Abstract

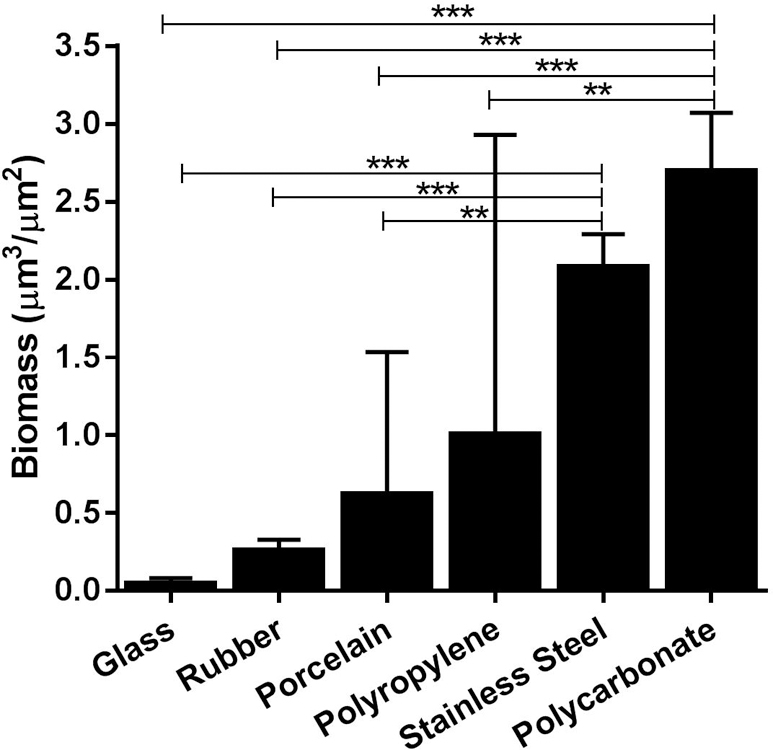

The human opportunistic pathogen, Acinetobacter baumannii, has the propensity to form biofilms and frequently causes medical device-related infections in hospitals. However, the physio-chemical properties of medical surfaces, in addition to bacterial surface properties, will affect colonization and biofilm development. The objective of this study was to compare the ability of A. baumannii to form biofilms on six different materials common to the hospital environment: glass, porcelain, stainless steel, rubber, polycarbonate plastic and polypropylene plastic. Biofilms were developed on material coupons in a CDC biofilm reactor. Biofilms were visualized and quantified using fluorescent staining and imaged using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and by direct viable cell counts. Image analysis of CLSM stacks indicated that the mean biomass values for biofilms grown on glass, rubber, porcelain, polypropylene, stainless steel and polycarbonate were 0.04, 0.26, 0.62, 1.00, 2.08 and 2.70 µm3/µm2 respectively. Polycarbonate developed statistically more biofilm mass than glass, rubber, porcelain and polypropylene. Viable cell counts data were in agreement with the CLSM-derived data. In conclusion, polycarbonate was the most accommodating surface for A. baumannii ATCC17978 to form biofilms while glass was least favorable. Alternatives to polycarbonate for use in medical and dental devices may need to be considered.

Keywords: Biofilms, Acinetobacter baumannii, medical device, infection control, environment, environmental surfaces

INTRODUCTION

A. baumannii can disseminate and persist in hospital environments, causing nosocomial outbreaks and serious disease in the critically ill (Towner 2009; Chen et al. 2015; Weber et al. 2015). Many of the infections caused by A. baumannii (ranging from urinary tract infections to ventilator-associated pneumonia) are associated with indwelling devices (Manchanda et al. 2010; Patel et al. 2014) due to the formation of biofilm on these surfaces. Biofilms of A. baumannii are found on the surfaces of many types of medical devices including urinary catheters, central lines, surgical drains, ventilation equipment, dental water lines, and cleaning equipment as well as on a variety of other surfaces in the hospital environment (Donlan and Costerton, 2002; Cohen et al. 2014; Patel et al. 2014).

Biofilms are a dynamic, heterogeneous community of microorganisms within a complex matrix of extrapolymeric substance that have integrated metabolic activities and produce sessile phenotypes markedly different from their planktonic counterparts (Sutherland 2001; Stoodley et al. 2002); (Hall-Stoodley and Stoodley 2005). A critical step for biofilm formation is for the pathogen to adhere to a surface. Cell-surface associated structures on the surface of A. baumannii can enhance attachment via pili, encoded by the csuA/BABCDE chaperone-usher pilus assembly operon (Tomaras et al. 2003), and there is evidence to suggest that the blaPER-1 gene also enhances substrate adhesion (Lee et al. 2008). In terms of surface chemistry, the physio-chemical properties of inanimate surfaces also play a key role in cell adhesion and biofilm development. Electrostatic forces, Lifshitz-van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic/hydrophilic forces positively or negatively influence microbial adhesion to a surface (Bos et al. 1999). Increased surface roughness can increase the hydrophobicity of the surface by effecting the surface contact angle (Patankar 2004). For example, Staphylococcus epidermidis has greater adhesion to hydrophobic surfaces compared to hydrophilic surfaces (Cerca et al. 2005).

A variety of material types are used in medical equipment and in the hospital setting. Polycarbonate, a durable, low-cost plastic that can undergo autoclave sterilization is found in a variety of medical devices including urinary catheters, gastrointestinal tubes, and cardiopulmonary bypass circuits, blood oxygenators and flood filters used in the bypass circuit (Duty et al. 2013). Mesh prosthetics are often composed of polypropylene (Byrd et al. 2011) and porcelain is commonly used in many implants and dental crowns (Schroder et al. 2011; Ren and Zhang 2014). Stainless steel makes up the majority of surgical equipment and rubber has a number of uses, particularly rubber seals, such as that used in disposable plastic syringes (Hamilton 1987). Cells of A. baumannii can persist on most of these inanimate surfaces (Wendt et al. 1997) but studies comparing A. baumannii biofilms across various surface types is lacking. A. baumannii biofilms have been demonstrated on a limited number of substrata such as glass (Vidal et al. 1996) and plastic surfaces (Tomaras et al. 2003). Thus, the aim of this study was to compare the ability of A. baumannii to form biofilm on six different material types: glass, porcelain, stainless steel, rubber, polycarbonate plastic and polypropylene plastic. Understanding the propensity for biofilm formation on various surfaces provides critical information to different parties for selecting low biofilm materials, which is essential for minimizing the risk of biofilm-associated infections.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Biofilm formation by A. baumannii ATCC17978 varies across substrata

The material substratum is an essential factor that contributes to the ability of a pathogen to adhere to and form biofilm on a surface (Brandao et al. 2015; Fernandez-Delgado et al. 2015);. Aside from cellular properties and pathogen adhesion mechanisms, variations in surface roughness, hydrophobicity and chemical structure can impede or promote a pathogens ability to attach and populate on that surface. To evaluate if variations between these surface types influenced the development of biofilms, the biofilms of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 were developed on disc coupons of glass, rubber, porcelain, polypropylene, stainless steel and polycarbonate in a CDC reactor for 4 days and the mean biomass values for biofilms grown on each surface type was determined using fluorescent staining and imaging by confocal laser scanning microscope (Figure 1). We did not anticipate that the rubber surface would absorb the stain, which made it difficult to distinguish the biomass from the background. Therefore, the biomass and live/dead ratio data obtained for rubber using microscopy is presented for reference only and the viable cell count data (which does not rely on microscopy) should be relied upon to estimate the biofilm biomass on rubber. We report that A. baumannii ATCC17978 can readily form biofilms on polycarbonate. Polycarbonate, a hydrophobic type of plastic, developed statistically more biofilm mass than glass, rubber, porcelain and polypropylene. We confirmed these biomass results by estimating the mean CFU cm−2 for the biofilms grown on each of the surfaces using a serial dilution method that is independent of CLSM. The mean viable cells on each surface type is presented in Figure 2 and corroborate the mean biomass values determined using the confocal microscope. The biofilms growing on polycarbonate had a statistically significantly higher CFU cm−2 compared to all other surface types. Our finding of high biofilm formation on polycarbonate is consistent with the finding of Brandao et al. who demonstrated that polycarbonate composite orthodontic brackets sustained the highest level of bacterial adhesion in the buccal cavity compared to metal and ceramic brackets (Brandao et al. 2015).

Figure 1:

Mean biomass of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 biofilms with standard deviations grown on selected material types. **P = 0·02, ***P < 0·009, One-way anova P = 0·008. Note: Biomass data for rubber are presented for reference only due to the absorption of stain by the rubber surface.

Figure 2:

Viable Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 cells on selected material types. ***P ≤ 0·001, One-Way Anova P = 0·004.

In contrast to polycarbonate, A. baumannii cells did not adhere to glass. On glass, which is a hydrophilic surface, A. baumannii weakly formed small, flat aggregates of biofilm. We found no statistically significant difference in biofilm mass on glass compared to porcelain and polypropylene, although higher biofilm mass was formed on these surfaces, which could also be visually seen (Figure 3). This is consistent with several other studies showing that biofilm formation by A. baumannii was less favorable on glass compared to plastic such as polystyrene, polypropylene and Teflon plastics (Tomaras et al. 2003; McQueary and Actis 2011) as well as polycarbonate (Pour et al. 2011). Surface roughness (Ra) measurements for glass, stainless steel and polycarbonate (only) were available from the supplier (BioSurface Technologies Corp., Bozeman, MT), which were 0.425, 20.20 and 50.95 µin, respectively. Recall that the mean biomass for these three surfaces was 0.043, 2.08 and 2.70 respectively. The increasing surface roughness and mean biomass, from glass to polycarbonate, suggests a positive trend between increased biofilm formation and rougher surfaces, although not statistically significant (Pearson correlation p value = 0.27).

Figure 3:

Live/Dead ratio of A. baumannii ATCC17978 biofilms grown on selected material types. *P = 0·01, **P ≤ 0·001, One-Way ANOVA P = 0·0002. n = number of replicates. Note: Live/dead ratio for rubber is presented for reference only due to the absorption of stain by the rubber surface.

We performed biofilm imaging using the CLSM for each material type and select images are shown in Figure 4. Differences in the formation of biofilm can be visually seen. Biofilms grown on polypropylene and porcelain displayed a flat architecture. Polycarbonate best supported biofilm growth followed by stainless steel, as evidenced by the formation of mushroom structures on these two surfaces (Figure 4). Stainless steel had statistically significantly more biofilm mass compared to porcelain and glass. We used a brushed stainless steel, which has a striated surface structure. While the high surface energy of stainless results in a more hydrophilic surface (Fernandez-Delgado et al. 2015), the roughness of the surface increases surface hydrophobicity (Patankar 2004), which may contribute to the increased adhesiveness of cells. The surface groves also increase the surface area and enhance microbial colonization. This may also account for the high live/dead ratio seen for stainless steel (Figure 3) as cells adhere within the grooves, forming a strong base onto which live cells attach and subsist (Figure 4). A qualitative comparison of microscan images with studies by Nan et al. who compared the biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus on stainless steel with copper treated stainless steel (Nan et al. 2015) and by Fernandez-Delgado et al. who evaluated the biofilms of P. mirabilis on stainless steel (Fernandez-Delgado et al. 2015) reveals similarity in biofilm development with regard to this metal.

Figure 4:

Confocal microscopy images of top and side views of A. baumannii ATCC17978 biofilms on glass, porcelain, stainless steel, polypropylene and polycarbonate.

Study limitations

We evaluated the biofilm forming ability of a single, clonal species of A. baumannii, which makes it difficult to generalize our results to other microorganisms. Additional studies using diverse species are needed. Different strains/isolates may have different abilities to form biofilms on the materials we tested and this will be the subject of future studies to determine if our conclusions can be generalized to other A. baumannii strains/isolates. In addition, biofilms are known to exist as mixed species in nature and mixtures of colonizing species will influence bacterial attachment and the formation of biofilms (McEldowney and Fletcher 1987). Therefore, the level of biofilm we observed may be over or underestimated from what might occur in the natural environment. In addition to these considerations, this study focused on growing biofilms under dynamic (versus static) conditions. Dynamic conditions result in less biofilm formation when compared to static conditions (Tomaras et al. 2003). Therefore, our measures of biofilm mass do not represent biofilm that would form in the open environment lacking shearing stress. Of note, the hydrophobicity parameters of each substratum were not determined prior to use in this study, so we cannot definitively correlate differences in biofilm development on the basis of surface hydrophobicity.

Summary

We have demonstrated that there are differences in biofilm formation by A. baumannii ATCC17978 across different substrata. Specifically, we found that the formation of biofilm by A. baumannii ATCC17978 readily developed on polycarbonate followed by stainless steel. Glass was least favorable for biofilm formation. The differences in biofilm formation across different material types may be due to variations in surface roughness and porosity, ionic charge, and hydrophobicity and the extent to which the material surface influences attachment and biofilm formation warrant further investigation. Understanding these differences at the molecular level will deepen our understanding of how microorganisms are able to colonize and persist on medical devices, which is important for the development of new materials that will inhibit microbial attachment and reduce biofilm related infections. In this regard, research on polycarbonate alternatives or on how polycarbonate used in the manufacture of invasive devices could be treated/modified to inhibit microbial attachment and biofilm formation is warranted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and culture conditions:

Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was used for all biofilm tests. A single colony on Mueller Hinton II (MHII) agar plate was sub-cultured into MHII broth (Becton, Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD) and incubated for 15–18h at 37°C, which was then used to create the inoculum for the biofilm development.

Preparation of material coupons:

All material coupons were round discs of one cm in diameter and approximately 3 mm thick. The following non-porous material coupons were used to grow A. baumannii biofilms: medical grade stainless steel (RD128–304), AHW BUNA-N Rubber (RD128-BUNA), porcelain (RD128-PL), polycarbonate plastic (RD128-PC), polypropylene plastic (RD128-PP) and borosilicate glass (RD128-GL) (all material coupons from BioSurface Technologies, MO). Before use, all material coupons were washed with soap and water, followed by a 70% ethanol bath, and then autoclaved for sterilization.

Biofilm development:

A CDC biofilm reactor (Biosurface Technologies, Bozeman, MT) was used for the biofilm growth. The CDC biofilm reactor and its coupon holders were autoclaved before use. Material coupons (3 of each material type) were mounted on the coupon holders and the reactor was supplemented with 10% LB medium by a peristaltic pump with a continuous flow rate of 100 mL per h. Overnight cultures of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 (grown under shaking conditions at 37°C) were diluted by 1:100 for an initial concentration of approximately 4x108 CFU and inoculated into the glass vessel of the CDC reactor aseptically for a final concentration of approximately 1x106 CFU/mL. The liquid growth medium was circulated through the vessel and a magnetic stir bar rotated by a magnetic stir plate generated a shear force. The CDC biofilm reactor was placed on bench and biofilms were grown at room temperature to mimic a natural environment. After four days of growth, the coupons were aseptically removed for biofilm imaging and viable bacteria plate counting. Three duplicate CDC biofilm chamber experiments were performed.

Bacterial count determination:

Biofilms on the coupons were recovered by homogenizing the coupon in 3 mL of 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM, pH7.2) solution for 1 min using Omni-Tip™ disposable probes (OMNI International, Kennesaw, GA). Samples were serially diluted, 50 µl of each dilution were plated onto an MHII agar plate and incubated overnight at 37°C for colony enumeration and the mean colony forming units (CFU) per cm2 was calculated.

Microscope Analysis:

Coupons were used for fluorescent staining and imaging by confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM). Coupon with adhered biofilm was stained with LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability kit (L7012, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorescent images were acquired with an inverted CLSM (Olympus 1X71, Center Valley, PA) equipped with a Fluorescence Illumination System (X-Cite 120, EXFO) and filters for SYTO-9 (excitation = 488 nm/emission = 520 nm) and propidium iodide (excitation = 535 nm/emission = 617 nm). Images were obtained using an oil immersion 60× objective lens and for each location, images were scanned at 1µm intervals. After acquiring images, a 3-D image was re-constructed by using IMARIS 7.3.1 software. Five different surface areas of each material coupon were randomly chosen for imaging in order to better represent biofilms. Biofilm biomass was calculated based on microscopic images using Comstat 2 (Heydorn et al. 2000; Vorregaard 2008). The surface of the rubber absorbed the live/dead stain making it difficult to differentiate the biomass from the background. Therefore, data on the biomass and live/dead ratio obtained for rubber using microscopy was presented for reference only and the viable cell count data (which does not rely on microscopy) is reliable to determine biofilm biomass developed on the rubber.

Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 for Windows (Version 6.01, Graph Pad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons using t-test and a significance level of ≤ 0.05.

SIGNIFICANCE AND IMPACT OF THE STUDY.

In the hospital environment, Acinetobacter baumannii is one of the most persistent and difficult to control opportunistic pathogens. The persistence of A. baumannii is due, in part, to its ability to colonize surfaces and form biofilms. This study demonstrates that A. baumannii can form biofilms on a variety of different surfaces and develops substantial biofilms on polycarbonate- a thermoplastic material that is often used in the construction of medical devices. The findings highlight the need to further study the in vitro compatibility of medical materials that could be colonized by A. baumannii and allow it to persist in hospital settings.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by an internal grant to C.X. at University of Michigan, the NIH grant (R01GM098350) to C.X., the NIH (T32 AI049816) sponsored Training Program in Infectious Disease (IPID), and the University of Michigan Risk Science Center. Special recognition is given to Ting Luo for his assistance with the confocal microscope and rendering the images.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Bos R, Van Der Mei HC and Busscher HJ. (1999) Physico-chemistry of initial microbial adhesive interactions--its mechanisms and methods for study. FEMS Microbiol Rev 23, 179–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandao GA, Pereira AC, Brandao AM, De Almeida HA and Motta RR. (2015) Does the bracket composition material influence initial biofilm formation? Indian J Dental Research 26, 148–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd JF, Agee N, Nguyen PH, Heath JJ, Lau KN, McKillop IH, Sindram D, Martinie JB and Iannitti DA. (2011) Evaluation of composite mesh for ventral hernia repair. JSLS 15, 298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerca N, Pier GB, Vilanova M, Oliveira R and Azeredo J. (2005) Quantitative analysis of adhesion and biofilm formation on hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Research in Microbiol 156, 506–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Lin LC, Chang YJ, Chen YM, Chang CY and Huang CC. (2015) Infection Control Programs and Antibiotic Control Programs to Limit Transmission of Multi-Drug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections: Evolution of Old Problems and New Challenges for Institutes. International journal of environmental research and public health 12, 8871–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Shimoni Z, Ghara R, Ram R and Ben-Ami R. (2014) Effect of a ventilator-focused intervention on the rate of Acinetobacter baumannii infection among ventilated patients. Am J Infect Control 42, 996–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlan RM and Costerton JW. (2002) Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Reviews 15, 167–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duty SM, Mendonca K, Hauser R, Calafat AM, Ye X, Meeker JD, Ackerman R, Cullinane J, Faller J and Ringer S. (2013) Potential sources of bisphenol A in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics 131, 483–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Delgado M, Duque Z, Rojas H, Suarez P, Contreras M, Garcia-Amado MA and Alciaturi C. (2015) Environmental scanning electron microscopy analysis of biofilms grown on chitin and stainless steel. Annals of Microbiol 65, 1401–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Stoodley L and Stoodley P. (2005) Biofilm formation and dispersal and the transmission of human pathogens. Trends in Microbiol 13, 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton G. (1987) Contamination of contrast agent by MBT in rubber seals. Canadian Med Assoc J, 136, 1020–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydorn A, Nielsen AT, Hentzer M, Sternberg C, Givskov M, Ersboll BK and Molin S. (2000) Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 146 ( Pt 10), 2395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Koh YM, Kim J, Lee JC, Lee YC, Seol SY and Cho DT. (2008) Capacity of multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii to form biofilm and adhere to epithelial cell surfaces. Clin Microbiol Infect 14, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchanda V, Sanchaita S and Singh N. (2010) Multidrug resistant acinetobacter. J Global Infect Dis 2, 291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEldowney S and Fletcher M. (1987) Adhesion of bacteria from mixed cell suspension to solid surfaces. Archives of Microbiol 148, 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueary CN and Actis LA. (2011) Acinetobacter baumannii biofilms: variations among strains and correlations with other cell properties. J Microbiol 49, 243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan L, Yang K and Ren G. (2015) Anti-biofilm formation of a novel stainless steel against Staphylococcus aureus. Materials Science and Engineering 51, 356–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patankar NA. (2004) Transition between superhydrophobic states on rough surfaces. Langmuir 20, 7097–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SJ, Oliveira AP, Zhou JJ, Alba L, Furuya EY, Weisenberg SA, Jia H, Clock SA, Kubin CJ, Jenkins SG, Schuetz AN, Behta M, Della-Latta P, Whittier S, Rhee K and Saiman L. (2014) Risk factors and outcomes of infections caused by extremely drug-resistant gram-negative bacilli in patients hospitalized in intensive care units. Am J Infect Control 42, 626–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pour NK, Dusane DH, Dhakephalkar PK, Zamin FR, Zinjarde SS and Chopade BA. (2011) Biofilm formation by Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from urinary tract infection and urinary catheters. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology 62, 328–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren L and Zhang Y. (2014) Sliding contact fracture of dental ceramics: Principles and validation. Acta biomaterialia 10, 3243–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder D, Bornstein L, Bostrom MP, Nestor BJ, Padgett DE and Westrich GH. (2011) Ceramic-on-ceramic total hip arthroplasty: incidence of instability and noise. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 469, 437–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley P, Sauer K, Davies DG and Costerton JW. (2002) Biofilms as complex differentiated communities. Annual Review of Microbiol 56, 187–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland IW. (2001) The biofilm matrix--an immobilized but dynamic microbial environment. Trends in Microbiol 9, 222–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaras AP, Dorsey CW, Edelmann RE and ACTIS LA. (2003) Attachment to and biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces by Acinetobacter baumannii: involvement of a novel chaperone-usher pili assembly system. Microbiology 149, 3473–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towner KJ. (2009) Acinetobacter: an old friend, but a new enemy. The Journal of hospital infection 73, 355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal R, Dominguez M, Urrutia H, Bello H, Gonzalez G, Garcia A and Zemelman R. (1996) Biofilm formation by Acinetobacter baumannii. Microbios 86, 49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorregaard M. (2008) Comstat2 - a modern 3D image analysis environment for biofilms, in Informatics and Mathematical Modelling. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, DTU. [Google Scholar]

- Weber BS, Harding CM and Feldman MF. (2015) Pathogenic Acinetobacter: from the cell surface to infinity and beyond. Journal of bacteriology, 198(6), 880–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt C, Dietze B, Dietz E and Ruden H. (1997) Survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces. J Clin Microbiol 35, 1394–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]