See Clinical Research on Page 278

In this issue of Kidney International Reports, Freedman and colleagues1 describe the design and rationale of the APOL1 Long-term Kidney Transplantation Outcomes Network (APOLLO). The discovery of genetic variants in APOL1, encoding apolipoprotein L1, reported in 2010, has had a revolutionary effect on our understanding of kidney disease (particularly glomerular diseases) occurring among peoples with recent sub-Saharan ancestry.2,3 As we approach the 10-year anniversary in 2020 of this seminal discovery in glomerular pathophysiology, there is considerable optimism that rapidly appearing new knowledge about these genetic variants and their effects on intracellular pathways will enable targeted therapy, and this in turn will provide a rationale for widespread genetic testing in the context of kidney disease, in patients and perhaps those at increased risk for kidney disease.

To date, there has not been a compelling rationale for APOL1 genetic testing individuals at risk for kidney disease or in those with kidney disease, as it is not clear that the genetic information would make a difference in clinical outcomes. For example, we have no evidence that screening for albuminuria or decreased renal function and early institution of effective therapy will improve clinical outcomes in APOL1 kidney diseases, although future studies may show that this is the case. Current therapies for progressive kidney disease appear to be less effective at slowing progressive loss of kidney function in APOL1 high-risk subjects compared with APOL1 low-risk subjects. This has been shown for glucocorticoids in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis4 and for anti-hypertensive therapy and a lower blood pressure target in arterionephrosclerosis in the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) trial.5 Nevertheless, these studies lacked an untreated control group, and it is likely that these therapies have some benefit in APOL1 high-risk individuals. Interestingly, in a meta-analysis of 4 hypertension trials, subjects with 1 or 2 APOL1 risk alleles and mild to moderate hypertension had a greater fall in systolic blood pressure with candesartan (12 vs. 8 mg Hg) and a greater decline in albuminuria (8 vs. 4 mg/d), compared with those with zero APOL1 risk alleles, whereas there were no differences by genotype for thiazides or beta blockers.6 Candesartan is a high-potency angiotensin receptor blocker with a long duration of action. It is more effective at blood pressure lowering than losartan and comparable to telmisartan and valsartan.S1 Whether the effect observed in APOL1 risk allele carriers is a class effect that extends to other high-potency angiotensin receptor blockers remains unknown, Finally, in APOL1-associated HIV-associated kidney disease, effective antiviral therapy resulting in viral suppression slows but does not halt progressive loss of renal function.7

It appears that current therapies do not effectively or sufficiently target the multiple cellular pathways implicated in APOL1 nephropathies, but the institution of a high-potency angiotensin receptor blocker (particularly candesartan) may be preferred. This limited armamentarium may be expanded soon. Therapies that target the mRNA products or protein products of the variant alleles are being developed and are in preclinical and early-stage clinical studies. Thus, APOL1 antisense RNA reduces proteinuria in interferon-stimulated APOL1 transgenic mice,8 and other therapies are being investigated to modulate various cellular pathways by which APOL1 variants alter kidney cell (particularly podocyte) function.

APOL1 genetic variants have the potential to impact renal transplantation in 2 ways. First, recipients of APOL1 high-risk kidneys (defined as carriage of 2 APOL1 risk alleles) may have worse outcomes, with shorter allograft survival duration. Second, living donors with APOL1 high-risk status may have a higher risk for kidney disease arising following kidney donation. Doshi and colleagues9 examined post-donation renal function among 136 African American live kidney donors, including 19 (14%) with high-risk APOL1 genotypes and 119 (86%) with low-risk APOL1 genotypes. At baseline before kidney donation, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) among APOL1 low-risk individuals was 108 ± 20 versus 98 ± 17 ml/min per 1.73 among APOL1 high-risk individuals (P = 0.04). After a median of 15 years following kidney donation, eGFR was 67 ± 15 and 57 ± 18 ml/min per 1.73, respectively (P = 0.02). Decline in eGFR was faster in APOL1 high-risk individuals. Two donors, both with APOL1 high-risk genotypes, developed end-stage kidney disease. When subjects were divided into low-risk and high-risk groups, matched for demographic and clinical characteristics, eGFR decline rates were similar between the 2 APOL1 status groups, suggesting that on average, the process of donation may equally stress kidneys of both APOL1 high-risk and low-risk individuals. The worse outcomes in APOL1 high-risk subjects may due to pre-donation pathophysiology, which is only partly identified by slightly lower eGFR at the time of donation, as eGFR does not provide information about the degree of renal compensation; this is particularly true early in the process of renal compensation for reduced renal mass, when eGFR may be normal.

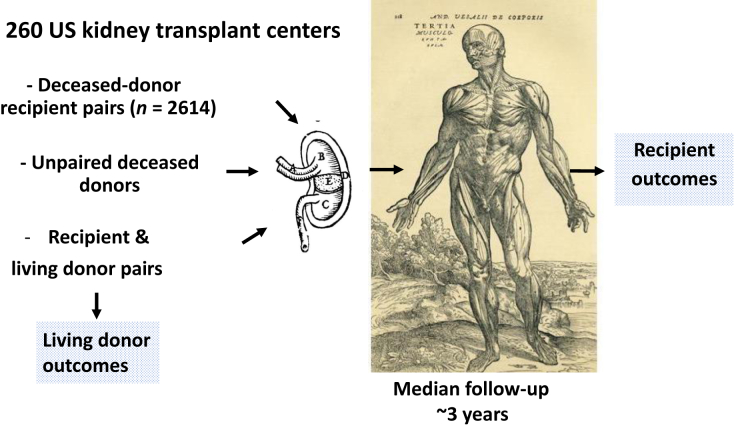

The APOLLO study is an ambitious undertaking with a relatively short timeline. It will involve 260 transplant centers, 58 organ procurement organizations, and 68 histocompatibility laboratories across the United States (Figure 1). Nearly all transplant centers in the United States will participate, with the exception of some centers that provide kidney transplants to fewer than 10 patients per year. The study will include both adults and children (7 to 17 years of age), with the intention to evaluate the outcomes of 2614 deceased-donor recipient pairs, as well as some living kidney donor-recipient pairs and some unpaired deceased-donor kidneys. Kidney donors will provide consent and must have African American ancestry, as reported by the subject or by family members. In the case of deceased donors, lack of family consent will be an exclusion. The study is powered for the primary outcome of death-censored allograft survival. The first patient was enrolled in May 2019, and subject follow-up is now projected to end in 2022.

Figure 1.

The 260 US transplant centers that are participating in the APOLLO study anticipate studying 2614 deceased-donor pairs (consisting of recipients and deceased donors) and additional numbers of unpaired deceased donors, as well as living donor and recipient pairs. Subjects will be studied at a median of 3 years after kidney transplantation, to evaluate renal outcomes among living donors and all recipients. Images are taken from woodcuts in De human corporis fabrica libri septum (1567, Basel, Switzerland) by Andries van Wesel (also known as Andreas Vesalius), the Flemish (Belgian) physician whose work on dissection of human cadavers and systematic and realistic textbooks revolutionized the field of anatomy.

The APOLLO study will provide more information about several crucial issues that relate to APOL1 variants and kidney transplantation. Are African American individuals who have 2 APOL1 risk alleles and who wish to be living kidney donors at increased risk for kidney disease and kidney failure following transplantation? If so, what is the magnitude of these risks? How do APOL1 risk alleles affect donor outcomes? The study will be the first to address these important issues in a prospective fashion and will do so with an ambitious attempt to achieve suitable sample size to reach convincing conclusions. The primary hypothesis of this observational study is that donor kidneys obtained from individuals with high APOL1 risk variant status (defined as carriage of 2 risk variants), either living or deceased, will be associated with shorter death-censored allograft survival. Other objectives will include evaluating recipient kidney function and proteinuria, evaluating donor kidney function, and evaluating other factors that might modify the postulated risks to recipients of APOL1 high-risk kidneys.

Apollo was the Greek god of medicine and archery, and of poetry and music. The Apollo spacecraft took humankind to the moon, leaving the Earth behind for the first time. Both are fitting symbols of our aspirations to ultimately achieve targeted therapy for APOL1 disorders. Such therapy approaches may in the long-term more effectively treat APOL1 renal diseases and reduce the need for long-term dialysis and kidney transplantation in individuals genetically susceptible to kidney disease. The leaders of this effort and of the funding agency are to be congratulated for initiating this complex study, designed to answer important clinical questions relating to the safety of kidney transplants.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. We thank Dr. Alison Grazioli for editorial review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary References.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Freedman B.I., Moxey-Mims M.M., Alexander A.A. APOL1 Long-term Kidney Transplantation Outcomes Network (APOLLO): design and rationale. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genovese G., Friedman D.J., Ross M.D. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzur S., Rosset S., Shemer R. Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene. Hum Genet. 2010;128:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0861-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopp J.B., Nelson G.W., Sampath K. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2129–2137. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipkowitz M.S., Freedman B.I., Langefeld C.D. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2013;83:114–120. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham P.N., Wang Z., Grove M.L. Hypertensive APOL1 risk allele carriers demonstrate greater blood pressure reduction with angiotensin receptor blockade compared to low risk carriers. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estrella M.M., Li M., Tin A. The association between APOL1 risk alleles and longitudinal kidney function differs by HIV viral suppression status. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:646–652. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aghajan M., Booten S.L., Althage M. Antisense oligonucleotide treatment ameliorates IFN-gamma-induced proteinuria in APOL1-transgenic mice. JCI Insight. 2019;4:126124. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.126124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doshi M.D., Ortigosa-Goggins M., Garg A.X. APOL1 genotype and renal function of black living donors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:1309–1316. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017060658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.