Abstract

Background:

The prevalence of mycosis fungoides / Sézary syndrome (MF/SS) is higher in the African American (AA)/black population compared to Caucasians in the United States and worse outcomes have been observed in AA/black patients.

Objectives:

To describe the outcomes and to identify prognostic factors in AA/black patients with MF/SS.

Methods:

Clinical features and follow-up data were analyzed in 157 self-identified AA/black patients seen between 1994–2018.

Results:

We included 122 patients with early-stage MF and 35 patients with advanced-stage disease (median follow-up of 25 months). >80% of the patients who died from disease or progressed presented with erythema/hyperpigmentation without hypopigmentation. Patients presenting with hypopigmentation, either as the sole manifestation or in combination with other lesions, had better overall survival (P=.002) and progression free survival (P=.014). Clinical stage, TNMB classification, plaque disease and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase were also significantly associated with outcomes. Demographic and socioeconomic parameters were not associated with prognosis.

Limitations:

A retrospective study at a single cancer center.

Conclusions:

MF/SS manifestations and outcomes in AA/black patients are heterogenous. Demographic and socioeconomic factors do not seem to have a prognostic role, while clinical characteristics may help to stratify for risk of progression and shorter survival, allowing for individually-tailored therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: cutaneous lymphoma, MF, racial disparity, skin of color, African American, survival analysis, hypopigmented MF, hyperpigmented MF

CAPSULE SUMMARY

• Aggressive behavior of mycosis fungoides / Sézary syndrome (MF/SS) in African American (AA) / black patients has been reported.

• MF/SS outcomes are heterogenous in AA/black patients. Inferior outcomes are associated with clinical characteristics and not with demographic/socioeconomic parameters. AA/black patients with MF/SS shouldn’t be treated more aggressively as a group.

Introduction

Racial disparities in cancer survival in the United States (US) are well documented; however, the underlying causes are not well understood.1,2 The incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and mycosis fungoides / Sézary syndrome (MF/SS) is higher in the US in African American (AA)/blacks than whites.3–5 The prognosis of MF/SS has also been shown to be significantly associated with race in several retrospective cohorts and population-based registries, showing poorer survival in AA/black patients.6–11 AA/black patients frequently have an earlier onset of MF/SS7,11–14 and may present with more advanced disease stages than white patients.12,13 Demographic factors along with differences in socioeconomic status, clinicopathologic characteristics, disease biology and treatments have been proposed to play a role in these MF/SS disparities.

The goal in this study was to identify the clinical factors associated with outcomes in AA/black patients with MF/SS who present to a referral cancer center. Understanding the prognostic factors in this specific population can ensure the most appropriate individually tailored treatment plan and may help to close the racial survival gap in MF/SS.

Methods

Patients selection and data collection

Following approval by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), self-identified black/AA patients diagnosed with MF/SS between the years 1992 and 2017 were identified through a search of our institutional database. We identified the patients based on the race/ethnicity data as self-reported upon admission/registration to MSKCC in accordance with the US Census Bureau’s race and ethnicity categories. Medical records were reviewed and patients were included in the study if a diagnosis of MF/SS had been confirmed clinically and histopathologically by a dermatologist and a dermatopathologist at MSKCC.15–17 Patients who were found to be positive for human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) I or II were excluded from analysis, as HTLV-associated adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia can be misdiagnosed as MF and represents a distinct disease process. For all cases meeting inclusion requirements, an extensive chart review was performed, and the following data was collected from the time of initial presentation at MSKCC for MF/SS: age at diagnosis of MF/SS, sex, race, ethnicity, country of birth, lesion morphology, clinical variant of MF and clinical and TNMB classification stage. The following laboratory values at presentation were recorded: serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), white blood cell count (WBC), absolute lymphocyte count, and absolute eosinophil count (EOS). Initial pathology reports were reviewed for presence of folliculotropism and large cell transformation (LCT) as well as for CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell phenotype immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining status on skin biopsy

Socioeconomic status

Using each patient’s residential ZIP code at the time of initial presentation, we recorded median household income and percent of individuals living below the poverty line. Median household income was categorized as quartiles: ≤$37,999, $38,000-$47,999, $48,000-$63,999, or ≥$64,000; poverty level was categorized as ≤20% or >20%. We utilized the US Census Bureau’s 2012–2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates to assess socioeconomic status, as previously described.18,19 Healthcare coverage information was extracted from electronic medical records.

Statistical analysis

The date of the first diagnostic biopsy was considered as the date of MF/SS diagnosis. Duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of initial consultation due to MF/SS at MSKCC to the date of most recent visit or date of death. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of initial presentation at MSKCC with MF/SS to death from any cause, or date of last follow-up. Disease-specific survival (DSS) was calculated from the date of initial presentation to death from MF/SS, death from another cause or date of last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from initial presentation at MSKCC to date of a documented progression to a more advanced clinical stage or death from MF/SS. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the patient characteristics and clinical characteristics of their disease. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were used to assess associations between demographic and clinical characteristics with early versus late stage disease at presentation. Univariate and multivariate analyses of survival and disease progression risk were performed using Kaplan Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards models. Log-rank tests were used to assess equality of Kaplan Meier survival estimates. All tests were two-sided, and P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software (IBM) and Stata v.14.1 (Stata Corporation).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Of the 157 patients, a majority were female (n=97, 60.6%), 142 (90%) were non-Hispanic, 8 (5%) were Hispanic and in 7 (5%) ethnicity was unknown (Table I). Thirty-one patients (20%) were born outside of the US. The median (range) age at diagnosis was 49 (12–88) years, with no significant age difference between males and females. Eight patients (5%) were 18 years or younger at presentation. Median delay from onset of skin symptoms to diagnosis was 4 years. Median referral delay from diagnosis to presentation at our institution was 2.2 months and 70% of the patients presented within 6 months of their diagnosis. At presentation, 122 patients (78%) had early-stage MF (clinical stages IA-IIA), mostly (51%) stage IB, while 35 (22%) had advanced-stage (IIB-IV).

Table I.

Clinical Characteristics of 157 Black Patients with Mycosis Fungoides / Sézary Syndrome

| Patient Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, mean (range), y | 47.9 (12–88) |

| Female-male ratio (No.:No.) | 1.6 (97:60) |

| Diagnosis delay from onset of symptoms, mean (range), m | 4.0 (0.1–30) |

| Referral delay from diagnosis, mean (range), y | 2.2 (0–156.3) |

| Birth place, No. (%) | |

| US | 68 (43) |

| Non-US | 31 (20) |

| Unknown | 58 (37) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 142 (90) |

| Hispanic | 8 (5) |

| Unknown | 7 (5) |

| Healthcare coverage, No. (%) | |

| Medicaid | 21 (13) |

| Medicare | 24 (15) |

| Private/HMO | 105 (67) |

| Unknown | 7 (5) |

| Median Household Income, No. (%) | |

| $1–37,999 | 33 (21) |

| $38,000–47,999 | 29 (18) |

| $48,000–63,999 | 26 (17) |

| $64,000 or more | 60 (38) |

| Unknown | 9 (6) |

| Poverty rate (per ZIP code), No. (%) | |

| ≤20% | 93 (59) |

| >20% | 55 (35) |

| Unknown | 9 (6) |

| Most severe type of skin lesions, No. (%) | |

| Patches | 84 (53) |

| Plaques | 48 (31) |

| Tumors and nodules | 15 (10) |

| Erythroderma | 9 (6) |

| Unknown | 1 (0) |

| Color of lesions, No. (%) | |

| Erythematous | 44 (28) |

| Hypopigmented | 71 (45) |

| Hyperpigmented | 83 (53) |

| Unknown | 5 (3) |

| Follicular involvement, No. (%) | 17 (11) |

| Ulceration, No. (%) | 2 (1) |

| Clinical Stage, No. (%) | |

| IA | 31 (20) |

| IB | 80 (51) |

| IIA | 11 (7) |

| IIB | 14 (9) |

| IIIA + IIIB | 4 (2) |

| IVA + IVB | 17 (11) |

| Immunophenotype per IHC on initial skin biopsy, No. (%) | |

| CD4+ | 64 (41) |

| CD8+ | 30 (19) |

| Unknown | 63 (40) |

| Large cell transformation, No. (%) | 23 (15) |

| Initial treatment, No. (%) | |

| Topical steroids alone | 21 (13) |

| Topical nitrogen mustard alone | 3 (2) |

| Phototherapy NBUVB / PUVA | 68* (43) / 10** (6) |

| Radiation Local / TSEB | 2 (1) / 11 (7) |

| Oral bexarotene | 11 (7) |

| Oral methotrexate | 2 (1) |

| Romidepsin | 6 (4) |

| Brentuximab | 2 (1) |

| Chemotherapy | 8 (5) |

| Observation | 1 (<1) |

| Lost to follow-up | 8 (5) |

| Unavailable | 4 (3) |

Abbreviations: US, United States; HMO, health maintenance organization; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NBUVB, Narrowband ultraviolet B; TSEB, total skin electron beam

+Median household income national quartile for patient residential ZIP code

++Individuals below poverty line in patient residential ZIP code

combined with oral bexarotene in 5 cases.

combined with interferon in one case and with interferon and oral bexarotene in one case.

Patients with early-stage MF were more likely to present with hypopigmented lesions than patients with advanced-stage disease (odds ratio (OR) = 12.64, 95% CI 3.65–43.78, P<.001), were less likely to present with CD4+ versus CD8+ immunophenotype per tissue IHC (OR = 0.06, 95% CI 0.01–0.48, P=.008) and were less likely to present with elevated eosinophil count (EOS), WBC or LDH (OR=0.07, 95% CI 0.01–0.38, P=.002, OR=0.05, 95% CI 0.01–0.26, P<.001 and OR=0.08, 95% CI 0.03–0.23, P<.001, respectively). Early versus advanced-disease cases did not differ by age at diagnosis, sex, ethnicity, birthplace, health insurance, income or poverty rate as per residential ZIP code.

Survival and Prognostic Factors

Eight patients (5%) were lost to follow-up after a single consult (one patient with advanced-stage and seven with early-stage disease). For the other 149 patients, median (range) follow-up was 25 (0.5–306) months. Of the 115 patients who presented with early-stage disease, twelve (10%) progressed to advanced-stages and six (5%) died of CTCL after a median (range) follow-up of 74 (9–98) months. Among the 34 patients with advanced-stage at presentation, 5 patients (15%) progressed to a higher clinical stage and 12 (35%) died of lymphoma. There were 34 deaths observed over the course of follow-up and 18 were disease-related. Overall death and disease-specific death were not associated with sex, birthplace, ethnicity, diagnosis delay, referral delay, health care coverage, income or poverty rate. Age at diagnosis and at presentation were not associated with disease-specific death.

Survival analysis was performed using univariable Cox proportional hazards regression (Table II). Older age at diagnosis was associated with shorter OS but not with DSS. No association was found between survival and sex or other demographic/socioeconomic factors. Overall clinical staging and TNMB classifications were associated with survival. Hypopigmented lesions were seen in 45% of the patients and the presence of hypopigmented lesions, whether as the only presentation or concurrently with hyperpigmentation/erythema, was associated with longer OS (HR, 0.04; 95% CI, 0.006–0.32; P=.002). No disease-specific deaths were recorded among patients with hypopigmented lesions. Among the 94 cases for which we had IHC results on initial diagnostic biopsy, no deaths (0/29) were recorded in patients with CD8+ disease while 30% (19/63) of the patients with CD4+ disease died (P<.001); 11 of them died due to lymphoma. Blood analysis at presentation showed that elevated WBC and LDH were significantly associated with shorter survival and elevated EOS was associated with shorter DSS. In a multivariate analysis, diagnosis delay from onset of symptoms was independently associated with longer OS (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79–0.95; P=.002) and DSS (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77–0.96; P=.008); advanced clinical stages were associated with shorter survival while sex, age, healthcare coverage and income were not.

Table II.

Univariate Survival Analysis in 149 Black Patients with Mycosis Fungoides / Sézary syndrome

| Clinical Characteristic | N | Overall Survival (OS) from presentation | Disease Specific Survival (DSS) from presentation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age at diagnosis (per year) | 149 | 1.024 (1.002–1.046) | .033 | 1.003 (0.975–1.032) | 0.846 |

| Sex | 149 | ||||

| Female | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Male | 0.614 (0.311–1.215) | .161 | 0.864 (0.333–2.245) | 0.764 | |

| Diagnosis Delay (per year) | 133 | 0.978 (0.922–1.037) | .448 | 0.991 (0.919–1.067) | 0.803 |

| Referral Delay (per month) | 144 | 1.0 (0.999–1.0) | .408 | 1.0 (0.999–1.0) | 0.376 |

| Birth place | 91 | ||||

| US | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Non-US | 1.77 (0.803–3.904) | .157 | 1.437 (0.485–4.259) | 0.513 | |

| Healthcare coverage | 142 | ||||

| Private/HMO | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Medicaid | 1.044 (0.409–2.668) | .928 | 1.28 (0.444–3.667) | .65 | |

| Medicare | 0.971 (0.413–2.284) | .947 | 0.186 (0.024–1.442) | .108 | |

| Median household Income* | 140 | ||||

| 38K or less | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| $38–47K | 0.588 (0.201–1.721) | .332 | 0.702 (0.168–2.939) | 0.628 | |

| $48–63K | 0.823 (0.298–2.271) | .707 | 1.095 (0.292–4.102) | 0.893 | |

| $64K or more | 0.794 (0.336–1.875) | .599 | 0.844 (0.256–2.778) | 0.78 | |

| Skin lesions | |||||

| Patches | 149 | ||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 0.131 (0.065–0.263) | <.001 | 0.172 (0.068–0.439) | <.001 | |

| Plaques | 149 | ||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 2.058 (1.027–4.126) | .042 | 2.6 (0.971–6.961) | 0.057 | |

| Tumors and nodules | 149 | ||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 7.634 (3.209–18.162) | <.001 | 10.35 (3.499–30.612) | <0.001 | |

| Erythroderma | 149 | ||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 6.04 (2.521–14.467) | <.001 | 6.001 (1.878–19.17) | 0.002 | |

| Folliculotropic | 149 | ||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 2.411 (0.852–6.826) | .097 | 3.336 (0.981–11.346) | 0.054 | |

| Hyperpigmented lesions | 145 | ||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 1.289 (0.617–2.693) | .5 | 1.318 (0.486–3.57) | 0.587 | |

| Hypopigmented lesions | 145 | ||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 0.044 (0.006–0.32) | .002 | - | - | |

| Clinical Stage | 149 | ||||

| IA | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| IB | 0.79 (0.22–2.831) | .717 | 0.533 (0.033–8.624) | .658 | |

| IIA | 4.405 (1.222–15.882) | .023 | 12.195 (1.331–111.718) | .027 | |

| IIB | 11.106 (3.033–40.664) | <.001 | 35.857 (3.912–328.689) | .002 | |

| IIIA / IIIB | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| IVA / IVB | 8.939 (2.779–28.758) | <.001 | 19.202 (2.235–164.974) | .007 | |

| Early/Late stage disease | 149 | ||||

| Early stage (IA-IIA) | 0.1 | 1.0 | |||

| Late stage (IIB-IVB) | 6.838 (3.385–13.811) | <.001 | 11.365 (4.077–31.68) | <.001 | |

| T stage | 149 | ||||

| T1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| T2 | 1.568 (0.509–4.828) | .433 | 2.692 (0.319–22.696) | .363 | |

| T3 | 12.043 (3.355–43.231) | <.001 | 32.933 (3.591–302.049) | .002 | |

| T4 | 5.825 (1.707–19.877) | .005 | 14.353 (1.617–127.425) | .017 | |

| N stage | 149 | ||||

| N0 | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | ||

| N1/2 | 5.362 (2.228–12.906) | <.001 | 9.682 (2.378–39.417) | .002 | |

| Nx | 11.506 (4.43–29.879) | <.001 | 40.566 (10.152–162.101) | <.001 | |

| N3 | 9.269 (2.918–29.443) | <.001 | 19.186 (3.157–116.613) | .001 | |

| M stage | 149 | ||||

| M0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| M1 | 3.979 (0.94–16.841) | .061 | 7.567 (1.7–33.683) | .008 | |

| B stage | 149 | ||||

| B0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| B1 | 7.298 (2.127–25.043) | .002 | - | - | |

| B2 | 5.196 (2.371–11.388) | <.001 | 5.755 (2.132–15.531) | .001 | |

| Blood work | |||||

| WBC | 134 | ||||

| Normal | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Elevated | 4.564 (1.754–11.878) | .002 | 5.224 (1.579–17.285) | .007 | |

| Lymphocytes Count | 134 | ||||

| Normal | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Elevated | 5.156 (1.135–23.419) | .034 | 3.69 (0.453–30.046) | .222 | |

| Eosinophils Count | 133 | ||||

| Normal | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Elevated | 1.93 (0.662–5.627) | .229 | 3.894 (1.241–12.217) | .02 | |

| LDH | 122 | ||||

| Normal | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Elevated | 7.085 (2.662–18.855) | <.001 | 5.49 (1.782–16.918) | .003 | |

Abbreviations: US, United States; HMO, health maintenance organization; WBC, white blood count; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase

Median household income national quartile for patient residential ZIP code

Disease Progression and Prognostic Factors in Early-Stage MF

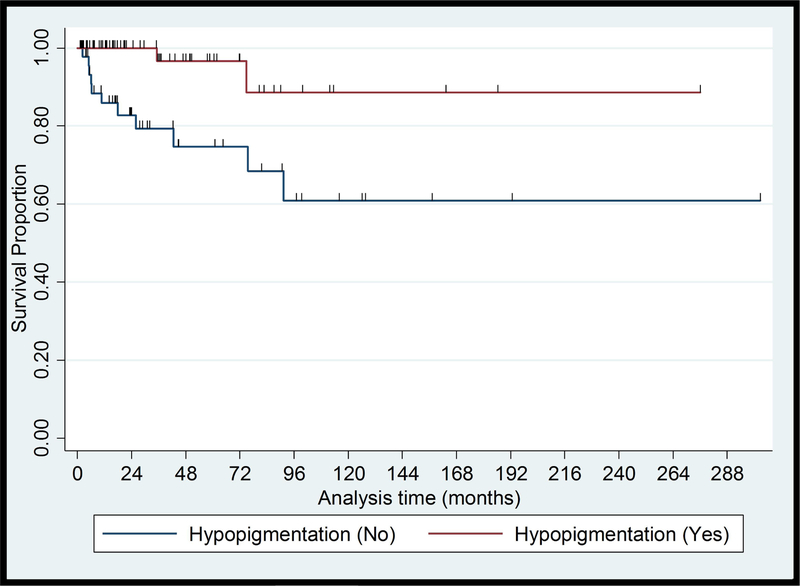

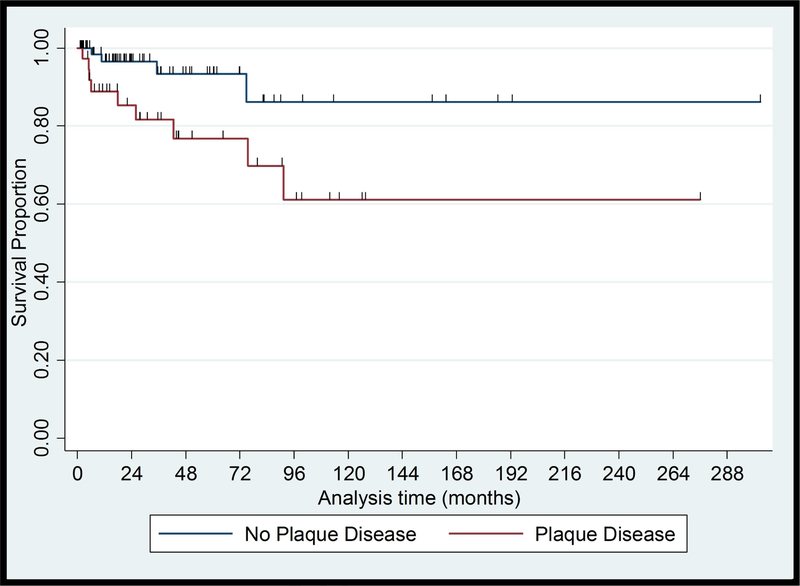

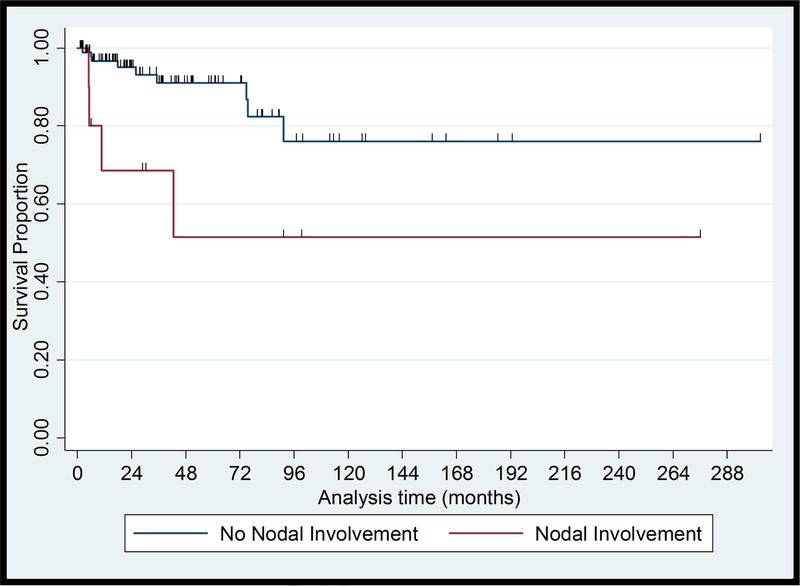

Of 115 patients with early-stage MF, 6 patients (5%) developed skin tumors, 2 (2%) developed erythroderma and 4 (3%) developed extracutaneous disease after a median (range) follow-up of 15 (2–93) months. One patient progressed from clinical stage IA to IB. None of the 12 patients who progressed to advanced-stage disease had presented to us initially with hypopigmented lesions only; one patient had hypo- and hyperpigmented patches, one had localized poikilodermatous lesions, ten had hyperpigmented and/or erythematous lesions, and most of them had plaques (9/12). One progressed case presented with a CD8+ immunophenotype while seven had CD4+ disease. 6/11 (55%) of the cases that progressed had elevated LDH at presentation. Six (5%) patients who progressed to advanced-stage disease eventually died of CTCL after a median (range) follow-up of 74 (9–98) months. In univariate analysis, no association was found between PFS and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. PFS was associated with hypopigmentation (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03–0.66; P=.013), plaques (HR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.01–11.45; P=.038) and Nx stage (HR, 34.641; 95% CI, 6.15–195.18; P=<.001). Survival curves for these characteristics are shown in Figure 1. Multivariate PFS analysis adjusting for sex, healthcare coverage, income, age at diagnosis, and diagnostic delay showed that hypopigmented lesions and patch lesions were associated with better PFS, while Nx stage and elevated LDH were associated with worse PFS (Table III).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Plots of Progression Free Survival from presentation in Black Patients with Early-stage Mycosis Fungoides

(A) Hypopigmented lesions, Log rank = 0.013

(B) Plaques, Log rank = 0.038

(C) Lymph Node involvement, Log rank = 0.02

Table III.

Multivariable Overall Survival and Progression Free Survival (PFS) Analyses in 115 Black Patients with Early-stage Mycosis Fungoides

| Characteristic | Overall Survival (OS) from presentation | Progression Free Survival (PFS) from presentation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Patches | 0.09 (0.01–0.75) | .03 | 0.08 (0.01–0.69) | .02 |

| Plaques | 4.08 (0.66–25.25) | .13 | 1.51 (0.36–6.36) | .58 |

| Hypopigmented lesions | 0.13 (0.01–1.20) | .07 | 0.10 (0.02–0.63) | .014 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| T2 | 3.04 (0.49–18.87) | .23 | 0.53 (0.11–2.43) | .41 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| N1/2 | 3.96 (0.95–16.49) | .06 | 0.96 (0.17–5.49) | .97 |

| Nx | 28.47 (2.29–354.19) | .009 | 61.35 (5.50–648.38) | .001 |

| Elevated WBC | 37.80 (1.65–868.41) | .02 | 4.57 (0.19–111.56) | .35 |

| Elevated LDH | 7.80 (1.39–43.84) | .02 | 7.80 (1.39–43.84) | .02 |

Adjusted for sex, insurance type, income, age at diagnosis, and diagnostic delay

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood count; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase

Discussion

Other than the higher incidence rates of CTCL and MF/SS among the AA/black population in the US,3,4,20,21 AA/black patients with MF/SS have been found to present at a significantly younger age4,7,11–14 and with a female predominance7,11–13 when compared to white patients. Survival analyses of the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data sets demonstrated that OS and DSS in AA/black patients with MF were significantly worse compared to white patients despite accounting for demographic factors and tumor stage.6,21 A recent study of the US National Cancer Database showed that AA/black patients with MF had a significantly shorter OS after adjustment for disease characteristics, socioeconomic factors, and types of treatment.11 It has been concluded that racial disparities in survival are likely secondary to differences in the underlying biology of the disease.11 It has also been suggested that AA patients may require more aggressive initial treatment,11 and that, in particular, AA women with early-onset disease should be considered for aggressive therapy, such as allogeneic transplantation.7 Our experience from the multidisciplinary cutaneous lymphoma clinic at MSKCC shows that AA/black patients with MF/SS present with diverse clinicopathological characteristics and heterogenous outcomes. Certain subsets of black patients have poor outcomes while others have an excellent prognosis.

The demographics of our cohort were consistent with previous reports on an earlier onset of disaese4,11,13,14 and female predominance11,13,14 among AA/black patients, but unlike previous studies that suggested poor outcomes in AA females with early-onset disease, our study did not show sex and age to be associated with disease stage, absolute deaths, progression or survival, other than the expected association of older age at diagnosis with shorter OS.22 Interestingly, our results demonstrated that AA/black patients with a longer history of symptoms prior to diagnosis were more likely to have longer survival.

It has been suggested in the literature that socioeconomic differences and a lack of access to medical care may play a role in racial disparities in MF/SS.6,23 Our study failed to reveal any association between disease severity and outcome with socioeconomic characteristics including birthplace, healthcare coverage, median household income and poverty rate among the studied AA/black patients. Our study included only patients who were seen at MSKCC and therefore it most likely under-represents AA/black patients of low socioeconomic status and non-insured patients, limiting the generalizability of our results. However, despite these limitations, 20% of the studied patients were immigrants, 28% had government insurance, 21% resided in areas where median household income was within the lowest quartile, and 35% resided in an area with a poverty rate of over 20%. Despite being performed in a tertiary cancer center, most of the MF/SS patients who present to us have early-stage disease. A definitive diagnosis in early-stage MF might be difficult to make, therefore we excluded cases who were not unequivocally diagnostic. It is possible that we missed patients who did not come to MSKCC due to disease severity, or patients with progressive disease who expired before being referred to us. Despite these limitations, we believe our cohort represents the full spectrum of disease severity seen in MF/SS.

Our results showed that the course of MF/SS in AA/black patients is variable, and it confirmed the prognostic value of the standard staging system and the revised TNMB classification system24 in this population.

Hypopigmented MF is a variant that predominantly appears in patients with skin of color and usually has an excellent prognosis.24,25 Hypopigmented lesions may appear as the sole manifestation of MF or with concomitant erythematous and hyperpigmented lesions. Almost half of the studied patients (n=71, 45%) presented to us with hypopigmented lesions. About one half of them (37 patients) had only hypopigmented lesions while a mixture of hypo- and hyperpigmented or erythematous lesions was seen in the other half (34 patients). Over 80% of all death cases (28/34) and disease progression (22/27) observed in our study, occurred in patients with erythema/hyperpigmentation without hypopigmentation. The presence of any hypopigmented lesions was highly associated with longer OS (HR, 0.04; 95% CI, 0.006–0.32; P=.002) and none of the patients with hypopigmented lesions died due to disease. Many of the patients with early-stage disease had erythematous / hyperpigmented lesions without hypopigmentation (43%), and the absence of hypopigmentation has been shown to be associated with poorer PFS. Clinicians should be careful when evaluating dark skinned patient with MF for hypopigmentation as patients with a history of ulcerated lesions may show depigmented areas in the scarred skin, prior radiation therapy may result in dyspigmentation, and depigmenting skin disorders, such as vitiligo, may appear concomitantly. Skin biopsy may be recommended to establish or confirm the diagnosis of MF in hypopigmented lesions. Patch versus plaque stage disease and elevated LDH were also significantly associated with disease progression in AA/black patients with early-stage disease, supporting previous data on their prognostic value in MF/SS.24 Among patients with early-stage disease the presence of abnormal lymph nodes per clinical examination (Nx) was independently associated with shorter survival and PFS. The immunophenotype data based on IHC stains results at presentation was available in 60% of the patients. No death cases were recorded in 29 patients who presented with CD8+ disease, whereas 30% of the 63 patients with CD4+ MF died. Our findings are in line with the literature reporting an indolent course in the CD8+ variant of MF, and a high prevalence of CD8+ MF among AA/black patients.26 We did not re-review the IHC in this study, and studies with comprehensive immunophenotyping are warranted to better delineate the pathogenic mechanisms behind the association of hypopigmentation, patch-stage disease and CD8+ phenotype in black patients.27,28 Our study highlights the diverse manifestations and heterogenous outcomes of MF/SS in AA/black patients. Demographic and socioeconomic factors did not have prognostic relevance, while certain clinicopathologic features were significantly associated with survival and progression. Decisions on the management and treatment in MF/SS should take into account specific clinical and pathological prognostic factors and should not be based on demographic parameters or race alone.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Abbreviation

- MF/SS

mycosis fungoides / Sézary syndrome

- AA

African American

- CTCL

cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- MSKCC

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

- HTLV

human T-cell lymphotropic virus

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- WBC

white blood cell count

- LCT

large cell transformation

- EOS

eosinophil count

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- OS

overall survival

- DSS

disease-specific survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

IRB approval status: Reviewed and approved by MSKCC IRB

Conflict of interest disclosures: Steve M. Horwitz has received both research funding/grant support and honoraria/consulting fees from ADCT Therapeutics, Aileron, Forty-Seven Infinity/Verastem Kyowa-Hakka-Kirin, Millennium / Takeda and Seattle Genetics; Research/grant support from Celgene and Trillium; and honoraria consulting fees from Affimed, Angimmune, Beigene, Corvus, Innate Pharma, Kura, Merck, Miragen, Mundipharma, Portola, and Syros Pharmaceutical. Alison J. Moskowitz received honoraria from Seattle Genetics; Consulting or advisory role for Seattle Genetics, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, Miragen Therapeutics, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, ADC Therapeutics, Cell Medica, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Erytech PharmaResearch; and received funding from Incyte (Inst), Seattle Genetics (Inst) Merck (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst). All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Prior presentation: This study was presented at the ISCL Scientific & Annual General Meeting at the 2019 Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID) Meeting in Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Aizer AA, Wilhite TJ, Chen MH, et al. Lack of reduction in racial disparities in cancer-specific mortality over a 20-year period. Cancer 2014;120(10):1532–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirtane K, Lee SJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in hematologic malignancies. Blood 2017;130(15):1699–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korgavkar K, Xiong M, Weinstock M. Changing incidence trends of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149(11):1295–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson LD, Hinds GA, Yu JB. Age, race, sex, stage, and incidence of cutaneous lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2012;12(5):291–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford PT, Devesa SS, Anderson WF, Toro JR. Cutaneous lymphoma incidence patterns in the United States: a population-based study of 3884 cases. Blood 2009;113(21):5064–5073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nath SK, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Poorer prognosis of African-American patients with mycosis fungoides: an analysis of the SEER dataset, 1988 to 2008. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2014;14(5):419–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun G, Berthelot C, Li Y, et al. Poor prognosis in non-Caucasian patients with early-onset mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60(2):231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imam MH, Shenoy PJ, Flowers CR, Phillips A, Lechowicz MJ. Incidence and survival patterns of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma 2013;54(4):752–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstock MA, Reynes JF. The changing survival of patients with mycosis fungoides: a population-based assessment of trends in the United States. Cancer 1999;85(1):208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang S, Bartnicki S, Gustavson C, Desimone J. Racial differences in survival of patients with Sezary syndrome in the United States: A population-based study of 204 cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2016;74(5):AB182. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su C, Nguyen KA, Bai HX, et al. Racial disparity in mycosis fungoides: An analysis of 4495 cases from the US National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77(3):497–502.e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai M, Liu S, Parker S. Clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and survival of 393 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome in the southeastern United States: a single-institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72(2):276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balagula Y, Dusza SW, Zampella J, Sweren R, Hinds GA. Early-onset mycosis fungoides among African American women: a single-institution study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71(3):597–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zampella JG, Hinds GA. Racial differences in mycosis fungoides: a retrospective study with a focus on eosinophilia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68(6):967–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood 2007;110(6):1713–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016;127(20):2375–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood 2005;105(10):3768–3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arya S, Binney Z, Khakharia A, et al. Race and Socioeconomic Status Independently Affect Risk of Major Amputation in Peripheral Artery Disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreisel K, Flagg EW, Torrone E. Trends in pelvic inflammatory disease emergency department visits, United States, 2006–2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218(1):117.e111–117.e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973–2002. Arch Dermatol 2007;143(7):854–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstock MA, Gardstein B. Twenty-year trends in the reported incidence of mycosis fungoides and associated mortality. Am J Public Health 1999;89(8):1240–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebowitz E, Geller S, Flores E, et al. Survival, disease progression and prognostic factors in elderly patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a retrospective analysis of 174 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33(1):108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs 2009;21(4):170–177, 206; quiz 178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scarisbrick JJ, Kim YH, Whittaker SJ, et al. Prognostic factors, prognostic indices and staging in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: where are we now? Br J Dermatol 2014;170(6):1226–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodney IJ, Kindred C, Angra K, Qutub ON, Villanueva AR, Halder RM. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a retrospective clinicohistopathologic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31(5):808–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Escala ME, Kantor RW, Cices A, et al. CD8(+) mycosis fungoides: A low-grade lymphoproliferative disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77(3):489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Cerroni L, Medeiros LJ, McCalmont TH. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: frequent expression of a CD8+ T-cell phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26(4):450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geller S, Lebowitz E, Pulitzer M, Myskowski PL. Understanding racial disparities in mycosis fungoides through international collaborative studies. Br J Dermatol 2019;180(5):1263–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]