Abstract

Background:

Having support from an informal carer is important for heart failure patients. Carers have the potential to improve patient self-care. At the same time, it should be acknowledged that caregiving could affect the carer negatively and cause emotional reactions of burden and stress. Dyadic (patient and informal carer) heart failure self-care interventions seek to improve patient self-care such as adherence to medical treatment, exercise training, symptom monitoring and symptom management when needed. Currently, no systematic assessment of dyadic interventions has been conducted with a focus on describing components, examining physical and delivery contexts, or determining the effect on patient and/or carer outcomes.

Objective:

To examine the components, context, and outcomes of dyadic self-care interventions.

Design:

A systematic review registered in PROSPERO, following PRISMA guidelines with a narrative analysis and realist synthesis. Data Sources: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched using MeSH, EMTREE terms, keywords, and keyword phrases for the following concepts: dyadic, carers, heart failure and intervention. Eligible studies were original research, written in English, on dyadic self-care interventions in adult samples.

Review methods:

We used a two-tiered analytic approach including both completed studies with power to determine outcomes and ongoing studies including abstracts, small pilot studies and protocols to forecast future directions.

Results:

Eighteen papers – 12 unique, completed intervention studies (two quasi- and ten experimental trials) from 2000 to 2016 were reviewed.

Intervention components fell into three groups – education, support, and guidance. Interventions were implemented in 5 countries, across multiple settings of care, and involved 3 delivery modes – face to face, telephone or technology based. Dyadic intervention effects on cognitive, behavioral, affective and health services utilization outcomes were found within studies. However, findings across studies were inconclusive as some studies reported positive and some non-sustaining outcomes on the same variables. All the included papers had methodological limitations including insufficient sample size, mixed intervention effects and counter-intuitive outcomes.

Conclusions:

We found that the evidence from dyadic interventions to promote heart failure self-care, while growing, is still very limited. Future research needs to involve advanced sample size justification, innovative solutions to increase and sustain behavior change, and use of mixed methods for capturing a more holistic picture of effects in clinical practice.

Keywords: Dyad, Heart failure, Self-care, Systematic review, Interventions, Caregiving

1. Introduction

Heart failure is a common condition worldwide, with a prevalence of 1–2% in the population; rising to ≥10% among persons above 70 years of age (Yancy et al., 2013; Ponikowski et al., 2016). Heart failure self-care interventions which improve heart failure patients’ necessary knowledge and management skills for this chronic and progressive condition are advocated for in clinical guidelines and widely implemented in heart failure care (Yancy et al., 2013; Ponikowski et al., 2016). A recent meta-analysis of 20 studies (n = 5624 patients) found that self-care interventions which targeted patients alone without involving informal carers were effective in reducing hospitalization or all-cause death, delaying time to hospitalization, and improving quality of life during the study (Jonkman et al., 2016). However, a critical question facing clinicians and researchers is why heart failure self-care interventions have often resulted in non-sustained effects on patient outcomes when examined over time (Liljeroos et al., 2015). A series of recent systematic reviews (Clark et al., 2014; Currie et al., 2015; Harkness et al., 2015; Strachan et al., 2014; Spaling et al., 2015) suggest that one explanation for this could be that these past self-care interventions which have targeted only the patient have missed a critical component – the informal carer. In actual practice, patients rarely engage in heart failure self-care in isolation (Buck et al., 2015a).

Many heart failure patients live within a family system as part of a patient/informal carer dyad. A dyad is typically defined as two individuals maintaining a sociologically significant relationship (Merriam-Webster, 2017). Members of heart failure patient/carer dyads have been found to influence each other’s behavior, physical and mental well-being (Buck et al., 2015b; Kitko et al., 2014; Vellone et al., 2014). For example, higher self-care maintenance in patients has been associated with better mental well-being in carers (Vellone et al., 2014). In a recent review of 45 qualitative studies, two factors were identified: 1) the importance of carers and social support in patients’ self-care and 2) the carers’ relative under-representation in current self-care programs (Strachan et al., 2014). In another systematic literature review of heart failure self-care determinants, the researchers found significant linkage between increased involvement by others in patient self-care and greater intervention effectiveness (Clark et al., 2014). Yet, self-care interventions which include patient and informal carer dyads remain a relatively recent, but growing area of exploration.

Self-care interventions target daily heart failure patient self-care behavior, such as adherence to medical treatment, exercise training, routine self-monitoring and symptom management when needed (Riegel et al., 2016). Dyadic self-care interventions are delivered to both a patient and his/her informal carer with expectations that both dyad members will be actively engaged in the patient’s heart failure self-care. Dyadic self-care interventions generally mirror current patient interventions by including educational materials as well as some form of support and guidance. Currently, no systematic assessment of heart failure self-care dyadic interventions has been conducted with a focus on describing components, examining contexts, or determining the effect on patient and/or carer outcomes. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic literature review was to examine in Aim 1) the components; in Aim 2) the contexts; and in Aim 3) the outcomes of dyadic self-care interventions. This study’s findings will enable researchers to chart future directions in the science of dyadic interventions.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

We conducted a systematic review with a narrative analysis and realist synthesis to answer our questions. Meta-analysis was deemed not appropriate given the small number of studies and heterogeneity of the interventions. The systematic review team consisted of six international nurse researchers with significant experience in conducting studies to support heart failure self-care, one clinical psychologist with dyadic self-care intervention expertise, and two medical librarians. The team developed the study protocol based on PRISMA statement criteria (Liberati et al., 2009) and methods developed in previous systematic reviews (Buck et al., 2015a, 2012, 2013). The protocol was then registered with PROSPERO (CRD42016050214).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The heart failure dyadic intervention body of literature is limited. Therefore, we were as inclusive as possible to capture the extant literature across disciplines. A decision was made a priori to hold 1) meta-analyses or reviews for reference list hand-searches rather than analysis; and 2) abstracts (without full papers), feasibility/small pilot studies, or protocol papers for a separate analysis to forecast future directions in this line of inquiry. This design decision resulted in a two-tiered analytic approach. Specifically, we analyzed 1) completed studies with sufficient information and power to determine patient/carer outcomes, and 2) ongoing studies including abstracts, small pilot studies, and protocols to explore future directions in dyadic intervention research. Inclusion criteria for all papers were: adult samples (18 years of age or greater); dyad consisting of a patient with heart failure and at least one informal carer; both dyad members must be the target of the intervention, present at the intervention and outcomes (primary or secondary) from both OR either one of the participants measured; English language papers; intervention description provided (with hand-searches if intervention described in a second paper); and with an experimental or quasi-experimental design. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews (except as noted above); duplicative papers; case reports, opinion pieces, editorials and letters to the editor were excluded.

2.3. Information sources and search

The two medical librarians developed and performed searches in PubMed (1946 to present), EMBASE (Elsevier, 1947 to present), Web of Science (Core Collection, 1900 to present), PsycINFO (EBSCO, 1887 to present), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, through August 2016). MeSH terms, EMTREE terms, keywords, and keyword phrases were used to search for the following concepts: dyadic; carers; heart failure; and intervention. Search terms were shared with the team to elicit feedback. Searches were limited to English language. Appendix A shows the detailed search strategies.

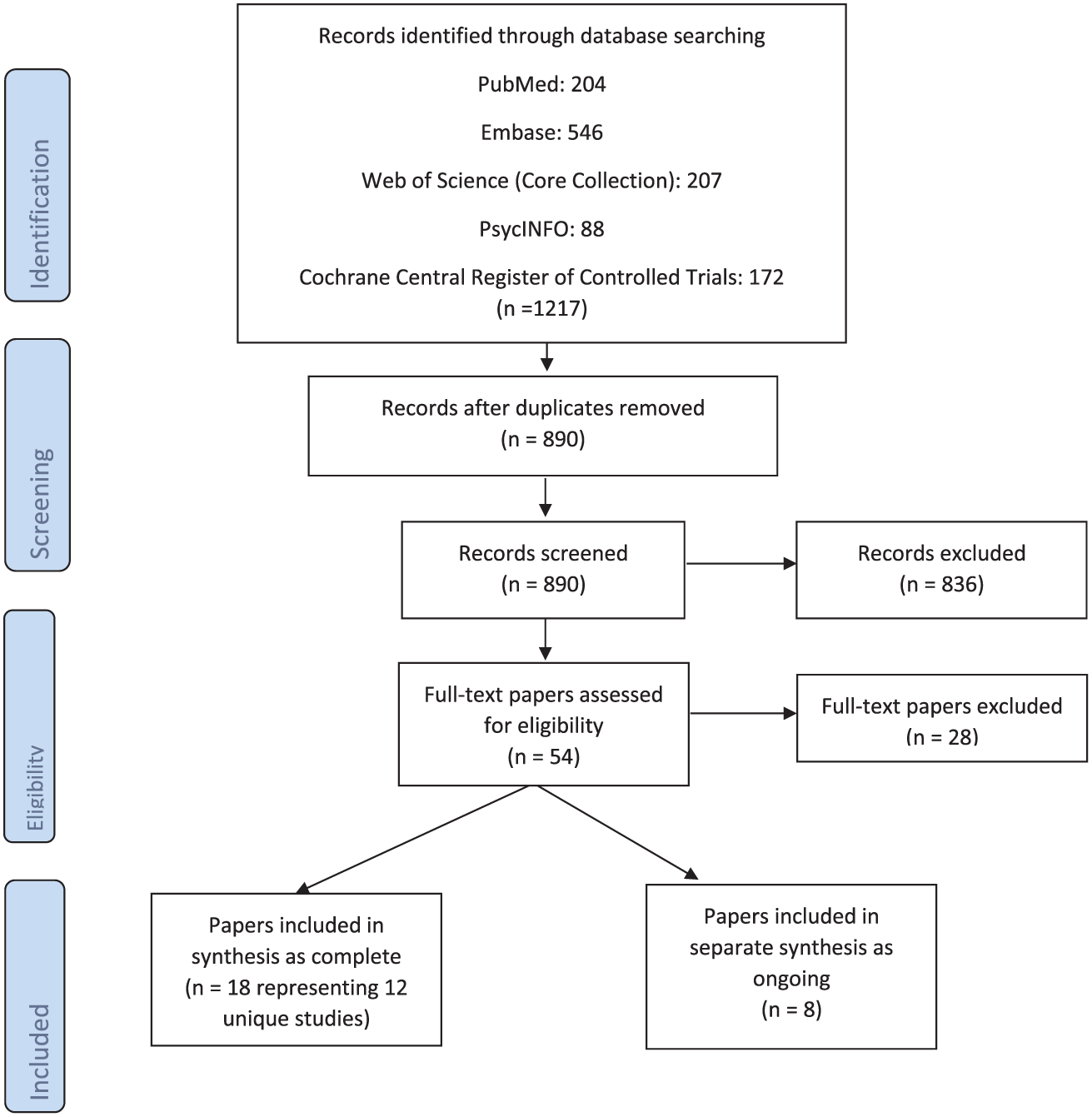

The combined searches yielded 1217 papers as of September 29, 2016. All papers were exported into EndNote and 327 duplicates were removed mechanically. The remaining papers (890) were imported into an MS EXCEL worksheet for purposes of documenting the inclusion/exclusion analysis performed by the team.

2.4. Study selection

A two-step screening approach was used to select the final papers to include in the review. In the first screen (title/abstract screen), the 890 papers were divided amongst five team members with a planned overlap of 5% of the papers given the large sample size. Approximately 200 papers were reviewed per team member. The focus was on retaining as many papers as possible, therefore team members were instructed to retain any ambiguous papers for the next level of review. For example, if a title appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but there was no abstract the paper was retained until the criteria could be applied to the full paper. Team members were also instructed to retain papers that met the criteria for the hand search and separate analysis (ongoing studies). One team member was held out of this screening step and analyzed the overlapping papers to assess inter-rater reliability. Only four papers from the 5% overlap (n = 45 papers) resulted in disagreement (91% inter-rater agreement). These four papers were then reviewed and discussed by two other team members and a decision to keep or discard resulted. The title/abstract screen resulted in 54 papers for full-text review. In the second screen, the full-text of the 54 papers were reviewed once again using our criteria. If there were multiple papers from one author or research team, they were reviewed by the same reviewer to assure that duplicate papers would be identified and discarded. The papers were divided amongst the team and went through a 100% overlap review. Two team members had to agree on inclusion and exclusion determination of the article resulting in 100% inter-rater agreement.

2.5. Data collection process and data items

Data extraction elements were selected a priori to address our aims. These included: intervention components, contextual details and main study outcomes. We also collected: year of publication, journal, study design, sample size, participant age and relationships in the dyad (spouse/partner, adult child, relative, friend, etc.). The data extraction form was adapted from previous studies and team discussion. Team members also received an EndNote library of all the papers with the full-text PDFs attached. Each paper was abstracted by one team member and then confirmed by a second team member.

2.6. Risk of bias analysis

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) criteria (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2017) were used to assess for risk of bias in all the papers; CASP provides standardized, study design specific, criteria that allowed us to analyze multiple study designs using a single program. Each team member conducted the CASP appraisal while extracting study data. For example, randomized control trials (RCTs) were analyzed for blinding, similarity between groups on baseline data, equal treatment besides experimental condition and allocation, while quasi-experimental papers were analyzed for representativeness, exposure measurement, identification of confounders and assessment of follow-up time. The quality assurance steps are summarized in Box 1.

Box 1. Quality assurance steps.

Use of a standardized protocol

Frequent, regular team communication

Eligibility confirmation at each step

Inter-rater assessment at each step

Standardized process for resolving reviewer disagreement

Standardized data extraction process

CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) criteria used to asses for risk of bias in all studies

Final approval of full team on all papers for inclusion

2.7. Synthesis of results

Realist synthesis techniques (Pawson et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2013) as in previous heart failure systematic reviews (Buck et al., 2015a; Clark et al., 2016) were used to interpret the data elements across papers, analyze the nature and relationships between the data elements and draw conclusions about the higher order abstractions. In the first aim specific techniques included: data elements (actual intervention components) were identified in individual papers, aggregated across papers and then categorized. Conclusions related to the categories were then drawn. In the second aim, implementation contexts were the data elements and patterns across papers were identified and conclusions drawn. In the third aim, all reported outcomes were identified individually, then categorized across papers and finally analyzed to determine patterns in responses. To forecast the direction of future dyadic intervention studies, we analyzed ongoing studies that our search uncovered, and to the degree possible, evaluated them using the same criteria used in our analyses of the completed studies.

3. Results

See Fig. 1 for numbers of papers screened, assessed for inclusion, and included in the review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram.

Eighteen papers involving 12 unique, complete intervention studies, from 2000 to 2016, met the criteria of complete studies. Of the 12 complete studies there were two quasi-experimental studies (Bull et al., 2000; Piette et al., 2008) and 10 RCTs. See Table 1 for the characteristics of the main outcome papers from the 12 complete studies. Six papers (Liljeroos et al., 2015, 2016; Agren et al., 2013, 2015; Stamp et al., 2016; Dunbar et al., 2016) reported on secondary outcomes or primary outcome variables at a later time from the complete studies. These secondary outcome papers were included in the systematic analysis to examine additional intervention effect on outcomes. Eight papers met the criteria of ongoing studies. These included six abstracts (Chung et al., 2014a, 2014b; Bakitas et al., 2016; McIlvennan et al., 2015; Deek et al., 2015; Demers et al., 2014), one feasibility study (Dionne-Odom et al., 2014), and one protocol paper (Taylor et al., 2015). Methodological analysis using CASP criteria found some limitations related to blinding, allocation, and effect sizes in all studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 12 Complete Studies.

| Authors | Publication Year | Country | Study Design | Type of Dyads | Gender (% male) | Sample Size | Mean Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bull et al., (2000) | 2000 | US | Pre/post nonequivalent control group | Spouse 50%, Adult child 38%, Family 7%, Friend 5% | Patient ND Carers 27% | 180 dyads | Patient 73.7 ± 8.8, Carer 58.5 ± 14.9 |

| Dunbar et al. (2005) | 2005 | US | RCT | Spouse 67%, Adult child 22%, Other 11% | Patients 54%, Carers 23% | 61 dyads | Patient 61.0 ± 12, Carer 54.0 ± 17 |

| Piette et al. (2008) | 2008 | US | Cohort study | Adult child 75%, Family 15%; Friend 10% | Patients 89%, Carer 42% | 52 dyads | Patient 65.9 ± 11.0, Carer 42.3 ± 10.0 |

| Schwarz et al. (2008) | 2008 | US | RCT | Intervention group Spouse 64%, Adult child 26%, Other 10%, Control group Spouse 43%, Adult child 31%, Other 10% | Patient 48%, Carer ND | 102 dyads | Patient 78.1 ± 7.1, Carer 63.4 ± 16.1 |

| Agren et al. (2012) | 2012 | Sweden | RCT | Partner 100% | Patient intervention group 69%, Control group 81%, Carer intervention group 31%, Control group 19% | 155 dyads | Intervention group 67.0 ± 13.0, Control group 70.0 ± 10.0 |

| Dunbar et al. (2013) | 2013 | US | RCT | Spouse 53%, Adult child 22%, Other 25% | Patient 63%, Carer 17% | 117 dyads | Patient 55.9 ± 10.5 Carer 52.3 ± 33.3 |

| 2015 | Sweden | RCT | Partner 100% | Patient intervention group 84%, Control group 94%, Carer intervention group 16%, Control group 6% | 42 dyads | Patient intervention group 70.0 ± 9.0, Control group 69.0 ± 8.0, Carer intervention group 67.0 ± 7.0, Control group 66.0 ± 8.0 | |

| Srisuk et al. (2015) | 2015 | Thailand | RCT | Intervention group Spouse 24%, Adult child 42%, Family 34%, Control group Spouse 30%, Adult child 36%, Family 34% | Patient intervention group 44%, Control group 50%, Carer intervention group 32%, Control group 22% | 100 dyads | Patient intervention group 65.0 ± 14.0, Control group 59.0 ± 18.0, Carer intervention group 39.0 ± 10.0, Control group 43.0 ± 11.0 |

| Piette et al. (2015) | 2015 | US | RCT | Adult child 61%, Family 27%, Friend 12% | Patient intervention group 99%, Control group 99%, Carer intervention group 32%, Control group 32% | 369 dyads | Patient intervention group 67.8 ± 10.2, Control group 68.0 ± 10.2, Carer intervention group 46.6 ± 12.1, Control group 47.6 ± 14.2 |

| Piamjariyakul et al. (2015) | 2015 | US | RCT | Spouse 65%, Family 35% | Patient 60%, Carer 15% | 20 dyads | Patient 62.3 ± 13.5 Carers 61.4 ± 10.0 |

| Kenealy et al. (2015) | 2015 | New Zealand | RCT - 3 sites with different protocols | ND | Patient 59%, Carer ND | 171 dyads | Patient 65.3, Carer ND |

| Hasanpour-Dehkordi et al. (2016) | 2016 | Iran | RCT | ND | Patients intervention group 60%, Control group 62%, Carers ND | 90 dyads | Patient intervention group 60.8, Control group 59.1 Carers ND |

RCT –erandomized control trial; ND – no data.

A total of 1459 dyads (sample sizes range 20 (Piamjariyakul et al., 2015)–372 (Piette et al., 2015)) from the complete intervention studies were involved with an average patient age across studies of 59–78 years and an average carer age of 29–67 years. The studies which clearly identified the types of dyads reported spousal (n = 417), adult child (n = 344), or friend/relative (n = 209) dyadic partners. Two of the 12 studies included only spouse/partner dyads (Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015), two studies did not identify the dyad relationships (Kenealy et al., 2015; Hasanpour-Dehkordi et al., 2016), the other eight studies included mixed dyads, primarily spouse or adult child dyads.

3.1. Dyadic intervention components

3.1.1. Component groups

The components of the 12 interventions aligned into three groups – those that could be categorized as including a) education; b) support, and c) guidance. Education components were defined as either information related to heart failure, its management or educational strategies. Examples of education informational components included information about heart failure (Dunbar et al., 2005; , 2013; Schwarz et al., 2008; Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015; Srisuk et al., 2015; Piette et al., 2015), skill-building (Bull et al., 2000; Dunbar et al., 2005; , 2013; Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015; Piamjariyakul et al., 2015), and relationship information (Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015). Educational strategies included technological (use of computer/telephone (Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015; Piette et al., 2015; Piamjariyakul et al., 2015)) or methodological (use of teach-back (Srisuk et al., 2015), printed materials (Bull et al., 2000; Piette et al., 2008; Agren et al., 2012; Srisuk et al., 2015; Piamjariyakul et al., 2015) or role play/group discussion (Dunbar et al., 2005, 2013)) strategies. Support components were defined as ancillary support resources or actual support provided during the intervention. Examples of supportive components were equally diverse and included referral to additional resources, (Piette et al., 2008; Piamjariyakul et al., 2015), information on the importance of support Ågren et al. (2015) or actual supportive calls (Dunbar et al., 2005, 2013). Guidance components were defined as specific verbal or written directions given during the intervention to improve care. All intervention studies included guidance components. See Table 2 for a list of intervention components for each study.

Table 2.

Summary of Dyadic Intervention Components, Contexts, and Outcomes.

| Authors | Intervention Components | Intervention Physical Contexts | Intervention Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bull et al. (2000) | 1 time: Staff training included: Patient and Carer assessment, videotape; structured communication guide for use with clinicians; Medication form to fill out; Brochure on community services | Hospitals | Significantly higher Patient preparedness, continuity of care, health perception, and vitality at 2 weeks post-hospital discharge; Significantly better continuity of care at 2 months post-discharge; No statistically significant differences in scores on satisfaction or difficulties in managing care at 2 weeks or 2 months post-discharge; Significantly higher Carer scores on continuity of information about condition, services available, general health perceptions, vitality, mental health; less negative reaction to caregiving 2 weeks post-discharge; Significantly higher Carer scores on care continuity scales at 2 months post-discharge; No significant differences on hospital readmission and emergency room use at 2 weeks post-discharge; Average cost savings per person approximately $4300 |

| Dunbar et al. (2005) | 1 face-to-face education and counseling session; Video; Follow up phone call with patient data; Newsletter; Same components as 1st group; Plus 2 additional sessions on family support and patient choice; Case scenarios; Group discussion; Role-play | General Clinical Research Center | Both groups decreased dietary NA+ at 3 months; 2nd group showed greater decrease in NA+ and greater percentage of patients with decreased NA +; Significant increases in Patient and family heart failure knowledge from pre- to post- education sessions in both groups but did not differ in degree of knowledge change; Both groups declined in knowledge by 3 months; Significant Group X Time interaction when accounting for time-varying measures of body mass index; No significant changes in autonomy support in either group |

| Piette et al. (2008) | Weekly interactive voice response calls to Patient for 6–15 weeks; Automated report to Carer; Links to additional online resources; Web page with patient information | Academic medical center and VA hospital | 92% completion rate and reported problems that might otherwise have gone unidentified. 75% made changes in self-care because of the intervention |

| Schwarz et al. (2008) | 1 home visit to train on equipment which automatically uploaded daily weight; Answer pre-programed questions on symptoms; APN monitored and called in response to | Academic medical center | No significant differences for any outcomes |

| Agren et al. (2012) | 3 face-to-face sessions; Computer-based educational program; Written materials | Outpatient clinic in one university and, one county hospital or patient’s home | Significantly increased patient-perceived control at 3 months; No effect on dyads quality of life and depression; No effect on Carer burden |

| Dunbar et al. (2013) | 1 face-to-face education session; 1 group reinforcement session; Written materials; DVD; Written individual feedback; 1 telephone booster session; Newsletters; Same components as 1st group; Plus 2 small group sessions with breakout sessions with dyad together and separate | Outpatient clinic | No significant changes in medication adherence, autonomy support in either group; Increased heart failure knowledge immediately after intervention but not sustained; Significant changes in dietary NA+ in both groups |

| 1 face-to-face session; 2 telephone sessions; Psychoeducational support | Outpatient clinic | No significant differences on SF-36 after 3 and 12 months; Significantly improved SF-36 dimensions over time; No difference in depression | |

| Srisuk et al. (2015) | 1 face-to-face session; 9 telephone sessions; Heart failure manual; DVD | Outpatient clinic | Significantly increased dyad knowledge at 3 and 6 months; Significantly increased Patient self-care maintenance, confidence, and health-related quality of life at 3 and 6 months, and self-care management at 6 months; Significantly increased Carer perceived control at 3 months. |

| Piette et al. (2015) | Weekly interactive voice response calls to Patient for 12 months; Carer mailed information on heart failure self-care; Weekly interactive voice response calls to Patient for 12 months; Automated report to Carer; Links to additional online resources; Communication printed guidelines; Logbook; Laminate reminder and tips cards | Veteran’s Administration outpatient clinics | Significantly less Carer strain at 6 and 12 months; Interaction effect between arm and baseline on Carer strain/depression at both endpoints; Significantly less time spent in high time commitment Carers; greater participation in clinic visits and medication adherence |

| Piamjariyakul et al. (2015) | 4 weekly telephone sessions; Printed materials (caregiving guide, list of local support organizations); Pill organizer; Referral to Social Worker if needed | Outpatient clinic | Significantly fewer heart failure rehospitalizations at 6 months; Significantly higher Carer confidence and social support scores and significantly lower Carer depression; No significant difference in preparedness or burden |

| Kenealy et al. (2015) | 1 home visit to train on equipment which provided instruction, asked pre-programmed questions, gave short message; Patient entered self-care data manually; Monitored by clinicians | Hospital, primary care site | No significant changes in quality of life, self-efficacy and disease-specific measures; Significant changes in anxiety and depression; No significant changes in hospital admissions, days in hospital, emergency department visits, outpatient visits and costs |

| Hasanpour-Dehkordi et al. (2016) | 3 face-to-face sessions; Education | Hospital | Significant difference in physical activity limitation following physical problems, energy and fatigue, social performance, physical pain and general health 6 months; Significant difference in quality of life at 6 months; Significant differences in hospital readmissions and referring to physicians; Significant difference in mean health care cost |

NA+ – sodium; VA – Veterans Administration; SF-36 – Short Form (36) Health Survey.

3.1.2. Component numbers

The number of individual components per intervention varied greatly but ranged from two to six components. The 12 interventions included variable numbers of sessions in which the components were delivered; ranging from one home visit to deliver equipment (Kenealy et al., 2015) to weekly telephone calls for 12 months (Piette et al., 2015). The time spent during a session ranged from a 15-min phone call (Srisuk et al., 2015) to a 90-min phone call (Piamjariyakul et al., 2015) with most face-to-face sessions lasting approximately 60 min (or multiples of this).

We attempted to derive a dose (number of sessions) and strength of the dose (comprised of amount of time for each of the session, length of the intervention and length of any follow-up) for each study. However, there was great heterogeneity and incompleteness in reporting both the number of sessions and time spent per session precluding an accurate description of dose and strength of dose for some interventions. As an example of this heterogeneity, Ågren et al. (Agren et al., 2012) reported an intervention comprised of three components (face-to-face counseling, computer-based program and written materials). The intervention involved three sessions of 60 min each suggesting 180 min of direct contact with an interventionist during the intervention. A second intervention23 included a detailed description of a multi-component intervention but provided no clear information on number of components nor length of time per contact. Therefore, we were unable to summarize an accurate dose of the intervention to make a comparison.

3.2. Dyadic intervention contexts

3.2.1. Physical context

Countries where interventions were tested included the United States (Bull et al., 2000; Dunbar et al., 2005, 2013; Piette et al., 2008, 2015; Piamjariyakul et al., 2015), Sweden (Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015), New Zealand (Kenealy et al., 2015), Iran (Hasanpour-Dehkordi et al., 2016), and Thailand (Srisuk et al., 2015). Settings where the intervention was initiated or where the majority of the interventions were delivered included hospitals (Bull et al., 2000; Piette et al., 2008; Schwarz et al., 2008; Agren et al., 2012; Kenealy et al., 2015; Hasanpour-Dehkordi et al., 2016), clinics (Agren et al., 2012; Dunbar et al., 2013; Ågren et al., 2015; Srisuk et al., 2015; Piamjariyakul et al., 2015), home (Agren et al., 2012), a U.S. Veterans Administration (clinic or hospital),(Piette et al., 2008, 2015) and in a clinical research center (Dunbar et al., 2005). Two studies (Piette et al., 2008; Agren et al., 2012) included multiple sites to support the transition from hospital to home or increase recruitment.

3.2.2. Delivery context

The 12 interventions aligned into three delivery contexts – those which could be categorized as face-to-face (Bull et al., 2000; Dunbar et al., 2005; , 2013; Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015; Srisuk et al., 2015; Hasanpour-Dehkordi et al., 2016); telephone (Piamjariyakul et al., 2015); or telehealth interventions (see Table 2) (Piette et al., 2008, 2015; Schwarz et al., 2008; Kenealy et al., 2015). Most face-to-face interventions also used some form of technology including DVD/video (Bull et al., 2000; Dunbar et al., 2005; Srisuk et al., 2015), website (Agren et al., 2012), or phone calls (Dunbar et al., 2005; , 2013; Ågren et al., 2015; Srisuk et al., 2015) blurring the line between “high touch” and “high tech” modalities. It appears that all the studies were investigator-initiated and led.

3.3. Dyadic intervention outcomes

3.3.1. Outcome groups

This analysis included both primary and secondary outcome papers (n = 18). The synthesis resulted into four patient outcome categories comprised of cognitive outcomes (e.g., perceived control, preparedness to care, knowledge); behavioral outcomes (e.g., self-care, carer attending clinic visits); affective outcomes (e.g., depression, social support, strain); and health services utilization outcomes (e.g., hospitalization, quality adjusted life years) (Table 2).

3.3.2. Effect on outcomes

See Table 3 for information on positive, null, and mixed outcomes. Papers reporting positive outcomes include findings in all four categories (cognitive, behavioral, affective, and health services utilization). In the main outcome papers of the complete studies only one paper reported null findings on all outcomes (Schwarz et al., 2008). In the five papers which reported secondary outcomes or primary outcome variables at a later time null findings were noted (Liljeroos et al., 2015, 2016, 2014a; Agren et al., 2013, 2015). These included outcomes such as quality adjusted life years (Agren et al., 2013), carer tasks, burden or patient morbidity (Liljeroos et al., 2016; Agren et al., 2015), or non-sustaining differences at a subsequent measurement time (Liljeroos et al., 2015, 2014a). Deeper analysis identified perceived control, quality of life, preparedness to care, self-care, depression, social support and rehospitalization as the outcome variables with mixed (positive and null) findings (Table 3). One example highlights this: perceived control, as measured by the Control Attitude Scale, was reported in three papers (Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015; Srisuk et al., 2015). In the first RCT (Agren et al., 2012) patients in the intervention arm showed significant improvements in perceived control at three months which was not sustained at 12 months while perceived control in carers did not change. In the second RCT (Ågren et al., 2015) patients in the intervention arm showed significant improvements in perceived control at both three and 12 months with no changes in perceived control in carers. In the third RCT (Srisuk et al., 2015) perceived control was only measured in carers. Carers in the intervention arm showed significant improvement in perceived control at three months, but as in the first study, this improvement was not sustained at six months. The intervention components were similar (education, support, and guidance) yet heterogeneous enough in terms of interventionist, time allocation, and delivery modes making it difficult to attribute either positive or null outcomes to the intervention.

Table 3.

Categorization and Summary of Dyadic Intervention Outcome.a

| Positive Outcomes | Null Outcomes | Mixed Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Outcomes | Patient perceived control at 3 months (Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015) and 12 months (Ågren et al., 2015) Carer perceived control at 3 months (Srisuk et al., 2015) Patient quality of life at 3 (Srisuk et al., 2015) and 6 months (Srisuk et al., 2015; Hasanpour-Dehkordi et al., 2016) Patient preparedness to care at 2 weeks (Bull et al., 2000) Carer reaction to caregiving (Bull et al., 2000) Patient knowledge (Dunbar et al., 2013) Patient/Carer knowledge (Dunbar et al., 2005; Srisuk et al., 2015) | Patient perceived control at 12 months (Agren et al., 2012) Carer perceived control at 6 months (Srisuk et al., 2015) Patient/Carer perceived control at 24 months (Liljeroos et al., 2015) Patient quality of life at 3 months (Schwarz et al., 2008) Patient/Carer quality of life at 3 months (Agren et al., 2012) Patient quality of life at 6 months (Kenealy et al., 2015) Carer preparedness to care at 6 months (Piamjariyakul et al., 2015) Patient/Carer satisfaction with care (Bull et al., 2000) Patient (Liljeroos et al., 2015)/Carer (Liljeroos et al., 2016) morbidity | Perceived control for both Patient and Carer; Quality of life for Patient; Preparedness to care for both Patient and Carer |

| Behavioral Outcomes | Patient self-care at 3 and 6 months (Srisuk et al., 2015) Carers attending visits(Piette et al., 2015) | Patient self-care at 6 months (during intervention) (Kenealy et al., 2015) Patient medication adherence (Dunbar et al., 2013) Carer tasks (Agren et al., 2015) | Self-care for Patient |

| Affective Outcomes | Patient/Carer depression at 6 months (Piette et al., 2015; Piamjariyakul et al., 2015; Kenealy et al., 2015) Patient social support at 6 months (Piamjariyakul et al., 2015) Carer confidence (Piamjariyakul et al., 2015) Patient anxiety (Kenealy et al., 2015) Carer strain (Piette et al., 2015) | Patient depression at 3 months, (Dunbar et al., 2005; Schwarz et al., 2008) Patient/Carer depression at 12 months (Agren et al., 2012; Ågren et al., 2015) and 24 months (Liljeroos et al., 2015) Carer social support at 3 months (Schwarz et al., 2008) Carer burden (Agren et al., 2012, 2015) | Depression for both Patient and Carer; Social support for both Patient and Carer |

| Economic Outcomes | Patient rehospitalization at 6 months (Piamjariyakul et al., 2015; Hasanpour-Dehkordi et al., 2016) | Patient rehospitalization (Kenealy et al., 2015) at 2 (Bull et al., 2000) and 3 months (Schwarz et al., 2008) Patient cost (Kenealy et al., 2015) Patient QALY (Agren et al., 2013) | Rehospitalization for Patient |

Time of Measurement in months is provided for mixed outcome findings.

QALY-Quality adjusted life years.

3.4. Future directions/ongoing studies

Eight papers (six abstracts, (Chung et al., 2014a, 2014b; Bakitas et al., 2016; McIlvennan et al., 2015; Deek et al., 2015; Demers et al., 2014) one feasibility study, (Dionne-Odom et al., 2014) and one protocol paper (Taylor et al., 2015)) met the criteria of ongoing studies. We were unable to assess sufficient information on components, contexts, and outcomes to include them in our previous analyses. However, they indicate the direction of future research if these studies advance to full clinical trials. Two of the studies (one abstract, one feasibility study (Bakitas et al., 2016; Dionne-Odom et al., 2014); both from the same research team), adapted a successful concurrent oncology-palliative care model to heart failure. Two of the studies, (both abstracts(Chung et al., 2014a, 2014b); again from a single team), were small RCTs which tested, 1) a cognitive educational intervention and 2) a technology intervention. The three remaining studies examined decision aids (McIlvennan et al., 2015); family education (Deek et al., 2015); a multi-component trial comprised of a bathroom scale, decision aid, education and discharge summary to the primary care provider (Demers et al., 2014). Finally, the protocol paper described a health professional facilitated, home-based, rehabilitation intervention (Taylor et al., 2015). Taken together the ongoing studies appear like the complete studies in numbers and types of components, contexts and outcomes measures.

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of the interventions

The purpose of this paper was to review the existing literature on dyadic self-care interventions targeting patients with heart failure and their informal carers. We focused on intervention components tested to date, the contexts in which they were implemented, and the effect of these interventions on patient or carer outcomes. In summary, the included studies had great heterogeneity attributable to varying trial designs with a wide range of intervention components, follow-up periods, and outcome variables. The 12 complete studies included between two-six components generally delivered in a hospital or clinic, used increased amounts of technology over time, and resulted in mixed patient and/or carer outcomes at two weeks to 24 months. The eight ongoing studies were similarly designed and implemented. All of this taken together makes it challenging to recommend which interventions should be considered for wide-spread implementation or further development. However, components confirmed as important in qualitative, observational and intervention studies, such as assessing mutuality in patient-carer dyads, receiving joint but individualized education, having long-standing formal and informal social support throughout the illness trajectory should be emphasized (Hooker et al., 2017; Buck et al., 2017; Liljeroos et al., 2014b).

All studies (complete and ongoing) were judged to be of low to moderate quality. Each study had some methodological limitations, such as weak linkages to theoretical frameworks, small sample sizes, paucity of reported intervention detail, choice of outcome variables known to have floor and ceiling effects, and mixed intervention effects. In general, the studies should have been described in more detail. This lack of information limited our ability to recommend a particular intervention as a starting point for future development. When compared with the CONSORT guidelines (Moher, Schulz, Altman, & Group, 2001) and the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide (Hoffmann et al., 2014), there were significant amounts of missing information in several of the papers. However, based on the information that was provided, we can conclude that the body of evidence is limited and recent. In the following section, we will review specific findings and make recommendations for future work to advance the field of heart failure care.

4.2. Dyadic intervention components

Examination of the individual intervention components revealed there was great complexity within interventions and great heterogeneity across interventions. While there was an overarching, common logic that dyads need education, support, and guidance, there was also a sense that investigators were not able to determine what or how much of a specific component would result in better outcomes: the result was the inclusion of multiple components in all the interventions. This uncertainty is a challenge that may benefit from theoretical and methodological solutions. In particular, there is a need for careful development of theoretical frameworks with clear hypotheses and rationales for why and how an intervention should work. Given the fact that most of the interventions can be labelled as complex interventions, larger sample sizes, as well as mixed methods, should be considered for outcome evaluations.

4.3. Dyadic intervention contexts

This review also revealed a shift in delivery context over time. From a dyadic intervention in the early 2000s (Bull et al., 2000) which relied heavily on face-to-face interaction supplemented with paper information sources to several papers published 15 years later (Piette et al., 2015; Piamjariyakul et al., 2015; Kenealy et al., 2015) which primarily employed technology-based interventions, we could track the shift into telehealth to provide chronic heart failure management. Notably what did not change over time was the lack of robust improvements in measured outcomes. Other larger technology-based interventions in heart failure patient populations (Ong et al., 2016; Chaudhry et al., 2010) have reported similar null findings to those found in these dyadic papers. In these rigorous patient trials, intervention adherence was a critical failure. Even when operationalized and measured as only 50% adherence to a technology protocol, almost half of participants were non-adherent over time despite adherence boosts such as reminder phone calls. This suggests that technology, itself, will not improve heart failure outcomes. We need to systematically examine the social determinants of self-care and then test, rather than assume, that a technological solution is likely to improve outcomes.

4.4. Dyadic intervention outcomes

The lack of robust and sustained intervention outcomes is particularly concerning. A likely contributor to this may be that the papers included in this review had large variations in patient and carer characteristics as well as cultures and health care systems where they were conducted. There may be specific subgroups of patients and carers that might benefit more, or not at all, from dyadic self-care interventions. Developing such knowledge will enable self-care interventions to target dyadic groups anticipated to benefit most, which may become indispensable in times of decreasing health care resources. A second contributor to the lack of robust outcomes may be the lack (or at least unreported) stakeholder engagement before and during the intervention design phase. Co-design models have considerable potential to address the current limitations, particularly in technology-based interventions. Experience-based co-design is a user-focused approach that facilitates the access of patients’, family members’ and professionals’ experience when designing new innovative interventions in health care. Users and researchers work together as partners throughout the process and stages of change to provide a deeper understanding of the strengths and limitations of an intervention and what needs to be redesigned for the future (Bate and Robert, 2006). In our current patient-centered care environment, engaging patients early in any practice change is critically important to avoid changes that are unacceptable to patients and families.

4.5. Limitations

Every review has certain limitations that should be kept in mind when examining the findings. Search terms used, databases searched, and analytic techniques employed all shaped the results. We attempted to mitigate these limitations as much as possible by engaging two medical librarians with expertise in literature searches, including only team members with dyadic expertise, and careful development and registration of a protocol. However, other dyadic intervention studies, particularly those not published in English, may not have been captured.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the body of evidence for dyadic interventions in heart failure is small. All the papers in the current review had some methodological limitations, mixed intervention effects and counter-intuitive outcomes. Clearly, it is time to change the design, development, and implementation of dyadic heart failure interventions. Important steps to improve future interventions involve more advanced sample size estimations, innovative solutions to increase recruitment of dyads and decrease attrition during follow-up, use of mixed methods for capturing a more holistic picture of effects and finally studying implementation processes are warranted, as this is the last step of a successful intervention.

What is already known about the topic?

Having support from an informal carer is important for heart failure (HF) patients

Dyadic (patient and informal carer) HF self-care interventions seek to improve patient self-care such as adherence to medical treatment, exercise training, symptom monitoring and symptom management

No systematic assessment of dyadic interventions has been conducted with a focus on describing components, examining physical and delivery contexts, or determining the effect on patient and/or carer outcomes

What this paper adds.

The body of evidence for dyadic interventions in HF is small All the papers in the current review had methodological limitations, mixed intervention effects and counter-intuitive outcomes.

It is time to change the design, development, and implementation of dyadic HF interventions What is needed are co-design methods, judicious use of technology, careful development of theoretical frameworks, with clear hypotheses and descriptions of mechanisms and relevant outcome measures.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Carrie Cullen, BS, for her help during the editing process, particularly in reviewing and editing the references list to match the journal specifications.

Appendix A. Search Methodology

The medical librarians (AMH, RLP) developed and performed searches in PubMed (1946 to present), EMBASE (Elsevier, 1947 to present), Web of Science (Core Collection) (1900 to present), PsycINFO (EBSCO, 1887 to present), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, through August 2016).

MeSH terms, EMTREE terms, keywords, and keyword phrases were used to search for the following concepts: dyadic, caregivers, heart failure, and intervention. Search terms were shared with the subject experts to elicit feedback. The results were cross-referenced with various clinical study types and were not limited to randomized controlled trials. The librarians applied an English-only filter but no publication date limit.

PubMed

((((Caregivers[MeSH] OR Family[Mesh:noexp] OR Adult Children [Mesh] OR “informal care”[tiab] OR caregiver*[tiab] OR spous*[tiab] OR husband[tiab] OR wife[tiab] OR family[tiab] OR families[tiab] OR son[tiab] OR daughter[tiab] OR partner*[tiab] OR couple*[tiab] OR carer[tiab] OR carers[tiab] OR dyad*[tiab])) AND (Heart Failure [Mesh:noexp] OR Heart Failure, Diastolic[Mesh] OR Heart Failure, Systolic[Mesh] OR “heart failure”[tiab] OR “cardiac failure”[tiab] OR “heart decompensation”[tiab])) AND Intervention*[tiab]) AND (cohort studies[Mesh] OR cohort stud*[tiab] OR “Follow-Up Study”[tiab] OR “Follow-Up Studies”[tiab] OR “Longitudinal Study”[tiab] OR “Longitudinal Studies”[tiab] OR “Prospective Study”[tiab] OR “Prospective Studies”[tiab] OR “Retrospective Study”[tiab] OR “Retrospective Studies”[tiab] OR clinical study[PT] OR clinical study [tiab] OR clinical studies as topic[MeSH] OR controlled clinical trials as topic[Mesh] OR randomized controlled trial*[tiab] OR RCT[tiab] OR pre-intervention*[tiab] OR preintervention*[tiab] OR post-intervention*[tiab] OR postintervention*[tiab] OR pre-test*[tiab] OR pre-test*[tiab] OR post-test*[tiab] OR posttest*[tiab] OR pre-design*[tiab] OR predesign*[tiab] OR post-design*[tiab] OR postdesign*[tiab] OR pre-pilot*[tiab] OR prepilot*[tiab] OR post-pilot*[tiab] OR post-pilot*[tiab] OR pre-treatment*[tiab] OR pretreatment*[tiab] OR post-treatment*[tiab] OR posttreatment*[tiab]) Filters: English

EMBASE

(‘caregiver’/exp OR ‘family’/de OR ‘adult child’/exp OR ‘informal care’:ab,ti OR caregiver*:ab,ti OR ‘spouse’/exp OR spous*:ab,ti OR husband:ab,ti OR wife:ab,ti OR family:ab,ti OR families:ab,ti OR ‘son’/exp OR son:ab,ti OR ‘daughter’/exp OR daughter:ab,ti OR ‘cohabiting person’/exp OR partner*:ab,ti OR couple*:ab,ti OR carer:ab,ti OR carers:ab,ti OR dyad*:ab,ti) AND (‘heart failure’/de OR ‘congestive heart failure’/de OR ‘diastolic heart failure’/exp OR ‘systolic heart failure’/exp OR ‘heart failure’:ab,ti OR ‘cardiac failure’:ab,ti OR ‘heart decompensation’:ab,ti) AND (Intervention*:ab,ti) AND (‘cohort analysis’/exp OR ‘cohort analysis’:ab,ti OR ‘cohort study’:ab,ti OR ‘cohort studies’:ab,ti OR ‘follow-up study’:ab,ti OR ‘follow-up studies’:ab,ti OR ‘clinical study’/exp OR ‘clinical study’:ab,ti OR ‘clinical studies’:ab,ti OR ‘longitudinal study’:ab,ti OR ‘longitudinal studies’:ab,ti OR ‘prospective study’:ab,ti OR ‘prospective studies’:ab,ti OR ‘retrospective study’:ab,ti OR ‘retrospective studies’:ab,ti OR ‘randomized controlled trial*’:ab,ti OR rct:ab,ti OR ‘pre intervention*’:ab,ti OR preintervention*:ab,ti OR ‘post intervention*’:ab,ti OR postintervention*:ab,ti OR ‘pre test*’:ab,ti OR pretest*:ab,ti OR ‘post test*’:ab,ti OR posttest*:ab,ti OR ‘pre design*’:ab,ti OR predesign*:ab,ti OR ‘post design*’:ab,ti OR post-design*:ab,ti OR ‘pre pilot*’:ab,ti OR prepilot*:ab,ti OR ‘post pilot*’:ab,ti OR postpilot*:ab,ti OR ‘pre treatment*’:ab,ti OR pretreatment*:ab,ti OR ‘post treatment*’:ab,ti OR posttreatment*:ab,ti OR ‘pretest posttest design’/exp OR ‘controlled study’/exp OR ‘pretest posttest design’:ab,ti OR ‘pretest posttest control group design’:ab,ti OR ‘controlled study’:ab,ti OR ‘controlled studies’:ab,ti)

Filter: English

Web of Science (Core Collection)

(caregiver* OR family OR families OR “adult children” OR “informal care” OR spous* OR husband OR wife OR son OR daughter OR partner* OR couple* OR carer OR carers OR dyad*) AND (“heart failure” OR “cardiac failure” OR “heart decompensation”) AND (intervention*) AND (“cohort study” OR “cohort studies” OR “follow-up study” OR “follow-up studies” OR “longitudinal study” OR “longitudinal studies” OR “prospective study” OR “prospective studies” OR “retrospective study” OR “retrospective studies” OR “clinical study” OR “clinical studies” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “controlled clinical trials” OR “controlled study” OR “controlled studies” OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “randomized controlled trials” OR rct OR pre-intervention* OR preintervention* OR post-intervention* OR post-intervention* OR pre-test* OR pretest* OR post-test* OR posttest* OR pre-design* OR predesign* OR post-design* OR postdesign* OR prepilot* OR prepilot* OR post-pilot* OR postpilot* OR pre-treatment* OR pretreatment* OR post-treatment* OR posttreatment* OR “randomized study” OR “randomized studies”) Refined by: LANGUAGES: (ENGLISH)

PsycINFO

(Caregivers OR DE family OR TI family OR AB family OR KW family OR family members OR DE adult offspring OR adult child* OR DE couples OR spous* OR husband* OR DE wives OR wife OR DE sons OR TI son* OR AB son* OR KW son* OR daughter OR carer OR carers OR DE dyads OR dyad*) AND (Heart Failure OR cardiac failure) AND (Intervention OR psychosocial support OR psychoeducation*)

Limiters – English Language; Peer Reviewed, Journal Article, No Dissertations

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

(caregiver* OR caregiver support OR family OR adult child* OR couple OR sons or daughters or husbands or wives or dyad* OR carer or carers) AND (heart failure OR cardiac failure) AND (intervention* OR psychosocial support)

The combined searches yielded 1271 citations as of September 29, 2016. All citations were exported into EndNote and duplicates were mechanically removed. The remaining citations (890) were imported into an MS EXCEL worksheet for purposes of documenting the inclusion/exclusion analysis performed by the subject matter specialists.

References

- Agren S, Evangelista LS, Hjelm C, Stromberg A, 2012. Dyads affected by chronic heart failure: a randomized study evaluating effects of education and psychosocial support to patients with heart failure and their partners. J. Card. Fail 18 (5), 359–366. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agren S, S.E. L, Davidson T, Stromberg A, 2013. Cost-effectiveness of a nurse-led education and psychosocial programme for patients with chronic heart failure and their partners. J. Clin. Nurs 22 (15–16), 2347–2353. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agren S, Stromberg A, Jaarsma T, Luttik ML, 2015. Caregiving tasks and caregiver burden; effects of an psycho-educational intervention in partners of patients with post-operative heart failure. Heart Lung 44 (4), 270–275. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ågren S, Berg S, Svedjeholm R, Strömberg A, 2015. Psychoeducational support to post cardiac surgery heart failure patients and their partners—a randomised pilot study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs 31 (1), 10–18. 10.1016/j.iccn.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakitas M, Dionne-Odom JN, Kvale E, Kono A, Pamboukian S, 2016. A tale of two cities: results of the enable CHF-PC early, concurrent palliative care heart failure feasibility trial. J. Pain Symp. Manage 51 (2), 405–406. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bate P, Robert G, 2006. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual. Saf. Health Care 15 (5), 307–310. 10.1136/qshc.2005.016527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck HG, Meghani S, Bettger JP, et al. , 2012. The use of comorbidities among adults experiencing care transitions: a systematic review and evolutionary analysis of empirical literature. Chronic Ill 8 (4), 278–295. 10.1177/1742395312444741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck HG, Akbar JA, Zhang SJ, Bettger JAP, 2013. Measuring comorbidity in cardiovascular research: a systematic review. Nurs. Res. Pract 2013, 11 10.1155/2013/563246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck HG, Harkness K, Wion R, et al. , 2015a. Caregivers’ contributions to heart failure self-care: a systematic review. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 14 (1), 79–89. 10.1177/1474515113518434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck HG, Mogle J, Riegel B, McMillan S, Bakitas M, 2015b. Exploring the relationship of patient and informal caregiver characteristics with heart failure self-care using the actor-partner interdependence model: implications for outpatient palliative care. J. Palliat. Med 18 (12), 1026–1032. 10.1089/jpm.2015.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck HG, Hupcey J, Watach A, 2017. Patterns vs. change: community-based dyadic heart failure self-care. Clin. Nurs. Res 1–14. 10.1177/1054773816688817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull MJ, Hansen HE, Gross CR, 2000. A professional-patient partnership model of discharge planning with elders hospitalized with heart failure. Appl. Nurs. Res 13 (1), 19–28. 10.1016/S0897-1897(00)80015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry SI, Mattera JA, Curtis JP, et al. , 2010. Telemonitoring in patients with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med 363 (24), 2301–2309. 10.1056/NEJMoa1010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung ML, Lennie TA, Moser DK, 2014a. The feasibility of the family cognitive educational intervention to improve depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with heart failure and their family caregivers. J. Card. Fail 20 (8 Suppl. 1), S52 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.06.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung ML, Moser DK, Lennie TA, 2014b. Feasibility of family sodium watcher program to improve adherence to low sodium diet in patients with heart failure and caregivers. Circulation 130 (Suppl. 2). [Google Scholar]

- Clark AM, Spaling M, Harkness K, et al. , 2014. Determinants of effective heart failure self-care: a systematic review of patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions. Heart 100, 716–721. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AM, Wiens K, Banner D, et al. , 2016. A systematic review of the main mechanisms of heart failure disease management interventions. Heart 102 (9), 707–711. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2017. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Making Sense of Evidence. http://www.casp-uk.net/appraising-the-evidence Accessed September 15 2016.

- Currie K, Strachan PH, Spaling M, Harkness K, Barber D, Clark AM, 2015. The importance of interactions between patients and healthcare professionals for heart failure self-care: a systematic review of qualitative research into patient perspectives. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 14 (6), 525–535. 10.1177/1474515114547648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deek H, Newton PJ, Inglis SC, Noureddine S, Macdonald PS, Davidson PM, 2015. Family focused approach to improve heart failure care in Lebanon quality (family) intervention: randomized controlled trial for implementing an education family session. Eur. Heart J 36, 1005–1006. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv401.25934673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demers C, Patterson C, Archer N, et al. , 2014. A simple multi-component intervention improves self management in heart failure. Can. J. Cardiol 30 (10), S201 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.07.328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne-Odom JN, Kono A, Frost J, et al. , 2014. Translating and testing the ENABLE: CHF-PC concurrent palliative care model for older adults with heart failure and their family caregivers. J. Palliat. Med 17 (9), 995–1004. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Deaton C, Smith AL, De AK, O’Brien MC, 2005. Family education and support interventions in heart failure: a pilot study. Nurs. Res 54 (3), 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Reilly CM, et al. , 2013. A trial of family partnership and education interventions in heart failure. J. Card. Fail 19 (12), 829–841. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Stamp KD, et al. , 2016. Family partnership and education interventions to reduce dietary sodium by patients with heart failure differ by family functioning. Heart Lung 45 (4), 311–318. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness K, Spaling MA, Currie K, Strachan PH, Clark AM, 2015. A systematic review of patient heart failure self-care strategies. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 30 (2), 121–135. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Khaledi-Far A, Khaledi-Far B, Salehi-Tali S, 2016. The effect of family training and support on the quality of life and cost of hospital readmissions in congestive heart failure patients in Iran. Appl. Nurs. Res 31, 165–169. 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. , 2014. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348, g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker SA, Schmiege SJ, Trivedi RB, Amoyal NR, Bekelman DB, 2017. Mutuality and heart failure self-care in patients and their informal caregivers. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 0 (0). 10.1177/1474515117730184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman NH, Westland H, Groenwold RH, et al. , 2016. Do self-management interventions work in patients with heart failure? An individual patient data meta-analysis. Circulation 133 (12), 1189–1198. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenealy TW, Parsons MJ, Rouse AP, et al. , 2015. Telecare for diabetes, CHF or COPD: effect on quality of life, hospital use and costs. A randomised controlled trial and qualitative evaluation. PLoS One 10 (3), e0116188 10.1371/journal.pone.0116188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitko LA, Hupcey JE, Pinto C, Palese M, 2014. Patient and caregiver incongruence in advanced heart failure. Clin. Nurs. Res 24 (4), 388–400. 10.1177/1054773814523777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. , 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-Analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med 151 (4), 65–94. 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljeroos M, Agren S, Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, 2014a. Long term effects of an integrated educational and psychosocial intervention in partners to patients affected by heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 13, S56 10.1177/1474515114521363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljeroos M, Agren S, Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, 2014b. Perceived caring needs in patient-partner dyads affected by heart failure: a qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs 23 (19–20), 2928–3298. 10.1111/jocn.12588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljeroos M, Agren S, Jaarsma T, Arestedt K, Stromberg A, 2015. Long term follow-up after a randomized integrated educational and psychosocial intervention in patient-partner dyads affected by heart failure. PLoS One 10 (9), e0138058 10.1371/journal.pone.0138058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljeroos M, Agren S, Jaarsma T, Arestedt K, Stromberg A, 2016. Long-term effects of a dyadic psycho-educational intervention on caregiver burden and morbidity in partners of patients with heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Qual. Life Res 26 (2), 367–379. 10.1007/s11136-016-1400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlvennan CK, Thompson JS, Matlock DD, Cleveland JC, Allen LA, 2015. An acceptability and feasibility study of decision aids for patients and their caregivers considering destination therapy left ventricular assist device. J. Card. Fail 21 (8), S6–S7. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.06.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. n.d retrieved 05/03/17 at https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dyad?utm_campaign=sd&utm_medium=serp&utm_source=jsonld.

- Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, 2001. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 357 (9263), 1191–1194. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong MK, Romano PS, Edgington S, et al. , 2016. Effectiveness of remote patient monitoring after discharge of hospitalized patients with heart failure: the better effectiveness after transition-heart failure (BEAT-HF) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med 176 (3), 310–318. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K, 2005. Realist review-a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 10 (Suppl. 1), 21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piamjariyakul U, Werkowitch M, Wick J, Russell C, Vacek JL, Smith CE, 2015. Caregiver coaching program effect: reducing heart failure patient rehospitalizations and improving caregiver outcomes among African Americans. Heart Lung 44 (6), 466–473. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Gregor MA, Share D, et al. , 2008. Improving heart failure self-management support by actively engaging out-of-home caregivers: results of a feasibility study. Congest. Heart Fail 14 (1), 12–18. 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.07474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Striplin D, Marinec N, Chen J, Aikens JE, 2015. A randomized trial of mobile health support for heart failure patients and their informal caregivers: impacts on caregiver-reported outcomes. Med. Care 53 (8), 692–699. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. , 2016. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European society of cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J 37 (27), 2129–2200. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel B, Dickson VV, Faulkner KM, 2016. The Situation-specific theory of heart failure self-care: revised and updated. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 31 (3), 226–235. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz KA, Mion LC, Hudock D, Litman G, 2008. Telemonitoring of heart failure patients and their caregivers: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs 23 (1), 18–26. 10.1111/j.1751-7117.2008.06611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaling MA, Currie K, Strachan PH, Harkness K, Clark AM, 2015. Improving support for heart failure patients: a systematic review to understand patients’ perspectives on self-care. J. Adv. Nurs 71 (11), 2478–2489. 10.1111/jan.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisuk N, Cameron J, Ski CF, Thompson DR, 2015. A family-based education program for heart failure patients and carers in rural Thailand: a randomised controlled trial. Heart Lung Circ. 24, S418 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.06.709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stamp KD, Dunbar SB, Clark PC, et al. , 2016. Family partner intervention influences self-care confidence and treatment self-regulation in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 15 (5), 317–327. 10.1177/1474515115572047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan PH, Currie K, Harkness K, Spaling M, Clark AM, 2014. Context matters in HF self-care: a qualitative systematic review. J. Card. Fail 20 (6), 448–455. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RS, Hayward C, Eyre V, et al. , 2015. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the rehabilitation enablement in chronic heart failure (REACH-HF) facilitated self-care rehabilitation intervention in heart failure patients and caregivers: rationale and protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 5 (12), e009994 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellone E, Chung ML, Cocchieri A, Rocco G, Alvaro R, Riegel B, 2014. Effects of self-care on quality of life in adults with heart failure and their spousal caregivers: testing dyadic dynamics using the actor–partner interdependence model. J. Fam. Nurs 20 (1), 120–141. 10.1177/1074840713510205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R, 2013. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med. 11 (1), 21 10.1186/1741-7015-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. , 2013. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the american college of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 62 (16), 1495–1539. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]