Abstract

Brazil is the second largest ethanol producer in the world and largest using sugarcane feedstock. Bacteria contamination is one of the most important issues faced by ethanol producers that seek to increase production efficiency. Each step of production is a selection event due to the environmental and biological changes that occur. Therefore, we evaluated the influence of the selection arising from the ethanol production process on diversity and composition of bacteria. Our objectives were to test two hypotheses, (1) that species richness will decrease during the production process and (2) that lactic acid bacteria will become dominant with the advance of ethanol production. Bacterial community assemblage was accessed using 16S rRNA gene sequencing from 19 sequential samples. Temperature is of great importance in shaping microbial communities. Species richness increased between the decanter and must steps of the process. Low Simpson index values were recorded at the fermentation step, indicating a high dominance of Lactobacillus. Interactions between Lactobacillus and yeast may be impairing the efficiency of industrial ethanol production.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s42770-019-00147-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ethanolic fermentation, Sugarcane, Distillery, Selection, Microbial ecology

Introduction

Ethanol is produced in industries worldwide by the microbial fermentation of the sugars. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the main species used in ethanol industries, due to their ability of converting carbohydrates into ethanol, energy, cellular biomass, CO2, and other products [1]. Brazil is the second largest ethanol producer in the world, and has sugarcanes as the main feedstock [2]. Since 1970, the use of ethanol as fuel for automotive vehicles has increased in Brazil, and decreased in 1990s due to the reduction of subsidies aimed at ethanol industries. A new increase was recorded in the years 2000s with the advance of flex-fuel cars. Today, most cars circulating in Brazil are flex-fuel [3].

There are two types of distilleries used in ethanol production plants in Brazil, fed-batch and continuous fermentation processes [1]. At fed-batch fermentations, tanks are filled one at a time, and tank management and cleaning occur individually, as discrete events. However, in continuous fermentations, all tanks are connected in a row and the process occurs simultaneously. The sugarcane juice, after undergoing consecutive treatments steps, is used as substrate for yeast growth and ethanol production [4]. In general, ethanol production consists of cane preparation, juice extraction, juice clarification, juice evaporation, must production, fermentation using yeasts and wine production. The wine follows to other distillation steps and yeast recycling [1].

Maintaining the equipment used in ethanol production within the industry clean is very important to avoid contamination by other microorganisms. Despite the caution in avoiding contamination, it happens and is tolerated [4]. Sugarcane varieties and mixed juices produced after mill have their own associated microbiome and these microorganisms will be present in some steps of ethanol production. In addition, the soil from sugarcane roots, harvest technologies, and milling equipment are also important contamination source [1, 4]. Microbial contaminant species may interfere directly in ethanol production competing with the yeast for nutrients during the fermentation process, producing components that may be toxic to the yeast (e.g., acetic and lactic acid) [5], and reducing the carbohydrate consumption and its conversion to ethanol by the yeast. Several strategies were used by bioethanol industries for controlling the microbial contaminants such as chemicals, antibiotics, bacteriophage, and enzymes treatments [6–8]. Consequently, high costs in cleaning up the equipment arise, reducing the productivity in ethanol production [4, 5, 9, 10]. The main contaminant taxon is a Lactobacillus, specifically a lactic acid bacteria (LAB) found in high proportion during the fermentation procedure [11, 12].

Microbial communities are shaped by four main process: selection, ecological drift, dispersal, and speciation [13] (or mutation [14]). Selection is the ability of species to survive and reproduce in different habitats influenced by physical, chemical, and biotic factors. Ecological drift depicts the frequencies of species at a given location as a consequence of demographic fluctuations changes. Dispersal is the ability of species to reach and colonize a new location, and, speciation is the origin of new species by speciation events [13, 14]. We believe that the microorganism community structure in the ethanol production process will be determined by selection and ecological drift due the spatial isolation among production steps, which hinder dispersal. In addition, the time from one ethanol production stage to the next is too short for speciation to occur, even in organisms of high reproduction rates [15]. Therefore, each step of production may be considered a selection event due to the environmental and biological changes inherent to each stage. In this study, we investigated the influence of selection in diversity and composition of bacteria during ethanol production process.

Our objectives in this study were to test two hypotheses: (1) species richness will decrease during the process and (2) lactic acid bacteria will become dominant with advance of the ethanol production by selection. Bacterial community assemblage was accessed using 16S rRNA gene sequencing from 19 samples. Microbial contamination is of great importance in the ethanol plant factory and there are few studies in this area exploring the ecological and evolutionary process. This study can shed light as to how these microbial communities interact, how species succession occurs, and how these process influences in microbial contaminant diversity and composition with advancing of ethanol production.

Material and methods

Sampling and ethanol production process

Samples were aseptically collected from each step of the ethanol production process in August 2016 at the Bambuí Bioenergia SA distillery localized in rural area of Bambuí, state of Minas Gerais. We collected one sample from each production step for microbial community analysis. The temperature of each production step was determined by protocols production of distillery and was registered as categorical variable. All samples were stored at − 20 °C until further processing.

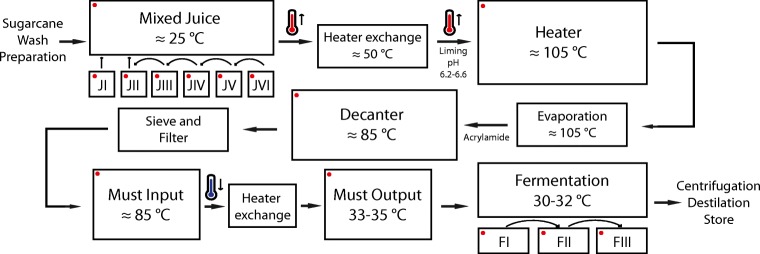

The ethanol production (Fig. 1) begins with sugarcane input, washing, preparation, and sugarcane mill. A same sugarcane sample will pass through six sequential mills (Fig. 1, JI–JVI). The sugarcane juice is stored in different tanks for each mill, and is later mixed in one tank. We collected seven samples in this stage: JuiceI, JuiceII, JuiceIII, JuiceIV, JuiceV, JuiceVI, and Mixed Juice. The mixture of those juices happened from sample JuiceVI to Juice II; first, JuiceVI was mixed with JuiceV, then that mixture was mixed with JuiveIV and subsequently, one by one, resulting in JuiceI and a mixture of Juices (II–VI). JuiceI and the previous mixture of Juices (II–VI) were then mixed resulting in the Mixed Juice (Fig. 1, Mixed Juice).

Fig. 1.

Arrangement of the main ethanol production steps. Red dots show the steps sampled

After the milling step, Mixed Juice was sent to a heat exchanger (increasing temperature up to ≈ 50 °C), where liming was conducted. The liming process was carried out to regulate the pH of the solution to 6.2–6.6. The limed juice passed through two other heater exchange processes simultaneously, reaching the temperature of ≈ 105 °C. In this stage, we collected the samples HeaterI and HeaterII.

The high-temperature mixed juice was sent to the evaporation step, where the non-condensable gases were removed from the juice and acrylamide was added as it promotes the agglomeration of flakes, increases sedimentation speed, decreases the turbidity of the clarified juice, and facilitates juice decantation. These treatments improve the efficiency of the next step—decantation. We collected four decantation samples, two before the material entered the decanter, and two after (DecanterI input, DecanterII input, DecanterI output, and DecanterII output).

After decantation, the product was sifted and filtered, and the must (juice treated and evaporated) was sent to the heat exchanger to reduce temperature from ≈ 85 °C to 33–35 °C, temperature needed for yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) growth in fermentation tanks. We collected samples before and after the must passed through the heat exchanger (MustI input, MustI output, and MustII output). We were unable to collect must samples before it entered the heat exchanger II.

The low-temperature must was transferred to the first fermentation tank which was filled with yeast solution to up to 25% of its volume capacity. The volume of the tanks is then completed with must (3–4 h), and the fermentation process takes place for the next 4–5 h. The must runs through three sequential fermentation tanks, each of which were sampled: FermentationI, FermentationII, and FermantationIII.

DNA extraction, library construction, and sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from 250 μl of homogenized juice using an E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions with adaptations. DNA was quantified by measuring the absorbance of the sample at 260 nm using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, EUA) and Qubit® dsDNA HS (High Sensitivity) Assay (Life Tecnologies).

The primer set 341F (5′- CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 785R (5′- GACTACHVGG-GTATCTAATCC-3′) [16] was used to amplify the hypervariable regions V3 and V4 of gene 16S. The Illumina adapter was used to build the 16S sequence library following the protocol provided by Illumina (Illumina, 2013). PCR mixtures contained 0.5 μM each primer, 0.7 U of Taq DNA Polimerase (Life Tecnologies, Carlbad, CA., EUA), 1X Buffer, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP, 0.3 mg/ml BSA (Bovie Serum Albumin), and 20 ng of the DNA template. 16S rDNA amplification began with a denaturation time of 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 45 s denaturing at 95 °C, 1 min primer annealing at 57 °C, 45 s extension at 72 °C, and final extension of 10 min at 72 °C. Amplifications were conducted in a Thermal cycler GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All 19 samples were sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina, Inc., USA), using 2 × 250 bp MiSeq V2 reagent kit.

Bioinformatics

We performed a bioinformatics analysis using the Brazilian Microbiome Project (BMP) pipeline [17]. BMP pipeline is a combination of the VSEARCH [18] and QIIME [19] software. The software VSEARCH was used to remove barcodes and primer sequences from a fastq file, filter sequences by length (fastq_trunclen 400) and quality (fastq_maxee 0.5), sort by abundance, and remove singletons. After that, OTU was clustered and chimeras were removed. Two files were generated through a fastq file with filtered sequences and an OTU table in .txt. We assigned the taxonomy to OTU using the uclust method in QIIME version 1.9.0 and the SILVA 16S Database (version n128) as reference sequences [20]. The OTU table file was converted to BIOM and taxonomy metadata was added. Sequences were aligned, filtered, and the phylogenetic tree constructed. Then, alpha and beta diversity were calculated using QIIME. The nucleotide sequence data reported are available in the NCBI under BioProject PRJNA508648.

Statistical analyses

The mean Observed richness, Shannon, Simpson and Equitability values were compared among sampling groups using the Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney test [21]. A heatmap was built with the 20 most abundant OTUs using Ward’s hierarchical clustering method (ward.d2) [22]. Moreover, we used a principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) to compare similarities among samples and tested differences using a permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) [23]. All analyses were carried out using the statistical software R [24] qiimer, ggplot2 [25], phyloseq [26], and vegan [27] packages.

Results

Bacterial community diversity

A total of 51.047 sequences and 222 OTU0.03 were obtained after bioinformatics analysis. The number of sequences in each sample had a high variability, ranging from 951 sequences in SugarV to 11.159 in MustII output (mean = 2.687 ± 2.338). The last step of the fermentation process had the highest richness (100 species), followed by MustI input (82), and FermentationI (67). JuiceIV was the sample with lowest richness (37). Shannon diversity index (H′) showed values between 0.865 and 2.990. Simpson and Equitability values were similar among samples, considering the similar assumptions of the analysis. Simpson values ranged from 0.288 to 0.905 and Equitability from 0.238 to 0.679 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Richness and diversity for in each step of ethanol production

| Samples | Richness (S) | Shannon (H′) | Simpson | Equitability (J′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JuiceI | 46 | 2.162 | 0.831 | 0.565 |

| JuiceII | 50 | 1.650 | 0.564 | 0.422 |

| JuiceIII | 38 | 0.865 | 0.288 | 0.238 |

| JuiceIV | 37 | 1.039 | 0.338 | 0.288 |

| JuiceV | 41 | 2.073 | 0.801 | 0.558 |

| JuiceVI | 65 | 2.510 | 0.852 | 0.601 |

| Mixed Juice | 45 | 2.165 | 0.776 | 0.569 |

| HeaterI | 44 | 2.237 | 0.798 | 0.591 |

| HeaterII | 36 | 1.744 | 0.698 | 0.487 |

| DecanterI input | 42 | 2.038 | 0.802 | 0.545 |

| DecanterII input | 58 | 1.618 | 0.715 | 0.399 |

| DecanterI output | 42 | 1.569 | 0.565 | 0.420 |

| DecanterII output | 42 | 2.258 | 0.823 | 0.604 |

| MustI input | 82 | 2.990 | 0.905 | 0.679 |

| MustI output | 63 | 2.151 | 0.800 | 0.519 |

| MustII output | 60 | 2.561 | 0.835 | 0.626 |

| FermentationI | 67 | 1.098 | 0.389 | 0.261 |

| FermentationII | 49 | 1.302 | 0.455 | 0.335 |

| FermentationIII | 100 | 1.224 | 0.428 | 0.266 |

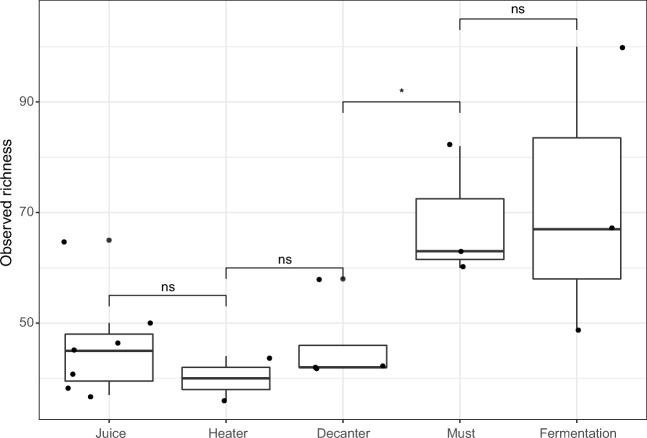

Species richness was consistent in the first three steps (juice, heater, and decantation), but we observed that richness increased in the must step, followed by a low richness increase during fermentation. Richness of the decanter and must groups differed (Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney test, p = 0.044) (Fig. 2). The diversity indices measured (Shannon, Simpson, and Equitability) exhibited similar results as regards abundance distribution among samples and groups of ethanol production steps. Diversity index values were high in the sugar, heater, evaporation, and must steps with mean values of 1.977 ± 0.546 (Shannon), 0.711 ± 0.182 (Simpson), and 0.506 ± 0.123 (Equitability). When must was transferred to the fermentation tanks, these values decreased (mean values 1.208 ± 0.102, 0.423 ± 0.033, and 0.287 ± 0.411, respectively; Suppl. Figures 1–3 for diversity indices). These differences were tested by Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney test and no significant difference was found.

Fig. 2.

Observed richness in each step of ethanol production

Bacterial community composition

The community composition of all samples was comprised mostly Firmicutes (76.43%), Proteobacteria (19.46%), and Cyanobacteria (3.71%) (Suppl. Figure 4). The Firmicutes phylum was the most abundant in several samples and the sequences from this phylum were in the Bacilli class (75.31%; Suppl. Figure 5). Over 90% of the sequences in all juice samples were Bacilli, except in JuiceI, where 53.58% of the sequences were Bacilli, 21.83% were Alphaproteobacteria (Proteobacteria) and 13.56% of Chloroplast (Cyanobacteria). Bacilli were highly dominant in heater samples (on average 94.62% of the sequences), and the mean was 81.45% in fermentation samples. The relative abundance for the decanter and must samples was a similar to that recorded for JuiceI.

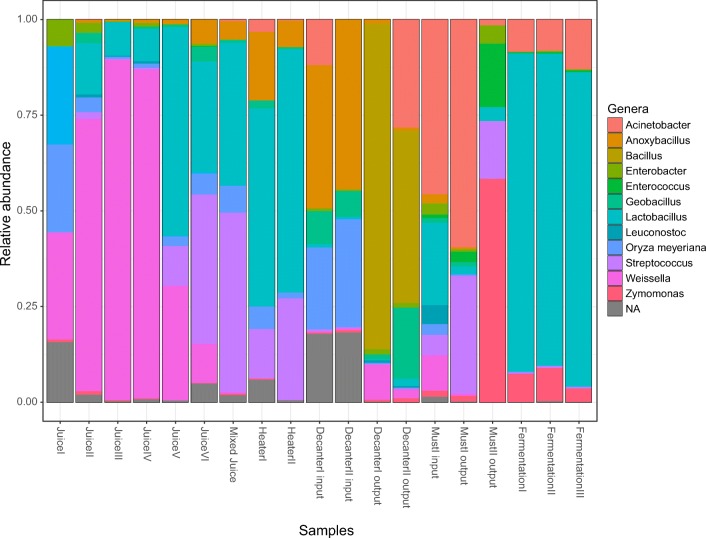

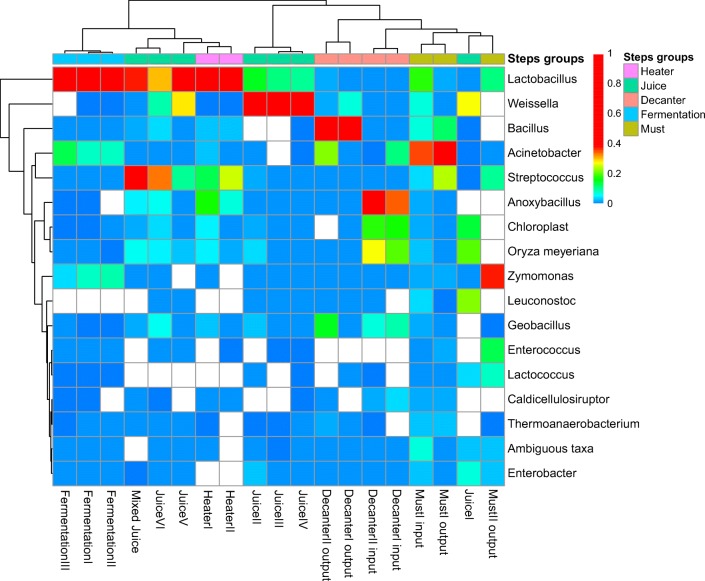

The relative abundance of taxon showed a great variability among the ethanol production steps (Fig. 3). The production steps are linear starting with sugarcane mill and juice production. The first juice obtained was JuiceI and comprised the genera Weissella (27.3%), Leuconostoc (22.01%), and Oryza mayeriana (rice; 19.67%). The abundance of Lactobacillus increased slightly from JuiceII to JuiceIV (11.65%), Weissella showed a high increase to 79.27%, and Leuconostoc a high decrease to 0.55%. JuiceV had a high abundance of Lactobacillus (55.31%), followed by Weissella (28.18%) and Streptococcus (9.57%). JuiceVI had different proportions of these genera, specifically a Lactobacillus reduction to 29.61%, Weissella reduction to 8.67%, and Streptococcus increase to 32.7%. The last step of juice production is mixing all juices in a same tank. The Mixed Juice sample had a high abundance of Streptococcus (43.54%), followed by Lactobacillus (37.34%) and a high decrease of Weissella abundance (0.37%). These patterns may also be observed in the heatmap figure (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Relative abundance of the main genera found in each step of ethanol production

Fig. 4.

Heatmap of the 20 most abundant OTUs found in each step of ethanol production

The next step of ethanol production is the heater step, in which the Mixed Juice passes through two heaters simultaneously (HeaterI and II). The Lactobacillus abundance in the juice after it passed through HeaterI was 49.55%, followed by Anoxybacillus with 17.03% and Streptococcus with 12.63%. After HeaterII, Lactobacillus abundance increased to 61.91%, Streptococcus to 24.95%, and Anoxybacillus decreased to 6.41%. The juice passed through the heaters was sent to the decantation tank for the evaporation step (two tanks). We collected samples from the decanter step before juice was directed to the tanks (DecanterI input and DecanterII input) and after the end of the evaporation process (DecanterI output and DecanterII output). DecanterI input and DecanterII input had a similar genera pattern, specifically, Anoxybacillus was the most abundant (34.38% and 42.19%, respectively), followed by Oryza meyeriana (19.64% and 28.86%, respectively). We observed a dominance of the genus Bacillus after decantation processes, comprising nearly 80% of the sequenced genes DecanterIoutput and 50% in DecanterII output. Acinetobacter and Geobacillus were also abundant in DecanterII output sample (21.48 and 14.32%, respectively).

The must produced after decantation was sent to the heat exchanger to reduced temperature to the reach optimum temperature for the yeast. The most abundant genus in MustI input was Acinetobacter (31.44%), followed by Lactobacillus (17.43%) and Streptococcus (4.06%). The pattern changed in MustI output, with an increased Acinetobacter (46.43%) and Streptococcus abundance (24.09%) and decreased Lactobacillus abundance (2.01%). MustII output is a mixture of MustI and II output, and showed a high abundance of Zymomonas (37.34%), followed by Lactobacillus (10.45%), Streptococcus (9.71%), and prominent reduction of Acinetobacter (0.95%).

The fermentation process occurs in three different and sequential tanks, FermentationI, II and III. Lactobacillus was the most abundant genus in all fermentation steps, specifically accounting for 80.39% of the sequences in FermentationI, 77.95% in FermentationII, and 79.83% in FermentationIII, followed by Acinetobacter and Zymomonas.

A principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was conducted with four distance matrices: Bray-Cutis (Fig. 5), Jaccard, and Weighted and Unweighted UniFrac (Suppl. Figure 6). The samples were sorted into five groups according to the step of production. Microbial communities present in samples from the same group, when using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix, were highly similar (PERMANOVA, F = 4.667, R2 = 0.55, p = 0.001). We observed a high proximity between samples from fermentation step (blue dots, Fig. 5). Juice samples were grouped in left side of the ordination plot (near the − 0.2 position of Axis 1), and must and decanter samples were grouped in the center.

Fig. 5.

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix for the samples of ethanol production process

Discussion

Bacterial richness increase even after selection events

Industrial ethanol production is not a sterile process, microbial contamination is common and identified as an important problem regarding ethanol production efficiency [4, 28]. We observed that bacterial richness increased, instead decreasing as we expected in our first hypothesis. In this study, each step in the ethanol production process was considered a selection event due to changes in microbial interactions and/or environmental. Bacterial richness was constant during first three steps (juice, heater, and decanter). However, richness increased from the decanter to the must steps (Fig. 2). This result may be explained by a contamination with microorganisms after the decantation process.

The increase of microbial richness after the decantation process, as observed in this study, showed that selection events that occur before decantation were efficient in controlling the input of microbial contaminants originated from sugarcane juice that is influenced by sugarcane varieties, harvest period, extraction methods, and clearing methods of equipment [4, 28]. Those samples may become contaminated during the transfer of decanted juice to must tanks, when the juice passes the rotary sieves, or during the evaporation system. Contamination at this step can be explained by a non-appropriated clearing process between productions events.

The species richness in must samples was constant during the fermentation step. However, evenness decreased in fermentation samples, as we observed in the diversity index values. Relative abundance is altered by selection, such that the environmental and biological condition may be ideal for the survival and reproduction of a species at a given time, and not at another [14]. Diversity indices based on observed richness and relative abundance, such as the Shannon, Simpson, and Equitability indexes, may be used to understand certain species and their contribution in abundance [29, 30]. However, the differences in diversity index values between the must and fermentation stages were not significant (Suppl. Figures 1–3).

Selection process shaping microbial community

The high variance of the relative abundance of OTUs among the ethanol production steps may be influenced by temperature [4] and interactions with another taxon such as competition, pH decrease, and synthesis of ethanol and organic acids [6, 28]. The importance of these variables for selection may be noted when observing the relative abundance of Weissella. Weissella exhibited a high abundance in juice samples. However, its abundance was lower in the juice mixture, possibly due to a low competitive ability with Lactobacillus and Streptococcus, decreasing Weissella relative abundance while increasing Lactobacillus and Streptococcus. The sequences rated as Weissella almost disappeared after the heater steps (Fig. 3).

All of our sequences of Weissella were rated at species level as Weissella confuse. Weissella species are non-spore and gram-positive coccobacilli [31]. W. confuse is found in fermentation foods, but have also been associated to human diseases (sepsis and bacteremia) as an opportunistic pathogen [32]. These bacteria are heterofermentative, belong to the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) group, some strain are able to growth at 45 °C and consume several types of carbohydrates (fructose, galactose, maltose) [33]. W. confuse has been found in sugarcane samples [28, 34]. The reduced abundance of Weissella may be explained by a low ability to uptake carbohydrates from the environment when compared with other lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Streptococcus. A recent study found lower abundances of Weissella in fermentation tanks [12], as recorded in this study.

On the next steps, temperature increased twice to approximately 50 °C and to 105 °C. We observed that Lactobacillus and Streptococcus were the most abundant species in heater samples, even under high temperatures. The relative abundance of Lactobacillus and Streptococcus decreased abruptly, while the abundance of Anoxybacillus and Geobacillus increased, occupying the habitat when juice samples are stored in decanter tanks, after undergoing the acrylamide treatment and being kept under constant temperature at 105 °C (decanter input samples).

Anoxybacillus and Geobacillus are gram-positive Bacillaceae family, and have the morphology of rod or coccus [35, 36]. Both are moderately thermophilic, with optimal growth temperature of 50–62 °C and 55–65 °C for Anoxybacillus and Geobacillus respectively. These genera are found in several types of habitats, for example, geothermal springs, manure, and milk-processing plants. An interesting observation about these two genera is their ability to form endospores. Geobacillus have a widespread distribution in the world, even in cold habitats [37]. Anoxybacillus spp. are alkaliphilic or alkalitolerant, but are able to grow under neutral pH [38]. The high abundance of Anoxybacillus and Geobacillus in the decantation step may be explained by their capacity of tolerating high temperatures, unlike other species. Thus, they dominated habitat due to the high temperature and absence of competitors.

The juice passed through rotary sieves and another evaporation system during the transportation of the juice from decanter to must tanks. The temperature of the decanted juice before entering must tanks ranged from 85 to 90 °C, and its microbial communities were dominated by Bacillus. This temperature reduction was enough to create conditions for Acinetobacter growth, as confirmed on the next step with a high increase of its relative abundance. Acinetobacter is gram-negative Proteobacteria and has been found in soil environments [39]. These bacteria may have come with sugarcane roots, despite the washing steps.

When the temperature of the MustI output sample was reduced to 33–35 °C, the abundance of Acinetobacter remained high, but abundance of Streptococcus began to increase. This sample was mixed with MustII output, and presented a high increase of Zymomonas abundance and decrease of Acinetobacter under mesophilic conditions. The genus Zymomonas has only one species, Zymomonas mobilis. Z. mobilis is a gram-negative Alphaproteobacteria, facultative anaerobic and rod-shaped; it can produce bioethanol by the Entner–Doudoroff pathway [40]. This species has been studied for industrial ethanol production, and it has advantages over Saccharomyces cerevisiae, such as the high ethanol tolerance [41]. The high abundance at this moment may be explained by optimal temperature conditions and the absence of other fermentative microorganisms in high abundance. Lactobacillus became dominant and Zymomonas abundance reduced to a stable proportion when must was sent to fermentation tanks and yeast was added.

We also observed a high similarity in the composition of the microbial communities within samples from the same group (Fig. 5) and significant separation among different communities. Samples from juice group had low within-group similarity values (yellow-mustard dots). However, when Mixed Juice was submitted to the first step of juice preparation (HeaterI and II), the communities present became highly similar (red dots). Therefore, microbial communities between juice and heater steps were selected by the increased temperature and pH regulation with liming. These results may be explained by the different environmental variables and inter-specific interactions present at each production step. We also observed the importance of those variables in fermentation samples (blue dots), showing high similarities among them, which may be explained by decreased temperature to mesophilic conditions, high nutrient concentration, and a consequent dominance of Lactobacillus species. Although, we do not realized microbial interaction experiments, our results are an indicative of the important role of microbial interactions during ethanol production. More studies delineated for understand those interactions such as competition assays and communication by quorum sensing [6] must be done.

High abundance of Lactobacillus during fermentation

Our second hypothesis was that lactic acid bacteria (LAB) would become dominant with the advance of ethanol production. We corroborated the hypotheses with low values of Simpson index for fermentation samples (0.26–0.33) and Lactobacillus high abundance. Other LAB, such as Weissella, showed a lower abundance and Leuconostoc was not present at this ethanol production step. Several studies have recorded Lactobacillus as dominant species during the fermentation of sugarcane juice [4, 12, 28]. Costa et al. (2015) reported that almost 100% of the sequences were of Lactobacillus species, while Bonatelli et al. (2017) reported a prevalence of 92 to 99%.

The main selection factors identified in our study during the fermentation step were temperature (30–32 °C), and the high abundance of yeast competing for carbohydrates, increasing the ethanol concentration by efficient carbohydrate fermentation [4, 11, 42, 43]. Ethanol is a toxic compound for most of the microorganisms present in sugarcane juice during fermentation [28, 44]. The other species such as Lactobacillus, Zymomonas, Acinetobacter, Enterococcus and Weissella were also resistant to ethanol, but Lactobacillus was a better competitor in carbohydrate uptake than the others, more resistant to low pH, low oxygen concentration and, ability to rapidly grow, justify their dominance at fermentation step [45].

Conclusions and remarks

Microbial communities varied greatly among the ethanol production process, with main changes occurring due to the influence of temperature. Thus, temperature was identified as an important selection factor. Our first hypothesis was rejected, in contrast with our expectations, given that species richness increased between decanter and must samples. Our second hypothesis was corroborated by the compositional data, which show a high abundance of Lactobacillus sequences in the fermentation step. However, no significant differences were recorded among the diversity indices of the production steps. The effort made to avoid contamination in ethanol industries is not enough to avoid the prevalence of Lactobacillus species during fermentation step. The identification of temperature as important selection factor and the probable moment of ethanol production that occur an input of new species in the system, contribute to understand the dynamics of microbial contaminants and design new strategies to decrease their abundances.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 1012 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bruno Spacek for critical reviews of the manuscript.

Funding information

This work was granted by Instituto Federal de Minas Gerais, Edital de Pesquisa Aplicada no. 156/2013.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lopes ML, Paulillo SC d L, Godoy A, et al. Ethanol production in Brazil: a bridge between science and industry. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amorim HV, Lopes ML, De Castro Oliveira JV, et al. Scientific challenges of bioethanol production in Brazil. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;91:1267–1275. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basso L, Basso T, Rocha S. Ethanol production in Brazil: the industrial process and its impact on yeast fermentation. Biofuel Prod - Recent Dev Prospect. 2011;1530:85–100. doi: 10.5772/959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa OYA, Souto BM, Tupinambá DD, et al. Microbial diversity in sugarcane ethanol production in a Brazilian distillery using a culture-independent method. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;42:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s10295-014-1533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bischoff KM, Liu S, Leathers TD, et al. Modeling bacterial contamination of fuel ethanol fermentation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:117–122. doi: 10.1002/bit.22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brexó RP, Sant’ Ana A d S. Microbial interactions during sugar cane must fermentation for bioethanol production: does quorum sensing play a role? Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2018;38:231–244. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2017.1332570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worley-Morse TO, Deshusses MA, Gunsch CK. Reduction of invasive bacteria in ethanol fermentations using bacteriophages. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:1544–1553. doi: 10.1002/bit.25586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muthaiyan A, Limayem A, Ricke SC. Antimicrobial strategies for limiting bacterial contaminants in fuel bioethanol fermentations. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2011;37:351–370. doi: 10.1016/J.PECS.2010.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayrock DP, Ingledew WM. Inhibition of yeast by lactic acid bacteria in continuous culture: nutrient depletion and/or acid toxicity? J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;31:362–368. doi: 10.1007/s10295-004-0156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliseu Nicula de Castro Rubens, Maria de Brito Alves Rita, Augusto Oller do Nascimento Cláudio, Giudici Reinaldo. Fuel Ethanol Production from Sugarcane. 2019. Assessment of Sugarcane-Based Ethanol Production. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucena BTL, Dos Santos BM, Moreira JLS et al (2010) Diversity of lactic acid bacteria of the bioethanol process. BMC Microbiol 10. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Bonatelli ML, Quecine MC, Silva MS, Labate CA (2017) Characterization of the contaminant bacterial communities in sugarcane first-generation industrial ethanol production. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364. 10.1093/femsle/fnx159 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Vellend M. Conceptual synthesis in community ecology. Q Rev Biol. 2010;85:183–206. doi: 10.1086/652373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson CA, Fuhrman JA, Horner-Devine MC, Martiny JBH. Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:497–506. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenski Richard E. Experimental evolution and the dynamics of adaptation and genome evolution in microbial populations. The ISME Journal. 2017;11(10):2181–2194. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e1. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pylro VS, Roesch LFW, Morais DK, et al. Data analysis for 16S microbial profiling from different benchtop sequencing platforms. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;107:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, et al. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2584. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:590–596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fay MP, Proschan MA. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney or t-test? On assumptions for hypothesis tests and multiple interpretations of decision rules. Stat Surv. 2010;4:1–39. doi: 10.1214/09-SS051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murtagh F, Legendre P. Ward ’ s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method : which algorithms implement ward ’ s criterion ? J Classif. 2014;31:274–295. doi: 10.1007/s00357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson Marti J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecology. 2001;26(1):32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.R Core Team (2019) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.Rproject.org/

- 25.Wickham H. ggplot2. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, et al (2019) vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.5–5. https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=vegan

- 28.Skinner KA, Leathers TD. Bacterial contaminants of fuel ethanol production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;31:401–408. doi: 10.1007/s10295-004-0159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill M. Diversity and evenness: a unifying notation and its consequences. Ecology. 1973;54:427–432. doi: 10.2307/1934352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haegeman B, Hamelin J, Moriarty J, et al. Robust estimation of microbial diversity in theory and in practice. ISME J. 2013;7:1092–1101. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamboj K, Vasquez A, Balada-Llasat JM. Identification and significance of Weissella species infections. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairfax MR, Lephart PR, Salimnia H. Weissella confusa: problems with identification of an opportunistic pathogen that has been found in fermented foods and proposed as a probiotic. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fusco V, Quero GM, Cho GS et al (2015) The genus Weissella: taxonomy, ecology and biotechnological potential. Front Microbiol 6. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Hammes WP, Vogel RF. The genus Lactobacillus. In: Wood BJB, Holzapfel WH, editors. The genera of lactic acid bacteria. Boston: Springer US; 1995. pp. 19–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goh Kian Mau, Gan Han Ming, Chan Kok-Gan, Chan Giek Far, Shahar Saleha, Chong Chun Shiong, Kahar Ummirul Mukminin, Chai Kian Piaw. Analysis of Anoxybacillus Genomes from the Aspects of Lifestyle Adaptations, Prophage Diversity, and Carbohydrate Metabolism. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Studholme DJ. Some (bacilli) like it hot: genomics of Geobacillus species. Microb Biotechnol. 2015;8:40–48. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeigler DR. The Geobacillus paradox: why is a thermophilic bacterial genus so prevalent on a mesophilic planet? Microbiology (United Kingdom) 2014;160:1–11. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.071696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goh KM, Kahar UM, Chai YY, et al. Recent discoveries and applications of Anoxybacillus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:1475–1488. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4663-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doughari HJ, Ndakidemi PA, Human IS, Benade S. The ecology, biology and pathogenesis of Acinetobacter spp.: an overview. Microbes Environ. 2011;26:101–112. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME10179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogers P. L., Lee K. J., Skotnicki M. L., Tribe D. E. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1982. Ethanol production by Zymomonas mobilis; pp. 37–84. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swings J, De Ley J. The biology of Zymomonas. Bacteriol Rev. 1977;41:1–46. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.41.1.1-46.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aris JP, Benner SA, Thomson JM, et al. Resurrecting ancestral alcohol dehydrogenases from yeast. Nat Genet. 2005;37:630–635. doi: 10.1038/ng1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olitta Basso Thiago, Senne de Oliveira Lino Felipe. Fuel Ethanol Production from Sugarcane. 2019. Clash of Kingdoms: How Do Bacterial Contaminants Thrive in and Interact with Yeasts during Ethanol Production? [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narendranath NV, Power R. Relationship between pH and medium dissolved solids in terms of growth and metabolism of lactobacilli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae during ethanol production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:2239–2243. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2239-2243.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Narendranath NV, Hynes SH, Thomas KC, Ingledew WM. Effects of lactobacilli on yeast-catalyzed ethanol fermentations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4158–4163. doi: 10.1128/AEM.63.11.4158-4163.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 1012 kb)