Abstract

A combination of plasmonic nanoparticles (NPs) with semiconductor photocatalysts, called plasmonic photocatalysts, can be a good candidate for highly efficient photocatalysts using broadband solar light because it can greatly enhance overall photocatalytic efficiency by extending the working wavelength range of light from ultraviolet (UV) to visible. In particular, fixation of plasmonic photocatalysts on a floating porous substrate can have additional advantages for their recycling after water treatment. Here, we report on a floating porous plasmonic photocatalyst based on a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)–TiO2–gold (Au) composite sponge, in which TiO2 and Au NPs are simultaneously immobilized on the surface of interconnected pores in the PDMS sponge. This can be easily fabricated by a simple sugar-template method with TiO2 NPs and in situ reduction of Au NPs by the PDMS without extra chemicals. Its ability to decompose the organic pollutant rhodamine B in water was tested under UV and visible light, respectively. The results showed highly enhanced photocatalytic activity under both UV and visible light compared to the PDMS–TiO2 sponge and the PDMS–Au sponge. Furthermore, its recyclability was also demonstrated for multiple cycles. The simplicity of fabrication and high photocatalytic performance of our PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge can be promising in environmental applications to treat water pollution.

1. Introduction

Semiconductor-based photocatalysts can absorb photons to generate electron–hole pairs that can be used for the oxidation or reduction of materials on a photocatalyst surface.1,2 This property has caused intensive research into photocatalysts for their possible applications in the fields of environmental purification3,4 and sustainable energy such as water splitting.5 Among others, TiO2 has been the most studied material owing to its abundance, low price, nontoxicity, high chemical stability, and high photoactivity.1,6,7 However, one significant obstacle to the real application of TiO2 is its large band gap energy, owing to which it can absorb only ultraviolet (UV) light with wavelengths of less than 400 nm, which is a very minor portion of the solar spectrum.8 This significantly limits the efficiency of TiO2 in applications that use solar light.

There have been many efforts to extend the absorption wavelength range of TiO2-based photocatalysts to visible light, such as hydrogenation to make black TiO2 and the incorporation of metal or nonmetal impurities.3,9−13 However, despite a broadened absorption wavelength range, many of these techniques also suffer from a higher recombination rate of generated electron–hole pairs by an increased number of defect sites inside the TiO2.14

Recently, plasmonic photocatalysis, based on a combination of noble metal nanoparticles (NPs) and TiO2, has been investigated as a new strategy for the development of visible-light-active photocatalysts.14−16 Noble metals such as gold (Au) NPs can strongly absorb visible light by localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), which is a collective oscillation of electrons at the surface. LSPR can induce highly energetic electrons by light absorption, which can be injected into a neighboring TiO2 matrix.16,17 This can greatly enhance the photocatalytic activity in visible light.

Many different methods have been applied to make various types of Au NP-loaded TiO2 systems: the adsorption of preformed Au colloid NPs on TiO2 NPs,18,19 thermal annealing of deposited Au film to make embedded Au NPs inside a TiO2 matrix,20 UV photoreduction21 or chemical reduction of Au precursor on the surface of TiO2 NPs,22 and so on. A NP type of TiO2 system can have a large surface area for catalytic reactions. In addition, a small size is advantageous to reduce the recombination of electron–hole pairs before their migration to the surface. However, in the case of the free suspension of TiO2 NPs for water purification, it is very difficult to re-collect TiO2 NPs for recycling after treatment. On the other hand, a film type of TiO2 system has a limited surface area to encounter materials to be decomposed and a higher recombination rate owing to the greater size, despite being easier to recycle than a NP type of TiO2.

Immobilizing TiO2 NPs on a porous solid substrate is one method to enhance both efficiency and recyclability. In particular, the loading of TiO2 NPs on floating porous substrates has another advantage for water purification utilizing sunlight, which generally shines on the solution from above, when considering a limited light penetration depth underwater.23 Among various floating porous substrates, a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) sponge is a very promising material.24 It is chemically inert and biocompatible. Its hydrophobicity facilitates the absorption of hydrophobic organic molecules from water.25,26 It can be easily fabricated by a simple method using a sugar cube as a template without using any toxic chemicals.27 There have been several promising results from recent studies on the PDMS–TiO2 composite sponge for photocatalytic application.28−30

In addition to the abovementioned advantages, PDMS has another important property that can be advantageous in loading Au NPs on a PDMS surface: PDMS can directly reduce Au-ion precursors to Au NPs without using any chemical reductant owing to the reducing power of the PDMS curing agent itself.31,32 This can be very useful in fabricating PDMS–Au composite materials for plasmonic application.

Here, we report on a floating porous plasmonic photocatalyst based on the PDMS–TiO2–Au composite sponge. Colloidal TiO2 NPs were embedded in the PDMS sponge pore interface, and then Au NPs were directly reduced from the Au precursor at the PDMS sponge pore interface. The high loading density of Au NPs and TiO2 NPs in a small confined space on the pore interface increases the probability of their close contact, which is required for the plasmonic photocatalytic effect. In addition, the high adsorption capacity of porous structures allows target organic molecules to be effectively located near the Au and TiO2 NPs attached to the pore surface.

This type of fabrication is simpler than the loading of presynthesized TiO2–Au hybrid NPs on the PDMS sponge because it can skip extra chemical or photoreduction processes to form Au NPs on the surface of TiO2 NPs in solution by using the PDMS sponge as the template as well as the reducing agent. In this work, for the first time, we demonstrated the enhanced photocatalytic effect of the PDMS–TiO2–Au composite sponge under visible light as well as UV light, compared to the PDMS–TiO2 and the PDMS–Au sponges. Although the fabrication of the PDMS–TiO2–noble metal composite sponge itself has been introduced previously in other papers, it mostly focused on the usage of noble metal NPs as the surface-enhanced Raman scattering probes to identify the kind of chemicals, rather than as the plasmonic photocatalyst to enhance the decomposition of chemicals.30 The high photocatalytic activity of the PDMS–TiO2–Au composite sponge for a large wavelength range from UV to visible light should be very helpful in applications that use broadband solar light.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of a PDMS–TiO2–Au Sponge

A PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge was fabricated following the process shown in Scheme 1 (for details, see the Experimental Methods). In this process, TiO2 NPs are embedded in the PDMS pore interface with a section of the TiO2 surface exposed for direct contact with the solution phase. Owing to the stability of TiO2 NPs, the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge can maintain its photocatalytic activity under multiple reuses, which will be shown in the recyclability test result.

Scheme 1. Fabrication of a PDMS–TiO2–Au Sponge.

Additionally, Au NPs can be directly reduced from the HAuCl4 precursor by the reducing ability of the residual curing agent of PDMS, which can be identified by a color change of the sponge from yellow (the color of HAuCl4 precursor) to violet. The reducing ability of PDMS was reported in previous studies.31,32 Whereas no additional chemical reducing agent was used, the residual Si–H groups of the PDMS matrix themselves can act as agents to reduce Au NPs from the HAuCl4 precursor. The reducing ability of PDMS can be maintained after being cured to solid PDMS if there remain residual Si–H groups in the PDMS matrix.31,32 By using this property, a HAuCl4 precursor was added after the PDMS sponge was cured instead of mixing it with liquid PDMS precursor in advance. This method has an advantage over the premixing of HAuCl4 precursor with liquid PDMS, which is more common in other studies,30,33 because reduced Au NPs will be preferentially located at the pore interface rather than distributed inside the PDMS matrix. The preferential location of Au NPs on the pore interface increases the probability of Au NPs contacting TiO2 NPs, which is required for plasmonic photocatalysis.

The porous structure of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge and the distribution of TiO2 and Au NPs can be observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The SEM images in Figure 1 show the cross section of a PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge that has been cut to a thickness of 1 mm to reveal its internal structure. The PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge consists of pores between 90 and 900 μm, corresponding to the size of sugar particles, which are interconnected.

Figure 1.

SEM images and corresponding EDS spectra of the (a) cross section of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge. (b,d) Area corresponding to the pore/air interface shows attached NPs, whereas the (c,e) area corresponding to the PDMS matrix shows no presence of NPs.

TiO2 NPs are observed at the pore/air interface (Figure 1b), with TiO2 NPs not observed within the PDMS matrix (Figure 1c). Although Au NPs were not identified in the SEM images, the existence of both TiO2 and Au NPs at the pore/air interface, not inside the PDMS matrix, was confirmed by the presence of Ti and Au peaks in the energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis of those areas (Figure 1b,d). In EDS analysis, the Au peak is shown to partially overlap with the Pt peak, with Pt used to coat samples for SEM and EDS measurement in this work; the enlarged EDS spectrum was used to distinguish between the two peaks and shows the existence of Au at the pore/air interface (Figure S2). These results indicate that TiO2 and Au NPs are preferentially located at the pore interface rather than inside the PDMS matrix, which is beneficial for the photocatalytic reaction.

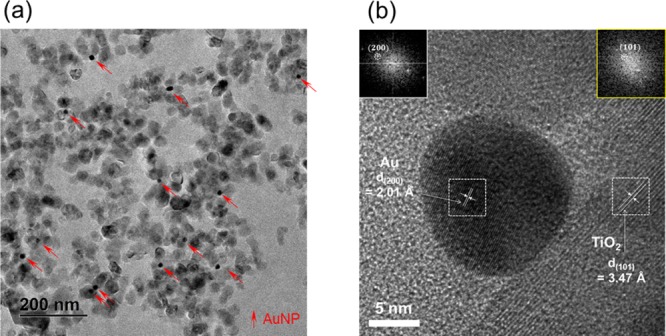

To confirm the attachment of Au NPs to the surface of TiO2 NPs, necessary for the synergistic plasmonic photocatalytic effect, thin slices of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge, which are sectioned by the ultra-microtome after filling LR-White resin into its pores, were imaged by TEM (Figure 2). The high-resolution TEM images show the presence of Au NPs attached to the surface of TiO2 NPs, which can induce the plasmonic photocatalytic effect. The reduced Au NPs are mostly spherical with sizes from 3 to 15 nm (Figures 2a and S3). The interplanar spacing of 2.01 and 3.47 Å correspond to the (200) and (101) lattice planes of Au and TiO2, respectively (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) TEM images of the ultra-microtome sample of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge. Au NPs are indicated by the red arrows. (b) High-resolution TEM image of the Au NP attached to the surface of the TiO2 NP with their interplanar spacing indicated.

Au NPs in this size range can show LSPR properties under visible light irradiation. To identify an LSPR peak from Au NPs, the diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) of the PDMS–NP sponges were measured (Figure 3). The PDMS sponge shows negligible absorption for wavelengths larger than 350 nm. In the case of the PDMS–TiO2 sponge, strong absorption is observed for wavelengths less than 400 nm, which is characteristic of TiO2 NPs (Figure S4). Furthermore, the PDMS–Au sponge shows a peak in the visible region (∼530 nm) corresponding to the typical LSPR peak of Au NPs, indicating the formation of Au NPs.

Figure 3.

UV–vis DRS of PDMS sponge, PDMS–TiO2 sponge, PDMS–Au sponge, and PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge.

In the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge, the characteristic absorption of both TiO2 and Au NPs was observed. The sudden increase in absorption for wavelengths less than 400 nm is attributed to the TiO2 NPs, whereas a peak at approximately 550 nm is attributed to the LSPR of the Au NPs. The red shift of the LSPR peak of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge compared to that of the PDMS–Au sponge is related to the attachment of Au NPs on the surface of TiO2 NPs that have higher refractive index than PDMS. This also demonstrates the close contact of Au NPs to the surface of TiO2 NPs in the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge.

2.2. Photocatalytic Decomposition of Organic Dyes

The rhodamine B (RB) concentration is proportional to its absorbance; therefore, in order to track the changes in RB concentration (C/Co), the changes in the absorption peak value at 550 nm were observed during its photocatalytic decomposition. The RB decomposition under UV (365 nm) and visible (513 nm) light irradiation by light-emitting diodes (LEDs) without any PDMS sponge was negligible for the LED intensity used in this experiment.

2.2.1. PDMS Sponge

As a control experiment, a pure PDMS sponge without TiO2 or Au NPs was tested to see if it can decompose RB. Under dark, UV, and visible light conditions, the absorption spectra of the RB solution did not change for 6 h except for a 5–10% decrease during the initial wetting process of the PDMS sponge (Figure S5). As the amount of initial RB absorption by the PDMS pores is dependent on the porous volume of the PDMS sponge, it can slightly vary from sample to sample. Thus, for a proper comparison of decomposition rates, the RB concentration value was normalized by its value measured at the start of light irradiation (C/Co) and plotted. Therefore, in the horizontal axes of the plots, time zero indicates the start of light irradiation at which the C/Co value was set to 1 for all conditions.

2.2.2. PDMS–TiO2 Sponge

With the PDMS–TiO2 sponge, the RB concentration significantly decreased under UV light, whereas it was near constant under dark and visible light conditions (Figure 4a). This is consistent with the photocatalytic property of TiO2 that is active only for UV light.34 Moreover, it shows that TiO2 NPs are not completely embedded in the PDMS sponge but are exposed to the RB solution as expected. The catalytic reaction would not occur unless the surface of the TiO2 NPs is exposed when embedded in the PDMS matrix.

Figure 4.

Relative RB concentration (initially, 20 μM) change, monitored by the change in RB absorption peak value with time in the presence of (a) PDMS–TiO2, (b) PDMS–Au, and (c) PDMS–TiO2–Au sponges under dark, UV (365 nm), and visible (513 nm) light conditions, respectively. (d) Three data sets plotted on one graph for comparison.

The decomposition of RB can be described by the following well-known mechanism.

When photons are absorbed by TiO2, electron and hole pairs can be generated inside TiO2

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

Here, TiO2* is the excited state of TiO2, eCB– is a photoexcited electron in the conduction band, hVB+ is a photogenerated hole in the valence band, OH• is a hydroxyl radical, OHad– is an adsorbed hydroxide ion, and O2•– is a superoxide. The abovementioned active species are strong oxidants and contribute to the photocatalytic decomposition of RB. However, no photocatalytic effect can be observed under visible light irradiation because the photon energy is not sufficient to overcome the band gap of TiO2.

Light scattering by PDMS pores themselves will not affect the RB decomposition rate significantly, because PDMS pores scatter rather than absorb light and multiple light scattering events at pores can result in a homogeneous distribution of light intensity over the entire PDMS sponge. Thus, scattered light inside the PDMS can be substantially absorbed by TiO2 before escaping from the PDMS sponge.

2.2.3. PDMS–Au Sponge

Interestingly, RB decomposed even in dark conditions, although this was significantly slower than under light for the PDMS–Au sponge (Figure 4b). This can be attributed to the catalytic, not photocatalytic, activity of the Au NPs. It is known that Au NPs of less than 5 nm in diameter can be catalytically active for several chemical reactions.35 As Au NPs reduced by the PDMS sponge have various sizes, as shown in the TEM images (Figure S3), with some Au NPs less than 5 nm, they are expected to contribute to the catalytic reaction even in dark conditions. However, this is considerably less efficient than the photocatalytic reaction.

Under UV and visible light, RB decomposed faster than under dark conditions. In particular, the RB decomposition rate under visible light was higher than under UV light. Previously, it was shown that the catalytic activity of Au NPs can be greatly enhanced by hot electrons that can decay from surface plasmons excited in Au NPs by light.36−38 In this case, Au NPs larger than 5 nm can show photocatalytic activity if they demonstrate LSPR. Therefore, a larger number of Au NPs can contribute to the photocatalytic reaction than those under dark conditions, which can be an additional contribution to the decomposition of RB under light. The faster decomposition rate of RB under visible light than under UV light can also be understood in terms of a hot-electron-mediated photocatalytic reaction because Au NPs have maximal LSPR efficiency in visible light.

The RB dye can decompose either by an indirect pathway through the reaction with strong oxidants, which can be photocatalytically generated from water at the surface of Au NPs, or by a direct pathway in which the RB dye adsorbed to the surface of Au NPs can decompose. As the RB dye contains four N-ethyl groups on both sides of the xanthene moiety, it adsorbs on the surface of Au NPs through electrostatic interaction.38−40

2.2.4. PDMS–TiO2–Au Sponge

Under dark conditions, RB decomposed at a rate similar to that of the PDMS–Au sponge (Figure 4c). This demonstrates that the catalytic activity under dark conditions must originate from Au NPs and not TiO2 NPs, as previously expected.

Under UV light, the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge showed a 1.8 times faster RB decomposition rate than the PDMS–TiO2 sponge, and a 7.4 times faster rate than the PDMS–Au sponge (Figure S6). If TiO2 and Au NPs independently contribute to RB decomposition, then the RB decomposition rate of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge should be similar to the addition of rates of the PDMS–TiO2 sponge and the PDMS–Au sponge. However, the experimentally measured RB decomposition rate of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge was greater than the simple addition of the rates of the other two sponges. This suggests a synergistic effect between TiO2 and Au NPs for photocatalysis.

This enhanced photocatalytic effect is expected to come from TiO2 NPs directly contacting Au NPs. When Au NPs are reduced from HAuCl4 in the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge, they can randomly form over the surface of the pores, with some forming close to TiO2 NPs partly embedded in the surface of PDMS pores (Figure 2). At the interface of TiO2 and Au NPs, a Schottky junction is formed, which builds up an internal electric field (the space-charge region) inside TiO2 NPs.16 As this internal electric field in TiO2 can reduce the recombination rate of generated electrons and holes by pushing them in different directions, the photocatalytic efficiency of contacting TiO2 and Au NPs can be enhanced compared to TiO2 NPs alone. This is likely responsible for the higher RB decomposition rate of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge than the PDMS–TiO2 sponge under UV light.

A more impressive characteristic of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge is its photocatalytic efficiency under visible light. It shows a high RB decomposition rate under visible light, which is comparable to that under UV light. This is unexpected when considering the almost negligible (110 times slower) RB decomposition rate in the PDMS–TiO2 sponge and mild (4.7 times slower) RB decomposition rate in the PDMS–Au sponge under visible light (Figure S6). It is speculated that the enhancement in the photocatalytic efficiency of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge under visible light is related to the synergistic property of TiO2 and Au NPs contacting each other, which is similar to the UV case.

The Schottky junction effect can work under visible light irradiation as well. However, under visible light, another advantage based on the LSPR effect of Au NPs can play an important role in enhancing photocatalytic efficiency.16 Visible light can excite surface plasmons on Au NPs, which can nonradiatively decay into hot electrons. These hot electrons generated at Au NPs can be used directly for the catalysis of molecules adsorbed on the Au NP surface as in the PDMS–Au sponge case,36 or can be injected into the conduction band of contacting TiO2 NPs to generate another electron–hole pair.17,18,20 By the latter mechanism, the electron–hole pair, necessary for catalysis, can be generated in TiO2 even under visible light, despite the photon energy being insufficient to directly overcome the band gap of TiO2.

To check the possible contribution of the RB sensitization effect on the high RB decomposition rate under visible (513 nm) light, the decomposition of methylene blue (MB) with the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge was investigated under the same light conditions (Figure S7). As the absorption band of MB that peaks at 664 nm is far from 513 nm, the dye sensitization effect can be excluded in the MB decomposition under the 513 nm light. The MB dye showed significant decomposition under 513 nm light, which shows that the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge has photocatalytic activity under visible light even without the photosensitization effect. We believe that the LSPR effect of the Au NPs is responsible for the high photocatalytic activity of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge.

However, it should be noted that the RB decomposition rate under visible light with the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge was comparable to that under UV light, whereas the MB decomposition rate under visible light was approximately two times lower than under UV light. This indicates that the photosensitization effect also contributes to the photocatalytic dye decomposition of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge. However, the negligible decomposition of RB under visible light in the case of the PDMS–TiO2 sponge indicates that the dye photosensitization effect under our experimental conditions is insignificant without Au NPs. Therefore, the fast RB decomposition with the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge under visible light is mostly attributed to the LSPR effect of Au NPs.

Furthermore, the hypsochromic shift of the absorption peak observed during the RB decomposition with the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge, under both UV and visible light, indicates the formation of N-de-ethylated intermediates (Figure S8).39,41−43 It has been reported in literature that the N-de-ethylation of RB can selectively occur depending on the adsorption state of RB on the TiO2, but the case for RB with hybrid TiO2–Au NPs has not been studied well. A more detailed study on the hypsochromic peak shift would be beneficial for understanding the adsorption state of RB on the hybrid TiO2–Au NPs.

Extending the absorption wavelength range from UV to visible can be beneficial for photocatalysis using solar light because visible light accounts for a larger portion of the solar spectrum than UV light. Therefore, the effective use of both UV and visible light for photocatalysis can significantly enhance photocatalytic efficiency under solar light.

2.3. Recyclability Test

In practical applications, maintaining photocatalytic efficiency for multiple usages is an important performance criterion. To test the recyclability of our PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge, its efficiency for RB decomposition was monitored for four cycles (Figure 5). The PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge was washed with deionized water several times between each cycle. A similar RB decomposition rate for all four cycles indicates that our PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge can be repeatedly used at least four times. It also indicates that the TiO2 and Au NPs in the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge attach quite strongly to the surface of PDMS pores. This is due to the partial embedding of TiO2 on the pore interface of PDMS and the direct reduction of Au NPs during fabrication rather than postphysical adsorption. To further confirm that TiO2 and Au NPs are not released from the PDMS sponge with time, the extinction spectrum change of water solution in the presence of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge was monitored, but no change was observed for over 3 h (Figure S9). This indicates that TiO2 and Au NPs are not detached from the PDMS matrix during normal photocatalytic reaction.

Figure 5.

Recyclability of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge for decomposition of RB dye.

3. Conclusions

A floating, porous plasmonic photocatalyst consisting of TiO2 and Au NPs immobilized on the surface of PDMS sponge pores was prepared by using a facile sugar-template method. The photocatalytic efficiency under UV and visible light was studied by monitoring the RB decomposition rate under each condition. The PDMS–TiO2–Au composite sponge showed significantly higher photocatalytic efficiency than the PDMS–TiO2 or PDMS–Au sponges under UV and visible light. In particular, the enhancement of the photocatalytic efficiency under visible light was remarkable, and is expected to originate from hot-electron injection by LSPR and the Schottky junction effect. Moreover, it was demonstrated that the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge is stable enough to be recycled several times. Owing to its high photocatalytic performance and simple fabrication, the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge is a promising material for solar light-based wastewater treatment.

4. Experimental Methods

4.1. Fabrication of PDMS Sponge, PDMS–TiO2 Sponge, and PDMS–TiO2–Au Sponge

A PDMS sponge was fabricated using a sacrificial sugar cube template method (Scheme 1).27 A 10:1 ratio mixture of PDMS prepolymer (Sylgard 184 A, Dow Corning, 15 g) and curing agent (Sylgard 184 B, Dow Corning, 1.5 g) was placed in a Petri dish and degassed in a vacuum chamber for 30 min to get rid of air bubbles. A sugar cube (CJ CheilJedang) was added to the PDMS precursor and then placed under vacuum for an additional 2 h. The empty pores of the sugar cube were filled with PDMS precursor by the capillary force. The filled sugar cube was placed in a convection oven at 60 °C and cured for 6 h. After curing, the sugar was removed by dissolving in water, leaving a PDMS sponge. The remaining water in the PDMS sponge was removed by drying in the convection oven.

To make a PDMS–TiO2 sponge, first, TiO2 NPs (15 nm, anatase, Nanostructured & Amorphous Materials, Inc.) were dispersed in anhydrous ethanol to make a 4.7% (w/v) solution. This was sonicated for 30 min. Then, 800 μL of TiO2 NP solution in ethanol was injected into the sugar cube to decorate porous interfaces of the sugar cube with TiO2 NPs. This TiO2-containing sugar cube was used to absorb the PDMS precursor under vacuum for 8 h to make a PDMS–TiO2 sponge. Because TiO2 NPs are initially located at the sugar/PDMS precursor interface and the PDMS precursor cannot penetrate into the sugar crystal, the TiO2 NPs after the curing of PDMS and washing out of sugar will be exclusively located, and partly embedded, at the porous interface of the PDMS sponge.30 Partial embedding of TiO2 NPs at the PDMS pore interface provides the stability (by the strong attachment on the PDMS matrix) and activity (by exposure of the uncovered TiO2 surface) of TiO2 NPs. The detailed procedure is similar to the above method to prepare the PDMS sponge. The TiO2 NPs lost during the sugar washing step was measured through the weight change. It was seen that 98% of the initial TiO2 NPs (totally, 37 mg of TiO2 per sponge) still remained in the PDMS sponge, indicating that TiO2 NPs were strongly attached to the PDMS pore interface.

To make a PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge, 0.25% (w/v) of HAuCl4·3H2O (Sigma-Aldrich) in anhydrous ethanol was prepared as the precursor solution for Au NPs. Then, a 1.5 mL solution of HAuCl4 precursor was injected into the preformed PDMS–TiO2 sponge and incubated in a convection oven at 60 °C for 6 h. Au NPs can be directly reduced from HAuCl4 precursor by the reducing ability of the residual curing agent of PDMS, as reported in previous studies.31,32 By injecting the HAuCl4 precursor solution into the pores of the preformed PDMS sponge, rather than forming the PDMS sponge from the mixture of HAuCl4 and liquid PDMS precursor, Au NPs can be located mostly on the pore interface rather than inside the PDMS matrix. This can be advantageous in plasmonic photocatalytic applications when compared with the previous PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge preparation method that uses an initial mixture of metal precursor and liquid PDMS before curing,30 because our method can increase the probability of contact between TiO2 NPs and Au NPs by attaching both of them at the pore interface, not inside the PDMS matrix. Furthermore, to make a PDMS–Au sponge, a PDMS sponge was used to reduce the Au NPs instead of a PDMS–TiO2 sponge. The Au NPs formed at the PDMS pore interface were hardly released from the PDMS sponge, which was confirmed from the negligible absorption change of water containing the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge for several hours (Figure S9). From this, it is known that a total of 1.9 mg of Au NPs were loaded on the PDMS–TiO2–Au or PDMS–Au sponges.

4.2. Structural and Optical Characterization of PDMS–NP Composite Sponges

The structure and morphology of the prepared sponges were investigated using SEM (Hitachi S-4700) after platinum coating, and their elemental composition was analyzed by EDS (HORIBA 7200-H). The DRS of the PDMS–NP composite sponges were measured by the spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-2450). For TEM images, the samples were embedded in LR-White resin (London Resin Co., London, UK) at 50 °C for 24 h, from which ultrathin sections (80–100 nm thickness) were prepared using an ultra-microtome with a diamond knife. Then, the sections were mounted on a copper grid and examined using TEM (Tecnai G2 F30 S-Twin, FEI).

4.3. Monitoring Degradation of RB by Photocatalytic Reaction

The experimental setup to monitor the photocatalytic degradation of RB (Sigma-Aldrich) consists of a quartz cuvette holder (Thorlabs, CVH100/M) connected to a halogen light source (Ocean Optics, HL-2000) and a spectrometer (Ocean Optics, USB 4000-VIS-NIR-ES) by optical fibers to measure the absorption spectra of RB in solution. Collimated LED light sources are incident on the quartz cuvette from above at a specific wavelength of light for photocatalysis. The UV LED (Thorlabs, M365L2-C1) emits light from 354 to 385 nm with a peak intensity at 365 nm. The green visible LED (Thorlabs, M530L3-C1) emits light from 484 to 562 nm with a peak intensity at 513 nm. The spectra of all LEDs are shown in Figure S1. The light from the LED was focused on the surface of the photocatalytic PDMS sponges at a power of 20 mW for both LEDs. During measurement, the solution was continuously mixed by a magnetic stirrer. The peak value at 550 nm in the absorption spectrum of RB was used to estimate the time-dependent changes in the RB concentration under each condition.

A photocatalytic PDMS sponge in the shape of a 9 mm × 9 mm × 9 mm cube was immersed in 3 mL of 20 μM RB aqueous solution in a quartz cuvette. Before starting measurement, the PDMS sponge was squeezed several times with tweezers to wet its pores. Then, the PDMS sponge was floated in the upper part of the RB solution. Once the pores in the PDMS sponge are filled with water, molecules dispersed in water can easily diffuse between the inside and outside of the pores. Prior to light irradiation, the RB solution containing the PDMS sponge sample was placed in the dark for 2 h to allow the dye and sample to reach adsorption-equilibrium. This process is useful to compare solely the photocatalytic activity of different hybrid sponges by eliminating the contribution of the initial RB adsorption on the PDMS pore surface, because the initial RB adsorption capacity of each sponge can be more dependent on the pore distribution of the PDMS sponge, which is difficult to exactly control with our fabrication method, than the properties of the NPs.

4.4. Recyclability Test

To test the recyclability of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge, after finishing the first photocatalytic measurement, it was separated from the previous RB solution, squeezed several times in distilled water for washing, and completely dried in a convection oven. Then, it was used again for a second photocatalytic measurement in fresh RB solution. All processes were the same as those in the first measurement. The measurements were repeated four times.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the MSIT of Korea government (NRF-2018R1A2B6007730) and by GIST Research Institute (GRI) grant funded by the GIST in 2019.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b04127.

Spectra of used LEDs; enlarged EDS spectra for the identification of Pt and Au peaks; TEM images of Au NPs attached to the TiO2 NPs in the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge; DRS of TiO2 NP powders; RB decomposition for the case of PDMS sponge without any NPs; comparison of RB decomposition rates obtained by linear fittings of log-normal plots; time-dependent change of absorption spectra of MB and RB dyes with the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge under light; and extinction spectra change of water solution in the presence of the PDMS–TiO2–Au sponge (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ S.Y.L. and D.K. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Schneider J.; Matsuoka M.; Takeuchi M.; Zhang J.; Horiuchi Y.; Anpo M.; Bahnemann D. W. Understanding TiO2 photocatalysis: Mechanisms and materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986. 10.1021/cr5001892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K.; Irie H.; Fujishima A. TiO2 photocatalysis: A historical overview and future prospects. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 44, 8269–8285. 10.1143/jjap.44.8269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M. R.; Martin S. T.; Choi W.; Bahnemann D. W. Environmental Applications of Semiconductor Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 69–96. 10.1021/cr00033a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann J.-M. Heterogeneous photocatalysis: Fundamentals and applications to the removal of various types of aqueous pollutants. Catal. Today 1999, 53, 115–129. 10.1016/s0920-5861(99)00107-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Shen S.; Guo L.; Mao S. S. Semiconductor-based photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6503–6570. 10.1021/cr1001645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata K.; Fujishima A. TiO2 photocatalysis: Design and applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2012, 13, 169–189. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2012.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Sun F.; Pan K.; Tian G.; Jiang B.; Ren Z.; Tian C.; Fu H. Well-Ordered Large-Pore Mesoporous Anatase TiO2 with Remarkably High Thermal Stability and Improved Crystallinity: Preparation, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 1922–1930. 10.1002/adfm.201002535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.; Zeng G.; Tang L.; Fan C.; Zhang C.; He X.; He Y. An overview on limitations of TiO2-based particles for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants and the corresponding countermeasures. Water Res. 2015, 79, 128–146. 10.1016/j.watres.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Liu L.; Yu P. Y.; Mao S. S. Increasing solar absorption for photocatalysis with black hydrogenated titanium dioxide nanocrystals. Science 2011, 331, 746–750. 10.1126/science.1200448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahi R.; Morikawa T.; Ohwaki T.; Aoki K.; Taga Y. Visible-light photocatalysis in nitrogen-doped titanium oxides. Science 2001, 293, 269–271. 10.1126/science.1061051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; Zhou W.; Zhang X.; Sun B.; Wang L.; Pan K.; Jiang B.; Tian G.; Fu H. Self-floating amphiphilic black TiO2 foams with 3D macro-mesoporous architectures as efficient solar-driven photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2017, 206, 336–343. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.01.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Li W.; Wang J.-Q.; Qu Y.; Yang Y.; Xie Y.; Zhang K.; Wang L.; Fu H.; Zhao D. Ordered Mesoporous Black TiO2 as Highly Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Photocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9280–9283. 10.1021/ja504802q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B.; Zhou W.; Li H.; Ren L.; Qiao P.; Li W.; Fu H. Synthesis of Particulate Hierarchical Tandem Heterojunctions toward Optimized Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1804282. 10.1002/adma.201804282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primo A.; Corma A.; García H. Titania supported gold nanoparticles as photocatalyst. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 886–910. 10.1039/c0cp00917b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M.; Zhang J.; Cheng B.; Yu H. Enhancement of Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of Mesoporous Au-TiO2 Nanocomposites by Surface Plasmon Resonance. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 2012, 1–10. 10.1155/2012/532843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Chen Y. L.; Liu R. S.; Tsai D. P. Plasmonic photocatalysis. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013, 76, 046401. 10.1088/0034-4885/76/4/046401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavero C. Plasmon-induced hot-electron generation at nanoparticle/metal-oxide interfaces for photovoltaic and photocatalytic devices. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 95–103. 10.1038/nphoton.2013.238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochuveedu S. T.; Kim D.-P.; Kim D. H. Surface-plasmon-induced visible light photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanospheres decorated by au nanoparticles with controlled configuration. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 2500–2506. 10.1021/jp209520m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V.; Wolf E. E.; Kamat P. V. Catalysis with TiO2/Gold Nanocomposites. Effect of Metal Particle Size on the Fermi Level Equilibration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 4943–4950. 10.1021/ja0315199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubeen S.; Hernandez-Sosa G.; Moses D.; Lee J.; Moskovits M. Plasmonic photosensitization of a wide band gap semiconductor: Converting plasmons to charge carriers. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5548–5552. 10.1021/nl203457v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska E.; Abe R.; Ohtani B. Visible light-induced photocatalytic reaction of gold-modified titanium(IV) oxide particles: Action spectrum analysis. Chem. Commun. 2009, 241–243. 10.1039/b815679d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson A.; Kamat P. V. Semiconductor-metal nanocomposites. Photoinduced fusion and photocatalysis of gold-capped TiO2 (TiOa/Gold) nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 960–966. 10.1021/jp0033263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Z.; Zhang J.; Cui J.; Yin J.; Zhao T.; Kuang J.; Xiu Z.; Wan N.; Zhou W. Recent advances in floating TiO2-based photocatalysts for environmental application. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 225, 452–467. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D.; Handschuh-Wang S.; Zhou X. Recent progress in fabrication and application of polydimethylsiloxane sponges. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 16467–16497. 10.1039/c7ta04577h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; Li L.; Li B.; Zhang J.; Wang A. Durable superhydrophobic/superoleophilic PDMS sponges and their applications in selective oil absorption and in plugging oil leakages. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 18281–18287. 10.1039/c4ta04406a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C.; Yu C.; Cui L.; Song Z.; Zhao X.; Ma Y.; Jiang L. Facile Preparation of the Porous PDMS Oil-Absorbent for Oil/Water Separation. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1600862. 10.1002/admi.201600862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.-J.; Kwon T.-H.; Im H.; Moon D.-I.; Baek D. J.; Seol M.-L.; Duarte J. P.; Choi Y.-K. A polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) sponge for the selective absorption of oil from water. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 4552–4556. 10.1021/am201352w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman R.; Walker E.; Chowdhury S. TiO2-PDMS composite sponge for adsorption and solar mediated photodegradation of dye pollutants. J. Water Process Eng. 2018, 24, 74–82. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2018.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan M.; Shi X.; Lyu F.; Levy-Wendt B. L.; Zheng X.; Tang S. K. Y. Encapsulation of Single Nanoparticle in Fast-Evaporating Micro-droplets Prevents Particle Agglomeration in Nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 26602–26609. 10.1021/acsami.7b07773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.; Lee S.; Kim H. S.; Moon J. T.; Joo J. B.; Choi I. Multifunctional and recyclable TiO2 hybrid sponges for efficient sorption, detection, and photocatalytic decomposition of organic pollutants. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 73, 328–335. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Xu J.-J.; Liu Y.; Chen H.-Y. In-situ synthesis of poly(dimethylsiloxane)-gold nanoparticles composite films and its application in microfluidic systems. Lab Chip 2008, 8, 352–357. 10.1039/b716295m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R.; Kulkarni G. U. Removal of organic compounds from water by using a gold nanoparticle-poly(dimethylsiloxane) nanocomposite foam. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 737–743. 10.1002/cssc.201000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.; Lee S.; Jin C. M.; Kwon J. A.; Kang T.; Choi I. Facile Fabrication of Large-Scale Porous and Flexible Three-Dimensional Plasmonic Networks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 28242–28249. 10.1021/acsami.8b11055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Nanayakkara C. E.; Grassian V. H. Titanium dioxide photocatalysis in atmospheric chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5919–5948. 10.1021/cr3002092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvolbæk B.; Janssens T. V. W.; Clausen B. S.; Falsig H.; Christensen C. H.; Nørskov J. K. Catalytic activity of Au nanoparticles. Nano Today 2007, 2, 14–18. 10.1016/s1748-0132(07)70113-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S.; Libisch F.; Large N.; Neumann O.; Brown L. V.; Cheng J.; Lassiter J. B.; Carter E. A.; Nordlander P.; Halas N. J. Hot electrons do the impossible: Plasmon-induced dissociation of H2 on Au. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 240–247. 10.1021/nl303940z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubeen S.; Lee J.; Singh N.; Krämer S.; Stucky G. D.; Moskovits M. An autonomous photosynthetic device in which all charge carriers derive from surface plasmons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 247–251. 10.1038/nnano.2013.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H.; Chen X.; Zheng Z.; Ke X.; Jaatinen E.; Zhao J.; Guo C.; Xie T.; Wang D. Mechanism of supported gold nanoparticles as photocatalysts under ultraviolet and visible light irradiation. Chem. Commun. 2009, 7524–7526. 10.1039/b917052a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin M.; Li Z.; Kou J.; Zou Z. Mechanism investigation of visible light-induced degradation in a heterogeneous TiO2/eosin Y/rhodamine B system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 8361–8366. 10.1021/es902011h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata R.; Bhaskaran A.; Sadras S. R. Green-synthesized gold nanoparticles from Plumeria alba flower extract to augment catalytic degradation of organic dyes and inhibit bacterial growth. Particuology 2016, 24, 78–86. 10.1016/j.partic.2014.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Yao J.-n. Photodegradation of Rhodamine B catalyzed by TiO2 thin films. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 1998, 116, 167–170. 10.1016/s1010-6030(98)00295-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.; Zhao J.; Hidaka H. Highly selective deethylation of rhodamine B: Adsorption and photooxidation pathways of the dye on the TiO2/SiO2 composite photocatalyst. Int. J. Photoenergy 2003, 5, 209–217. 10.1155/s1110662x03000345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska E.; Remita H.; Hupka J.; Belloni J. Modification of Titanium Dioxide with Platinum Ions and Clusters: Application in Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 1124–1131. 10.1021/jp077466p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.