Abstract

Glomus tumors (GTs) are rare, usually benign, mesenchymal neoplasms typically located in the cutaneous tissues of the extremities. Visceral locations have been reported in ∼5% of cases. The average age at diagnosis is 42 years. GTs originating in the respiratory tract of pediatric patients are exceedingly rare. We report a 16-year-old male with a GT of the right lower lobe bronchus.

Keywords: glomus tumor, lung, pediatric, soft tissue tumors, histology

Introduction

Glomus tumors (GTs) are mesenchymal neoplasms accounting for <2% of all soft tissue tumors.1 They arise from the glomus body, a neuromyoarterial structure comprised of vascular, nervous, and connective tissue.2 The glomus body regulates temperature through arterial smooth muscle contraction causing arteriovenous shunting. Cutaneous tissues, particularly those of the digits, are densely populated with glomus bodies. GTs are most commonly reported in the digits, hands, and feet, and remainder of the upper and lower extremities. A typical presentation is a painful subungual mass. Two series reported by Folpe et al. and Chou et al. suggest that 95% of GTs are cutaneous and 5% are visceral.3,4 The mean age at diagnosis is 42 years.

Although GTs are most commonly reported in the extremities, they have been reported in deep soft tissues and viscera including mediastinum, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and bone.3–6 Case reports describe tracheal and other respiratory tract involvement.7–10 In most reports, the vast majority of patients were adults. In Chou et al.'s4 series, only 4 of 52 patients were children; 3 were cutaneous and 1 involved the lung.3 We report a child with an exceedingly rare glomus tumor of the right lower lobe bronchus.

Case Report

A 16-year-old male with a history of asthma presented with acute onset of fever, cough, and shortness of breath. A chest radiograph demonstrated right lower lobe pneumonia. He was treated with 2 courses of antibiotics and oral steroids and a second chest radiograph was obtained after symptoms failed to improve. This demonstrated a nonresolving right lower lobe pneumonia leading to a pediatric pulmonology referral.

Review of systems was positive for dyspnea, fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss but no hemoptysis. Breath sounds were diminished over the right middle and lower lobes. Repeat chest radiograph demonstrated right middle and lower lobe airspace disease and right subpulmonic effusion (Fig. 1). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest revealed an intraluminal enhancing mass completely obstructing the right lower lobe bronchus at the level of the bronchus intermedius (Fig. 2).

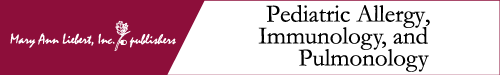

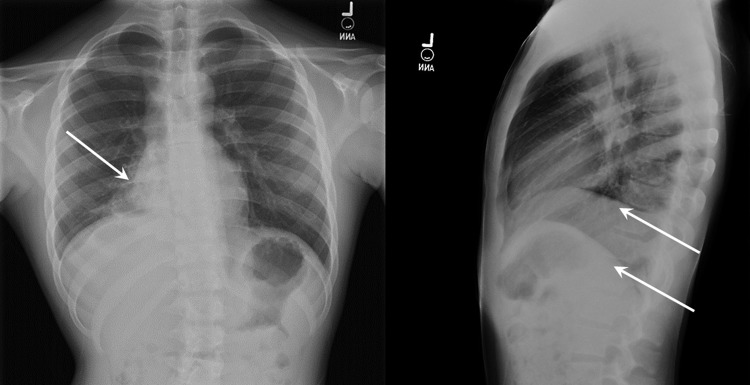

FIG. 1.

Chest radiographs demonstrating consolidative process involving portions of right middle and lower lobes (single arrow). A sub-pulmonic process on the right suggests a pleural effusion or pleural reactivity (double arrows).

FIG. 2.

Axial computed tomography image (A) demonstrates superior margin of enhancing intraluminal mass distal to the bronchus intermedius (arrow). (B) Demonstrates 1.4 × 1.6 × 2.2 mass completely obstructing lower lobe bronchus (arrow) with postobstructive pneumonia and bronchiectasis.

Rigid bronchoscopy was performed and a soft tissue exophytic mass completely obstructing the distal bronchus intermedius/right lower lobe bronchus was identified and biopsied. Initial frozen section and permanent sections were suggestive of neuroendocrine tumor such as carcinoid, but immunohistochemistry did not support this. Subsequent evaluation indicated the mass was a glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP).

Because imaging indicated significant irreversible damage to the right lower lobe and probable right middle lobe involvement, right middle and lower lobe lobectomies were performed. Subsequent pathology confirmed GTUMP, with clear margins and negative lymph nodes. Close clinical follow-up was recommended. The patient did well clinically until he transitioned to adult care at 18 years of age and was lost to follow-up. The family consented to the presentation/publication of this material for educational purposes.

Pathology

The initial biopsy specimen showed a proliferation of neoplastic cells arranged in sheets and nests with focal organoid arrangement and areas with a delicate hemangiopericytomatous pattern (Fig. 3A). The intraoperative frozen section diagnosis was reported as neoplastic tissue with necrosis suggestive of neuroendocrine tumor, possibly carcinoid. Permanent sections confirmed the uniform nature of the tumor cells and revealed round to oval cells with clearly defined cytoplasmic membranes and clear to amphophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3B). A periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain highlighted the cells and showed a delicate PAS positive basement membrane individually surrounding most of tumor cells. Many nuclei showed fine chromatin with small central nucleoli. Mitotic figures in the biopsy were only focally noted, with a maximum mitotic count of 2 mitoses per 10 high power fields (HPFs, 400 × ). There were foci of necrosis, granulation tissue, and ulcerated bronchial metaplastic squamous epithelium. Residual benign ciliated bronchial epithelium was also noted in the specimen.

FIG. 3.

(A) Tumor within the lumen and wall of the bronchus. Normal bronchial mucosa is on the left. H&E; 20 × . (B) Tumor is lobulated with sheaths of uniform cells with distinct membranes, moderate amphophilic cytoplasm, round nuclei with dispersed chromatin; some cells have visible small nucleoli. H&E; 200 × . (C) Smooth muscle actin shows positive cytoplasmic staining by immunohistochemistry; 400 × . (D) CD34 stain; showing richly vascular tumor; 100 × . H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the neoplastic cells revealed diffusely positive stain for anti-alpha smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Fig. 3C). Rare cells show cytoplasmic positivity for synaptophysin. The tumor cells were negative for chromogranin, CD99, cytokeratin CK AE1/AE3, and CD56. CD34 highlighted prominent capillary network and nesting pattern in parts of the tumor (Fig. 3D). Ki-67 proliferative index was 2.2%. The diagnosis of glomus tumor of unknown malignant potential was made following internal and external consultation.

Due to the uncertain malignant potential of the tumor and the need for additional staging, right middle and lower lobectomies with lymph node dissection were performed.

The right lower lobectomy specimen contained an exophytic, polypoid, tan, firm mass measuring 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm × 1.7 cm located within the bronchus intermedius. The proximal bronchial surgical margin was 0.7 cm from the tumor. The lung parenchyma in both the right middle and lower lobes was firm, slightly nodular with a hepatized cut surface. The tumor did not grossly extend into the lung parenchyma. Microscopically, sections revealed an exophytic mass arising from the wall of the bronchus extending into and occluding the bronchial lumen. Identical histological and immunohistochemical features as described in the biopsies, were present. Approximately 7% of the mass was necrotic. Mitoses were readily identified (5/10 HPF). Three sampled perihilar lymph nodes were negative for metastases and all inked surgical margins were free of tumor. A single vessel adjacent to the tumor revealed intravascular tumor. The final diagnosis was glomus tumor of unknown malignant potential, vascular invasion identified.

Discussion

Glomus tumors are rare, generally benign neoplasms of cutaneous/subcutaneous tissue originating from the glomus body, a neuromyoarterial structure controlling skin temperature by regulating blood flow.4 Most GTs occur in the skin of the digits. Other locations including extremities, trunk, and head/neck are reported.3,4 Noncutaneous locations are rarely reported but include deep soft tissues, mediastinum, bone, stomach, and small bowel.2 The respiratory tract is an unusual location for GTs though tracheal, bronchial, and parenchymal tumors occur.5–10 There is equal sex distribution of GTs though women may have more digital lesions. GTs are primarily a disease of adults; mean age at presentation of 42 years. Reports of GTs among children include 2 cutaneous lesions, primary pulmonary glomangiosarcoma, tracheal tumor, and unspecified.3,4,7

GTs form unencapsulated masses with irregular, nodular, dark red surfaces. Structures are well circumscribed and are comprised of rounded tumor cells, vasculature, and smooth muscle.2 Nuclei are round to oval with dispersed chromatin and without significant pleomorphism; cytoplasm is amphophilic to eosinophilic. Cells are well demarcated and accentuated with reticulin, toluidine blue, or periodic acid-Schiff staining.1,2 Under high power microscopy, nuclei show a bland chromatin pattern with inconspicuous to well-defined nucleoli.2 Cytoplasm contains bundles of thin, actin-like filaments.11 Glomus cells are immunoreactive with SMA and collagen IV.2,3 The histopathological differential diagnosis includes carcinoid tumor, epithelioid melanocytoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and lymphoma. Histopathology and immunohistochemical stains are essential in classification. A selected panel of antibodies including chromogranin, synaptophysin, HMB-45, MART-1, SMA, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD34, MyoD1, myogenin, and lymphoid markers, assist diagnosis of atypical cases.

GTs are classified as typical (benign), symplastic, malignant (glomangiosarcoma), and of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP).1,11 These are modifications of Folpe et al.'s classification and previously published systems.3 Goldblum et al. classifies malignant GT as having marked atypia and mitotic activity (>5/50 HPF) or atypical mitotic figures.1 A tumor is classified as GTUMP if it is in a superficial location and has high mitotic activity (>5/50 HPF) or is large in size (>2 cm) and/or in a deep location.1 Symplastic GT lack criteria for malignant GT but have marked nuclear atypia. The World Health Organization classification is similar.11 Most GTs are benign, but malignant GTs and GTUMPs are reported.1,12

Benign GTs are excised but have 10% recurrence.1 Metastases developed in 38% of patients.3 GTUMP should behave as benign GTs. However, because of their large size and paucity of reported cases, these tumors require close follow-up after resection.1

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

References

- 1. Goldblum JR, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Perivascular tumors. In: Goldblum JR, Folpe AL, Wess SW, eds. Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors, sixth ed., Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2014, pp. 749–765 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008; 132:1448–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chou T, Pan SC, Shieh SJ, et al. Glomus tumor: twenty-year experience and literature review. Ann Plast Surg 2016; 76 Suppl 1:S35–S40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaertner EM, Steinberg DM, Huber M, et al. Pulmonary and mediastinal glomus tumors—report of five cases including a pulmonary glomangiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study with literature review. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24:1105–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dong LL, Chen EG, Sheikh IS, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the lung with multiorgan metastases: case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther 2015; 8:1909–1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haver KE, Hartnick CJ, Ryan DP, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 10–2008. A 10-year-old girl with dyspnea on exertion. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1382–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brzeziński D, Łochowski MP, Jesionek-Kupnicka D, et al. Extracutaneous glomus tumour of the trachea. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol 2015;12:269–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernandez-Bussy S, Labarca G, Rodriguez M, et al. Concomitant tracheal and subcutaneous glomus tumor: case report and review of the literature. Respir Med Case Rep 2015;16:81–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Cocker J, Messaoudi N, Waelput W, et al. Intrapulmonary glomus tumor in a young woman. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008; 7:1191–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Folpe AL, Brems Legius E.. Glomus tumours. In: Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F, eds. World Health Organization classification of tumours. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone, fourth ed., Lyon, France: IARC, 2013, pp. 116–117 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oide T, Yasufuku K, Shibuya K, et al. Primary pulmonary glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential: a case report with literature review focusing on current concepts of malignancy grade estimation. Respir Med Case Rep 2016; 19:143–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]