Abstract

This study compares statewide cardiac surgery outcome reporting in California and New York with contemporary performance.

Statewide cardiac surgery outcome reporting is intended to inform patient and clinician decisions. However, on the day of their release, they often are reporting performances from several years prior.1,2 Past performance may inform quality,3,4,5 and shorter time lag improves the relevance of the report,4 but publication continues to lag by several years. We used California and New York data to compare what was reported at the time of public report card release with the contemporary performance at that time (based on subsequent public reports).

Methods

We used data on isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) from publicly available statewide cardiac surgery outcome reports in New York and California.1,2 We analyzed cases performed between 2013 and 2016 (2016 data are the latest published for both states). Of 164 centers, we included centers performing at least 1 isolated CABG per year between 2013 and 2016. Because the data were publicly available, the Yale institutional review board waived approval and the need for patient consent.

We used observed-to-expected (O-E) operative mortality ratio as the standardized metric of risk-adjusted outcome.1,2 Observed-to-expected ratio is defined as the ratio of observed and expected mortality rates for each center. Expected mortality is calculated from state-specific risk models that accounted for patient factors.

The 2013 performance was made available in 2016, and we plotted O-E ratios in 2013 and 2016 to visualize the differences. We categorized centers by extreme outcomes (O-E ratio >2 or <0.5) and nonextreme outcomes (O-E ratio 0.5-2), because extreme outcomes likely inform choices. We defined the O-E ratio thresholds a priori to facilitate interpretation of the frequency of O-E ratio changes. Values were reported in mean and standard deviation. Analyses were conducted using Python, version 3.6 (Python Software Foundation).

Results

We included 119 California centers and 36 New York centers. Mean (SD) center-level annual case volume was 127 (107) (Table). In 2013, 22 centers (14%) had O-E ratios greater than two, 92 centers (59%) had O-E ratios between 0.5 and 2, and 41 centers (26%) had O-E ratios less than 0.5.

Table. Center-Level Annual Case Volume.

| Center Characteristics | Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 155) | California (n = 119) | New York (n = 36) | |

| Annual case volume | 127 (107) | 60 (59) | 220 (118) |

| O-E ratio change in 2013-2016a | 1.0 (1.7) | 1.1 (2.2) | 0.7 (0.6) |

| Centers with O-E ratio | |||

| >2.0 in 2013 | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.4 (1.2) |

| 0.5-2.0 in 2013 | 0.6 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.4) |

| <0.5 in 2013 | 1.6 (3.6) | 1.7 (3.8) | 1.0 (1.0) |

Abbreviation: O-E ratio, observed-to-expected ratio.

Absolute change between 2013 and 2016.

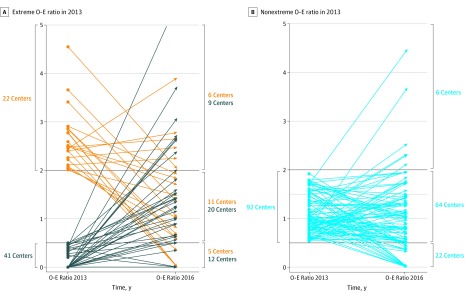

During the 3-year time lag, center O-E ratios changed by a mean (SD) of 1.0 (1.7). Of the 41 centers that had less than half the expected mortality in 2013, only 12 centers (29%) continued to have less than half the expected mortality, and 9 centers (22%) had more than twice the expected mortality in 2016. Of the 22 centers that had more than twice the expected mortality in 2013, only 6 centers (27%) continued to have more than twice the expected mortality, and 5 centers (23%) had less than half the expected mortality in 2016 (Figure).

Figure. Changes in Observed-to-Expected (O-E) Ratios in the Year of Measurement and Actual Performance by the Time of Report Publication.

The figure demonstrates changes in O-E ratio between 2013 and 2016 for each center. In panel A, O-E ratio changes for centers with O-E ratio greater than 2 in 2013 are displayed in orange and O-E ratio less than 0.5 in 2013 are displayed in dark blue. In panel B, O-E ratio changes for centers with O-E ratio between 0.5 and 2 in 2013 are displayed. Number of centers in corresponding O-E ratio strata in 2013 (left axis) and 2016 (right axis) are displayed.

Discussion

Patients who depend on the point estimates of 3-year-old data from these public reports could draw incorrect inferences about the current quality of their prospective clinicians. Hospital-level risk-adjusted surgical outcomes changed for many programs between the year of outcome measurement and when the report was published. Although a prior study4 showed that using 2-year instead of 3-year data better predicted current quality, we showed outcome disparities still exist. The change was more prominent in centers that had extreme outcomes in the year of outcome measurement, suggesting instability of estimates at extremes and regression to the mean.6 Consistent with our findings, only 1 of 155 centers had CABG mortality that was statistically significantly different in 2013.1,2

States reported that validating the data delayed the publication of reports.1 The process may be shortened with currently available digital platforms to facilitate data centralization and analysis, as done in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, for example. Bayesian methods may aid interpretation of statistical noise related to low volume. For public reporting to have relevance to decision-making and quality improvement, we must collect, analyze, and disseminate information in near-real time.

References

- 1.New York State Department of Health Cardiovascular disease data and statistics. https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/diseases/cardiovascular/. Published 2019. Accessed July 1, 2019.

- 2.California Hospital Performance Ratings for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Surgery Coronary artery bypass graft outcomes reports. https://oshpd.ca.gov/data-and-reports/healthcare-quality/cabg-reports/. Published 2019. Accessed July 1, 2019.

- 3.Glance LG, Dick AW, Osler TM, Kellermann AL. Hospital quality: does past performance predict future performance? JAMA Surg. 2014;149(1):16-17. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glance LG, Dick AW, Mukamel DB, Li Y, Osler TM. How well do hospital mortality rates reported in the New York State CABG report card predict subsequent hospital performance? Med Care. 2010;48(5):466-471. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d568f7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB, Staiger DO. Operative mortality and procedure volume as predictors of subsequent hospital performance. Ann Surg. 2006;243(3):411-417. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201800.45264.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimick JB, Welch HG. The zero mortality paradox in surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(1):13-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]