Abstract

Antioxidant drugs form one of the mainstay therapies for pain management in chronic pancreatitis. Heightened oxidative stress and free radical activity is the target for the use of antioxidant therapy in chronic pancreatitis pain relief. One of the chief components of these drugs is beta-carotene, and vitamin A. Vitamin A is a proven hepatotoxic agent which can lead to liver injury ranging from acute hepatitis to cirrhosis. Here, we present a case of chronic pancreatitis who continued antioxidant therapy unsupervised for 7 years and developed vitamin A-induced acute liver failure, which was treated with prednisolone.

Keywords: gastrointestinal system, pancreatitis, liver disease, contraindications and precautions

Background

Antioxidant drugs form one of the mainstay therapies for chronic pancreatitis. The primary aim of antioxidant micronutrient therapy in chronic pancreatitis is to supply methyl and thiol moieties for the transsulfuration pathway, which is essential for protection against reactive oxygen species-mediated electrophilic stress.1 The essential components of antioxidant drugs are methionine, organic selenium, ascorbic acid, β-carotene and α-tocopherol.2 Antioxidant use is rampant in patients with pancreatitis. A well-known hepatotoxic nutrient component of these antioxidants is vitamin A. We present a case of vitamin A-induced acute liver failure (ALF), which was treated with prednisolone. Patient education, curtailing unwarranted/unsupervised prolonged use of antioxidant therapy and regular liver function test evaluation forms an essential component in the management of chronic pancreatitis.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old teetotaller male with a body mass index of 21.5 kg/m2 presented with symptoms of excessive fatigue and nausea for 1 month without any history of fever, headache, jaundice or pain abdomen. Clinical examination was unremarkable. On further questioning, he revealed that he had a suspected attack of acute biliary pancreatitis in 2012 and underwent cholecystectomy for the same. But he continued to have recurrent abdominal pains, and imaging had revealed pancreatic divisum with features of chronic pancreatitis for which he was prescribed an antioxidant containing vitamin A 5000 IU and beta-carotene of 1 mg two times a day, which he continued for 7 years regularly without any follow-up with the treating physician. He also added that he is having dryness of skin and alopecia for 2 months.

Investigations

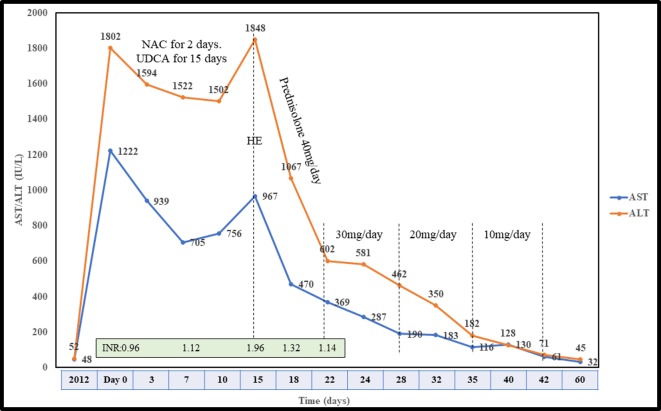

Investigations revealed serum aspartate transaminase of 1222 IU/L (normal ~5–40 IU/L) and alanine transaminase of 1802 IU/L (normal ~10–40 IU/L) (figure 1). His serum bilirubin was mildly elevated (3.2 mg/dL), but international normalised ratio (INR) (0.96), alkaline phosphatase (ALP: 119 IU/L; normal ~32–92 IU/L), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP: 49 IU/L; normal ~7–64 IU/L) and serum albumin (4.1 g/L; normal ~3.5–5.5 g/L) were normal. Hepatitis A, E IgM antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody were non-reactive. Cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus IgM antibody, HIV and Herpes simplex virus PCR were also negative. Further, autoimmune markers (antinuclear antibody, smooth-muscle autoantibody, liver-kidney microsomal autoantibody and antimitochondrial antibody) were negative, and serum IgG (1309; normal 791–1643 mg/dL) was normal. Urinary copper (12 µg/day), serum ceruloplasmin (24 mg/dL (normal 22–61 mg/dL)) and transferrin saturation (36% (normal 20%–45%)) were also normal. Ultrasonography revealed a normal liver span of 12 cm, the spleen of 10.5cm, increased echogenicity and shrunken pancreas with no evidence of choledocholithiasis. Doppler study was also normal, with the main portal vein of 12 mm showing hepatopetal flow. Eosinophils were 8% with total leucocyte count of 5.6×109/L (normal ~4–11×109/L). His platelets were 151×109/L (normal ~150–410×109/L) and Fibroscan showed a liver stiffness measurement (LSM) of 16.5 kPa and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) of 276 dB/m. There was no evidence of portal hypertension on gastroscopy.

Figure 1.

Timeline showing the transaminase levels, INR and therapy received. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; INR, international normalised ratio; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

Differential diagnosis

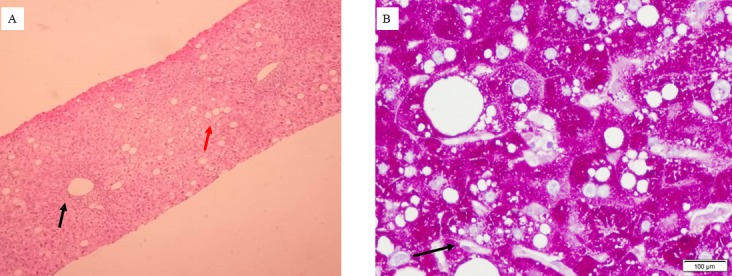

The initial differentials included were acute viral hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis as the transaminitis was high, but the required investigations were negative. As dryness of skin was also a chief complaint, overlap syndrome of primary biliary cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis was considered, but the antimitochondrial antibody was also negative, and the ALP/GGTP was also not elevated. Wilsons disease was also considered in differential diagnosis but serum ceruloplasmin and urinary copper within the normal range. Finally, the patient never had hypotension to suggest ischaemic hepatitis. Given the significant intake of antioxidant capsules for prolonged periods, drug induced liver injury was later suspected. Hence a liver biopsy was done, which showed mild periportal inflammation with microvesicular and macrovesicular steatosis. Periodic acid Schiff stain showed prominent Ito cells in the sinusoids (figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) H&E staining of liver tissue showing periportal inflammation (black arrow) and diffuse steatosis (red arrow). (B) Diastase periodic acid-Schiff stain of liver tissue showing prominent Ito cells (black arrow) with diffuse steatosis.

Treatment

He was treated with N-acetyl cysteine and ursodeoxycholic acid. Initially, a mild decline was noted in enzyme levels, which shot again at day 15. He was bought to the emergency department with symptoms of easy fatiguability, altered sleep rhythm and behaviour. His INR rose to 1.96, and his serum procalcitonin was 0.1 ng/mL (normal <0.5 ng/mL) with sterile blood, and urine culture. His arterial ammonia was 211µmol/L. Serum retinol was 178 µg/dL (normal ~10–60 µg/dL). He was offered bridging measures (plasmapheresis) and liver transplantation (although he did not fit in criteria), which was declined. He was started on antiencephalopathy measures (disaccharidase enema, L-ornithine L-aspartate infusion at 30 g/day and oral rifaximin 550 mg two times per day) and oral prednisolone of 40 mg/day. His INR normalised in 3 days with an exponential decline in transaminases at 1 week (figure 1).

Outcome and follow-up

Prednisolone was gradually tapered and stopped. He was reluctant for a repeat liver biopsy. Fibroscan showed an LSM of 7.1 kPa and CAP of 233 dB/m. He was followed up for 6 months regularly.

Discussion

Vitamin A is known hepatotoxic and can lead to liver injury ranging from chronic active hepatitis to non-cirrhotic portal hypertension to full-blown cirrhosis.3 The diagnosis is based on compatible history, elevated retinol levels and biopsy suggestive of Ito cell hypertrophy.3 Nausea and vomiting are a common symptom of chronic hypervitaminosis A.4 The cumulative dose received in our patient were vitamin A of 2.55×106 IU and beta-carotene of 5.11×103 mg with corresponding serum retinol levels of 178 µg/dL. Further, pre‐existing liver steatosis and younger age may predispose certain individuals to develop vitamin A hepatotoxicity, which may be the reason for this patient to develop ALF due to vitamin A.5 The updated Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method score was 6, suggestive of probable hepatocellular drug-induced liver injury (DILI) due to vitamin A.6 Vitamin A is a direct toxin, and it activates stellate cells via release of proinflammatory cytokines and fibrogenic products from the damaged hepatocytes.7 The high CAP value on first Fibroscan is the cause or effect in this patient is difficult to conclude as chronic vitamin A ingestion leads to lipid-laden Ito cell hypertrophy and steatosis increases the risk of liver injury to vitamin A.5 On the contrary, glucocorticoids have been shown to inhibit hepatic stellate cells via NF-κB transrepression and by repression of the profibrotic transcription factor SMAD3.8 Corticosteroids are also known to suppress the inflammatory response markedly. Fear of ALF justified us to use steroids. After an extensive workup, the cause was inconclusive, and hence the vitamin A was suspected to be the probable aetiology. There are no studies on the usage of steroids in drug-induced liver failure except in drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis. Nitrofurantoin and minocycline are notoriously known to cause drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis, which responds to a short course of steroids.9 Vitamin A-induced liver cirrhosis has been previously reported to require liver transplantation.10 Corticosteroid therapy has been proposed as a treatment for DILI in the ALF setting, but little evidence advanced to support it, and, unlike alcoholic hepatitis or autoimmune hepatitis, no controlled trials of steroid therapy for DILI have been performed.11 12 Patient education, curtailing unwarranted/unsupervised prolonged use of antioxidant therapy and regular liver function test evaluation forms an essential component in the management of pancreatitis. Whether this patient responded to steroids or the management of encephalopathy (with other supportive medicines) aided in patient’s recovery is largely speculative. Prospective studies using steroids in drug-induced liver injury may be evaluated.

Patient’s perspective.

I never knew vitamin supplements can cause my liver to fail. I request others not to take drugs on their own.

Learning points.

Vitamin A can lead to acute liver failure (ALF).

Steroids can be beneficial in drug-induced ALF.

Patient education forms an essential aspect of treating pancreatitis.

History taking forms an essential component of patient evaluation.

Footnotes

Contributors: AVK and PK made the study concept and design; image collection/graphs by AVK and PK; compilation and critical revision by AVK, RT and NPR. All members approved the final draft.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Braganza JM, Dormandy TL. Micronutrient therapy for chronic pancreatitis: rationale and impact. JOP 2010;11:99–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talukdar R, Reddy DN. Pain in chronic pancreatitis: managing beyond the pancreatic duct. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:6319 10.3748/wjg.v19.i38.6319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geubel AP, De Galocsy C, Alves N, et al. Liver damage caused by therapeutic vitamin A administration: estimate of dose-related toxicity in 41 cases. Gastroenterology 1991;100:1701–9. 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90672-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biesalski HK. Comparative assessment of the toxicology of vitamin A and retinoids in man. Toxicology 1989;57:117–61. 10.1016/0300-483X(89)90161-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stickel F, Kessebohm K, Weimann R, et al. Review of liver injury associated with dietary supplements. Liver Int 2011;31:595–605. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danan G, Teschke R. RUCAM in drug and herb induced liver injury: the update. Int J Mol Sci 2015;17:14 10.3390/ijms17010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nollevaux M-C, Guiot Y, Horsmans Y, et al. Hypervitaminosis A-induced liver fibrosis: stellate cell activation and daily dose consumption. Liver Int 2006;26:182–6. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KH, Lee JM, Zhou Y, et al. Glucocorticoids have opposing effects on liver fibrosis in hepatic stellate and immune cells. Mol Endocrinol 2016;30:905–16. 10.1210/me.2016-1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, et al. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosis. Hepatology 2010;51:2040–8. 10.1002/hep.23588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheruvattath R, Orrego M, Gautam M, et al. Vitamin A toxicity: when one a day doesn't keep the doctor away. Liver Transpl 2006;12:1888–91. 10.1002/lt.21007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu, Clinical Practice Guideline Panel: Chair:, Panel members . EASL clinical practice guidelines: drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol 2019;70:1222–61. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalasani NP, Hayashi PH, Bonkovsky HL, et al. ACG clinical guideline: the diagnosis and management of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:950–66. 10.1038/ajg.2014.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]