Abstract

Background

Metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma (sRCC) is an aggressive variant of RCC with generally poor prognosis. Treatment with vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors or chemotherapy generates only short-lived responses. Recent research has suggested a role for combination checkpoint inhibition as first line treatment for metastatic sRCC. This therapy consists of induction with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 inhibitor, ipilimumab, administered with programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor, nivolumab. After completion of four cycles of combination therapy, single-agent maintenance nivolumab is recommended until progression. Patients who progress on maintenance nivolumab are switched to alternate therapy. Herein, we present a case of a patient with RCC who progressed on maintenance nivolumab who, on retreatment with ipilimumab, demonstrated a significant response In addition, we summarize important findings to support the role of salvage ipilimumab in patients with sRCC.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old man presented with flank pain and hematuria, the work up of which noted a left kidney mass for which he underwent nephrectomy and was diagnosed with localized sRCC with 60% sarcomatoid differentiation. Within 3 months of nephrectomy, he presented with recurrent flank pain and was diagnosed with recurrence of disease. He was treated with ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg for four doses and demonstrated a partial response. He was then transitioned to single agent nivolumab maintenance. After 3 months on maintenance therapy, he was noted to have progression of disease. Given prior response to immune check point combination, it was decided to rechallenge the patient with 1 mg/kg ipilimumab. After two doses of ipilimumab and nivolumab combination therapy, the patient was noted to have a partial response. He maintained a response for an additional 9 months and treatment was eventually discontinued due to grade 3 toxicity and progression.

Conclusions

This case report demonstrates the utility of retreatment with ipilimumab as a salvage option for patients progressing on maintenance PD-1 inhibitors in metastatic RCC. Further studies are needed to identify predictors of response and toxicity to this approach, as well as the optimal scheduling of ipilimumab with maintenance nivolumab.

Keywords: case reports

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for approximately 65 000 new cancer cases and 15 000 deaths annually in the USA.1 Sarcomatoid RCC (sRCC) represent a relatively rare subset of cancers of kidney origin with aggressive growth characteristics and pathological similarities to spindle cell sarcomas, including dense cellularity and cellular atypia.2 Approximately 1%–5% of all diagnosed RCCs contain a component of sRCC, which usually becomes the predominant component of tumor during evolution of tumor development.3 Patients with sRCC typically present with metastatic disease at diagnosis.2

Independent of stage at diagnosis, patients with sRCC have a poorer prognosis than patients with pure clear cell RCC, and current treatment approaches have not yielded significant benefit.3 As with other forms of RCC, chemotherapy regimens such as gemcitabine and doxorubicin are of limited therapeutic utility, with median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of 3.5 months and 8.8 months, respectively.4 Initial studies involving vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors have not demonstrated improvement in survival3; however, a recent phase II study of sunitinib with gemcitabine demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 26% with a stable disease rate of 38%.5

Several reports have suggested that sRCC tumor cells express programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) more frequently when compared with clear cell tumors.6 7 This likely reflects a more inflamed milieu within sRCC, since PD-L1 upregulation is known to result from the presence of type II interferons within the tumor microenvironment.8 Retrospective and prospective data also supports the activity of checkpoint inhibitors in sRCC.9

An updated analysis of a phase II study of atezolizumab and bevacizumab in patients with clear cell sRCC demonstrated an ORR of 53%.10 In the CheckMate 214 study, an exploratory analysis of a sRCC cohort also demonstrated response to immunotherapy with an ORR of 56.7% with nivolumab plus ipilimumab (95% CI 43.2% to 69.4%) versus 19.2% (95% CI 9.6% to 32.5%) with sunitinib (p<0.0001).11

While the data from immunotherapy in sRCC have been encouraging, many patients do not demonstrate a significant response, and responsive patients eventually develop progression. In this case report, we describe a patient with sRCC who had an initial response with ipilimumab and nivolumab, rapid progression on maintenance nivolumab, and subsequent response with rechallenge of ipilimumab. This report also provides a review of relevant literature on the efficacy of ipilimumab in sRCC.

Case report

A 46-year-old man presenting with hematuria underwent a diagnostic CT urogram revealing a 14.2×10.6×9.3 cm left renal mass with proximal renal vein thrombosis and retroperitoneal adenopathy. Chest imaging at the time identified small pulmonary nodules which were too small for characterization. The patient underwent a left radical nephrectomy with pathological evaluation identifying a T3N1M0 (14.2×10.6×9.3 cm) renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation (40%).

Two months after nephrectomy, surveillance scans identified extensive presumed metastases in the abdomen, pelvis and both lungs, with the largest mass consisting of a left renal fossa mass measuring 8.9×3.2 cm. Biopsy of a presumed metastatic lesion in left anterior abdominal wall was consistent with poorly differentiated carcinoma with 50%–60% rhabdoid and sarcomatoid differentiation that stained for Pax-8, suggesting metastatic renal cell carcinoma. The patient was considered poor risk as assessed by IInternational Metastatic RCC Database Consortium.

After 3 months on maintenance nivolumab therapy, the size of the patient’s retroperitoneal and abdominal wall metastases approximately doubled as assessed by CT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis (figure 1). In consideration of possible subsequent treatments, we noted the patient’s prior response to ipilimumab, previous tolerance of combined immunotherapy, good performance status, and sRCC histology which has historically poor outcomes with VEGF inhibitors. Given this information, it was decided to retreat the patient with ipilimumab 1 mg/kg along with continued nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks. A partial response was demonstrated on imaging after two additional doses of ipilimumab plus nivolumab, with all but one lesion shrinking by more than 50 per cent (see figure 2, table 1). The patient remained on combined immune checkpoint blockade therapy for a total of 9 months with stable disease before treatment was discontinued due to grade 3 fatigue, arthralgias and progression of disease in the right ventricle alone.

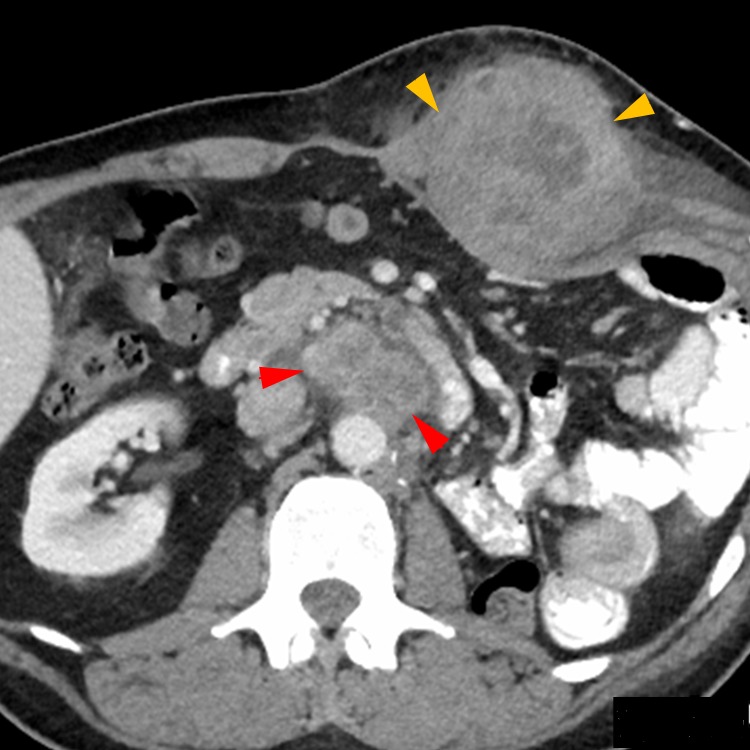

Figure 1.

Progression of disease while on nivolumab maintenance therapy only Follow-up CT with contrast after 4 months of nivolumab maintenance therapy only demonstrating marked progression of disease with enlarging left retroperitoneal (red arrows) and abdominal wall (orange arrows) metastases.

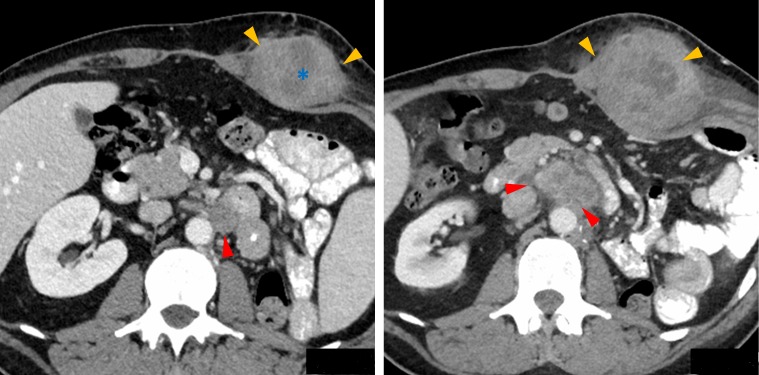

Figure 2.

Partial Response to therapy after re-challenge of ipilimumab + nivolumab Follow-up CT with contrast after 5 months of nivolumab and re-introduction of ipilimumab demonstrating partial response to therapy with substantially smaller left retroperitoneal (red arrows) and abdominal wall (orange arrows) metastases since previous CT (figure 1). Note the increased low-density central necrosis (*) in the abdominal wall metastasis indicating treatment response.

Table 1.

Target lesion changes with immunotherapy

| Target lesion | Basal CT in cm | After four cycles IPI+nivo | After four cycles of maintenance nivo | After two doses of IPI and nivo (reintroduction) |

| Pre aortic LN | 8.9×3.2 cm | 3.1×2.6 cm | 4.2×2.4 cm | 2.1×2.5 cm |

| Rectus abdominis | 5.4×3.6 cm | 4.2×3.7 cm | 8.2×7.6 cm | 5.5×7.3 cm (central necrosis present) |

IPI, ipilumumab; LN, lymph node.

Discussion

sRCC typically portends a poor prognosis as demonstrated by a review of clinical data presented in table 2. This may, in part be due to high PD-L1 expression on sRCC cells which has been independently associated with poor outcomes in renal cell cancer.12 In prior studies, BAP1 loss was associated with high tumor grade, sarcomatoid differentiation and poor outcomes, as noted in our patient.13 14 In RCC, BAP-1 mutations have been identified in approximately 15% of patients with RCC and was noted to enhance mesenchymal–epithelial transition, which could be one reason why our patient presented with metastatic disease within 3 months of diagnosis.15 16 The Checkmate 214 trial examined the safety and efficacy of anti-PD-1 with anti-CTLA4. A significant improvement in OS was noted in all RCC patients after treatment with ipilimumab and nivolumab compared with sunitinib (median not reached vs 26 months, HR 0.63).17 Among patients with sarcomatoid differentiation, the rate of complete response (CR) was 18.3% with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 0% with sunitinib with superior OS in the immunotherapy arm irrespective of PD-L1 expression. However, significant toxicity was noted with ipilimumab and nivolumab, with 46% of patients experiencing grade 3–4 toxicity. Even though the results with immunotherapy are promising for sRCC compared with historical data, a majority of patients do not respond and progression is inevitable, thus development of novel treatment strategies is urgently needed.

Table 2.

Summary of studies for sarcomatoid renal cell cancer

| Author | N | Treatment | Objective response (%) | PFS (months) | OS (months) |

| Sella et al 26 | 8 | Cyclophosphamide+vincristine + doxorubicin+dacarbazine | 25 | NA | 13 |

| Mian et al 27 | 67 | Interferon based therapy | 21 | NA | 19 |

| Escudier et al 28 | 23 | Doxorubicin+ifosfamide | 0 | 2.2 | 3.3 |

| Haas et al 4 | 38 | Gemcitabine+doxorubicin | 15.8 | 3.5 | 8.8 |

| Golshayan et al 29 | 26 | Sunitinib | 19 | 5.3 | 11.8 |

| Kyriakopoulous et al 30 | 230 | VEGF inhibitors | 21 | 4.5 | 10.4 |

| Mckay et al 10 | 16 | Atezolizumab+bevacizumab | 44 | NA | NA |

| McDermott et al 11 | 60 | Ipilimumab+nivolumab | 56.7 | 8.4 | 31.2 |

N, number of patients in the study; NA, not reported; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and PD-1 are inhibitory receptors on T cells that limit T cell activation and function. These proteins act through distinct mechanisms to block T cell activation. CTLA-4 is expressed after initial T cell activation and acts to sequester ligands B7-1 and B7-2 (CD80, CD86) that are required for signaling through the costimulatory receptor CD28.18 Blockade of CTLA-4 results in enhanced activation of primary T cells and clonal expansion of nascent CD8+T cell clones.18 Anti-CTLA4 antibodies with heavy chains capable of fixing complement may also eliminate inhibitory T cell subsets, such as regulatory foxP3+CD4+T cells, from the tumor microenvironment.19 In contrast, therapies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis act on CD8+T cells that have undergone initial activation but acquired functional attenuation due to chronic exposure to antigen through a process termed T cell exhaustion.20 Thus, although the two therapeutic strategies both fall under the purview of immune checkpoint inhibition, they act through distinct mechanisms to selectively potentiate activation of naïve (anti-CTLA-4) or exhausted (anti-PD-1/PD-L1) CD8+T cells. A possible explanation for the secondary responsiveness to ipilimumab observed in this patient is that progression of RCC results in development of neoantigens that can be recognized by naïve T cells in a manner facilitated by anti-CTLA-4.

The use of ipilimumab is limited to four doses when given in combination with nivolumab given concerns for significant autoimmune toxicities.21 Checkmate 016 evaluated the role of intravenous nivolumab 3 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 1 mg/kg (N3I1), nivolumab 1 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg (N1I3) or nivolumab 3 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg (N3I3) every 3 weeks for four doses followed by nivolumab monotherapy 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks until progression or toxicity in RCC patients.22 The incidence of grade 3/4 AE was significant with N1I3 and N3I3 dosing and hence the regimen used in our patients is FDA approved.

The use of ipilimumab with nivolumab a salvage therapy has been reported in patients with melanoma, with approximately 50% of patients demonstrating disease control.23 Unfortunately, 68% of these patients experienced clinically significant toxicity resulting in 40% of patients discontinuing therapy.

Salvage ipilimumab and nivolumab has been found to be safe and effective in immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) refractory melanoma and ccRCC patients.23–25 The TITAN trial that was discussed at European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) 2019 evaluated the role of salvage ipilimumab in combination with nivolumab for patients with stable disease/progressive disease on single agent nivolumab and noted a 10 per cent salvage rate with ipilimumab. This study is different from our approach as our patient had received prior ipilimumab and nivolumab, salvage ipilimumab was added when the patient had progressed on single agent nivolumab. In the TITAN trial, none of the patients had gotten upfront ipilimumab. In the TITAN trial, the CR rate was also significantly lower than checkmate 214 and with immature OS data, suggesting that upfront ipilimumab may be warranted for eligible patients. Another retrospective study evaluated the use of ipilimumab and nivolumab as salvage therapy in patients with clear cell mRCC refractory to immunotherapy therapy combinations and a 40% partial response rate was noted.24 It would also be worth further exploring the role of Ipilimumab with a dose of 3 mg/kg as salvage therapy if toxicity permits. Further studies are needed to determine which sRCC patients are appropriate for salvage ipilimumab with progression on nivolumab monotherapy. It is also unknown as to whether BAP1 loss in RCC defines a cohort that is immune responsive. Further, the optimal frequency and dose of ipilimumab treatment needs to be established.

Here, we report the first case of reinvigoration of responses in an sRCC patient undergoing nivolumab maintenance monotherapy with the addition of ipilimumab. This suggests that ipilimumab could be used to salvage maintenance nivolumab in sRCC and indicates that enhancing activation of naïve T cell subsets could be an important mechanism to engage effective immune responses in sRCC. Further studies are needed to evaluate this approach.

Footnotes

Contributors: GG, LS, DK collected data and wrote the manuscript. MR appraised and edited the manuscript. PT provided images for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Zincke H, et al. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: an examination of underlying histologic subtype and an analysis of associations with patient outcome. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:435–41. 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shuch B, Bratslavsky G, Linehan WM, et al. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: a comprehensive review of the biology and current treatment strategies. Oncologist 2012;17:46–54. 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haas NB, Lin X, Manola J, et al. A phase II trial of doxorubicin and gemcitabine in renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid features: ECoG 8802. Med Oncol 2012;29:761–7. 10.1007/s12032-011-9829-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McKay RR, Choueiri TK, Werner L, et al. A phase II trial of sunitinib and gemcitabine in sarcomatoid and/or poor-risk patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JCO 2015;33:408 10.1200/jco.2015.33.7_suppl.408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raychaudhuri R, Riese MJ, Bylow K, et al. Immune check point inhibition in Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: a new treatment paradigm. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2017;15:e897–901. 10.1016/j.clgc.2017.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Joseph RW, Millis SZ, Carballido EM, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in renal cell carcinoma with Sarcomatoid differentiation. Cancer Immunol Res 2015;3:1303–7. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, et al. Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression. Cell Rep 2017;19:1189–201. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ross JA, McCormick BZ, Gao J, et al. Outcomes of patients (PTS) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) and sarcomatoid dedifferentiation (sRCC) after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI): a single-institution retrospective study. JCO 2018;36:4583 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McKay RR, McGregor BA, Gray K, et al. Results of a phase II study of atezolizumab and bevacizumab in non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma (nccRCC) and clear cell renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation (sccRCC). JCO 2019;37:548 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.7_suppl.548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDermott DF, Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ, et al. CheckMate 214 post-hoc analyses of nivolumab plus ipilimumab or sunitinib in IMDC intermediate/poor-risk patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid features. JCO 2019;37:4513 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.4513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thompson RH, Kuntz SM, Leibovich BC, et al. Tumor B7-H1 is associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma patients with long-term follow-up. Cancer Res 2006;66:3381–5. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kapur P, Christie A, Raman JD, et al. BAP1 immunohistochemistry predicts outcomes in a multi-institutional cohort with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 2014;191:603–10. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brugarolas J. PBRM1 and BAP1 as novel targets for renal cell carcinoma. Cancer J 2013;19:324–32. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3182a102d1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peña-Llopis S, Vega-Rubín-de-Celis S, Liao A, et al. BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet 2012;44:751–9. 10.1038/ng.2323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kapur P, Peña-Llopis S, Christie A, et al. Effects on survival of BAP1 and PBRM1 mutations in sporadic clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis with independent validation. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:159–67. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70584-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1277–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1069–86. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simpson TR, Li F, Montalvo-Ortiz W, et al. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J Exp Med 2013;210:1695–710. 10.1084/jem.20130579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Virgin HW, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Redefining chronic viral infection. Cell 2009;138:30–50. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fecher LA, Agarwala SS, Hodi FS, et al. Ipilimumab and its toxicities: a multidisciplinary approach. Oncologist 2013;18:733–43. 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hammers HJ, Plimack ER, Infante JR, et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the CheckMate 016 study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3851–8. 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gaughan EM, Petroni GR, Grosh WW, et al. Salvage combination ipilimumab and nivolumab after failure of prior checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with advanced melanoma. JCO 2017;35:e21009 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e21009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gul A, Shah NJ, Mantia C, et al. Ipilimumab plus nivolumab (Ipi/Nivo) as salvage therapy in patients with immunotherapy (IO)-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). JCO 2019;37:669 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.7_suppl.669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zimmer L, Apuri S, Eroglu Z, et al. Ipilimumab alone or in combination with nivolumab after progression on anti-PD-1 therapy in advanced melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2017;75:47–55. 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sella A, Logothetis CJ, Ro JY, et al. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma. A treatable entity. Cancer 1987;60:1313–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mian BM, Bhadkamkar N, Slaton JW, et al. Prognostic factors and survival of patients with sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 2002;167:65–70. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65384-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Escudier B, Droz JP, Rolland F, et al. Doxorubicin and ifosfamide in patients with metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: a phase II study of the genitourinary group of the French Federation of cancer centers. J Urol 2002;168:959–61. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64551-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Golshayan AR, George S, Heng DY, et al. Metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:235–41. 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kyriakopoulos CE, Chittoria N, Choueiri TK, et al. Outcome of patients with metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: results from the International metastatic renal cell carcinoma database Consortium. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2015;13:e79–85. 10.1016/j.clgc.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]