Abstract

Accumulation and detoxification of cadmium in rice shoots are of great importance for adaptation to grow in cadmium contaminated soils and for limiting the transport of Cd to grains. However, the molecular mechanisms behind the processes involved in this regulation remain largely unknown. Defensin proteins play important roles in heavy metal tolerance and accumulation in plants. In rice, the cell wall-localized defensin protein (CAL1) is involved in Cd efflux and partitioning to the shoots. In the present study, we functionally characterized the CAL2 defensin protein and determined its contribution to Cd accumulation. CAL2 shared 66% similarity with CAL1, and its mRNA accumulation is mainly observed in roots and is unaffected by Cd stress, but its transcription level was lower than that of CAL1 based on the relative expression of CAL2/Actin1 observed in this study and that reported previously. A promoter-GUS assay revealed that CAL2 is expressed in root tips. Stable expression of the CAL2-mRFP fusion protein indicated that CAL2 is also localized in the cell walls. An in vitro Cd binding experiment revealed that CAL2 has Cd chelation activity. Overexpression of CAL2 increased Cd accumulation in Arabidopsis and rice shoots, but it had no effect on the accumulation of other essential elements. Heterologous expression of CAL2 enhanced Cd sensitivity in Arabidopsis, whereas overexpression of CAL2 had no effect on Cd tolerance in rice. These findings indicate that CAL2 positively regulates Cd accumulation in ectopic overexpression lines of Arabidopsis and rice. We have identified a new gene regulating Cd accumulation in rice grain, which would provide a new genetic resource for molecular breeding.

Keywords: plant defensin, CAL2, cadmium accumulation, Arabidopsis, rice

Introduction

Excessive accumulation of cadmium (Cd), a heavy metal, can cause damage to different species (Clemens et al., 2013). China’s rapid industrialization in the past three decades has led to increasing contamination of agricultural soils with Cd, and its content in the grains of rice grown in parts of southern China has been reported to exceed Chinese safety standards. This has led to widespread concern about food safety (Wang et al., 2019). Exposure to elevated levels of Cd affects the homeostasis of essential elements, destroys the photosynthetic system, causes oxidative stress, and inhibits plant growth and development (Moulis, 2010). Excessive accumulation of Cd in the body can cause Itai-Itai disease in humans (Kazantzis, 2004). Phytoremediation combined with lower Cd content in grains could effectively address Cd pollution and its associated health hazards, and necessities comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms involved in Cd accumulation and detoxification in plants.

Numerous studies had reported on the mechanisms for detoxification and accumulation of Cd in plants. In brief, cytoplasmic chelation and vacuolar sequestration are the main detoxification pathways for Cd in plants and yeast (Song et al., 2003, 2010; Hanikenne et al., 2008; Verbruggen et al., 2009; Ueno et al., 2010; Chao et al., 2012; Park et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012). Cd accumulation in plant tissues, its uptake, and redistribution through long-distance transport are mainly mediated via transporters of essential elements (Morel et al., 2008; Korenkov et al., 2009; Wong and Cobbett, 2009; Nocito et al., 2011; Satoh-Nagasawa et al., 2011; Sasaki et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2016).

Another class of molecules that may be involved in Cd accumulation and detoxification are plant defensins, a large family of highly conserved and stable proteins that are considered natural immune molecules with a wide range of biological functions (Parisi et al., 2019). These peptides have a spherical three-dimensional structure stabilized by four disulfide bonds and share a CSαβ motif composed of an α-helix and a triple-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet (Parisi et al., 2019). Research over the past few decades revealed several functions of these molecules; for example, human defensin 5 (HD5) have Zn/Cd binding activity (Zhang et al., 2013). Other studies have shown that plant defensin gene type 1 (PDF1s) increases tolerance to zinc in yeast and plants (Mirouze et al., 2006; Shahzad et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2014; Mith et al., 2015). In addition, Cd stress was reported to significantly induce the expression of PDF1.2 in Arabidopsis, whereas Zn supply decreased its expression in a Zn/Cd hyperaccumulator, Noccaea caerulescens (Cabot et al., 2013; Gallego et al., 2016).

The Arabidopsis defensin type 2 family (PDF2s) has six members (Thomma et al., 2002). Electrophysiological studies have shown that AtPDF2.3 has potassium channel blocking activity (Kim et al., 2016). AtPDF2.5 is a Cd-induced protein that is located in cell walls of the vascular bundles in the xylem; it positively regulates Cd tolerance and accumulation by mediating the chelation and efflux of cytoplasmic Cd to the apoplast cell wall in Arabidopsis thaliana (Luo et al., 2019b). AtPDF2.6 is strongly induced by Cd stress and is located in the cytoplasm of xylem vascular bundles. By chelating cytoplasmic Cd, AtPDF2.6 can enhance the tolerance of Arabidopsis to Cd. These findings challenge the generally accepted view that defensins are secreted proteins (Luo et al., 2019a). Recent xylem sap proteomic studies revealed that plant defensins play a positive role in the Cd tolerance of Brassica napus (Luo and Zhang, 2019).

Sequencing and annotation studies identified thousands of plant defensins in rice (Kawahara et al., 2013). The quantitative trait locus of Cd accumulation in rice leaf 1 (CAL1) was map-based cloned and was found to encode a defensin-like protein (Luo et al., 2018). CAL1 was functionally characterized as a positive regulator of Cd accumulation in rice leaves (Luo et al., 2018). CAL1 is expressed preferentially in the root exodermises and xylem parenchyma cells. It is also involved in Cd chelation and secretion from the cytosol to extracellular spaces and can consequently lower the cytosolic Cd concentration and drive long-distance Cd transport via the xylem vessels (Luo et al., 2018). In this study, we functionally characterized a cell wall-localized defensin, CAL2, and determined its contribution to Cd accumulation. CAL2 was found to be the closest homolog of CAL1, and its mRNA accumulation was mainly detected in root tips and was unaffected by Cd stress. Our findings indicate that CAL2 positively regulates Cd accumulation in ectopic overexpression lines of rice and Arabidopsis, and provides a new genetic resource for molecular breeding.

Materials and Methods

Sequence Analysis and Construction of Phylogenetic Tree

Arabidopsis and rice defensin protein sequences were downloaded from the TAIR database and RAP-DB, respectively. Sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA 5 software after ClustalW alignment.

Plant Material, Growth Conditions, and Elemental Analysis

We used the wild-type rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivar, ZH11. Plants were grown in paddy fields contaminated with heavy metals and seeds were harvested at maturity. Alternatively, seeds were pretreated and uniformly germinated seeds were planted in 96-well plates with their bottoms removed. Rice seedlings were grown hydroponically in Yoshida solution (pH 5.8), as previously described (Yoshida et al., 1976), at 28°C and 60% relative humidity, with a 13-h light/11-h dark photoperiod as described earlier (Luo et al., 2018). For the Cd tolerance assay, rice seedlings were grown hydroponically for 14 days in the presence of 0 or 5 μM Cd, and then sampled to determine the fresh weights of shoot and roots. The Cd concentration in leaf, xylem sap, and root was determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, ELAN DRC-e, PerkinElmer), as previously described (Gong et al., 2003). Xylem sap was extracted and assayed as described by Luo et al. (2018).

Seeds of the wild-type A. thaliana (Col-0) and CAL2 heterologous overexpression lines were surface sterilized, germinated on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1/2 × MS) medium, containing 0.8% (w/v) sucrose, 0.1% (w/v) 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), and 0.8% (w/v) agar; and kept at 22°C under 300 μmol m–2 s–1 photosynthetically active radiation, and a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle for 7 days. Seedlings were then transferred to a quarter-strength hydroponic solution, as described previously (Arteca and Arteca, 2000; Gong et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2019b). When the plants are 4 weeks old, they were exposed to 10 μM CdCl2 for 3 days, as described by Luo et al. (2019a), after which the roots and shoots were harvested. The concentration of Cd in plant tissues was determined by ICP-MS (Gong et al., 2003). Cd tolerance and nitrate concentration were determined in 4 weeks-old plants, subjected to 20 μM CdCl2 for 3 days before tissue sampling. Nitrate was extracted and assayed as described in Li et al. (2010).

DNA Constructs and Transformation of Plants

To clone the CAL2 promoter, total DNA was extracted from ‘ZH11’ with TPS buffer (100 mM Tris-HCL pH 8.0; 10 mM EDTA pH 8.0; 1 M KCl). A 1490-bp genomic fragment immediately upstream of the CAL2 start codon was PCR-amplified using the primers, ProCAL2F and ProCAL2R (Supplementary Table S1). The resulting ProCAL2 promoter fragment was then sub-cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1300-GUS using a one-step cloning kit (C112-01, Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The pCAMBIA1300-GUS vector was recovered after HindIII/BamHI restriction digestion. To determine the subcellular localization of CAL2 in A. thaliana, the 35S:mRFP fragment was recovered from 35S:mRFP/PA7 by HindIII/SacI restriction digestion (Luo et al., 2018), and the resulting 35S:mRFP fragment was inserted into pCAMBIA1300 to generate the 35S:mRFP/pCAMBIA1300 construct. The coding sequence of CAL2, without a stop codon, was PCR-amplified using the primers CAL2F and CAL2R (Supplementary Table S1). The resulting fragments were fused in-frame to the 5′-terminus of the monomer red fluorescent protein gene (mRFP) to generate the 35S:CAL2-mRFP/pCAMBIA1300 construct, using the one-step cloning kit (C112-01, Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd). All resulting constructs were transformed into A. thaliana using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transgenic plants were screened using hygromycin B and confirmed by quantitative PCR. Alternatively, the 35S:CAL2-mRFP/pCAMBIA1300 construct was transformed into ZH11 at Wuhan Bo Yuan Biotech. Co. Ltd, as previously described (Hiei et al., 1994).

Expression Assay

Rice seedlings were grown in hydroponic solution for 2 weeks before the treatments and then sampled for further analysis. Alternatively, tissues were sampled from rice plants grown in paddy fields at the heading stage. Total RNA was extracted from the collected tissues using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA was synthesized using the PrimeScriptTM RT Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time; TAKARA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The relative expression of target genes was determined by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), performed on an Applied Biosystems StepOneTM Real-Time PCR System with SYBR Premix Ex-Taq (TAKARA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers used in these assays are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Histochemical and Subcellular Localization Analyses

To confirm the histological expression pattern of β-glucuronidase (GUS) driven by the proCAL2 promoter, histochemical staining was performed using a GUS histochemical assay kit (Real-Times, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The seedlings were grown in 1/2 MS medium for 1 week. The roots of the transgenic lines were subjected to mRFP imaging using confocal microscopy (Zeiss; LSM880).

Protein Purification and Related Assays

Fragments of ΔSPCAL2 (a truncated form of CAL2 representing the mature CAL2 protein of 33–82 amino acids, which lacks the signal peptide sequence that spans amino acids 1–32) were PCR-amplified using the primers TF-ΔSPCAL2F and TF-ΔSPCAL2R (Supplementary Table S1) and cloned into the pCold-TF vector. Expression of the recombinant proteins was induced by 0.2 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside at 16°C for 10 h. The cells were further grown for 10 h in the presence of 100 μM CdCl2 before collection, and then lysed using BugBuster Master Mix (Novagen), as previously described (Luo et al., 2018). The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 16000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was purified using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen), and free Cd was removed using Zeba Spin Desalting Columns (Thermo Scientific). Five micrograms of purified protein per sample was loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE gels and detected using Coomassie blue staining. Both procedures were performed at Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. The purified proteins were divided into two portions: one was used to measure the Cd content, using ICP-MS, and the other to measure the protein concentration (Bio-Rad, DC Protein Assay Kit). The metal-to-protein stoichiometry was calculated based on Cd and protein concentrations, as described previously (Wan and Freisinger, 2009).

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were conducted using a completely randomized design. Three independent biological samples were used as replicates and two technical replicates were used for each treatment. Data were analyzed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests and differences were deemed significant at P < 0.05 and highly significant at P < 0.01.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this study can be found in RAP-DB under the following accession number: CAL2 (Os04g0522100). Additional sequence data are available in Supplementary Table S1.

Results

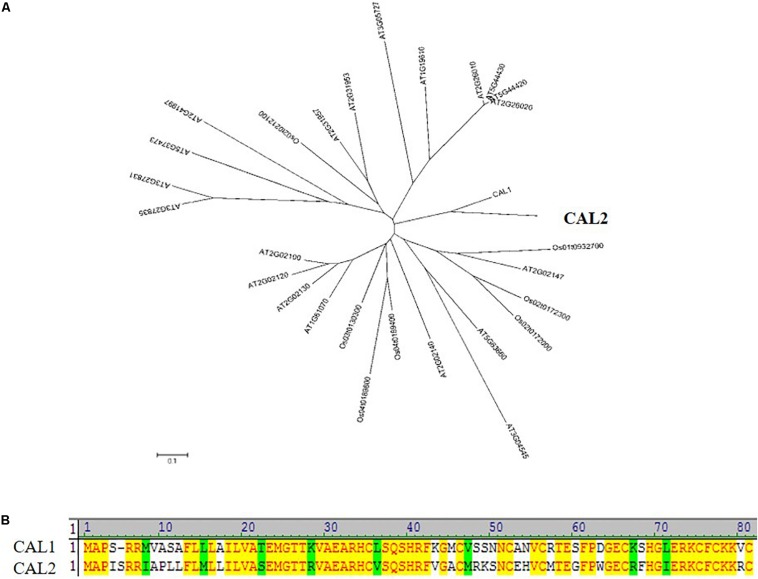

CAL2 Is the Closest Homolog of CAL1

CAL2 showed a high degree of similarity to CAL1 (Figure 1A), with 66% of the sequences being identical (Figure 1B). The CAL2 sequence comprised 82 amino acid residues (9.4 kDa). Bioinformatics analysis indicated that CAL2 contains an N-terminal signal peptide and a C-terminal cysteine-rich domain. The signal peptide cleavage site is between amino acid residues 32 and 33 (Supplementary Figure S1).

FIGURE 1.

CAL2 is the closest homolog of CAL1. (A) Phylogenetic relationship of defensin proteins in rice and Arabidopsis thaliana. The 0.1 scale shows substitution distance. (B) Alignment of CAL1 and CAL2 proteins.

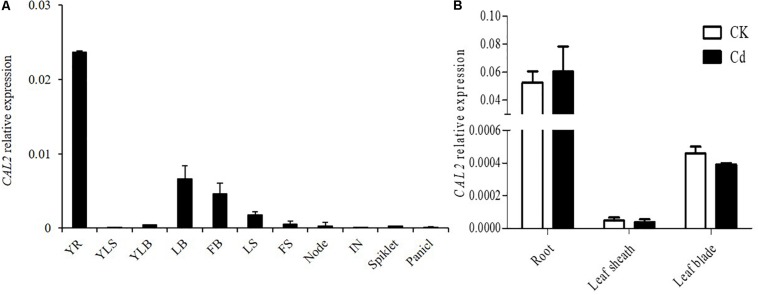

CAL2 Is Mainly Expressed in Roots and Does Not Respond to Cd Stress at the mRNA Level

The expression of CAL2 was investigated in different tissues at the seeding and flowering stages. Quantitative RT-PCR results showed that CAL2 was mainly expressed in the roots (Figure 2A). To investigate whether the expression of CAL2 is affected by Cd stress, we exposed the rice seedlings to solutions containing 0 or 100 μM of Cd. The expression of CAL2 was not significantly changed in roots, leaf sheaths, and leaf blades exposed to either solution (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Expression pattern of CAL2. (A) CAL2 expression in various rice tissues. YR, young root; YLS, young leaf sheath; YLB, young leaf blade; LB, leaf blade; FB, flag leaf blade; LS, leaf sheath; FS, flag leaf sheath; IN, internode. (B) CAL2 expression in roots of 2-week-old seedlings treated with Cd at 0 or 100 μM Cd for 6 h. Data are means ± standard deviations of three independent biological replicates and normalized to Actin1.

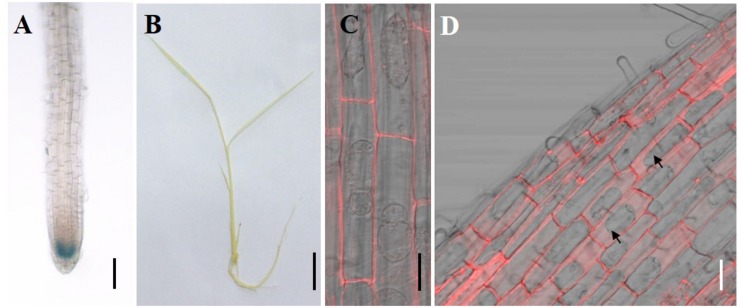

Tissue Specific Expression and Subcellular Localization of CAL2

To investigate the tissue specificity of CAL2 expression, we determined the expression pattern of CAL2 by histochemical analysis of GUS expression driven by the CAL2 promoter. Consistent with the quantitative RT-PCR results, GUS activity was mainly detected in the root tips (Figure 3A), whereas it was not detected in the leaf sheaths and leaf blades (Figure 3B). To determine subcellular localization, we transformed CAL2:mRFP into Arabidopsis and rice under the control of the 35S promoter. The fluorescence produced by the mRFP fusion protein was detected in the cell wall (Figures 3C,D).

FIGURE 3.

Tissue specificity expression and subcellular localization assay. (A,B) Histochemical assay of CAL2 promoter GUS activity in 14-day-old rice seedlings. (C,D) Subcellular localization of CAL2 in Arabidopsis (C) and rice (D) plants harboring the construct 35S:CAL2-mRFP. 7-day-old seedling root epidermal cells were incubated in 40% sucrose to induce plasmolysis and then imaged by confocal microscopy. The arrows indicate the plasmolyzed cells. Scale bars = 2 mm in (A), 1 cm in (B), and 20 μm in (C,D). Two independent transgenic lines were used in (A–D) and showed similar results.

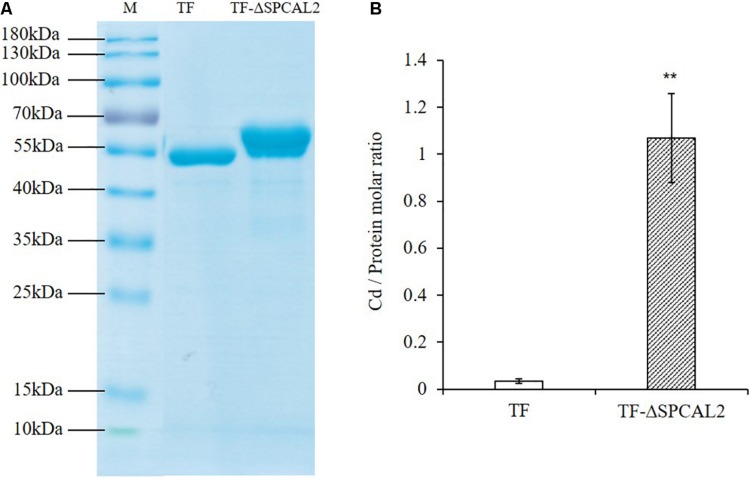

CAL2 Has Cd Binding Activity

CAL2 encodes a small cysteine-rich peptide that contains eight cysteine residues at the C-terminus and may have Cd chelating activity. To test this hypothesis, we expressed and purified recombinant TF-CAL2 proteins in Escherichia coli cells treated with Cd. TF is a prokaryotic ribosomal binding chaperone protein that facilitates the co-translation and folding of newly synthesized peptide chains. Compared with tags from other biological sources, TF has higher expression efficiency and better solubility in E. coli (Luo et al., 2019a). Coomassie blue staining results indicated that we successfully purified TF; and TF fused to the N-terminus of the signal peptide-deleted CAL2 (TF-ΔSPCAL2) proteins from E. coli transformants treated with 100 μM CdCl2 (Figure 4A). The ICP-MS analysis showed that TF-ΔSPCAL2 has Cd chelating activity; the binding molar ratio of TF-ΔSPCAL2 to Cd is 1 (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

In vitro Cd binding assay. (A) Escherichia coli trigger factor (TF) and TF fused to the N terminus of the signal peptide-deleted CAL2 (TF-ΔSPCAL2) purified from E. coli. (B) The molar ratio of Cd against TF-ΔSPCAL2 protein purified from E. coli cells grown with 100 μM CdCl2. Data are mean ± standard deviations of three independent biological replicates. Significant differences were determined by Student’s t-test (**P < 0.01).

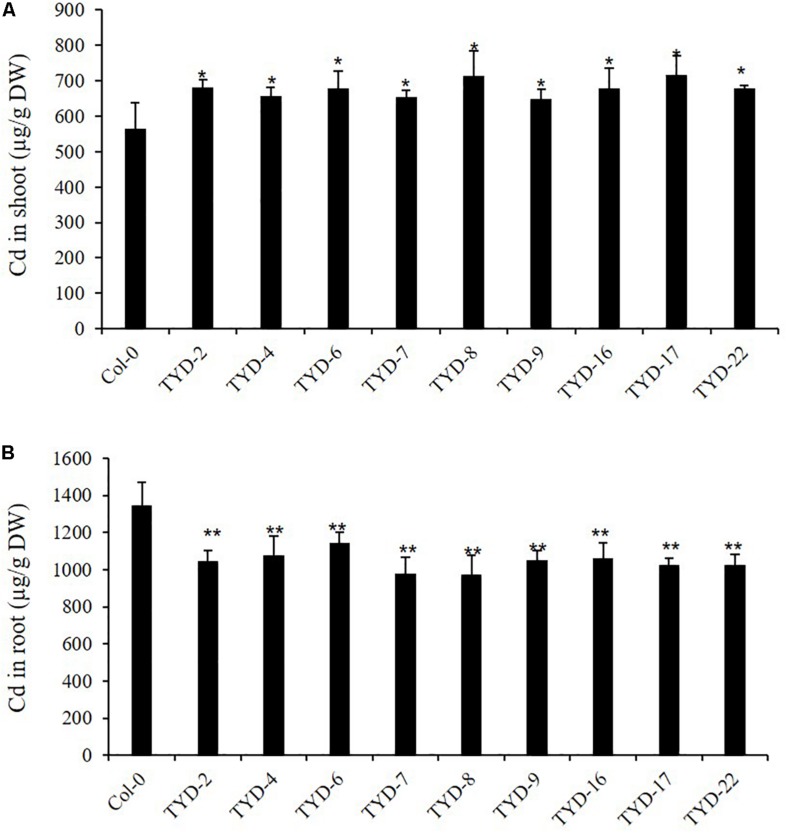

Heterologous Expression of CAL2 Increases Cd Allocation to Shoot in Arabidopsis

Next, we studied the effect of heterologous overexpression of CAL2 on metal transport and distribution in A. thaliana. We first detected the transcription level of CAL2 in the homozygously overexpressing A. thaliana lines and found that the expression level of CAL2 was significantly higher than that in the wild-type Col-0 plants (Supplementary Figure S2A). Four-week old hydroponically grown 35S:CAL2-mRFP transgenic and wild-type Col-0 plants were exposed to 10 μM Cd for 3 days. Compared with that in the wild-type Col-0, the heterologous overexpression of CAL2 significantly increased the accumulation of Cd in Arabidopsis shoots (Figure 5A), while the concentration of Cd in roots decreased significantly (Figure 5B). There was no difference in the concentration of other essential metals between the wild-type Col-0 and Arabidopsis plants heterologously overexpressing CAL2 (Supplementary Figure S2B). These data indicate that CAL2 may positively regulate Cd allocation in Arabidopsis.

FIGURE 5.

Ectopic expression of CAL2 increased Cd allocation to shoot in Arabidopsis. Four weeks old 35S:CAL2-mRFP transgenic plants were exposed to 10 μM Cd for 3 days. (A) Heterologous overexpression of CAL2 increased Cd concentration in Arabidopsis shoots. (B) Heterologous overexpression of CAL2 decreased Cd concentration in Arabidopsis roots. Data are mean ± standard deviations of three independent biological replicates. Significant differences from Col-0 were determined by Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

We selected representative transgenic lines expressing CAL2 for the Cd tolerance assay. When hydroponically grown without Cd, transgenic lines TYD-6 and TYD-7 showed similar growth as the wild-type Col-0 (Supplementary Figure S3A). However, when 4-week-old hydroponically grown 35S:CAL2-mRFP transgenic and wild-type Col-0 plants were exposed to 20 μM Cd for 3 days, the TYD-6 and TYD-7 lines showed greater Cd sensitivity than the wild-type control plants (Supplementary Figure S3A). Previous research revealed that Cd/Na stress influences nitrate allocation to the roots, which is regulated by the nitrate transporters, NRT1.8 and NRT1.5, and functions in promoting stress tolerance (Li et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2014, 2018). To investigate the potential mechanisms of cadmium sensitivity, nitrate concentrations in A. thaliana shoots and roots were measured and normalized to fresh weight under different growth conditions. Under control conditions, the root/shoot nitrate ratio was similar in Col-0, TYD-6, and TYD-7 plants (Supplementary Figure S3B). However, when plants were exposed to 20 μM Cd for 3 days, the root/shoot nitrate ratio significantly decreased in the TYD-6 and TYD-7 plants, compared to that in the wild-type Col-0 plants (Supplementary Figure S3B). These results indicate that CAL2 may negatively regulate the root/shoot nitrate ratio under Cd stress conditions to decrease Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis.

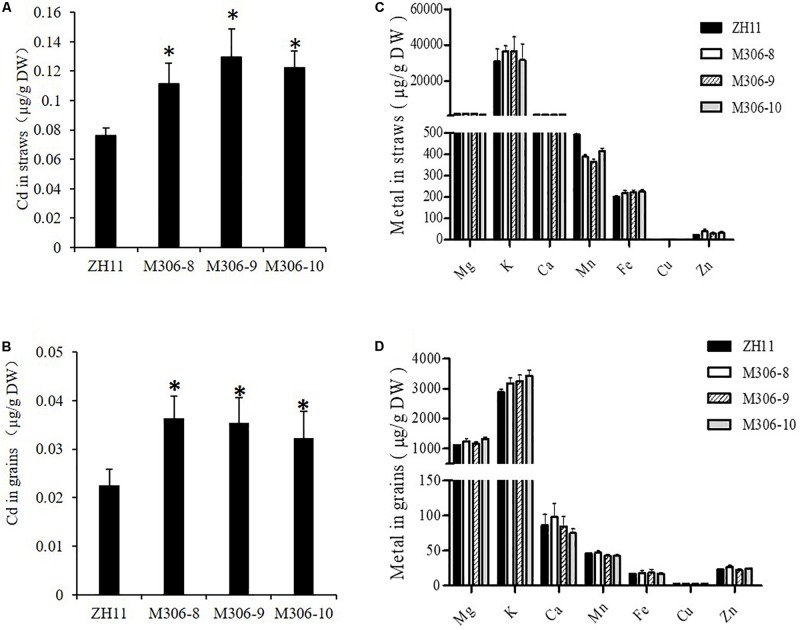

Overexpression of CAL2 Increases Cd Accumulation in Rice

To study the role of CAL2 in rice, we overexpressed it in a representative rice cultivar (ZH11) under the control of the 35S promoter and selected three representative overexpression lines for further experiments (Supplementary Figure S4). Compared with the transgenic negative control ZH11, the Cd concentration in straw and seeds significantly increased in the CAL2-overexpression lines, when grown in a Cd-contaminated field (Figures 6A,B). There was no difference in the concentration of other essential metals in the straw and seeds between the transgenic negative control ZH11 and CAL2-overexpression lines (Figures 6C,D).

FIGURE 6.

Overexpression of CAL2 increased Cd accumulation in rice. Transgene-negative control ZH11 and 35S:CAL2-mRFP transgenic plants were grown in a heavy metal contaminated paddy field until ripening. Heterologous overexpression of CAL2 increased cadmium (Cd) accumulation in rice straws (A) and grains (B). (C,D) Essential mineral nutrients accumulation in (C) rice straws and (D) grains. Data are means ± SDs of three independent biological replicates. Significant differences from ZH11 were determined by Student’s t-test (∗P < 0.05).

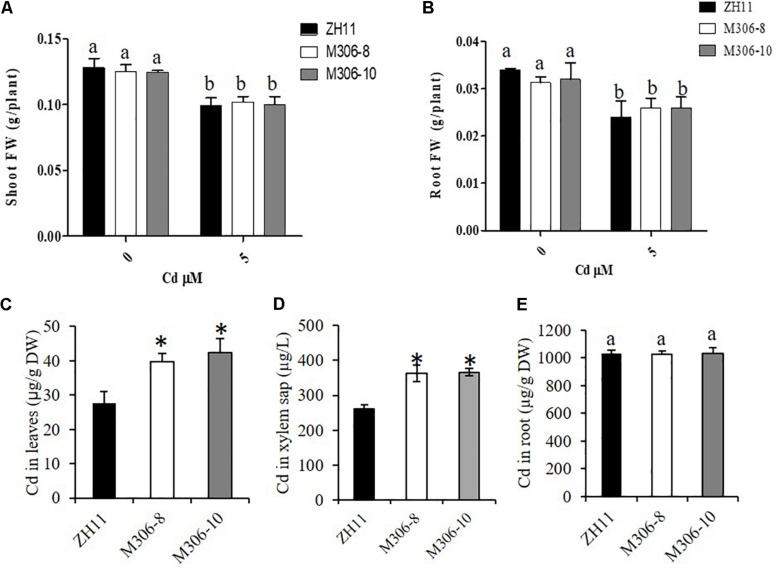

Cd tolerance was determined in two randomly selected CAL2-overexpression lines and a transgene-negative control, ZH11. Rice seedlings were grown hydroponically for 14 days in a solution supplemented with 0 or 5 μM Cd. The results revealed that the CAL2-overexpression transgenic lines, M306-8 and M306-10, had similar fresh weights as the wild-type ZH11 under 0 or 5 μM Cd treatment conditions (Figures 7A,B). Results of our previous studies suggested that the defensin-like protein, CAL1, mediates the efflux and partitioning of Cd in rice (Luo et al., 2018), but whether this protein can regulate Cd tolerance remains unknown. A Cd tolerance assay also performed using cal1 mutants and the wild-type control, TN1; the cal1 mutants were generated by CRISPER/Cas9 as reported by Luo et al. (2018). The results suggest that the cal1 mutants have similar fresh weights of shoots and roots as the wild-type TN1 under 0 or 5 μM Cd treatments (Supplementary Figure S5). Compared with that in the transgenic negative control, ZH11, the concentration of Cd in leaves and xylem sap significantly increased in the CAL2-overexpression lines (Figures 7C,D); however, there was no significant differences in root Cd content between the CAL2-overexpression lines and the transgenic negative control, ZH11 (Figure 7E). These results indicate that CAL2 positively regulates Cd accumulation, but has no effect on Cd tolerance in rice.

FIGURE 7.

Cd tolerance assays of CAL2 overexpression lines. Transgene-negative control ZH11 and 35S:CAL2-mRFP transgenic rice seedlings were grown for 14 days in hydroponics supplemented with 0 or 5 μM Cd, and then sampled to determine fresh weights (FW) of shoot (A) and roots (B), Cd concentration in leaves (C), xylem sap (D) and roots (E) were determined by ICP-MS. Data are mean ± SDs of three independent biological replicates. Bars with the same letters are not significantly different at P < 0.05 using the LSD method. Significant differences from ZH11 were determined by Student’s t test (∗P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we functionally identified CAL2, the closest homolog of CAL1, which belongs to the plant defensins and mediates Cd accumulation in rice and Arabidopsis. CAL2 has Cd binding activity and is localized in the cell wall similar to CAL1 (Figures 3, 4). Our results indicate that CAL2 probably regulates Cd accumulation via a mechanism similar to that used by CAL1 in ectopically overexpression rice and Arabidopsis lines. CAL1 is expressed preferentially in the root exodermis and xylem parenchyma cells. It is involved in Cd chelation and secretion from the cytosol to the extracellular spaces, and consequently it lowers the cytosolic Cd concentration and drive long-distance Cd transport via the xylem vessels (Luo et al., 2018).

CAL1 specifically regulated Cd allocation to rice leaves and straw, and had no effect on Cd accumulation in rice grains. However, overexpression of CAL2 positively regulated Cd accumulation in the leaves, straw, and grains of rice. CAL1 and CAL2 show different tissue-specific expression. CAL1 responded to Cd stress at the mRNA level, but CAL2 did not.

A previous review article suggested that the small peptide expressed in the root tips of A. thaliana regulates the initiation and elongation of lateral roots and the maintenance of root apical meristem through a receptor kinase-signaling pathway (Grienenberger and Fletcher, 2015). CAL2 is mainly expressed in the root tips and may act as a peptide signal to control the growth and development of plant roots. However, when plants suffer from Cd stress, CAL2 may also regulate gene expression for the transport of Cd to adapt to this stress. This requires further studies using genetic assays to fully understand the mechanisms involved.

In our opinion, CAL2 possesses Cd chelation activity, and may enhance Cd tolerance when heterologously expressed in Arabidopsis; however, our experimental data in this study (Supplementary Figure S3A) suggest that Arabidopsis plants heterologously expressing CAL2 exhibit a Cd-sensitive phenotype. This is an unexpected phenomenon, which might be due to the side effects caused by heterologous overexpression of the CAL2 gene driven by the 35S promoter, high Cd accumulation in shoots of CAL2-overexpression lines (Figure 4A), or Cd/Na stress mediating nitrate allocation to roots, which promotes stress tolerance (Li et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2014, 2018). Our results indicate that CAL2 may negatively regulate the root/shoot nitrate ratio under Cd stress conditions to decrease Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis (Supplementary Figure S3). We speculate that in ectopically overexpression plants, CAL2 may act as a signal molecule to regulate the expression levels of genes involved in the long-distance transport of nitrate, namely NRT1.5 and NRT1.8, which affect the distribution of nitrate between shoots and roots, and thus, affect the tolerance of plants to Cd. CAL2 specifically regulates Cd accumulation (Figure 6), but has no effect on Cd tolerance in rice. This provides a new molecular tool for controlling Cd accumulation in rice and could be used for phytoremediation in other crop species.

Conclusion

In this study, we functionally characterized the defensin protein, CAL2, and determined its contribution to Cd accumulation. CAL2 shares 66% identity with CAL1, is expressed mainly in roots, and is unaffected by Cd stress. The promoter-GUS assay showed that CAL2 is expressed in root tips. The results of transient expression of the CAL2-mRFP fusion protein indicated that CAL2 is localized to the cell wall. The in vitro Cd binding experiment revealed that CAL2 have Cd chelation activity. Our findings indicate that CAL2 positively regulates Cd accumulation in ectopically overexpression lines of rice and Arabidopsis, and could play a potential role in phytoremediation in other species.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

J-SL and ZZ designed the experiments and analyzed the data. J-SL performed most of the experiments. J-SL, AI, and ZZ wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the initial design of the project, and read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Can Peng (Core Facility, the Institute of Subtropical Agriculture, the Chinese Academy of Sciences) for helping with confocal microscopy.

Abbreviations

- CAL1

cadmium accumulation in leaf 1

- HD5

human defensin 5

- ICP-MS

inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- mRFP

monomer red fluorescent protein gene

- PDF2s

defensin type 2 genes

- RT-qPCR

quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was financially supported in part, by Province Key R&D Program of Hunan (2018NK1010); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31800202); National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0200100 and 2017YFD0200103); Hunan Provincial Recruitment Program of Foreign Experts; Double First-Class Construction Project of Hunan Agricultural University (kxk201801005); the National Oilseed Rape Production Technology System of China; “2011 Plan” supported by The Chinese Ministry of Education; and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Agricultural University (19QN38).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00217/full#supplementary-material

References

- Arteca R. N., Arteca J. M. (2000). A novel method for growing Arabidopsis thaliana plants hydroponically. Physiol. Plant. 108 188–193. 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2000.108002188.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabot C., Gallego B., Martos S., Barcelo J., Poschenrieder C. (2013). Signal cross talk in Arabidopsis exposed to cadmium, silicon, and Botrytis cinerea. Planta 237 337–349. 10.1007/s00425-012-1779-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao D. Y., Silva A., Baxter Huang Y. S., Nordborg M., Danku J., Lahner B., et al. (2012). Genome-wide association studies identify heavy metal ATPase3 as the primary determinant of natural variation in leaf cadmium in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002923. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S., Aarts M. G., Thomine S., Verbruggen N. (2013). Plant science: the key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning. Trends Plant Sci. 18 92–99. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego B., Martos S., Cabot C., BarcelÓ J., Poschenrieder C. (2016). Zinc hyperaccumulation substitutes for defense failures beyond salicylate and jasmonate signaling pathways of Alternaria brassicicola attack in Noccaea caerulescens. Physiol. Plant 159 401–415. 10.1111/ppl.12518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J. M., Lee D. A., Schroeder J. I. (2003). Long-distance root-to-shoot transport of phytochelatins and cadmium in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 10118–10123. 10.1073/pnas.1734072100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grienenberger E., Fletcher J. C. (2015). Polypeptide signaling molecules in plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 23 8–14. 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanikenne M., Talke I. N., Haydon M. J., Lanz C., Nolte A., Motte P., et al. (2008). Evolution of metal hyperaccumulation required cisregulatory changes and triplication of HMA4. Nature 453 391–395. 10.1038/nature06877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y., Ohta S., Komari T., Kumashiro T. (1994). Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequenceanalysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J 6 271–282. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6020271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Zhang Y., Peng J. S., Zhong C., Yi H. Y., Ow D. W., et al. (2012). Fission yeast HMT1 lowers seed cadmium through phytochelatin-dependent vacuolar sequestration in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158 1779–1788. 10.1104/pp.111.192872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y., de la Bastide M., Hamilton J. P., Kanamori H., McCombie W. R., Ouyang S., et al. (2013). Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice 6:4. 10.1186/1939-8433-6-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis G. (2004). Cadmium, osteoporosis and calcium metabolism. Biometals 17 493–498. 10.1023/b:biom.0000045727.76054.f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim V., Steve P., Barbara D. C., Jan T., Cammue B. P. A., Karin T. (2016). The antifungal plant defensin AtPDF2.3 from Arabidopsis thaliana blocks potassium channels. Sci. Rep. 6:3212. 10.1038/srep32121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenkov V., King B., Hirschi K., Wagner G. J. (2009). Root-selective expression of AtCAX4 and AtCAX2 results in reduced lamina cadmium in field-grown Nicotiana tabacum L. Plant Biotechnol. J. 7 219–226. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Y., Fu Y. L., Pike S. M., Bao J., Tian W., Zhang Y., et al. (2010). The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.8 functions in nitrate removal from the xylem sap and mediates cadmium tolerance. Plant Cell 22 1633–1646. 10.1105/tpc.110.075242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. S., Gu T. Y., Yang Y., Zhang Z. H. (2019a). A non-secreted plant defensin AtPDF2.6 conferred cadmium tolerance via its chelation in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 100 561–569. 10.1007/s11103-019-00878-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. S., Huang J., Zeng D. L., Peng J. S., Zhang G. B., Ma H. L., et al. (2018). A defensin-like protein drives cadmium efflux and allocation in rice. Nat. Commun. 9:645. 10.1038/s41467-018-03088-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. S., Yang Y., Gu T. Y., Wu Z. M., Zhang Z. H. (2019b). The Arabidopsis defensin gene AtPDF2.5 mediates cadmium tolerance and accumulation. Plant Cell Environ. 9 2681–2695. 10.1111/pce.13592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. S., Zhang Z. H. (2019). Proteomic changes in the xylem sap of Brassica napus under cadmium stress and functional validation. BMC Plant Biol. 19:280. 10.1186/s12870-019-1895-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirouze M., Sels J., Richard O., Czernic P., Loubet S., Jacquier A., et al. (2006). A putative novel role for plant defensins: a defensin from the zinc hyper-accumulating plant. Arabidopsis halleri, confers zinc tolerance. Plant J. 47 329–342. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2006.02788.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mith O., Benhamdi A., Castillo T., Bergé M., MacDiarmid C. W., Steffen J., et al. (2015). The antifungal plant defensin AhPDF1.1b is a beneficial factor involved in adaptive response to zinc overload when it is expressed in yeast cells. Microbiologyopen 4 409–422. 10.1002/mbo3.248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel M., Crouzet J., Gravot A., Auroy P., Leonhardt N., Vavasseur A., et al. (2008). AtHMA3, a P1B-ATPase allowing Cd/Zn/Co/Pb vacuolar storage in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 149 894–904. 10.1104/pp.108.130294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulis J. M. (2010). Cellular mechanisms of cadmium toxicity related to the homeostasis of essential metals. Biometals 23 877–896. 10.1007/s10534-010-9336-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen N. N., Ranwez V., Vile D., Soulié M. C., Dellagi A., Expert D., et al. (2014). Evolutionary tinkering of the expression of PDF1s suggests their joint effect on zinc tolerance and the response to pathogen attack. Front. Plant Sci. 5:70. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocito F. F., Lancilli C., Dendena B., Lucchini G., Sacchi G. A. (2011). Cadmium retention in rice roots is influenced by cadmium availability, chelation and translocation. Plant Cell Environ. 34 994–1008. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi K., Shafee T. M. A., Quimbar P., van der Weerden N. L., Bleackley M. R., Anderson M. A. (2019). The evolution, function and mechanisms of action for plant defensins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 88 107–118. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Song W. Y., Ko D., Eom Y., Hansen T. H., Schiller M., et al. (2012). The phytochelatin transporters AtABCC1 and AtABCC2 mediate tolerance to cadmium and mercury. Plant J 69 278–288. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04789.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A., Yamaji N., Yokosho K., Ma J. F. (2012). Nramp5 is a major transporter responsible for manganese and cadmium uptake in rice. Plant Cell 24 2155–2167. 10.1105/tpc.112.096925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Nagasawa N., Mori M., Nakazawa N., Kawamoto T., Nagato Y., Sakurai K., et al. (2011). Mutations in rice (Oryza sativa) heavy metal ATPase 2 (OsHMA2) restrict the translocation of Zn and Cd. Plant Cell Physiol. 53 213–224. 10.1093/pcp/pcr166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad Z., Ranwez V., Fizames C., Marquès L., Le Martret B., Alassimone J., et al. (2013). A Plant defensin type 1 (PDF1):protein promiscuity and expression variation within the Arabidopsis genus shed light on zinc tolerance acquisition in Arabidopsis halleri. New Phytol. 200 820–833. 10.1111/nph.12396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W. Y., Park J., Mendoza-Cózatl D. G., Suter-Grotemeyer M., Shim D., Hörtensteiner S., et al. (2010). Arsenic tolerance in Arabidopsis is mediated by two ABCC type phytochelatin transporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 21187–21192. 10.1073/pnas.1013964107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W. Y., Sohn E. J., Martinoia E., Lee Y. J., Yang Y. Y., Jasinski M., et al. (2003). Engineering tolerance and accumulation of lead and cadmium in transgenic plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 21 914–919. 10.1038/nbt850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R., Ishimaru Y., Shimo H., Ogo Y., Senoura T., Nishizawa N. K., et al. (2012). The OsHMA2 transporter is involved in root-to-shoottranslocation of Zn and Cd in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 35 1948–1957. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma B. P., Cammue B. P., Thevissen K. (2002). Plant defensins. Planta 216 193–202. 10.1007/s00425-002-0902-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno D., Yamaji N., Kono I., Huang C. F., Ando T., Yano M., et al. (2010). Gene limiting cadmium accumulation in rice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 16500–16505. 10.1073/pnas.1005396107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen N., Hermans C., Schat H. (2009). Mechanisms to cope with arsenic or cadmium excess in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12 364–372. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan X., Freisinger E. (2009). The plant metallothionein 2 from Cicer arietinum forms a single metal-thiolate cluster. Metallomics 1 489–500. 10.1039/b906428a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Chen H., Kopittke P. M., Zhao F. J. (2019). Cadmium contamination in agricultural soils of China and the impact on food safety. Environ. Pollut. 249 1038–1048. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. K., Cobbett C. S. (2009). HMA P-type ATPases are the major mechanism for root-to-shoot Cd translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 181 71–78. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Wang P., Wang P., Yang M., Lian X., Tang Z., et al. (2016). A loss-of-function allele of OSHMA3 associated with high cadmium accumulation in shoots and grain of japonica rice cultivars. Plant Cell Environ. 39 1941–1954. 10.1111/pce.12747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Zhang Y., Zhang L., Hu J., Zhang X., Lu K., et al. (2014). OsNRAMP5 contributes to manganese translocation and distribution in rice shoots. J. Exp. Bot. 65 4849–4861. 10.1093/jxb/eru259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S., Forno D. A., Cock J. H., Gomez K. A. (1976). Laboratory manual for physical studies of rice. Los Baños: IRRI. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. B., Meng S., Gong J. M. (2018). The expected and unexpected roles of nitrate transporters in plant abiotic stress resistance and their regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 9:19. 10.3390/ijms19113535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. B., Yi H. Y., Gong J. M. (2014). The Arabidopsis ethylene/jasmonic acid-NRT signaling module coordinates nitrate reallocation and the trade-off between growth and environmental adaptation. Plant Cell 26 3984–3998. 10.1105/tpc.114.129296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cougnon F. B., Wanniarachch Y. A., Hayden J. A., Nolan E. M. (2013). Reduction of human defensin 5 affords a high-affinity zincchelating peptide. ACS Chem. Biol. 8 1907–1911. 10.1021/cb400340k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.