Abstract

Background:

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is an entrapment neuropathy in which the tibial nerve is compressed within the tarsal tunnel and causes sensory disturbance in the sole of the foot. In this manuscript, we summarized our early surgical cases of TTS.

Materials and Methods:

Six feet in five patients with TTS were treated surgically. The patients were aged 31–70 years (mean 53.1 years), and all of them complained of pain or dysesthesia of the sole of the foot sparing the heel. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and nerve conduction test were performed preoperatively. In surgery, flexor retinaculum was dissected (tarsal tunnel opening [TTO]), the posterior tibial nerve was freed from the arteriovenous complex (neurovascular decompression [NVD]), and fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle was excised to decompress the medial and lateral plantar nerve (releasing fascial of abductor hallucis muscle [RFAH]).

Results:

Preoperative MRI confirmed that all seven cases were idiopathic TTS. Moreover, NCD demonstrated delayed sensory conduction velocity but not delayed distal motor latency. Surgical decompression was beneficial in 5 feet. The recurrence of symptoms was found in one case within 1 postoperative month.

Conclusion:

Surgical treatment for idiopathic TTS with TTO, NVD, and RFAH was generally good. However, symptoms recurred in one instance. Some methods to prevent adhesion and granulation in the reconstructed tarsal tunnel should be considered.

Keywords: Nerve conduction study, surgery, tarsal tunnel syndrome

Introduction

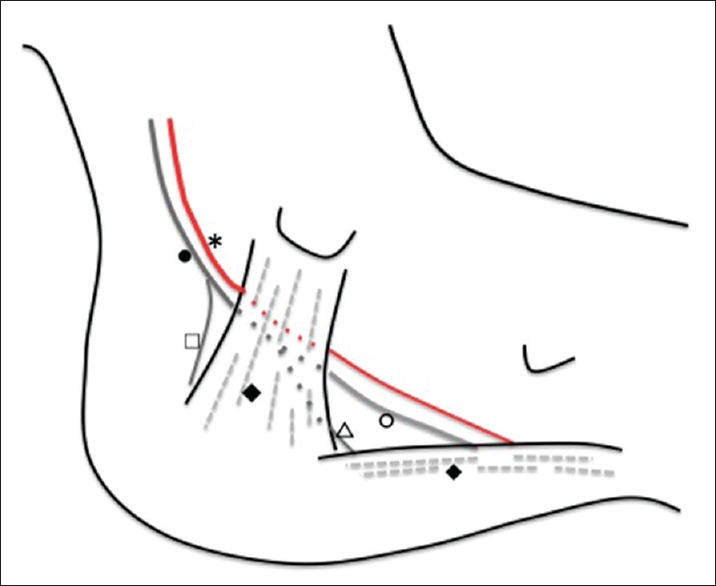

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS), also described as tibial nerve dysfunction or posterior tibial nerve neuralgia, is an entrapment neuropathy associated with the compression of the tibial nerve within the tarsal tunnel [Figure 1].[1,2] TTS is the disease whose optimal management remains controversial because of the diagnostic uncertainty and lack of clarity about which patients would get benefit from surgical treatment.[1,2] Because not a few patients with plantar sensory disturbance visited our department, we came to diagnose and manage these patients actively and started the surgical treatment of TTS in 2018. In this manuscript, we summarized our first surgical cases of TTS and conducted a literature review to discuss issues on the management of TTS.

Figure 1.

Medial view of the left foot/ankle demonstrating anatomical structures relevant to the tarsal tunnel. The tarsal tunnel is a fibro-osseous space behind the flexor retinaculum (♦). Posterior tibial nerve (er passes along the tarsal tunnel with the posterior tibial artery (*) and bifurcate to form medial (ed and lateral plantar nerve (△). The medial calcaneal nerve (□) typically branches off of the posterior tibial nerve proximal to the tarsal tunnel. The medial plantar nerve passes deep to the abductor halluces muscle (♦), and the lateral plantar nerve passes directly through it

Materials and Methods

In this study, six patients of TTS surgically treated in our department from January 2018 to August 2019 were evaluated retrospectively. The diagnosis of TTS was made based on a detailed history and clinical examination. We excluded patients with evident diabetes mellitus (HbA1c >6.3). When plantar sensory disturbance excluding heel and a positive Tinel's sign over the tarsal tunnel were recognized, the patient was diagnosed possibly to be TTS. These patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and nerve conduction test (NCT). MRI was performed to assess space-occupying lesions or other causes of nerve compression.[2,3] We performed NCT for all surgical cases and evaluated the results by Mondelli's scale. In Mondelli's scale, electrophysiological severity was scored from 0 to 5 based on motor conduction velocity, distal motor latency (DML), sensory conduction velocity (SCV), and sensory action potential (SAP) [Table 1a].[4] The motor conduction test for tibial nerve was performed, stimulating the nerve supramaximally at the popliteal fossa and flexor retinaculum; surface recording electrodes were placed on the motor point of the abductor hallucinations muscle. DML was determined at a distance between stimulating and recording points of 14 cm. SCV and SAP were studied by stimulating the big toe for the medial plantar nerve (MPN) (T1) and the little toe for the lateral plantar nerve (LPN) (T5) with recording at the ankle above the flexor retinaculum by surface electrodes.[5,6] Electrophysiological values of each subject were considered abnormal, if they were 2 standard deviation (SD) below or above the mean of controls (DML: 4.6 ± 0.4 ms, MPN SCV: 37.5 ± 2.3 m/s, and LPN SCV 36.7 ± 2.8 m/s).[2,4,5]

Table 1.

Evaluation methods of tarsal tunnel syndrome used in this study

| (a) To evaluate electrophysiological severity of tarsal tunnel syndrome, Mondelli’s scale was used in this study, which scored from 0 to 5 based on motor conduction velocity, DML, SCV and SAP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Electrophysiological parameters | ||

| 0 | Normal SCV and DML | ||

| 1 | Normal absolute SCV with abnormal comparative tests | ||

| 2 | Slowing SCV and normal DML | ||

| 3 | Slowing of SCV and DML | ||

| 4 | Absence of T1 and T5 SAPs and abnormal DML | ||

| 5 | Absence of sensory and motor response | ||

| (b) A simple rating scale for tarsal tunnel syndrome reported by Takakura et al., in which 10 indicates a normal foot and 0 indicates the most symptomatic foot (Takakura scale) | |||

| Absent | Some | Definite | |

| Spontaneous pain or pain on movement | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Burning pain | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Tinel’s sign | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Sensory disturbance | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Muscle atrophy or weakness | 2 | 1 | 0 |

DML – Distal motor latency; SCV – Sensory conduction velocity; SAP – Sensory action potential

We treated these patients with conservative methods, which include restriction of excessive exercise or walking, pasting a compress, and oral analgesics. When conservative treatment failed to resolve the patient's symptoms, the surgical treatment was indicated. Before surgery, the severity of TTS symptom was evaluated by a simple rating scale reported by Takakura et al. (Takakura scale).[7] In the Takakura scale, 10 indicates a normal foot, and 0 shows the most symptomatic foot [Table 1b]. The postoperative symptom was also evaluated by the Takayasu scale 1 month after surgery. We assessed the surgical result as follows: Poor – Takakura scale did not increase; good – Takakura scale increased by 1 or 2; and excellent – Takakura scale increased by more than 3.

The surgical procedure in our department

So that patients can report the improvement of symptoms during surgery, sedatives were not administered. Under local anesthesia, a 7 cm bow-like skin incision was made 1.5 cm below the medial malleolus without a tourniquet. Using a microscope, we dissected the flexor retinaculum from the proximal to the distal end of the tarsal tunnel. Then, the posterior tibial artery and veins (arteriovenous complex) were exposed (tarsal tunnel opening [TTO]). Moreover, the posterior tibial nerve was identified, which was freed from the dissected arteriovenous complex. To prevent postoperative adhesion and delayed neuropathy, further removal of connective tissue surrounding the posterior tibial nerve and vessels was performed. During this procedure, we minimally coagulated and cut small arteries originating from the posterior tibial artery flexible. Then, the adequate arterial pulsation was confirmed (neurovascular decompression [NVD]). In case symptom relief was not achieved by NVD, fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle was excised to decompress the distal part of the medial and LPN (releasing fascial of abductor hallucis muscle [RFAH]). When the patients report symptom improvement and disappearance of the Tinel's sign by RFAH, the skin was closed without closure of the dissected retinaculum. After surgery, the patients are allowed to walk without cast immobilization.

Data were expressed as the mean ± SD. To compare the pre- and post-operative Takakura scale, a paired t-test was used. Variables were considered to be statistically significant when the significance level was <0.05.

Results

We surgically treated 6 feet in five patients (one man and four women) with TTS [Table 2]. The duration between onset and surgery was 12–96 months (mean 38.0 ± 23.5 months). The affected foot was the right in two, left in two, and bilateral in one. The patients were aged 59–78 years (mean 70.6 ± 27.0 years) at the time of treatment. All of the patients complained subjectively of pain or numbness in the sole excluding the heel, and Tinel's sign was also positive in all of the 6 feet.

Table 2.

Summary of 5 patients for whom tarsal tunnel syndrome was surgically treated in our department

| Case number | Age/sex | Duration (onset-treatment) | Side | Etiology | Hb A1c | MS | Preoperator TS | Surgical procedure | Postoperator TS (surgical outcome) | Complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 76 female | 36 months | Right | Idiopathic | 5.0 | 2 | 4 | TTO, NVD | 6 (good) | Fluid discharge |

| 2 | 69 female | 24 months | Right | Idiopathic | 5.7 | 2 | 3 | TTO, NVD, RFAH | 3 (poor) | Fluid discharge |

| 3 | 59 female | 42 months | Right | Idiopathic | 5.5 | 2 | 5 | TTO, NVD, RFAH | 8 (excellent) | No |

| 42 months | Left | Idiopathic | 5.5 | 2 | 6 | TTO, NVD, RFAH | 9 (excellent) | No | ||

| 4 | 71 female | 12 months | Left | Idiopathic | 6.0 | 2 | 5 | TTO, NVD | 7 (good) | No |

| 5 | 78 male | 72 months | Left | Idiopathic | 5.4 | 2 | 3 | TTO, NVD | 9 (excellent) | No |

TTO – Tarsal tunnel opening; NVD – Neurovascular decompression, RFAH – Releasing fascial of abductor hallucis muscle, MS – Mondelli’s scale, TS – Takakura scale; Hb A1c – Hemoglobin A1c

Our series did not include patients with a space-occupying mass lesion, and all patients were diagnosed to be idiopathic TTS. The preoperative Takakura scale was 3–6 (mean = 4.33 ± 1.21), and the Mondelli's scale was two in all cases. During surgery, we could not confirm sufficient improved symptoms and the disappearance of Tinel's sign by TTO and NVD in cases 2 and 3; RFAH was added for these patients. The postoperative Takakura scale was 3–9 (mean = 7.00 ± 2.28), which was statistically improved compared with the preoperative one. No major complication was recognized. However, in the first 2 cases, some fluid leakage from the operative wound was observed for 3–7 postoperative days. Therefore, after the third surgery, patients were instructed to keep rest as much as possible and discharged after stitch removal on the 10th postoperative day, which resulted in no fluid discharge from the operative wound.

Illustrative cases

Case 2: 76-year-old female

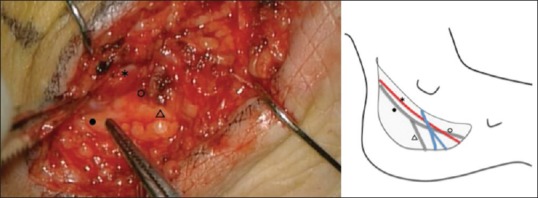

Three years before, the patient had been aware of the right plantar numbness. The cause was unknown, and she had been treated conservatively at a nearby hospital. The TTS was suspected because plantar dysesthesia spared heel, and the Tinel's sign was positive over the tarsal tunnel. In NCT, delayed SCV (18.5 m/s) and normal DML (4.3 ms) of the posterior tibial nerve were confirmed, and the evaluation resulted in Mondelli's scale 2. Based on the findings, we concluded that the possibility of TTS was high. After consulting with the patient, surgery was performed. Takakura scale before the operation was 4. During the surgery, when TTO and NVD were completed, improved symptoms was confirmed, and the Tinel's sign disappeared [Figure 2]. Therefore, the operation was terminated without RFAH. The postoperative course was good, and symptoms improved. The patient discharged 1 day after surgery. However, fluid leakage from the operative wound was observed 2 days after surgery. We recommended the patient to keep the rest as much as possible. After that, fluid leakage decreased and stopped on the 7th day, and no infection was observed. The stitches were removed 14 days after the operation. Takakura scale, 1 month after surgery, was 6.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative finding of case 2. Medial view of the left ankle during surgery after dissection of flexor retinaculum. *Posterior tibial artery, •Posterior tibial nerve, △Lateral plantar nerve, ○Medial plantar nerve

Case 3: 69-year-old female

Two years before, the patient had been aware of the right plantar numbness. She was treated conservatively at a nearby hospital. When she consulted our department, the TTS was suspected because plantar dysesthesia spared heel, and the Tinel's sign was positive over the tarsal tunnel. MRI revealed no space-occupying lesions in tarsal tunnel. By NCT, we confirmed delayed SCV (22.1 m/s) and normal DML (4.5 ms) of the posterior tibial nerve (Mondelli's scale 2). Based on these findings, we concluded that the possibility of TTS was high, and surgery was performed. Takakura scale before the operation was 3. During the surgery, when TTO and NVD were completed, improved symptoms were not confirmed, and the Tinel's sign did not disappear. Therefore, RFAH was added until improved plantar dysesthesia and disappearance of the Tinel's sign were confirmed. The postoperative course was good, and symptoms improved for 3 days. However, plantar dysesthesia aggravated 3 days after surgery. Fluid leakage from the operative wound was observed on the day after surgery. Moreover, the patient was keep the rest as much as possible. After that, fluid leakage decreased and stopped on the 5th day, and no infection was observed. The stitches were removed 11 days after the operation and discharged. Takakura scale, 1 month after surgery, was 3. We considered reoperation but did not get consent from the patient. Therefore, she was followed up in the outpatient.

Discussion

About tarsal tunnel syndrome

The tarsal tunnel is a fibro-osseous space located behind and inferior to the medial malleolus. Anterosuperiorly, the tarsal tunnel is surrounded by the medial malleolus, laterally by the posterior talus and calcaneus. The tarsal tunnel prevents medial displacement of its contents with the flexor retinaculum, which extends from the medial malleolus to the medial calcaneus [Figure 1].[1,2] Within tarsal tunnel, there are several important structures, including the tendons of the posterior tibialis, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus muscles. As well as the posterior tibial nerve, the posterior tibial artery and vein also pass through it.[1,2]

Although the anatomy is highly variable, the posterior tibial nerve typically divides into three terminal branches, the medial plantar, the lateral plantar, and the medial calcaneal nerve.[8,9] The medial calcaneal branches arise from the tibial nerve, or occasionally from the LPN.[8,9] Because it branches before entering TTS, sensory disturbance of TTS mostly spare the heel.[8]

TTS was first reported in 1962 by Keck and Lam in two independent publications.[10,11] Patients with TTS characteristically report pain directly over the tarsal tunnel that radiates to the arch and plantar foot. A sharp shooting pain, numbness, tingling or burning sensation on the plantar surface, which exacerbate either on standing, prolonged walking, wearing tight footwear, or at night.[1,2] Such symptoms will vary depending on whether the entire posterior tibial nerve is compressed or if it is the lateral or medial plantar branches. It is noteworthy that pain may sometimes also extend proximally to the mid-calf region by percussion of the nerve at the site of entrapment, which is known as the Valleix phenomenon.[12]

Diagnosis of tarsal tunnel syndrome

The efficacy of the NCT in TTS diagnosis has not reached consensus in the literature;[2,13] however, as an aid for diagnosis, we performed it for all surgical cases. Although distal motor abnormality is sensitive indicators of the presence of pathology,[6] some authors report an unacceptable level of false-negative results. On the other hand, sensory anomalies are more frequently detected than DML delays in TTS.[6] Oh et al. considered that the examination of SCV was a more rewarding test for diagnosis, and abnormal conduction (either absent spike or slow conduction velocity) was present in 90.5% of their cases.[6,14] We performed NCT for all six surgical feet, and we could not confirm motor abnormality but detected delayed SCV in all cases. We are going to continue to accumulate cases and determine whether SCV might be used before surgery as an adjunct evaluation of TTS to confirm physical findings.

No specific test for the diagnosis of TTS has been reported, and diagnosis is based on a detailed history and clinical examination. In spite that strength deficits are typically a late finding in TTS, muscle atrophy of abductor halluces and abductor digiti minimi should be carefully assessed.[15]

Differential diagnosis of tarsal tunnel syndrome

The differential diagnosis of TTS is broad. It includes trauma, radiculopathy, neuropathy, inflammation, and degenerative changes.[1] Therefore, to make an early diagnosis of TTS, a high index of suspicion must be maintained. In particular, a significant concurrence rate between lumbar radiculopathy and TTS has been reported (4.8%).[16] Moreover, the diagnosis of TTS in DM patients is also important because the clinical features of both diseases are similar.[17] For example, symptoms of DM neuropathy are worse at night and can be described as tingling, coldness, pain, and paraesthesia.[17] We considered that it was challenging to distinguish diabetic neuropathy from TTS. Therefore, we excluded diabetic patients in this examination. However, in case there is a positive Tinel's sign over the tarsal tunnel, Lee et al. demonstrated an 80% chance that surgery will relieve the symptoms in diabetic patients.[18] After we accumulate surgical cases in the future, and it produces satisfactory results, TTS of diabetes patients also possibly indicated to be operated in our department.

The treatment of TTS

The management of TTS remains controversial because of diagnostic uncertainty and lack of clarity about which patients would get benefit from surgical treatment. TTS can be treated nonoperatively or operatively, which is decided generally according to the etiology of the disease, degree of sensory disturbance, and muscle atrophy.[1,2,6] Operative treatment is indicated if nonopretative treatment fails to resolve the patient's symptoms or if a definitive cause of entrapment is recognized.[1,2,6]

Although the surgical outcome for TTS is generally good, some patients experience only partial or no improvement, reported surgical success rates vary from 44% to 96%.[19] It has been reported that surgical management of idiopathic TTS is less effective compared with cases caused by a space-occupying lesion 44). However, Kim et al. reported acceptable surgical results in their 116 surgical cases of idiopathic TTS; it considered to remain controversial. Moreover, negative surgical outcomes are reported to follow a long history of symptom (more than 12 months), history of trauma or sprain, older patients, and heavy working duties (Baba).[6,20]

The average age of our patients was 70.6 ± 27.0 years, not young, and the duration from the onset to surgery was 30.6 ± 23.5 months, not short. However, relatively good results have was obtained. Therefore, we are considering to perform surgery positively for patients with the obvious diagnosis.

As we mentioned above, surgical management for TTS involves TTO, MVD, and RFAH. Some authors reported less invasive surgical method; the nerve was decompressed only by TTO without unnecessary excessive dissection, which produced symptom relief.[19,21] Kohno et al. added NVD to TTO, in which good surgical result was achieved.[22] Other than flexor retinaculum, abductor hallucis fascia is thought to be another stenotic area in the tarsal tunnel.[23] Because these areas possibly cause TTS, some authors recommend that RFAH should be added to TTO and NVC.[23,24] Therefore, we added RFAH to TTO and NVC in cases improved symptoms or disappearance of Tinel's singn were not confirmed by TTO and NVC. In case 3, the symptom improved immediately after surgery, but it worsened afterward. A method of fat insertion between the vessels or a way of wrapping the vascular complex by flexor retinaculum has been reported to prevent adhesion and granulation in the reconstructed tarsal tunnel.[22,25] Such methods may need to be added to prevent a recurrence.

About fluid discharge

In our study, we observed fluid discharge from the operative wound in the first two cases. Therefore, patients were instructed to keep rest as much as possible and discharged after stitch removal, resulted in no fluid discharge from the operative wound. Although we could not find such complications in the literature, it should be noted as the point in the postoperative TTS management.

The limitation of this study includes that the postoperative result was evaluated only 1 month after surgery. Long-term evaluation in more surgical cases should is necessary.

Conclusion

We performed six surgeries for idiopathic TTS with TTO, NVD, and RFAH. In preoperative NCT, we confirmed delayed SCV in all cases, which was helpful to validate physical examination findings. Surgical results for TTS were generally good; however, symptoms recurred in one instance. Some methods to prevent adhesion and granulation in the reconstructed tarsal tunnel should be considered.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kushner S, Reid DC. Medial tarsal tunnel syndrome: A review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1984;6:39–45. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1984.6.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McSweeney SC, Cichero M. Tarsal tunnel syndrome-a narrative literature review. Foot (Edinb) 2015;25:244–50. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frey C, Kerr R. Magnetic resonance imaging and the evaluation of tarsal tunnel syndrome. Foot Ankle. 1993;14:159–64. doi: 10.1177/107110079301400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mondelli M, Morana P, Padua L. An electrophysiological severity scale in tarsal tunnel syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;109:284–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0404.2003.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galardi G, Amadio S, Maderna L, Meraviglia MV, Brunati L, Dal Conte G, et al. Electrophysiologic studies in tarsal tunnel syndrome. Diagnostic reliability of motor distal latency, mixed nerve and sensory nerve conduction studies. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;73:193–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baba H, Wada M, Annen S, Azuchi M, Imura S, Tomita K, et al. The tarsal tunnel syndrome: Evaluation of surgical results using multivariate analysis. Int Orthop. 1997;21:67–71. doi: 10.1007/s002640050122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takakura Y, Kitada C, Sugimoto K, Tanaka Y, Tamai S. Tarsal tunnel syndrome. Causes and results of operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:125–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B1.1991745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torres AL, Ferreira MC. Study of the anatomy of the tibial nerve and its branches in the distal medial leg. Acta Ortop Bras. 2012;20:157–64. doi: 10.1590/S1413-78522012000300005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasunaga T, Kudo Y, Yamashita K, Kinone K, Tachibana S, Nishijima Y. An anatomical study of the calcaneal nerve in the tarsal tunnel. Spinal Surg. 2009;23:164–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keck C. The tarsal-tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg. 1962;44A:180–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam SJ. A tarsal-tunnel syndrome. Lancet. 1962;2:1354–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(62)91024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudes K. Conservative management of a case of tarsal tunnel syndrome. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2010;54:100–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan PE, Kernahan WT., Jr Tarsal tunnel syndrome: An electrodiagnostic and surgical correlation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:96–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh SJ, Arnold TW, Park KH, Kim DE. Electrophysiological improvement following decompression surgery in tarsal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14:407–10. doi: 10.1002/mus.880140504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turan I, Rivero-Melián C, Guntner P, Rolf C. Tarsal tunnel syndrome. Outcome of surgery in longstanding cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;343:151–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng C, Zhu Y, Jiang J, Ma X, Lu F, Jin X, et al. The prevalence of tarsal tunnel syndrome in patients with lumbosacral radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:895–905. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ormeci T, Mahirogulları M, Aysal F. Tarsal tunnel syndrome masked by painful diabetic polyneuropathy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;15:103–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CH, Dellon AL. Prognostic ability of tinel sign in determining outcome for decompression surgery in diabetic and nondiabetic neuropathy. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;53:523–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000141379.55618.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim K, Isu T, Morimoto D, Sasamori T, Sugawara A, Chiba Y, et al. Neurovascular bundle decompression without excessive dissection for tarsal tunnel syndrome. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2014;54:901–6. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2014-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raikin SM, Minnich JM. Failed tarsal tunnel syndrome surgery. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8:159–74. doi: 10.1016/s1083-7515(02)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiStefano V, Sack JT, Whittaker R, Nixon JE. Tarsal-tunnel syndrome. Review of the literature and two case reports. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1972;88:76–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohno M, Takahashi H, Segawa H, Sano K. Neurovascular decompression for idiopathic tarsal tunnel syndrome: Technical note. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:87–90. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong JT, Lee SW, Son BC, Sano K. Surgical experiences of the tarsal tunnel syndrome. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2004;36:443–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heimkes B, Posel P, Stotz S, Wolf K. The proximal and distal tarsal tunnel syndromes. An anatomical study. Int Orthop. 1987;11:193–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00271447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagayasu T, Tachibana S, Kudo Y, Chotoku S. Vascular wrapping using the flexor retinaculum as a new method for tarsal tunnel syndrome. Spinal Surg. 2011;25:209–11. [Google Scholar]