Abstract

Posttraumatic cerebral infarction (PTCI) is a devastating complication of traumatic brain injury. It is usually seen in patients with moderate-to-severe head injury with a reported incidence of 1.9%–10.4%. Brain shift associated with the traumatic intracranial space-occupying lesions with or without severe cerebral edema is the most common mechanism underlying the PTCI. Without associated direct vascular injury, isolated PTCI is very rare after mild head injury. Such cases of PTCI following mild head injury have been reported in children in whom they usually affect the gangliocapsular region supplied by the lenticulostriate arteries. Such infarcts in adults are extremely rare. Although the exact pathogenesis is not clear, vasospasm or shearing-associated intimal tear is proposed to be the cause for this infarct. Other common causes of cerebral infarction should be ruled out before making such a diagnosis. Unlike PTCI associated with a severe head injury, cerebral infarction following mild head injury is expected to have a better neurological outcome.

Keywords: Cerebral infarction, mild head injury, splenium, vasospasm

Introduction

Posttraumatic cerebral infarct (PTCI) is one of the most devastating complications of the head injury. The incidence of PTCI has been reported in the range of 1.9%–10.4%.[1,2,3,4] PTCI has also been thought to be associated with high mortality rate and poor neurological outcome after head injury as compared to those without infarction.[1,5] It can involve one or more territories of the major intracranial vessels, watershed areas, and areas supplied by perforators such as lenticulostriate–thalamoperforating arteries or cortical areas directly adjacent to the posttraumatic intracranial hematoma. Infarction typically occurs in patients with moderate-to-severe head injuries. It is extremely rare following mild head injury.[4,5] In this article, we reported a case of PTCI in an unusual area following mild head injury in an adult.

Methods

Clinical presentation, investigations, and radiological features of an adult male admitted to our hospital following mild head injury were reviewed. Published case series in the literature have been analyzed and reported here.

Clinical Presentation

A 24-year-old male reported in our outpatient department with difficulty in walking, following roadside accident. While riding a two-wheeler 2 days before at night, he hit against a tree and fell. He had a transient loss of consciousness (LOC). He was given first aid at a local hospital and discharged following morning as he was asymptomatic. The next day, he noticed a sudden onset of difficulty in walking. He felt severe unsteadiness and tendency to fall while walking. He returned to hospital and was evaluated with computed tomographic (CT) scan of the head. It showed very minimal speck of contusion in the cortex of the right posterior medial temporal lobe [Figure 1a]. He was referred to our center for further management.

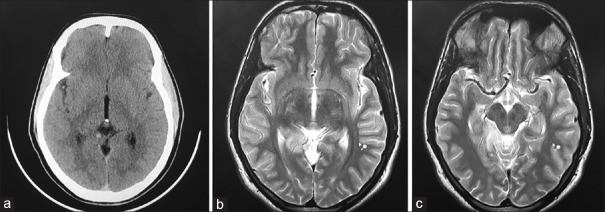

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging images of the brain. (a) Axial computed tomographic of the head shows speck of contusion in the cortex of posterior medial part of the right temporal lobe. (b and c) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging sequence shows hyperintense signal in the posterior medial part of the right temporal lobe

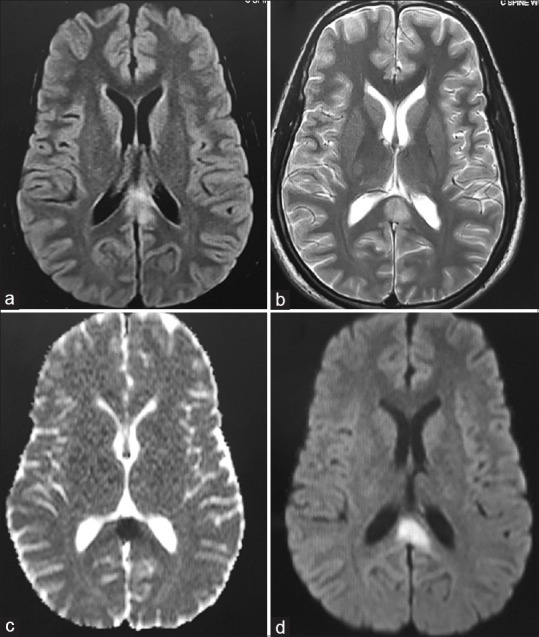

On examination, his Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15/15, and vital signs were stable. Cranial nerve examination was unremarkable except for mild dysarthria. Motor examination showed mild lower limb spasticity, brisk lower limb deep tendon reflexes, and normal reflexes in the upper limbs. His gait was spastic, slow, and short stepped with a broad base. He had severe ataxia and could not walk without looking at his legs. The sensory examination was normal. He was initially evaluated with CT scan of the brain and spine. It showed resolving speck of contusion as mentioned before. Spine imaging did not show any evidence of fracture or instability. He was further evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. MRI of the brain showed a well-defined hyperintense signal involving the posterior medial temporal lobe [Figure 1b and c] and the splenium of the corpus callosum in T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences [Figure 2a and b]. Diffusion-weighted image (DWI) showed hyperintense signal in the splenium with low values in corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient which suggested the possibility of an acute infarct in the splenium [Figure 2c and d]. MR angiogram did not show any evidence of arterial dissection or vascular occlusion. His cardiac workup was normal. Prothrombotic workup including protein C and S, homocysteine, antithrombin III, and D-dimer was normal. He was also negative for antinuclear antibody, anti-Ds DNA antibody, and antiphospholipid antibodies. He was started on antiepileptic and antiplatelet drugs. Over a period of 4 weeks, his ataxic gait improved to normal.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. (a and b) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and T2-weighted images show hyperintense signal in the splenium of corpus callosum. (c and d) Diffusion-weighted image and corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient map show area of diffusion restriction in the splenium suggestive of an acute infarct

Discussion

PTCI is a rare but dreaded complication of the head injury. The incidence of PTCI could be higher than the previously reported incidence in the literature.[3] It has been reported as high as 19.1% in moderate-to-severe head injury patients.[6] The underlying mechanism for PTCI could be vascular stretching and compression, direct vascular injury, cerebral vasospasm, embolism, and systemic hypotension. Severe cerebral edema associated with midline shift and brain herniation secondary to posttraumatic space-occupying lesions is the most common mechanism underlying PTCI and responsible for 81%–88% of cases.[1,2] Acute subdural hemorrhage (SDH) and extradural hematoma (EDH) are the most common causes leading to PTCI.[1,2,3,4] Herniating brain stretches and compresses the adjacent vessels. Thus, it leads to ischemia and infarct. The most common site of PTCI is the territory of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA).[1,2,3,4,5] Transtentorial herniation of the medial temporal lobe compresses the PCA against the rigid tentorial edge and leads to occipital lobe infarct. This was first reported by Meyer in 1920.[7] Sato et al.[8] reported that only 9% of patients with evidence of transtentorial herniation on CT scan developed occipital lobe infarct. Similarly, subfalcine herniation of cingulate gyrus results in compression of the anterior cerebral artery and its branches. This leads to infarction of paracentral lobule, superior frontal gyrus, and cingulate gyrus.

Cerebral vasospasm secondary to traumatic brain injury (TBI) can also result in PTCI with the incidence ranging from 2% to 41%.[2] It is most prominent in the distal intradural portion of the internal carotid artery.[1,9] Vasospasm has been almost always reported in patients with severe TBI.[10,11] Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is the most common cause of vasospasm after trauma.[12,13] Increased incidence of vasospasm has also been reported in patients with acute SDH, EDH, and intracerebral hemorrhage. Patients with lower GCS score on admission will have a higher incidence of vasospasm, as both are inversely correlated.[10,13] Factors such as SAH, intraventricular hemorrhage, low admission GCS score (<9), and young age (<30 years) have been identified as predictors of posttraumatic vasospasm.[10] Vasospasm usually starts on day 2 and lasts for a shorter duration.[12] In the majority of the patients, clinical deterioration is rare.

Although TBI can be associated with ischemic stroke, it is very rare following mild head injury (GCS 15; LOC <5 min). Only few cases have been reported. The majority of these patients were children and had an ischemic stroke in basal ganglia in the territory of lenticulostriate perforators.[14,15,16] Only one such case of PTCI following mild head injury has been reported in adults. Matsumoto and Yoshida[17] reported a case of cerebellar infarct after mild head injury in a 23-year-old healthy adult. In our case, mild head injury resulted in isolated splenial infarction, and the other PCA territories were spared. The PCA territory stroke after the head injury is usually associated with vertebral artery (VA) dissection. Without VA dissection, spontaneous infarcts are extremely rare following trauma.

Vascular supply of the splenium is provided by multiple branches which can vary in each individual. Anterior pericallosal artery (40%), posterior pericallosal artery (88%), and accessory pericallosal artery (24%) are the major feeders of the splenium.[18] The terminal perforators of these vessels anastomose with homologous neighboring vessels to form a characteristic intrinsic vascular network. Splenial infarction is rare and usually associated with infarction of body of the corpus callosum and adjacent cortical areas. The common clinical features of splenial pathology are confusion, delirium, gait ataxia or truncal ataxia, new-onset seizure, dysarthria, increased muscle tone, and hemispheric disconnection syndromes such as alien left hand, pseudoneglect, astereognosis, and visual apraxia.[19] Our patient presented with acute onset ataxic gait, lower limb hypertonia, and dysarthria in the decreasing order of severity.

The exact mechanism underlying such infarcts is unclear. Vasospasm has been proposed as the common pathogenic mechanism.[9,12,13] The other possible mechanism is shearing-associated vascular injury.[9,12,13,14] Brain movement following impact causes stretching and shearing effect on the vessels due to high inertia. This results in endothelial injury, fibrin accumulation followed by thrombus formation leading to vessel occlusion. Both these mechanisms cause cerebral ischemia after an asymptomatic latency period.

Isolated infarction of the splenium, in this case, suggests involvement of the terminal branches rather than the proximal PCA or its named branches. Acute onset of new neurological deficit 2 days after the injury suggests that vasospasm could be the likely mechanism underlying this infarct. PTCI should be suspected in any patient who develops new deficits unexplained by the severity of the head trauma. Recognition of chronological association between the trauma and neurological deficits is the key to the diagnosis. The latency period between accident and the onset of focal neurological deficit may vary from 15 min to 72 h.[14] It is also essential to rule out direct vascular injuries like dissection, cardiac diseases, prothrombotic conditions, and vasculopathy.

MRI brain with DWI sequences is the investigation of choice like any other patient with suspected stroke.[20,16] The important differential diagnosis is diffuse axonal injury (DAI). DAI also shows similar hyperintense signal changes in DWI sequence.[21] Infarction and DAI lesions are often difficult to differentiate from one another. In our case, the typical delayed onset acute neurological deficit suggests vasospasm-induced infarction as the underlying pathology. The conventional angiogram may demonstrate the underlying vasospasm of the involved vessel.[17] Treatment is mostly supportive with early rehabilitation. Aspirin may be helpful for secondary prevention.[15] Unlike PTCI following severe head injury, these infarcts have better neurological outcome, and prompt neurological recovery can be expected.[15,16]

Conclusion

PTCI does occur following mild head injury in the absence of brain shifts, although they are extremely rare. PTCI should be suspected in any patient who develops delayed neurological deficits out of proportion to the severity of the head injury. In the absence of posttraumatic arterial dissection or other direct vascular injuries, unsuspected cardiac conditions, prothrombotic diseases, and vasculopathy should be ruled out before arriving at such a diagnosis. MRI of the brain with DWI is the diagnostic method of choice. Neurological outcome is usually favorable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mirvis SE, Wolf AL, Numaguchi Y, Corradino G, Joslyn JN. Posttraumatic cerebral infarction diagnosed by CT: Prevalence, origin, and outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11:355–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Server A, Dullerud R, Haakonsen M, Nakstad PH, Johnsen UL, Magnaes B. Post-traumatic cerebral infarction. Neuroimaging findings, etiology and outcome. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:254–60. doi: 10.1080/028418501127346792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tawil I, Stein DM, Mirvis SE, Scalea TM. Posttraumatic cerebral infarction: Incidence, outcome, and risk factors. J Trauma. 2008;64:849–53. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318160c08a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian HL, Geng Z, Cui YH, Hu J, Xu T, Cao HL, et al. Risk factors for posttraumatic cerebral infarction in patients with moderate or severe head trauma. Neurosurg Rev. 2008;31:431–6. doi: 10.1007/s10143-008-0153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae DH, Choi KS, Yi HJ, Chun HJ, Ko Y, Bak KH. Cerebral infarction after traumatic brain injury: Incidence and risk factors. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2014;10:35–40. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2014.10.2.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marino R, Gasparotti R, Pinelli L, Manzoni D, Gritti P, Mardighian D, et al. Posttraumatic cerebral infarction in patients with moderate or severe head trauma. Neurology. 2006;67:1165–71. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238081.35281.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer A. Herniation of the brain. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1920;4:387–400. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato M, Tanaka S, Kohama A, Fujii C. Occipital lobe infarction caused by tentorial herniation. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:300–5. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198603000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macpherson P, Graham DI. Arterial spasm and slowing of the cerebral circulation in the ischaemia of head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1973;36:1069–72. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.36.6.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Mufti F, Amuluru K, Changa A, Lander M, Patel N, Wajswol E, et al. Traumatic brain injury and intracranial hemorrhage-induced cerebral vasospasm: A systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;43:E14. doi: 10.3171/2017.8.FOCUS17431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandera M, Larysz D, Wojtacha M. Changes in cerebral hemodynamics assessed by transcranial Doppler ultrasonography in children after head injury. Childs Nerv Syst. 2002;18:124–8. doi: 10.1007/s00381-002-0572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin NA, Doberstein C, Alexander M, Khanna R, Benalcazar H, Alsina G, et al. Posttraumatic cerebral arterial spasm. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12:897–901. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zubkov AY, Lewis AI, Raila FA, Zhang J, Parent AD. Risk factors for the development of post-traumatic cerebral vasospasm. Surg Neurol. 2000;53:126–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(99)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kieslich M, Fiedler A, Heller C, Kreuz W, Jacobi G. Minor head injury as cause and co-factor in the aetiology of stroke in childhood: A report of eight cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:13–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn JY, Han IB, Chung YS, Yoon PH, Kim SH. Posttraumatic infarction in the territory supplied by the lateral lenticulostriate artery after minor head injury. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:1493–6. doi: 10.1007/s00381-006-0157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaffer L, Rich PM, Pohl KR, Ganesan V. Can mild head injury cause ischaemic stroke? Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:267–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto H, Yoshida Y. Posttraumatic cerebellar infarction after repeated sport-related minor head injuries in a young adult: A case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2015;55:179–82. doi: 10.2176/nmc.cr.2014-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahilogullari G, Comert A, Ozdemir M, Brohi RA, Ozgural O, Esmer AF, et al. Arterial vascularization patterns of the splenium: An anatomical study. Clin Anat. 2013;26:675–81. doi: 10.1002/ca.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doherty MJ, Jayadev S, Watson NF, Konchada RS, Hallam DK. Clinical implications of splenium magnetic resonance imaging signal changes. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:433–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kargl S, Parsaei B, Sekyra P, Wurm J, Pumberger W. Ischemic stroke after minor head trauma in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2012;22:168–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1287785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezaki Y, Tsutsumi K, Morikawa M, Nagata I. Role of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in diffuse axonal injury. Acta Radiol. 2006;47:733–40. doi: 10.1080/02841850600771486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]