Abstract

Objectives

The aim was to provide figures for drug shortages in France and describe their characteristics, causes and trends between 2012 and 2018.

Methods

Data from the national reporting system from the Agency of Medicine and Health Product Safety (ANSM) was analysed. This database contains information regarding effective and predicted shortages of major therapeutic of interest drugs (ie, drugs whose shortage would be life-threatening or representing a loss of treatment opportunity for patients with a severe disease) which are mandatory reported by marketing authorisation holders to the ANSM. Data are presented as numbers or percentages of pharmaceutical products (ie, the product name and its formulation) reported on shortage between 2012 and 2018.

Results

There were 3530 pharmaceutical products reported on shortage during the period, including 1833 different active substances. Drugs on shortage were mostly old products (63.4%) with national marketing authorisation procedures (62.8%), as well as injectable and oral forms (47.5% and 43.3%, respectively). Anti-infectives for systemic use ranked first (18%), followed by nervous and cardiovascular system drugs and by antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents (17.4%, 12.5% and 10.4%, respectively). The number of reported shortages presented a fourfold increase between 2012 and 2018 and a sharp rise in 2017 and 2018, along with a rise in the number of active substances on shortage. The therapeutic classes concerned remained similar over time. Manufacturing and material supply issues were the main reported reasons for the shortage each year (30%) and there was an overall rise of pharmaceutical market reasons.

Conclusion

Drug shortages were increasingly reported in France. Preventive measures should specifically target the products most on shortage, in particular old drugs, injectable, anti-infective, nervous system and cardiovascular system drugs as well as antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents.

Keywords: drug shortages, supply of medicines, short supply, major therapeutic interest, pharmacosurveillance, France, national reporting system

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to describe and analyse drug shortages in France using a national reporting system over a 7-year period, from 2012 to 2018.

A drug shortage is according to pharmaceutical company’s perspective and reflects the inability of a pharmaceutical company to produce a drug for national needs, whereas a short supply is according to patient’s perspective and defines the unavailability of a drug in a pharmacies.

Trends of drug shortages were described according to both pharmaceutical products (defined as a combination of the active substance, the formulation and the packaging) and international non-proprietary name drugs, allowing a more detailed description and interpretation of drug shortages and their causes.

Drug shortages were defined as both effective and predicted shortages of major therapeutic of interest drugs, which may not allow generalisation to all drugs.

Reporting predictive and effective shortages to Agency of Medicine and Health Product Safety will indeed be cases where the risk of shortage will not become a short supply, but these situations reflect a production problem and may lead to short supply.

Introduction

Drug shortages are a major public health threat worldwide occurring in all therapeutic classes.1–7 According to the WHO, a drug shortage is defined as an insufficiency in the supply of medicines, health products and vaccines that are identified by the health system as essential to meet public health and patient need.8 Drug shortages can have detrimental effects on patients' care as they may result in delayed treatment or switches to alternative therapies, therefore leading to disease progression, increased risk of adverse effects or medication errors as well as rising healthcare costs.9–11 Multiple reasons, such as manufacturing issues, regulatory issues or economic factors, in addition to increased global demand have been suggested to underlie drug shortages.1 3 12 13

In France, the management of drug shortages and short supply was first regulated in 2012 with a decree dated 28 September 2012 on the supply of human drugs.14 This decree requires the pharmaceutical operators commercialising drugs in France to ensure an appropriate and continuous supply of wholesalers and hospitals within 72 hours. Marketing authorisation holders (MAHs) were thus mandated to notify the French National Agency of Medicine and Health Product Safety (Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des produits de santé—ANSM) of any effective or predicted drug shortages, specifying the available stocks, the estimated period of shortage, the deadline for the availability of the product, as well as the substitute drugs. In 2016, the French health law of 26 January and its decree of 20 July targeted the shortages of drugs of major therapeutic of interest (MTI) defined as drugs for which unavailability would be life-threatening or represent a loss of treatment opportunity.15 The list of the therapeutic classes of MTI drugs was provided by the ministerial order of 27 July (online supplementary materials).16 This definition relates to some Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classes and thus comprises all drugs from the same therapeutic class, whether they are generics or brand names. The shortage of an MTI drug has to be reported by the MAH to the ANSM even when another competing equivalent MTI drug is available. MAH are not aware of the productions capacities of other MAHs and thus of the availability of equivalent MIT drugs at the time of the report. The impact of a shortage in terms of public health and production is then estimated by the ANSM. The decree of 20 July also warranted new regulatory tools in order to reinforce the legal obligations of pharmaceutical companies and wholesalers. MAHs and operators were required to develop shortage management plans (Plan de Gestion des Pénuries), and wholesalers were not allowed to export MTI drugs that are on effective or predicted shortage. Responsibilities of pharmaceutical operators were also strengthened by the implementation of administrative or financial penalties in case of non-compliance.15 17

bmjopen-2019-034033supp001.pdf (82.2KB, pdf)

According to a survey conducted in 2014, drug shortages were increasingly reported in Europe and occurred daily or weekly.3 While the issue of drug shortages has been widely studied in the USA,18–21 figures in Europe are scarce and national trends of drug shortages are not available.22 The identification and surveillance of the most frequent drugs on shortage and the analysis of their causes may allow implementing targeted preventive measures in order to limit the negative impacts on patient care. The present study therefore aimed to describe the characteristics and trends of reported shortages of MTI drugs in France using the national reporting system from the ANSM.

Methods

This observational retrospective study analysed the surveillance reporting system of drug shortages from the ANSM between 2012 and 2018. Since 2012, MAHs are indeed obliged to declare any effective or predicted shortage of MTI drugs to the ANSM. The reporting database contains the information reported by the MAHs via completed declaration forms. The following data were analysed: (1) from declaration forms: dates or report, drugs names, active substances (international non-proprietary names (INN)), routes of administration, setting first impacted by the shortage (community pharmacy and/or hospital), reasons for the shortages (available since 2015); (2) from the marketing authorisation dossier and the summary of the product characteristics: dates and procedures of marketing authorisation grants, storage conditions and (3) ATC codes according to the WHO Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology.23

MAHs shall follow the manufacturing circuit of its drugs, and reporting to the ANSM is required for each dysfunction that may result in effective or predictive shortages. A drug shortage reflects the inability of a pharmaceutical company to produce a drug and maintain its marketing at a national level, whereas the short supply defines the unavailability of a drug in pharmacies. In addition, a short supply assesses the sanitary risk in the scope of the pharmacy practice whereas drug shortages highlight issues in pharmaceutical production. According to these definitions of drug shortages, short supply was not considered in present study.

Reports of drug shortage were therefore defined as both effective and predicted shortages of MTI drugs recorded by the ANSM each year.

Duration of the marketing authorisation grant was defined as the difference between the years of the shortage reports and the year when the marketing authorisation was granted.

Causes of shortages were categorised into: (1) manufacturing issues, including the stage of manufacturing or packaging of the final product; (2) material issues, that is defect in raw materials, excipients, packaging and semi-finished or bulk pharmaceuticals; (3) pharmaceutical market, that is related to the difficulty of the operator to purchase products, including insufficient production capacity; (4) regulatory issues, that is new regulation directly related to the delayed marketing and (5) inventory and storage practices, that is stock errors or inappropriate management of expiry date.

Data were presented in numbers or in percentages of pharmaceutical products reported on shortage. Pharmaceutical products were defined as a combination of the INN, the formulation and the packaging and are identified by the code identifiant de spécialité. Therefore, a shortage of a pharmaceutical product does not necessarily imply the shortages of all drugs with the same INN.

There were no missing data except for marketing authorisation procedures and duration of marketing authorisation grants.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the design, planning and conception of this study.

Results

Between the years 2012 and 2018 and 3530 pharmaceutical products were reported of on shortage, including 1833 different INN drugs. The overall characteristics of the pharmaceutical products reported on shortage from 2012 to 2018 are presented in table 1. Drugs with a marketing authorisation granted more than 10 years ago (63.4%) and according to a national procedure (62.8%) were the most concerned. Generics drugs accounted for 34% of shortages overall and for 17% of old drugs (marketing authorisation grant >10 years). Community pharmacies and hospitals were similarly first impacted by shortages. Injectable and oral were the most commonly affected forms (with 47.5% and 43.3%, respectively). With regards to ATC classes, anti-infectives for systemic use ranked first with 18% of total shortage reports, followed by nervous and cardiovascular system drugs as well as by antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents (with 17.4%, 12.5% and 10.4, respectively) (table 1). Antibacterial for systemic use and vaccines accounted for 53% and 19% of anti-infectives shortages, respectively. Antiepileptic, anesthesic and analgesic products were among the most common nervous system drugs on shortage (22%, 18% and 16%, respectively). Cephalosporins were the most common antibacterial drug class reported on shortage.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pharmaceutical products reported on shortage in 2012–2018

| 2012–2018 n (%) |

|

| Total | 3530 (100) |

| Marketing authorisation procedures | |

| National | 2217 (62.8) |

| European | 1249 (35.4) |

| Unavailable data | 64 (1.81) |

| Duration of marketing authorisation grants | |

| >10 years | 2237 (63.4) |

| ≤10 years | 1212 (34.3) |

| Unavailable data | 81 (2.30) |

| Pharmaceutical forms | |

| Oral | 1529 (43.3) |

| Injectable | 1675 (47.5) |

| Others | 326 (9.24) |

| Storage conditions | |

| Ambient temperature | 2995 (84.8) |

| +2°C<Temperature < +8°C | 533 (16.0) |

| −18°C<Temperature | 2 (0.00) |

| ATC* classes | |

| Alimentary tract and metabolism | 217 (6.15) |

| Anti-infectives for systemic use | 634 (18.0) |

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 367 (10.4) |

| Antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents | 39 (1.10) |

| Blood and blood forming organs | 312 (8.84) |

| Cardiovascular system | 442 (12.5) |

| Dermatologicals | 59 (1.67) |

| Genitourinary system and reproductive hormones | 151 (4.30) |

| Musculoskeletal system | 155 (4.40) |

| Nervous system | 613 (17.4) |

| Respiratory system | 119 (3.40) |

| Sensory organs | 97 (2.80) |

| Systemic hormonal preparations | 160 (4.53) |

| Various/others | 165 (4.70) |

*ATC: Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification of drugs: according to the WHO collaborating center for Drug Statistics Methodoly.

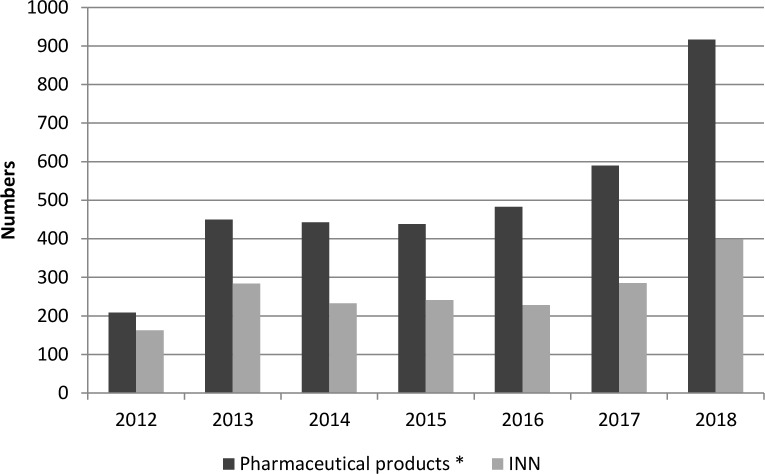

Trends in the number of pharmaceutical products and INN drugs reported on shortage were shown in figure 1. There was a fourfold increase in the total products on shortage between 2012 and 2018, to reach 917 shortages in 2018. The numbers of INN on shortage were similar in 2013 and 2017 but presented a twofold increase between the years 2012 and 2018, to reach a peak in 2018 (n=399) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in shortages by numbers of pharmaceutical products and international non-proprietary name drugs (INN) (2012–2018) in France. *Pharmaceutical products: defined by a combination of the INN, the formulation and the packaging.

Injectable and oral forms remained the two main pharmaceutical forms on shortage each year (from 51% to 37% and 40% to 56% between 2012 and 2018 for injectable and oral forms, respectively).

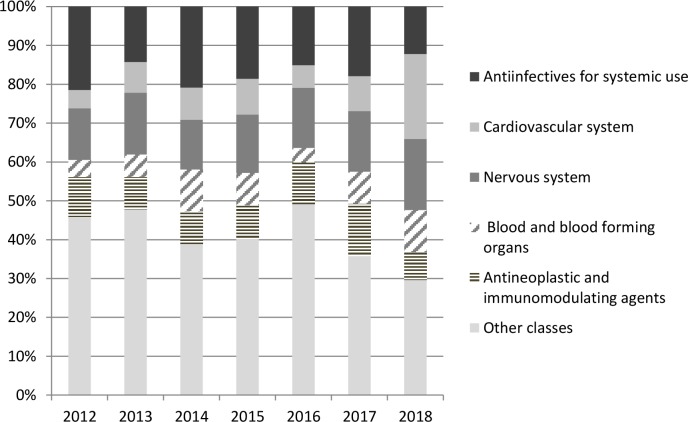

All therapeutic classes were reported on shortage each year. Figure 2 presents the trends in proportions of shortage of pharmaceutical products by ATC classes from 2012 to 2018. The distribution of ATC classes reported on shortage was similar over time. Anti-infectives for systemic use, nervous system drugs as well as antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents ranked among the first classes on shortage until 2017. Shortages of cardiovascular system drugs were increasingly reported since 2012 and a sharp rise occurred in 2018 (n=216 reports). Cardiovascular drugs ranked first in 2018 (24%), explained by products of valsartan accounting for half of shortages. The proportion of nervous system drugs, anti-infectives and antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents on shortage was relatively stable over the years (figure 2). Yet, a continuous increase of shortages was observed for nervous system drugs that ranked second in 2018 (n=181 reports) (figure 2). In 2018, antiepileptics accounted for the most reported class of nervous system drugs on shortage (34%), of which 13 were topiramate-based products. There was also a rise in shortages of anti-infective products in 2017 (n=122), driven in half by antibacterial drugs, in particular cephalosporins (n=23). Among anti-infectives, antibacterial drugs were the first class reported on shortage each year between 2012 and 2018, followed by vaccines (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Trends in the proportion of pharmaceutical products on shortage by ATC classes (2012–2018). ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification of drugs: according to the WHO collaborating center for Drug Statistics Methodology.

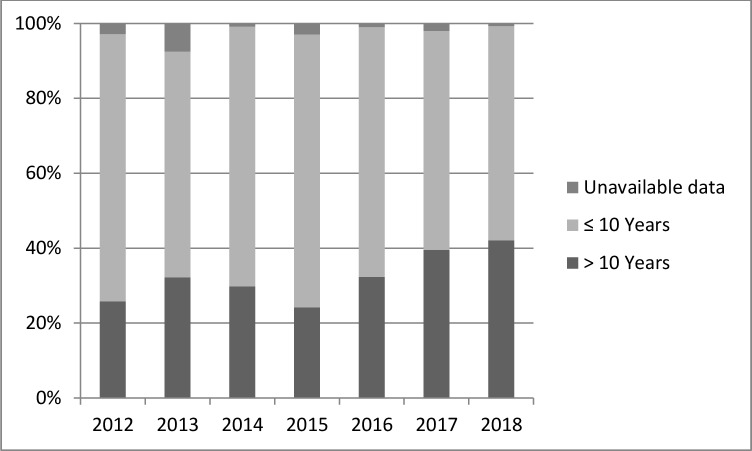

Figure 3 presents the trends in the proportion of shortage of pharmaceutical products by duration of marketing authorisation grant from 2012 to 2018. During that period, drugs with an old marketing authorisation grant (of more than 10 years) were the most reported on shortage.

Figure 3.

Trends in the proportion of pharmaceutical products on shortage by duration of marketing authorisation grants.

Drug shortages first impacting hospital settings accounted for half of the shortages in 2017 and for a third in other years. Similar trends in the proportion of shortage were observed for settings first impacted (data not shown).

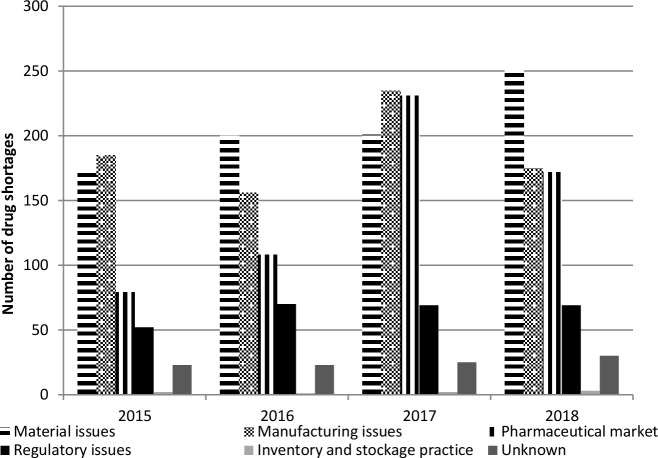

Trends in the reported causes of shortages between 2015 and 2018 are shown in figure 4. Manufacturing and material supply issues were the main reasons each year with approximately 30% of the shortage share. There was an overall rise of pharmaceutical market reasons.

Figure 4.

Trends in the causes of shortages of pharmaceutical products in 2015–2018.

Discussion

Based on the French national reporting system, the present study described the characteristics of MTI drugs reported on shortage in France between 2012 and 2018 as mostly: old drugs, drugs with national marketing authorisation procedures and injectables. Both hospital and community pharmacies were similarly affected by shortages and one third of them first occurred in hospital settings. Four therapeutic classes (anti-infectives, nervous system, cardiovascular system drugs, antineoplastics and immunomodulating agents) remained the most on shortage with the same distribution over the years. The number of pharmaceutical products reported on shortage increased by fourfold between 2012 and 2018, along with a rise in the number of INN drugs. In 2018, the number of pharmaceutical products on shortage reached a peak, with 399 different active substances from all therapeutic classes affected by shortage. Compared with the number (n=2800) of approved and marketed INN drugs in France in 2016,24 there were approximately 13% of INN drugs on shortage in 2018 and 60% during the 2012–2018 period.

The present rise in drug shortages in France is concomitant with the observed trends in the USA, reflecting the international public health challenge of drug shortages. According to the University of Utah Drug Information Service (UUDIS), new drugs on shortage in the USA were found to triple between 2004 and 2018, although a decrease occurred since 2012.25 Comparisons of figures between the two countries are yet limited by differences in definitions of drug shortage2 as well as differences in pharmaceutical products, blister packaging being less used in the USA.

The four therapeutic classes most impacted by shortages in the present study were anti-infectives for systemic use, nervous system drugs, cardiovascular drugs and antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents, in accordance with previous results from a European review finding that these same four classes represented over 50% of reported shortage.4 We found that anti-infectives for systemic use represented the first therapeutic class reported on shortage until 2018 (18%) among which antibacterial drugs ranked first each year. This trend is well documented across the USA. Antimicrobials were the most common drug class on shortage in critical care (2001–2016) and emergency medicine practice (2001–2014), representing, respectively, 20% and 24% of US shortages.19 20 Cephalosporins were the most common antibacterial drug class, in accordance with findings from a US study using the UUDIS database from 2001 to 2013.26 Shortages of antimicrobials may not have alternative production sources and may thus require the use of less effective or more toxic alternatives,20 26 leading to worse patient outcomes.18 In a European survey, anti-infectives were also found to be the most common drugs on shortage in hospital pharmacies in 2013, along with cancer drugs.22 The burden of cancer drug shortages was previously highlighted in the USA27 28 and more recently in a hospital paediatric hemato-oncology unit in Belgium.7 A lack of market attractiveness and low profitability has been suggested as a cause of shortages, due to prompting the discontinuation of some long-standing or lower-priced products such as antibiotics and oncologic medicines.1

In the present study, cardiovascular drugs were one of the first therapeutic classes on shortage and the first in 2018 (28%). This was driven by shortages of valsartan products resulting from the detection in 2018 of impurities in the active substance of valsartan-based medicines. As a precaution, all potentially impacted batches of valsartan containing drugs were recalled in France since July 2018.29 Shortage of cardiovascular drugs was also common in the USA.20 30

In this study, shortages mostly involved injectable products each year. This finding is consistent with previous surveys in Europe and USA.4 20 Injectable products are at increased risk of shortage related to quality control concerns because of the complexities associated with manufacturing a sterile product.2 Oral drugs also accounted for a large share of shortages in our study, reflecting that causes of drug shortages goes beyond pure manufacturing problems related to technical issues or quality problems.

According to our results, old drugs were the most reported on shortage during the period from year 2012 to year 2018, with 63.4% of drug shortages while there were 45% of old products on the market in 2018 in France. Age of the marketing authorisation is thus likely to be a major determinant of drug shortage, in accordance with a US study finding that the age of drug was a strong risk factor for shortage in oncology.27 According to the authors, this result suggested that policies focused predominately on promoting increases in distinct suppliers and that competition may not alleviate drug shortages.

The reasons behind drug shortages are complex and many factors may contribute simultaneously. In France, the increase in drug shortage reports may in part be related to changes in the regulations. Since 2012, MAHs are required to report shortages and otherwise subjected to financial sanctions since 2016. Regulatory changes may impact the reporting of drug shortage. Yet, not all drugs were affected by shortage in our study, which goes beyond regulatory changes and is more concordant with increased needs along with inadequate production and supply issues. Raw material shortages and production issues have been considered global and as having similar impacts in European countries.3 4 12 Manufacturing problems stem from concentration and rationalisation of pharmaceutical manufacturing, as well as globalisation.3 In our study, material and manufacturing issues were the main causes of shortages each year and a rise in shortages related to pharmaceutical market was observed over the years. One explanation may be a rise in the global use of pharmaceutical products worldwide. The structure of the pharmaceutical market was previously found to be a key determinant of drug shortages in Finland.12 In our study, pharmaceutical market issues included hospital trade and competitive bidding tenders that may contribute to compromise the supply of MTI drugs at hospital.

Some limitations to the present study should be noted. First, the results were relating to shortage of MTI drugs from national stocks supplies, which may not allow generalisation to all drugs, although MTI drugs include all therapeutic classes. Second, the data were sourced from statement reports of MAHs and missing data cannot be ruled out. According to the definition of drug shortages in France, short supply was not considered in the present study. The combination of data from both authorities and pharmacy practice has been suggested to improve the surveillance.31 This requires a standardisation of definition of drug shortages between European members. Yet, the financial penalty for non-compliance with mandatory declaration of MAHs limits the cases of under-reporting and shortages of MTI drugs would obviously be reported to the ANSM by health professionals or patients otherwise. Third, the data relating to effective and predicted drug shortages may not reflect the effective short supplies, thus limiting the clinical interpretations of the present results. Fourth, reporting effective or predictive shortages to ANSM is required. There will indeed be cases where the risk of shortage will not become a short supply, but these two situations both reflect a production problem and may lead to short supply.

Strengths of the present study include the analysis of a national reporting system over a 7-year period. This is the first study to analyse the issue of drug shortages in France. Trends of drug shortages were described according to pharmaceutical products and INN drugs, allowing a more detailed description and interpretation of drug shortages and their causes.

Reporting of drug shortages has been required to be standardised between all European member States as well as coordination of legal and organisational strategies.3 4 A European collaboration (Task Force) set up by the European Medicine Agency is ongoing since 2016, to provide support and advice to tackle disruptions in supply of medicines and ensure their continued availability.32 According to Woodcock et al,33 it would be useful to stimulate investments to increase industrial production capacities, in particular for injectable drugs. Moreover, data of the financial impact of drug shortages are lacking. A calculation of the opportunity cost would be an argument to stimulate these investments.

Conclusion

Shortage reports of MTI drugs were frequent and increasing over the 2012 to 2018 period in France. Preventive measures, including contingency plans, should particularly target old drugs, injectables, anti-infectives, nervous system, cardiovascular system drugs as well as antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents. The issue of drug shortages goes beyond national concerns. Many drugs reported on shortages being granted by a European marketing authorisation. Even if the characteristics of drugs and reasons of shortages found in the present study are likely to be generalised to Europe, further studies are needed to address drug shortages at the European level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the drug shortages team and the surveillance division of the French National Agency for Medicine and Health Product Safety. They would also like to thank Natacha Marpillat as medical writer, as well as the professors’ team of Strasbourg Faculty of Pharmacy.

Footnotes

Contributors: AB contributed to data collection and data analysis. PM designed the project. SI, CRC and PM contributed to methods of the study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. Data were reported from the pharmaceutical companies and confidential.

References

- 1.Gray A, Manasse HR. Shortages of medicines: a complex global challenge. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:158-A 10.2471/BLT.11.101303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox ER, Sweet BV, Jensen V. Drug shortages: a complex health care crisis. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:361–73. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogaert P, Bochenek T, Prokop A, et al. . A qualitative approach to a better understanding of the problems underlying drug shortages, as viewed from Belgian, French and the European Union's perspectives. PLoS One 2015;10:e0125691 10.1371/journal.pone.0125691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauwels K, Huys I, Casteels M, et al. . Drug shortages in European countries: a trade-off between market attractiveness and cost containment? BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:438 10.1186/1472-6963-14-438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang C, Wu L, Cai W, et al. . Current situation, determinants, and solutions to drug shortages in Shaanxi Province, China: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165183 10.1371/journal.pone.0165183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris S. Medicine shortages in Australia - what are we doing about them? Aust Prescr 2018;41:136–7. 10.18773/austprescr.2018.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauters T, Claus BO, Norga K, et al. . Chemotherapy drug shortages in paediatric oncology: a 14-year single-centre experience in Belgium. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2016;22:766–70. 10.1177/1078155215610915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Meeting report: technical definitions of shortages and stock outs of medicines and vaccines 2016.

- 9.Rider AE, Templet DJ, Daley MJ, et al. . Clinical dilemmas and a review of strategies to manage drug shortages. J Pharm Pract 2013;26:183–91. 10.1177/0897190013482332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin M, Kotis D, Thomson K, et al. . Effects on patient care caused by drug shortages: a survey. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19:783–8. 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.9.783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox ER, Tyler LS. Potential association between drug shortages and high-cost medications. Pharmacotherapy 2017;37:36–42. 10.1002/phar.1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heiskanen K, Ahonen R, Kanerva R, et al. . The reasons behind medicine shortages from the perspective of pharmaceutical companies and pharmaceutical wholesalers in Finland. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179479 10.1371/journal.pone.0179479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Weerdt E, Simoens S, Hombroeckx L, et al. . Causes of drug shortages in the legal pharmaceutical framework. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2015;71:251–8. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decree 2012-1096 of September 2012 on the supply of medicines for human use Official Journal of the French Republic of 30th September 2012.

- 15.Act No 2016-41 of the 26th January 2016 on the modernization of the French healthcare system Official Journal of the French Republic of 27th January 2016.

- 16.Ministerial order of July 27th 2016 listing the therapeutic classes comprizing medicinal products of major therapeutic interest mentioned in article L. 5121-31 of the public health code.

- 17.Bocquet F, Degrassat-Théas A, Peigné J, et al. . The new regulatory tools of the 2016 health law to fight drug shortages in France. Health Policy 2017;121:471–6. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith MM, Gross AE, Sutton SH, et al. . The impact of anti-infective drug shortages on hospitals in the United States: trends and causes. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:684–91. 10.1093/cid/cir954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawley KL, Mazer-Amirshahi M, Zocchi MS, et al. . Longitudinal trends in U.S. drug shortages for medications used in emergency departments (2001-2014). Acad Emerg Med 2016;23:63–9. 10.1111/acem.12838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazer-Amirshahi M, Goyal M, Umar SA, et al. . U.S. drug shortages for medications used in adult critical care (2001-2016). J Crit Care 2017;41:283–8. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazer-Amirshahi M, Pourmand A, Singer S, et al. . Critical drug shortages: implications for emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:704–11. 10.1111/acem.12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pauwels K, Simoens S, Casteels M, et al. . Insights into European drug shortages: a survey of hospital pharmacists. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119322 10.1371/journal.pone.0119322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology ATC/DDC index, 2018. Available: www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

- 24.French Agency of Medicine and Health Product Safety : annual activity report Available: https://www.ansm.sante.fr/var/ansm_site/storage/original/application/8c5a443c987ce404048ed5af9d1b73cc.pdf

- 25.Drug shortages statistics Available: https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/shortage-resources/drug-shortages-statistics

- 26.Quadri F, Mazer-Amirshahi M, Fox ER, et al. . Antibacterial drug shortages from 2001 to 2013: implications for clinical practice. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1737–42. 10.1093/cid/civ201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons HM, Schmidt S, Karnad AB, et al. . Association between the number of suppliers for critical antineoplastics and drug shortages: implications for future drug shortages and treatment. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:e289–98. 10.1200/JOP.2015.007237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gogineni K, Shuman KL, Emanuel EJ. Survey of oncologists about shortages of cancer drugs. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2463–4. 10.1056/NEJMc1307379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.French national agency of medicine and health product safety. Available: www.valsartan-info.fr

- 30.Reed BN, Fox ER, Konig M, et al. . The impact of drug shortages on patients with cardiovascular disease: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Am Heart J 2016;175:130–41. 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postma DJ, De Smet PAGM, Gispen-de Wied CC, et al. . Drug shortages from the perspectives of authorities and pharmacy practice in the Netherlands: an observational study. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:1243 10.3389/fphar.2018.01243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.European Medicine Agency Towards improving the availability of medicines in the EU, 2018. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/press-release/towards-improving-availability-medicines-eu_en.pdf

- 33.Woodcock J, Wosinska M. Economic and technological drivers of generic sterile injectable drug shortages. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013;93:170–6. 10.1038/clpt.2012.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034033supp001.pdf (82.2KB, pdf)