 587.4 and 650.1 Mb, respectively, whereas QFhb.hbaas-5AL is at 540.6 Mb, about 110 and 46.8 Mb away from them. Three QTL were detected on chromosome 5A from wheat cultivars Pirat, Apache (Holzapfel et al., 2008), and Arina (Paillard et al., 2004), but mapped to the physical positions (659.1, 659.1, and 698.2 Mb) different from QFhb.hbaas-5AL. Thus, QFhb.hbaas-5AL is probably a new locus for FHB resistance.

Very few QTL for FHB resistance have been identified on chromosome 7D. Cativelli et al. (2013) mapped a major QTL linked to SSR marker Xcfd14 on 7DS in CIMMYT wheat cultivar Catbird, explaining 20% of the phenotypic variance. The physical position of Xcfd14 is 263.0 Mb, whereas QFhb.hbaas-7DS is located around 23.5 Mb. Steed et al. (2016) reported that the resistance gene Lr34/Yr18/Pm38 for multiple fungal pathogen might confer resistance to FHB. This gene is physically located at 47.4 Mb. It seems that QFhb.hbaas-7DS is different from the reported QTL/genes on this chromosome.

Validation of the putatively new QTL identified here will require analysis of bi-parental cross populations derived from representative genotypes in the WAPS population.

Status and Perspective of Fhb1 Exploitation in China

Sumai 3 was identified as the most FHB resistant cultivar in the present study. It has been used as a resistant parent in many crosses in China, but very few cultivars carry Fhb1 (Zhu et al., 2019), which is probably due to the linkage drag associated with Fhb1 in this donor. Apart from Sumai 3 and Ning 7840, only four cultivars, Ningmai 9 and its derivatives, in the present panel carry Fhb1. The four Fhb1 carriers have much better yield and quality than Sumai 3. Due to Sumai 3′s poor agronomic performance, we recommend using Ningmai 9 derivatives as alternative donors of Fhb1. A back-cross strategy with MAS in large segregating populations will be crucial for the successful introduction of this gene in the Yellow and Huai River Valleys (Zone II). For a long term, other important genes/QTL can be gradually introduced into new cultivars with Fhb1 through back-cross and MAS. Investigations of FHB resistance in indigenous accessions could also lead to the discovery of more sources of FHB resistance.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in EVA accession PRJEB36125.

Author Contributions

ZZ performed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. LC and WZha contributed to genotyping. LY, WZhu, JuL, YL, and HT participated in the field trials. LF, JiL, and AR participated in marker development and the data analysis. CG, YH, XX, and ZH designed the experiment and assisted in writing the manuscript. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. R. A. McIntosh, Plant Breeding Institute, University of Sydney, and Dr. Xiwen Cai, Department of Plant Sciences, North Dakota State University for critically reviewing the manuscript. We also thank Drs. Chengdao Li, Yucai Liao, and Jianbing Yan for advice on experimental design, and Dr. David Bonnett for providing CIMMYT germplasm.

Abbreviations

- 15-AcDON

15-O-acetyl-DON

- 3-AcDON

3-O-acetyl-DON

- AE

anther extrusion

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BLUE

best linear unbiased estimation

- CAPS

cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences

- CIMMYT

International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center

- DON

deoxynivalenol

- DON-3-G

deoxynivalenol-3-glucoside

- FHB

Fusarium head blight

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- His or TaHRC

histidine-rich calcium-binding

- JA

jasmonic acid

- KASP

kompetitive allele specific PCR

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- MAS

marker-assisted selection

- MTA

marker-trait association

- NIV

nivalenol

- PFT

pore-forming toxin-like

- PVE

phenotypic variation explained

- QTL

quantitative trait loci

- RLK

receptor-like kinase

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- UGT

UDP-glycosyltransferase

- WAK

wall-associated receptor-like kinase

- WAPS

Wheat Association Panel for Scab Research.

Funding. This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101802 and 2016YFE0108600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31301306), Technology Innovation Program of Hubei Province (2016AHB022), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-03), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2014CFB316).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00206/full#supplementary-material

References

- Arruda M. P., Brown P., Brown-Guedira G., Krill A. M., Thurber C., Merrill K., et al. (2016). Genome-wide association mapping of Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat using genotyping-by-sequencing. Plant Genome 9 1–14. 10.3835/plantgenome2015.04.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Shaner G. (1994). Scab of wheat: prospects for control. Plant Dis. 78 760–766. 10.1094/PD-78-0760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Su Z., Cai J. (2018). Wheat resistance to Fusarium head blight. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 40 336–346. 10.1080/07060661.2018.1476411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buerstmayr H., Ban T., Anderson J. A. (2009). QTL mapping and marker-assisted selection for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat: a review. Plant Breed. 128 1–26. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2008.01550.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buerstmayr M., Steiner B., Buerstmayr H. (2019). Breeding for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat — Progress and challenges. Plant Breed. 10.1111/pbr.12797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cativelli M., Lewis S., Appendino M. L. (2013). A Fusarium head blight resistance quantitative trait locus on chromosome 7D of the spring wheat cultivar Catbird. Crop Sci. 53 1464–1471. 10.2135/cropsci2012.07.0435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter J. E., Clear R. M., Preston K. R. (1996). Fusarium head blight: effect on the milling and baking of some Canadian wheats. Cereal Chem. 73 695–701. 10.1021/bp960078c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter J. E., Marchylo B. A., Clear R. M., Clarke J. M. (1997). Effect of Fusarium head blight on semolina milling and pasta-making quality of durum wheat. Cereal Chem. 74 519–525. 10.1094/CCHEM.1997.74.5.519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foroud N. A., Baines D., Gagkaeva T. Y., Thakor N., Badea A., Steiner B., et al. (2019). Trichothecenes in cereal grains — an update. Toxins 11:634. 10.3390/toxins11110634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadaleta A., Colasuonno P., Giove S. L., Blanco A., Giancaspro A. (2019). Map-based cloning of QFhb.mgb-2A identifies a WAK2 gene responsible for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Sci. Rep. 9:6929. 10.1038/s41598-019-43334-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancaspro A., Giove S. L., Zito D., Blanco A., Gadaleta A. (2016). Mapping QTLs for Fusarium head blight resistance in an interspecific wheat population. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1381. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häberle J., Schweizer G., Schondelmaier J., Zimmermann G., Hartl L. (2010). Mapping of QTL for resistance against Fusarium head blight in the winter wheat population Pelikan//Bussard/Ning8026. Plant Breed. 128 27–35. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2008.01540.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Rasheed A., Zhu Z., Wulff B. B. H., He Z. (2020). Harnessing wheat Fhb1 for Fusarium resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 25 1–3. 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. Y., Lillemo M., Shi J., Wu J., Bjørnstad Å, Belova T., et al. (2016). QTL characterization of Fusarium head blight resistance in CIMMYT bread wheat line Soru#1. PLoS One 11:e0158052. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. Y., Singh P. K., Duveiller E., Schlang N., Dreisigacker S., Singh R. P. (2013). Identification and characterization of International Fusarium head blight screening Nurseries of wheat at CIMMYT, Mexico. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 136 123–134. 10.1007/s10658-012-0146-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holzapfel J., Voss H., Miedaner T., Korzun V., Häberle J., Schweizer G., et al. (2008). Inheritance of resistance to Fusarium head blight in three European winter wheat populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 117 1119–1128. 10.1007/s00122-008-0850-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Rocheleau H., McCartney C., Biselli C., Bagnaresi P., Balcerzak M., et al. (2019). Identification and mapping of expressed genes associated with the 2DL QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance in the wheat line Wuhan 1. BMC Genet. 20:47. 10.1186/s12863-019-0748-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Zhou J., Xue S., Li G., Yan H., Ran C., et al. (2018). A journey to understand wheat Fusarium head blight resistance in the Chinese wheat landrace Wangshuibai. Crop J. 6 48–59. 10.1016/j.cj.2017.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G., Dong Y., Shi J., Ward R. W. (2007a). QTL analysis of resistance to Fusarium head blight in the novel wheat germplasm CJ9306. II. Resistance to deoxynivalenol accumulation and grain yield loss. Theor. Appl. Genet. 115 1043–1052. 10.1007/s00122-007-0630-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G., Shi J., Ward R. W. (2007b). QTL analysis of resistance to Fusarium head blight in the novel wheat germplasm CJ9306. I. Resistance to fungal spread. Theor. Appl. Genet. 116 3–13. 10.1007/s00122-007-0641-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kage U., Karre S., Kushalappa A. C., McCartney C. (2017a). Identification and characterization of a Fusarium head blight resistance gene TaACT in wheat QTL-2DL. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15 447–457. 10.1111/pbi.12641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kage U., Yogendra K. N., Kushalappa A. C. (2017b). TaWRKY70 transcription factor in wheat QTL-2DL regulates downstream metabolite biosynthetic genes to resist Fusarium graminearum infection spread within spike. Sci. Rep. 7:42596. 10.1038/srep42596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollers S., Rodemann B., Ling J., Korzun V., Ebmeyer E., Argillier O., et al. (2013). Whole genome association mapping of Fusarium head blight resistance in European winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS One 8:e57500. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagudah E. S., Krattinger S. G. (2019). A new player contributing to durable Fusarium resistance. Nat. Genet. 51 1070–1071. 10.1038/s41588-019-0454-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Zhou J., Jia H., Gao Z., Fan M., Luo Y., et al. (2019). Mutation of a histidine-rich calcium-binding-protein gene in wheat confers resistance to Fusarium head blight. Nat. Genet. 51 1106–1112. 10.1038/s41588-019-0426-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Ye G., Wang J. (2007). A modified algorithm for the improvement of composite interval mapping. Genetics 175 361–374. 10.1534/genetics.106.066811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhou Y., Xin W., Wei Y., Zhang J., Guo L. (2019). Wheat breeding in northern China: achievements and technical advances. Crop J. 7 718–729. 10.1016/j.cj.2019.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Michlmayr H., Schweiger W., Malachova A., Shin S., Huang Y., et al. (2017). A barley UDP-glucosyltransferase inactivates nivalenol and provides Fusarium head blight resistance in transgenic wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 68 2187–2197. 10.1093/jxb/erx109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F., Xue S. L., Zhang Z. Z., Zhang C. Q., Kong Z. X., Yao G. Q., et al. (2006). Mapping QTL associated with resistance to Fusarium head blight in the Nanda 2419 × Wangshuibai population. II: type I resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112 528–535. 10.1007/s00122-004-1772-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Zhang D., Liu S., Zhang G., Yu J., Fritz A. K., et al. (2016). Genome-wide association analysis on pre-harvest sprouting resistance and grain color in U.S. winter wheat. BMC Genomics 17:794. 10.1186/s12864-016-3148-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Hall M. D., Griffey C. A., McKendry A. L. (2009). Meta-analysis of QTL associated with Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Crop Sci. 49 1955–1968. 10.2135/cropsci2009.03.0115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., He Z., Rasheed A., Wen W., Yan J., Zhang P., et al. (2017). Genome-wide association mapping of black point reaction in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 17:220. 10.1186/s12870-017-1167-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. Y., Christopher M. D., Griffey C. A., Hall M. D., Gundrum P. G., Brooks W. S. (2012). Molecular characterization of resistance to Fusarium head blight in U.S. soft red winter wheat breeding line VA00W-38. Crop Sci. 52 2283–2292. 10.2135/cropsci2012.03.0144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Lin Y., Gao S., Li Z., Ma J., Deng M., et al. (2017). A genome-wide association study of 23 agronomic traits in Chinese wheat landraces. Plant J. 91 861–873. 10.1111/tpj.13614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q., Lillemo M., Skinnes H., He X., Shi J., Ji F., et al. (2013). Anther extrusion and plant height are associated with Type I resistance to Fusarium head blight in bread wheat line ‘Shanghai-3/Catbird’. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126 317–334. 10.1007/s00122-012-1981-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W., Cheng S., Wang Y. (2001). Wheat Fusarium Head Blight Research. Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Xie Q., Li G., Jia H., Zhou J., Kong Z., et al. (2020). Germplasms, genetics and genomics for better control of disastrous wheat Fusarium head blight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 10.1007/s00122-019-03525-8 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z. H., Yin Y. N., Chen Y. (2016). “The epidemic characteristics of wheat Fusarium head blight and the progress of its control technology development,” in Plant Protection Technology Innovation and Agricultural Targeted Poverty Alleviation — Proc. 2016 Annu. Conf., China Plant Protection Society, ed. Chen W. Q. (Beijing: China Agricultural Science and Technology Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh C. A., Lewis J., Radmer L. E., Shin S., Heinen S. J., Smith L. A., et al. (2007). Overexpression of defense response genes in transgenic wheat enhances resistance to Fusarium head blight. Plant Cell Rep. 26 479–488. 10.1007/s00299-006-0265-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makandar R., Essig J. S., Schapaugh M. A., Trick H. N., Shah J. (2006). Genetically engineered resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat by expression of Arabidopsis NPR1. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19 123–129. 10.1094/MPMI-19-0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardi M., Buerstmayr H., Ghareyazie B., Lemmens M., Mohammadi S. A., Nolz R., et al. (2005). QTL analysis of resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat using a ‘Wangshuibai’-derived population. Plant Breed. 124 329–333. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2005.01103.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen M., Jones R., Gallenberg D. (1997). Scab of wheat and barley: a re-emerging disease of devastating impact. Plant Dis. 81 1340–1348. 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.12.1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillard S., Schnurbusch T., Tiwari R., Messmer M., Winzeler M., Keller B., et al. (2004). QTL analysis of resistance to Fusarium head blight in Swiss winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 109 323–332. 10.1007/s00122-004-1628-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppenberger B., Berthiller F., Lucyshyn D., Sieberer T., Schuhmacher R., Krska R., et al. (2003). Detoxifcation of the Fusarium mycotoxin deoxynivalenol by a UDP-glucosyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 278 47905–47914. 10.1074/jbc.M307552200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi P., Balcerzak M., Rocheleau H., Leung W., Wei Y., Zheng Y., et al. (2016). Jasmonic acid and abscisic acid play important roles in host–pathogen interaction between Fusarium graminearum and wheat during the early stages of Fusarium head blight. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 93 39–48. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2015.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat N., Pumphrey M. O., Liu S., Zhang X., Tiwari V. K., Ando K., et al. (2016). Wheat Fhb1 encodes a chimeric lectin with agglutinin domains and a pore-forming toxin-like domain conferring resistance to Fusarium head blight. Nat. Genet. 2016 1576–1580. 10.1038/ng.3706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers D. J., Fedak G., Savard M. (2003). Molecular mapping of novel genes controlling Fusarium head blight resistance and deoxynivalenol accumulation in spring wheat. Genome 46 555–564. 10.1139/g03-033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack R. W., McMullen M. P. (1994). A Visual Scale to Estimate Severity of Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat. Fargo, ND: North Dakota State University Extension Service. [Google Scholar]

- Steed A., Burt C., Lateef D., Clarke M., Nicholson P. (2016). “The durable race non-specific wheat resistance gene Lr34 confers increased resistance to Fusarium head blight (FHB),” in Proceedings of the 5th International Symp. on Fusarium Head Blight (ISFHB), Florianópolis. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner B., Buerstmayr M., Wagner C., Danler A., Eshonkulov B., Ehn M., et al. (2019). Fine-mapping of the Fusarium head blight resistance QTL Qfhs.ifa-5A identifies two resistance QTL associated with anther extrusion. Theor. Appl. Genet. 132 2039–2053. 10.1007/s00122-019-03336-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z., Bernardo A., Tian B., Chen H., Wang S., Ma H., et al. (2019). A deletion mutation in TaHRC confers Fhb1 resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat. Nat. Genet. 51 1099–1105. 10.1038/s41588-019-0425-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z., Jin S., Zhang D., Bai G. (2018). Development and validation of diagnostic markers for Fhb1 region, a major QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131 2371–2380. 10.1007/s00122-018-3159-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran S., Dreisigacker S., Lopes M., Chavez P., Reynolds M. P. (2015). Genome-wide association study for grain yield and related traits in an elite spring wheat population grown in temperate irrigated environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128 353–363. 10.1007/s00122-014-2435-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Zhang F., Yan X., Zhang X., Dong Z., Cui D., et al. (2017). Genome-wide association study for 13 agronomic traits reveals distribution of superior alleles in bread wheat from the Yellow and Huai River Valley of China. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15 953–969. 10.1111/pbi.12690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa G., Gunupuru L. R., Hehir J. G., Kahla A., Mullins E., Doohan F. M. (2018). A pathogen-responsive leucine rich receptor like kinase contributes to Fusarium resistance in cereals. Front. Plant Sci. 9:867. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter S., Nicholson P., Doohan F. M. (2010). Action and reaction of host and pathogen during Fusarium head blight disease. New Phytol. 185 54–66. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Chen J., Anderson J. A., Zhang J., Zhao W., Wheeler J., et al. (2017). Genome-wide association mapping of Fusarium head blight resistance in spring wheat lines developed in the Pacific Northwest and CIMMYT. Phytopathology 107 1486–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. C., Wong D., Forrest K., Allen A., Chao S., Huang B. E., et al. (2014). Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12 787–796. 10.1111/pbi.12183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Han X., Li F. (2019). Co-occurrence of multi-mycotoxins in wheat grains harvested in Anhui province, China. Food Control 96 180–185. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Hu L., He J. (1994). Practice and discussion in wheat FHB resistance improvement. J. Triticeae Crops 5 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Xue S., Xu F., Tang M., Zhou Y., Li G., An X., et al. (2011). Precise mapping Fhb5, a major QTL conditioning resistance to Fusarium infection in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 123 1055–1063. 10.1007/s00122-011-1647-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Gilbert J., Fedak G., Somers D. (2005). Genetic characterization of QTL associated with resistance to Fusarium head blight in a doubled-haploid spring wheat population. Genome 48 187–196. 10.1139/g04-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. B., Bai G. H., Zhou W. C., Dong Y. H., Kolb F. L. (2008). Quantitative trait loci for Fusarium head blight resistance in a recombinant inbred population of Wangshuibai/Wheaton. Phytopathology 98 87–94. 10.1094/phyto-98-1-0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Tang H., Cheng M. P., Dankwa K. O., Chen Z. X., Li Z. Y., et al. (2017). Genome-wide association study for pre-harvest sprouting resistance in a large germplasm collection of Chinese wheat landraces. Front. Plant Sci. 8:401. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Bonnett D., Ellis M., He X., Heslot N., Dreisigacker S., et al. (2016). Characterization of Fusarium head blight resistance in a CIMMYT synthetic-derived bread wheat line. Euphytica 208 367–375. 10.1007/s10681-015-1612-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Hao Y., Mergoum M., Bai G., Humphreys G., Cloutier S., et al. (2019). Breeding wheat for resistance to Fusarium head blight in the Global North: China, USA and Canada. Crop J. 7 730–738. 10.1016/j.cj.2019.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Xu D., Cheng S., Gao C., Xia X., Hao Y., et al. (2018). Characterization of Fusarium head blight resistance gene Fhb1 and its putative ancestor in Chinese wheat germplasm. Acta Agron. Sin. 44 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Q. S. (2003). Chinese Wheat Improvement and Pedigree Analysis. Beijing: China Agriculture Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in EVA accession PRJEB36125.