Abstract

Background and Aims:

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is chronic and recurs if treatment is discontinued. We aimed to determine rates of recurrence, and whether initial treatment with oral viscous budesonide (OVB) resulted in less recurrence than fluticasone from a multi-dose inhaler (MDI).

Methods:

This was the observation phase of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial comparing OVB to MDI for initial EoE treatment. Subjects with histologic response (fewer than 15 eosinophils/high-power field) in the trial entered an observation phase in which treatment was discontinued and symptoms were monitored. Patients underwent endoscopy or biopsy when symptoms recurred or at 1 year. We analyzed time to symptom recurrence and assessed endoscopic severity and histologic relapse (15 or more eosinophils/high-power field) at follow-up endoscopy.

Results:

Thirty-three of the 58 subjects (57%) had symptom recurrence before 1 year. The overall median time to symptom recurrence was 244 days. There was no difference in the rate of symptom recurrence for subjects treated with OVB vs MDI (hazard ratio 1.04; 95% CI: 0.52-2.08). At symptom recurrence, 78% of patients had histologic relapse. The patients had significant increases in mean Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire score (3.8 vs 8.7; P<001), and the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (1.3 vs 4.6; P<.001) compared to end-of-treatment.

Conclusions:

EoE disease activity recurred rapidly after initial histologic response to topical steroids (either OVB or MDI). Because most subjects had recurrent endoscopic and histologic signs not reliably detected by symptoms, maintenance therapy should be recommended in EoE patients achieving histologic response to topical steroids. Clinicaltrials.gov no: NCT02019758

Keywords: symptoms, natural history, dilation, outcomes, maintenance therapy

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the esophagus.1 Natural history studies as well as the placebo arm of clinical trials clearly document that the disease persists without treatment.2 Data from several independent centers have also shown that in patients with prolonged disease duration prior to diagnosis, or those with persistent disease activity, fibrostenotic complications are common.3–7 This implies that in many patients, EoE can progress from an inflammatory to a fibrostenotic phenotype. Moreover, disease activity appears to recur with cessation of treatment. Despite this, maintenance therapy in EoE remains an area of debate, with variable indications and practice patterns, and few data to support practice.8 Who with EoE would benefit from chronic treatment is an important gap in knowledge.

Topical steroids are a first line pharmacologic treatment for EoE, and have traditionally been used after failure to respond to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).9 As there are no FDA-approved medications (and only one medication approved in Europe), asthma preparations such as fluticasone in a multi-dose inhaler or aqueous budesonide have been adapted to coat the esophagus. There have been multiple clinical trials assessing induction therapy, with treatment lengths from 2 to 12 weeks.10 However, the durability of treatment response in EoE is unknown if medications are not continued after induction. There are few data available regarding durability of response, but these suggest a relatively rapid recurrence of symptoms and histologic activity.11, 12 Providers need high quality data to accurately inform patients regarding the likelihood and timing of recurrent symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia after an initially successful treatment course. A better understanding of durability of response would also inform decisions regarding which patients with EoE might need long-term therapy.9

Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine rates of symptomatic and histologic recurrence, and whether initial treatment with oral viscous budesonide (OVB) results in less recurrence than fluticasone from a multi-dose inhaler (MDI). We hypothesized that subjects initially treated with budesonide would have significantly less symptomatic recurrence and histologic relapse at one year than subjects initially treated with fluticasone.

Methods

Overview of parent clinical trial

This study was the observation phase of a randomized clinical trial comparing OVB to MDI for initial treatment of EoE; the full details of the parent study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02019758) have been previously reported,13 and are summarized in the Supplemental Materials. The study was approved by the UNC IRB, and all authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Follow-up procedures and outcomes

For this observation phase, patients were eligible for entry if they had successfully completed the randomized phase of the study, completed the week 8 endoscopy, and had histologic response defined as a peak eosinophil count <15 eos/hpf on esophageal biopsy.14, 15 At the start of the observation phase, treatment with the study medications was discontinued and symptoms were systematically monitored. Subjects were contacted every 8 weeks to assess symptoms using a standardized protocol, and were also asked to report recurrent symptoms at any time they occurred. Either at the time of recurrent symptoms, or at 1 year after entry into the observational phase, subjects completed outcome assessments. These included validated patient-reported outcomes (PROs), as well as endoscopy and biopsy. Selected safety and adverse events, including candidal esophagitis and food impaction, were also monitored.

The primary outcome was time to patient-reported symptom recurrence. In order to quantify symptom severity at the time of recurrence or at the 1 year time point (if there were no recurrent symptoms), subjects completed the Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ)16, 17 and the EoE Symptom Activity Index (EEsAI)18 (see Supplemental Materials).

Histologic and endoscopic outcomes were also assessed. For histology, we determined the peak eosinophil count at the time of the endoscopy performed for symptom recurrence or at the 1 year follow-up. Esophageal biopsies were obtained (4 fragments from the distal esophagus and 4 fragments from the proximal esophagus) and were examined by the study pathologist (JTW) using our previously validated and reliable protocol19, 20 (see Supplemental Materials). Histologic relapse was defined as a peak eosinophil count ≥15 eos/hpf. To determine endoscopic severity, the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS) was used21 (see Supplemental Materials). Esophageal dilation was permitted as clinically indicated at the discretion of the endoscopist, and could be performed during the end of treatment endoscopy, the symptom recurrence (or 1 year follow-up) endoscopy, or at both procedures. In order to estimate stricture diameter prior to dilation, we used either the through-the-scope balloon or Savary dilator to measure the esophageal diameter. The initial diameter was defined as the size just prior to when an initial dilation effect (mucosal tear or rent) was noted. The final diameter was the final dilator size used.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the subjects entering the observation phase were summarized with descriptive statistics. To test whether initial treatment with OVB resulted in less symptomatic recurrence than fluticasone MDI, survival analysis was performed with the interval between treatment end and recurrent symptoms or study end as the time of interest. A Kaplan-Meier curve was constructed comparing the time until symptom recurrence in both study groups, and differences were assessed using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for potential confounders including age, gender, atopic status, symptom duration prior to EoE diagnosis, and esophageal dilation. To test whether OVB resulted in less histologic recurrence than fluticasone MDI, the proportion of subjects with ≥15 eos/hpf at follow-up endoscopy were compared using chi-square. The means of the peak eosinophil counts were compared with 2 sample t-tests. We also compared changes in outcomes between the end of treatment and symptom recurrence (or 1 year follow-up) time points. Time-dependent analyses were also stratified by dilation status (whether dilation was performed at the end-of-treatment endoscopy). Characteristics of those patients with and without symptom recurrence in the observation phase were also compared. Sample size considerations are outlined in the Supplemental Materials.

Results

Characteristics of patients entering the observation phase

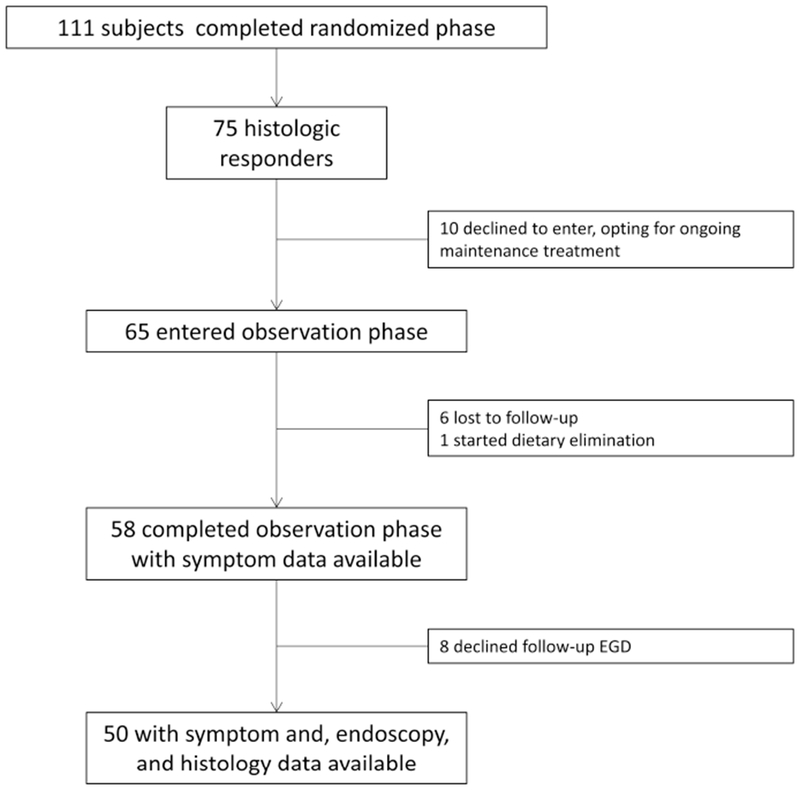

Of the 75 histologic responders in the randomized trial, 65 agreed to enter the observation phase, 6 were lost to follow-up and one started dietary therapy and was excluded, and 58 either provided symptom recurrence data or had no symptom recurrence at the 1 year follow-up (Figure 1). Of these 58, 50 agreed to undergo endoscopy and had symptom, endoscopy, and histologic data available. At baseline prior to treatment in the randomized phase, subjects ultimately entering the observation phase had a mean age of 42 years, 64% were male, 97% where white, 74% had at least one concomitant atopic condition, and all characteristics were similar when assessed by initial treatment allocation (budesonide vs fluticasone) (Table 1). Endoscopic features of EoE were common and approximately half of the patients required esophageal dilation. Over the course of the entire study, there were 12 subjects who had a dilation at each study endoscopy (baseline, post-treatment, symptom recurrence/end of observation phase), 9 who had two dilations, and 9 who had 1 dilation. There were no baseline differences between the 58 subjects who were analyzed in the observation phase and the other responders who either did not enter or who dropped out of the observation phase (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Patient flow through the study.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics at initial entry into the randomized phase of subjects ultimately entering the observation phase

| Initial allocation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=58) | Budesonide (n = 33) | Fluticasone (n =25) | |

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 41.7 ± 15.9 | 41.5 ± 16.1 | 41.9 ± 16.1 |

| Male (n, %) | 37(64) | 19 (58) | 18 (72) |

| White (n, %) | 56 (97) | 32 (97) | 24 (96) |

| Dysphagia symptoms (n, %) | 56 (97) | 31 (94) | 25 (100) |

| Length of dysphagia (mean years ± SD) | 10.6 ± 8.9 | 11.1 ± 9.5 | 10.0 ± 8.2 |

| DSQ score (mean ± SD) | 9.1 ± 9.3 | 10.4 ± 9.3 | 7.2 ± 9.1 |

| EEsAI score (mean ± SD) | 33.8 ± 19.4 | 36.1 ± 20.8 | 31.1 ± 17.6 |

| Any atopic condition ever (n, %) | 43 (74) | 23 (70) | 20 (80) |

| Asthma | 15 (26) | 9 (27) | 6 (24) |

| Eczema | 12 (21) | 8 (24) | 4 (16) |

| Seasonal allergies/allergic rhinitis | 33 (57) | 18 (55) | 15 (60) |

| Food allergies | 25 (43) | 14 (42) | 11 (44) |

| Endoscopic features | |||

| Total EREFS score (mean ± SD) | 4.5 ± 2.0 | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 4.3 ± 2.3 |

| EREFS components | |||

| Exudates (mean ± SD) | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.7 |

| Rings (mean ± SD) | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.9 |

| Edema (mean ± SD) | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.5 |

| Furrows (mean ± SD) | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.7 |

| Stricture (mean ± SD) | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 |

| Stricture size (mm ± SD) | 12.9 ± 3.2 | 12.9 ± 3.2 | 12.9 ± 3.3 |

| Narrowing (n, %) | 9 (16) | 4 (12) | 5 (20) |

| Dilation required at baseline exam (n, %) | 28 (48) | 15 (45) | 13 (52) |

| Dilator size achieved (mm ± SD) | 15.0 ± 2.6 | 15.0 ± 2.4 | 15.0 ± 2.8 |

| Peak overall eosinophil count (eos/hpf ± SD) | 73.0 ± 47.7 | 82.9 ± 50.3 | 60.0 ± 41.5 |

Time to symptom recurrence

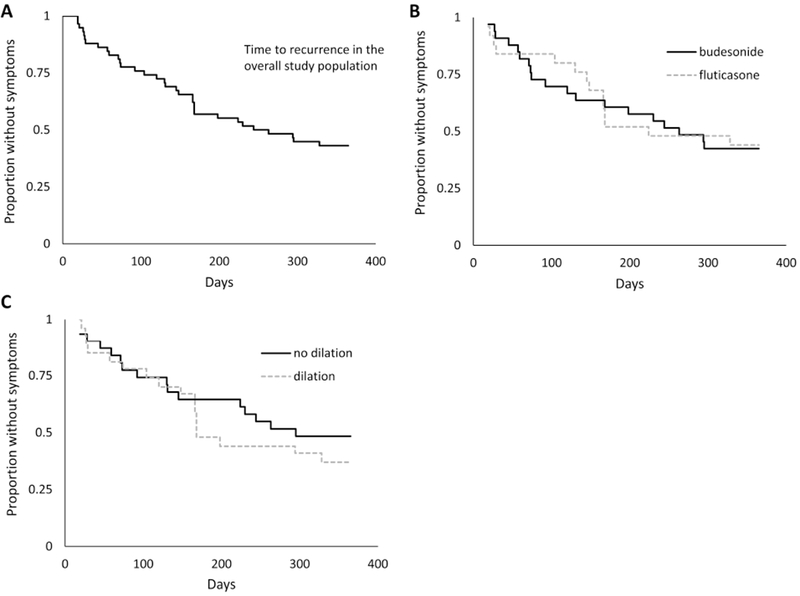

A total of 33 out of 58 subjects (57%) had symptom recurrence before one year; the median time to symptom recurrence was 244 days (Figure 2A). There was no difference in the rate of symptom recurrence for subjects in the budesonide vs fluticasone study groups (median time to recurrence 263 vs 224 days; p=0.91; Figure 2B). The corresponding unadjusted HR was 1.04 (95% CI: 0.52-2.08) and was unchanged after adjusting for the potential confounding factors above. There was also no difference in the rate of symptom recurrence by whether dilation was performed at the end of treatment/entry into observation (unadjusted HR 1.30, 95% CI: 0.66-2.58; Figure 3B). This lack of association with dilation persisted after adjustment for potential confounding factors above, as well as performing separate models taking into consideration whether baseline dilation was also performed, stricture size at baseline and follow-up, and size of dilation achieved (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to symptom recurrence in the overall population enrolled in the observation phase. (A) Time to symptom recurrence in the overall population. (B) Time to symptom recurrence, stratified by original allocation of budesonide or fluticasone in the parent clinical trial (p=0.91). (C) Time to symptom recurrence, stratified by whether dilation was performed at the end of treatment/observation phase enrollment endoscopy (p=0.44).

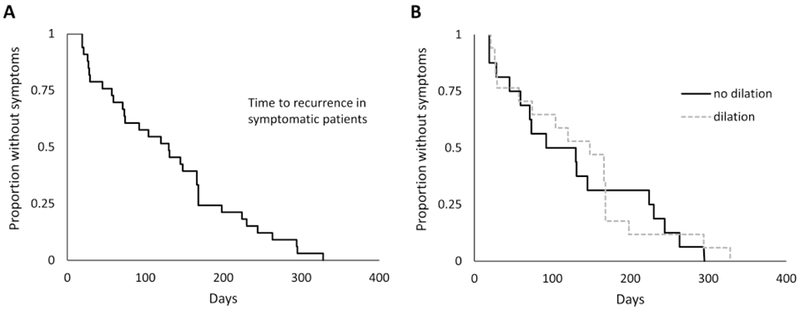

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for (A) time to symptom recurrence in those patients in the observation who developed symptoms and (B) as stratified by whether dilation was performed at the end of treatment/observation phase enrollment endoscopy (p=0.78).

In the 33 patients with recurrent symptoms, time to recurrence was even more rapid, with a median of 130 days (Figure 3A). While the median time to symptom recurrence was decreased in patients who did not receive a dilation compared to those who did, this was not statistically significant (92 vs 148 days; p=0.78; HR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.45-1.83; Figure 3B). This result was unchanged after accounting for potential confounders, dilation timing, stricture size, and dilation size achieved.

Outcome metrics at the time of symptom recurrence or 1 year follow-up

There were 50 subjects who underwent endoscopy and had complete outcome assessments measured at the time of symptom recurrence or 1 year follow-up. In this group, the DSQ score had more than doubled compared to the time at entry into the observation phase (3.8 ± 5.6 vs 8.7 ± 9.7; p<0.001; Table 2). The EEsAI score numerically increased with symptom recurrence, but this was not statistically significant. The total EREFS score also significantly increased between observation phase entry and time of symptom recurrence (1.3 ± 1.2 vs 4.6 ± 1.8; p<0.001). All of the individual EREFS components also increased, with the exception of strictures which were present in 50% of subjects at observation entry and 60% at symptom recurrence. Of note, in those patients with strictures, esophageal caliber had significantly decreased during the observation phase (14.8 ± 2.8mm vs 13.7 ± 3.5mm; p<0.001). Whereas a dilation size of 16.7 ± 1.7mm had been achieved at the time of histologic response and entry into observation, a size of only 15.4 + 2.3mm could be achieved at the time of symptom recurrence while off treatment (p=0.003). Overall, 78% of subjects had histologic relapse defined as ≥15 eos/hpf at the time of symptom recurrence or at the 1 year follow-up endoscopy, and 94% had some degree of eosinophilic infiltration on biopsy (≥1 eos/hpf); only 3 patients (6%) who were also asymptomatic had normal biopsies at the one year follow-up. There was poor agreement between symptom recurrence and histologic relapse (kappa = −0.07; p=0.74). During the observation phase, there were no food impactions, and no subjects had esophageal candidiasis on their final endoscopy. Interestingly, the group who reported no symptoms in the observation phase may not have been fully asymptomatic. While the DSQ score was significantly lower in the asymptomatic group compared to the symptom recurrence group (4.5 ± 8.1 vs 12.0 ± 9.8; p = 0.006), the EEsAI score was not significantly lower (27.4 ± 21.0 vs 34.3 ± 17.2; p = 0.31) and was not in the clinical remission range (<20) (Table 3).

Table 2:

Study outcomes at entry into the observation phase (completion of randomized phase) and at the time of symptom recurrence or 1 year follow-up

| Entry into the observation phase (completion of randomized phase) | Time of symptom recurrence or 1 year follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial allocation |

Initial allocation |

||||||

| Overall (n=50) | Budesonide (n = 25) | Fluticasone (n =25) | Overall (n=50) | Budesonide (n = 25) | Fluticasone (n =25) | p* | |

| Symptoms | |||||||

| DSQ score (mean ± SD)† | 3.8 ± 5.6 | 3.8 ± 5.2 | 3.8 ± 6.5 | 8.7 ± 9.7 | 9.4 ± 9.4 | 7.5 ± 10.5 | < 0.001 |

| EEsAI score (mean ± SD)‡ | 25.3 ± 17.5 | 24.4 ± 17.9 | 26.6 ± 17.4 | 31.2 ± 19.0 | 37.7 ± 18.8 | 25.7 ± 17.8 | 0.22 |

| Endoscopy | |||||||

| Total EREFS score (mean ± SD) | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 4.8 ± 1.7 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | < 0.001 |

| EREFS components | |||||||

| Exudates (mean ± SD) | 0.02 ± 0.1 | 0.03 ± 0.2 | 0 ± 0 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| Rings (mean ± SD) | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| Edema (mean ± SD) | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Furrows (mean ± SD) | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| Stricture (mean ± SD) | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.26 |

| Stricture size (mm ± SD) | 14.8 ± 2.8 | 14.4 ± 2.2 | 15.1 ± 3.3 | 13.7 ± 3.5 | 13.9 ± 3.2 | 13.5 ± 3.9 | < 0.001 |

| Narrowing (n, %) | 7 (14) | 3 (12) | 4 (16) | 10 (20) | 5 (20) | 5 (20) | 0.18 |

| Dilation required (n, %) | 25 (50) | 11 (44) | 14 (56) | 18 (36) | 8 (32) | 10 (40) | 0.05 |

| Dilator size (mm ± SD) | 16.7 ± 1.7 | 16.3 ± 1.5 | 17.0 ± 1.9 | 15.4 ± 2.3 | 14.7 ± 2.1 | 16.1 ± 2.4 | 0.003 |

| Histology | |||||||

| Peak overall eosinophil count (eos/hpf ± SD) | 1.7 ± 3.4 | 1.8 ± 3.8 | 1.6 ± 2.9 | 53.4 ± 46.2 | 71.8 ± 52.9 | 35.0 ± 29.4 | < 0.001 |

| ≥15 eos/hpf (n, %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 39 (78) | 22 (88) | 17 (68) | 0.004 |

| ≥5 eos/hpf (n, %) | 6 (12) | 2 (8) | 4 (16) | 46 (92) | 24 (96) | 22 (88) | < 0.001 |

| ≥1 eos/hpf (n, %) | 18 (36) | 10 (40) | 8 (32) | 47 (94) | 24 (96) | 23 (92) | < 0.001 |

For the comparison of overall outcomes at observation phase entry and time of symptom recurrence or 1 year follow-up (both treatment groups combined)

For DSQ, a total of 50 completed questionnaires were available at observation entry and 49 at symptom recurrence or 1 year follow-up

For EEsAI, a total of 43 completed questionnaires were available at observation entry and 33 at symptom recurrence or 1 year follow-up

Table 3:

Characteristics and outcomes of subjects with symptom recurrence compared to those who remained symptom free at the 1 year follow-up time point

| Baseline characteristics (at initial randomization) | Symptom recurrence (n = 33) | No symptom recurrence (n = 25) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD; range) | 43.3 ± 16.3 | 39.5 ± 15.4 | 0.38 |

| Male (n, %) | 22 (67) | 15 (60) | 0.60 |

| White (n, %) | 31 (94) | 25 (100) | 0.21 |

| Dysphagia symptoms (n, %) | 31 (94) | 25 (100) | 0.21 |

| Length of dysphagia (mean years ± SD) | 11.4 ± 9.6 | 9.6 ± 8.0 | 0.46 |

| DSQ score (mean ± SD; n=55) | 10.4 ± 10.1 | 7.2 ± 7.9 | 0.20 |

| EEsAI score (mean ± SD; n=44) | 36.0 ± 17.5 | 30.7 ± 21.8 | 0.38 |

| Any atopic condition ever (n, %) | 26 (79) | 17 (68) | 0.35 |

| Asthma | 11 (33) | 4 (16) | 0.14 |

| Eczema | 7 (21) | 5 (20) | 0.91 |

| Seasonal allergies/allergic rhinitis | 21 (64) | 12 (48) | 0.23 |

| Food allergies | 14 (42) | 11 (44) | 0.90 |

| Endoscopic features | |||

| Total EREFS score (mean ± SD) | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 4.5 ± 2.2 | 0.90 |

| EREFS components | |||

| Exudates (mean ± SD) | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 0.72 |

| Rings (mean ± SD) | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.30 |

| Edema (mean ± SD) | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.75 |

| Furrows (mean ± SD) | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.22 |

| Stricture (mean ± SD) | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.05 |

| Stricture size (mm ± SD) | 13.4 ± 3.4 | 11.7 ± 2.4 | 0.15 |

| Narrowing (n, %) | 5 (15) | 4 (16) | 0.93 |

| Dilation required at baseline exam (n, %) | 18 (55) | 10 (40) | 0.27 |

| Dilator size achieved (mm ± SD) | 15.2 ± 2.8 | 14.5 ± 2.1 | 0.48 |

| Peak overall eosinophil count (eos/hpf ± SD) | 77.6 ± 51.5 | 67.0 ± 42.4 | 0.41 |

| Outcome data at observation phase enrollment (end of randomized phase) | (n = 27) | (n = 33) | |

| Symptoms | |||

| DSQ score (mean ± SD; n=50) | 4.3 ± 6.4 | 2.9 ± 4.2 | 0.41 |

| EEsAI score (mean ± SD; n=43) | 23.5 ± 14.6 | 28.4 ± 21.8 | 0.38 |

| Endoscopy | |||

| Total EREFS score (mean ± SD) | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 0.64 |

| EREFS components | |||

| Exudates (mean ± SD) | 0 ± 0 | 0.04 ± 0.2 | 0.25 |

| Rings (mean ± SD) | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.81 |

| Edema (mean ± SD) | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.24 |

| Furrows (mean ± SD) | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.24 |

| Stricture (mean ± SD) | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.28 |

| Stricture size (mm ± SD) | 15.1 ± 2.9 | 14.1 ± 2.7 | 0.37 |

| Narrowing (n, %) | 7 (21) | 1 (4) | 0.06 |

| Dilation required at follow-up exam (n, %) | 17 (52) | 10 (40) | 0.38 |

| Dilator size achieved (mm ± SD) | 16.9 ± 1.7 | 16.4 ± 1.8 | 0.45 |

| Peak overall eosinophil count (eos/hpf ± SD) | 2.2 ± 4.2 | 1.0 ± 1.9 | 0.16 |

| Outcome data at symptom recurrence or end of observation phase EGD | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | |

| Symptoms | |||

| DSQ score (mean ± SD; n=49) | 12.0 ± 9.8 | 4.5 ± 8.1 | 0.006 |

| EEsAI score (mean ± SD; n=33) | 34.3 ± 17.2 | 27.4 ± 21.0 | 0.31 |

| Endoscopy | |||

| Total EREFS score (mean ± SD) | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 0.86 |

| EREFS components | |||

| Exudates (mean ± SD) | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.66 |

| Rings (mean ± SD) | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.11 |

| Edema (mean ± SD) | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.92 |

| Furrows (mean ± SD) | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.38 |

| Stricture (mean ± SD) | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.19 |

| Stricture size (mm ± SD) | 14.3 ± 3.4 | 12.7 ± 3.6 | 0.25 |

| Narrowing (n, %) | 6 (22) | 4 (17) | 0.67 |

| Dilation required at final exam (n, %)* | 12 (44) | 6 (26) | 0.18 |

| Dilator size achieved (mm ± SD) | 16.1 ± 2.3 | 13.9 ± 1.7 | 0.08 |

| Peak overall eosinophil count (eos/hpf ± SD) | 54.1 ± 40.1 | 52.6 ± 53.5 | 0.91 |

| Eosinophil count ≥15 eos/hpf (n, %) | 22 (81) | 17 (74) | 0.52 |

| Eosinophil count ≥5 eos/hpf (n, %) | 25 (93) | 21 (91) | 0.87 |

| Eosinophil count ≥1 eos/hpf (n, %) | 26 (96) | 21 (91) | 0.46 |

There were few clinical, endoscopic, or histologic features, whether assessed at baseline, entry into observation phase, or time of symptom recurrence, that distinguished the subjects with symptom recurrence compared to those without symptom recurrence in the observation phase (Table 3). Strictures were more common at baseline in those patients who ultimately had symptom recurrence (EREFS stricture score of 0.7 vs 0.4; p=0.05), but stricture size was not smaller in this group at any of the study time points. Recurrent strictures were also not associated with higher eosinophil counts. Specifically, for those patients who did have symptom recurrence, the peak eosinophil count was 49.3 ± 37.1 in those who required dilation and 57.9 ± in those who did not require dilation (p = 0.59). Similarly, in those without symptom recurrence, the peak eosinophil count was 60.8 ± 39.7 in those who required dilation and 49.6 ± in those who did not (p = 0.67). There were also no differences when analyzed by histologic response using the 15 eos/hpf threshold.

Discussion

It is well documented that initial treatment of EoE leads to symptomatic, endoscopic, and histologic improvements. However, for a chronic disease, the role of maintenance therapy for EoE is unclear, and time to recurrence of disease activity has not been extensively studied.8 In this study, newly diagnosed EoE cases who participated in a randomized, double-blind, double dummy clinical trial of budesonide vs fluticasone and who had a histologic response were eligible to enter an observation phase.13 During this follow-up, which could last up to a year, subjects were monitored for symptom recurrence while off treatment. When symptoms did recur, or at the 1 year time point, they underwent endoscopy, biopsy, and outcome assessment.

There are several notable findings. First, symptom recurrence was generally rapid, especially in a population where approximately half required at least one esophageal dilation. Second, the initial topical steroid used for treatment did not impact the time to symptom recurrence, in contrast to our initial hypothesis. Third, and perhaps most importantly, histologic and endoscopic recurrence, while not universal, were seen in the vast majority of subjects regardless of whether they had symptom recurrence or not, and there was poor agreement between symptoms and histologic relapse. At the same time, previously dilated esophageal strictures had re-narrowed nearly back to their baseline (pre-dilation) diameter. These findings have clear clinical implications. Symptoms do not appear to be a reliable indicator of long-term disease control after initial remission in the setting of medication discontinuation, and even patients who were “asymptomatic” still had measurable symptom scores using validated instruments. Given the rapidity of symptom recurrence and associated histologic and endoscopic activity, maintenance therapy for EoE seems to be well-justified. Moreover, there were no clinical, endoscopic, or histologic predictors of rapid symptom recurrence.

Our results are consistent with, but extend, what is already known from the previous few studies that have investigated this issue. In a retrospective trial of adults treated with an initial two-week course of fluticasone MDI, 29 of 32 patients reported recurrent dysphagia at a mean of 9 months.11 In a prospective trial, subjects who previously responded to a two-week course of nebulized then swallowed budesonide were randomized to low dose budesonide or to placebo.12 After 50 weeks of treatment, all 14 patients in the placebo arm had recurrent esophageal eosinophilia, and the median time to symptom relapse was 95 days. However, in this study the initial treatment course (2 weeks) was shorter than that currently utilized in practice, so the recurrence rates might have been higher. Most recently, abstract data have been presented for a randomized-withdrawal study in patients who had clinico-histologic remission after a 12-week course of an orodispersible budesonide table at a dose of 1 mg BID.22 The 204 subjects were randomized to either 1mg BID, 0.5 mg BID, or placebo. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as symptom relapse, histologic relapse, esophageal dilation, or study withdrawal. After 48 weeks of treatment, 75%, 74%, and 4% of the subjects were free of treatment failure in the 1mg BID, 0.5 mg BID, and placebo groups, respectively, and 90% of the placebo group had a histologic relapse (≥48 eos/mm2). Overall, these data on symptom and histologic recurrence rates are similar in scale to what we report, though in the clinical trial setting patients were not allowed to be dilated at either initial entry (baseline pre-treatment) or at the post-treatment follow-up procedure (observation or randomized-withdrawal entry), so symptom recurrence could be more rapid and results are less applicable to a real-world setting where dilation is performed.

There are very few studies that have prospectively followed EoE patients off treatment. In one study, Straumann and colleagues followed 30 adults with EoE for an average of 7.2 years with no anti-inflammatory treatment, though esophageal dilation was allowed, and symptoms of dysphagia and eosinophilic infiltration persisted.23 In another, Schoepfer and colleagues followed a cohort of patients after esophageal dilation alone and found that while symptoms improved (and could remain quiescent for more than a year) esophageal eosinophilia persisted.24 In a third, Greuter and colleagues assessed a subset of 33 patients who were able to achieve “deep remission” on topical steroids, with lack of clinical symptoms, absence of any endoscopic signs of EoE, and <5 eos/hpf on biopsy.25 When these patients stopped their treatment, nearly 80% had a symptom recurrence within a median time of approximately 22 weeks (just over 150 days). Coupled to these data are studies showing that lack of histologic control in EoE can lead to food impactions,26 more esophageal dilations,27 and that symptoms only mildly correlate with the endoscopic and histologic signs.28 Our study corroborates the recurrence of eosinophilic infiltration and endoscopic signs of esophageal fibrostenosis when patients are followed off treatment for up to one year, and suggests that symptoms are not a reliable metric with which to assess mucosal inflammation while off treatment.

There are some limitations to this study. First, it was conducted at a single referral center. Second, the sample size is somewhat small as not all responders to the initial topical steroid treatment in the clinical trial entered the observation phase. However, these patients were similar in demographic and clinical characteristics to those patients who did not enter observation or who dropped out, making selection bias less likely (for example, more severe patients did not preferentially not participate). Third, we allowed dilation as clinically indicated in both the randomized and observation phases. Dilation is a complicating factor when examining and interpreting clinical symptoms, but it also allows our data to be extended into “real-world” settings where dilation is performed clinically, not prohibited by a trial protocol. In addition, our analyses stratified by dilation status were someone contradictory. While the hypothesis would be that dilation would lead to less symptom recurrence, we did not clearly observe this in all cases, and sensitivity analyses by stricture size, dilation size achieved, or timing of dilation did not yield an explanation. Finally, we did not have complete data for the patient reported outcome measures for all subjects.

There are also multiple strengths of this study. The observation phase was an extension of a rigorously designed randomized controlled trial, with strict protocols, data collection tools and methods, as well as a pre-specified follow-up period. We utilized the validated symptom and endoscopic outcome measures that were available at the time of the study design. Analyses were performed on a time-to-event basis for symptom recurrence, and at the time of recurrence (or 1 year follow-up) for the endoscopic and histologic outcomes. In this way, we can link the symptom, endoscopic, and histologic measures.

In conclusion, in this observation phase extension of a randomized, double-blind, double dummy clinical trial, patients who initially achieved histologic response to treatment with a topical steroid (either budesonide or fluticasone) were followed for up to 1 year off treatment. We found that symptoms recurred in the majority of patients, despite a high proportion previously requiring esophageal dilation, and that at the time of symptom recurrence or the one year follow-up time point, histologic and endoscopic recurrence was near-universal. Because the parent trial enrolled incident (newly diagnosed) EoE cases, our results are widely applicable. An initial 8-week induction course of topical steroids does not provide long-term disease control. Off treatment for up to a year, we observed recurrent esophageal eosinophilia, progression of stricture severity and loss of esophageal caliber gained from prior dilations, and recurrent symptoms. These data justify the use of maintenance therapy in patients with EoE who achieve disease remission on topical/swallowed steroids. The optimal long-term dose of topical steroids, potential for adverse events, and need for safety data remain areas that require future study.

Supplementary Material

Need to know:

Background:

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) recurs if treatment is discontinued. We investigated rates of and times to recurrence in patients with EoE treated with oral viscous budesonide (OVB) vs fluticasone from a multi-dose inhaler (MDI).

Findings:

EoE disease activity recurs in most patients, within a median 244 days, after initial histologic response to OVB or MDI.

Implications for patient care:

Most patients with EoE have recurrent endoscopic and histologic features that are not reliably detected by symptoms, so maintenance therapy should be recommended for patients with a histologic response to topical steroids.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported by NIH R01 DK101856, and used resources from UNC Center for GI Biology and Disease (NIH P30 DK034987) and the UNC Translational Pathology Lab, which is supported in part by grants from the NCI (2-P30-CA016086-40), NIEHS (2-P30ES010126-15A1), UCRF, and NCBT (2015-IDG-1007).

Disclosures: Dr. Dellon has received research funding from Adare, Allakos, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire; has received consulting fees from Adare, Alivio, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Banner, Biorasi, Calypso, Enumeral, EsoCap, Celgene/Receptos, Gossamer Bio, GSK, Regeneron, Robarts, Salix, and Shire, and educational grants from Allakos, Banner, and Holoclara. Dr. Dellon has no personal potential conflicts to declare. None of the other co-authors report any relevant disclosures or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022–33.e10. Epub 2018/07/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319–22.e3. Epub 2017/08/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6): 1230–6 e2 Epub 2013/08/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, et al. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;79:577–85.e4. Epub 2013/11/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipka S, Kumar A, Richter JE. Impact of Diagnostic Delay and Other Risk Factors on Eosinophilic Esophagitis Phenotype and Esophageal Diameter. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50:134–40. Epub 2015/02/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warners MJ, Oude Nijhuis RAB, de Wijkerslooth LRH, et al. The natural course of eosinophilic esophagitis and long-term consequences of undiagnosed disease in a large cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113(6):836–44. Epub 2018/04/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koutlas NT, Dellon ES. Progression from an inflammatory to a fibrostenotic phenotype in eosinophilic esophagitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2017;11:382–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philpott H, Dellon ES. The role of maintenance therapy in eosinophilic esophagitis: who, why, and how? J Gastroenterol 2018;53:165–71. Epub 2017/10/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Evidence based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108(5):679–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotton CC, Eluri S, Wolf WA, et al. Six-Food Elimination Diet and Topical Steroids are Effective for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Meta-Regression. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:2408–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helou EF, Simonson J, Arora AS. 3-Yr-Follow-Up of Topical Corticosteroid Treatment for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103(9):2194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9(5):400–9 e1 Epub 2011/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dellon ES, Woosley JT, Arrington A, et al. Efficacy of Budesonide vs Fluticasone for Initial Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:65–73.e5. Epub 2019/03/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf WA, Cotton CC, Green DJ, et al. Evaluation of histologic cutpoints for treatment response in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Research. 2015;4:1780–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed CC, Wolf WA, Cotton CC, et al. Optimal Histologic Cutpoints for Treatment Response in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Analysis of Data From a Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:226–33.e2. Epub 2017/10/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellon ES, Irani AM, Hill MR, et al. Development and field testing of a novel patient-reported outcome measure of dysphagia in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:634–42. Epub 2013/07/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Symptomatic, Endoscopic, and Histologic Parameters Compared with Placebo in Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:776–86.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoepfer AM, Straumann A, Panczak R, et al. Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1255–66 e21 Epub 2014/08/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellon ES, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, et al. Inter- and intraobserver reliability and validation of a new method for determination of eosinophil counts in patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55(7):1940–9. Epub 2009/10/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rusin S, Covey S, Perjar I, et al. Determination of esophageal eosinophil counts and other histologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis by pathology trainees is highly accurate. Hum Pathol 2017;62:50–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62:489–95. Epub 2012/05/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, Vieth M, et al. Budesonide orodispersible tables are highly effective to maintain clinico-histologic remission in adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: Results from the 48-weeks, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pivotal EOS-2 trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;156 (Suppl 1):S-1509 (Ab 951a). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, et al. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(6):1660–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoepfer AM, Gonsalves N, Bussmann C, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: effectiveness, safety, and impact on the underlying inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105(5):1062–70. Epub 2009/11/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greuter T, Bussmann C, Safroneeva E, et al. Long-Term Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis With Swallowed Topical Corticosteroids: Development and Evaluation of a Therapeutic Concept. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1527–35. Epub 2017/07/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuchen T, Straumann A, Safroneeva E, et al. Swallowed topical corticosteroids reduce the risk for long-lasting bolus impactions in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2014;69:1248–54. Epub 2014/06/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Runge TM, Eluri S, Woosley JT, et al. Control of inflammation decreases the need for subsequent esophageal dilation in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esoph 2017;30:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Coslovsky M, et al. Symptoms Have Modest Accuracy in Detecting Endoscopic and Histologic Remission in Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(3):581–90 e4 Epub 2015/11/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.