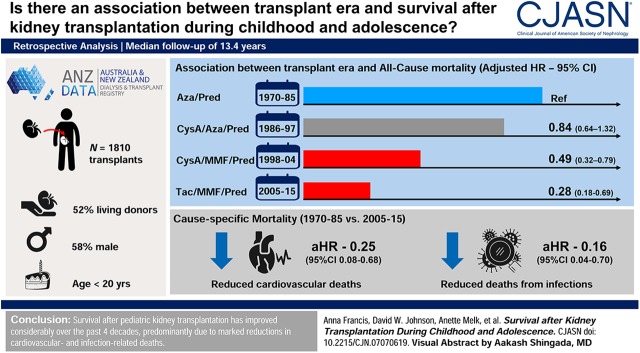

Visual Abstract

Keywords: children, transplantation, transplant outcomes, survival, child, adolescent, male, humans, kidney transplantation, survival rate, living donors, renal dialysis, New Zealand, retrospective studies, registries, risk, neoplasms, proportional hazards models

Abstract

Background and objectives

Survival in pediatric kidney transplant recipients has improved over the past five decades, but changes in cause-specific mortality remain uncertain. The aim of this retrospective cohort study was to estimate the associations between transplant era and overall and cause-specific mortality for child and adolescent recipients of kidney transplants.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Data were obtained on all children and adolescents (aged <20 years) who received their first kidney transplant from 1970 to 2015 from the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. Mortality rates were compared across eras using Cox regression, adjusted for confounders.

Results

A total of 1810 recipients (median age at transplantation 14 years, 58% male, 52% living donor) were followed for a median of 13.4 years. Of these, 431 (24%) died, 174 (40%) from cardiovascular causes, 74 (17%) from infection, 50 (12%) from cancer, and 133 (31%) from other causes. Survival rates improved over time, with 5-year survival rising from 85% for those first transplanted in 1970–1985 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 81% to 88%) to 99% in 2005–2015 (95% CI, 98% to 100%). This was primarily because of reductions in deaths from cardiovascular causes (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.25; 95% CI, 0.08 to 0.68) and infections (aHR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.70; both for 2005–2015 compared with 1970–1985). Compared with patients transplanted 1970–1985, mortality risk was 72% lower among those transplanted 2005–2015 (aHR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.69), after adjusting for potential confounders.

Conclusions

Survival after pediatric kidney transplantation has improved considerably over the past four decades, predominantly because of marked reductions in cardiovascular- and infection-related deaths.

Introduction

The prevalence of ESKD during childhood or adolescence is around 65 per million age-related population (1). Because of superior quality of life, overall survival, and neurocognitive function, and lower medical morbidity (e.g., cardiovascular disease), transplantation is preferred to dialysis for the treatment of ESKD (2–4). However, transplantation remains associated with significant morbidity and mortality (5).

Although mortality among pediatric kidney transplant recipients has improved in recent years, it is not clear how cause-specific mortality has changed over time. In Canada and the United States, 10-year mortality post kidney transplant halved, from 14% to 20% for those transplanted in the late 1980s and early 1990s to 7%–10% in the early 2000s (4,6–8). The magnitude of improvement was greater than expected when compared with changes in childhood mortality in the general population (9). However, there are conflicting data regarding whether causes of death have changed over time, with one single-center study reporting a predominance of infection-related mortality for children transplanted from 1963 to 1983, changing to cardiovascular-related mortality for children transplanted after 1983 (6). In contrast, another study found no difference in causes of death between 1990 and 2010 (7).

The aims of this study were to characterize changes over calendar time in all-cause and cause-specific mortality after a first kidney transplant for children and adolescents and to identify factors associated with all-cause mortality.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Setting

This registry-based cohort study included all recipients of a first kidney transplant, aged 19 years or under, in Australia and New Zealand between 1970 and 2015. Patients with multiorgan transplants (e.g., kidney and liver) were excluded. Patients transplanted for the first time before 1970 were excluded because of the high mortality rates in this early period. Deidentified data were derived from the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA). ANZDATA stores donor and recipient data for all transplants performed in Australia or New Zealand since 1963. Data are voluntarily provided by individual nephrology units on a yearly basis, with an opt-out system of consent; the enrolment rate for patients across Australia and New Zealand is >99%, thereby reducing the risk of selection bias. The study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 2018/960) and was conducted in accordance with Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (10). The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul as outlined in the “Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism.”

Variables of Interest

The primary exposure was transplant era of first transplant. Era was defined according to the predominant baseline immunosuppression used. From 1970 to 1985, the most common regimen was azathioprine and prednisone, changing to cyclosporine/azathioprine/prednisone (1986–1997), then to cyclosporine/mycophenolate/prednisone (1998–2004), and finally to tacrolimus/mycophenolate/prednisone (2005–2015) (Supplemental Figure 1).

Potential confounders including patient-related (sex, age at transplant, race, maximum panel reactive antibody, and duration of dialysis before transplant), transplant-related (induction agent, HLA matching), and donor-related (donor source, age, and sex) factors were considered. When no induction agent was recorded in ANZDATA, it was unclear if there was none given or the data were missing, hence a null value was coded as “none or missing.”

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, with the secondary outcome of cause-specific mortality (cardiovascular, infection, malignancy, and other). Causes of cardiovascular death included cardiac arrest, cardiac failure, heart failure, pulmonary edema, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, aortic aneurysm rupture, and stroke.

Statistical Analyses

The cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality was calculated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, stratified by transplant era. The cumulative incidence of cause-specific mortality was calculated using the Fine and Gray method, with death from other causes treated as competing risks (11). Cause-specific mortality was compared across transplant eras using the Gray k-sample test for equality of cumulative incidence functions.

The association between transplant era and mortality was estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. Transplant era, the exposure, was specified a priori to remain in the model. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator method for variable selection was utilized (12) with postselection adjustment of P values and confidence intervals (13). The proportional hazards assumptions in the Cox models were checked by fitting log (time)-dependent covariates and by plotting the Schoenfeld residuals. Interactions between transplant era and each of age at transplant and causes of ESKD were explored using interaction terms, neither of which were significant. The association between era and cardiovascular mortality was assessed using both models in which observation was censored at death from other cause and competing risks models (14). Results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

For all analyses, time zero was the time of transplantation, with censoring occurring for those lost to follow-up or still alive at December 31, 2015. Patients continued to be observed regardless of transplant function; therefore, patients could experience transplant failure and retransplantation during follow-up. The survival curves represent the unadjusted patient survival estimates (cumulative survival function) for patients who received their first transplant in each era. For the Cox regression analyses exploring associations between transplant era and death, transplant status was treated as a time-varying variable (functioning versus failed/on dialysis) to account for the differing mortality risks associated with transplant function versus being on dialysis. All patients started observation with function; status was changed to failed/on dialysis upon transplant failure and to functioning upon retransplantation. Age at transplant was categorized into three groups (<2, 2–11, and 12–19 years). Although the univariable relationship between age (as an untransformed variable) and mortality was linear (Supplemental Figure 2), categorical age groups were chosen as prior literature indicated an association with increased mortality for the very young and teenagers (15,16).

All-cause and cause-specific mortality rates were calculated as deaths per 1000 patient-years at risk for each of the first 10 years after transplantation. For the comparison of mortality rates (events per 1000 patient-years) by era in each year after first transplant, eras were collapsed into 1970–1997 (azathioprine and prednisone with or without cyclosporine) and 1998–2015 (mycophenolate, prednisone, and tacrolimus or cyclosporine) because of the low numbers of deaths in the more recent transplant eras.

Data were analyzed using Python (17), SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and R (18), with P values <0.05 considered significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

During the study period 1970–2015, there were 1810 kidney transplant recipients, followed for a median of 13.4 years (interquartile range [IQR], 5.5–24.0 years), resulting in 27,895 person-years of follow-up. The majority of this time (22,502 years, 81%) was spent with a functioning transplant. There were 451 recipients (25%) with two transplants, 120 (7%) with three transplants, 33 (2%) with four transplants, and four people (0.2%) who received five kidney transplants. Patient flow is documented in Supplemental Figure 3.

Overall, 1045 (58%) patients were male, 1506 (84%) were white, and median age at transplant was 14 years (IQR, 9–17 years). As shown in Table 1, there were 483 patients who received a first transplant from 1970 to 1985 (76% on azathioprine and prednisone at baseline), 494 in 1986–1997 (77% on cyclosporine, azathioprine, and prednisone), 293 in 1998–2004 (58% on cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisone), and 540 in 2005–2015 (82% on tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone) (Supplemental Figure 1). As time progressed, the proportion of white patients decreased (93% in 1970–1985 versus 75% in 2015–2015), whereas there were increased proportions of patients aged 2–10 years (15% in 1970–1985 compared with 39% in 2015–2015) and living donor recipients (27% in 1970–1985 compared with 68% in 2015–2015).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at the time of first transplant, stratified by transplant era

| Variable | Transplant Era | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970–1985, N=483, n (%) | 1986–1997, N=494, n (%) | 1998–2004, N=293, n (%) | 2005–2015, N=540, n (%) | |

| Female | 207 (43) | 201 (43) | 117 (40) | 231 (43) |

| White race/ethnicity | 449 (93) | 411 (84) | 246 (84) | 400 (75) |

| Age at transplant, yr | ||||

| 0–1 | 1 (0.2) | 13 (3) | 8 (3) | 21 (4) |

| 2–10 | 71 (15) | 158 (32) | 113 (39) | 208 (39) |

| 11–19 | 411 (85) | 323 (65) | 172 (58) | 311 (57) |

| Cause of ESKD | ||||

| CAKUT/VUR | 199 (41) | 220 (45) | 118 (40) | 230 (43) |

| GN | 194 (40) | 151 (31) | 87 (30) | 154 (29) |

| Other | 90 (19) | 123 (24) | 97 (30) | 152 (28) |

| Living donor | 127 (27) | 239 (49) | 198 (68) | 367 (68) |

| Duration of prior dialysis in yr, median (IQR) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 0.7 (0.2–1.4) | 0.8 (0.2–1.9) | 0.7 (0–1.4) |

| HLA mismatch | ||||

| 0–2 | 42 (17) | 84 (18) | 34 (12) | 54 (11) |

| 3–4 | 192 (77) | 346 (73) | 210 (76) | 352 (71) |

| 5–6 | 17 (6) | 41 (9) | 33 (12) | 93 (18) |

| Immunosuppression | ||||

| Aza/Pred | 232 (76) | 26 (05) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| Cyc/Aza/Pred | 3 (1) | 370 (77) | 33 (12) | 2 (0.3) |

| Cyc/MMF/Pred | 0 (0) | 8 (2) | 164 (58) | 70 (13) |

| Tacro/MMF/Pred | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 57 (20) | 425 (82) |

| Other | 73 (23) | 79 (16) | 27 (10) | 25 (05) |

| Induction therapy | ||||

| IL-2 receptor antibody | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 104 (35) | 442 (82) |

| Other | 87 (18) | 124 (25) | 38 (13) | 29 (5) |

| None/missing | 396 (82) | 370 (75) | 151 (52) | 69 (13) |

Number of missing data: immunosuppression, n=215; HLA mismatch, n=312; donor source, n=5; disease, n=5; race, n=12; and induction therapy, n=986. CAKUT, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract; VUR, vesicoureteral reflux; IQR, interquartile range; Aza, azathioprine; Pred, prednisone; Cyc, cyclosporine; MMF, mycophenolate; Tacro, tacrolimus.

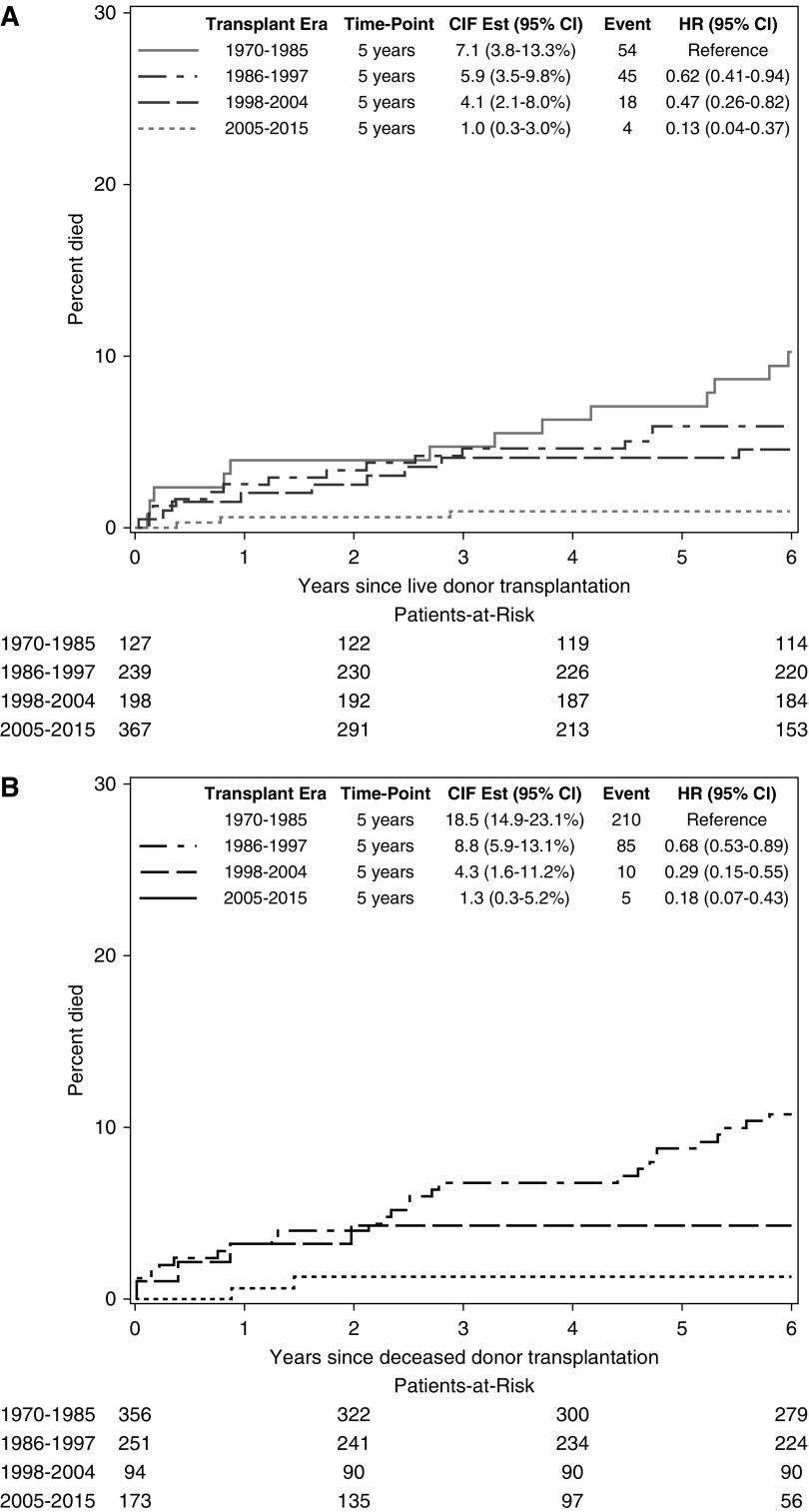

All-Cause Mortality

During the study period, there were 431 deaths, 183 (42%) of which occurred with transplant function and 248 (58%) of which occurred on dialysis after transplant failure. The median time to death was 10 years (IQR, 4–20 years) and the median age at death was 24 years (IQR, 18–35 years). We considered the possibility that changes in survival over time differed by donor source by stratifying on donor source. For living donor recipients, survival improved over time, with 5-year survival rising from 93% (95% CI, 87% to 96%) among those first transplanted in 1970–1985 to 99% (95% CI, 97% to 100%) among those first transplanted in 2005–2015. Deceased donor recipients had poorer survival than living donor recipients, but 5-year survival also improved over time, rising from 81% (95% CI, 77% to 85%) among those first transplanted in 1970–1985 to 99% (95% CI, 95% to 100%) among those first transplanted in 2005–2015. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Improvement with more recent transplant eras for all-cause mortality after kidney transplantation during childhood and adolescence, stratified by donor source. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CIF Est, cumulative incidence function; HR, hazard ratio.

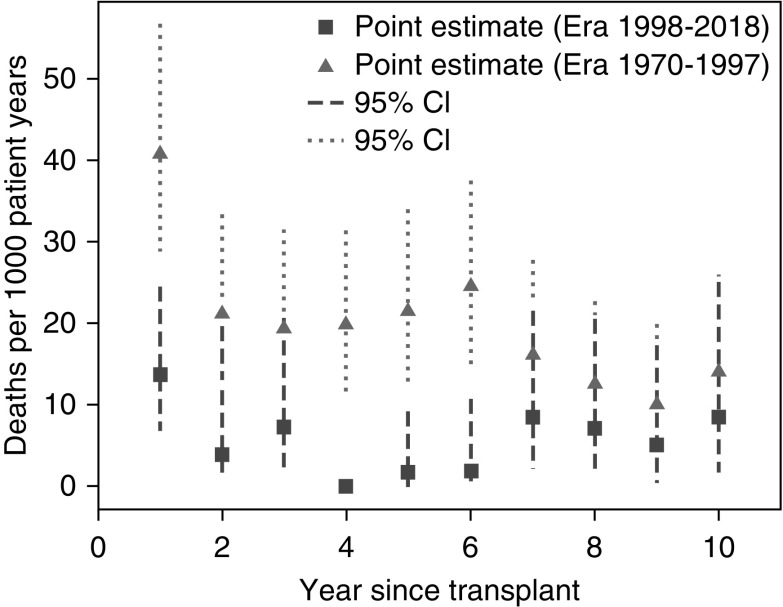

The risk of mortality was highest in the first year post-first-transplant throughout the study period. The absolute risk was markedly lower among those first transplanted from 1998 to 2015, compared with those first transplanted in 1970–1997, with most of the improvement apparent in the first 6 years post-transplantation (Figure 2). The crude risk of death in the first year postfirst-transplant fell from 41/1000 patient-years (1970–1997) to 13/1000 patient-years (1998–2015). Mortality rates were substantially lower in years 2–10 postfirst-transplant than in the first postfirst-transplant year; mortality rates in this interval also dropped from 18/1000 patient-years in 1970–1997 to 5/1000 patient-years in 1998–2015. Decreases in cardiovascular, infectious, and other causes of death (except cancer) all contributed to these improvements (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Mortality rates are highest in the first year post first transplant, but are improved in the more recent transplant era.

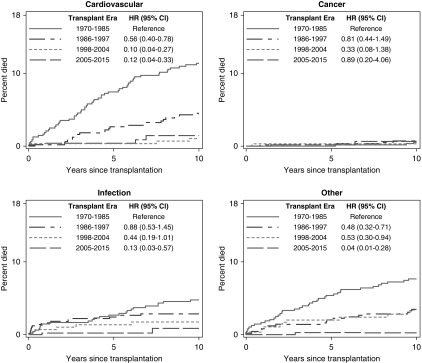

Figure 3.

Cause-specific mortality after kidney transplantation has improved in more recent transplant eras, especially for cardiovascular- and infection-related mortality.

Multivariable modeling quantified the magnitude of the decrease in mortality risk over time. Univariable associations with all-cause mortality are displayed in Supplemental Table 1. After adjusting for transplant status, age at transplant, sex, race/ethnicity, cause of ESKD, donor source, and HLA matching, those transplanted in 2005–2015 had a 72% lower chance of dying compared with those transplanted in 1970–1985 (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.28; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.69) (Table 2). Being on dialysis after a failed transplant was associated with a three-fold increased risk of death (aHR, 2.9; 95% CI, 2.3 to 3.8). Full results of the multivariable model are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Mortality after transplantation, stratified by transplant era

| Era First Transplanted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970–1985 | 1986–1997 | 1998–2004 | 2005–2015 | |

| Number transplanted | 483 | 494 | 293 | 540 |

| Number died (%) | 264 (55%) | 130 (36%) | 28 (10%) | 9 (2%) |

| Absolute mortality rate per 1000 patient-years | 23.0 | 13.2 | 7.2 | 3.3 |

| Adjusted hazard ratio for all-cause mortality (95% CI)a | 1.0 | 0.84 (0.64 to 1.32) | 0.49 (0.32 to 0.79) | 0.28 (0.18 to 0.69) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio for cardiovascular mortality (95% CI)b | 1.0 | 0.63 (0.46 to 0.92) | 0.14 (0.05 to 0.39) | 0.25 (0.08 to 0.68) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio for infectious mortality (95% CI)c | 1.0 | 0.91 (0.53 to 1.55) | 0.49 (0.21 to 0.71) | 0.16 (0.04 to 0.71) |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Adjusted for graft loss, age of transplant, cause of ESKD, donor source, human leukocyte antigen mismatch, sex, and race.

Adjusted for donor source and graft loss.

Adjusted for donor source, graft loss, and age at transplant.

Table 3.

Association between transplant era and mortality, when adjusted for confounders

| Variable | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Transplant era | ||

| 1970–1985 | 1 | 0.21 |

| 1986–1997 | 0.84 (0.64 to 1.32) | 0.002 |

| 1998–2004 | 0.49 (0.32 to 0.79) | 0.002 |

| 2005–2015 | 0.28 (0.18 to 0.69) | |

| Failed graft/on dialysis (versus functioning graft) | 2.9 (2.3 to 3.8) | <0.001 |

| Age at first transplant | ||

| 0–1 yr | 2.8 (1.2 to 5.4) | 0.001 |

| 2–11 yr | 1.0 | 0.004 |

| 12–19 yr | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.8) | |

| Cause of ESKD | ||

| CAKUT | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| GN | 1.1 (0.5 to 1.5) | 0.46 |

| Other | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.3) | <0.001 |

| Deceased donor | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.8) | 0.02 |

| HLA mismatcha | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 0.07 |

| Female sex | 1.1 (0.66 to 1.4) | 0.36 |

| Nonwhite race | 0.87 (0.63 to 3.0) | 0.55 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CAKUT, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract.

Per mismatch.

Cause-Specific Mortality

Of the 431 deaths, 174 (40%) were from cardiovascular causes, 74 (17%) from infection, 50 (12%) from cancer, and 133 (31%) from other causes. The most common causes of cardiovascular death were cardiac arrest of uncertain cause, myocardial infarction, and stroke. The most common causes of cancer death were post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease and cancers of the digestive tract. The most common other cause of death was withdrawal of therapy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Time to death, by cause

| Cause of Death | n (%) | Time to Death in Years,a Median (IQR) | Age at Death in Years, Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All cause | 431 | 10 (4–20) | 24 (18–35) |

| Cardiovascular | 174 (40) | 10 (4–21) | 25 (18–36) |

| Cardiac arrest | 51 (12) | 6 (0–13) | 27 (21–34) |

| Myocardial infarction | 31 (8) | 12 (23–27) | 39 (26–43) |

| Stroke | 26 (6) | 5 (2–15) | 17 (15–25) |

| Malignancy | 50 (12) | 19 (11–26) | 33 (24–43) |

| Gastrointestinal | 10 (2) | 24 (18–30) | 40 (34–36) |

| PTLD | 10 (2) | 10 (2–12) | 19 (13–26) |

| Infection | 74 (17) | 6 (1–13) | 21 (15–29) |

| Other | 133 (31) | 10 (4–20) | 23 (18–33) |

| Withdrawal of treatment | 36 (8) | 16 (9–24) | 23 (16–30) |

IQR, interquartile range; PTLD, post transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Time from first kidney transplant.

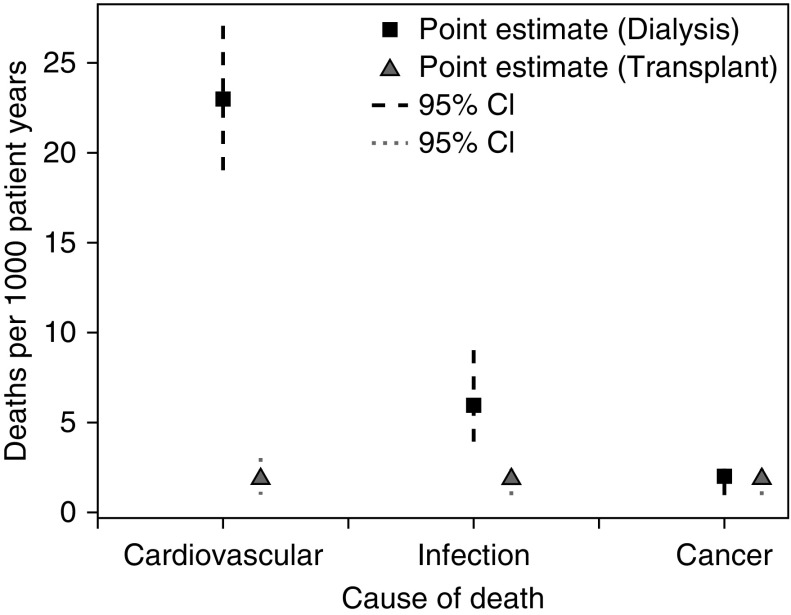

The relative contribution of each cause of death varied depending on transplant status (functioning versus failed, on dialysis) (Figure 4). The crude incidence of death from cardiovascular causes was ten times higher during dialysis (23 deaths/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 19 to 27 deaths/1000 patient-years) than during time with a functioning transplant (2 deaths/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 1 to 3 patient-years). Infection-related deaths were also more common during dialysis (crude incidence during dialysis: 6 deaths/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 4 to 9 deaths/1000 patient-years; crude incidence during transplant function: 2 deaths/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 1 to 2 deaths/1000 patient-years). The exception was the first year after the first transplant, where infection was the most common cause of death (crude incidence: 11 deaths/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 5 to 15 deaths/1000 patient-years). Cancer deaths occurred just as often during transplant function (crude incidence: 2 deaths/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 1 to 2 deaths/1000 patient-years) or dialysis (crude incidence: 2 deaths/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 1 to 2 deaths/1000 patient-years).

Figure 4.

Cardiovascular- and infection-related deaths are more common during dialysis after a failed transplant than during transplant function for childhood and adolescent recipients of a kidney transplant.

Cardiovascular and infectious deaths both decreased in more recent transplant eras, but cancer deaths remained unchanged (Figure 3). The 5-year mortality from cardiovascular causes fell from 8% (95% CI, 5% to 10%) for those transplanted in 1970–1985 to 0.4% (95% CI, 0.1% to 2%; P<0.001) for the 2005–2015 cohort. Infection-related 5-year mortality fell from 3% (95% CI, 2% to 5%) to 0.2% (0.0% to 1%; P=0.007) over the same time span.

After adjusting for confounders, cardiovascular-related (aHR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.08 to 0.68) and infection-related (aHR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.70) mortality rates were significantly lower in the more recent era, compared with those transplanted from 1970 to 1985 (Table 2). As well as era, significant correlates of cardiovascular- and infection-related mortality included deceased donor status, failed transplant (failed versus functioning), and very young or adolescent age at transplantation. (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

In this long-term cohort of children and adolescents who received a kidney transplant and were followed for a median of 13.4 years, the risk of death was 72% lower in the recent era compared with the most remote era. The 5-year survival rate increased from 81% to 93% (depending on donor source) for patients first transplanted in 1970–1985 (azathioprine and prednisone) to 99% for the 2005–2015 (tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone) cohort. In earlier eras, deceased donor recipients had far worse outcomes than living donor recipients; with time this discrepancy has narrowed, but still remains. Overall survival benefits were driven by improvements in cardiovascular- and infection-related mortality, which fell to <1% for each at 5 years after the first transplant in more recent cohorts. The greatest reduction in the risk of overall death occurred within the first 6 years after transplantation. Despite these advances, losing a transplant, deceased donor source and infancy at the time of transplant remain risk factors for death. Among those who died, the median time to death was 10 years after transplantation, with a median age of death of only 24 years.

Australia and New Zealand have similar or better survival rates after pediatric kidney transplantation compared with the rest of the developed world. Five-year survival after first kidney transplant in the most recent era (2005–2015) was 99%, which compares favorably to the values of 94%–97% reported in international studies (7,19–23). Over time, there has been an improvement in patient survival, with 10-year survival improving from 75% (era 1970–1985) to 97% (era 2005–2015). Other long-term reports show similar improvements in 10-year survival, with the United States reporting 75%–78% survival for patients first transplanted in the 1980s, improving to 90%–96% after the turn of the millennium (6–8).

Deceased donor transplant recipients experienced greater improvements in survival across transplant eras than living donor recipients. Marked differences in survival in the most distant era (5-year survival 81% for deceased donor recipients versus 93% for living donor recipients) narrowed to nearly identical survival (5-year survival for both close to 99%) in the most recent era. Deceased donor recipients across all eras spent longer on dialysis before their first transplant than their living donor counterparts. Improvements in dialysis care over time may contribute to the narrowing of the survival gap for overall and cardiovascular-related mortality postfirst-transplant for deceased and living donor recipients.

The first year after the first transplant was the highest risk time for death, at around double the incidence per patient-year compared with each subsequent year. Infection was the most common cause of death in the first year after transplant. The absolute risk of death in the first year fell drastically, from 41 to 13 deaths/1000 patient-years from 1970 to 1997 compared with 1998–2015. This study reveals large gains in survival in the modern immunosuppressive era, with most of those gains appearing to occur in the first 6 years after the first transplant, driven by decreases in cardiovascular- and infection-related deaths.

Cardiovascular-related (40%), infection-related (17%), and cancer (12%) were the most common causes of death, similar to other reports (7,24,25). This study examined the association between era and cause-specific mortality, and advances current knowledge by demonstrating drastic improvements in cardiovascular and infectious deaths over the transplant eras, contributing to advances in overall survival. A comparison between two transplant cohorts (1970–1985 compared with 2005–2015) revealed a 75% relative reduction of the risk of cardiovascular death and an 84% relative reduction in the risk of infectious death. Cardiovascular mortality within 10 years after a first transplant fell from 11% to 1% (1970–1985 compared with 2005–2015) and 10-year infection-related mortality fell from 5% to <1% over the same time period. Cancer death rates did not change over time, with <1% 10-year mortality for every era.

Immunosuppression data at the time of transplant were unavailable for many prior studies. This study extends current knowledge by using immunosuppression eras to examine patient and transplant survival (Supplemental Figure 1). The use of a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus or cyclosporine) and mycophenolate with prednisone may be associated with improved survival. When compared with 1970–1985 (76% on azathioprine and prednisone), the current era (2005–2015, 82% on tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone) was associated with an 81% lower mortality risk when adjusted for factors such as age at transplant, cause of ESKD, transplant function, and donor source. Many aspects of transplant care have improved since the 1970s, such that it is unlikely that immunosuppression solely accounts for this survival advantage. Improved monitoring for and prophylaxis of infections, more attention to cardiovascular risk factors and wide uptake of clinical practice guidelines are likely to also contribute to the survival gains in more recent eras.

The first year after the first transplant and losing a transplant are higher risk periods for death. Losing a transplant was associated with a three-fold increase in mortality risk, when adjusted for transplant era, age, and cause of ESKD. Cardiovascular death was even more likely (five-fold increase in risk) to occur during dialysis after a failed transplant, after adjusting for era and donor source, similar to the findings of other studies (7,25,26). Similarly, infection-related deaths were more likely to occur during a period of transplant function. Given cancer is more common during transplant function (27), it was surprising that cancer-related deaths occurred at similar rates during transplant function or dialysis, but this may be explained by transplant loss secondary to reduction or withdrawal of immunosuppression as part of cancer treatment.

This study has a number of strengths. The long duration of follow-up allowed a more comprehensive evaluation of the risk of mortality over time and the variations associated with transplant era. The incidence of cause-specific mortality was calculated accounting for competing risks of other causes of death. Balanced against these strengths are several potential limitations. The weaknesses inherent to all retrospective registry studies apply, including potential detection and confounding biases. The reporting of cause of death in ANZDATA was reliant on the treating team and was not crossverified with the National Death Index. Prior comparison of the cause of death recorded in ANZDATA with the National Death Index has revealed good correlation for the timing of death, and fair agreement in the coding of cause of death, with the best agreement found for cancer-related deaths (28). There was also limited granularity of data collection and no information pertaining to transplant management protocols, changes in immunosuppression after transplant, or treatment adherence. The relationship between era and mortality may potentially have been modified by patient age, but numbers were too small to explore this. It is unclear if the findings of decreased cardiovascular- and infection-related mortality are generalizable to other countries, particularly those with differing health care systems.

In conclusion, patient survival has improved dramatically since the founding of the pediatric kidney transplantation program in Australia and New Zealand, resulting in comparable survival to the rest of the developed world. Decreases in cardiovascular- and infection-related mortality have accounted in large part for these improvements. Despite this, losing a kidney transplant, very young age at the time of transplant, and deceased donor source remain important risk factors for mortality. Future research directions include collaborative registry studies to examine changes in cause-specific mortality from a global perspective.

Disclosures

Dr. Johnson reports receiving consultancy fees, research grants, speaker’s honoraria, and travel sponsorships for Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care; consultancy fees from AstraZeneca and AWAK; and travel sponsorship from Amgen, all outside of the submitted work. Ms. Blazek, Dr. Craig, Dr. Foster, Dr. Francis, Dr. Melk, and Dr. Wong have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Johnson is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship. Dr. Wong is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Armando Teixeira-Pinto for statistical assistance and the substantial contributions of the entire Australia and New Zealand nephrology community (physicians, surgeons, database managers, nurses, nephrology operators, and patients) in providing information for, and maintaining the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry database.

The data reported here have been supplied by the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the Authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Secular Trends in Survival Outcomes of Kidney Transplantation for Children: Is the Future Bright Enough?” on pages 308–310.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07070619/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Univariate analysis of predictors of all-cause mortality after kidney transplantation during childhood and adolescence.

Supplemental Table 2. Factors associated with cardiovascular mortality after kidney transplantation during childhood and adolescence.

Supplemental Table 3. Factors associated with infection-related mortality after kidney transplantation during childhood and adolescence.

Supplemental Figure 1. Baseline immunosuppression over time.

Supplemental Figure 2. Spline demonstrating relationship between age at transplant and mortality.

Supplemental Figure 3. Study flow.

References

- 1.Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ: Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol 27: 363–373, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francis A, Didsbury MS, van Zwieten A, Chen K, James LJ, Kim S, Howard K, Williams G, Bahat Treidel O, McTaggart S, Walker A, Mackie F, Kara T, Nassar N, Teixeira-Pinto A, Tong A, Johnson D, Craig JC, Wong G: Quality of life of children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study. Arch Dis Child 104: 134–140, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Icard P, Hooper SR, Gipson DS, Ferris ME: Cognitive improvement in children with CKD after transplant. Pediatr Transplant 14: 887–890, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samuel SM, Tonelli MA, Foster BJ, Alexander RT, Nettel-Aguirre A, Soo A, Hemmelgarn BR; Pediatric Renal Outcomes Canada Group : Survival in pediatric dialysis and transplant patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1094–1099, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmberg C, Jalanko H: Long-term effects of paediatric kidney transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 301–311, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinnakotla S, Verghese P, Chavers B, Rheault MN, Kirchner V, Dunn T, Kashtan C, Nevins T, Mauer M, Pruett T; MNUM Pediatric Transplant Program : Outcomes and risk factors for graft loss: Lessons learned from 1,056 pediatric kidney transplants at the University of Minnesota. J Am Coll Surg 224: 473–486, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laskin BL, Mitsnefes MM, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Foster BJ: The mortality risk with graft function has decreased among children receiving a first kidney transplant in the United States. Kidney Int 87: 575–583, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Arendonk KJ, Boyarsky BJ, Orandi BJ, James NT, Smith JM, Colombani PM, Segev DL: National trends over 25 years in pediatric kidney transplant outcomes. Pediatrics 133: 594–601, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster BJ, Mitsnefes MM, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Laskin BL: Changes in excess mortality from end stage renal disease in the United States from 1995 to 2013. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 91–99, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative : The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61: 344–349, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibshirani R: The lasso method for variable selection in the Cox model. Stat Med 16: 385–395, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor J, Tibshirani R: Post-selection inference for ℓ1-Penalized likelihood models. Can J Stat 46: 41–61, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sapir-Pichhadze R, Pintilie M, Tinckam KJ, Laupacis A, Logan AG, Beyene J, Kim SJ: Survival analysis in the presence of competing risks: The example of waitlisted kidney transplant candidates. Am J Transplant 16: 1958–1966, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chavers BM, Rheault MN, Matas AJ, Jackson SC, Cook ME, Nevins TE, Najarian JS, Chinnakotla S: Improved outcomes of kidney transplantation in infants (age < 2 years): A single-center experience. Transplantation 102: 284–290, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andreoni KA, Forbes R, Andreoni RM, Phillips G, Stewart H, Ferris M: Age-related kidney transplant outcomes: Health disparities amplified in adolescence. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1524–1532, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones E, Oliphant T, and Peterson P: SciPy: Open source scientific tools for python. 2001. Available at: https://www.scipy.org. Accessed January 1, 2018

- 18.R Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allain-Launay E, Roussey-Kesler G, Ranchin B, Guest G, Maisin A, Novo R, André JL, Cloarec S, Guyot C: Mortality in pediatric renal transplantation: A study of the French pediatric kidney database. Pediatr Transplant 13: 725–730, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amaral S, Sayed BA, Kutner N, Patzer RE: Preemptive kidney transplantation is associated with survival benefits among pediatric patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 90: 1100–1108, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia C, Pestana JM, Martins S, Nogueira P, Barros V, Rohde R, Camargo M, Feltran L, Esmeraldo R, Carvalho R, Schvartsman B, Vaisbich M, Watanabe A, Cunha M, Meneses R, Prates L, Belangero V, Palma L, Carvalho D, Matuk T, Benini V, Laranjo S, Abbud-Filho M, Charpiot IM, Ramalho HJ, Lima E, Penido J, Andrade C, Gesteira M, Tavares M, Penido M, De Souza V, Wagner M: Collaborative Brazilian Pediatric Renal Transplant Registry (CoBrazPed-RTx): A report from 2004 to 2013. Transplant Proc 47: 950–953, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L, Zhang H, Fu Q, Chen L, Sun C, Xiong Y, Shi B, Wang C: Current status of pediatric kidney transplantation in China: Data analysis of Chinese scientific registry of kidney transplantation. Chin Med J (Engl) 127: 506–510, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pérez-Bertólez S, Barrero R, Fijo J, Alonso V, Ojha D, Fernández-Hurtado MA, Martínez J, León E, García-Merino F: Outcomes of pediatric living donor kidney transplantation: A single-center experience. Pediatr Transplant 21: e12881, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitsnefes MM: Cardiovascular disease in children with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 578–585, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster BJ, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Platt RW, Hanley JA: Change in mortality risk over time in young kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 11: 2432–2442, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kramer A, Stel VS, Tizard J, Verrina E, Rönnholm K, Pálsson R, Maxwell H, Jager KJ: Characteristics and survival of young adults who started renal replacement therapy during childhood. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 926–933, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanik EL, Clarke CA, Snyder JJ, Pfeiffer RM, Engels EA: Variation in cancer incidence among patients with ESRD during kidney function and nonfunction intervals. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1495–1504, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sypek MP, Dansie KB, Clayton P, Webster AC, Mcdonald S: Comparison of cause of death between Australian and New Zealand dialysis and transplant registry and the Australian National Death Index. Nephrology (Carlton) 24: 322–329, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.