Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is the most common infectious cause of infant birth defects and an etiology of significant morbidity and mortality in solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. There is tremendous interest in developing a vaccine or immunotherapeutic to reduce the burden of HCMV-associated disease, yet after nearly a half-century of research and development in this field we remain without such an intervention. Defining immune correlates of protection is a process that enables targeted vaccine/immunotherapeutic discovery and informed evaluation of clinical performance. Outcomes in the HCMV field have previously been measured against a variety of clinical end points, including virus acquisition, systemic replication, and progression to disease. Herein we review immune correlates of protection against each of these end points in turn, showing that control of HCMV likely depends on a combination of innate immune factors, antibodies, and T-cell responses. Furthermore, protective immune responses are heterogeneous, with no single immune parameter predicting protection against all clinical outcomes and stages of HCMV infection. A detailed understanding of protective immune responses for a given clinical end point will inform immunogen selection and guide preclinical and clinical evaluation of vaccines or immunotherapeutics to prevent HCMV-mediated congenital and transplant disease.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, immune correlate, vaccine

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is the most common cause of intrauterine fetal infection, affecting 1 in every 150 live-born infants worldwide and often resulting in lifelong sequelae, such as hearing loss, brain damage, or neurodevelopmental delay [1, 2]. Furthermore, HCMV is the most prevalent infectious agent among solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients, frequently causing end-organ disease, such as gastroenteritis, pneumonitis, or hepatitis. Moreover, it has been claimed to predispose transplant recipients to graft rejection or failure [3, 4]. Nevertheless, we remain without a vaccine or a immunotherapeutic intervention to reduce the burden of HCMV-associated disease.

During natural infection, HCMV elicits robust cellular and humoral immune responses against a diverse array of viral proteins. The most common epitopes targeted by HCMV-specific cell-mediated immunity are pp65, IE1, and UL148, although T-cells have been detected against peptides encoded by 151 unique HCMV open reading frames [5]. Furthermore, the HCMV genome encodes an estimated 54 membrane-associated proteins (≥25 of which are glycoproteins) that may assemble into protein complexes on the virion envelope [6, 7]. Neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) are known to target a number of these membrane-associated proteins/complexes, interfering with the processes governing viral entry into the host cell. Glycoproteins gM and gN form a heterodimeric protein complex that facilitates viral tethering to the cell membrane and targeting to the entry receptor [8]. Glycoprotein gB and the heterodimer gH/gL are relatively conserved among herpesviruses and critical for cellular entry [9–11], and gH/gL must further interact either with glycoprotein gO (gH/gL/gO), forming a trimeric protein complex required for infection of all cell types, or with proteins UL128, UL130, and UL131 (gH/gL/UL128/UL130/UL131A), forming a pentameric complex that enables viral entry into specific cell types, including endothelial and epithelial cells and monocytes and macrophages [12, 13].

A major focus of HCMV vaccine research is the study of correlates of protection (CoPs)—immune markers that associate with a reduction in the incidence of infection or clinical disease. A well-validated CoP, which can serve as an end point for vaccine and immunotherapeutic development and provide a means of quantitative evaluation of protective immunity in clinical trial, is the “holy grail” of vaccine development. CoPs might also have the potential to guide clinical preemptive/prophylactic treatment of patients at risk for HCMV-associated pathologies. Herein, we will use the nomenclature proposed by Plotkin and Gilbert [14], in which a CoP represents a statistical relationship between an immune marker and protection, although that does not imply causality. CoPs can be subsequently designated as mechanistic if the identified immune response is a causal agent of protective immune function. The discovery of a CoP has the potential to fundamentally transform vaccine research efforts toward a productive outcome, such as the paradigm shift observed in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vaccine field toward antibody-based vaccines after identification of an antibody-mediated CoP [14, 15].

It is worth noting that many highly effective vaccines were developed without an identified CoP, including vaccines for rotavirus, human papillomavirus, and varicella-zoster virus. However, empiric, trial-and-error methods have failed (or had limited efficacy) for many complex pathogens including malaria, tuberculosis, and HCMV [16]. While the biologic mechanisms employed by these 3 pathogens differ vastly, each uses powerful mechanisms of immune evasion, such that host immunity elicited by natural infection is not sufficient to protect against subsequent infection (“superinfection”) and/or the establishment of latency. We hypothesize that CoP-directed rational vaccine development will be essential for HCMV and other complex pathogens to stimulate production of immune factors that are more protective than natural pathogen-elicited immunity.

The HCMV field is highly fragmented, posing an additional challenge for development of immune interventions against HCMV. One source of fragmentation is that HCMV causes a variety of diseases in diverse patient populations, and thus parallel research areas have emerged for congenital and transplant-associated infections, with few shared research initiatives between them. A second cause of fragmentation is separate research efforts for HCMV-naive and HCMV-seropositive populations. HCMV-naive populations have historically been the focus of vaccine development efforts, because of the enhanced severity of the disease as well as the logistic challenge of identifying superinfection events. However, there is increasing evidence that a significant burden of HCMV disease is caused by secondary maternal HCMV infection [2] and donor-positive, recipient-positive transplantation [17]. In this analysis, we consider congenital and transplant-associated pathology as well as primary infection and superinfection in parallel, seeking to emphasize the common biologic underpinnings (and CoPs) of infection that tie these fields together.

All HCMV vaccine/immunotherapeutic research shares a single goal—to develop an intervention that augments the host immune response or impairs viral function to reduce the burden of HCMV-associated disease. We propose 3 stages of infection might be intervened in to prevent the development of HCMV disease in diverse settings: (1) virus acquisition (resulting in seroconversion), (2) systemic replication, and (3) disease pathogenesis. Each stage of infection occurs at a distinct anatomic site with unique host and viral biologic characteristics, and therefore CoPs that are probably not wholly overlapping. We cannot assume, for example, that an immune factor correlated with reduced mucosal HCMV acquisition can also protect against HCMV viremia. In this analysis, we will discuss identified CoPs for each strategic intervention in succession, highlighting promising findings and commonalities for future evaluation of vaccines/immunotherapeutics to eliminate this threat to both pediatric and transplant-associated health.

REDUCING THE INCIDENCE OF HCMV INFECTION

HCMV is most commonly transmitted by mucosal contact with virus shed in bodily fluids, including saliva, urine, breast milk, and genital fluids [18], though 2 notable exceptions are donor-recipient transmission via organ transplantation from an HCMV-seropositive donor and maternal-fetal placental transmission. There are 2 clear strategies to preventing mucosal transmission: reduce mucosal shedding in infected individuals and prevent acquisition via induction of protective immunity. Although the overall rate of HCMV acquisition is relatively low, at about 2%–3% of seronegative individuals per year [19, 20], in certain high-risk populations this metric is closer to 5%–10% per year, suggesting that a strategy to decrease the incidence of HCMV infection could be quite effective [19]. Any intervention designed to disrupt horizontal virus transmission (eg, vaccination, reducing saliva sharing between mother and infant, and antimicrobial disruption of transmission chains) might significantly decrease the number of new infections and thereby decrease the burden of congenital and transplant-associated disease.

A major challenge for preventing HCMV acquisition is that the incidence and anatomic site of shedding vary by age and population demographic. A meta-analysis drawing from a diverse variety of populations identified that HCMV shedding was detectable in approximately 7% of normal, healthy adults at any given time—most commonly in vaginal fluid and semen [21]. Children, in contrast, have higher-magnitude and more durable viral shedding in urine and saliva than adults, with virus detectable in up to 23% of those enrolled in daycare [21]. Among highly seropositive populations, breast milk is an extremely common route of transmission [22, 23]. It remains unknown whether CoPs will be generalizable in each transmission setting. Any vaccine will therefore need to evaluated in multiple patient populations before CoPs will be qualified or shown to be common to different settings.

Decreasing Viral Shedding

Robust and mature CD4+/CD8+ T-cell responses are associated with better control of HCMV shedding. For example, shedding is particularly common in persons living with HIV, and shedding magnitude is well correlated with markers of HIV-mediated immune suppression and disease progression (decreased CD4+ T-cell count, elevated HIV load) [24]. Furthermore, young children, with a decreased frequency of HCMV-specific CD4+ T-cells compared with older children or adults [25], consistently shed virus more frequently and at a higher magnitude [26–28]. In addition, infants with congenital HCMV infection have an altered functional profile of HCMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells [29], and age-related maturation of the HCMV-specific CD4+/CD8+ T-cell response is associated with a decline in urinary shedding [30].

Of note, human clinical studies have not identified any correlation between HCMV-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and the magnitude or frequency of shedding [31]. Furthermore, very little data regarding the impact of vaccination on HCMV shedding has been generated in human cohorts, because reduced shedding has not been a primary outcome of clinical trials to date. However, Nelson et al [33] previously reported that recipients of the gB/MF59 vaccine, a platform known to elicit robust titers of gB-specific IgG, immunoglobulin A (IgA), and secretory IgA in salivary glands [32], had reduced peak HCMV shedding in saliva compared with placebo recipients after acute infection.

Rhesus CMV (RhCMV) in nonhuman primates very accurately reflects HCMV pathogenesis in humans owing to a high degree of host and virus similarity [34], including conserved antiviral immune responses and mechanisms of viral immune evasion [35–39]. Vaccination of rhesus monkeys with DNA-encoding RhCMV antigens (with or without modified vaccinia ankara (MVA) boost) can dramatically reduce mucosal shedding of virus [40, 41], with shedding inversely correlated with increasing number of peripheral pp65-specific CD8+ T-cells. Nelson et al [42] have also observed in a rhesus monkey model that preexisting, potently-neutralizing Abs alone can delay the onset of RhCMV shedding in urine and saliva after maternal primary infection, although they do not seem to affect the level of peak shedding.

One special case that must be considered is maternal shedding of HCMV in breast milk. Indeed, in seropositive populations, maternal breast milk shedding is believed to account for the majority of postpartum HCMV acquisition [43], with an estimated 40%–60% of children born to seropositive mothers having seroconverted by 12 months of age [44, 45]. Because the magnitude of breast milk shedding may correlate with the risk of infant postnatal HCMV acquisition [46], even a modest reduction in HCMV shedding in breast milk could have a large impact on the proportion of infants who acquire HCMV postnatally. Although the vast majority of breast milk acquisition events are asymptomatic without sequelae, susceptible populations (eg, immunocompromised, very low-birth-weight infants) may be at increased risk for HCMV-associated disease processes [47, 48]. Many questions remain concerning whether maternal immune factors can impede virus transmission and/or reduce the severity of infant disease [43], though both HCMV-specific IgA [49] and pp65-specific CD8+ T-cells [50] have been correlated with reduced breast milk shedding of HCMV.

Blocking Mucosal HCMV Acquisition

Given the exceedingly complex array of immune evasion proteins and microRNAs used by HCMV to prevent clearance from the body [51] as well as the virus's remarkable ability to replicate in diverse cell types (including fibroblasts, endothelial/epithelial cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, smooth muscle cells, stromal cells, neuronal cells, and hepatocytes), blocking virus acquisition at the mucosal barrier constitutes a major challenge [52]. Presumably potent anti-HCMV immune factors must be present at the site of infection to inhibit initial cellular infection/spread, and the CoPs of these factors remain poorly understood. Previously trialed vaccine strategies have achieved partial protection against HCMV acquisition, however, suggesting that this goal is achievable [53]. Indeed, the size of the viral genome and complexity of the viral reproductive cycle may work to our advantage.

A 2017 study revealed that HCMV is exceedingly inefficient at initiating sustained replication at mucosal sites [54]. Computational modeling of salivary viral dynamics indicates that that HCMV infection typically begins with a small inoculum that spreads inefficiently to neighboring cells, with each cell propagating the infection to 1.1 neighboring cells on average [54]. In addition to the inefficient transfer from cell to cell, HCMV spreads inefficiently from person to person, with an epidemiologically estimated basic reproduction number (R0) of about 2.4. This translates into a low target of 50%–60% of the population who must have effective immunity against HCMV to allow for complete virus eradication through herd immunity [19, 20].

Despite the multiple immune evasion strategies used by HCMV, there is excellent evidence that the incidence of HCMV acquisition can be reduced through vaccination. In a phase 2 clinical trial, postpartum seronegative women were administered an HCMV glycoprotein B subunit vaccine plus MF59 squalene adjuvant, which achieved a 50% reduction in the rate of virus acquisition (defined by seroconversion against a non-gB HCMV antigen; P = .02) [53]. When this study was subsequently repeated in a population of adolescent girls there was a 43% reduction in virus acquisition among gB/MF59 vaccinees, though this finding was not statistically significant [55]. Although this vaccine did not achieve the desired clinical end point, the results clearly demonstrate partial efficacy in achieving sterilizing immunity—a unique finding among herpesvirus vaccine development efforts [56].

The gB/MF59 vaccine has been well characterized to elicit extremely robust, high-avidity antibody responses [57, 58]. Intriguingly, our investigative team that gB-specific antibodies in vaccinated seronegative postpartum women and transplant recipients were predominantly nonneutralizing [58, 59]. However, we identified little antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity or natural killer (NK) cell degranulation activity mediated by gB/MF59-elicited antibodies against HCMV-infected cells [58]. Furthermore, NK activation directed against gB antigen was not associated with protection from HCMV acquisition in either of these patient cohorts [58, 59].

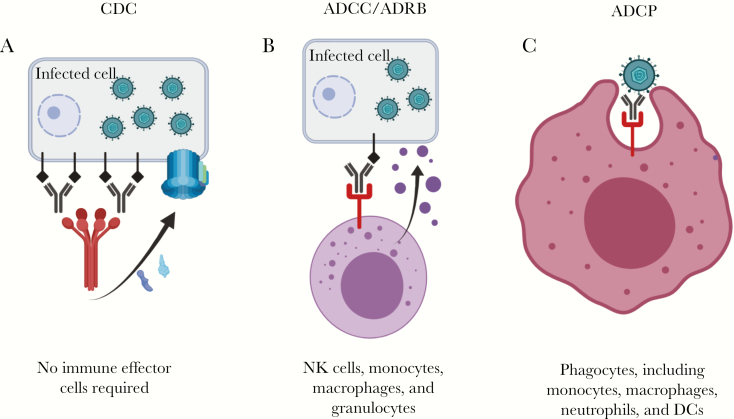

In the study of serum samples from postpartum women we did identify that gB/MF59 vaccine-elicited antibodies could robustly mediate antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis. This function has not previously been associated with protection against HCMV acquisition, and the magnitude of phagocytosis activity did not seem to be associated with infection outcome in this study [58]. Other antibody effector functions may account for the partial vaccine protection observed, including complement-mediated cytotoxicity or antibody-dependent respiratory burst, although they were not assessed in this study. Potentially protective, nonneutralizing antibody functions are shown in Figure 1. The role of CD4+/CD8+ T-cells in gB/MF59-elicited vaccine protection against virus acquisition remains unknown, although it is possible that these cell populations played a role, because MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccines can elicit antigen-specific T-cells.

Figure 1.

Antibody-dependent, nonneutralizing functions that may have contributed to gB/MF59 vaccine efficacy. A, Complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). Antibodies bind to viral proteins on the surface of infected cell, then are cross-linked by c1q. This action causes an enzymatic cascade, culminating in the assembly of the membrane attack complex in the infected cell membrane. B, Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or antibody-dependent respiratory burst (ADRB), results from antibody binding a viral protein on an infected cell, then engaging the Fc receptor on an immune effector cell. This immunologic bridge triggers release of cytotoxic granules, which destroy the infected cell. C, Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) occurs when an antibody binds a virion then engages the Fc receptor on a phagocyte, triggering engulfment (and presumed destruction) of the virion. Abbreviations: DCs, dendritic cells; NK, natural killer.

BLOCKING HCMV REPLICATION

Intrahost replication of HCMV contributes to both transplant-associated and congenital disease. In immune-suppressed transplant recipients, HCMV activation and replication can lead to viremia, systemic dissemination, and seeding of tissues permissive to HCMV replication, resulting in end-organ disease [60]. Furthermore, for congenital HCMV transmission to occur, the virus must replicate systemically in a pregnant woman, seed the placenta, and traverse the placental barrier (this mechanism remains purely speculative) [61–63]. One caveat is that the biologic mechanism of placental transmission may be unique, given that trophoblasts (specifically syncytiotrophoblasts) have unique antiviral properties [64]. Regardless, in both transplant recipient and pediatric patient populations, controlling systemic replication and magnitude of viral load has been associated with reduced adverse outcomes [42, 65, 66].

Reducing HCMV Viremia and Systemic Dissemination

There are clinical cohort data suggesting that highly neutralizing, high-avidity antibodies may be correlated with a reduced incidence of congenital CMV [67, 68]. The role of nAbs in preventing HCMV reactivation and viremia in transplant recipients is less certain, because nAb therapies can reduce viremia [69] but have not been correlated with protection [59, 70]. nAbs are the best CoP for the vast majority of vaccines targeting viral pathogens [71], and they are believed to function by providing sterilizing immunity either through interference with virus attachment or virus-receptor interactions or by triggering a change in glycoprotein conformation [72]. Even robust levels of nAbs in human serum samples, however, cannot always prevent HCMV acquisition and replication in seropositive individuals (leading to superinfection).

One hypothesis for this phenomenon is that the virus remains predominantly cell associated in the presence of nAbs and able to infect neighboring cells without leaving the cellular compartment [73]. This theory is supported by the observation that nAbs limit spontaneous loss of HCMV RL13 and UL131A in tissue culture and cause the virus to remain almost exclusively cell associated [74]. Therefore, even potent nAbs may not be able to physically bind to virus and inhibit cellular spread after tissue infection [75], and thus their efficacy is presumably mediated through a reduction in viremia/systemic HCMV replication. Indeed, Nelson et al [42] observed elsewhere that potent nAbs dramatically reduced RhCMV load in a monkey model, which was associated with decreased congenital RhCMV transmission.

There are emerging data to suggest that CMV-specific, nonneutralizing antibodies may also facilitate an antiviral function that controls systemic viral replication [76]. In a murine model, both neutralizing and nonneutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were able to reduce systemic dissemination of virus [76]. Furthermore, although nAbs were not detectable in a study of gB/MF59-vaccinated transplant recipients, HCMV viremia magnitude and duration were inversely correlated with gB-specific antibody titer [59, 77]. As described above, the potential protective mechanism of these nonneutralizing antibodies remains poorly defined. Perhaps more generally, based on these findings, the induction of a nAb response by vaccination cannot be assumed to be a mechanistic CoP against viral dissemination.

Antibody binding to specific epitopes has been identified as a CoP against viremia and viral dissemination. In HCMV-seropositive individuals, binding to gB epitope AD2 (site 1) has been correlated with reduced viremia in solid organ transplant recipients [78] as well as with decreased incidence of HCMV congenital transmission [68]. The susceptibility of this epitope may explain why the AD2 region is a recombination hot spot [79, 80]. In addition, in pregnant women with primary HCMV infection, the rapid development of nAbs specific for the pentameric complex was identified as a CoP against congenital HCMV transmission [81], although this correlation was not observed in a cohort of seropositive pregnant women [82]. Finally, in a cohort of kidney transplant recipients, combined treatment with 2 mAbs targeting gH and the pentameric complex reduced HCMV reactivation and spread from seropositive donors [69]. These mAbs thus represent the first mechanistic CoP for HCMV and prove that antibodies have a role to play in the control of HCMV infection, even in hosts who are T-cell compromised.

It is worth noting that the specificity and function of antibodies is of paramount importance and that viremia or disease cannot be controlled by just any HCMV-specific antibodies. In the setting of nAbs, we expect an inverse association between systemic viral burden and functional antibody titer. Yet in a cohort of HCMV-seropositive kidney transplant recipients, the magnitude of HCMV viremia was observed to be directly correlated with anti-HCMV antibody titers [83], which probably occurs because of either (1) an inability of this immune-suppressed population to mount a robust immune response with affinity-matured, functional nAbs or (2) IgG responses mounted against nonprotective epitopes. In addition, it has been reported that women who are symptomatic and/or transmit HCMV to their infants have a higher overall quantity of circulating HCMV-specific IgG, although lower levels of nAbs [67, 84].

Furthermore, a randomized trial demonstrated that passive infusion of CMV hyperimmune globulin (CMVIG) after primary infection during pregnancy did not decrease the incidence of infant infection [85]. We might hypothesize that the reason for a lack of efficacy was either (1) ineffective dose magnitude or kinetics or (2) poor efficacy of the intervention. Results from a recent investigation suggest that biweekly (rather than monthly) administration of CMVIG is more effective in reducing congenital CMV in women with primary infection [86], although this was merely an observational study, and a subsequent randomized, controlled trial is warranted. Furthermore, it is unclear whether CMVIG is the best clinical product for intervention, because this purified γ-globulin product has fairly poor HCMV-neutralizing activity [87]. Whether passive infusion of a more potently neutralizing product might have enhanced efficacy is unknown. Researchers have speculated that low-avidity, nonneutralizing antibodies can bind the virus and facilitate viral transmission across the placenta through Fc-mediated transcytosis [88]. However, no enhancement of placental or fetal infection was observed during the randomized, controlled trial described above [89].

The lack of immune protection from poorly matured antibodies emphasizes the importance of CD4+ T-cell responses, which have been correlated with both control of viremia and reduced congenital transmission. CD4+ T-cell responses were delayed in symptomatic compared with asymptomatic renal transplant recipients [90], and the development of virus-specific CD4+ T-cells is associated with control of HCMV load [91, 92]. Indeed, more rapid development of HCMV-specific CD4+ T-cells after primary infection has been repeatedly associated with decreased congenital virus transmission [93–95]. In particular, higher frequency of CD4+ cells with interleukin 7R+ memory phenotype was linked with better control of viremia and a lower risk of congenital transmission [96]. We hypothesize that this is primarily due to the impact of CD4+ T-cells on antibody maturation, because depletion of CD4+ T-cells in a monkey model resulted in delayed RhCMV-specific antibody responses, universal RhCMV transplacental transmission, and fetal abortion [97, 98]. Furthermore, preexisting potent nAbs were able to prevent congenital infection altogether in CD4+ T-cell–depleted monkeys, suggesting that this cell population might potentially be dispensable in the presence of highly functional antibody responses [42].

Peripheral CD8+ T-cells have also been correlated with control of viremia in both solid organ and HSCT recipients [99–101]. A startling 5%–30% of circulating T-cells are HCMV specific, suggesting that this high proportion of cytotoxic T lymphocyte immunity is required to maintain control against viral reactivation [102]. In particular, functional impairment of HCMV-specific T-cells (ie, failure to produce interferon γ in response to stimulation) was associated with a 14-fold increase risk of high-level HCMV replication, and a direct relationship was observed between the magnitude of the immune-dominant response against HCMV pp65 and HCMV load [99].

Furthermore, in the phase 2 trial of ASP0113 (DNA vaccine encoding both pp65 and gB) conducted in HSCT recipients, protection against HCMV viremia was correlated with the magnitude of the T-cell response against pp65 [103]. Specifically, polyfunctional CD8+ T-cells that are CD107−inteferon γ +/interleukin 2+/tumor necrosis factor α + were predicted to be protective against viremia in solid organ transplant recipients [104]. Given that CD8+ T-cell immunity is largely preserved throughout pregnancy, the possibility that highly functional CD8+ T-cells might reduce maternal viral load and also correlate with reduced likelihood of congenital transmission should be examined in future clinical trials.

Finally, there has been a great deal of interest in the role of circulating NK cells in blocking systemic HCMV replication. It has been demonstrated in the rhesus monkey model that RhCMV evasion of NK cells is essential for host initial infection and establishment of latency [105]. NK cells, though innate immune cells that cannot undergo somatic hypermutation to optimize antigen specificity, have been ascribed adaptive traits in mice as well as in humans [106]. One subpopulation of NK cells expressing activating receptor NKG2C undergoes memorylike expansion in response to HCMV, and the magnitude of this cell population has been correlated with an absence of HCMV viremia in both hematopoietic stem cell [107] and kidney transplant recipients [108]. Furthermore, in NKG2C receptor knockout umbilical cord samples, HCMV reactivation induces expansion of a population of NK cells expressing killer immunoglobulinlike receptors [109].

Thus, activating receptor NKG2C and inhibitory receptor expressing killer immunoglobulinlike receptors may be involved in the maturation of memorylike NK cells with anti-HCMV functions, and these are possible CoPs against HCMV viremia. Such observations have led to speculation that it may be possible to elicit expansion of a long-lived NK cell population with anti-HCMV activity via vaccination [110].

Inhibition of HCMV Replication in Tissues

Notably, HCMV can spread directly from cell to cell [111], and thus it is likely that nAbs cannot fully inhibit viral replication within tissues [75]. The pentameric complex has been described as critical to this immunologically covert means of viral transmission between cells [73], in part because the complex prevents release of cell-free virions. However, it is possible that the interactions between viral glycoproteins and neighboring cells that promote cell fusion and syncytia formation could be targeted by antibodies if they are accessible to circulating immunoglobulins [112]. In addition, a role for nonneutralizing antibodies in inhibition of replication in tissues and viral clearance has been proposed [76, 113], though no nonneutralizing function has been clearly identified as the mechanism of protection in clinical cohorts [58, 59].

Emerging evidence suggests that there are large populations of tissue-resident HCMV-specific memory T-cells in humans, localized and enriched [58] in sites of viral persistence [114]. Animal models have hinted at the critical importance of these tissue-resident memory T-cells in viral clearance [115–118]. In HCMV-seropositive pregnant women and transplant recipients, tissue-resident memory CD4+/CD8+ T-cells are likely to be critical for preventing HCMV tissue replication and tissue-localized viral pathogenesis [102]. Yet though these cell populations constitute approximately 97% of total body T-cells [119], relatively little is known about the identity, physiology, and function of tissue-resident T-cells in humans, including how this population is affected by vaccination, and further investigation is therefore warranted.

In addition, little is known about the role of tissue-resident NK cells in anti-HCMV immunity, though data suggest that this population comprises phenotypically and functionally distinct populations (reviewed in [120]). Given the role of peripheral NK cell populations in control of HCMV replication (described above), there is particular interest within the congenital HCMV research field regarding NK cells localized to the decidua (dNKs). Indeed, dNK cells account for approximately 50%–70% of the immune cells in the maternal layers of the placenta during the first trimester of pregnancy [120, 121]. This population of cells is phenotypically distinct (CD56brightCD16−CD160−) from peripherally circulating NK cells (CD56dimCD16+CD160+) and mildly cytotoxic with abundant expression of inhibitory receptors [122]. However, recent investigations have highlighted the ability of dNK cells to inhibit viral spread, identifying that dNK exposure to HCMV induces a shift in receptor expression to activating receptors (NKG2C, NKG2D, and NKG2E). This phenomenon is accompanied by enhanced dNK cytotoxic function and infiltration of HCMV-infected tissue in vivo, suggesting that activated dNK cells may be a CoP against placental transmission of HCMV [123, 124].

Similarly, there are defined NK cell populations in organs afflicted by transplant-associated HCMV disease, including lung and liver [120]. In these tissues, NK cells comprise approximately 20%–40% of total resident lymphocytes. To date, no role of intrinsic NK cell tissue populations in preventing or worsening HCMV-associated pneumonitis/hepatitis has been described. This deficit may be due to heterogeneity of receptor expression, which has hindered identification of cell populations by means of flow cytometry. There are hints that these tissue-resident NK cell populations are involved in antiviral immunity and may be a cause of end-organ disease [125–129], although ultimately the role of tissue-resident NK cells in the incidence of tissue-associated HCMV replication and disease has not been identified.

PROTECTION AGAINST HCMV DISEASE

One strategy to reduce the burden of HCMV disease might be to deploy an intervention aimed specifically at reducing clinical disease severity and improving long-term outcomes. CoPs against HCMV clinical disease may or may not overlap with those for the inhibition of viral dissemination, so in this review we consider the prevention of disease independently. HCMV can cause a vast constellation of disease in diverse populations. Transplant recipients can suffer from severe symptoms of HCMV tissue-invasive disease, including pneumonia, colitis, hepatitis, retinitis, and central nervous system disease, and disseminated disease is hypothesized to precipitate transplant rejection [3].

In addition, congenitally infected infants are frequently afflicted by growth abnormalities (eg, intrauterine growth restriction, and microcephaly) and/or severe neurologic complications (eg, sensorineural hearing loss, visual defects, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, and seizures) [1, 2]. In the congenital HCMV field, it is a challenge to design a trial with disease-associated sequelae as the outcome of interest, because only 1 in 150 pregnancies is affected by congenital HCMV infection, and sequelae will develop in only 1 in 5 infected newborns. The initial gB/MF59 vaccine trial, for example, was conducted in a high-risk patient population (postpartum women) and enrolled >400 participants, yet only 4 congenital infections were observed among infants born to vaccinated and unvaccinated women [53]. Thus, the vast majority of CoPs against HCMV congenital disease rely on animal models and surrogate markers of disease severity.

There are data to suggest that antibodies may reduce the severity of HCMV disease in both congenitally infected and transplant recipient populations. Multiple studies and a meta-analysis have demonstrated that therapy with polyclonal CMVIG improves outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients, increasing total survival and reducing rates of HCMV disease and death [130–133]. CMVIG does not decrease the incidence of congenital transmission when administered to pregnant women after primary HCMV infection [85], yet a nonrandomized, uncontrolled prospective cohort study reported reduced adverse infant outcomes (defined as neurologic or audiologic abnormalities, necrotizing enterocolitis, or chronic liver disease) among infants born to women administered CMVIG [134]. Supporting this finding, Nelson et al [42] observed in a monkey model that preexisting, polyclonal antibodies can prevent severe congenital infection manifested by fetal abortion.

It remains to be determined whether CMVIG can prevent placental pathology responsible for congenital growth abnormalities; researchers initially claimed a benefit to CMVIG therapy from an uncontrolled study [135, 136], although a quantitative analysis of samples obtained from randomized, placebo-controlled trial [51] suggests no difference in placental pathology between CMVIG-treated and untreated groups [89]. A large repeat clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of CMVIG administered to pregnant women with primary HCMV infection has recently been halted in the United States (NCT01376778), and detailed data on infant outcomes and placental disease will be forthcoming.

mAbs have also been explored as a therapeutic option, having higher potency and lower toxicity than polyclonal populations [137] and thus the potential to outperform CMVIG preparations. The gH-specific neutralizing mAb MSL-109 was tested in clinical trial for prevention of HCMV infection in stem cell transplant recipients as well for adjuvant therapy in HIV-infected patients with HCMV [138, 139], although it ultimately failed in both populations (possibly owing to development of a novel mechanism of resistance [140]). However, a clinical trial of RG7667, a combination of 2 neutralizing mAbs targeting distinct glycoprotein epitopes, found reduced viremia in a phase 2 trial of donor-positive, recipient-negative kidney transplant recipients [69].

CD8+ T-cell responses have been observed to be correlated with reduced HCMV disease and improved allograft function after transplantation [141–143] as well as with reduced HCMV-associated disease in HIV-infected populations [144]. Furthermore, in stem cell transplant recipients, the magnitude of the HCMV-specific CD4+/CD8+ T-cells predicted HCMV reactivation and long-term outcomes [145]. Studies disagree on the specificity of protective cytotoxic T lymphocytes, suggesting that IE1-specific cells [141, 142], pp65-specific cells [143], or both [145] are protective against HCMV disease. Furthermore, a breadth of CD8+ T-cell targets may be required to keep viral replication under control [146]. Other articles have expanded on these findings, reporting that both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells are required for prevention of HCMV disease in solid organ transplant recipients [104, 147].

The role of γδ T-cells, a lymphocyte population with properties of both innate and adaptive immune cells, in HCMV protective immunity remains under investigation [148]. The population of Vδ2− γδ T-cells has been observed to expand in response to HCMV infection in solid organ [149–152] and HSCT recipients [153, 154], pregnant women [155], and even fetuses in utero [156], most often reaching 5%–10% of the circulating T-cell pool. Interestingly, failure of this cell population to expand in donor-positive, recipient-negative kidney transplant populations is associated with recurrent disease and HCMV viremia [157]. These cells have been shown to be sufficient to prevent severe viral disease in a mouse model lacking conventional αβ T-cells or RAG knockout models [158, 159]. Intriguingly, however, this cell population may play a role in antibody-mediated transplant rejection, potentially providing a mechanistic link between HCMV infection and allograft rejection [160, 161].

Finally, the pool of NKG2C+ NK cells that are present before transplantation are correlated with improved transplant outcomes [108, 162]. However, this association is only anticipated to occur in the setting of a donor-positive, recipient-positive transplantation, because without prior HCMV infection there is no clonal expansion of NKG2C+ cells in the recipient [163]. It is hypothesized that NK cells may play a particularly important role in the setting of robust T-cell immunosuppression [163]. Furthermore, there are emerging data that infant NK cells may also play a role in attenuating the severity of congenital disease during infancy. In mice, researchers have observed that NK cells participate in reducing CMV-associated labyrinthitis and sensorineural hearing loss [164], but very little is known regarding the phenotype and function of these NK cells, or about how effective anti-HCMV NK cell immunity could be elicited to protect against transplant-associated and congenital HCMV disease.

THE PATH FORWARD

A wealth of data has been collected regarding the most appropriate targets and functions of immune factors against HCMV, which can be subsequently harnessed for designing the next generation of vaccines and/or therapeutic interventions [56]. Antibodies and CD8+ T-cells have the most clearly defined role in anti-HCMV protective immunity, with evidence for anti-HCMV function at every stage of the viral intrahost life cycle (Table 1). Consequently, many vaccines eliciting both humoral and cell-mediated immunity are currently in the development pipeline [166]. Interest in immune protection against this pathogen has increased exponentially, as evidenced by the sheer number of HCMV vaccines that have entered clinical evaluation [167]. In designing a clinical trial to test such next-generation vaccines, we propose 2 main considerations: an achievable clinical end point and appropriate intervention timing.

Table 1.

Evidence for Virus-Specific Immune Response Characteristics and Viral Immune Evasion Mechanisms in Control of Cytomegalovirus Acquisition, Replication, and Prevention of Diseasea

| Stage of Infection and Goals of Intervention | Antibodies | CD4+ T-Cells | CD8+ T-Cells | Innate Immune Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition stage | ||||

| Decreasing viral shedding | IgA [49] | HCMV specific [30] | pp65 Specific [41, 50], HCMV specific [30] | … |

| Preventing acquisition | Nonneutralizing IgG [58, 59] | … | Experimental or hypothesized CoP: HCMV specific [165] | … |

| Replication stage | ||||

| Reducing viremia and systemic dissemination | Mechanistic CoPs: neutralizing IgG [42, 67, 68], anti–gB AD2 [68, 78], anti–gH/gL-PC [69, 81], nonneutralizing IgG [59, 76] | HCMV specific [70, 90-95, 97], IL-7R+ [96] | HCMV specific [70, 100, 101], pp65 specific [99, 103], polyfunctional T-cells [104] | NKG2C+ [107, 108] |

| Blocking tissue-invasive replication | Experimental or hypothesized CoPs: gH/gL-PC [112], nonneutralizing IgG [76, 113] | … | … | Experimental or hypothesized CoP: dendritic NK [120, 121] |

| Disease stage | ||||

| Improving clinical long-term outcomes | CMVIG [42, 130-136], gH/gL-PC mAbs [69] | HCMV specific [104, 147] | HCMV specific [104, 147], IE1 specific [141, 142, 145], pp65 specific [143, 145] | NKG2C+ [108, 162] |

Abbreviations: CMVIG, cytomegalovirus hyperimmune globulin; CoP, correlate of protection; gB, glycoprotein B; gH/gL, glycoprotein heterodimer gH/gL; HCMV, human cytomegalovirus; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL-7R, interleukin 7 receptor; mAbs, monoclonal antibodies; PC, pentameric complex.

aListings within cells represent clinical CoPs, unless otherwise identified as experimental/hypothesized or mechanistic. Blank cells (ellipses) represent limited investigation or unknown findings.

We suggest that it is important to choose a clinical end point to maximize the probability of success rather than one that sets its sights on an unlikely goal. The gB/MF59 vaccine, the most efficacious HCMV vaccine to date, achieved a promising 50% protection against primary infection in seronegative women [53]. This statistic is encouragingly close to the estimated 50%–60% required for virus eradication through herd immunity [19, 20], but because natural immunity against HCMV is not protective against viral reinfection or reactivation, it is widely believed in the field that sterilizing immunity is unobtainable via vaccination [168].

This possibility should be certainly be examined by following up vaccine recipients to determine whether they can resist primary infection (and reinfection if they do succumb to primary infection). However, if the primary outcome of gB subunit immunization had been decreased salivary shedding of HCMV, reduced viremia, or improved birth outcomes, the measured vaccine efficacy might have been even higher. Similar concepts apply to the evaluation of success in transplant populations. Is prevention of transmission or viral reactivation the only criterion for success? Transplantation can involve the direct transmission of HCMV in a donor organ into an individual, which is not a natural route of infection and thus may circumvent some aspects of immunity. However, a reduction in viremia is associated with better outcomes in transplant recipients, and thus could be used to identify immune CoPs.

Furthermore, the timing of an intervention is of paramount importance [169]. There is abundant evidence that preexisting antibody can prevent HCMV acquisition, replication, and disease. However, the finding that CMVIG passive infusion after maternal primary infection was ineffective in reducing the incidence of congenital disease in phase 2 trial [85] has been perceived by many researchers as a limitation of antibody-mediated protection [166]. Likewise, the ASP0113 vaccine has been shown to reduce viremia when given before transplantation [103], but the failure of ASP0113 administered after transplantion to reduce viremia and HCMV end-organ disease in renal and HSCT recipients has been regarded as a shortcoming of the vaccine platform itself.

Although a great deal remains unknown regarding the CoPs against clinical end points of HCMV acquisition, replication, and pathogenesis, there is accumulating evidence and increasing optimism that a vaccine or therapeutic intervention can reduce the burden of disease. Furthermore, CoPs might have clinical utility beyond vaccine design, guiding treatment paradigms for populations at high risk of HCMV-associated disease. HCMV constitutes a challenging pathogen, with unparalleled techniques of immune evasion and an ability to superinfect in the setting of robust host immunity.

Nonetheless, perhaps we do not truly need to “outperform” all aspects of natural immunity [168] but instead should strategically target our intervention to mimic or enhance specific potentially protective immune responses (eg, antibodies against gB AD2). We hypothesize that if the field sets its sights on potentially obtainable end points, such as reducing viremia or systemic dissemination, and implements the intervention before the onset of viral replication, a vaccine or immunotherapeutic could be efficacious in reducing the burden of HCMV disease in neonates and transplant recipients.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant F30HD089577 to C. S. N.), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grants R21AI136556 to S. R. P.), National Institutes of Health; Wellcome Trust (grant WT/204870/Z/16/Z to M. B. R. and P. D. G.); Rosetrees Trust (grant A1601 to M. B. R. and P. D. G.); Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica-Regione Lombardia (grant 2015-0043 to D. L); UCL (Global Engagement Award to I. B.); and Sanofi Pasteur and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant R01AI051355 to P. D. G.).

Supplement sponsorship. This supplement was sponsored by NIAID and NICHD.

Disclaimer. The funders had no role in the decision to publish or preparation of this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Wellcome Trust, the Rosetrees Trust, or the Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica-Regione Lombardia.

Potential conflicts of interest. P. D. G.'s medical school received funds for his provisions of consulting services to Shire, Chimerix, Hookipa Pharma, and GlaxoSmithKline. S. R. P. provides consulting services to Pfizer, Merck, Moderna, and Sanofi for their preclinical human cytomegalovirus vaccine programs. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Swanson EC, Schleiss MR. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: new prospects for prevention and therapy. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013; 60:335–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manicklal S, Emery VC, Lazzarotto T, Boppana SB, Gupta RK. The “silent” global burden of congenital cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26:86–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Legendre C, Pascual M. Improving outcomes for solid-organ transplant recipients at risk from cytomegalovirus infection: late-onset disease and indirect consequences. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:732–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ljungman P, Hakki M, Boeckh M. Cytomegalovirus in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2011; 25:151–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med 2005; 202:673–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murphy E, Rigoutsos I, Shibuya T, Shenk TE. Reevaluation of human cytomegalovirus coding potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100:13585–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rigoutsos I, Novotny J, Huynh T, et al. In silico pattern-based analysis of the human cytomegalovirus genome. J Virol 2003; 77:4326–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mach M, Kropff B, Dal Monte P, Britt W. Complex formation by human cytomegalovirus glycoproteins M (gpUL100) and N (gpUL73). J Virol 2000; 74:11881–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Isaacson MK, Compton T. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B is required for virus entry and cell-to-cell spread but not for virion attachment, assembly, or egress. J Virol 2009; 83:3891–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bowman JJ, Lacayo JC, Burbelo P, Fischer ER, Cohen JI. Rhesus and human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein L are required for infection and cell-to-cell spread of virus but cannot complement each other. J Virol 2011; 85:2089–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vanarsdall AL, Johnson DC. Human cytomegalovirus entry into cells. Curr Opin Virol 2012; 2:37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hahn G, Revello MG, Patrone M, et al. Human cytomegalovirus UL131-128 genes are indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells and virus transfer to leukocytes. J Virol 2004; 78:10023–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang D, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:18153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Plotkin SA, Gilbert PB. Nomenclature for immune correlates of protection after vaccination. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1615–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, et al. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1275–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Plotkin SA. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2010; 17:1055–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Azevedo LS, Pierrotti LC, Abdala E, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2015; 70:515–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hyde TB, Schmid DS, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroconversion rates and risk factors: implications for congenital CMV. Rev Med Virol 2010; 20:311–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Colugnati FA, Staras SA, Dollard SC, Cannon MJ. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection among the general population and pregnant women in the United States. BMC Infect Dis 2007; 7:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Griffiths PD, McLean A, Emery VC. Encouraging prospects for immunisation against primary cytomegalovirus infection. Vaccine 2001; 19:1356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cannon MJ, Hyde TB, Schmid DS. Review of cytomegalovirus shedding in bodily fluids and relevance to congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 2011; 21:240–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schleiss MR. Acquisition of human cytomegalovirus infection in infants via breast milk: natural immunization or cause for concern? Rev Med Virol 2006; 16:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gantt S, Orem J, Krantz EM, et al. Prospective characterization of the risk factors for transmission and symptoms of primary human herpesvirus infections among Ugandan infants. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schoenfisch AL, Dollard SC, Amin M, et al. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) shedding is highly correlated with markers of immunosuppression in CMV-seropositive women. J Med Microbiol 2011; 60:768–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tu W, Chen S, Sharp M, et al. Persistent and selective deficiency of CD4+ T cell immunity to cytomegalovirus in immunocompetent young children. J Immunol 2004; 172:3260–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stowell JD, Mask K, Amin M, et al. Cross-sectional study of cytomegalovirus shedding and immunological markers among seropositive children and their mothers. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Amin MM, Bialek SR, Dollard SC, Wang C. Urinary cytomegalovirus shedding in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999–2004. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:587–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cannon MJ, Hyde TB, Schmid DS. Review of cytomegalovirus shedding in bodily fluids and relevance to congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 2011; 21:240–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gibson L, Barysauskas CM, McManus M, et al. Reduced frequencies of polyfunctional CMV-specific T cell responses in infants with congenital CMV infection. J Clin Immunol 2015; 35:289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen SF, Holmes TH, Slifer T, et al. Longitudinal kinetics of cytomegalovirus-specific T-cell immunity and viral replication in infants with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2016; 5:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stowell JD, Mask K, Amin M, et al. Cross-sectional study of cytomegalovirus shedding and immunological markers among seropositive children and their mothers. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang JB, Adler SP, Hempfling S, et al. Mucosal antibodies to human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B occur following both natural infection and immunization with human cytomegalovirus vaccines. J Infect Dis 1996; 174:387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nelson CS, Cruz DV, Su M, et al. Intrahost dynamics of human cytomegalovirus variants acquired by seronegative glycoprotein B vaccinees. J Virol 2018; 93:e01695–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Itell HL, Kaur A, Deere JD, Barry PA, Permar SR. Rhesus monkeys for a nonhuman primate model of cytomegalovirus infections. Curr Opin Virol 2017; 25:126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hansen SG, Strelow LI, Franchi DC, Anders DG, Wong SW. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of rhesus cytomegalovirus. J Virol 2003; 77:6620–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de Rijk EPC, Van Esch E. The macaque placenta—a mini-review. Toxicol Pathol 2008; 36:108–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yue Y, Barry PA. Rhesus cytomegalovirus a nonhuman primate model for the study of human cytomegalovirus. Adv Virus Res 2008; 72:207–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lockridge KM, Zhou SS, Kravitz RH, et al. Primate cytomegaloviruses encode and express an IL-10-like protein. Virology 2000; 268:272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Powers C, Früh K. Rhesus CMV: an emerging animal model for human CMV. Med Microbiol Immunol 2008; 197:109–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yue Y, Kaur A, Eberhardt MK, et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of DNA vaccines expressing rhesus cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B, phosphoprotein 65-2, and viral interleukin-10 in rhesus macaques. J Virol 2007; 81:1095–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abel K, Martinez J, Yue Y, et al. Vaccine-induced control of viral shedding following rhesus cytomegalovirus challenge in rhesus macaques. J Virol 2011; 85:2878–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nelson CS, Cruz DV, Tran D, et al. Preexisting antibodies can protect against congenital cytomegalovirus infection in monkeys. JCI Insight 2017; 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schleiss MR. Acquisition of human cytomegalovirus infection in infants via breast milk: natural immunization or cause for concern? Rev Med Virol 2006; 16:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peckham CS, Johnson C, Ades A, Pearl K, Chin KS. Early acquisition of cytomegalovirus infection. Arch Dis Child 1987; 62:780–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gantt S, Orem J, Krantz EM, et al. Prospective characterization of the risk factors for transmission and symptoms of primary human herpesvirus infections among Ugandan infants. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van der Strate BW, Harmsen MC, Schäfer P, et al. Viral load in breast milk correlates with transmission of human cytomegalovirus to preterm neonates, but lactoferrin concentrations do not. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001; 8:818–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kelly MS, Benjamin DK, Puopolo KM, et al. Postnatal cytomegalovirus infection and the risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169:e153785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hamprecht K, Maschmann J, Jahn G, Poets CF, Goelz R. Cytomegalovirus transmission to preterm infants during lactation. J Clin Virol 2008; 41:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stagno S, Reynolds DW, Pass RF, Alford CA. Breast milk and the risk of cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med 1980; 302:1073–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moylan DC, Pati SK, Ross SA, Fowler KB, Boppana SB, Sabbaj S. Breast milk human cytomegalovirus (CMV) viral load and the establishment of breast milk CMV-pp65-specific CD8 T cells in human CMV infected mothers. J Infect Dis 2017; 216:1176–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jackson SE, Mason GM, Wills MR. Human cytomegalovirus immunity and immune evasion. Virus Res 2011; 157:151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Myerson D, Hackman RC, Nelson JA, Ward DC, McDougall JK. Widespread presence of histologically occult cytomegalovirus. Hum Pathol 1984; 15:430–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pass RF, Zhang C, Evans A, et al. Vaccine prevention of maternal cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1191–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mayer BT, Krantz EM, Swan D, et al. Transient oral human cytomegalovirus infections indicate inefficient viral spread from very few initially infected cells. J Virol 2017; 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bernstein DI, Munoz FM, Callahan ST, et al. Safety and efficacy of a cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B (gB) vaccine in adolescent girls: a randomized clinical trial. Vaccine 2016; 34:313–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nelson CS, Herold BC, Permar SR. A new era in cytomegalovirus vaccinology: considerations for rational design of next-generation vaccines to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus infection. NPJ Vaccines 2018; 3:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pass RF. Development and evidence for efficacy of CMV glycoprotein B vaccine with MF59 adjuvant. J Clin Virol 2009; 46(suppl 4):S73–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nelson CS, Huffman T, Jenks JA, et al. HCMV glycoprotein B subunit vaccine efficacy mediated by nonneutralizing antibody effector functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:6267–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Baraniak I, Kropff B, Ambrose L, et al. Protection from cytomegalovirus viremia following glycoprotein B vaccination is not dependent on neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:6273–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ljungman P, Griffiths P, Paya C. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34:1094–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Weisblum Y, Panet A, Haimov-Kochman R, Wolf DG. Models of vertical cytomegalovirus (CMV) transmission and pathogenesis. Semin Immunopathol 2014; 36:615–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Revello MG, Gerna G. Pathogenesis and prenatal diagnosis of human cytomegalovirus infection. J Clin Virol 2004; 29:71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Itell HL, Nelson CS, Martinez DR, Permar SR. Maternal immune correlates of protection against placental transmission of cytomegalovirus. Placenta 2017; 60(suppl 1):73–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Delorme-Axford E, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB. The placenta as a barrier to viral infections. Annu Rev Virol 2014; 1:133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hassan-Walker AF, Kidd IM, Sabin C, Sweny P, Griffiths PD, Emery VC. Quantity of human cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNAemia as a risk factor for CMV disease in renal allograft recipients: relationship with donor/recipient CMV serostatus, receipt of augmented methylprednisolone and antithymocyte globulin (ATG). J Med Virol 1999; 58:182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Harrison CJ, Myers MG. Relation of maternal CMV viremia and antibody response to the rate of congenital infection and intrauterine growth retardation. J Med Virol 1990; 31:222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Boppana SB, Britt WJ. Antiviral antibody responses and intrauterine transmission after primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection. J Infect Dis 1995; 171:1115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bialas KM, Westreich D, Cisneros de la Rosa E, et al. Maternal antibody responses and nonprimary congenital cytomegalovirus infection of HIV-1-exposed infants. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:1916–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ishida JH, Patel A, Mehta AK, et al. Phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of RG7667, a combination monoclonal antibody, for prevention of cytomegalovirus infection in high-risk kidney transplant recipients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lilleri D, Zelini P, Fornara C, et al. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-specific T cell but not neutralizing or IgG binding antibody responses to glycoprotein complexes gB, gHgLgO, and pUL128L correlate with protection against high HCMV viral load reactivation in solid-organ transplant recipients. J Med Virol 2018; 90:1620–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. Rational design of vaccines to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2011; 1:a007278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Klasse PJ, Sattentau QJ. Occupancy and mechanism in antibody-mediated neutralization of animal viruses. J Gen Virol 2002; 83:2091–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Murrell I, Bedford C, Ladell K, et al. The pentameric complex drives immunologically covert cell-cell transmission of wild-type human cytomegalovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114:6104–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ourahmane A, Cui X, He L, et al. Inclusion of antibodies to cell culture media preserves the integrity of genes encoding RL13 and the pentameric complex components during fibroblast passage of human cytomegalovirus. Viruses 2019; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jacob CL, Lamorte L, Sepulveda E, Lorenz IC, Gauthier A, Franti M. Neutralizing antibodies are unable to inhibit direct viral cell-to-cell spread of human cytomegalovirus. Virology 2013; 444:140–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bootz A, Karbach A, Spindler J, et al. Protective capacity of neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies against glycoprotein B of cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13:e1006601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Griffiths PD, Stanton A, McCarrell E, et al. Cytomegalovirus glycoprotein-B vaccine with MF59 adjuvant in transplant recipients: a phase 2 randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 377:1256–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Baraniak I, Kropff B, McLean GR, et al. Epitope-specific humoral responses to human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein-B vaccine with MF59: anti-AD2 levels correlate with protection from viremia. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:1907–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Grosjean J, Trapes L, Hantz S, et al. Human cytomegalovirus quantification in toddlers saliva from day care centers and emergency unit: a feasibility study. J Clin Virol 2014; 61:371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Grosjean J, Hantz S, Cotin S, et al. Direct genotyping of cytomegalovirus envelope glycoproteins from toddler's saliva samples. J Clin Virol 2009; 46(suppl 4):S43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lilleri D, Kabanova A, Revello MG, et al. Fetal human cytomegalovirus transmission correlates with delayed maternal antibodies to gH/gL/pUL128-130-131 complex during primary infection. PLoS One 2013; 8:e59863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Vanarsdall AL, Chin AL, Liu J, et al. HCMV trimer- and pentamer-specific antibodies synergize for virus neutralization but do not correlate with congenital transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019; 116:3728–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Iglesias-Escudero M, Moro-García MA, Marcos-Fernández R, et al. Levels of anti-CMV antibodies are modulated by the frequency and intensity of virus reactivations in kidney transplant patients. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0194789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fornara C, Furione M, Lilleri D, et al. Primary human cytomegalovirus infections: kinetics of ELISA-IgG and neutralizing antibody in pauci/asymptomatic pregnant women vs symptomatic non-pregnant subjects. J Clin Virol 2015; 64:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Revello MG, Lazzarotto T, Guerra B, et al. ; CHIP Study Group A randomized trial of hyperimmune globulin to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1316–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kagan KO, Enders M, Schampera MS, et al. Prevention of maternal-fetal transmission of cytomegalovirus after primary maternal infection in the first trimester by biweekly hyperimmunoglobulin administration. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019; 53:383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Planitzer CB, Saemann MD, Gajek H, Farcet MR, Kreil TR. Cytomegalovirus neutralization by hyperimmune and standard intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Transplantation 2011; 92:267–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Maidji E, McDonagh S, Genbacev O, Tabata T, Pereira L. Maternal antibodies enhance or prevent cytomegalovirus infection in the placenta by neonatal Fc receptor-mediated transcytosis. Am J Pathol 2006; 168:1210–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gabrielli L, Bonasoni MP, Foschini MP, et al. Histological analysis of term placentas from hyperimmune globulin-treated and untreated mothers with primary cytomegalovirus infection. Fetal Diagn Ther 2019; 45:111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gamadia LE, Rentenaar RJ, van Lier RA, ten Berge IJ. Properties of CD4+ T cells in human cytomegalovirus infection. Hum Immunol 2004; 65:486–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Gerna G, Lilleri D, Fornara C, et al. Differential kinetics of human cytomegalovirus load and antibody responses in primary infection of the immunocompetent and immunocompromised host. J Gen Virol 2015; 96:360–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Widmann T, Sester U, Gärtner BC, et al. Levels of CMV specific CD4 T cells are dynamic and correlate with CMV viremia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. PLoS One 2008; 3:e3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lilleri D, Fornara C, Furione M, Zavattoni M, Revello MG, Gerna G. Development of human cytomegalovirus-specific T cell immunity during primary infection of pregnant women and its correlation with virus transmission to the fetus. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:1062–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Revello MG, Lilleri D, Zavattoni M, et al. Lymphoproliferative response in primary human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection is delayed in HCMV transmitter mothers. J Infect Dis 2006; 193:269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Saldan A, Forner G, Mengoli C, Gussetti N, Palù G, Abate D. Strong cell-mediated immune response to human cytomegalovirus is associated with increased risk of fetal infection in primarily infected pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Mele F, Fornara C, Jarrossay D, et al. Phenotype and specificity of T cells in primary human cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy: IL-7Rpos long-term memory phenotype is associated with protection from vertical transmission. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0187731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bialas KM, Tanaka T, Tran D, et al. Maternal CD4+ T cells protect against severe congenital cytomegalovirus disease in a novel nonhuman primate model of placental cytomegalovirus transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:13645–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Fan Q, Nelson CS, Bialas KM, et al. Plasmablast response to primary rhesus cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in a monkey model of congenital CMV transmission. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2017; 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mattes FM, Vargas A, Kopycinski J, et al. Functional impairment of cytomegalovirus specific CD8 T cells predicts high-level replication after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 2008; 8:990–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Aubert G, Hassan-Walker AF, Madrigal JA, et al. Cytomegalovirus-specific cellular immune responses and viremia in recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplants. J Infect Dis 2001; 184:955–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Sacre K, Carcelain G, Cassoux N, et al. Repertoire, diversity, and differentiation of specific CD8 T cells are associated with immune protection against human cytomegalovirus disease. J Exp Med 2005; 201:1999–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Polić B, Hengel H, Krmpotić A, et al. Hierarchical and redundant lymphocyte subset control precludes cytomegalovirus replication during latent infection. J Exp Med 1998; 188:1047–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Boeckh M, Wilck MB, et al. A novel therapeutic cytomegalovirus DNA vaccine in allogeneic haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:290–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Snyder LD, Chan C, Kwon D, et al. Polyfunctional T-cell signatures to predict protection from cytomegalovirus after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193:78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sturgill ER, Malouli D, Hansen SG, et al. Natural killer cell evasion is essential for infection by rhesus cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog 2016; 12:e1005868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. O'Sullivan TE, Sun JC, Lanier LL. Natural killer cell memory. Immunity 2015; 43:634–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Foley B, Cooley S, Verneris MR, et al. Human cytomegalovirus (CMV)-induced memory-like NKG2C+ NK cells are transplantable and expand in vivo in response to recipient CMV antigen. J Immunol 2012; 189:5082–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Redondo-Pachón D, Crespo M, Yélamos J, et al. Adaptive NKG2C+ NK cell response and the risk of cytomegalovirus infection in kidney transplant recipients. J Immunol 2017; 198:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Della Chiesa M, Falco M, Bertaina A, et al. Human cytomegalovirus infection promotes rapid maturation of NK cells expressing activating killer Ig-like receptor in patients transplanted with NKG2C−/− umbilical cord blood. J Immunol 2014; 192:1471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Sun JC, Lanier LL. Is there natural killer cell memory and can it be harnessed by vaccination? NK cell memory and immunization strategies against infectious diseases and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Silva MC, Schroer J, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus cell-to-cell spread in the absence of an essential assembly protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:2081–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Gerna G, Percivalle E, Perez L, Lanzavecchia A, Lilleri D. Monoclonal antibodies to different components of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) pentamer gH/gL/pUL128L and trimer gH/gL/gO as well as antibodies elicited during primary HCMV infection prevent epithelial cell syncytium formation. J Virol 2016; 90:6216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Forthal DN, Phan T, Landucci G. Antibody inhibition of cytomegalovirus: the role of natural killer and macrophage effector cells. Transpl Infect Dis 2001; 3(suppl 2):31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Gordon CL, Miron M, Thome JJ, et al. Tissue reservoirs of antiviral T cell immunity in persistent human CMV infection. J Exp Med 2017; 214:651–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Masopust D, Vezys V, Marzo AL, Lefrançois L. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science 2001; 291:2413–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Masopust D, Vezys V, Usherwood EJ, et al. Activated primary and memory CD8 T cells migrate to nonlymphoid tissues regardless of site of activation or tissue of origin. J Immunol 2004; 172:4875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Bingaman AW, Patke DS, Mane VR, et al. Novel phenotypes and migratory properties distinguish memory CD4 T cell subsets in lymphoid and lung tissue. Eur J Immunol 2005; 35:3173–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Wakim LM, Woodward-Davis A, Bevan MJ. Memory T cells persisting within the brain after local infection show functional adaptations to their tissue of residence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:17872–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Ganusov VV, De Boer RJ. Do most lymphocytes in humans really reside in the gut? Trends Immunol 2007; 28:514–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Björkström NK, Ljunggren HG, Michaëlsson J. Emerging insights into natural killer cells in human peripheral tissues. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16:310–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Whitelaw PF, Croy BA. Granulated lymphocytes of pregnancy. Placenta 1996; 17:533–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Le Bouteiller P. Human decidual NK cells: unique and tightly regulated effector functions in healthy and pathogen-infected pregnancies. Front Immunol 2013; 4:404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Siewiera J, El Costa H, Tabiasco J, et al. Human cytomegalovirus infection elicits new decidual natural killer cell effector functions. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9:e1003257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Crespo AC, Strominger JL, Tilburgs T. Expression of KIR2DS1 by decidual natural killer cells increases their ability to control placental HCMV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113:15072–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Carlin LE, Hemann EA, Zacharias ZR, Heusel JW, Legge KL. Natural killer cell recruitment to the lung during influenza A virus infection is dependent on CXCR3, CCR5, and virus exposure dose. Front Immunol 2018; 9:781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Jegaskanda S, Weinfurter JT, Friedrich TC, Kent SJ. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity is associated with control of pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection of macaques. J Virol 2013; 87:5512–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Zhou G, Juang SW, Kane KP. NK cells exacerbate the pathology of influenza virus infection in mice. Eur J Immunol 2013; 43:929–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Dunn C, Brunetto M, Reynolds G, et al. Cytokines induced during chronic hepatitis B virus infection promote a pathway for NK cell-mediated liver damage. J Exp Med 2007; 204:667–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Khakoo SI, Thio CL, Martin MP, et al. HLA and NK cell inhibitory receptor genes in resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Science 2004; 305:872–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Snydman DR, Werner BG, Heinze-Lacey B, et al. Use of cytomegalovirus immune globulin to prevent cytomegalovirus disease in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1049–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Fisher RA, Kistler KD, Ulsh P, Bergman GE, Morris J. The association between cytomegalovirus immune globulin and long-term recipient and graft survival following liver transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2012; 14:121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Snydman DR, Kistler KD, Ulsh P, Bergman GE, Vensak J, Morris J. The impact of CMV prevention on long-term recipient and graft survival in heart transplant recipients: analysis of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) database. Clin Transplant 2011; 25:E455–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Bonaros N, Mayer B, Schachner T, Laufer G, Kocher A. CMV-hyperimmune globulin for preventing cytomegalovirus infection and disease in solid organ transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Clin Transplant 2008; 22:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Visentin S, Manara R, Milanese L, et al. Early primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy: maternal hyperimmunoglobulin therapy improves outcomes among infants at 1 year of age. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]