Abstract

Chromatin is folded into successive layers to organize linear DNA. Genes within the same topologically associating domains (TADs) demonstrate similar expression and histone-modification profiles, and boundaries separating different domains have important roles in reinforcing the stability of these features. Indeed, domain disruptions in human cancers can lead to misregulation of gene expression. However, the frequency of domain disruptions in human cancers remains unclear. Here, as part of the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) Consortium of the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), which aggregated whole-genome sequencing data from 2,658 cancers across 38 tumor types, we analyzed 288,457 somatic structural variations (SVs) to understand the distributions and effects of SVs across TADs. Notably, SVs can lead to the fusion of discrete TADs, and complex rearrangements markedly change chromatin folding maps in the cancer genomes. Notably, only 14% of the boundary deletions resulted in a change in expression in nearby genes of more than twofold.

Subject terms: Data mining, Cancer, Gene expression

A pan-cancer genomic analysis reports the effects of structural variations on chromatin domains (TADs). Most TAD disruptions do not result in appreciable changes in expression of nearby genes.

Main

Genome organization inside the nucleus is hierarchically organized1. Chromosomes are organized into chromosome territories2. Inside chromosome territories, certain regions of the chromatin are attached to the nuclear periphery and form repressive nuclear lamin-associated domains (LADs)3. Recent chromosome conformation studies have revealed that mammalian chromosomes are structured into largely tissue-invariant TADs in which the DNA interactions are more frequent within a given domain than with regions in other domains4,5. TADs are considered to represent functional domains because a given TAD encompasses the regulatory elements for the genes inside the same domain6,7. Therefore, the integrity of the domain structures is important for the proper regulation of genes8–12. The disruption of domain boundaries can result in ectopic interactions between neighboring domains and affect the regulation of nearby genes5,9. Regulatory landscapes are an important part of human malignancies, and studies have shown that the ‘hijacking’ of enhancers can lead to overexpression of oncogenes (for example, growth factor independent 1 family oncogenes (GFI1 and GFI1B)) in medulloblastoma13 or proto-oncogene MECOM activation due to an inversion between TADs in acute myeloid leukemia cells, which facilitates tumor formation14. Several other studies have reported the deregulation of chromatin folding structures in different cancer types11,15,16. Hence, genomic rearrangements can have a significant role in the reshuffling of TAD structures that results in altered gene regulation. Despite these recent examples of SVs that result in altered local enhancer–promoter landscapes, the frequency of such regulatory architecture rearrangements in cancer genomes remains unclear. Similarly, whether there are loci affected by potential changes in regulatory structure outside of those currently reported in the literature is unknown. To address these questions, we comprehensively characterized the effects of different SVs on TADs and gene-expression patterns observed in various tumor types to expand understanding of the link between chromatin folding and genomic rearrangements in cancer genomes.

Results

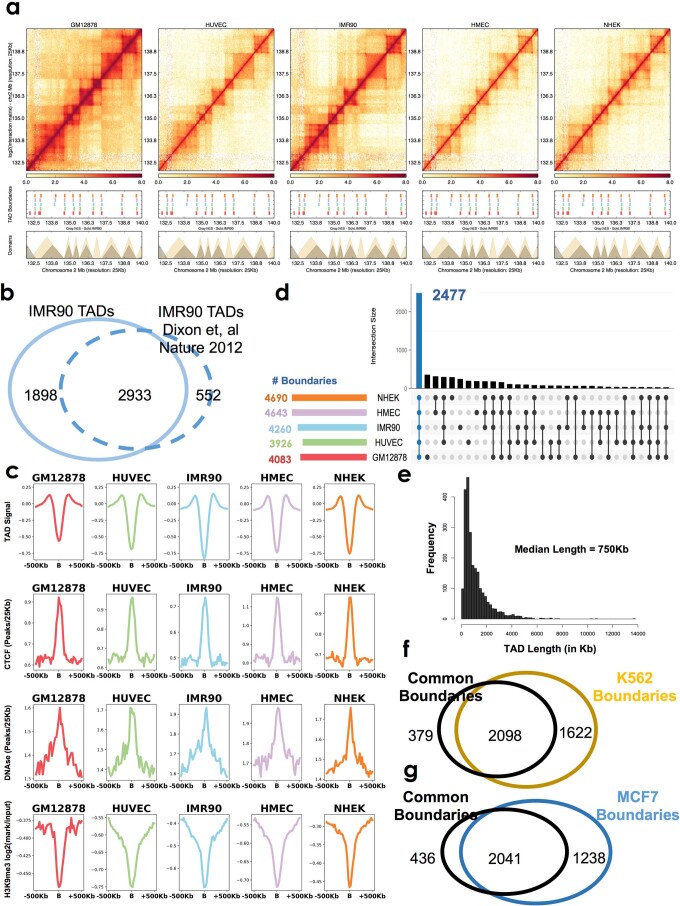

TAD boundaries are affected by different types of somatic SV in cancer genomes

Previous reports have indicated that TADs are a largely cell-type-invariant feature of genome organization4,17. In this pan-cancer analysis, we sought to generate a common set of boundaries observed in different cell types. We used high-resolution chromosome conformation (Hi-C) datasets from five human cell lines that represent three distinct embryonic germ layers (GM12878 and HMEC, mesoderm; IMR90, endoderm; HUVEC and NHEK, ectoderm)17 to identify TAD boundaries in different cell types (Extended Data Fig. 1a). We called TAD boundaries from 25-kb-binned Hi-C data for each cell type with an insulation score18 approach. This method calculates a score (TAD signal), for each bin, for the average interactions with the nearby loci for a 2-Mb genomic window. Boundaries are determined as regions with local insulation minima along the diagonal of the Hi-C matrix18. As a result, a number of boundaries, which ranged from 3,926 to 4,690, were found for different cell types. We next investigated whether our TAD boundary calls were consistent with the previously reported boundaries and showed attributes of TAD boundaries. To test this, we compared available boundary regions for IMR90 cells that were identified using a directionality-based approach (with a bin size of 40 kb)4. Our IMR90 boundary calls were highly overlapping (>84%) with published boundaries (Extended Data Fig. 1b). This showed that the current boundary regions were comparable with previously mapped boundaries even though they were identified at a different Hi-C resolution and using a different detection algorithm. Furthermore, we observed known TAD boundary signatures4 around our boundary calls for each cell type (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Across all cell types, we identified a common set of 2,477 boundaries (Supplementary Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 1d). There was a significant (P < 10−6) overlap (a 50-kb distance was allowed) between TAD boundaries among all profiled cell types. The median distance between the common boundaries was approximately 750 kb, consistent with the reported median TAD size in human cells4,19 (Extended Data Fig. 1e). The resulting 2,477 common regions were used for the rest of the analyses (referred to as boundaries hereafter).

Extended Data Fig. 1. Identification of TAD boundaries in different cell types.

a, An example region (chromosome2:132-140 Mb) presenting similar chromatin folding in 5 different cell types. Heatmaps represent Hi-C data for each cell type. Tiles represent TAD boundary calls for each cell type (red: GM12878; green: HUVEC; blue: IMR90; purple: HMEC; orange: NHEK). Triangles depict TAD calls for human ES cells (gray) and IMR90 cell line (gold) from a previous study4. b, Venn diagrams show overlap between current IMR90 boundaries (solid) with boundaries (dashed) identified from a previous study4 for the IMR90 cell line. c, Aggregate plots show average cell-type specific enrichment levels for Hi-C interaction levels (TAD signal), CTCF binding sites, DNAseI hypersensitivity regions and H3K9me3 ChIP-seq levels compared to input DNA around each cell type’s TAD boundaries. d, Overlaps between TAD boundaries among 5 different cell lines. Horizontal bars represent total number of TAD boundaries per cell type. Vertical bars represent number of intersecting boundaries between cell types. Combination matrix (below), circles indicate that denote cell types are part of the intersection for each vertical bars. Common boundaries among all cell types represented with blue vertical bar. e, Histogram represents distribution of TADs length. f, Venn diagrams show overlap between common TAD boundaries and leukemia (K562) cell line TAD boundaries. g, Venn diagrams show overlap between common TAD boundaries and breast cancer (MCF) cell line TAD boundaries.

Next, to test whether the overall chromatin architecture is similar in cancer and non-cancer cells, we intersected these boundaries with the TAD boundaries found in cancer cell lines. We observed a high overlap with boundaries from a leukemia cell line K562 (ref. 17) and a breast cancer cell line MCF7 (ref. 20) (85% and 83.4%, respectively; Extended Data Fig. 1f,g). These analyses revealed that a significant (P < 10−7) percentage of boundaries was conserved between normal and malignant cells. We next examined the enrichment of CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF)-binding and DNase I hypersensitivity sites, as well as active transcription start sites and heterochromatic regions around boundaries from various cell types that have previously been profiled by the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) consortium19 and the Roadmap Epigenome project21. We observed that CTCF-binding sites and active promoter marks were enriched, whereas the heterochromatin state was depleted at the boundaries. In addition, TAD signal levels were the lowest at the boundaries compared with flanking sites (Fig. 1a), consistent with the role of TAD boundaries in the reduction of the contacts between adjacent domains. Overall, these common 2,477 boundaries exhibited the genomic features of TAD boundaries across different human cell types.

Fig. 1. TAD boundaries are affected by different types of somatic SVs in cancer genomes.

a, Profiles of TAD signals, active transcription start sites (TSS), CTCF peaks, DNase I hypersensitivity and heterochromatic states around common TAD boundaries. Dashed lines represent enrichment levels for the shuffled boundaries. b, The percentage of short-range SVs (length ≤ 2 Mb) across TADs (shaded) and within TADs (solid) for different SV types. SVs that occur across TADs are referred to as BA-SVs. c, Observed (arrows) and expected distribution (histograms) of BA-SVs. The expected distribution is based on randomly shuffled boundary data. d, Number of affected boundaries (x axis) per short-range SV length cut-off (y axis). The size of the circles indicates the portion of BA-SVs that affect the specific number of boundaries for each length scale. BA-deletion, BA-inversions, BA-duplications and BA-complex rearrangements are shown in red, cyan, green and orange, respectively. e, Histograms represent the length distribution of somatic and germline deletions in the PCAWG cohort within the 75–250 kb range. Pie charts show the percentage of deletions across TADs (shaded) (4.1% for somatic and less than 0.1% for germline events) and within TADs (solid).

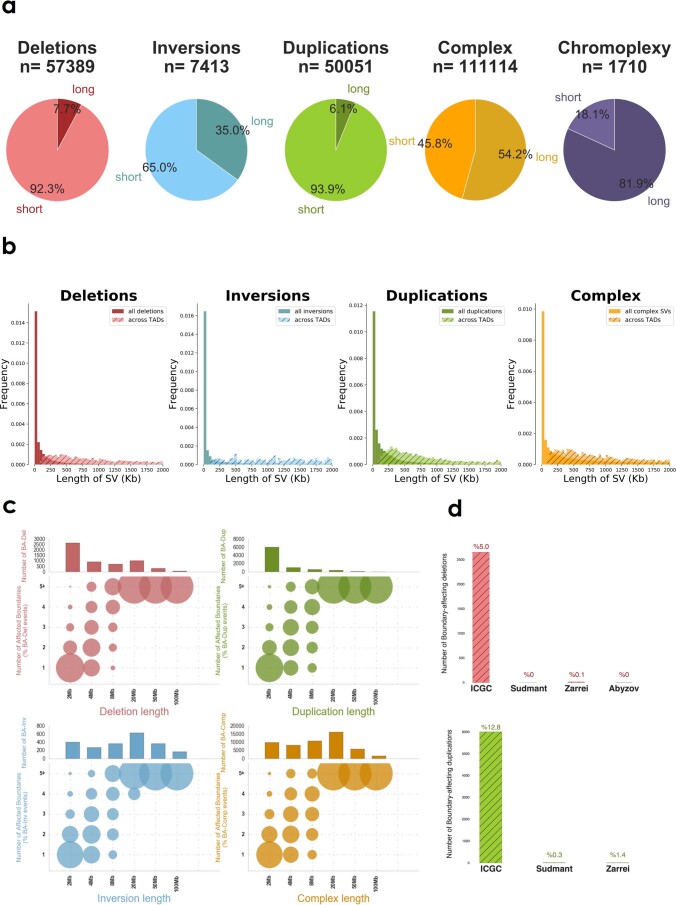

To understand the effects of SVs on TAD boundaries in human cancers, we used 288,457 high-confidence somatic SVs as part of the ICGC PCAWG project. The PCAWG Consortium aggregated whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data from 2,658 cancers across 38 tumor types generated by the ICGC and TCGA projects. These sequencing data were re-analyzed with standardized, high-accuracy pipelines to align to the human genome (reference build hs37d5) and identify germline variants and somatically acquired mutations, as described in the lead paper of the PCAWG Consortium22. We used SV breakpoint orientations as a measurement to classify deletions, inversions, duplications or complex rearrangements as described previously23. Complex rearrangements included chromothripsis24 and other alterations, which covered SV break-ends with concomitant deletions, inversions or duplications. SVs were further categorized into two subgroups based on the length of the events—SVs that were longer than 2 Mb in genomic length (long-range SVs) and shorter than 2 Mb in genomic length (short-range SVs). The majority of deletions, inversions and duplications could be categorized as short-range; however, complex events tended to be longer in length (Extended Data Fig. 2a). In this study, we focused on short-range SVs because long-range SVs could affect multiple boundaries due to the genomic length of the event. We identified SVs that affected the TAD boundaries (boundary affecting (BA)) as the ones that spanned the whole length of a boundary (around 75 kb). As a result, 5.0%, 8.5%, 12.8% and 19.9% of all deletions, inversions, duplications and complex events were called BA events, respectively (Fig. 1b). Compared with the expected number of boundary disruptions based on randomly shuffled boundaries, these ratios are strongly enriched in BA-duplications (P < 10−4, 1.43-fold enrichment). In contrast, we observed a depletion (0.87-fold enrichment, P = 0.052) in BA-deletions, whereas BA-inversions and BA-complex events occurred at expected levels (P > 0.05) compared with the shuffled TAD boundaries (Fig. 1c). Overall, these results suggest that deletions tended to occur within the same TAD, whereas duplications tended to span regions across different TADs.

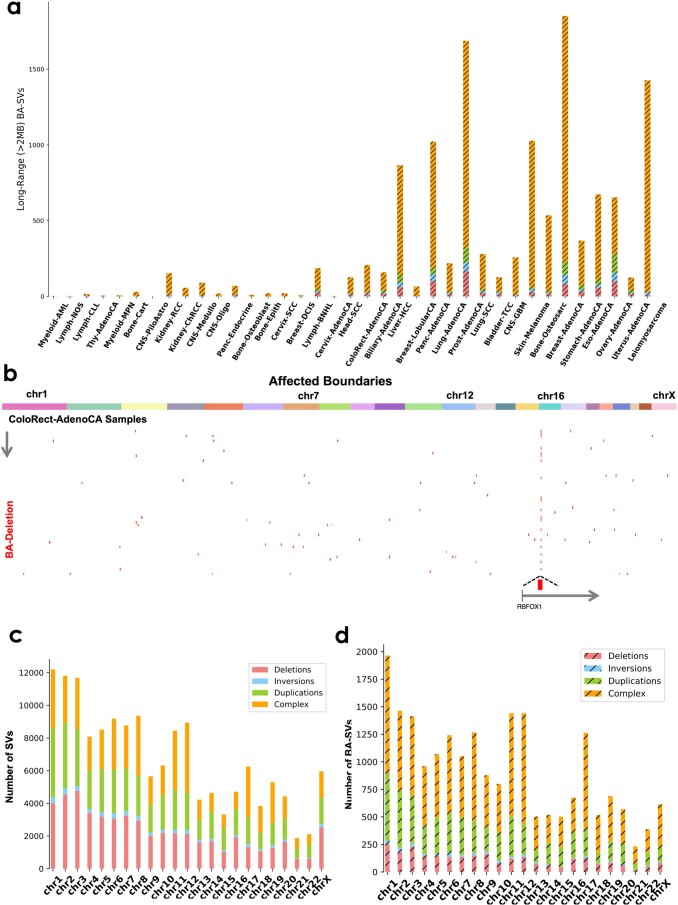

Extended Data Fig. 2. Distribution of boundary-affecting structural variations in human cancers.

a, Pie charts show the percentages of long-range (>2 Mb) and short-range (< = 2 Mb) for deletions (red), inversions (cyan), duplications (green), complex rearrangements (orange) and chromoplexy events (purple) in all PCAWG samples. b, Histograms show length distribution of all short-range SVs (solid) or Boundary Affecting SVs (dashed) for deletions (red), inversions (cyan), duplications (green) and complex rearrangements (orange) in all PCAWG samples. c, Number of affected boundaries (x-axis) per different short-range SV length cut-offs (y-axis). The size of the circles indicates the portion of BA-SVs affecting the specific number of boundaries for each length scale. BA-deletion, BA-inversions, BA-duplications and BA-complex rearrangements are represented with red, cyan, green and orange colors, respectively. d, Bar charts show TAD-boundary affecting top) deletions (red) and bottom) tandem-duplications (green) in cancer genomes, and in genomes of healthy individuals from three different studies.

In cancer cells, boundaries are affected to various degrees due to structural alterations, which suggests that some mechanistic differences could cause different SV types. Length distributions of the BA-SVs were uniformly distributed (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Most of the BA-SVs targeted a single boundary; 74% of BA-deletions, 65% of BA-inversions, 71% of BA-duplications and 64% of BA-complex events affected a single boundary per variant (Fig. 1d). The number of affected boundaries did not markedly change with the minimum length of the SVs (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 2c). The majority (98.4%) of the boundaries were affected in cancer genomes, although a few boundaries were located in the low-mappability regions of the genome. Interestingly, TAD boundaries are significantly less likely (P < 0.02) to be affected by known deletion and duplication polymorphisms derived from genomes of healthy human populations25–27 (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Genomic length of the germline alterations tends to be shorter compared with somatic alterations observed in tumors due to negative selection against large SVs in the germline28. Therefore, we selected germline and somatic deletions with a genomic length between 75 kb and 250 kb that occurred in all cancer samples (Fig. 1e). This filtering ensured that the selected somatic (median, 137 kb) or germline (median, 113 kb) deletions had the length potential to disrupt TAD boundaries. We observed that germline deletions that affected TAD boundaries were rare (less than 0.1%; 6 affected out of total 924 deletions) compared with somatic deletions (4.1%), even in cases in which similar genomic ranges and less than 1% of the total boundaries were affected by germline events, suggesting that germline variations in TAD boundaries may not be as well tolerated as similar somatic alterations.

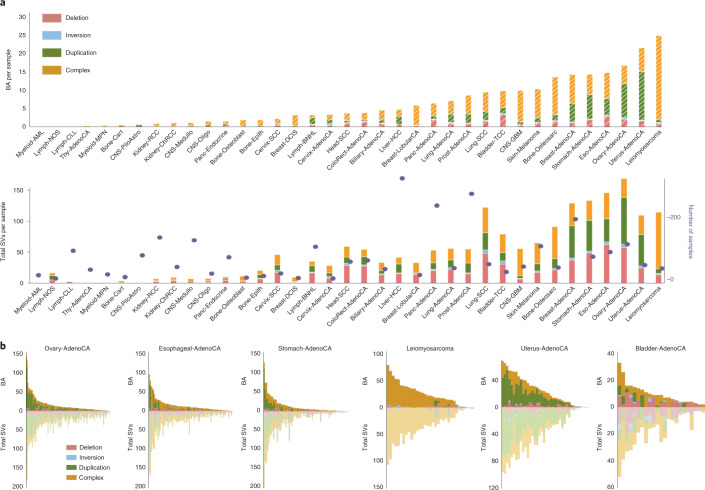

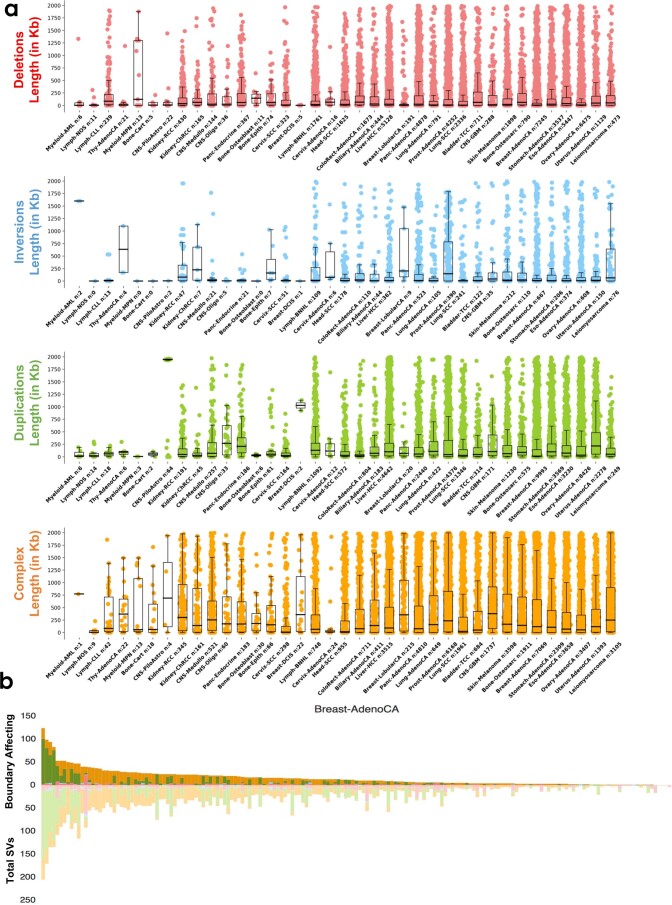

Chromatin folding disruptions are specific to histological subtypes

We next focused on the distributions of BA-SVs across 38 different histological cancer subtypes22. The number of BA-SVs generally followed the total number of SVs in a given cancer type. Our analysis revealed that, among all cancer types, leiomyosarcoma and uterus adenocarcinoma had higher numbers with—on average—25 and 22 BA-SVs per sample, respectively, compared with a median of around 7 BA-SVs per sample across all cancer samples (Fig. 2a, b). Ovarian, esophageal and breast adenocarcinomas also contained high numbers of BA-SVs with—on average—20, 19 and 18 BA-SVs per sample, respectively. On the other hand, hematopoietic cancers (myeloid-MDS or myeloid-AML) had the lowest BA-SV rates. Only glioblastoma samples (CNS-GBM) showed lower-than-expected BA-SVs (P < 10−3) across all cancer types. The median SV length of a given cancer type was not strongly correlated with the observed distributions (r2 = 0.03–0.45) (Extended Data Fig. 3a). The observed differences in BA-SV rates are likely driven by the differences in the burden and mechanisms of SVs across histological types. For instance, leiomyosarcoma and esophageal adenocarcinoma had a higher complex SV burden and, as a result, observed BA events were also mostly complex rearrangements (Fig. 2b), whereas ovary and stomach adenocarcinoma samples contained BA-duplications due to an overall higher duplication rate (Fig. 2b). Similarly, the total number of SVs in an individual tumor affects the observed BA-SVs in that sample (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 3b). Long-range BA-SVs had similar distributions across histological types. Again, leiomyosarcoma and breast adenocarcinoma contained a higher number of BA-SVs compared with other cancer types, whereas leukemia samples had no BA-SVs per sample (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Taken together, our findings show that the impact of BA-SVs is varied substantially across tumor types and these events were reflective of overall SV burden and type.

Fig. 2. Chromatin folding disruptions are specific to histological subtypes.

a, Top, the distribution of the average number of BA-SVs per sample for each histological type22. Bottom, The distribution of the average number of SVs observed in each histological type. Purple dots represent patient numbers for each histological type. Deletions, inversions, tandem duplications and complex rearrangements are shown in red, cyan, green and orange, respectively. b, Per-sample counts of BA-SV (top) and total SV (bottom) events for ovary, esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma cohorts (left), and leiomyosarcoma, uterine adenocarcinoma and bladder adenocarcinoma cohorts (right). Deletions, inversions, tandem duplications and complex rearrangements are shown in red, cyan, green and orange, respectively. Each bar represents a sample and samples are sorted by the number of BA-SV events.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Histology-specific features of boundary-affecting structural variations.

a, Box plots show the length (in Kb) distribution of short-range SVs (deletions: red, inversions: cyan, duplications: green) for each cancer histology subtypes22. The center line is the median; box limits are the upper and lower quantiles; whiskers represent 1.5x the interquartile range. Number of SVs are indicated by each histology name. b, Per sample counts of BA-SVs (top) and total SV (bottom) events for breast adenocarcinoma cohort. Deletion, inversions, tandem-duplications and complex rearrangements are represented with red, cyan, green and orange colors, respectively. Each bar represents a samples and samples are sorted by the number of BA-SV events.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Further investigation of histology-specific features of boundary-affecting structural variations.

a, Distribution of average long-range (length of SV>2 Mb) structural variations (deletion (dashed-red), inversion (dashed-cyan), duplication (dashed-green) and complex rearrangements (dashed-orange)) per sample for each cancer histology subtypes. b, A recurrently deleted TAD boundary in colorectal adenocarcinoma samples near to the RBFOX1 gene. Colored bars on top depict chromosomal locations of the boundaries. Columns of the heatmap are TAD boundaries and rows represent each colorectal adenocarcinoma sample. TAD boundaries affected by BA-deletions are colored in red. Schematic below show the deleted boundary (red box) near to the RBFOX1 gene. c, Distributions of total SV burden (deletions: red, inversions: cyan, duplications: green, complex: orange) across chromosomes. d, Distributions of boundary affecting SVs across chromosomes.

Recurrently affected boundaries in specific cancer types

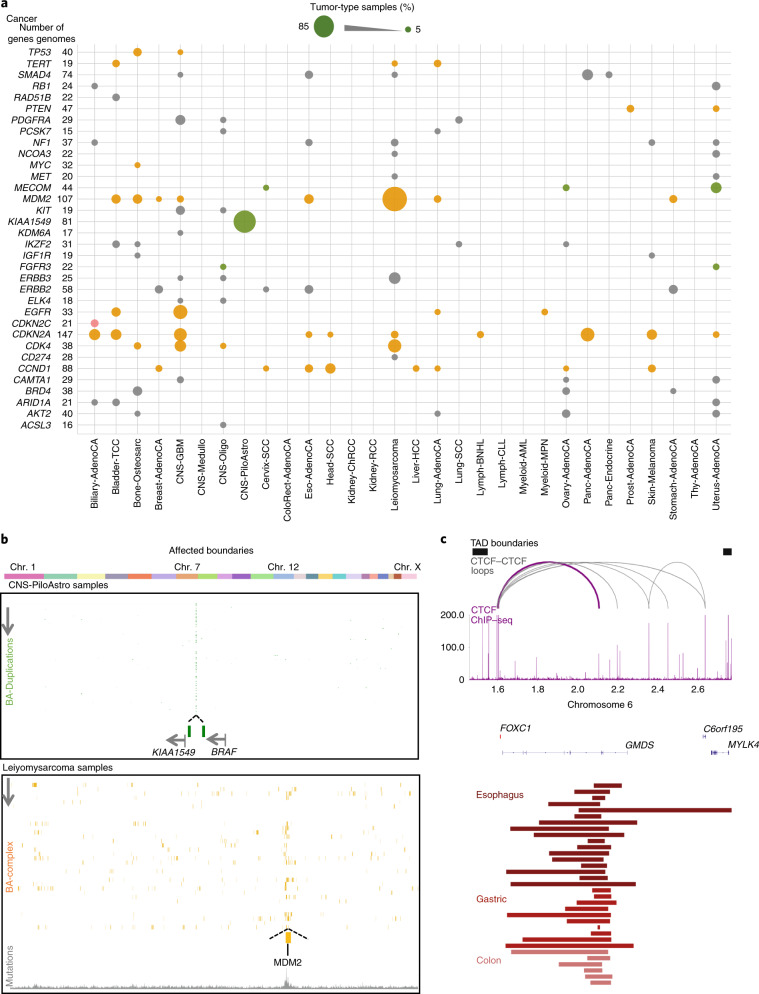

Next, we sought to identify the affected boundaries near known driver genes in the COSMIC cancer gene census29. We noted that many of the boundaries of cancer driver genes were altered in specific histological subtypes (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 2). Of those recurrently affected boundaries, two adjacent boundaries between KIAA1549 and BRAF were prone to BA-duplications specifically in samples of pilocytic astrocytoma (Fig. 3b). This region has previously been implicated in pilocytic astrocytoma, producing an oncogenic fusion between the aforementioned genes30. In addition, boundaries near the MDM2 locus were most affected in leiomyosarcoma (Fig. 3b), likely due to neochromosome formations that included the MDM2 and CDK4 genes31. We also observed a higher mutational load specifically on chromosome 12 in leiomyosarcoma samples (Fig. 3b). Another recurrent BA-SV event was the high number of BA-deletions around RBFOX1 in colorectal adenocarcinoma samples (Extended Data Fig. 4b). We surveyed the BA-SV distributions on individual chromosomes and observed a positive correlation with the number of boundaries (r2 = 0.68–0.92) and gene density (r2 = 0.7–0.85) on a given chromosome (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). Notably, distributions of BA-SVs per chromosome were generally specific to the histology subtype; for example, chromosome 17 was affected predominantly by BA-complex events in breast and esophageal adenocarcinoma samples (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). These findings emphasize the cancer specificity of BA-SVs, in which active mechanisms lead to the overall SV burden and type in different tumor types yield potential changes in TAD structures, especially around cancer driver genes. We next examined SVs that occurred within TADs, which potentially resulted in the disruption of CTCF–CTCF chromatin loops32. We identified a number of chromatin loops that were potentially disrupted in various cancer types (Supplementary Table 3). For instance, a CTCF site near FOXC1 overlaps with recurrent deletions in esophageal, gastric and colon adenocarcinomas (Fig. 3c). Other potentially altered loops include a CTCF site near BCL6 in hepatocellular carcinoma and breast adenocarcinoma, and CLCN4 in colorectal adenocarcinomas (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). Therefore, chromatin folding perturbations can occur at various scales, include TADs and CTCF–CTCF chromatin loops in cancer genomes and recurrently altered boundaries are generally cancer-type specific.

Fig. 3. Recurrently affected boundaries in specific cancer types.

a, Recurrently affected boundaries near known cancer driver genes (y axis) per histological type (x axis). The size of the circles indicates the portion of samples harboring a BA-SV event in a specific histological type. The color of the circles demonstrates the most common SV type (red, deletion; orange, complex; green, duplication; gray, different SV types were observed) in each histological type. b, Top, recurrently duplicated TAD boundaries in pilocytic astrocytoma. Columns of the heat map are TAD boundaries and rows represent each pilocytic astrocytoma sample. TAD boundaries affected by BA-duplications are colored in green. The schematic at the bottom shows the duplicated boundaries (green boxes) between KIAA1549 and BRAF. Bottom, distribution of BA-complex rearrangement (orange) events across chromosomes in each leiomyosarcoma sample. Heat maps show affected TAD boundaries in each leiomyosarcoma sample. The line plot at the bottom shows normalized mutation count. c, A potentially affected CTCF–CTCF chromatin loop in esophageal, gastric and colon adenocarcinoma near FOXC1. Black boxes show TAD boundaries, arcs represent common CTCF–CTCF loops observed in three different cell types (gray). The signal from CTCF chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP–seq) (from the NHEK cell line) analysis is represented by a purple histogram. Red vertical bars indicate deletions in individual samples of esophageal, gastric and colon adenocarcinoma.

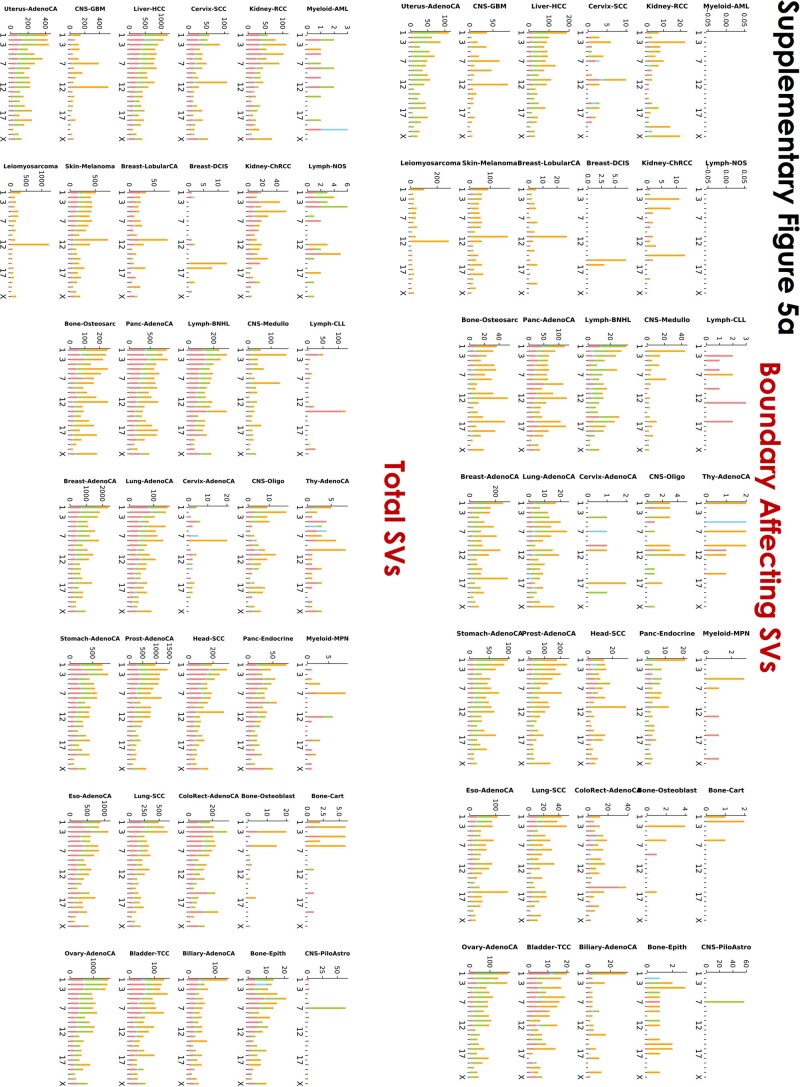

Extended Data Fig. 5. Distribution of structural variation burden in different cancer histology subtypes.

a, Distribution of boundary-affecting (top) and total (bottom) SVs (deletions: red, inversions: cyan, duplications: green, complex: orange) across chromosomes in each cancer histology subtypes22.

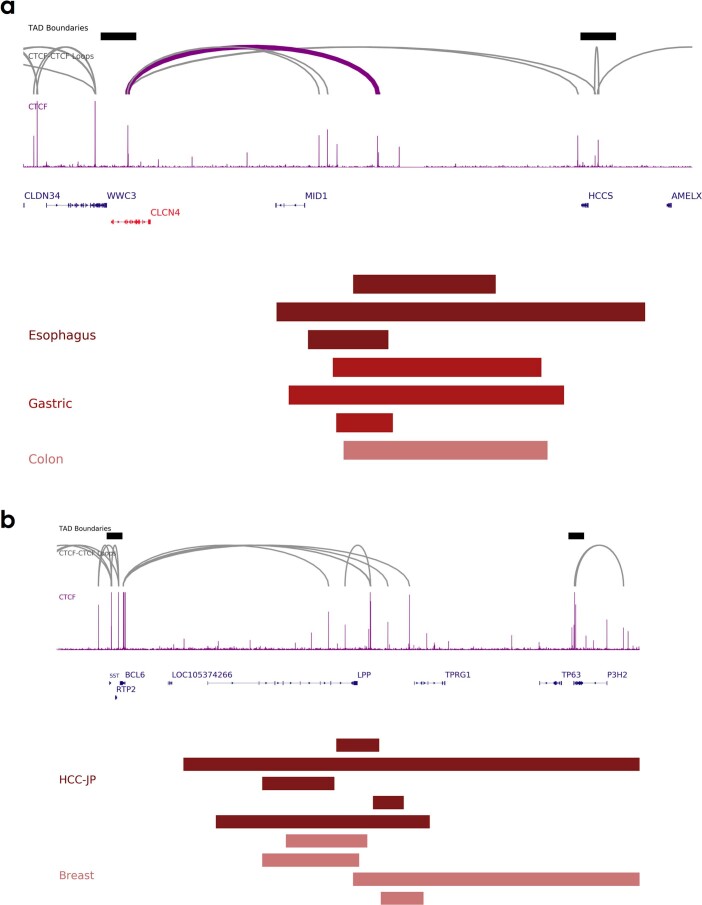

Extended Data Fig. 6. Examples of genomic alterations that potentially affect CTCF-CTCF chromatin folding loops.

a-b, Potentially affected insulated neighborhoods a, in esophageal, gastric and colon adenocarcinoma samples near to the CLCN4 gene and b, in liver-HCC and breast cancers near to BCL6 gene. Black boxes show TAD boundaries, arcs represent CTCF ChIA-PET loops observed in three different cell types (gray). CTCF ChIP-Seq (from NHEK cell line) signal is represented by purple histogram. Red vertical bars depict deletions in individual samples.

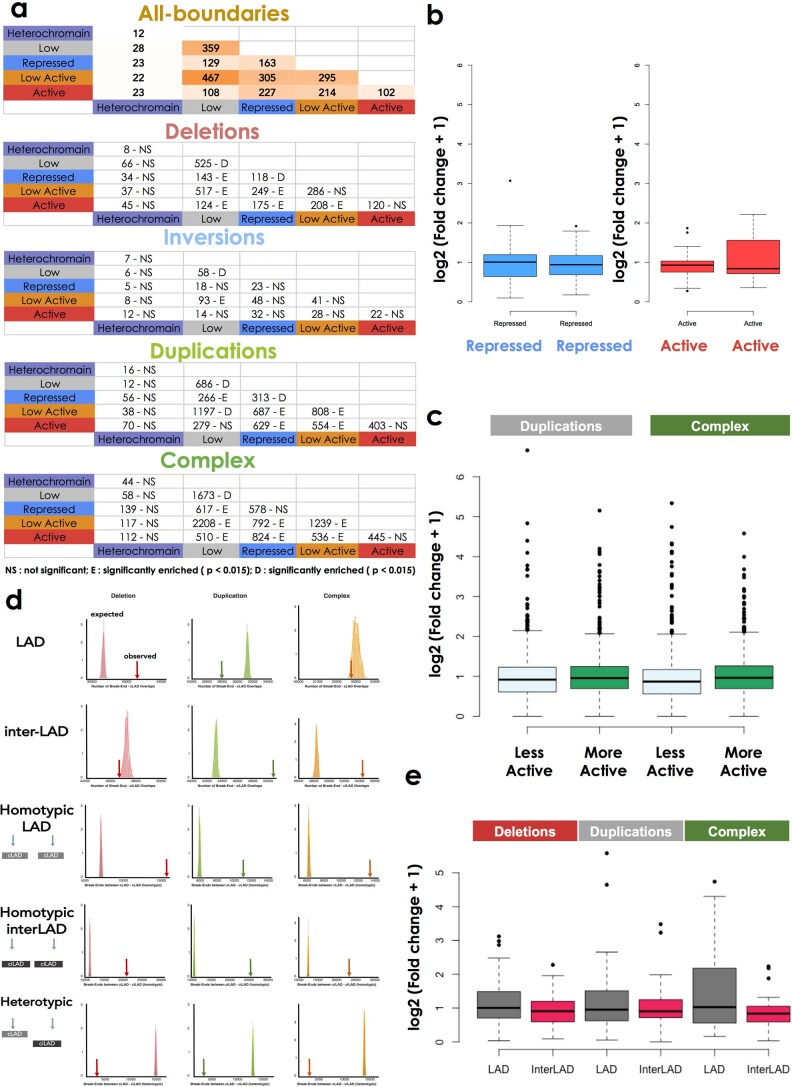

Most domain disruptions do not result in marked gene-expression changes

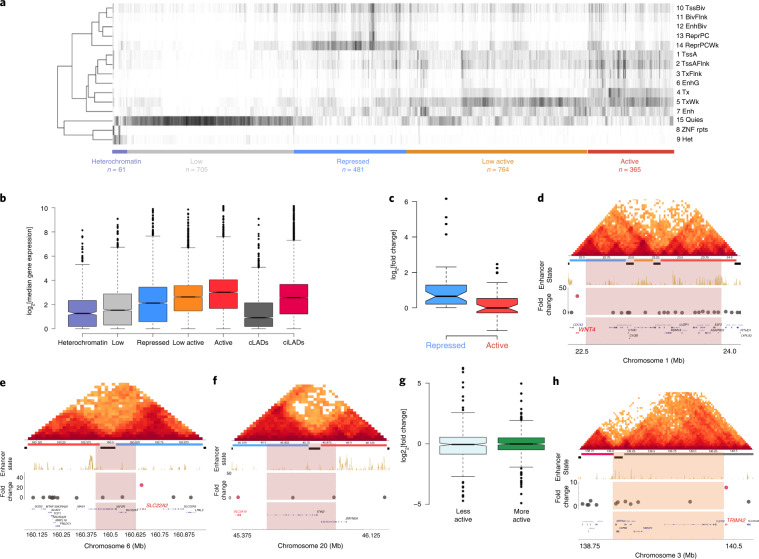

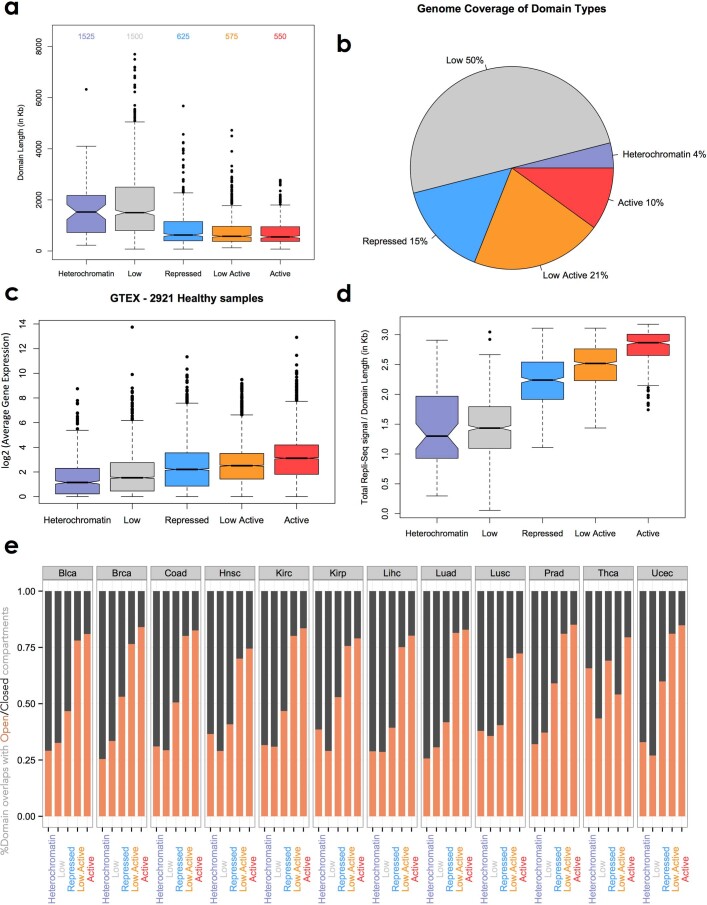

To ascribe potential functional effects of BA-SVs on chromatin domains, we annotated the TADs by profiling the context of aggregate chromatin states within each TAD. We used a probabilistic approach that calculated the occurrence of chromatin states in cell types recorded in the Roadmap Epigenome data. Coverage of 15 chromatin state enrichments in each domain was calculated and normalized to the length of the domain. The obtained matrix was grouped using the k-means clustering approach and five distinct groups of TADs were identified similar to a previous classification of chromatin domains17,19,33. These groups comprised heterochromatin (61), low/quiescent (705), repressed (481), low-active (764) and active (365) domains (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table 4). In addition, we used constitutive LADs34 identified in three different human cell types to profile the outcomes of the SVs that occurred between LADs and inter-LADs. We evaluated the annotation results by profiling the distributions of domain sizes. Repressed domains were larger in size and covered the majority of the genome compared with active domains, in agreement with previous TAD annotations19,35 (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). The median expression of genes within each domain was calculated for 2,921 cancer-free samples from 45 different tissues (GTEx consortium)36 as well as for samples from 998 patients with cancer from ICGC expression datasets. Analysis of expression levels confirmed that genes within repressed domains or LADs had significantly lower expression patterns than genes within active domains or inter-LADs (P < 2.2 × 10−16) (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 7c). Furthermore, distributions of replication timing for various cell types and open/closed chromatin compartment calls from TCGA data37 corroborated the data of the annotated domains (Extended Data Fig. 7d,e). Utilizing our domain annotations, we checked the distributions of flanking domains for BA-deletion, BA-inversion, BA-duplication or BA-complex events. The majority of the BA-SVs affected the same flanking domain types, such as boundaries that separated low and low domains or low-active and low-active domains (Extended Data Fig. 8a). However, BA-SVs between different domain types occurred significantly more frequently than the expected rate, which suggests that BA-SVs have a potential role in gene-expression changes (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Therefore, we compared expression values of the genes that reside on each side of the SVs.

Fig. 4. Most domain disruptions do not result in marked gene-expression changes.

a, Classification of TADs based on chromatin state coverage. The heat map shows domain-length normalized coverage of each chromatin state (rows) in each domain (columns). Domains are classified into five groups according to chromatin state combinations: heterochromatin (purple), low/quiescent (gray), repressed (blue), low active (orange) and active (red). b, Median expression levels (log2) in all PCAWG samples are shown for genes located in each TAD, constitutive LADs (cLADs) and inter-LADs (ciLADs). The number of genes in each annotation group: heterochromatin, 624; low, 2,874; repressed, 3,690; low active, 4,319; active: 4,578; constitutive LAD, 2,384; constitutive inter-LAD, 14,430. In these and all other box plots, the center line is the median; box limits are the upper and lower quantiles; whiskers represent 1.5× the interquartile range. c, The log2-transformed fold change in expression is shown for genes that are nearest to BA-deletion break-ends between repressed and active TADs (n = 43). d–f, Examples of BA-SV-harboring samples. Triangle heat maps represent chromatin contact frequency (log2) in NHEK cells. BA-SV regions are shaded. Colored tiles represent domains and black bars denote TAD boundaries. Roadmap Epigenome enhancer-state frequencies are shown as a yellow histogram. Dots show fold changes in expression in a lymphoma sample harboring a BA-deletion near WNT4 (d), a breast adenocarcinoma sample harboring a BA-deletion near SLC22A2 (e) and an ovarian adenocarcinoma sample harboring a BA-deletion near SLC2A10 (f). g, The log2-transformed fold change is shown for genes that are nearest to BA-deletion break-ends (n = 341). Transcriptionally less and more active refer to the ordering of domain annotations in a (that is, a low domain is considered less active than a low-active domain). h, Gene expression fold change in a melanoma sample harboring a complex SV between a LAD and an inter-LAD near TRIM42.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Classification of TADs based on the epigenetic landscape.

a, Box plots show length distributions of different TAD annotations. Heterochromatin: 61; Low: 705; Repressed: 481; Low-Active: 764; Active: 365. In these and all other boxplots in subsequent figures, the center line is the median; box limits are the upper and lower quantiles; whiskers represent 1.5x the interquartile range. b, Pie chart represents percent of mappable genome covered by each TAD annotation. c, Box plots represent median expression level (RPKM) for a gene residing in a given TAD annotation for GTEX consortia dataset. Number of genes in each annotation group: heterochromatin: 624; low: 2874; repressed: 3690; low-active: 4319; active: 4578. d, Box plots represent replication timing (Repli-Seq) values divided by domain length (in Kb) for each TAD annotations. Heterochromatin: 61; Low: 705; Repressed: 481; Low-Active: 764; Active: 365. e, Bar plots show percent of a TAD annotation covered by open (orange) or closed (black) chromatin domains calls from a previous study37 across different TCGA cancer types.

Extended Data Fig. 8. The majority of the domain disruptions do not result in drastic gene expression changes.

a, Occurrence of different SV types between domain types. Significance of the observed numbers calculated based on the expected distribution which is based on randomly shuffled boundary data, cumulative distribution of expected overlaps, z-scores were calculated based on observed number and obtained distribution from this bootstrapping exercise A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to calculate p-values. Significantly enriched (E) or depleted (D) numbers are denoted next to the numbers. b, Box plots show log2 fold-change for the genes nearest to BA-deletions between repressed-repressed (n: 19; blue; left) or active-active (n: 36; red; right) domains. In these and all other boxplots in subsequent figures, the center line is the median; box limits are the upper and lower quantiles; whiskers represent 1.5x the interquartile range. c, Box plots show log2 fold-change for the genes nearest to BA-duplication (n: 1008) and BA-complex (n: 617) break-ends on different domain types. Here ‘less’ or ‘more’ transcriptionally active refers to the ordering of domain annotations in Fig. 4a (that is a low domain is considered less compared to a repressed domain). Fold change was calculated based on the gene’s expression in the sample harboring the BA-SV compared to the rest of the samples in the same cancer type. d, Observed (arrows) and expected distribution (histograms) of SVs between constitutive LADs and interLADs. The expected distribution is based on randomly shuffled LAD and interLADs. e, Box plots show log2 fold-change for the genes nearest to deletion (n: 50), duplication (n: 66) and complex (n: 39) SVs between constitutive LAD and interLADs.

We initially focused on BA-deletions between repressed and active domains, as previous studies showed that fused repressed–active domains could lead to an upregulation of nearby genes38,39. Indeed, genes located on the repressed side of deletions were significantly upregulated (P < 0.001, Supplementary Table 5) in samples with deletions compared with the rest of the samples in the same histological subtype (Fig. 4c), whereas the same effect was not observed for BA-deletions between repressed–repressed or active–active domains (Extended Data Fig. 8b). For example, a BA-deletion in a malignant lymphoma sample was associated with a 37-fold increase in the expression level of WNT4 compared with the rest of samples from patients with lymphoma (Fig. 4d). Similarly, a BA-deletion in the genome of a patient with breast adenocarcinoma correlated with 26-fold overexpression of SLC22A2 compared with the rest of the patients with breast cancer (Fig. 4e). However, this correlation of gene expression with BA-deletions between active and repressed domains was not universal. The fold change in expression of SLC2A10 was 1.10 in a uterus adenocarcinoma sample with a BA-deletion compared with the rest of uterus tumor samples (Fig. 4f). Therefore, not every BA-deletion correlated with a marked change in gene expression; in fact, only 25% of BA-deletions between repressed and active domains coincided with twofold changes in gene expression (Supplementary Table 5). To use a higher number of events, we next extended our analysis to all BA-deletions that occurred between different domain types. We classified domains as ‘more’ or ‘less’ transcriptionally active based on the annotations of domains (the ordering of domain types is described in Fig. 4a). This analysis resulted in a non-significant (P > 0.05) difference between genes that were located on more or less transcriptionally active domains after BA-deletions (Fig. 4g); and 14% of all BA-deletions coincided with a twofold change (Supplementary Table 5). We observed a similar non-significant difference for BA-duplications and BA-complex events (Extended Data Fig. 8c, Supplementary Tables 6,7).

Next, we compared the events between LADs and inter-LADs to profile whether alterations in the lamin organization could contribute to gene expression in tumor samples. We observed that deletions significantly occurred in LADs and duplications in inter-LADs, whereas SVs were less likely to occur between LADs and inter-LADs (Extended Data Fig. 8d). We noticed certain correlations between gene expression and events between LADs and inter-LADs—for example, a complex rearrangement in a melanoma sample coincided with a sevenfold upregulation of TRIM42 (which resides in a LAD) compared with the rest of the patients with melanoma (Fig. 4h). Overall, however, we did not observe a significant change for deletion, duplication and complex events between LADs and inter-LADs (Extended Data Fig. 8e, Supplementary Tables 8–10). These observations suggest that gene regulation in cancer genomes is multifactorial, although disruptions in chromatin folding domains may contribute to expression levels in certain cases, the effects of disruption do not always coincide with the expression changes.

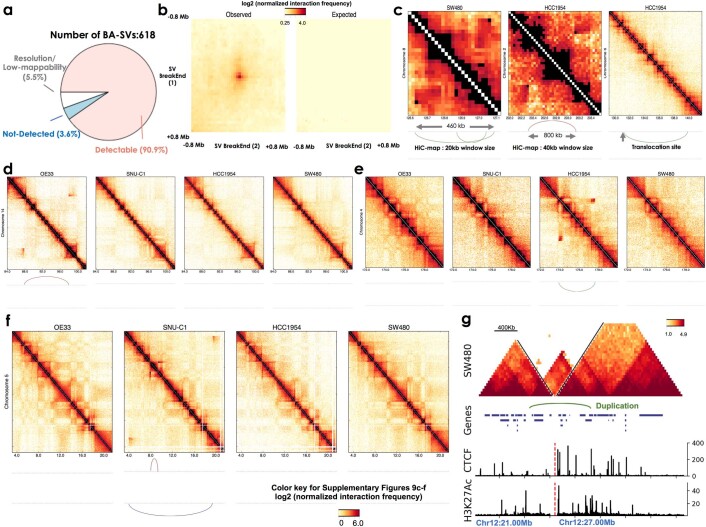

Cell-type-specific alterations in chromatin folding patterns by different SV types

Next, to evaluate whether BA-SVs indeed altered chromatin folding patterns, we generated high-resolution Hi-C data for four cancer cell lines (SW480 and SNU-C1 for colorectal adenocarcinoma, HCC1954 for breast adenocarcinoma and OE33 for esophageal adenocarcinoma), which were previously profiled by WGS. For the majority of the BA-SVs detected by the WGS data (>90%), we were able to observe a change in the folding pattern in Hi-C contact maps of the respective cell line (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Break-ends of BA-SVs exhibited a strong contact frequency (14.6-fold) in cancer cells compared with non-cancerous cells (Extended Data Fig. 9b). The shortest BA-event with a detectable change in our Hi-C maps was a 460-kb long duplication in SW480 cells (Extended Data Fig. 9c). By contrast, we observed several discrepancies between SVs detected in WGS data and Hi-C maps. These SV break-ends tended to be located in repetitive regions of the genome or overlapped with inter-chromosomal translocations (Extended Data Fig. 9a,c). Our results demonstrate that BA-SVs detected using WGS data generally result in altered chromatin folding patterns in cancer cells.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Cell-type specific alterations of chromatin folding patterns by different structural variation types.

a, Pie chart represents the ratio of BA-SVs with detectable changes in Hi-C data from HCC1954, OE33, SNU-C1, SW480 cell lines. b, Average contact enrichment between break-ends of BA-SVs in cancerous and non-cancerous cell. Interactions between break-ends of BA-SVs longer than 1 Mb in length were included in this analysis. Breast epithelial cell line (HMEC) Hi-C data was used to represent non-cancerous cell interaction profile as the majority of BA-SVs in this analysis (56.3%) was detected in breast adenocarcinoma cell line (HCC1954). c, Examples of shortest BA-SVs with detectable changes in Hi-C maps and an SV with no detectable changes in Hi-C maps. Contact frequencies (log2) of each cell type, plotted with a 20KB (SW480) and 40Kb (HCC1954) window size. Arcs below represent SV breakpoint locations with rearrangements coded by color. Green: tandem duplication; red: deletion; cyan and purple: inversion. (Left) an 460Kb long duplication in SW480 cells; (middle) an 800 kb long deletion in HCC1954 cells; (right) a duplication overlapping with a translocation in HCC1954 cells resulted in no apparent contact map change. d-f) Represented regions for the effects of ‘simple’ genomic rearrangements on chromatin folding domains: d, A deletion on chromosome 4 in OE33 cells; e, A duplication on chromosome 14 in HCC1954 cells; f, A large inversion and a small deletion on chromosome 8 in SNU-C1 cells. g, A duplication (green arc) in SW480 cells results in a TAD-like formation on chromosome 4. Below histograms show CTCF and H3K27AC ChIP-Seq data from NHEK and SW480 cell lines, respectively. Red dashed line denotes the location of distinct genomic regions.

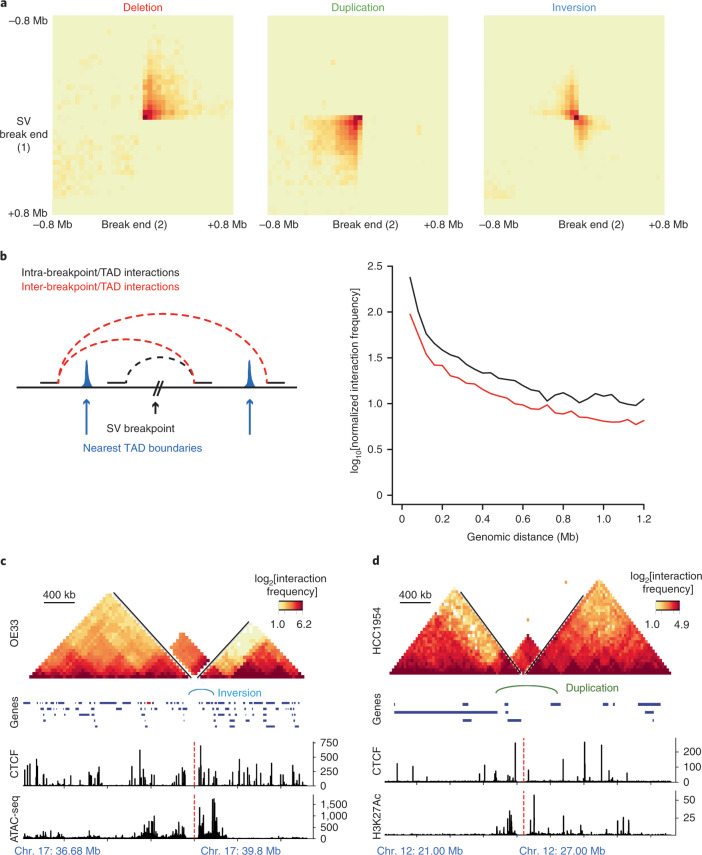

We subsequently studied how BA-deletions, BA-inversions, BA-duplications and BA-complex rearrangements change the contact maps and noticed distinct interaction patterns in chromatin contact maps for different BA-SVs (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 9d–f). This observation of specific changes in Hi-C maps due to different SV types is consistent with findings from a recent study40. Furthermore, it has also been suggested that SVs could lead to TAD fusions40 (also referred to as neo-TADs3,4); we therefore analyzed whether the BA-SVs observed in our cancer cell lines exhibited similar neo-TAD formation. We grouped bins on the basis of their location compared with the SV breakpoints and the nearest TAD boundary. If bins were between the SV breakpoints and the nearest TAD boundary, we classified these interactions as intra-TAD/SV and if bins were not constrained by the nearest boundary, we classified these interactions as inter-TAD/SV (Fig. 5b). Our analysis revealed that intra-TAD/SV interactions were stronger than the inter-TAD/SV interactions, when controlling for genomic distance effects, which suggests that the SVs can lead to cross-boundary interactions and potentially the formation of new chromatin folding domains based on the location of existing nearby TAD boundaries (Fig. 5b). For instance, an inversion in OE33 cells that encompassed ERBB2 formed a neo-TAD on chromosome 17 (Fig. 5c), a duplication in HCC1954 cells on chromosome 4 (Fig. 5c) and a duplication near KRAS in SW480 cells (Extended Data Fig. 9g) resulted in a TAD-like configuration between previously disparate two TADs (Fig. 5c). These new TAD-like patterns could only be observed in cell lines that had the SV, suggesting that these folding patterns were the result of a specific alteration (Extended Data Fig. 10a). In all of these events, we observed that new interactions spanned the nearest boundary and formed ‘triangular shapes’ that were consistent with the TAD patterns observed in non-rearranged genomes. Therefore, BA-SVs have the potential to form new TAD structures in cancer cells that could reconfigure cis-regulatory interactions.

Fig. 5. Cell-type-specific alterations in chromatin folding patterns associated with different SV types.

a, Average contact enrichment between break-ends of BA-SV events in cancer cell lines. b, TAD-fusion analysis. The schematic shows the classification of interactions based on the nearest TAD boundary. Interactions between SV breakpoint and the nearest TAD boundary are classified as intra-TAD/SV (black dashed line) and interactions that are not constrained by the nearest boundary are classified as inter-TAD/SV (red dashed line). The decay plot shows how the interaction frequency changes as a function of genomic distance. c, d, Examples of neo-TAD formations by SVs in cancer genomes. Contact frequencies (log2) of each cell type, plotted with a 40-kb window size. Bottom arcs represent SV breakpoint locations with rearrangements coded by color. Green, tandem duplication; red, deletion; cyan and purple, inversion. Histograms show CTCF ChIP–seq data from NHEK, ATAC-seq data from OE33 and H3K27ac ChIP–seq data from HCC1954 cell lines. Red lines (dashed) denote the locations of distinct genomic regions. c, An inversion (blue arc) in OE33 cells led to a TAD fusion around ERBB2. d, A duplication (green arc) in HCC1954 cells resulted in a TAD-like formation on chromosome 4.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Specificity and reproducibility of chromatin organization alterations in cancer cell lines.

a, Hi-C data around the neoTAD regions demonstrated in Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig 10g in all cell lines. b, A smaller window of chromosome 15 represented in Fig. 5d which depicts a massive chromothripsis event covering all of the chromosome15 in SNU-C1 cell line. c, Biological reproducibility of SV’s effect on chromatin folding patterns represented for each Hi-C replicates of cell lines. Contact frequencies (log2) of each cell type, plotted with a 40Kb window size. Arcs below represent SV breakpoint locations with rearrangements coded by color. Green: tandem duplication; red: deletion; cyan and purple: inversion.

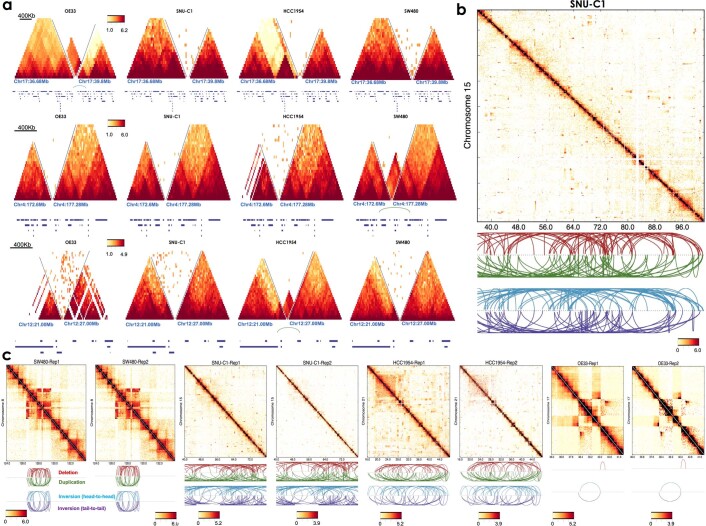

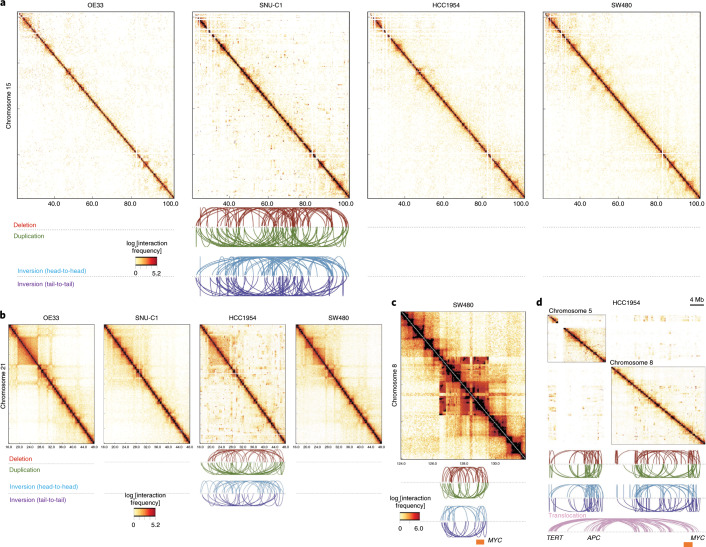

Complex rearrangements markedly change chromatin folding maps in the cancer genomes

We noticed that complex rearrangements in which deletion, inversion or duplication break-ends overlapped resulted in marked changes in Hi-C maps. SNU-C1 cells contain a complex rearrangement (chromothripsis) across the entire chromosome 15, which was reported by WGS and spectral karyotyping41. This chromosome has 239 rearrangements in the SNU-C1 cells and we observed marked changes only in SNU-C1 Hi-C maps in which the differences in folding patterns overlapped with the identified SV break-ends (Fig. 6a, Extended Data Fig. 10b). Similarly, we noticed a chromothripsis-like event that covered chromosome 21 of HCC1954 cells in WGS data and, similarly, the Hi-C map of chromosome 21 in HCC1954 cells showed considerable changes (Fig. 6b). In addition to the complex rearrangements that covered whole chromosomes, we noticed regional complex rearrangements that had abnormal chromatin folding patterns. For example, the MYC locus in SW480 cells contains 135 rearrangements in a 4-Mb genomic window (Fig. 6c), whereas a larger complex event was observed in HCC1954 cells around the similar locus, which also involved two other cancer driver genes, TERT and APC, on chromosome 5 (Fig. 6d). We could detect the changes in biological Hi-C replicates, suggesting that these BA-SV effects are reproducible (Extended Data Fig. 10c). Given that complex rearrangements are the most frequent genomic alterations observed in the cancer genomes (Fig. 1b), studying the causes and consequences of these events using the chromatin conformation-based datasets would be critical for our understanding of the contribution of these events to the formation of cancer.

Fig. 6. Complex rearrangements markedly change chromatin folding maps in the cancer genomes.

a–d, The effects of complex rearrangements on chromatin folding domains. Contact frequencies (log2) of each cell type, plotted with a 40-kb window size. Bottom arcs represent SV breakpoint locations with rearrangements coded by color. Green, tandem duplication; red, deletion; cyan and purple, inversion. a, SNU-C1 cells harbor a chromothripsis event that affects chromosome 15. b, HCC1954 cells contain a complex rearrangement on chromosome 21. c, The MYC locus contains regional complex rearrangements in SW480 cells. d, A complex rearrangement that involves TERT, APC and MYC changes interactions between chromosome 5 and 8 in HCC1954 cells. Purple arcs represent inter-chromosomal translocations.

Discussion

We explored the distributions of somatic SVs in a variety of tumor types and their potential roles in the disruption of chromatin folding and gene regulation. We found that certain boundaries are affected in a cancer-specific manner, which was likely due to the distribution of cancer-specific driver genes. Additionally, we observed a difference between the disruptions between different SV types; deletions tended to occur within TADs and LADs, whereas duplications tended to span TADs and generally occurred within inter-LAD regions. These results suggest that mechanistic differences may underlie the generation of different types of SV. For example, genome organization may influence partner selection during genomic rearrangements, as suggested by the distribution of different SV types in the genome to varying degrees. Disruption of folding domains could result in aberrant interactions between flanking domains and potentially contribute to the re-shaping of gene expression around the affected regions. Notably, we did not observe a strong association between global changes in gene expression after the disruption of each TAD, and only 14% of overall cases resulted in upregulation of more than twofold, which is consistent with the findings of recent studies42,43. These low expression changes may be reminiscent of mutations, in which there is a subset of chromatin-scale events that may be more likely to have functional effects (drivers) among a backdrop of considerable passenger events. Although we compared expression patterns of tumors in this study, cancer genomes may have other alterations that could affect the observed gene expression patterns, including copy-number alterations, dysregulation of transcription factors, chromatin regulators or cis-regulatory elements44. Therefore, the availability of histology-specific matched control samples coupled with WGS and chromatin organization datasets will augment our understanding of the functions of SV in genome folding and transcriptional dysregulation in cancers and contribute to our ability to discern signal from noise in appropriate contexts.

Methods

Hi-C data analysis

Chromatin conformation assay (Hi-C) data for cell lines of GM12878, HUVEC, IMR90, HMEC, NHEK and K562 were downloaded from GEO (GSE63525). Intra-chromosomal 25-kb-resolution raw observed, MAPQGE30-filtered values were normalized by dividing by the multiplication of Knight and Ruiz normalization scores for two contacting loci. We calculated the TAD signal by moving a window across the Hi-C matrix diagonal, the sum of the interaction for a given bin of up to 2-Mb flanking regions and log2 of the observed bin to the mean of interaction values within the given 2-Mb window. To identify TAD boundaries, we used an approach that is based on insulation score calculation18, and called TAD boundaries for each chromosome of each cell line with the following parameters: ‘-is 1000000 -ids 200000 -im mean -bmoe 1 -nt 0.1 --v’.

To calculate the significance of overlap between different TAD boundary calls, we converted the boundary regions into binary bins per genome to compare the overlap between previously published IMR90 TAD boundaries4 with our IMR90 boundary calls. We performed logical AND operation, in which the region is counted as overlapping boundaries between two datasets if only two bins for the same genomic location of each condition are 1. We used bootstrapping to determine the distribution of the random overlap numbers between two calls, and calculated P values based on the observed number and distribution of the shuffled boundaries. Shuffled boundaries are generated by randomly assigning boundaries while keeping the number of boundaries per chromosome constant. Obtained shuffled boundaries were also converted to binary string and the same logical AND operation was applied. Shuffling was performed 10,000 times for a given boundary set. This procedure is applied in the rest of our study to generate shuffled boundaries. Next, we computed cumulative distribution of expected overlaps, z-scores were calculated based on the observed number and obtained distribution from bootstrapping. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to calculate P values.

Common TAD boundaries were identified for boundaries of all five cell-types (GM12878, HUVEC, IMR90, HMEC and NHEK) that occurred within two Hi-C bins or 50 kb in genomic range. The same bootstrapping method (described above) was applied to calculate the significance of the overlap between common boundaries with TAD boundaries from the cancer cell lines K562 and MCF7.

To cluster individual TADs (defined as genomic regions between two adjacent common boundaries) based on epigenetic modifications, we used a comprehensive epigenome-profiling dataset from various human cell types. To this end, we used an entropy-based approach (epilogos) to calculate the occurrence of each chromatin state enrichment for a given genomic region across all cell types profiled by Roadmap Epigenome Consortia (http://compbio.mit.edu/epilogos/). We calculated the ratio of a TAD genomic space covered by each chromatin state, divided by the length of the TAD, and generated a normalized matrix in which columns are TADs and rows are each chromatin state, which have been extensively studied by the Roadmap Epigenome Consortia21. We applied hierarchical clustering to rows to identify similar chromatin states and k-means clustering to columns to group TADs that contain similar epigenetic modifications. We performed k-means clustering with k = 2–8 clusters and decided on k = 5 clusters as previous chromatin studies17,19 have used 5 distinct epigenetically modified chromosomal domains and k = 5 corresponded to better visually discernible domains. To determine how our TAD clustering correlate with gene expression in cancer-free and cancerous tissues, we downloaded normalized gene expression values for 2,663 different cancer-free samples from the GTEx Portal36 (v.1.6) and used normalized gene-expression values for ICGC cancer samples. We plotted the median expression of the genes in GTEx and ICGC samples, located in each domain type. Expression differences between heterochromatin and repressed domain expression with active domain expression were tested with one-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test. We also calculated the total number of genomic regions covered by each domain type. Finally, identified open and closed chromatin compartments (at a 100-kb resolution) in cancer samples using DNA methylation levels were identified as described previously37. We determined the percentage of our domain calls covered with open and closed chromatin calls from available cancer types.

We used HiCPlotter45 to plot Hi-C data with different features, TAD boundaries or gene-expression fold changes after deletion between repressed and active domains.

ENCODE and Roadmap data

ENCODE replication timing data were downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser ENCODE portal for the following cell types: BJ, GM06990, GM12801, GM12812, GM12813, GM12878, HeLa-S3, HepG2, HUVEC, IMR-90, K-562, MCF-7, NHEK and SK-N-SH. Replication timing values for smoothed wavelength transformed data were binned into 25-kb windows across the genome to discretize the data. Averages of the values in each bin across all cell types were calculated and used as average replication timing throughout the study.

We downloaded CTCF binding sites and DNase I hypersensitivity for five cell types (GM12878, HUVEC, IMR90, HMEC, NHEK) from the UCSC Genome Browser ENCODE portal. In addition, H3K9me3 and input DNA ChIP–seq alignment files (.bam) for each cell type were also downloaded. We randomly selected the same number of alignment reads for H3K9me3 and input DNA from .bam files and calculated log2-transformed enrichment levels of H3K9me3 over input DNA.

We downloaded all available CTCF peak-calling results and DNase I hypersensitivity regions from the UCSC Genome Browser ENCODE portal from 80 and 115 different cell lines, respectively (Supplementary Table 11). Occurrences of CTCF-binding and DNase I hypersensitivity sites per 25-kb window across the genome were calculated for all downloaded cell types and used to calculate TAD boundary and shuffled boundary enrichments.

Structural alterations

Somatic and germline variant calls, mutational signatures, subclonal reconstructions, transcript abundance, splice calls and other core data generated by the ICGC/TCGA PCAWG Consortium are described by the lead paper22 of the PCAWG Consortium and available for download at https://dcc.icgc.org/releases/PCAWG. Additional information on accessing the data, including raw read files, can be found at https://docs.icgc.org/pcawg/data/. In accordance with the data access policies of the ICGC and TCGA projects, most molecular, clinical and specimen data are in an open tier that does not require access approval. To access potentially identifying information, such as germline alleles and underlying sequencing data, researchers will need to apply to the TCGA Data Access Committee (DAC) via dbGaP (https://dbgap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/aa/wga.cgi?page=login) for access to the TCGA portion of the dataset, and to the ICGC Data Access Compliance Office (DACO; http://icgc.org/daco) for the ICGC portion. In addition, to access somatic SNVs derived from TCGA donors, researchers will need to obtain dbGaP authorization.

We obtained the consensus SV calls and annotations of each variation (deletions, inversions, duplications and complex rearrangements), which can be found at Synapse (https://www.synapse.org/) with accession number syn7596712. The SV classification algorithm is comprehensively defined in another study23. The code for the classification algorithm is available on GitHub (https://github.com/cancerit/ClusterSV/). In brief, this algorithm clusters individual SV junctions into SV events that may involve multiple junctions. The single junction events were interpreted, as the ‘basic’ SV types (deletion, tandem duplication, translocation and inversions). However, in many cases events involving multiple SV junctions were detected. The SV events that involved many SV junctions could not be classified into any simple SV types. Therefore, these SV events were classified as complex. We specifically focused on the events that occurred within a chromosome in this study; we therefore did not use the translocation event calls between different chromosomes. To understand the effects of SVs, we first grouped the deletions, inversions or duplications on the basis of the length of the SVs.

Short-range SVs were identified as events with a length of less than 2 Mb and we mainly focused on these events in this study. BA-SVs were identified as SVs that spanned the whole length of a TAD boundary, the rest of the SVs were classified as ‘within TAD’ in Fig. 1b. To determine the distribution of random BA-SV events, we used the same bootstrapping method mentioned above, mainly generated random boundary events 10,000 times and calculated random BA-SV event distributions. The z-scores and P values were calculated on the basis of the observed number and distribution obtained from bootstrapping. In this study, we analyzed each event separately for deletion, duplication and inversion calls, albeit in a given sample these events might occur concurrently.

Long-range SVs were identified as events with a length of more than 2 Mb and we mentioned the results obtained with long-range SVs in the main text, as appropriate.

To understand the germline BA-SV occurrences, we downloaded structural alteration calls from three different studies: deletion events (total of 8,941) from WGS data of the 1000 Genomes project26; deletions (total of 7,511) and duplications (total of 7,501) from WGS data from 236 individuals representing 125 human populations27; and from a comprehensive review of deletions (total of 11,530) and duplications (total of 1,170) events from 23 different studies including 2,647 different individuals25. We noticed that the number of BA-SVs present in germline deletions and duplications was low and these events happened less than expected by chance, which was estimated using a bootstrapping method.

We next profiled short-range SVs and BA-SVs for each of the cancer studies in our ICGC dataset. To calculate the average number of SVs or BA-SVs per sample for each of the cancer studies, we divided the sum of all observed short-range SVs or BA-SVs in a given cancer type by the total number of samples in that cancer study. Observed SVs and BA-SVs across cancer studies were plotted as stacked bar charts representing deletions, inversions and duplications.

To identify the recurrently affected boundaries in each cancer study, we generated a matrix in which each column represented a sample in the cancer study and rows represented the TAD boundaries. A binary score was assigned to each row (a TAD boundary) that indicated whether that boundary was affected by BA-SV(s) in a given sample. Boundaries that were affected in more than 10% of the samples in a cancer study, are reported as recurrently affected boundaries in Supplementary Table 2. The median length of SVs per cancer type was calculated for all observed short-range SVs in each cancer type and plotted with the standard deviation of lengths. Constitutive insulated neighborhoods were obtained from Supplementary Table 8 of a previous study15 and SVs that affected only one anchor (CTCF-binding site) of an insulated neighborhood were considered as loop-disrupting SVs.

We determined flanking domain annotations of BA-SVs, by identifying the type of the nearest domain for the break-ends of each BA-SV. This analysis resulted in a half-matrix that contained the observed frequencies of pair-wise flanking domain types. We plotted the observed values for BA-SV deletions, inversions, duplications or complex rearrangements separately. To understand the genomic distribution of domain neighborhoods, we counted the flanking domains of each TAD boundary.

To profile SVs between nuclear LADs and inter-LADs, we obtained HMM state calls from three different human cell types for constitutive LADs and constitutive inter-LADs34 from GSE22428. For a filter, we used LAD calls from an independent study3. Genomic coordinates were converted to the hg19 assembly with the UCSC liftover tool. To calculate the significance of the observed overlaps between different SV types and constitutive LAD and constitutive inter-LADs, we used the same bootstrapping method, in which break-ends of each SV type were randomly shuffled on the same chromosome 10,000 times and z-scores were calculated between observed and expected values.

We identified the nearest genes to the break-ends of BA-SVs as the nearest RefSeq genes that did not overlap with the break-ends. The RefSeq gene table was downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser in May 2016. We called genes located upstream of the 5′ end of an SV upstream genes and genes located downstream of the 3′ end of an SV downstream genes for each BA-SV. Fold changes in expression for each of the upstream and downstream genes were calculated by dividing observed normalized RPKM values in the particular sample with BA-SVs, with average normalized RPKM values in the rest of the same cancer study samples. We filtered the genes with low expression values (<0.1 FPKM), as fold changes with those genes would be seemingly high for even small fluctuations. Copy-number variations could be another confounding factor for observed gene-expression fold changes. Therefore, we obtained consensus copy-number calls for the ICGC cohort based on consensus SV results. We removed cases in which copy numbers are more than four for either the upstream or the downstream genes. In addition, we removed genes that were distal to the break-ends by more than 1 Mb. Expression differences between genes that flanked different BA-SV break-ends were tested using one-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests.

We used pyvcf (https://pyvcf.readthedocs.org) to load .vcf files and pybedtools46 to perform genomic-interval analyses.

Cancer cell lines

The colon cancer cell lines (SW480, SNU-C1) and breast adenocarcinoma cancer cell line (HCC1954) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and the esophageal adenocarcinoma (OE33) cell line was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Stocks were stored in liquid nitrogen. These cell lines were authenticated by comparing SV results from previous WGS datasets from the same cancer lines.

WGS data analysis of cancer cell lines

We obtained the WGS datasets of the SW480, SNU-C1 and OE33 cell lines from previous publications41,47,48. To identify consensus SVs for SW480 and OE33 cell lines, we ran DELLY49, Lumpy50 and BRASS51 algorithms. SV breaks-ends reported by two different callers were included in this analysis. For the SNU-C1 cell line, SV calls were obtained from Supplementary Table 2 of a previous publication41, genomic coordinates were converted to the hg19 assembly using the UCSC liftover tool. HCC1954 whole-genome data were previously analyzed by the ICGC Structural Variation subgroup and we used the consensus structural alterations for this cell line.

Cancer cell line Hi-C assay and analysis

Hi-C was performed using the in situ Hi-C protocol as previously described17 using 2–5 million cells per experiment that were digested with the MboI restriction enzyme and analyzed in duplicate. Hi-C libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq 500 or a HiSeq 4000. Reads were aligned to the hg19 reference genome using BWA-MEM52 and PCR duplicates were removed using Picard. Hi-C interaction matrices were generated using in house pipelines, and matrices were normalized using the iterative correction method53. ATAC-seq data for the OE33 cell line were obtained from a previous study54 and H3K27ac ChIP–seq datasets for the HCC1954 and SW480 cell lines were obtained from Hon et al.55 and Rahnamoun et al.56, respectively.

To investigate the potential function of SVs in TAD fusions, we classified the interactions on the basis of the nearest TAD boundary. For each SV, the average interaction frequency was calculated within a 2-Mb region of the SV. This average frequency ratio was used to ‘scale’ the interactions to account for ploidy. This was done by taking the average interaction frequency over that region and dividing it by the genome-wide average (controlling for the distance between loci) over a window of identical size. Certain WGS-defined SVs do not appear to have a signal in the Hi-C data, possibly due to false-positive SV calls, and we excluded regions for which the scaling factor was less than 0.1 to remove potential false-positive calls. In addition, we truncated the default 2-Mb window if there was another SV to avoid biases introduced by complex variants.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41588-019-0564-y.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Note

Supplementary Tables 1–11

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for contributing to this study, S. Dent, Z. Coban Akdemir, E. Z. Keung, T. Gutschner, D. Spring, J. Korbel and J. Stuart for reading the manuscript, F. Scott, S. Amin, S. Seth, F. Barthel, T. Mang, X. Song and J. Zhang for discussions, all ICGC subgroup participants for generating readily accessible mutation calls and uniformly analyzed gene-expression datasets. This work was supported by a Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas award (R1205), the Welch Foundation’s Robert A. Welch Distinguished Chair Award (G-0040 to P.A.F.) and the Emerson Collective Cancer Research Fund (to K.C.A.). J.R.D. is supported by an NIH Director’s Early Independence Award (DP5OD023071). We acknowledge the contributions of the many clinical networks across ICGC and TCGA who provided samples and data to the PCAWG Consortium, and the contributions of the Technical Working Group and the Germline Working Group of the PCAWG Consortium for collation, realignment and harmonized variant calling of the cancer genomes used in this study. We thank the patients and their families for their participation in the individual ICGC and TCGA projects.

Extended data

Author contributions

K.C.A. and P.A.F. designed the study. K.C.A. and J.R.D. performed the computational analysis. V.T.L., S.C. and J.R.D. performed the Hi-C experiments on SW480, SNU-C1, HCC1954 and OE33 cell lines. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. R.B. and P.J.C. were working group or project co-leaders.

Data availability

Aligned sequencing data, as well as somatic and germline variant calls from PCAWG tumors, including SNVs, indels, copy number alterations and SVs, are available for download at https://dcc.icgc.org/releases/PCAWG. Additional information on accessing the data, including raw read files, can be found at https://docs.icgc.org/pcawg/data/. In accordance with the data-access policies of the ICGC and TCGA projects, most molecular, clinical and specimen data are in an open tier that does not require access approval. To access potentially identifying information, such as germline alleles and underlying sequencing data, researchers will need to apply to the TCGA Data Access Committee (DAC) via dbGaP (https://dbgap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/aa/wga.cgi?page=login) for access to the TCGA portion of the dataset, and to the ICGC Data Access Compliance Office (DACO; http://icgc.org/daco) for the ICGC portion. In addition, to access somatic SNVs derived from TCGA donors, researchers will also need to obtain dbGaP authorization.

We obtained the consensus SV calls and annotations of each variation (deletions, inversions, duplications and complex rearrangements), which can be found at Synapse (https://www.synapse.org/) with accession number syn7596712.

Hi-C data have been deposited at GEO under accession code GSE116694.

Code availability

The core computational pipelines used by the PCAWG Consortium for alignment, quality control and variant calling are available to the public at https://dockstore.org/search?search=pcawg under a GNU General Public License v.3.0, which allows for reuse and distribution.

Competing interests

R.B. owns equity in Ampressa Therapeutics, is the chair of the scientific advisory board of and consultant for OrigiMed, has received research funding from Bayer and Ono Pharma, and receives patent royalties from LabCorp. All other authors have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears online.

Change history

3/21/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41588-023-01318-w

Contributor Information

P. Andrew Futreal, Email: afutreal@mdanderson.org.

PCAWG Structural Variation Working Group:

Kadir C. Akdemir, Eva G. Alvarez, Adrian Baez-Ortega, Paul C. Boutros, David D. L. Bowtell, Benedikt Brors, Kathleen H. Burns, Peter J. Campbell, Kin Chan, Ken Chen, Isidro Cortés-Ciriano, Ana Dueso-Barroso, Andrew J. Dunford, Paul A. Edwards, Xavier Estivill, Dariush Etemadmoghadam, Lars Feuerbach, J. Lynn Fink, Milana Frenkel-Morgenstern, Dale W. Garsed, Mark Gerstein, Dmitry A. Gordenin, David Haan, James E. Haber, Julian M. Hess, Barbara Hutter, Marcin Imielinski, David T. W. Jones, Young Seok Ju, Marat D. Kazanov, Leszek J. Klimczak, Youngil Koh, Jan O. Korbel, Kiran Kumar, Eunjung Alice Lee, Jake June-Koo Lee, Yilong Li, Andy G. Lynch, Geoff Macintyre, Florian Markowetz, Iñigo Martincorena, Alexander Martinez-Fundichely, Matthew Meyerson, Satoru Miyano, Hidewaki Nakagawa, Fabio C. P. Navarro, Stephan Ossowski, Peter J. Park, John V. Pearson, Montserrat Puiggròs, Karsten Rippe, Nicola D. Roberts, Steven A. Roberts, Bernardo Rodriguez-Martin, Steven E. Schumacher, Ralph Scully, Mark Shackleton, Nikos Sidiropoulos, Lina Sieverling, Chip Stewart, David Torrents, Jose M. C. Tubio, Izar Villasante, Nicola Waddell, Jeremiah A. Wala, Joachim Weischenfeldt, Lixing Yang, Xiaotong Yao, Sung-Soo Yoon, Jorge Zamora, and Cheng-Zhong Zhang

PCAWG Consortium: