Abstract

Selective sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2Is) are oral hypoglycemic medications utilized increasingly in the medical management of hyperglycemia among persons with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Despite favorable effects on cardiovascular events, specific SGLT2Is have been associated with an increased risk for atypical fracture and amputation in subgroups of the T2D population, a population that already has a higher risk for typical fragility fractures than the general population. To better understand the effect of SGLT2 blockade on skeletal integrity, independent of diabetes and its co-morbidities, we utilized the “Jimbee” mouse model of slc5a2 gene mutation to investigate the impact of lifelong SGLT2 loss-of-function on metabolic and skeletal phenotype. Jimbee mice maintained normal glucose homeostasis, but exhibited chronic polyuria, glucosuria and hypercalciuria. The Jimbee mutation negatively impacted appendicular growth of the femur and resulted in lower tissue mineral density of both cortical and trabecular bone of the femur mid-shaft and distal femur metaphysis, respectively. Several components of the Jimbee phenotype were characteristic only of male mice compared with female mice, including reductions: in body weight; in cortical area of the mid-shaft; and in trabecular thickness within the metaphysis. Despite these decrements, the strength of femur diaphysis in bending (cortical bone), which increased with age, and the strength of L6 vertebra in compression (primarily trabecular bone), which decreased with age, were not affected by the mutation. Moreover, the age-related decline in bone toughness was less for Jimbee mice, compared with control mice, such that by 49-50 weeks of age, Jimbee mice had significantly tougher femurs in bending than C57BL/6J mice. These results suggest that chronic blockade of SGLT2 in this model reduces the mineralization of bone but does not reduce its fracture resistance.

Keywords: fracture, cortical bone, trabecular bone, bone microarchitecture, proximal tubule, Jimbee mouse, canagliflozin

1. Introduction

Selective sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2Is) are anti-hyperglycemic medications that lower plasma glucose by inhibiting glucose reabsorption from the renal glomerular filtrate, thereby promoting excess glucose excretion in the urine (1). These drugs specifically inhibit the uptake of glucose and sodium (Na+) within the early proximal convoluted tubule by blocking the SGLT2 co-transporter (2). In this way, they induce an insulin-independent lowering of blood glucose without increasing risk for hypoglycemia but rather with an increasing potential for weight reduction (i.e., chronic calorie loss) (1). Accompanying cardiovascular and renal benefits have also been documented in patients treated with specific SGLT2Is (3-5). Therefore, consensus guidelines of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes recommend SGLT2Is as a second-line therapy for sub-optimally controlled patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), and particularly those with the co-morbidities of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, obesity, or elevated hypoglycemia risk (6). SGLT2Is are also being evaluated for use as adjuvant therapy for the treatment of type 1 diabetes (T1D) (7-11) and obesity (12).

The chronic glucosuria of the diabetic state augmented by SGLT2I therapy, however, would be expected to exacerbate diabetic hypercalciuria associated with ongoing osmotic diuresis (13-15). Moreover, among certain at-risk groups of T2D patients, including those with renal failure, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular diseases or neuropathy, specific SGLT2I medications appear to be associated with an increased risk for fracture or lower limb amputation (4, 16). Therefore, a better understanding of the overall impact of long-term SGLT2 inhibition on skeletal integrity is highly relevant, as utilization of this drug class continues to expand.

In humans, mutations in SGLT2 can result in the disorder of familial renal glucosuria (OMIM 233100) (2, 17), which is characterized by normal glucose tolerance, but persistent glucosuria (17). Likewise, the “Jimbee” mouse carries an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced 19 base-pair deletion on chromosome 7 within exon 10 of the slc5a2 (sglt2) gene, generated on a C57BL/6J background. This mutation results in a premature stop codon within exon 10, leading to expected nonsense-mediated decay of the truncated mRNA, and absence of SGLT2 protein function (additional details can be found at https://mutagenetix.utsouthwestern.edu/phenotypic/phenotypic_rec.cfm?pk=598). Consistent with other slc5a2 loss-of-function mouse models (18, 19), these mice have been shown to exhibit normal serum glucose, but profound glycosuria, hypercalciuria and an osmotic diuresis, accompanied by polyphagia and polydipsia. As such, they provide a model of exaggerated urinary glucose, mineral and electrolyte loss fundamentally analogous to pharmacological inhibition of SGLT2 function via SGLT2I therapy, but present lifelong. To the best of our knowledge, the role of the sglt2 gene in the fracture resistance of bone has not been investigated. Therefore, we investigated the effect of this germline deletion of SGLT2 function on skeletal phenotype and bone mineral homeostasis in male and female Jimbee mice at two ages: 1) at skeletal maturity and 2) approaching middle age. We hypothesized that the bone of Jimbee mice would have less fracture resistance than the bone of wild-type mice because lifelong, excessive, renal excretion of sodium and calcium could decrease the mineralization of the bone matrix.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

Jimbee C57BL/6J-Slc5a2m1Btlr/Mmmh mice were initially identified in a screen of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea mutagenized mice as being susceptible to weight loss following administration of dextran sulfate sodium (Tomisato W, Brandl K, Murray A, Beutler B. Record for jimbee. MUTAGENETIX™, B. Beutler and colleagues, Center for the Genetics of Host Defense, UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX.). The Jimbee allele was created on a C57BL/6J background and has been continuously maintained on the same background. The absence of SGLT2 protein in kidney tissue of Jimbee mice was confirmed by Western Blot analysis. A similar, elevated level of glucosuria in Jimbee mice has been documented through seven generations of in-house Jimbee breeding (data not shown). Additional details regarding the Slc5a2 deletion of the Jimbee mutation, along with additional phenotypic characterization of this mutant mouse can be found at URL: https://mutagenetix.utsouthwestern.edu/phenotypic/phenotypic_rec.cfm?pk=598.

Cryopreserved sperm from homozygous Jimbee mice were used for in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) at the University of Missouri Mutant Mouse Resource and Research Center (MU-MMRRC, Columbia, MO). Heterozygous mice obtained from IVF-ET were crossed to generate homozygous Jimbee C57BL/6J-Slc5a2m1Btlr/Mmmh mice. Experimental Jimbee mice were obtained via homozygous x homozygous breeding. Two cohorts of mice were studied: 1) at 16-18 weeks of age (representing skeletal maturity), comprised of homozygous Jimbee mice produced at the University of Kentucky (UK); and 2) at 49-50 weeks of age (representing middle age), comprised of homozygous Jimbee mice initially received from MU-MMRRC at approximately 5 weeks of age, and thereafter maintained at UK until reaching 49-50 weeks of age. For background strain comparison, age- and sex-matched C57BL/6J mice were obtained directly from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) at the commencement of each study and then monitored simultaneously to achieve comparable ages. All mice were maintained in a 14-hour light (lights on at 0600 hours): 10-hour dark cycle (lights off at 2000 hours), and provided ad libitum access to food and water throughout the study. For the 16-18-week study, both Jimbee and C57BL/6J mice were monitored from weaning until reaching a final age of 16-18 weeks [C57BL/6J: n=10 female (F) + 10 male (M); Jimbee: n=12 F + 11 M]. For the 49-50 week study, both Jimbee and C57BL/6J mice were monitored from ~5 weeks of age until reaching a final age of 49-50 weeks [C57BL/6J: n=14 F + 12 M; Jimbee: n=19 F + 21 M]. For both cohorts, beginning at ~8-10 weeks of age and every ~8 weeks thereafter, body mass was measured and urine was collected (See figure details for specific time points). A third cohort (C57BL/6J and Jimbee male mice only; n=7-11 mice/group) at 24-27 weeks of age (~mid-point between cohorts 1 and 2) were utilized for a more detailed assessment of glucose tolerance, detailed below.

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Kentucky (#2015-2293).

2.2. Assessment of physiology and phenotype

For timed urine collections, mice were transferred to individual metabolic cages; and urine was collected over defined intervals (range = 5-18 hours, with shorter collection times needed for mice with polyuria). Total urine volume and collection times were recorded. Using an aliquot of each collection, urine calcium was measured using a calcium colorimetric assay (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO; #MAK022); and urine creatinine was measured using an enzymatic assay (Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL; Mouse Creatinine Assay Kit #80350). Calcium (CA) concentration was normalized to urine creatinine concentration, and reported as a urine calcium/creatinine ratio (uCA/Cr; μg/mg). Additionally, urine total daily calcium excretion was estimated as: [uCA (μg/mL) x urine volume (mL/hr) x 24 hr/day]/body mass (g) = μg/g/day.

At study end for each cohort, euthanasia involved isoflurane overdose followed by decapitation. Directly after decapitation, trunk blood (0.3 – 1 mL) was collected directly into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes on ice. Fresh, whole blood was used for measurement of glucose (AlphaTRAK 2, Veterinary Blood Glucose Monitoring System, Parsippany, NJ); 200 μl whole blood was transferred to tubes containing potassium EDTA (Microvette CV 300 K2E, Sarstedt AG & Co, Numbrecht, Germany). Plasma was prepared by centrifuging EDTA anti-coagulated blood at 1500 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Remaining whole blood was placed on ice for up to six hours before centrifugation at 10,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured in EDTA anti-coagulated whole blood. Serum bone biomarkers were assayed in serum. The left femur and L6 vertebrae were cleaned of soft tissue, immersed in phosphate buffered saline, and stored frozen (−80°C) until thawed for analysis. As a marker of glycemic control, HbA1c was determined using a mouse HbA1c whole blood assay (Crystal Chem; Elk Grove Village, IL, #80310). As a marker of bone formation, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) was measured using the Rat/Mouse P1NP Enzyme immunoassay (Immunodiagnostics Systems, Inc., Fountain Hills, AZ; #AC-33F1). As a marker of bone resorption, C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (CTX) were measured using the RatLAPs ELISA (Immunodiagnostics Systems, Inc., Fountain Hills, AZ; #AC-06F1). To provide an indirect measure of phosphate homeostasis, FGF-23 was measured using an FGF-23 ELISA (Kainos Laboratories, Inc., Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo; #CY-4000, Lot 830).

Using a separate cohort of both C57BL/6J and Jimbee male mice at age 24-27 weeks, intraperitoneal (ip) glucose tolerance testing (ipGTT) was completed during the final week of observation. For ipGTT, mice were weighed and then fasted for 6 hours with free access to water. Blood glucose was measured in the fasting state, using AlphaTRAK 2 Veterinary Blood Glucose Monitoring System (Parsippany, NJ). A volume of 20% glucose in sterile saline was then injected ip (1.5 mg/gm body weight) and blood glucose measurements were obtained at 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes following glucose injection. Glucose tolerance testing as well as “random” glucose measurements were performed in the afternoon beginning at approximately 1400 hours.

2.3. Assessment of Skeletal Microarchitecture

Following our previously published methods (20, 21), the distal femur metaphysis and mid-point of the femur diaphysis were scanned using ex vivo micro-computed tomography (Scanco μCT50, Scanco Medical AG, Brϋttisellen, Switzerland) and then evaluated to assess trabecular architecture (bone volume fraction, trabecular thickness, etc.), cortical structure (cortical thickness, moment of inertia, etc.), and tissue mineral density of each bone type. For both regions, the scanner settings were as follows: an isotropic voxel size of 6 μm, peak voltage of 70 kVp, tube current of 0.114 mA, integration time of 300 ms, sampling rate of 1160 acquisitions per 500 projections per 180° rotation, and a 0.1 mm aluminum filter. To segment bone tissue from air or marrow, we applied the manufacturer’s beam hardening correction (as part of the calibration to the hydroxyapatite phantom), Gaussian image noise filter (smoothing parameters: standard deviation of the distribution and weighting of neighboring pixels) for metaphysis (Sigma = 0.2 and Support =1) and diaphysis (Sigma = 0.8 and Support = 2), and global thresholds for trabecular bone (429.4 mgHA/cm3) and cortical bone (900.5 mgHA/cm3). Standard Scanco evaluation scripts were run on each region of interest to acquire the bone properties.

Additionally, the cranial-caudal axis of each L6 vertebral body (VB) was aligned with the long axis of tube holder and scanned while immersed in PBS using the μCT40 (Scanco Medical AG, Brϋttisellen, Switzerland). The scanner settings were the same as those used to image the long bone, but the isotropic voxel size was 12.0 μm (1024 samples per 1000 projections for an entire rotation). The region of interest (ROI) was defined as the trabecular bone between the cranial and caudal endplates and was manually contoured. The segmentation procedure (22) included the following settings: sigma= 0.8, support=1.0, and threshold range between 529.8 mgHA/cm3 and 2822.8 mgHA/cm3. As for the distal femur metaphysis, the Scanco script determined the micro-architectural properties within the L6 VB: trabecular number (Tb.N), thickness (Tb.Th), separation (Tb.Sp), connectivity (Conn.D), bone volume fraction (BV/TV), and structural model index (SMI).

2.4. Assessment of Bone Biomechanical Parameters

Following the μCT scans, each hydrated femur was loaded-to-failure at 3 mm/min in three-point bending using a bench-top, mechanical testing system (DynaMight 8800, Instron, Norwood, MA) to determine the stiffness, maximum force, post-yield displacement (PYD), and work-to-failure. Information on the test set-up, determination of the biomechanical properties, as well as the methods for calculating the material properties (modulus, yield stress, maximum bending stress, toughness) can be found in our previous publications (20, 21).

The strength of the L6 VB was determined by quasi-static testing in compression using the same mechanical testing system. Holding the spinous process of the L6 spine segment with forceps, the vertebral body was positioned between an upper stainless-steel compression platen (diameter = 2.0 mm) and lower stainless-steel platen sitting on a moment relief that ensures axial loading in the cranial-caudal direction. Upon applying a pre-load of 2.0 N, the position was checked by viewing the VB through a horizontally mounted digital SLR camera (Canon EOS 7D, Canon, Melvill, NY) equipped with a macro photo lens (Canon MP-E 65mm 1:2.8, set to 4X magnification and working distance of 43.2 mm). If the VB was under the center of the upper platen and the coronal plane was oriented left-to-right (anterior-posterior was front-to-back), the hydrated VB was loaded-to-failure at 3 mm/min. Otherwise, the bone was repositioned before starting the test. The force-displacement data was acquired at a sampling rate of 50 Hz from the load cell, which had a maximum capacity of 100 N, and the linear variable displacement transducer, which is attached to the actuator of the DynaMight, respectively. The VB strength was the peak compressive force endured by the L6 bone.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Longitudinal outcome variables of interest were measured at multiple time points for the 49-50-week group of mice: blood glucose, body mass, and urine CA/Cr (5 time points) as well as urine CA excretion rate (3 time points). For these four quantitative outcome variables, a three-way ANOVA with age (time point) as a repeated measure was performed.

The remaining outcomes of interest were measured for each mouse at time of death. For these quantitative variables, we obtained group-level means and standard deviations (SD), differentiated by age, sex, and genotype, before fitting full-factorial three-way ANOVA models. For outcomes whose overall ANOVA p-value was significant (less than 0.05), we re-fit the final ANOVA model for each outcome variable two times. First, we included all significant main effects and interactions. Next, for the subset of outcome variables for which genotype differences were detected, we performed an ANCOVA, adding an adjustment for body size. Relevant pairwise differences in the group-level least squares (LS) means were calculated in each case and reported with their respective standard error (SE) and p-values.

Statistically significant (S) differences were defined as p≤0.05 and qualified with an asterisk (S*) when 0.05<p≤0.1. Using the smaller effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.06) of the 2 key outcomes (urine CA/Cr and Tb.TMD) from our previous study comparing wild-type mice that received regular chow to wild-type mice receiving canagliflozin, and SGLT2 inhibitor drug (22), the effect size f in our sample size determination was 0.529 based on a published transformation (23). Using the G-Power effect size calculator (24), we needed 10-11 mice per group to detect significant effects using a three-way ANOVA with 1 covariate, a power of 0.95, and α of 0.05. Results for individual parameters are reported as mean ± SD unless otherwise specifically indicated in the text. Additional description of the data presented in tables and figures is provided in the corresponding table footnotes and figure legends.

3. Results

3.1. Growth phenotype

3.1.1. Body size:

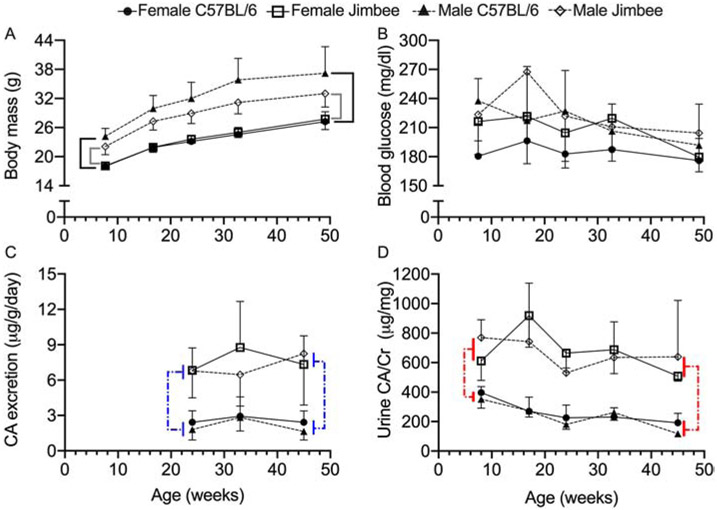

Longitudinal growth curves from the 49-50-week cohort (Figure 1A) demonstrate steady body weight gain in both C57BL/6J (control) and Jimbee males and females as the mice age. Male mice of both genotypes were significantly heavier throughout the study, compared with their female counterparts (p<0.0001 for Sex effect in Table 1). The presence of the Jimbee mutation, however, lessened the weight gain in male Jimbee mice, but not in female Jimbee mice (Figure 1A). Consequently, there was a significant age-by-genotype-by-sex interaction evident (Table 1; body weight). With respect to end-point measurements of body mass (16-18-wk and 49-50-wk cohorts), weight of the mice depended on genotype, sex, age, and the interaction between genotype and sex (Table 2) such that body mass of Jimbee male mice was 3.6 g lower (~10% lower) than the body mass of the C57BL/6J male mice with no difference between genotypes in the female mice (Table 3).

Figure 1: Weight gain, blood glucose, and urine calcium with aging, for each genotype.

Body mass (g) increased with age, with male mice weighing more than female mice within genotype (A). While non-fasting blood glucose depended on genotype, sex, and age, there were no specific group-level differences at each time point (B). Calcium excretion was higher for the Jimbee than for the C57BL/6J mice (C). Additionally, the urine calcium per creatinine ratio was higher for the Jimbee mice than for the control mice, regardless of sex and age (D). Brackets indicated a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in which solid lines compare genotypes within sex (A) and dashed lines compare genotypes (C, D). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Open symbols for Jimbee mice; closed symbols for C57BL/6J mice; and different symbols for female vs. male mice.

Table 1:

P-values for main effects and interaction effects on longitudinal measurements (as a function of age for the 49-50-week cohort only) as determined by three-way ANOVA (bold indicates p<0.05 and * indicates 0.05<p≤0.1). Main effects or interaction effects were not significant (NS) if p>0.1.

| Variable | Genotype | Sex | Age | Genotype x Sex |

Age x Sex |

Age x Genotype |

Age x Genotype x Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass (g) | 0.0166 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0045 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.0277 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dl) | 0.0005 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Urine CA excretion (μg/g/day) | <0.0001 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Urine CA/Cr1 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.0051 | NS | 0.0766* | 0.0336 | NS |

Since there were a few missing values, the p-values came from a mixed model instead of repeated measures ANOVA.

Table 2:

P-values for significant main effects and interaction effects on terminal measurements as determined by three-way ANOVA (bold indicates p<0.05 and * indicates 0.05<p≤0.1). Otherwise, main effects or interaction effects were not significant (NS).

| Property | Genotype | Sex | Age | Genotype x Sex |

Genotype x Age |

Sex x Age |

Genotype x Sex x Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | |||||||

| Body mass | 0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | NS | NS | NS |

| Femur Length | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | NS | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Biomarkers | |||||||

| HbA1c | 0.048 | NS | <0.0001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| P1NP | 0.005 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.060* | <0.0001 | NS |

| RatLAPs | NS | 0.083* | <0.0001 | NS | 0.010* | NS | NS |

| FGF23 | NS | 0.069* | <0.0001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Cortical Bone | |||||||

| Ma.V | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Ct.Ar | 0.002 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.041 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Tt.Ar | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | 0.001 | NS |

| Imin | NS | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.091* | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Ct.Th | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | 0.053* | NS |

| Ct.TMD | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.004 | NS | NS |

| Ct.Po | 0.066* | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Trabecular Bone | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | 0.0004 | NS |

| Tb.BV/TV | 0.048 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.003 | <0.0001 | NS |

| Conn.D | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | 0.001 | NS |

| SMI | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Tb.N | 0.024 | 0.0005 | <0.0001 | 0.030 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Tb.Th | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.067* | <0.0001 | NS |

| Tb.Sp Tb.TMD | <0.0001 | 0.0007 | <0.0001 | 0.090* | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Biomechanical | 0.088* | NS | <0.0001 | NS | NS | 0.100* | NS |

| Stiffness | NS | 0.002 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | 0.0002 | NS |

| Max Force | NS | NS | <0.0001 | NS | 0.016 | 0.092* | NS |

| PYD | NS | 0.088* | <0.0001 | NS | 0.006 | NS | NS |

| Work-to-fail | NS | <0.0001 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Yield Strength | NS | <0.0001 | 0.041 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Bend Strength | NS | <0.0001 | NS | NS | 0.017 | 0.025 | NS |

| Modulus | NS | NS | <0.0001 | NS | 0.009 | NS | NS |

| Toughness | NS | NS | <0.0001 | NS | 0.016 | NS | NS |

| PY Toughness | |||||||

| L6 VB | |||||||

| BV/TV | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | NS | 0.001 | NS |

| Conn.D | 0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | NS | NS |

| SMI | NS | NS | 0.002 | NS | NS | 0.001 | 0.095* |

| Tb.N | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.029 | NS | NS | NS |

| Tb.Th | 0.002 | 0.071* | 0.045 | NS | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Tb.Sp | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.016 | NS | NS | NS |

| Tb.TMD | <0.0001 | NS | <0.0001 | 0.026 | 0.035 | <0.0001 | NS |

| VB Strength | NS | 0.062* | <0.0001 | NS | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

Table 3.

Mean (SD) of terminal measurements from phenotype and serum/urine assays for each group along with relevant pairwise differences, as the least squares (LS) means [with Standard Error (SE)], for significant main effects (S when p<0.05 and S* when 0.05<p≤0.1) – Genotype (G), Age group (A), and Sex (S) – as well as significant interaction effects (GxS, GxA, and SxA). Negative value means Jimbee is higher than C57BL/6J or 49-50-weeks is higher than 16-18-weeks or Male is higher than Female. Main effects or interaction effects were not significant (NS) if p>0.1.

| Variable | Units | FEMALE | Genotype Effect1 |

Age Effect2 |

Genotype Effect within Sex3 Effect within Age (Young Old)4 |

Age Effect within Sex5 Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J Jimbee)6 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=12) |

C57BL/6J (n=13) |

Jimbee (n=19) |

||||||

| Body mass | g | 21.8 (1.3) | 21.4 (1.1) | 27.2 (2.0) | 27.1 (1.9) | S | −5.7 [0.53] | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Femur length | mm | 14.82 (0.19) | 14.63 (0.25) | 15.62 (0.16) | 15.35 (0.32) | +0.229 [0.047] | S | NS, (NS) | −0.755 [0.066], (NS) |

| HbA1c | % | 3.1 (0.4) | 3.9 (0.1) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.4 (0.8) | −0.32 [0.17]* | −2.6 [0.2] | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| P1NP | ng/mL | 21.1 (6.1) | 28.2 (5.3) | 19.6 (3.6) | 22.8 (4.1) | −3.0 [1.2] | S | NS, (S*) | +3.6 [1.7], (NS) |

| RatLAPs | ng/mL | 22.1 (15.3) | 15.8 (3.9) | 10.9 (3.1) | 11.7 (3.5) | NS | +6.9 [1.3] | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| FGF23 | pg/mL | 9.1 (3.9) | 7.6 (2.6) | 19.4 (12.3) | 17.5 (8.2) | NS | −8.4 [1.2] | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| MALE | Genotype Effect |

Age Effect |

Genotype Effect within Sex Effect within Age (Young Old) |

Age Effect within Sex Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J Jimbee) |

|||||

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=11) |

C57BL/6J (n=12) |

Jimbee (n=21) |

||||||

| Body mass | g | 30.5 (2.0) | 27.8 (1.7) | 37.2 (7.2) | 32.9 (3.2) | S | N/A9 | +3.6 [0.7], (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex within Genotype7 | −9.4 [0.8] | −6.0 [0.7] | |||||||

| Femur Length | mm | 15.27 (0.29) | 14.92 (0.22) | 15.25 (0.20) | 15.10 (0.21) | N/A | S | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex within age8 | −0.364 [0.073] | +0.296 [0.059] | |||||||

| HbA1c | % | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.1) | 6.1 (1.1) | 6.3 (1.3) | N/A* | N/A | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| P1NP | ng/mL | 35.2 (8.6) | 39.4 (6.6) | 24.5 (7.2) | 23.5 (6.2) | N/A | S | NS, (S*) | +13.9 [1.7], (NS) |

| Sex within age | −12.5 [1.8] | NS | |||||||

| RatLAPs | ng/mL | 21.0 (2.9) | 20.4 (4.0) | 13.6 (5.4) | 14.4 (7.0) | NS | N/A | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| FGF23 | pg/mL | 8.1 (1.9) | 6.3 (2.5) | 15.9 (6.4) | 14.0 (4.9) | NS | N/A | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

C57BL/6J LS means – Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks LS means – 49-50-weeks LS means.

female C57BL/6J LS means – female Jimbee LS means or male C57BL/6J LS means – male Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means or 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means – 49-50-weeks female LS means or 16-18-weeks male LS means – 49-50-weeks male LS means.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means or 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means – 49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

female C57BL/6J LS means – male C57BL/6J LS means or female Jimbee LS means – male Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means – 16-18-weeks male LS means or 49-50-weeks female LS mean – 49-50-weeks male LS means.

Not applicable (N/A) because genotype did not interact with sex and/or age and so the difference in the LS means is the same for females and males.

3.1.2. Bone length:

The overall axial length of the femur (determined from harvested specimens using calipers) also confirmed appendicular growth of C57BL/6J and Jimbee mice with advancing age (Table 2 and Table 3). However, femur length was consistently shorter in Jimbee mice compared to the control genotype by 229 μm (Table 3), and the age-related increase in length depended on sex (significant for female mice, Table 3). When adjusting for body size (ANCOVA using body mass), the pairwise difference of 190 μm (SE=48) between genotypes was significant (p=0.0001, Table S1).

3.1.3. Growth summary:

In total, genetic loss of SGLT2 contributed to: 1) a reduction in the length of the femur, irrespective of sex; and 2) an impact on body weight in male Jimbee mice exclusively, such that male Jimbee mice weighed less than male control mice from ~16 weeks to 50 weeks of age.

3.2. Metabolic phenotype

3.2.1. Glycemic control:

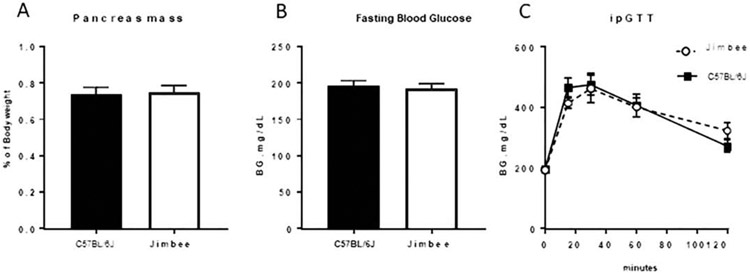

HbA1c values depended on genotype and age in the ANOVA model (Table 2). They were modestly higher in Jimbee mice compared with C57BL/6J mice, but this pairwise difference (0.32%) was not significant (p=0.063). After statistical adjustment for body size, HbA1c values were not different between genotypes (p=0.392, Table S1). Analyzing the 5 measurements of blood glucose concentration as the older cohort of mice aged, blood glucose depended on genotype, sex, and age but there were no significant interactions (Table 1). As such, there were no significant differences in blood glucose within each sex over time (Figure 1B). Additionally, examination of a separate cohort of male mice, 24-27 weeks of age (study midpoint), demonstrated no differences in pancreas mass, fasting blood glucose, or glucose tolerance between control and Jimbee mice at this age (Figure 2A, B, C, respectively).

Figure 2: Analysis of glucose homeostasis in male mice.

Pancreas weight normalized to body weight (A), as well as 6-hour fasting blood glucose levels (B) in male mice at 25 weeks of age did not differ between Jimbee and C57BL/6J mice. Additionally, no genotype differences in blood glucose levels during an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (ipGTT) were seen (C). Jimbee mice are represented by dashed lines (C). Data are presented as mean ± standard error (n=7-11 male mice/group).

Between the 2 age groups, the pairwise difference in HbA1c was 2.6%, being higher for the 49-50-week old mice. HbA1c was not different, however, between sexes (Table 3), and the higher HbA1c with age did not depend on genotype. Therefore, while HbA1c increased in both genotypes with advancing age, the difference in glycemic control between the genotypes was marginal.

3.2.2. Urine calcium excretion:

Consistent with pharmacologic SGLT2 inhibition [and with other SGLT2 mutant models (18)], urine output was significantly higher in both male and female Jimbee mice, compared to their control counterparts (Jimbee M: 176 ± 69 μl/hr; F: 125 ± 33 μl/hr. C57BL/6J M: 34 ± 12 μl/hr; F: 43 ± 18 μl/hr; p<0.0001 for both), and chronic glucosuria was confirmed qualitatively in Jimbee mice (sequential dipstick analysis). For Jimbee mice alone, urine output was also higher in male mice compared with female mice (p=0.004). As expected, all Jimbee mice also exhibited hypercalciuria (Figure 1C, 1D; Table 1); there were no significant differences in estimated daily CA excretion noted between the sexes (Table 1) nor over three time points (Figure 1C). Specifically, urine total daily calcium excretion was consistently higher in Jimbee mice across all time-points. This was also the case for urine CA/Cr ratio, although the ratio changed with age (Figure 1D) depending on the genotype (Table 1). In C57BL/6J mice, there was no difference in urine CA excretion (Figure 1C) or in urine CA/Cr between the sexes (Figure 1D, Table 1).

3.3. Bone biomarkers

3.3.1. P1NP:

When comparing the genotypes overall, P1NP values were also significantly higher in Jimbee mice compared with controls (pairwise difference of 3.0 ng/mL; Table 3). P1NP decreased with age, more so in male than in female mice (Table 3). When adjusting for body size (ANCOVA), P1NP still depended on genotype, sex, and age (Table S1). The pairwise difference was 3.5 ng/mL (SE=1.3), being higher in Jimbee mice (p=0.01).

3.3.2. RatLAPs:

RatLAPs values (C-terminal of the telopeptide of collagen I) were not significantly different between C57BL/6J and Jimbee mice (Table 3). RatLAPs values were also not significantly different between males and females (Table 3). However, RatLAPs values, indicative of bone resorption, decreased with aging, when comparing the 16-18 week vs. the 49-50 week cohorts (Table 3).

3.3.3. FGF23:

FGF23 values did not depend on the genotype or sex of the animal (Table 2). However, FGF23 increased significantly with aging, when holding sex and genotype of the mice constant (8.4 pg/mL higher for 49-50 week cohort; Table 3).

3.4. Skeletal phenotype

3.4.1. μCT Evaluation of Femur Diaphysis (Cortical Bone):

3.4.1.1. Effects of slc5a2 mutation on cortical bone:

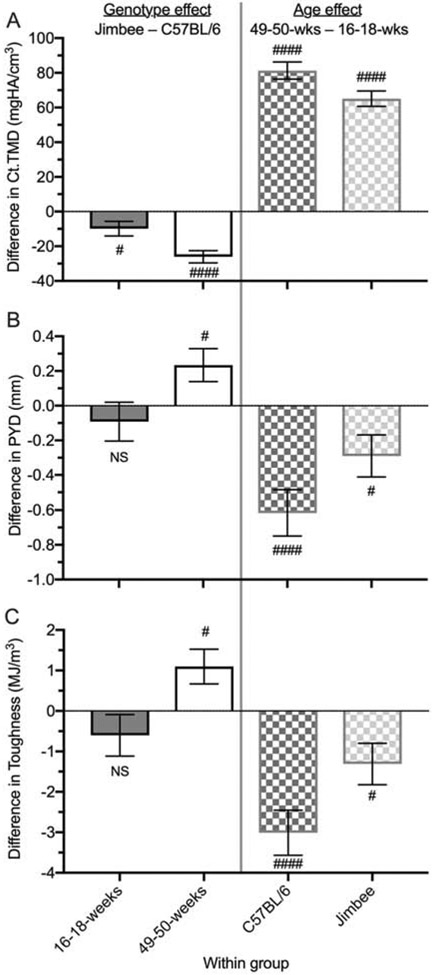

The Jimbee mutation significantly affected cortical area (Ct.Ar), cortical thickness (Ct.Th), and cortical tissue mineral density (Ct.TMD) (Table 2). When adjusted for the difference in body size between mice (Table S1), Ct.Ar was no longer significantly dependent on genotype. However, the genotype-specific decrease in Ct.TMD persisted regardless of sex and age group: by 9.9 mgHA/cm3 for 16-18-weeks and by 26.1 mgHA/cm3 for 49-50-weeks on average (Figure 3A). When adjusting for body size, Ct.Th was 4 μm less (SE=2) for Jimbee than for C57BL/6J mice (p=0.015), compared to a 6 μm reduction without adjusting (Table 4), while holding sex and age of mice constant.

Figure 3: Pairwise differences (± standard error) between genotypes within age group (left panels) or between age groups within genotype (right panels).

Cortical TMD was lower for Jimbee than for control mice for both age groups, and it increased with age for both genotypes (A). The difference in post-yield deflection between the genotypes was not significant (NS) at 16-18 weeks, but was higher for the Jimbee mice at 49-50 weeks (B). PYD decreased with age for both genotypes (C). As with PYD, toughness also decreased with age, but the reduction was less pronounced for the Jimbee mice compared to the C57BL/6J mice (C). # p<0.05 and #### p<0.0001 for either C57BL/6J vs. Jimbee (left panels) or 16-18-weeks vs. 49-50-weeks (right panels).

Table 4.

Mean (SD) of terminal measurements from μCT evaluations of the femur mid-shaft (cortical) for each group along with relevant pairwise differences, as the LS means [with SE], for significant main effects (S when p<0.05 and S* when 0.05<p≤0.1) – Genotype (G), Age group (A), and Sex (S) – as well as significant interaction effects (GxS, GxA, and SxA). Negative value means Jimbee is higher than C57BL/6J or 49-50-weeks is higher than 16-18-weeks or Male is higher than Female. Main effects or interaction effects were not significant (NS) if p>0.1.

| Variable | Units | FEMALE | Genotype Effect1 |

Age Effect2 |

Genotype Effect within Sex3 Effect within Age (Young Old)4 |

Age Effect within Sex5 Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J Jimbee)6 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=12) |

C57BL/6J (n=13) |

Jimbee (n=19) |

||||||

| Ma.V | mm3 | 1.82 (0.15) | 1.78 (0.10) | 2.04 (0.12) | 2.17 (0.20) | NS | −0.33 [0.06] | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Ct.Ar | mm2 | 0.69 (0.04) | 0.67 (0.04) | 0.77 (0.04) | 0.77 (0.07) | S | NS | NS, (NS) | −0.10 [0.02], (NS) |

| Tt.Ar | mm2 | 1.68 (0.11) | 1.64 (0.09) | 1.89 (0.09) | 1.95 (0.16) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | −0.27 [0.04], (NS) |

| Imin | mm4 | 0.102 (0.010) | 0.096 (0.012) | 0.132 (0.011) | 0.138 (0.021) | NS | S | S*, (NS) | −0.037 [0.006], (NS) |

| Ct.Th | mm | 0.158 (0.006) | 0.153 (0.006) | 0.173 (0.007) | 0.169 (0.009) | +0.006 [0.002] | −0.013 [0.002] | NS, (NS) | S*, (NS) |

| Ct.TMD | mgHA/cm3 | 1230.6 (11.6) | 1224.1 (13.1) | 1311.4 (15.1) | 1286.8 (14.2) | S | S | NS, (+10.0 [4.0] +25.9 [3.3]) | NS, (−80.6 [3.9] −64.7 [3.4]) |

| Ct.Po | % | 0.33 (0.11) | 0.39 (0.12) | 0.15 (0.07) | 0.18 (0.11) | S* | S | NS, (NS) | +0.20 [0.08]) |

| MALE | Genotype Effect |

Age Effect |

Genotype Effect within Sex, Effect within Age (Young, Old) |

Age Effect within Sex, Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J, Jimbee) |

|||||

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=11) |

C57BL/6J (n=12) |

Jimbee (n=21) |

||||||

| Ma.V | mm3 | 2.08 (0.74) | 2.30 (0.26) | 2.49 (0.32) | 2.55 (0.23) | NS | N/A10 | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex effect7 | −0.41 [0.06] | ||||||||

| Ct.Ar | mm2 | 0.89 (0.05) | 0.81 (0.07) | 0.80 (0.07) | 0.76 (0.06) | S | NS | +0.06 [0.02], (NS) | +0.07 [0.02], (NS) |

| Sex within Genotype8 | −0.11 [0.02] | −0.07 [0.02] | |||||||

| Sex within Age9 | −0.17 [0.02] | NS | |||||||

| Tt.Ar | mm2 | 2.13 (0.14) | 2.06 (0.20) | 2.16 (0.23) | 2.15 (0.15) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex within Age | −0.44 [0.05] | −0.23 [0.04] | |||||||

| Imin | mm4 | 0.162 (0.025) | 0.141 (0.028) | 0.154 (0.029) | 0.147 (0.019) | NS | S | S*, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex within Age | −0.052 [0.006] | −0.014 [0.005] | |||||||

| Ct.Th | mm | 0.153 (0.005) | 0.144 (0.005) | 0.162 (0.010) | 0.154 (0.009) | N/A | N/A | NS, (NS) | S*, (NS) |

| Sex effect | +0.011 [0.002] | ||||||||

| Ct.TMD | mgHA/cm3 | 1210.6 (6.9) | 1197.0 (8.1) | 1291.2 (15.0) | 1263.8 (14.4) | S | S | NS, (N/A) | NS, (N/A) |

| Sex effect | +22.6 [2.5] | ||||||||

| Ct.Po | % | 0.92 (0.18) | 1.22 (0.63) | 0.35 (0.32) | 0.36 (0.28) | S* | S | NS, (NS) | +0.73 [0.08], (NS) |

| Sex within Age | −0.72 [0.09] | −0.18 [0.07] | |||||||

C57BL/6J LS means – Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks LS means – 49-50-weeks LS means.

female C57BL/6J LS means – female Jimbee LS means or male C57BL/6J LS means –male Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means or 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means −49-50-weeks female LS means or 16-18-weeks male LS means – 49-50-weeks LS male mean.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J mean – 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means or 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means −49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

female LS means – male LS means.

female C57BL/6J LS means – male C57BL/6J LS means or female Jimbee LS means – male Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means – 16-18-weeks male LS means or 49-50-weeks female LS means – 49-50-weeks male LS means.

Not applicable (N/A) because genotype did not interact with sex and/or age and so the difference in the LS means is the same for females and males.

3.4.1.2. Effects of age on cortical bone:

The cortical bone phenotype was also dependent on the age of both C57BL/6J and Jimbee mice (Table 2). With respect to age-related differences, the medullary volume (Ma.V), total area (Tt.Ar: female only), minimum principal component of the moment of inertia (Imin: females only), Ct.Th, and Ct.TMD (more so for control than for Jimbee mice) were all significantly higher in the 49-50 week mice, compared with the 16-18 week mice (Table 4). Ct.Ar was also higher in 49-50 week female mice, compared with the 16-18 week mice; however, for male mice Ct.Ar decreased with aging (Table 4). Cortical porosity was significantly less for the 49-50 week mice compared to 16-18 week, but the difference depended on sex (Table 4).

3.4.1.3. Effects of sex on cortical bone:

With respect to sex-related differences, the femur diaphysis of male mice had significantly higher MaV, Ct.Ar (depended on genotype), Tt.Ar (depended on age group), Imin (depended on age group) and Ct.Po (depended on age group) along with significantly lower Ct.Th and Ct.TMD compared to female mice (Table 4). These differences were generally consistent with the sex-specific differences in body growth seen with aging, as detailed above (Figure 1A).

3.4.2. μCT Evaluation of Distal Femur Metaphysis (Trabecular Bone):

3.4.2.1. Effects of slc5a2 mutation on trabecular bone:

Compared with C57BL/6J mice, those mice carrying the Jimbee mutation also demonstrated lower trabecular tissue mineral density (Tb.TMD) (Table 5). Connectivity density (Conn.D) was comparatively higher in Jimbee mice in the younger cohort (Table 5), but not different between genotypes in the 49-50 week cohort (Table 5). Bone volume fraction (Tb.BV/TV) and the other trabecular architectural outcomes did not significantly depend on genotype (Table 2), though there was significant interaction between genotype and sex for trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) such that Tb.Th was lower in the Jimbee male mice than in the C57BL/6J male mice (Table 5). When adjusted for the difference in body size between mice, the Jimbee-associated reduction in Tb.TMD remained significant (Table S1) with a pairwise difference of 22.2 mgHA/cm3 (SE=4.0) between the genotypes.

Table 5.

Mean (SD) of terminal measurements from μCT evaluations of the distal femur metaphysis (trabecular) for each group along with relevant pairwise differences, as the LS means [with SE] for significant main effects (S for p<0.05 and S* indicates 0.05<p≤0.1) – Genotype (G), Age group (A), and Sex (S) – as well as significant interaction effects (GxS, GxA, and SxA). Negative value means Jimbee is higher than C57BL/6J or 49-50-weeks is higher than 16-18-weeks or Male is higher than Female. Main effects or interaction effects were not significant (NS) if p>0.1.

| FEMALE | Genotype effect1 |

Age effect2 |

Genotype Effect within Sex3 Effect within Age (Young Old)4 |

Age Effect within Sex5 Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J Jimbee)6 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| Variable | Units | C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=12) |

C57BL/6J (n=13) |

Jimbee (n=19) |

||||

| Tb.BV/TV | --- | 0.062 (0.012) | 0.066 (0.011) | 0.024 (0.010) | 0.022 (0.006) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | +0.041 [0.005], (NS) |

| Conn.D | mm−3 | 106.4 (22.3) | 120.7 (23.9) | 18.1 (15.1) | 15.6 (6.6) | S | S | NS, (−22.9 [7.6] NS) | +96.4 [6.9], (+130.8 [7.5] +155.7 [6.5]) |

| SMI | --- | 2.55 (0.17) | 2.49 (0.14) | 2.98 (0.39) | 3.02 (0.22) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | −0.49 [0.09], (NS) |

| Tb.N | mm−1 | 3.39 (0.32) | 3.50 (0.31) | 1.98 (0.18) | 1.89 (0.18) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | +1.52 [0.09], (NS) |

| Tb.Th | mm | 0.040 (0.003) | 0.039 (0.002) | 0.049 (0.006) | 0.049 (0.005) | S | S | NS, (NS) | −0.010 [0.001], (NS) |

| Tb.Sp | mm | 0.30 (0.03) | 0.29 (0.02) | 0.51 (0.05) | 0.53 (0.05) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | −0.23 [0.01], (NS) |

| Tb.TMD | mgHA/cm3 | 930.8 (16.3) | 911.0 (7.9) | 1005.2 (31.6) | 993.6 (22.2) | +21.4 [3.5] | S | S*, (NS) | −79.4 [3.5], (NS) |

| MALE | Genotype effect |

Age effect |

Genotype Effect within Sex Effect within Age (Young, Old) |

Age Effect within Sex Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J, Jimbee) |

|||||

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=11) |

C57BL/6J (n=12) |

Jimbee (n=21) |

||||||

| Tb.BV/TV | --- | 0.186 (0.016) | 0.173 (0.021) | 0.085 (0.022) | 0.085 (0.031) | NS | S | S*, (NS) | +0.094 [0.005], (NS) |

| Sex within Age 7 | −0.115 [0.006] | −0.062 [0.005] | |||||||

| Conn.D | mm−3 | 239.6 (26.7) | 271.5 (46.5) | 66.2 (17.5) | 65.0 (28.7) | S | S | NS, (N/A9) | +190.1 [7.0], (N/A) |

| Sex within Age | −142.6 [7.6] | −48.9 [6.2] | |||||||

| SMI | --- | 1.33 (0.22) | 1.29 (0.25) | 2.39 (0.49) | 2.17 (0.47) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | −0.94 [0.09], (NS) |

| Sex within Age | +1.21 [0.10] | +0.76 [0.08] | |||||||

| Tb.N | mm−1 | 5.41 (0.29) | 5.40 (0.44) | 3.42 (0.26) | 3.21 (0.49) | NS | S | S*, (NS) | +2.12 [0.09], (NS) |

| Sex within Age | −1.96 [0.10] | −1.36 [0.08] | |||||||

| Tb.Th | mm | 0.050 (0.004) | 0.043 (0.003) | 0.050 (0.006) | 0.048 (0.005) | S* | S | +0.004 [0.001], (NS) | −0.003 [0.001]*, (NS) |

| Sex in Geno.8 | −0.005 [0.001] | NS | |||||||

| Sex within Age | −0.007 [0.001] | NS | |||||||

| Tb.Sp | mm | 0.19 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.01) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.06) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | −0.12 [0.01], (NS) |

| Sex within Age | +0.10 [0.01] | +0.21 [0.01] | |||||||

| Tb.TMD | mgHA/cm3 | 942.0 (9.4) | 914.5 (9.8) | 981.3 (14.3) | 953.0 (14.5) | N/A | S | S*, (NS) | −38.1 [5.3], (NS) |

| Sex within Age | NS | +34.2 [5.0] | |||||||

C57BL/6J LS means –Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks LS means – 49-50-weeks LS means.

female C57BL/6J LS means – female Jimbee LS means or male C57BL/6J LS means – male Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means or 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means −49-50-weeks female LS means or 16-18-weeks male LS means – 49-50-weeks male LS means.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means or 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means – 49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means – 16-18-weeks male LS means or 49-50-weeks female LS mean – 49-50-weeks male LS means.

female C57BL/6J LS means – male C57BL/6J LS means or female Jimbee LS means – male Jimbee LS means.

Not applicable (N/A) because genotype did not interact with sex and/or age and so the difference in the LS means is the same for females and males.

3.4.2.2. Effects of age on trabecular bone:

As with cortical bone, the trabecular bone phenotype also depended on the age of mice (Table 2). Specifically, lower Tb.BV/TV, Conn.D and trabecular number (Tb.N), along with higher structural model index (SMI, in which 0 indicates plate-like structure and 3 indicates rod-like structure), Tb.Th (more pronounced in females), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) and Tb.TMD were seen in the older cohort, compared to the younger cohort (Table 5).

3.4.2.3. Effects of sex on trabecular bone:

Differences in trabecular bone phenotype were also evident when comparing females vs. males overall (Table 5); male mice exhibited significantly higher Tb.BV/TV, Conn.D, and Tb.N within each age group. The higher Tb.Th was only significant for 16-18-week group. SMI and Tb.Sp were both lower for the male than for the female mice, regardless of the age group. These sex-related differences depended on the age of the mice (significant interaction: Sex by Age in Table 2).

3.4.3. Biomechanical testing:

3.4.3.1. Effects of slc5a2 mutation on mechanical properties:

When comparing the mechanical properties of the femur mid-diaphysis between the two genotypes (while accounting for age and sex in the ANOVA model) mice carrying the Jimbee mutation did not exhibit significantly different strength measurements (Table 2). However, there was a significant interaction between genotype and age for the biomechanical properties related to brittleness (i.e., plastic properties), namely post-yield deflection (PYD), toughness, and post-yield (PY) toughness. Contrary to our stated hypothesis, these properties were higher for the Jimbee than for the control mice at 49-50-weeks of age only (Table 6). When adjusting for body size in an ANCOVA (Table S1), the interaction between genotype and age remained significant, suggesting that Jimbee mice are protected from the age-related increase in brittleness (Figure 3B) and decline in toughness (Figure 3C) seen in C57BL/6J mice.

Table 6.

Mean (SD) of terminal measurements from three-point bending tests of the femur mid-shaft (cortical) for each group along with relevant pairwise differences, as the LS means [with SE] for significant main effects (S when p<0.05 and S* when 0.05<p≤0.1) – Genotype (G), Age group (A), and Sex (S) – as well as significant interaction effects (GxS, GxA, and SxA). Negative value means Jimbee is higher than C57BL/6J or 49-50-weeks is higher than 16-18-weeks or Male is higher than Female. Main effects or interaction effects were not significant (NS) if p>0.1.

| Variable | Units | FEMALE | Genotype Effect1 |

Age Effect2 |

Genotype Effect within Sex3 Effect within Age (Young Old)4 |

Age Effect within Sex5 Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J Jimbee)6 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=12) |

C57BL/6J (n=13) |

Jimbee (n=19) |

||||||

| Stiffness | N/mm | 76.1 (18.1) | 81.1 (11.3) | 103.1 (12.4) | 96.3 (18.7) | S* | −14.9[3.1] | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Max Force | N | 14.7 (1.1) | 14.1 (1.1) | 18.4 (2.1) | 19.0 (2.9) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | −4.4 [0.71], (NS) |

| PYD | mm | 0.10 (0.44) | 0.72 (0.34) | 0.30 (0.12) | 0.42 (0.39) | NS | S | NS, (NS −0.20 [0.09]) | NS, (+0.55 [0.10] +0.20 [0.09]) |

| Work-to-fail | kJ/m2 | 11.05 (2.45) | 8.59 (2.75) | 6.17 (2.02) | 7.30 (4.06) | NS | S | NS, (+2.00 [0.98] - 1.68 [0.82]) | NS, (+4.24 [0.96] +1.56 [0.84]*) |

| Yield stress | MPa | 147.2 (11.2) | 152.4 (14.1) | 144.1 (19.3) | 142.7 (24.6) | NS | NS | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Max stress | MPa | 180.2 (8.1) | 179.3 (12.8) | 187.9 (20.0) | 188.2 (23.7) | NS | −8.1 [3.7] | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Modulus | GPa | 8.06 (2.06) | 9.13 (1.72) | 8.40 (1.30) | 7.51 (1.55) | NS | NS | NS, (NS +0.80 [0.39]) | NS, (+0.83 [0.44]* - 0.70 [0.40]*) |

| Toughness | MJ/m3 | 6.33 (1.60) | 5.04 (1.57) | 3.13 (0.95) | 3.70 (2.04) | NS | S | NS, (NS −0.97 [0.41]) | NS, (+2.70 [0.48] +0.99 [0.42]) |

| PY Toughness | MJ/m3 | 5.29 (1.60) | 4.07 (1.52) | 2.18 (0.94) | 2.59 (1.79) | NS | S | NS, (NS −0.78 [0.39]) | NS, (+2.60 [0.46] +1.08 [0.40]) |

| MALE | Genotype Effect |

Age Effect |

Genotype Effect within Sex Effect within Age (Young Old) |

Age Effect within Sex Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J Jimbee) |

|||||

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=11) |

C57BL/6J (n=12) |

Jimbee (n=21) |

||||||

| Stiffness | N/mm | 89.3 (13.2) | 81.2 (11.4) | 101.7 (12.6) | 90.5 (18.3) | S* | N/A9 | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Max Force | N | 19.0 (2.7) | 17.0 (2.5) | 18.7 (3.1) | 18.1 (3.2) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex within age7 | −3.6 [0.8] | NS | |||||||

| PYD | mm | 0.73 (0.21) | 0.72 (0.35) | 0.33 (0.22) | 0.60 (0.44) | NS | S | NS, (N/A) | NS, (N/A) |

| Work-to-fail | kJ/m2 | 11.99 (2.75) | 10.54 (4.08) | 6.40 (3.54) | 8.56 (2.90) | NS, (N/A) | NS, (N/A) | ||

| Yield stress | MPa | 120.6 (10.5) | 130.8 (12.1) | 127.0 (27.7) | 125.2 (21.8) | NS | NS | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex effect8 | +20.1 [3.8] | ||||||||

| Max stress | MPa | 160.0 (13.1) | 160.7 (17.1) | 168.2 (24.5) | 168.1 (21.9) | NS | N/A | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex effect | +19.7 [3.7] | ||||||||

| Modulus | GPa | 6.02 (1.35) | 6.36 (1.52) | 7.31 (1.76) | 6.60 (1.28) | NS | NS | NS, (N/A) | −0.79 [0.43]*, (N/A*) |

| Sex within age | +2.44 [0.47] | +0.98 [0.38] | |||||||

| Toughness | MJ/m3 | 5.34 (1.08) | 5.16 (1.80) | 3.15 (1.67) | 4.49 (1.50) | NS | S | NS, (N/A) | NS, (N/A) |

| PY Toughness | MJ/m3 | 4.29 (1.01) | 4.03 (1.76) | 2.19 (1.61) | 3.31 (1.58) | NS | S | NS, (N/A) | NS, (N/A) |

C57BL/6J LS means – Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks LS means – 49-50-weeks LS means.

female C57BL/6J LS means – female Jimbee LS means or male C57BL/6J LS means –male Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means or 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means −49-50-weeks female LS means or 16-18-weeks male LS means – 49-50-weeks LS male mean.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J mean – 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means or 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means −49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means – 16-18-weeks male LS means or Pooled 49-50-weeks female LS means – 49-50-weeks male LS means.

female LS means – male LS means.

Not applicable (N/A) because genotype did not interact with sex and/or age and so the difference in the LS means is the same for females and males.

3.4.3.2. Effects of age on mechanical properties:

With respect to age-related changes in the biomechanical properties, stiffness and maximum stress (p=0.03) were higher for the older mice than for the younger mice (Table 6). The maximum force endured by femur mid-shaft was higher with age only for the female mice (Table 6). Unlike the trabecular bone properties in which the age effect depended on sex, the age-related decrease in PYD, toughness, and PY toughness depended on genotype (i.e., sex was not a significant factor). These changes were more pronounced in the C57BL/6J mice than in the Jimbee mice (Table 6, Figure 3B & 3C). Work-to-failure was also lower for middle-age mice than for young mice with the pairwise difference in the LS means depending on the genotype (Table 6), not on sex (Table 2).

3.4.3.3. Effects of sex on mechanical properties:

The elastic properties tended to be different between the sexes, whereas the plastic properties (i.e., brittleness) did not depend on sex of the animal. The one exception was modulus, which did not vary with age, but was lower for male than for female mice at both young and middle age. Male mice also exhibited lower yield stress and maximum stress compared with female mice, pooling the 2 age groups (Table 6).

3.4.4. μCT Evaluation and compression testing of L6 Vertebral Body (Trabecular Bone):

3.4.4.1. Effects of slc5a2 mutation on vertebral bone:

With respect to the lumbar spine, there was a significant interaction between genotype and sex of the mouse for BV/TV (Table 2) such that there was more trabecular bone within the VB for female Jimbee mice but less trabecular bone within the VB for male Jimbee mice compared to wild-type mice while accounting for age-related differences (Table 7). Regardless of sex, the trabeculae were thinner by 2 μm in the Jimbee mice compared to the VBs in the C57BL/6 mice (Table 7). Specific to female Jimbee mice, Conn.D and Tb.N were higher while Tb.Sp and Tb.TMD were lower when accounting for age-related differences. There were no such differences in the male Jimbee mice compared to male wild-type mice. Overall, the Jimbee mutation did not affect the compressive strength of the VB (Table 7) perhaps because the lower Tb.TMD offset the higher BV/TV in the female Jimbee mice compared to the female C57BL/6 mice. The lower BV/TV (with no other differences) in the male Jimbee mice did not translate to a lower VB strength.

Table 7.

Mean (SD) of terminal measurements from μCT evaluations and compression tests of the L6 VB for each group along with relevant pairwise differences, as the LS means [with SE] for significant main effects (S for p<0.05 and * indicates 0.05<p≤0.1) – Genotype (G), Age group (A), and Sex (S) – as well as significant interaction effects (GxS, GxA, and SxA). Negative value means Jimbee is higher than C57BL/6J or 49-50-weeks is higher than 16-18-weeks or Male is higher than Female. Main effects or interaction effects were not significant (NS) if p>0.1.

| FEMALE | Genotype effect1 |

Age effect2 |

Genotype Effect within Sex3 Effect within Age (Young Old)4 |

Age Effect within Sex5 Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J Jimbee)6 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-18-week mice |

49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| Variable | Units | C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=12) |

C57BL/6J (n=13) |

Jimbee (n=19) |

||||

| Tb.BV/TV | --- | 0.190 (0.021) | 0.202 (0.021) | 0.154 (0.020) | 0.172 (0.026) | NS | S | −0.015 [0.007], (NS) | +0.032 [0.008], (NS) |

| Conn.D | mm−3 | 151.8 (41.9) | 207.1 (35.7) | 86.2 (33.4) | 136.3 (40.7) | S | +80.0 [7.3] | −52.5 [10.1], (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| SMI | --- | 0.99 (0.17) | 0.90 (0.19) | 0.91 (0.23) | 0.95 (0.27) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Tb.N | mm−1 | 4.05 (0.56) | 4.26 (0.42) | 3.03 (0.59) | 3.65 (0.95) | NS | +0.91 [0.13] | −0.46 [0.18], (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Tb.Th | mm | 0.050 (0.002) | 0.048 (0.002) | 0.051 (0.004) | 0.049 (0.003) | +0.002 [0.001] | S | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Tb.Sp | mm | 0.25 (0.03) | 0.24 (0.02) | 0.34 (0.06) | 0.29 (0.07) | NS | −0.06 [0.01] | +0.04 [0.01], (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Tb.TMD | mgHA/cm3 | 975.0 (11.5) | 966.2 (9.7) | 1014.9 (19.6) | 991.1 (13.5) | S | S | +16.5 [3.8], (NS, +16.0 [3.5]) | −32.1 [3.8], (−27.7 [4.1], −15.9 [3.6]) |

| VB strength | N | 29.0 (3.7) | 30.0 (4.9) | 25.8 (3.2) | 27.5 (5.3) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | +2.8 [1.3], (NS) |

| MALE | Genotype effect |

Age effect |

Genotype Effect within Sex Effect within Age (Young, Old) |

Age Effect within Sex Effect within Genotype (C57BL/6J, Jimbee) |

|||||

| 16-18-week mice | 49-50-week mice | ||||||||

| C57BL/6J (n=10) |

Jimbee (n=11) |

C57BL/6J (n=12) |

Jimbee (n=21) |

||||||

| Tb.BV/TV | --- | 0.260 (0.021) | 0.230 (0.031) | 0.179 (0.015) | 0.171 (0.041) | NS | S | +0.017 [0.008], (NS) | +0.069 [0.008], (NS) |

| Sex within Geno.7 | −0.047 [0.008] | −0.015 [0.007] | |||||||

| Sex within Age 8 | −0.049 [0.008] | −0.013 [0.007]* | |||||||

| Conn.D | mm−3 | 239.6 (20.5) | 248.2 (39.0) | 159.6 (16.0) | 147.3 (46.1) | S | N/A9 | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex within Geno. | −79.4 [11.0] | −27.8 [9.4] | |||||||

| SMI | --- | 0.69 (0.25) | 0.93 (0.31) | 1.19 (0.20) | 1.18 (0.40) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | −0.37 [0.08] |

| Sex within Age | NS | −0.25 [0.07] | |||||||

| Tb.N | mm−1 | 5.42 (0.21) | 5.29 (0.46) | 4.43 (0.51) | 4.23 (0.81) | NS | N/A | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex within Geno. | −1.39 [0.19] | −0.74 [0.17] | |||||||

| Tb.Th | mm | 0.052 (0.003) | 0.048 (0.003) | 0.046 (0.004) | 0.046 (0.005) | N/A | S | NS, (NS) | +0.004 [0.001], (NS) |

| Sex within Age | NS | +0.004 [0.001] | |||||||

| Tb.Sp | mm | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.04) | 0.24 (0.06) | NS | N/A | NS, (NS) | NS, (NS) |

| Sex within Geno. | +0.10 [0.01] | +0.05 [0.01] | |||||||

| Tb.TMD | mgHA/cm3 | 980.8 (10.0) | 981.0 (8.7) | 996.0 (13.8) | 988.1 (15.4) | S | S | NS, N/A | −11.5 [3.9], N/A |

| Sex within Geno. | +6.7 [4.1]* | −6.2 [3.5]* | |||||||

| Sex within Age | −10.0 [4.2] | +10.5 [2.4] | |||||||

| VB strength | N | 36.5 (4.8) | 33.3 (3.7) | 24.9 (4.0) | 24.8 (6.3) | NS | S | NS, (NS) | +10.0 [1.3] |

| Sex within Age | −5.3 [1.5] | NS | |||||||

C57BL/6J LS means –Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks LS means – 49-50-weeks LS means.

C57BL/6 female LS means – Jimbee female LS means or C57BL/6 male LS means – Jimbee male LS means.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means or 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means −49-50-weeks female LS means or 16-18-weeks male LS means – 49-50-weeks male LS means.

16-18-weeks C57BL/6J LS means – 49-50-weeks C57BL/6J LS means or 16-18-weeks Jimbee LS means – 49-50-weeks Jimbee LS means.

female C57BL/6J LS means – male C57BL/6J LS means or female Jimbee LS means – male Jimbee LS means.

16-18-weeks female LS means – 16-18-weeks male LS means or 49-50-weeks female LS mean – 49-50-weeks male LS means.

Not applicable (N/A) because Genotype or Age did not interact with sex and/or Genotype did not interact with Age and so the difference in the LS means is the same for females and males.

3.4.4.2. Effects of age and sex on vertebral bone:

With age, BV/TV, Conn.D, Tb.N, Tb.Th, and VB strength decreased, while Tb.TMD and Tb.Sp increased. Some of these age-related differences depended on the sex of the mice such that VB strength was 10 N lower for male 49-50-wk old mice and 2.8 N lower for female 49-50-wk old mice compared to the respective 16-18-wk old mice. The age-related increase in Tb.TMD was less for the Jimbee mice than for the C57BL/6 mice when accounting for sex-related differences (Table 7). Male mice tended to have higher BV/TV, SMI, Tb.N, and Tb.TMD at 16-18-wks and at 49-50-wks than the female mice though the sex-related differences were less pronounced later in life (Tb.TMD was actually lower for males). A few sex-related differences depended on genotype (Table 2 and Table 7).

4. Discussion

Metabolic characterization of the Jimbee mutation demonstrated that these mice were consistent with other mouse models involving slc5a2 gene deficiency (18, 25); specifically, Jimbee mice maintained normal serum glucose homeostasis and glucose tolerance, yet they exhibited chronic polyuria, glucosuria and hypercalciuria. Interestingly, genetic loss of SGLT2 function also contributed to compromised femur growth of both male and female mice, along with a relatively lower body weight of male Jimbee mice alone. A similar overall growth retardation has been reported in the “Sweet Pee” model of SGLT2 mutation (reported between 3-14 weeks of age), although sex differences in growth were not delineated in early characterizations of the Sweet Pee mutant (18). Following adjustment for the Jimbee body size differences, Jimbee mice were found to have diminished bone tissue mineral density at both cortical and trabecular compartments (diaphysis and metaphysis, respectively) of the appendicular skeleton. In contrast, by 49-50 weeks of age, bones of Jimbee mice exhibited greater bone toughness or less brittleness (greater work-to-failure, toughness, post-yield deflection). Together, these results indicate that chronic SGLT2 suppression, via genetic manipulation of slc5a2 gene function, impacted appendicular growth and bone mineralization, but did not affect the fracture resistance of bone. Contrary to our hypothesis, the loss of SGLT2 function did not affect bone strength in bending (Table 6) whereas the toughness of cortical bone was actually higher by 49-50 weeks of age for the Jimbee mice, compared with control mice (Table 6 and Figure 3C).

The impact of the Jimbee mutation on the axial skeleton was complex, given that there was a significant interaction between genotype and sex for most of the architectural parameters of trabecular bone. There was more trabecular bone in the vertebra of female Jimbee mice (increased BV/TV, Conn.D, Tb.N, and lower Tb.Sp) yet lower Tb.TMD. Accordingly, the compressive strength of the VB in female Jimbee mice was no different than control mice, perhaps due to a counterbalance of these features. In contrast, male Jimbee mice had lower BV/TV in the L6 VB, without significant differences in any other skeletal properties between the genotypes. That is, when comparing genotypes the absolute difference in BV/TV of 1.7% between C57BL/6J vs. Jimbee did not translate to a lower VB strength in the Jimbee mice; whereas, when comparing the age groups, the lower BV/TV in old male mice compared to young male mice (absolute difference = 6.9%) was associated with a 10 N decrease in VB strength with age (Table 7).

SGLT2 is a highly conserved (26), low-affinity/high-capacity Na+-D-glucose co-transporter localized to the apical membrane of the S1 and S2 segments of the renal proximal tubule in mammalian kidneys (27). In C57BL/6 mice, SGLT2 protein localization is nearly exclusive to the kidneys, with no extra-renal expression detected in brain, eye, intraperitoneal fat, lung, heart, gastrointestinal or reproductive organs, or in skeletal muscle (27, 28). Additionally, we have examined the expression of SGLT2 in a variety of mouse bone cells, including mouse calvarial osteoblasts, MC3T3-E1 cells at various stage of differentiation, and both pre- and mature osteoclasts from mouse bone marrow, demonstrating that SGLT2 expression was not seen in bone cells of either the osteoblast or osteoclast lineages (29). Together, this data would limit concerns for any extra-renal impact of the Jimbee mutation. Interestingly, unlike in humans where the renal expression of SGLT2 is sex-independent (30), sex-related differences in SGLT2 protein expression and/or abundance have been demonstrated in rodents (27). In mice, the expression of SGLT2 protein appears to be upregulated in males (27). Specifically, immunostaining of male kidneys has demonstrated ~2-fold stronger SGLT2 band intensity by densitometric analysis in apical brush border, compared with female tissue (27). However, while other studies have confirmed a relatively greater renal SGLT2 protein expression in the murine male kidney, a 49% higher sglt2 mRNA expression was reported in female kidneys (28), suggesting that post-transcriptional regulation of SGLT2 occurs in a male-dominant pattern. These immunohistochemical findings underscore the potential for sex differences in response to chronic pharmacologic SGLT2 inhibition in mouse models. It is unclear, however, how such differences in protein abundance would be reflected in a model of SGLT2 genetic mutation which should eliminate production of the SGLT2 protein equally in males and females. It is interesting, therefore, that our data confirmed several male-dominant components of the Jimbee phenotype. Specifically: 1) weight gain was reduced across the studied age range in male Jimbee mice but not in female mice; 2) urine output was significantly higher in male Jimbee mice compared with female mice, also potentially indicating a greater impact of the mutation on glucose-dependent osmotic diuresis in males; and 3) the effect of the mutation on cross-sectional area of the femur mid-shaft and in trabecular thickness within the distal femur metaphysis was more pronounced in male Jimbee mice compared with female mice (Tables 4 and 5). Together, these sex-specific differences infer a male-dominant severity to this phenotype in mice. In contrast, female Jimbee mice demonstrated a relatively greater increase in P1NP, indicative of higher bone formation, at the time of skeletal maturity perhaps indicating a mechanism by which female mice were protected from these bone decrements.

Mechanisms behind the sex-specific differences in body weight gain observed between C57BL/6J mice and Jimbee mice remain unclear. A relatively greater caloric loss via chronic glucosuria, leading to overall negative energy balance, could have occurred in male mice given that we observed a statistically greater increase in urine output in male Jimbee mice compared with female Jimbee mice. Alternatively, a greater upregulation of food intake could have existed in female Jimbee mice; however, this study was limited by the lack of rigorous quantification of caloric intake during the nearly year-long observation period. Therefore, we cannot now compare this between the sexes. Nonetheless, such growth differences may be irrelevant in human studies. A recent meta-analysis examining data on > 8700 individuals from 97 randomized-controlled trials, treated with SGLT2I therapy either as monotherapy or as add-on therapy for ≥ 12 weeks, concluded that drug-induced weight loss was not associated with the sex of participants (31).

In previous reports (22, 29), we have demonstrated that healthy DBA/2J mice treated for only 9-10 weeks with canagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, exhibit hypercalciuria accompanied by a decrease in Tb.TMD of the L6 vertebral body (29) and of the femur metaphysis (22), a decrease in Ct.Th of the femur diaphysis (29), and a trend toward increased osteoid surface by histomorphometry (29), all suggestive of a suppressed mineralization of bone matrix in response to SGLT2I drug exposure. Only male mice were utilized in those earlier studies. In the present study, genetic loss of SGLT2 function again resulted in significant hypercalciuria, along with a decrease in femur Ct.Th, Ct.TMD (more pronounced with age), and femur Tb.TMD. Despite the reduction in cortical thickness and tissue mineral density, the femur from Jimbee mice was not weaker in bending compared to the femur from C57BL/6J mice. This suggests that the organic matrix of the Jimbee bones confers strength more so than the organic matrix of the wild-type mice.

The higher bone toughness at middle age of the Jimbee, compared to the C57BL/6J mice also reflects a more superior organic matrix, the primary determinant of post-yield behavior of bone. The excessive urination of glucose that occurs with the sglt2 mutation (18) could prevent the accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in organic matrix as the mice age. At odds with this supposition, however, is the observation that blood glucose and HbA1c (a circulating glycation marker) were not lower in the Jimbee mice compared to the control mice. Alternatively, there is evidence in the bone biomechanical literature that impact energy and work of fracture (i.e., toughness) of bone is inversely correlated with ash fraction over the lifespan of humans (32) and among species across a wide range of mineralization (33). Moreover, in postmenopausal women, hypercalciuria has been shown to be a predictor of low bone mass (34). Thus, with genetic ablation of SGLT2 function, it is possible that hypercalciuria, and resultant reduction in Ct.TMD, could protect the Jimbee mice from the age-related loss in toughness.

The actual cause of the higher bone toughness in the Jimbee mice with age requires additional analyses that assess potential differences in the toughening mechanisms of cortical bone. Others have reported, for example, that in other rodent models of disrupted glucose metabolism, the mechanical integrity of bone is impacted (35) by: 1) intra-skeletal AGE accumulation (leading to loss of bone toughness) (36, 37); 2) alterations in the nanoscale morphology of type 1 collagen fibrils (38); and 3) higher Raman spectroscopy mineral-to-matrix and matrix maturity ratios (also associated with lower bone toughness) (21). Alternatively, relative bone dehydration, as could occur with chronic osmotic diuresis in Jimbee mice, also negatively impacts bone toughness, both in humans and in animals (39, 40). Consequently, potential explanations for the higher bone toughness in Jimbee mice with age could come from future studies that evaluate whether the bone matrix in Jimbee mice has more enzymatic but less non-enzymatic collagen crosslink levels, lower fluorescent AGEs, lower mineral-to-matrix ratio, greater degree of helical order of collagen I, more matrix-bound water, and/or greater capacity to sustain collagen fibril strain for a given load than the bone matrix of wild-type mice.

As another limitation, the present study did not determine whether there were differences in the expression of matrix genes or matrix proteins between the genotypes. Possibly, the hypercalciuria caused the osteocytes to express matrix-related genes despite the apparent lack of an effect on circulating FGF23 by the mutation (Table 3). Lastly, the serum biochemistry was used to establish that the mutation indeed increased the urinary excretion of calcium without altering glucose metabolism, but not to explain genotype-, sex-, and age-related differences in bone characteristics. As another limitation then, the present study did not ascertain the reason why certain age-related changes in bone characteristics were different between the sexes or between genotypes. Additional age groups are likely necessary to establish the age at which bone accrual, bone structure, and bone strength peaks in female and male wild-type and Jimbee mice.

The initial impetus for this rodent study was to better understand the impact of “gliflozin” medications on skeletal phenotype and homeostasis, in light of early reports linking specific SGLT2I drugs to an increased risk for fracture or amputation (41, 42), particularly among certain at-risk human T2D populations (4, 16). Subsequent clinical studies, however, have reported no generalizable increase in treatment-emergent fracture, across multiple SGLT2I medications [i.e., canagliflozin (16), dapagliflozin (43), empagliflozin (44, 45)] following prolonged therapy. Interestingly, these more recent clinical observations are consistent with our findings in the Jimbee mouse, wherein genetic deletion of SGLT2 function was actually associated with an increase in bone toughness and resistance to fracture, with advancing age. It remains to be seen whether decades-long pharmacologic exposure to SGLT2I medications in humans will have any beneficial vs. detrimental impact on bone health.

5. Conclusions

Using the “Jimbee” mouse model of slc5a2 gene mutation, we have investigated the impact of SGLT2 loss-of-function on metabolic and skeletal phenotype, as male and female mice progress from skeletal maturity to middle age. Study findings demonstrated that the Jimbee mutation negatively impacted appendicular growth of the femur and resulted in lower tissue mineral density of both cortical and trabecular bone sites, perhaps in conjunction with chronic hypercalciuria. However, cortical bone strength was not affected by the mutation, and the expected age-related decline in bone toughness was less for Jimbee mice, such that by 49-50 weeks of age, Jimbee mice had significantly tougher femurs, compared with C57BL/6J mice. A direct comparison of this data with human drug exposure is not reasonable, given that Jimbee mice exhibit normal glucose tolerance, in contrast to the diabetes population in which SGLT2 inhibitors would be clinically indicated. Never-the-less, our findings might mitigate some concern that these drugs would negatively affect the fracture resistance of bone over time.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Genetic ablation of SGLT2 function in mice results in decreased tissue mineral density of cortical (Ct.TMD) and trabecular bone (Tb.TMD).

Many phenotypic and skeletal outcomes, comparing Jimbee vs. C57BL/6J, were sex-specific and more prominent in the male Jimbee mice.

Male Jimbee mice display greater deficits in body mass, femur cross-sectional area, femur trabecular thickness, and vertebral body trabecular bone.

Although Ct.TMD is lower, the strength of cortical bone is similar between Jimbee and C57BL/6J mice.

Jimbee mice appear protected from age-related loss in toughness, having greater bone toughness in bending by 50 weeks of age.

Acknowledgments and Funding:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants, R21AR070620 (to K.M.T and J. S.N.) and R56DK084045 (to J.L.F.), as well as the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development 1I01BX001018 (to J.S.N.). Additional funding was provided by the University of Kentucky Barnstable Brown Diabetes Center Endowment. The mouse strain used for this research project, C57BL/6J-Slc5a2m1Btlr/Mmmh, RRID: MMRRC_036517-MU, was obtained from the Mutant Mouse Resource and Research Center (MMRRC) at University of Missouri, an NIH-funded strain repository, and was donated to the MMRRC by Bruce Beutler, M.D., University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The authors also appreciate the preliminary statistical analysis of portions of this data provided by Katherine L. Thompson, PhD and Gregory S. Hawk, BS from the University Of Kentucky Department Of Statistics.

Funding Source: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, R21AR070620 (to K.M.T and J.S.N.) and R56DK084045 (to J.L.F.); as well as the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, 1I01BX001018 (to J.S.N.). Additional funding was provided by the University of Kentucky Barnstable Brown Diabetes Center Research Endowment.

Footnotes

Duality of Interests:

The authors have no financial or personal conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Monami M, Nardini C, Mannucci E. Efficacy and safety of sodium glucose co-transport-2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2014;16(5):457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghezzi C, Loo DDF, Wright EM. Physiology of renal glucose handling via SGLT1, SGLT2 and GLUT2. Diabetologia. 2018;61(10):2087–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(22):2117–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, et al. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine. 2017;377(7):644–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang XL, Zhu QQ, Chen YH, Li XL, Chen F, Huang JA, et al. Cardiovascular Safety, Long-Term Noncardiovascular Safety, and Efficacy of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis With Trial Sequential Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins BA, Cherney DZ, Partridge H, Soleymanlou N, Tschirhart H, Zinman B, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition and glycemic control in type 1 diabetes: results of an 8-week open-label proof-of-concept trial. Diabetes care. 2014;37(5):1480–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argento NB, Nakamura K. Glycemic Effects of Sglt-2 Inhibitor Canagliflozin in Type 1 Diabetes Patients Using the Dexcom G4 Platinum Cgm. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2016;22(3):315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenstock J, Marquard J, Laffel LM, Neubacher D, Kaspers S, Cherney DZ, et al. Empagliflozin as Adjunctive to Insulin Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes: The EASE Trials. Diabetes care. 2018;41(12):2560–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]