Type 2 cysteine desulfurases are ubiquitous and often essential in plants and microorganisms owing to their role in Fe–S cluster biosynthesis. Here, an X-ray crystal structure of wild-type SufS with a rotated active-site β-hairpin, and a global structure and sequence analysis that argues for a conserved β-latch mechanism regulating type 2 cysteine desulfurases, are reported.

Keywords: sulfur, Fe–S cluster, cysteine desulfurase, SufS

Abstract

Cysteine serves as the sulfur source for the biosynthesis of Fe–S clusters and thio-cofactors, molecules that are required for core metabolic processes in all organisms. Therefore, cysteine desulfurases, which mobilize sulfur for its incorporation into thio-cofactors by cleaving the Cα—S bond of cysteine, are ubiquitous in nature. SufS, a type 2 cysteine desulfurase that is present in plants and microorganisms, mobilizes sulfur from cysteine to the transpersulfurase SufE to initiate Fe–S biosynthesis. Here, a 1.5 Å resolution X-ray crystal structure of the Escherichia coli SufS homodimer is reported which adopts a state in which the two monomers are rotated relative to their resting state, displacing a β-hairpin from its typical position blocking transpersulfurase access to the SufS active site. A global structure and sequence analysis of SufS family members indicates that the active-site β-hairpin is likely to require adjacent structural elements to function as a β-latch regulating access to the SufS active site.

1. Introduction

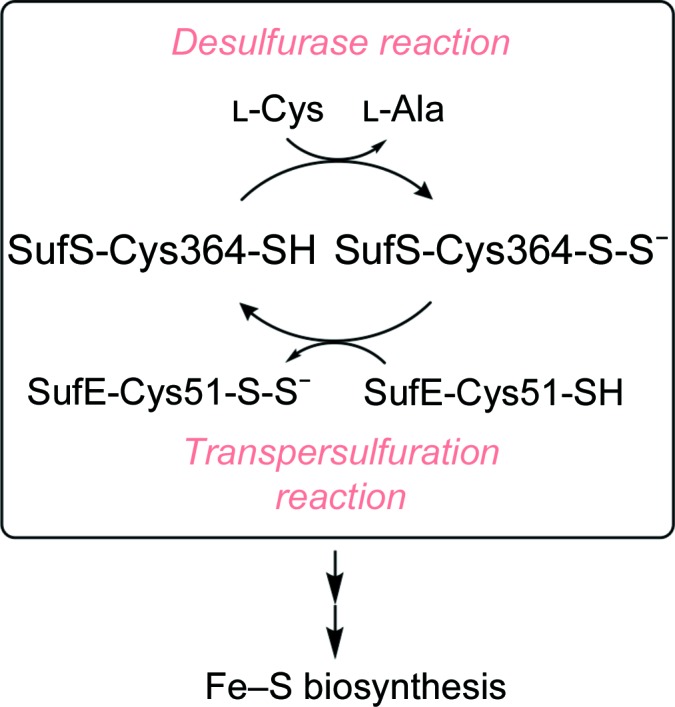

Sulfur is essential to life owing to its presence in cysteine, methionine and numerous thio-cofactors. Sulfate is the predominant form of inorganic sulfur assimilated by plants and microorganisms, which convert it to adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (APS), from which it can either enter sulfation pathways in plants for the synthesis of sulfated metabolites or, in both plants and microorganisms, undergo reduction and incorporation into cysteine (Günal et al., 2019 ▸; Takahashi et al., 2011 ▸; Kredich, 2008 ▸). Cysteine then serves as the sulfur source for thio-cofactors containing reduced sulfur, such as lipoic acid, coenzyme A and Fe–S clusters (Black & Dos Santos, 2015 ▸). Cysteine desulfurases, which cleave the C—S bond in cysteine to yield alanine and persulfide, catalyze the first dedicated step in thio-cofactor synthesis and are ubiquitous in all domains of life (Fig. 1 ▸; Black & Dos Santos, 2015 ▸). Loss of cysteine desulfurase activity causes the human neurodegenerative disease Friedreich’s ataxia (Patra & Barondeau, 2019 ▸).

Figure 1.

Cysteine desulfurases catalyse the cleavage of the Cα—S bond of cysteine. The resulting SufS-Cys364-S-S− intermediate is transferred to Cys51 of SufE and the SufE-bound persulfide is delivered to the SufBCD complex for the formation of Fe–S clusters.

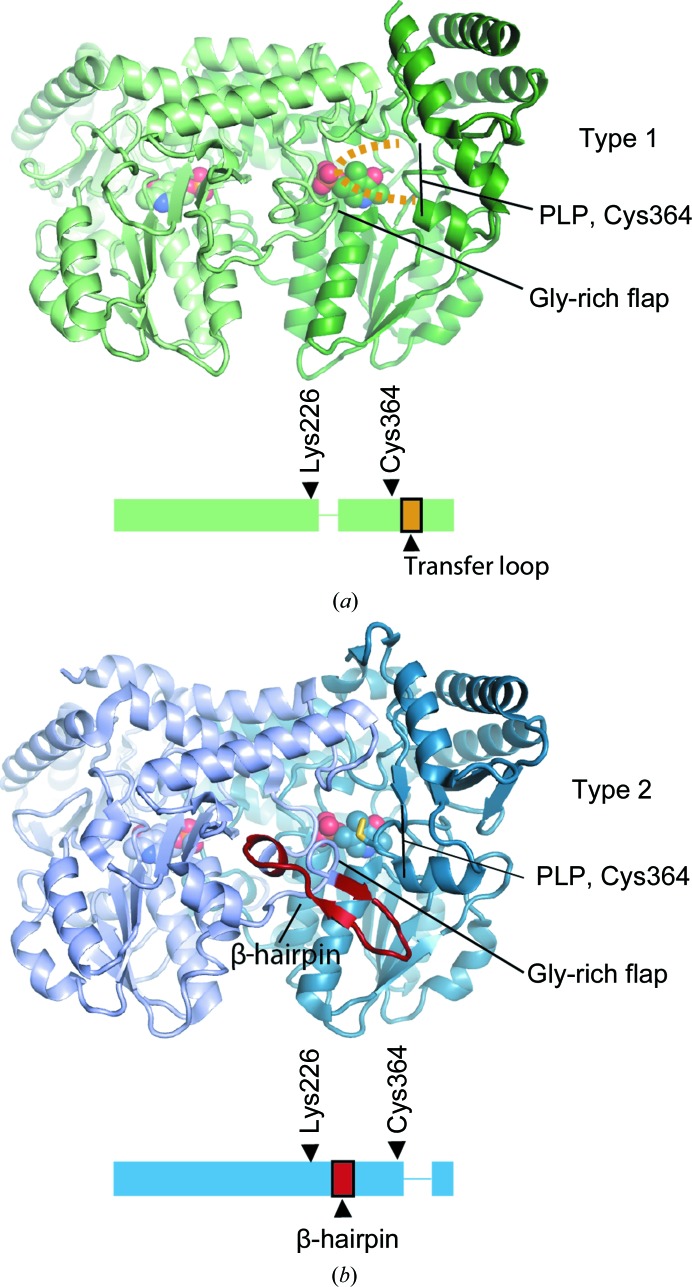

Early structural characterization of cysteine desulfurases revealed that these enzymes are pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent, typically homodimeric and can be grouped into two types (Zheng et al., 1993 ▸; Fujii et al., 2000 ▸; Mihara et al., 1997 ▸; Kaiser et al., 2000 ▸). Type 1 cysteine desulfurases possess an ∼11-amino-acid insertion relative to type 2 enzymes that forms a large mobile loop and includes the active-site cysteine that serves as the persulfide acceptor during the reaction cycle (Fig. 2 ▸ a). The corresponding cysteine residue in type 2 enzymes resides on a short and rigid loop; however, type 2 enzymes contain an insertion C-terminal to Lys226 (Escherichia coli numbering), the residue covalently linked to PLP, that forms a distinctive β-hairpin structure (Fig. 2 ▸ b). The active-site cysteine loop and the β-hairpin make up two of the walls of the active site. Sulfide is labile and toxic and therefore is not released into the cytosol by cysteine desulfurases, but is rather delivered to sulfur transfer proteins (transpersulfurases), which ferry the sulfide to downstream enzymes in thio-cofactor biogenesis (Black & Dos Santos, 2015 ▸). It is hypothesized that the mobile persulfide-containing loop of type 1 enzymes facilitates promiscuous interaction with multiple transpersulfurases, while the rigid loop of type 2 enzymes provides robust protection of the persulfide from oxidation but limits persulfide transfer to only a single transpersulfurase (Kaiser et al., 2000 ▸; Black & Dos Santos, 2015 ▸). Inactivation of the type 1 enzyme IscS leads to phenotypes associated with deficiencies in thionucleosides, thiamine, nicotinic acid and branched-chain amino-acid synthesis as well as Fe–S enzymes (Zheng & Dos Santos, 2018 ▸). This is consistent with its multiple transpersulfurase partners, including TusA, which traffics sulfur for molybdenum-cofactor and 2-thiouridine synthesis, and ThiI, which traffics sulfur for thiamine and 4-thiouridine synthesis (Leimkuhler et al., 2017 ▸; Begley et al., 2012 ▸; Zheng & Dos Santos, 2018 ▸). However, in keeping with the nonpromiscuous nature of type 2 cysteine desulfurases, E. coli SufS cannot complement the non-Fe–S biosynthesis roles of IscS (Bühning et al., 2017 ▸).

Figure 2.

Two structural features that distinguish type 1 and type 2 cysteine desulfurases. (a) The NifS-like protein (PDB entry 1eg5; Kaiser et al., 2000 ▸) possesses the two features that distinguish type 1 from type 2 cysteine desulfurases: the lack of a β-hairpin following the active-site lysine (Lys226 in E. coli numbering) and the presence of a mobile transfer loop containing the active-site cysteine (Cys364 in E. coli numbering). The transfer loop is disordered and is not visible in PDB entry 1eg5, as in most type 1 structures. (b) SufS (PDB entry 6mr2) possesses a β-hairpin adjacent to the active site and the active-site cysteine residue resides on a short and rigid loop.

Recently, extensive structural data for type 2 cysteine desulfurases have become available. Structures describing the interaction of CsdA with its transpersulfurase CsdE have been reported, along with structures reporting the interaction of SufS with its transpersulfurase SufU (Kim & Park, 2013 ▸; Fernández et al., 2016 ▸; Fujishiro et al., 2017 ▸). Additionally, the dynamic changes of SufS during its catalytic cycle, as well as the structures of reaction intermediates, have been reported (Blauenburg et al., 2016 ▸; Kim et al., 2018 ▸; Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸; Blahut et al., 2019 ▸; Nakamura et al., 2019 ▸). Kim and coworkers found that the formation of a persulfide in the active site of SufS (Cys364-S-S−) leads to dynamic changes in the protein as reported by hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), not only in the active site but also among the electrostatic interactions at the homodimer interface (Kim et al., 2018 ▸). Functional cross-talk between the dimer interface and the active site(s) was confirmed through mutagenesis of the dimer-interface residues followed by kinetics measurements and X-ray structures of the site-directed mutants (Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸). X-ray structures of dimer-interface mutants with kinetic defects in transpersulfuration revealed a global ∼3.5° rotation of the SufS monomers and rotation of the β-hairpin away from Cys364-S-S−, yielding a more open conformation of the active site (Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸). Structural superpositions of SufS with the CsdA–CsdE co-crystal structure revealed that while CsdE is sterically blocked from approaching close enough to the active-site cysteine for sulfur transfer, the open β-hairpin conformation observed in the SufS site-directed mutants would allow a closer approach of the transpersulfurase. It has not yet been demonstrated, however, that wild-type SufS can adopt the open β-hairpin conformation observed in the site-directed mutants.

We recently discovered new crystallization conditions for E. coli SufS that yielded a P21 crystal form diffracting to 1.5 Å resolution with a homodimer in the asymmetric unit. Each monomer is bound to PLP and contains Cys364-S-S− within the active site. Comparison of the structure with previous structures of E. coli SufS reveal that the β-hairpin is rotated into an open position and that electrostatic interactions at the homodimer interface have been lost, interactions that were previously hypothesized to regulate β-hairpin dynamics (Kim et al., 2018 ▸; Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸). The structure demonstrates that the open β-hairpin conformation can be populated by the wild-type enzyme and not solely by the site-directed mutants (Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸). We performed a survey of all cysteine desulfurases in the wwPDB and found that sequence-homology clustering of cysteine desulfurases into the IscS and SufS/CsdA InterPro families faithfully reflects the type 1 versus type 2 structural relationship. Lastly, sequence-conservation analysis and structural superpositions of all type 2 cysteine desulfurases in the wwPDB suggest that the dynamics of the active-site β-hairpin are regulated by adjacent conserved structural elements. The β-hairpin, in conjunction with these elements, forms a β-latch regulating access to the active site of type 2 cysteine desulfurases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production and crystallization

E. coli SufS was expressed and purified as described previously (Dai & Outten, 2012 ▸). Briefly, E. coli BL21 (DE3) ΔsufS cells were transformed with pET-21-sufS. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 500 µM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to liquid cultures in LB/ampicillin medium at an OD600 of ∼0.6 and cell growth was continued at 37°C for 3 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT and lysed by sonication. The clarified lysate was applied onto a Q Sepharose column and a 1 M linear gradient of NaCl was used to elute SufS. SufS-containing peaks were readily identified by the absorbance at 420 nm associated with the covalently bound PLP cofactor. The SufS-containing eluate was subjected to chromatography on a Phenyl FF column and a Superdex 200 column as reported previously (Dai & Outten, 2012 ▸). Purified protein was aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until needed.

The P21 crystals of SufS were first identified in a 96-well sitting-drop vapor-diffusion tray at 20°C in condition G10 of the Index screen from Hampton Research. Further optimization of the crystals was conducted as sitting-drop vapor-diffusion experiments under film in Cryschem plates (Hampton Research) using 2 µl 10 mg ml−1 SufS and 1 µl crystallization solution [0.2 M MgCl2, 0.1 M bis-Tris–HCl pH 5.5, 20–30%(w/v) PEG 3350] at 20°C. The crystal used for data collection was grown in crystallization solution containing 23.3%(w/v) PEG 3350 and appeared as a yellow plate, indicating the presence of the PLP cofactor.

2.2. Data collection and processing

Crystals were prepared for cryo data collection by performing two exchanges of the crystals into mother liquor mixed with 100% glycerol in a 1:1 ratio followed by flash-cooling in liquid N2. Native diffraction data were collected on the 22-ID SER-CAT beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at 100 K using X-rays of wavelength 1.000 Å, 9.1% transmission, 0.2 s exposures and a Dectris EIGER 16M detector. A 175° rotation of the crystal was measured using 0.25° per frame. Native data were processed with XDS to 1.50 Å resolution, yielding the statistics in Table 1 ▸. Anomalous diffraction data using X-rays of wavelength 1.740 Å were collected to identify sulfur in the form of persulfide in the enzyme active site. Anomalous data were collected at 100 K guided by published methods for acquiring the highly redundant data necessary for the ‘native SAD’ procedure (Liu et al., 2012 ▸; Olieric et al., 2016 ▸). Two and a half full rotations of the crystal were collected using 3% transmission, 0.2 s exposure and 0.25° per frame. The data were processed in XDS to 3.30 Å resolution, yielding the statistics in Table 1 ▸.

Table 1. X-ray crystallographic data-collection and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Native | Anomalous | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Beamline | SER-CAT 22-ID, APS | SER-CAT 22-ID, APS |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 | 1.740 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 |

| Resolution (Å) | 32.2–1.5 (1.54–1.50) | 57.9–3.3 (3.39–3.31) |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 200 | 150 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 175 | 900 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Space group | P43212 | P43212 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 60.5, b = 115.7, c = 63.5, α = γ = 90, β = 114.4 | a = 60.5, b = 115.7, c = 63.6, α = γ = 90, β = 114.5 |

| Observed reflections | 415026 | 241953 |

| Unique reflections | 125851 | 22738 |

| R meas (%) | 6.7 (145.1) | 6.2 (10.6) |

| R merge (%) | 6.4 (127.3) | 5.9 (10.1) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 10.9 (0.9) | 34.4 (18.9) |

| CC1/2 | 0.998 (0.303) | 0.999 (0.995) |

| Multiplicity | 3.3 (3.3) | 10.6 (9.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.0 (99.2) | 96.5 (94.0) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 32.2–1.50 | |

| No. of reflections | 125842 | |

| R work/R free (%) | 19.7/22.0 | |

| No. of non-H atoms | ||

| Protein | 6207 | |

| Water | 311 | |

| PLP | 30 | |

| B factors (Å2) | ||

| Protein | 27.8 | |

| Water | 30.5 | |

| PLP | 25.3 | |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.004 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.670 | |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Favored | 97.97 | |

| Allowed | 2.03 | |

| Outliers | 0.00 | |

| MolProbity score | 1.54 | |

| PDB code | 6uy5 | |

Diffraction data were integrated and reduced using XDS and XSCALE. XDS identified the space group as P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 60.5, b = 115.7, c = 63.6 Å, α = γ = 90.0, β = 114.4°, for the native data set. An isomorphous cell with unit-cell parameters a = 60.5, b = 115.6, c = 63.5 Å, α = γ = 90.0, β = 114.5° was identified for the 1.740 Å resolution anomalous data.

2.3. Structure solution and refinement

The Matthews coefficient suggested two copies of the SufS monomer per asymmetric unit and 44.8% solvent content. The SufS homodimer has C2 symmetry, often crystallizing with the dimer axis along a crystallographic symmetry axis. The E. coli SufS structure from PDB entry 1jf9 (Lima, 2002 ▸) with all heteroatoms removed was used as the search model for phasing by automated molecular replacement in Phaser version 2.8 (Lima, 2002 ▸; McCoy et al., 2007 ▸). A single solution was obtained by Phaser, indicating that two SufS monomers were present per asymmetric unit with only approximate C2 symmetry between the monomers. Rigid-body, individual sites and individual atomic displacement parameter refinement in Phenix (Liebschner et al., 2019 ▸) were used to generate 2F o − F c and F o − F c electron-density maps for modeling. In the final round of refinement, anisotropic atomic displacement parameter refinement was performed using translation–libration–screw (TLS) parameterization in Phenix.

F o − F c electron-density maps following the initial round of refinement, before the placement of heteroatoms, contained strong peaks in the active site consistent with the presence of PLP and a persulfide moiety on the active-site cysteine residue, Cys364-S-S− (Fig. 3 ▸ b). As-isolated cysteine desulfurases often contain a persulfide in the active site (Roret et al., 2014 ▸; Blauenburg et al., 2016 ▸; Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸). To confirm the origin of the F o − F c peak at Cys364 as Cys364-S-S−, a map was constructed by the phenix.maps tool using the S anomalous signal in the 1.740 Å wavelength data set and the model-derived phases obtained by molecular replacement. The resulting 3.3 Å resolution anomalous map contained a 3σ peak at Cys364 centered 2.1 Å from the Cys364 Sγ atom, confirming the covalent adduct as Cys364-S-S− (Fig. 3 ▸ c). A peak for the phosphate of PLP, and peaks throughout the asymmetric unit at the locations of cysteine and methionine residues, confirmed the quality of the anomalous signal in the maps.

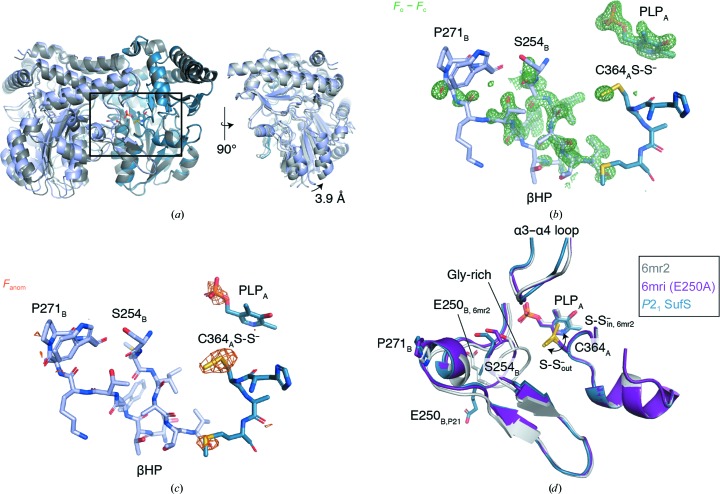

Figure 3.

A new, P21 crystal form of E. coli SufS adopts a rotated form of the homodimer displacing the active-site β-hairpin. (a) A superposition of the P21 E. coli SufS with nonrotated E. coli SufS in PDB entry 6mr2. (b) An unbiased F o − F c electron-density map (green) covering the β-hairpin (βHP) and active site is shown at 3.0σ. The map was generated prior to modeling heteroatoms and the β-hairpin change but is shown overlaid with the final refined coordinates. (c) A native SAD map (orange) is shown at 2.8σ overlaid with the final refined coordinates. (d) The boxed region in (a) is shown in detail, revealing that the rotation of the β-hairpin displaces Ser254 and the glycine-rich loop which reside adjacent to the active-site Cys364 persulfide moiety. The P21 SufS structure possesses a persulfide moiety on Cys364; it is in the ‘out’ position rotated away from the PLP cofactor.

After the first round of refinement, extensive F o − F c peaks surrounding the β-hairpin component of the SufS active site remained, indicating a large conformational change in this region (Fig. 3 ▸ b). Iterative cycles of manual remodeling and refinement were performed for the β-hairpins of monomer A and monomer B, and comparison of a composite OMIT map with the final model showed good agreement. The conformations of the β-hairpin in monomers A and B are similar but not identical. The β-hairpin of monomer B was used for further analysis. A distinctive feature of cysteine desulfurases is a glycine-rich region composing one wall of the active site (Figs. 2 ▸ and 3 ▸ d). The three consecutive glycine residues at 251–253 had clear electron density in previous E. coli SufS crystal structures, but in the current structure in which the β-hairpin is rotated away from the active site there is insufficient electron density in either SufS monomer to guide the modeling of residues 251–253 and so they are omitted (Fig. 3 ▸ d).

2.4. Global analysis of cysteine desulfurase structures and sequence conservation

To generate Table 2 ▸, which classifies all cysteine desulfurases in the PDB by the presence or absence of the active-site β-hairpin, a hallmark of type 2 enzymes, we used the advanced search tool at the RCSB PDB (http://www.rcsb.org/) with Enzyme Commission number 2.8.1.7 as the query. A customizable table was then retrieved from the RCSB PDB with the UniProt Accession ID and the Enzyme Commission number. The InterPro assignments in Table 2 ▸ were made either by consulting the table of InterPro–wwPDB correspondences provided by SIFTS (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/docs/sifts/) or by inspection of the UniProt records (Dana et al., 2019 ▸). 55 wwPDB entries were retrieved by the search, composed of 106 entities. The wwPDB entries were retrieved using the batch download tool at http://www.rcsb.org/. A representative for each unique cysteine desulfurase sequence was inspected in PyMOL to test for the presence of the active-site β-hairpin.

Table 2. Cysteine desulfurases in the PDB.

| UniProt ID | Type 1 or 2 | Example PDB entry | IscS or SufS InterPro | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O25008 | 1 | 5wt2 | IPR010240 IscS | Helicobacter pylori |

| P0A6B7 | 1 | 1p3w | IPR010240 IscS | Escherichia coli K12 |

| P0A6B9 | 1 | 3lvj | IPR010240 IscS | Escherichia coli O157:H7 |

| P9WQ71 | 1 | 4isy | ? | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| Q9Y697 | 1 | 5usr | IPR010240 IscS | Homo sapiens |

| O29689 | 1 | 4eb5 | IPR010240 IscS | Archaeoglobus fulgidus |

| A0A077EMQ8 | ? | 5vpr | IPR010970 SufS | Elizabethkingia anophelis |

| B6YT87 | 2 | 5b7s | ? | Thermococcus onnurineus |

| O32164 | 2 | 5j8q | IPR010970 SufS | Bacillus subtilis |

| P77444 | 2 | 6mr2 | IPR010970 SufS | Escherichia coli K12 (SufS) |

| Q46925 | 2 | 4lw2 | ? | Escherichia coli K12 (CsdA) |

| Q55793 | 2 | 1t3i | IPR010970 SufS | Synechocystis |

| Q93WX6 | 2 | 4q75 | IPR010970 SufS | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Q5ZXX6 | 2 | 6c9e | IPR010970 SufS | Legionella pneumophila |

Once the type 2 cysteine desulfurases in the wwPDB had been identified, a superposition of all type 2 chains was produced using THESEUS (Theobald & Steindel, 2012 ▸). Coordinate files were split into chains, and chains not annotated as EC 2.8.1.7 were discarded. The amino-acid sequences of the type 2 cysteine desulfurases were extracted using THESEUS and multiple sequence alignment was performed with Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011 ▸). The resulting multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was used as input to THESEUS to perform a maximum-likelihood superposition of the cysteine desulfurases guided by the MSA. Inspection of the superposition in PyMOL revealed that 16 representatives were sufficient to capture all of the structural variation present in the data set (Table 3 ▸). The 16 chains correspond to at least one chain for each unique amino-acid sequence and PDB entry 6uy5 chain A. The plot of r.m.s.d. versus residue was generated from the data reported in theseus_variances.txt.

Table 3. The 16 representatives that capture the structural variation present in the type 2 enzymes.

| UniProt ID | PDB code, chain | Organism | Protein | Functional state |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P77444 | 6uy5, A | E. coli | SufS | Cys364-S-S− out-2 |

| P77444 | 6mr2, A | E. coli | SufS | Cys364-S-S− in |

| P77444 | 6mri, A | E. coli | SufS | Cys364-S-S− out |

| P77444 | 6o11, A | E. coli | SufS | Cys–aldimine intermediate |

| Q46925 | 4lw4, A | E. coli | CsdA | CsdE-bound |

| Q46925 | 4lw2, A | E. coli | CsdA | Resting state |

| Q46925 | 5ft8, A | E. coli | CsdA | CsdE-bound |

| Q46925 | 5ft8, K | E. coli | CsdA | CsdE-bound |

| O32164 | 5j8q, A | B. subtilis | SufS | Resting state |

| O32164 | 5xt5, A | B. subtilis | SufS | SufU-bound |

| O32164 | 5zs9, A | B. subtilis | SufS | Resting state |

| O32164 | 5zsk, A | B. subtilis | SufS | Ala–aldimine intermediate |

| Q93WX6 | 4q75, A | A. thaliana | NSF2 | Cys364-S-S− out |

| B6YT87 | 5b7s, A | T. onnurineus | TON_0289 | Resting state |

| Q55793 | 1t3i, A | Synechocystis | Csd | Resting state |

| Q5ZXX6 | 6c9e, A | L. pneumophila | Lpg0604 | Resting state |

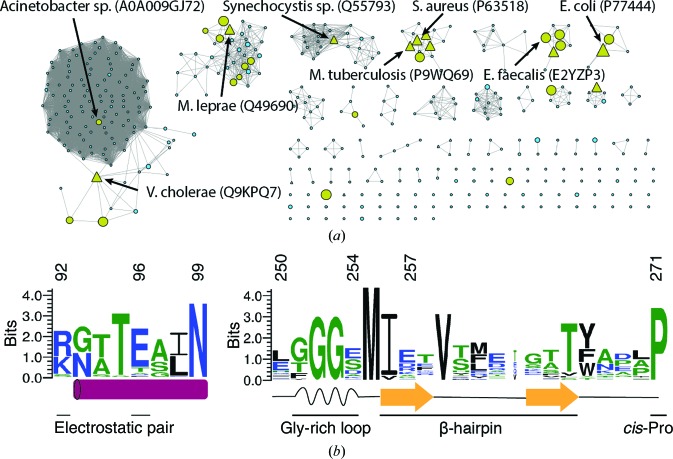

Sequence-conservation analysis was performed as described in Dunkle et al. (2019 ▸). Briefly, the EFI Enzyme Similarity Tool (https://efi.igb.illinois.edu/efi-est/) was used to generate a sequence-similarity network (SSN) for IPR010970, which contains 18 567 sequences (Atkinson et al., 2009 ▸). Sequences were binned into representative nodes when they possessed an alignment score of 45 or higher, and the EFI Enzyme Similarity Tool was used to create an xgmml file for Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003 ▸). In Cytoscape, a representative sequence from each of 29 nodes containing >100 sequences was chosen for input to MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004 ▸). The MSA generated by MUSCLE was rendered as the sequence logo shown in Fig. 7 using WebLogo 3 (Crooks et al., 2004 ▸).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Crystal structure of wild-type E. coli SufS with a rotated active-site β-hairpin

Superposition of the P21 form of E. coli SufS with the SufS homodimer given by PDB entry 6mr2 (Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸) revealed a reorientation of the monomers relative to each other that can be described as a pivot roughly around the C2 axis with a maximum displacement of 3.9 Å (Fig. 3 ▸ a). Superposition of the P21 structure with the coordinates given by PDB entry 6mri, an E250A site-directed mutant of SufS with an altered dimer interface (Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸), or PDB entry 6mrh, a related dimer-interface mutant (Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸), revealed the P21 homodimer to be similar to these structures.

Inspecting the active site in superpositions of the P21 form of SufS with previous SufS structures, PDB entries 6mr2 and 6mri, indicates that a new β-hairpin position has been adopted in the P21 structure. PDB entry 6mr2 is a Cys364-S-S− in structure: the Cys364-S-S− moiety points towards PLP, a state that occurs just after C—S bond cleavage in cysteine (Fig. 1 ▸). PDB entry 6rmi is an E250A mutant, which causes the loss of an electrostatic interaction between the β-hairpin and the dimer interface and a subsequent rotation of the β-hairpin away from Cys364-S-S−, opening up the active site of SufS. In PDB entry 6mri the active-site persulfide moiety is rotated away from PLP and points towards the solvent interface, as required for persulfide transfer to SufE (Fig. 1 ▸). For this reason, PDB entry 6mri can be labeled Cys364-S-S− out. Superpositions of the three coordinate sets indicate that the P21 form has adopted the β-hairpin-rotated, Cys364-S-S− out position, yet the Ser254B loop (we use A and B to differentiate the monomers of the SufS homodimer) is displaced further from the Cys364 persulfide than in PDB entry 6mri. Therefore, we label the conformation of SufS captured in the P21 crystal form Cys364-S-S− out-2.

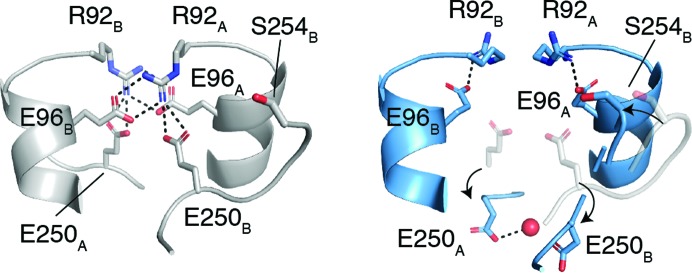

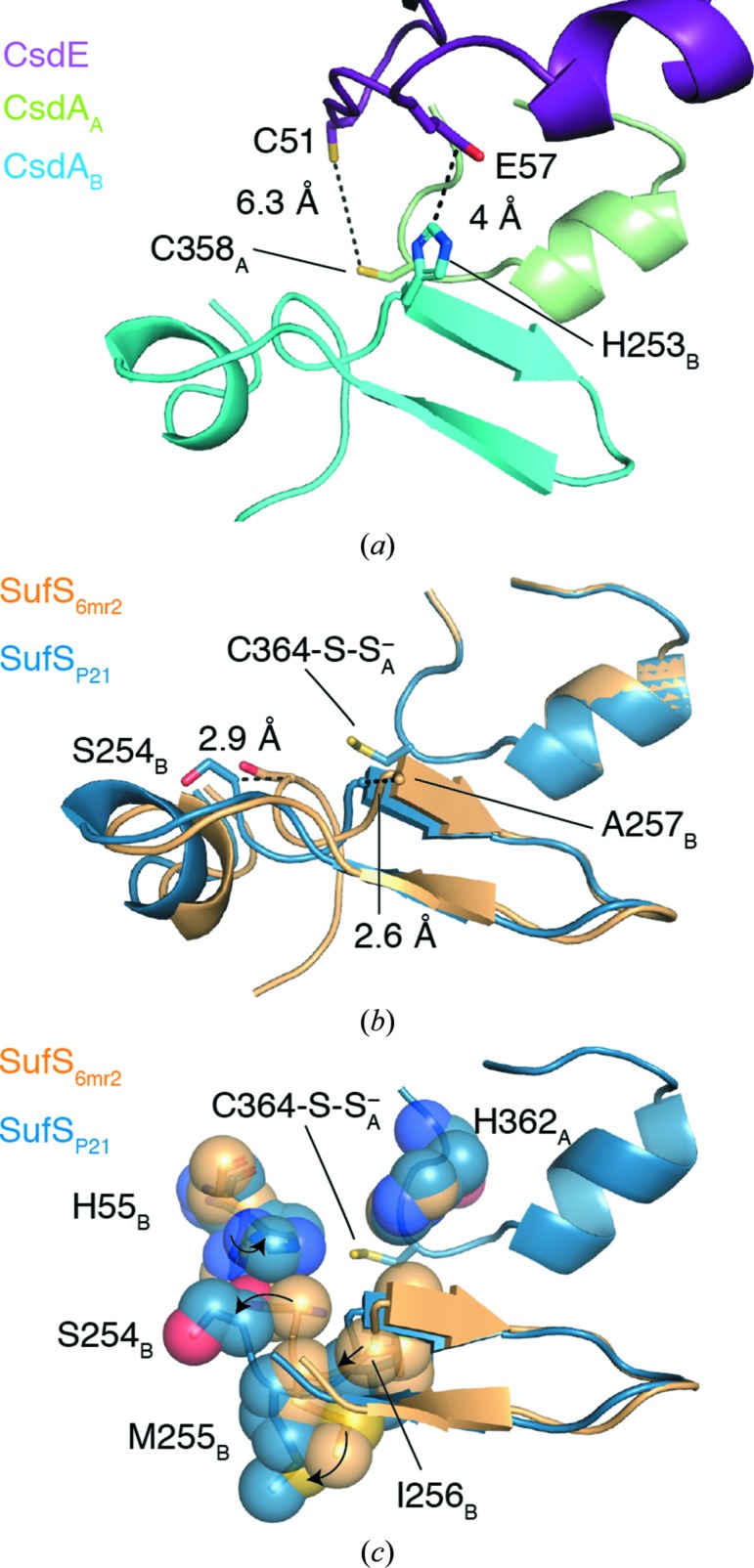

Previous studies of SufS structure and dynamics suggest the functional significance of the Cys364-S-S− out-2 conformation. It has been shown that the SufS cross-dimer electrostatic interactions mediated by Arg92, Glu96 and Glu250 control the position of the β-hairpin and that the dynamics of the active site and the dimer interface are linked through the β-hairpin and the adjacent loop containing the glycine-rich region, Glu250 and Ser254 (Figs. 3 ▸ d and 4 ▸; Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸; Kim et al., 2018 ▸). Site-directed mutants of Glu96 and Glu250 have kinetic defects in persulfide transfer to SufE, implicating the β-hairpin dynamics in efficient persulfide transfer (Fig. 1 ▸; Kim et al., 2018 ▸). Since no crystal structure exists of the SufS–SufE complex, the structural basis of the kinetic defect was investigated by superposition of SufS using the structure of the homologous type 2 cysteine desulfurase CsdA bound to CsdE, its sulfur-trafficking partner (Kim & Park, 2013 ▸). This analysis revealed that the β-hairpin of CsdA sterically blocks the close approach of Cys51 of CsdE to the CsdA active-site cysteine to within 2–3 Å, as is necessary for sulfur transfer (Fig. 5 ▸ a). The rotated β-hairpin present in Cys364-S-S− out is then a transient opening of the steric block to allow sulfur transfer (Figs. 5 ▸ b and 5 ▸ c). However, since the site-directed mutants SufS E96A or E260A were used to capture Cys364-S-S− out it was only presumed that wild-type SufS could adopt the rotated β-hairpin conformation. The Cys364-S-S− out-2 conformation reported here shows that wild-type SufS can indeed adopt a conformation in which the electrostatic interactions at the dimer interface are restructured to allow β-hairpin rotation (Figs. 3 ▸ d and 4 ▸).

Figure 4.

Disruption of electrostatic interactions at the SufS homodimer interface facilitates the movement of Ser254 and the glycine-rich loop. Arg92 and Glu96 form intermolecular electrostatic interactions (left) in the coordinates given by PDB entry 6mr2. In the P21 SufS crystal form (right), Arg92 and Glu96 form intramolecular electrostatic interactions and Glu250 rotates away from the dimer interface towards the solvent. In the right image the P21 SufS coordinates are shown in blue and the superpositioned PDB entry 6mr2 coordinates are shown in gray.

Figure 5.

Movement of the β-hairpin facilitates access of the sulfur transfer protein to the SufS active-site persulfide. (a) Analysis of the existing structures of type 2 cysteine desulfurases bound to a sulfur transfer protein, such as the structure of CsdA–CsdE given by PDB entry 4lw4 (Kim & Park, 2013 ▸), reveals that the commonly observed position of the β-hairpin impedes active-site access. (b) A superposition of the P21 SufS structure with the SufS coordinates given by PDB entry 6mr2 reveals a 2.6 Å shift of the β-hairpin at the residue corresponding to His253 in CsdA, which sterically blocks active-site access by CsdE. A 2.9 Å shift is observed at Ser254 in the glycine-rich region. (c) An additional superposition of P21 SufS and PDB entry 6mr2 with the residues surrounding Cys364-S-S− shown as spheres.

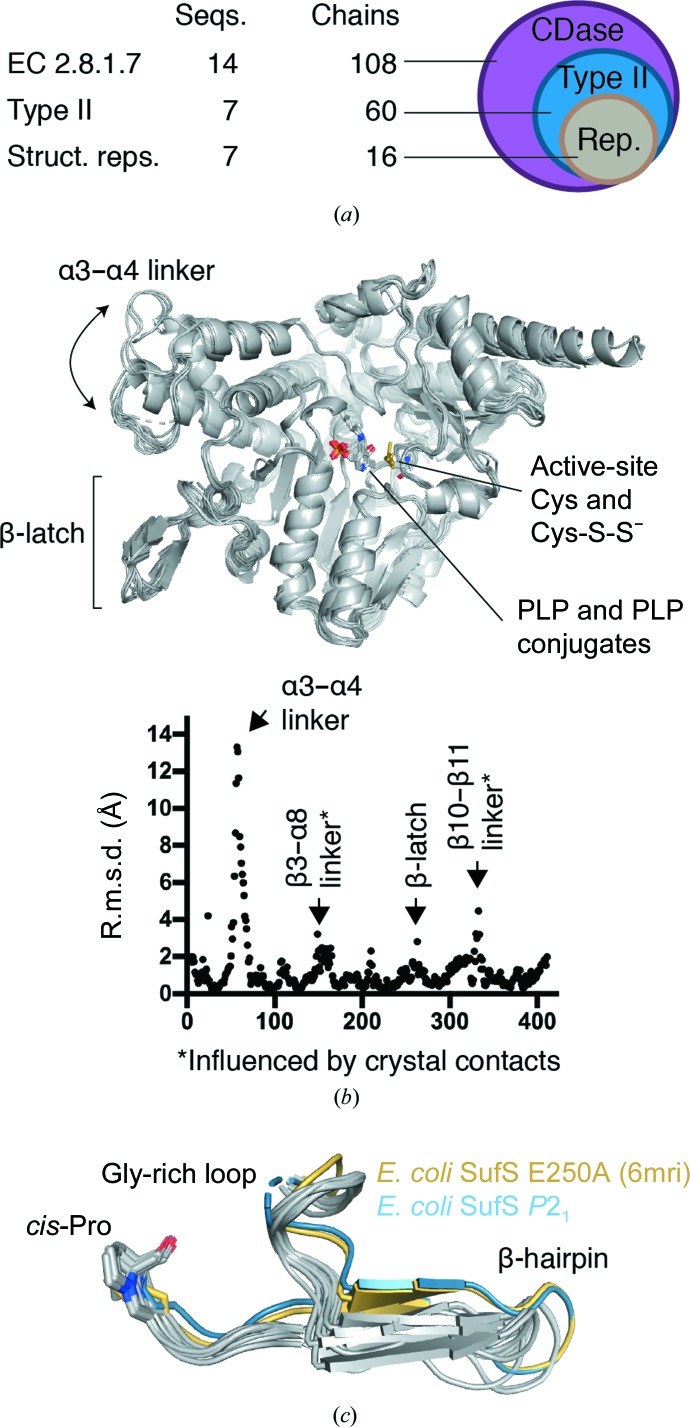

3.2. A global structural analysis of type 2 cysteine desulfurases

Categorizing cysteine desulfurases into types 1 and 2, in part depending on the presence of the active-site β-hairpin, has been a useful tool since the two types were originally proposed (Mihara et al., 1997 ▸). However, the two types were proposed based on a limited number of sequences and structures. Therefore, we revisited the utility of the β-hairpin as a classifier using the structures of cysteine desulfurases in the wwPDB from 14 different organisms (all structures labeled as EC 2.8.1.7, cysteine desulfurase activity; Table 2 ▸). Of the 14 distinct cysteine desulfurase sequence structures, five belong to the InterPro IPR010240 IscS family by sequence homology and inspection of the corresponding structures reveals that none possess a β-hairpin adjacent to the active site. Six sequences/structures belong to the IPR010970 SufS family by sequence homology, and inspection of these structures reveals that five possess the β-hairpin structure and one, PDB entry 5vpr from Elizabethkingia anophelis (Seattle Structural Genomics Center, unpublished work), possesses the sequence insertion that typically forms the β-hairpin; however, in the crystal structure (PDB entry 5vpr) this region is disordered and was not modeled. Three additional sequences/structures do not map to the InterPro families containing most IscS or SufS homologs. However, inspection of the structures reveals that Mycobacterium tuberculosis IscS (PDB entry 4isy; Rybniker et al., 2014 ▸) does not contain a β-hairpin and can be classified as type 1, while Thermococcus onnurineus SufS contains a β-hairpin adjacent to the active site and can be classified as a type 2 enzyme. The remaining sequence/structure is E. coli CsdA, which is structurally a type 2 cysteine desulfurase but clusters with IPR022471, a distinct InterPro family for CsdA homologs. Therefore, we conclude that there is good correspondence between the IscS InterPro protein family (IPR010240) representing type 1 structures and the SufS InterPro protein family (IPR010970) representing type 2 structures. The hypothesis for distinct type 1 (IscS-like or NifS-like) and type 2 SufS-like cysteine desulfurases holds up against the extensive sequence and structure data that are now available. One interesting exception is the cysteine desulfurase (PDB entry 5vpr) from E. anophelis, a Bacteroidetes bacterium, which may have diverged from other type 2 enzymes.

The seven unique sequences in the wwPDB that we confirmed as type 2 cysteine desulfurases comprise 60 chains in the wwPDB owing to the presence of multiple copies of the protein in the asymmetric units of some crystals and the existence of structures of multiple functional states, for example bound to a sulfur transfer partner or unbound (Fig. 6 ▸ a). To probe this data set for additional conserved or divergent structural features and to inspect the conformation of the β-hairpin across the data set, we performed a superposition of all 60 chains using the maximum-likelihood-based THESEUS algorithm (Theobald & Steindel, 2012 ▸). Inspection of the resulting superposition revealed that the structural diversity of type 2 cysteine desulfurases in the wwPDB could be captured by the 16 chains given in Table 3 ▸. The core of the enzyme, including the site of the covalent attachment of PLP to a resident lysine, was extremely similar across all 16 chains (Fig. 6 ▸ b). A plot of r.m.s.d. versus position possessed four peaks above 2 Å r.m.s.d., comprising a large alteration in the position of α3 and α4 in CsdA versus other type 2 enzymes, a peak for the β3-α8 linker, a peak at the active-site β-hairpin and a peak at the β10–β11 linker (Fig. 6 ▸ b). The α3 and α4 structural difference is striking owing to the high sequence similarity to other type 2 enzymes, even in this region, and is likely to have important functional implications for CsdA chemistry, as the linker between α3 and α4 provides the crucial Arg56 to the active site to promote deprotonation of the Cα of cysteine (Blahut et al., 2019 ▸). The structural diversity in the β3–α8 linker and the β10–β11 linker cannot readily be assigned a functional role based on the literature, and since these solvent-facing regions of the protein are often involved in crystal contacts the high r.m.s.d. in these two regions may not be functionally relevant.

Figure 6.

A PDB-wide assessment of conformational diversity in type 2 cysteine desulfurases. (a) A search of the wwPDB by Enzyme Commission number for cysteine desulfurase activity indicates that structural data are available for 14 unique protein sequences comprising 108 protein chains. Seven sequences comprising 60 chains possess the structural features of type 2 cysteine desulfurases and 16 of these chains were sufficient to capture the conformational diversity in the wwPDB. (b) A maximum-likelihood superposition of the 16 chains performed using THESEUS. A plot of root-mean-squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) versus position number for 16 representative structures reveals four regions of structural diversity in existing structures of type 2 cysteine desulfurases, of which two, the α3–α4 linker and the β-latch, have functional significance. (c) Comparison of the β-latch region from 16 representative structures reveals structural conservation of three features that we hypothesize to be functionally important for latch-mechanism gating of the active site: the glycine-rich loop, the β-hairpin secondary-structure element and a cis-proline.

3.3. A conserved β-latch in type 2 cysteine desulfurases

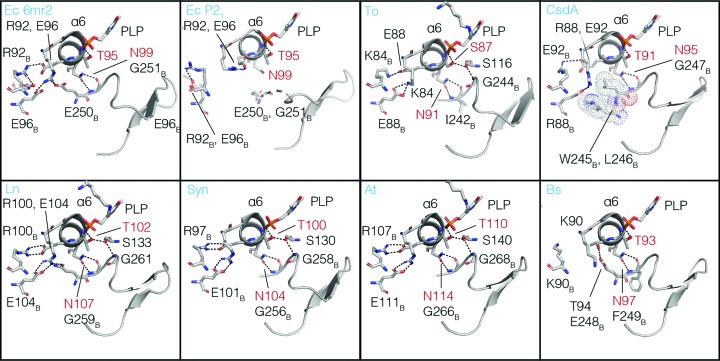

Inspection of the β-hairpin in the superpositioned structures reveals that the Cys364-S-S− out-2 conformation that we observed in the P21 form of E. coli SufS is most like the E. coli E250A SufS mutant structure, but is rotated further from Cys364-S-S− in the active site and a hydrogen-bonding interaction between Asn99 and the glycine-rich loop is lost (Figs. 6 ▸ c and 7 ▸). Together, these two structures have a distinct β-hairpin confirmation from the other type 2 structures (Fig. 6 ▸ c). This observation reinforces the correlation between rotation of the β-hairpin away from the active site and disruption of the electrostatic interactions at the dimer interface (Arg92, Glu96 and Glu250 in E. coli; Figs. 4 ▸ and 7 ▸). Additionally, the superposition reveals that there are structural features adjacent to the β-hairpin in all type 2 enzymes that are likely to act with it as a single functional unit. These are the glycine-rich loop preceding the β-hairpin, a cis-proline residue following the β-hairpin, a cross-dimer electrostatic pair formed by residues of α6 and an asparagine residue on α6 that hydrogen-bonds to the backbone of the glycine-rich loop (Figs. 6 ▸ c and 7 ▸). We hypothesize that these four structural features and the β-hairpin itself work together, in what can be termed a β-latch, to regulate the access of sulfur transfer proteins to the active site of type 2 cysteine desulfurases. We propose that the cross-dimer versus intra-dimer electrostatic interaction of Arg92 and Glu96 (E. coli numbering) controls the position of α6. In turn, Asn99 of α6 hydrogen-bonds to the glycine-rich loop holding the β-latch closed in the inter-dimer conformation of the enzyme, but allows the β-latch to transiently rotate open in the intra-dimer conformation observed in Cys364-S-S− out-2 (Fig. 7 ▸). The β-hairpin acts as a rigid unit, sterically blocking access to the type 2 active-site unit until it rotates away from it. The cis-proline residue downstream of the β-hairpin acts as a pivot point controlling the magnitude of the β-hairpin displacement (Figs. 6 ▸ c and 7 ▸).

Figure 7.

Conserved interactions mediated by α-helix 6 (α6) coordinate conformational changes of the β-latch. Comparison of the α6 region of the 16 representative type 2 cysteine desulfurase structures (eight are shown) revealed that a threonine/serine residue (red) and an asparagine (red) of α6 form structurally conserved interactions mediating cross-talk between the homodimer interface, the PLP cofactor and the β-latch. Species abbreviations are Ec, E. coli; To, T. onnurineus; Ln, Legionella pneumophila; Syn, Synechocystis; At, A. thaliana; Bs, B. subtilis.

The observation of the β-latch structural elements in the structures of type 2 cysteine desulfurases from seven different organisms argues that these elements are broadly conserved in this protein family. However, to further test conservation we constructed a sequence-similarity network using 18 567 sequences from the SufS InterPro family, IPR010970, the largest sequence cluster of type 2 cysteine desulfurases (Fig. 8 ▸ a; Atkinson et al., 2009 ▸). The sequences were grouped as described in Section 2, resulting in 29 representatives that were used for the construction of a multiple sequence alignment. This alignment was rendered as a sequence logo and is presented in Fig. 8 ▸(b). The sequence logo shows conservation of Arg92 or Lys92 and of Glu96 (E. coli numbering here and below) comprising the electrostatic dimer-interface pair. Asn99 and the two glycine residues of the glycine-rich region are strongly conserved, and together link the dynamics of α6 and the β-hairpin. Sequence conservation in the β-hairpin itself is low, but this is expected given the many sequences that are compatible with an architecture of two antiparallel β-strands. Pro271, which adopts a cis-peptide backbone conformation in each of the type 2 cysteine desulfurase structures in the wwPDB, is strongly conserved at the sequence level.

Figure 8.

The key sequence elements of the β-latch are conserved across the SufS family.

We previously showed, by steady-state kinetics, a functional defect in transpersulfurase activity for an E250A mutant of E. coli SufS and that Glu250 in E. coli SufS acts as a structural link between the dimer interface and the β-hairpin, coupling their dynamics (Dunkle et al., 2019 ▸). However, Glu250 is not conserved across the SufS family, suggesting instead that the universally conserved Asn99 may be the most important interaction for coupling dimer-interface dynamics to the β-hairpin in the type 2 cysteine desulfurases (Figs. 7 ▸ and 8 ▸).

Our combined sequence and structural analysis of type 2 cysteine desulfurases suggest that while the active-site β-hairpin was previously used to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 enzymes, the β-hairpin is one piece of a larger functional unit that we term the β-latch. The existing sequence and structural data argue that the β-latch is conserved in nearly all type 2 cysteine desulfurases, including those from such diverse sources as Bacillus subtilis (PDB entry 5j8q) and Arabidopsis thaliana (PDB entry 4q75), two organisms in which SufS is essential for viability (Van Hoewyk et al., 2007 ▸; Kobayashi et al., 2003 ▸). While nearly all type 2 cysteine desulfurases appear to contain a β-latch, in cases where one of the conserved residues is absent this may indicate functional divergence, and thus the β-latch is likely to serve as a better classifier for functional grouping of cysteine desulfurases than the β-hairpin. As an example, sequence Q87DJ2, a probable cysteine desulfurase from Xylella fastidiosa and one of the representatives in our multiple sequence alignment, has diverged in sequence at both members of the electrostatic pair, suggesting that it and the sequence cluster that it is modeling behave differently from other type 2 enzymes.

Recognition of the β-latch will guide experiments to test its function, including the hypothesis that the β-latch is integral to the key functional distinction between type 2 and type 1 enzymes: the insensitivity of the type 2 class to oxidative stress (Dai & Outten, 2012 ▸).

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: SufS with a spontaneously rotated β-hairpin, 6uy5

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge F. Wayne Outten for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants GM112919, S10_RR25528 , and S10_RR028976. U.S. Department of Energy grant W-31-109-Eng-38 to Advanced Photon Source.

References

- Atkinson, H. J., Morris, J. H., Ferrin, T. E. & Babbitt, P. C. (2009). PLoS One, 4, e4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Begley, T. P., Ealick, S. E. & McLafferty, F. W. (2012). Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 555–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Black, K. A. & Dos Santos, P. C. (2015). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1853, 1470–1480. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blahut, M., Wise, C. E., Bruno, M. R., Dong, G., Makris, T. M., Frantom, P. A., Dunkle, J. A. & Outten, F. W. (2019). J. Biol. Chem. 294, 12444–12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blauenburg, B., Mielcarek, A., Altegoer, F., Fage, C. D., Linne, U., Bange, G. & Marahiel, M. A. (2016). PLoS One, 11, e0158749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bühning, M., Valleriani, A. & Leimkühler, S. (2017). Biochemistry, 56, 1987–2000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Crooks, G. E., Hon, G., Chandonia, J. M. & Brenner, S. E. (2004). Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y. & Outten, F. W. (2012). FEBS Lett. 586, 4016–4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dana, J. M., Gutmanas, A., Tyagi, N., Qi, G., O’Donovan, C., Martin, M. & Velankar, S. (2019). Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D482–D489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dunkle, J. A., Bruno, M. R., Outten, F. W. & Frantom, P. A. (2019). Biochemistry, 58, 687–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R. C. (2004). Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fernández, F. J., Ardá, A., López-Estepa, M., Aranda, J., Peña-Soler, E., Garces, F., Round, A., Campos-Olivas, R., Bruix, M., Coll, M., Tuñón, I., Jiménez-Barbero, J. & Vega, M. C. (2016). ACS Catal. 6, 3975–3984.

- Fujii, T., Maeda, M., Mihara, H., Kurihara, T., Esaki, N. & Hata, Y. (2000). Biochemistry, 39, 1263–1273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fujishiro, T., Terahata, T., Kunichika, K., Yokoyama, N., Maruyama, C., Asai, K. & Takahashi, Y. (2017). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18464–18467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Günal, S., Hardman, R., Kopriva, S. & Mueller, J. W. (2019). J. Biol. Chem. 294, 12293–12312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, J. T., Clausen, T., Bourenkow, G. P., Bartunik, H. D., Steinbacher, S. & Huber, R. (2000). J. Mol. Biol. 297, 451–464. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim, D., Singh, H., Dai, Y., Dong, G., Busenlehner, L. S., Outten, F. W. & Frantom, P. A. (2018). Biochemistry, 57, 5210–5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim, S. & Park, S. (2013). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 27172–27180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K., Ehrlich, S. D., Albertini, A., Amati, G., Andersen, K. K., Arnaud, M., Asai, K., Ashikaga, S., Aymerich, S., Bessieres, P., Boland, F., Brignell, S. C., Bron, S., Bunai, K., Chapuis, J., Christiansen, L. C., Danchin, A., Debarbouille, M., Dervyn, E., Deuerling, E., Devine, K., Devine, S. K., Dreesen, O., Errington, J., Fillinger, S., Foster, S. J., Fujita, Y., Galizzi, A., Gardan, R., Eschevins, C., Fukushima, T., Haga, K., Harwood, C. R., Hecker, M., Hosoya, D., Hullo, M. F., Kakeshita, H., Karamata, D., Kasahara, Y., Kawamura, F., Koga, K., Koski, P., Kuwana, R., Imamura, D., Ishimaru, M., Ishikawa, S., Ishio, I., Le Coq, D., Masson, A., Mauel, C., Meima, R., Mellado, R. P., Moir, A., Moriya, S., Nagakawa, E., Nanamiya, H., Nakai, S., Nygaard, P., Ogura, M., Ohanan, T., O’Reilly, M., O’Rourke, M., Pragai, Z., Pooley, H. M., Rapoport, G., Rawlins, J. P., Rivas, L. A., Rivolta, C., Sadaie, A., Sadaie, Y., Sarvas, M., Sato, T., Saxild, H. H., Scanlan, E., Schumann, W., Seegers, J. F., Sekiguchi, J., Sekowska, A., Seror, S. J., Simon, M., Stragier, P., Studer, R., Takamatsu, H., Tanaka, T., Takeuchi, M., Thomaides, H. B., Vagner, V., van Dijl, J. M., Watabe, K., Wipat, A., Yamamoto, H., Yamamoto, M., Yamamoto, Y., Yamane, K., Yata, K., Yoshida, K., Yoshikawa, H., Zuber, U. & Ogasawara, N. (2003). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 4678–4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kredich, N. M. (2008). EcoSal Plus, 3, https://doi.org/10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.1.11.

- Leimkuhler, S., Buhning, M. & Beilschmidt, L. (2017). Biomolecules, 7, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liebschner, D., Afonine, P. V., Baker, M. L., Bunkóczi, G., Chen, V. B., Croll, T. I., Hintze, B., Hung, L.-W., Jain, S., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Oeffner, R. D., Poon, B. K., Prisant, M. G., Read, R. J., Richardson, J. S., Richardson, D. C., Sammito, M. D., Sobolev, O. V., Stockwell, D. H., Terwilliger, T. C., Urzhumtsev, A. G., Videau, L. L., Williams, C. J. & Adams, P. D. (2019). Acta Cryst. D75, 861–877.

- Lima, C. D. (2002). J. Mol. Biol. 315, 1199–1208. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q., Dahmane, T., Zhang, Z., Assur, Z., Brasch, J., Shapiro, L., Mancia, F. & Hendrickson, W. A. (2012). Science, 336, 1033–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mihara, H., Kurihara, T., Yoshimura, T., Soda, K. & Esaki, N. (1997). J. Biol. Chem. 272, 22417–22424. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, R., Hikita, M., Ogawa, S., Takahashi, Y. & Fujishiro, T. (2019). FEBS J., https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15081.

- Olieric, V., Weinert, T., Finke, A. D., Anders, C., Li, D., Olieric, N., Borca, C. N., Steinmetz, M. O., Caffrey, M., Jinek, M. & Wang, M. (2016). Acta Cryst. D72, 421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patra, S. & Barondeau, D. P. (2019). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 19421–19430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Roret, T., Pégeot, H., Couturier, J., Mulliert, G., Rouhier, N. & Didierjean, C. (2014). Acta Cryst. F70, 1180–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rybniker, J., Pojer, F., Marienhagen, J., Kolly, G. S., Chen, J. M., van Gumpel, E., Hartmann, P. & Cole, S. T. (2014). Biochem. J. 459, 467–478. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P., Markiel, A., Ozier, O., Baliga, N. S., Wang, J. T., Ramage, D., Amin, N., Schwikowski, B. & Ideker, T. (2003). Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sievers, F., Wilm, A., Dineen, D., Gibson, T. J., Karplus, K., Li, W., Lopez, R., McWilliam, H., Remmert, M., Söding, J., Thompson, J. D. & Higgins, D. G. (2011). Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, H., Kopriva, S., Giordano, M., Saito, K. & Hell, R. (2011). Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 157–184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Theobald, D. L. & Steindel, P. A. (2012). Bioinformatics, 28, 1972–1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Van Hoewyk, D., Abdel-Ghany, S. E., Cohu, C. M., Herbert, S. K., Kugrens, P., Pilon, M. & Pilon-Smits, E. A. (2007). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 5686–5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C. & Dos Santos, P. C. (2018). Biochem. Soc. Trans. 46, 1593–1603. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L., White, R. H., Cash, V. L., Jack, R. F. & Dean, D. R. (1993). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 2754–2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: SufS with a spontaneously rotated β-hairpin, 6uy5