Abstract

Background

The Xq22.2 q23 is a complex genomic region which includes the genes MID2 and PLP1 associated with FG syndrome 5 and Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease, respectively. There is limited information regarding the clinical outcomes observed in patients with deletions within this region.

Methods

We report on a male infant with intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) who developed head titubation and spasticity during his postnatal hospital course.

Results

Chromosome microarray revealed a 6.7 Mb interstitial duplication of Xq22.2q22.3. Fluorescence in situ hybridization showed that the patient's mother also possessed the identical duplication in the Xq22.3q22.3 region. Among the 34 OMIM genes in this interval, the duplication of the PLP1 (OMIM# 300401) and MID2 (OMIM# 300204) appears to be the most significant contributors to the patient's clinical features. Mutations and duplications of PLP1 are associated with X‐linked recessive Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease (PMD). A single case of a Xq22.3 duplication including the MID2 has been reported in boy with features of FG syndrome. However, our patient's clinical features are not consistent with the FG syndrome phenotype.

Conclusion

Our patient's clinical features appear to be influenced by the PLP1 duplication but the clinical effect of other dosage sensitive genes influencing brain development cannot be ruled out.

Keywords: FG syndrome, MID2, Opitz‐Kaveggia syndrome type 5, Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease, PLP1

A male infant with head titubation, pendular nystagmus, and spasticity was identified as having an Xq22.2Xq22.3 chromosome microdeletion on chromosome microarray. The deletion contains the PLP1 and MID2 OMIM genes. The patient's phenotypic features appear consistent with Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease.

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

MID1 and MID2 code for RBCC (RING‐finger, B‐boxes, and Coiled‐coil) proteins localized on chromosome Xp22 and Xq22, respectively. Mutations in MID1 have been associated with X‐linked Opitz syndrome patients, characterized by hypertelorism in addition to craniofacial changes, urogenital, laryngotracheal, and cardiac malformations (Li, Zhou, & Zou, 2016) A duplication in MID2 have been postulated to be associated with a single case of FG syndrome 5, a condition characterized with macrocephaly, relatively small ears, frontal hair upsweep fetal fingertip pads, and intellectual disability (Jehee et al., 2005). More recently a missense mutation in MID2 was identified as the cause for X‐linked intellectual disability associated with the dysmorphic facial features which overlap but are distinct from FG syndrome including elongated face, short philtrum, prominent forehead, large ears, and a squint (Geetha et al., 2014). The expression patterns similar to the craniofacial expression of Mid1 and Mid2 have been observed during embryonic mouse development, which adds to the complexity in delineation of clinical features which may be unique to MID1 or MID2 mutations (Li et al., 2016). We describe a male infant with an Xq22.2q22.3 duplication that contains the MID2. We review this patient's phenotypic features and discuss the dosage sensitivities of genes within the regions potentially contributing to this patient's phenotypic features.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

This patient was born at 38 weeks gestation to a 32‐year‐old gravida 1 para 0 female who had intermittent prenatal care and gestational diabetes treated with metformin and insulin. There is no history of maternal alcohol, drug usage, or cigarette smoking. Fetal ultrasound revealed intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR). Both parents had macrocephaly. The patient's mother and father had a head circumference of 62.8 cm (hair braided) and 59.8 cm, respectively. The baby was delivered via caesarean section for abnormal fetal heart tracings and had Apgar scores of 9195. Birth weight was 2,370 g (<3%), length was 43.5 cm (<3%), and head circumference was 32.5 cm (5%).

With respect to the family history, the patient's mother required help in high school with math and social studies, but graduated on time. She reports being able to read, write, and perform basic mathematics. She was able to answer all questions at her son's visit and checked appropriate review of system boxes. The mother's brother (maternal uncle to patient) has been living in a residential facility since early childhood. There is limited confirmed information but he is thought to have significant intellectual disability. The mother works as a full time personal care assistant in a nursing home. She does not have any visual or neurological dysfunction.

There is no known maternal family history of birth defects, autism, or seizures.

Early in the NICU course, the patient exhibited some salient physical features including pendular nystagmus, mild micrognathia, small jaw, and head titubation.

Initially he was breast fed and soon was noted to be hypoglycemic with a blood glucose of 30 mg/dl. He was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit and received intravenous fluids with 10% dextrose (D10). He was successfully weaned off the fluids by day of life 3 and continued to feed on formula with normoglycemia and was switched to Pregestimil formula later.

On day of life 2, he was noticed to have acholic stools. Further diagnostic workup revealed elevated direct bilirubin of 2.4 and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 120. Liver ultrasound revealed a very small gall bladder. Due to the presence of direct hyperbilirubinemia, an infectious workup including urine CMV, toxoplasma antibodies, HIV, Hepatitis B and C, HSV, and CSF HSV, enterovirus was performed with negative test results.

On day of life 10, his oral feeding declined which necessitated placing an NG tube. A repeat ultrasound showed a very contracted gall bladder with a relatively thick wall and a diminutive size of the common bile duct which was concerning for biliary atresia. Head ultrasound and brain MRI were both normal. Chest x‐ray was negative for butterfly vertebrae or other spinal defects. EKG showed evidence of right atrial enlargement. Echocardiogram showed a small secundum atrial septum defect with left to right shunt. A pH probe study and upper GI study was normal with no evidence of malrotation. Ceruloplasmin level was 15.8 mg/dl. Alpha‐1 antitrypsin level was normal. Alpha‐1 antitrypsin Pi phenotype was MM (normal). Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan (HIDA) at day of life 30 showed poor hepatocellular extraction and no definite excretion into the biliary tree or small bowel at the end of 24 hr (no biliary flow). Autoimmune hepatitis panel was negative. Next generation sequencing jaundice panel showed no pathogenic mutations in ABCB4, ABCB11, ATP8B1, JAG1, and TJP2. G‐tube placement and liver biopsy were performed which showed cholestatic hepatitis with giant cell transformation, compatible with neonatal hepatitis. Cholangiogram showed a normal gall bladder. Renal ultrasound was normal. He was also noted to have metabolic acidosis with a bicarbonate of 16 mmol/L and was started on sodium carbonate supplementation. An amino acid quantitative profile was unremarkable. His initial and repeat newborn screen was normal. The etiologies for the patient's elevated liver function tests and metabolic acidosis were not identified.

SNP microarray analysis was performed using Affymetrix CytoScan Dx microarray. This microarray contains over 2.69 million probes, including 1.9 million unique non‐polymorphic probes and 740,000 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) probes. The average inter‐probe distance is 1,148 base pairs. Thresholds for genome‐wide screening set at >500 kb for gains and >200 kb for losses. The SNP microarray also detects the regions of homozygosity (ROH) which potentially increases the risk for autosomal recessive disorders.

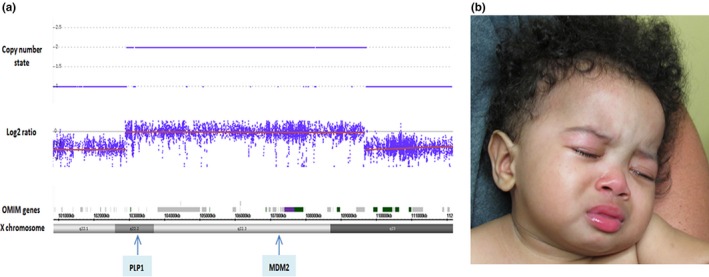

This microarray analysis revealed a 6.7 Mb interstitial duplication of Xq22.2q23; arr[hg19] Xq22.2q23 (102,890,822–109,572,085) × 2. (Figure 1a) This duplication interval included 34 OMIM annotated genes including PLP1 and MID2 (Table 1). Of note, mutations, deletions, and duplications of the PLP1 are associated with X‐linked recessive (XLR) Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease (OMIM: 312080); and mutations of MID2 is associated with XLT mental retardation (OMIM: 300928). A single case of a Xq22.3 duplication including the MID2 has been reported in boy with features of FG syndrome. Duplication in MID2 may contribute to FG syndrome 5.

Figure 1.

(a) Patient at 10 months of age with broad forehead, flat nasal bridge, and anteverted nares (b) SNP array showing a 6.7 Mb interstitial duplication on X chromosome at Xq22.2q23 of this male patient, where PLP1 and MID2 and other 32 OMIM annotated genes are in duplicated interval

Table 1.

OMIM genes in Xq22.2q22.3 duplication region

| Gene | OMIM number | Function/disease |

|---|---|---|

| MORF4L2 | 300409 | Protein which is declined in normal senescent cells (Bertram et al., 1999) |

| PLP1 | 300401 | Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease (Diehl, Schaich, Budzinski, & Stoffel, 1986) |

| TMSB15B | 301011 | Member of the thymosin‐beta family of actin‐binding molecules which deregulate motility in prostate cells (Bao et al., 1996) |

| RAB9B | 300285 | Regulated intercellular vesicle trafficking (Seki et al., 2000) |

| H2BFWT | 300507 | Interacts with DNA histones (Churikov et al., 2004) |

| SLC25A53 | 300941 | Inner mitochondrial membrane transporter (Palmieri, 2013) |

| ESX1 | 300154 | Imprinted gene involved in placental morphogenesis, located on X chromosome‐fetal growth (Li & Behringer, 1998) |

| IL1RAPL2 | 300277 | IL1Receptor (Sana, Debets, Timans, Bazan, & Kastelein, 2000) |

| TEX13A | 300312 | Testis expressed gene (Wang, McCarrey, Yang, & Page, 2001) |

| NRK | 300791 | Has activity against myelin basic protein (Nakano, Yamauchi, Nakagawa, Itoh, & Kitamura, 2000) |

| SERPINA7 | 314200 | Act at inflammatory sites and release thyroid binding globulin (TBG) (Jirasakuldech et al., 2000) |

| RNF128 | 300439 | Functions as E3 ubiquitin ligase (Anandasabapathy et al., 2003) |

| TBC1D8B | 301027 | Tre2‐Bub2‐Cdc16 (TBC) domain family protein that involved with cellular recycling processes and is expressed in human podocytes. Mutations associated with nephrotic syndrome 20 (Dorval et al., 2019) |

| RIPPLY1 | 300575 | Expressed in anterior presomitic mesoderm and somites of zebrafish (Kawamura et al., 2005) |

| CLDN2 | 300520 | Regulates tissue‐specific properties of tight junctions (Sakaguchi et al., 2002) |

| PRPS1 | 311850 |

Arts (cognitive impairment, hypotonia, ataxia, hearing impairment, and optic atrophy), Charcot Marie Tooth, X‐linked deafness Purine and pyrimidine synthesis (Roessler et al., 1990) |

| MORC4 | 300970 | Zinc finger proteins with presently unknown function (Liggins et al., 2007) |

| PIH1D3 | Involved in cytoplasm assembly of axonemal dynein; Mutations associated with X‐linked primary ciliary dyskinesia 36 (Paff et al., 2017) | |

| MYCL2 | 310310 | Has DNA sequence homology to MYC family of proto‐oncogenes (Morton et al., 1989) |

| FRMPD3 | 301005 | Protein expressed in expression in adult and fetal brain, adult spinal cord, and ovary. Function unknown (Nagase, Nakayama, Nakajima, Kikuno, & Ohara, 2001) |

| PRPS1 | 300681 | Gout associated with increased levels of phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase (Roessler et al., 1993). Allelic disorders include X‐linked recessive Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth Disease 5 and X‐linked sensorineural hearing loss. |

| TSC22D3 | 300506 | Modulates T‐lymphocyte response (Ayroldi et al., 2001) |

| MID2 | 300204 | Opitz FG syndrome Type 5 (Buchner et al., 1999) |

| TEX13B | 300313 | Testis‐expressed gene (Wang et al., 2001) |

| VSIG1 | 300620 | Junction adhesional molecule (Scanlan et al., 2006) |

| ATG4A | 300663 | Cysteine protease involved in autophagy (Mariño et al., 2003) |

| COL4A6 | 303631 | X‐linked deafness (Rost et al., 2014) |

| COL4A5 | 303630 | Alport hereditary nephritis (Lemmink, Schröder, Monnens, & Smeets, 1997) |

| AMMECR1 | 300195 | Gene member of contiguous gene complex AMME (Alport syndrome, mental retardation, midface hypoplasia, and elliptocytosis) (Meloni et al., 2002). Genes in this region include COL4A5 (303630) and FACL4 (300157) (Andreoletti et al., 2017) |

| IRS4 | 300904 | Tyrosine phosphorylated in response to insulin and IGF1 (Fantin et al., 1998) |

| GUCY2F | 300041 | Expressed largely in photoreceptors (Yang, Fülle, & Garbers, 1996) Candidate for X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa |

| NXT20 | 300320 | RNA export factor and binds to nucleus pore‐associated proteins NXF1 and NXF2 (Herold et al., 2000) |

| KCNE1L | 300328 | Shares 56% homology with potassium channel KCNE1 and deleted in AMME (Alport syndrome, mental retardation, midface hypoplasia, and elliptocytosis) (Meloni et al., 2002) |

| ACSL4 | 300157 | X‐chromosome‐imprinted regulator of placental development in mice (Fohn & Behringer, 2001) |

Confirmatory FISH analyses were performed on parents’ peripheral blood lymphocytes using standard procedures (Rooney, 2001). The BAC clone RP11‐1‐1J13, which was within the duplication interval of the proband, was selected for the probe. DNA isolated from this BAC clone and labeled directly with fluorochrome conjugated‐dUTP by nick translation (Vysis, Downer Grove, IL). The probe was hybridized to metaphase spreads which were prepared from the parents derived lymphocytes. Chromosomes were visualized by counterstaining with DAPI.

Maternal blood FISH analysis revealed the duplication of this region (Rooney, 2001). This is consistent with maternal transmission of this duplication to the male proband.

The patient returned for follow up at 10 months of age. The head titubations and nystagmus were no longer present. He was exclusively G‐tube fed and had delayed milestones. Physical examination at 10 months (Figure 1b) was significant when length was 58.5 cm (<3%; 50% for 8 weeks); weight was 4.9 kg (<3% 50% for 6 weeks); and head circumference was 44 cm (8%). There was relative macrocephaly with bitemporal narrowing and a prominent forehead. The anterior fontanelle was closed. The palpebral fissures were horizontal and there was absence of nystagmus. Outer canthal distance measured 6.3 cm (3%–25%), inner canthal distance measured 2.2 cm (3%–25%), and right and left palpebral fissure measured 2.1 cm. The calculated interpupillary distance was 4.1 cm (3%–25%). Right and left pinna measured 4.7 cm (approximately 50%) and the left outer pinna was slightly irregular. The bridge of the nose was flat and the nasal tip was depressed. There was anteversion of nares. The philtrum was grooved and measured 7 mm. The hairline appeared to be slightly low. Nipples were spaced normally. There was no murmur on auscultation. A gastrostomy tube was present on the abdomen.

There were tri‐radiate palmar creases. Dimples were evident on the knuckles. The right second toe overlapped the third toe and the third toe over the fourth toe. The left first toe overlapped the second toe. The penis was normal and both testes were descended. The anus was normally positioned. Neurologic examination was significant for decreased truncal tone and increased tone in the extremities. There were brisk deep tendon reflexes.

At age 3, the patient was able to hold an object placed in hand but unable to grab or transfer. He was able to roll with assistance. If placed in a seated position, he was able to lean to the side. He was using a standing device at home. He was able to coo but did not babble. He reportably likes music and will cry if his favorite show is turned off. He was receiving speech, physical and occupational therapy, and has nursing care.

At age 3, his length was 81.9 cm (0%, 50% = 1.5 years), weight was 11.2 kg (0%), and head circumference was 47.8 (13%). He had bifrontal narrowing. Palpebral fissures were neutral. There was no nystagmus but strabismus was evident. There was no ptosis or lid eversion. Calculated interpupillary distance was 5.8 cm (>97%) Ears were normally positioned and formed. Knee contractures were present. Hands deviated laterally. Distal phalanges were tapered. Marked hypotonia was present. Deep tendon reflexes were very brisk (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient at 3 years of age

3. DISCUSSION

We describe a male infant with a maternally inherited Xq22.2q22.3 duplication containing the PLP1 and MID2. This child has clinical features that appear to be influenced by PLP1 duplication although the contribution of other dosage sensitive genes within the region cannot be ruled out. His mother's neurocognitive phenotype is less clear and both parents have macrocephaly. Thus, both the MID2 duplication and other familial factors may contribute to our patient's macrocephaly.

Table 1 illustrates the OMIM genes that are present in the Xq22.2 q23 (102,890,822–109,572,085) region. Only duplications of PLP1 and MID2 are associated with known clinical disorders which potentially overlap with our patient's clinical features.

Proteolipid protein (PLP‐1)‐related CNS disorders include many disorders including PMD and Spastic paraplegia 2 (SPG‐2). PMD is an X‐linked recessive hypomyelinative leukodystrophy presenting with nystagmus, spastic quadriplegia, ataxia, and developmental delay usually in infancy or early childhood. Most of these manifestations including nystagmus and mild spasticity were noted in our patient. PMD can present in different forms including severe (connatal) PMD which presents in infancy with pendular nystagmus, hypotonia and pharyngeal weakness. In childhood, affected children develop short stature, poor weight gain, spasticity and developmental delays. Patients with classic PMD present with nystagmus in late infancy, are hypotonic and develop titubation and tremors of head and neck with spastic quadriparesis in the first few years of life. A transitional form also exists between the connatal and the classic PMD forms.

First described by Opitz and Kaveggia, FG syndrome (Opitz & Kaveggia, 1974) is an X‐linked multiple congenital anomalies (MCA) syndrome. FG syndrome has been mapped to five distinct loci: FGS1 (OMIM305450) encoded by MED12 on Xq13 (Risheg et al., 2007); FGS2 (OMIM 300321) localized to Xq28, caused by FLNA mutations (Unger et al., 2007); FGS3 (OMIM 300406) mapped to Xp22.3 (Dessay et al., 2002); and mutations in CASK at Xp11 are responsible for FGS4 (OMIM300422) (Piluso et al., 2009).

Jehee et al. (2005) described a male child with clinical features of FG syndrome including trigonocephaly, upslanting palpebral fissures, depressed nasal bridge, anteverted nares, long philtrum, diastema of upper central incisors, strabismus, and hypospadias. He had hypotonia and developmental delay and died at 4 years of age due to generalized infection and multiple organ failure. A microduplication of approximately 4 Mb was identified at Xq22.3 and included the MID2. MID2 is highly homologous to MID1, a gene is known to be mutated in Opitz G/BBB syndrome, and thus MID2 was proposed as a candidate gene for FG syndrome 5.

PLP1 tandem duplications are postulated to be mediated by homologous and nonhomologous recombination mechanism through which there is repair of a double‐stranded DNA breakage event by one‐sided homologous strand sister chromatid invasion followed by DNA synthesis and subsequent joining with the other end of the break through a nonhomologous mechanism (Woodward et al., 2005). The utilization of capture and single molecule real‐time sequencing (cap‐SMRT‐seq) has revealed three groups of copy number variants (CNVs) including (a) small template insertions with insertions above 20 bp; (b) intra CNV rearrangements; (c) inter‐chromosomal and interlocus rearrangements (Zhang et al., 2017). The clinical phenotype associated with PLP1 duplications does not appear to be mediated by size of the duplication as patients with large size PLP1 duplications had relatively mild clinical features (Regis et al., 2008). Additional brain expressed genes in the PLP1 genomic region including SERPINA7, FRMD3, AMMECR1, ILRAPL2, CLDN2, TSC22D3, and PRPS1 may contribute to previously reported and our patient's clinical features, although it is difficult to determine which gene(s) apart from duplicated PLP1 contribute to our patient's clinical phenotype (Carvalho et al., 2012; Regis et al., 2008). ACSL4 may contribute to the patient's IUGR, given its association with placental development (Fohn & Behringer, 2001). As our patient and his mother do not have hearing loss or nephritis, the contributions of duplicated COL4A6 and COL4A5 are of minimal significance. We summarize our patient's clinical features and compare them to PLP‐1 conatal and classic types in Table 2 and FG syndrome. Our patient has clinical features that appear to be more closely aligned with PLP‐1 conatal.

Table 2.

Comparison of Patient clinical features to features described by Jehee et al. and PLP‐1 related phenotypes

| Clinical feature | Patient | Jehee et al. (2005) | PLP‐1‐related phenotypes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connatal type | Classic type | |||

| Gestation | 38 weeks | 32 weeks | N/A | N/A |

| Birth length | 43.5 cm (<3%) | 38 cm (<3%) | N/A | N/A |

| Birth weight | 2,370 g (<3%) | 1,800 g (50%) | N/A | N/A |

| Head circumference | 32.5 cm (5%) | NR | N/A | N/A |

| Craniofacial | Micrognathia | Trigonocephaly | ||

| Muscle Tone | Hypotonia | Hypotonia | Hypotonia | Hypotonia |

| Pendular nystagmus | Present initially but disappeared in a few months | Unknown (not mentioned in the case report) | Present | Present |

| Pharyngeal weakness/stridor | Absent | Unknown | Present | Absent |

| Ataxia | Absent | Not described | Absent | Present |

| Cognitive impairment | Present | Present | Present | Less severe |

| GI Symptoms | Direct hyperbilirubinemia (unknown cause), G‐tube dependent for nutrition | Severe constipation | Dysphagia more prevalent, constipation | Less prevalent |

| Significant Maternal history |

Intellectual disability, Gestational diabetes, Identical duplication of Xq22.2q22.3 |

Severe anemia | N/A | N/A |

| Genetics | Duplication of Xq22.2q22.3 | Duplication in Xq22.3 | Duplication in Xq22 including PLP1 | Duplication in Xq22 including PLP1 |

| Brain MRI | Normal in infancy | Unknown | Diffuse leukoencephalopathy – noted after the age of 2 years | Diffuse leukoencephalopathy – noted after the age of 2 years |

| Death | Alive | At age 4 years secondary to multi‐organ failure | Infancy to 3rd decade | Can survive up to 3rd−7th decade |

Abbreviation: NR, not recorded.

Some females who carry Xq22 PLP1 duplications have exhibited failure to thrive, developmental delay, dysmorphic features, and abnormal MRI findings which may be attributed to altered X chromosome inactivation in brain cells, dosage‐sensitive genes escaping X chromosome inactivation and depending on the size of the Xq22 deletion, genes which when duplicated exhibiting altered expression patterns, and dosage‐sensitive genes which escape X chromosome inactivation (Carvalho et al., 2012). It is difficult for us to determine if the PLP1 duplication has any subtle effects on the patient's mother as she has not had a neuropsychiatric evaluation and a brain MRI.

The patient described in this communication has a duplication in the Xq22.3 region and displays clinical features influenced by the PLP1 duplication. The effect of the MID2 duplication and other genes in this interval on the patient's overall phenotype appears less evident.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no financial or otherwise relevant conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTION

Swati R. Chanchani performed organization of clinical data, literature research and writing; Hongyan Xie and Gurbax Sekhon performed chromosome microarray and interpretation and assisted with writing of manuscript; Ana M. Melikishvili assisted with gathering and review of clinical data; Harpreet Pall assisted with analysis of clinical information and writing; Sue Moyer Harasink assisted with gathering and analysis of clinical information; Philip F. Giampietro is the corresponding author.

Chanchani SR, Xie H, Sekhon G, et al. A male infant with Xq22.2q22.3 duplication containing PLP1 and MID2 . Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1078 10.1002/mgg3.1078

REFERENCES

- Anandasabapathy, N. , Ford, G. S. , Bloom, D. , Holness, C. , Paragas, V. , Seroogy, C. , … Soares, L. (2003). GRAIL: An E3 ubiquitin ligase that inhibits cytokine gene transcription is expressed in anergic CD4+ T cells. Immunity, 18(4), 535–547. 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreoletti, G. , Seaby, E. G. , Dewing, J. M. , O'Kelly, I. , Lachlan, K. , Gilbert, R. D. , & Ennis, S. (2017). A single point mutation causes developmental delay, midface hypoplasia and elliptocytosis. Journal of Medical Genetics, 54(4), 269–277. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayroldi, E. , Migliorati, G. , Bruscoli, S. , Marchetti, C. , Zollo, O. , Cannarile, L. , … Riccardi, C. (2001). Modulation of T‐cell activation by the glucocorticoid‐induced leucine zipper factor via inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB. Blood, 98(3), 743–753. 10.1182/blood.v98.3.743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao, L. , Loda, M. , Janmey, P. A. , Stewart, R. , Anand‐Apte, B. , & Zetter, B. R. (1996). Thymosin beta 15: A novel regulator of tumor cell motility upregulated in metastatic prostate cancer. Nature Medicine, 2(12), 1322–1328. 10.1038/nm1296-1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, M. J. , Bérubé, N. G. , Hang‐Swanson, X. , Ran, Q. , Leung, J. K. , Bryce, S. , … Pereira‐Smith, O. M. (1999). Identification of a gene that reverses the immortal phenotype of a subset of cells and is a member of a novel family of transcription factor‐like genes. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 19(2), 1479–1485. 10.1128/MCB.19.2.1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner, G. , Montini, E. , Andolfi, G. , Quaderi, N. , Cainarca, S. , Messali, S. , … Franco, B. (1999). MID2, a homologue of the Opitz syndrome gene MID1: Similarities in subcellular localization and differences in expression during development. Human Molecular Genetics, 8(8), 1397–1407. 10.1093/hmg/8.8.1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C. M. , Bartnik, M. , Pehlivan, D. , Fang, P. , Shen, J. , & Lupski, J. R. (2012). Evidence for disease penetrance relating to CNV size: Pelizaeus‐Merzbacher disease and manifesting carriers with a familial 11 Mb duplication at Xq22. Clinical Genetics, 81(6), 532–541. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01716.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churikov, D. , Siino, J. , Svetlova, M. , Zhang, K. , Gineitis, A. , Morton Bradbury, E. , & Zalensky, A. (2004). Novel human testis‐specific histone H2B encoded by the interrupted gene on the X chromosome. Genomics, 84(4), 745–756. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessay, S. , Moizard, M. P. , Gilardi, J. L. , Opitz, J. M. , Middleton‐Price, H. , Pembrey, M. , … Briault, S. (2002). FG syndrome: Linkage analysis in two families supporting a new gene localization at Xp22.3 [FGS3]. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 112(1), 6–11. 10.1002/ajmg.10546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, H. J. , Schaich, M. , Budzinski, R. M. , & Stoffel, W. (1986). Individual exons encode the integral membrane domains of human myelin proteolipid protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 83(24), 9807–9811. 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorval, G. , Kuzmuk, V. , Gribouval, O. , Welsh, G. I. , Bierzynska, A. , Schmitt, A. , … Antignac, C. (2019). TBC1D8B Loss‐of‐function mutations lead to X‐linked nephrotic syndrome via defective trafficking pathways. American Journal of Human Genetics, 104(2), 348–355. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantin, V. R. , Sparling, J. D. , Slot, J. W. , Keller, S. R. , Lienhard, G. E. , & Lavan, B. E. (1998). Characterization of insulin receptor substrate 4 in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273(17), 10726–10732. 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fohn, L. E. , & Behringer, R. R. (2001). ESX1L, a novel X chromosome‐linked human homeobox gene expressed in the placenta and testis. Genomics, 74(1), 105–108. 10.1006/geno.2001.6532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geetha, T. S. , Michealraj, K. A. , Kabra, M. , Kaur, G. , Juyal, R. C. , & Thelma, B. K. (2014). Targeted deep resequencing identifies MID2 mutation for X‐linked intellectual disability with varied disease severity in a large kindred from India. Human Mutation, 35(1), 41–44. 10.1002/humu.22453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold, A. , Suyama, M. , Rodrigues, J. P. , Braun, I. C. , Kutay, U. , Carmo‐Fonseca, M. , … Izaurralde, E. (2000). TAP (NXF1) belongs to a multigene family of putative RNA export factors with a conserved modular architecture. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 20(23), 8996–9008. 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8996-9008.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehee, F. S. , Rosenberg, C. , Krepischi‐Santos, A. C. , Kok, F. , Knijnenburg, J. , Froyen, G. , … Passos‐Bueno, M. R. (2005). An Xq22.3 duplication detected by comparative genomic hybridization microarray (Array‐CGH) defines a new locus (FGS5) for FG syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 139(3), 221–226. 10.1002/ajmg.a.30991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirasakuldech, B. , Schussler, G. C. , Yap, M. G. , Drew, H. , Josephson, A. , & Michl, J. (2000). A characteristic serpin cleavage product of thyroxine‐binding globulin appears in sepsis sera. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 85(11), 3996–3999. 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, A. , Koshida, S. , Hijikata, H. , Ohbayashi, A. , Kondoh, H. , & Takada, S. (2005). Groucho‐associated transcriptional repressor ripply1 is required for proper transition from the presomitic mesoderm to somites. Developmental Cell, 9(6), 735–744. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmink, H. H. , Schröder, C. H. , Monnens, L. A. , & Smeets, H. J. (1997). The clinical spectrum of type IV collagen mutations. Human Mutation, 9(6), 477–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. , Zhou, T. , & Zou, Y. (2016). Mid1/Mid2 expression in craniofacial development and a literature review of X‐linked opitz syndrome. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine, 4(1), 95–105. 10.1002/mgg3.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , & Behringer, R. R. (1998). Esx1 is an X‐chromosome‐imprinted regulator of placental development and fetal growth. Nature Genetics, 20(3), 309–311. 10.1038/3129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins, A. P. , Cooper, C. D. O. , Lawrie, C. H. , Brown, P. J. , Collins, G. P. , Hatton, C. S. , … Banham, A. H. (2007). MORC4, a novel member of the MORC family, is highly expressed in a subset of diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas. British Journal of Haematology, 138(4), 479–486. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06680.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariño, G. , Uría, J. A. , Puente, X. S. , Quesada, V. , Bordallo, J. , & López‐Otín, C. (2003). Human autophagins, a family of cysteine proteinases potentially implicated in cell degradation by autophagy. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(6), 3671–3678. 10.1074/jbc.M208247200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloni, I. , Vitelli, F. , Pucci, L. , Lowry, R. B. , Tonlorenzi, R. , Rossi, E. , … Renieri, A. (2002). Alport syndrome and mental retardation: Clinical and genetic dissection of the contiguous gene deletion syndrome in Xq22.3 (ATS‐MR). Journal of Medical Genetics, 39(5), 359–365. 10.1136/jmg.39.5.359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton, C. C. , Nussenzweig, M. C. , Sousa, R. , Sorenson, G. D. , Pettengill, O. S. , & Shows, T. B. (1989). Mapping and characterization of an X‐linked processed gene related to MYCL1 . Genomics, 4(3), 367–375. 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90344-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase, T. , Nakayama, M. , Nakajima, D. , Kikuno, R. , & Ohara, O. (2001). Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XX. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Research, 8(2), 85–95. 10.1093/dnares/8.2.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, K. , Yamauchi, J. , Nakagawa, K. , Itoh, H. , & Kitamura, N. (2000). NESK, a member of the germinal center kinase family that activates the c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase pathway and is expressed during the late stages of embryogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 275(27), 20533–20539. 10.1074/jbc.M001009200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz, J. M. , & Kaveggia, E. G. (1974). Studies of malformation syndromes of man 33: The FG syndrome. An X‐linked recessive syndrome of multiple congenital anomalies and mental retardation. Zeitschrift Für Kinderheilkunde, 117(1), 1–18. 10.1007/bf00439020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paff, T. , Loges, N. T. , Aprea, I. , Wu, K. , Bakey, Z. , Haarman, E. G. , … Micha, D. (2017). Mutations in PIH1D3 cause X‐linked primary ciliary dyskinesia with outer and inner dynein arm defects. American Journal of Human Genetics, 100(1), 160–168. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, F. (2013). The mitochondrial transporter family SLC25: Identification, properties and physiopathology. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 34(2–3), 465–484. 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piluso, G. , D'Amico, F. , Saccone, V. , Bismuto, E. , Rotundo, I. L. , Di Domenico, M. , … Nigro, V. (2009). A missense mutation in CASK causes FG syndrome in an Italian family. American Journal of Human Genetics, 84(2), 162–177. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regis, S. , Biancheri, R. , Bertini, E. , Burlina, A. , Lualdi, S. , Bianco, M. G. , … Filocamo, M. (2008). Genotype‐phenotype correlation in five Pelizaeus‐Merzbacher disease patients with PLP1 gene duplications. Clinical Genetics, 73(3), 279–287. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00961.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risheg, H. , Graham, J. M. , Clark, R. D. , Rogers, R. C. , Opitz, J. M. , Moeschler, J. B. , … Friez, M. J. (2007). A recurrent mutation in MED12 leading to R961W causes Opitz‐Kaveggia syndrome. Nature Genetics, 39(4), 451–453. 10.1038/ng1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler, B. J. , Bell, G. , Heidler, S. , Seino, S. , Becker, M. , & Palella, T. D. (1990). Cloning of two distinct copies of human phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase cDNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 18(1), 193 10.1093/nar/18.1.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler, B. J. , Nosal, J. M. , Smith, P. R. , Heidler, S. A. , Palella, T. D. , Switzer, R. L. , & Becker, M. A. (1993). Human X‐linked phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase superactivity is associated with distinct point mutations in the PRPS1 gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 268(35), 26476–26481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, D. E. (2001). Human cytogenetics: Constitutional analysis; a practical approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, S. , Bach, E. , Neuner, C. , Nanda, I. , Dysek, S. , Bittner, R. E. , … Kunstmann, E. (2014). Novel form of X‐linked nonsyndromic hearing loss with cochlear malformation caused by a mutation in the type IV collagen gene COL4A6. European Journal of Human Genetics, 22(2), 208–215. 10.1038/ejhg.2013.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi, T. , Gu, X. , Golden, H. M. , Suh, E. , Rhoads, D. B. , & Reinecker, H. C. (2002). Cloning of the human claudin‐2 5'‐flanking region revealed a TATA‐less promoter with conserved binding sites in mouse and human for caudal‐related homeodomain proteins and hepatocyte nuclear factor‐1alpha. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277(24), 21361–21370. 10.1074/jbc.M110261200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sana, T. R. , Debets, R. , Timans, J. C. , Bazan, J. F. , & Kastelein, R. A. (2000). Computational identification, cloning, and characterization of IL‐1R9, a novel interleukin‐1 receptor‐like gene encoded over an unusually large interval of human chromosome Xq22.2‐q22.3. Genomics, 69(2), 252–262. 10.1006/geno.2000.6328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, M. J. , Ritter, G. , Yin, B. W. , Williams, C. , Cohen, L. S. , Coplan, K. A. , … Jungbluth, A. A. (2006). Glycoprotein A34, a novel target for antibody‐based cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunology, 6, 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki, N. , Azuma, T. , Yoshikawa, T. , Masuho, Y. , Muramatsu, M. , & Saito, T. (2000). cDNA cloning of a new member of the Ras superfamily, RAB9‐like, on the human chromosome Xq22.1‐q22.3 region. Journal of Human Genetics, 45(5), 318–322. 10.1007/s100380070025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger, S. , Mainberger, A. , Spitz, C. , Bähr, A. , Zeschnigk, C. , Zabel, B. , … Morris‐Rosendahl, D. J. (2007). Filamin A mutation is one cause of FG syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 143A(16), 1876–1879. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. J. , McCarrey, J. R. , Yang, F. , & Page, D. C. (2001). An abundance of X‐linked genes expressed in spermatogonia. Nature Genetics, 27(4), 422–426. 10.1038/86927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, K. J. , Cundall, M. , Sperle, K. , Sistermans, E. A. , Ross, M. , Howell, G. , … Hobson, G. M. (2005). Heterogeneous duplications in patients with Pelizaeus‐Merzbacher disease suggest a mechanism of coupled homologous and nonhomologous recombination. American Journal of Human Genetics, 77(6), 966–987. 10.1086/498048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R. B. , Fülle, H. J. , & Garbers, D. L. (1996). Chromosomal localization and genomic organization of genes encoding guanylyl cyclase receptors expressed in olfactory sensory neurons and retina. Genomics, 31(3), 367–372. 10.1006/geno.1996.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. , Wang, J. , Zhang, C. , Li, D. , Carvalho, C. M. B. , Ji, H. , … Jiang, Y. (2017). Efficient CNV breakpoint analysis reveals unexpected structural complexity and correlation of dosage‐sensitive genes with clinical severity in genomic disorders. Human Molecular Genetics, 26(10), 1927–1941. 10.1093/hmg/ddx102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]