Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to assess the affective and cognitive risk perceptions in the general population of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) during the 2015 MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak in South Korea and the influencing factors.

Design

Serial cross-sectional design with four consecutive surveys.

Setting

Nationwide general population in South Korea.

Participants

Overall 4010 respondents (aged 19 years and over) from the general population during the MERS-CoV epidemic were included.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The main outcome measures were (1) affective risk perception, (2) cognitive risk perception, and (3) trust in the government. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify factors (demographic, socioeconomic, area and political orientation) associated with risk perceptions.

Results

Both affective and cognitive risk perceptions decreased as the MERS-CoV epidemic progressed. Proportions of affective risk perception were higher in all surveys and slowly decreased compared with cognitive risk perception over time. Females (adjusted OR (aOR) 1.72–2.00; 95% CI 1.14 to 2.86) and lower self-reported household economic status respondents were more likely to perceive the affective risk. The older the adults, the higher the affective risk perception, but the lower the cognitive risk perception compared with younger adults. The respondents who had low trust in the government had higher affective (aOR 2.19–3.11; 95 CI 1.44 to 4.67) and cognitive (aOR 3.55–5.41; 95 CI 1.44 to 9.01) risk perceptions.

Conclusions

This study suggests that even if cognitive risk perception is dissolved, affective risk perception can continue during MERS-CoV epidemic. Risk perception associating factors (ie, gender, age and self-reported household economic status) appear to be noticeably different between affective and cognitive dimensions. It also indicates that trust in the government influences affective risk perception and cognitive risk perception. There is a need for further efforts to understand the mechanism regarding the general public’s risk perception for effective risk communication.

Keywords: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, risk and perception, epidemics, surveys

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to evaluate the difference in risk perception between the affective and cognitive dimensions during Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreak in South Korea.

We used four consecutive cross-sectional surveys using nationwide representative samples.

The validity of the questionnaire used in the survey was not evaluated because of the urgency of the outbreak.

This study could not confirm causal relationship between personal characteristics and risk perception due to the limitation of the cross-sectional study design.

Background

Newly emerging contagious diseases have created a novel chance to examine how people perceive risk during an epidemic. In South Korea, since the occurrence of the index case of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) on 20 May 2015, a total of 186 persons were diagnosed with the disease, 38 of whom had died and 16 693 patients were quarantined.1 The epidemic of MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has had its largest outbreak outside of the Middle East in South Korea.2 The occurrence of multiple transmissions after the first secondary infection and the failure of the government on risk communication resulted in the increased concern of the general public.3–6 The Korean government did not disclose timely information about the outbreak of MERS-CoV, such as lists of affected medical institutions.7 Due to increased public anxiety about MERS-CoV, the trust in the Korean government had fallen and the image of the Korean president as a leader had been damaged.8 9

During contagious disease epidemics, perceived risk can have a significant impact on precautionary behaviours that might affect disease transmission.10–12 A relevant empirical study emphasised that informing public about the disease outbreak, such as the Ebola virus, could reduce worry about contracting the virus and take more preventive measures.13 The evaluation of public risk perception of disease helps us to know what knowledge the public needs. Therefore, understanding the characteristics of risk perception and factors relating to how people perceive the risk is important in terms of minimising the impact of spread of infectious disease.

Given that external stimuli are extreme events, two different reactions can occur: the affective reaction (risk as feelings) and cognitive reaction (risk as analysis).14–16 Previous studies suggest that affective reaction is quick, intuitive and automatic, while cognitive reaction is slow, deliberate and probably calculative. In the early phase of the outbreak, people may experience challenges when attempting to quantify the risk, which may lead to an affective reaction.12 17 In contrast, cognitive reaction may occur during the late stage of the epidemic.

Most people may not conduct deliberate risk analysis when they cope with lack of knowledge about risk, such as new disease outbreak, but rely on simple heuristics.18 19 Heuristic processing can be understood as simple decision rule of thumb or mental shortcut that can reduce the complexity of decision-making. When risk management decisions are needed, trust in the institutions can be used as one of the heuristics.20 People having trust in the responsible risk manager, such as the government, may perceive less risk in a particular situation than people not having trust.21 22 Regarding the MERS epidemic in South Korea, less trust in the government affected increasing number of individuals’ risk perception.23–25 Trust is known to be related to cognitive risk perception and to affective risk perception.26 27

However, when assessing the influence of trust in risk perception, many studies have not distinguished between affective and cognitive reactions regarding contagious diseases during outbreaks.3 12 23 24 28–30 We hypothesised that (1) affective risk perception would increase and decrease faster than cognitive risk perception over time and that (2) low trust in government would be related with high-risk perception (both affective and cognitive).

Methods

Participants

Between 9 June and 2 July 2015, a total of 4010 participants who were 19 years and older were monitored using a serial cross-sectional study design in four consecutive surveys, covering the MERS epidemic. All surveys were conducted using mobile (85%) or landline (15%) random digit dialling numbers in eight regions which was representative of nationwide. Samples were selected after stratification by gender, age and province. The total number of weighted cases in this survey equals the total number of unweighted cases at the national level. The weights were normalised in order to calculate proportions and ratios; however; not for estimating the number of the subtotal populations. Trained interviewers conducted all interviews using computer-assisted telephone interviewing. The first survey was conducted between 9 and 11 June 2015 after the 1 June 2015 occurrence of the first tertiary infected case. The last was conducted just 2 days before the last confirmed patient on 4 July 2015. The surveys were conducted by Gallup Korea, an affiliation of Gallup International. Details including period, number of respondents successfully interviewed and response rate for each of the four surveys are provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Details of four consecutive surveys regarding the 2015 MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea

| Survey | Period | Respondents sampled, n | Respondents successfully interviewed, n | Response rate (%) |

| 1 | 9–11 June | 5482 | 1002 | 18.3 |

| 2 | 16–18 June | 5585 | 1000 | 17.9 |

| 3 | 23–25 June | 5680 | 1004 | 17.7 |

| 4 | 30 June to 2 July | 5345 | 1004 | 18.8 |

MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Demographic factors evaluated as respondents’ characteristics included gender, age, educational attainment, occupation, self-reported household economic status, residential area, and trust in president, party identification. Age was classified into six levels (19–29, 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, 70 years and older). Educational attainment was classified into four levels (less than middle school, high school, university, graduate school or higher). Occupation was classified as either unemployed, farming/forestry/fishery, self-employed, blue-collar worker, white-collar worker, full-time home maker or student. Self-reported household economic status was classified into five levels (lower, lower middle, middle, upper middle, upper). Respondents were classified as either metropolitan or non-metropolitan residents; and distinguished by whether they resided in an area where MERS had occurred or not. Party identification was classified based on the support for the political parties. Support for the party identification was assessed based on alignment either with the ruling party (Saenuri party), with the opposition party or no opinion.

Survey instruments

The interviews were conducted based on two aspects of the risk perception, which are affective and cognitive risk perceptions (see online supplementary material). Affective risk perception was assessed using the question ‘How much worried are you that you could get MERS?’ Responses were assessed on a 4-point scale, with 4 points indicating ‘very much worried’ and 1 point indicating ‘not worried at all’ (reclassified as 1–2 points=‘not worried’; 3–4 points=‘worried’). Affective risk perception proportion was defined as the number of participants who were ‘worried’ by the number of eligible respondents. Cognitive risk perception was evaluated using the question ‘Do you think MERS epidemic will settle down in the next few days or spread further?’ and required the following responses: ‘will settle down’, ‘will spread further’. Cognitive risk perception proportion was defined as the number of participants whose response was ‘will spread further’ by the number of eligible respondents. Trust in government was assessed using presidential job approval rating. Trust in government includes expectations of government’s competence to prevent people from risk and develop and implement follow-up measures.31 This trust concept can be termed competence-based trust.32 33 We tried to assess the competence-based trust in the government using presidential job approval rating. Presidential job approval was evaluated using the question ‘Do you approve or disapprove of the way President Park Geun-hye is handling her job as president?’ and required the following responses: ‘approval’, ‘disapproval’. The development of questionnaires on risk perception and trust in the government had not gone through a validity procedure due to the urgency of the outbreak. We also imposed survey items on existing questionnaire developed by Gallup Korea, an affiliation of Gallup International.

bmjopen-2019-033026supp001.pdf (63.3KB, pdf)

Analysis

Response rates according to affective or cognitive risk perceptions were calculated over time. Univariate analyses using χ2 test were performed in the four consecutive surveys, entirely and respectively, to identify the relationships between risk perception and each demographic variable. We used multivariable logistic regression analyses to explore factors influencing risk perceptions (affective and cognitive) in the four surveys, entirely and respectively. Multivariable logistic regression model was adjusted for gender, age, educational attainment, occupation, self-reported household economic status, affected area, residential area, presidential job approval and party identification. The self-reported household economic status was excluded in survey 4 model with cognitive risk perception. These exclusions were because there was small sample size of those who perceived cognitive risk in the upper economic level in survey 4. Missing values of any variable were ≤2.7%. Using logistic regression analysis for each affective and cognitive risk perception, ‘y=1’ was used respectively when ‘worried’ in affective and when ‘spread’ in cognitive, otherwise ‘y=0’ was used.

Patient and public involvement

No patient or public was involved in the design or planning of this study.

Results

Demographic factors

The general characteristics of the participants are shown in table 2. There were no statistically significant differences between surveys except self-reported household economic status, affective risk perception and cognitive risk perception. Nearly half of the participants were female, aged <50 years, educated up to high school or below, from the affected area and showed disapproval of the president or the ruling party. Majority of the participants were employed, of middle economic status and metropolitan. More than half of participants were worried but had views that the epidemic would subside.

Table 2.

Basic characteristics of the participants

| Variables | Overall | Survey 1 | Survey 2 | Survey 3 | Survey 4 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 49.5 | 49.4 | 49.6 | 49.7 | 49.5 |

| Female | 50.5 | 50.6 | 50.4 | 50.3 | 50.5 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 19–29 | 17.6 | 18.2 | 17.1 | 17.8 | 17.3 |

| 30–39 | 18.6 | 18.2 | 18.5 | 18.8 | 19.1 |

| 40–49 | 21.7 | 20.7 | 22.5 | 21.5 | 22.1 |

| 50–59 | 19.6 | 20.0 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 19.7 |

| 60–69 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 13.1 | 11.8 | 13.1 |

| ≥70 | 9.4 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 10.8 | 8.7 |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| Middle school or below | 15.1 | 13.6 | 15.4 | 15.7 | 15.6 |

| High school | 28.1 | 27.2 | 28.9 | 27.5 | 29.0 |

| University | 50.2 | 53.9 | 48.5 | 50.0 | 48.4 |

| Graduate school | 6.6 | 5.3 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 7.0 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 8.7 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 7.8 | 9.3 |

| Farming/forestry/fishery | 3.9 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 3.6 |

| Self-employed | 15.3 | 13.6 | 14.1 | 18.7 | 14.7 |

| Blue-collar | 11.7 | 11.8 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 11.7 |

| White-collar | 28.2 | 28.9 | 26.8 | 29.1 | 28.0 |

| Home maker | 23.3 | 23.1 | 26.1 | 19.6 | 24.3 |

| Student | 9.1 | 10.1 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 8.4 |

| Self-reported household economic status* | |||||

| Upper | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.2 |

| Upper middle | 10.9 | 13.0 | 11.4 | 8.5 | 10.8 |

| Middle | 42.8 | 44.5 | 43.0 | 39.3 | 44.5 |

| Lower middle | 25.7 | 24.2 | 26.6 | 27.5 | 24.6 |

| Lower | 18.8 | 16.4 | 17.1 | 22.6 | 18.9 |

| MERS-CoV-affected area | |||||

| Non-affected area | 48.8 | 47.6 | 49.5 | 49.0 | 49.0 |

| Affected area | 51.2 | 52.4 | 50.5 | 51.0 | 51.0 |

| Residential area | |||||

| Non-metropolitan | 29.3 | 28.4 | 28.4 | 29.2 | 31.0 |

| Metropolitan | 70.7 | 71.6 | 71.6 | 70.8 | 69.0 |

| Presidential job approval rating | |||||

| Approval | 32.3 | 33.1 | 29.1 | 32.6 | 34.2 |

| Disapproval | 58.6 | 57.6 | 60.6 | 58.4 | 57.9 |

| No opinion | 9.1 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 9.0 | 7.9 |

| Party identification | |||||

| Ruling party | 39.8 | 39.9 | 39.7 | 39.6 | 40.2 |

| Opposition party | 28.6 | 26.2 | 28.5 | 29.4 | 30.2 |

| No opinion | 31.6 | 33.9 | 31.8 | 31.0 | 29.6 |

| Affective risk perception* | |||||

| Worried | 53.8 | 55.0 | 62.8 | 52.2 | 44.9 |

| Not worried | 46.2 | 45.0 | 37.2 | 47.8 | 55.1 |

| Cognitive risk perception* | |||||

| Spread further | 30.3 | 35.4 | 52.6 | 26.3 | 9.0 |

| Settle down | 69.7 | 64.6 | 47.4 | 73.7 | 91.0 |

*P<0.05 calculated by χ2 test.

MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

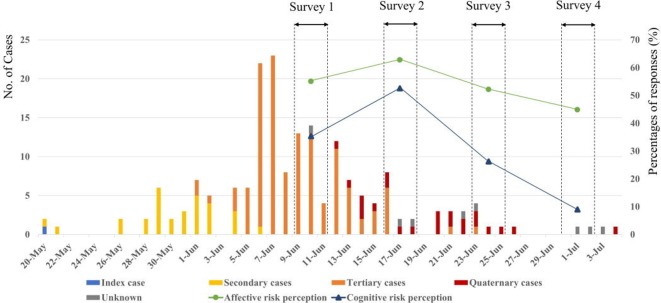

Epidemic curve and time trends of risk perception

Figure 1 reports how the outbreak proceeded, with three overlapping transmission periods, the timing of the four independent surveys and the risk perception rates. Differences were investigated between affective and cognitive risk proportions throughout the epidemic periods. Overall risk perception of the four surveys at affective proportion (53.8%) was nearly two times higher than at cognitive dimension (30.3%). Affective risk perception proportions were always higher than cognitive dimension during the present study periods. Of the affective risk perception, proportion was initially high during survey 1 (55.0%), rose during survey 2 (62.8%) and declined again during surveys 3 and 4 (52.2% and 44.9%, respectively). A similar trend was observed in the cognitive risk perception proportions. The percentages of respondents who reported as being ‘worried’ or ‘spread further’ decreased gradually after survey 2. Cognitive risk perception proportions decreased more rapidly than affective aspect, over time, from 52.6% and 62.8% in survey 2 to 9.0% and 44.9% in survey 4, respectively. At the beginning of the occurrences of tertiary and quaternary cases, we identified high perceived risk in both the affective and cognitive aspect proportions.

Figure 1.

Epidemiologic curve of MERS-CoV, timing of surveys and affective and cognitive risk perceptions. MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Factors associated with the affective risk perception

Table 3 shows the association between variables and risk perception of MERS-CoV at the affective dimension. The result showed that gender, age, educational attainment, self-reported household economic status, area, presidential job approval rating and party identification were significantly associated with affective risk perception. Women (adjusted OR (aOR) 1.72–2.00; 95% CI 1.14 to 2.86) were more likely to perceive MERS-CoV risk at affective dimension, which decreased with time, and subsequently increased again. Groups of older than 40 years were less aware of the risk (aOR 0.58–0.76; 95% CI 0.28 to 1.56) in survey 1; however, they perceived the risk more over time (aOR 2.84–3.29; 95% CI 1.27 to 6.66) in survey 4. The association of education with affective risk perception was non-significant except university degree in the overall survey (aOR 0.73; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.96). Lower economic status and those living in metropolitan cities paid more attention to the affective risk of MERS-CoV in the overall model. Those who disapproved of the president and the ruling party had higher risk perception at the affective dimension; the peak of disapproval was found in survey 1.

Table 3.

Factors associated with affective risk perception of MERS-CoV

| Variables | Overall | Survey 1 | Survey 2 | Survey 3 | Survey 4 |

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.78* (1.49 to 2.13) | 1.83* (1.26 to 2.66) | 1.72* (1.14 to 2.60) | 1.72* (1.26 to 2.42) | 2.00* (1.40 to 2.86) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 19–29 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30–39 | 1.76* (1.30 to 2.40) | 0.80 (0.41 to 1.56) | 1.81 (0.94 to 3.46) | 2.19* (1.17 to 4.10) | 3.21* (1.76 to 5.85) |

| 40–49 | 1.57* (1.17 to 2.11) | 0.76 (0.40 to 1.45) | 1.60 (0.88 to 2.90) | 1.72 (0.95 to 3.11) | 3.00* (1.64 to 5.51) |

| 50–59 | 1.36 (1.00 to 1.84) | 0.58 (0.30 to 1.11) | 1.85 (0.96 to 3.55) | 1.10 (0.59 to 2.03) | 2.93* (1.54 to 5.54) |

| 60–69 | 1.35 (0.95 to 1.92) | 0.73 (0.34 to 1.56) | 1.42 (0.69 to 2.93) | 0.86 (0.42 to 1.75) | 3.29* (1.62 to 6.66) |

| ≥70 | 1.67* (1.13 to 2.48) | 0.66 (0.28 to 1.52) | 2.60* (1.13 to 5.98) | 1.55 (0.71 to 3.38) | 2.84* (1.27 to 6.36) |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| Middle school or below | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High school | 0.78 (0.60 to 1.01) | 0.68 (0.39 to 1.19) | 1.25 (0.74 to 2.09) | 0.66 (0.40 to 1.08) | 0.68 (0.41 to 1.15) |

| University | 0.73* (0.55 to 0.96) | 0.64 (0.36 to 1.15) | 1.22 (0.68 to 2.17) | 0.59 (0.34 to 1.03) | 0.60 (0.34 to 1.07) |

| Graduate school | 0.77 (0.52 to 1.12) | 0.89 (0.38 to 2.05) | 0.94 (0.44 to 2.00) | 0.67 (0.30 to 1.49) | 0.64 (0.31 to 1.35) |

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Farming/forestry/fishery | 0.89 (0.55 to 1.42) | 0.99 (0.35 to 2.81) | 0.65 (0.23 to 1.85) | 1.53 (0.62 to 3.78) | 0.69 (0.27 to 1.08) |

| Self-employed | 0.84 (0.61 to 1.17) | 0.90 (0.47 to 1.72) | 0.56 (0.28 to 1.11) | 1.53 (0.78 to 3.03) | 0.68 (0.36 to 1.31) |

| Blue-collar | 1.21 (0.87 to 1.70) | 1.20 (0.59 to 2.45) | 1.08 (0.54 to 2.18) | 2.08 (1.0 to 4.35) | 0.84 (0.44 to 1.64) |

| White-collar | 1.10 (0.81 to 1.51) | 1.26 (0.68 to 2.35) | 0.86 (0.44 to 1.68) | 1.84 (0.92 to 3.66) | 0.81 (0.44 to 1.46) |

| Home maker | 1.03 (0.74 to 1.44) | 1.01 (0.53 to 1.92) | 1.01 (0.49 to 2.09) | 1.81 (0.89 to 3.67) | 0.62 (0.32 to 1.18) |

| Student | 1.01 (0.66 to 1.54) | 0.55 (0.24 to 1.30) | 0.78 (0.33 to 1.85) | 1.66 (0.64 to 4.34) | 1.46 (0.64 to 3.33) |

| Self-reported household economic status | |||||

| Upper | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Upper middle | 1.91* (1.05 to 3.50) | 1.95 (0.59 to 6.48) | 1.71 (0.63 to 4.70) | 2.20 (0.62 to 7.85) | 2.14 (0.51 to 8.93) |

| Middle | 1.84* (1.03 to 3.27) | 1.83 (0.57 to 5.89) | 1.91 (0.74 to 4.96) | 2.60 (0.79 to 8.55) | 1.84 (0.46 to 7.35) |

| Lower middle | 2.14* (1.19 to 3.85) | 1.97 (0.60 to 6.47) | 2.12 (0.81 to 5.58) | 2.94 (0.88 to 9.78) | 2.30 (0.56 to 9.40) |

| Lower | 2.28* (1.25 to 4.14) | 2.24 (0.66 to 7.64) | 2.78* (1.10 to 7.65) | 3.45* (1.02 to 11.69) | 1.98 (0.48 to 8.14) |

| MERS-CoV-affected area | |||||

| Non-affected area | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Affected area | 0.92 (0.77 to 1.09) | 1.10 (0.76 to 1.59) | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.32) | 1.01 (0.71 to 1.43) | 0.74 (0.53 to 1.02) |

| Residential area | |||||

| Non-metropolitan | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Metropolitan | 1.26* (1.04 to 1.54) | 1.15 (0.77 to 1.72) | 1.83* (1.21 to 2.76) | 0.99 (0.66 to 1.49) | 1.19 (0.82 to 1.74) |

| Presidential job approval rating | |||||

| Approval | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Disapproval | 2.63* (2.17 to 3.20) | 3.11* (2.07 to 4.67) | 2.19* (1.44 to 3.33) | 2.69* (1.81 to 4.01) | 2.88* (1.93 to 4.30) |

| No opinion | 1.59* (1.19 to 2.12) | 2.40* (1.32 to 4.37) | 0.86 (0.49 to 1.53) | 1.78 (0.93 to 3.41) | 1.74 (0.97 to 3.14) |

| Party identification | |||||

| Ruling party | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Opposition party | 1.68* (1.36 to 2.08) | 2.06* (1.30 to 3.25) | 2.37* (1.48 to 3.79) | 1.15 (0.75 to 1.76) | 1.56* (1.01 to 2.40) |

| No opinion | 1.19 (0.98 to 1.44) | 1.17 (0.78 to 1.74) | 1.64* (1.10 to 2.46) | 0.98 (0.66 to 1.46) | 1.07 (0.72 to 1.60) |

*P<0.05.

aOR, adjusted OR; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Factors associated with the cognitive risk perception

Unlike the cognitive risk perception, no difference was found by gender in the cognitive risk perception (table 4). Furthermore, respondents aged 30 years and older were consistently less aware of the cognitive risk during MERS-CoV epidemic. Generally, no not statistically significant association was found with educational attainment, occupation, self-reported household economic status, MERS-CoV-affected area and metropolitan area. Similar to the affective dimension, those who disapproved of the president and the ruling party had higher risk perceptions at the cognitive dimension.

Table 4.

Factors associated with cognitive risk perception of MERS-CoV

| Variables | Overall | Survey 1 | Survey 2 | Survey 3 | Survey 4† |

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.20) | 1.14 (0.73 to 1.70) | 0.97 (0.64 to 1.46) | 0.81 (0.54 to 1.21) | 1.19 (0.63 to 2.25) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 19–29 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30–39 | 0.76 (0.55 to 1.05) | 0.26* (0.13 to 0.54) | 1.26 (0.67 to 2.37) | 0.91 (0.47 to 1.75) | 0.84 (0.33 to 2.11) |

| 40–49 | 0.64* (0.47 to 0.88) | 0.21* (0.10 to 0.42) | 0.99 (0.53 to 1.83) | 0.81 (0.42 to 1.57) | 0.65 (0.27 to 1.57) |

| 50–59 | 0.44* (0.32 to 0.62) | 0.12* (0.06 to 0.25) | 1.19 (0.63 to 2.28) | 0.35* (0.17 to 0.72) | 0.25* (0.08 to 0.73) |

| 60–69 | 0.30* (0.20 to 0.46) | 0.13* (0.06 to 0.31) | 0.35* (0.16 to 0.77) | 0.26* (0.11 to 0.65) | 0.17* (0.04 to 0.69) |

| ≥70 | 0.26* (0.16 to 0.44) | 0.08* (0.03 to 0.23) | 0.61 (0.26 to 1.41) | 0.20* (0.06 to 0.63) | 0.12* (0.02 to 0.65) |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| Middle school or below | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High school | 0.81 (0.58 to 1.13) | 0.58 (0.30 to 1.12) | 1.41 (0.75 to 2.68) | 0.45* (0.21 to 0.97) | 0.56 (0.20 to 1.55) |

| University | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.32) | 0.47* (0.24 to 0.95) | 2.11 (1.06 to 4.21) | 0.73 (0.34 to 1.57) | 0.42 (0.13 to 1.36) |

| Graduate school | 0.92 (0.58 to 1.46) | 0.12* (0.04 to 0.38) | 1.83 (0.78 to 4.34) | 1.27 (0.47 to 3.43) | 0.64 (0.17 to 2.37) |

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Farming/forestry/fishery | 1.51 (0.85 to 2.68) | 1.72 (0.59 to 5.06) | 1.52 (0.49 to 4.68) | 3.04 (0.93 to 1.0) | 1.12 (0.22 to 5.75) |

| Self-employed | 0.94 (0.63 to 1.40) | 1.08 (0.49 to 2.35) | 0.92 (0.43 to 1.96) | 1.76 (0.70 to 4.38) | 0.31 (0.09 to 1.12) |

| Blue-collar | 1.22 (0.81 to 1.84) | 1.38 (0.61 to 3.15) | 1.07 (0.51 to 2.22) | 1.75 (0.66 to 4.67) | 0.84 (0.28 to 2.56) |

| White-collar | 1.05 (0.72 to 1.52) | 1.46 (0.71 to 3.02) | 0.94 (0.48 to 1.87) | 1.64 (0.68 to 3.95) | 0.56 (0.21 to 1.55) |

| Home maker | 1.22 (0.81 to 1.83) | 1.23 (0.55 to 2.74) | 1.37 (0.65 to 2.92) | 1.86 (0.71 to 4.92) | 0.85 (0.29 to 2.50) |

| Student | 0.81 (0.51 to 1.30) | 0.68 (0.26 to 1.75) | 0.78 (0.33 to 1.84) | 1.01 (0.34 to 2.98) | 0.47 (0.12 to 1.84) |

| Self-reported household economic status | |||||

| Upper | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | u.a. |

| Upper middle | 0.96 (0.51 to 1.81) | 1.17 (0.34 to 4.05) | 0.71 (0.27 to 1.85) | 0.71 (0.19 to 2.61) | u.a. |

| Middle | 0.81 (0.44 to 1.47) | 1.26 (0.39 to 4.05) | 0.59 (0.25 to 1.40) | 0.86 (0.26 to 2.87) | u.a. |

| Lower middle | 1.22 (0.66 to 2.25) | 1.76 (0.53 to 5.86) | 0.98 (0.40 to 2.38) | 1.13 (0.33 to 3.88) | u.a. |

| Lower | 1.06 (0.57 to 1.99) | 2.22 (0.64 to 7.74) | 0.82 (0.32 to 2.12) | 1.12 (0.32 to 4.0) | u.a. |

| MERS-CoV-affected area | |||||

| Non-affected area | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Affected area | 1.05 (0.86 to 1.28) | 1.43 (0.94 to 2.19) | 0.79 (0.54 to 1.16) | 1.02 (0.69 to 1.52) | 1.18 (0.66 to 2.11) |

| Residential area | |||||

| Non-metropolitan | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Metropolitan | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.14) | 0.57* (0.35 to 0.93) | 1.34 (0.84 to 2.12) | 1.08 (0.67 to 1.75) | 0.69 (0.38 to 1.33) |

| Presidential job approval rating | |||||

| Approval | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Disapproval | 3.55* (2.77 to 4.55) | 5.41* (3.25 to 9.01) | 3.00 (1.96 to 4.59*) | 3.77* (2.13 to 6.68) | 4.05* (1.44 to 11.41) |

| No opinion | 1.75* (1.22 to 2.52) | 2.00 (0.96 to 4.16) | 0.94 (0.49 to 1.80) | 3.26 (1.46 to 7.30) | 1.55 (0.37 to 6.45) |

| Party identification | |||||

| Ruling party | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Opposition party | 1.38* (1.09 to 1.75) | 2.01* (1.19 to 3.39) | 1.86* (1.21 to 2.88) | 1.09 (0.65 to 1.84) | 1.08 (0.48 to 2.45) |

| No opinion | 1.23 (0.98 to 1.55) | 1.55 (0.97 to 2.48) | 1.82* (1.20 to 2.76) | 0.79 (0.47 to 1.34) | 0.91 (0.40 to 2.08) |

*P<0.05.

†There was small sample size of those who perceived cognitive risk in the upper economic level in survey 4, the self-reported household economic status was excluded from the survey 4 model.

aOR, adjusted OR; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; u.a., unavailable data.

Discussion

The aims of the present study were to explore the differences in risk perception at affective and cognitive dimensions and examine the relationship between trust in government and both risk perceptions. To do this end, we investigated the pattern of affective and cognitive risk perception proportions during MERS-CoV epidemic, respectively; analysed the correlations of presidential job approval rating and risk perceptions (affective and cognitive).

First, we found that affective risk perception responded faster and lasts longer. The affective risk perception proportions were always higher than at the cognitive dimension. Risk perception increased with new generations of transmission, such as with the tertiary and quaternary infections. Both risk perceptions tended to decrease over time and the cognitive risk perception declined more rapidly.

However, our results that affective reaction tends to decrease before cognitive reaction are inconsistent with those of previous studies.12 17 Relevant research in risk perception have proposed that affective reaction is fast, efficient, automatic and experiential compared with cognitive reaction.14–16 We can consider the possibility that damaged trust in government as a responsible risk manager might have further evoked the emotional risk perception.8 9 23–25 While the affective or cognitive reaction does not individually have an impact on the different stages of the epidemic, they can, however, affect it together, simultaneously, indicating both affective and cognitive risk perceptions.12 17 26 29 Additional research is needed to understand why the affective risk perception was higher and lasted longer than that of the cognitive risk perception during MERS-CoV epidemic in South Korea.

Second, our study shows that low trust in government had influenced both affective and cognitive risk perceptions. After party identification was adjusted for, we examined correlation with trust and risk perception. It is consistent with previous studies that trust in government could shape the public’s risk perception (both affective and cognitive).21 22 26 27 However, the previous studies have not distinguished between affective and cognitive reactions when evaluating the impact of trust regarding contagious diseases during outbreaks.3 12 23 24 28–30 Our findings suggest that trust in government is correlated with both affective and cognitive risk perceptions and it is important to understand the relationship between trust in government and two different aspects of risk perceptions. Those who did not support the president were reported to have had higher risk perception in both the affective and cognitive levels. In the group that did not approve of the president, the probabilities of risk perception were higher at the cognitive dimension than at affective dimension. In the early days of the MERS-COV outbreak, the government did not specify details regarding scientifically uncertain information in order to reduce public anxiety over the crisis, nor did the government disclose which hospitals the confirmed patients had visited. This resulted in increased public distrust in the government.4 5 8 9 Similar patterns of distrust in the government were associated with the spread of infection, during the outbreak of Ebola.34 35 Those who disapproved of the ruling party had also higher risk perceptions. Identification of party can be classified in the political aspect of trust.36 There is need to investigate further comprehensive understanding of trust’s effect on risk perception.

Third, we found that gender, age, self-reported household economic status, residential area and party identification correlated significantly with risk perception. According to multiple logistic regression analyses, being female predisposed to greater risk perception at the affective risk perception, but not at the cognitive dimension. Previous studies that investigated risk perception by gender also showed that a lower risk perception was associated with the male gender.3 28 37–39 A possible explanation for lower perception of risk by males is that males have more to gain from risky behaviours.40 However, previous studies did not distinguish between the levels of risk perception. Further research is needed to determine why the same female group showed differences in perceived risk for affective and cognitive levels. The older the respondents, the lower the perceived cognitive dimension, but the opposite occurred weakly in the affective risk perception. The correlation with age and affective risk perception was not significant in most models (survey 1, survey 2 and survey 3 models). After trust in government was adjusted for, we found correlation between older age and lower cognitive risk perception. Further research is needed as to why the effect of trust in the government had not been shown in the affective risk perception.

Given that some hierarchy-specific trends in income level were observed only in the overall model of affective risk perception, these results were consistent with previous studies.41–43

The location effect on risk perception also was evaluated in this study, but it was not clear on the correlation with risk proximity and risk perception.44 There were no significant differences in the proportions of those with risk perception according to the major socioeconomic characteristics (education, income level, occupation). It is necessary to further investigate the correlation with demographic factors and risk perception.

This study, which used a serial cross-sectional study design, had some limitations. First, the study used a cross-sectional study design. Thus, causal relations between personal characteristics and risk perceptions could not be determined—rather, it could only suggest their relevance. Second, this study could not evaluate the intensity of risk perception, because it only included questions focusing on whether or not participants recognised the risk at the different levels. It would be useful to evaluate risk perceptions of respondents qualitatively if questions about the circumstances and characteristics of risk perception were surveyed in future studies. Third, because of the rapidly evolving epidemic, this study could not evaluate the validity of the questionnaire using a test–retest design. Fourth, small sample size of some variables once stratified (eg, self-reported household economic status) led to the exclusion of major socioeconomic characteristics from further analyses.

Conclusions

This study is the first to evaluate the differences in risk perception at affective and cognitive dimensions and the relationship between trust in the government and both risk perceptions during the MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea. The study also reported various factors influencing risk perception. We found that affective risk perception responded faster and lasts longer; and low trust in the government influenced both affective and cognitive risk perceptions. Quality of risk communication can create conditions for modulating the easy spread of emerging contagious diseases. To prevent the failure of epidemic management, further efforts are needed to understand the mechanism behind the general public’s risk perception, the governmental public health sector, as well as the society of academy. Planning and implementation of strategies that consider the risk awareness mechanism will be a significant step in the right direction during national infectious disease crises.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gallup Korea, an affiliation of Gallup International, for supporting surveys and data collection for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: WMJ participated and analysed the data, interpreted the data, drafted and amended the manuscript. UNK, SC and HJ contributed to the analysis of the data, interpreted the data, drafted and amended the manuscript. DHJ contributed to questionnaire design, coordinated data collection and data interpretation. SJE and JYL contributed to study design, supervised the research, data interpretation and amended the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul Metropolitan Government–Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center (IRB No 20190515/07-2019-11/062). The need for informed consent was waived by the board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health and Welfare The 2015 MERS outbreak in the Republic of Korea: learning from MERS. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization WHO MERS-CoV global summary and assessment of risk. Geneva: WHO, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ro J-S, Lee J-S, Kang S-C, et al. Worry experienced during the 2015 middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) pandemic in Korea. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173234 10.1371/journal.pone.0173234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi JW, Kim KH, Moon JM, et al. Public health crisis response and establishment of a crisis communication system in South Korea: lessons learned from the MERS outbreak. J Korean Med Assoc 2015;58:624–34. 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.7.624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim EY, Liao Q, Yu ES, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome in South Korea during 2015: risk-related perceptions and quarantine attitudes. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:1414–6. 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S-I. Costly lessons from the 2015 middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreak in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health 2015;48:274 10.3961/jpmph.15.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang S, Cho S-I. Middle East respiratory syndrome risk perception among students at a university in South Korea, 2015. Am J Infect Control 2017;45:e53–60. 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choe SH. MERS tarnishes Korean president’s image as leader. The New York Times 2015;June:12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SY, Yang HJ, Kim G, et al. Preventive behaviors by the level of perceived infection sensitivity during the Korea outbreak of middle East respiratory syndrome in 2015. Epidemiol Health 2016;38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheeran P, Harris PR, Epton T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people's intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol Bull 2014;140:511–43. 10.1037/a0033065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leppin A, Aro AR. Risk perceptions related to SARS and avian influenza: theoretical foundations of current empirical research. Int J Behav Med 2009;16:7–29. 10.1007/s12529-008-9002-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao Q, Cowling BJ, Lam WWT, et al. Anxiety, worry and cognitive risk estimate in relation to protective behaviors during the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic in Hong Kong: ten cross-sectional surveys. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:169 10.1186/1471-2334-14-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolison JJ, Hanoch Y. Knowledge and risk perceptions of the Ebola virus in the United States. Prev Med Rep 2015;2:262–4. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, et al. Emotion and decision making. Annu Rev Psychol 2015;66:799–823. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron LD, Leventhal H. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. Psychology Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, et al. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Anal 2004;24:311–22. 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao Q, Cowling B, Lam WT, et al. Situational awareness and health protective responses to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2010;5:e13350 10.1371/journal.pone.0013350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahneman D, Slovic SP, Slovic P, et al. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge university press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gee S, Skovdal M. The role of risk perception in willingness to respond to the 2014-2016 West African Ebola outbreak: a qualitative study of international health care workers. Glob Health Res Policy 2017;2:21 10.1186/s41256-017-0042-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegrist M. Trust and risk perception: a critical review of the literature. Risk Anal 2019;27 10.1111/risa.13325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegrist M. The influence of trust and perceptions of risks and benefits on the acceptance of gene technology. Risk Anal 2000;20:195–204. 10.1111/0272-4332.202020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegrist M, Cvetkovich G. Perception of hazards: the role of social trust and knowledge. Risk Anal 2000;20:713–20. 10.1111/0272-4332.205064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi D-H, Shin D-H, Park K, et al. Exploring risk perception and intention to engage in social and economic activities during the South Korean MERS outbreak. Int J Commun Syst 2018;12:21. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S, Kim S. Exploring the determinants of perceived risk of middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1168 10.3390/ijerph15061168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim CW, Song HR. Structural relationships among public’s risk characteristics, trust, risk perception and preventive behavioral intention: The case of MERS in Korea. Crisisnomy 2017;13:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altarawneh L, Mackee J, Gajendran T. The influence of cognitive and affective risk perceptions on flood preparedness intentions: a dual-process approach. Procedia Engineering 2018;212:1203–10. 10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terpstra T. Emotions, trust, and perceived risk: affective and cognitive routes to flood preparedness behavior. Risk Analysis 2011;31:1658–75. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibuka Y, Chapman GB, Meyers LA, et al. The dynamics of risk perceptions and precautionary behavior in response to 2009 (H1N1) pandemic influenza. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:296 10.1186/1471-2334-10-296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.S-H O, Paek H-J, Hove T. Cognitive and emotional dimensions of perceived risk characteristics, genre-specific media effects, and risk perceptions: the case of H1N1 influenza in South Korea. Asian J Commun 2015;25:14–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadique MZ, Edmunds WJ, Smith RD, et al. Precautionary behavior in response to perceived threat of pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1307–13. 10.3201/eid1309.070372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffin RJ, Neuwirth K, Dunwoody S, et al. Information sufficiency and risk communication. Media Psychol 2004;6:23–61. 10.1207/s1532785xmep0601_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terwel BW, Harinck F, Ellemers N, et al. Competence-based and integrity-based trust as predictors of acceptance of carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS). Risk Anal 2009;29:1129–40. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01256.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allum N. An empirical test of competing theories of hazard-related trust: the case of GM food. Risk Anal 2007;27:935–46. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2007.00933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vinck P, Pham PN, Bindu KK, et al. Institutional trust and misinformation in the response to the 2018–19 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: a population-based survey. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:529–36. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30063-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai L, Blair R, Morse B. Patterns of trust and compliance in the fight against Ebola: results from a population-based survey of Monrovia, Liberia. Economic Impacts of Ebola, Bulletin Three 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moy P, Pfau M. With Malice Toward All?The Media and Public Confidence in Democratic Institutions: The Media and Public Confidence in Democratic Institutions: ABC-CLIO 2000.

- 37.de Zwart O, Veldhuijzen IK, Elam G, et al. Perceived threat, risk perception, and efficacy beliefs related to SARS and other (emerging) infectious diseases: results of an international survey. Int J Behav Med 2009;16:30–40. 10.1007/s12529-008-9008-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leung GM, Ho L-M, Chan SKK, et al. Longitudinal assessment of community psychobehavioral responses during and after the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1713–20. 10.1086/429923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finucane ML, Slovic P, Mertz CK, et al. Gender, race, and perceived risk: The 'white male' effect. Health Risk Soc 2000;2:159–72. 10.1080/713670162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson DJ, Freudenburg WR. Gender and environmental risk concerns: a review and analysis of available research. Environ Behav 1996;28:302–39. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber EU, Blais Ann-Renée, Betz NE. A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. J Behav Decis Mak 2002;15:263–90. 10.1002/bdm.414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang L, Zhou Y, Han Y, et al. Effect of the Fukushima nuclear accident on the risk perception of residents near a nuclear power plant in China. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:19742–7. 10.1073/pnas.1313825110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benford RD, Moore HA, Williams JA. In whose backyard?: concern about siting a nuclear waste facility. Sociol Inq 1993;63:30–48. 10.1111/j.1475-682X.1993.tb00200.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson BB. Residential location and psychological distance in Americans' risk views and behavioral intentions regarding Zika virus. Risk Anal 2018;38:2561–79. 10.1111/risa.13184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033026supp001.pdf (63.3KB, pdf)