Abstract

Due to higher vulnerability and immunogenicity of extended criteria donor (ECD) organs used for organ transplantation (Tx), the discovery of new treatment strategies, involving tissue allorecognition pathways, is important. The implementation of machine perfusion (MP) led to improved estimation of the organ quality and introduced the possibility to achieve graft reconditioning prior to Tx. A significant number of experimental and clinical trials demonstrated increasing support for MP as a promising method of ECD organ preservation compared to classical static cold storage. MP reduced ischemia–reperfusion injury resulting in the protection from inadequate activation of innate immunity. However, there are no general agreements on MP protocols, and clinical application is limited. The objective of this comprehensive review is to summarize literature on immunological effects of MP of ECD organs based on experimental studies and clinical trials.

Keywords: extended criteria donors, immunological rejection, machine perfusion, marginal organs, transplantation

Introduction

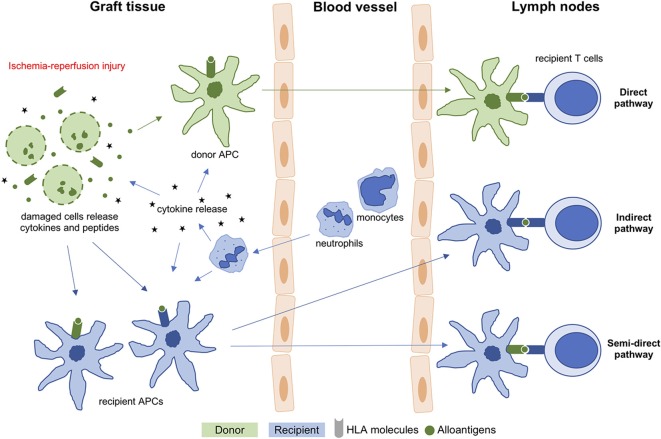

The remarkable evolution of solid organ transplantation (Tx) has led to improved overall outcomes for patients with terminal organ dysfunction. However, ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) in combination with early immune activation remains a significant challenge limiting the potential of this therapy (1, 2). IRI depends on several factors, including primary condition of the graft and length of cold and warm ischemia time (CIT and WIT). It additionally determines the extent of the inflammatory response and increases immunogenicity and the degree of microcirculatory perfusion failure during reperfusion resulting in early allograft dysfunction or primary non-function (3, 4). As a link between the degree of IRI and activation of innate immunity (5) has been proposed, the discovery of new treatment strategies including tissue allorecognition pathways (Figure 1) has gained importance, especially in the era of extended criteria donor (ECD) organ Tx. The direct pathway starts with recipient CD4 and CD8 T cells recognizing endogenous alloantigens presented by donor human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules on the surface of donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs) after their migration from the graft to the recipient's lymph nodes. This process is initiated by the massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from damaged cells during IRI (4). On the other hand, the indirect allorecognition relies on recipient-derived APCs, which ingest, process, and present alloantigens (typically HLA antigens) in the context of recipient HLA, for self-restricted recognition by recipient T cells (6, 7). In the semi-direct pathway, recipient APCs acquire donor HLA molecules that present alloantigens directly to recipient T cells (8). Direct allorecognition alone can result in acute rejection, even without indirect mechanisms. Furthermore, depletion of donor immune cells from an organ prior to Tx may prevent rejection (9).

Figure 1.

T cell allorecognition pathways in organ transplantation. APC, antigen-presenting cell; HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

For more than 50 years, static cold storage (SCS) was the gold standard method for organ preservation until the interest in the concept of organ machine perfusion (MP) was renewed (10). To date, a significant number of experimental and clinical trials were published demonstrating increasing support of MP as a more physiologic method of solid organ preservation compared to SCS (11–15).

MP is a promising tool to reduce the gap between organ demand and supply that is resulting in a dramatic prolongation in waiting times and associated with increased morbidity and mortality for patients on the waiting list for Tx (16). In an effort to counter this trend, organ allografts that would have previously been deemed unsuitable are nowadays more frequently used for Tx (12) including donation after circulatory death (DCD) and ECD (aged ≥ 60 years or aged 50–59 years with vascular comorbidities) organs (12, 17, 18). Older donor organs have higher immunogenicity, mediated by poorer monocyte clearance of damaged necrotic cells, and therefore recipients may require a more intense immunosuppression in the early period after Tx (19–22). Knowing about the ECD grafts' increased risk for poor function or failure (23–25), implementation of new storage techniques, such as MP, paved the way for better characterization of organ quality and the possibility for graft reconditioning before Tx to improve organ vulnerability and immunogenicity (10, 26). MP reduced IRI in experimental and clinical models of ECD organ Tx resulting in protection from inadequate activation of innate immunity (1, 27–36).

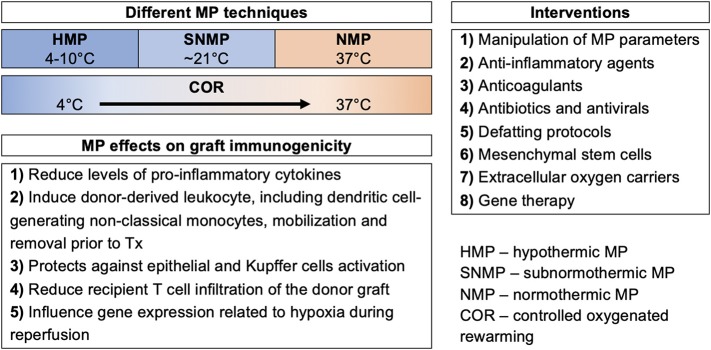

Figure 2 summarizes frequently described MP settings including the underlying mechanisms. Briefly, hypothermic MP (HMP, 4–10°C) is based on the concept that oxidative energy production by mitochondrial electron transport is sustained at reduced rates by keeping low temperatures (10). In contrast, normothermic MP (NMP, 37°C) aims to provide an approximately near physiological environment for organs ex vivo (37). Subnormothermic MP (SNMP, ~21°C) is a halfway approach between HMP and NMP, while controlled oxygenated rewarming (COR) is a concept to rescue cold-stored marginal grafts by gentle oxygenated warming up prior to blood reperfusion (38, 39).

Figure 2.

Different machine perfusion strategies of extended criteria donor organs for protection against activation of innate immunity.

Currently, there are no general agreements on MP protocols, and clinical application is limited due to the lack of randomized clinical trials comparing the different MP strategies. The objective of this comprehensive review is to summarize literature on MP of ECD organs and discuss arising immunological aspects based on experimental studies and clinical trials.

Machine Perfusion of Extended Criteria Donor Kidney Grafts

It seems that MP for Tx of ECD kidneys is associated with decreased IRI resulting in improved outcome compared to SCS (Table 1). Whereas most studies on MP in ECD kidneys reported positive effects on the graft, only a few studies reported inconclusive results (40, 48).

Table 1.

Experimental and clinical studies of machine perfusion of extended criteria donor kidney grafts.

| Studies | Model | Primary graft condition, N | MP time | Results and immunological aspects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANIMAL STUDIES | ||||

| Treckmann et al. (40) | Porcine HMP vs. retrograde oxygen persufflation vs. SCS with autoTx | DCD; N = 7/group WIT: 1 h |

4 h | Malondialdehyde was dramatically increased in the MP kidneys on day 7, whereas levels in the other two groups were near normal values. The MP kidneys exhibited the most striking histological changes |

| Vaziri et al. (27) | Porcine HMP with Viaspan UW vs. KPS-1 vs. SCS without Tx | DCD; N = 7/group WIT: 1 h |

24 h | HMP demonstrated superiority over SCS independently of perfusion solution. Results suggested significant benefits on graft outcome, particularly evident on the chronic effects of IRI with a protection against chronic immune response, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy |

| Thuillier et al. (41) | Porcine HMP ± hyperoxia with Tx | DCD; N = 4/group WIT: 1 h |

22 h | HMP with oxygen showed signs of higher quality and better function. Furthermore, the typical lesions of chronic graft loss were reduced, confirming improved ability to recover from the IRI |

| Stone et al. (1) | Porcine NMP without Tx |

N = 10 CIT: 2 h |

6 h | NMP initiated an inflammatory cytokine storm (especially IL-6, IFN-γ, and CXCL-8) and induced donor-derived leukocyte mobilization and removal prior to kidney Tx |

| Kasil et al. (42) | Porcine HMP ± M101 (2 g/L) ± hyperoxia with autoTx | DCD; N = 6/group WIT: 1 h |

23 h | The M101 improved the HMP effect upon kidney recovery and late graft outcome. The infiltration of mast-cell leukocyte was nearly absent, leading to reduced fibrosis level in the kidney. Excess supply of oxygen has not improved the results |

| HUMAN STUDIES | ||||

| Reznik et al. (43) | HMP vs. SCS with Tx | Uncontrolled DCD; N = 17 vs. 21 WIT: 42.7 ± 1.6 |

12 h | A considerable number of complications and the negative effects, including acute rejection, correlated with the SCS group of kidneys |

| Treckmann et al. (44) | HMP vs. SCS with Tx | ECD; N = 91/group Median age: 66 y CIT: 13 h |

n.d. | HMP preservation clearly reduced the risk of DGF and improved 1-year graft survival and function in ECD kidneys, while acute rejection rate was similar (17 vs. 16%, respectively) |

| Tozzi et al. (32) | HMP vs. SCS with Tx | Nyberg Score class C or D (donors mean age 67 ± 7 years); N = 10 vs. 13 CIT: 70 ± 25 min |

12 ± 4 h | The levels of early inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-1β) were decreased in HMP group in perfusion and preservation liquid; however, there was a non-significant difference comparing sICAM-1 |

| Nicholson et al. (45) | NMP vs. SCS with Tx | ECD; N = 10 vs. 47 CIT: ~11 h |

63 ± 16 min | The incidence of acute rejection was similar in both groups (27.7 vs. 23.4%), while the delayed graft function rate was significantly reduced in the NMP group (5.6 vs. 36.2%) |

| Wszola et al. (46) | HMP vs. SCS | ECD vs. standard criteria donors; N = 62 | 24 h | MP influenced gene expression related to hypoxia during reperfusion and may improve the long-term results of kidney Tx |

| Wang et al. (47) | HMP vs. SCS with Tx | DCD and ECD; N = 24/group | 5.86 ± 2.8 h | HMP reduced the incidence of DGF in DCD kidneys, and this effect is greater for ECD kidneys. Acute rejection rate was non-significantly different (4.1 vs. 8.3%, respectively) |

| Gallinat et al. (48) | End-ischemic HMP vs. SCS alone with Tx | ECD; N = 43/group Mean age: 66 vs. 67 years CIT: 13.4 vs. 12.1 years |

1.6–12.8 h | PNF and DGF were 0 vs. 9.3% and 11.6 vs. 20.9%. There was no statistically significant difference in 1-year graft survival, while rejection rate within 3 months post Tx was significantly higher in the end-ischemic HMP group (38.5 vs. 10%, respectively) |

| Weissenbacher et al. (49) | NMP without Tx | DCD and DBD; N = 11 WIT: 16.2 ± 10 CIT: ~35 h |

24 h | Demonstrated ability to maintain the condition of donor kidneys of ECD quality for long enough to carry out viability assessment and increase the feasibility to exploit this important source of donor organs |

| Ruiz-Hernández et al. (50) | Partial vs. total HMP with Tx | ECD; N = 119 vs. 74 Median age: 76.9 vs. 69.9 years CIT: 18.4 vs. 16.3 years |

>4 h | There is a trend that complete HMP reduces the risk of DGF and improves 1-year graft survival in ECD kidneys |

| Savoye et al. (51) | HMP vs. SCS with Tx | ECD; N = 801 vs. 3,515 Mean age: 63.9 vs. 62.7 years CIT: 16.9 vs. 17.4 h |

n.d. | Results confirmed the reduction in DGF occurrence among ECD kidneys preserved by HMP |

CIT, cold ischemia time; CXCL, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; DGF, delayed graft function; ECD, extended criteria donor; DCD, donation after circulatory death; HMP, hypothermic MP; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IRI, ischemia–reperfusion injury; MP, machine perfusion; NMP, normothermic MP; SCS, static cold storage; sICAM, soluble intracellular adhesion molecule; Tx, transplantation; WIT, warm ischemia time; UW, University of Wisconsin solution; PNF, primary graft nonfunction; DBD, donor after brain death.

Hypothermic Machine Perfusion Techniques

A DCD porcine kidney HMP model demonstrated improved graft outcome (27, 41, 42), particularly concerning the chronic effects of IRI by protecting against chronic immune response by reducing the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (27). Epithelial to mesenchymal transition plays an important role in the genesis of fibroblasts in the course of interstitial fibrosis (27, 52). Furthermore, oxygenated HMP showed superior outcome rates compared to non-oxygenated HMP (41). The significantly reduced occurrence of typical signs for chronic graft loss, like chronic inflammation or interstitial fibrosis, confirmed an improvement in recovery from IRI (41). Lately, the use of an extracellular oxygen transporter was investigated. M101 (hemoglobin of the marine worm) was associated with improved effects of HMP upon recovery and late graft outcome, shown by the nearly absent infiltration of mast cells resulting in reduced levels of fibrosis in the kidney (42). Extracellular oxygen carriers may logistically, rheologically, and immunologically be superior to packed red blood cells, but need further investigation. Studies on human DCD and ECD kidneys supported the superiority of HMP over SCS (32, 43, 45, 46). Reznik et al. (43) found a considerably lower number of complications and negative effects, like acute rejection, correlated with HMP kidneys retrieved from DCD donors. Another study in ECD kidneys (Nyberg Score class C or D) demonstrated an association of HMP with lower levels of early inflammatory cytokines [tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-2, and IL-1β] in perfusion solution compared to SCS (32). HMP also affected the expression of hypoxia-related genes [i.e., hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α] (46). This may limit interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, improving long-term outcomes in kidney Tx. ECD kidneys profited most by application of HMP (46).

Normothermic Machine Perfusion Techniques

In a pig study, reduced graft immunogenicity was achieved by initiating an inflammatory cytokine storm [especially IL-6, interferon[108mmQ11 (IFN)-γ, and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)-8], leading to a donor-derived leukocyte mobilization and removal prior to kidney Tx (1). The authors proposed that migration of donor leukocytes in conjunction with the secretion of an IL-6, IFN-γ, and CXCL-8 storm leads to direct allorecognition and activates the recipient immune response following Tx (1). Short-term NMP of cold-stored human ECD kidneys did not reduce the incidence of acute rejection, while the rate of delayed graft function improved significantly (5.6 vs. 36.2%) (45). More recently, Weissenbacher et al. (49) was able to maintain the quality of ECD kidneys for up to 24 h, hence buying time for viability assessment, improving the feasibility to exploit this important source of donor organs using the NMP technique.

Although the primary results are encouraging, more research focusing on the reduction of immunogenicity of ECD organs is needed.

Machine Perfusion of Extended Criteria Donor Liver Grafts

Currently, there is no general consensus on the standardized pretreatment of ECD livers in order to improve Tx outcomes (53). Experimental and clinical studies of MP of ECD livers are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental and clinical studies of machine perfusion of extended criteria donor liver grafts.

| Studies | Model | Primary graft condition, N | MP time | Results and immunological aspects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANIMAL STUDIES | ||||

| Lee et al. (54) | Rats HMP vs. SCS followed by 1 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N = n.d. WIT: 30 min |

10 h | HMP for 10 h improved both function and microcirculation while reducing cellular damage of liver tissue when compared with SCS |

| Lauschke et al. (55) | Rats HMP with HTK vs. Belzer's solution vs. SCS followed by 45 min machine reperfusion | DCD; N ≥ 5/group WIT: 1 h |

24 h | HLA class II antigen expression was detected on post-sinusoidal venular endothelium after SCS of DCD livers, while the antigen was almost absent or markedly reduced after HMP with HTK or Belzer's solution, respectively |

| Lee et al. (56) | Rats HMP vs. SCS with Tx | DCD; N = 7/group WIT: 30 min |

5 h | HMP improved survival and reduced cellular damage of liver tissue that has experienced 30 min of WIT when compared with SCS tissues |

| Bessems et al. (57) | Rats HMP with Polysol or UW-G vs. SCS followed by 1 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N = 6/group WIT: 30 min |

24 h | 24 h HMP of DCD rat livers using the newly developed preservation solution Polysol results in less hepatocellular damage and better liver function compared to SCS in UW or HMP using UW-G |

| Manekeller et al. (58) | Rats HMP vs. SCS followed by 2 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N ≥ 5/group WIT: 30 min CIT: 16 |

0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h | 1 h of post-conditioning after a long time (16 h) of SCS organs improved the viability and sustainability. The significantly higher ATP content and the lack of apoptotic signs in the tissue were observed |

| Nagrath et al. (59) | Rats NMP ± defatting agent cocktail without Tx | Steatotic livers, N = 7 vs. 5 | 3 h | Perfusate supplementation with defatting agents significantly reduced the intracellular fat content of perfused livers within a few hours |

| Olschewski et al. (60) | Rats HMP vs. SNMP vs. SCS without Tx |

DCD; N = 5/group WIT: 1 h |

6 h | In contrast to preservation at 4 or 12°C MP at 21°C has a beneficial positive effect on the initial organ function, structural integrity of the sinusoidal endothelium, and hepatocellular damage |

| Stegemann et al. (61, 62) | Rats HMP with different perfusion solutions vs. gaseous oxygen persufflation vs. SCS without Tx | DCD; N = 6/group WIT: 30 min |

18 h | The use of Custodiol-N solution led to a significantly decreased release of ALT or LDH during HMP and reperfusion compared with HTK solution and reduced the level of apoptosis. The use of gaseous oxygen persufflation improved the tissue integrity and functional recovery of predamaged livers |

| Jamieson et al. (63) | Porcine NMP without Tx | Steatotic and normal livers, N = 3 vs. 5 WIT: 16 ± 4 min CIT: 76 ± 11 min |

48 h | Steatotic livers can be successfully preserved using NMP for prolonged periods, and NMP facilitates a reduction in hepatic steatosis |

| Ferrigno et al. (30) | Rats SNMP vs. SCS followed by 2 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N = 5/group WIT: 30 min |

6 h | MP preservation at 20°C improves cellular survival reducing the mitochondrial function in livers obtained from DCDs as compared with SCS |

| Gringeri et al. (31) | Porcine SNMP vs. SCS followed by 2 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N = 5/group WIT: 1 h |

6 h | The SNMP group showed better histopathologic results with significantly less hepatic damage compared with SCS |

| Schlegel et al. (29) | Rats HOPE vs. SCS with Tx | DCD; N = 20/group WIT: 30 min CIT: 4 h |

1 h | HOPE treatment significantly decreased IRI of hepatocytes by reducing the activation of Kupffer cells and endothelial cells. Moreover, HOPE-treated DCD livers were protected from activation of the innate immunity according to a decreased IRI |

| Schlegel et al. (64) | Porcine HMP with different parameters vs. SCS without Tx | DCD; N = 8/group WIT: 1 h CIT: 6 h |

1 h | HOPE protected from mitochondrial and nuclear IRI by downregulation of the mitochondrial activity before reperfusion. Cold perfusion itself, under low-pressure conditions, prevented endothelial damage independently of oxygen |

| Izamis et al. (65) | Rats NMP with Tx | WIT: 0 vs. 1 h N = 11 vs. 7 |

5 h | MP suppressed lipid oxidation, likely due to the high insulin levels. Perfused livers did not consume all the available oxygen and were hypoxic independent of ischemic injury, suggesting that enhanced microcirculation via vasodilators and anti-thrombolytics might be an effective approach at optimizing the delivery of oxygen to hepatocytes |

| Minor et al. (38) | Porcine COR vs. HMP vs. SNMP vs. SCS | ECD; N = 6/group CIT: 18 h |

1.5 h | COR significantly reduced cellular enzyme loss, gene expression and perfusate activities of TNF-α, radical mediated lipid peroxidation, and increase of portal vascular perfusion resistance upon reperfusion, while HMP or SNMP were less protective |

| Schlegel et al. (28) | Rats HOPE vs. deoxygenated MP with heterogenic Tx ± immunosuppression | CIT: 30 min | 1 h | Study demonstrated that allograft treatment by HOPE not only protects against preservation injury but also impressively downregulates the immune system, blunting the alloimmune response |

| Bae et al. (33) | Rats HMP with KPS-1 vs. VAS ± VitE vs. SCS without Tx |

DCD; N = 5/group WIT: 30 min |

8 h | VAS perfusion solution was superior compared with KPS-1, and supplementation of VAS with VitE reduced not only the level of ALT but also levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1) in graft tissue and caspase 3/7 in the circulation |

| Knaak et al. (39) | Porcine SNMP without Tx | DCD; N = 5 WIT: 45 min CIT: 4 h |

6 h | SNMP minimized cold ischemic injury and allowed to assess ECD liver grafts prior to Tx |

| Nassar et al. (66) | Porcine NMP ± vasodilators (prostacyclin or adenosine) without Tx |

DCD; N = 5/group WIT: 60 min |

10 h | Livers perfused with the addition of prostacyclin showed a significantly higher outcome over those perfused by adding adenosine or without vasodilators, indicating the necessity of potent, efficient vasodilation in order to achieve effective preservation of DCD livers during NMP |

| Nassar et al. (67) | Porcine NMP vs. SNMP vs. SCS followed by 24 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N = 5/group WIT: 60 min |

10 h | NMP was able to recover DCD livers showing superior hepatocellular integrity, biliary function, and microcirculation compared to SNMP and SCS |

| Ferrigno et al. (68) | Rats SNMP vs. SCS ± oxygenated washout Rats SNMP vs. SCS Both followed by 2 h machine reperfusion |

DCD; N = 7/group WIT: 30 min Steatotic livers; N = 7/group |

6 h | The use of oxygenated washout before SCS reversed liver injury in DCD organs, improving the ATP/ADP ratio; the use of MP did not otherwise prevent liver damage Using dynamic MP, a significantly lower hepatic damage and an increase in bile flow and in the ATP/ADP ratio were found compared with those of the SCS group |

| Chai et al. (69) | Rats HMP with UW ± metformin (0.165 mg/L) without Tx | Young and aged livers; N = 6/group | 12 h | The addition of metformin to the UW preservation solution for ex vivo HMP reduced liver injury during cold ischemia, with significant protective effects on livers, especially of aged rats |

| Kron et al. (70) | Rats HOPE vs. SCS with Tx | Steatotic livers (≥60% macrosteatosis); N = 12/group CIT: 12 h |

1 h | HOPE after cold storage of severely fatty livers significantly prevented reperfusion injury (less oxidative stress, nuclear injury, Kupffer and endothelial cell activation, as well as less fibrosis within 1 week after Tx) and improved graft function |

| Compagnon et al. (71) | Porcine HMP vs. SCS with Tx | DCD; N = 6/group WIT: 1 h |

4 h | HMP-preserved livers functioned better and showed less hepatocellular and endothelial cell injury. In addition to improved energy metabolism, this protective effect was associated with an attenuation of inflammatory response, oxidative load, endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial damage, and apoptosis |

| Kakizaki et al. (72) | Porcine SNMP vs. SCS with Tx | DCD vs. DBD; N = 5/group WIT: 20 min CIT: 4 h |

30 min | SNMP before Tx provided some recovery from IR injury in DCD liver grafts and significantly improved the survival rate |

| Nostedt et al. (73) | Porcine NMP after initial flush with different solutions and temperatures without Tx | DCD; N = 4/group WIT: 1 h |

12 h | Avoiding initial hypothermia does not improve liver graft quality in a porcine DCD model of NMP |

| HUMAN STUDIES | ||||

| Henry et al. (34) | HMP vs. SCS with Tx |

N = 18 vs. 15 WIT: 45.1 ± 6.3 min CIT: 9.3 ± 2.2 h |

4.2 ± 0.9 h | HMP significantly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, relieving the downstream activation of adhesion molecules (ICAM-1) and migration of leukocytes, including neutrophils and macrophages, leading to improved overall outcomes |

| Bruinsma et al. (74) | SNMP without Tx | High-risk DCD and DBD; N = 7 WIT: ~28 min CIT: ~11.5 h |

3 h | SNMP effectively maintained liver function with minimal injury and sustained or improved various hepatobiliary parameters post-ischemia |

| Dutkowski et al. (75) | HOPE vs. SCS with Tx | DCD; N = 50 vs. 25 WIT: ~35 min CIT: ~6.5 h |

~2 h | HOPE protected extended DCD livers from initial reperfusion injury, leading to a better graft function and the prevention of intrahepatic biliary complications. Acute rejection rate was similar (16 vs. 12%) |

| Vogel et al. (76) | NMP without Tx | DCD (69%); N = 13 Mean age: 61.9 ± 11.3 years WIT: 11.3 ± 4 min CIT: 9.5 ± 3.7 h |

24 h | They demonstrated the possibility to perfuse high-risk livers consistently for 24 h. The neutrophil infiltrate in grafts was eliminated after prolonged NMP |

| Laing et al. (77) | NMP with Hemopure* vs. RBC- based solution (matched) without Tx |

High-risk (80% DCD); N = 5/group CIT: 7.5 h |

6 h | Hemopure-based perfusion fluid is a feasible alternative to the blood-based solution currently used for liver NMP and may be logistically, rheologically, and immunologically superior to packed RBCs |

| Nasralla et al. (78) | NMP vs. SCS with Tx | DBD and DCD (~36%); N = 121 vs. 101 | ~9 h | NMP was associated with a 50% lower level of graft injury, measured by hepatocellular enzyme release, despite a 50% lower rate of organ discard and a 54% longer mean preservation time. There was no significant difference in bile duct complications, graft survival, or survival of the patient |

ALT, alanine aminotransaminase; CIT, cold ischemia time; COR, controlled oxygenated rewarming; ECD, extended criteria donor; DCD, donation after circulatory death; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HMP, hypothermic MP; HOPE, hypothermic oxygenated perfusion; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; IL, interleukin; IRI, ischemia–reperfusion injury; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; MP, machine perfusion; NMP, normothermic MP; RBC, red blood cell; SCS, static cold storage; SNMP, subnormothermic MP; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; Tx, transplantation; WIT, warm ischemia time; HTK, histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate solution; VAS, vasosol solution; DBD, donor after brain death.

Hypothermic Machine Perfusion Techniques

In several studies in DCD rat models, a reduction in IRI in liver tissue was evident after HMP when compared to SCS (28, 29, 54, 56, 57, 61, 62). This finding was confirmed in large domestic animal studies (64, 71). Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) treatment of DCD and severely fatty livers significantly decreased IRI of hepatocytes by reducing the activation of Kupffer and endothelial cells (29, 70). Moreover, HOPE successfully suppressed the recipient's immune system, blunting the alloimmune pathway (28, 29). This was evident by decreased Kupffer and endothelial cell activation induced by initial anti-oxidative effects and damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) release as a consequence of HOPE treatment and liver Tx (28). Furthermore, T cell infiltration in liver grafts as well as blood levels of circulating activated T cells decreased (28). A short time (1 h) of reconditioning of DCD rat and porcine livers using HMP after up to 16 h of SCS showed improvements in organ quality (58, 64). Long-term (24 h) HMP of DCD rat livers markedly reduced HLA class II antigen expression on post-sinusoidal venular endothelium compared to SCS (55). Bae et al. (33) found that supplementation of HMP perfusion solution with the antioxidant, vitamin E, reduced inflammatory cytokine levels [IL-6, TNF-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1], involved in alloimmune response, in graft tissue. The addition of metformin to HMP preservation solution reduced liver IRI, with significant protective effects on livers, especially in aged rats (69). Furthermore, HMP significantly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8) (34). The attenuation of those cytokines affects many downstream pathways, including a reduced expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, MCP-1, P-selectin, and others. This effect subsequently decreases the level of neutrophil activation and inevitable leukocyte migration to stressed cell sites, leading to improved overall outcome rates in human livers (34). In another study, HOPE protected DCD livers from initial IRI, leading to improved graft function preventing intrahepatic biliary complications; however, acute rejection rate remained similar (16 vs. 12%) when compared to SCS (75).

Subnormothermic/Normothermic Machine Perfusion Techniques

SNMP and NMP significantly ameliorated hepatic damage in DCD livers compared to SCS in animal models (31, 39, 60, 65, 68, 72). In a porcine model of liver MP, prolonged periods of NMP facilitate a reduction in hepatic steatosis (63), while the supplementation of perfusate with defatting agents significantly reduced the intracellular fat content of perfused rat livers within a few hours (59). Efficient vasodilation was found to be important in order to improve the effectiveness in the preservation of DCD livers during NMP (66). Olschewski et al. (60) compared HMP to SNMP and SCS, demonstrating beneficial effects on the initial organ function, structural integrity of the sinusoidal endothelium, and hepatocellular damage when DCD rat livers were perfused using SNMP. Furthermore, SNMP was associated with lower IRI when compared to SCS (74), while prolonged NMP additionally eliminated the neutrophil infiltrate in grafts (76). Another study of ECD livers showed superiority of COR over HMP, SNMP, and SCS (38). When comparing NMP to SNMP and SCS, NMP was most efficient in terms of recovery of DCD livers (67). Avoiding initial hypothermia did not improve liver graft quality in a porcine DCD model of NMP (73). Recently, the first randomized controlled trial showed a 50% reduction in liver graft injury, despite a 50% decrease in the number of discarded organs and a 54% increased mean preservation time after a period of NMP compared to SCS (~36% of grafts were DCD). However, they found no significant difference in bile duct complications, graft, or patient survival (78).

The currently ongoing VITTAL trial aims to improve the suitability of non-transplantable livers in the UK by monitoring their function during NMP followed by Tx of the sufficiently improved graft (79, 80). We expect that the results of this novel approach could improve consistency and increase the usage of ECD liver grafts without compromising recipient safety.

Machine Perfusion of Extended Criteria Donor Lung Grafts

Experimental and clinical studies of ECD lungs and MP are compiled in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experimental and clinical studies of machine perfusion of extended criteria donor lung grafts.

| Studies | Model | Primary graft condition, N | MP time (h) | Results and immunological aspects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANIMAL STUDIES | ||||

| Nakajima et al. (81) | Canine HMP after SCS vs. SCS alone followed by 4 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N = 5/group WIT: 4 h CIT: 12 vs. 14 h |

2 | Short-term HMP could resuscitate ischemically damaged DCD lungs and ameliorate IRI. HMP significantly decreased oxidative damage and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines after reperfusion compared with SCS |

| Mulloy et al. (82) | Porcine NMP vs. SCS vs. SCS + NMP with Tx. Perfusate supplemented with adenosine A2A receptor agonist |

DCD; N = 5/group WIT: 60 min CIT: 4 h (SCS group) |

4 | The adenosine A2A receptor agonist exerts anti-inflammatory effects and reduces IRI when administered to DCD donor lungs during MP |

| Stone et al. (83) | Mice NMP ± A2A receptor agonist vs. SCS without Tx | DCD; N = 10–12/group WIT: 1 h CIT: 1 h |

1 | MP modulates pro-inflammatory genes and reduces pulmonary dysfunction, edema, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and neutrophil numbers in DCD lungs, which are further reduced by A2A receptor agonism |

| Stone et al. (9) | Porcine NMP vs. SCS with Tx | DCD; N = 12 WIT: 65 min CIT: 2 h |

3 | NMP resulted in reduction of donor leukocyte transfer into the recipient, and recipient T cell infiltration of the donor lung was significantly diminished |

| HUMAN STUDIES | ||||

| Stone et al. (36) | NMP without Tx | DCD; N = 7 WIT: 65 min CIT: 3 h |

2 | NMP showed the capacity to remove donor dendritic cell generating non-classical monocytes from graft |

| Nakajima et al. (35) | NMP ± broad-spectrum antibiotic without Tx | DBD with clinically diagnosed lung infection; N = 15 CIT: ~10 h |

12 | The results demonstrated that treatment with antibiotics significantly reduced bronchoalveolar lavage bacterial counts and inflammatory injury by decreasing endotoxin levels and key inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-1β, MIP-1α, MIP-1β) |

| Nakajima et al. (84) | NMP ± MSCs with Tx |

N = 6/group CIT: 24 h |

12 | The administration of MSCs ameliorated ischemic injury in donor lungs during NMP and attenuated the subsequent IRI after Tx |

CIT, cold ischemia time; ECD, extended criteria donor; DCD, donation after circulatory death; HMP, hypothermic MP; IL, interleukin; IRI, ischemia–reperfusion injury; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; MP, machine perfusion; MSCs, mesenchymal stromal cells; NMP, normothermic MP; SCS, static cold storage; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; Tx, transplantation; WIT, warm ischemia time; DBD, donor after brain death.

Hypothermic Machine Perfusion Techniques

Short-term HMP could resuscitate ischemically damaged DCD lungs and ameliorate IRI. In a canine model of MP, HMP improved the ATP production by the mitochondrial electron transport chain, leading to a significant decrease in oxidative damage and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) after reperfusion compared to SCS (81). Moreover, short-term HMP washed out residual microthrombi in the donor lungs. All of those factors are important for Tx outcomes, including the reduction of the immunological rejection rate.

Normothermic Machine Perfusion Techniques

NMP was able to modulate pro-inflammatory gene expression and reduce pulmonary dysfunction, edema, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the number of neutrophils in animal DCD lungs (82, 83). Moreover, NMP resulted in reduced donor leukocyte transfer into the recipient by inducing mobilization of donor leukocytes into the perfusate and allowing their removal via the leukocyte filter prior to Tx (9). Therefore, reduced donor leukocyte migration to recipient lymph nodes resulted in a reduction of direct allorecognition and T cell priming, diminishing recipient T cell infiltration, the hallmark of acute rejection (9). In a clinical study, NMP showed the capacity to remove donor dendritic cells generating non-classical monocytes, which are directly involved in immune surveillance, from the graft (36). NMP of donor after brain death (DBD) lungs with clinically diagnosed infection significantly reduced bacterial counts in the fluid of the bronchoalveolar lavage and inflammatory injury by decreasing endotoxin levels and key inflammatory mediators [TNF-α, IL-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β] when combined with broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment (35). The administration of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) ameliorated ischemic injury in donor lungs during ex vivo NMP and attenuated the subsequent IRI after Tx (84).

The use of MP in reconditioning of ECD donor lungs for Tx is currently under investigation in clinical trials (85, 86), with results being expected soon.

Machine Perfusion of Extended Criteria Donor Heart Grafts

Currently, clinical evidence of MP in ECD heart grafts is limited (Table 4). HMP improved the preservation of DCD heart grafts compared to SCS proven by superior post-reperfusion contractility. The underlying mechanisms could include enhanced preservation of the energetic states and superior cellular integrity (87). Recently, Korkmaz-Icöz et al. (88) demonstrated that HMP of aged donor hearts with MSCs protected against myocardial IRI in a rat model.

Table 4.

Experimental and clinical studies of machine perfusion of extended criteria donor heart grafts.

| Studies | Model | Primary graft condition, N | MP time (h) | Results and immunological aspects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANIMAL STUDIES | ||||

| Van Caenegem et al. (87) | Porcine HMP vs. SCS followed by 1 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N = 4/group WIT: 8–44 min |

4 | HMP improved the preservation of the heart grafts of DCD donors compared with SCS. This was proved by superior post-reperfusion contractility. The underlying mechanisms could include improved preservation of the energetic states and superior cellular integrity |

| Korkmaz-Icöz t al. (88) | Rats HMP ± MSCs with Tx | Aged donors; N = 6–9/group |

5 | HMP of donor hearts with MSCs protects against myocardial IRI in aged rats |

ECD, extended criteria donor; DCD, donation after circulatory death; HMP, hypothermic MP; IRI, ischemia–reperfusion injury; MP, machine perfusion; MSCs, mesenchymal stromal cells; SCS, static cold storage; Tx, transplantation; WIT, warm ischemia time.

Machine Perfusion of Extended Criteria Donor Pancreas Grafts

There is a limited number of studies evaluating the safety and feasibility of ex situ MP for ECD pancreas graft for whole-organ Tx (Table 5). HMP of porcine DCD pancreas was associated with a reduction in islet and acinar cell damage, stable perfusion dynamics, and minimal edematous weight change as well as potentially ameliorated endocrine viability and functionality after preservation (89, 90). More recent studies in the human pancreas indicated that especially DCD pancreas benefits more from oxygenated HMP compared to SCS alone (91). Even 24 h of HMP of ECD human pancreas–duodenum organs was feasible resulting in no deleterious parenchymal effects (92). Since those studies focused on the results after MP without following Tx, currently, there are no data available about clinical outcomes in this context.

Table 5.

Experimental and clinical studies of machine perfusion of extended criteria donor pancreas grafts.

| Studies | Model | Primary graft condition, N | MP time (h) | Results and immunological aspects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANIMAL STUDIES | ||||

| Karcz et al. (89) | Porcine HMP without Tx | DCD; N = 15 WIT: 25 min CIT: ~2.5 h |

5:25 | There was significant post-perfusion reduction in islet and acinar cell damage after HMP |

| Hamaoui et al. (90) | Porcine HMP after SCS vs. SCS alone followed by 2 h machine reperfusion | DCD; N = 3/group WIT: 30 min CIT: ~26.5 h |

5 | HMP-subjected grafts were associated with stable perfusion dynamics and minimal edematous weight change as well as potentially better endocrine viability and functionality |

| HUMAN STUDIES | ||||

| Leemkuil et al. (91) | HMP vs. SCS without Tx | Declined (DCD and DBD); N = 20 WIT: ~20 min CIT: ~4 h |

6 | This study indicated that especially the more injured DCD pancreas benefits more from oxygenated HMP compared with SCS alone |

| Branchereau et al. (92) | HMP vs. SCS without Tx | Rejected for organ or islet Tx; N = 7 vs. 2 WIT: n.d. CIT: n.d. |

24 | 24 h of HMP of ECD human pancreas–duodenum organs was feasible with no deleterious parenchymal effect |

CIT, cold ischemia time; ECD, extended criteria donor; DCD, donation after circulatory death; HMP, hypothermic MP; MP, machine perfusion; SCS, static cold storage; Tx, transplantation; WIT, warm ischemia time; DBD, donor after brain death.

Conclusion

MP allows successful utilization of more vulnerable and immunogenic otherwise discarded ECD organs. It has been shown that MP not only reduces the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and positively influences gene expression related to hypoxia during reperfusion but also induces donor-derived leukocytes, including dendritic cell-generating non-classical monocytes, mobilization, and removal prior to Tx. Moreover, MP was able to protect against epithelial and Kupffer cell activation and to reduce recipient T cell infiltration of the donor graft. More recently, novel methods such as viral vector delivery during MP to allografts are under investigation (93). This biological modification of the graft prior to Tx may be a future therapeutic strategy to suppress the immune response against the allograft leading to Tx without or at least reduced dose of the systemic immunosuppression that carries the additional risk of infection and malignancy. Many studies have already shown superiority of ECD organ MP over the current standard SCS. However, there are no general agreements on MP protocols, and wider clinical application is limited due to the lack of randomized controlled trials. More trials focusing on immunological pathways in the different MP settings with respect to every single organ are mandatory to get detailed mechanistic insights. This knowledge about various pathways will help us to optimize organ quality after MP of ECD organs and therefore improve Tx outcomes as well as graft and patient survival.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stone JP, Ball AL, Critchley WR, Major T, Edge RJ, Amin K, et al. Ex vivo normothermic perfusion induces donor-derived leukocyte mobilization and removal prior to renal jation. Kidney Int Rep. (2016) 1:230:9. 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dziodzio T, Biebl M, Pratschke J. Impact of brain death on ischemia/reperfusion injury in liver transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. (2014) 19:108:14. 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaeschke H. Preservation injury: mechanisms, prevention and consequences. J Hepatol. (1996) 25:774:80. 10.1016/S0168-8278(96)80253-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao H, Alam A, Soo AP, George AJT, Ma D. Ischemia-reperfusion injury reduces long term renal graft survival: mechanism and beyond. EBioMedicine. (2018) 28:31-42. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uehara M, Bahmani B, Jiang L, Jung S, Banouni N, Kasinath V, et al. Nanodelivery of mycophenolate mofetil to the organ improves transplant vasculopathy. ACS Nano. (2019) 13:12393-407. 10.1021/acsnano.9b05115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boardman DA, Jacob J, Smyth LA, Lombardi G, Lechler RI. What is direct allorecognition? Curr Transplant Rep. (2016) 3:275:83. 10.1007/s40472-016-0115-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siu JHY, Surendrakumar V, Richards JA, Pettigrew GJ. T cell allorecognition pathways in solid organ transplantation. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2548. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeWolf S, Sykes M. Alloimmune T cells in transplantation. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:2473:81. 10.1172/JCI90595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone JP, Critchley WR, Major T, Rajan G, Risnes I, Scott H, et al. Altered immunogenicity of donor lungs via removal of passenger leukocytes using Ex vivo lung perfusion. Am J Transplant. (2016) 16:33:43. 10.1111/ajt.13446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jing L, Yao L, Zhao M, Peng LP, Liu M. Organ preservation: from the past to the future. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2018) 39:845:57. 10.1038/aps.2017.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tingle SJ, Figueiredo RS, Moir JAG, Goodfellow M, Talbot D, Wilson CH. Machine perfusion preservation versus static cold storage for deceased donor kidney transplantation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 2019:CD011671 10.1002/14651858.CD011671.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czigany Z, Lurje I, Tolba RH, Neumann UP, Tacke F, Lurje G. Machine perfusion for liver transplantation in the era of marginal organs-New kids on the block. Liver Int. (2019) 39:228:49. 10.1111/liv.13946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiao B, Liu S, Liu H, Cheng D, Cheng Y, Liu Y. Hypothermic machine perfusion reduces delayed graft function and improves one-year graft survival of kidneys from expanded criteria donors: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e81826. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannon RM, Brock GN, Garrison RN, Smith JW, Marvin MR, Franklin GA. To pump or not to pump: a comparison of machine perfusion vs cold storage for deceased donor kidney transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. (2013) 216:625:33, discussion: 33-4. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moers C, Pirenne J, Paul A, Ploeg RJ. Machine perfusion or cold storage in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. (2012) 366:770:1. 10.1056/NEJMc1111038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tittelbach-Helmrich D, Thurow C, Arwinski S, Schleicher C, Hopt UT, Bausch D, et al. Poor organ quality and donor-recipient age mismatch rather than poor donation rates account for the decrease in deceased kidney transplantation rates in a Germany Transplant Center. Transpl Int. (2015) 28:191:8. 10.1111/tri.12478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aubert O, Kamar N, Vernerey D, Viglietti D, Martinez F, Duong-Van-Huyen JP, et al. Long term outcomes of transplantation using kidneys from expanded criteria donors: prospective, population based cohort study. BMJ. (2015) 351:h3557. 10.1136/bmj.h3557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Echterdiek F, Schwenger V, Döhler B, Latus J, Kitterer D, Heemann U, et al. Kidneys from elderly deceased donors-Is 70 the new 60? Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2701. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pratschke J, Merk V, Reutzel-Selke A, Pascher A, Denecke C, Lun A, et al. Potent early immune response after kidney transplantation in patients of the European senior transplant program. Transplantation. (2009) 87:992:1000. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819ca0d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filiopoulos V, Boletis JN. Renal transplantation with expanded criteria donors: which is the optimal immunosuppression? World J Transplant. (2016) 6:103:14. 10.5500/wjt.v6.i1.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reutzel-Selke A, Jurisch A, Denecke C, Pascher A, Martins PN, Kessler H, et al. Donor age intensifies the early immune response after transplantation. Kidney Int. (2007) 71:629:36. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snell G, Hiho S, Levvey B, Sullivan L, Westall G. Consequences of donor-derived passengers (pathogens, cells, biological molecules and proteins) on clinical outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2019) 38:902:6. 10.1016/j.healun.2019.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maggiore U, Oberbauer R, Pascual J, Viklicky O, Dudley C, Budde K, et al. Strategies to increase the donor pool and access to kidney transplantation: an international perspective. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2015) 30:217:22. 10.1093/ndt/gfu212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Attia M, Silva MA, Mirza DF. The marginal liver donor–an update. Transpl Int. (2008) 21:713:24. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farney AC, Hines MH, al-Geizawi S, Rogers J, Stratta RJ. Lessons learned from a single center's experience with 134 donation after cardiac death donor kidney transplants. J Am Coll Surg. (2011) 212:440:51, discussion: 51-3. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritschl PV, Gunther J, Hofhansel L, Kuhl AA, Sattler A, Ernst S, et al. Graft pre-conditioning by peri-operative perfusion of kidney allografts with rabbit anti-human T-lymphocyte globulin results in improved kidney graft function in the early post-transplantation period-a prospective, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1911. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaziri N, Thuillier R, Favreau FD, Eugene M, Milin S, Chatauret NP, et al. Analysis of machine perfusion benefits in kidney grafts: a preclinical study. J Transl Med. (2011) 9:15. 10.1186/1479-5876-9-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlegel A, Kron P, Graf R, Clavien PA, Dutkowski P. Hypothermic Oxygenated Perfusion (HOPE) downregulates the immune response in a rat model of liver transplantation. Ann Surg. (2014) 260:931:7, discussion: 7-8. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlegel A, Graf R, Clavien PA, Dutkowski P. Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) protects from biliary injury in a rodent model of DCD liver transplantation. J Hepatol. (2013) 59:984:91. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrigno A, Rizzo V, Boncompagni E, Bianchi A, Gringeri E, Neri D, et al. Machine perfusion at 20 degrees C reduces preservation damage to livers from non-heart beating donors. Cryobiology. (2011) 62:152:8. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gringeri E, Bonsignore P, Bassi D, D'Amico FE, Mescoli C, Polacco M, et al. Subnormothermic machine perfusion for non-heart-beating donor liver grafts preservation in a Swine model: a new strategy to increase the donor pool? Transplant Proc. (2012) 44:2026:8. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tozzi M, Franchin M, Soldini G, Ietto G, Chiappa C, Maritan E, et al. Impact of static cold storage VS hypothermic machine preservation on ischemic kidney graft: inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules as markers of ischemia/reperfusion tissue damage. Our preliminary results. Int J Surg. (2013) 11:S110-4. 10.1016/S1743-9191(13)60029-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bae C, Pichardo EM, Huang H, Henry SD, Guarrera JV. The benefits of hypothermic machine perfusion are enhanced with Vasosol and alpha-tocopherol in rodent donation after cardiac death livers. Transplant Proc. (2014) 46:1560:6. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.12.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry SD, Nachber E, Tulipan J, Stone J, Bae C, Reznik L, et al. Hypothermic machine preservation reduces molecular markers of ischemia/reperfusion injury in human liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. (2012) 12:2477:86. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakajima D, Cypel M, Bonato R, Machuca TN, Iskender I, Hashimoto K, et al. Ex vivo perfusion treatment of infection in human donor lungs. Am J Transplant. (2016) 16:1229:37. 10.1111/ajt.13562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stone JP, Sevenoaks H, Sjoberg T, Steen S, Yonan N, Fildes JE. Mechanical removal of dendritic cell-generating non-classical monocytes via Ex vivo lung perfusion. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2014) 33:864:9. 10.1016/j.healun.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bian S, Zhu Z, Sun L, Wei L, Qu W, Zeng Z, et al. Normothermic machine perfusion versus cold storage of liver in pig model: a meta-analysis. Ann Transpl. (2018) 23:197-206. 10.12659/AOT.908774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minor T, Efferz P, Fox M, Wohlschlaeger J, Lüer B. Controlled oxygenated rewarming of cold stored liver grafts by thermally graduated machine perfusion prior to reperfusion. Am J Transpl. (2013) 13:1450:60. 10.1111/ajt.12235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knaak JM, Spetzler VN, Goldaracena N, Louis KS, Selzner N, Selzner M. Technique of subnormothermic Ex vivo liver perfusion for the storage, assessment, and repair of marginal liver grafts. J Vis Exp. (2014) 90:e51419 10.3791/51419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Treckmann J, Nagelschmidt M, Minor T, Saner F, Saad S, Paul A. Function and quality of kidneys after cold storage, machine perfusion, or retrograde oxygen persufflation: results from a porcine autotransplantation model. Cryobiology. (2009) 59:19:23. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thuillier R, Allain G, Celhay O, Hebrard W, Barrou B, Badet L, et al. Benefits of active oxygenation during hypothermic machine perfusion of kidneys in a preclinical model of deceased after cardiac death donors. J Surg Res. (2013) 184:1174:81. 10.1016/j.jss.2013.04.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasil A, Giraud S, Couturier P, Amiri A, Danion J, Donatini G, et al. Individual and combined impact of oxygen and oxygen transporter supplementation during kidney machine preservation in a porcine preclinical kidney transplantation model. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:1992. 10.3390/ijms20081992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reznik ON, Bagnenko SF, Loginov IV, Iljina VA, Ananyev AN, Eremich SV, et al. Machine perfusion as a tool to select kidneys recovered from uncontrolled donors after cardiac death. Transplant Proc. (2008) 40:1023:6. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treckmann J, Moers C, Smits JM, Gallinat A, Maathuis MH, van Kasterop-Kutz M, et al. Machine perfusion versus cold storage for preservation of kidneys from expanded criteria donors after brain death. Transpl Int. (2011) 24:548:54. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicholson ML, Hosgood SA. Renal transplantation after Ex vivo normothermic perfusion: the first clinical study. Am J Transplant. (2013) 13:1246:52. 10.1111/ajt.12179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wszola M, Kwiatkowski A, Domagala P, Wirkowska A, Bieniasz M, Diuwe P, et al. Preservation of kidneys by machine perfusion influences gene expression and may limit ischemia/reperfusion injury. Prog Transplant. (2014) 24:19:26. 10.7182/pit2014384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang W, Xie D, Hu X, Yin H, Liu H, Zhang X. Effect of hypothermic machine perfusion on the preservation of kidneys donated after cardiac death: a single-center, randomized, controlled trial. Artif Organs. (2017) 41:753:8. 10.1111/aor.12836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gallinat A, Amrillaeva V, Hoyer DP, Kocabayoglu P, Benko T, Treckmann JW, et al. Reconditioning by end-ischemic hypothermic in-house machine perfusion: a promising strategy to improve outcome in expanded criteria donors kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant. (2017) 31:e12904. 10.1111/ctr.12904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weissenbacher A, Lo Faro L, Boubriak O, Soares MF, Roberts IS, Hunter JP, et al. Twenty-four-hour normothermic perfusion of discarded human kidneys with urine recirculation. Am J Transplant. (2019) 19:178:92. 10.1111/ajt.14932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruiz-Hernandez M, Gomez-Dos Santos V, Diaz-Perez D, Fernandez-Alcalde A, Hevia-Palacios V, Alvarez-Rodriguez S, et al. Experience with hypothermic machine perfusion in expanded criteria donors: functional outcomes. Transplant Proc. (2019) 51:303:6. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Savoye E, Macher MA, Videcoq M, Gatault P, Hazzan M, Abboud I, et al. Evaluation of outcomes in renal transplantation with hypothermic machine perfusion for the preservation of kidneys from expanded criteria donors. Clin Transplant. (2019) 33:e13536. 10.1111/ctr.13536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Investig. (2003) 112:1776:84. 10.1172/JCI200320530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kahn J, Schemmer P. Control of ischemia-reperfusion injury in liver transplantation: potentials for increasing the donor pool. Visc Med. (2018) 34:444:8. 10.1159/000493889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee CY, Zhang JX, Jones JWJ, Southard JH, Clemens MG. Functional recovery of preserved livers following warm ischemia: improvement by machine perfusion preservation. Transplantation. (2002) 74:944:51. 10.1097/00007890-200210150-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lauschke H, Olschewski P, Tolba R, Schulz S, Minor T. Oxygenated machine perfusion mitigates surface antigen expression and improves preservation of predamaged donor livers. Cryobiology. (2003) 46:53:60. 10.1016/S0011-2240(02)00164-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee CY, Jain S, Duncan HM, Zhang JX, Jones JW, Jr, Southard JH, et al. Survival transplantation of preserved non-heart-beating donor rat livers: preservation by hypothermic machine perfusion. Transplantation. (2003) 76:1432:6. 10.1097/01.TP.0000088674.23805.0F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bessems M, Doorschodt BM, van Vliet AK, van Gulik TM. Machine perfusion preservation of the non-heart-beating donor rat livers using polysol, a new preservation solution. Transplant Proc. (2005) 37:326:8. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manekeller S, Seinsche A, Stegemann J, Hirner A. Optimising post-conditioning time of marginal donor livers. Langenbecks Arch Surg. (2008) 393:311:6. 10.1007/s00423-008-0288-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagrath D, Xu H, Tanimura Y, Zuo R, Berthiaume F, Avila M, et al. Metabolic preconditioning of donor organs: defatting fatty livers by normothermic perfusion ex vivo. Metab Eng. (2009) 11:274-83. 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olschewski P, Gass P, Ariyakhagorn V, Jasse K, Hunold G, Menzel M, et al. The influence of storage temperature during machine perfusion on preservation quality of marginal donor livers. Cryobiology. (2010) 60:337:43. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stegemann J, Hirner A, Rauen U, Minor T. Use of a new modified HTK solution for machine preservation of marginal liver grafts. J Surg Res. (2010) 160:155:62. 10.1016/j.jss.2008.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stegemann J, Hirner A, Rauen U, Minor T. Gaseous oxygen persufflation or oxygenated machine perfusion with Custodiol-N for long-term preservation of ischemic rat livers? Cryobiology. (2009) 58:45:51. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2008.10.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jamieson RW, Zilvetti M, Roy D, Hughes D, Morovat A, Coussios CC, et al. Hepatic steatosis and normothermic perfusion-preliminary experiments in a porcine model. Transplantation. (2011) 92:289:95. 10.1097/TP.0b013e318223d817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schlegel A, de Rougemont O, Graf R, Clavien PA, Dutkowski P. Protective mechanisms of end-ischemic cold machine perfusion in DCD liver grafts. J Hepatol. (2013) 58:278:86. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Izamis ML, Tolboom H, Uygun B, Berthiaume F, Yarmush ML, Uygun K. Resuscitation of ischemic donor livers with normothermic machine perfusion: a metabolic flux analysis of treatment in rats. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e69758. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nassar A, Liu Q, Farias K, D'Amico G, Buccini L, Urcuyo D, et al. Role of vasodilation during normothermic machine perfusion of DCD porcine livers. Int J Artif Organs. (2014) 37:165:72. 10.5301/ijao.5000297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nassar A, Liu Q, Farias K, Buccini L, Baldwin W, Bennett A, et al. Impact of temperature on porcine liver machine perfusion from donors after cardiac death. Artif Organs. (2016) 40:999:1008. 10.1111/aor.12699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ferrigno A, Di Pasqua LG, Berardo C, Siciliano V, Rizzo V, Mannucci B, et al. Liver graft susceptibility during static cold storage and dynamic machine perfusion: DCD versus fatty livers. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 19:109. 10.3390/ijms19010109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chai YC, Dang GX, He HQ, Shi JH, Zhang HK, Zhang RT, et al. Hypothermic machine perfusion with metformin-University of Wisconsin solution for Ex vivo preservation of standard and marginal liver grafts in a rat model. World J Gastroenterol. (2017) 23:7221:31. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i40.7221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kron P, Schlegel A, Mancina L, Clavien PA, Dutkowski P. Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) for fatty liver grafts in rats and humans. J Hepatol. (2017) 68:82–91. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Compagnon P, Levesque E, Hentati H, Disabato M, Calderaro J, Feray C, et al. An oxygenated and transportable machine perfusion system fully rescues liver grafts exposed to lethal ischemic damage in a pig model of DCD liver transplantation. Transplantation. (2017) 101:e205-13. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kakizaki Y, Miyagi S, Shimizu K, Kumata H, Matsumura M, Miyazaki Y, et al. Effects of subnormothermic perfusion before transplantation for liver grafts from donation after cardiac death: a simplified dripping perfusion method in pigs. Transplant Proc. (2018) 50:1538:43. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.02.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nostedt JJ, Churchill T, Ghosh S, Thiesen A, Hopkins J, Lees MC, et al. Avoiding initial hypothermia does not improve liver graft quality in a porcine donation after circulatory death (DCD) model of normothermic perfusion. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0220786 10.1371/journal.pone.0220786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bruinsma BG, Yeh H, Ozer S, Martins PN, Farmer A, Wu W, et al. Subnormothermic machine perfusion for Ex vivo preservation and recovery of the human liver for transplantation. Am J Transplant. (2014) 14:1400:9. 10.1111/ajt.12727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dutkowski P, Polak WG, Muiesan P, Schlegel A, Verhoeven CJ, Scalera I, et al. First comparison of hypothermic oxygenated perfusion versus static cold storage of human donation after cardiac death liver transplants: an international-matched case analysis. Ann Surg. (2015) 262:764:70, discussion 70-1. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vogel T, Brockmann JG, Quaglia A, Morovat A, Jassem W, Heaton ND, et al. The 24-hour normothermic machine perfusion of discarded human liver grafts. Liver Transpl. (2017) 23:207:20. 10.1002/lt.24672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laing RW, Bhogal RH, Wallace L, Boteon Y, Neil DAH, Smith A, et al. The use of an acellular oxygen carrier in a human liver model of normothermic machine perfusion. Transplantation. (2017) 101:2746:56. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nasralla D, Coussios CC, Mergental H, Akhtar MZ, Butler AJ, Ceresa CDL, et al. A randomized trial of normothermic preservation in liver transplantation. Nature. (2018) 557:50:6. 10.1038/s41586-018-0047-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Laing RW, Mergental H, Yap C, Kirkham A, Whilku M, Barton D, et al. Viability testing and transplantation of marginal livers (VITTAL) using normothermic machine perfusion: study protocol for an open-label, non-randomised, prospective, single-arm trial. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017733. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Transporter LL. (2019). Available online at: https://www.organ-recovery.com/lifeport-liver-transporter (accessed October 1, 2019).

- 81.Nakajima D, Chen F, Okita K, Motoyama H, Hijiya K, Ohsumi A, et al. Reconditioning lungs donated after cardiac death using short-term hypothermic machine perfusion. Transplantation. (2012) 94:999:1004. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826f632e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mulloy DP, Stone ML, Crosby IK, Lapar DJ, Sharma AK, Webb DV, et al. Ex vivo rehabilitation of non-heart-beating donor lungs in preclinical porcine model: delayed perfusion results in superior lung function. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2012) 144:1208:15. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stone ML, Sharma AK, Mas VR, Gehrau RC, Mulloy DP, Zhao Y, et al. Ex vivo perfusion with adenosine A2A receptor agonist enhances rehabilitation of murine donor lungs after circulatory death. Transplantation. (2015) 99:2494:503. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakajima D, Watanabe Y, Ohsumi A, Pipkin M, Chen M, Mordant P, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy during Ex vivo lung perfusion ameliorates ischemia-reperfusion injury in lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2019) 38:1214-23. 10.1016/j.healun.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vanecek J. Cellular mechanisms of melatonin action. Physiol Rev. (1998) 78:687:721. 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Novel, Lung Trial: Normothermic Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion (EVLP) As An Assessment of Extended/Marginal Donor Lungs ,. Available online at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01365429 (accessed October 1, 2019).

- 87.Van Caenegem O, Beauloye C, Bertrand L, Horman S, Lepropre S, Sparavier G, et al. Hypothermic continuous machine perfusion enables preservation of energy charge and functional recovery of heart grafts in an Ex vivo model of donation following circulatory death. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2016) 49:1348:53. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Korkmaz-Icöoz S, Li S, Huüttner R, Ruppert M, Radovits T, Loganathan S, et al. Hypothermic perfusion of donor heart with a preservation solution supplemented by mesenchymal stem cells. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2019) 38:315:26. 10.1016/j.healun.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Karcz M, Cook HT, Sibbons P, Gray C, Dorling A, Papalois V. An ex-vivo model for hypothermic pulsatile perfusion of porcine pancreata: hemodynamic and morphologic characteristics. Exp Clin Transplant. (2010) 8:55:60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hamaoui K, Gowers S, Sandhu B, Vallant N, Cook T, Boutelle M, et al. Development of pancreatic machine perfusion: translational steps from porcine to human models. J Surg Res. (2018) 223:263-4. 10.1016/j.jss.2017.11.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leemkuil M, Lier G, Engelse MA, Ploeg RJ, de Koning EJP, t Hart NA, et al. Hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion of the human donor pancreas. Transplant Direct. (2018) 4:e388. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Branchereau J, Renaudin K, Kervella D, Bernadet S, Karam G, Blancho G, et al. Hypothermic pulsatile perfusion of human pancreas: preliminary technical feasibility study based on histology. Cryobiology. (2018) 85:56-62. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bishawi M, Roan JN, Milano CA, Daneshmand MA, Schroder JN, Chiang Y, et al. A normothermic Ex vivo organ perfusion delivery method for cardiac transplantation gene therapy. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:8029. 10.1038/s41598-019-43737-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]