Abstract

The objective of this study was to determine the frequency and seasonal distributions of HBoV detections among Iranian children presenting with acute respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms and to compare infections among children with concomitant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rotavirus (RV) infections. A cross-sectional study at Mofid Children’s Hospital in Tehran, Iran, enrolled children < 3 years old presenting with either acute respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms during the period of 2017–2018. Respiratory or stool specimens collected from each group were initially tested by RT-PCR assays for RSV and RV, respectively, and all specimens were tested for HBoV by PCR assay. Clinical and demographic data were collected and statistically compared. Five hundred respiratory and stool specimens each were tested and 67 (13.4%) and 72 (14.4%) were PCR positive for HBoV, respectively. Of 128 (25.6%) respiratory specimens positive for RSV, 65% were also positive for HBoV (p = 0.019); of 169 (33.8%) stool specimens positive for RV, 62.5% were also positive for HBoV (p = 0.023). Peak circulation of all viruses was during late winter and early spring months (Jan–Mar) in gastrointestinal infections and during winter (Feb–Jan) in respiratory infections. HBoV is commonly detected among Iranian children presenting with acute respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms and is often present as co-infections with RSV and RV, respectively.

Keywords: Human bocavirus, Acute respiratory infections, Viral infections, Co-infections, Gastrointestinal infections

Introduction

Acute respiratory infection (ARI) and acute gastroenteritis (AGE) are two important causes of morbidity and mortality with a worldwide disease burden [1, 2]. Human bocavirus (HBoV) determined in 2005, in Sweden by Allander by a molecular technique in respiratory specimens of children [3]. The HBoV is a member of the genus Bocaparvovirus, subfamily Parvovirinae, and family Parvoviridae [4]. They are small non-enveloped viruses. The linear negative or positive-sense single-stranded DNA with a length of about 5.3 kb packed in an icosahedral nucleocapsid with a diameter of 25 nm [4, 5]. There were four viral species of this virus that include HBoV-1, HBoV-2, HBoV-3, and HBoV-4 [4–6]. HBoV-1 isolated mainly in respiratory samples [4]. The other HBoV subspecies were then isolated in human stool samples [4]. HBoV detected in various clinical samples, including nasopharyngeal aspirate, serum, feces, and urine [4, 5]. The average prevalence of HBoV in respiratory tract samples extended from 1.0 to 56.8% and in stool specimens from 1.3 to 63% [4, 7, 8]. The HBoV infection extension is worldwide; its transmission and infection occur throughout the year but are predominant during cold seasons as like as winter and spring months [4, 5]. A variety of symptoms and diseases described in HBoV-positive patients, such as rhinitis, pharyngitis, cough, dyspnea, wheezing, pneumonia, acute otitis media, fever, and nausea [4, 5]. The co-infection of HBoV with other viruses is very common [4, 9]. There was not any comprehensive study of HBoV infections and co-infections with other viral agents in Middle East, by notice of this issue, this paper reports a cross-sectional study involving children less than 3 years old during 2017–2018.

Materials and method

Clinical samples

The study was part of a cross-sectional study in the period 2017–2018 that involved children less than 3 years old, who admitted to Mofid Children’s Hospital in center of Iran in Tehran city. This study conducted with two pediatric patient groups (under 3 years of age) with either gastroenteritis or respiratory tract infection symptoms.

The respiratory tract infection group included 500 nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) obtained from pediatric patients who visited the hospital while presenting with respiratory tract infection symptoms, including fever, wheezing, coughing, sputum, hypoxia, dyspnea, and rhinorrhea, during the same period. Each swab was placed in sterile tubes filled with 1 ml PBS.

The second group is the gastroenteritis patients. The 500 stool samples from patients with acute gastroenteritis symptoms (include diarrhea, fever, abdominal pain, dehydration, and vomiting without bloody samples having three or more loose stools or any vomiting in 24 h) were obtained in the same period. The parents of all children asked to take part in the study and gave informed consent. The study was approved by the research and ethics committee of the hospital. The specimens were immediately transported in cold boxes (2–8 °C) to the virology laboratory at the Department of Medical Microbiology and Virology, and stored at − 70 °C until use.

Sample processing

The nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) specimens were kept at 4 °C for a most of 24 h and aliquot was stored at − 80 °C until further processing, then treated for nucleic acid extraction. The stool processing is done by making 10% stool suspension in phosphate buffer saline, followed by overtaxing at mechanical shaker for 20 min, and centrifugation at 3000g for 20 min to pellet particulate matter, the supernatant then passed through a 0.45-μm filter. The filtrate transferred in cryovials and stored at − 20 °C until use.

Acute respiratory infection and RSV detection

Initially, RSV RNA was extracted from nasopharyngeal swab samples by using high pure RNA nucleic acid kit (Roche company), followed by cDNA preparation for each specimen. The nested RT-PCR was done and the following primers were used: [G1- CCA TTC TGG CAA TGA TAA TCT C], [G2- GTT TTT TGT TTG GTA TTC TTT TGC GA], [G3- CGG CAA ACC ACA AAG TCA CAC], [G4- GGG TAC AAA GTT AAA CAC TTC]. The primers G1 and G2 were used for the first stage. Twenty-five microliter of PCR master mix containing 5 μL of the cDNA from each specimen, 12.5 of the 1 × PCR master mix, and 50 pmol of each primer (G1 and G2) were added to the master mix. The PCR was done for 40 cycles, initially for 5 min at 95 °C and finally for 5 min at 72 °C for one cycle. The primers G3 and G4 were used for the second stage. The 25 μL of PCR master mix containing 5 μL of cDNA from each sample, 12.5 of the 1 × PCR master mix, and 50 pmol of each of the G3 and G4 primers were added to the master mix. The PCR was performed for 35 cycles, initially for 5 min at 95 °C followed by 1 min at 72 °C, 1 min at 95 °C, and finally 5 min at 72 °C for one cycle. The final PCR product was 326 bp.

Acute gastrointestinal infection and Rotavirus detection

Nucleic acid was extracted from 200 μL of 10% (100 μL of stool and 900 μL of phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2) Viral RNA was extracted from 10% (w/v) stool suspension with carrier RNA using QIAamp Viral RNA mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. For detection of rotaviruses, a reverse transcription (RT)-PCR method based on amplification of a VP6 fragment was performed using the QIAGEN® One-step RT-PCR Kit. Primers VP6-3 (′5- GCTTTAAAACGAAGTCTTCAAC-3′); positions 2 to 23 of human strain Wa (accession number K02086) and VP6-4 (′5_-GGTAAA TTACCAATTCCTCCAG-3′); positions 187 to 166 of human strain Wa (accession number K02086). Mixture supplemented with each primer at a concentration of 0.6 μM was used in an RT reaction in a 50 μL (final volume) mixture, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 400 μM and 16 μL of a denatured (5 min at 99 °C) double-stranded RNA sample. The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min at 50 °C. The PCR program included a 9-min denaturation step at 95 °C and 40 cycles of amplification for 1 min at 94 °C, for 1 min at 50 °C, and for 1 min at 72 °C, followed by a final elongation step of 7 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were then electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel. The amplified products 189 bp.

Detection of HBoV in ARI and AGE

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from respiratory samples and was done by Koma Bioteck Kit (Koma Bioteck Inc., Seoul, Korea), as well as DNA was extracted from stool by using QiAamp DNA mini extraction kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR of HBoV

To screen for the HBoV genome, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using primers in the NP-1 coding region. The forward primer is 5´-GAGCTCTGTAAGTACTATTAC-3′ and reverse is 5´-CTCTGTGTTGACTGAATACAG-3′. This gene product’s length is 354 bp. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation of 5 min at 94 °C, 40 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 54 °C and 2 min at 72 °C, and a final extension of 10 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on agarose gel [10].

Statistical data processing

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, IBM, Armonk, NY). The correlations were subjected to the Pearson chi-square. A p value below 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The part of ARI with HBoV and RSV

In our 500 respiratory samples, 128 (25.6%) specimens were positive for RSV. The fever (85.9%), wheezing (50%), cough (75%), and rhinorrhea (62.5%) were major clinical symptoms in single infection by RSV. Seventy of 128 RSV-positive patients (54.6%) were in between the age group of 1- to 2-year category (P = 0.035) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features associated with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and human bocavirus (HBoV) single and co-detections among children < 3 years old with acute respiratory illnesses

| The features | RSV (n = 128) | P value | RSV-negative patients (n = 372) | HBoV (n = 67) | P value | HBoV-negative patients (n = 433) | Co-detection of RSV with HBoV (n = 44) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic features | Male | 72 (56.25%) | 0.562 | 190 (51%) | 35 (55.2%) | 0.061 | 230 (53.2%) | 21 (47.7%) | 0.061 |

| Female | 56 (43.75%) | 0.599 | 182 (49%) | 32 (47.8%) | 203 (46.8%) | 23 (52.3%) | |||

| Age 1 to 2 years | 70 (54.6%)* | 0.035 | 200 (40%) | 33 (49%) | 0.041 | 250 (57.7%) | 33 (75%)* | 0.031 | |

| Clinical features | Fever > 37.9 | 110 (85.9%)* | 0.0119 | 350 (94%) | 33 (49.2) | 0.721 | 420 (97%) | 35 (79.5%) | 0.029 |

| Wheezing | 64(50%) | 0.0119 | 200 (53.7%) | 47 (70%)* | 0.010 | 350 (80.8%) | 39 (88.6%)* | 0.002 | |

| Cough | 96 (75%)* | 0.021 | 325 (87%) | 60 (89.5%)* | 0.011 | 430 (99%) | 36 (81.8%) | 0.021 | |

| Rhinorrhea | 80 (62.5%)* | 0.031 | 290 (77.9%) | 47 (70%)* | 0.022 | 352 (82%) | 42(95.4%)* | 0.0207 | |

| Hypoxia | 35 (27.3%) | 0.721 | 125 (33.6%) | 30 (44%) | 0.659 | 110 (25.4%) | 14 (31.8%) | 0.605 | |

| Dyspnea | 25 (19.5%) | 0.719 | 80 (21.5%) | 30 (44%) | 0.632 | 85 (19.6%) | 10 (22.7%) | 0.748 | |

*Indicated to major demographic features and clinical features in each classification

Italicized items indicate meaningful statistical functions (P ≤ 0.05)

Sixty-seven out of 500 respiratory samples (13.4%) were positive of HBoV. The forty-four (65.6%) of HBoV-positive samples were in the co-detection form between HBoV and RSV. The major clinical symptoms in single infections of HBoV were cough (89.5%), wheezing (70%), and rhinorrhea (70%). There was a meaningful relation between HBoV single ARTI and cough (P = 0.011), wheezing (P = 0.010), and rhinorrhea (P = 0.022) (Table 1). The clinical signs wheezing (88.6%) and rhinorrhea (95.4%) have been worse in co-detection form compared with single forms of HBoV and RSV infection (Table 1).

The major age category in positive samples was below 1 year old in HBoV single and co-detection forms (Table 1). There was meaningful statistical significance in the HBoV respiratory infection and age under 1 year old in HBoV single (P = 0.041) and co-detection forms (P = 0.031).

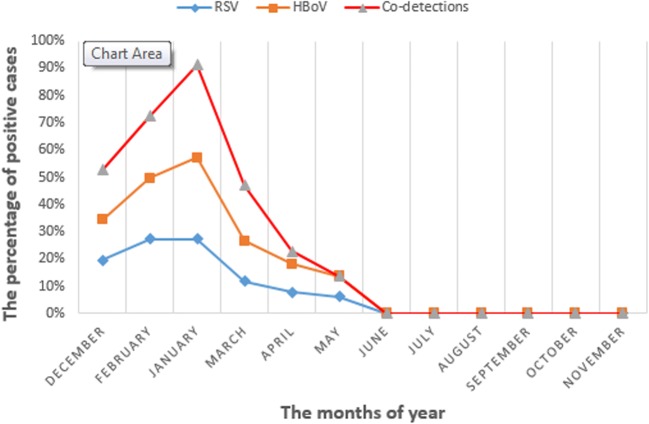

In seasonal distribution, the winter (February and January) has the highest extent outbreak at seasonal distribution in single and co-detection (Feb, 70%; Jan, 90%) of HBoV. There was meaningful statistical significance in the HBoV respiratory infection and season (P = 0.025) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The monthly distribution of HBoV and Rotavirus infections and co-detection in acute gastrointestinal infection

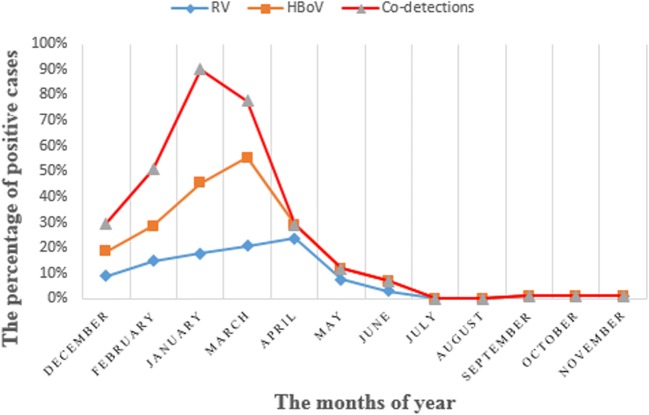

The part of AGE with HBoV and Rotavirus

Of the stool samples, 169 (33.8%) specimens were positive of Rotavirus. The fever (88.7%), diarrhea (85.7%), abdominal pain (82.8%), and vomiting (79.9%) were major clinical symptoms in single infection by Rotavirus. Seventy-one of 169 Rotavirus-positive patients (42%) were in between the age group of 1- to 2-year category (P = 0.028) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical features associated with rotavirus (RV) and human bocavirus (HBoV) single and co-detections among children < 3 years old with acute gastroenteritis

| The features | RV (n = 169) | P value | RV-negative patients (n = 331) | HBoV (n = 72) | P value | HBoV-negative patients (n = 428) | Co-detection of RV with HBoV (n = 45) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic features | Male | 89 (52.6%) | 0.612 | 190 (57.4%) | 36 (50%) | 0.061 | 230 (53.7%) | 26 (57.7) | 0.097 |

| Female | 80 (47.4%) | 0.597 | 182 (42.6%) | 36 (50%) | 203 (46.3%) | 19 (42.3%) | 0.881 | ||

| Age 1 to 2 years | 71 (42%)* | 0.0203 | 200 (60%) | 30 (41.6%) | 0.041 | 250 (58.4%) | 35 (77.7%)* | 0.031 | |

| Clinical features | Fever > 37.9 | 150 (88.7%)* | 0.0149 | 329 (99%) | 40 (55%)* | 0.821 | 420 (98%) | 36 (80%) | 0.029 |

| Diarrhea | 145 (85.7%)* | 0.0116 | 200 (60%) | 60 (83.3%)* | 0.001 | 350 (81%) | 36 (80%) | 0.002 | |

| Abdominal pain | 140 (82.8%)* | 0.0019 | 265 (80%) | 59 (81.9%)* | 0.011 | 380 (88.7%) | 36 (81.8%) | 0.021 | |

| Vomiting | 125 (79.9%)* | 0.0231 | 225 (67.9%) | 60 (83.3%)* | 0.012 | 352 (82.8%) | 44 (97.7%)* | 0.0207 | |

| Dehydration | 100 (59.1%) | 0.728 | 170 (51.3%) | 25 (34.7%) | 0.859 | 110 (25.4%) | 32 (71.1%)* | 0.0016 | |

*Indicated to major demographic features and clinical features in each classification

Italicized items indicate meaningful statistical functions (P ≤ 0.05)

Of the 500 fecal specimens, 14.4%, 72 specimens were positive for HBoV. Among the acute gastroenteritis samples, 62.5% samples from all HBoV-positive samples have co-detections with Rotavirus. Among the acute gastroenteritis, major clinical symptoms in single infections of HBoV were diarrhea (83.3%), abdominal pain (81.9%), and vomiting (83.3%). There was a meaningful relation between HBoV single AGE and diarrhea, abdominal pain, and vomiting (Table 2). The vomiting (97.7%) and dehydration (71.1%) clinical symptoms have been worse in co-detection form compared with single forms of HBoV and Rotavirus infection (Table 2).

The major age category in positive samples was in between 1 and 2 years old in HBoV single and co-detections forms with Rotavirus (Table 2). There was meaningful statistical significance in the HBoV gastrointestinal infection and age between 1 and 2 years old in HBoV single (P = 0.035) and co-detections forms (P = 0.041).

In seasonal distribution, the late winter (January) and early spring (March) have the highest extent outbreak at seasonal distribution in single infection (Jan, 45%; Mar, 50%) and co-detection (Jan, 90%; Mar, 80%) of HBoV. There was meaningful statistical significance in the HBoV gastrointestinal infection and season (P = 0.035) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The monthly distribution of HBoV and RSV infections and co-detection in acute respiratory infection

Discussion

The acute respiratory infections and acute gastrointestinal infections are major causes of mortality and morbidity in children aged under 5 years all over the world [1, 2]. Respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, and HBoV were the four most common virus detected in viral respiratory infections [1]. This study is one of comprehensive studies on HBoV infections and co-infections in Middle East and Iran within children that have acute respiratory and gastrointestinal infections. This study shows the frequency of acute respiratory and gastrointestinal HBoV infections in patients with less than a 3-year age during the spring to winter of 2017–2018.

In major reports, HBoV is the most common infectious cause and after major viruses can result in acute respiratory infection in children under 3 years old [4, 11, 12]. The major reports, one of these reports is Calvo et al.’s study, in single infections and dual infections of HBoV state that HBoV was detected in 9.9% as a distinctive pathogen and 75% as co-infections with other viral agents [13]. Just like in our report, RSV is a fundamental viral isolated agent in acute respiratory infections in children. We show in agreement with this report that HBoV co-infection with RSV was common (65.6%) in HBoV-positive patients in our study and we find a potential relation between RSV and HBoV infections. In our study, a higher frequency of HBoV in ARTI was observed in winter and between January and April with a peak in February. This issue was related to activation of HBoV in cold season beside RSV. In our report, we show that, in clinical manifestations, wheezing and rhinorrhea have been heightening at co-infection form.

In another report of Calvo et al., it was observed that HBoV and other viral agents like RSV co-infection form were 74% and the average of age was under 2 years old. They reported that in co-infection form, the clinical manifestations are equal (44–46%) [14]. Now we have been showing that the clinical manifestations are not equal in co-infection form but all symptoms were worse in dual infection form and in single forms; all of the clinical symptoms have low percentage like wheezing, rhinorrhea, and fever (Table 1).

There were few comprehensive reports of HBoV and Rotavirus single and dual infections in acute viral gastroenteritis [15–21]. In an excellent report by De R et al. about the risk of acute gastroenteritis associated with HBoV infection in children includes 36 studies all over the world [21]. In this report, the HBoV prevalence in cases with acute gastroenteritis was 6.90%. They showed the global distribution of the HBoV incidences in pediatric patients under 5 years old with acute gastroenteritis that reported from 18 countries from 2005 to 2016. In conclusion, current evidence suggests that even though HBoV may be considered as probable cause of acute gastroenteritis, in our report, the HBoV and Rotavirus accompanying are confidential evidence to HBoV major pathologic role in acute gastroenteritis in children.

In acute gastrointestinal infection by HBoV, a study in Pakistan in 2015 showed that out of all positive samples for HBoV, 98% were found to be co-infected with rotavirus [19]. Among the clinical features, fever and vomiting are the defined symptoms in 89% and 87% children, respectively. In agreement with this report, the HBoV acute gastroenteritis infection was 14.4% but co-infection form with Rotavirus was 62.5%. The clinical symptoms, vomiting, and diarrhea were 83.3% in single HBoV infection and all of the symptoms were worse in dual infection form.

One study in Albania in 2016 shows that HBoV was detected at 9.1% [18]. All HBoV-positive cases were co-infected with other enteric viral agents. Just like in our report, HBoV gastrointestinal infection was revealed in co-infection forms with rotavirus. We show in agreement with earlier studies that HBoV co-infection with Rotavirus was common (62.5%) in HBoV-positive patients in our study and we find a potential relation between Rotavirus and HBoV infections. The AGE single infections were characterized by the presence of fever, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and dehydration. Seasonal peaks of HBoV infection vary among different counties because of climate and geographic issues. Previous studies suggested that HBoV infection had a higher detection rate in winter [14, 16, 20–24]. In our study, a higher frequency of HBoV in AGE and ARTI was observed between January and April with a peak in February. Our results show that HBoV is mostly detected in respiratory samples and fecal samples of young children with ARI, in agreement with earlier reports.

Conclusions

The prevalence of respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections with HBoV occurs precisely in the age range of the respiratory and digestive diseases caused by the RSV and the RV, and that their infection also occurs within the same age and seasonal period. In conclusion, HBoV is commonly detected among Iranian children presenting with acute respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms and is often present as co-infections with RSV and RV, respectively.

Limitations

This report has limitations that we hope to solve in next reports. Reliance on PCR for determining HBoV disease association is not reliable. However, in all experiments, we used the standard commercial control of HBoV, but it was better to determine genotypes by sequencing; now because of financial restrictions in this project, this was not analyzed. Other limitation of this report is that we do not have healthy patient control group that has shown that the virus is often present in the absence of disease. A better demonstration of disease association would require a prospective study design with testing of multiple samples at different time points during disease presentation, ruling out all other pathogens (not just RSV or RV) from HBoV-positive cases, or use of serology. Moreover, limiting study of co-detections to only RSV and RV and not ruling out other potential respiratory/gastrointestinal pathogens could bias the clinical findings. There was a hypothesis that needs to be discussed in the next report and that is the coincident seasonal peaks which reflect that the detection of HBoV in feces could be due to swallowing of the virus present in respiratory secretions.

Funding information

This study was financially supported by the Pediatric Infections Research Center (PIRC), Mofd Children’s Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, IR Iran.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by two ethical committees: Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, IR Iran, Pediatric Infections Research Center, Mofid Children’s Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, IR Iran. Adult subjects or parents of the child subjects signed the consent form for participation in the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Pediatric Infections Research Center (PIRC) research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bezerra PG, Britto MC, Correia JB, Maria do Carmo M, Fonceca AM, Rose K, et al. Viral and atypical bacterial detection in acute respiratory infection in children under five years. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott EJ. Acute gastroenteritis in children. Br Med J. 2007;334(7583):35–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39036.406169.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(36):12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guido M, Tumolo MR, Verri T, Romano A, Serio F, De Giorgi M, et al. Human bocavirus: current knowledge and future challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(39):8684–8697. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i39.8684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jartti T, Hedman K, Jartti L, Ruuskanen O, Allander T, Soderlund-Venermo M. Human bocavirus-the first 5 years. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22(1):46–64. doi: 10.1002/rmv.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schildgen O. Human bocavirus: lessons learned to date. Pathogens. 2013;2(1):1–12. doi: 10.3390/pathogens2010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K, Wang W, Yan H, Ren P, Zhang J, Shen J, Deubel V. Correlation between bocavirus infection and humoral response, and co-infection with other respiratory viruses in children with acute respiratory infection. J Clin Virol. 2010;47(2):148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broccolo F, Falcone V, Esposito S, Toniolo A. Human bocaviruses: possible etiologic role in respiratory infection. J Clin Virol. 2015;72:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debiaggi M, Canducci F, Ceresola ER, Clementi M. The role of infections and coinfections with newly identified and emerging respiratory viruses in children. Virol J. 2012;9(1):247. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdel-Moneim AS, Kamel MM, Hamed DH, Hassan SS, Soliman MS, Al-Quraishy SA, et al. A novel primer set for improved direct gene sequencing of human bocavirus genotype-1 from clinical samples. J Virol Methods. 2016;228:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao M, Zhu R, Qian Y, Deng J, Wang F, Sun Y, Dong H, Liu L, Jia L, Zhao L. Prevalence and phylogenetic analysis of human bocaviruses 1-4 in pediatric patients with various infectious diseases. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang W, Yin F, Zhou W, Yan Y, Ji W (2016) Clinical significance of different virus load of human bocavirus in patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Sci Rep 6:20246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Calvo C, García-García ML, Pozo F, Paula G, Molinero M, Calderón A, González-Esguevillas M, Casas I. Respiratory syncytial virus coinfections with rhinovirus and human bocavirus in hospitalized children. Medicine. 2015;94(42):e1788. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calvo C, Garcia-Garcia ML, Pozo F, Carballo D, Martinez-Monteserin E, Casas I. Infections and coinfections by respiratory human bocavirus during eight seasons in hospitalized children. J Med Virol. 2016;88(12):2052–2058. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JI, Chung JY, Han TH, Song MO, Hwang ES. Detection of human bocavirus in children hospitalized because of acute gastroenteritis. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(7):994–997. doi: 10.1086/521366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapoor R, Dhole TN. Human bocavirus (HBov1 and HBov2) in children with acute gastroenteritis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;2(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WA EL-M, Awadallah MG, MDA EL-F, Aboelazm AA, MS EL-M (2015) Human bocavirus among viral causes of infantile gastroenteritis. Egyptian J Med Microbiol 24(3)

- 18.G. RR, S, DL, M. I, D. D, F. C, G. X et al. Human bocavirus in children with acute gastroenteritis in Albania. J Med Virol. 2016;88(5):906–910. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alam, M. M., Khurshid, A., Shaukat, S., Sharif, S., Suleman, R. M., Angez, M., ... & Zaidi, S. S. Z. Human bocavirus in Pakistani children with gastroenteritis. J Med Virol 2015;87(4), 656–663 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Lasure N, Gopalkrishna V. Molecular epidemiology and clinical severity of human bocavirus (HBoV) 1-4 in children with acute gastroenteritis from Pune, Western Indi. J Med Virol. 2017;89(1):17–23. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De R, Liu L, Qian Y, Zhu R, Deng J, Wang F, et al. Risk of acute gastroenteritis associated with human bocavirus infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alam MM, Khurshid A, Shaukat S, Sharif S, Suleman RM, Angez M, Nisar N, Aamir UB, Naeem M, Zaidi SSZ. Human bocavirus in Pakistani children with gastroenteritis. J Med Virol. 2015;87(4):656–663. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee EJ, Kim HS, Kim HS, Kim JS, Song W, Kim M, et al. Human bocavirus in Korean children with gastroenteritis and respiratory tract infections. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:7507895. doi: 10.1155/2016/7507895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang W, Yin F, Zhou W, Yan Y, Ji W. Clinical significance of different virus load of human bocavirus in patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20246. doi: 10.1038/srep20246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]