Abstract

Two ratiometric near-infrared fluorescent probes have been developed to selectively detect mitochondrial pH changes based on highly efficient through-bond energy transfer (TBET) from cyanine donors to near-infrared hemicyanine acceptors. The probes consist of identical cyanine donors connected to different hemicyanine acceptors with a spirolactam ring structure linked via a biphenyl linkage. At neutral or basic pH, the probes display only fluorescence of the cyanine donors when they are excited at 520 nm. However, acidic pH conditions trigger spirolactam ring opening, leading to increased π-conjugation of the hemicyanine acceptors, resulting in new near-infrared fluorescence peaks at 740 nm and 780 nm for probes A and B, respectively. This results in ratiometric fluorescence responses of the probes to pH changes indicated by decreases of the donor fluorescence and increases of the acceptor fluorescence under donor excitation at 520 nm due to a highly efficient TBET from the donors to the acceptors. The probes only show cyanine donor fluorescence in alkaline-pH mitochondria. However, the probes show moderate fluorescence decreases of the cyanine donor and considerable fluorescence increases of hemicyanine acceptors during the mitophagy process induced by nutrient starvation or under drug treatment. The probes display rapid, selective, and sensitive responses to pH changes over metal ions, good membrane penetration, good photostability, large pseudo-Stokes shifts, low cytotoxicity, mitochondria-targeting, and mitophagy-tracking capabilities.

1. Introduction

Mitochondria, the power-house organelles found in virtually all eukaryotic cells, produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to meet cellular bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands.1-7 Dysfunctional mitochondria have been linked to neurological and cardiovascular diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, and even to some types of cancer.1-7 The removal of defective or dysfunctional mitochondria plays an important role in controlling mitochondrial quality and thus sustaining proper cellular functions. This process, called mitophagy, comprises the uptake of damaged mitochondria into autophagosomes, which subsequently fuse with lysosomes to degrade the mitochondria. In order to track and visualize the mitophagy process, two different mitochondria- and lysosome-targeting fluorescent probes with different emission wavelengths would be needed to detect the dramatic pH changes during mitophagy: a slightly basic pH of 8.0 in the mitochondria and an acidic pH of 4.5 in the autolysosomes.8 However, this approach is inconvenient and suffers from systematic errors caused by variations in the emission intensity, concentration, and compartmental localization of such intensity-based fluorescent probes.9 Very recently, ratiometric fluorescent probes with two well-defined emissions have been developed to overcome the systematic errors. These probes show very promising tracking capabilities of the mitophagy process.10-17 Ratiometric fluorescent probes are typically based on the modulation of p-conjugation changes inside the fluorophores or the manipulation of the energy transfer between the reference fluorescence donor and pH-sensitive fluorescence acceptors upon pH changes.10-17 However, ratiometric fluorescent probes for monitoring mitophagy based on the FRET or TBET approaches are still underdeveloped, especially those with near-infrared emissions.10-19 Near-infrared probes have multiple advantages: they show deep-tissue penetration, the smallest water Raman peak interference, very little background fluorescence, and minimal photo damage to cells and tissues. Therefore, the development of mitochondria-specific ratiometric near-infrared fluorescent probes with well-defined dual absorption and emission spectra is crucial for the study of mitophagy and related diseases.

Here, we developed two ratiometric near-infrared fluorescent probes (A and B), which exert excellent double-channel fluorescence imaging capabilities with dual excitation and emission spectra to specifically target mitochondria. The detection of mitochondria makes use of the electrostatic interactions between the positively charged probes and the negative inner membrane potential of the mitochondria. Thus, the probes detect pH changes within mitochondria, which are associated with the mitophagy process (Scheme 1). We used a positively charged cyanine dye as a donor and connected it to two different near-infrared hemicyanine acceptors linked via a biphenyl bridge. The connection is mediated by a spirolactam switch, which restricts π-conjugation between the donors and acceptors. We also introduced amine-functionalized morpholine residues to the acceptors. These morpholine residues enhance probe hydrophilicity and reduce the pKa values of the acceptors, so that the acceptors will not display any fluorescence under the slightly basic environment in mitochondria (i.e., at pH 8).

Scheme 1.

Ratiometric fluorescent probes and their structural responses to pH changes.

We find that solutions of probe A under acidic conditions (pH 2.0) display several absorption peaks, the main ones at 558 and 715 nm arising out of the cyanine donor and the hemicyanine acceptor, respectively. In contrast, solutions (pH 2.0) of probe B display corresponding absorption peaks at 558 and 732 nm. Probe B consists of an identical cyanine donor to probe A but has a different hemicyanine acceptor, which absorbs at a longer wavelength. At basic or neutral pH values, solutions of probe A only show one emission peak at 588 nm under donor excitation of 520 nm. Under acidic conditions, probe A shows a new emission peak at 740 nm under excitation at either 520 nm or 665 nm. The acidic pH triggers the opening of the spirolactam ring of the hemicyanine acceptor, resulting in a highly efficient TBET from the cyanine donor to the hemicyanine acceptor. The fact that probe A under acidic conditions emits at 740 nm under donor excitation at 520 nm illustrates the high TBET efficiency from the cyanine donor to the hemicyanine acceptor. We found that probe B has a lower energy transfer efficiency than probe A. Only the cyanine donors in probes A and B show strong fluorescence in mitochondria, while the hemicyanine acceptors with closed spirolactam structures show no fluorescence under the slightly basic pH conditions in mitochondria. However, hemicyanine acceptors fluoresce as a result of the spirolactam ring opening at the acidic pH value of 4.5 in autolysosomes. Under these conditions, the fluorescence of the cyanine donors decreases when lysosomes fuse with the autophagosomes. We demonstrate that probes A and B can ratiometrically detect mitochondrial pH changes in live cells and Drosophila melanogaster first-instar larvae. We further show that both probes can be used to monitor the mitophagy process caused by nutrient starvation and drug treatment in cells.

2. Results and discussions

2.1. Probe design and synthesis

Targeting mitochondria through the electrostatic interactions of positively charged fluorescent probes and the negative inner membrane potentials of mitochondria allows for effective monitoring of mitophagy processes. We chose to employ a positively charged cyanine dye as the TBET donor and hemicyanine dyes as TBET acceptors to prepare ratiometric fluorescent probes for pH detection. Such probes have many advantages, such as large absorption extinction coefficients, high fluorescence quantum yields, near-infrared fluorescence, good photostability, and chemical stabilities. Cyanine dye (3) was prepared by a condensation reaction of 5-bromo-1,2,3,3-tetramethyl-3H-indol-1-ium iodide (1) with Fisher’s aldehyde (2a), affording a cyanine dye bearing a bromo group (3) (Scheme 2). Compound 5 was then prepared using a Miyaura borylation reaction to convert the bromo group of compound 3 through a palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of bis(pinacolato)diboron (4) with the bromo group of compound 3. Hemicyanine dyes (9a or 9b) were synthesized by first condensing 5-bromo-2-(4-(dimethylamino)-2-hydroxybenzoyl)benzoic acid (6) with cyclohexanone (7) under acidic conditions, yielding 9-(4-bromo-2-carboxyphenyl)-6-(dimethylamino)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroxanthylium perchlorate (8), and then condensing compound 8 with Fisher’s aldehyde (2a) or (Z)-2-(1,1,3-trimethyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[e]indol-2-ylidene)acetaldehyde (2b) in acetic anhydride (Scheme 2).20-24 In order to turn off the fluorescence of the hemicyanine acceptors in mitochondria and enhance hydrophilicity of the probes, we modified the hemicyanine dyes (9a and 9b) with 2-morpholinoethylamine (10), affording hemicyanine dyes with pH-activated closed spirolactam structures (11a and 11b) (Scheme 2). Fluorescent probes A and B were synthesized by a palladium-catalyzed Suzuki coupling reaction of the cyanine dye (5) with a hemicyanine dye (11a or 11b). This established a sp2 carbon–carbon biphenyl connection between the cyanine donor and the near-infrared hemicyanine acceptor.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic approach to prepare fluorescent probes A and B.

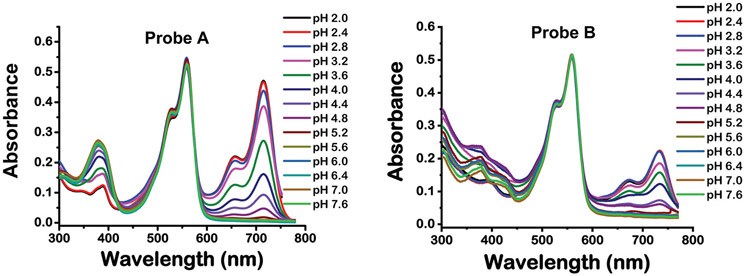

2.2. Absorption responses of the probes to pH changes

We obtained the absorption spectra of the probes under different pH levels. At basic or neutral pH values, probe A displays absorptions at 380, 526(sh) and 558 nm (Fig. 1). Under these conditions, the closed structure of the spirolactam ring attached to the hemicyanine acceptor is maintained. However, gradual decreases of the pH from 7.6 to 2.0 result in additional absorptions at 655(sh) and 715 nm, as acidic pH conditions result in the opening of the spirolactam ring on the hemicyanine acceptor leading to increased π-conjugation throughout the acceptor molecule. Additionally, the UV-vis absorption peak at 380 nm decreases with the pH-activated π-conjugation enhancement of the hemicyanine acceptor (Fig. 1). Probe B displays similar responses to the pH changes as probe A. At neutral or basic pH, probe B displays absorption peaks at 392, 526(sh) and 558 nm. Acidic pH conditions result in spirolactam ring opening of the hemicyanine acceptor and promote the appearance of additional absorption peaks at 672(sh) and 732 nm, the intensities of which increase with enhanced acidic strength (Fig. 1). Both probes display an absorption peak at 558 nm because they contain identical cyanine donor moieties. However, under acidic conditions, probe B has a longer wavelength absorption (i.e., 732 nm) from the hemicyanine acceptor than probe A (i.e., 715 nm) because of a more extended π-conjugation system from the additional fused phenyl ring.

Fig. 1.

Absorption spectra of probes A (left) and B (right) in buffers with different pH values containing 10% ethanol.

2.3. Fluorescence responses of probes A and B to pH changes

Probe A displays a fluorescence peak of the cyanine donor at 588 nm with a fluorescence quantum yield of 24.7% at pH 7.6 under 520 nm excitation because the closed spirolactam ring structure on the hemicyanine acceptor is retained. Under acidic conditions, probe A shows an additional fluorescence peak at 740 nm under the excitation of 520 nm because the acidic pH promotes spirolactam ring opening of the hemicyanine acceptor, resulting in highly efficient TBET from the cyanine donor to the hemicyanine acceptor. Probe A displays ratiometric fluorescence responses to pH changes under donor excitation at 520 nm as gradual decreases of the pH from 7.6 to 2.0 cause small decreases of the cyanine donor fluorescence and lead to significant increases of the hemicyanine acceptor fluorescence (Fig. 2 left). The energy transfer efficiency of probe A from the donor to the acceptor was calculated to be 91.5% in a pH 2.0 buffer under 520 nm excitation. The fluorescence quantum yields of the donor and acceptor of probe A are 17.5% and 15.4% in a pH 2.0 buffer containing 10% ethanol under 520 nm excitation. The fluorescence quantum yield of the acceptor of probe A in a pH 2.0 buffer containing 10% ethanol is 26.6% under 665 nm excitation of the acceptor (Fig. 3 left). The pKa of probe A related to spirolactam ring opening, according to fluorometric titration based on the hemicyanine emission under the excitation of the donor (Fig. S22 left, ESI†) and acceptor (Fig. S23 left, ESI†), is calculated to be 3.92(3) and 4.03(3), respectively. This relatively low pKa value enables the probe to track the mitophagy process because the fluorescence of the hemicyanine acceptor is turned off in mitochondria and becomes activated only through ring opening of the spirolactam moiety due to the acidic conditions (pH of 4.5) in autolysosomes, while the fluorescence of cyanine donors decreases when lysosomes fuse with the autophagosomes to complete the autophagy stage of the mitophagy process.

Fig. 2.

Fluorescence spectra of 10 μM probes A (left) and B (right) in buffers with different pH values containing 10% ethanol under excitation at 520 nm.

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence spectra of 10 μM probes A (left) and B (right) in buffers with different pH values containing 10% ethanol under acceptor excitation of 665 nm and 680 nm for probes A and B, respectively.

Probe B shows a similarly strong donor fluorescence peak at 582 nm with a fluorescence quantum yield of 22.2% at pH 7.6 in a buffer containing 10% ethanol under 520 nm excitation, (Fig. 2 right). A new near-infrared fluorescence peak at 752 nm appears under acidic conditions due to the opening of the spirolactam ring of the hemicyanine acceptor, which enhances π-conjugation in the acceptor. Gradual decreases of the pH from 7.6 to 2.0 cause slight decreases of the donor fluorescence, slight increases of the hemicyanine acceptor under donor excitation of 520 nm (Fig. 2 right), and strong fluorescence increases of the hemicyanine acceptor under acceptor excitation at 680 nm (Fig. 3 right). Under donor excitation of 520 nm, the fluorescence quantum yields of the donor and acceptor of probe B in pH 2.0 buffer containing 10% ethanol are 16.7% and 2.1%, respectively. The fluorescence quantum yield of the hemicyanine acceptor in pH 2.0 is 5.7% at excitation at the acceptor absorption peak at 680 nm. Using similar calculations to probe A, the pKa of probe B was established at 3.67(6) and 3.74(2), which are slightly lower than those obtained for probe A (Fig. S22 right and S23 right, ESI†).

2.4. Theoretical results

The nature of the geometric changes upon protonation to probes A and AH+ are displayed in Fig. 4. The changes in probes B and BH+ are similar. The major change upon protonation occurs as the result of the spirolactam ring opening resulting in an increase in the angle formed by the atoms labelled as ‘‘1–2–3’’ changing from 137.8° to 176.7°, see Fig. 4. There are also slight changes in the orientation of the plane of the two rings associated with this angle, i.e., the six-member rings inclusive of atoms 1 and 2 compared to that inclusive of atoms 2 and 3. In probe A, this interplanar angle is 88.3°, while the angle is 72.1° in probe AH+.

Fig. 4.

Mercury25 representations of probes A (left) and AH+ (right).

The electronic transition data are best displayed in the form of current density illustrations, which depict the flow of electron density as the result of the allowed transitions from the various molecular orbitals, as illustrated in Fig. 5 for the most probable transitions. The direction of the flow of the electron density is from the more negative region or the ground state to the more positive region or the excited state in question. There are two transitions assessed for each probe and, as depicted in Fig. 5, there are differences in the origins of the 558 nm transition between those in probe A, as compared to probe B, which is interesting in light of the similarities in these structures, see Fig. 2. For probe A, 93.1% of the transition is localized on the cyanine region (top half of the drawing). For probe B, 72% of the transition is localized within the cyanine region, 22% from the hemicyanine (bottom half of the drawing) to the cyanine region and 3% localized on the hemicyanine region, see Fig. 5, Fig. S27 (ESI†) for probe A and Fig. S35 (ESI†) for probe B. For both probes, the transitions calculated for probes A and B at 395 nm and 402 nm, respectively, are mostly based on orbitals localized on the hemicyanine region of the molecules (79.2% and 79.0%, respectively) with smaller contributions from other regions, as listed in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Illustrations of the current density difference as isosurfaces of the probes A and B and their protonated forms, AH+ and BH+, as indicated for the excited states (ES) and the calculated (and experimental) wavelengths. The composition of specific ES and percentage contributions are indicated. The numerical range values for the color scale illustrated at the top of the figure is also listed. Drawings of the numbered MOs are available in the ESI.†

In the protonated versions and, as also discovered experimentally, the shift to longer wavelengths may be ascribed to the extended conjugation in the hemicyanine region of the molecule. In the drawing for probe AH+ (Fig. 5), the 611 nm transition originates in the center region of the molecule and is restricted to the cyanine region of the molecule (or the bottom half). The 623 nm transition for probe BH+, also originates in the center, but the excited state would appear to be delocalized over the entire molecule, judging by the lighter blue (as compared to that for probe AH+) appearance over the entire molecule (with the electron density scales being identical). The reason may be that the 611 nm transition for AH+ also includes a 5% contribution originating from the cyanine region to the hemicyanine, and this transition is not present in BH+. The higher energy transition for AH+ and BH+ occurring at 501 and 503 nm, respectively, is 86.6% localized on the cyanine region for AH+, whereas that for BH+ is shared equally (i.e., 48.2 and 48.6%) between transitions originating and ending on the two parts of the molecule (Fig. 5).

Probes A and B were determined to have solubilities of at least 2.5 and 2.0 g L−1 in aqueous solutions, respectively. Solubilities were also qualitatively assessed for probes A and AH+ on the basis of calculations relating the free energies of solvation to that obtained for the gaseous phase. These were conducted at 298.15 K with the SMD26 option to the SCRF keyword,27 the APFD28 functional and the 6-311+g(d)29 basis set. The results are summarized in Table 1 and suggest that probe A has comparable solubility in water and benzene but is more soluble in ethanol and tetrahydrofuran, judging by the ΔGsolv values. Additionally, probe AH+ is as expected more soluble than probe A with a similar trend in the different solvents.

Table 1.

Calculated free energies of solvation for probes A and AH+

| Environment | A |

AH+ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G (Hartrees) | ΔGsolv (kcal mol−1) | G (Hartrees) | ΔGsolv (kcal mol−1) | |

| Gas | −3110.011423 | 0 | −3110.373539 | 0 |

| Water | −3110.105790 | −59.22 | −3110.555278 | −114.04 |

| Benzene | −3110.101645 | −56.61 | −3110.501082 | −80.03 |

| Ethanol | −3110.141118 | −81.38 | −3110.587276 | −134.12 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | −3110.129846 | −74.31 | −3110.562620 | −118.65 |

2.5. Photostability and reversibility of probes A and B

The photostability of the probes was evaluated by measuring the fluorescence intensity every 20 min through continuous excitation of the probes under the cyanine donor (520 nm) or hemicyanine acceptor (665 nm for probe A and 680 nm for probe B) wavelengths. Both probes A and B exhibited excellent photostability for the cyanine donor with a fluorescence decrease of less than 2.0% under a 3 h session excitation at 520 nm under acidic or neutral conditions, while the fluorescence intensity of the hemicyanine acceptor of probes A and B decreased by less than 5.0% under similar conditions during the 3 h test time (Fig. S40 and S41, ESI†). In addition, probes A and B showed excellent reversible fluorescence responses to pH alterations from 2.0 to 7.6 for up to 5 cycles (Fig. S42, ESI†), indicating that probes A and B may be used to detect intracellular pH fluctuations.

2.6. Ion selectivity of probes A and B

The ion selectivity of probes A and B was investigated at pH 2.0 and 7.6 in buffer solutions containing 10% ethanol, either with or without 20-fold concentrations of different cations, anion acids, and amino acids. The fluorescence intensities of the cyanine and hemicyanine skeletons of the probes were not significantly affected by the addition of 100 μM of cations (Al3+, Ca2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+ or Zn2+) at either pH 2.0 or 7.6 (Fig. S43 and S44, ESI†), illustrating that the response to pH changes in the probes was not influenced by these metal cations. The selectivity experiments of the probes against anions were carried out by adding anions to a 20-fold of the normal concentration, including HCO3−, CO32−, NO2−, NO3−, SO42−, PO43− or Cl− to the solution containing 5 μM of either probe in buffers of pH 2.0 or 7.6. Fig. S45 and S46 (ESI†) show that the probe responses to pH changes were unaffected by these anions. Additionally, interference tests with different amino acids were performed similarly. The fluorescence intensities of the probes changed very slightly at either pH 2.0 or 7.6 with 100 μM of added amino acids, such as glycine, glutamic acid, glutathione, tyrosine, proline, methionine, leucine, cystine, arginine or alanine (Fig. S47 and S48, ESI†). Hence, we can conclude that probes A and B can detect pH changes without any significant interference from these aforementioned cations, anions, and amino acids.

2.7. Cytotoxicity of probes A and B

Standard MTT assays were conducted by incubating HeLa cells with 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 μM concentrations of probes A or B for 24 h (Fig. S49, ESI†). The viability of the cells incubated with 10 μM probe A and B was 92.7% and 90.5%, respectively, indicating that the probes possess good biocompatibility and that they can used for biological studies. Probe A possesses a higher TBET and displays lower cytotoxicity against HeLa cells than probe B.

2.8. Cellular fluorescence imaging of mitochondria

We investigated the cell permeability of our fluorescent probes by incubating HeLa cells at different concentrations of probe A and B for 30 min in normal medium. We found that probe A showed strong intracellular visible fluorescence of the cyanine donor under donor excitation. The fluorescence intensity increased with increased concentrations of the probes. However, the fluorescence signals of the hemicyanine acceptors were very weak under either donor or acceptor excitation (Fig. S50, ESI†). Similar results were observed with probe B for the cyanine fluorescence channel, but probe B showed even weaker near-infrared fluorescence than probe A at the same probe concentration (Fig. S51, ESI†). In order to determine where the probes are located within live cells, we conducted colocalization experiments by incubating HeLa cells with our probes A and B, and either a known lysosome-specific fluorescent probe (Lysosensor blue DND-167) or a mitochondria-specific fluorescent probe (MitoView blue). The cells displayed strong visible fluorescence (green channel), weak near-infrared fluorescence (red and purple channels) from the probes, and blue fluorescence from either MitoView blue or Lysosensor blue DND-167 (blue channels) simultaneously. Because the probes displayed stronger green fluorescence relative to near-infrared fluorescence in normal cell culture medium, the overlap of green fluorescence images with blue fluorescence images was used to determine the probe locations in live cells. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients between Lysosensor blue, and probes A and B are 0.23, and 0.34, respectively, while the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between MitoView blue and probes A and B are 0.92, and 0.93, respectively (Fig. 6 and Fig. S52, ESI†). These results convincingly demonstrate that the probes possess excellent cell permeability and can be used to specifically stain mitochondria in live cells through electrostatic interactions of the positively charged probes A and B with the negative membrane potential in the inner mitochondrial membrane. The extremely low fluorescence of the hemicyanine acceptors further confirms that the probes are located in mitochondria because the slightly basic pH 8.0 inside the mitochondria keeps the spirolactam ring of the probes closed, not allowing any fluorescence (Fig. 6 and Fig. S52, ESI†).

Fig. 6.

Cellular fluorescence images of HeLa cells incubated with 10 μM of either probe A (left) or B (right) and MitoView blue after 30 min incubation in normal medium. Scale bar: 10 μm.

To further test for the mitochondria-specificity of our probes, we disrupted the mitochondrial membrane potential with carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), which leads to the acidification of the mitochondria.30 We incubated HeLa cells with probe A for 20 min and added FCCP for another 20 min incubation. In the control experiment without the FCCP treatment, only cyanine donor fluorescence was observed, while under donor and acceptor excitation, fluorescence of the hemicyanine acceptor was lacking (Fig. 7). However, further incubation of the cells with FCCP caused a moderate fluorescence decrease of the cyanine donor in the visible channel and a significant fluorescence increase of the hemicyanine acceptor in the near-infrared channel (Fig. 7). The ratio images of the near-infrared red channel II divided by the visible green channel I also underwent dramatic color changes from black to purple (Fig. 7). A similar result was observed for the ratiometric images of the near-infrared fluorescence in the third channel divided by the visible fluorescence in the first channel (Fig. S53, ESI†). Because the FCCP cell treatment causes acidification of the mitochondria, our results convincingly demonstrate that probe A specifically targets and stains the mitochondria, resulting in ratiometric fluorescence responses to pH changes in mitochondria, as reflected in the donor fluorescence decrease and the acceptor fluorescence increase (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Fluorescence images of HeLa cells with 7.5 μM probe A in normal medium after a 20 min incubation before and after FCCP treatment. Ratiometric images were obtained by dividing the near-infrared fluorescence in the second channel by the visible fluorescence in the first channel. Scale bar: 50 μm.

2.9. Ratiometric visualization of intracellular pH changes

Since probes A and B show excellent cell permeability and specific targeting of mitochondria in live cells, we further studied whether the probes could be applied to detect mitochondrial pH changes by incubating HeLa cells with the probes in different buffer solutions with pH values of 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5 and 7.0, each containing 10 μg mL−1 nigericin. We employed nigericin, K+, and H+ ionophores, to equilibrate the intracellular and extracellular pH values in the different buffer solutions.31-36 As a result, gradual decreases of the intracellular pH result in gradual decreases of visible donor fluorescence (green channel) and gradual increases of near-infrared acceptor fluorescence (red and purple channels) (Fig. 8), which is consistent with the fluorescence changes observed in buffer solutions upon pH decreases (Fig. 2 and 3). Merged images of green and red channels for probe A also show significant color changes from deep green to orange in response to intracellular pH decreases from 7.0 to 3.0 (Fig. 8). Ratiometric images of probe A also display considerable color changes from complete black to purple and then to purplish white, when the intracellular pH value gradually decreases from 7.0 to pH 3.0 (Fig. 8 and Fig. S54, ESI†). We observed similar ratiometric cellular fluorescence responses of probe B (Fig. S55 and S56, ESI†). Probe B possessed a slightly narrower ratiometric responsive window to pH changes because probe B possesses a somewhat lower pKa value (Fig. S55 and S56, ESI†). The quantitate analysis of Fig. 8 and Fig. S54 (ESI†) resulted in pKa values of 3.93 and 3.61 for probe A and B (Fig. S57, ESI†), respectively, which were consistent with results of the optical properties (Fig. 2 and Fig. S22, S23, ESI†).

Fig. 8.

Cellular fluorescence images of HeLa cells incubated with 10 μM probe A in different pH buffers containing 10 μg mL−1 nigericin. Green channel, emission collected from 575 nm to 625 nm under donor excitation at 559 nm; NIR channels, emission collected from 720 nm to 770 nm under donor excitation at 559 nm and acceptor excitation at 635 nm, respectively. The ratio images were obtained by dividing the near-infrared fluorescence in the second channel by the visible fluorescence in the first channel. Scale bar: 50 μm.

2.10. Mitophagy study

We further investigated whether the probes can be used to track the mitophagy processes caused by nutrient starvation, which is known to induce mitophagy. During mitophagy, defective mitochondria ultimately fuse with lysosomes to produce acidic autolysosomes, resulting in a decrease in the pH value within the mitochondria. We chose probe A to monitor the mitophagy process because of its highly efficient TBET as well as its suitable pKa value for acidic autolysosomes. We incubated HeLa cells in serum-free medium with probe A and observed that after starvation times between 10 min to 2 h, the visible donor fluorescence in the first channel decreased, while the near-infrared acceptor fluorescence in the second channel under cyanine donor excitation gradually increased (Fig. 9). After a 1 h long incubation, a significant color change in the ratio images of the near-infrared fluorescence in channel II divided by the visible fluorescence in channel I started to become visible and appeared deep blue. After 2 h of starvation, the color shifted to purplish brown (Fig. 9). Furthermore, the ratio image of near-infrared fluorescence in channel III divided by the visible fluorescence in channel I changed similarly from black to violet-red from a 10 min to a 2 h incubation under nutrient starvation (Fig. S58, ESI†). These results indicate that probe A can track mitophagy induced by nutrient starvation.

Fig. 9.

Ratiometric fluorescence imaging of HeLa cells with 10 μM probe A in serum-free medium under donor and acceptor excitation at various times with scale bars of 50 μm. The ratio images were obtained by dividing the near-infrared fluorescence in the second channel by the visible fluorescence in the first channel.

In order to further test if probe A can be used to monitor the mitophagy process, we conducted co-localization experiments by co-staining HeLa cells with probe A and the commerciality available mitochondria-targeting probe, MitoView blue or the lysosome-specific probe, Lysosensor blue, together with probe A at different incubation times. We observed that probe A remained inside the mitochondria during a 20 min incubation of HeLa cells in serum-free medium. This result was confirmed by our other results that probe A (channel I) with MitoView blue in HeLa cells displayed a high Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.93 (Fig. 10, left), and that it has a much lower Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.09 with Lysosensor blue (Fig. 10, right). In contrast, under a 2 h starvation, the Pearson correlation coefficient of probe A with MitoView blue became much lower and was found to be 0.51, while the Pearson correlation coefficient of probe A with Lysosensor blue became 0.88 (Fig. 11). These results conclusively demonstrated that probe A can be applied to track the process of mitophagy caused by nutrient starvation. Furthermore, we employed rapamycin at a concentration of 100 nM to stimulate mitophagy in normal medium in order to further test the tracking efficiency of the probe for mitophagy.37 The ratio fluorescence images displayed a significant increase in near-infrared fluorescence and a moderate decrease in cellular visible fluorescence with substantial color ratio changes from black to purple during drug treatment of HeLa cells (Fig. S59 and S60, ESI†). This suggests that probe A is located within the autolysosomes formed from damaged mitochondria during mitophagy induced by a 2 h rapamycin treatment.

Fig. 10.

Cellular fluorescence images of HeLa cells incubated with 10 μM of probe A and either MitoView blue (left) or Lysosensor blue (right) for 20 min in medium without fetal bovine serum. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Fig. 11.

Cellular fluorescence images of HeLa cells incubated with 10 μM of probe A and either MitoView blue (left) or Lysosensor blue (right) for 2 h in medium without fetal bovine serum. Scale bar: 10 μm.

2.11. Probe A detects pH changes in D. melanogaster larvae

In order to test if probe A also functions in an in vivo system, we dissolved the probe in three different buffers at pH levels of 7.4, 5.5, and 3.2. Freshly hatched fruit fly larvae were then submerged in each buffer-probe solution for 2 h, washed thrice with deionized water, and imaged (Fig. 12). As a result, the pH-dependent fluorescence patterns matched the results obtained in the in vitro experiments (Fig. 2): at pH 7.4 under 520 nm and 635 nm excitation, only cyanine donor fluorescence was observed (Fig. 12). Gradual pH decreases to pH 5.2 and 3.2 resulted in significant increases of near-infrared fluorescence of the hemicyanine acceptor in channels II and III under 520 nm and 635 nm excitation. We also observed slight decreases of cyanine donor fluorescence under 520 nm excitation (Fig. 12). Thus, probe A can monitor pH changes in a multi-cellular organism.

Fig. 12.

Fluorescence images of D. melanogaster first-instar larvae under a 2 h incubation with 10 μM probe A in different pH buffers. Scale bar: 200 μm

3. Conclusion

In summary, we developed two TBET-based ratiometric near-infrared fluorescent probes A and B, capable of detecting pH changes ratiometrically in mitochondria. Our probes consist of cyanine donors and hemicyanine acceptors linked via a biphenyl bridge. At neutral or basic pH values, both probes only show fluorescence of the cyanine donor while under acidic pH conditions, spirolactam ring opening occurs and promotes a highly efficient energy transfer from the cyanine donor to the hemicyanine acceptor. The probes show good mitochondria-targeting and mitophagy-tracking capabilities due to their ratiometric fluorescence responses to pH changes, good photostability, large pseudo-Stokes shifts, and high selectivity to pH over metal ions, various anions, and amino acids. Probe A can also detect pH changes in mitochondria and D. melanogaster first-instar larvae. We anticipate that our new probes will serve as platforms to facilitate the development of a variety of mitochondria-specific ratiometric fluorescent probes for detection of metal ions, and biothiols by introducing appropriate binding ligands to the hemicyanine acceptors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R15GM114751 and 2R15GM114751-02 (for H. Y. Liu). A high-performance computing infrastructure at Michigan Technological University was used for the calculations. Shuai Xia would like to thank Graduate School at Michigan Technological University for a finishing award support.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9tb02302j

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Saxena S, Mathur A and Kakkar P, J. Cell. Physiol, 2019, 234, 19223–19236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjorklund G, Aaseth J, Dadar M and Chirumbolo S, Mol. Neurobiol, 2019, 56, 7032–7044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang ZB, Liu JY, Xu XJ, Mao XY, Zhang W, Zhou HH and Liu ZQ, Biomed. Pharmacother, 2019, 118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alamudi SH and Chang YT, Chem. Commun, 2018, 54, 13641–13653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu XG, Kwok RTK, Lam JWY and Tang BZ, Biomaterials, 2017, 146, 115–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren MG, Zhou K, He LW and Lin WY, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2018, 6, 1716–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zielonka J, Joseph J, Sikora A, Hardy M, Ouari O, Vasquez-Vivar J, Cheng G, Lopez M and Kalyanaraman B, Chem. Rev, 2017, 117, 10043–10120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun N, Malide D, Liu J, Rovira II, Combs CA and Finkel T, Nat. Protoc, 2017, 12, 1576–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin WY, Yuan L, Cao ZM, Feng YM and Song JZ, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2010, 49, 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li XY, Hu YM, Li XH and Ma HM, Anal. Chem, 2019, 91, 11409–11416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang YY, Li Z, Hu W and Liu ZH, Anal. Chem, 2019, 91, 10302–10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu YC, Teng LL, Chen LL, Ma HC, Liu HW and Zhang XB, Chem. Sci, 2018, 9, 5347–5353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gui LJ, Yuan ZW, Kassaye H, Zheng JR, Yao YX, Wang F, He Q, Shen YZ, Liang L and Chen HY, Chem. Commun, 2018, 54, 9675–9678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu F, Cai XL, Manghnani PN, Kenry, Wu WB and Liu B, Chem. Sci, 2018, 9, 2756–2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Zhou J, Wang LL, Hu XX, Liu XJ, Liu MR, Cao ZH, Shangguan DH and Tan WH, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 12368–12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu MY, Li K, Liu YH, Yu KK, Xie YM, Zhou XD and Yu XQ, Biomaterials, 2015, 53, 669–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang YB, Xia S, Mikesell L, Whisman N, Fang MX, Steenwinkel T, chen K, Luck LR, Werner T and Liu HY, ACS Appl. Bio Mater, 2019, 2, 4986–4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MH, Park N, Yi C, Han JH, Hong JH, Kim KP, Kang DH, Sessler JL, Kang C and Kim JS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 14136–14142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang WJ, Kwok RTK, Chen YL, Chen SJ, Zhao EG, Yu CYY, Lam JWY, Zheng QC and Tang BZ, Chem. Commun, 2015, 51, 9022–9025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan L, Lin WY, Zheng KB, He LW and Huang WM, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2013, 42, 622–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan L, Lin WY, Yang YT and Chen H, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 1200–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia S, Wang JB, Bi JH, Wang X, Fang MX, Phillips T, May A, Conner N, Tanasova M, Luo FT and Liu HY, Sens. Actuators, B, 2018, 265, 699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia S, Fang MX, Wang JB, Bi JH, Mazi W, Zhang YB, Luck RL and Liu HY, Sens. Actuators, B, 2019, 294, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang JB, Xia S, Bi JH, Fang MX, Mazi WF, Zhang YB, Conner N, Luo FT, Lu HP and Liu HY, Bioconjugate Chem., 2018, 29, 1406–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macrae CF, Bruno IJ, Chisholm JA, Edgington PR, McCabe P, Pidcock E, Rodriguez-Monge L, Taylor R, van de Streek J and Wood PA, J. Appl. Crystallogr, 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marenich AV, Cramer CJ and Truhlar DG, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Li X, Caricato M, Marenich AV, Bloino J, Janesko BG, Gomperts R, Mennucci B, Hratchian HP, Ortiz JV, Izmaylov AF, Sonnenberg JL, Williams-Young D, Ding F, Lipparini F, Egidi F, Goings J, Peng B, Petrone A, Henderson T, Ranasinghe D, Zakrzewski VG, Gao J, Rega N, Zheng G, Liang W, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Throssell K, Montgomery JA Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark MJ, Heyd JJ, Brothers EN, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Keith TA, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell AP, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Millam JM, Klene M, Adamo C, Cammi R, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Farkas O, Foresman JB and Fox DJ, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin A, Petersson GA, Frisch MJ, Dobek FJ, Scalmani G and Throssell K, J. Chem. Theory Comput, 2012, 8, 4989–5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtiss LA, McGrath MP, Blaudeau JP, Davis NE, Binning RC Jr. and Radom L, J. Chem. Phys, 1995, 103, 6104–6113. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maro B, Marty MC and Bornens M, EMBO J., 1982, 1, 1347–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang MX, Adhikari R, Bi JH, Mazi W, Dorh N, Wang JB, Conner N, Ainsley J, Karabencheva-Christova TG, Luo FT, Tiwari A and Liu HY, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2017, 5, 9579–9590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YB, Bi JH, Xia S, Mazi W, Wan SL, Mikesell L, Luck RL and Liu HY, Molecules, 2018, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang JB, Xia S, Bi JH, Zhang YB, Fang MX, Luck RL, Zeng YB, Chen TH, Lee HM and Liu HY, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2019, 7, 198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang SW, Chen TH, Lee HM, Bi JH, Ghosh A, Fang MX, Qian ZC, Xie F, Ainsley J, Christov C, Luo FT, Zhao F and Liu HY, ACS Sens., 2017, 2, 924–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vegesna GK, Janjanam J, Bi JH, Luo FT, Zhang JT, Olds C, Tiwari A and Liu HY, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2014, 2, 4500–4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang JT, Yang M, Mazi WF, Adhikari K, Fang MX, Xie F, Valenzano L, Tiwari A, Luo FT and Liu HY, ACS Sens., 2016, 1, 158–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Zhang T, Wang J, Zhang Z, Zhai Y, Yang GY and Sun X, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 2014, 444,182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.