Abstract

Stress cardiomyopathy is an acute reversible heart failure syndrome initially believed to represent a benign condition due to its self-limiting clinical course, but now recognized to be associated with a non-negligible rate of serious complications such as ventricular arrhythmias, systemic thromboembolism, and cardiogenic shock. Due to an increased awareness and recognition, the incidence of stress cardiomyopathy has been rising (15–30 cases per 100,000 per year), although the true incidence is unknown as the condition is likely underdiagnosed. Stress cardiomyopathy represents a form of neurocardiogenic myocardial stunning, and while the link between the brain and the heart is established, the exact pathophysiological mechanisms remain unclear. We herein review the proposed risk factors and triggers for the syndrome and discuss a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment of the patients with stress cardiomyopathy, highlighting potential challenges and unresolved questions.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, stress, Takotsubo

Since its first description in Japan in 1990 (1), Takotsubo syndrome, also known as stress cardiomyopathy, broken heart syndrome, or apical ballooning syndrome, has emerged as an important form of acute reversible myocardial injury characterized by transient regional systolic left ventricular dysfunction (2,3). Takotsubo refers to the classic apical ballooning shape seen in the majority of cases that resembles the octopus trap used in Japan (4). Initially considered a rare event, with greater awareness and recognition the prevalence is currently estimated at 1% to 2% of patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (5,6). Although it was originally believed to represent a benign syndrome due to its self-limiting clinical course and the absence of significant coronary artery disease (CAD), there is a substantial risk of mortality, not dissimilar to that of ACS (7,8). Complications of stress cardiomyopathy, such as acute heart failure (HF), left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), and mitral regurgitation (MR), leading to cardiogenic shock are not infrequent. The purpose of this review is to provide a practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of patients with stress cardiomyopathy and to highlight potential challenges and unresolved questions.

DEFINITION

Stress cardiomyopathy is a clinical syndrome characterized by an acute and transient (<21 days) left ventricular (LV) systolic (and diastolic) dysfunction often related to an emotional or physical stressful event, most often identified in the preceding days (1 to 5 days). The presence of LV regional wall motion abnormalities characteristically extending beyond a single epicardial coronary artery distribution defines the syndrome. The typical pattern of regional LV wall motion abnormality is the apical hypokinesia/akinesia/dis-kinesia (apical ballooning) with basal hyperkinesis. Other forms of systolic dysfunction localized to the base or the midventricular regions have been described, although less frequently (9,10). The presence of a stress cardiomyopathy is suspected on the basis of the clinical context, electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormalities, mild elevation of serum cardiac troponin, significant elevation in serum natriuretic peptide levels (BNP or NT-proBNP), and noninvasive cardiovascular imaging. Coronary angiography is usually performed to exclude an acute obstruction in an epicardial coronary artery. Cases in whom regional wall motion abnormalities that extend beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution, usually in a circumferential distribution, coexist with CAD (bystander CAD), remain consistent with stress cardiomyopathy.

The most widely used diagnostic criteria are Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology diagnostic criteria for Takotsubo Syndrome (11), which have revised the earlier Mayo Clinic Criteria (12). Recently, the International Takotsubo Diagnostic Criteria (InterTAK Diagnostic Criteria) have been proposed (13,14) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for Stress Cardiomyopathy According to Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Mayo Clinic Criteria, and InterTAK Diagnostic Criteria

| Heart Failure Association-European Society of Cardiology Criteria |

|

| International Takotsubo Diagnostic Criteria (InterTAK Diagnostic Criteria) |

|

| Revised Mayo Clinic Criteria |

|

Acute, reversible dysfunction of a single coronary territory has been reported.

Left bundle branch block may be permanent after Takotsubo syndrome, but should also alert clinicians to exclude other cardiomyopathies. T-wave changes and QTc prolongation may take many weeks to months to normalize after recovery of LV function.

Troponin-negative cases have been reported, but are atypical.

Small apical infarcts have been reported. Bystander subendocardial infarcts have been reported, involving a small proportion of the acutely dysfunctional myocardium. These infarcts are insufficient to explain the acute regional wall motion abnormality observed.

Wall motion abnormalities may remain for a prolonged period of time or documentation of recovery may not be possible. For example, death before evidence of recovery is captured.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is recommended to exclude infectious myocarditis and diagnosis confirmation of Takotsubo syndrome.

There are rare exceptions to these criteria, such as those patients in whom the regional wall motion abnormality is limited to a single coronary territory.

It is possible that a patient with obstructive coronary atherosclerosis may also develop stress cardiomyopathy. However, this is very rare in our experience and in the published data, perhaps because such cases are misdiagnosed as an acute coronary syndrome. In both of the above circumstances, the diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy should be made with caution, and a clear stressful precipitating trigger must be sought.

BNP = B-type natriuretic peptide; LBBB = left bundle branch block; LV = left ventricular; NT-BNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The exact pathophysiology of stress cardiomyopathy remains elusive and several mechanisms may be involved. The link between the brain and heart has long been known (15–17), but only recently has this link been explored using neuroimaging approach (18,19). The central autonomic nervous system (CANS) regulates the vital cardiovascular functions. Even before the description of the stress cardiomyopathy as a self-standing syndrome, clinicians had described increased incidence of transient cardiac dysfunction and injury, dynamic ECG changes, and increased risk of arrhythmias in patients with acute stroke, mainly hemorrhagic, or ischemic stroke of the basal ganglia or the brain stem. This phenomenon, referred to as “neurogenic stunning myocardium” (20) was transient, and was also described with electroconvulsive therapy and seizures.

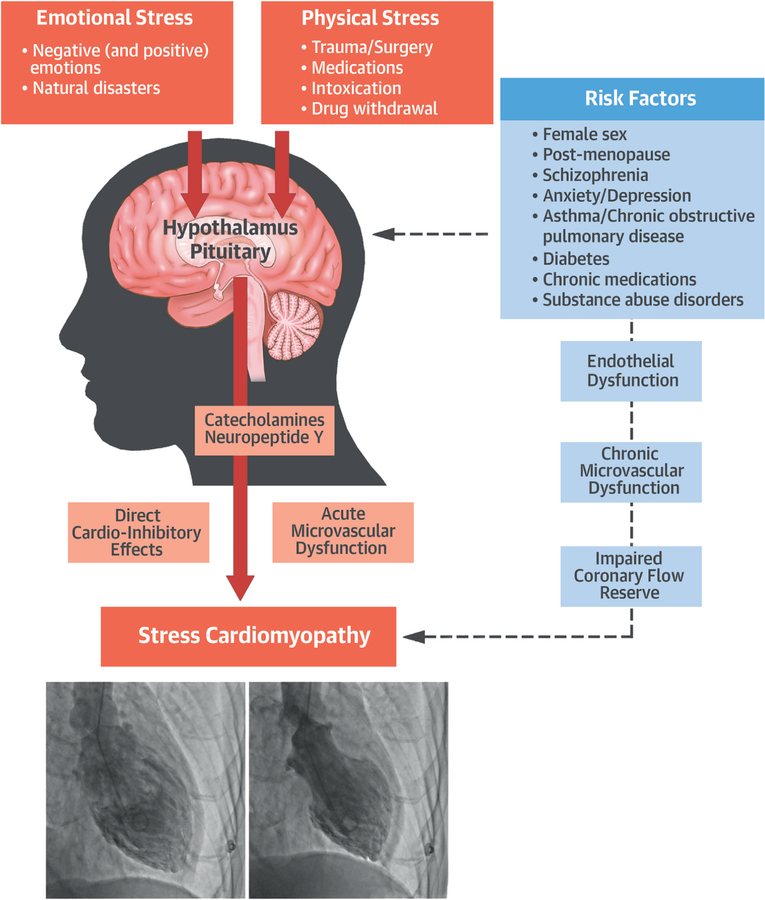

An increase in cerebral blood flow in the hippo-campus, brainstem, and basal ganglia has been shown in the acute phases of stress cardiomyopathy of patients versus control subjects, with a return to normal when the syndrome resolved (15,16). It is unknown, however, how psychological and/or physical stresses may lead to myocardial dysfunction in some cases and not in others. There is a complex neocortical and limbic integration in response to stress through an activation of brainstem noradrenergic neurons and stress-related neuropeptides (i.e., neuropeptide Y [NPY] produced by the arcuate nucleus in the hypothalamus) (Central Illustration). Norepinephrine and NPY are stored in the pre-synaptic terminations of the post-ganglionic sympathetic system. The spillover of norepinephrine and NPY from pre-synaptic terminations at myocardial level following intense stress may induce a direct toxic effect and/or epicardial and microvascular dysfunction (21–25). A parallel hypothesis is for an increase in circulating catecholamines and stress hormones in stress cardiomyopathy (25); this hypothesis, however, is not accepted by others (26). The catecholamine mechanism would be similar to what is seen in pheochromocytoma. However, an increase in circulating catecholamines and stress hormones may also represent a compensatory mechanism secondary to reduced cardiac output and hypotension. Therefore, in predisposed individuals, who may have an enrichment in NPY/norepinephrine granules, an intense stimulation for an adrenergic stimulation may be sufficient to trigger stress cardiomyopathy (25,27), whereas in others, free of such risk factors and/or with stronger coping mechanisms, the psychological or physical stresses would be insufficient to trigger the cardiac stunning (Central Illustration). Also, the mechanisms by which the neuropeptides/neurohormones cause the cardiomyopathy are not clear (18). Norepinephrine and NPY can display direct cardiodepressant effects; however, it has been proposed that the impaired cardiac function is a result of impaired microvascular perfusion leading to a demand-supply mismatch and an ischemic stunning (28,29). As such, risk factors for endothelial dysfunction would predispose to stress cardiomyopathy. Whether the impaired myocardial perfusion seen during episodes of stress cardiomyopathy represents the cause or the effect of the myocardial stunning remains to be determined.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Pathophysiology of Stress Cardiomyopathy.

In a predisposed individual, who may have enrichment in NPY/norepinephrine granules and risk factors for endothelial dysfunction, an intense stimulation for an adrenergic stimulation may be sufficient to trigger stress cardiomyopathy in response to emotional or physical stress. Stress-related neuropeptides stored in the pre-synaptic terminations of postganglionic neurons at level of CANS may suddenly spill at myocardial level, and through a direct catecholamine toxicity and/or microvascular dysfunction, explain the prevailing theory of a neurogenic-mediated mechanism of myocardial stunning.

Medina de Chazal, H. et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(16):1955–71.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although the precise incidence of stress cardiomyopathy is unknown, data from the 2 largest cohorts of patients suggest an incidence of approximately 15 to 30 cases per 100,000 per year in the United States, with similar estimated numbers in Europe (30). The true incidence is likely higher, if one considers that milder forms may not receive medical attention. Moreover, stress cardiomyopathy may be misdiagnosed as an ACS, and it is estimated that 1% to 2% of patients with suspected ACS are eventually diagnosed with stress cardiomyopathy (5).

Stress cardiomyopathy occurs more frequently in postmenopausal women. Three registries of 1,750, 324, and 190 patients with stress cardiomyopathy reported that 90%, 91%, and 92%, respectively, were women, with mean ages of 67, 68, and 66 years, respectively (10,31,32). Postmenopausal women have an increased sympathetic drive and endothelial dysfunction, predisposing to microvascular dysfunction (33). Further, markers of oxidative stress are also increased in postmenopausal women (34). Likewise, postmenopausal women report greater anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances (35,36). Finally, there is an increase in NPY with menopause (37,38). Therefore, the increased sympathetic activity and NPY associated with impaired coronary reserve may lead to greater incidence of stress cardiomyopathy in postmenopausal women. Of note, emotional stress or the absence of identifiable triggers seems to be more common in women, whereas physical stressful triggering events were more common among men (10,31).

TRIGGER FOR STRESS CARDIOMYOPATHY

Emotional and/or physical stress are triggers for stress cardiomyopathy. The most common emotional stressors reported include the death of a loved one, assault and violence, natural disasters, great financial loss, with most involving a sense of doom, danger, and/or desperation (5,39). Episodes of stress cardiomyopathy may, however, also follow unexpected pleasant events, “happy heart syndrome” (40).

Physical stressors reported include acute critical illness, surgery, severe pain, sepsis, and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. In addition, central nervous system disorders, such as seizures, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, encephalitis/meningitis, head trauma, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, and advanced acute lateral sclerosis, have emerged as triggers. These conditions have been referred to as “Takotsubo phenocopies” to differentiate them as conditions of neurogenic stunning myocardium distinct from “classic” stress cardiomyopathy, but they share a common pathophysiology characterized by intense CANS activation (5,22,41–43). A comprehensive list of associated triggers reported in the published data is detailed in Online Table 1.

Obviously, not every subject develops the cardiomyopathy following a stressful event, and stress cardiomyopathy episodes without any identifiable stressful trigger have been described in 30% to 35% of the cohort series (44,45). This finding may be due, in part, to the protective (or maladaptive) influence of psychosocial factors, including individual coping style, existing social supports, and pre-existing mental health comorbidities at the time of the event.

RISK FACTORS

The typical patient with stress cardiomyopathy is a postmenopausal woman who has experienced severe, unexpected emotional stress in the prior 1 to 5 days. This is often superimposed on a background of elevated levels of stress or anxiety, or an anxiety or panic disorder (37–39), but it may also be unheralded Diabetes mellitus has been described as a risk factor for stress cardiomyopathy; it is present in 10% to 25% of patients, and is associated with increased mortality (46). Diabetes mellitus leads to neuroautonomic nerve remodeling and an up-regulation of vasoactive neuropeptides like NPY, which may lead to enhanced susceptibility to stress cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias (46–48). Asthma exacerbation is another possible trigger of stress cardiomyopathy, mainly following medical interventions (short acting ß2 adrenergic receptor agonist, epinephrine and intubation) (49,50). The etiology of stress cardiomyopathy in the course of an asthma attack is not understood. The asthma attack itself may represent an emotional and physical trigger and the β-mimetic drugs could promote stress cardiomyopathy (25,50). A link, however, exists between higher NPY levels and stress-induced asthma, by which these conditions may, on the one hand, trigger stress cardiomyopathy by releasing more NPY in the myocardium, or on the other hand, they may simply reflect conditions of enhanced NPY production (51).

Cannabis use disorder has been identified as a risk factor for stress cardiomyopathy and is associated with a 3-fold higher risk of cardiac arrest (52). Endogenously produced cannabis-like substances (endocannabinoids) have also shown to have cardiovascular effects by reducing cardiomyocyte contractility (53). Cannabinoids induce NPY expression in the arcuate nucleus in the hypothalamus, which is considered to be central in CANS-dependent regulation of cardiac function (54,55). Similarly, subarachnoid hemorrhage and ischemic stroke induce intense endocannabinoid production, possibly being implicated in the neurogenic myocardial stunning (56). Stress cardiomyopathy among patients treated with serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and/or during serotoninergic syndrome support the hypothesis of catecholamine storm and subsequent ventricular dysfunction (57).

CLINICAL SUBTYPES: PRIMARY AND SECONDARY STRESS CARDIOMYOPATHY

Stress cardiomyopathy can be classified according to either primary or secondary form, depending on whether it is the primary reason of care-seeking (primary form) or the patient is already in the health care setting during evaluation or treatment of another critical illness (secondary form). Differentiating these 2 situations is relevant due to their different characteristics and clinical outcomes. In its primary form, patients are usually admitted to a specialized cardiac care unit and are usually treated with aspirin and anticoagulant agents (58). In its secondary forms, patients are already in the health care setting during evaluation or treatment of another critical illness and often present insidiously in a wide range of clinical and surgery settings. In these situations, clinical presentations include arrhythmias, hypotension, acute pulmonary edema, abnormal ECG, or troponin elevation (59), and unless a high degree of suspicion is present, the diagnosis can be missed and the patient can be mismanaged.

ANATOMICAL VARIANTS

Since its first detailed description, stress cardiomyopathy with wall motion abnormalities resembling “Takotsubo” or octopus pot, with a narrow neck and globular lower portion in the apical ballooning form, remains the typical pattern and is present in 75% to 80% of patients (10,60). The apical ballooning syndrome is easily recognized due to its characteristic morphology and is associated with typical complications of apical akinesis (thrombus formation) and of basal hyperkinesis (LVOTO and MR due to systolic anterior movement of the mitral leaflet).

The midventricular ballooning pattern, in which the mid-LV is hypo or akinetic, with normal apical and basal contraction, is present in 10% to 20% of patients and is associated with more severe reduction in cardiac output and cardiogenic shock. The basal or inverted Takotsubo is found in <5% of patients (10,11) and is associated with less severe hemodynamic compromise.

Other rare variants include biventricular dysfunction and isolated right ventricular (RV) compromise, which are associated with severe hemodynamic compromise and shock, and localized focal dysfunction that are more benign in nature and resemble cases of focal myocarditis (Table 2). The reason beyond the different anatomical variants is unclear. The higher β-adrenoceptor density in the apical myocardium may account for the greater susceptibility of the apex to the cardiac sympathetic stimulation, but this finding has never been replicated in humans (7).

TABLE 2.

Anatomical Variants of Stress Cardiomyopathy

| Variant | Prevalence | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Apical ballooning (typical) | 75%–80% | Can be associated with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and/or apical thrombus formation Variable prognosis |

| ||

| Midventricular | 10%–20% | Severe Left ventricular dysfunction Acute heart failure syndrome is common. |

| ||

| Basal or inverted | 5% | Less severe hemodynamic compromise |

| ||

| Biventricular | <0.5% | Severe hemodynamic compromise and cardiogenic shock |

| ||

| Focal dysfunction | Rare | Benign course, more commonly associated with chest pain |

|

CLINICAL FEATURES

The typical patient with stress cardiomyopathy is a postmenopausal woman who presents with acute or subacute onset of chest pain (>75%) and/or shortness of breath (approximately 50%), often with dizziness (>25%) and occasional syncope (5% to 10%) (10,61). In the majority of the cases, the patient has experienced an emotional or physical stress that he/she may not share with the health care provider unless asked. In some cases, the event is rather minor and would go unnoticed if the diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy is not suspected, and the patient is not appropriately questioned.

Chest pain usually has typical characteristics of angina. Shortness of breath is usually the result of pulmonary edema. Dizziness and syncope derived from hypotension and hypoperfusion and may indicate life-threatening cardiogenic shock or ventricular arrhythmias. Presentation with stroke-like symptoms is uncommon. Cardiac arrest due to ventricular arrhythmias is possible (62).

The physical examination of a patient with stress cardiomyopathy generally reveals a patient who is in respiratory distress, tachycardic, hypotensive, cold at touch, with narrow pulse pressure, S3 gallop, jugular vein distention and crackles/rales at the bases and, often, a systolic ejection murmur (due to LVOTO and MR), and, rarely, lower extremity edema.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy is based on the demonstration of a regional LV wall motion abnormality beyond the territory perfused by a single epicardial coronary artery that is reversible in nature and is often associated with an emotional or physical stress. As such, a definite diagnosis cannot be established at presentation because of the need to demonstrate the reversible nature of the condition, although some clinical features are highly predictive of stress cardiomyopathy.

PRE-TEST PROBABILITY.

The presumptive diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy starts with the assessment of the pre-test probability. The InterTAK International Registry Group has developed a simple scoring system that takes into account 5 clinical variables from history and 2 variables from the ECG to create a score that translates into a probability of stress cardiomyopathy (InterTAK diagnostic score) (63) (Table 3). According to this tool, a female patient with a history of psychiatric disorder, presenting with chest pain after an emotional stress, and without ST-segment depression on ECG has a score of 72 and a probability of stress cardiomyopathy of 90%; the same patient without psychiatric disorder or an identifiable stress and with ST-segment depression would have a score of 25 and a probability of 0.3%. As discussed in the prior section, “Risk Factors,” novel factors are being recognized that are not featured in this tool, but should be taken in consideration.

Table 3.

InterTAK Diagnostic Score

| Criteria | Points |

|---|---|

| Female | 25 |

| Emotional trigger | 24 |

| Physical trigger | 13 |

| Absence of ST-segment depression | 12 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 11 |

| Neurologic disorders | 9 |

| QTc prolongation | 6 |

| Diagnosis (Cutoff Value [Range 0–100]) | |

| ≥50 | ≤31 |

| Takotsubo | Acute coronary syndrome |

| (Specificity 95%) | (Specificity 95%) |

ELECTROCARDIOGRAM.

The 12-lead ECG at hospital admission is central in the evaluation of all patients with chest pain, shortness of breath, and/or dizziness. The ECG is abnormal in most patients with stress cardiomyopathy (>95%) (11), usually showing ischemic ST-segment and T-wave changes (11,60). T-wave inversion, often deep and widespread, and significant QT prolongation, usually developing 24 to 48 h after the onset of symptoms or the precipitating stressful trigger, are rather specific of stress cardiomyopathy, and represent 1 of the assessment points in the InterTAK Diagnostic Score Tool (63,64). ST-segment elevation involving precordial leads is also seen only in about 40% of the cases (5,61,65,66), generally leading to emergent coronary angiography. ST-segment depression is uncommon, occurring in <10% of patients, and its presence should suggest an alternate diagnosis of ACS, as also suggested by the InterTAK Diagnostic Score tool (10,63).

QTc prolongation may progress over time to exceed 500 ms, predisposing to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (torsade de pointes) and ventricular fibrillation; as such, every patient with stress cardiomyopathy requires ECG telemetry monitoring for at least 48 to 72 h or until resolution of the QTc prolongation (64).

The ECG has been used as a tool to differentiate between stress cardiomyopathy and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (67). The most differentiating criteria included ST-segment elevation in AVR, which when combined with ST-segment elevation in anteroseptal leads (more than 2 of 3 leads in V1-V2-V3), was 100% specific for stress cardiomyopathy versus ACS, with predictive positive value (PPV) of 100% but negative predictive value (NPV) of 52% and a sensitivity of 12%. In the non-ST-segment elevation setting, ST-segment elevation in AVR combined with concomitant T-inversion in any lead was 100% specific of TS with 100% PPV but also with a low sensitivity (8%) in 1 series (67). The absence of reciprocal changes, the absence of abnormal Q waves, and the sum of ST-segment elevation in leads V4 to V6 more than the sum of ST-segment elevation in leads V1 to V3, have also differentiated stress cardiomyopathy from ACS with high sensitivity and specificity (68). However, due to possible overlap and dynamic ECG changes in most cases, emergency coronary angiography and ventriculography are performed to confirm the underlying diagnosis.

BIOMARKERS.

Cardiac troponin T or I, measured by conventional assays (not high sensitivity), are elevated in >90% of patients (61), and peak troponin levels are generally <10 ng/ml (10), which is substantially lower than in classical ACS. Creatine-kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) is only mildly elevated in most patients with stress cardiomyopathy (58). Typically, there is a discrepancy between the minimal elevation in biomarkers compared with the extensive wall motion abnormalities during the early stage.

Serum cardiac natriuretic peptides (BNP and pro-BNP) are almost always elevated, with higher levels correlating with the degree of ventricular wall motion abnormalities (26,69) and usually greater than those observed with ACS (10). The peak occurs at 48 h after presentation, and with elevation up to 3 months (69). Due to the marked difference among troponin, CKMB, and BNP elevation, the BNP/troponin and BNP/CK-MB ratios may help to differentiate between stress cardiomyopathy and ACS with greater accuracy than BNP alone (70). Markers of renal function and lactate are monitored as a surrogate for cardiac output.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY.

Transthoracic echocardiography with color and tissue Doppler is the preferred noninvasive imaging test for patients with suspected stress cardiomyopathy (11). A global LV akinesis/dyskinesis with a classic circumferential pattern involving the entire apex (most common) or the midventricular or basal segments would be suggestive of stress cardiomyopathy. The diagnosis is generally straightforward in its classic apical ballooning form. Apical ballooning is often associated with other suggestive features, such as LVOTO due to basal hypercontractility, and MR due to systolic anterior movement of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve. It can be, however, very challenging to differentiate apical ballooning from anteroapical stunning due to myocardial ischemia in the case of left anterior descending artery occlusion, especially if the artery is large and wraps around the apex. It can be also deceiving to see diffuse wall motion abnormalities in patients with multivessel CAD. Because of the dynamic nature of stress cardiomyopathy, a comprehensive serial echocardiographic examination should be systematically performed to evaluate for the occurrence of complications and eventually ensure the reversal of wall motion abnormalities.

CORONARY ANGIOGRAPHY.

Most patients with suspected stress cardiomyopathy undergo emergent or urgent coronary angiography to rule out ACS. However, not every patient with suspected stress cardiomyopathy needs an invasive assessment for coronary atherothrombosis. The decision to proceed with a coronary angiogram should be made on a case-by-case basis. It is also important to consider that many elderly patients will have underlying CAD that may not be causing acute ischemia (bystander disease) and thus would not represent ACS (71). Finally, whether 1 patient can have both ACS and stress cardiomyopathy is still object of discussion, but considering how common ACS is and that it represents both an emotional and physical stress, this option needs to be considered (72,73). In most cases of suspected stress cardiomyopathy, a ventriculography is performed unless contraindicated (i.e., suspected apical thrombus), as it is diagnostic for the syndrome and is particularly useful for the midventricular form, which may be more difficult to visualize at echocardiography.

CARDIAC MAGNETIC RESONANCE.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) allows visualization of myocardial edema, inflammation, and scarring with the use of delayed gadolinium enhancement (DGE). CMR also provides more complete views of the RV than echocardiography (74). During the acute phase of stress cardiomyopathy, T2-weighted CMR shows myocardial edema as high-signal intensity in the acute phase (71). In stress cardiomyopathy, the area of edema usually matches with the area of wall motion abnormalities differently from that seen in ACS, in which edema distribution follows the epicardial coronary artery territory, or myocarditis, in which the edema tends to be basal, lateral, and subepicardial (75). In general, the absence of macroscopic fibrosis as documented by the lack of a DGE is a classic hallmark for stress cardiomyopathy (76), helping to differentiate it from ACS—where DGE is always present to some degree— and myocarditis, where 88% of patients show a patchy type of DGE (77). However, there have been some cases of DGE in stress cardiomyopathy in the acute phases (up to 40% in one series), but even when DGE is present, it is frequently less bright than the DGE associated with myocardial infarction (signal intensity <5 SDs) with concentric transmural extension to the mid and apical LV wall (75,78,79). The difference between these studies may be in the threshold of signal intensity used to define the presence of DGE, as the signal intensities are lower in stress cardiomyopathy than in these other conditions (74,78). Furthermore, especially in the setting of apical ballooning pattern, delayed enhancement CMR demonstrates higher sensitivity and specificity than echocardiography in detecting LV thrombi and differentiating thrombi from surrounding myocardium (80).

CORONARY COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY.

Coronary computed tomography angiography may be considered in patients with limited acoustic windows and contraindication for CMR. The main application is in evaluating epicardial coronary arteries to exclude high-grade stenosis (81). Coronary computed tomography angiography has been proposed as a noninvasive imaging modality alternative to angiography to exclude coronary culprit lesions in selected stable patients and a convincing clinical and echocardiographic picture of stress cardiomyopathy (11,78,79,82).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

When approaching a patient with suspected stress cardiomyopathy, it is important to consider the differential diagnosis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Differential Diagnosis of Stress Cardiomyopathy

| Clinical Presentation | ECG Findings | Echocardiography | Coronary Angiography | CMR | Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress cardiomyopathy | |||||

| Chest pain, dyspnea, syncope, arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death. Usually in older female patient triggered by an emotional or physical stress | ST-segment elevation, T-wave inversion, QTc prolongation | Apical, midventricular, basal, or focal hypo/akinesia | Absence of obstructive CAD or angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture | Edema: transmural ventricular edema in the areas of ventricular dysfunction Cine-CMR: regional wall motion abnormalities according to the anatomical patterns No DGE (cut-off >5 SD) |

NT-proBNP and BNP ↑↑ Troponin and CK-MB mildly ↑ |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| Chest pain, dyspnea, arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death | ST-segment elevation, ST-segment depression and/or T-wave inversion | Regional wall motion abnormalities according to epicardial coronary artery distribution | Coronary artery disease with acute plaque rupture, thrombus formation, and coronary dissection | Edema: Subendocardial or transmural at sites of wall motion abnormalities. Cine-CMR: Regional wall motion abnormalities according to epicardial coronary artery distribution DGE: Bright DGE, typically subendocardial or transmural in an epicardial coronary artery distribution |

Troponin and CK-MB levels ↑↑ BNP and NT-proBNP mildly ↑ |

| Myocarditis | |||||

| Chest pain, dyspnea, acute heart failure, sudden cardiac death. Usually in young or middle-age populations, often preceded by an upper respiratory infection or enteritis | Nonspecific ST-T-wave changes (diffuse ST-segment elevation is usually seen in myopericarditis) | Global systolic dysfunction (sometimes regional or segmental). Pericardial involvement may be also present. | Absence of obstructive CAD or angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture | Edema: Subepicardial, basal and lateral Cine-CMR: Usually global unless regional edema/LGE is severe DGE: Low intensity or bright DGE is often present with a focal, “patchy,” subepicardial or midventricular noncoronary distribution |

Troponin and CK-MB mildly ↑ BNP and NT-proBNP mildly ↑ |

CAD = coronary artery disease; CK-MB = creatine kinase-myocardial band; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; DGE = delayed gadolinium enhancement; ECG = electrocardiography; HF = heart failure; RV = right ventricle; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES.

Clinicians should be aware of stress cardiomyopathy due to overlap with ACS in their clinical presentation and ECG abnormalities. ACS due to atherosclerotic plaque complications needs to be promptly recognized, and coronary angiography may be useful to demonstrate that the extent and location of the epicardial coronary artery lesion(s) does not match the territory of the observed wall motion abnormalities. In addition, among patients with ACS, vasospastic angina or Printzmetal angina represents an important epicardial cause of myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary atherosclerosis (83). Coronary artery vasospasm usually occurs at a localized segment of an epicardial artery, but sometimes involves 2 or more segments of the same (multifocal spasm) or of different (multivessel spasm) coronary arteries. Spasm can occur in angiographically normal coronary vessels, but more commonly occurs at the site of atherosclerotic plaques of variable severity. Some authors documented spontaneous or induced coronary artery spasm in stress cardiomyopathy, suggesting the possible causative role of the sustained epicardial coronary artery into pathogenesis (84) by including it in the spectrum of vasospastic angina. Different from stress cardiomyopathy, vasospastic angina is characterized by episodes of angina at rest during the night or early in the morning of much shorter duration, and a history of repetitive episodes over a period of weeks or months associated with diffuse ST-segment elevation. It is uncommon, but possible, for ACS and stress cardiomyopathy to coexist; this should be considered when there is a clear culprit coronary artery lesion, yet the regional wall motion abnormalities are out of proportion to the CAD extending beyond one district, often in a circumferential pattern (72,73).

CARDIOMYOPATHY ASSOCIATED WITH PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA.

Pheochromocytoma is a neuroendocrine catecholamine-secreting tumor, originating from chromaffin cells within the adrenal medulla or extra-adrenal paraganglia associated with paroxysmal elevation in blood pressure, headache, sweating, palpitations, chest pain, and panic attack. Several catecholamine-induced cardiovascular complications have been described, including a cardiomyopathy with global dysfunction. Symptoms in patients with pheochromocytoma are generally chronic or subacute. Stress cardiomyopathy and pheochromocytoma may coexist, and it is easy to imagine that chronically elevated circulating catecholamines may be a risk factor for stress cardiomyopathy (85,86). To further complicate the picture, occasionally patients with pheochromocytoma may present with acute lymphocytic myocarditis and small area of focal myocardial fibrosis with DGE detected by CMR (87).

ACUTE MYOCARDITIS.

Myocarditis may present with clinical symptoms and chest pain or signs of congestive HF or in a subacute pauci-symptomatic form. An elevation in cardiac biomarkers associated with ECG abnormalities and imaging findings of global systolic dysfunction are often seen, although the pattern of wall motion abnormality may be regional or segmental, usually affecting the inferolateral wall. The pattern of dysfunction is unlikely to be one of apical ballooning or of basal hypokinesis (inverted Takotsubo). CMR is a useful tool to confirm the diagnosis, and the pattern of DGE at CMR is useful to distinguish myocarditis from stress cardiomyopathy. In myocarditis, DGE preferentially involves the epicardium and mid-myocardium with sparing of the endocardium, whereas in stress cardiomyopathy, DGE is often absent.

COMPLICATIONS

In stress cardiomyopathy, left ventricular function returns to normal within a few weeks; however, several complications may occur before the systolic function recovers, and the in-hospital mortality is as high as 5% (10,30,31,88,89).

ACUTE HF AND CARDIOGENIC SHOCK.

Systolic HF is the most common complication in the acute phase, affecting 12% to 45% of patients (5,12,41,88). Independent predictors are advanced age, lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at presentation, higher admission and peak troponin levels, midventricular pattern, RV involvement, and a physical (vs. emotional) stressor. Patients with acute HF present with shortness of breath, dizziness, occasional syncope, tachycardia, and lactic acidosis. Acute HF may be the result of complications such as LVOTO and MR. In absence of complications, the echocardiogram shows severely reduced stroke volume due to a reduced LVEF in a non-dilated LV.

LV OUTFLOW TRACT OBSTRUCTION.

In the classic apical ballooning forms, the hypercontractility of the basal LV segments can lead to LVOTO and mitral valve systolic anterior motion due to Venturi effect, which leads to MR and occurs in 14% to 25% of patients (90,91). These cases are the most severe and the most difficult to treat, because the presence of LVOTO and MR further impedes LV systole. It is important to determine the presence of LVOTO, because inotropic agents may worsen the obstruction and cardiogenic shock. The presence of obstruction can be suspected by the presence of an ejection systolic murmur with loud S2, and it is visualized at Doppler echocardiography or at pressure waveform assessment at pull-back after ventriculography. An instantaneous gradient >25 mm Hg is considered hemodynamically significant, and a gradient ≥40 is associated with high risk.

ARRHYTHMIAS.

Arrhythmias occur in nearly one-quarter of patients. Atrial fibrillation has been reported in about 5% to 15% of patients (92,93) and is associated with lower LVEF and higher incidence of cardiogenic shock (94). Ventricular arrhythmias occur in 4% to 9% of patients during the acute phase (92,93). Torsade de pointes complicating stress cardiomyopathy is observed in the setting of QT interval prolongation >500 ms (95). Other arrhythmias are less frequent (93). The risk of arrhythmias appears to be elevated until the ECG remains abnormal with T-wave inversion and/or QT remains prolonged and LVEF remains depressed.

SYSTEMIC THROMBOEMBOLISM.

LV thrombus formation is a known complication, especially in its apical forms, which can lead to embolization and stroke (occurring in 2% to 9% of cases) (92,96,97). The highest risk of thrombi is at 2 to 5 days after symptom onset, when LV function is still depressed (96,97). Thrombus may resolve with 2 weeks of anticoagulation; however, a late occurrence has also been described (98), highlighting the importance of follow-up echocardiography in patients diagnosed with stress cardiomyopathy. Cerebrovascular embolic events may occur in up to 17% of patients in the presence of LV thrombi (97). For this reason, all patients with stress cardiomyopathy and apical ballooning or other large areas of wall motion abnormality should be considered for systemic anticoagulation until LVEF recovers.

INTRAMYOCARDIAL HEMORRHAGE AND RUPTURE.

Intramyocardial hemorrhage and ventricular wall rupture have been reported in patients in stress cardiomyopathy and reflect severe parcellar ischemia-reperfusion injury. These cases are very rare, and are generally diagnosed postmortem (62,99). Factors associated with hemorrhage and rupture are advanced age, hypertension, persistent ST-segment elevation, and lower frequency of β-blocker use (99).

MANAGEMENT

To date, there have been no randomized trials to define the optimal management of patients with suspected stress cardiomyopathy. The goal of treatment is supportive care to sustain life and to minimize complications until full recovery, which usually occurs within a few weeks. In mild cases, either no treatment or a short course of limited pharmacological therapy may be sufficient. In severe cases complicated by progressive circulatory failure, some patients need to be considered for mechanical circulatory support as a bridge to recovery.

ECG MONITORING.

As a general consideration, patients need admission to an acute cardiac or medical unit with continuous ECG monitoring, given the risk of arrhythmias, particularly in the setting of prolonged QTc interval. In the absence of QT prolongation or arrhythmias, monitoring for 48 h is considered sufficient.

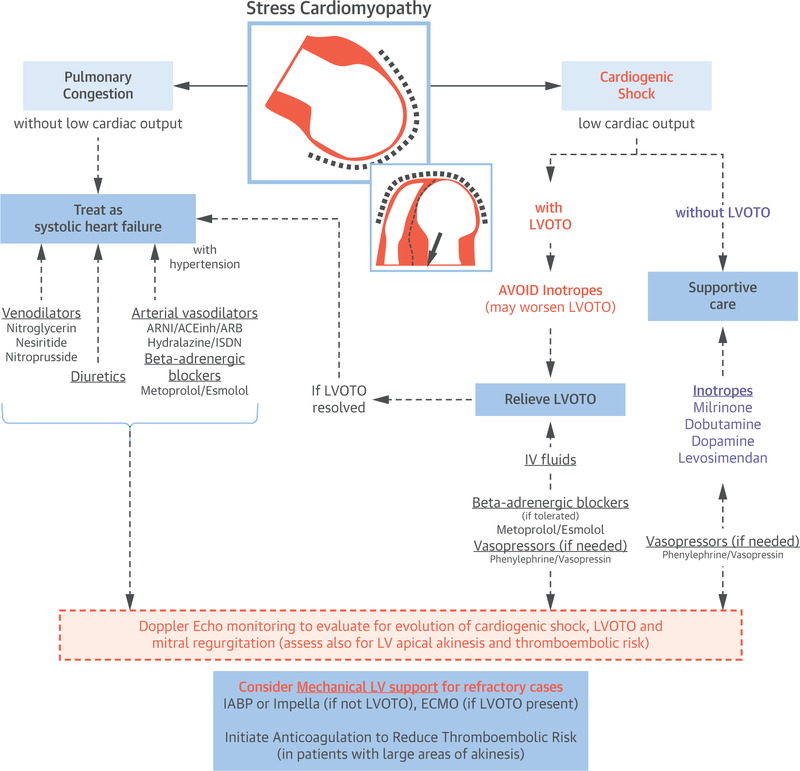

TREATMENT OF HF.

Treatment of HF in patients with stress cardiomyopathy is based on relief of congestion and hemodynamic support in case of low cardiac output state. It is essential to determine the pattern of cardiomyopathy and the presence or absence of LVOTO, which is usually obtained through transthoracic echocardiography. For patients with pulmonary congestion and without hypotension or signs of low cardiac output, the treatment is aimed at reducing venous return with venodilators (i.e., nitroglycerin, nitroprusside, or nesiritide) and with diuretic agents. Arterial vasodilators can be used in patients with systemic arterial hypertension; however, caution is needed to avoid worsening of LVOTO. Low-dose β-adrenergic receptor blockers can be added to treat hypertension in patients who are hemodynamically stable, and they may be particularly useful in cases with LVOTO, as they can reduce basal hypercontractility and may relieve obstruction.

For patients with hypotension and shock, the treatment differs substantially based on where there is evidence of LVOTO or not. In the absence of obstruction, drugs with positive inotropic action (i.e., dobutamine, milrinone, dopamine, or levosimendan) can be considered to increase cardiac output; however, even if there is no LVOTO at baseline, a short-term follow-up assessment is needed to ensure that the addition of an inotrope did not cause obstruction to occur. If inotropic agents are not sufficient, vasopressor drugs (i.e., phenylephrine, norepinephrine, or vasopressin) should be considered at the lowest possible dose and as a temporizing agent as a bridge to mechanical support with a left ventricular assist device or as a bridge to recovery. Aortic counterpulsation with the intra-aortic balloon pump (AutoCAT 2 WAVE, Arrow, Limerick, Pennsylvania) (100) and percutaneous left ventricular assist device through Impella (Abiomed, Danvers, Massachusetts) (101) are well suited to provide temporary support.

For patients with shock and LVOTO with or without MR, treatment is very challenging. Inotropic agents need to be avoided as they are likely to further increase obstruction by augmenting basal hyper-contractility. Indeed, if the patient is already on inotropic drugs, then a reduction in dose or suspension is indicated and intravenous fluids given, as these actions may reduce obstruction and favor resolution. If severe LVOT is present and the patient is not bradycardic, the use of a low dose of short-acting β-adrenergic receptor blocker (i.e., esmolol, metoprolol) can be attempted to reduce the LVOTO (102), which may result in an improvement in cardiac output. In case of shock with LVOTO, the use of peripherally acting vasopressor drugs (i.e., phenylephrine or vasopressin) may be indicated, as it increases blood pressure without increasing LV obstruction; however, these agents may further worsen cardiac output if they fail to improve LVOTO. If medical therapy is not sufficient, a mechanical cardiac assist device should be considered. For the more severe cases of shock, support is often provided by means of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (103). Figure 1 shows the proposed treatment algorithm.

FIGURE 1. Acute Treatment of Patients With Stress Cardiomyopathy and Hemodynamic Compromise.

In patients with no hemodynamic instability and pulmonary congestion, treatment is directed to relief congestion with diuretic agent and vasodilators. Arterial vasodilators and β-adrenergic blockers are useful especially if hypertension is present. For patients with hemodynamic instability (hypotension/shock), treatment depends on the presence of LVOTO obstruction. In the absence of LVOTO, inotropic agents, and if not sufficient, mechanical left ventricular assist devices (IABP, Impella) should be considered. In the presence of LVOTO, intravenous fluids and low dose of short-acting β-adrenergic blockers (i.e., esmolol or metoprolol) may be used with caution to reduce the LVOTO or peripherally active vasopressor drugs (i.e., phenylephrine or vasopressin) to maintain adequate perfusion pressure as a temporizing solution to LVOTO resolution or mechanical support. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is used as a mechanical cardiac assist device for refractory cases of stress cardiomyopathy with LVOTO or biventricular failure. ACEinh = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB = angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARN = angiotensin II receptor blocker neprilysin inhibitors; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pump; ISDN = isosorbide dinitrate; LVOTO = left ventricular out flow tract obstruction.

PREVENTION OF ARRHYTHMIAS.

Large registries have failed to show any benefit of β-adrenergic receptor blockers on in-hospital outcomes; however, no randomized clinical trials have been completed. Treatment with β-blockers may protect against malignant arrhythmias (104) and cardiac rupture (99).

PREVENTION OF THROMBOEMBOLISM.

The low-flow state associated with akinesis and the procoagulant state associated with the acute phase of stress cardiomyopathy (105) are such that up to 10% of patients with stress cardiomyopathy develop ventricular thrombi and are at high risk for thromboembolic events. There are no randomized controlled trials on this topic, and the best strategy is not defined. Systemic anticoagulation should be considered in patients with large areas of akinesis and continued until the LVEF has recovered. For those patients with thrombus formation, treatment is recommended for 3 months.

PREVENTION OF RECURRENCE AND CHRONIC TREATMENT.

Although stress cardiomyopathy is reversible, the syndrome is also recurrent. The average recurrence rate is reported as 2% to 4% per year (106). Recurrence as soon as 4 days (107) and as late as 10 years (108) has been described. It is noteworthy that it may recur as a different anatomical variant in the same patient (109). There is currently no evidence to guide the long-term management, including recurrence prevention, of patients after an episode of stress cardiomyopathy, including a meta-analysis showing a lack of efficacy of common HF therapies (110). Nevertheless, many experts advocate for the use of ß-blockers in patients with increased sympathetic tone, ongoing cardiac symptoms, persistent anxiety, or recurrent episodes (11). In a retrospective analysis of a large international registry, the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers showed a marginal benefit at 1-year survival (10). Calcium-channel blockers have been associated—in retrospective nonrandomized studies—with a shorter and a faster recovery (111) in 1 series. Given the high frequency of mental health comorbidities (particularly anxiety, depression, and substance misuse), attention should also be given to assessment (and subsequent referral to treatment) for psychiatric problems and/or substance abuse that may persist and contribute to risk of recurrence and long-term outcomes.

PROGNOSIS

Stress cardiomyopathy has an in-hospital mortality of up to 5% (10,30,88,89,112). Most in-hospital deaths occurred among patients with an unstable presentation, including cardiac arrest or cardiogenic shock. Recovery of LV contraction is gradual, generally occurring over 1 to 2 weeks, although the process may be rapid within 48 h or delayed up to 6 weeks (113).

Recurrences are common, 2% to 4% per year and up to 20% at 10 years; even after recovery of LVEF, in contrast to previous perception, patients who have experienced stress cardiomyopathy may experience symptoms such as fatigue (74%), shortness of breath (43%), chest pain (8%), palpitations (8%), and exercise intolerance in comparison with control subjects with no previous stress cardiomyopathy. In addition, cardiac structural abnormalities (e.g., impaired LV strain patterns) and metabolic alterations have been described (114). Patients with prior episodes of stress cardiomyopathy have an increased prevalence of anxiety disorders as a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (115,116). Therefore, a better understanding of the mechanisms and the development of therapeutic interventions are required to improve the outcome of patients with stress cardiomyopathy.

STRESS CARDIOMYOPATHY IN YOUNG INDIVIDUALS AND MEN

Stress cardiomyopathy in young individuals (<45 years of age) and male patients is rather infrequent (Table 5). In the largest reported series (NIS-USA) including 6,837 cases of stress cardiomyopathy, 1.9% of the cases were men or younger women (<35 years of age) (44). Few case reports have been published, and some common characteristics seem to be related to this age group. Most cases were associated with drug abuse, alcohol, and marijuana (52,62,117) and stimulants (cocaine [118] and methamphetamines [119]), or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol (120–122) and opioids (123,124), highlighting the importance for emergency physicians to be aware of this when assessing younger patients with HF. Young women presented also a higher rate of psychiatric comorbidities and a greater propensity for recurrence in a series (125). Atypical patterns of LV dysfunction (basal or mid-ventricular) are more common in young individuals (119,126–128), further suggesting differences in the pathophysiology of stress cardiomyopathy of the young (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Stress Cardiomyopathy in Young Individuals

| Epidemiology |

| Rare in younger than age 60 yrs |

| <10% in ≤55 yrs of age |

| <2% in ≤35 yrs of age |

| Comorbidities |

| Psychiatric disorders |

| Schizophrenia |

| Anorexia nervosa |

| Triggers |

| Often physical triggers |

| Pregnancy/delivery |

| Medications (catecholamines/anesthetics) |

| Drugs of abuse (cannabis/amphetamines) |

| Anatomical Pattern/Variant |

| More often atypical forms |

| Basal (inverted Takotsubo) |

| Midventricular |

| Prognosis |

| High risk |

| High risk of arrhythmias |

| Hemodynamic instability |

| Greater propensity for recurrence |

UNRESOLVED ISSUES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There remain many unanswered questions in this complex syndrome. Perhaps the most urgent of all is to better understand the risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms involved, as well as the clinical physiology of the EF-recovered Takotsubo patient, to firmly establish what type of care these patients require long-term.

The sex predilection requires further probing into cardiac-endocrine pathways to ascertain why this condition appears to affect mostly women. Finally, large epidemiological studies are needed to define the physical and mental illnesses/personality profiles of this population and their families, as this may provide important clues on patterns of genetic/environmental susceptibilities.

In terms of diagnosis, with the exceptions of coronary angiography performed in the acute setting, there are no clinical, radiological, or laboratory characteristics that allow clinicians to diagnose this syndrome with certainty and to withhold urgent reperfusion therapy. Elucidating these aspects might be beneficial when considering those centers with limited angiography availability.

Several therapeutic options are available for the treatment of the acute phase of stress cardiomyopathy. Despite any presumed clinical efficacy, there is a gap in evidence coming from randomized and adequately powered studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Stress cardiomyopathy is an acute cardiac disorder with a transient left ventricular wall motion abnormality, and it must be promptly differentiated from ACS for appropriate management. Although it has gained worldwide recognition, there remains much to learn regarding the epidemiology and underlying pathophysiology. Additional randomized and controlled trials are warranted to identify the optimal diagnostic methods and treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author Disclosures: Dr. Moeller has received grant funding from Indivior. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CANS

central autonomic nervous system

- CK-MB

creatine kinase-myocardial band

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- DGE

delayed gadolinium enhancement

- ECG

electrocardiography

- HF

heart failure

- LV

left ventricle

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVOTO

left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- MR

mitral regurgitation

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- RV

right ventricle

Footnotes

APPENDIX

For a supplemental table and references, please see the online version of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sato H, Tateishi H, Dote K, et al. Tako-tsubo like left ventricular dysfunction due to multivessel coronary spasm In: Kodama K, Haze K, Hori M, editors. Clinical Aspects of Myocardial Injury: From Ischemia to Heart Failure. Tokyo: Tokio Kagakuhyoronsha Publ Co., 1990:56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurst RT, Prasad A, Askew JW, Sengupta PP, Tajik AJ. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a unique cardiomyopathy with variable ventricular morphology. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2010;3:641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medeiros K, O’Connor MJ, Baicu CF, et al. Systolic and diastolic mechanics in stress cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2014;129:1659–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, et al. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2002;143: 448–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurowski V, Kaiser A, Von Hof K, et al. Apical and midventricular transient left ventricular dysfunction syndrome (Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy): frequency, mechanisms, and prognosis. Chest 2007;132:809–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyon AR, Rees PSC, Prasad S, Poole-Wilson PA, Harding SE. Stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy—a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunning. Nat Clin Pr Cardiovasc Med 2008;5:22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tornvall P, Collste O, Ehrenborg E, Järnbert-Petterson H. A case-control study of risk markers and mortality in takotsubo stress cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1931–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, et al. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015;373:929–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B, et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a position statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bybee K, Kara T, Prasad A, Lerman A, Barsness GW, Wright RS. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2004;141: 858–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghadri J-R, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (part I): clinical characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and pathophysiology. Eur Hear J 2018;39:2032–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghadri J-R, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (part II): diagnostic workup, outcome and management. Eur Hear J 2018;39: 2047–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weintraub BM, McHenry LC. Cardiac abnormalities in subarachnoid hemorrhage: a resume. Stroke 1974;5:384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samuels MA. The brain-heart connection. Circulation 2007;116:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollick C, Cujec B, Parker S, Tator C. Left ventricular wall motion abnormalities in subarachnoid hemorrhage: an echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988;12:600–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki H, Matsumoto Y, Kaneta T, et al. Evidence for brain activation in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2014;78:256–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein C, Hiestand T, Ghadri J-R, Templin C, Jäncke L, Hänggi J. Takotsubo syndrome– predictable from brain imaging data. Sci Rep 2017;7:5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biso S, Wongrakpanich S, Agrawal A, Yadlapati S, Kishlyansky M, Figueredo V. A review of neurogenic stunned myocardium. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2017;2017:5842182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Buono M, Carbone S, Abbate A. Comment on Stiermaier et al. prevalence and prognostic impact of diabetes in takotsubo syndrome: insights from the international, multicenter GEIST Registry. Diabetes Care 2018;41:1084–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelliccia F, Kaski JC, Crea F, Camici PG. Pathophysiology of Takotsubo syndrome. Circulation 2017;135:2426–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonnino C, Van Tassell BW, Toldo S, Del Buono MG, Moeller FG, Abbate A. Lack of soluble circulating cardiodepressant factors in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin 2017; 208:170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akashi YJ, Goldstein DS, Barbara G, Ueyama T. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation 2008;118: 2754–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wittstein I, David RT. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med 2005;352:539–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madhavan M, Borlaug BA, Lerman A, Rihal CS, Prasad A. Stress hormone and circulating biomarker profile of apical ballooning syndrome (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy): insights into the clinical significance of B-type natriuretic peptide and troponin levels. Heart 2009;95:1436–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spinelli L, Trimarco V, Di Marino S, Marino M, Iaccarino G, Trimarco B. L41Q polymorphism of the G protein coupled receptor kinase 5 is associated with left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome. Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12:13–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galiuto L, De Caterina AR, Porfidia A, et al. Reversible coronary microvascular dysfunction: a common pathogenetic mechanism in apical ballooning or tako-tsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Caterina AR, Leone AM, Galiuto L, et al. Angiographic assessment of myocardial perfusion in Tako-Tsubo syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2013;168: 4717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brinjikji W, El-Sayed AM, Salka S. In-hospital mortality among patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a study of the National Inpatient Sample 2008 to 2009. Am Heart J 2012;164:215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider B, Athanasiadis A, Stöllberger C, et al. Gender differences in the manifestation of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2013; 166:584–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Citro R, Rigo F, Previtali M, et al. Differences in clinical features and in-hospital outcomes of older adults with tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:93–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitale C, Mendelsohn ME, Rosano GMC. Gender differences in the cardiovascular effect of sex hormones. Nat Rev Cardiol 2009;6:532–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sánchez-Rodríguez MA, Castrejón-Delgado L, Zacarías-Flores M, Arronte-Rosales A, Mendoza-Núñez VM. Quality of life among post-menopausal women due to oxidative stress boosted by dysthymia and anxiety. BMC Womens Health 2017;17:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang YF, Cyranowski JM, Brown C, Matthews KA. Major depression during and after the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Psychol Med 2011;41:1879–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soares CN, Zitek B. Reproductive hormone sensitivity and risk for depression across the female life cycle: a continuum of vulnerability? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2008;33:331–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escobar CM, Krajewski SJ, Sandoval-Guzmán T, Voytko M Lou, Rance NE. Neuropeptide Y gene expression is increased in the hypothalamus of older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2338–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wyon Yvonne, Spetz Anna-Clara, Theodorsson E. Concentrations of calcitonin gene-related peptide and neuropeptide Y in plasma increase during flushes in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2000;7:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR, et al. Natural history and expansive clinical profile of stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghadri JR, Sarcon A, Diekmann J, et al. Happy heart syndrome: role of positive emotional stress in takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J 2016;37: 2823–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Zenovich AG, et al. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation 2005;111:472–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee VH, Connolly HM, Fulgham JR, Manno EM, Brown RD, Wijdicks EFM. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: an underappreciated ventricular dysfunction. J Neurosurg 2006;105:264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porto I, Della Bona R, Leo A, et al. Stress cardiomyopathy (tako-tsubo) triggered by nervous system diseases: a systematic review of the reported cases. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:2441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deshmukh A, Kumar G, Pant S, Rihal C, Murugiah K, Mehta JL. Prevalence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States. Am Heart J 2012;164:66–71.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Summers MR, Prasad A. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: definition and clinical profile. Heart Fail Clin 2013;9:111–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stiermaier T, Santoro F, El-battrawy I, et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of diabetes in takotsubo syndrome: insights from the international, multicenter GEIST Registry. Diabetes Care 2018;1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madias JE. Low prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with Takotsubo syndrome: a plausible “protective” effect with pathophysiologic connotations. Eur Hear Journal Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;5:164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Del Buono M, Carbone S, Abbate A. Diabetes and takotsubo cardiomyopathy: is there a causal link? Diabetes Care 2018;41:e121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saito N, Suzuki M, Ishii S, et al. Asthmatic attack complicated with takotsubo cardiomyopathy after frequent inhalation of inhaled corticosteroids/long-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists. Intern Med 2016;55:1615–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pontillo D, Patruno N, Stefanoni R. The takotsubo syndrome and bronchial asthma: the chicken or the egg dilemma. J Cardiovasc Med 2011;12:149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wheway J, Herzog H, Mackay F. NPY and receptors in immune and inflammatory diseases. Curr Top Med Chem 2007;7:1743–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh A, Agrawal S, Fegley M, Manda Y, Nanda S, Shirani J. Marijuana (cannabis) use is a independent predictor of stress cardiomyopathy in younger men. Circulation 2016;134:A14100. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pacher P, Bátkai S, Knos G. Cardiovascular pharmacology of cannabinoids. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2005;168:599–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bakkali-Kassemi L, El Ouezzani S, Magoul R, Merroun I, Lopez-Jurado M, Errami M. Effects of cannabinoids on neuropeptide y and endorphin expression in the rat hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Br J Nutr 2011;105:654–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gamber KM, Macarthur H, Westfall TC. Cannabinoids augment the release of neuropeptide Y in the rat hypothalamus. Neuropharmacology 2005;49:646–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bybee KA, Prasad A. Stress-related cardiomyopathy syndromes. Circulation 2008;118: 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woronow D, Suggs C, Levin RL, Diak IL, Kortepeter C. Takotsubo common pathways and SNRI medications. J Am Coll Cardiol HF 2018;6: 347–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurisu S, Kihara Y. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy: clinical presentation and underlying mechanism. J Cardiol 2012;60:429–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haghi D, Fluechter S, Suselbeck T, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (acute left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome) occurring in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 2006;32: 1069–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharkey SW, Maron BJ. Epidemiology and clinical profile of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2014;78:2119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol 2008; 124:283–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Del Buono MG, O’Quinn MP, Garcia P, et al. Cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation in a 23-year-old woman with broken heart syndrome. Cardiovasc Pathol 2017;30:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghadri JR, Cammann VL, Jurisic S, et al. A novel clinical score (InterTAK Diagnostic Score) to differentiate takotsubo syndrome from acute coronary syndrome: results from the International Takotsubo Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19: 1036–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, et al. Time course of electrocardiographic changes in patients with tako-tsubo syndrome: comparison with acute myocardial infarction with minimal enzymatic release. Circ J 2004;68:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Menon M, Parpart M, Maron MS, Maron BJ. Spectrum and significance of electrocardiographic patterns, troponin levels, and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction frame count in patients with stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy and comparison to those in patients with ST-elevation anterior wall myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:1723–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kosuge M, Kimura K. Electrocardiographic findings of takotsubo cardiomyopathy as compared with those of anterior acute myocardial infarction. J Electrocardiol 2014;47:684–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frangieh AH, Obeid S, Ghadri JR, et al. , for the InterTAK Collaborators. ECG criteria to differentiate between Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy and myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5:e003418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogura R, Hiasa Y, Takahashi T, et al. Specific findings of the standard 12-lead ECG in patients with “Takotsubo” cardiomyopathy: comparison with the findings of acute anterior myocardial infarction. Circ J 2003;67:687–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nguyen TH, Neil CJ, Sverdlov AL, et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic protein levels in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108:1316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Randhawa MS, Dhillon AS, Taylor HC, Sun Z, Desai MY. Diagnostic utility of cardiac biomarkers in discriminating takotsubo cardiomyopathy from acute myocardial infarction. J Card Fail 2014;20:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, et al. Prevalence of incidental coronary artery disease in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Coron Artery Dis 2009;20:214–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hussain MA, Cox AT, Bastiaenen R, Prasad A. Apical ballooning (takotsubo) syndrome with concurrent ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017 bcr-2017–220145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abreu G, Rocha S, Bettencourt N, et al. An unusual trigger causing Takotsubo syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2016;223:118–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eitel I, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F. Clinical characteristics and cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in stress. JAMA 2011;306:277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abbas A, Sonnex E, Pereira RS, Coulden RA. Cardiac magnetic resonance assessment of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Clin Radiol 2016;71:e110–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eitel I, Behrendt F, Schindler K, et al. Differential diagnosis of suspected apical ballooning syndrome using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2651–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haghi D, Fluechter S, Suselbeck T, Kaden JJ, Borggrefe M, Papavassiliu T. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in typical versus atypical forms of the acute apical ballooning syndrome (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy). Int J Cardiol 2007; 120:205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakamori S, Matsuoka K, Onishi K, et al. Prevalence and signal characteristics of late gadolinium enhancement on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2012;76:914–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Naruse Y, Sato A, Kasahara K, et al. The clinical impact of late gadolinium enhancement in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: serial analysis of cardiovascular magnetic resonance images. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2011;13:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Srichai MB, Junor C, Rodriguez LL, et al. Clinical, imaging, and pathological characteristics of left ventricular thrombus: a comparison of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, transthoracic echocardiography, and transesophageal echocardiography with surgical or pathological validation. Am Heart J 2006;152:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bossone E, Lyon A, Citro R, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: an integrated multi-imaging approach. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014; 15:366–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Citro R, Lyon AR, Meimoun P, et al. Standard and advanced echocardiography in takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy: Clinical and prognostic implications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:57–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Niccoli G, Scalone G, Crea F. Acute myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary atherosclerosis: mechanisms and management. Eur Heart J 2015;36:475–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Angelini P. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: establishing diagnosis and causes through prospective testing. Texas Hear Inst J 2016;43:2008–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marcovitz PA, Czako P, Rosenblatt S, Billecke SS. Pheochromocytoma presenting with Takotsubo syndrome. J Interv Cardiol 2010;23:437–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Agarwal V, Kant G, Hans N, Messerli FH. Takotsubo-like cardiomyopathy in pheochromocytoma. Int J Cardiol 2011;153:241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ferreira VM, Marcelino M, Piechnik SK, et al. Pheochromocytoma is characterized by catecholamine-mediated myocarditis, focal and diffuse myocardial fibrosis, and myocardial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2364–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Citro R, Rigo F, D’Andrea A, et al. Echocardiographic correlates of acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, and in-hospital mortality in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2014;7:119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Singh K, Carson K, Shah R, et al. Meta-analysis of clinical correlates of acute mortality in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1420–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Parodi G, Del Pace S, Salvadori C, Carrabba N, Olivotto I, Gensini GF. Left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome as a novel cause of acute mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:647–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haghi D, Papavassiliu T, Heggemann F, Kaden JJ, Borggrefe M, Suselbeck T. Incidence and clinical significance of left ventricular thrombus in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy assessed with echocardiography. Qjm 2008;101:381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schneider B, Athanasiadis A, Schwab J, et al. Complications in the clinical course of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2014;176:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pant S, Deshmukh A, Mehta K, et al. Burden of arrhythmias in patients with Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy (Apical Ballooning Syndrome). Int J Cardiol 2013;170:64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stiermaier T, Santoro F, Eitel C, et al. Prevalence and prognostic relevance of atrial fibrillation in patients with Takotsubo syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2017;245:156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Madias C, Fitzgibbons TP, Alsheikh-Ali AA, et al. Acquired long QT syndrome from stress cardiomyopathy is associated with ventricular arrhythmias and torsades de pointes. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:555–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Heckle MR, Mccoy CW, Akinseye OA, Khouzam RN. Stress-induced thrombus: prevalence of thromboembolic events and the role of anticoagulation in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Santoro F, Stiermaier T, Tarantino N, et al. Left ventricular thrombi in takotsubo syndrome: incidence, predictors, and management: results from the GEIST (German Italian Stress Cardiomyopathy) Registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e006990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Singh V, Mayer T, Salanitri J, Salinger MH. Cardiac MRI documented left ventricular thrombus complicating acute takotsubo syndrome: an uncommon dilemma. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2007; 23:591–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kumar S, Kaushik S, Nautiyal A, et al. Cardiac rupture in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Clin Cardiol 2011;34:672–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lisi E, Guida V, Blengino S, Pedrazzi E, Ossoli D, Parati G. Intra-aortic balloon pump for treatment of refractory ventricular tachycardia in Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy: a case report. Int J Cardiol 2014;174:135–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rashed A, Won S, Saad M, Schreiber T. Use of the Impella 2.5 left ventricular assist device in a patient with cardiogenic shock secondary to takotsubo cardiomyopathy BMJ. Case Rep 2015; 2015:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yoshioka T, Hashimoto A, Tsuchihashi K, et al. Clinical implications of midventricular obstruction and intravenous propranolol use in transient left ventricular apical ballooning (Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy). Am Heart J 2008;155:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bonacchi M, Maiani M, Harmelin G, Sani G. Intractable cardiogenic shock in stress cardiomyopathy with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: is extra-corporeal life support the best treatment? Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dib C, Prasad A, Friedman PA, et al. Malignant arrhythmia in apical ballooning syndrome: risk factors and outcomes. Indian Pacing Electro-physiol J 2008;8:182–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cecchi E, Parodi G, Giglioli C, et al. Stress-induced hyperviscosity in the pathophysiology of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2013;111: 1523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Akashi YJ, Nef HM, Lyon AR. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of Takotsubo syndrome. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xu Z, Li Q, Liu R, Li Y. Very early recurrence of takotsubo syndrome. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2014;19:93–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cerrito M, Caragliano A, Zema D, Zito C, Oreto G. Very late recurrence of takotsubo syndrome. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2012;17: 58–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Singh K, Parsaik A, Singh B. Recurrent takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Hertz 2014;39:963–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Santoro F, Ieva R, Musaico F, et al. Lack of efficacy of drug therapy in preventing takotsubo cardiomyopathy recurrence: a meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol 2014;37:434–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shiomura R, Nakamura S, Takano H, et al. Impact of brain natriuretic peptide, calcium channel blockers, and body mass index on recovery time from left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:515–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]