Abstract

Background

Long‐acting depot injections of drugs such as flupenthixol decanoate are extensively used as a means of long‐term maintenance treatment for schizophrenia.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of flupenthixol decanoate in comparison with placebo, oral antipsychotics and other depot neuroleptic preparations for people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses, in terms of clinical, social and economic outcomes.

Search methods

We identified relevant trials by searching the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register in March 2009 and then for this update version, a search was run in April 2013. The register is based on regular searches of CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO. References of all identified studies were inspected for further trials. We contacted relevant pharmaceutical companies, drug approval agencies and authors of trials for additional information.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials that focused on people with schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders where flupenthixol decanoate had been compared with placebo or other antipsychotic drugs were included. All clinically relevant outcomes were sought.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors independently selected studies, assessed trial quality and extracted data. For dichotomous data we estimated risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model. Analysis was by intention‐to‐treat. We summated normal continuous data using mean difference (MD), and 95% CIs using a fixed‐effect model. We presented scale data only for those tools that had attained prespecified levels of quality. Using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) we created 'Summary of findings tables and assessed risk of bias for included studies.

Main results

The review currently includes 15 randomised controlled trials with 626 participants. No trials compared flupenthixol decanoate with placebo.

One small study compared flupenthixol decanoate with an oral antipsychotic (penfluridol). Only two outcomes were reported with this single study, and it demonstrated no clear differences between the two preparations as regards leaving the study early (n = 60, 1 RCT, RR 3.00, CI 0.33 to 27.23,very low quality evidence) and requiring anticholinergic medication (1 RCT, n = 60, RR 1.19, CI 0.77 to 1.83, very low quality evidence).

Ten studies in total compared flupenthixol decanoate with other depot preparations, though not all studies reported on all outcomes of interest. There were no significant differences between depots for outcomes such as relapse at medium term (n = 221, 5 RCTs, RR 1.30, CI 0.87 to 1.93, low quality evidence), and no clinical improvement at short term (n = 36, 1 RCT, RR 0.67, CI 0.36 to 1.23, low quality evidence). There was no difference in numbers of participants leaving the study early at short/medium term (n = 161, 4 RCTs, RR 1.23, CI 0.76 to 1.99, low quality evidence) nor with numbers of people requiring anticholinergic medication at short/medium term (n = 102, 3 RCTs, RR 1.38, CI 0.75 to 2.25, low quality evidence).

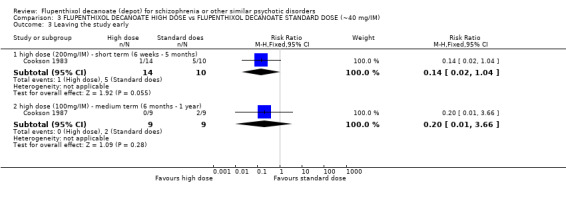

Three studies in total compared high doses (100 to 200 mg) of flupenthixol decanoate with the standard doses (˜40mg) per injection. Two trials found relapse at medium term (n = 18, 1 RCT, RR 1.00, CI 0.27 to 3.69, low quality evidence) to be similar between the groups. However people receiving a high dose had slightly more favourable medium term mental state results on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (n = 18, 1 RCT, MD ‐10.44, CI ‐18.70 to ‐2.18, low quality evidence). There was also no significant difference in the use of anticholinergic medications to deal with side effects at short term (2 RCTs n = 47, RR 1.12, CI 0.83 to 1.52 very low quality evidence). One trial comparing a very low dose of flupenthixol decanoate (˜6 mg) with a low dose (˜9 mg) per injection reported no difference in relapse rates (n = 59, 1 RCT, RR 0.34, CI 0.10 to 1.15, low quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

In the current state of evidence, there is nothing to choose between flupenthixol decanoate and other depot antipsychotics. From the data reported in clinical trials, it would be understandable to offer standard dose rather than the high dose depot flupenthixol as there is no difference in relapse. However, data reported are of low or very low quality and this review highlights the need for large, well‐designed and reported randomised clinical trials to address the effects of flupenthixol decanoate.

Plain language summary

Depot flupenthixol decanoate for schizophrenia or other similar mental illnesses

Schizophrenia is a severe mental illness that affects thinking and perception. It often develops in early adult‐hood and can have a lifelong impact on not only the mental well‐being of the sufferer, but their social and general functioning. Worldwide around 15 people per 100,000 are diagnosed with schizophrenia every year. The mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic drugs.

Antipsychotics are usually given as tablets by mouth (orally). However, people with mental illness often have difficulties with accepting medication (compliance). Their illness affects their thinking, which can erode their understanding of their illness and they often do not see the need for treatment. Taking antipsychotics can also have unpleasant side effects. Oral medication requires regular self‐administration otherwise effectiveness is reduced and the risk of relapse is high.

A solution to poor compliance is depot medication where medication is given by injection and is slowly released over a period of weeks. For people with schizophrenia it was hoped to be able to maintain care in the community with regular injections administered by community psychiatric nurses. Initial enthusiasm and the favourable results of clinical trials gave rise to the extensive use of depots as a means of long‐term treatment. Flupenthixol decanoate is one of the most widely used depot antipsychotics in the UK.

This review looks at the effectiveness of depot flupenthixol decanoate in comparison with no active treatment (placebo), oral antipsychotics and other depot preparations for people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. An electronic search for relevant trials was carried out in 2013. Fifteen trials with 626 participants could be included. All evidence from these trials was rated by the authors to be low or very low quality. Currently, from the data reported, there is nothing to choose between depot flupenthixol decanoate and other depot or oral antipsychotics. There was some evidence that it would be understandable to offer a standard dose rather than the high dose depot flupenthixol as there is no difference in relapse. Overall, this review highlights the lack of evidence based information available for the review question and the need for large, well‐designed and reported randomised clinical trials to address the medical, social, personal and economic effects of flupenthixol decanoate.

This plain language summary has been written by a consumer Ben Gray, Service User and Service User Expert: Rethink Mental Illness.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE compared with ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders.

| FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE compared to ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders Settings: inpatient/outpatient Intervention: FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE Comparison: ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS | FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE | |||||

| Clinical response: mental state ‐ relapse ‐ medium term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Clinical response: mental state ‐ general score ‐ medium term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Clinical response: global state ‐ no clinical improvement ‐ medium term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Service utilisation: hospital admission ‐ medium/long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Leaving the study early ‐ short term Rate of attrition Follow‐up: 12 weeks | 33 per 10001 | 100 per 1000 (11 to 908) | RR 3 (0.33 to 27.23) | 60 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | |

| Adverse effects: general ‐ movement disorders ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication ‐ short term Numbers requiring anticholinergic medication Follow‐up: 12 weeks | 533 per 10001 | 635 per 1000 (411 to 976) | RR 1.19 (0.77 to 1.83) | 60 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | |

| Economic outcomes ‐ long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Assumed risk: mean baseline risk presented for single study. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ attrition bias: in single study with no indication of how missing data were dealt with; reporting bias: outcomes incompletely addressed; other bias: pharmaceutical company involvement. 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ only one small study; confidence intervals for best estimate of effect include both 'no effect' and appreciable benefit/harm.

Summary of findings 2. FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE compared with OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders.

| FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE compared to OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders Settings: inpatient/outpatient Intervention: FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE Comparison: OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS | FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE | |||||

| Clinical response: mental state ‐ relapse ‐ medium term Relapse rate Follow‐up: mean 9 months | Low1 | RR 1.3 (0.87 to 1.93) | 221 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 100 per 1000 | 130 per 1000 (87 to 193) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 390 per 1000 (261 to 579) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 650 per 1000 (435 to 965) | |||||

| Clinical response: mental state ‐ general score ‐ skew Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) Follow‐up: 12 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5 | Data are highly skew and are therefore not pooled in meta‐analysis. |

| Clinical response: global state ‐ no clinical improvement ‐ short term Rates of improvement Follow‐up: 20 weeks | 667 per 10006 | 447 per 1000 (240 to 820) | RR 0.67 (0.36 to 1.23) | 36 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,7 | |

| Service utilisation: hospital admission ‐ medium/long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Leaving the study early ‐ short/medium term Rate of attrition Follow‐up: mean 8 months | Low1 | RR 1.23 (0.76 to 1.99) | 161 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,8 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 62 per 1000 (38 to 100) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 308 per 1000 (190 to 498) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 615 per 1000 (380 to 995) | |||||

| Adverse effects: general ‐ movement disorders ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication ‐ short/medium term Numbers requiring anticholinergic medication Follow‐up: mean 5 months | Low1 | RR 1.38 (0.75 to 2.52) | 102 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,7 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 69 per 1000 (38 to 126) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 138 per 1000 (75 to 252) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 414 per 1000 (225 to 756) | |||||

| Economic outcomes ‐ long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Assumed risk: 'moderate' equates to that of control group. Low, moderate and high risks calculated from included studies. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ 100% included studies did not explain randomisation procedure; 100% included studies judge at a 'high' risk of bias due to unreported outcomes; 60% studies rated as 'high' risk of bias for attrition bias. 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ confidence intervals for best estimate of effect include both 'no effect' and appreciable benefit/harm. 4 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ high rate of attrition with no details on how data were handled in analysis; incomplete outcome data. 5 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ data are considerable skew and not pooled in meta‐analysis. 6 Assumed risk: mean baseline risk presented for single study. 7 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation not described; incomplete outcome data reported. 8 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ all studies rated as a 'high' risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data or selective reporting. All studies rated as an 'unclear' risk of bias due to lack of description of randomisation.

Summary of findings 3. FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE HIGH DOSE compared with FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE STANDARD DOSE (˜40 mg/IM) for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders.

| FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE HIGH DOSE compared with FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE STANDARD DOSE (˜40 mg/IM) for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders Settings: inpatient Intervention: FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE HIGH DOSE Comparison: FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE STANDARD DOSE (˜40 mg/IM) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE STANDARD DOSE (˜40 mg/IM) | FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE HIGH DOSE | |||||

| Clinical response: mental state ‐ relapse ‐ medium term Relapse rate Follow‐up: 44 weeks | 333 per 10001 | 333 per 1000 (90 to 1000) | RR 1 (0.27 to 3.69) | 18 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | |

| Clinical response: mental state ‐ general score ‐ medium term Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Scale from: 0 to 126. Follow‐up: 44 weeks | The mean clinical response: mental state ‐ general score ‐ medium term in the control groups was 26.44 points | The mean clinical response: mental state ‐ general score ‐ medium term in the intervention groups was 10.44 lower (18.7 to 2.18 lower) | 18 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| Clinical response: global state ‐ no clinical improvement ‐ short/medium term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Service utilisation: hospital admission ‐ medium/long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Leaving the study early ‐ short/medium term Rate of attrition Follow‐up: mean 26 weeks | Low4 | RR 0.16 (0.03 to 0.82) | 42 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (6 to 164) | |||||

| Moderate4 | ||||||

| 400 per 1000 | 64 per 1000 (12 to 328) | |||||

| High4 | ||||||

| 600 per 1000 | 96 per 1000 (18 to 492) | |||||

| Adverse effects: general ‐ movement disorders ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication ‐ short term numbers requiring anticholinergic medication Follow‐up: mean 10.5 weeks | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 47 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | Data not pooled for summary of findings table due to substantial heterogeneity. |

| Economic outcomes ‐ long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Assumed risk: mean baseline risk from single study. 2 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ confidence intervals for best estimate of effect include both 'no effect' and appreciable benefit/harm; high degrees of heterogeneity (I2 = 59%). 3 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ no mention of randomisation procedure; unreported outcomes of interest; involvement by pharmaceutical company. 4 Assumed risk: 'moderate' equates to that of control group. Low, moderate and high risks calculated from included studies.

Summary of findings 4. FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE VERY LOW (˜6 mg/IM) DOSE compared with FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE LOW DOSE (˜9 mg/IM) for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders.

| FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE VERY LOW (˜6 mg/IM) DOSE compared with FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE LOW DOSE (˜9 mg/IM) for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders Settings: outpatient/community Intervention: FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE VERY LOW (˜6 mg/IM) DOSE Comparison: FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE LOW DOSE (˜9 mg/IM) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE LOW DOSE (˜9 mg/IM) | FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE VERY LOW (˜6 mg/IM) DOSE | |||||

| Clinical response: mental state ‐ relapse ‐ medium term Relapse rate Follow‐up: 12 months | 300 per 10001 | 102 per 1000 (30 to 345) | RR 0.34 (0.1 to 1.15) | 59 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | |

| Clinical response: mental state ‐ general score (BPRS) ‐ skew ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Clinical response: global state ‐ no clinical improvement ‐ short/medium term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Service utilisation: hospital admission ‐ medium/long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Leaving the study early ‐ medium/long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Adverse effects: general ‐ movement disorders ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication ‐ short/medium term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Economic outcomes ‐ long term ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Assumed risk: mean baseline risk presented for single study. 2 Risk of bias: rated as 'high' ‐ selective reporting of primary outcomes; pharmaceutical company‐funded. 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ confidence intervals for best estimate of effect include both 'no effect' and appreciable benefit/harm.

Background

Description of the condition

When using strict criteria, about one in 10,000 people per year are diagnosed with schizophrenia, with a lifetime prevalence of about 1% (Jablensky 1992). The schizophrenic disorders are characterised in general by fundamental and characteristic distortions of thinking and perception, and by inappropriate and blunted affect (International Classification of Diseases, ICD‐10, WHO). The illness often runs a chronic course with acute exacerbations and often partial remissions. The risk of death from all causes is 1.6 fold in patients with schizophrenia (Harris 1998). In the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010, mental illness and behavioural disorders accounted for 7.4% of all DALYs (disability‐adjusted life years), and were attributable to more than 15 million DALYs each; schizophrenia ranked as fifth under this category (accounting for 0.6%) after depression, anxiety, drug‐use and alcohol‐use disorders (Murray 2012). Disabilities experienced by people with schizophrenia are only partly due to recurrent episodes or continuing symptoms. Other factors that play a part are unpleasant side effects of treatment, social adversity and isolation, poverty and homelessness. Continuing prejudice, stigma and social exclusion associated with the diagnosis continue to play a major part (Sartorius 2002; Thornicroft 2006).

Experiencing a relapse of schizophrenia often lowers a person's level of social functioning and quality of life (Curson 1985). Prevention of such episodes is therefore crucial from a clinical point of view as well as having enormous financial implications. For example, within the UK, a Department of Health burden of disease analysis indicated that schizophrenia accounted for 5.4% of all National Health Service inpatient expenditure, placing it behind only learning disability and stroke in magnitude (DoH 1996). The total societal cost of schizophrenia has been estimated at £6.7 billion (in 2004/2005 prices) in England (Mangalore 2007). Inpatient care accounted for 56.5% of the total treatment and care costs of schizophrenia, compared with 2.5% for outpatient care and 14.7% for day care (Knapp 2002).

Description of the intervention

The mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia are antipsychotic drugs (Dencker 1980). Also called neuroleptics, they are generally regarded as highly effective, especially in controlling such symptoms as hallucinations and fixed false beliefs (delusions) (Kane 1986). They also seem to reduce the risk of acute relapse. A systematic review suggested that, for those with serious mental illness, stopping antipsychotic drugs resulted in 64% of people relapsing within a year compared with 27% of those who were still on medication within the same time period (Leucht 2012). Problems with adherence to treatment are common throughout medicine (Haynes 1979). Those who suffer from long‐term illnesses where treatments may have uncomfortable side effects (Kane 1998), cognitive impairments (David 1994) and erosion of insight may be especially prone to be unreliable at taking medication.

Depot antipsychotic injections, developed in the 1960s, mainly consist of an ester of the active drug held in an oily suspension. This is injected intramuscularly and released into the body slowly so may only need to be given every one to six weeks. It was hoped to be able to maintain people in the community with regular injections administered by community psychiatric nurses, sometimes in clinics set up for this purpose (Barnes 1994). Initial enthusiasm and the favourable results of clinical trials (Hirsch 1973) gave rise to the extensive use of depots as a means of long‐term maintenance treatment.

Flupentixol is a neuroleptic of the thioxanthene group. It exists in two geometric isomers, the cis(Z) and trans(E) forms of which only the cis(Z)‐flupenthixol is pharmacologically active. Flupenthixol decanoate is produced by esterification of cis(Z)‐flupentixol with decanoic acid. Depot ampoules/vials for injection have flupenthixol decanoate dissolved in thin vegetable oil.

How the intervention might work

Flupenthixol decanoate is usually given intramuscularly every two to four weeks. It is slowly released from the depot site, with a half‐life of three to eight days (Jorgensen 1980). The decanoate ester is then rapidly hydrolysed intracellularly to release the active cis(Z)‐flupenthixol, with only traces of decanoate remaining in the bloodstream (Jorgensen 1971). The serum T(max) for intramuscular flupenthixol decanoate is three to five days (Jorgensen 1980). Flupenthixol has no active metabolites (Jorgensen 1978a). Steady state is reached in about three months of administration (Saikia 1983).

Flupenthixol antagonizes dopamine binding primarily at D1, D2, D3 and with less affinity at D4 receptors; it also affects serotonin binding at 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2C receptors as well as noradrenaline binding at 1‐adrenergic receptors (Glaser 1998). Flupenthixol is a powerful antagonist of both D1 and D2 dopamine receptors, though it is no more potent a neuroleptic than other agents (e.g. haloperidol), which are D2 antagonists only (Ehmann 1987). It blocks prolactin inhibitory factor (PIF), resulting in an increase in pituitary prolactin secretion (Fielding 1978). Flupentixol has no affinity for cholinergic muscarine receptors, only slight antihistaminergic properties and no alpha2 adrenoreceptor blocking properties. The pharmacological profile of flupenthixol has definite similarities to atypical antipsychotics and can be described as at least partially atypical (Arnt 1998; Bandelow 1998; Glaser 1998). Flupenthixol is also said to resemble tricyclic antidepressants in some of its actions, though not in anticholinergic activity (Kato 1969).

Why it is important to do this review

Antipsychotic drugs are usually given orally (Aaes‐Jorgenson 1985), but compliance with medication given by this route is likely to be poor and, certainly, is difficult to quantify. Since development in the 1960s, depot antipsychotics have been used in maintenance treatment for people with schizophrenia for whom relapse prevention is indicated. Since the introduction of atypical antipsychotics, there has been a fall in the use of depot medications, as only one atypical antipsychotic medication (risperidone) was available in depot form. But non‐adherence to oral antipsychotic medications continues to be a major problem. In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials for Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, which ran for 18 months, 74% of patients discontinued antipsychotic medications prematurely (Lieberman 2005). Olanzapine, risperidone and paliperidone in their depot forms (olanzapine pamoate, risperdal consta and paliperidone palmitate respectively) have been available. The NICE Guideline on schizophrenia (March 2009), in its 'promoting recovery' section promotes the use of depot antipsychotics after an acute episode if acceptable to the patient and to avoid covert non‐adherence (NICE Guideline:CGS 82 Schizophrenia (update) 2009).

Flupenthixol in its depot form has been extensively used for maintenance and relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Individuals are reported to show an improvement in mood when used in maintenance treatment (Carney 1976; Chowdhury 1980) and also in treatment of relapses (Johnson 1975; Wistedt 1983). Flupenthixol decanoate has shown to have better tolerance and less side effects as compared to fluphenazine decanoate (Johnson 1975; Pinto 1979; Wistedt 1983). These might be due to the 'partial atypical' properties of flupenthixol and also resembling tricyclic antidepressants in some of its actions. At four‐weekly doses, flupenthixol decanoate could not keep psychotic symptoms in check as compared to haloperidol decanoate nor was there any conclusive evidence of anti‐depressant properties, and the authors have commented that two‐weekly dosing might be more appropriate (Eberhard 1986). A 12‐month prospective comparison of standard dose verus half dose flupenthixol decanoate for maintenance treatment indicated that a dose reduction had increased relapse significantly (Johnson 1987).

Flupenthixol decanoate is one of the most widely used depots in the UK. It is worth investigating the effects of flupenthixol decanoate in comparison with other antipsychotic medications with regards to clinical and non‐clinical outcomes for the benefits of clinicians, patients and managers/policy makers alike.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of flupenthixol decanoate in comparison with placebo, oral antipsychotics and other depot neuroleptic preparations for people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses, in terms of clinical, social and economic outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included relevant randomised controlled trials which were at least single‐blind (blind raters). Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind', but it was only implied that the study was randomised, we included these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures) when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we included these in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, we only used clearly randomised trials and described the results of the sensitivity analysis in the text. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week. Randomised cross‐over studies were included in this review but we only used data up to the point of the first cross‐over because of the instability of the problem behaviours and the likely carry‐over effects of all treatments.

Types of participants

People with schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders (e.g. schizophreniform, schizoaffective disorders), irrespective of diagnostic criteria used, were included. There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia‐like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994). Where a study described the participant group as suffering from 'serious mental illnesses' and did not give a particular diagnostic grouping these trials were included. The exception to this rule was when the majority of those randomised, clearly did not have a functional, non‐affective, psychotic illness.

Types of interventions

1. Flupenthixol decanoate: any dose.

2. Placebo.

3. Oral antipsychotics: any dose.

4. Other depot preparations: any dose.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes were grouped into immediate (zero to five weeks), short term (six weeks to five months), medium term (six months to 12 months) and longer term (over 12 months).

Primary outcomes

1. Clinical response

1.1 Relapse 1.2 Clinically significant response in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies

2. Service utilisation outcomes

2.1 Hospital admission

Secondary outcomes

1. Death, suicide or natural causes

2. Leaving the study early

3. Clinical response

3.1 Mean score/change in global state 3.2 Clinically significant response on psychotic symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.3 Mean score/change on psychotic symptoms 3.4 Clinically significant response on positive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.5 Mean score/change in positive symptoms 3.6 Clinically significant response on negative symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.7 Mean score/change in negative symptoms

4. Extrapyramidal side effects

4.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs 4.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies 4.3 Mean score/change in extrapyramidal side effects

5. Other adverse effects, general and specific

6. Service utilisation outcomes

6.1 Days in hospital

7. Economic outcomes

8. Quality of life/satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers

8.1. Significant change in quality of life/satisfaction ‐ as defined by each of the studies 8.2 Mean score / change in quality of life/satisfaction

9. 'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used the GRADEPRO profiler to import data from RevMan (Review Manager) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Clinical response: mental state ‐ relapse ‐ medium term

Clinical response: mental state ‐ general score ‐ medium term

Clinical response: global state ‐ no clinical improvement ‐ short term

Service utilisation: hospital admission ‐ medium/long term

Leaving the study early ‐ short/medium term

Adverse effects: movement disorders ‐ long term

Economic outcomes ‐ long term

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Relevant trials were identified by searching Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (March 2009). The Trials Register was searched using the phrase: [((flupent* or fluanxol* or depixol* or lu 7105 or lu 5‐110*) and (decanoate* or depot* or long?act* or delayed?acti) in REFERENCE title, abstract and index term fields) OR (((flupentixol dec* or (flupent* and depot*)) in STUDY interventions field)].

We also ran a separate trial search in April 2013 before submission in order to account for the lapse in time between the March 2009 update search. We searched the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS) using the phrase: (("*flupent*":TI OR "*flupent*":TI OR "*fluanxol*":TI OR "*fluanxol*":TI OR "*depixol*":TI OR "*depixol*":TI OR "*lu 7105*":TI OR "*lu 7105*":TI OR "*lu 5‐110*":TI OR "*lu 5‐110*":TI OR "*flupent*":AB OR "*fluanxol*":AB OR "*depixol*":AB OR "*lu 7105*":AB OR "*lu 5‐110*":AB OR "*flupentl*" OR "*fluanxol*" OR "*depixol*" OR "*lu 7105*" OR "*lu 5‐110*") AND ("*depot*":TI OR "*long?act*":TI OR "*delayed?act*":TI OR "*depot*":TI OR "*delayed?act*":TI OR "*long?act*":TI OR "*decanoat*":TI OR "*decanoat*":TI OR "*depot*":AB OR "*long?act*":AB OR "*delayed?act*":AB OR "*decanoat*":AB OR "*depot*" OR "*long?act*" OR "*delayed?act*" OR "*decanoat*")) AND [(2009:YR) AND (INREGISTER)] OR [(2010:YR) AND (INREGISTER)] OR [(2011:YR) AND (INREGISTER)] OR [(20129:YR) AND (INREGISTER)] OR [(2013:YR) AND (INREGISTER)].

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO), handsearches and conference proceedings (Schizophrenia Group Module). The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register is maintained on Meerkat 1.6. This version of Meerkat stores references as studies. When an individual reference is selected through a search, all references which have been identified as the same study are also selected. The search also included Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trial Register, controlled‐trials.com, ClinicalTrials.gov and ukclinicaltrials.org which include trails by drug companies.

The CRS has been developed by The Cochrane Collaboration to contain and maintain its Specialised Registers (SRs) of healthcare studies and their reports, together with records identified by handsearching of journals, and conference proceedings and records sourced from MEDLINE and EMBASE, published online in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (CRS).

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected the references of all identified studies for more trials.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of included studies for more information when adequate details was not available.

3. Drug companies

The search register included published and unpublished trials by drug companies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors JM and SQ independently inspected all reports identified from the search. Potentially relevant reports were identified and full papers were obtained for assessment. Once the full papers were obtained, we independently decided whether the studies met the review criteria. Where difficulties or disputes arose, we resolved these by discussion with CEA and DA. Had it been impossible to resolve disagreements by discussion, these studies would have been added to those awaiting assessment and we would have contacted the authors of the papers for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Data Extraction

JM and SQ independently extracted data from the selected trials. When disputes arose, we attempted to resolve these by discussion with CEA and DA. Had this not been possible and further information was necessary to resolve differences, we planned not to enter data and add the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment.

2. Management

Data were extracted onto standard simple forms. Where possible, data were entered in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for flupenthixol decanoate.

3. Rating scales

A wide range of instruments are available to measure outcomes in mental health studies. These instruments vary in quality and many are not validated, or are even ad hoc. It is accepted generally that measuring instruments should have the properties of reliability (the extent to which a test effectively measures anything at all) and validity (the extent to which a test measures that which it is supposed to measure) (Rust 1989). For outcome instruments some minimum standards had to be set. They were that the instrument: i. should have its psychometric properties described in a peer‐reviewed journal, specially for rating scales (Marshall 2000); ii. should not be written or modified by one of the trialists; iii. should be either a self‐report, or completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist); and, finally iv. should be a global assessment of an area of functioning (Marshall 1998).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

JM and SQ worked independently by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess trial quality. This new set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain additional information.

We have noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the Summary of findings tables.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Data types

Outcomes were assessed using continuous (for example changes on a behaviour scale), categorical (for example, one of three categories on a behaviour scale, such as 'little change', 'moderate change' or 'much change'), or dichotomous (for example, either 'no important changes or 'important change' in a person's behaviour) measures. Currently RevMan does not support categorical data so we were unable to analyse these.

2. Dichotomous data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the fixed‐effect risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. When the overall results were significant we calculated the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) and the number‐needed‐to‐harm (NNTH) as the inverse of the risk difference. Where possible, efforts were made to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It was generally assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

We carried out an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Data were presented on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis. Those who were lost to follow‐up were all assumed to have the negative outcome, with the exception of the outcome of death. For example, for the outcome of relapse, those who were lost to follow‐up were all assumed to have relapsed.

3. Continuous data

The meta‐analytic formulae applied by RevMan Analyses (the statistical programme included in RevMan) require a normal distribution of data. The software is robust towards some skew, but to which degree of skewness meta‐analytic calculations can still be reliably carried out is unclear. On the other hand, excluding all studies on the basis of estimates of the normal distribution of the data also leads to a bias, because a considerable amount of data may be lost leading to a selection bias. Therefore, we included all studies in the primary analysis. In a sensitivity analysis we excluded potentially skewed data applying the following rules: a) When a scale started from the finite number zero the standard deviation (SD), when multiplied by two, was more than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, Altman 1996). b) If a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210), the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. c) In large studies (as a cut‐off we used 200 participants), skewed data pose less of a problem. In these cases we entered the data in a synthesis. d) The rules explained in a) and b) do not apply to change data. The reasons is that when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values, it is difficult to tell whether data are non‐normally distributed (skewed) or not. This is also the case for change data (endpoint minus baseline). We preferred to use scale endpoint data, which typically cannot have negative values and is easier to interpret from a clinical point of view. Change data are often not ordinal and are very problematic to interpret. If endpoint data were unavailable, we used change data. We combined both endpoint data and change data in the analysis, because there is no principal statistical reason why endpoint and change data should measure different effects (Higgins 2011). Skewed data from studies of less than 200 participants were entered in additional tables rather than into an analysis. Skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large and thus were entered into syntheses.

For continuous outcomes we estimated a mean difference (MD) between groups based on the fixed‐effect model. When standard errors (SEs) instead of standard deviations (SDs) were presented, we converted the former to SDs. If both were missing we estimated SDs from P values or used the average SD of the other studies (Furukawa 2006).

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999). We did not include any cluster‐randomised studies in this review. In future updates of this review, if we include cluster‐randomised studies we will use the following methods.

Where clustering is not accounted for in primary studies, we will present data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. We will attempt to contact the first authors of studies to obtain the intraclass correlation co‐efficient (ICC) of their clustered data and adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will present these data as if from a non cluster‐randomised study, but adjust for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported, it will be assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICC and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies will be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in schizophrenia, we have only used data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

We did not identify any studies with multiple treatment groups in our trial search. For future updates of this review, where a study involves more than two treatment arms, if relevant, the additional treatment arms will be presented in comparisons. If the additional treatment arms are not relevant, these data will not be reproduced.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We are forced to make a judgment where this is for the very short‐term trials likely to be included in this review. Should more than 40% of data be unaccounted for we decided not to reproduce these data or use them within analyses.

2. Binary outcomes

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 40% and outcomes of these people were described, we included these data as reported. Where these data were not clearly described, we assumed the worst primary outcome.

3. Continuous

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 40% and completer‐only data were reported, we have reproduced these.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies within any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity.

2. Statistical

2.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

2.2 Employing the I‐squared statistic

Visual inspection was supplemented using, primarily, the I2statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I2 estimate was greater than or equal to 50%, we interpreted this as indicating the presence of considerable levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). If this occurred, we re‐analysed data excluding the source(s) of heterogeneity to see if this made a substantive difference to the final result.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We had planned not to use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes.There were no meta‐analyses with 10 or more studies providing data, therefore no funnel plots were constructed.

Data synthesis

Where possible we employed a fixed‐effect model for analyses. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us, however, random‐effects does put added weight onto the smaller of the studies ‐ those trials that are most vulnerable to bias. For this reason we favour using fixed‐effect models employing random‐effects only when investigating heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If data were clearly heterogeneous we checked that data were correctly extracted and entered and that we had made no unit‐of‐analysis errors. If the high levels of heterogeneity remained we did not undertake a meta‐analysis at this point for if there is considerable variation in results, and particularly if there is inconsistency in the direction of effect, it may be misleading to quote an average value for the intervention effect. We would have wanted to explore heterogeneity. We did not pre‐specify any characteristics of studies that may be associated with heterogeneity except the quality of trial method. If no clear association could be shown by sorting studies by quality of methods a random‐effects meta‐analysis was performed. Should another characteristic of the studies be highlighted by the investigation of heterogeneity, perhaps some clinical heterogeneity not hitherto predicted but plausible causes of heterogeneity, these post‐hoc reasons will be discussed and the data analysed and presented. However, had the estimate of the effect size have been substantially unaffected by use of a random‐effects model, and no other reasons for the heterogeneity were clear, the final data were presented without a meta‐analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

If necessary, we analysed the effect of including studies with high attrition rates in a sensitivity analysis. We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described as 'double‐blind' but only implied randomisation. If we found no substantive differences within the primary outcomes when these high attrition and 'implied randomisation' studies were added to the overall results, we included them in the final analysis. However, if there was a substantive difference, we only used clearly randomised trials and those with attrition lower than 40%.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive description of studies please see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

The overall search strategy yielded 693 reports of which 122 were closely inspected. One study from the 2009 update search was included (Eufe 1979); however, the 2013 update search yielded zero results.

Included studies

Fifteen studies with 626 participants met the inclusion criteria. All included studies stated that they were randomised (Figure 1). We have excluded Dencker 1980a from this review update, which was included in the original publication. This study was mistakenly included, and it was discovered during the course of this update that it compared flupenthixol palmitate, as opposed to flupenthixol decanoate. We identified one new study from our update search to include in this update (Eufe 1979). Therefore, there are still 15 included studies.

1.

Study flow diagram: review update for 2009 and 2013

1. Duration

The duration of the trials ranged between two months (Cookson 1983) to two years (Wistedt 1983).

2. Participants

All participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia or some other similar psychotic disorder. Four studies included participants with operationalised diagnoses according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM‐III) (Eberhard 1986; Javed 1991; Lundin 1990; Martyns 1993) and two studies according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐9) (Cookson 1987; Eufe 1979). Four studies used the Fieghner's criteria to include participants (Cookson 1983; Cookson 1987; Johnson 1987; McCreadie 1979). One study used the Bleuler's criteria (Wistedt 1983) and one study used Schneider's first rank symptoms (Kelly 1977). Three studies had no clearly operationalised criteria, but the patients were being treated for chronic schizophrenia already (Gerlach 1975; Pinto 1979; Wistedt 1982). One study (Steinert 1986) used the operational definition of schizophrenia by Priest 1977.

Most studies included people of both sexes although three randomised only men (Cookson 1983; Gerlach 1975; Martyns 1993), and one only women (McCreadie 1979). One study (Pinto 1979) failed to mention the sex of the participants in the trial. Ages ranged between 18 to 67 years.

3. Setting

The trials were conducted in a variety of settings. Two trials, Eberhard 1986 and Gerlach 1975, were set in both the hospital and community. Four trials were based on patients in psychiatric hospitals (Cookson 1983; Eufe 1979; McCreadie 1979; Steinert 1986) and participants in one study (Martyns 1993) were based in a prison hospital. Six trials were conducted in community (outpatient) settings (Johnson 1987; Kelly 1977; Lundin 1990; Pinto 1979; Wistedt 1982; Wistedt 1983).Two studies, however, failed to mention the trial setting (Cookson 1987; Javed 1991).

4. Study size

Pinto 1979 is the largest study with 64 participants and Gerlach 1975 the smallest with 12 participants. Cookson 1987 randomised 18 participants and McCreadie 1979 randomised 23. The rest of the trials randomised between 30 and 60 participants.

5. Interventions

Overall, the trialists used depot antipsychotics in a wide range of doses. Mean doses of flupenthixol decanoate ranged from 6 mg to 200 mg. The frequency of administration ranged from every two weeks to every four weeks. No trial compared the depot formulation with placebo. Only one study compared flupenthixol decanoate with an oral antipsychotic, penfluridol (Gerlach 1975). Four studies compared different dosages of flupenthixol decanoate (Cookson 1983; Cookson 1987; Johnson 1987; McCreadie 1979). Ten studies compared depot flupenthixol with other depots ‐ haloperidol decanoate (Eberhard 1986), fluphenazine decanoate (Javed 1991; Kelly 1977; Lundin 1990; Pinto 1979; Wistedt 1982; Wistedt 1983), clopenthixol decanoate (Martyns 1993), pipotiazine palmitate (Steinert 1986), and perphenazine enanthate (Eufe 1979).

6. Outcomes

1. Leaving the study early

Eight studies provided data on participants leaving the study early (Cookson 1983; Cookson 1987; Eberhard 1986; Gerlach 1975; Lundin 1990; Pinto 1979; Steinert 1986; Wistedt 1983).

2. Mental state

Several scales were used in the trials to measure mental state. If possible we used binary data from these measures, but the validity of dichotomising from these measures, although widely accepted, is nevertheless unclear. Some mental state data were not provided or unusable in many studies (Cookson 1983; Eufe 1979; Javed 1991; Johnson 1987; Kelly 1977; Lundin 1990; Martyns 1993; McCreadie 1979; Pinto 1979; Steinert 1986; Wistedt 1982; Wistedt 1983).

3. Global outcomes

Though six studies (Gerlach 1975; Javed 1991; Johnson 1987; Lundin 1990; Martyns 1993; Wistedt 1983) used scales for global assessment, no study provided usable data for this. One study (Martyns 1993) reported on global impression of trialists as regards treatment outcome of clinical improvement. Eufe 1979 provided usable data for global state on a five‐point scale from symptom free to worsening which we analysed as 'at least minimally better' and 'at least clearly better'.

4. Adverse effects

Four studies provided usable data on adverse effects (Javed 1991; Martyns 1993; Pinto 1979; Wistedt 1983). Six studies indicated the need for the use of anticholinergic medications in the trials (Cookson 1983; Eberhard 1986; Gerlach 1975; McCreadie 1979; Pinto 1979; Wistedt 1982).

Not one study evaluated hospital/service outcomes, satisfaction with care and economic outcomes. Trialists used a variety of scales, which are listed below. Reasons for exclusion of data from meta‐analysis are given under 'Outcomes' in the 'Included studies' section.

5. Global functioning

1. Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ CGI (Guy 1976) A rating instrument commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement during therapy by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. The CGI consists of two scales: a state scale and an improvement scale. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement.

5. Mental state

5.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) A brief rating scale used to assess the severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic symptoms. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from zero to six or one to seven. Scores can range from zero to 126 with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

5.2 Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale ‐ CPRS (Asberg 1978) A four‐point scale is used by the participant to rate 40 items, and 25 items are rated using the same scale. Global rating of the illness is an additional item also rated using this scale. Assumed reliability of the rating is scored as zero (very poor), one (fair), two (good) or three (very good).

5.3 Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression ‐ HDRS (Hamilton 1960) This instrument is designed to be used only on patients already diagnosed as suffering from affective disorder of depressive type. It is used for quantifying the results of an interview, and its value depends entirely on the skill of the interviewer in eliciting the necessary information. The scale contains 17 variables measured on either a five‐ or a three‐point rating scale, the latter being used where quantification of the variable is either difficult or impossible. Among the variables are: depressed mood, suicide, work and loss of interest, retardation, agitation, gastro‐intestinal symptoms, general somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis, loss of insight, and loss of weight. It is useful to have two raters independently scoring a patient at the same interview. The scores of the patient are obtained by summing the scores of the two physicians. High scores indicate greater severity of depressive symptoms.

5.4 Krawiecka Scale (Krawiecka 1977) This mental state scale encompasses both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It is used to evaluate the mental state and behaviour in chronic psychotic people with higher scores indicating greater severity. It is also known as the Manchester Scale.

6. Behaviour

1. Nurses Observational Scale of Inpatients Evaluation ‐ NOSIE (Honigfeld 1962) This 80‐item scale allows ratings from zero to four (zero ‐ never present, four ‐ continually present). Ratings are taken from behaviour over the previous three days. The seven headings are social competence, social interest, personal neatness, co‐operation, irritability, manifest psychosis and finally, psychotic depression. Scoring ranges from zero to 320.

7. Adverse effects scales

7.1 Abnormal Involuntary Movement Side Effects Scale ‐ AIMS (Guy 1976) This is a 12‐item scale designed to record the occurrence of dyskinetic movements. Ten items of this scale have been used to assess tardive dyskinesia, a long‐term drug‐induced movement disorder. A five‐point scoring system (from zero ‐ none to four ‐ severe) has been used to rate each of the 10 items. This scale may also be helpful in assessing some short‐term abnormal movement disorders. A low score indicates low levels of dyskinetic movements.

7.2 Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale ‐ ESRS (Chouinard 1980) This consists of a questionnaire relating to parkinsonian symptoms (nine items), a physician's examination for parkinsonism and dyskinetic movements (eight items), and a clinical global impression of tardive dyskinesia. High scores indicate severe levels of movement disorder.

7.3 Simpson and Angus Scale (Simpson 1970) A standard physical examination which measures parkinsonism. This scale comprises of a 10‐item rating scale, each item rated on a five‐point scale with zero meaning the complete absence of condition and four meaning the presence of condition in extreme. The total score is obtained by adding the items and dividing by 10.

Excluded studies

We excluded 107 studies from the review, 54 of which were due to inappropriate intervention. Of the remaining 53 studies which involved flupenthixol decanoate, 25 were not randomised and 13 studies either had no usable data or data from the flupenthixol and other drugs were analysed together rather than separately (Curson 1985; Wistedt 1981). We have contacted all authors for further details. No replies have been received.

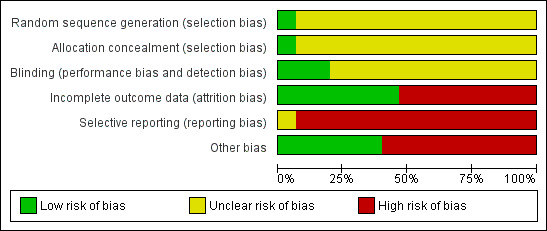

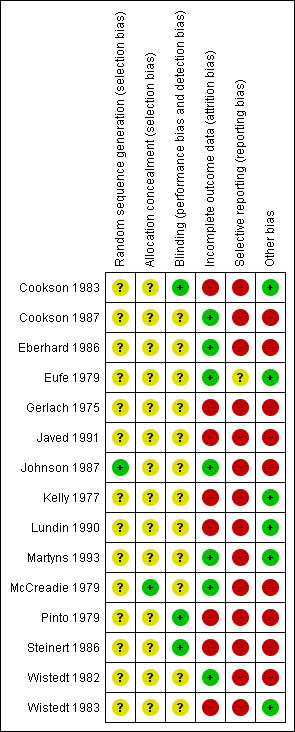

Risk of bias in included studies

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All studies included in this review stated that they were randomised. Most of the studies gave no information on the process of sequence generation. Only in one study (Johnson 1987) was allocation to groups on the basis of sealed computer randomisation. Another study (Eberhard 1986) stated that randomisation was in blocks of six, but did not specify exactly how the allocation was undertaken. There is no description of allocation concealment in 12 studies. One study (McCreadie 1979) stated that codes were used for concealment. In the study Kelly 1977, the key to allocation concealment was unknown to the raters. Another study (Pinto 1979) indicated that rating clinicians were unaware of treatment allocation. As poor reporting of randomisation and allocation concealment has consistently been associated with an overestimate of effect, in all but one study was allocation concealment rated as 'unclear' or quality 'B'. The results in these trials are likely to be a 30% to 40% overestimate of effect (Schulz 1994; Moher 1998).

Blinding

Thirteen studies stated themselves to be 'double blind' but most discussed blinding of assessors and personnel only. One study (Kelly 1977) did not discuss blinding. Martyns 1993, described blinding as the nurse administering the depot was blind to assessments and the assessment team was blind to the drug administered. Testing of blinding was discussed by only one study (McCreadie 1979) but only for outcome assessors and study personnel. Failing to test double blinding may cast doubt on the quality of trial data. Scale data, which was often measured in the included studies, may be prone to bias when unblinding has taken place. This adds further potential for possible overestimate of positive effects and underestimate of negative ones.

Incomplete outcome data

Nine studies reported the number of participants leaving the study early due to any reason. In four of these studies the reasons for attrition was explained. There were high attrition rates in three studies, Lundin 1990 ‐ 34.48%, Steinert 1986 ‐ 41.02% and Wistedt 1983 ‐ 56.25%. High attrition rates are a threat to internal validity. For other studies, rates of attrition varied from 6.6% (Gerlach 1975) to 20% (Cookson 1983). Most studies did not explain how they accounted for attrition. Eufe 1979, used the last‐observation‐carried‐forward method. The Cookson 1983 study, reported a 50% (5/10) attrition rate in the control (standard dose of flupenthixol decanoate) group after two months. The protocol for this review pre‐stated that this was an unacceptable degree of loss so the data are not used in the overall analyses. Overall, in Pinto 1979 and Steinert 1986 the reasons for attrition were well reported.

Selective reporting

Nine studies (Cookson 1983, Eufe 1979, Gerlach 1975, Kelly 1977, Lundin 1990, McCreadie 1979, Steinert 1986, Wistedt 1982, Wistedt 1983) were found not to be free of selective reporting of prespecified out comes. This gives rise to the possibility of 'within‐study publication bias' affecting results of these studies. It is possible that statistically significant differences between groups are more likely to be reported that non‐significant differences. Also many of the trials presented their findings in graphs or by P values alone. Graphical presentation alone made it impossible to acquire raw data for synthesis. Requests for raw data from authors have so far failed to obtain the data. It was also common to use P values as a measure of association between intervention and outcomes instead of showing the strength of the association.

Other potential sources of bias

There was involvement of the pharmaceutical industry in seven of the studies. Cookson 1987, received financial assistance. Johnson 1987, received financial assistance and help in statistical analyses. Gerlach 1975, received help in statistical analyses and also supply of medications used. Medication was supplied by pharmaceutical companies to one more study (Wistedt 1982). One study (Eberhard 1986) received 'active collaboration' and two studies (Javed 1991; McCreadie 1979) thanked pharmaceutical companies for unclear reasons. There is evidence that pharmaceutical companies sometimes highlight benefits of their compounds and tend to suppress disadvantages (Heres 2006). Other sources for potential bias were difference in pre‐study treatment (Pinto 1979), use of supplementary neuroleptics (Cookson 1987) and short or no wash‐out period (McCreadie 1979; Steinert 1986).

For full details of risk of bias in individual studies please see 'Risk of bias' tables in the Included studies section.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Missing outcomes

No study compared flupenthixol decanoate with placebo. No trial directly reported hospital and service outcomes or commented on participants' overall satisfaction during or after the trial. Economic outcomes were not assessed by any of the included studies.

We calculated risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous data and mean differences (MD) for continuous data, with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) throughout.

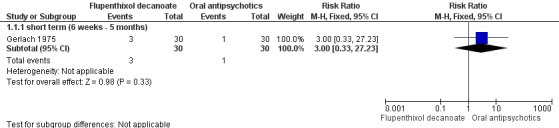

COMPARISON 1. FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Only one study (Gerlach 1975) compared flupenthixol decanoate with an oral antipsychotic, in this case, oral penfluridol. No data were reported for global impression or mental state outcomes. Gerlach 1975 found no significant difference between groups for attrition at short term (n = 60, 1 RCT, RR 3.00, CI 0.33 to 27.3, Analysis 1.1, Figure 4) or those requiring additional anticholinergic drugs to help with side effects (n = 60, 1 RCT, RR 1.19, CI 0.77 to 1.83, Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Leaving the study early.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, outcome: 1.1 Leaving the study early.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Adverse effects: 1. general ‐ movement disorders.

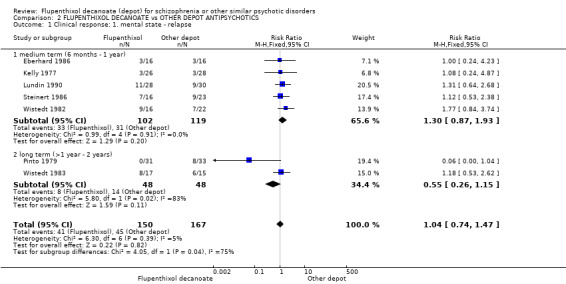

COMPARISON 2. FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS

2.1 Clinical response: mental state

2.1.1 Relapse

Seven studies reported 'relapse' as an outcome. No difference was found between the flupenthixol decanoate group and those allocated to other depots at both medium and long term (n = 317, 7 RCTs, RR 1.04, CI 0.74 to 1.47). The lack of difference in effect was true both for medium term (six months to one year) (n = 221, 5 RCTs, RR 1.30, CI 0.87 to 1.93) and for long term (> one year) (n = 96, 2 RCTs, RR 0.55, CI 0.26 to 1.15, Analysis 2.1). Heterogeneity was introduced by the 'long term' arm of this outcome because of the Pinto 1979 study. It is unclear why this study should add heterogeneity but removal of the study does not effect the result as reported above to any substantial degree.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Clinical response: 1. mental state ‐ relapse.

2.1.2 General score

Skewed data (obtained for the CPRS and BPRS change scores) were not formally analysed. The data are from two small studies (Eberhard 1986 n = 32, Steinert 1986 n = 39). They are supportive of the overall impression that no difference is apparent in the mental state of those who take flupenthixol decanoate and those given other depot antipsychotic drugs (Analysis 2.2 and Analysis 2.3).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Clinical response: 2. mental state ‐ general score (BPRS change scores, skewed data).

| Clinical response: 2. mental state ‐ general score (BPRS change scores, skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | INTERVENTION | Mean | Standard Deviation | Total (N) |

| medium term (6 months ‐ 1 year) | ||||

| Steinert 1986 | Flupenthixol decanoate | 0.89 | 8.8 | 16 |

| Steinert 1986 | Other depot | 7.18 | 12.4 | 23 |

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 3 Clinical response: 3. mental state ‐ general score (CPRS change scores, skewed data).

| Clinical response: 3. mental state ‐ general score (CPRS change scores, skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | Standard Deviation | Total (N) |

| medium term (6 months ‐ 1 year) | ||||

| Eberhard 1986 | Flupenthixol Decanoate | 5.7 | 7.2 | 16 |

| Eberhard 1986 | Other depot | 7.2 | 7.2 | 16 |

2.2 Clinical response: global state

One study (Eufe 1979) reported on global state regarding ‘minimal improvement’ and ‘clear improvement’. It found flupenthixol decanoate to compare unfavourably with perphenazine enanthate in the 'not minimally better' group by short term (n = 32, 1 RCT, RR 4.00, CI 1.00 to 15.99, Analysis 2.4, NNTH 3 CI 1.5 to 12.3) and in 'not clearly better' group by short term (n = 32, 1 RCT, RR 2.00, CI 1.00 to 4.00, Analysis 2.5, NNTH 3 CI 1.4‐17.6). Martyns 1993 reported on the global impression of the trialists as regards improvement, 'clinically not improved'. There was no difference between the two groups (n = 36, 1 RCT, RR 0.67, CI 0.36 to 1.23, Analysis 2.6), regardless of which depot was prescribed.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 4 Clinical response: 4. global state ‐ 'not minimally better' (five point scale).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 5 Clinical response: 5. global state ‐ 'not clearly better' (five point scale).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 6 Clinical response: 6. global state ‐ no clinical improvement.

2.3 Leaving the study early

Overall there was no significant difference between groups (n = 257, 6 RCTs, RR 0.94, CI 0.63 to 1.40). This lack of difference in effect holds true in the short term (n = 32, 1 RCT, RR 2.00, CI 0.20 to 19.91), medium term (n = 129, 3 RCTs, RR 1.19, CI 0.73 to 1.94) and long term (n = 96, 2 RCTs, RR 0.55, CI 0.26 to 1.15, Analysis 2.7).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 7 Leaving the study early.

2.4 Adverse effects

2.4.1 General adverse effects (non‐specific)

Two small trials reported a statistically significant difference, favouring flupenthixol decanoate, for 'general side effects' by short term (n = 74, 2 RCTs, RR 0.68, CI 0.52 to 0.91, Analysis 2.8, NNTB 4 CI 2.1 to 10.3) but it is not entirely clear what was meant by general side effects.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 8 Adverse effects: 1. general ‐ non‐specific.

2.4.2 General movement disorders

Two small studies, reported a significant difference in general (marked) movement disorders in favour of flupenthixol decanoate (n = 96, 2 RCTs, RR 0.54, CI 0.33 to 0.87, NNTB 6 CI 2.7 to 820.6) This has to be interpreted with caution as the heterogeneity is high (I2 = 88%) due to the Pinto 1979 study. Use of anticholinergic medications for adverse effects was reported by four studies, and there was no difference between comparison groups at short term (n = 32, 1 RCT, RR 2.00, CI 0.20 to 19.91) or medium term (n = 70, 2 RCTs, RR 1.31, CI 0.71 to 2.43) but with a significant result favouring flupenthixol decanoate by long term (n = 64, 1 RCT, RR 0.46, CI 0.29 to 0.73, Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 9 Adverse effects: 2. general ‐ movement disorders.

2.4.3 Specific movement disorders

For specific movement disorder, such as tremor (n = 32, 1 RCT, RR 1.01, CI 0.48 to 2.11) or tardive dyskinesia (n = 32, 1 RCT, RR 1.26, CI 0.64 to 2.47, Analysis 2.10) no significant differences were found between the groups at long term.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 10 Adverse effects: 3. specific ‐ movement disorders.

2.4.4 Anticholinergic effects

No significant difference was reported for blurred vision or dry mouth between the comparison groups at long term (n = 32, 1 RCT, RR 1.13, CI 0.56 to 2.29; and n = 32, 1 RCT, RR 1.39, CI 0.73 to 2.64 respectively, Analysis 2.11). It should be noted that data on specific adverse effects (tardive dyskinesia, tremor, blurred vision and dry mouth) all come from one small study (Wistedt 1983 n = 32).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE vs OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 11 Adverse effects: 4. specific ‐ anticholinergic effects.

COMPARISON 3. FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE HIGH DOSE versus FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE STANDARD DOSE (˜40 mg/IM)

3.1 Clinical response: mental state

3.1.1 Relapse

Two high0dose versus standard‐dose trials reported no difference in the number of relapses between groups at short and medium term (n = 42, 2 RCTs, RR 0.43, CI 0.16 to 1.19). This lack of difference between groups held true for relapse by eight weeks (short term ‐ n = 24, 1 RCT, RR 0.14, CI 0.02 to 1.04) and relapse by 44 weeks (medium term ‐ n = 18, 1 RCT, RR 1.00, CI 0.27 to 3.69, Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE HIGH DOSE vs FLUPENTHIXOL DECANOATE STANDARD DOSE (˜40 mg/IM), Outcome 1 Clinical response: 1. mental state ‐ relapse.

3.1.2 General score