Abstract

Bacterial type III secretion systems (T3SSs) play an important role in pathogenesis of Gram-negative infections. Enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli contain a well-defined T3SS but in addition a second T3SS termed E. coli T3SS 2 (ETT2) has been described in a number of strains of E. coli. The majority of pathogenic E. coli contain elements of a genetic locus encoding ETT2, but which has undergone significant mutational attrition rendering it without predicted function. Only a very few strains have been reported to contain an intact ETT2 locus. To investigate the occurrence of the ETT2 locus in strains of human pathogenic E. coli, we carried out genomic sequencing of 162 isolates obtained from patient blood cultures in Scotland. We found that 22 of 26 sequence type (ST) 69 isolates from this collection contained an intact ETT2 together with an associated eip locus which encodes putative secreted ETT2 effectors as well as eilA, a gene encoding a putative transcriptional regulator of ETT2 associated genes. Using a reporter gene for eilA activation, we defined conditions under which this gene was differentially activated. Analysis of published E. coli genomes with worldwide representation showed that ST69 contained an intact ETT2 in these strains as well. The conservation of the genes encoding ETT2 in human pathogenic ST69 strains strongly suggests it has importance in infection, although its exact functional role remains obscure.

Subject terms: Bacterial genetics, Genetics research

Introduction

Pathogenic bacteria possess a number of different secretion systems that facilitate host infection as well as interbacterial competition1. One of these is the type III secretion system (T3SS), which is found in a number of different Gram-negative pathogens and is key to the ability of these microbes to cause disease2–4. Broadly, T3SS comprise two elements: a highly conserved multiprotein structural complex that forms the conduit between the bacterial and the host cell; and various effector proteins that are translocated through this channel. Genes encoding the T3SS channel, or needle complex, are contained within pathogenicity islands comprised of a single cluster of genes5,6. Genes encoding effectors are more widely spread within the genome and vary greatly between different bacterial species.

Certain strains of Escherichia coli possess a well-defined T3SS, notably enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). This T3SS is encoded on the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) and in concert with its secreted effectors, produces the characteristic attaching and effacing lesions that mediate close attachment of the pathogen with the intestinal epithelial wall7. Whole genome sequencing of strains of EHEC revealed the presence of a putative additional T3SS8,9, which has been termed E. coli T3SS 2 (ETT2). The gene cluster encoding this additional T3SS shows significant homology to the SPI-1 T3SS of Salmonella serotype Typihimurium10,11. However, unlike the LEE, the T3SS first described in EHEC and EPEC, there do not appear to be any putative effector proteins encoded within ETT2 and there are some differences in the structural genes present as well11. Compared to the SPI1 T3SS of S. Typhimurium, the ETT2 apparently lacks homologues of genes encoding the needle tip complex, SipBCD. Further studies attempted to delineate the frequency with which this ETT2 locus was found in different E. coli strains12–14. However, a study by Ren et al.15 showed that although the ETT2 locus was present in many lineages of E. coli, it had undergone extensive mutational attrition. The phylogenetic analysis showed that ETT2 was absent in what is thought to be the oldest phylogroup of E. coli, B216,17, which contains many uropathogenic E. coli, but had been acquired by the divergence of the next oldest phylogroup, D. Analysis showed multiple inactivating mutations were present within the locus, which would render the T3SS functionless, including the ETT2 locus in the EHEC O157 strains in which it was originally described. However, a complete and potentially fully functional ETT2 was found in the enteroaggregative E. coli O42 (EAEC O42) strain; other E. coli strains analysed either had no ETT2 locus, or it had undergone extensive deletion and/or mutational inactivation. Ren et al. also showed that E. coli strains with the most intact ETT2 locus also carried an additional T3SS-like island adjacent to the selC tRNA gene, the eip locus, which encoded homologues of translocated proteins from the Salmonella pathogenicity island I (Spi-1) T3SS, as well as genes encoding a transcriptional regulator (eilA), a chaperone (eicA) and an outer membrane invasion/intimin-like protein (eaeX)15,18.

Functional effects of ETT2 remain unclear. Mutational analysis of the ETT2 cluster in an avian pathogenic E. coli showed it had reduced virulence, even though the cluster had undergone mutational attrition and could not encode a functional T3SS, suggesting potential alternative roles in pathogenesis19. Other studies have also suggested a role for proteins encoded in the ETT2 in virulence of avian pathogenic E. coli and K1 strains20–22. A recent study examined the role of the putative transcriptional regulator gene eilA at the selC locus in EAEC strain O4218. This demonstrated that eilA was responsible for regulating transcription of genes within the selC locus, as well as eivF and eivA within the ETT2 locus. Mutants lacking eilA were less adherent to epithelial cells and had reduced biofilm formation; this phenotype was also observed for mutants in the eaeX gene which encodes the invasin/intimin homologue. This suggested important functional roles of the selC and ETT2 loci in pathogenesis of this strain of E. coli.

Hitherto, there is no evidence of intact ETT2 in human pathogenic strains of E. coli other than a few strains of EAEC. However, given the findings described above, we hypothesised that ETT2 might be of importance in human infections caused by E. coli phylogroups other than B2. In particular, given the roles of T3SSs in attachment, invasion and immune evasion, we hypothesised that strains with an intact ETT2 might be found within invasive bloodstream isolates of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli, where the ETT2 might have allowed the organism to overcome epithelial barriers and immune clearance. Thus, we set out to determine whether an intact ETT2 was present in a collection of invasive bloodstream isolates of E. coli. We have studied 162 isolates of E. coli isolated from bacteremic patients in Scotland from 2013 and 2015, which we have subjected to whole genome sequencing. Within this group, we identified 26 strains of E. coli sequence type (ST) 69, of phylogroup D, which were largely derived from community-acquired sources. Virtually all of these strains had a completely intact ETT2 and selC locus, with no inactivating mutations. Similarly, intact ETT2/selC loci were also found in some minor ST types in our collection. The eilA transcriptional regulator was functional in these strains. Analysis of E. coli strains with worldwide representation also showed that ST69 contained an intact ETT2 in these strains as well. Our results show that an intact ETT2 locus is widely present in human pathogenic E. coli ST69 strains, suggesting a functional role for this cryptic T3SS in human disease caused by this sequence type.

Results

ETT2 locus within Scottish E. coli blood stream isolates

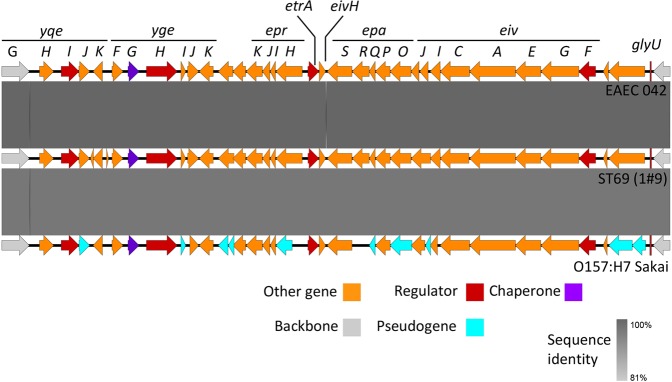

We have performed whole genome sequencing and analysis of 162 isolates of Escherichia coli obtained from blood cultures of patients within Scotland in 2013 and 201523. Sequence comparisons with other isolates of E. coli showed that strains belonging to ST69 contained an intact ETT2 locus. The gene content of this locus from one of these ST69 strains, ST69 1#9, was compared to the complete ETT2 found in enteroaggregative E. coli strain 042 (EAEC 042) and the degenerate ETT2 found in E. coli O157:H7 Sakai (Fig. 1). An ETT2 locus in this ST69 strain was found in the ~30 kb region spanning the yqeG gene and the tRNA gene gluU with over 98% identity to the ETT2 locus in EAEC 042. Importantly, this locus did not contain any of the deletions, insertions or inactivating mutations found in the E. coli O157:H7 Sakai strain and thus was characterised as intact.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of the ETT2 locus between EAEC 042, ST69 (1#9) and O157:H7 Sakai. Degree of identity is shown by the level of grey shading as indicated. Genes are colour coded according to putative function as shown.

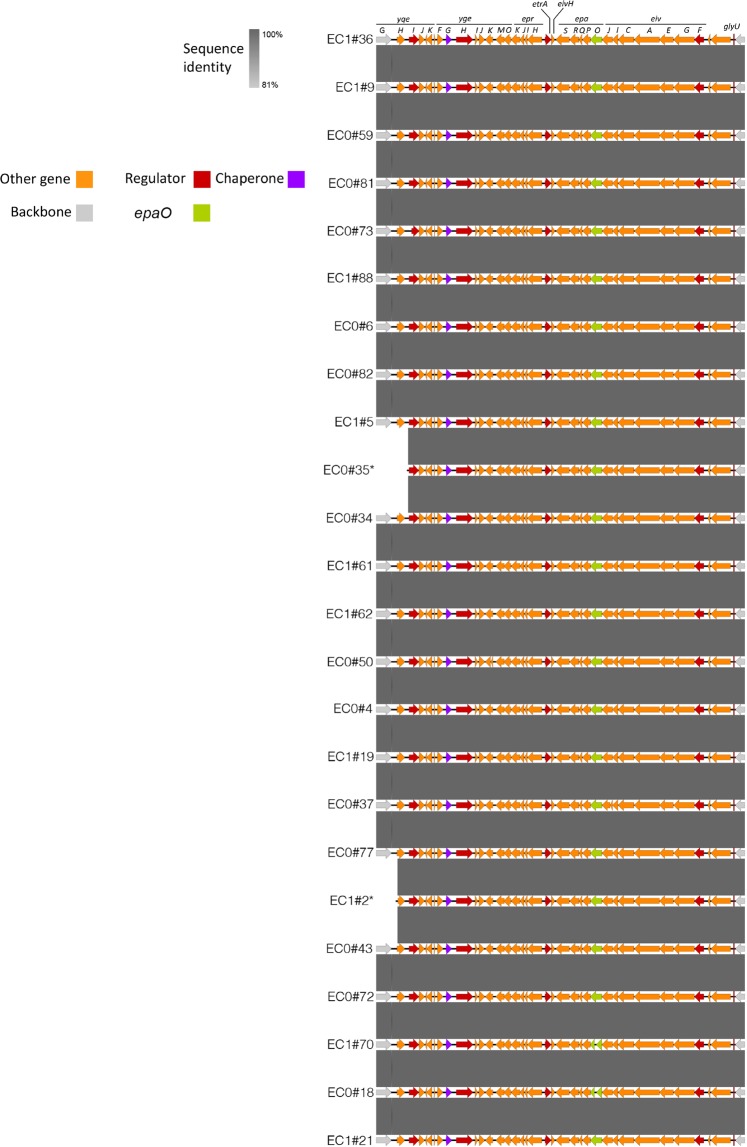

We extended this analysis to compare all of the ST69 strains in our collection over this region. Of 26 ST69 genomes sequenced, 24 were assembled in one contig covering this region, shown compared to each other in Fig. 2. In all these assemblies, there was a greater than 95% identity between the sequences and the reference genome of the ETT2 in EAEC 042 (Table 1). Two strains appeared to lack the extreme left-hand end of the complete ETT2 locus (ECO#35 and EC1#2), and two strains had a stop codon in the epaO gene at the same site as noted for E. coli O157:H7 Sakai (EC1#70 and ECO1#18; gene highlighted in green); no other ST69 strains had any inactivating mutations.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the ETT2 operon in 24 ST69 strains. Degree of identity is shown by the level of grey shading as indicated. Genes are colour coded according to putative function as shown. The epaO gene is shown green.

Table 1.

Similarities of length and identity between the ETT2 and eip loci in the strains indicated.

| ST69 Samples | ST Type | ETT2 | eip | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hits | Identity | Length | Bit score | Hits | Identity | Length | Bit score | ||

| EC0_4 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_59 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_81 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_82 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC1_19 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC1_36 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC1_9 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_50 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48477 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_77 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21981 |

| EC1_5 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21981 |

| EC1_61 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48477 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_6 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21976 |

| EC1_88 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48483 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21976 |

| EC0_34 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48471 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_18 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48466 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_72 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48466 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC1_21 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48466 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC1_70 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48466 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC0_43 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27164 | 48468 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21976 |

| EC0_73 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27173 | 48436 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21987 |

| EC1_2 | ST69 | 2 | 98.9% | 27130 | 48392 | 34 | 95.3% | 13862 | 21981 |

| EC0_37 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48471 | 35 | 95.3% | 13812 | 21872 |

| EC1_62 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 27163 | 48471 | 33 | 95.5% | 13573 | 21638 |

| EC0_35 | ST69 | 1 | 98.9% | 26248 | 46793 | 35 | 94.9% | 12839 | 20092 |

Conservation was determined using BLAST against the EAEC 042 reference.

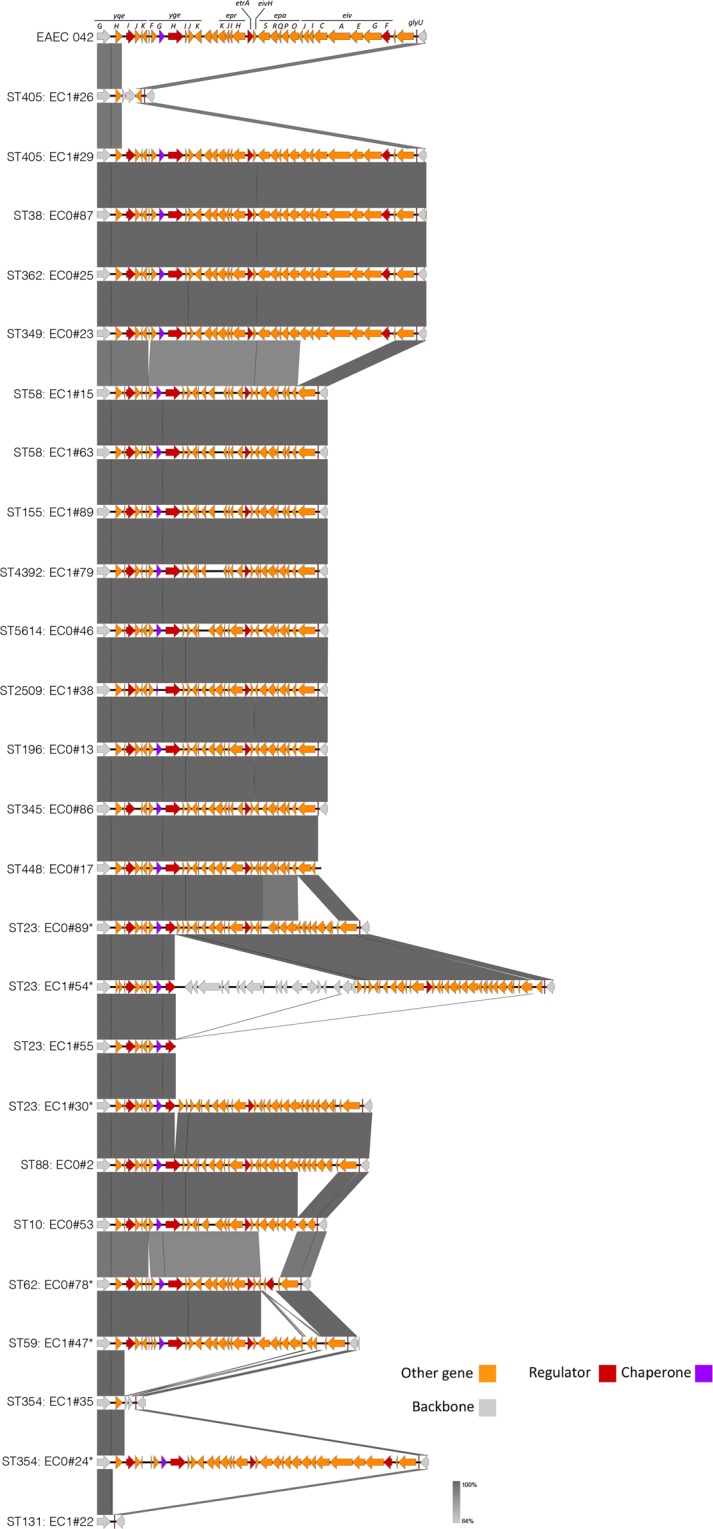

Next, we analysed other STs within our collection of bacteremic isolates for the presence of the ETT2 locus (Fig. 3). 4 non-ST69 isolates contained an intact ETT2 region, belonging to ST405, 38, 362 and 349. BLAST percentage identity and length coverage of the ETT2 from these strains to EAEC 042 is shown in Table 2; all are closely related to ST69 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Other strains showed variable loss and/or degradation of the locus as previously described. Notably, none of the common epidemic strain ST131 (phylogroup B2) contains any elements of this ETT2 region – one representative example is shown at the bottom of Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of elements of the ETT2 locus found in non-ST69 strains. Degree of identity is shown by the level of grey shading as indicated. Genes are colour coded according to putative function as shown. Genes unrelated to the ETT2 locus genes are coloured grey.

Table 2.

Similarities of the ETT2 locus between the strains indicated.

| Sample | Strain type | Hits | Identity | Length | Bit score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC0_23 | ST349 | 1 | 98.9% | 27161 | 48447 |

| EC0_87 | ST38 | 1 | 98.8% | 27160 | 48268 |

| EC1_29 | ST405 | 1 | 98.7% | 27161 | 48220 |

| EC0_25 | ST362 | 1 | 98.7% | 27161 | 48172 |

Conservation was determined using BLAST against the EAEC 042 reference.

selC/eip locus within Scottish blood culture isolates

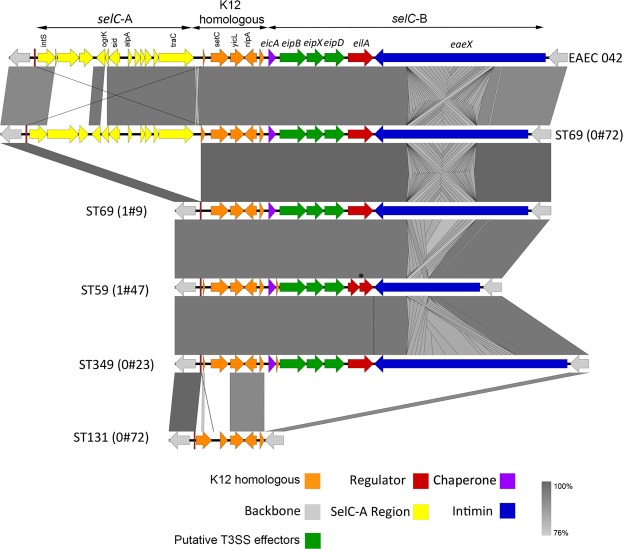

Closely associated with an intact ETT2 region is a group of genes related to type III secretion effectors adjacent to the selC tRNA gene15,18. Two distinct genome insertions were noted at this site: selC-A and selC-B, as defined and described by Sheikh et al.18. selC-A contains mainly phage related genes. selC-B contains homologues of putative type III secretion effectors (eipB, eipX and eipD), a putative type III effector chaperone, eicA, a transcriptional regulator eilA, and a gene eaeX, which encodes a large protein containing bacterial immunoglobulin repeats with homology to outer membrane adhesion/invasion protein intimin found in Yersinia spp. as well as intimins of invasive E. coli strains. Comparison of this region with representative ST69 and other strains compared to EAEC 042 is shown in Fig. 4. In EAEC 042 selC-A lies between an intact copy of the selC gene and a 21 bp direct repeat of the 3′ end of the selC tRNA gene. Three backbone genes then intervene (setC, yicL, nlpA) before the region of the selC-B region. All ST69 strains in our isolates contained the selC-B locus with over 95% identity to the EAEC 042 region (Table 1). The variations were found within the central domain of the EaeX product, which contains the bacterial immunoglobulin (Big) repeats, with variation in the number of repeats contained within this domain. A similar region was also found in non-ST69 isolates; one ST59 strain and one ST349 strain also possessed the ETT2 locus. These major differences in the number of Big repeats between the strains is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. Domain analysis with ScanProsite also identified an N terminal LYSM domain, a module that recognizes polysaccharides containing N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues including peptidoglycan24. The Big repeat number was conserved within the ST69 strains suggesting that once the eaeX gene was acquired within this strain it has been maintained; there are too few isolates with the eaeX gene from other STs to be able to comment on its conservation or otherwise in these groups. As with the ETT2 locus, the selC-B region was entirely missing in ST131 isolates. The selC-A region was largely absent from our isolates but was partially present in one of the ST69 isolates (ECO#72, Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the selC operon in different strains. Degree of identity is shown by the level of grey shading as indicated. Genes are colour coded according to putative function as shown. *Shows the position of a frameshift mutation in the eilA gene of sample 1#47 (ST59).

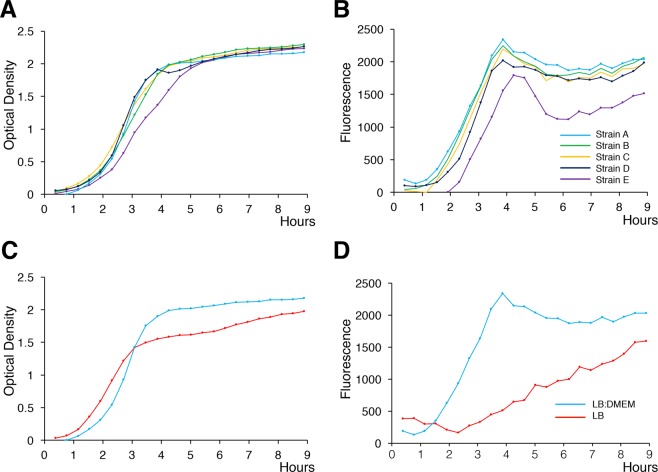

EilA has been shown to regulate genes within the selC-B region as well as the ETT2 island adjacent to the tRNA glyU gene18. We wished to determine if we could define conditions under which eilA was transcriptionally active, and hence activating the ETT2 island. We constructed a reporter gene containing 500 bp of upstream sequence from the eilA gene found in the neonatal meningitis associated E. coli strain CE1025. Analysis of this region in strain EC1#2 used for the detailed reporter expression studies showed 96.4% identity with the same region in CE10 and with perfect conservation of putative binding sites for purR, fnr, argr2, argR and a 7/8 nucleotide match to a putative site for rpoS17. Using this reporter in 5 of our ST69 isolates containing the ETT2 locus, we could readily detect reporter gene activity that peaked in the late log phase of growth in equal parts LB and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (LB:DMEM media) (Fig. 5A,B). Previous studies of transcriptional activation of the LEE have shown this is maximal in less rich media designed for growth of eukaryotic cells such as DMEM compared to the rich medium LB26,27. Following optimization of growth in different media, we compared transcriptional activity of the eilA reporter construct in an ST69 strain grown in LB alone compared to the 1: 1 mixture of LB and DMEM (Fig. 5C,D). Growth in the different media was not significantly different but induction of the promoter was much more marked in the LB:DMEM mix. Transcription of eilA and two other putatively co-regulated genes was confirmed using qPCR at one time point; however, detection was at the limits of detectability and there was no significant difference between transcript levels in bacteria grown in LB or LB:DMEM (Supplementary Fig. S3). Given the short half-life of bacterial mRNAs of the order of 2–10 minutes28, we feel the reporter assay is a more sensitive and accurate measurement of eilA promoter activity. In an attempt to identify proteins potentially secreted into the growth media by ETT2, we compared the pattern of secreted proteins from an ST69 strain with intact ETT2 between the two different media but we did not identify any putative T3SS secreted proteins or secreted components of the T3SS structural domains (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Activity of the eilA reporter in different strains and media. (A,B) Graphs show growth (Optical Density, panels A) and reporter activity (GFP fluorescence, panels B) at the times indicated. The strains are: EC1#2 (A), EC1#19 (B), EC1#5 (C), EC1#21 (D), and EC1#9 (E), all grown in LB:DMEM mixture. Each point is the mean of a triplicate determination; error bars (sem) are contained within the points. (C,D) strain EC1#2 is grown in the different media as indicated.

Presence of ETT2 and selC/eip locus within worldwide collection of E. coli

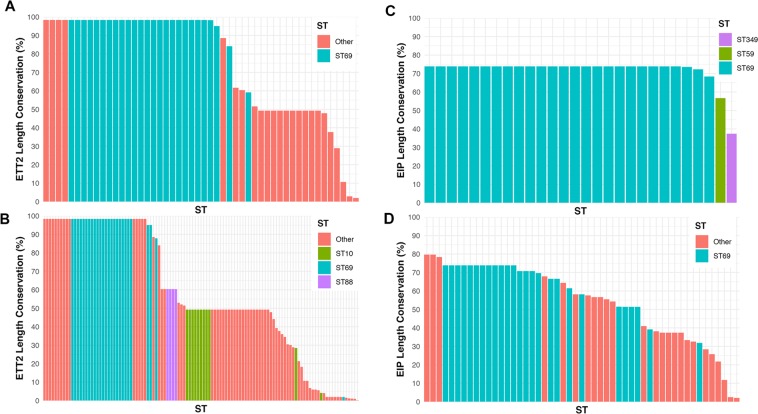

In order to ascertain whether the intact ETT2 and selC/Eip loci within ST69 strains was specific to Scotland or more widespread, we analysed the genomes of E. coli available from public depositories with worldwide representation. We identified 269 strains with full sequence data (Supplementary Table S1). The distribution of STs within this group compared to those within the Scottish blood culture isolates is shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. The major STs within both groups are very similar: ST131, ST69, ST73, ST95, ST12 and ST127. Analysis of the length conservation of the ETT2 locus within these sequences is shown in Fig. 6 for both the local and the global sequences. Of 26 ST69 sequences within the global collection (Fig. 6B), 22 had a 98.4% length identity to the reference ETT2 locus in the EAEC 042 strain, two strains had a 95.1% match, and one had a 87.9% match; one ST69 strain had virtually deleted the locus (2.0% length identity). Of the non-ST69 strains that showed >95% conservation of the ETT2 locus, there was no ST present with more than 4 members. Two ST38 strains were included in this group, also found within our collection of Scottish bacteremic strains with high conservation of the ETT2 locus. The length conservation of the selC/Eip locus (over the selC-B region) for the local and global E. coli strains is shown in Fig. 6C,D. 19/26 (73%) of the ST69 strains had a >60% length conservation compared to the reference EAEC 042 strain. The major differences in length of the different strains from the EAEC reference were in the eaeX gene, which contain different numbers of the bacterial immunoglobulin-like repeats. As for the ETT2 locus, the ST131 strains did not contain any of the selC-B locus either.

Figure 6.

Length conservation of the ETT and selC/Eip locus in different strains of E. coli compared to the reference strain, EAEC 042. Data from the local Scottish strains (panels A and C) and global data (panels B and D) are shown. (A,B) are the comparisons for the ETT2 locus and (C,D) are for the selC/Eip locus. STs with fewer than 4 representatives are classed as Other in panels A, B, and D.

Discussion

We report here the presence of genomic regions encoding ETT2 and associated putative T3SS effectors within E. coli ST69 isolates from bacteremic patients within Scotland. In virtually all of the isolates, the two regions encoding these proteins contained a full complement of genes with no deletion, insertions or inactivating mutations suggesting that the ETT2 and associated effectors could be functionally active. This is in contrast to the vast majority of ETT2 sequences reported to date, which have undergone significant mutational attrition. The conserved nature of the ETT2 sequences reported here strongly suggests that there has been selection pressure for these regions to be conserved within the ST69 lineage.

ST69 belongs to phylogroup D of the E. coli lineage. We did not detect ETT2 in E. coli of ST131, which is phylogroup B2. Although not completely clear, our data are in agreement with the origin of the different phylogroups as discussed by Ren et al.15, who suggest that ETT2 is not present in the ancestral B2 phylogroup but was acquired at some point in the evolution of the D group. Feature free profiling also supports the view that B2 is the ancestral group, with phylogroup D diverging thereafter16. Subsequent lineages show significant mutational attrition of the ETT2 locus, although our data show strong conservation in the isolates of ST69 studied here. ST69 is one of the common STs found in bloodstream isolates of E. coli. In our collection, ST69 was mostly found in infections acquired from the community23. The natural environment of these human pathogenic E. coli is the gastrointestinal tract; passage into blood is predominantly through ascending infection into the bladder and renal tract. Evolutionary pressure to retain ETT2 might therefore have arisen through its ability to provide a selective advantage in gut colonization and/or in infection of the renal tract. Importantly, we also found highly significant conservation of the ETT2 and selC/Eip loci in E. coli strains from global collections, showing that the preservation of these regions is not confined to local Scottish strains.

We noted that two strains had a stop codon in the epaO gene at the same site as noted for E. coli O157:H7 Sakai (EC1#70 and ECO1#18). epaO is homologous to the Salmonella Typhimurium T3SS gene, spaO13, which encodes a protein that forms part of the cytoplasmic sorting platform essential for energizing and sorting substrates for delivery to the needle complex29. spaO is essential for type III secretion in S. Typhimurium30. Recent work has shown that spaO produces two protein products by tandem translation: a full-length protein and a shorter C terminal portion that is translated from an internal ribosome binding site and alternative initiator codon31. Both are needed for functionality of the T3SS in S. Typhimurium, so the loss of the full-length product of epaO will likely also render the ETT2 non-functional.

The functional effects of ETT2 remain obscure. In strains with a disrupted ETT2, genetic deletion does seem to confer a changed phenotype, with defective invasion and survival within brain microvascular endothelial cells22; this suggests even these apparently non-functional regions have a pathogenic role or can be complemented by other gene products. Additionally, experiments in avian strains with ETT2 also suggest a functional role for the ETT2 in pathogenesis20. ETT2 has also been implicated in the control of gene expression from the locus of enterocyte effacement in enterohemorrhagic E. coli O15732. We could not identify any putative secreted ETT2 substrates from the ST69 strains reported here. A recent study of E. coli serotype O2 that causes avian coccobacillosis also failed to identify potential ETT2 secreted proteins, but did find that the intact ETT2 mediated expression and secretion of flagellar proteins, as well as other changes in cell surface behaviour33. It may be that the conditions under which the ETT2 mediates secretion have not been identified, or that it carries out different functions.

In summary therefore, we show here that the ST69 strain of human pathogenic E. coli has an intact genetic locus for ETT2 and associated proteins. The preservation of these sequences in the ST69 strain suggest that its functional effects might confer a significant selection advantage. However, its exact functional effects remain obscure.

Methods

Sequencing and genome analysis

Whole genome sequencing of 162 strains of E. coli from human clinical samples were collected and sequenced as previously described23. Mean Phred score of the reads was 34.57 (99.9% base call accuracy), mean N50 of the assemblies was 355, 277, and the mean number of contigs assembled per sample was 62.6. The data for the individual samples is shown in Supplementary Table S2.

For pangenome analysis, Illumina reads were assembled using the de novo assembler SPAdes34. After filtering contigs less than 100 bp long, genomes were annotated for genus Escherichia using PROKKA35 with default parameters. Annotated genomes were then studied using the pan-genome pipeline Roary36 using minimum blastp identity as 95% and percentage of isolates to be in the core genome taken as 99%. The presence and absence of genes in accessory genome (>5% and <99% isolates) was used to create the binary tree. The ETT2 locus genes were identified using BLAST against the ETT2 region of EAEC 042 strain.

Comparison between selected sequences were made and visualised using Easyfig37. MLST typing was performed in silico using the Achtman profile in BIGSdb38.

Identification of the ETT2 and eip loci was performed using BLAST. Coverage and sequence percentage identities to the reference genome of EAEC 042 are shown in Table 1. The ETT2 locus was termed intact if it contained no deletion, insertions or inactivating mutations.

Maximum Likelihood trees of the sequences shown in Fig. S1 was performed using RaxML39 on core genes (2804 genes) using a Generalised Time Reversible Gamma model (-m set to GTRGAMMA), the algorithm set to rapid Bootstrap analysis and search for bestscoring ML tree in one program with flag -f set to a, number of bootstraps set to 100, and the seed values in flags -p and -x set to 12345.

Global representative sequences filtered as bloodstream isolates were downloaded from the EnteroBase archive40 with accession numbers set out in Table S1. They were from diverse geographical locations and patients as indicated in available metadata.

Domain analysis of the EaeX protein

Domain identification within the EaeX protein was determined using ScanProsite and the PROSITE data base41.

Growth and eilA reporter assay

Growth media used in this study were DMEM (Invitrogen, UK), LB, and a 1:1 mix of LB with DMEM. The eilA reporter construct contains a ~500 bp fragment upstream of the eilA promoter from the CE10 strain of E. coli (Accession number NC017646) that was cloned into a plasmid (pAJR70) used in a previous study for the assessment of transcription of ETT1 operons by enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) monitoring from liquid culture42. The different bacterial strains were transformed with this plasmid using standard methods. Chloramphenicol (25 µg/ml) was added to media when required for the selection of strains containing the eilA reporter. Induction of GFP in the different media at 37 °C was measured using a fluorescence plate-reader (FLUOstar Optima; BMG; Labtech, UK). Optical densities and fluorescence were recorded every 24 minutes for 9 hours. Measurements from bacteria transformed with the promoterless pAJR70 showed there was no signal produced above that of the fluorescence of bacteria alone which was subtracted from all readings.

Type III secretion assay

Secreted proteins were extracted by trichloroacetic acid precipitation performed as previously described43. Briefly, overnight LB cultures were diluted 1/100 in 50 ml of the culture media and grown for 9 hours before precipitation of secreted proteins. Secreted proteins were resuspended in 150 µl of loading buffer and analysed by SDS-PAGE.

Quantitative PCR

Bacteria were grown to late-log phase in the indicated media and harvested into RNAprotect (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. RNA was extracted using a RNAeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Contaminating DNA was removed using Turbo DNAse (Ambion) followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. RNA was reverse transcribed and quantitative PCR performed using a Syber Green PowerUp master mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Specific primers used are shown in Supplementary Table S3. Amplification was performed using a 7500 series RT PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Quantification of results was performed using the ΔΔCt method of Livak and Schmittgen, using gapA as a reference gene44. Results were expressed as fold induction in LB:DMEM relative to the level in LB alone.

Ethical approval

Advice was sought from the Local Research Ethics Committee of Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Board. Specific ethical permission was deemed not to be required as the study was viewed as service improvement. Approval for access to clinical patient data was given by the Caldicott Guardian of the relevant health boards, who is the designated regulator of confidential patient information within NHS Scotland.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The work was funded by the Scottish Executive via the Chief Scientists Office through the provision of a grant to establish the Scottish Healthcare Associated Infection Prevention Institute (SHAIPI). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: M.H., A.L., T.E.; Investigation: S.F., C.G., J.C., N.O.’B., J.M., A.R., T.E.; Resources: M.C., A.L.; Writing: S.F., C.G., J.C., A.R., M.C., A.L., T.E.

Data availability

Illumina sequences are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA: www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under project PRJEB12513. The global E. coli accession numbers from the ENA are set out in Table S1.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-61026-x.

References

- 1.Green, E. R. & Mecsas, J. Bacterial Secretion Systems: An Overview. Microbiol Spectr4, 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0012-2015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Cornelis GR. The type III secretion injectisome. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2006;4:811–825. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mota LJ, Cornelis GR. The bacterial injection kit: type III secretion systems. Ann. Med. 2005;37:234–249. doi: 10.1080/07853890510037329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng W, et al. Assembly, structure, function and regulation of type III secretion systems. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2017;15:323–337. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hueck CJ. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998;62:379–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.62.2.379-433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaytán, M. O., Martínez-Santos, V. I., Soto, E. & González-Pedrajo, B. Type Three Secretion System in Attaching and Effacing Pathogens. 6, 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00129 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Stevens, M. P. & Frankel, G. M. The Locus of Enterocyte Effacement and Associated Virulence Factors of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr2, EHEC-0007-2013, 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0007-2013 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hayashi T, et al. Complete genome sequence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genomic comparison with a laboratory strain K-12. DNA Res. 2001;8:11–22. doi: 10.1093/dnares/8.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perna NT, et al. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature. 2001;409:529–533. doi: 10.1038/35054089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lostroh CP, Lee CA. The Salmonella pathogenicity island-1 type III secretion system. Microbes and infection/Institut Pasteur. 2001;3:1281–1291. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou M, Guo Z, Duan Q, Hardwidge PR, Zhu G. Escherichia coli type III secretion system 2: a new kind of T3SS? Vet. Res. 2014;45:32. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-45-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartleib S, Prager R, Hedenstrom I, Lofdahl S, Tschape H. Prevalence of the new, SPI1-like, pathogenicity island ETT2 among Escherichia coli. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;292:487–493. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makino S, et al. Distribution of the secondary type III secretion system locus found in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates among Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:2341–2347. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2341-2347.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyazaki J, Ba-Thein W, Kumao T, Akaza H, Hayashi H. Identification of a type III secretion system in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002;212:221–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren CP, et al. The ETT2 gene cluster, encoding a second type III secretion system from Escherichia coli, is present in the majority of strains but has undergone widespread mutational attrition. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:3547–3560. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3547-3560.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sims GE, Kim SH. Whole-genome phylogeny of Escherichia coli/Shigella group by feature frequency profiles (FFPs) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8329–8334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105168108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lecointre G, Rachdi L, Darlu P, Denamur E. Escherichia coli molecular phylogeny using the incongruence length difference test. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:1685–1695. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikh J, et al. EilA, a HilA-like regulator in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:338–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ideses D, et al. A degenerate type III secretion system from septicemic Escherichia coli contributes to pathogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:8164–8171. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.8164-8171.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S, et al. Escherichia coli type III secretion system 2 regulator EtrA promotes virulence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2017;163:1515–1524. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S, et al. Escherichia coli Type III Secretion System 2 ATPase EivC Is Involved in the Motility and Virulence of Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1387. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao Y, et al. The type III secretion system is involved in the invasion and intracellular survival of Escherichia coli K1 in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;300:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goswami, C. et al. Genetic analysis of invasive Escherichia coli in Scotland reveals determinants of healthcare-associated versus community-acquired infections. Microb Genom4, 10.1099/mgen.0.000190 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Buist G, Steen A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. LysM, a widely distributed protein motif for binding to (peptido)glycans. 2008;68:838–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu S, et al. Complete genome sequence of the neonatal-meningitis-associated Escherichia coli strain CE10. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:7005. doi: 10.1128/JB.06284-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puente JL, Bieber D, Ramer SW, Murray W, Schoolnik GK. The bundle-forming pili of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: transcriptional regulation by environmental signals. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;20:87–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leverton LQ, Kaper JB. Temporal expression of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence genes in an in vitro model of infection. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:1034–1043. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1034-1043.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutta T, Srivastava S. Small RNA-mediated regulation in bacteria: A growing palette of diverse mechanisms. Gene. 2018;656:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lara-Tejero M, Kato J, Wagner S, Liu X, Galan JE. A sorting platform determines the order of protein secretion in bacterial type III systems. Science. 2011;331:1188–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.1201476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collazo CM, Galan JE. Requirement for exported proteins in secretion through the invasion-associated type III system of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:3524–3531. doi: 10.1128/IAI.64.9.3524-3531.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song M, et al. Control of type III protein secretion using a minimal genetic system. Nature communications. 2017;8:14737. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, et al. Regulators encoded in the Escherichia coli type III secretion system 2 gene cluster influence expression of genes within the locus for enterocyte effacement in enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:7282–7293. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7282-7293.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shulman, A. et al. The Escherichia coli Type III Secretion System 2 Has a Global Effect on Cell Surface. mBio 9, 10.1128/mBio.01070-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Page AJ, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jolley KA, Maiden MC. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stamatakis A. Using RAxML to Infer Phylogenies. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2015;51(6 14):11–14. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0614s51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou, Z. et al. The EnteroBase user’s guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res., 10.1101/gr.251678.119 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Sigrist CJ, et al. New and continuing developments at PROSITE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D344–347. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roe AJ, et al. Heterogeneous surface expression of EspA translocon filaments by Escherichia coli O157:H7 is controlled at the posttranscriptional level. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5900–5909. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5900-5909.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tree JJ, et al. Transcriptional regulators of the GAD acid stress island are carried by effector protein-encoding prophages and indirectly control type III secretion in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:1349–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Illumina sequences are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA: www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under project PRJEB12513. The global E. coli accession numbers from the ENA are set out in Table S1.